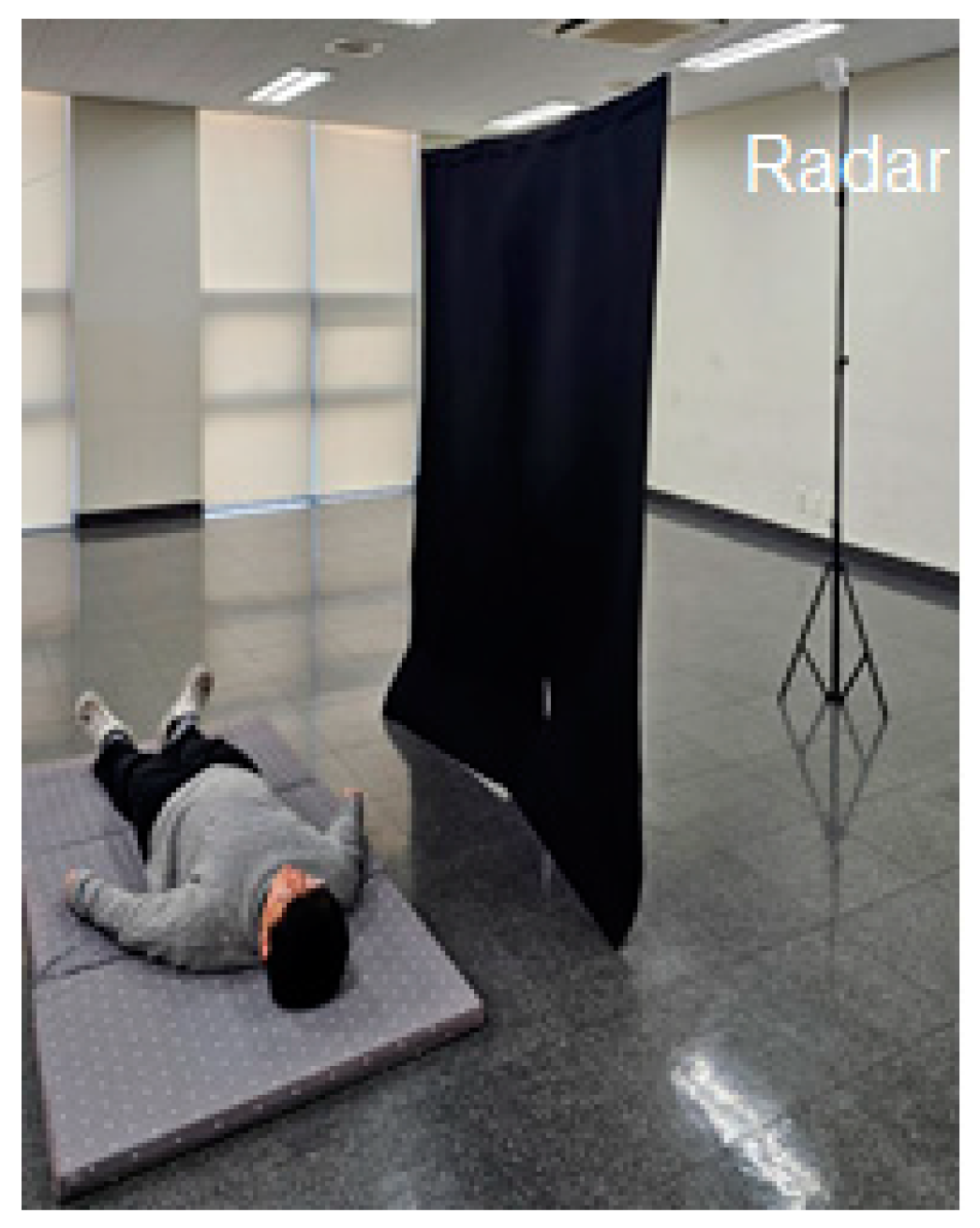

2.1. Experimental Setup

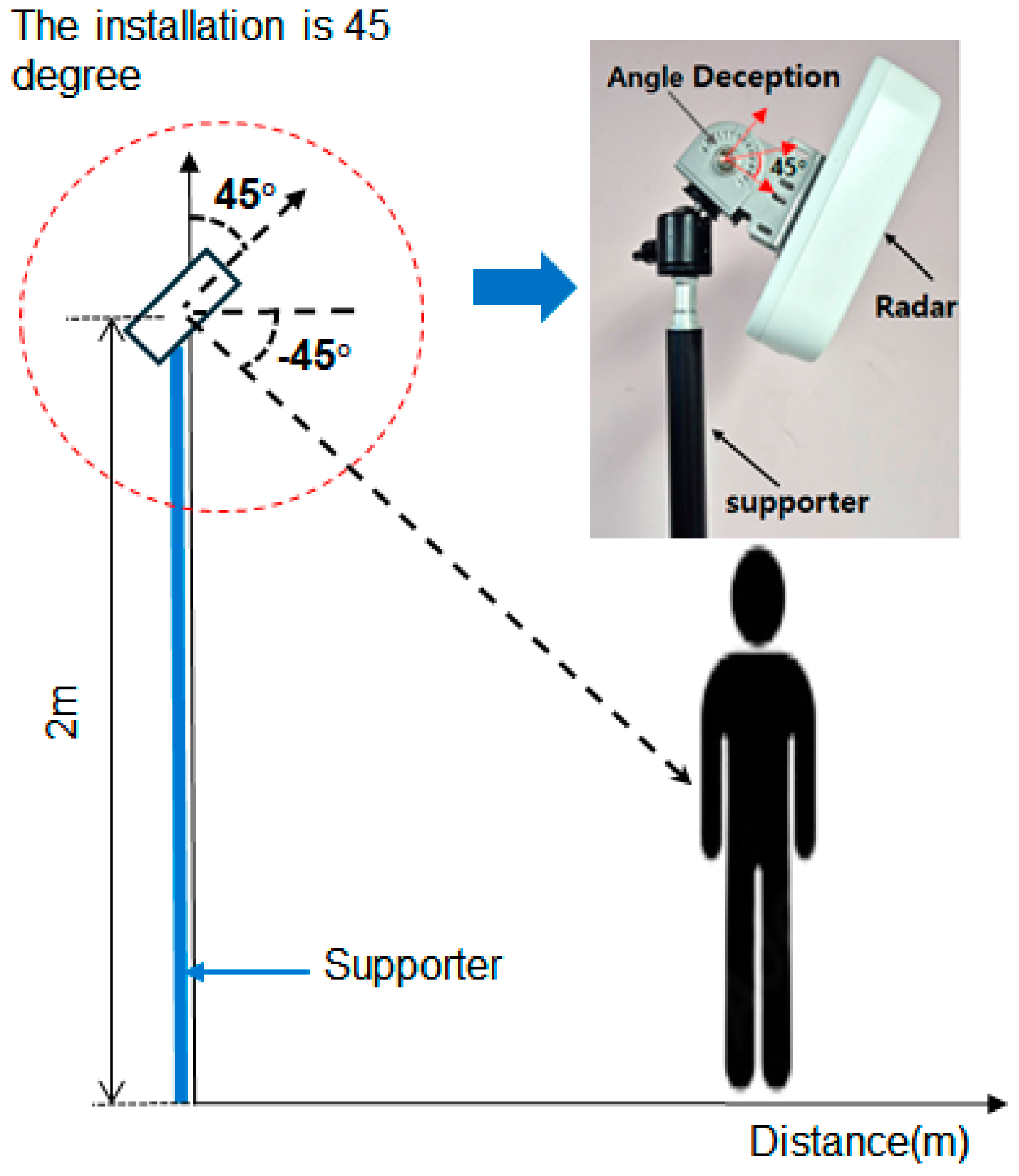

In this study, we utilized the Retina-4sn radar from Smart Radar System, operating within a frequency range of 77–81 GHz. This sensor provides high-resolution 4D imaging and measures the position, velocity, size, and height of the target. The radar was installed at a height of 2 meters to optimize signal reception and minimize interference, with the experimental setup designed to cover a detection range of 7m × 7m. The azimuth and elevation angles were configured at 90° (±45°) to enable objects’ contours to be monitored across a wide range of angles both vertically and horizontally. With a rapid data update rate of 50ms, the radar is capable of processing multiple frames per second, ensuring real-time responsiveness in dynamic environments. The experimental environment was optimized to collect diverse posture data, considering installation height, direction, and tilt for stable measurements.

