Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

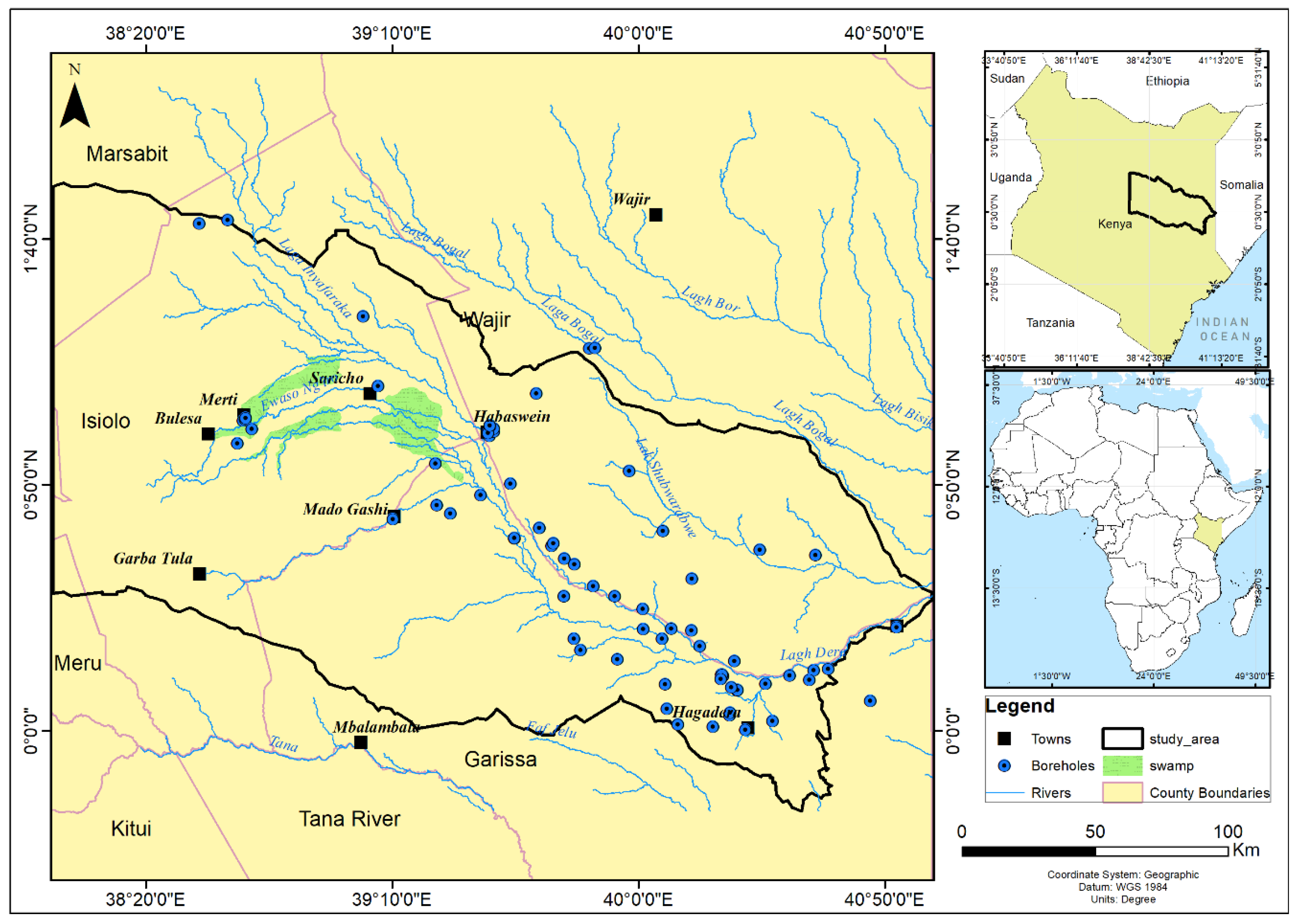

2.1:. The Study Area

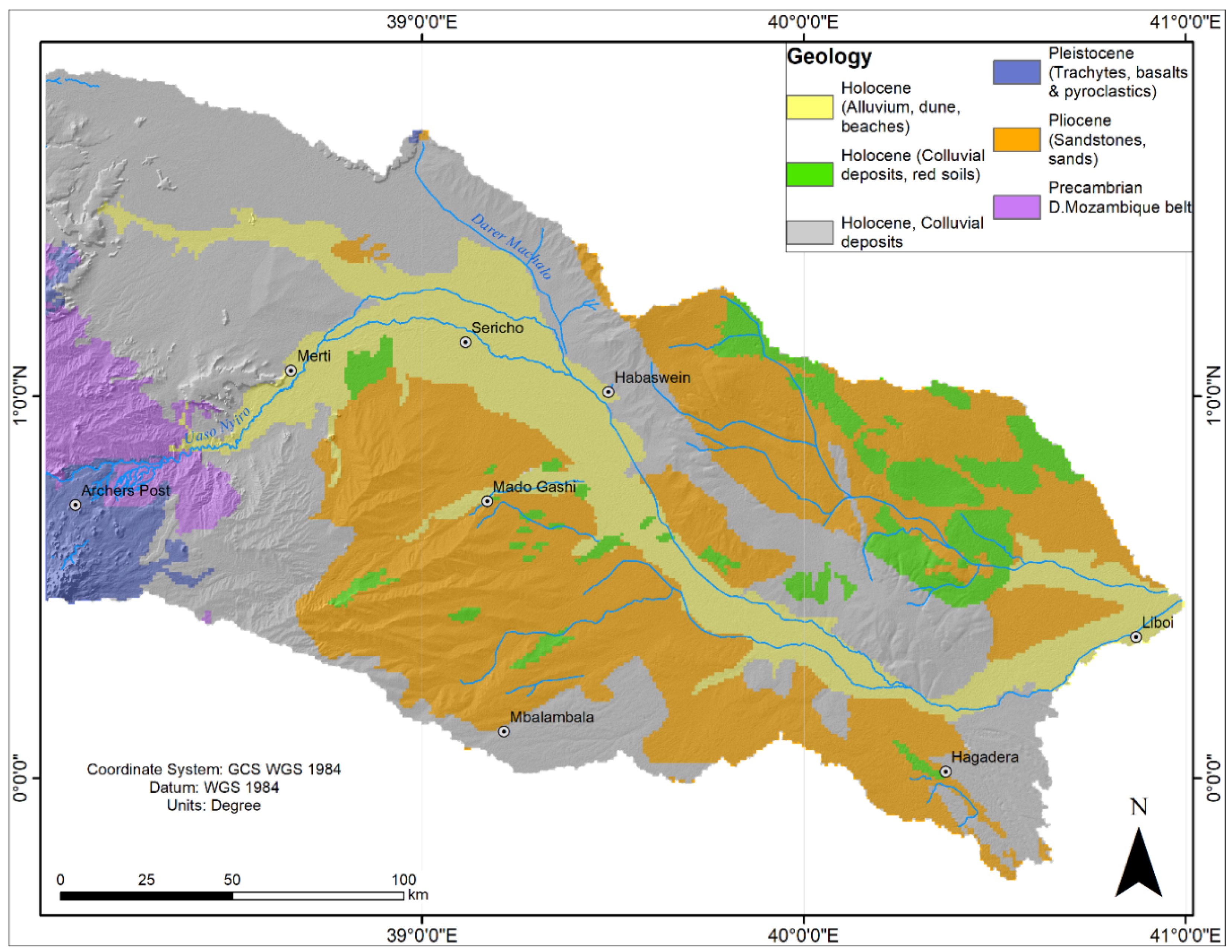

2.2:. Geology and Hydrogeology

2.3. Sampling and Analysis

- Selections of the parameters. In this study, the parameters were EC, TDS, pH TH, Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, HCO3-, Cl-, SO42-, and NO3-.

- Assigning of weights of the parameters (Wi). The assigning of the weight took into consideration the influence of the parameter on water quality and the weight rating of studies carried out in similar settings [77,78]. The weighting ranged from 2 – 5. The highest weight of 5 was awarded TDS, and NO3-. EC, pH, and SO42- were awarded a weight of 4, HCO3- and Cl- were awarded a weight of 3, whereas Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, and TH were awarded a weight of 2. Relative weights(wi) for the ith parameter and n number of parameters was then calculated using the formulae (Eq. 2).wi represents the relative weight of the parameter, and Wi is the assigned weight of each parameter.

-

Calculation of the quality rating (Qi) of each of the parameters using the formulae (Eq. 3).Where Ci is the measured concentration of each of the parameterSi is the permissible standard guideline value for the parameter; for this study, the WHO (2017) (Table 3) standards were considered.

