1. Background

1.1. The Role of Vasoconstrictor Agents in the Scheme of Septic-Shock Treatment

Vasoconstriction agents are a pillar in the acute therapeutic management of patients suffering from septic shock [

1,

2,

3]. Nowadays, septic-shock treatment guidelines recommend norepinephrine as the first-line choice followed by epinephrine or vasopressin, even before fluid resuscitation is fully completed [

4,

5,

6]. However, there is no clear evidence that any single drug consistently improves microvascular flow in septic-shock patients [

7]. Vasopressors such as noradrenalin and vasopressin are commonly used to restore hemodynamic stability in the face of very low cardiac output and vascular tone in severe septic patients [

8,

9,

10].

1.2. Peripheral Limb Ischemia Resulting from Vasoconstrictor Agents

The literature contains numerous case studies of patients of all ages, who suffered from vasopressor-induced acute limb ischemia (VIALI), a condition that endangered patients’ limbs with variable measures taken to minimize the damage, e.g., application of local and systemic vasodilator agents alongside reduction of vasopressor dosages [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Oh and Song found that 0.8% of septic shock survivors in a South Korean cohort developed peripheral limb ischemia, ultimately leading to limb amputations. Certain comorbidities and treatments were associated with an increased risk of peripheral gangrene and limb loss [

15].

Several authors have examined the underlying mechanisms of vasoplegia in sepsis and defined risk factors associated with VIALI, such as prolonged exposure to vasopressors and the need for combination therapy with multiple vasopressor agents [

16,

17]. A meta-analysis assessing the effects and safety of vasopressin receptor agonists compared to catecholamines in septic shock patients across 20 randomized controlled trials, suggests that vasopressin use significantly increased the risk of digital ischemia [

18].

1.3. Aim of the Current Study

The current study aimed to evaluate the adverse clinical outcomes associated with vasopressor use in patients with septic shock. Our main aim was the assessment of the potential risk of resulting amputations and possibly adding information regarding the option of personalizing the treatment amongst this group of critically ill patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics Committee Approval

This research was designed, and executed, in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Accordingly, it was approved by the Chaim Sheba Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB, approval # SMC-23-0348).

2.2. Study Patients

All adult patients aged 18 years or older who were admitted to the Chaim Sheba Medical Center between 2010 and 2023 with a primary diagnosis of septic shock were initially included in the study. Patients electronic medical records were approached only after the IRB approved the study and waived the need for informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study. Patients who developed sepsis as a complication of treatment for another primary medical condition were excluded from the study. Additionally, those with insufficient data or those who were admitted to Intensive Care Units (ICUs) were excluded from the analysis in order to focus on patients treated in the settings of general-internal medicine departments. The remaining eligible patients were categorized into two groups: those who received vasopressor therapy and those who did not. Each group was further subdivided based on whether the patient underwent amputation during their hospitalization.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were compared between the study groups using a Chi-squared test. We then described each categorical variable by showing its prevalence, shown as a percentage (%) out of the entire cohort, and of each of the study groups. Continuous numeric variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test. A Student's t-test was utilized to compare normally distributed variables between the study groups, and when normality was rejected, we conducted a Mann–Whitney U test instead. Normally distributed numeric variables are described as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), while non-normal variables are described as the median with interquartile range (IQR).

A logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of the use of vasopressors on the likelihood of limb amputation. Results of the logistic regression analysis are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for both univariate and multivariate models, the latter adjusting for potential confounders. Statistical significance was determined as a P-value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.3.0, R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