The 4D imaging radar generates Point Cloud data by detecting and analyzing object movements, and representing them as points in three-dimensional virtual space. These data visually express the location and shape of objects, which enhances the analytical efficiency and supports precise spatial interpretation.

A systematic data collection environment for Point Cloud data was designed to develop an AI model for human posture classification. The experimental setup emphasized optimizing the installation height, direction, tilt, and measurement space to reflect real-world application conditions.

As shown in

Figure 1, the radar was installed at the manufacturer-recommended height of 2 meters to optimize the signal reception angle and minimize interference from obstacles. The radar was aligned frontally to precisely measure the target's movement and reduce interference. Additionally, the tilt was set at −45° to ensure that the target was positioned at the center of the radar detection range. This facilitated reliable data acquisition for movements at ground level such as lying postures. This configuration enabled the stable collection of various postural changes, thereby maximizing the efficiency and performance of AI model training. These settings align with the optimal tilt angle range (30°–60°) reported in previous studies, further reinforcing the reliability of the experimental design [

15].

2.2. Point Cloud Data Collection

In this study, Point Cloud data, representing a three-dimensional virtual space for detecting and analyzing object movements, were collected within a range of 3m on both sides and 7m forward to capture diverse postures. To optimize data quality, the environment was configured without obstacles to accurately capture target movements and minimize interference from external factors.

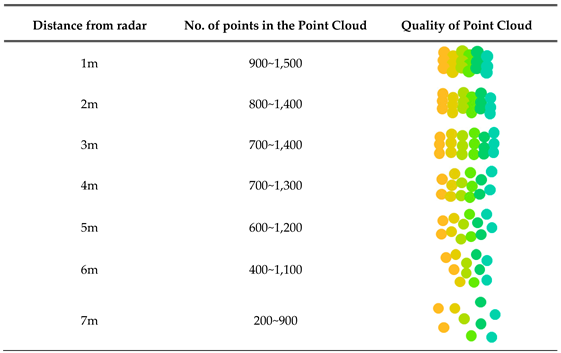

The experimental results showed that data stability decreased beyond a range of 2.5m on either side. The detection distance was increased incrementally from 1m to 7m in intervals of 1m, and the number and density of points in the Point Cloud data were quantified. The characteristics identified from the experimental results presented in

Table 1 are as follows.

Within the 1–3m range, 700–1500 points were detected per frame and this was sufficient to maintain uniform data distribution and high density. In particular, the 2–3m range exhibited the highest precision and stability, making it the optimal distance for capturing detailed movements such as posture classification. Unfortunately, at a distance of 1m, despite the high number and density of points, lower-body data were frequently lost. In the 4–5m range, point intervals became irregular, and the density gradually decreased, whereas, beyond 6m, the data quality sharply declined.

These experimental results clearly demonstrate that the distance between the target and the radar directly impacts the quality and reliability of the Point Cloud data. Therefore, setting an appropriate detection range is essential for collecting reliable data.

The data collected in this study provided a stable foundation for securing high-quality training datasets, which were used to maximize the performance of the AI model.

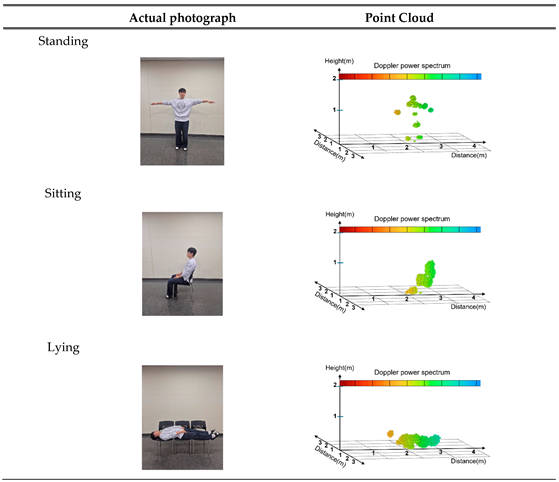

In this study, posture data were classified into three categories: standing, sitting, and lying down, as presented in

Table 2, when using the Point Cloud for AI training. Point Cloud data for the three categories were collected from the front, back, right, and left directions to minimize potential body occlusion effects. Irregular or unclear movements were included in the unknown category to maintain data quality and improve the accuracy of the model. Irregular or unclear movements were included in the unknown category to maintain data quality and improve the accuracy of the model.