- Calculation of the overall water quality index using the equation 4

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of Geochemistry

| Units | Min | Max | Median | Average | Maximum allowable limit (WHO 2017) |

Maximum allowable limit (WASREB-KENYA 2016) |

Percentage Number of samples above (WHO) acceptable limit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PH | - | 7.1 | 8.9 | 7.7 | 7.9 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 13.3 |

| EC | μS/cm | 419.8 | 18000.0 | 1232.2 | 1937.0 | 1500 | 1500 | 36.0 |

| TDS | Mg/l | 313.8 | 8366.0 | 912.0 | 1422.9 | 1000 | 1500 | 25.4 |

| HCO3- | Mg/l | 109.2 | 4979.2 | 560.5 | 767.7 | 300 | 500 | 85.3 |

| Cl- | Mg/l | 2.0 | 4300.0 | 60.0 | 217.1 | 600 | 250 | 5.3 |

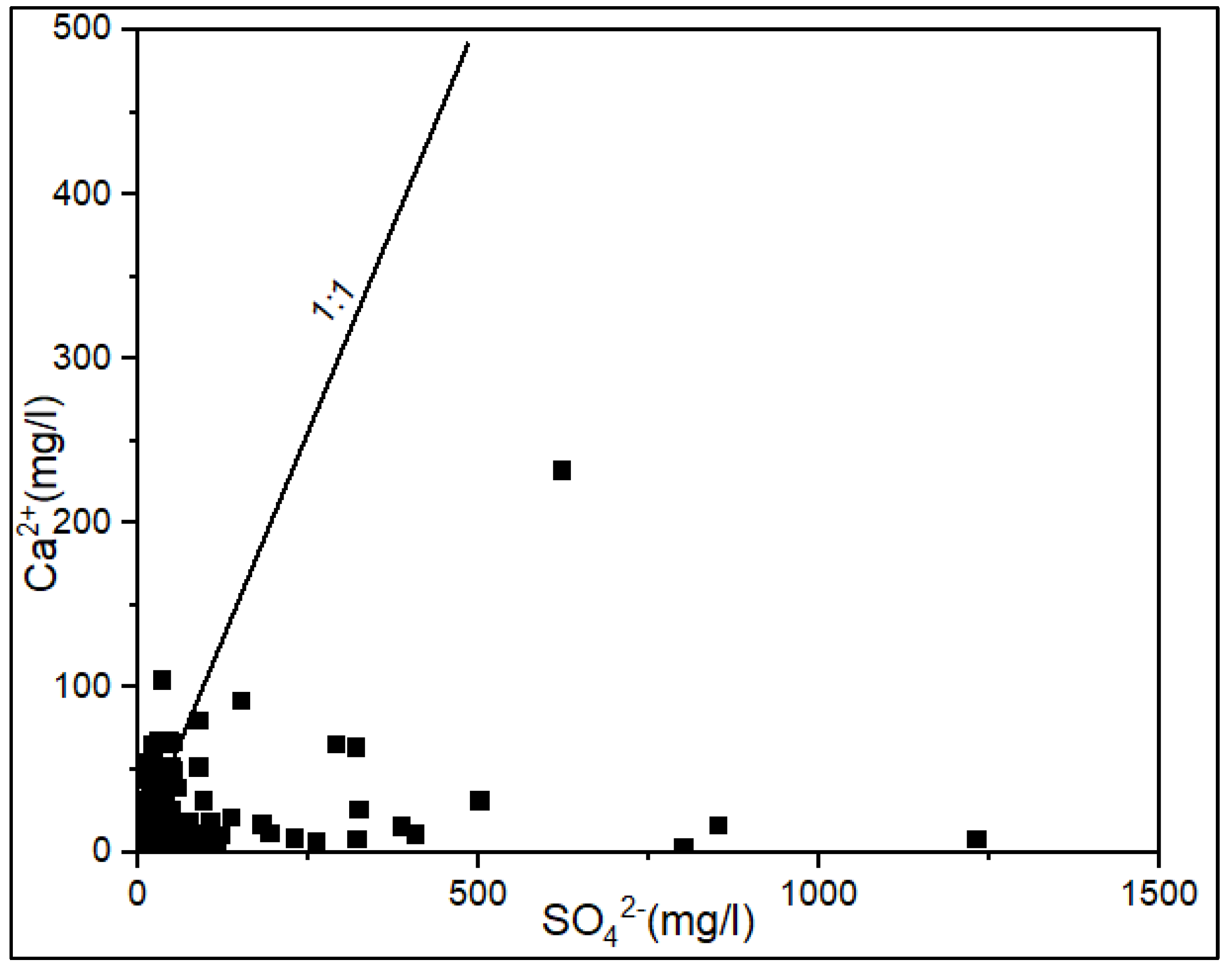

| SO42- | Mg/l | 3.0 | 1230.0 | 35.3 | 89.5 | 400 | 400 | 5.3 |

| NO3- | Mg/l | 0 | 129.9 | 1.1 | 5.5 | 50 | 10 | 1.4 |

| Na+ | Mg/l | 10.4 | 3410.0 | 221.0 | 416.9 | 200 | 200 | 49.3 |

| K+ | Mg/l | 2.0 | 83.0 | 11.0 | 12.7 | 20 | 20 | 10.7 |

| Ca2+ | Mg/l | 2.8 | 233.0 | 20.0 | 26.5 | 200 | 250 | 2.7 |

| Mg2+ | Mg/l | 1.0 | 151.0 | 11.1 | 18.2 | 150 | 100 | 2.7 |

| TH | Mg/l | 11.6 | 1125.4 | 11.6 | 120.7 | 500 | 500 | 1.4 |

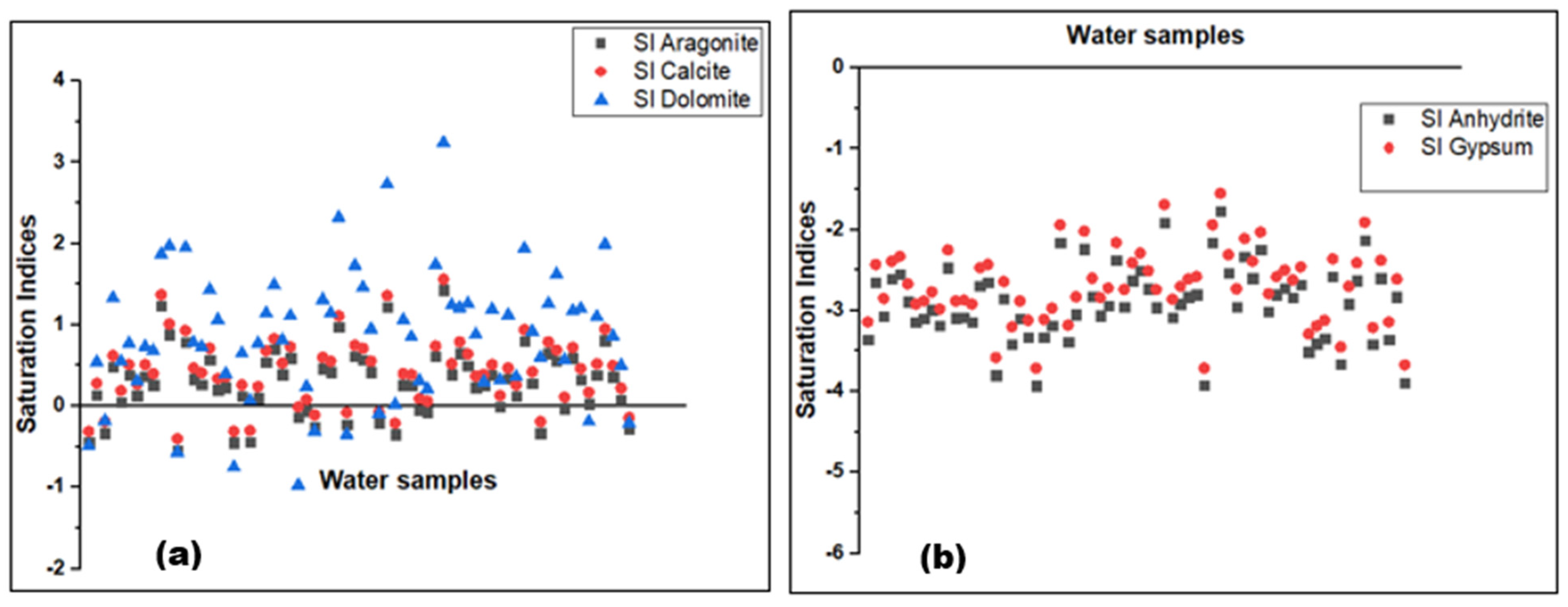

| SI Calcite | Mg/l | -0.4 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| SI dolomite | Mg/l | -1.0 | 3.2 | 0.9 | 0.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| SI aragonite | Mg/l | -0.5 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| SI Anhydrite | Mg/l | -3.9 | -1.8 | -2.9 | -2.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| SI gypsum | Mg/l | -3.7 | -1.6 | -2.7 | -2.7 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| SI Halie | Mg/l | -8.8 | -4.4 | -6.9 | -6.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Na+/Cl-ratio | 1.0 | 306.6 | 5.6 | 22.7 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

