1. Introduction

Considering the huge growth of social media platforms in recently, social media influencers (SMIs) are playing an increasingly vital role in how consumers discover, evaluate, and purchase of products and services [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This phenomenon has changed established marketing models by positioning SMIs as intermediaries between brands and consumers in the digital ecosystem [

5,

6]. Consequently, the influencer marketing industry grew to US

$21.1 billion in 2023, more than three times its size in 2019 [

7], underscoring its role in delivering positive marketing outcomes [

8].

As content creators with a huge following on social media platforms, SMIs offer brands a strategic opportunity to reach a wide audience [

9,

10]. A growing body of research on SMIs has emphasized the benefits of influencer marketing, including better brand awareness [

11], effective consumer engagement [

12], and higher sales conversions [

2]. In addition, SMIs influence consumer purchase intentions [

5,

13,

14]. In contrast, Djafarova and Bowes [

1] found that SMIs, even when perceived as trustworthy and relatable, do not drive purchases, as consumers prioritize the price and the product itself over SMI endorsement. Similarly, a different study [

15] showed that audience mistrust along with perceived commercialization, weakens their persuasive power and perceived authenticity SMIs. Hughes, Swaminathan, and Brooks [

16] concluded that SMIs had a minor-moderate effect on purchase intentions, with insignificant direct effect on sales. Most research has focused on SMIs impact of purchase intention. However, the evidence on whether purchase intention leads to positive consumer buying behavior is inconclusive and requires further research.

Based on the foregoing, we examine the effect of SMIs on purchase intention and actual buying behavior. We present evidence derived from a survey data to assess (1) the effect of SMIs on purchase intention, (2) how SMIs influence purchase behavior, (3) the role of trust in the process. We investigate the following research question: to what degree do SMIs drive consumer purchase intentions and purchase behavior, and what is the role of trust? In addressing the research question, we develop a conceptual model based on the literature and validate it with survey data. The study findings hold implications for brands seeking to optimize their influencer marketing strategies and contributes to the academic discourse in this rapidly developing research field.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. We first provide background information the theory of planned behavior. We then present the research model and hypotheses. Next, we describe the study methodology before we present the study’s findings. We reflect on and assess the implications of these findings before concluding after offering future research directions.

2. Background

2.1. Influencer Marketing: Prospects and Challenges

A symbiotic relationship exists between SMIs and social media, where SMIs utilize their substantial following to enhance their influence. At the same time, engaging and niche-oriented content created by SMIs enhances the user experience on social media [

17]. Thus, SMIs have become invaluable to contemporary marketing, providing brands with opportunities to connect with consumers [

18].

The literature stresses the strategic benefits SMIs offer organizations, including better customer engagement, improved brand recognition, and the ability to influence consumer perceptions positively [

19]. By fostering trust and building a network, SMIs function as credible third-party endorsers, enabling two-way interaction and strengthening brand loyalty [

2,

5]. We posit that partnerships with SMIs whose values align with a brand can enhance brand relatability and image, thereby driving consumer engagement. This synergy has increased sales as SMIs present products or services that resonate with their followers. Furthermore, the strategic engagement of SMIs extends a brand’s market reach by leveraging their follower networks to reach a broader demographic [

20]. The efficacy of SMIs transcends mere reach and visibility metrics. Their ability to shape consumer purchasing decisions may be attributable to their authenticity, relatability, and the trust they cultivate within their follower base. These characteristics have an advantage over traditional marketing, which often lacks the personal touch that SMIs possess [

8].

However, while influencer marketing offers several benefits, it also presents critical challenges. One significant issue is the variability in content quality across these platforms, which ranges from credible endorsements to misleading or false information [

21]. Furthermore, misinformation, unethical practices, and negative psychological impacts demand stronger regulatory frameworks and ethical standards for SMIs [

22,

23].

2.2. Theory of Planned Behavior, Purchase Intention and Buying Behavior

The theoretical underpinnings of the research reported in this paper is the theory of planned behavior(TPB), a well-established framework for studying the psychological factors of purchase intention and behavior [

24]. This theory provides a useful perspective on how SMIs affect consumer purchase intention and behavior [

25,

26]. TPB argues that there are three antecedents of purchase intention: attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Attitudes measure a consumer's summary evaluation toward a product (either positive or negative). For example, an SMIs endorsement of a product or service is likely to positively shape consumer attitudes towards purchase intention and actual purchase [

27,

28].

Subjective norms indicate the social pressure on a consumer to adhere to the preferences of significant others and social groups. This pressure is amplified by social media through witnessing positive online reactions towards products endorsed by SMIs [

29]. Perceived behavioral control is a consumer's perceived ability to purchase a product. Factors related to perceived behavioral control include accessibility, purchase cost and the complexity of purchase. If a product endorsed by an SMI is immediately available to a consumer and comes at a low perceived cost, the consumer will have an easier time translating intentions into purchase [

30].

