Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods Description

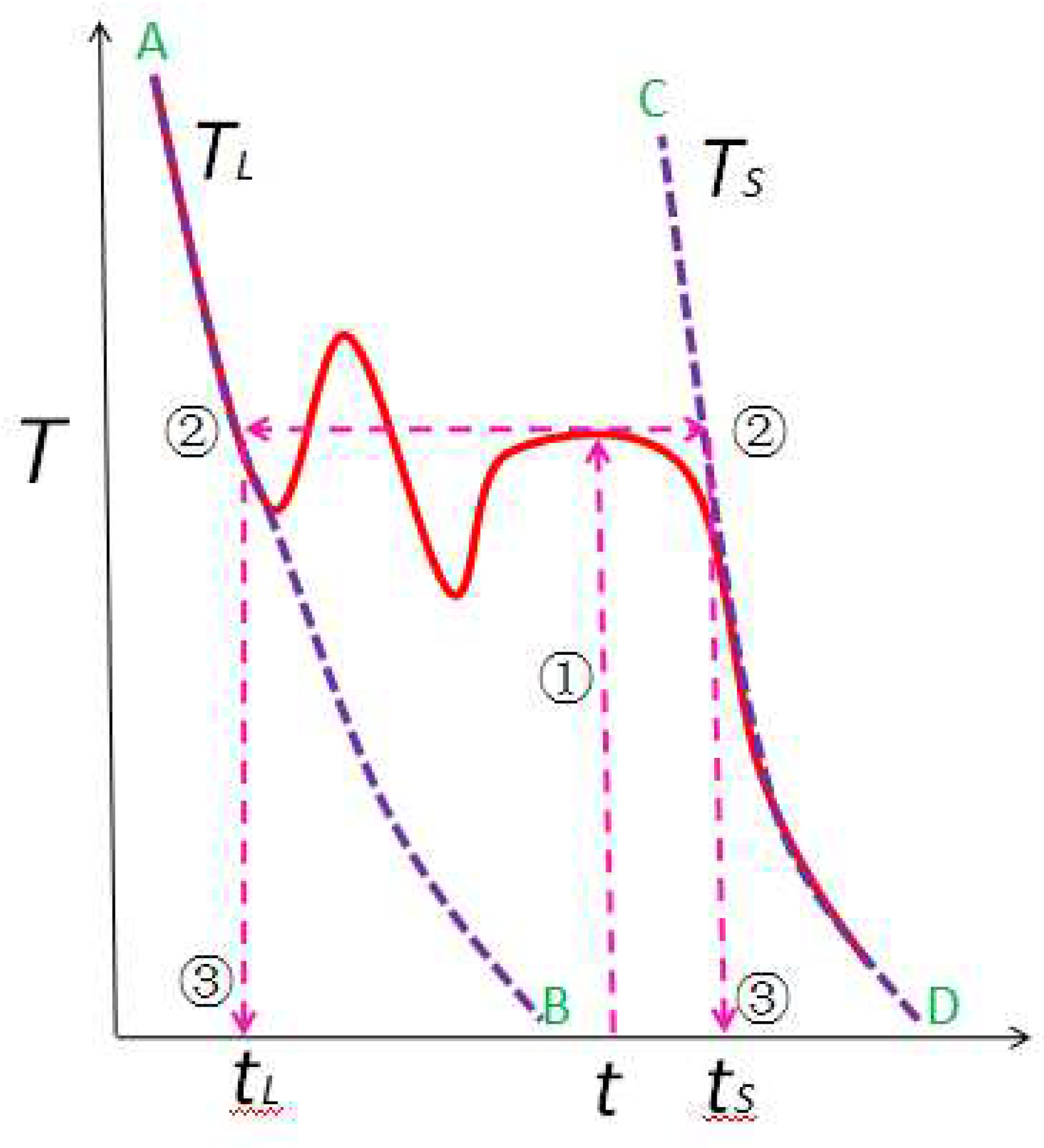

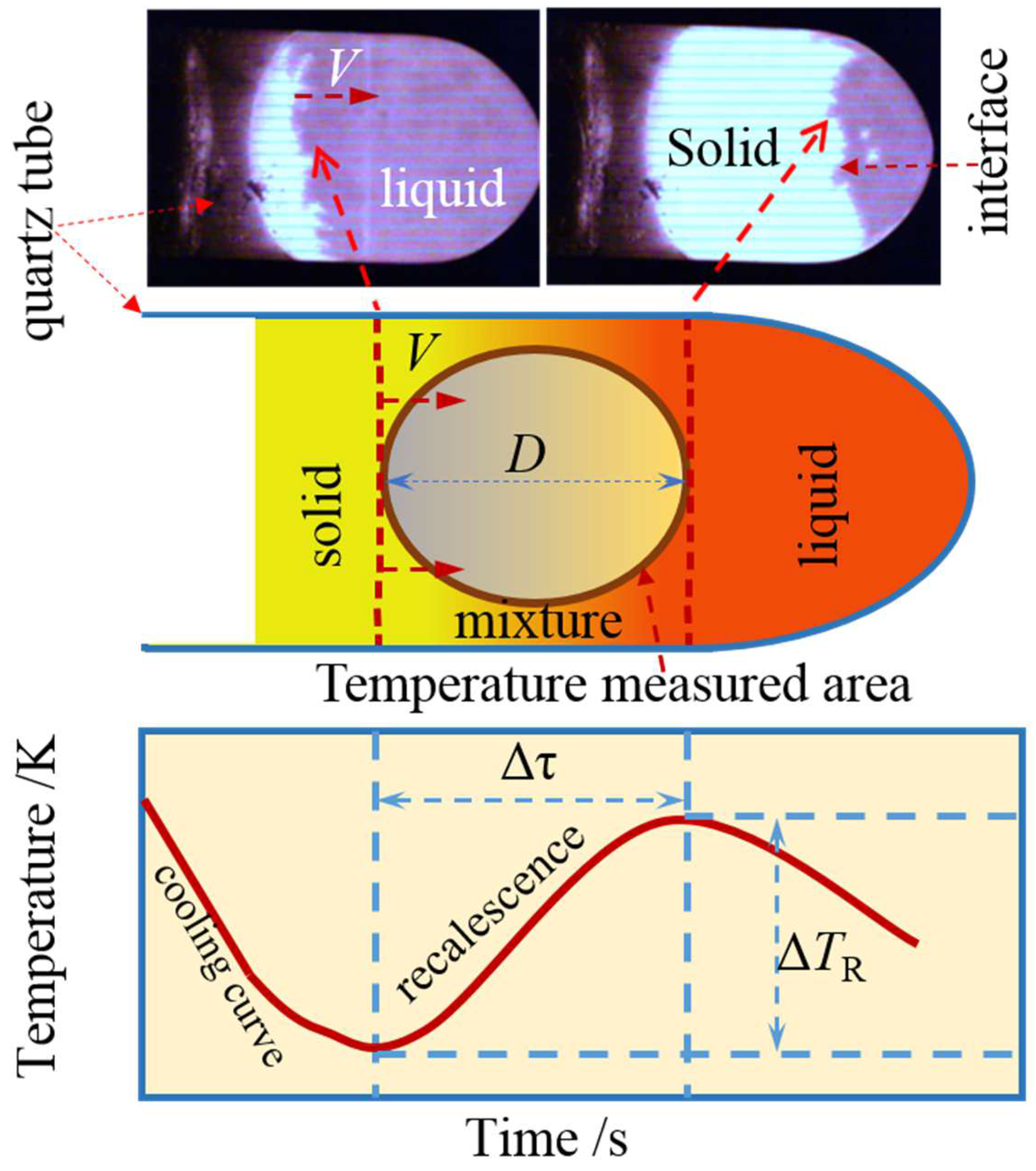

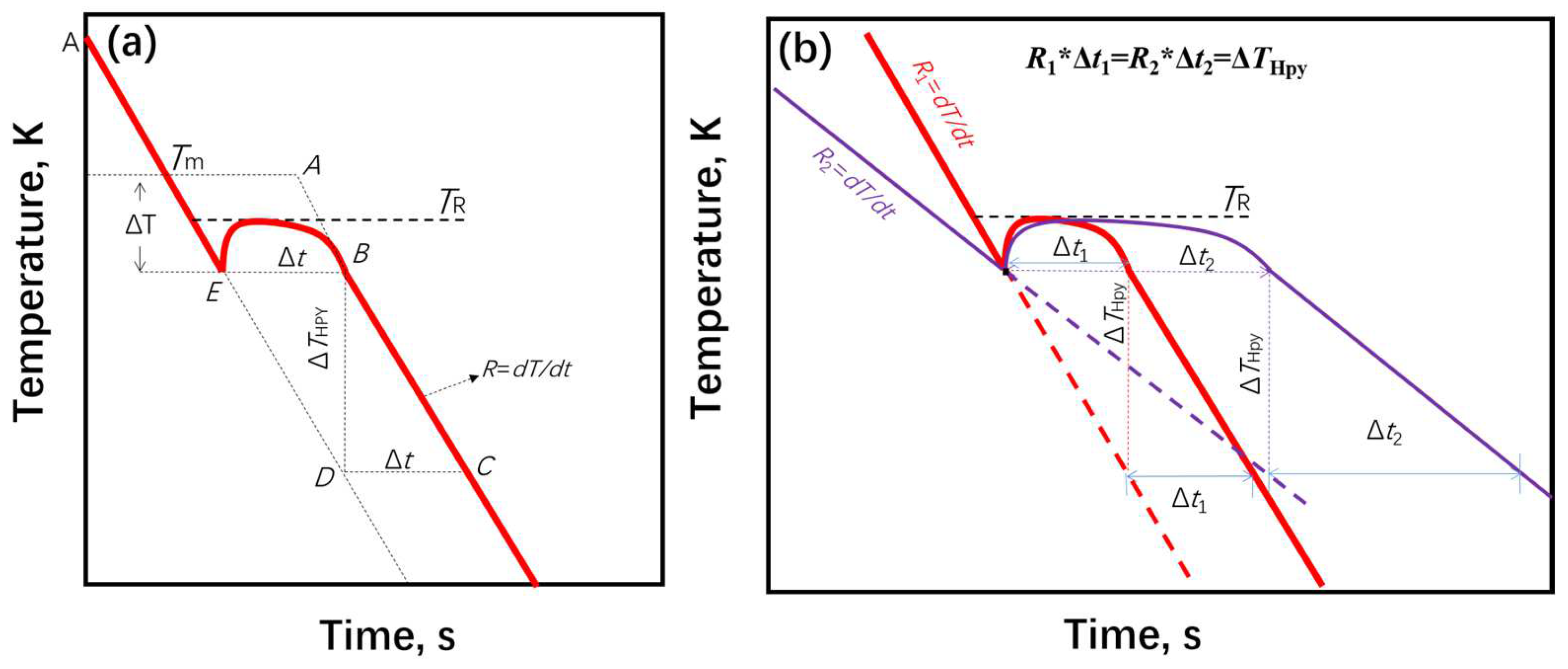

2.1. Phase Fraction Prediction Method

2.2. Microstructure Measurement Method

3. Experimental

4. Discussions

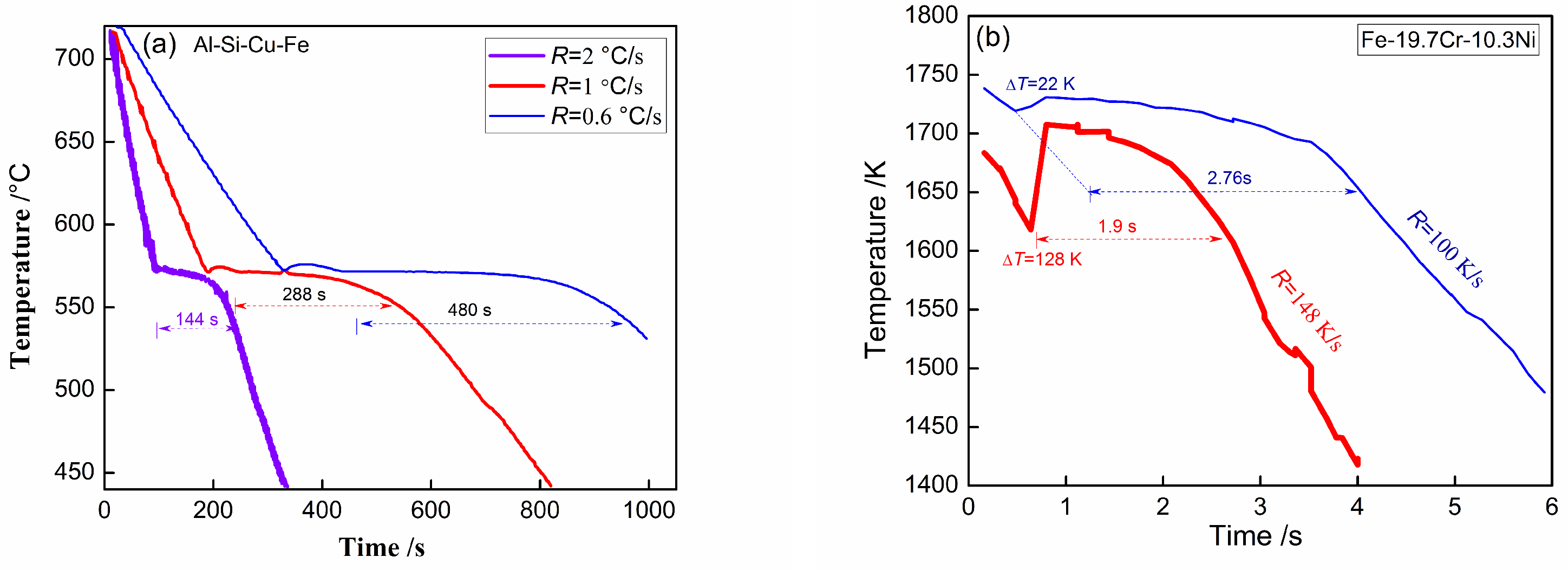

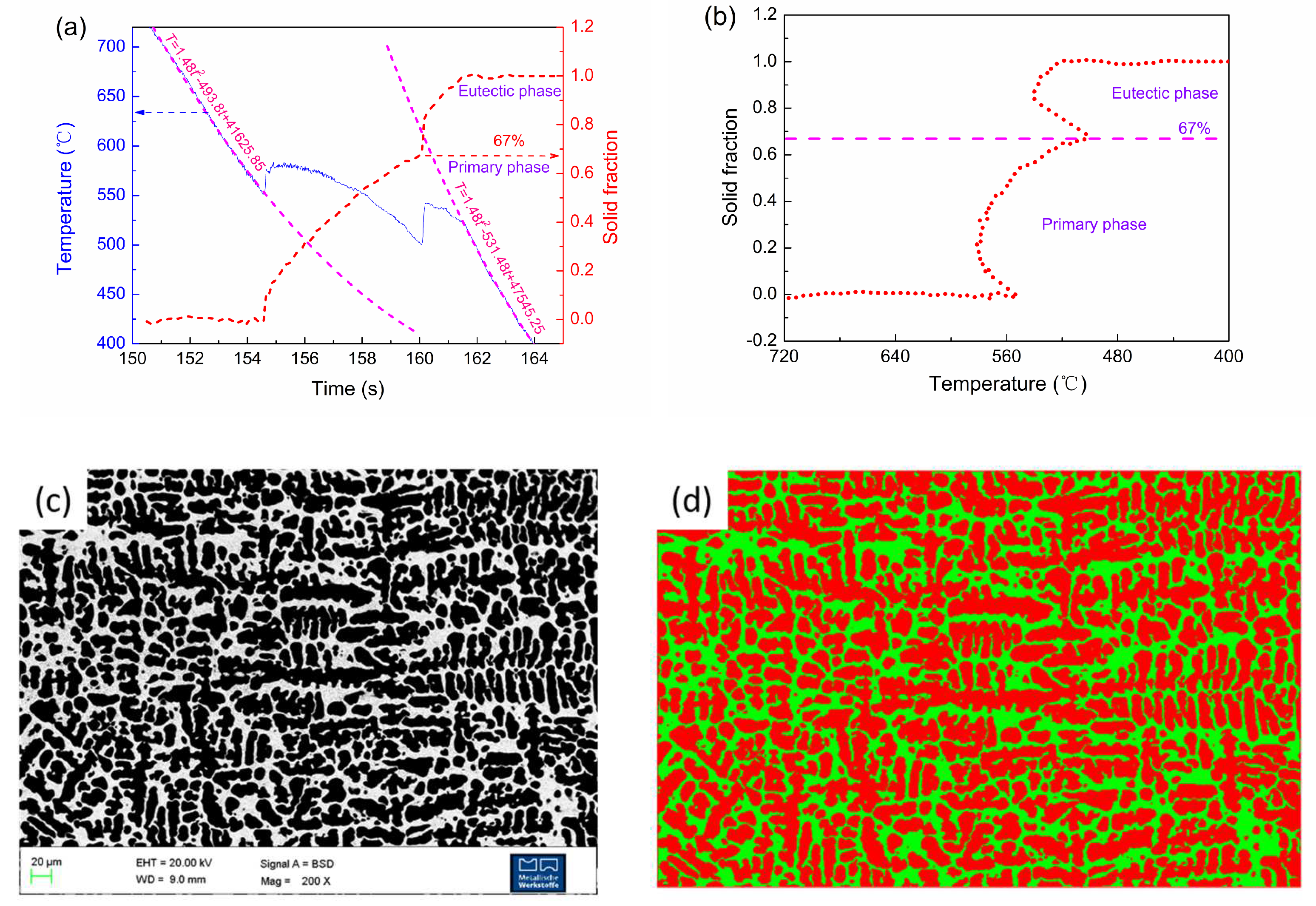

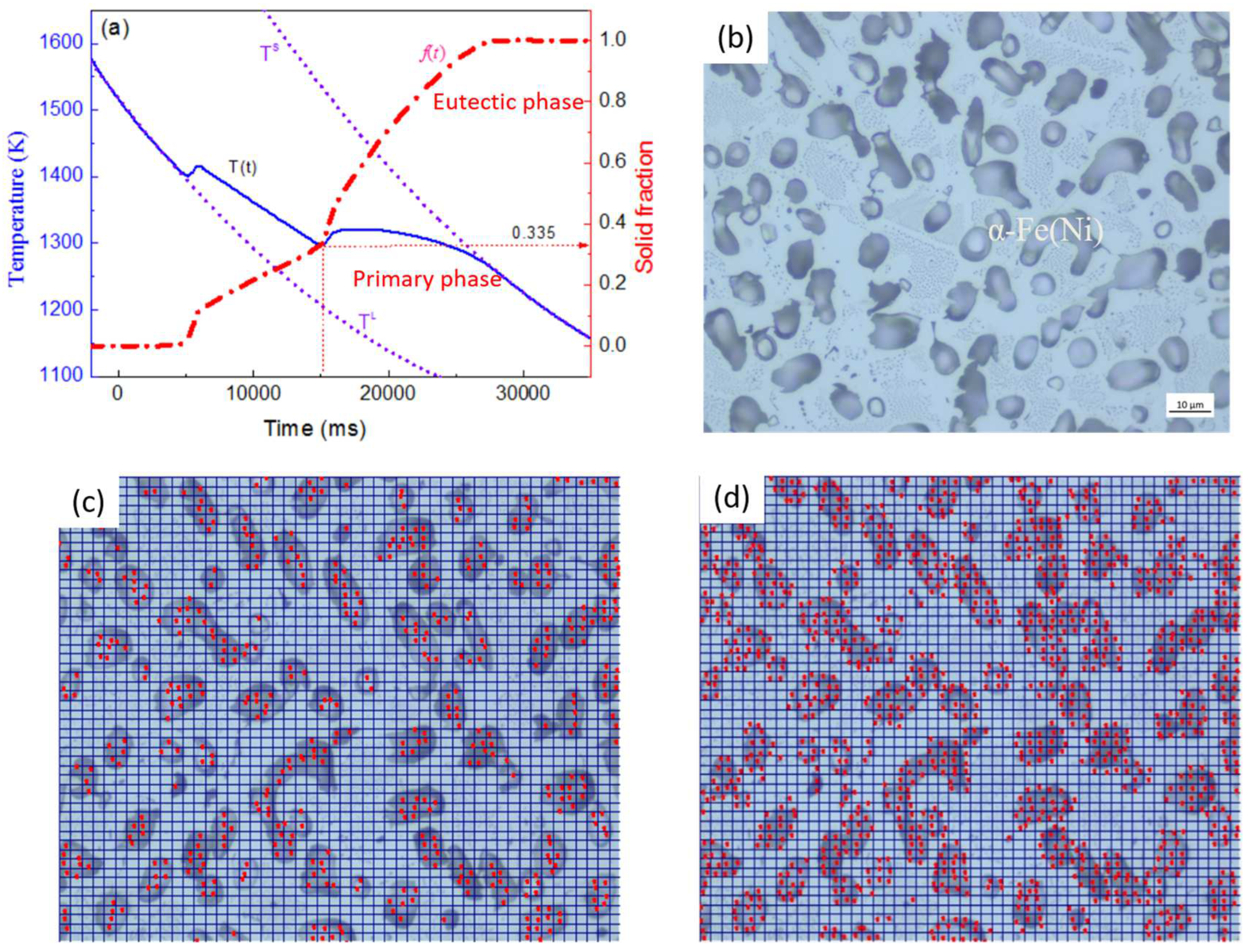