The standing posture included both standing still and walking movements, with static and dynamic movement data collected. The sitting posture was based on the state of sitting on a chair and included not only stable postures but also subtle movements. The lying down posture was based on the state of lying down on a chair, with data collection including the process of lying down slowly. This can be used to distinguish between abrupt falls and natural lying motions.

The radar system processed data at 30 frames per second, and approximately 1,500 frames were collected for each posture by capturing data for 50 seconds per posture. Data integrity was maintained by classifying ambiguous postures into the unknown category. This approach to dataset construction was designed to precisely classify posture data by minimizing false positives and missed detections. Data were captured in various environments and under various conditions to ensure that the AI model maintains high reliability and accuracy in real-world applications. This is expected to enhance the effectiveness of radar-based posture analysis systems and contribute to their applicability in practical use cases.

2.3. Point Cloud Data Preprocessing

Successful training of the AI model requires the Point Cloud data collected from the radar sensors to be systematically preprocessed. Point Cloud data contain high-dimensional and complex information, including information about the position, velocity, time, and Doppler power. Using these raw data as direct input into AI models can lead to issues such as overfitting or reduced learning efficiency. Therefore, preprocessing is necessary to remove noise, extract the key information required by the learning model, and optimize the performance and stability.

In this study, preprocessing focused on spatial position information directly related to posture classification within the Point Cloud data. This approach removed unnecessary information to enhance the data processing speed, ensure real-time performance, and improve the processing efficiency of the model. Simplifying the data lowers the computational cost and model complexity while maximizing accuracy and practicality.

The number of samples generated in Point Cloud data varies depending on the target's actions and movements. For example, rapidly moving targets generate more points, while static targets result in fewer points. This data imbalance could render the input data less consistent and would negatively affect the learning performance. To address this issue, normalization and balance adjustment processes were implemented to improve the quality of the training data to enable the model to operate more reliably across diverse behavioral patterns.

The data were collected over 50 seconds, resulting in 1,500 frames, with the number of points per frame (

N) ranging from 200 to 1,500 (

Table 1). Considering that the data used as input for deep learning models must maintain a consistent size, frames with varying lengths were normalized to

N=500. Frames with fewer than 500 points (

N≤500) were padded with zeros using the back-padding technique by filling the missing portions with the value "0" without introducing artificial values. The point (0, 0, 0) in the three-dimensional space has clearly distinguishable spatial characteristics and does not have a significant negative impact on model training, so no further post-processing is performed after zero padding.

This method maintained consistency in the input data and improved the learning efficiency. Consequently, Point Cloud data with varying lengths were transformed to ensure they were suitable for deep learning models, particularly to enhance the stability and performance during training and inference.