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

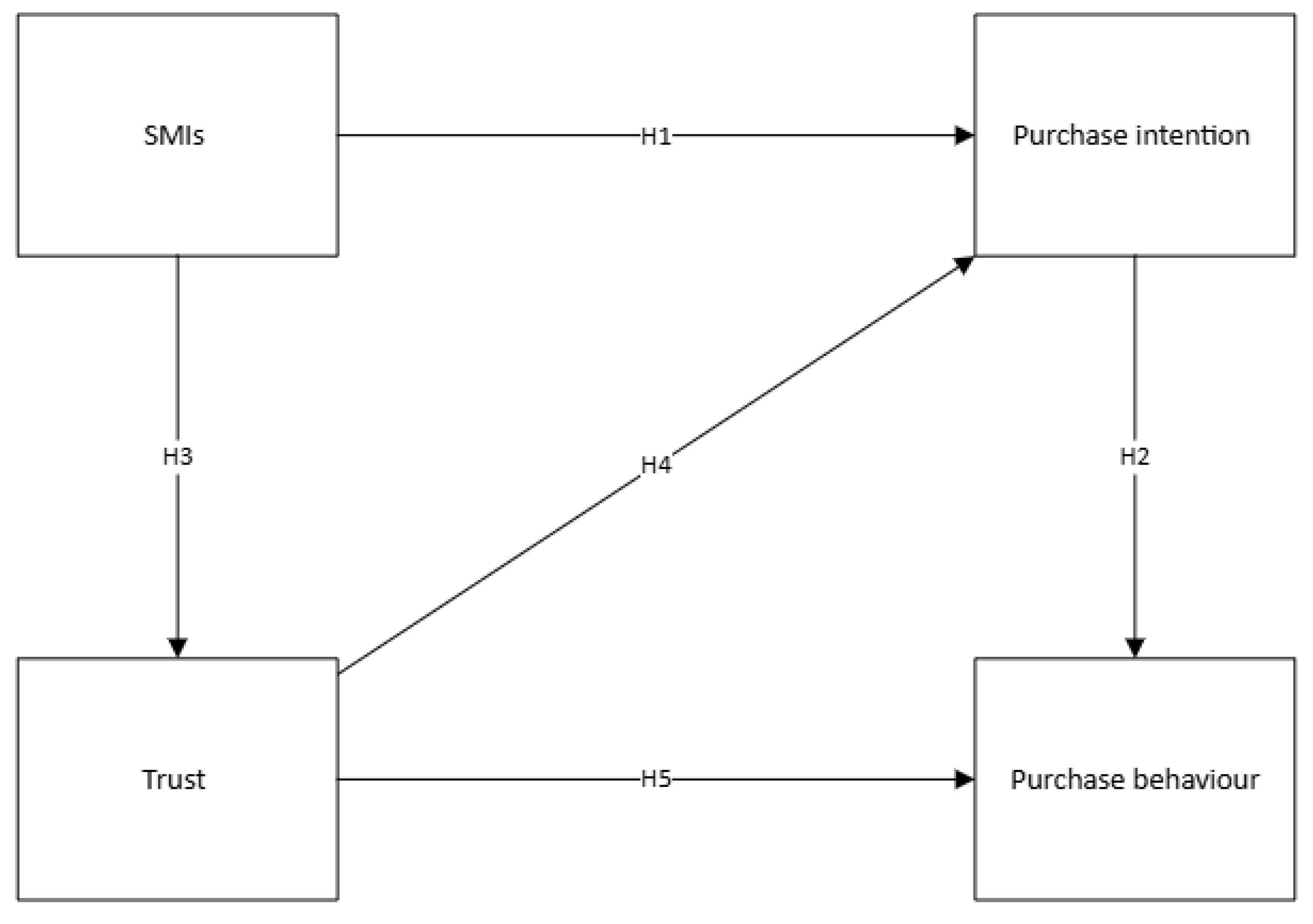

We propose a research model grounded in SMI and consumer purchasing behavior studies with four constructs: SMIs, trust in SMIs, purchase intention, and purchase behavior.

Figure 1 illustrates the research model and the hypothesized relationships.

3.1. Research Model

Prior studies indicate a correlation between SMIs and consumer purchase intentions [

13,

31,

32]. SMIs can enhance brand recognition and purchase likelihood [

15]. The “fear of missing out” (FOMO) has also been linked to consumers’ increased purchase intention toward products endorsed by SMIs [

33]. Based on this established body of research, we propose the following hypothesis:

SMIs’ impact increases through their variety of content, such as reviews, tutorials, and endorsements, thus creating emotional bonds between them and their followers [

34]. Several studies suggest that there is a relationship between SMIs and purchase behavior. For instance, it has been established that [

35], fashion influencers have a significant impact on customers’ buying decisions. Similarly, another study show that early teens were likely to be influenced by kid influencers’ product recommendations. Additionally, social identification had a direct impact on young people’s online advertising engagement and purchasing behavior [

