Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

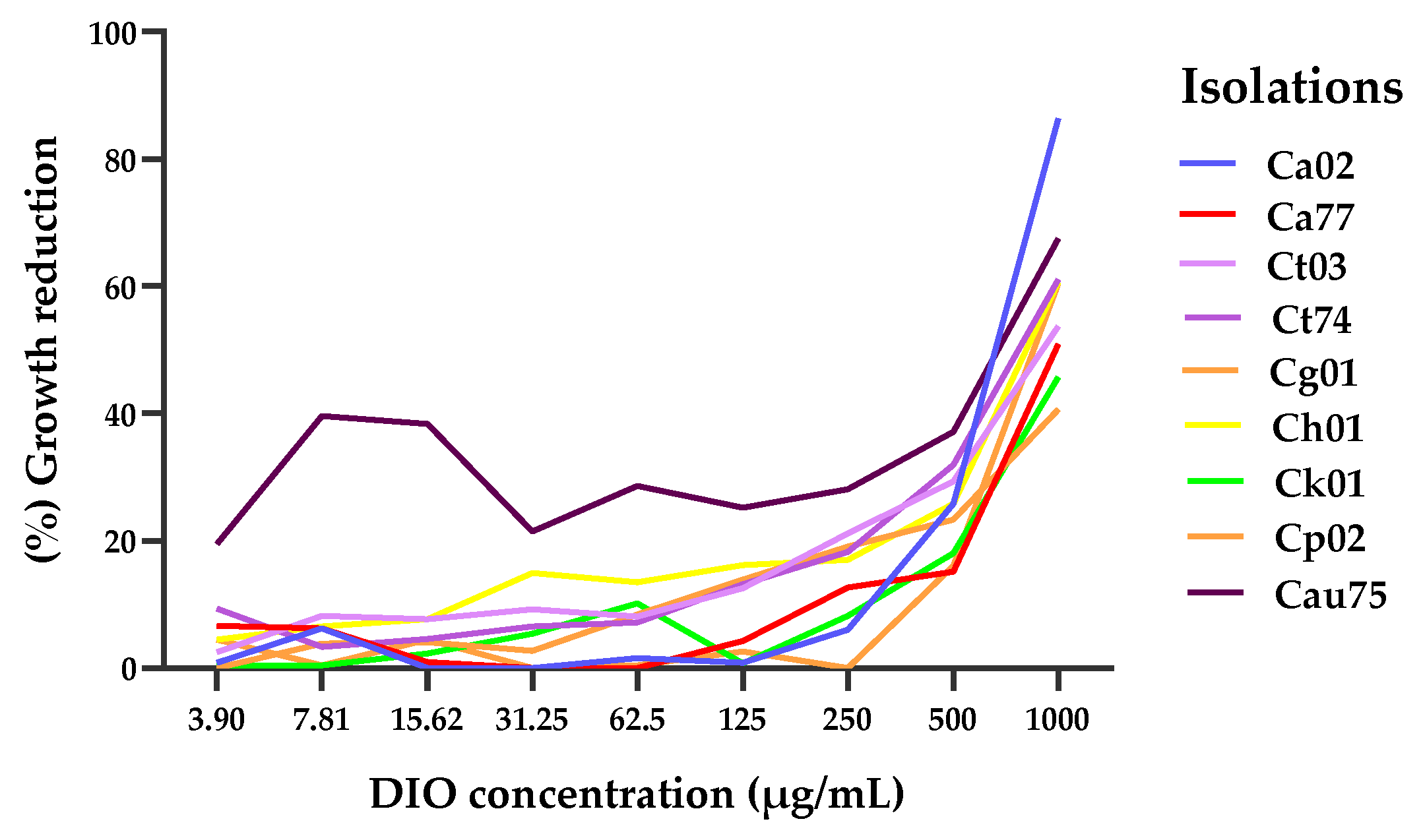

2.1. Susceptibility Testing

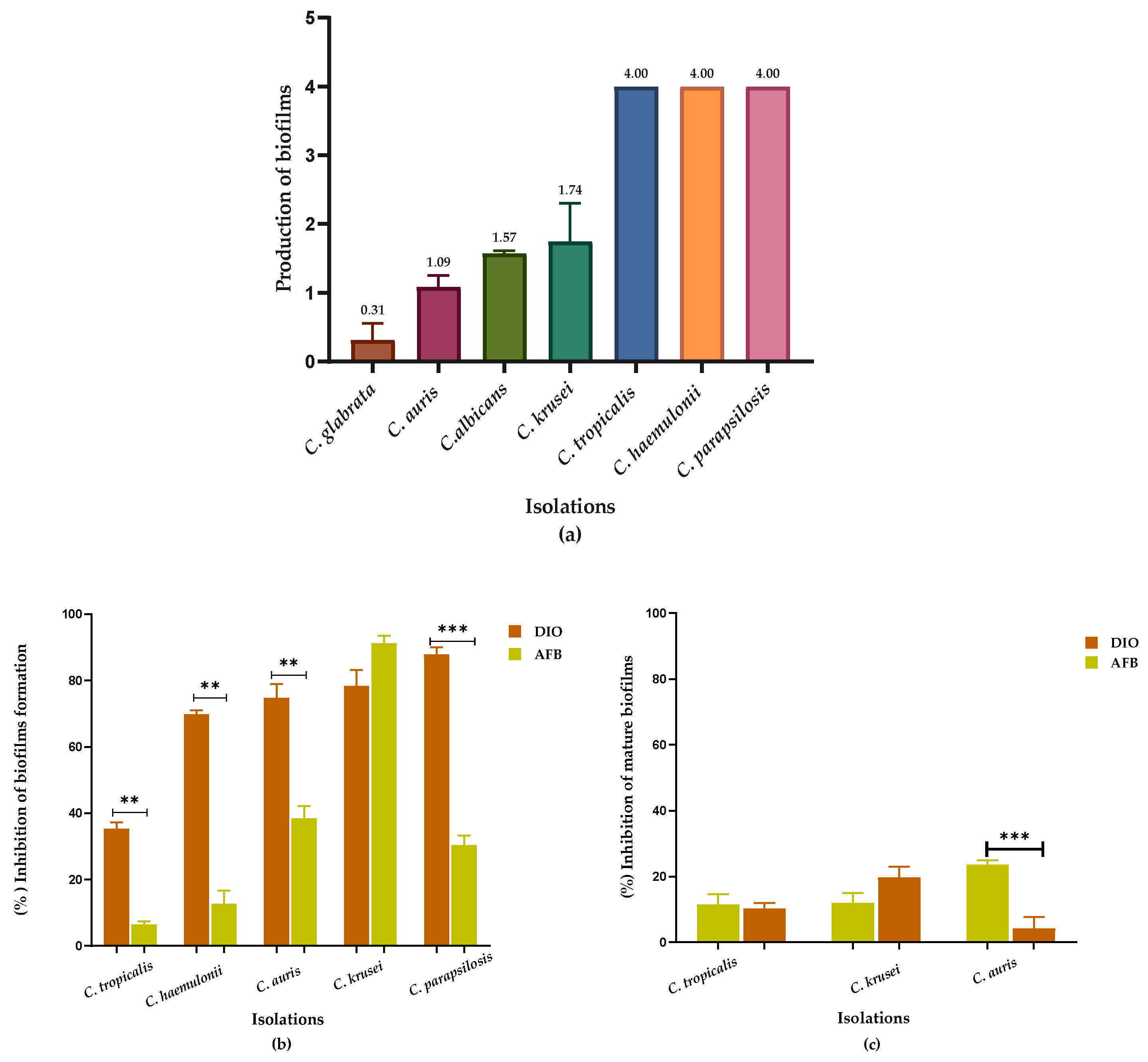

2.2. Biofilm Reduction

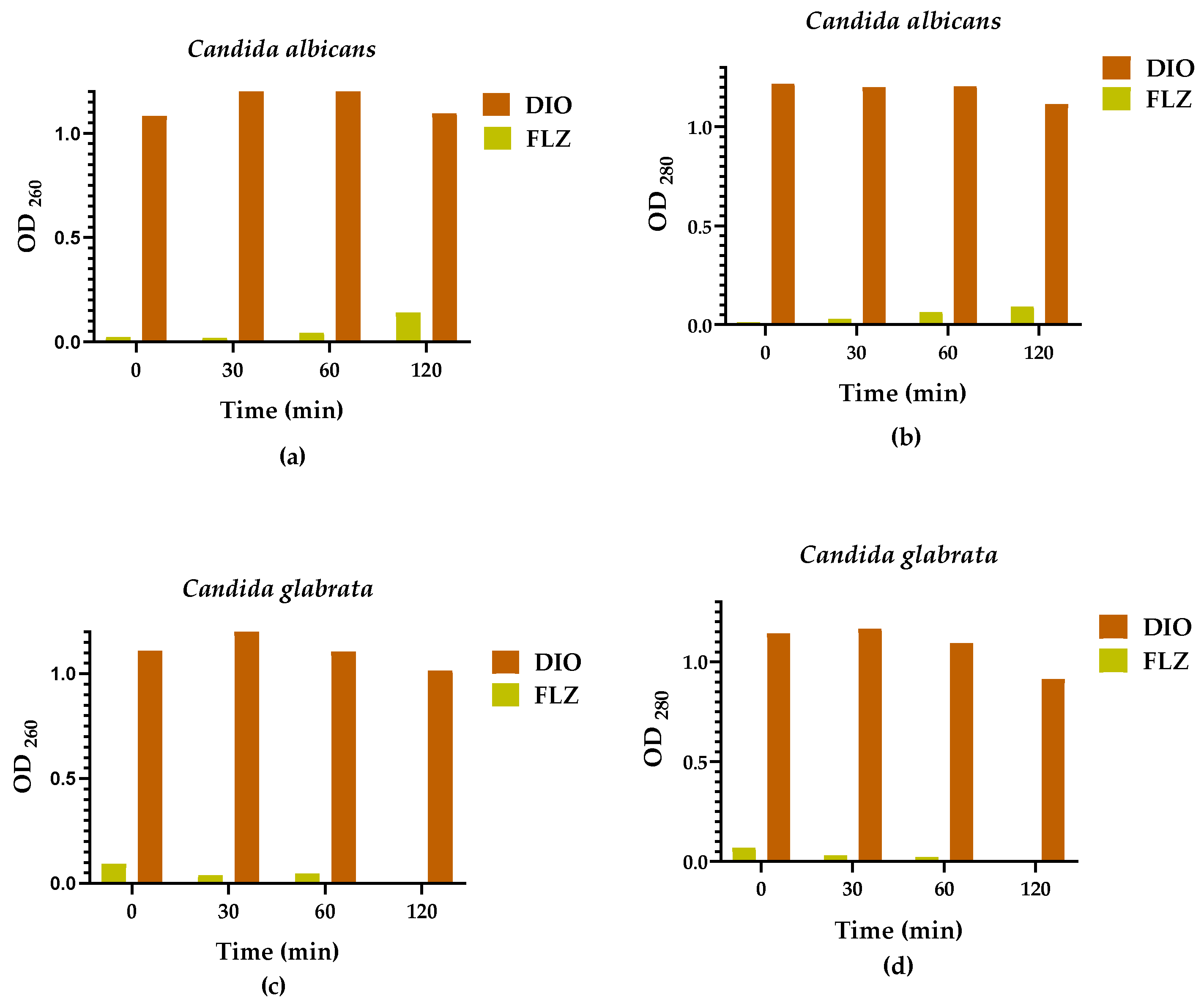

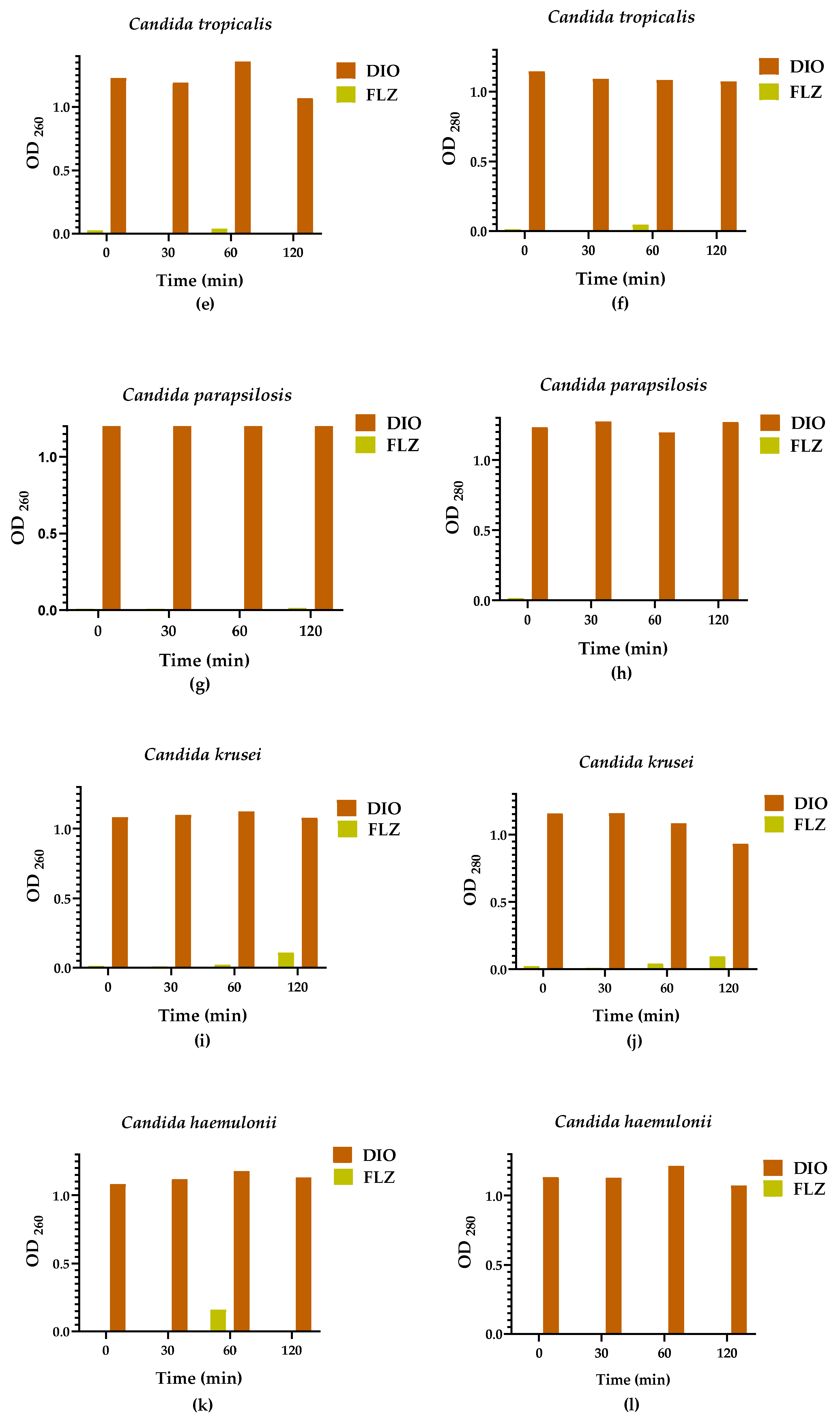

2.3. Leakage of Nucleic Acids and Proteins through the Fungal Membrane

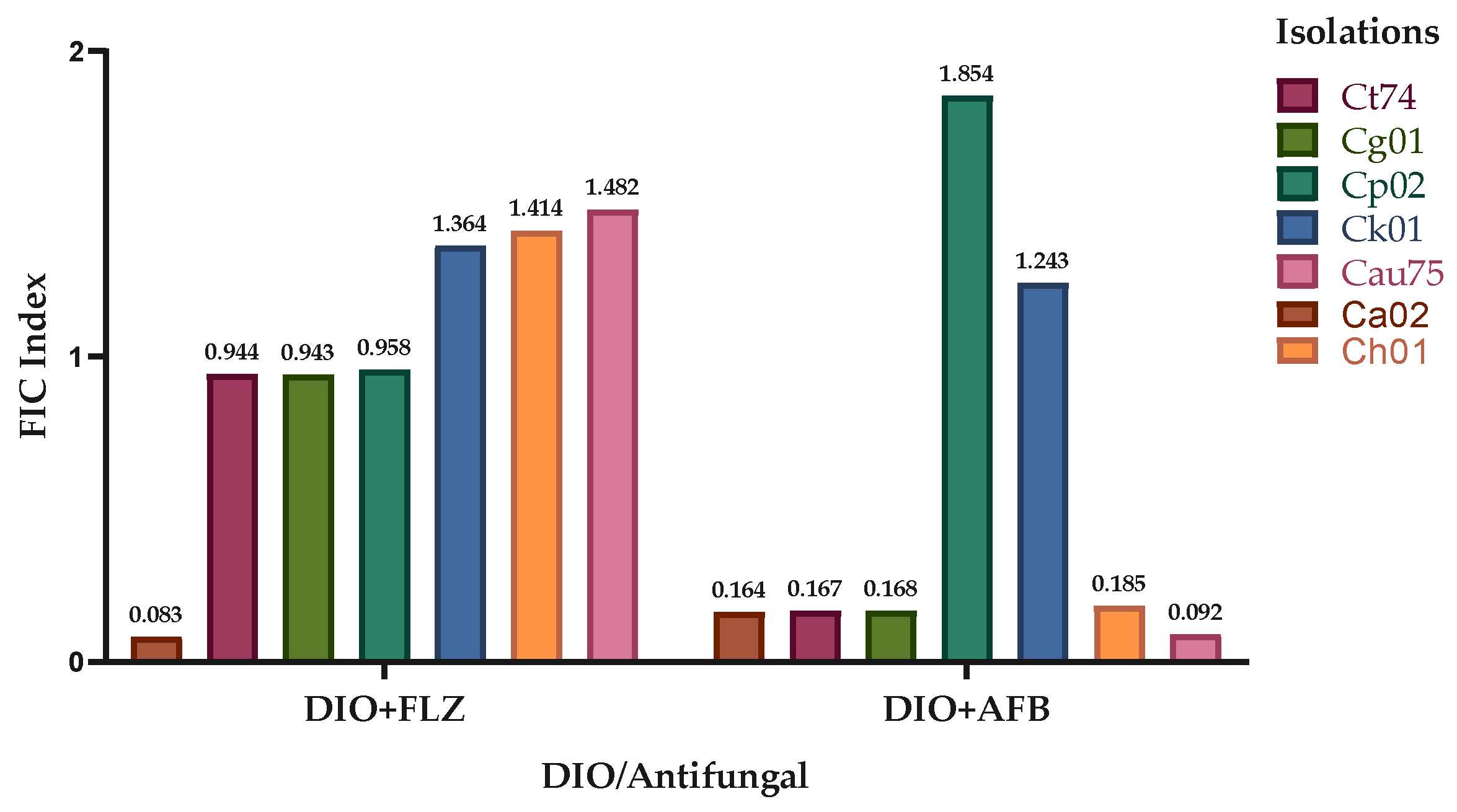

2.4. Diosmin Action in Combination with Commercial Antifungals

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

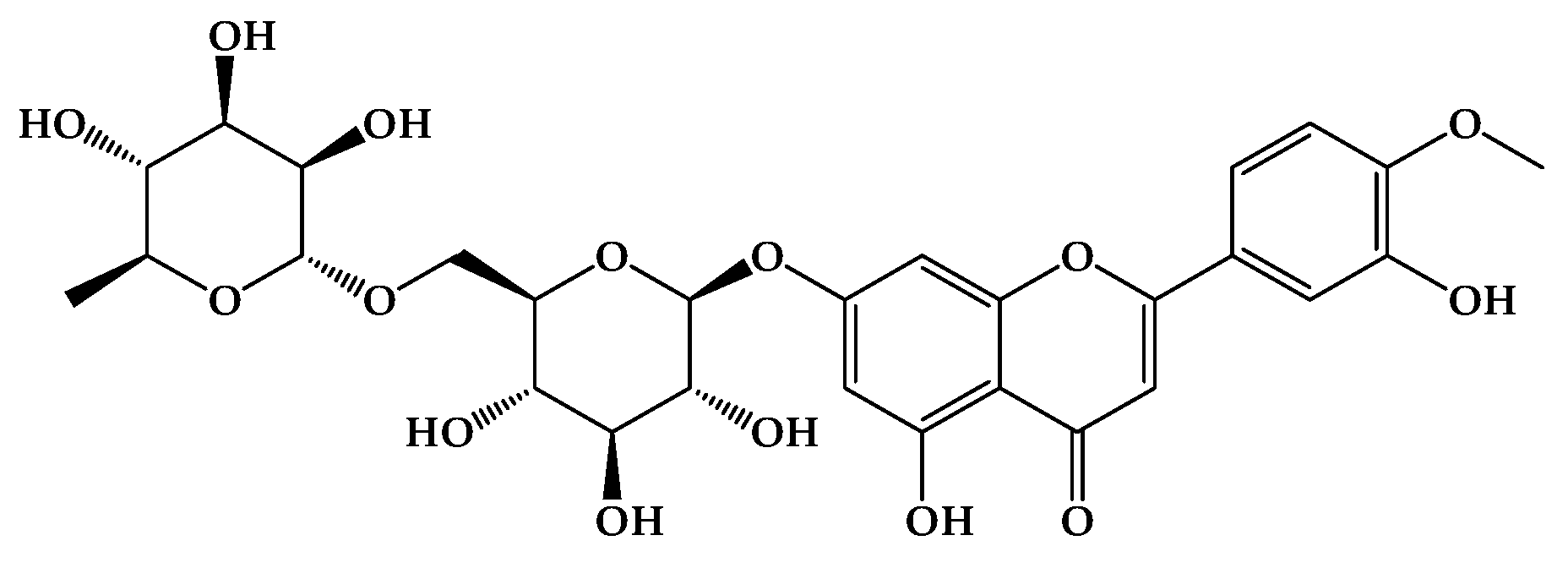

4.2. Diosmin (DIO)