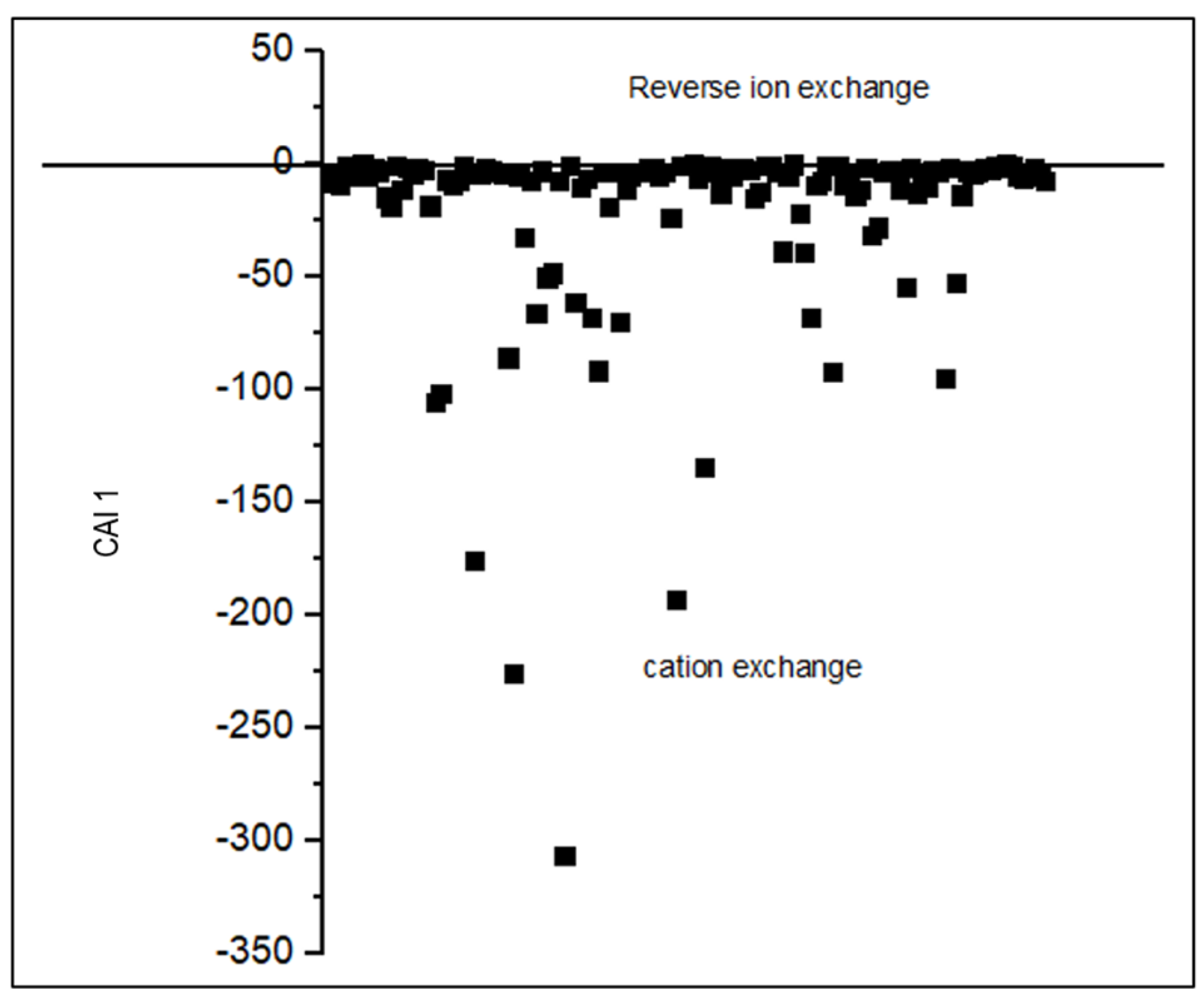

| CAI 1 | -306.7 | -0.01 | -4.9 | -22.2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

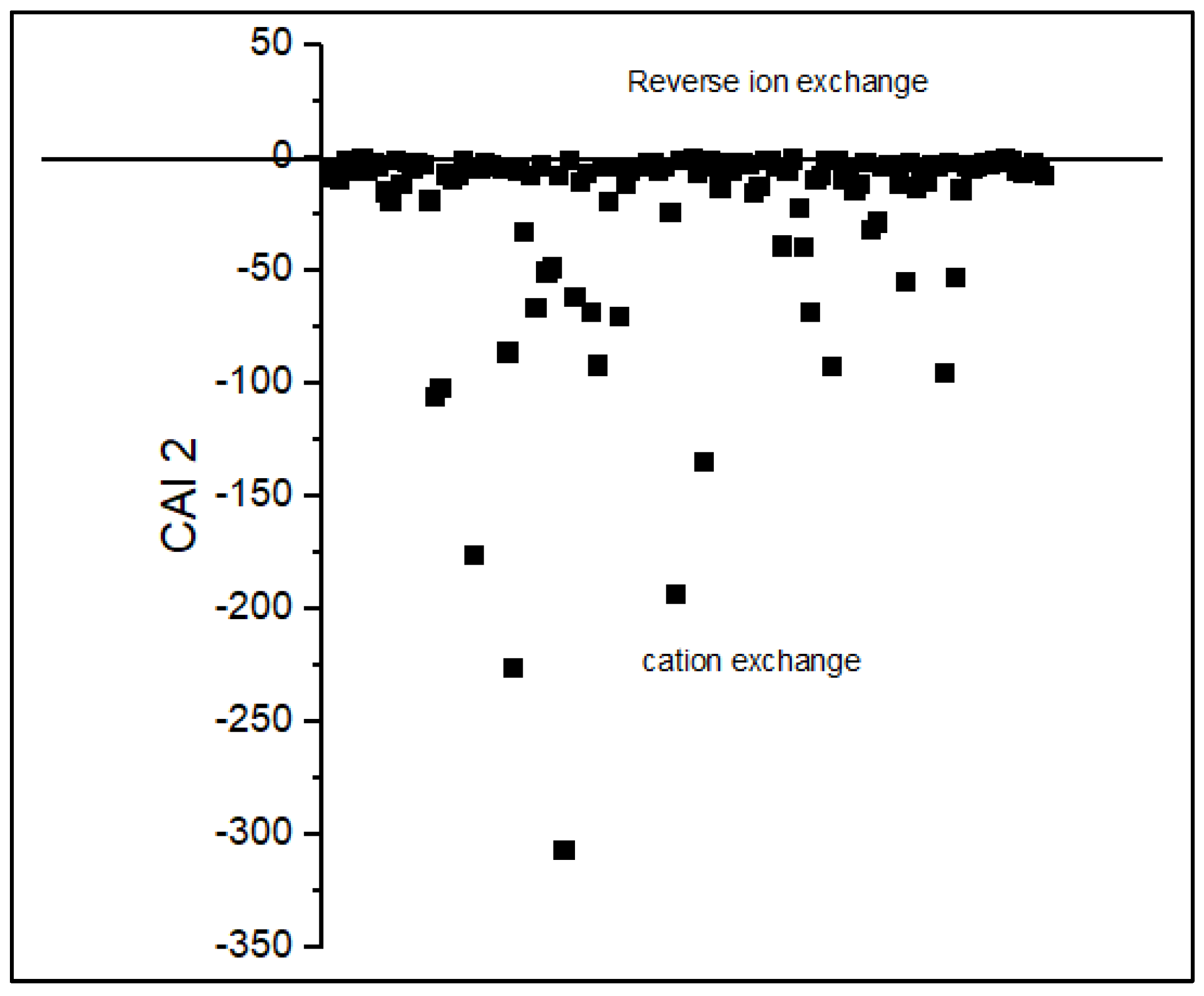

| CAI 2 | -1.1 | -0.01 | -0.7 | -0.7 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

