Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

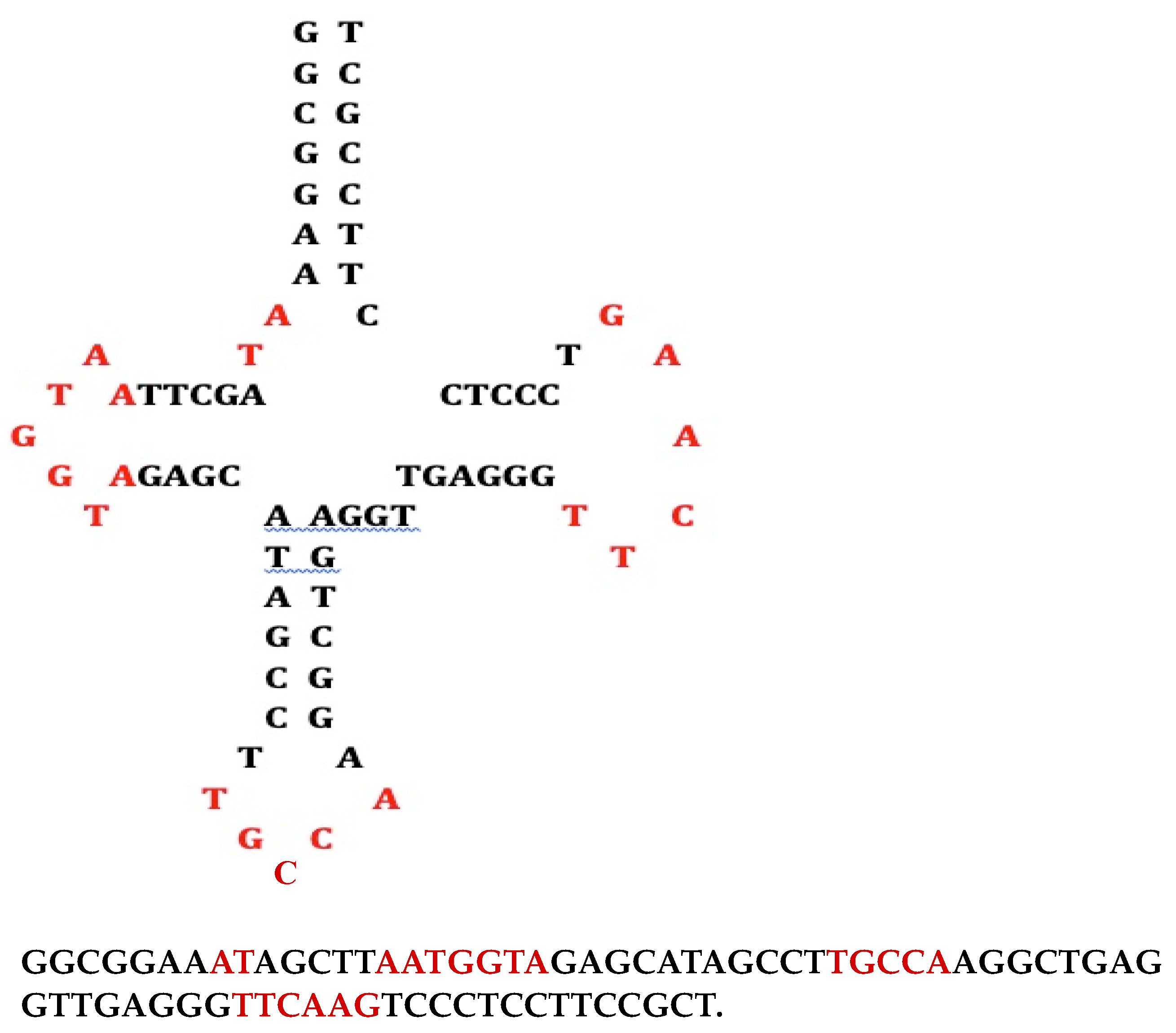

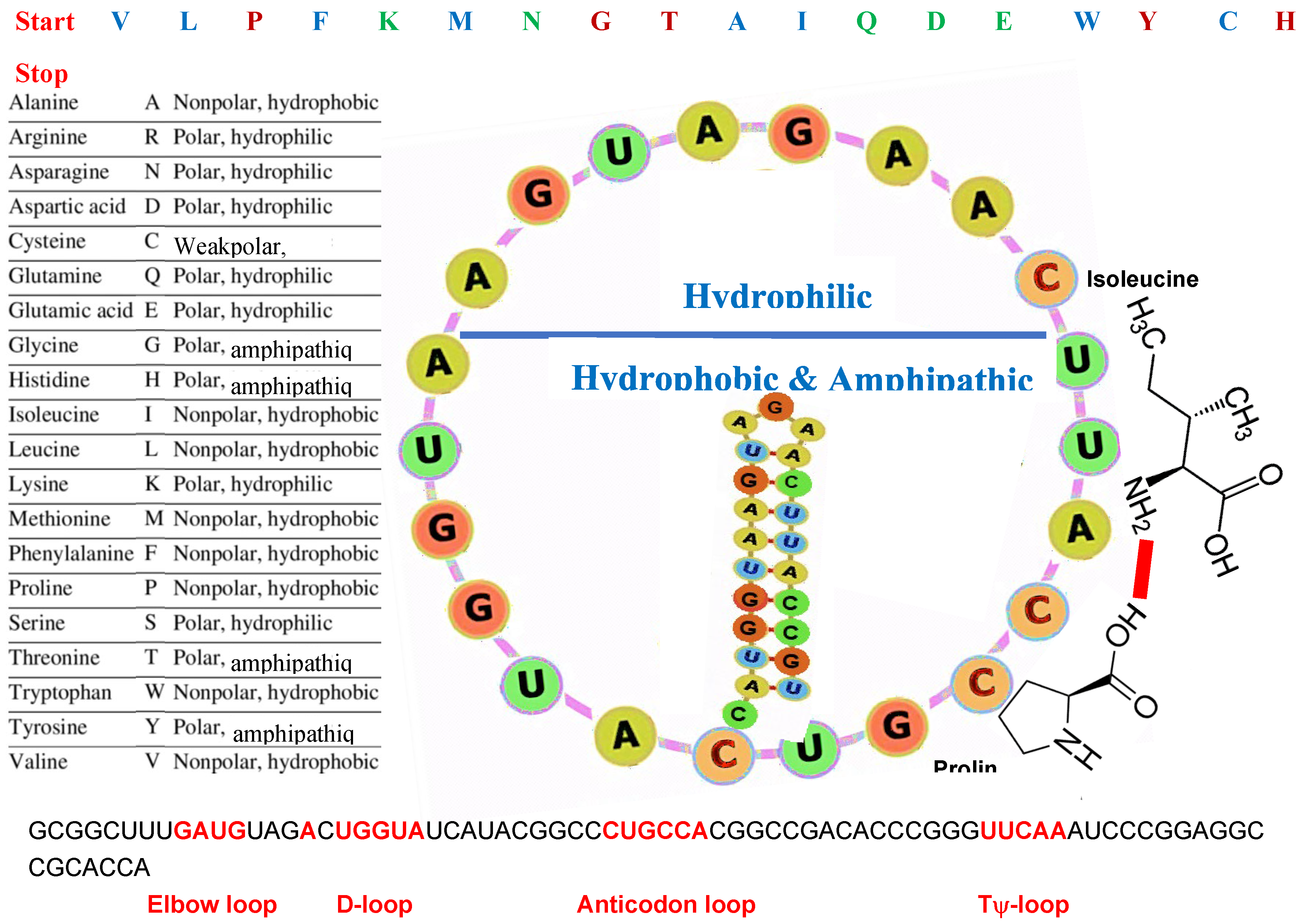

2.1. The Stereochemical Theory of the Origin of Life

2.2. Theoretical Criteria

2.3. Progressive Deciphering of the AL Ring

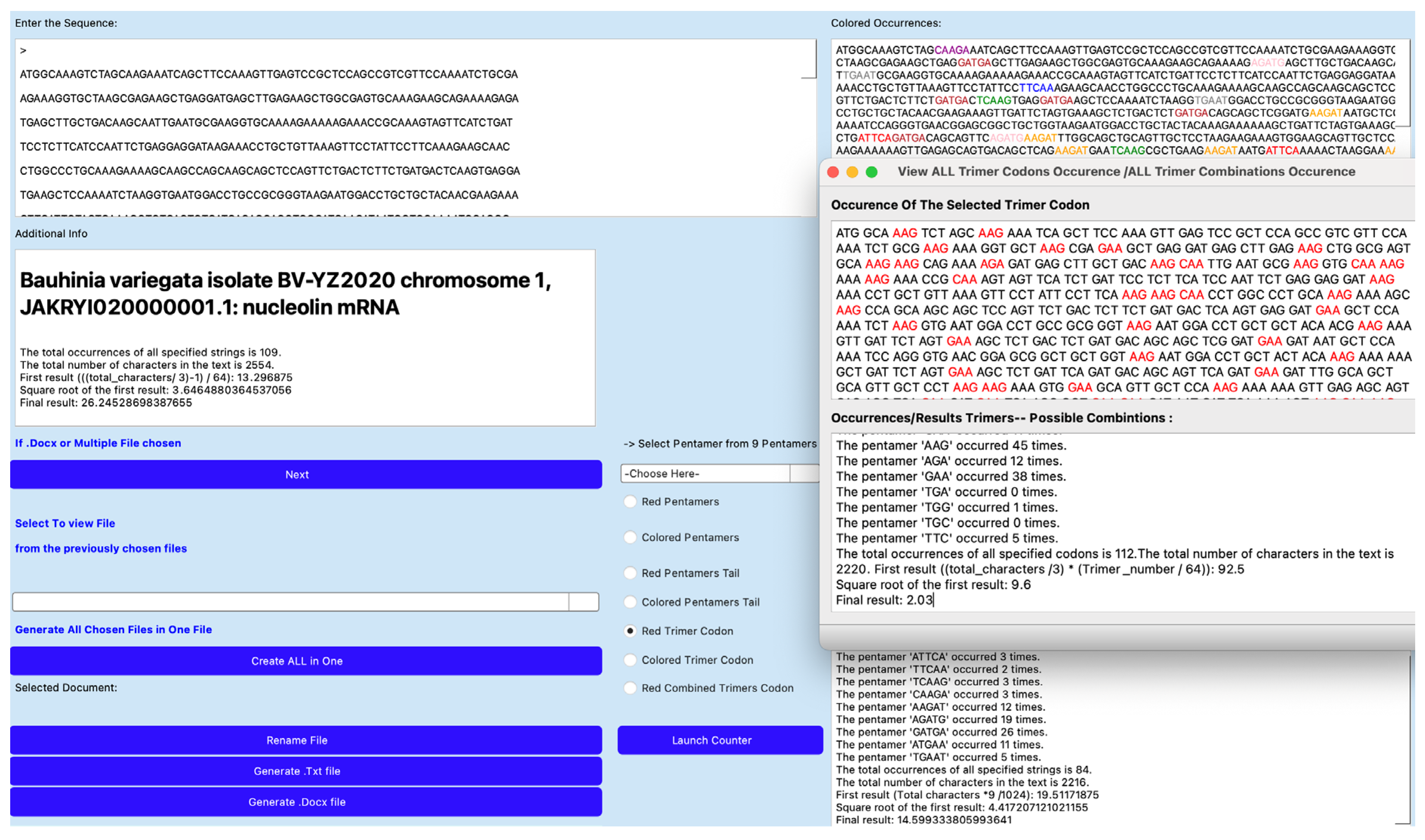

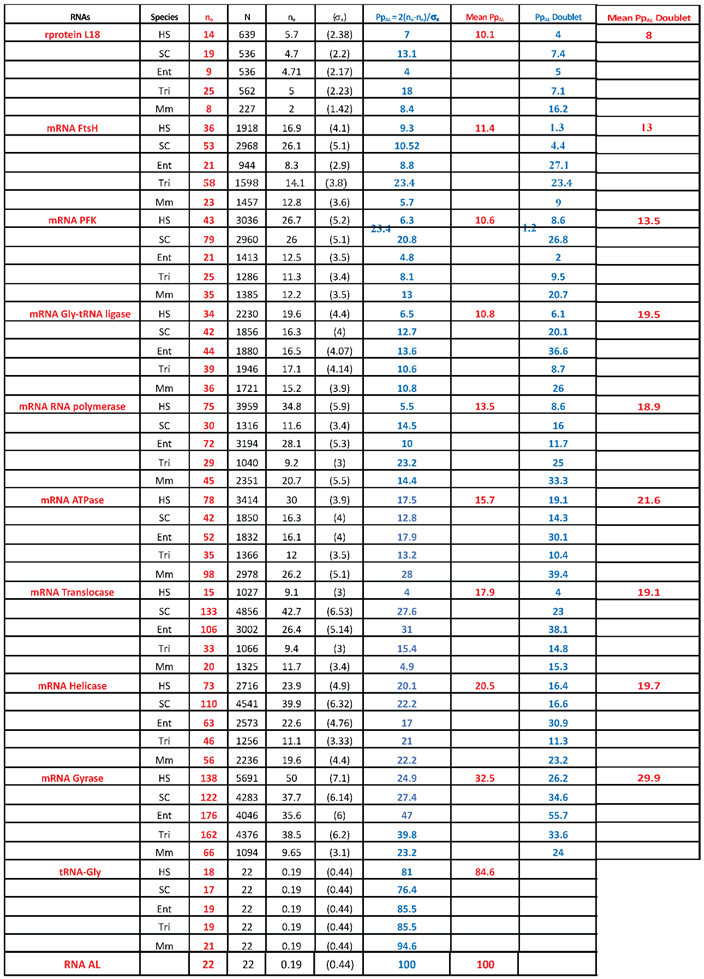

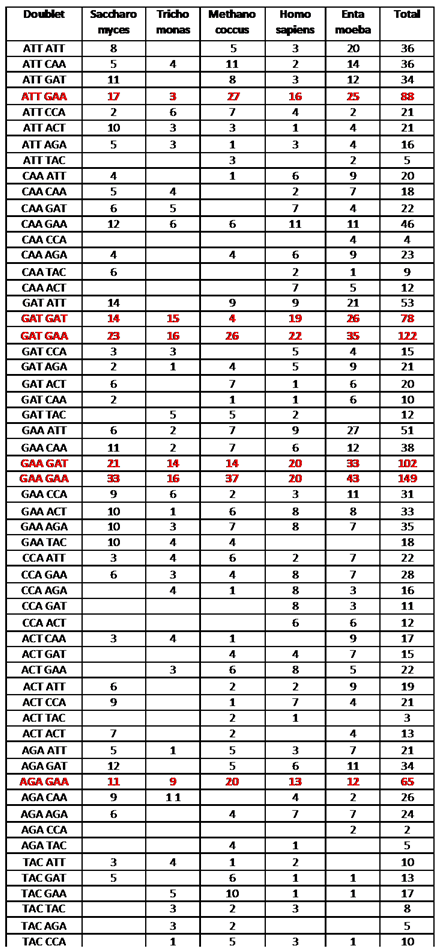

2.4. AL-Codon-Counter, an Algorithm for Finding AL Traces in Current Genomes

3. Results

3.1. Biological Properties

3.2. Functional properties of AL

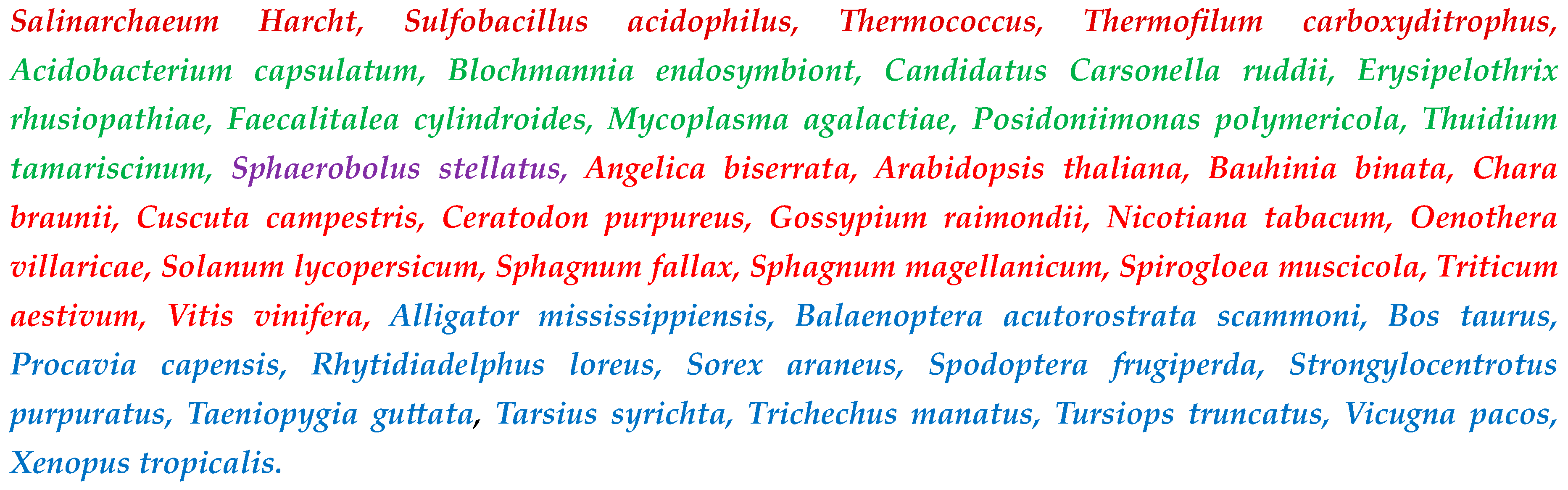

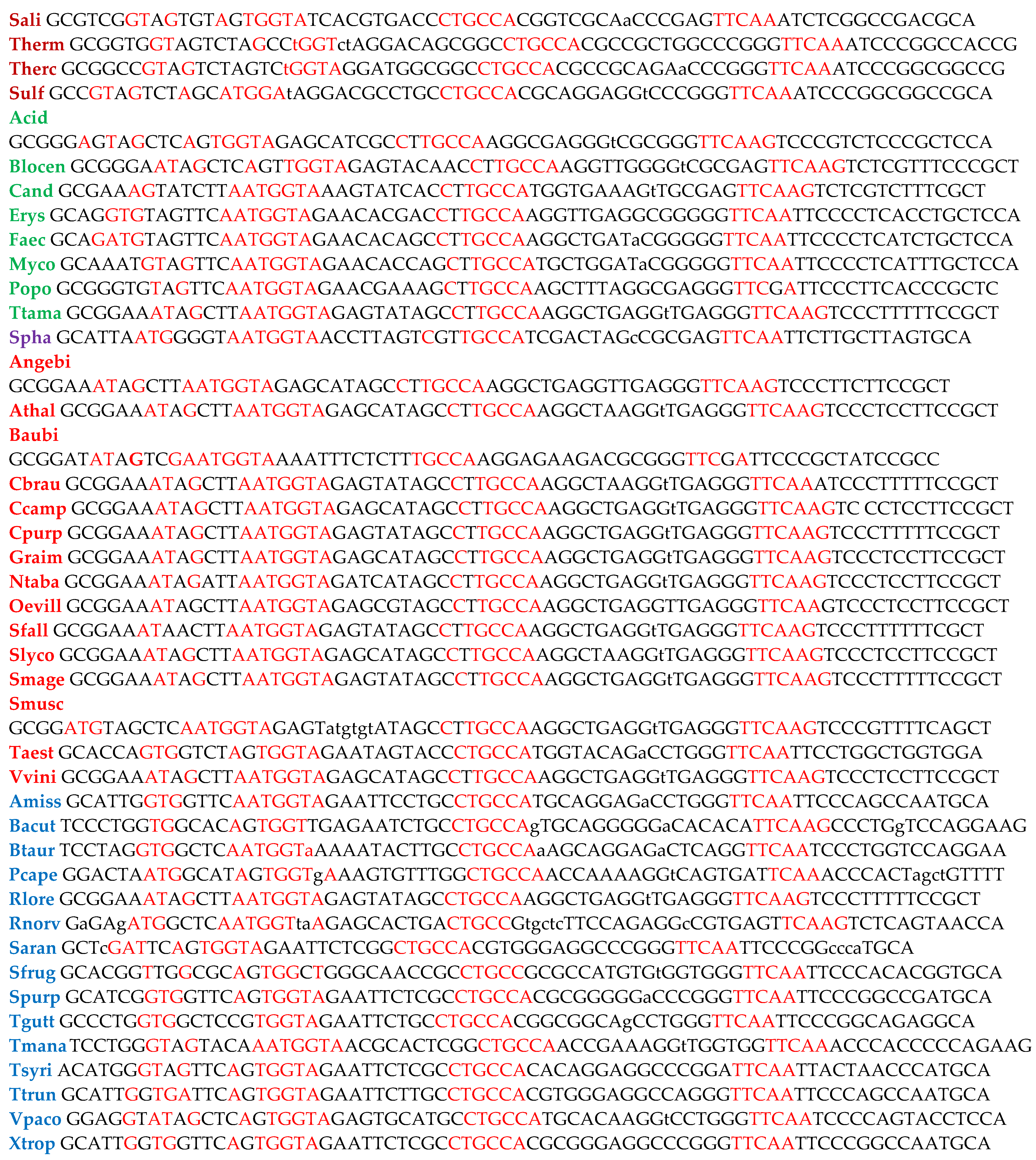

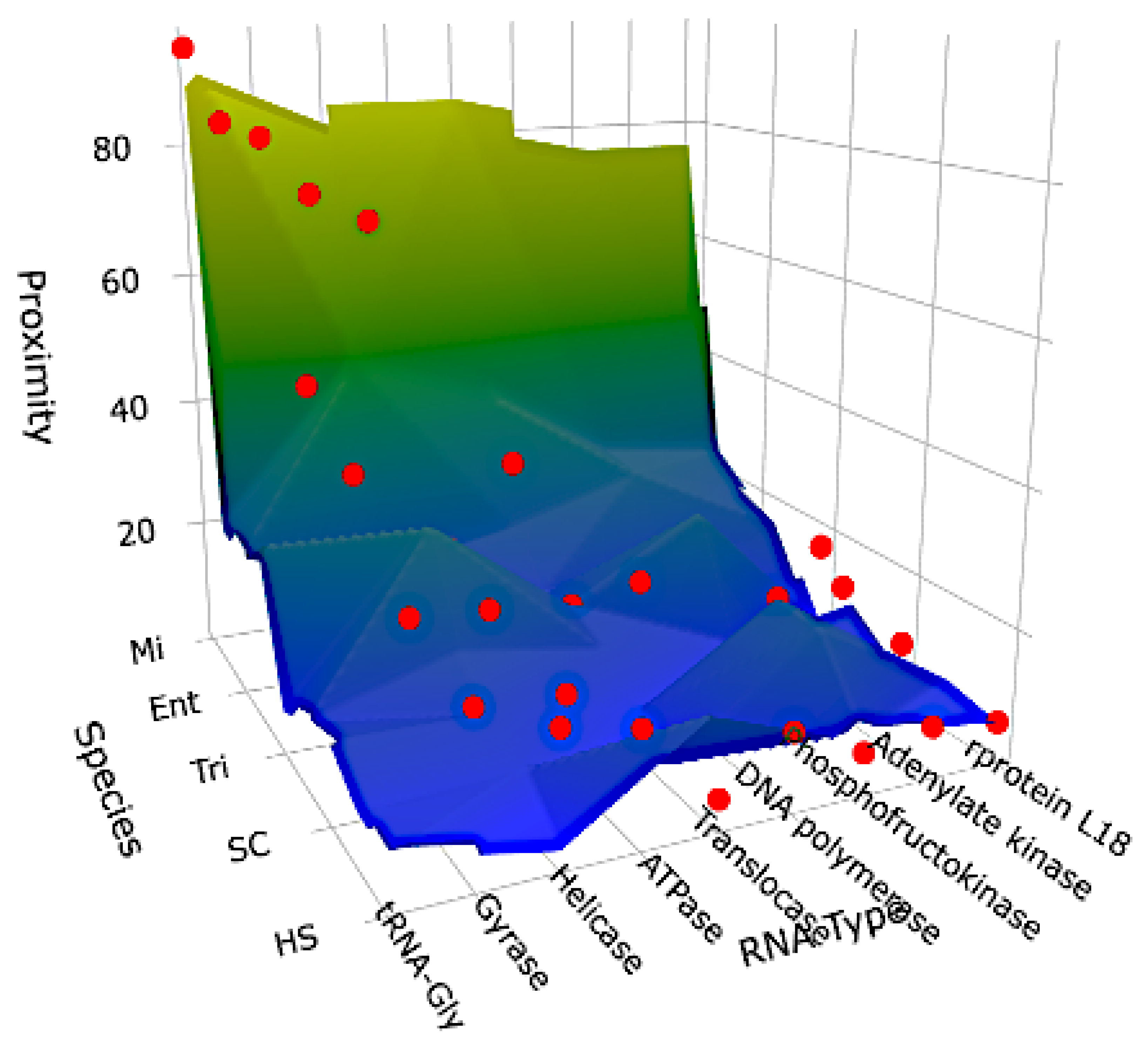

3.3. Searching for AL Motifs in Current Genomes

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paecht-Horowitz, M.; Berger, J.; Katchalsky, A. Prebiotic Synthesis of Polypeptides by Heterogeneous Polycondensation of Amino-acid Adenylates. Nature 1970, 228, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paecht-Horowitz, M.; Katchalsky, A. Synthesis