1. Introduction

Cervical cancer development is strongly linked to reproductive factors. Research on age-specific incidence rates in populations without screening programs indicates that cervical cancer incidence begins to rise after menarche, increases steadily until menopause, peaks shortly thereafter, and then gradually declines [

1]. Postmenopausal new development of cervical cancer is rare [

1]. A large-scale epidemiological study identified a high number of full-term pregnancies and prolonged hormonal contraceptive use as independent risk factors, highlighting the significant role of sex hormones in cervical carcinogenesis [

2].

Most studies examining estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) expression in cervical cancer were conducted in the 1970s and involved a limited number of cases. These studies consistently reported ER and PR expression in the less differentiated layers of the squamous epithelium, with minimal fluctuations during the menstrual cycle [

3,

4,

5]. An analysis of neoplastic epithelium found no significant association between receptor expression and neoplasm severity, leading to inconclusive findings regarding their prognostic relevance in cervical cancer [

6]. Research on ER and PR expression in the stroma of normal and neoplastic epithelium remains limited [

4,

7]. One study reported variable ER and PR expression in stromal cells of the uterine cervix, independent of the menstrual cycle. Our previous study was the first to demonstrate that ER and PR expression in tumor stroma predicts a favorable prognosis in a cohort of 95 cervical cancer patients followed for over five years [

7].

Studies using mouse models have provided valuable insights into the role of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) in cervical carcinogenesis. Chung et al. [

8] demonstrated that ER and chronic estrogen exposure at physiological levels are essential for tumorigenesis in K14-HPVE6 or -HPVE7 transgenic mice, which developed cervical cancer with nearly 100% efficiency by 12 months. However, the removal of exogenous estrogen led to reduced tumor progression and partial regression of preexisting neoplasia [

9].

In contrast, PR functions as a ligand-dependent tumor suppressor in cervical cancer. In transgenic mice with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) lesions, treatment with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) and 17β-estradiol prevented cervical cancer development compared to control mice treated with 17β-estradiol alone. This finding suggests that progesterone and PR may act as tumor suppressors and offer therapeutic potential for CIN [

10].

To gain further understanding of the role of female sex hormones in cervical cancer development, this study examined sex hormone receptor expression in normal and neoplastic uterine cervix tissue across different severities of cervical neoplasia. Specifically, it aimed to elucidate the topological distribution of these receptors in the epithelium/carcinoma and stroma of the uterine cervix, ranging from normal tissue to CIN grades 2 and 3 (CIN2/3), carcinoma in situ (CIS), and invasive cervical carcinoma (ICC).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Patient Samples

This study comprehensively examined formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples, including CIN2/3, CIS, and ICC. The two protocols of this study were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital, Hualien, Taiwan. ICC specimens were retrieved from patients with cervical cancer who underwent radical hysterectomy at Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital between 2000 and 2010 (IRB104-151-A). Normal cervical specimens were obtained from patients who underwent total hysterectomy because of uterine myoma or adenomyosis. CIN2/3 and CIS specimens were collected during cervical biopsies and conizations at Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital from 2015 to 2017 (IRB104-100-A). A senior pathologist sectioned these paraffin blocks to confirm the diagnoses and adequacy of the stromal part. Cases that did not meet the diagnoses or lacked an adequate stromal component were excluded from the study. Clinical characteristics, including patient’s age, parity, and menopausal status, were also reviewed as part of the study.

2.2. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The expression levels of ERα, PR(A+B), and PRB in FFPE primary cervical cancer tissues were analyzed using IHC. The specimens were cut into 5-μm sections and mounted on slides. After deparaffinization in xylene, the slides were rehydrated through a graded alcohol series and then placed in running water. Immunohistochemical detection was performed using the Novolink Polymer Detection System (Novocastra Laboratories, UK). Briefly, antigen retrieval was performed by heating the slides in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Then, the slides were incubated with a peroxidase block to neutralize endogenous peroxidase activity. Subsequently, the slides were treated with either anti-ERα monoclonal antibody (dilution 1:250; ab108398; Abcam) or anti-PR antibody (PRB-specific YR85; dilution 1:100; ab32085; Abcam; PRA-specific NCL-L-PGR-312, which was found also binds PRB, hence marked as PR(A+B)[

6,

11]; dilution 1:100; PGR-312-L-F; Leica Biosystems) for 30 min [

6,

12]. Next, the slides were incubated with the Novolink polymer and then treated with DAB chromogen solution to visualize peroxidase activity. Each IHC assay was performed in duplicate or triplicate, depending on the amount of tissue available.

2.3. Staining Evaluation

Two experienced histopathologists from two different hospitals who were blinded to the clinical characteristics independently performed staining evaluation. The staining of ERα, PR(A+B), and PRB in tumor cells and adjacent stroma was performed. Although polymorphonuclear cell infiltration is uncommon in ER/PR evaluation, this potential interference was addressed by examining areas with minimal polymorphonuclear cell presence. The results were evaluated and scored using the immunoreactive score (IRS) [

13]. The IRS is reproducible, definable, and widely recognized as the “gold standard” scoring system. This system has been used for cervical cancer [

7] and various types of malignant gynecological tumors [

14,

15] and has been recommended by leading pathology organizations [

16,

17]. The percentage of positively stained cells was scored as follows: 0 (0%), 1 (1%–10%), 2 (11%–50%), 3 (51%–80%), or 4 (>80%). Meanwhile, the staining intensity was scored as follows: 0 (none), 1 (weak), 2 (moderate), or 3 (strong). Multiplying these two scores yielded an IRS of 0 to 12. In this study, the mean IRS from the two histopathologists for every FFPE cervical tissue was used for analysis.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Independent two-sample t test or one-way analysis of variance was used to detect the mean difference among different groups. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test. The Cochran–Armitage trend test was used to evaluate the underlying trends. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess the linear relationship between two covariates. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 17.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Predominant Expression of Sex Hormone Receptors in the Stroma of the Cervix with Progressive ERα Increase During Malignant Transformation