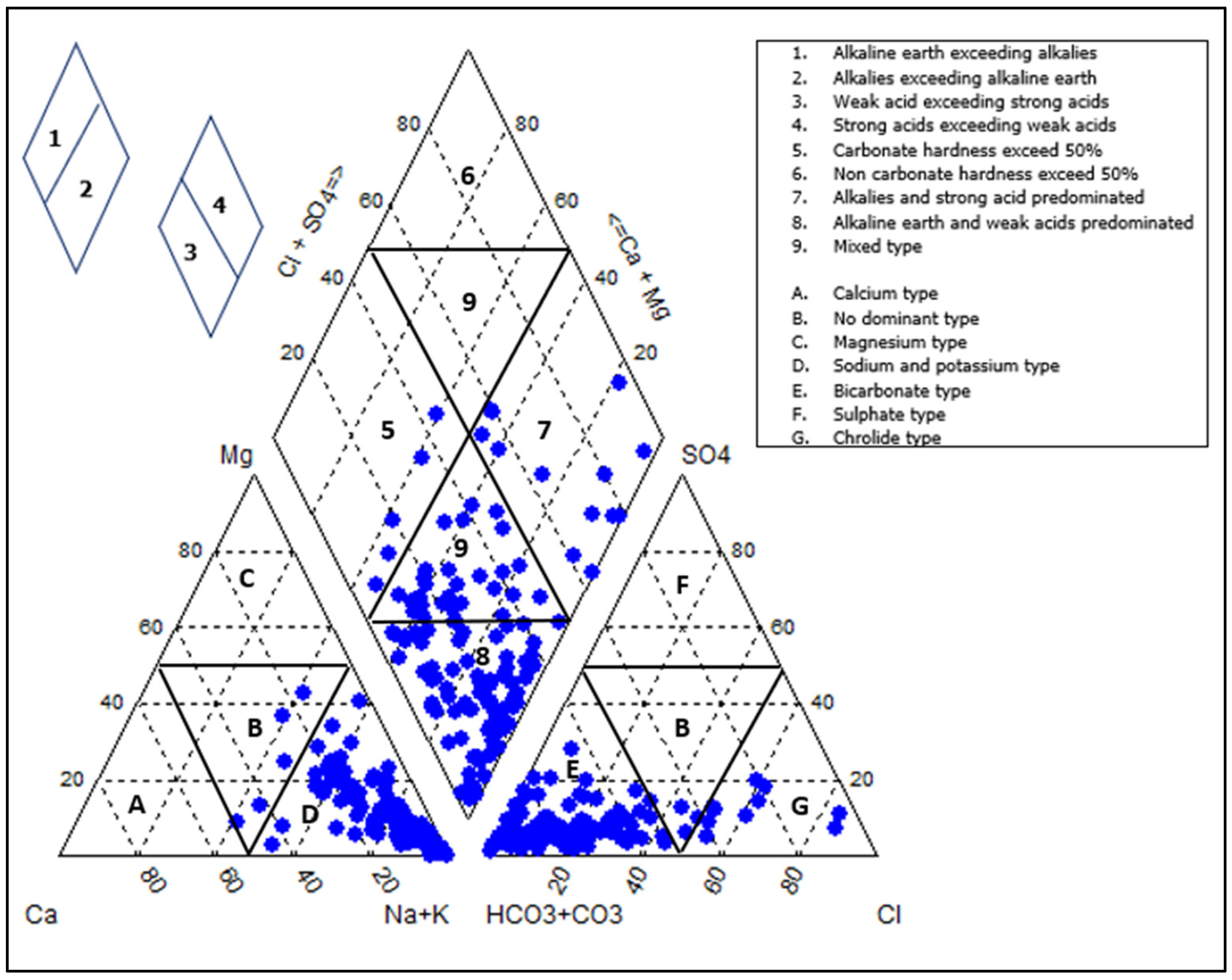

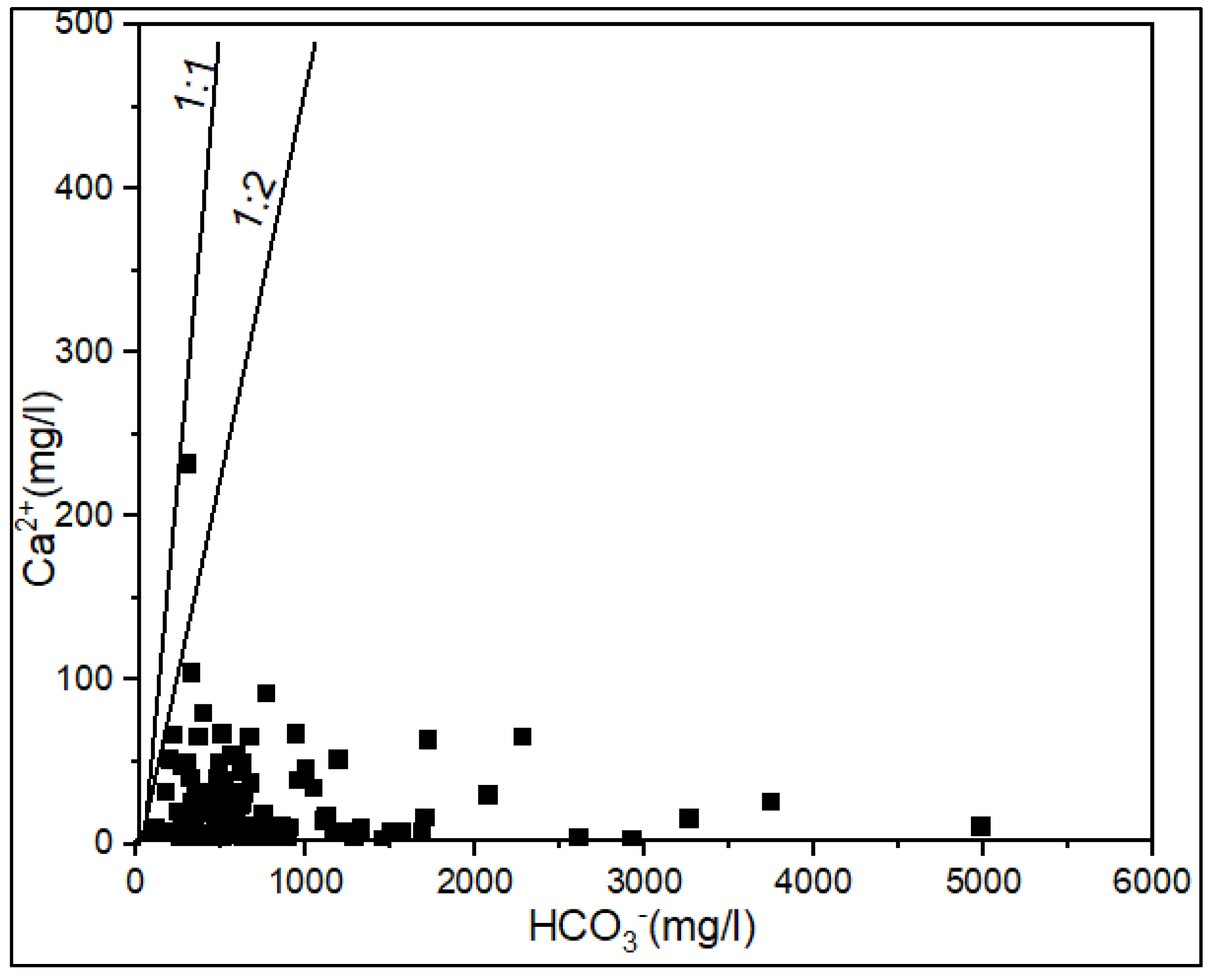

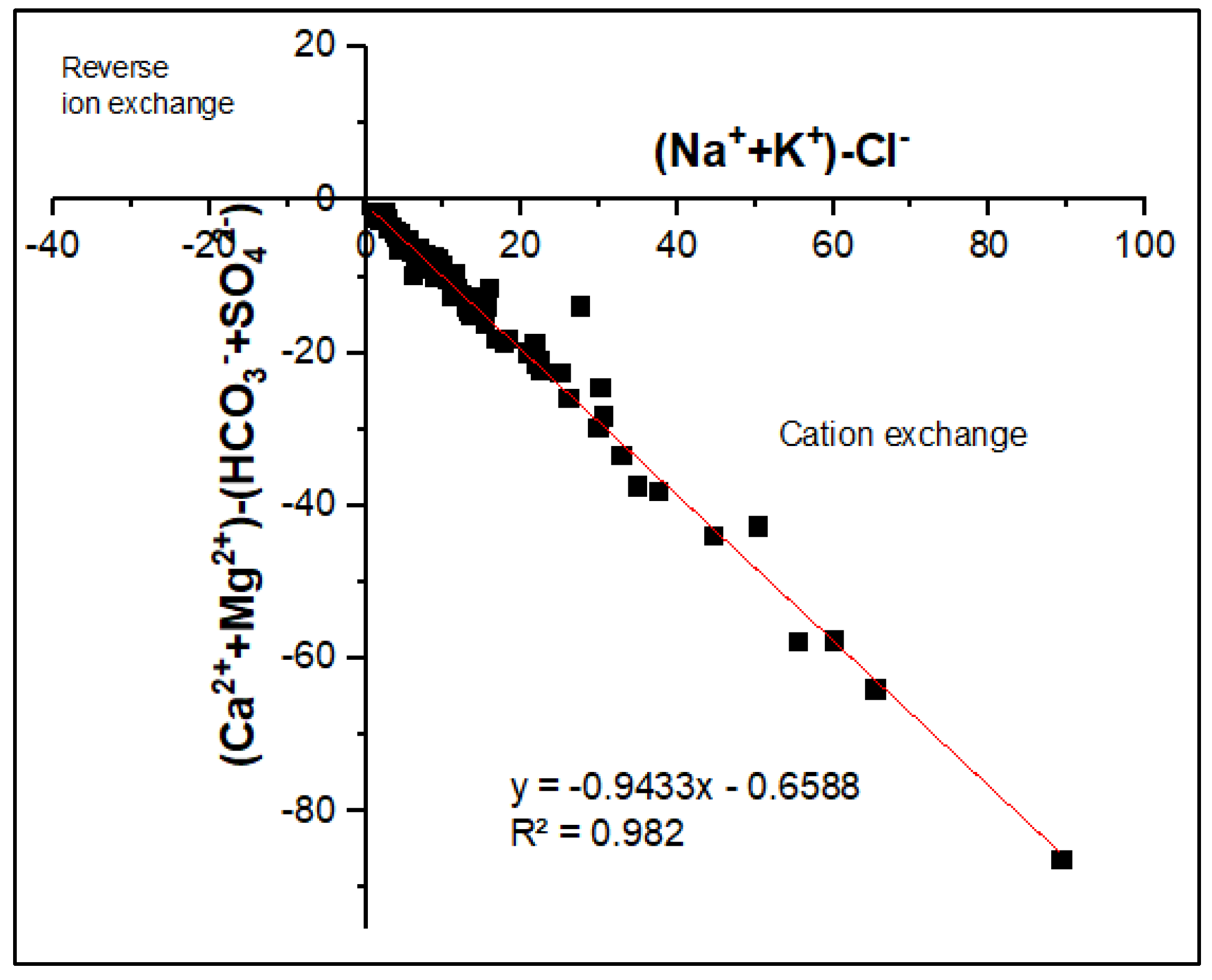

3.2. Processes Controlling the Groundwater Chemistry

3.2.1. Water-Rock Interaction and Origin of Groundwater Mineralization

3.2.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | |

| EC | 0.879 | 0.027 | 0.009 | 0.011 |

| TDS | 0.908 | 0.052 | 0.015 | 0.001 |

| Cl- | 0.683 | 0.087 | 0.032 | 0.107 |

| SO42- | 0.838 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.014 |

| NO3- | 0.021 | 0.410 | 0.390 | 0.001 |

| HCO3- | 0.434 | 0.130 | 0.018 | 0.187 |

| Na+ | 0.974 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.006 |

| K+ | 0.054 | 0.364 | 0.327 | 0.106 |

| Ca2+ | 0.014 | 0.724 | 0.017 | 0.005 |

| Mg2+ | 0.013 | 0.713 | 0.018 | 0.079 |

| pH | 0.030 | 0.171 | 0.227 | 0.431 |

| Eigenvalue | 4.847 | 2.682 | 1.060 | 0.948 |

| Variability (%) | 44.062 | 24.380 | 9.634 | 8.617 |

| Cumulative % | 44.062 | 68.442 | 78.077 | 86.693 |

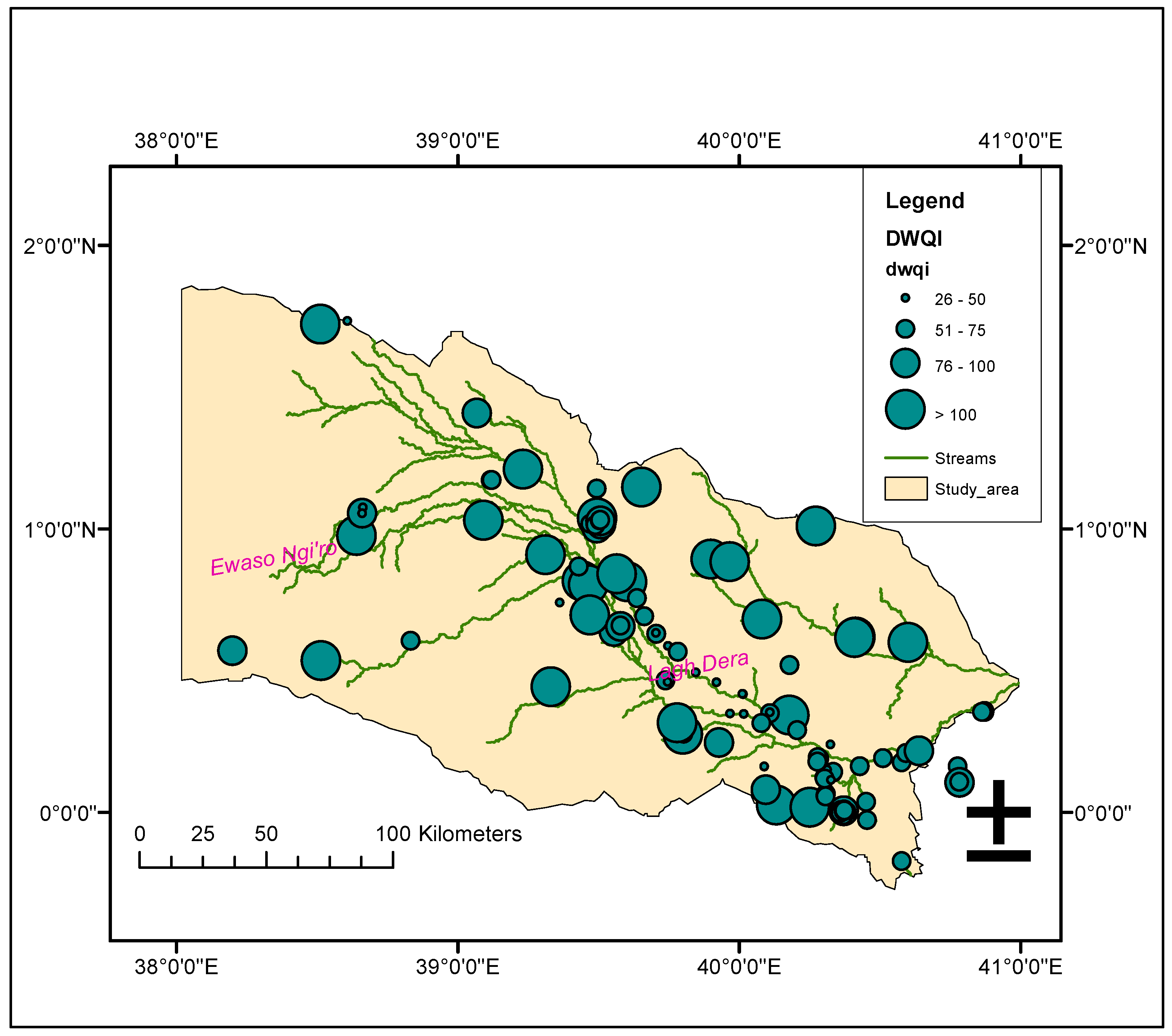

3.3. Drinking Water Quality

| WQI | Rating class | Percent of samples |

|---|---|---|

| 0 -25 | Excellent | 0 |

| 26 -50 | Good | 23.26 |

| 51 - 75 | Poor | 44.19 |

| 76 - 100 | Very poor | 12.4 |

| >100 | Unsuitable | 20.15 |

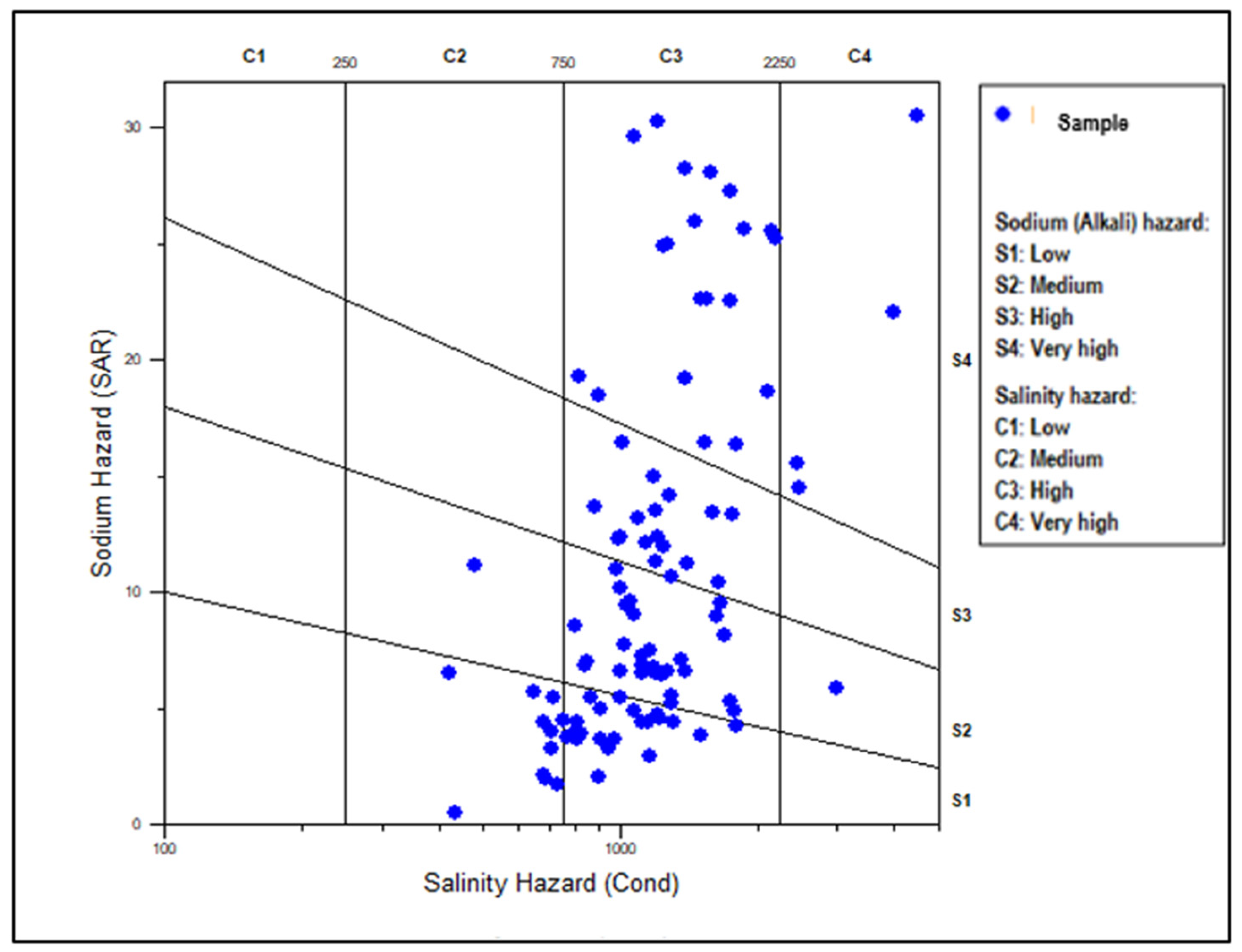

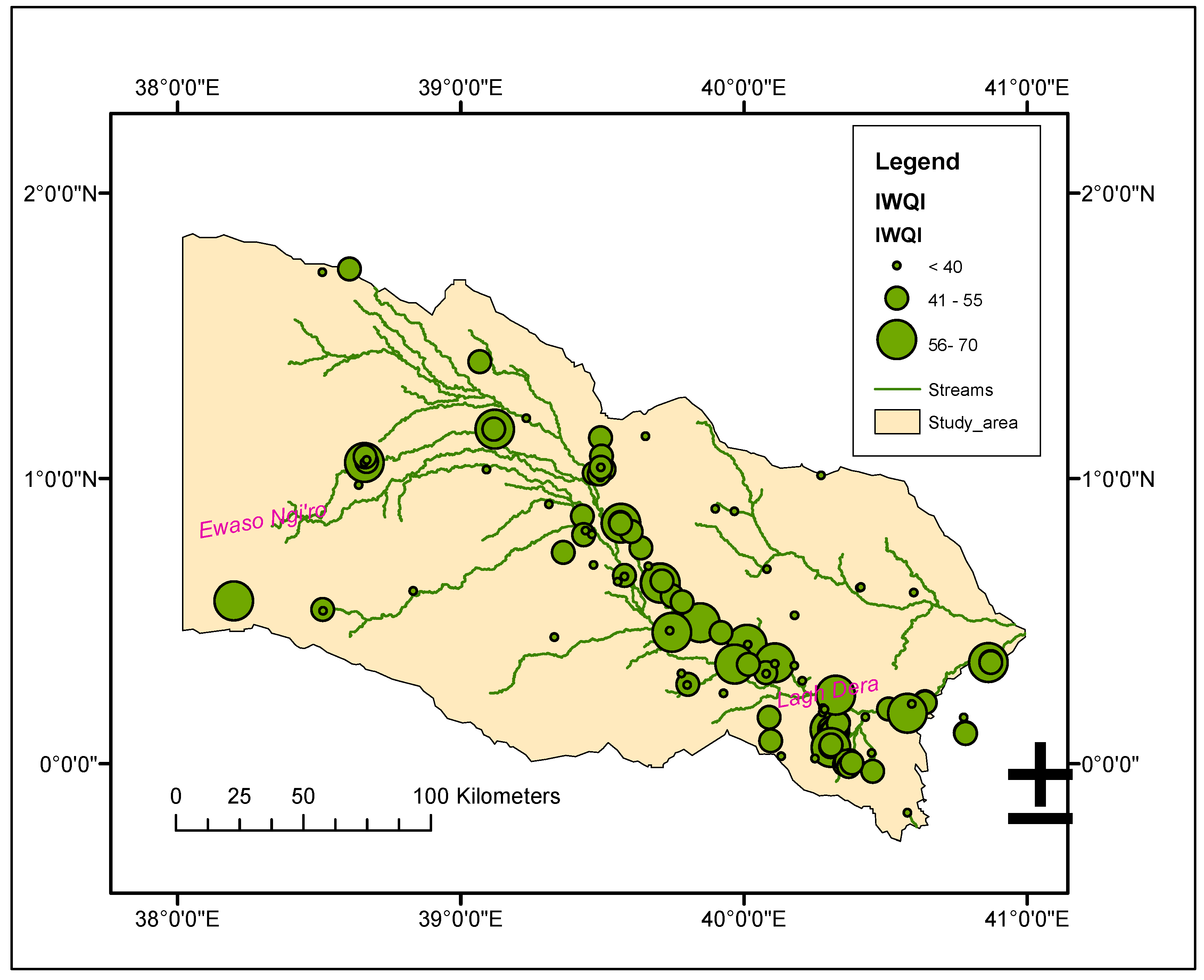

3.4. Irrigation Water Quality

| Water use restrictions | IWQI | |

| No restriction (NR) | 85-100 | 0 |

| Low restriction (LR) | 70-85 | 0 |

| Moderate restriction (MR) | 55-70 | 12.4 |

| High restriction (HR) | 40-55 | 45.7 |

| Severe restriction (SR) | 0-40 | 41.9 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EC | Electrical Conductivity |

| TDS | Total Dissolved Solids |

| WQI | Water Quality Index |

| IWQI | Irrigation Water Quality Index |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WASREB | Water Services Regulatory Board |

| NOCK | National Oil Corporation Kenya |

References

- Olago, D. O. Constraints and solutions for groundwater development, supply and governance in urban areas in Kenya. Hydrogeol J 2019 27, 1031–1050. [CrossRef]

- Osman, A. D. Groundwater quality in Wajir (Kenya) shallow aquifer: An examination of the association between water quality and water- borne diseases in children. Ph. D thesis, 2012 http://hdl.handle.net/1959.9/308716.

- Okello, C.; Tomasello, B.; Greggio, N.; Wambiji, N.; Antonellini, M. Impact of Population Growth and Climate Change on the Freshwater Resources of Lamu Island, Kenya. Water. 2015 7(3):1264-1290. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wu, J.; Qian, H. Hydrochemical appraisal of groundwater quality for drinking and irrigation purposes and the major influencing factors: a case study in and around Hua County, China. Arab J Geosci 2016, 9, 15. [CrossRef]

- Nyoro, J. K. Agriculture and rural growth in Kenya. Tegemeo Institute. 2019 http://41.89.96.81:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/2393.

- D’Alessandro, S.; Caballero, J.; Simpkin, S.; Lichte, J. Kenya agricultural risk assessment. World Bank Group. 2015. https://bit. ly/2RnCyhP.

- Ericksen, P.J.; Said, M.Y.; Leeuw, J.D.; Silvestri, S.; Zaibet, L.; Kifugo, S.C.; Sijmons, K.; Kinoti, J.; Ng'ang'a, L.; Landsberg, F.; Stickler, M. Mapping and valuing ecosystem services in the Ewaso Ng’iro Ng'iro watershed. 2011. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/12483.