of amino acyl-adenylates under prebiotic conditions. J. Mol. Evol. 1973, 2, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brack, A. Polymerisation en phase aqueuse d’acides aminés sur des argiles. Clay Minerals 1976, 11, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, F. H. C. , Brenner, S., Klug, A. & Pieczenik, G. A speculation on the origin of protein synthesis. Orig. Life, 1976, 7, 389–397. [Google Scholar]

- Noller, H. F. Evolution of protein synthesis from an RNA world. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a003681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jash, B.; Tremmel, P.; Jovanovic, D.; Richert, C. Single nucleotide translation without ribosomes. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T. Simulation of the emergence of cell-like morphologies with evolutionary potential based on virtual molecular interactions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigen, M.; Schuster, P. The hypercycle: A principle of natural self-organization. Part C: The realistic hypercycle. Naturwissenschaften 1978, 65, 341–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigen, M.; Winkler-Oswatitsch, R. Transfer-RNA: The early adaptor. Naturwissenschaften 1981, 68, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, D. The Physical Basis of Life; RoutIedge and Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S.L. A Production of Amino Acids Under Possible Primitive Earth Conditions. Science 1953, 117, 528–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, E.T.; Cleaves, H.J.; Dworkin, J.P.; Glavin, D.P.; Callahan, M.; Aubrey, A.; Lazcano, A.; Bada, J.L. Primordial synthesis of amines and amino acids in a 1958 Miller H2S-rich spark discharge experiment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 5526–5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oró, J.; Kimball, A.P. Synthesis of purines under possible primitive earth conditions. I. Adenine from hydrogen cyanide. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1961, 94, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferus, M.; Pietrucci, F.; Saitta, A.M.; Knížek, A.; Kubelík, P.; Ivanek, O.; Shestivska, V.; Civiš, S. Formation of nucleobases in a Miller–Urey reducing atmosphere. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 4306–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnamperuma, C.; Sagan, C.; Mariner, R. Synthesis of adenosine triphosphate under possible primitive earth conditions. Nature 1963, 199, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobish, M.K.; Wickramasinghe, N.S.; Ponnamperuma, C. Direct interaction between amino acids and nucleotides as a possible physicochemical basis for the origin of the genetic code. Adv. Space Res. 1995, 15, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caetano-Anolles, G.; Kim, K.M. The Origin and Evolution of the Archaeal Domain. Hindawi Publishing Corporation: London, 2014.

- Di Giulio, M. On the origin of protein synthesis: A speculative model based on hairpin RNA structures. J. Theor. Biol. 1994, 171, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woese, C.R. A New Biology for a New Century. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004, 68, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, R. Small Molecule Interactions were Central to the Origin of Life. Q. Rev. Biol. 2006, 81, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, H.S. The RNA world hypothesis: The worst theory of the early evolution of life (except for all the others). Biol. Direct 2012, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colín-García, M. Hydrothermal vents and prebiotic chemistry: a review. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana 2016, 68, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarus, M. Life from an RNA world: the ancestor within. Harvard University Press: Cambridge Mass., 2010.