3. Results

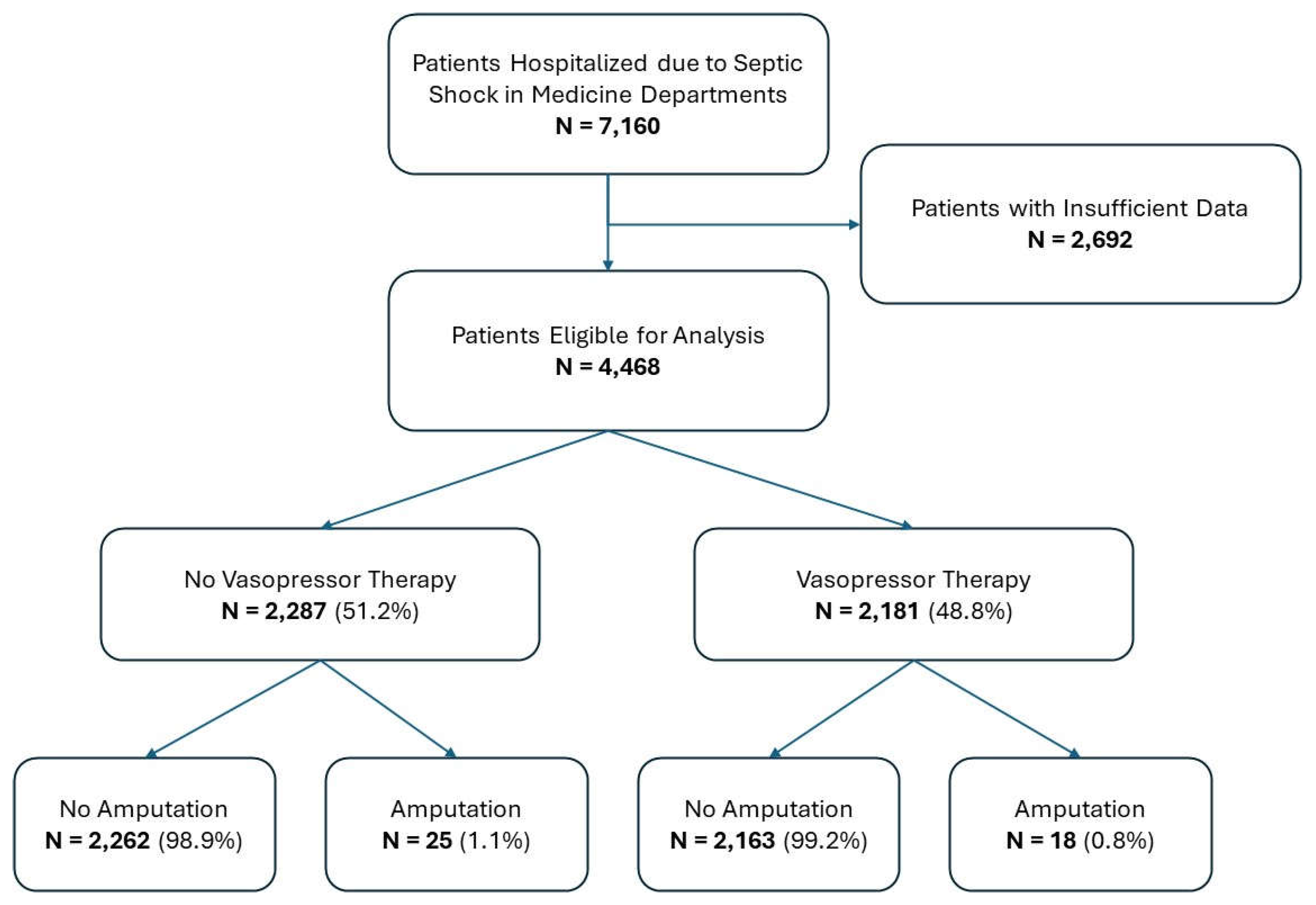

Between 2010 and 2023, a total of 7,160 patients were admitted to the hospital with a primary diagnosis of septic shock. Of these, 2,692 patients were excluded due to insufficient data. The remaining 4,468 eligible patients were included in the analysis. These patients were classified into two groups based on vasopressor therapy: 2,181 received vasopressors, while 2,287 did not. Among those patients who received vasopressor therapy, 18 (0.8%) underwent amputation during hospitalization, compared to 25 patients (1.1%) in the non-vasopressor group. The patient cohort flow is illustrated in a CONSORT flow diagram (

Figure 1).

Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics of the 4,468 patients included in the study, categorized into those who received vasopressors (N = 2,181) and those who did not (N = 2,287). Several significant differences were observed between the two groups. In the demographic features, the vasopressor group had a higher proportion of male patients (63.5% vs. 57.9%; p < 0.001), while the median age was similar between groups (72.7 vs. 73.3 years; p = 0.54). Regarding medical background, chronic kidney disease (CKD) was more prevalent in the vasopressor group (49.1% vs. 43.4%; p < 0.001), whereas the prevalence of congestive heart failure (CHF) (16.9% vs. 15.4%; p = 0.2), diabetes (26.9% vs. 24.5%; p = 0.07), and peripheral vascular disease (5.5% vs. 5.0%; p = 0.52) was similar between groups.