Frames with

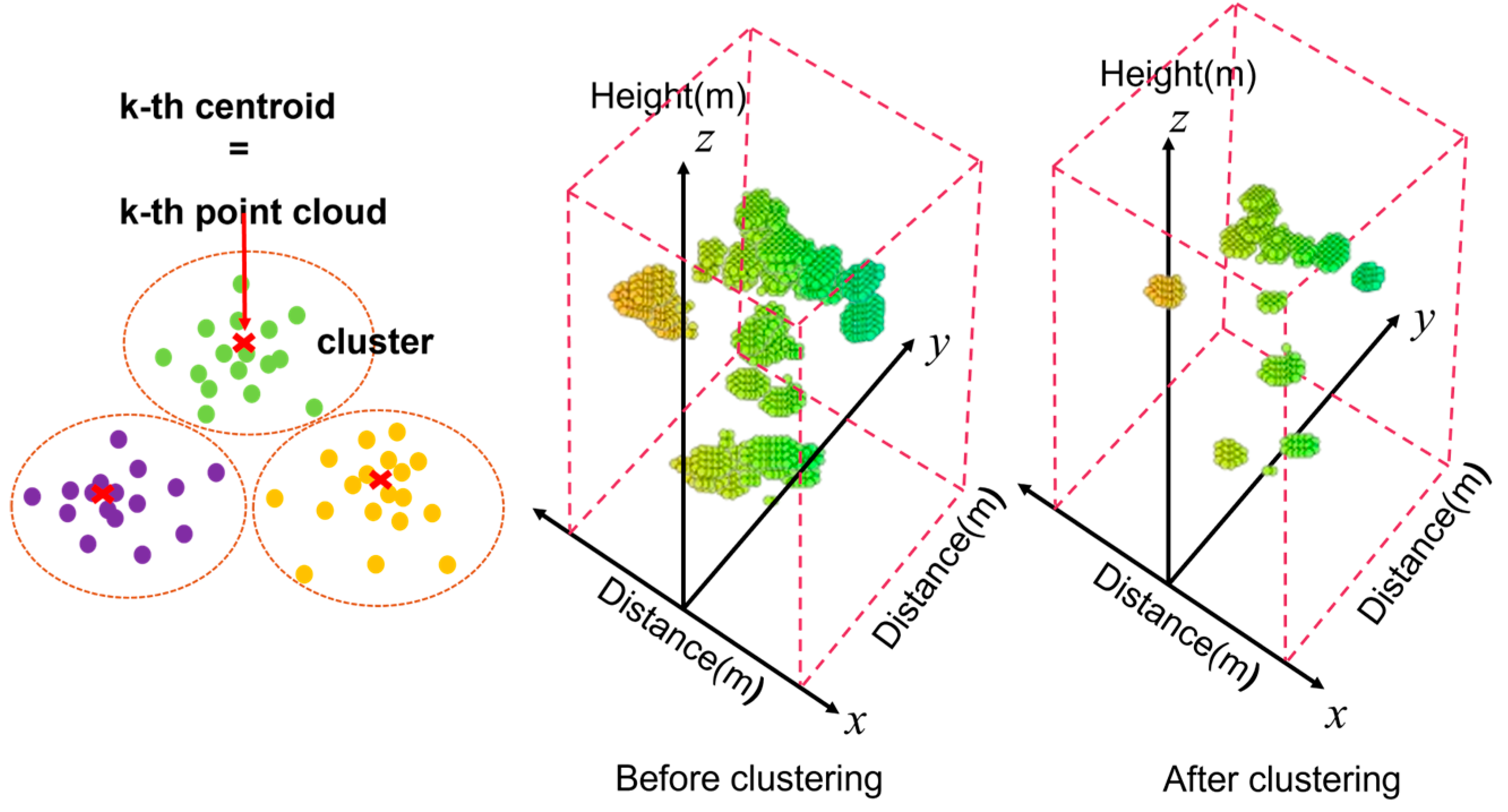

N>500 were processed using the K-means clustering algorithm, as shown in

Figure 2. The data were divided into

k=500 clusters, and new Point Cloud data were generated using the centroid of each cluster. This effectively eliminated excessive data while retaining key spatial features [

16].

As shown in

Figure 2, before the application of K-means clustering, the original Point Cloud data were irregularly distributed, and this could adversely affect the learning efficiency of AI models. However, as demonstrated in

Figure 2, the Point Cloud data (

N=500) generated after clustering effectively preserved the primary spatial features of the original data and reduced irregularity. This improvement is expected to further enhance the stability and performance of the learning model.

Radar signals may distort the data sequence during the collection process due to factors such as the time required for the signal to complete a round-trip, movement of the target, and changes in the distance to the radar equipment. Particularly, data sequences collected from subtle body movements or rotations may appear random and could potentially degrade the performance of location-pattern learning models such as CNNs. This issue was addressed by applying a systematic data sorting method. The reconstruction of data sequences to ensure consistency enhances the ability of the learning model to efficiently learn patterns. Ultimately, this improves the model training performance and prediction accuracy. The Point Cloud data in each frame are expressed as coordinate values in 3D space, (

xi,

yi,

zi), represented as

pi=(

xi,

yi,

zi),

i=1, 2, … ,

N. To systematically sort these data, an ascending order sorting method, as shown in Equation 1, was applied to the Point Cloud data

pi [

17].