30]. Finally, purchase intention has a positive impact on purchasing behavior, suggesting that if consumers have already demonstrated purchase intention, they are more likely to actualize their purchase intention into a purchase decision [

36] . Therefore:

3.2. The Role of Trust

In the context of SMIs, trust may be defined as readers’ confidence in an influencer’s credibility, dependability, and authenticity. Consumer’s trust in an SMI affects how they respond or interact with an SMI’s recommendations and what they write [

14]. For instance, [

37] found that trust in the SMI mediates the relationship between consumers and their buying intention. In turn, purchasing intentions and purchasing behavior are expressions of the influence of the SMIs’ trustworthiness and the strength of their recommendations. SMIs create trust through their relevant material related to a product or service [

38]. Having already established trust with their followers, these followers are more likely to listen to an influencer’s opinions [

39].

Some authors argue that consumers value highly the knowledge and expertise of SMIs in certain areas, making them trusted sources of information [

13]. Consumers can interact with SMIs using likes, comments, and sharing of content via social media [

2]. The interaction between consumers and SMIs has a two-way direction and allows consumers to ask for advice, ask questions, and share experiences [

2] and it allows consumers to gain SMI’s recommendations [

34]. This can increase consumers' trust in brand recognition and stimulate product sales [

40]. Kim and Kim [

41] point out that it is crucial to build trust when conducting influencer marketing strategies. The study by [

42] shows that informative SMI contents, perceived SMI trustworthiness, and perceived SMI attractiveness could positively affect consumers’ trust, which could be conducive to brand awareness and purchase intentions. Therefore, the following hypotheses are formed based on the literature:

H3: SMIs positively shape trust in the product or service promoted by the influencer.

H4: Perceived trust in SMIs positively affects consumers’ purchase intentions.

H5: Perceived trust in SMIs positively influences actual purchase behavior.

4. Materials and Methods

We employed a positivist quantitative research strategy to validate the proposed research model and its associated hypotheses. The quantitative approach is well suited to the research problem in this study to systematically collect and analyse empirical data to explore the relationships among SMIs, purchase intention, and behavior. Furthermore, this approach is appropriate in this study as it prioritizes objectivity, measurability, and empirical validation [

43].

4.1. Data Collection

We utilized a cross-sectional survey because it allowed us to gain a snapshot of the views of consumers on purchase intention and behavior. It also facilitated the identification of relationships between SMIs and purchase intention and behaviors without requiring longitudinal data [

44]. Cross-sectional surveys are commonly used in business, marketing and other disciplines because they are easy to conduct, relatively inexpensive and capable of providing timely insights [

45].

A principal element of surveys is the design of an appropriate questionnaire [

46]. Accordingly, we designed a questionnaire from the literature on SMI, trust purchase intention, and behavior.

Table 1 shows the operationalization and definitions of these constructs and their theoretical bases. The survey instrument consisted of two parts. The first was used to collect demographic data, which included age, gender, education, employment status, and income. The second collected data on social media interactions between individuals and SMIs, trust purchase intentions and behaviors based on SMI recommendations. Respondents responded to the questions on a 7-point Likert scale.

We used convenience sampling method which is a non-probabilistic sampling method where the participants of the study are selected based on their availability to participate and willingness to be involved in the study. Convenience sampling was adopted in this study due to its practicality, cost-effectiveness, and efficient access to the population of interest [

54]. Despite its advantages of being cost and time-saving and easy to implement, it is important to acknowledge the drawback involved in convenience sampling, which is the risk of sampling bias. The sample obtained may not be as representative of the population of social media users hence affecting the generalizability of the results. To reduce the possibility of this type of bias, efforts were made to include as diverse a sample as possible by seeking the participation of diverse demographic groups in the study by encouraging people of different ages, gender, level of education and income to complete the survey. Despite these limitations of convenience sampling, we considered it appropriate in this case because the study is exploratory in nature [

55] and allowed us to gather sufficient data to test the research model and hypotheses.

We distributed the survey link throughout different social media platforms, particularly, Instagram and Facebook. Data collection took place over a period of two months (March–May 2024), totaling 232 responses.

4.2. Data Analysis

We applied Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), a variance-based statistical modelling technique, to validate the proposed research model and to test the hypotheses owing to the possibility of latent variables in the measurement model [

56]. The flexibility of PLS-SEM in handling non-normal distribution data and efficient handling of small-medium sample sizes also makes this technique suitable for this research. PLS-SEM also allowed the testing of the hypotheses simultaneously, which strengthened the rigor of the research analysis [

57]. We opted for the choice of PLS-SEM because of its robustness in handling complex structural models with multiple latent variables and its more flexible requirement for sample size than covariance-based SEM. Furthermore, this technique facilitated the assessment of relationships among latent constructs and estimates of path coefficients to indicate the strength and direction of the relationships among constructs in our model [

58,

59].