- Rakotoarisoa, M.; Massawe, S. C.; Mude, A. G.; Ouma, R.; Freeman, H. A.; Bahiigwa, G.; & Karugia, J. T. Investment opportunities for livestock in the North Eastern Province of Kenya: a synthesis of existing knowledge. 2008 https://hdl.handle.net/10568/187.

- Muya, E. M.; Obanyi, S.; Ngutu, M.; Sijali, I. V.; Okoti, M.; Maingi, P. M.; Bulle, H. The physical and chemical characteristics of soils of Northern Kenya Aridlands: Opportunity for sustainable agricultural production. Journal of Soil Science and Environmental Management, 2011 2(1), 1-8. http://www.academicjournals.org/JSSEM.

- Aghazadeh, N.; Chitsazan, M.; Golestan, Y. Hydrochemistry and quality assessment of groundwater in the Ardabil area, Iran. Applied Water Science, 2017, 7, pp.3599-3616. [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, W. M. Hydrogeochemical processes in arid and semi-arid regions—focus on North Africa. In Understanding Water in a Dry Environment 2003, 267-304. CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Coetsiers , M.; Walraevens, K. Chemical characterization of the Neogene Aquifer, Belgium. Hydrogeol J 2006, 14, 1556–1568. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kumari, K.; Singh, U.K. and Ramanathan, A.L. Hydrogeochemical processes in the groundwater environment of Muktsar, Punjab: conventional graphical and multivariate statistical approach. Environmental Geology, 2009, 57, pp.873-884. [CrossRef]

- Chenini, I.; Farhat, B; Ben Mammou, A. Identification of major sources controlling groundwater chemistry from a multilayered aquifer system. Chemical Speciation & Bioavailability, 2010, 22(3), pp.183-189. [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R.; Brindha, K.; Murugan, R. and Elango, L. Influence of hydrogeochemical processes on temporal changes in groundwater quality in a part of Nalgonda district, Andhra Pradesh, India. Environmental Earth Sciences, 2012, 65, pp.1203-1213. [CrossRef]

- Freeze, R. A.; Cherry, J. A. Groundwater 1979. Prentice-Hall Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

- Etikala, B.; Adimalla, N.; Madhav, S.; Somagouni, S. G.; Keshava Kiran Kumar, P. L. Salinity problems in groundwater and management strategies in arid and semi-arid regions. Groundwater geochemistry: pollution and remediation methods, 2021, 42-56. [CrossRef]

- Hailu, H.; Haftu, S. Hydrogeochemical studies of groundwater in semi-arid areas of northern Ethiopia using geospatial methods and multivariate statistical analysis techniques. Appl Water Sci 2023, 13, 86. [CrossRef]

- Laghrib, F.; Bahaj, T.; El Kasmi, S.; Hilali, M.; Kacimi, I.; Nouayti, N.; Dakak, H.; Bouzekraoui, M.; El Fatni, O. and Hammani, O. Hydrogeochemical study of groundwater in arid and semi-arid regions of the Infracenomanian aquifers (Cretaceous Errachidia basin, Southeastern Morocco). Using hydrochemical modeling and multivariate statistical analysis. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 2024, 209, p.105132. [CrossRef]

- Toth, J. The role of regional gravity flow in the chemical and thermal evolution of ground water. In Proc. First Canadian/American Conference on Hydrogeology, Practical Applications of Ground Water Geochemistry, Worthington, Ohio, 1984 (pp. 3-39). National Water Well Association and Alberta Research Council.