Laboratory findings indicated that patients in the vasopressor group had lower minimal albumin levels (2.2 vs. 2.4 g/dL; p < 0.001) and higher creatinine levels both at admission (1.48 vs. 1.35 mg/dL; p < 0.001) and during hospitalization (2.03 vs. 1.68 mg/dL; p < 0.001), while minimal hemoglobin levels remained similar (10.19 vs. 10.1 g/dL; p = 0.17).

Regarding clinical outcomes, patients in the vasopressor group had a higher incidence of prolonged department stays (49.6% vs. 46.5%; p = 0.04) and prolonged hospital stays (65.4% vs. 61.5%; p = 0.007). Although in-hospital amputation rates were similar between groups (0.8% vs. 1.1%; p = 0.44), the vasopressor group exhibited significantly higher rates of in-hospital acute kidney injury (28.1% vs. 18.4%; p < 0.001) and in-hospital mortality (32.3% vs. 27.4%; p < 0.001).

Table 2 presents the results of a logistic regression analysis assessing risk factors for amputation. In the univariate analysis, treatment with vasopressors was not significantly associated with an altered risk of amputation (OR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.4 - 1.38; p = 0.36). Olderage was associated with significantly lower odds of amputation (OR = 0.97 per year, 95% CI 0.95 - 0.99; p = 0.001), while male gender showed no significant correlation (OR = 0.83, 95% CI 0.44 - 1.6; p = 0.559). Peripheral vascular disease (PVD) was identified as the strongest risk factor, with a significantly increased risk of amputation (OR = 19.3, 95% CI 9.47 - 39.78; p < 0.001). Other comorbidities, including congestive heart failure (OR = 1, 95% CI 0.44 - 2.11; p = 0.99), chronic kidney disease (OR = 1.07, 95% CI 0.53 - 2.15; p = 0.85), and diabetes (OR = 1.28, 95% CI 0.63 - 2.55; p = 0.48), were not significantly associated with amputation risk. Similarly, in-hospital acute kidney injury (OR = 0.63, 95% CI 0.25 - 1.38; p = 0.27), treatment with noradrenalin (OR = 0.77, 95% CI 0.4 - 1.46; p = 0.43), vasopressin (OR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.02 - 2.38; p = 0.46), or vasodilator therapy (OR = 2.32, 95% CI 0.12 - 14.9; p = 0.46), were not significantly associated with an increased risk of amputation.

4. Discussion

Advancements in modern medicine have significantly improved survival rates for patients with sepsis and septic shock. As a result, older, and more critically ill patients are now surviving such hospitalizations in both general internal medicine departments and intensive care units. These improvements are largely attributed to aggressive management of hemodynamic instability alongside with application of advanced antimicrobial therapies. In addition to volume loading, the use of vasopressor medications rapidly re-institute the arterial blood pressure and replenish target-organ-perfusion. Nevertheless, this aggressive management comes at a cost! It has long been recognized that vasopressor therapy is associated with peripheral vasoconstriction and potential ischemic damage to the patient’s extremities. The association between patients’ personalized characteristics: older age, co-morbidities, heightened inflammation, and vasopressor use is naturally considered as increasing the risk of amputations and damage to target organs.

Taking a step back, we should search for areas in which personalized medicine is taking a significant place in the realm of ICU / the care of critically ill patients. Such trials were made in the domain of prediction (Park and co. regarding application of artificial intelligence for the purpose of early detection of delirium [

19]), organized, multifaceted care as described by LaRosa and Kudchadkar [

20] and even searching for genetic associations in critically ill patients as published a systematic review by Zhang and co. [

21]. Currently, prediction is generally system-based and is related to specific target organs’ damages:

Acute kidney injury (AKI) commonly complicates cases of sepsis, with associated mortality rates as high as 70% [

5]. Evidence suggests that vasopressin may improve outcomes in septic patients at high risk for AKI, as defined by the RIFLE criteria, showing lower rates of progression to renal failure (20.8% vs. 39.6%) hence reducing the need for renal replacement therapy (17.0% vs. 37.7%) compared to norepinephrine [

22]. Additionally, meta-analyses indicate a lower incidence of AKI when vasopressin is combined with norepinephrine versus usage of norepinephrine alone [

23].