4.3. Strains

4.4. Antifungal Susceptibility Testing

4.5. Quantitative Evaluation of Biofilm Inhibition

4.6. Leakage of Nucleic Acids and Proteins through the Fungal Membrane

4.7. Diosmin Action in Combination with Commercial Antifungals

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ibe, C.; Pohl, C. H. Epidemiology and drug resistance among Candida pathogens in Africa: Candida auris could now be leading the pack. The Lancet Microbe. Elsevier Ltd, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Bravo, J.; Romero-Romero, D.; Contreras-Rodríguez, A.; Aguilera-Arreola, M. G.; Parra-Ortega, B. Candida isolation during COVID-19: microbiological findings of a prospective study in a regional hospital. Arch Med Res 2024, 55, 6. [CrossRef]

- Koulenti, D.; Karvouniaris, M.; Paramythiotou, E.; Koliakos, N.; Markou, N.; Paranos, P.; Meletiadis, J.; Blot, S. Severe candida infections in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Journal of Intensive Medicine. Chinese Medical Association, 2023, pp 291–297. [CrossRef]

- Salmanton-García, J.; Cornely, O. A.; Stemler, J.; Barać, A.; Steinmann, J.; Siváková, A.; Akalin, E. H.; Arikan-Akdagli, S.; Loughlin, L.; Toscano, C.; Narayanan, M.; Rogers, B.; Willinger, B.; Akyol, D.; Roilides, E.; Lagrou, K.; Mikulska, M.; Denis, B.; Ponscarme, D.; Scharmann, U.; Azap, A.; Lockhart, D.; Bicanic, T.; Kron, F.; Erben, N.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Goodman, A. L.; Garcia-Vidal, C.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Gangneux, J. P.; Taramasso, L.; Ruiz, M.; Schick, Y.; Van Wijngaerden, E.; Milacek, C.; Giacobbe, D. R.; Logan, C.; Rooney, E.; Gori, A.; Akova, M.; Bassetti, M.; Hoenigl, M.; Koehler, P. Attributable mortality of candidemia – results from the ECMM candida III multinational European observational cohort study. Journal of Infection 2024, 89, 3. [CrossRef]

- Aslanov, P. B.; Ermakova, D. L.; Nabieva, D. A. Surveillance and prevention of fungal infections in the neonatal intensive care unit. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2025, 152, 107729. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G. R.; Jenks, J. D.; Baddley, J. W.; Lewis, J. S.; Egger, M.; Schwartz, I. S.; Boyer, J.; Patterson, T. F.; Chen, S. C. A.; Pappas, P. G.; Hoenigl, M. Fungal endocarditis: pathophysiology, epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2023, 36, 3. [CrossRef]

- Žiemytė, M.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J. C.; Ventero-Martín, M. P.; Mira, A.; Ferrer, M. D. Real-time monitoring of biofilm growth identifies andrographolide as a potent antifungal compound eradicating candida biofilms. Biofilm 2023, 5, 100134. [CrossRef]

- Cavalheiro, M.; Teixeira, M. C. Candida biofilms: threats, challenges, and promising strategies. Frontiers in Medicine 2018, 5, 28. [CrossRef]