- Lakshmanan, E.; Kannan, R. and Kumar, M.S. Major ion chemistry and identification of hydrogeochemical processes of ground water in a part of Kancheepuram district, Tamil Nadu, India. Environmental geosciences, 2003, 10(4), pp.157-166. [CrossRef]

- Tizro, A. T.; Voudouris, K. S. Groundwater quality in the semi-arid region of the Chahardouly basin, West Iran. Hydrol Process 2008, 22, (16):3066 3078. [CrossRef]

- Chenini, I.; Mammou, A. B.; Turki, M. M.; Groundwater resources of a multilayered aquiferous system in arid area: Data analysis and water budgeting. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 5, 361–374. [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, M. V.; Chidambaram, S.; Srinivasamoorthy, K. Statistical analysis of the hydrogeochemical evolution of groundwater in hard and sedimentary aquifers system of Gadilam river basin, South India, Journal of King Saud University - Science, 2010 Volume 22, Issue 3, 133-145. [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, F.K.; Nazzal, Y.; Jafri, M.K. Naeem, M.; and Ahmed, I. Reverse ion exchange as a major process controlling the groundwater chemistry in an arid environment: a case study from northwestern Saudi Arabia. Environ Monit Assess 2015, 187, 607. [CrossRef]

- Sajil Kumar, P.J. and James, E.J. Identification of hydrogeochemical processes in the Coimbatore district, Tamil Nadu, India. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 2016 61(4), pp.719-731. [CrossRef]

- Kura, N.U.; Ramli, M.F.; Sulaiman, W.N.A.; Ibrahim, S.; Aris, A.Z. and Mustapha, A.; 2013. Evaluation of factors influencing the groundwater chemistry in a small tropical island of Malaysia. International journal of environmental research and public health, 10(5), pp.1861-1881. [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, P.; Somashekar, R. K. Principal component analysis and hydrochemical facies characterization to evaluate groundwater quality in Varahi river basin, Karnataka state, India. Appl Water Sci 2017 7, 745–755. [CrossRef]

- Wenning, R. J.; Erickson, G. A. Interpretation and analysis of complex environmental data using chemometric methods. Trends in analytical chemistry, 1994. 13, 446-457. [CrossRef]

- Helena, B.; Pardo, R.; Vega, M.; Barrado, E.; Fernandez, J.M; Fernandez, L. Temporal evolution of groundwater composition in an alluvial aquifer (Pisuerga River, Spain) by principal component analysis. Water research, 2000, 34(3), pp.807-816. [CrossRef]

- Alassane, A.; Trabelsi, R.; Dovonon, L.F.; Odeloui, D.J.; Boukari, M.; Zouari, K.; Mama, D. Chemical evolution of the continental terminal shallow aquifer in the south of coastal sedimentary basin of Benin (West-Africa) using multivariate factor analysis. Journal of water resource and protection, 2015 7(6), pp.496-515. [CrossRef]

- Okiongbo, K.S.; Douglas, R.K. Evaluation of major factors influencing the geochemistry of groundwater using graphical and multivariate statistical methods in Yenagoa city, Southern Nigeria. Applied water science, 2015 5, pp.27-37. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.E. A User’s User's Guide to Principal Components Wiley 1991, New York 1.