Diabetes Mellitus (DM) significantly increases the risk for both sepsis and subsequent limb amputation in septic patients. Diabetic individuals are more susceptible to infections and poor circulation, particularly when compounded by peripheral artery disease (PAD). A population-based study found that 0.8% of sepsis survivors required limb amputation, with DM and PAD identified as independent risk factors. These conditions contribute to poor microcirculation, which can lead to tissue damage, gangrene, and ultimately the need for amputation [

15].

Our analysis of this large cohort study identified several significant patterns related to vasopressor therapy and patient outcomes. Notably, the data revealed distinct differences between patients receiving vasopressor treatment and those who did not, particularly in key clinical outcomes. The vasopressor group demonstrated significantly higher adverse events, including increased in-hospital mortality and acute kidney injury. However, these findings are likely to reflect the greater severity of illness in this group rather than direct influence of vasopressor use. This interpretation is further supported by significant clinical parameters, including lower albumin levels and elevated creatinine levels throughout hospitalization, and prolonged hospital stays in the vasopressor group.

With relation to personalized medicine: demographic analysis revealed a notable gender disparity, with males representing a larger proportion of the vasopressor group. This observation aligns with findings from the Italian ICU cohort study, though their research paradoxically found increased ICU mortality risk among female patients with severe sepsis [

24]. The underlying mechanisms for these gender-based differences remain unclear. As noted by Angele et al., while clinical studies consistently demonstrate gender-based disparities in shock and sepsis outcomes, laboratory investigations have historically focused primarily on young male animals [

25]. Emerging evidence suggests potential protective effects of low dihydrotestosterone and/or high estradiol in septic shock, functioning through both direct receptor-mediated processes and indirect immunomodulatory pathways.

A particularly interesting finding emerged regarding age and amputation risk. Older age was associated with decreased risk of amputation, suggesting that more conservative management strategies may be employed in the elderly patients. Despite the greater illness severity in the vasopressor group, amputation rates remained similar between groups, indicating that vasopressor therapy may not be the primary cause of limb ischemia leading to amputation.

This finding is particularly relevant in the context of peripheral artery disease (PAD) and critical limb ischemia (CLI). Studies have shown that PAD alone increases amputation risk by14-fold, while the combination of both PAD and microvascular disease elevates this risk to 22.7-fold [

26]. Additionally, approximately 11.08% of PAD patients (without association to sepsis or septic shock) develop CLI annually [

27], highlighting the significance of underlying vascular disease in amputation risk. In our study, multivariate analysis demonstrated a 19.3-fold increased risk of amputations in patients with PAD.

The current guidelines for septic shock management (2023) continue to emphasize vasopressors' crucial role, with norepinephrine as the first-line agent, followed by vasopressin or epinephrine as second-line options. While these guidelines acknowledge theoretical risks of limb ischemia, they prioritize maintaining adequate organ perfusion [

28]. Our findings align with this approach, as vasopressor use was not significantly associated with an increased risk of amputation. Instead, other underlying patients’ characteristics, particularly peripheral vascular disease, emerged as more significant contributors to amputation risk.

These findings carry important clinical implications, indicating that concerns about vasopressor-induced limb ischemia should not deter clinicians from appropriate vasopressor use in septic shock management. This is especially relevant when following current guidelines, which emphasize careful monitoring of peripheral perfusion and administrating the lowest effective dose. Also, it stresses the need of personalized medicine, even in the settings of hyper-acute medicine, as it is in the case of patients suffering from septic shock.

5. Conclusions

In our study, we demonstrated that vasopressor use, whether noradrenaline or vasopressin, did not increase the risk of amputation in patients with septic shock. Furthermore, our findings reaffirmed that previously established risk factors – especially older age and peripheral vascular disease - remain fundamental risk factors for amputations. In light of our findings, vasopressor use in the ICU should be personalized according to the presence of pre-morbid risk factors for limbs’ ischemia.