- Yarus, M. Eighty routes to a ribonucleotide world; dispersion and stringency in the decisive selection. RNA 2018, 24, 1041–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarus, M. On an RNA-membrane protogenome. ArXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.00647. [Google Scholar]

- Lancet, D.; Zidovetzki, R.; Markovitch, O. Systems protobiology: Origin of life in lipid catalytic networks. J. R. Soc. Interface 2018, 15, 20180159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, D.J.; Norris, V. Lipid domain boundaries as prebiotic catalysts of peptide bond formation. J. Theor. Biol. 2007, 246, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahana, A.; Lancet, D. Protobiotic Systems Chemistry Analyzed by Molecular Dynamics. Life 2019, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caforio, A.; Driessen, A.J.M. Archaeal phospho-lipids: Structural properties and biosynthesis. BBA-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2016, 1862, 1325–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J. Au sujet de quelques modèles stochastiques appliqués à la biologie. PhD thesis, Université Joseph Fourier: Grenoble, 1975 (https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00286222).

- Demongeot, J. Sur la possibilité de considérer le code génétique comme un code à enchaînement. Revue de Biomaths 1978, 62, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Demongeot, J.; Besson, J. Code génétique et codes à enchaînement I. C.R. Acad. Sc. III 1983, 296, 807–810. [Google Scholar]

- Demongeot, J.; Besson, J. Genetic code and cyclic codes II. C.R. Acad. Sc. III 1996, 319, 520–528. [Google Scholar]

- Weil, G.; Heus, K.; Faraut, T.; Demongeot, J. An archetypal basic code for the primitive genome. Theoret. Comp. Sc. 2004, 322, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Elena, A.; Weil, G. Potential-Hamiltonian decomposition of cellular automata. Application to degeneracy of genetic code and cyclic codes III. C. R. Acad. Sc. Biologies 2006, 329, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demongeot, J. Primitive genome and RNA relics. In: EMBC’ 07. IEEE Proceedings: Piscataway, 6338-42, 2007.

- Demongeot, J.; Moreira, A. A circular RNA at the origin of life. J. Theor. Biol. 2007, 249, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Drouet, E.; Moreira, A.; Rechoum, Y.; Sené, S. Micro-RNAs: viral genome and robustness of the genes expression in host. Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. A. 2009, 367, 4941–4965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Glade, N.; Moreira, A.; Vial, L. RNA relics and origin of life. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 3420–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Hazgui, H.; Bandiera, S.; Cohen, O.; Henrion-Caude, A. MitomiRs, ChloromiRs and general modelling of the microRNA inhibition. Acta Biotheoretica 2013, 61, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J. “Protoribosome” as new game of life. BioRxiv 2017. [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Hazgui, H. The Poitiers school of mathematical and theoretical biology: Besson-Gavaudan- Schützenberger’s conjectures on genetic code and RNA structures. Acta Biotheoretica 2016, 64, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demongeot, J.; Norris, V. Emergence of a “Cyclosome” in a Primitive Network Capable of Building “Infinite” Proteins. Life (Basel) 2019, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. Theoretical minimal RNA rings recapitulate the order of the genetic code’s codon-amino acid assignments. J. Theor. Biol. 2019, 471, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. Spontaneous evolution of circular codes in theoretical minimal RNA rings. Gene 2019, 705, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. More pieces of ancient than recent theoretical minimal proto-tRNA-like RNA rings in genes coding for tRNA synthetases. J. Mol. Evol. 2019, 87, 152–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. Bias for 3′-dominant codon directional asymmetry in theoretical minimal RNA rings. J. Comput. Biol. 2019, 26, 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. Theoretical minimal RNA rings designed according to coding constraints mimick deamination gradients. Sci. Nat./Nat. 2019, 106, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. Pentamers with non-redundant frames: Bias for natural circular code codons. J. Mol. Evol. 2020, 88, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. The primordial tRNA acceptor stem code from theoretical minimal RNA ring clusters. BMC Genet. 2020, 21, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. Accretion history of large ribosomal subunits deduced from theoretical minimal RNA rings is congruent with histories derived from phylogenetic and structural methods. Gene 2020, 738, 144436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. Deamination gradients within codons after 1<->2 position swap predict amino acid hydrophobicity and parallel β-sheet conformational preference. Biosystems 2020, 192, 104116. [Google Scholar]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. Theoretical minimal RNA rings maximizing coding information overwhelmingly start with the universal initiation codon AUG. BioEssays 2020, 42, 1900201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Henrion-Caude, A. The old and the new on the prebiotic conditions of the origin of life. Biology (Basel) 2020, 9, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. Theoretical minimal RNA rings mimick molecular evolution before tRNA-mediated translation: codon-amino acid affinities increase from early to late RNA rings. C. R. Acad. Sci. Biologies 2020, 343, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. Evolution of tRNA subelement accretion from small and large ribosomal RNAs. Biosystems 2022, 193, 104796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, V.; Demongeot, J. The Ring World hypothesis: the eversion of small, double-stranded polynucleotide circlets was at the origin of the double helix of DNA, the polymerisation of RNA and DNA, the triplet code, the twenty or so biological amino acids, and strand asymmetry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Thellier, M. Primitive oligomeric RNAs at the origins of life on Earth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Waku, J.; Cohen, O. Combinatorial and frequency properties of the ribosome ancestors. AIMS MBE 2023, 21, 884–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Khalfallah, H.; Jelassi, M.; Rissaoui, H.; Barchouchi, M.; Baraille, C.; Gardes, J.; Demongeot, J. Information Gradient among Nucleotide Sequences of Essential RNAs from an Evolutionary Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Khalfallah, H.; Jelassi, M.; Rachdi, M.; Demongeot, J. The AL-Codon-Counter Program: An Advanced Tool for Pentamer Analysis in RNA Sequences and Evolutionary Insights. In: SAI Computing Conference 2025, Lecture Notes in Networks & Systems, Springer Nature, New York (2025).

- Staley, J.T. Domain Cell Theory supports the independent evolution of the Eukarya, Bacteria and Archaea and the Nuclear Compartment Commonality hypothesis. Open Biol. 2017, 7, 170041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, J. System analysis of synonymous codon usage biases in archaeal virus genomes. J. Theor. Biol. 2014, 355, 128–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahiri-Elitzur, S.; Tuller, T. Codon-based indices for modeling gene expression and transcript evolution. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 2646–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GtRNAdb. Available online: http://gtrnadb.ucsc.edu/ (accessed on 22/02/2025).