- Meglen, R.R. Examining large databases: a chemometric approach using principal component analysis. Marine Chemistry, 1992, 39(1-3), pp.217-237. [CrossRef]

- Jalali, M. Application of Multivariate analysis to study water chemistry of groundwater in a semi-arid aquifer, Malayer, Western Iran. Desalination and Water Treatment, 2010, 19(1-3), pp.307-317. [CrossRef]

- Singhal, Anupam, Rajiv Gupta, A. N. Singh, and A. Shrinivas. Assessment and monitoring of groundwater quality in semi–arid region. Groundwater for sustainable development. 2020, 11: . [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.K. An index number system for rating water quality. J Water Pollut Control Fed, 1965 37(3), pp.300-306.

- Brown, Robert M., Nina I. McClelland, Rolf A. Deininger, and Ronald G. Tozer. "A water quality index-do we dare." Water and sewage works 2070, 117, no. 10.

- Ott, W. R. water quality indices: a survey of indices used in the United States. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, Office of Monitoring and Technical Support, 1978.

- Boah, D, K.; Twum, S. B.; Pelig-Ba, K. B. "Mathematical computation of water quality index of Vea dam in upper east region of Ghana." Environ Sci 2015, 3, no. 1: 11-16.

- Adimalla, N.; Li, P.; Venkatayogi, S. Hydrogeochemical Evaluation of Groundwater Quality for Drinking and Irrigation Purposes and Integrated Interpretation with Water Quality Index Studies. Environ. Process. 2018 5, 363–383. [CrossRef]

- Batarseh, M.; Imreizeeq, E.; Tilev, S.; Al Alaween, M.; Suleiman, W.; Al Remeithi, A.M.; Al Tamimi, M.K.; Al Alawneh, M.; Assessment of groundwater quality for irrigation in the arid regions using irrigation water quality index (IWQI) and GIS-Zoning maps: Case study from Abu Dhabi Emirate, UAE. Groundwater for Sustainable Development, 2021, 14, p.100611. [CrossRef]

- M'nassri, S.; El Amri, A.; Nasri, N.; Majdoub, R. Estimation of irrigation water quality index in a semi-arid environment using data-driven approach. Water Supply, 2022 22(5), pp.5161-5175. [CrossRef]

- Gad, M.; Saleh, A.H.; Hussein, H.; Elsayed, S.; Farouk, M.; Water quality evaluation and prediction using irrigation indices, artificial neural networks, and partial least square regression models for the Nile River, Egypt. Water, 2023. 15(12), p.2244. [CrossRef]

- Anyango, G.W.; Bhowmick, G.D.; Bhattacharya, N.S. A Critical Review of Irrigation Water Quality Index and Water Quality Management Practices in Micro-Irrigation for Efficient Policy Making. Desalination and Water Treatment, 2024, p.100304. [CrossRef]

- Mufeed, B.; Emad, I.; Seyda, T.; Mohammad, A.; Wael, S.; Abdulla, M.; Mansoor, K.T. Majdy, A. Assessment of groundwater quality for irrigation in the arid regions using irrigation water quality index (IWQI) and GIS-Zoning maps: a case study from Abu-Dhabi, Emirate, UAE. Groundwater for Sustainable Development Journal, 202114, p.100611. [CrossRef]

- Swarzenski, W. V.; Mundorff, M. J. Geohydrology of North Eastern Province, Kenya, USGS Water Supply Paper, 1977, 1757-N, 68.

- Mwango, F. K.; Muhangú, B. C.; Juma, C. O.; Githae, I. T. Groundwater resources in Kenya. In: Managing Shared Aquifer Resources in Africa. ISARM-AFRICA, 2002Tripoli, 2002 pp. 93–100.

- GIBB (Eastern Africa) Ltd.; Study of the Merti Aquifer. Kenya Country Office: final report 2004. volume 1 - main report.

- Mumma, A.; Lane, M.; Kairu, E.; Tuinhof, A. and Hirji, R. Kenya groundwater governance. Case study Report. 2011 http://www.groundwatergovernance.org/fileadmin/user_upload/groundwatergovernance/docs/Country_studies/GWGovernanceKenya.pdf .

- Kuria, D.N. and Kamunge, H.N.; 2013. Merti Aquifer Recharge zones determination using geospatial technologies. http://hdl.handle.net/123456789/51.

- EarthWater Ltd. (2012). Phase 1 – Aquifer Monitoring. Merti Aquifer Study. Nairobi.

- IGAD Design and development of a data system for the application of managed aquifer recharge (MAR) in the Merti aquifer. Technical Report Inland WaternResources Management Programme. 2015. https://www.un-igrac.org/special-project/igad-mar.

- Blandenier, L.; Recharge quantification and continental freshwater lens dynamics in arid regions: application to the Merti aquifer (Eastern Kenya). University of Neuchâtel Microsoft Word 2015,12.03 Final.docx (rero.ch).

- Krhoda, G.; Amimo, M.O. Groundwater quality prediction using logistic regression model for Garissa county. Africa Journal of Physical Sciences, 2019, 3, pp.13-27.

- Githinji, T.W.; Dindi, E.W.; Kuria, Z.N.; Olago, D.O. Application of analytical hierarchy process and integrated fuzzy-analytical hierarchy process for mapping potential groundwater recharge zone using GIS in the arid areas of Ewaso Ng'iro–Lagh Dera Basin, Kenya. HydroResearch, 2022, 5, pp.22-34. [CrossRef]

- Sklash, M.G.; Mwangi, M.P. An Isotopic Study of Groundwater Supplies in the Eastern Province of Kenya. J. Hydrol. 1991, 128, 257–275. [CrossRef]

- Lane,I. A Preliminary Assessment of the Hydrogeology and Hydrochemistry of the Merti Aquifer (North Eastern Province, Kenya: and Lower Juba. Somalia. 1995.

- Gachanja, A.; Tole, M. Management of Ground Water Resources of The MertiAquifer Preliminary Report. 2002. Nairobi.

- Reeves, C.V.; Karanja, F.M. and MacLeod, I.N. Geophysical evidence for a failed Jurassic rift and triple junction in Kenya. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 1987 81(2-3), pp.299-311. [CrossRef]

- Greene, L.C.; Richards, D.R.; Johnson, R.A.; Crustal structure and tectonic evolution of the Anza rift, northern Kenya. Tectonophysics, 1991, 197(2-4), pp.203-211. [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, W. Mesozoic and early tertiary rift tectonics in East Africa. Seismology and relate sciences in East Africa. Tectonophysics 1992, 209, 115–137. [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, W.; Morley, C.K. Structural and stratigraphic evolution of the Anza rift, Kenya.Tectonophysics 1994, 236 (1–4), 93–115. [CrossRef]

- Matheson, F. J. Geology of the Garbatula Area, (Degree Sheet 37, NE). Report no. 1971 -88. Geological Survey of Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Dindi, E.W.; Crustal structure of the Anza graben from gravity and magnetic investigations. Tectonophysics, 1994, 236(1-4), pp.359-371. [CrossRef]

- National Oil Corporation Kenya (NOCK). Geological Map of Kenya with Bouguer Gravity Contours. Nairobi, Kenya. 1987 Ministry of Energy and Regional Development.

- ISO. Water quality–determination of selected elements by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). 2007, Second edition 2007-08.

- Piper, A.; M. A graphic procedure in the geochemical interpretation of water-analyses. Transactions, American Geophysical Union, 1944 25, 914–928. [CrossRef]

- Abidi, H. J.; Farhat, B.; Ben Mammou, A.; Oueslati, N. Characterization of recharge mechanisms and sources of groundwater salinization in Ras Jbel coastal aquifer (Northeast Tunisia) using hydrogeochemical tools, environmental isotopes, GIS, and statistics. Journal of Chemistry, 2017(1), p.8610894. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A. K.; Singh, A. K. Hydrogeochemical investigation and groundwater quality assessment of Pratapgarh district, Uttar Pradesh. J Geol Soc India 2014, 83, 329–343. [CrossRef]

- Appelo, C. A. J.; Postma, D. 1996. Geochemistry, Groundwater & Pollution. Balkema, Rotterdam.

- Sandilands, D. Bivariate Analysis. In: Michalos, A.C. (eds) Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Springer, 2014 Dordrecht. [CrossRef]

- Trauth, M. H. Bivariate Statistics. In: MATLAB® Recipes for Earth Sciences. Springer, 2015, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Cotruvo, J. A. WHO guidelines for drinking water quality: first addendum to the fourth edition. J American Water Works Ass 2017, 109(7):44–51.

- WASREB, Kenya.; Water services regulatory board Drinking water quality and effluent monitoring guideline [online]. 2016 https://wasreb.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Drinking-Water-Guidelines-gwqem_Edited.pdf.