5. Results

The section presents the study findings. Firstly, descriptive analysis of the study sample is provided. Subsequently, the validity and reliability of the measurement model are evaluated. Finally, the structural model is examined, and the relationships hypotheses are tested.

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

A summary of the study sample and descriptive statistics is depicted in

Table 2. The average age of the sample is 34, with a gender distribution of 48% male and 52% female. A significant portion of the sample (34%) is aged between 28 and 37, while those in the 18-27 age group account for 31%. Participants aged 38-47 represent 24%, with smaller percentages from the 48-57 (9%) and 58-67 (2%) age groups. Most participants are well-educated, with 52% holding a university degree, 29% pursuing postgraduate studies, 11% with further education qualifications (A-levels or BTECs), 5% having completed secondary education, and 3% with only primary education. The survey also indicates considerable social media engagement among participants, who, on average, use four social media platforms and follow approximately nine SMIs. Half of the sample are full-time employees, and part-time workers making up 15%. Students comprises nearly a quarter of the sample (24%). The remaining respondents are either unemployed (2.6%) or self-employed (7.8%). Income levels range from £10,000 to above £60,000. Over 60% of respondents earn below £20,000, while a smaller proportion (4.3%) earn above £60,000.

5.2. Measurement Model Validity Assessment

Convergent and discriminant validity analysis were conducted to evaluate the validity of the measurement model. Convergent validity assesses how well the indicators measure the underlying constructs [

60]. The average variance extracted (AVE) values for all the indicators pertaining to each construct were computed. Subsequently, composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were examined to evaluate internal consistency and reliability of the measurement model.

Table 3 summarizes the measurement model assessment results. The results show that the study constructs have a high level of reliability. The Cronbach’s alpha of all the constructs falls within the acceptable range from 0.746 to 0.899. The internal consistency reliability was satisfactory since all the CR values were above 0.7 [

61].

The AVE values for all the constructs exceed the recommended threshold value of 0.5 and range from 0.692 to 0.868. This implies that each construct accounts for a significant proportion of the variance in its respective indicators, thereby demonstrating strong convergent validity [

62]. Established criteria requires that a latent variable should explain at least 50% of the variance in its associated indicators to ensure adequate measurement reliability. The AVE values confirm that all constructs meet this condition, with each explaining over half of the variance. Therefore, the results offer robust evidence for the convergent validity of the constructs, affirming their reliability and accuracy in evaluating the theoretical dimensions [

61].

The Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations are a robust measure of discriminant validity to ensure that the study constructs in the measurement model are distinct. As shown in

Table 4, our analysis show strong evidence of discriminant validity, as all HTMT vales fall below the threshold of 0.85 [

63]. We observed ratios ranging from a minimum of 0.114 (between trust and SMIs) to a maximum of 0.725 (between purchase intention and actual purchase), further corroborating the discriminant validity of the construct.

5.3. Measurement Model Reliability Assessment

Internal consistency reliability is fundamental for robust PLS-SEM analyses. Evaluating the measurement model through an estimation of indicator reliability, is essential to establish the validity and reliability of the constructs under investigation before structural model analysis. Indicator reliability, computed through outer loadings, are the proportion of variance explained by its corresponding latent construct. Following conventional thresholds suggested by Hair

et al [

61], loadings over 0.708 are considered acceptable, as they indicate that the constructs account for at least of the indicator’s variance. As presented in

Table 5, most indicators had had loadings exceeding this threshold. However, a few indicators had loadings from 0.4 to 0.7, which although not optimal, were retained. This is consistent with recommendations by Hair

et al [

61], who maintain that keeping such indicators can improve model fit and the robustness of subsequent structural analysis, provided the constructs have adequate internal consistency reliability.

5.4. Structural Model Assessment and Hypothesis Testing

The results of the structural model analysis, including the standardized path coefficients, significance levels, and goodness-of-fit indices, are depicted in

Table 6. The results clarify the predictive validity and explanatory strength of the hypothesized relationships in the model.

Bootstrapping analysis revealed mixed support for the hypothesized paths. H1, which predicts that SMIs positively influence consumers’ purchase intention (β = 0.722, t = 8.434, p < 0.05), was supported. In contrast, H2 which proposes that SMIs have a positive effect on actual purchases, was not supported, as evidence by a non-significant path coefficient (β = 0.112; T-value = 1.233; p > 0.05).

H3, which asserts that SMIs significantly enhance consumer trust, received robust support (β = 0.819, t = 23.986, p < 0.05), was strongly supported (β = -0.971, t = 7.108, p < 0.05). However, H4, which proposes that perceived trust in SMIs positively affects consumers’ purchase intentions, was not supported (β = 0.141; T-value = 0.849; p > 0.05). Surprisingly, H5, which hypothesized that SMI recommendations influence actual purchases through trust, was not supported (β = -0.971; T-value = 7.108; p < 0.05). Finally, the non-significant path coefficient for Hypothesis 6 (H6) (β = -0.125; T-value = 0.572; p > 0.05), implying that trust does not fully mediate this relationship.