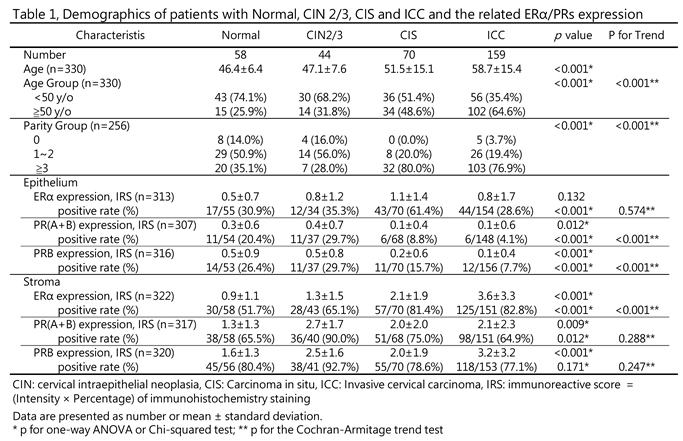

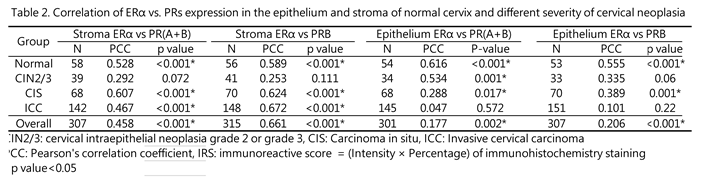

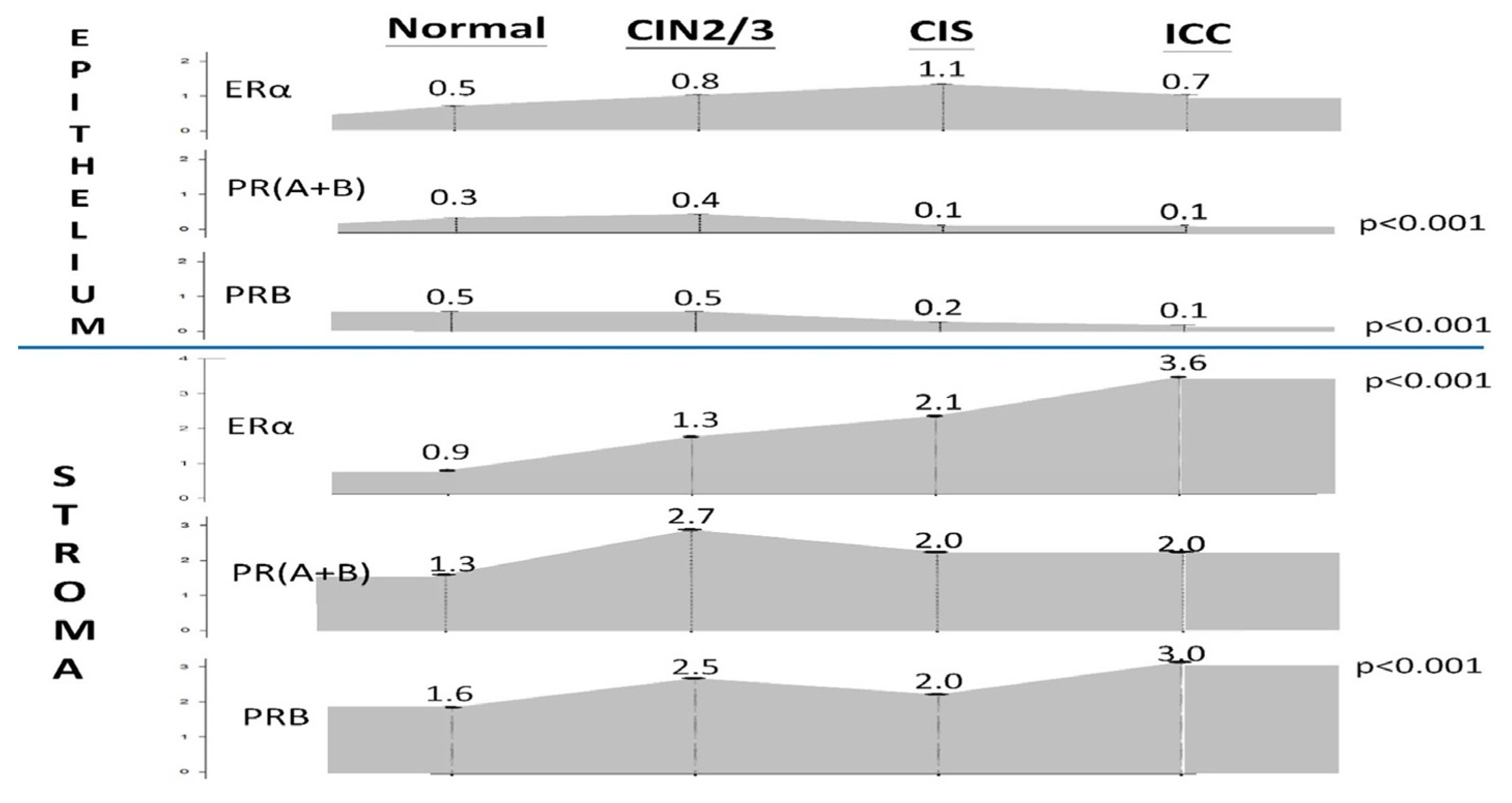

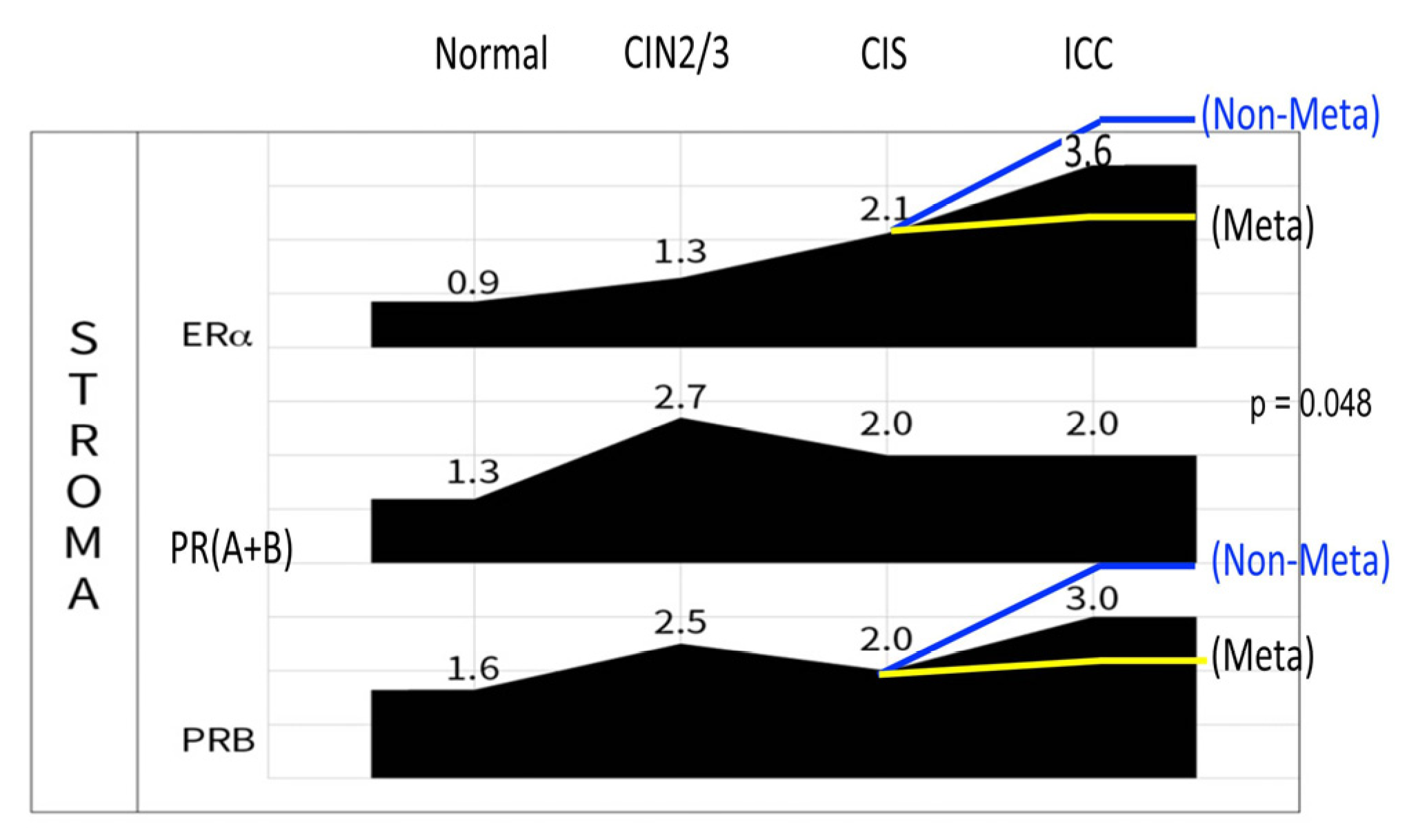

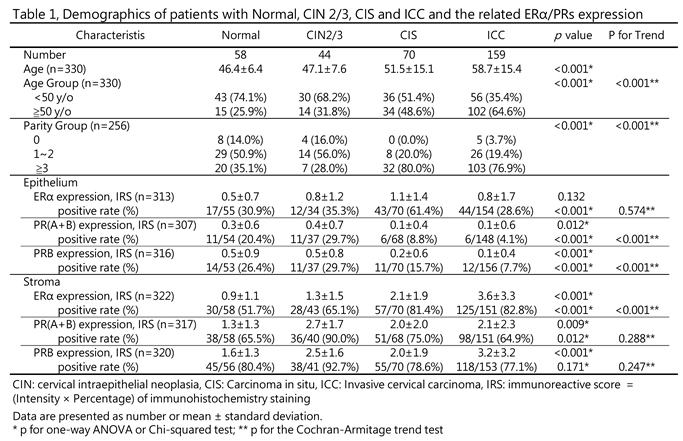

We performed a comparative analysis of the expression levels of ERα, PR(A+B), and PRB in the epithelial and stromal components of the cervix using 58 normal, 44 CIN2/3, 70 CIS, and 159 ICC specimens (