6. Limitations

As a single-center, retrospective study, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations. Strict adherence to updated treatment guidelines of patients with septic shock, as are updated regularly, should remain the standard of care to ensure patient management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Sarit Avivi Bucktshin, Gad Segal and Reut Kssif Lerner; Methodology, Guy Dumanis and Matan Daniel; Software, Sarit Avivi Bucktshin, Gad Segal and Reut Kssif Lerner; Validation, Hadasa Cristo, Sarit Avivi Bucktshin and Gad Segal; Formal analysis, Guy Dumanis, Hadasa Cristo, Sarit Avivi Bucktshin, Matan Daniel, Gad Segal and Reut Kssif Lerner; Investigation, Hadasa Cristo; Resources, Reut Kssif Lerner; Data curation, Guy Dumanis, Matan Daniel and Reut Kssif Lerner; Writing – original draft, Guy Dumanis, Hadasa Cristo, Matan Daniel, Gad Segal and Reut Kssif Lerner; Writing – review & editing, Guy Dumanis, Sarit Avivi Bucktshin, Gad Segal and Reut Kssif Lerner. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017 Mar 1;43(3):304–77.

- Scheeren TWL, Bakker J, De Backer D, Annane D, Asfar P, Boerma EC, et al. Current use of vasopressors in septic shock. Ann Intensive Care. 2019 Dec 1;9(1).

- Shi R, Hamzaoui O, Vita N De, Monnet X, Teboul JL. Vasopressors in septic shock: which, when, and how much? Ann Transl Med [Internet]. 2020 Jun [cited 2024 Jul 11];8(12):794–794. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7333107/.

- Jozwiak M. Alternatives to norepinephrine in septic shock: Which agents and when? Journal of Intensive Medicine. 2022 Oct 1;2(4):223–32.

- García-Álvarez R, Arboleda-Salazar R. Vasopressin in Sepsis and Other Shock States: State of the Art. J Pers Med [Internet]. 2023 Nov 1 [cited 2024 Sep 18];13(11):1548. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC10672256/.

- Scheeren TWL, Bakker J, De Backer D, Annane D, Asfar P, Boerma EC, et al. Current use of vasopressors in septic shock. Ann Intensive Care [Internet]. 2019 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Sep 25];9(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30701448/.

- Potter EK, Hodgson L, Creagh-Brown B, Forni LG. MANIPULATING THE MICROCIRCULATION IN SEPSIS - THE IMPACT OF VASOACTIVE MEDICATIONS ON MICROCIRCULATORY BLOOD FLOW: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW. Shock [Internet]. 2019 Jul 1 [cited 2024 Sep 18];52(1):5–12. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/shockjournal/fulltext/2019/07000/manipulating_the_microcirculation_in_sepsis___the.2.aspx.

- Qura’an B, Omar HB, Al-Qaqa O, Abu-Jeyyab M, Hattab MG, Ruzieh M. Use of Inotropes and vasopressors in Septic Shock: When, Why, and How? JAP Academy Journal [Internet]. 2024 Mar 26 [cited 2024 Sep 15];2(1). Available from: https://journal.japacademy.org/index.php/Home/article/view/115.

- Hamzaoui O, Goury A, Teboul JL. The Eight Unanswered and Answered Questions about the Use of Vasopressors in Septic Shock. J Clin Med [Internet]. 2023 Jul 1 [cited 2024 Sep 15];12(14):4589. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC10380663/.

- Rationale Mechanism of action. 2011 [cited 2024 Sep 18]; Available from: . Available from: http://www.controlled-.

- Rohilla R, Chaudhary D, Agarwal A, Dhoat PS. Delayed Diagnosis of Vasopressor-induced Symmetrical Peripheral Gangrene in Septic Shock Patient. Journal of Antimicrobial Stewardship Practices and Infectious diseases. 2024 Mar 31;2(1):36–40.

- Attallah N, Hassan E, Jama AB, Jain S, Ellabban M, Gleitz R, et al. Management of Vasopressor-Induced Acute Limb Ischemia (VIALI) in Septic Shock. Cureus [Internet]. 2022 Dec 30 [cited 2024 Sep 15];14(12). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC9891393/.

- Limb Loss after Vasopressor Use | PSNet [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 15]. Available from: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/web-mm/limb-loss-after-vasopressor-use.