Table 7 shows the r-squared values for the endogenous variables in the structural model. The r-square metric quantifies the proportion of the variance in any one of the endogenous variables that can be explained by the exogenous variable. The variable PI exhibits an r-squared value of 0.83, indicating a strong predictive relationship. This suggests that 83% of the variance in consumer purchase intentions can attributed to the impact of SMIs. In contrast, the variable AP, has significantly lower power (0.021), implying a weak explanatory relationship between purchase intention and actual purchases. Specifically, only 2.1% of the variance in purchase behavior is accounted for purchase intention, while the remaining 97.1% is influenced by factors beyond the scope of this study. Finally, the variable trust has an r-squared value of 0.67, indication that SMIs explain 67% of the observed variance in consumer trust.

6. Discussion

The analysis of the survey responses found some effect of SMIs on purchase intention and actual purchasing behavior, thus extending the extant literature that has principally focused the former. The first contribution of this study is the statistically significant positive relationship established between trust and purchase intention, reinforcing the role of trust in driving consumer the decision-making processes in influence digital marketing. This finding corroborates prior work [

1,

15], which underscores trust as a critical driver in consumer decision making in influencer marketing.

The second contribution of this research is that while evidence supports the positive effect of SMIs on purchase intension, they have negligible influence on purchasing behavior, challenging the established assumption that influencer marketing directly translates into actual consumer purchases. This discrepancy might be due to several moderating factors. For example, Afzal et al [

64] argues that brand credibility is a critical moderating factor in transforming purchase intention into actual buying behavior. While our study identifies and gap between purchase intention and buying behavior, this divergence could also stem from variables beyond the scope the current research including financial constraints, the availability of substitute products, post-intention shifts in consumer preferences, and contextual factors like product availability, pricing and promotions. These findings contrast with those of Indiani and Fahik [

36], who reported a positive association between purchase intention and buying behavior, underscoring the complexity of this relationship. Remarkably, our analysis revealed an unexpected negative association between trust in SMIs and purchase intention (β = –0.971, p < 0.05), suggesting that the dynamic of trust and its impact on consumer decision making are more complex than previously assumed. Furthermore, we found that while SMIs influence cultivate consumer trust, which leads to positive purchase intentions, this does not lead to actual purchases.

The empirical findings have some implications. The first implication concerns how marketers and businesses in leveraging the influence of SMIs for effective brand promotion and consumer engagement. The findings indicate that it is essential to collaborate with SMIs whose values and target audiences closely align with those of the brand. The authenticity and transparency of the influencer marketing campaign are crucial for building consumer trust and fostering long-term brand loyalty. The positive effect of SMIs on purchase intention suggests the importance of selecting SMIs carefully and strategically collaborating with them. It is important that marketers select credible and relatable SMIs for their endorsements [

12,

65]. Secondly, the study identifies a gap between purchase intention and purchasing behavior. This highlights that factors beyond purchase intention, such as financial constraints and availability of alternative options, may be considered by consumers when making the purchasing decision. For example, consumers with high purchase intention due to SMI recommendations may not make the purchase due to a lack of financial resources. Additionally, external factors such as pricing strategies and promotional offers from competitors may also be considered by consumers when making the purchasing decision. Therefore, it is important that marketers break the intentions-behavior gap by eliminating purchasing barriers and establishing clear pathways for consumers to act on their intentions [

66].

Even though we found an unexpected negative relationship between trust in SMIs and purchase intention (β = -0.971, p < 0.05), most of the literature acknowledges the importance of trust in successful influencer marketing [

37,

42]. This result suggests that there is more complex relationship between trust and purchase intention. Although trust may not always be sufficient to drive purchase intentions, it plays an essential role in successful relationships with influencers. Thus, brands are encouraged to strategically collaborate with SMIs who have cultivated trust and credibility with their follower community. By aligning with influencers who have established trust, brands can leverage the influencer's authenticity and credibility, and enhance the overall effectiveness of their marketing efforts, which can in turn lead to stronger consumer engagement.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study provides valuable insights into the impact of SMIs on consumer purchase intention and buying behavior, there are limitations that must be acknowledged. Firstly, the use of a cross-sectional study design and non-probability sampling constraints the generalizability of the findings. These methodological issues underscore the need for future research to employ longitudinal and experimental designs, alongside probability sampling techniques to strengthen to enhance the external validity of the findings.

Our findings underscore the significance of accounting for additional moderating and mediating variables that may influence the link between purchase intention and actual buying behavior. Future research could incorporate both micro-level contextual variables, such as economic conditions and cultural differences, and micro-level factors like consumer risk aversion and brand loyalty. Such studies could produce deeper understanding of the determinants driving consumer choices. By elucidating these mechanisms, digital marketer could refine their strategies to bridge the gap between purchase intention and actual purchase behavior.