Figure 1,

Table 1). Across all four groups, the three receptors were predominantly expressed in the stroma (Table 1). The IRS and positive rate of ERα in the stroma and epithelium of normal, CIN2/3, CIS, and ICC specimens were 0.9 ± 1.1 (51.7%) vs. 0.5 ± 0.7 (30.9%), 1.3 ± 1.5 (65.1%) vs. 0.8 ± 1.2 (35.3%), 2.1 ± 1.9 (81.4%) vs. 1.1 ± 1.4 (61.4%), and 3.6 ± 3.3 (82.8%) vs. 0.8 ± 1.7 (28.6%), respectively (Table 1). As shown in Figure 2, a progressive increase in ERα expression was observed in the stroma throughout the process of cervical malignant transformation.

By contrast, the ERα expression in the epithelium of the normal cervix was only observed in a small portion of cases at low levels. However, it slightly increased in CIN2/3 and CIS specimens. Notably, during CIS to ICC transition, there was a significant decrease in the positive rate from 61.4% to 28.6% (Table 1).

3.2. Downregulation of PRs in the Epithelium During CIS to ICC Transition

The positivity rate of PR(A+B) and PRB in the cervical epithelium exhibited a significant decrease during CIN2/3–CIS transition (from 29.7% to 8.8% and 29.7% to 15.7%, respectively) and further decreased to 4.1% and 7.7% in ICC, respectively (p < 0.001) (

Table 1, Figure 2). During the process of cervical malignant transformation, the mean IRS decreased from 0.4 ± 0.7, 0.1 ± 0.4 to 0.1 ± 0.6 for PR(A+B) and from 0.5 ± 0.8, 0.2 ± 0.6 to 0.1 ± 0.4 for PRB, respectively.

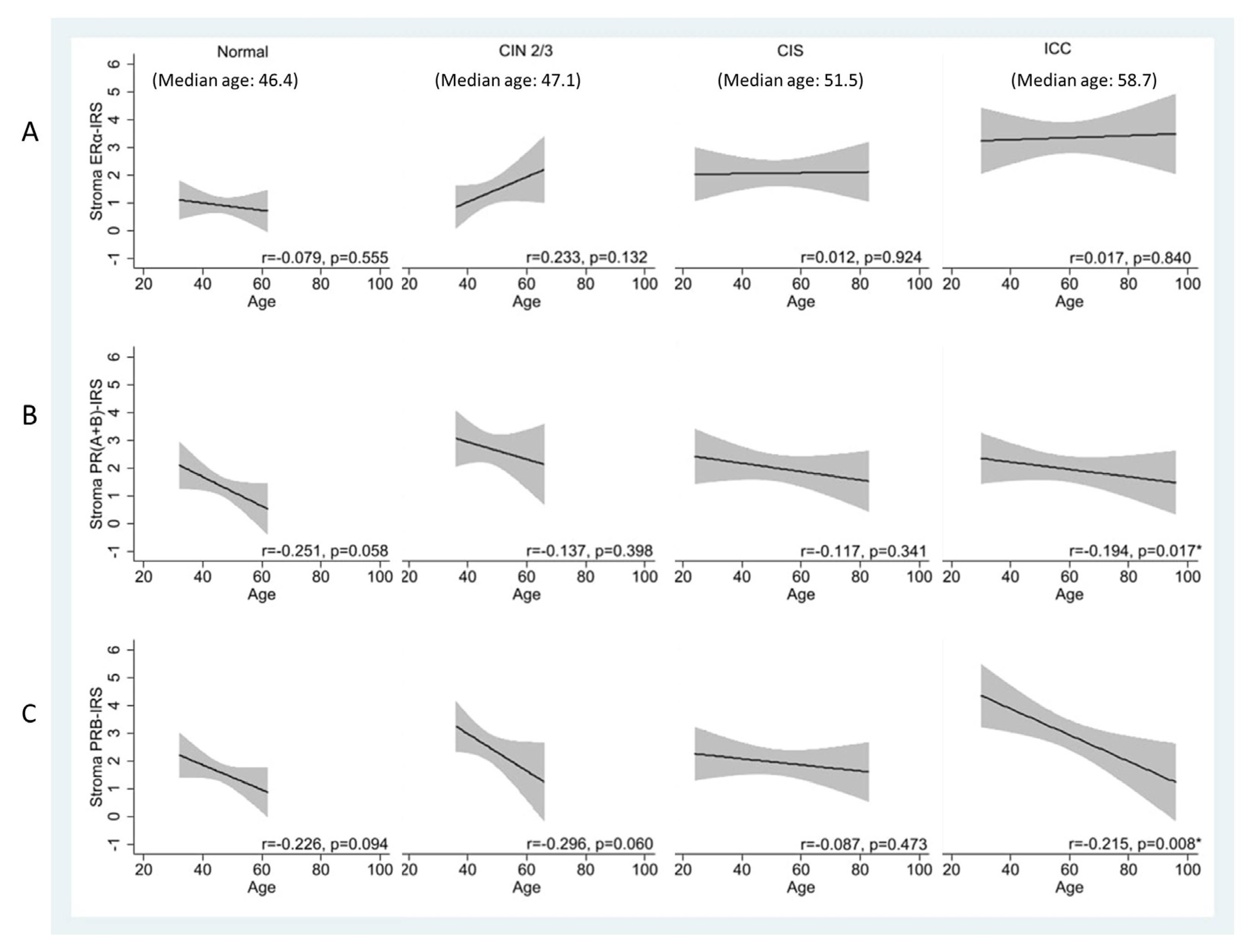

3.3. Age-Related Decrease in Stromal PRs Across Disease States, Except in CIS

We determined whether the expression of hormone receptors changes with age. In the stroma, there was an observable trend of age-related reduction in PR(A+B) and PRB levels in normal and CIN2/3 specimens. This trend was less prominent in CIS but reappeared in ICC (

Figure 3A–3C). The age-related changes in PRs were pronounced, particularly for PRB in ICC. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) decreased from 0.226 and 0.296 in the normal and CIN2/3 specimens to 0.087 in CIS specimens and then increased to 0.215 in ICC specimens (p = 0.008).