- NCBI Nucleotide. Available on line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide (accessed on 22/02/2025).

- MiRBase. Available online: http://www.mirbase.org/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Georg, R.C.; Stefani, R.M.; Gomes, S.L. Environmental stresses inhibit splicing in the aquatic fungus Blastocladiella emersonii. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogozin, I.B.; Carmel, L.; Csuros, M.; Koonin, E.V. Origin and evolution of spliceosomal introns. Biol. Direct. 2012, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochier-Armanet, C.; Forterre, P.; Gribaldo, S. Phylogeny and evolution of the Archaea: One hundred genomes later. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011, 14, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forterre, P. The Common Ancestor of Archaea and Eukarya Was Not an Archaeon. Archaea 2013, 2013, 372396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staley, J.T. Domain Cell Theory supports the independent evolution of the Eukarya, Bacteria and Archaea and the Nuclear Compartment Commonality hypothesis. Open Biol. 2017, 7, 170041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slonimski, P.P. Periodic oscillations of the genomic nucleotide sequences disclose major differences in the way of constructing homologous proteins from different procaryotic species. Comptes Rendus Biologies 2007, 330, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarus, M. The meaning of a minuscule ribozyme. Phil. Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011, 366, 2902–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Schimmel, P. Oligonucleotide-directed peptide synthesis in a ribosome- and ribozyme-free system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 1393–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Schimmel, P. Peptide synthesis with a template-like RNA guide and aminoacyl phosphate adaptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8666–8669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Schimmel, P. Chiral-selective aminoacylation of an RNA minihelix. Science 2004, 305, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Schimmel, P. Chiral-selective aminoacylation of an RNA minihelix: Mechanistic features and chiral suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 13750–13752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Kim, H.K.; Lee, S.; Seo, J.H; Choi, J.W.; Park, J.; Min, S.; Yoon, S.; Cho, S.; Kim, H.H. Prediction of the sequence-specific cleavage activity of Cas9 variants. Nature Biotechnology 2020, 38, 1328–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.M.; Wang, T.; Randolph, P.B.; Arbab, M.; Shen, M.W.; Huang, T.P.; Matuszek, Z.; Newby, G.A.; Rees, H.A.; Liu, D.R. Continuous evolution of SpCas9 variants compatible with non-G PAMs. Nature Biotechnology 2020, 38, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.; Brinkmann, H.; Pradella, S. Diversity and evolution of repABC type plasmids in Rhodobacterales. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 11, 2627–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifonov, E.N.; Bettecken, T. Sequence fossils, triplet expansion, and reconstruction of earliest codons. Gene 1997, 205, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifonov, E.N. Consensus temporal order of amino acids and evolution of the triplet code. Gene 2000, 261, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolevsky, Y.; Guimarães, R.C.; Trifonov, E.N. Towards functional repertoire of the earliest proteins. J. Biomol. Structure and Dynamics 2013, 31, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontecilla-Camps, J. Geochemical Continuity and Catalyst/Cofactor Replacement in the Emergence and Evolution of Life. Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 08438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, J.; Catalan, P.; Cuesta, J.A.; Manrubia, S. On the networked architecture of genotype spaces and its critical effects on molecular evolution. Open Biol. 2018, 8, 180069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligmann, H.; Raoult, D. Stem-Loop RNA Hairpins in Giant Viruses: Invading rRNA-Like Repeats and a Template Free RNA. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, H.J. The gene as the basis of life. In Proceedings of the International Congress of Plant Sciences Ithaca 1926; Duggar, B.M., Ed.; Menasha: Banta, Wsconsin, 1929; pp. 897–921. [Google Scholar]