This study focuses on purchase intention; however, subsequent study could explore the mechanisms through which purchase intentions are converted into actual purchases. Future research may, for example, examine potential moderators, such as price sensitivity, perceived value of products, and convenience, which may hinder or facilitate this process [

5]. Additionally, examining mediating mechanisms, such as perceived authenticity of influencer endorsements and peer social validation, to help explain how trust in SMIs translates into consumer purchases.

Future studies should investigate other characteristics of successful SMIs such as their credibility, expertise, and authenticity, to deepen into effective influencer marketing strategies. In addition, comparative studies on how different types of influencers (e.g., micro-influencers versus celebrities) influence different types of target populations of different social media platforms and cultural settings are warranted for tailored marketing strategies [

23].

The unexpected findings of the study (i.e., the negative relationship between trust in SMIs and purchase intention) warrants further investigation. Future research should examine potential moderating variables that could explains the underlying mechanisms of this relationship, thereby producing a more nuanced understanding of trust’s role in influencer marketing. Furthermore, exploring the concurrent influence of external factors, such as product availability, pricing strategy and psychological cues, like impulse buying tendency, perceived risk in consumer decision journey.

7. Conclusions

We explored the impact of SMIs on consumers’ decision-making process, focusing on examining the role of trust. The findings demonstrate a positive influence of SMIs on consumers’ purchase intentions emphasizing the role of SMIs in molding consumers’ perception and enhancing engagement. However, SMIs and purchase intentions comprising a significant gap to purchase behavior findings indicate that SMIs will not delivery conversion despite SMIs’ impact on purchase intentions unless moderating influences are controlled. In producing empirical insights pertaining to the dynamics of influencers, trust, and purchase intent as well as influencers and purchase behavior, we contribute to the literature. For marketers, these findings yield useful insights on strategic SMI selection, influencers–brand collaboration, and targeted action to reduce the intention–behavior gap. Further research should explicitly explore moderation influences, such as consumers’ individual differences, influences of others’ social validation, and contextual influences or circumstances leading to the purchase conversion. By enriching insights in this field, this research makes scholarly and practical contribution to advance the understanding of influencer marketing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.B.A., F.F. and L.M.; methodology, G.B.A.; formal analysis, G.B.A.; investigation, G.B.A., F.F. and L.M.; resources, G.B.A., F.F. and L.M.; data curation, GBA.; writing—original draft preparation, GBA.; writing—review and editing, F.F. and L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

Available on request

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest.

References

- Djafarova, E.; Bowes, T. ‘Instagram Made Me Buy It’: Generation Z Impulse Purchases in Fashion Industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102345. [CrossRef]

- Enke, N.; Borchers, N.S. Social Media Influencers in Strategic Communication: A Conceptual Framework for Strategic Social Media Influencer Communication. In Social Media Influencers in Strategic Communication; Routledge, 2021 ISBN 978-1-00-318128-6.

- Paul, J.; Jagani, K.; Yadav, N. “How I Think, Who I Am”—Role of Social Media Influencers (SMIs) as Change Agents. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 1900–1916. [CrossRef]

- Rachmad, Y.E. The Future of Influencer Marketing: Evolution of Consumer Behavior in the Digital World; PT. Sonpedia Publishing Indonesia, 2024; ISBN 9786238634583.

- Ki, C.-W. ‘Chloe’; Kim, Y.-K. The Mechanism by Which Social Media Influencers Persuade Consumers: The Role of Consumers’ Desire to Mimic. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 905–922. [CrossRef]

- van Driel, L.; Dumitrica, D. Selling Brands While Staying “Authentic”: The Professionalization of Instagram Influencers. Convergence 2021, 27, 66–84. [CrossRef]

- Statista Global Influencer Market Size 2024 Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1092819/global-influencer-market-size/ (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Lee, J.; Walter, N.; Hayes, J.L.; Golan, G.J. Do Influencers Influence? A Meta-Analytic Comparison of Celebrities and Social Media Influencers Effects. Soc. Media Soc. 2024, 10, 20563051241269269. [CrossRef]

- Khamis, S.; Ang, L.; Welling, R. Self-Branding, ‘Micro-Celebrity’ and the Rise of Social Media Influencers. Celebr. Stud. 2017.

- Leung, F.F.; Gu, F.F.; Palmatier, R.W. Online Influencer Marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 226–251. [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, I.; Namkoisse, E. The Role of Influencer Marketing in Building Authentic Brand Relationships Online. J. Digit. Mark. Commun. 2023, 3, 81–90. [CrossRef]

- Ao, L.; Bansal, R.; Pruthi, N.; Khaskheli, M.B. Impact of Social Media Influencers on Customer Engagement and Purchase Intention: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2744. [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, B.; Iranmanesh, M.; Nilashi, M.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Asadi, S.; Khoshkam, M. Determinants of Followers’ Purchase Intentions toward Brands Endorsed by Social Media Influencers: Findings from PLS and fsQCA. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 888–914. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khan, Z.; Nabi, M.K. “I Think Exactly the Same”—Trust in SMIs and Online Purchase Intention: A Moderation Mediation Analysis Using PLS-SEM. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2024, 21, 311–330. [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer Marketing: How Message Value and Credibility Affect Consumer Trust of Branded Content on Social Media. J. Interact. Advert. 2019.