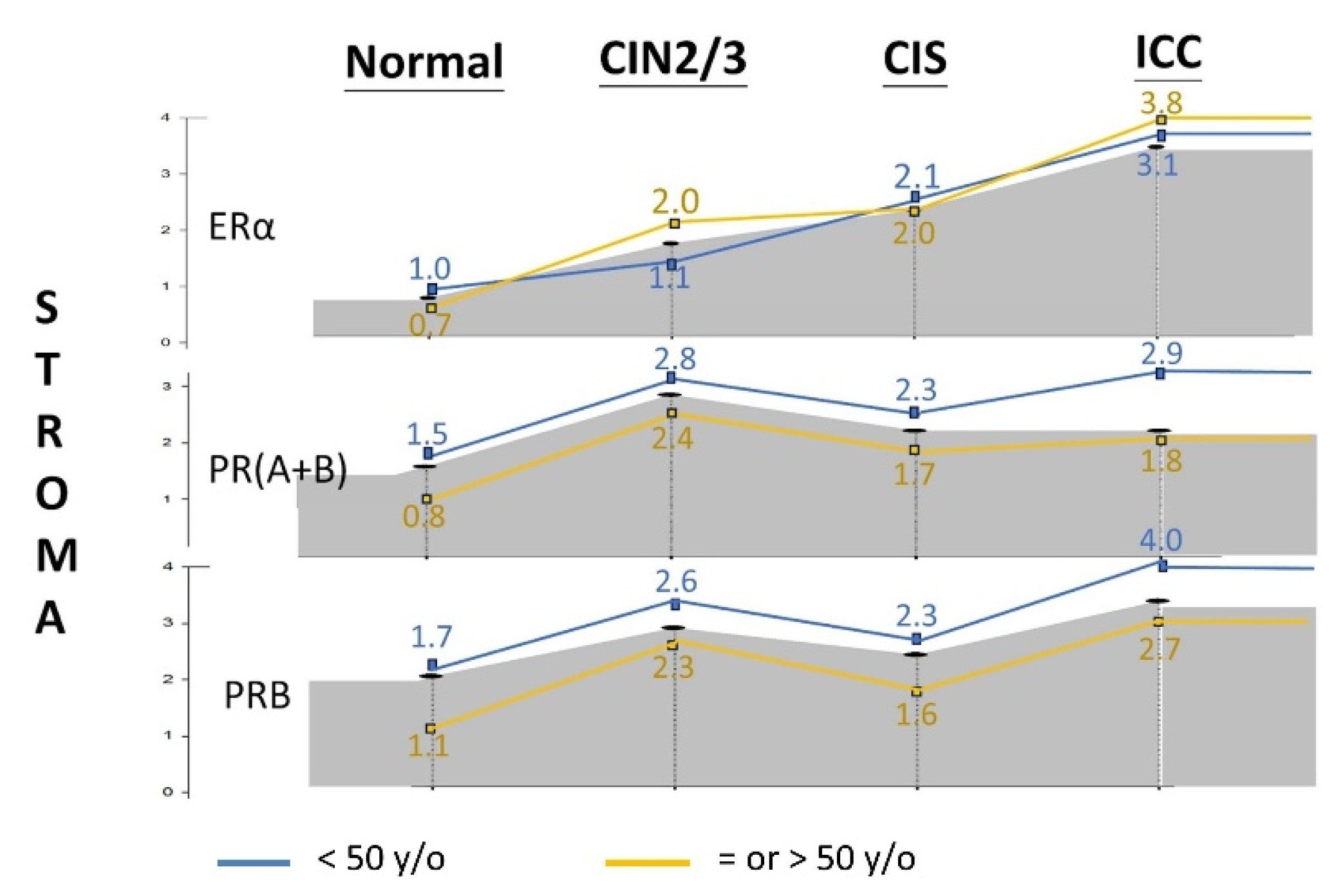

Considering the effect of age, we stratified the cohort into premenopausal (<50 years old) and menopausal (≥50 years old) groups. As shown in

Figure 4 and

Table S1, stromal PR(A+B) and PRB expression was significantly lower after menopausal age in each disease category. However, the difference was less pronounced for ERα.

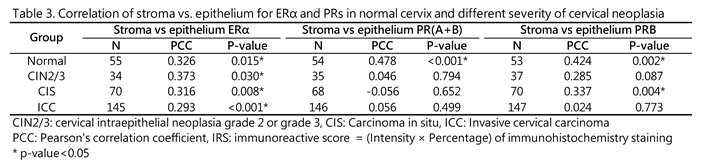

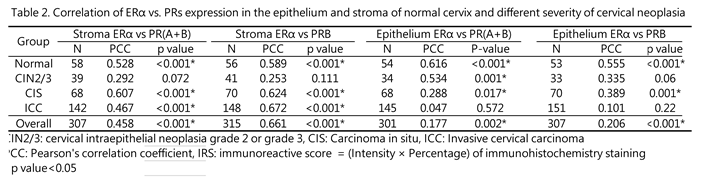

3.4. Disruption of ER–PR Expressional Correlation During CIN2/3 of Cervical Carcinogenesis

The PR gene encodes two isoforms of the PR protein: PRA and PRB. The E2-bound ERα upregulates the expression of both isoforms by acting on the PR promoter [

18,

19]. Indeed, the stromal expression levels of ERα and PRs were highly correlated in individual normal, CIS, and ICC specimens, with correlation coefficients of 0.528, 0.607, and 0.745, respectively (p < 0.001 for each). However, in CIN2/3 specimens, the ERα/PR correlation was disrupted (r = 0.292, p = 0.072) (

Table 2).

In the epithelium, the correlation between ER and PR was consistently strong in the normal cervix (r = 0.555, p < 0.001). However, this association weakened during malignant transformation, with varying rates for PR(A+B) and PRB. The ERα/PR(A+B) correlation decreased starting from CIS (r = 0.288, p = 0.17) and was completely lost in ICC (r = 0.047, p = 0.572). By contrast, the ERα/PRB association gradually diminished from normal tissue, CIN2/3, CIS to ICC, with r values of 0.555, 0.335, 0.389, and 0.101, respectively.