- Eigen, M. Selforganization of matter and the evolution of biological macromolecules. Naturwissenschaften 1971, 58, 465–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturana, H.R.; Varela, F.J. Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living; Reidel: Boston, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgine, P.; Stewart, J. Autopoiesis and cognition. Artif. Life 2004, 10, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, N.; Ikegami, T. Self-maintenance and self-reproduction in an abstract cell model. J. Theor. Biol. 2000, 206, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, N.; Ikegami, T. Artificial chemistry: Computational studies on the emergence of self-reproducing units. In Proceedings of the 6th European conference on artificial life (ECAL’01), Prague, Czech Republic, September 2001; Kelemen, J., Sosik, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2001; pp. 186–195. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, D. Genes are not the blueprint for life. Nature 2019, 626, 254–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, D.; Joyner, M. The physiology of evolution. J. Physiol. 2024, 602, 2361–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufton, M.J. Genetic code synonym quotas and amino acid complexity: Cutting the cost of proteins? J. Theor. Biol. 1997, 187, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.K. Evolution of the genetic code. Prog. Biophy. Mol. Biol. 1999, 72, 157–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.T.F. Coevolution theory of the genetic code at age thirty. Bioessays 2005, 27, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.T.F.; Ng, S.K.; Mat, W.K.; Hu, T.; Xue, H. Coevolution theory of the genetic code at age forty: Pathway to translation and synthetic life. Life (Basel) 2016, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, N.; Kaneko, K. The origin of the central dogma through conflicting multilevel selection. Proc. R. Soc. B 2019, 286, 20191359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, S.D.; Fujishima, K.; Makarov, M.; Cherepashuk, I.; Hlouchova, K. Peptides before and during the nucleotide world: an origins story emphasizing cooperation between proteins and nucleic acids. J. R. Soc. Interface 2022, 19, 20210641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Wang, S.K.; Belk, J.A.; Amaya, L.; Li, Z.; Cardenas, A.; Abe, B.T.; Chen, C.K.; Wender, P.A.; Chang, H.Y. Engineering circular RNA for enhanced protein production. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, N.; Schabanel, N. ENSnano: A 3D Modeling Software for DNA Nanostructures. DNA 2021, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Michaud, M.; Cognat, V.; Duchêne, A.M.; Maréchal-Drouard, L. A global picture of tRNA genes in plant genomes. Plant J. 2011, 66, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonville, N.C.; Velmurugan, K.R.; Tae, H.; Vaksman, Z.; McIver, L.J.; Garner, H.R. Genomic leftovers: Identifying novel microsatellites, over-represented motifs and functional elements in the human genome. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, K.; Sugahara, J.; Tomita, M.; Kanai, A. Sequence Evidence in the Archaeal Genomes that tRNAs Emerged Through the Combination of Ancestral Genes as 59 and 39 tRNA Halves. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spang, A.; Caceres, E.F.; Ettema, T.J.G. Genomic exploration of the diversity, ecology, and evolution of the archaeal domain of life. Science 2017, 357, eaaf3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eme, L.; Spang, A.; Lombard, J.; Stairs, C.W.; Ettema, T.J.G. Archaea and the origin of eukaryotes. Nature 2017, 15, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, M.; Fabre, E.; Poirot, O.; Jeudy, S.; Lartigue, A.; Alempic, J.M.; Beucher, L.; Philippe, N.; Bertaux, L.; Christo-Foroux, E.; Labadie, K.; Couté, Y.; Abergel, C.; Claverie, J.M. Diversity and evolution of the emerging Pandoraviridae family. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, R.J.; Boucher, Y.; Dahllöf, I.; Holmström, C.; Doolittle, W.F.; Kjelleberg, S. Use of 16S rRNA and rpoB Genes as Molecular Markers for Microbial Ecology Studies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 73, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartnik, E.; Borsuk, P. A glycine tRNA gene from lupine mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986, 14, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüter, K.; Fütterer, J.; Potrykus, I. Horizontal Gene Transfer from a Transgenic Potato Line to a Bacterial Pathogen (Erwinia chrysanthemi) Occurs-if at All-at an Extremely Low Frequency. Biotechnology 1995, 13, 1094–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E.A.; Seitzer, P.M.; Tritt, A.; Larsen, D.; Krusor, M.; Yao, A.I.; Wu, D.; Madern, D.; Eisen, J.A.; Darling, A.E.; et al. Phylogenetically Driven Sequencing of Extremely Halophilic Archaea Reveals Strategies for Static and Dynamic Osmo-response. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahão, J.; Silva, L.; Silva, L.S.; Khalil, J.Y.B.; Rodrigues, R.; Arantes, T.; Assis, F.; Boratto, P.; Andrade, M.; Kroon, E.G.; et al. Tailed giant Tupanvirus possesses the most complete translational apparatus of the known virosphere. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzayan, J.M.; Hampel, A.; Bruening, G. Nucleotide sequence and newly formed phosphodiester bond of spontaneously ligated satellite tobacco ringspot virus RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986, 14, 9729–9743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, J.; Krucinska, J.; Alam, S.; Grum-Tokars, V.; Wedekind, J.E. Water in the Active Site of an All-RNA Hairpin Ribozyme and Effects of Gua8 Base Variants on the Geometry of Phosphoryl Transfer. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Ruiz, M.; Barroso-delJesus, A.; Berzal-Herranz, A. Specificity of the Hairpin Ribozyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 29376–29380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, U.F. Design and Experimental Evolution of trans-Splicing Group I Intron Ribozymes. Molecules 2017, 22, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, N.; Joyce, G.F. A self-replicating ligase ribozyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 12733–12740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, J.; Weinberg, Z.; Roth, A.; Popescu, O.; Chartrand, P.; Ferbeyre, G.; Breaker, R.R. Identification of Hammerhead Ribozymes in All Domains of Life Reveals Novel Structural Variations. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011, 7, e1002031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammann, C.; Luptak, A.; Perreault, J.; De La Peña, M. The ubiquitous hammerhead ribozyme. RNA 2012, 18, 871–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.A.; Lünse, C.E.; Li, S.; Brewer, K.I.; Breaker, R.R. Biochemical analysis of hatchet self-cleaving ribozymes. RNA 2015, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agmon, I.C. Could a Proto-Ribosome Emerge Spontaneously in the PrebioticWorld? Molecules 2016, 21, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arquès, D.G.; Michel, C.J. A complementary circular code in the protein coding genes. J. Theor. Biol. 1996, 182, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dila, G.; Ripp, R.; Mayer, C.; Poch, O.; Michel, C.J.; Thompson, J.D. Circular code motifs in the ribosome: A missing link in the evolution of translation? RNA 2019, 25, 1714–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Opron, K.; Burton, Z.F. A tRNA- and Anticodon-Centric View of the Evolution of Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases, tRNAomes, and the Genetic Code. Life (Basel) 2019, 9, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Kunnev, D.; Gospodinov, A. Possible Emergence of Sequence Specific RNA Aminoacylation via Peptide Intermediary to Initiate Darwinian Evolution and Code Through Origin of Life. Life (Basel) 2018, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligmann, H. Protein Sequences Recapitulate Genetic Code Evolution. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2018, 16, 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Zaia, D.A.; Zaia, C.T.; De Santana, H. Which amino acids should be used in prebiotic chemistry studies? Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 2008, 38, 469–488. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, R. Jump-starting a cellular world: Investigating the origin of life, from soup to networks. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, e396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beringer, M.; Rodnina, M.V. Importance of tRNA interactions with 23S rRNA for peptide bond formation on the ribosome: Studies with substrate analogs. Biol. Chem. 2007, 388, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Novozhilov, A.S. Origin and evolution of the genetic code: The universal enigma. Iubmb Life 2009, 61, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodin, A.S.; Szathmáry, E.; Rodin, S.N. On origin of genetic code and tRNA before translation. Biol. Direct. 2011, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koonin, E.V. Frozen Accident Pushing 50: Stereochemistry, Expansion, and Chance in the Evolution of the Genetic Code. Life (Basel) 2017, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, D.L.; Giannerini, S.; Rosa, R. On the origin of degeneracy in the genetic code. Interface Focus 2019, 9, 20190038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).