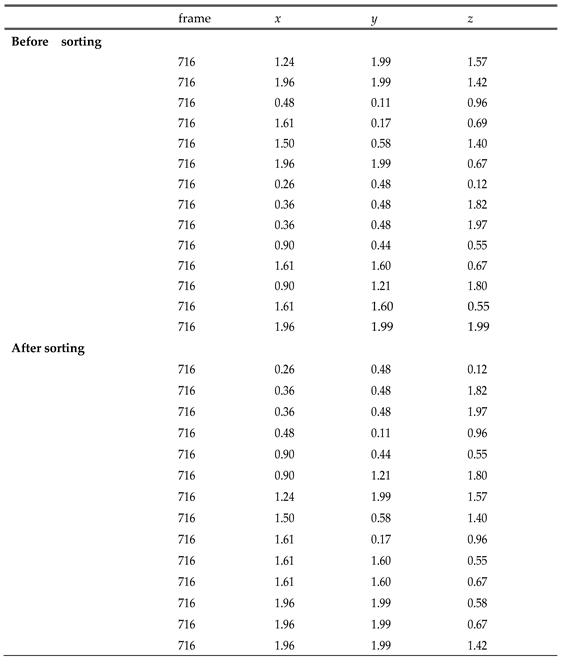

Equation 1 defines the lexicographical order between two vectors (xa, ya, za) and (xb, yb, zb). This order establishes a rule to determine whether one vector is "smaller" or "greater" than the other. If the first coordinate xa < xb, then (xa, ya, za) is considered "smaller." If xa = xb, the data are sorted based on ya < yb. Lastly, if xa = xb and ya = yb, the data are sorted based on za < zb. The sorting criteria involve sorting all points in the ascending order of their x-coordinates first. For points with identical x-coordinates, they are further sorted in ascending order of their y-coordinates. Finally, for points with identical x- and y-coordinates, sorting is conducted in the ascending order of their z-coordinates.

This sorting process is illustrated through the pre-sorted state and the post-sorted state in

Table 3. During this process, the actual distances or relative positions between the points remain unchanged, and only the order in which the data are input is rearranged.

This sorting method systematically organizes the sequence of Point Cloud data to ensure consistency in the input order for the CNN model. This allows the model to effectively learn patterns and maximize its performance.