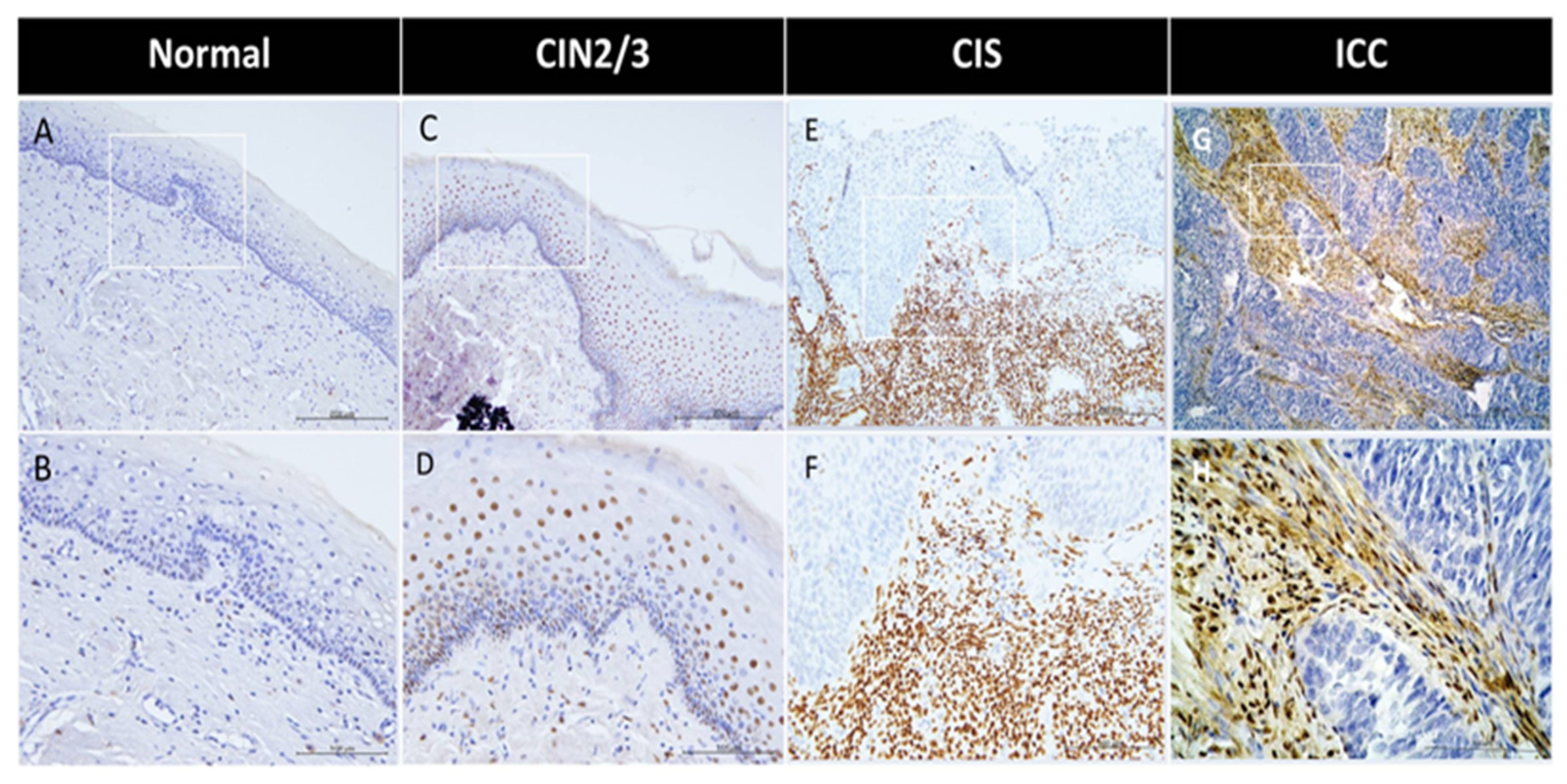

3.5. Disruption of the Topological Epithelium–Stroma Association of Sex Hormone Receptor Expression During Malignant Transformation

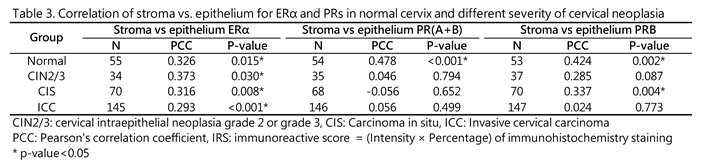

The interaction between the epithelial and stromal compartments is crucial for the remodeling and function of the uterine cervix during pregnancy and the menstrual cycle. Therefore, we examined the topological relationship of ER/PR expression in the epithelium and stroma of cervixes across the normal and different cervical neoplasia groups. We found a strong epithelium–stroma link of ERα throughout disease progression. With regard to PRB, the association was robust in normal tissues (r = 0.424, p = 0.002), significantly weakened in CIN2/3 (r = 0.282, p = 0.087), recovered in CIS (r = 0.377, p = 0.004), and completely disrupted in ICC (r = −0.002, p = 0.980). In terms of PR(A+B), the topological relationship significantly weakened from normal tissue (r = 0.478, p < 0.001) to CIN2/3 (r = 0.046) and remained low in CIS (r = −0.056) and ICC (r = 0.017) (Table 3).