- Hughes, C.; Swaminathan, V.; Brooks, G. Driving Brand Engagement Through Online Social Influencers: An Empirical Investigation of Sponsored Blogging Campaigns. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 78–96. [CrossRef]

- Haenlein, M.; Anadol, E.; Farnsworth, T.; Hugo, H.; Hunichen, J.; Welte, D. Navigating the New Era of Influencer Marketing: How to Be Successful on Instagram, TikTok, & Co. Calif. Manage. Rev. 2020, 63, 5–25. [CrossRef]

- Vrontis, D.; Makrides, A.; Christofi, M.; Thrassou, A. Social Media Influencer Marketing: A Systematic Review, Integrative Framework and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 617–644. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Ismagilova, E.; Hughes, D.L.; Carlson, J.; Filieri, R.; Jacobson, J.; Jain, V.; Karjaluoto, H.; Kefi, H.; Krishen, A.S.; et al. Setting the Future of Digital and Social Media Marketing Research: Perspectives and Research Propositions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 59, 102168. [CrossRef]

- Syed, T.A.; Mehmood, F.; Qaiser, T. Brand–SMI Collaboration in Influencer Marketing Campaigns: A Transaction Cost Economics Perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 192, 122580. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kelly, G.; Janssen, M.; Rana, N.P.; Slade, E.L.; Clement, M. Social Media: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018, 20, 419–423. [CrossRef]

- Abidin, C. Yes Homo: Gay Influencers, Homonormativity, and Queerbaiting on YouTube. Contin. J. Media Cult. Stud. 2019, 33, 614–629.

- Singh, H.; Cascini, G.; McComb, C. Influencers in Design Teams: A Computational Framework to Study Their Impact on Idea Generation. AI EDAM 2021, 35, 332–352.

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, L.; Lindh, C. Sustainably Sustaining (Online) Fashion Consumption: Using Influencers to Promote Sustainable (Un)Planned Behavior in Europe’s Millennials. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, N.PAG-N.PAG.

- Tiwari, A.; Kumar, A.; Kant, R.; Jaiswal, D. Impact of Fashion Influencers on Consumers’ Purchase Intentions: Theory of Planned Behavior and Mediation of Attitude. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2023, 28, 209–225. [CrossRef]

- Lim, X.J.; Radzol, A.R. bt M.; Cheah, J.-H.; Wong, M.W. The Impact of Social Media Influencers on Purchase Intention and the Mediation Effect of Customer Attitude. Asian J. Bus. Res. 2017, 7, 19–36.

- Sánchez-Fernández, R.; Jiménez-Castillo, D. How Social Media Influencers Affect Behavioral Intentions towards Recommended Brands: The Role of Emotional Attachment and Information Value. J. Mark. Manag. 2021, 37, 1123–1147. [CrossRef]

- Pham, A.D.; Dao ,Trang T. T.; Pham ,Phuong M.; Pham ,Yen H.; Nguyen ,Huong T.; and Pham, L.N. How Does Conformity Shape Influencer Marketing in the Food and Beverage Industry? A Case Study in Vietnam. J. Internet Commer. 2024, 23, 172–203. [CrossRef]

- Croes, E.; Bartels, J. Young Adults’ Motivations for Following Social Influencers and Their Relationship to Identification and Buying Behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 124, 106910. [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A.A. Investigating the Impact of Social Media Advertising Features on Customer Purchase Intention. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 42, 65–77. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zheng, X. The Persuasive Power of Social Media Influencers in Brand Credibility and Purchase Intention. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.C.T.; Lee, Y. “I Want to Be as Trendy as Influencers” – How “Fear of Missing out” Leads to Buying Intention for Products Endorsed by Social Media Influencers. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 16, 346–364. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, G.; Drenten, J.; Piskorski, M.J. Influencer Celebrification: How Social Media Influencers Acquire Celebrity Capital. J. Advert. 2021, 50, 528–547. [CrossRef]

- Javed, S.; Rashidin, Md.S.; Xiao, Y. Investigating the Impact of Digital Influencers on Consumer Decision-Making and Content Outreach: Using Dual AISAS Model. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2022, 35, 1183–1210. [CrossRef]

- Indiani, N.L.P.; Fahik, G.A. Conversion of Online Purchase Intention into Actual Purchase: The Moderating Role of Transaction Security and Convenience. Bus. Theory Pract. 2020, 21, 18–29. [CrossRef]

- Ismagilova, E.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Slade, E.; Williams, M. Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM) in the Marketing Context: A State of the Art Analysis and Future Directions; Springer International Publishing, 2017;

- Nafees, L.; Cook, C.M.; Nikolov, A.N.; Stoddard, J.E. Can Social Media Influencer (SMI) Power Influence Consumer Brand Attitudes? The Mediating Role of Perceived SMI Credibility. Digit. Bus. 2021, 1, 100008. [CrossRef]

- Balaban, D.C.; Mucundorfeanu, M.; Naderer, B. The Role of Trustworthiness in Social Media Influencer Advertising: Investigating Users’ Appreciation of Advertising Transparency and Its Effects. Communications 2022, 47, 395–421. [CrossRef]

- Mammadli, G. The Role Of Brand Trust in The Impact Of Social Media Influencers On Purchase Intention 2021.