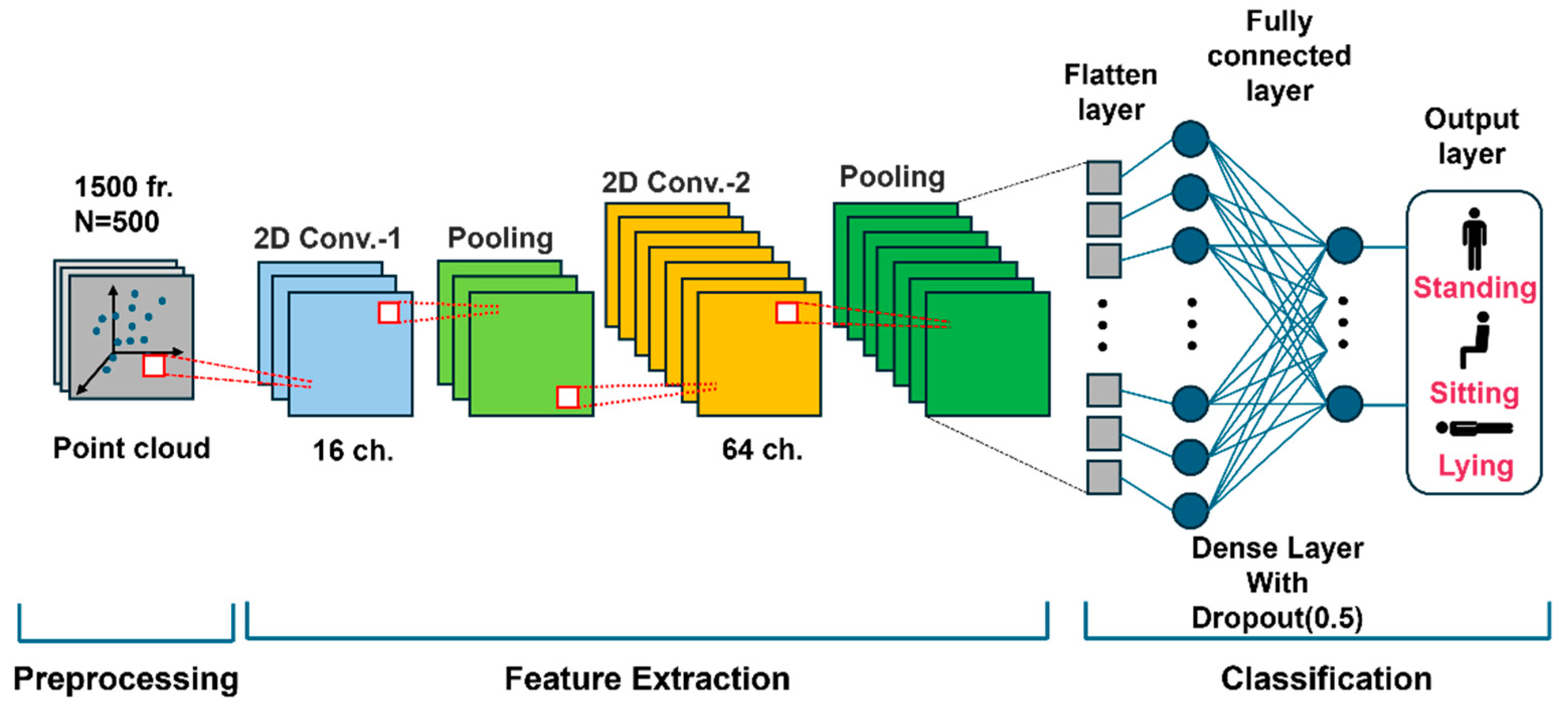

2.4. Design of the Artificial Intelligence

In this study, the CNN architecture was designed to classify three postures (Standing, Sitting, Lying) for fall detection, as illustrated in

Figure 3. This CNN architecture effectively learns the complex spatial features of Point Cloud data to achieve high classification accuracy [

14].

In the preprocessing stage, techniques such as zero padding and K-means clustering were used to normalize and balance the Point Cloud data to lower the amount of noise and establish a stable learning environment. This process transforms the input data into a form suitable for CNN training.

In the feature extraction stage, the Point Cloud data were mapped into a 2D array, followed by two stages of 2D convolution layers for progressive feature learning. The first convolution layer used 16 channels to capture basic positional and spatial features, while the second layer used 64 channels to learn more abstract and complex features. Each convolution layer employed the Leaky ReLU activation function to handle negative values effectively, and pooling layers reduced the amount of data while retaining essential information to enhance the computational efficiency.

In the classification stage, the extracted features were transformed into a 1D vector through a Flatten layer, and posture classification was performed using a fully connected layer. During this process, Dropout (0.5) was applied to randomly deactivate some neurons during training, thereby serving to lower the dependency on specific neurons and prevent overfitting. Finally, the output layer, with a Softmax activation function, provided the predicted probabilities for the three classes: Standing, Sitting, and Lying.

The data sorting and normalization techniques applied in this study eliminated randomness in Point Cloud data and maintained a consistent input structure. This contributed to securing the stability needed for the learning model to effectively learn patterns to maximize its performance.

2.5. Comparative Analysis of Fall Detection

To effectively detect falls, the establishment of clear criteria that distinguish between normal, slow-lying movements and falls is essential. During a fall, the height (zmax) of the body part farthest from the ground (the crown of the head) and the velocity change at this height are prominent features for identification. This study proposes a method for differentiating between the movements of lying down slowly and falling by analyzing and comparing the zmax values and velocity changes of zmax.