4. Discussion

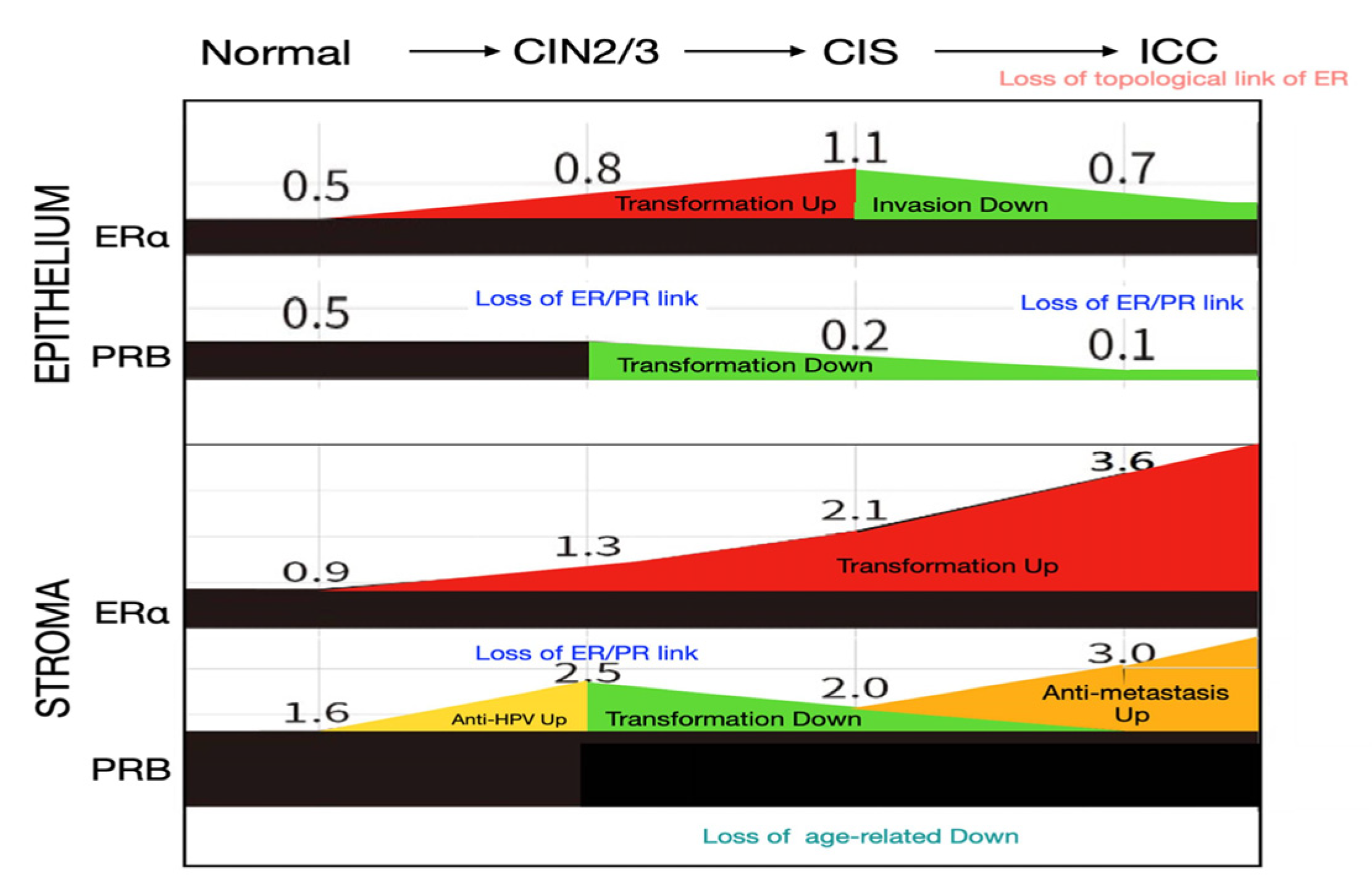

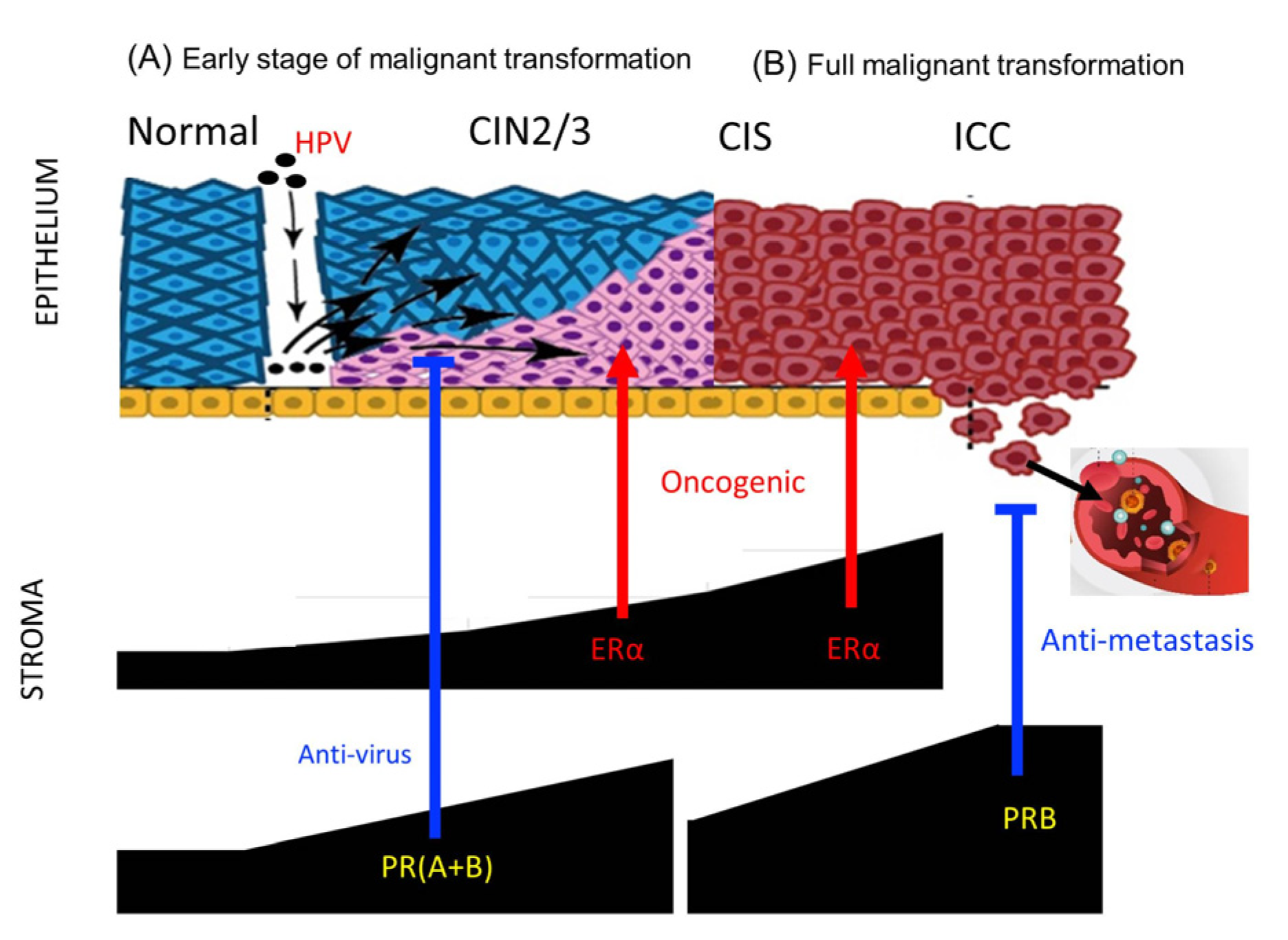

This study provides a comprehensive overview of the temporal and topological changes in ER/PR expression in the epithelium and stroma of the uterine cervix throughout the malignant transformation process (Figure 5). We found that sex hormone receptors are highly expressed in the stroma, a detail that is often overlooked in previous research, highlighting their critical role in the malignant transformation process.

The key findings include a progressive upregulation of stromal ERα during cervical carcinogenesis, in contrast with a downregulation of PRs in the transformed epithelium of CIS and ICC. The stromal PRB showed an early increase from normal tissue to CIN2/3, a decrease during CIN2/3 to CIS transition, and a rebound at the ICC stage.

The coexpressional relationship between ER and PR was disrupted during the actively transforming CIN2/3 stage in the epithelium and stroma, and a further disruption was observed in the stroma at the ICC stage. Notably, the topological relationship of hormone receptor expression in the epithelium and stroma remained strong for ERα across all disease stages, whereas it was diminished in CIN2/3 and completely lost in ICC for PRB. With regard to PR(A+B), significant disruptions were observed in CIN2/3 and more advanced stages.

This study revealed for the first time a progressive upregulation of stromal ERα during cervical carcinogenesis, with levels increasing fourfold from normal cervix to ICC (

Figure 1). Estrogen exposure has been recognized as an independent risk factor in cervical cancer development. A nationwide, population–based study demonstrated that the use of antiestrogen is associated with a significant reduction in cervical dysplasia [

20]. According to transgenic studies involving HPVE6/E7 transformation of the mouse cervix, estradiol and ERα play critical roles throughout the carcinogenic process, from early atypical lesions to dysplasia and invasive carcinomas [

18,

19]. Notably, ER signaling in the stroma, rather than in the epithelium, is essential for carcinogenesis in transgenic mice [

20,

21]. Although ERα levels in the epithelium of CIN2/3 and CIS also exhibited increases related to transformation, a contrasting decrease was observed during CIS to ICC progression. This decline suggests an invasion-associated downregulation, which is likely influenced by paracrine signaling from the stroma.

In the transition from normal tissue to CIN2/3, there was a significant increase in PR(A+B) and PRB expression levels in the stroma. This observation supports the notion that progesterone plays an antiviral and anti-transformation role. A previous study found that progesterone is induced in mice infected with various DNA and RNA viruses, where it activates downstream antiviral genes and enhances innate antiviral responses in immune cells [

22]. Furthermore, an epidemiological study found that the use of Depo-Provera (MPA, a synthetic form of progesterone) was linked to a reduced risk of cervical cancer among women infected with human papillomavirus (HPV)[

23]. In a transgenic HPV-induced cervical cancer mouse model, MPA treatment effectively prevented cancer development, which was characterized by decreased cell proliferation and increased apoptosis in CIN lesions. Notably, this protective effect was absent when PR expression was genetically eliminated [

10]. Thus, progesterone may exert an antiviral effect through its action on PRs in the stroma during the early stages of cervical transformation with persistent HPV infection (

Figure 5).

The development of the Müllerian epithelium is regulated by estrogen and progesterone through paracrine mechanisms, which necessitate the crosstalk of their receptors across the basement membrane [

24,

25]. The PR changes in the stroma of the transforming cervix may reflect different needs in multistage carcinogenesis. In the normal to CIN2/3 stage, stromal PR increases to combat HPV infection and transformation. In the CIN2/3–CIS progression stage, a decrease in PR is required for advancing the transformation. Indeed, we observed a decrease of PR in the stroma and epithelium during this transition (

Figure 2). In the CIS stage, wherein the full thickness of the epithelium is transformed, the new topological interaction between the epithelium and stroma is related to invasion and anti-invasion activities, respectively. Meanwhile, the oncogenic ERα in the stroma further increases (

Figure 5).