4.1. Solidification Fraction

4.2. Solidification Rate

4.3. Solidification Plateau Time

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Tang, P.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Q. Investigation on the solidification course of Al–Si alloys by using a numerical Newtonian thermal analysis method. Mater. Res. Express 2017, 4, 126511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiyama, T.; Hirano, K.; Sato, H.; Ono, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Ito, D.; Saito, Y. Application of Machine Learning Methods to Neutron Transmission Spectroscopic Imaging for Solid–Liquid Phase Fraction Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Kusumi, A.; Shiota, Y.; Hayashida, H.; Su, Y.; Parker, J.D.; Watanabe, K.; Kamiyama, T.; Kiyanagi, Y. Visualising Martensite Phase Fraction in Bulk Ferrite Steel by Superimposed Bragg-edge Profile Analysis of Wavelength-resolved Neutron Transmission Imaging. ISIJ Int. 2022, 62, 2319–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarda, D.; Martinez-Garcia, J.; Fenk, B.; Schiffmann, D.; Gwerder, D.; Stamatiou, A.; Worlitschek, J.; Mancin, S.; Schuetz, P. New liquid fraction measurement methodology for phase change material analysis based on X-ray computed tomography. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2023, 194, 108585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, R.R.; Nandwana, P.; Ren, Y.; Choo, H. Solidification texture, variant selection, and phase fraction in a spot-melt electron-beam powder bed fusion processed Ti-6Al-4V. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, H.; Gonzalez, C.; Juárez, A.; Herrera, M.; Juarez, J. Quantification of the microconstituents formed during solidification by the Newton thermal analysis method. J. Mech. Work. Technol. 2006, 178, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher P, Pogatscher S, Starink M J, SchickC, Mohles V and Milkereit B 2015 Quench-induced precipitates in Al–Si alloys: calorimetric determination of solute content and characterisation of microstructure Thermochim. Acta 602 63–73.