Figure 4 illustrates that during movement that involves lying down slowly (standing → lowering posture (A) → sitting (B) → leaning the upper body forward (C) → lying down), the z

max value gradually decreases over time. In the "standing → lowering posture → sitting" segment (B), z

max decreases consistently, whereas, in the "sitting → leaning the upper body forward" segment (C), an intentional posture adjustment to maintain body stability causes z

max to momentarily increase before decreasing again. This pattern indicates that the body maintains its balance in a controlled manner during the process of lying down slowly.

In contrast,

Figure 4 shows that during a fall, z

max decreases abruptly without intermediate stages and this movement is characterized by significant fluctuations. Because falls occur in an uncontrolled manner, the body rapidly approaches the ground within a short time, resulting in this characteristic pattern. The sudden, sharp changes in z

max during a fall distinctly differ from the gradual changes observed for movement when lying down normally. These differences make the z

max value an effective indicator for distinguishing between normal movements and falls.

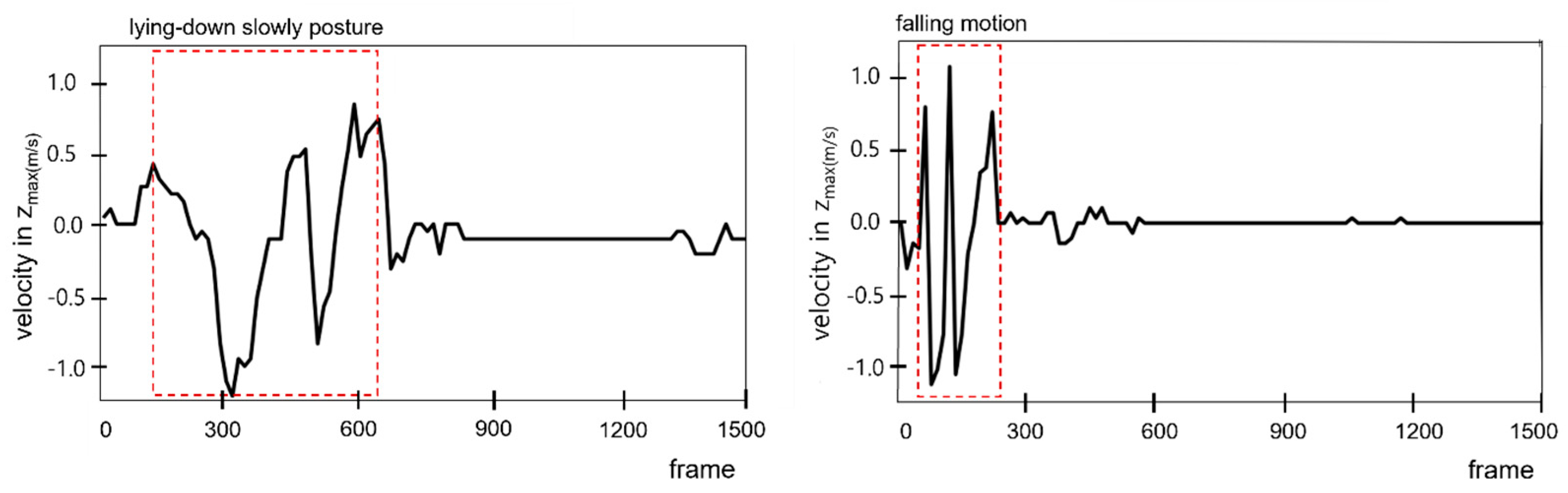

Additionally,

Figure 5 compares the velocity changes at z

max between movement that involves lying down slowly and falling. In

Figure 5, during the process of lying down slowly, the velocity of z

max exhibits a relatively gradual and consistent pattern over several hundred frames. In contrast, when a fall occurs, the velocity of z

max changes rapidly and irregularly within a very short period of time. This velocity pattern reflects the involuntary and uncontrolled nature of falls and serves as a critical criterion for distinguishing between movements associated with lying down slowly and falling.

This study quantitatively analyzed the changes in zmax and velocity at zmax to propose clear criteria for differentiating between movement when lying down slowly and movement when falling. This analysis contributes to improving the accuracy of real-time fall detection systems and provides a foundation for efficient application in various real-life scenarios.