- Kim, D.Y.; Kim, H.-Y. Trust Me, Trust Me Not: A Nuanced View of Influencer Marketing on Social Media. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 223–232. [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Tan, S.-S.; Chen, X. Investigating Consumer Engagement with Influencer- vs. Brand-Promoted Ads: The Roles of Source and Disclosure. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 169–186.

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; 6th ed. edition.; Sage Publications, Inc: Los Angeles London New Delhi Singapore Washington DC Melbourne, 2022; ISBN 978-1-07-181794-0.

- Maier, C.; Thatcher, J.B.; Grover, V.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Cross-Sectional Research: A Critical Perspective, Use Cases, and Recommendations for IS Research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 70, 102625. [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.; Bryman, A.; Harley, B. Business Research Methods; 6th Edition.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2022; ISBN 978-0-19-886944-3.

- Clark, T.; Foster, L.; Bryman, A.; Sloan, L. Bryman’s Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press, 2021; ISBN 978-0-19-879605-3.

- Hudders, L.; Jans, S.D.; Veirman, M.D. The Commercialization of Social Media Stars: A Literature Review and Conceptual Framework on the Strategic Use of Social Media Influencers. In Social Media Influencers in Strategic Communication; Routledge, 2021 ISBN 978-1-00-318128-6.

- Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Changing Behavior Suing the Theory of Planned Behavior. In The Handbook of Behavior Change; Hagger, M.S., Cameron, L.D., Hamilton, K., Hankonen, N., Lintunen, T., Eds.; Cambridge University Press, 2020 ISBN 978-1-108-75011-0.

- Chetioui, Y.; Benlafqih, H.; Lebdaoui, H. How Fashion Influencers Contribute to Consumers’ Purchase Intention. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 24, 361–380. [CrossRef]

- Peña-García, N.; Gil-Saura, I.; Rodríguez-Orejuela, A.; Siqueira-Junior, J.R. Purchase Intention and Purchase Behavior Online: A Cross-Cultural Approach. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04284. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, N.; Gupta, G.; Vamsi, V.; Bose, I. On the Platform but Will They Buy? Predicting Customers’ Purchase Behavior Using Deep Learning. Decis. Support Syst. 2021, 149, 113622. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.L.; Novak, T.P.; Peralta, M. Building Consumer Trust Online. Commun. ACM 1999, 42, 80–85. [CrossRef]

- Khamitov, M.; Rajavi, K.; Huang, D.-W.; Hong, Y. Consumer Trust: Meta-Analysis of 50 Years of Empirical Research. J. Consum. Res. 2024, 51, 7–18. [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2015, 5, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. The Inconvenient Truth About Convenience and Purposive Samples. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2021, 43, 86–88. [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Rigdon, E.E.; Straub, D. Editor’s Comments: An Update and Extension to SEM Guidelines for Administrative and Social Science Research. MIS Q. 2011, 35, iii–xiv. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publishing, 2022; ISBN 978-1-5443-9640-8.

- Benitez, J.; Henseler, J.; Castillo, A.; Schuberth, F. How to Perform and Report an Impactful Analysis Using Partial Least Squares: Guidelines for Confirmatory and Explanatory IS Research. Inf. Manage. 2020, 57, 103168. [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.-M.; Cheah, J.-H.; Gholamzade, R.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM’s Most Wanted Guidance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 35, 321–346. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; Lau, R.S.; Wang, L.C. Reporting Reliability, Convergent and Discriminant Validity with Structural Equation Modeling: A Review and Best-Practice Recommendations. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [CrossRef]

- Afzal, B.; Wen, X.; Nazir, A.; Junaid, D.; Olarte Silva, L.J. Analyzing the Impact of Social Media Influencers on Consumer Shopping Behavior: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6079. [CrossRef]

- Ki, C.-W.‘.; Cuevas, L.M.; Chong, S.M.; Lim, H. Influencer Marketing: Social Media Influencers as Human Brands Attaching to Followers and Yielding Positive Marketing Results by Fulfilling Needs. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55.

- Ki, C.-W. (Chloe); Chow, T.C.; Li, C. Bridging the Trust Gap in Influencer Marketing: Ways to Sustain Consumers’ Trust and Assuage Their Distrust in the Social Media Influencer Landscape. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 2023, 39, 3445–3460. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).