- Drechsel, P.; Marjani Zadeh, S.; Pedrero, F. (eds). Water quality in agriculture: Risks and risk mitigation. Rome, FAO & IWMI 2023. [CrossRef]

- Abdessamed, D.; Jodar-Abellan, A.; Ghoneim, S.S.M. et al. Groundwater quality assessment for sustainable human consumption in arid areas based on GIS and water quality index in the watershed of Ain Sefra (SW of Algeria). Environ Earth Sci 82, 510 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Darwish, M. H.; Megahed, H. A.; Sayed, A. G.; Abdalla, O.; Scopa, A.; Hassan, S. H. A. Hydro-Geochemistry and Water Quality Index Assessment in the Dakhla Oasis, Egypt. Hydrology, 2024 11(10), 160. [CrossRef]

- Meireles, A. C. M.; Andrade, E. M. D.; Chaves, L. C. G.; Frischkorn, H.; Crisostomo, L. A. A new proposal of the classification of irrigation water. Revista Ciência Agronômica, 2010, 41, 349-357.

- Ayers, R. S.; Westcot, D. W. Water quality for agriculture. 1985, Vol. 29. Rome: Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations.

- Tejashvini, A.; Subbarayappa, C. T.; Mudalagiriyappa.; Chowdappa, H. D.; Ramamurthy, V. Assessment of irrigation water quality for groundwater in Semi-Arid Region, Bangalore, Karnataka. Water Science, 2024, 38(1), 548–568. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, N. C.; Singh, V. S.; Rangarajan, R. Aquifer characteristics and its modeling around an industrial complex, Tuticorin, Tamil Nadu, India: A case study. J Earth Syst Sci 2009 118, 231–244 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Meybeck M. Global chemical weathering of surficial rocks estimated from river dissolved loads. American Journal of Science, 1987, 287, 401–428. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R. J.; Geochemical comparison of groundwater in areas of New England, New York, and Pennsylvania. Groundwater 1989 27(5):690–712 . [CrossRef]

- Krhoda, G. O. Groundwater assessment in sedimentary basins of eastern Kenya, Africa. In: Regional Characterization of Water Quality Baltimore Symposium: International Association of Hydrological Sciences. 1989, pp. 111–124.

- Chebotarev, I.I. Metamorphism of natural waters in the crust of weathering—2. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta 1955. 8, 137–170. [CrossRef]

- Luedeling, E.; Arjen, L. O.; Boniface, K.; Sarah, O.; Maimbo, M.; Keith, D. S. Fresh groundwater for Wajir—ex-ante assessment of uncertain benefits for multiple stakeholders in a water supply project in Northern Kenya. Front. Environ. Sci. 2015 3(16), 18. [CrossRef]

- Moujabber, M.E.; Samra, B.B.; Darwish, T. and Atallah, T. Comparison of different indicators for groundwater contamination by seawater intrusion on the Lebanese coast. Water resources management, 2006, 20, pp.161-180. [CrossRef]

- Sudaryanto and Naily, W. February. Ratio of major ions in groundwater to determine saltwater intrusion in coastal areas. In IOP conference series: earth and environmental science 2018 (Vol. 118, p. 012021). IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Chidambaram, S.; Sarathidasan, J.; Srinivasamoorthy, K.; Thivya, C.; Thilagavathi, R.; Prasanna, M. V.; Singaraja, C.; Nepolian, M. Assessment of hydrogeochemical status of groundwater in a coastal region of Southeast coast of India. Appl Water Sci2018, 8, 27. [CrossRef]

- Appelo, C. A. J.; Postma, D. Geochemistry, groundwater and pollution,2nd edn.Balkema, Rotterdam, 2005. 683 pp.

- Schoeller, H. Geochemistry of groundwater. In: Groundwaterstudies—an international guide for research and practice.UNESCO, 1977, Paris, Chap. 15, pp 1–18.

- Schoeller, H. Hydrodynamique lans lekarst (ecoulemented emmagusinement). Actes Colloques Doubronik, I, AIHS et UNESCO, 1965 pp 3–20. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/kip_articles/8272.

- García, G.M.; del V. Hidalgo, M.; Blesa, M.A. Geochemistry of groundwater in the alluvial plain of Tucuman province, Argentina. Hydrogeology Journal, 2001, 9, pp.597-610. [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Reza, A. H. M. S.; Roy, M. K. Hydrochemical evaluation of groundwater quality of the Tista floodplain, Rangpur, Bangladesh. Appl Water Sci 2019 9, 198. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, V.; Singh, D. S.; Surface and groundwater quality characterization of Deoria district, Ganga plain, India. Environ Earth Sci 2011 63:383–395. [CrossRef]

- Richards, L. A. Diagnosis and improvement of saline and alkali soils, 1954 vol 78. LWW, Philadelphia. US Government Printing Office.

- Wilcox, L. V. Classification and use of irrigation water (Circular 969). 1955 USDA, Washington. https://dn720401.ca.archive.org/0/items/classificationus969wilc/classificationus969wilc.pdf.

- Sidibe A. M.; Lin, X.; Koné, S.; 2019. Assessing groundwater mineralization process, quality, and isotopic recharge origin in the Sahel Region in Africa MDPI Water 2019, 11, 789; [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.; Atteia, O.; Ursula Salmon, S.; Siade, A.; Douglas, G. and Prommer, H. Identification and quantification of redox and pH buffering processes in a heterogeneous, low carbonate aquifer during managed aquifer recharge. Water Resources Research, 2016, 52(5), pp.4003-4025. [CrossRef]

- Singaraja, C.; Chidambaram, S.; Anandhan, P. Thivya, C.; Thilagavathi, R., Sarathidasan, J. Hydrochemistry of groundwater in a coastal region and its repercussion on quality, a case study—Thoothukudi district, Tamil Nadu, India. Arab J Geosci 2014, 7, 939–950. [CrossRef]

- Siddique, J.; Menggui, J.; Shah, M.H.; Shahab, A.; Rehman, F. and Rasool, U. Integrated approach to hydrogeochemical appraisal and quality assessment of groundwater from Sargodha District, Pakistan. Geofluids, 2020, 1, p.6621038. [CrossRef]

- Raju, N. J. Hydrogeochemical parameters for assessment of groundwater quality in the upper Gunjanaeru River basin, Cuddapah District, Andhra Pradesh, South India. Environ Geol 2007 52, 1067–1074. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed-Aslam, M. A.; Rizvi, S. S. Hydrogeochemical characterisation and appraisal of groundwater suitability for domestic and irrigational purposes in a semi-arid region, Karnataka state, India. Appl Water Sci 2020, 10, 237. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Weight (wi) |

|---|---|

| EC | 0.211 |

| Na+ | 0.204 |

| HCO3- | 0.202 |

| Cl- | 0.194 |

| SAR | 0.189 |

| Total | 1 |

| HCO3− (meq L−1) | Cl− (meq L−1) | Na+ (meq L−1) | SAR (meq L−1)1/2 | EC (μS cm−1) | Qi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ≤ HCO3− <1.5 | 1 ≤ Cl− < 4 | 2 ≤ Na+ < 3 | 2 ≤ SAR < 3 | 200 ≤ EC < 750 | 85-100 |

| 1.5 ≤ HCO3−<4.5 | 4 ≤ Cl− < 7 | 3 ≤ Na+ < 6 | 3 ≤ SAR < 6 | 750 ≤ EC < 1500 | 60-85 |

| 4.5 ≤ HCO3−<8.5 | 7 ≤ Cl− < 10 | 6 ≤ Na+ < 9 | 6 ≤ SAR < 12 | 1500 ≤ EC < 3000 | 35-60 |

| HCO3− < 1 or HCO3− ≥ 8.5 | 1< Cl− ≥ 10 | Na+ < 2 or Na+ ≥ 9 | 2 < SAR ≥ 12 | EC > 200 or EC ≥ 3000 | 0-35 |

| Variables | EC | TDS | Cl- | SO4- | NO3- | HCO3- | Na+ | K+ | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC | 1 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.78 | -0.05 | 0.60 | 0.93 | 0.14 | -0.05 | -0.02 | 0.14 |

| TDS | 0.96 | 1 | 0.66 | 0.83 | -0.06 | 0.77 | 0.93 | 0.143 | -0.08 | -0.06 | 0.19 |

| Cl- | 0.76 | 0.66 | 1 | 0.80 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.86 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.26 | -0.01 |

| SO42- | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.51 | 0.90 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| NO3- | -0.05 | -0.06 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 1 | -0.11 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.56 | 0.42 | -0.03 |

| HCO3- | 0.60 | 0.77 | 0.15 | 0.51 | -0.11 | 1 | 0.63 | 0.05 | -0.13 | -0.13 | 0.31 |

| Na+ | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.17 | 0.63 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.098 | 0.06 | 0.17 |

| K+ | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 1 | 0.41 | 0.61 | -0.20 |

| Ca2+ | -0.05 | -0.08 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.56 | -0.13 | 0.10 | 0.41 | 1 | 0.66 | -0.25 |

| Mg2+ | -0.02 | -0.06 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.42 | -0.13 | 0.06 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 1 | -0.19 |

| pH | 0.14 | 0.20 | -0.01 | 0.09 | -0.03 | 0.31 | 0.17 | -0.20 | -0.25 | -0.19 | 1 |

| Values in bold are different from 0 with a significance level of alpha=0.05 | |||||||||||

| Classification scheme | Categories | Ranges | Percent of samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cl-/ HCO3- | good quality | < 0.5 | 81.4 |

| slightly contaminated | 0.5 – 1.3 | 11.6 | |

| moderately contaminated | 1.3 – 2.8 | 5.4 | |

| highly contaminated | 2.8 – 6.6 | 0.7 | |

| extremely contaminated | 6.6 – 15.5 | 0.9 |

| Classification scheme | Categories | Ranges | Percent of samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAR (Richards 1954) | Excellent | <10 | 39.54 |

| Good | 10-18 | 17.83 | |

| Doubtful | 18-26 | 9.30 | |

| Unsuitable | >26 | 33.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).