- Hernandez FCR and Sokolowski J H 2006 Thermal analysis and microscopical characterization of Al–Si hypereutectic alloys J. Alloys Compd. 419 180–90.

- Farahany S, Idris M H, OurdjiniA, Faris F and Ghandvar H 2015 Evaluation of the effect of grain refiners on the solidification characteristics of an Sr-modified ADC12 die-casting alloy by cooling curve thermal analysis J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 119 1593–601.

- Fras, E. , Kapturkiewicz, W., Burbielko, A., & Lopez, H. F. (1993). A new concept in thermal analysis of castings. Transactions of the American Foundrymen’s Society., 101, 505-511.

- Emadi, D.; Whiting, L.V.; Djurdjevic, M.; Kierkus, W.T.; Sokolowski, J. Comparison of Newtonian and Fourier thermal analysis techniques for calculation of latent heat and solid fraction of aluminum alloys. Met. Met. 2004, 10, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, F.; Xu, X.; Chen, Y. Determination of Solid Fraction from Cooling Curve. Met. Mater. Trans. A 2011, 43, 1268–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dediaeva E, PadalkoA, Akopyan T, SuchkovA and FedotovV 2015 Barothermography and microstructure of the hypoeutectic and eutectic alloys in Al–Si system J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 121 485–90.

- J.W. Gibbs, M.J. Kaufman, R.E. Hackenberg, and P.F. Mendez: Metall. Mater. Trans. A, 2010, vol. 41A, pp. 2216–23.

- Djurdjevic M B, Odanovic Z, Talijan N. Characterization of the solidification path of AlSi5Cu (1–4 wt.%) alloys using cooling curve analysis[J]. Jom, 2011, 63(11): 51-57.

- D.M. Stefanescu, G. Upadhya, D. Bandyopadhyay, Metall. Trans. A 21A (1990) 997–100.

- Surfusion in Metals and Alloys1. Nature 1898, 58, 619–621. [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Reddy, P.; Kumar, A. A methodology to integrate melt pool convection with rapid solidification and undercooling kinetics in laser spot welding. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 164, 120575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Yao, Z.; Li, X.; Xu, J. Rapid Solidification of Invar Alloy. Materials 2023, 17, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galenko, P.; Toropova, L.; Alexandrov, D.; Phanikumar, G.; Assadi, H.; Reinartz, M.; Paul, P.; Fang, Y.; Lippmann, S. Anomalous kinetics, patterns formation in recalescence, and final microstructure of rapidly solidified Al-rich Al-Ni alloys. Acta Mater. 2022, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Chua, B.-L.; Saad, I.; Liew, W.Y.H. Effect of Co on Solidification Characteristics and Microstructural Transformation of Nonequilibrium Solidified Cu-Ni Alloys. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Sci. Ed. 2024, 39, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, F.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Yang, G.; Zhou, Y. Prediction of the maximal recalescence temperature upon rapid solidification of bulk undercooled Cu70Ni30 alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 2008, 470, L13–L16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullis, A.M.; Clopet, C.R. On the origin of anomalous eutectic growth from undercooled melts: Why re-melting is not a plausible explanation. Acta Mater. 2018, 145, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. -A. Gandin, S. Mosbah, T. Volkmann, and D.M. Herlach: Acta Mater., 2008, 56, pp. 3023–35.

- Xu, J.; Jian, Z.; Lian, X. An application of box counting method for measuring phase fraction. Measurement 2017, 100, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Jian, Z. Observe the temperature curve for solidification from high-speed video image. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2021, 146, 2273–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahany, S.; Ourdjini, A.; Idris, M.H.; Shabestari, S.G. Computer-aided cooling curve thermal analysis of near eutectic Al–Si–Cu–Fe alloy. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2013, 114, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseki Toshihiko. “Undercooling and rapid solidification of Fe-Cr-Ni ternary alloys.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1994.4.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).