Epithelial PR reportedly plays a tumor suppressor role in a transgenic mouse model of cervical carcinogenesis. The deletion of one or both PGR alleles in the cervical epithelium promoted spontaneous CIN and ICC, with all lesions showing low PR expression [

21]. Our IHC study of the human cervix corroborates this finding, demonstrating a progressive downregulation of epithelial PR throughout the malignant transformation process (

Figure 4,

Figure 5). During CIS to ICC transition, ERα was also found to be downregulated. ERα in ICC and precursor cell lines reportedly plays an anti-invasive role. The knockdown of the ESR1 gene resulted in a more invasive phenotype in cells with high ERα expression, whereas the restoration of the ESR1 gene decreased cell invasion in cells with low ERα expression [

26].

In this study, we found that the expressions of ERα and PRs in the epithelium and stroma of the cervix are highly correlated. This finding is consistent with the transactivating function of estrogen-bound ERα at the PGR promoter [

27]. The coexpressional relationship between ERα and PRs was broken in the epithelium and stroma of CIN2/3 and also in the carcinoma part of ICC. Moreover, we discovered that although cervical carcinomas maintained consistent levels of ERα across different ages, stromal PRB expression exhibited a steady decline with advancing age at diagnosis. This finding suggests a non-genomic, age-related control of PR expression in the ICC epithelium and CIN2/3 epithelium and stroma.

In a recent study, we observed a significant association between stromal PRB expression and less distant metastasis in ICC [

7,

28]. In an ICC cohort of 169 cases with >10 years of follow-up, we found that stromal PRB independently conferred a lower risk (hazard ratio 0.39, 95% CI: 0.18–0.87, p = 0.022) of 5-year mortality considering age, histology, FIGO stage, tumor differentiation, and lymphatic and hematogenous metastasis. In particular, stromal PR expression was associated with a lower rate of hematogenous distant metastasis (p = 0.011). We carefully observed for an increase of stromal PRB in the CIS to ICC stage of cervical cancer and found an approximately 50% increase on average. When stratified by distant metastasis status, the median IRS was significantly higher in the nonmetastatic group (3.24 ± 3.18) than in the metastatic group (2.40 ± 3.71, p = 0.048)[

28]. Thus, in the ICC cervix, PRB tends to increase to fight against cancer metastasis, whereas a downregulation of PRB due to unknown mechanisms facilitates distant metastasis (

Figure 6,

Figure 7).

This study has several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to comprehensively examine ER and PR expression levels in the epithelium and stroma of the cervix across various stages of cervical neoplasia. The histological examination was performed meticulously, with paraffin blocks being sectioned by a senior pathologist to ensure accurate diagnosis and evaluation of the stroma. Moreover, ER and PR expression levels were independently assessed by two senior gynecological pathologists from different hospitals, enhancing the reliability of the results. We also deliberately chose to exclude CIN1 cases, which are typically transient, thereby focusing on more relevant stages of cervical carcinogenesis.

However, there are limitations to consider. One significant limitation is the inability to specifically detect the PRA isoform because of the lack of a dedicated antibody, which restricted the study to measuring the combined PR(A+B) expression levels. Furthermore, the lack of analysis of HPV status may limit the understanding of how HPV may influence receptor expression in cervical neoplasia. In our previous study, we found that ER/PR expression in the stroma or epithelium of the ICC cervix was not related to HPV infection status [

7]. A previous study also showed no difference in stroma ER expression in HPV-positive and HPV-negative normal and CIN cervixes [

29]. Lastly, as the study was conducted in a specific cohort with defined inclusion criteria, the findings may not be generalizable to all populations or settings

5. Conclusions

ER and PR are cohesively expressed in the uterine cervix, exhibiting a topological link in their expression between the epithelium and stroma. However, the expression in the stroma is quantitatively and functionally dominant in the developmental and adult states, and this stromal dominance intensifies throughout the decades-long process of cervical carcinogenesis. The progressive increase of ERα reflects its important oncogenic role in HPV-induced carcinogenesis. Meanwhile, stromal PR plays diverse roles as it suppresses viral infection during the active transformation from normal tissue to CIN2/3, plays an antitransformation role prior to CIS, and acts as an antimetastatic factor in ICC. Notably, PR expression in the epithelium appears to be passively downregulated in favor of the malignant transformation process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MK.H. and TY.C.; methodology MK.H.,JH.W. and TY.C.; software, JH.W.; validation, JH.W., MK.H. and TY.C.; formal analysis, JH.W. ; investigation, MK.H. and TY.C.; resources, MH.L.,CC.S. and CH.C.; data curation, MH.L.,CC.S. and CH.C; writing—original draft preparation, MK.H. and TY.C.; writing—review and editing, MK.H., JH.W., and TY.C.; visualization, MH.L.,CC.S. and CH.C ; supervision, MK.H. and TY.C.; project administration, MK.H. ; funding acquisition, MK.H. and TY.C.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, R.O.C. (MOST 105-2314-B-303-005) and the Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital, Hualien, Taiwan, R.O.C (TCRD105-25).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All protocols of the study were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital, Hualien, Taiwan (IRB104-151-A & IRB104-100-A).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to no personally identifiable information was included in the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. Wen-Xiang Chen for his technical assistance in tissue staining. Mr. Chen has consented to this acknowledgment and declared no conflict of interest.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ER |

estrogen receptor |

| PR |

progesterone receptor |

| PRB |

progesterone receptor isoform B |

| PR(A+B) |

progesterone receptor isoform A and B |

| CIS |

carcinoma in situ |

| CIN2/3 |

cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 and 3 |

| FFPE |

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded |

| IHC |

immunohistochemistry |

| IRS |

immunoreactive score |

| ICC |

invasive cervical carcinoma |

References

- Plummer, M. , et al., Time since first sexual intercourse and the risk of cervical cancer. Int J Cancer, 2012. 130(11): p. 2638- 44.

- International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical, C. Cervical carcinoma and reproductive factors: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 16,563 women with cervical carcinoma and 33,542 women without cervi cal carcinoma from 25 epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer, 2006. 119(5): p. 1108-24.

- Mosny, D.S. , et al., Immunohistochemical investigations of steroid receptors in normal and neoplastic squamous epithelium of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol, 1989. 35(3): p. 373-7.

- Scharl, A. , et al., Immunohistochemical study of distribution of estrogen receptors in corpus and cervix uteri. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 1988. 241(4): p. 221-33.

- Nonogaki, H. , et al., Estrogen receptor localization in normal and neoplastic epithelium of the uterine cervix. Cancer, 1990. 66(12): p. 2620-7.

- Mote, P.A. , et al., Detection of progesterone receptor forms A and B by immunohistochemical analysis. J Clin Pathol, 2001. 54(8): p. 624-30.

- Hong, M.K. , et al., Expression of Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor in Tumor Stroma Predicts Favorable Prognosis of Cervical Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer, 2017. 27(6): p. 1247-1255.

- Chung, S.H. , et al., Requirement for estrogen receptor alpha in a mouse model for human papillomavirus-associated cervical cancer. Cancer Res, 2008. 68(23): p. 9928-34.

- Chung, S.H., S. Franceschi, and P.F. Lambert, Estrogen and ERalpha: culprits in cervical cancer? Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2010. 21(8): p. 504-11.

- Baik, S., F. F. Mehta, and S.H. Chung, Medroxyprogesterone Acetate Prevention of Cervical Cancer through Progester one Receptor in a Human Papillomavirus Transgenic Mouse Model. Am J Pathol, 2019. 189(12): p. 2459-2468.

- Fabris, V. , et al., Isoform specificity of progesterone receptor antibodies. J Pathol Clin Res, 2017. 3(4): p. 227-233.

- Tone, A.A. , et al., Decreased progesterone receptor isoform expression in luteal phase fallopian tube epithelium and high-grade serous carcinoma. Endocr Relat Cancer, 2011. 18(2): p. 221-34.