- Russo AT. Vasopressor-induced ischemia of bilateral feet in a previously healthy 34-year-old female. Foot & Ankle Surgery: Techniques, Reports & Cases. 2022 Jun 1;2(2):100183.

- Oh TK, Song IA. Incidence and associated risk factors for limb amputation among sepsis survivors in South Korea. J Anesth [Internet]. 2021 Feb 1 [cited 2024 Jul 11];35(1):51–8. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00540-020-02858-9.

- Newbury A, Harper KD, Trionfo A, Ramsey F V., Thoder JJ. Why Not Life and Limb? Vasopressor Use in Intensive Care Unit Patients the Cause of Acute Limb Ischemia. Hand (N Y) [Internet]. 2020 Mar 1 [cited 2024 Sep 15];15(2):177. Available from: https://pmc/articles/PMC7076614/.

- Burgdorff AM, Bucher M, Schumann J. Vasoplegia in patients with sepsis and septic shock: pathways and mechanisms. J Int Med Res [Internet]. 2018 Apr 1 [cited 2024 Sep 25];46(4):1303. Available from: https://pmc/articles/PMC6091823/.

- Jiang L, Sheng Y, Feng X, Wu J. The effects and safety of vasopressin receptor agonists in patients with septic shock: a meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Crit Care [Internet]. 2019 Mar 14 [cited 2024 Sep 25];23(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30871607/.

- Park C, Han C, Jang SK, Kim H, Kim S, Kang BH, et al. Development and Validation of a Machine Learning Model for Early Prediction of Delirium in Intensive Care Units Using Continuous Physiological Data: Retrospective Study. J Med Internet Res [Internet]. 2025 Apr 2 [cited 2025 Apr 4];27:e59520. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40173433/.

- LaRosa JM, Kudchadkar SR. Personalizing ICU liberation for critically Ill children: shaping the future of the ABCDEF bundle. Curr Opin Pediatr [Internet]. 2025 Apr 3 [cited 2025 Apr 4]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40172269/.

- Zhang W, Nguyen-Hoang N, Rivrud SCS, Zandbergen AF, Yan Y, Cox EGM, et al. Genetic association studies in critically ill patients: a systematic review. EBioMedicine [Internet]. 2025 Apr [cited 2025 Apr 4];114:105678. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40168842/.

- Gordon AC, Russell JA, Walley KR, Singer J, Ayers D, Storms MM, et al. The effects of vasopressin on acute kidney injury in septic shock. Intensive Care Med [Internet]. 2010 Jan 20 [cited 2024 Nov 10];36(1):83–91. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00134-009-1687-x.

- Nedel WL, Rech TH, Ribeiro RA, Pellegrini JAS, Moraes RB. Renal Outcomes of Vasopressin and Its Analogs in Distributive Shock: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Crit Care Med [Internet]. 2019 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Nov 10];47(1):E44–51. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal/fulltext/2019/01000/renal_outcomes_of_vasopressin_and_its_analogs_in.37.aspx.

- Sakr Y, Elia C, Mascia L, Barberis B, Cardellino S, Livigni S, et al. The influence of gender on the epidemiology of and outcome from severe sepsis. 2013 [cited 2025 Jan 15]. Available from: http://ccforum.com/content/17/2/R50.

- Angele MK, Pratschke S, Hubbard WJ, Chaudry IH. Gender differences in sepsis: cardiovascular and immunological aspects. Virulence [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2025 Jan 15];5(1):12–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24193307/.

- Behroozian A, Beckman JA. Microvascular Disease Increases Amputation in Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol [Internet]. 2020 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Jan 15];40(3):534–40. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32075418/.

- Nehler MR, Duval S, Diao L, Annex BH, Hiatt WR, Rogers K, et al. Epidemiology of peripheral arterial disease and critical limb ischemia in an insured national population. J Vasc Surg [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2025 Jan 15];60(3). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24820900/.

- Guarino M, Perna B, Cesaro AE, Maritati M, Spampinato MD, Contini C, et al. 2023 Update on Sepsis and Septic Shock in Adult Patients: Management in the Emergency Department. J Clin Med [Internet]. 2023 May 1 [cited 2025 Jan 15];12(9). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37176628/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).