- Remmele, W. and H.E. Stegner, [Recommendation for uniform definition of an immunoreactive score (IRS) for immune histochemical estrogen receptor detection (ER-ICA) in breast cancer tissue]. Pathologe, 1987. 8(3): p. 138-40.

- Shabani, N. , et al., Prognostic significance of oestrogen receptor alpha (ERalpha) and beta (ERbeta), progesterone recep tor A (PR-A) and B (PR-B) in endometrial carcinomas. Eur J Cancer, 2007. 43(16): p. 2434-44.

- Lenhard, M. , et al., Steroid hormone receptor expression in ovarian cancer: progesterone receptor B as prognostic marker for patient survival. BMC Cancer, 2012. 12: p. 553.

- Fedchenko, N. and J. Reifenrath, Different approaches for interpretation and reporting of immunohistochemistry analysis results in the bone tissue—a review. Diagn Pathol, 2014. 9: p. 221.

- Kaemmerer, D. , et al., Comparing of IRS and Her2 as immunohistochemical scoring schemes in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Int J Clin Exp Pathol, 2012. 5(3): p. 187-94.

- Flototto, T. , et al., Molecular mechanism of estrogen receptor (ER)alpha-specific, estradiol-dependent expression of the progesterone receptor (PR) B-isoform. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 2004. 88(2): p. 131-42.

- Sahlin, L. , et al., Tissue- and hormone-dependent progesterone receptor distribution in the rat uterus. Reprod Biol Endocrinol, 2006. 4: p. 47.

- Hsieh, C.J. , et al., Antiestrogen use reduces risk of cervical neoplasia in breast cancer patients: a population-based study. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(17): p. 29361-29369.

- Park, Y. , et al., Progesterone Receptor Is a Haploinsufficient Tumor-Suppressor Gene in Cervical Cancer. Mol Cancer Res, 2021. 19(1): p. 42-47.

- Su, S. , et al., Modulation of innate immune response to viruses including SARS-CoV-2 by progesterone. Signal Trans duct Target Ther, 2022. 7(1): p. 137.

- Harris, T.G. , et al., Depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate and combined oral contraceptive use and cervical neoplasia among women with oncogenic human papillomavirus infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2009. 200(5): p. 489 e1-8.

- Cunha, G.R. , Stromal induction and specification of morphogenesis and cytodifferentiation of the epithelia of the Mul lerian ducts and urogenital sinus during development of the uterus and vagina in mice. J Exp Zool, 1976. 196(3): p. 361-70.

- Kurita, T., P. S. Cooke, and G.R. Cunha, Epithelial-stromal tissue interaction in paramesonephric (Mullerian) epithelial differentiation. Dev Biol, 2001. 240(1): p. 194-211.

- Zhai, Y. , et al., Loss of estrogen receptor 1 enhances cervical cancer invasion. Am J Pathol, 2010. 177(2): p. 884-95.

- Diep, C.H., H. Ahrendt, and C.A. Lange, Progesterone induces progesterone receptor gene (PGR) expression via rapid activation of protein kinase pathways required for cooperative estrogen receptor alpha (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) genomic action at ER/PR target genes. Steroids, 2016. 114: p. 48-58.

- Mun-Kun Hong, J.-H.W. , Ming-Hsun Li, Cheng-Chuan Su, Tang-Yuan Chu, Progesterone receptor isoform B in the stroma of squamous cervical carcinoma: An independent favorable prognostic marker correlating with hematogenous metastasis. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2024. 63(6): p. 853-860.

- Coelho, F.R. , et al., Estrogen and progesterone receptors in human papilloma virus-related cervical neoplasia. Braz J Med Biol Res, 2004. 37(1): p. 83-8.

Figure 1.

Progressive increase of stromal ERα in cervical cancer development, from normal to CIN2/3, CIS, and ICC cervical speci mens. Representative IHC images of ERα in the normal cervix (A, B), CIN2/3 (C, D), CIS (E, F), and ICC (G, H) are shown. Magnification: 200× in A, C, E, and G; 400× in B, D, F, and H.

Figure 1.

Progressive increase of stromal ERα in cervical cancer development, from normal to CIN2/3, CIS, and ICC cervical speci mens. Representative IHC images of ERα in the normal cervix (A, B), CIN2/3 (C, D), CIS (E, F), and ICC (G, H) are shown. Magnification: 200× in A, C, E, and G; 400× in B, D, F, and H.

Figure 2.

Changes in the average IRS of ERα and PR expression levels in the epithelium and stroma of normal, CIN2/3, CIS, and ICC cervical specimens.

Figure 2.

Changes in the average IRS of ERα and PR expression levels in the epithelium and stroma of normal, CIN2/3, CIS, and ICC cervical specimens.

Figure 3.

Age-specific IRS of ER and PR expression levels in the stroma of normal, CIN2/3, CIS, and ICC cervical specimens.

Figure 3.

Age-specific IRS of ER and PR expression levels in the stroma of normal, CIN2/3, CIS, and ICC cervical specimens.

Figure 4.

IRS of stromal PR expression levels in different severities of cervical neoplasia, stratified by age [blue line: < 50 years old(y/o); yellow line: = or > 50 y/o].

Figure 4.

IRS of stromal PR expression levels in different severities of cervical neoplasia, stratified by age [blue line: < 50 years old(y/o); yellow line: = or > 50 y/o].

Figure 5.

Possible significance of changes in ERα and PR expression levels in the epithelium and stroma of the cervix during malignant transformation. Increases (shown in red and yellow) and decreases (shown in green) in IRS at each stage of cervical carcinogenesis are presented, with potential significance noted. Moreover, the loss of coexpressional links between ER and PRs, the loss of topological coexpression of receptors in the epithelium and stroma, and age-related downregulation are highlighted.

Figure 5.

Possible significance of changes in ERα and PR expression levels in the epithelium and stroma of the cervix during malignant transformation. Increases (shown in red and yellow) and decreases (shown in green) in IRS at each stage of cervical carcinogenesis are presented, with potential significance noted. Moreover, the loss of coexpressional links between ER and PRs, the loss of topological coexpression of receptors in the epithelium and stroma, and age-related downregulation are highlighted.

Figure 6.

Difference of the stromal PRB IRS in distantly metastatic (yellow line) and non-metastatic (blue) ICCs. Risen ERα and PRB was associated less distant metastasis.

Figure 6.

Difference of the stromal PRB IRS in distantly metastatic (yellow line) and non-metastatic (blue) ICCs. Risen ERα and PRB was associated less distant metastasis.

Figure 7.

Possible roles of stromal P4/PR in HPV infection and cervical cancer progression. (A) At the early stage of malignant transformation (intraepithelial neoplasia), stromal progesterone and PRs promote antiviral innate immunity to counteract HPV infection, whereas stromal ERα is necessary for HPV-induced carcinogenesis. (B) After complete transformation or in invasive cancer, upregulated stromal PRB inhibits hematogenous metastasis. In cases where stromal PRs are not upregulated or are lost, distant metastasis may develop, which is associated with poor prognosis.

Figure 7.

Possible roles of stromal P4/PR in HPV infection and cervical cancer progression. (A) At the early stage of malignant transformation (intraepithelial neoplasia), stromal progesterone and PRs promote antiviral innate immunity to counteract HPV infection, whereas stromal ERα is necessary for HPV-induced carcinogenesis. (B) After complete transformation or in invasive cancer, upregulated stromal PRB inhibits hematogenous metastasis. In cases where stromal PRs are not upregulated or are lost, distant metastasis may develop, which is associated with poor prognosis.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).