- Brassington, P. J. T.; Klefisch, F.-R.; Graf, B.; Pfüller, R.; Kurzai, O.; Walther, G.; Barber, A. E. Genomic reconstruction of an azole-resistant Candida parapsilosis outbreak and the creation of a multi-locus sequence typing scheme: a retrospective observational and genomic epidemiology study. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6, 1, 100949. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, L. S.; Barbosa, P. F.; Lorentino, C. M. A.; Lima, J. C.; Braga, A. L.; Lima, R. V.; Giovanini, L.; Casemiro, A. L.; Siqueira, N. L. M.; Costa, S. C.; Rodrigues, C. F.; Roudbary, M.; Branquinha, M. H.; Santos, A. L. S. The multidrug-resistant Candida auris, Candida haemulonii complex and phylogenetic related species: insights into antifungal resistance mechanisms. Current Research in Microbial Sciences 2025, 8, 100354. [CrossRef]

- Arendrup, M. C.; Arikan-Akdagli, S.; Jørgensen, K. M.; Barac, A.; Steinmann, J.; Toscano, C.; Arsenijevic, V. A.; Sartor, A.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Hamprecht, A.; Matos, T.; Rogers, B. R. S.; Quiles, I.; Buil, J.; Özenci, V.; Krause, R.; Bassetti, M.; Loughlin, L.; Denis, B.; Grancini, A.; White, P. L.; Lagrou, K.; Willinger, B.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Hamal, P.; Ener, B.; Unalan-Altintop, T.; Evren, E.; Hilmioglu-Polat, S.; Oz, Y.; Ozyurt, O. K.; Aydin, F.; Růžička, F.; Meijer, E. F. J.; Gangneux, J. P.; Lockhart, D. E. A.; Khanna, N.; Logan, C.; Scharmann, U.; Desoubeaux, G.; Roilides, E.; Talento, A. F.; van Dijk, K.; Koehler, P.; Salmanton-García, J.; Cornely, O. A.; Hoenigl, M. European candidaemia is characterised by notable differential epidemiology and susceptibility pattern: results from the ECMM Candida III study. Journal of Infection 2023, 87, 5, 428–437. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-García, J.; Machado, M.; Alcalá, L.; Reigadas, E.; Sánchez-Carrillo, C.; Pérez-Ayala, A.; Gómez-García de la Pedrosa, E.; González-Romo, F.; Merino, P.; Cuétara, M. S.; García-Esteban, C.; Quiles-Melero, I.; Zurita, N. D.; Muñoz-Algarra, M.; Durán-Valle, M. T.; Martínez-Quintero, G. A.; Sánchez-García, A.; Muñoz, P.; Escribano, P.; Guinea, J.; Mesquida, A.; Gómez, A.; Muñoz, R. P.; González, M. del C. V.; Romo, F. G.; Merino-Amador, P.; Muñoz Clemente, O. M.; Berenguer, V. A.; Lobato, O. C.; Bernal, G.; Zurita, N.; Cobos, A. G.; Romero, I. S.; San Juan Delgado, F.; Romero, Y. G.; Fraile Torres, A. M. Antifungal resistance in Candida spp. within the intra-abdominal cavity: study of resistance acquisition in patients with serial isolates. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2023, 29, 12, 1604.e1-1604.e6. [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, A.; Zotchev, S.; Dirsch, V.; Taskforce, T. I. N. P. S.; Supuran, C. Natural products in drug discovery: advances and opportunities. Nature Reviews 2021, 20, 200–216. [CrossRef]

- Naman, C. B.; Benatrehina, P. A.; Kinghorn, A. D. Pharmaceuticals, Plant Drugs. In Breeding Genetics and Biotechnology, Second Edi.; Elsevier, 2016, 2. (pp. 93-99).

- Avato, P. Editorial to the Special Issue – “Natural Products and Drug Discovery". Molecules 2020, 25, 1128. [CrossRef]

- Ciriminna, R.; Petri, G. L.; Angellotti, G.; Luque, R.; Fabiano Tixier, A.; Meneguzzo, F.; Pagliaro, M. Citrus flavonoids as antimicrobials. Chem Biodivers 2025, e202403210. [CrossRef]

- Gerges, S. H.; Wahdan, S. A.; Elsherbiny, D. A.; El-Demerdash, E. Pharmacology of diosmin, a citrus flavone glycoside: an updated review. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2022. 47, 1, 1-18 . [CrossRef]

- Cazaubon, M.; Benigni, J. P.; Steinbruch, M.; Jabbour, V.; Gouhier-Kodas, C. Is there a difference in the clinical efficacy of diosmin and micronized purified flavonoid fraction for the treatment of chronic venous disorders? review of available evidence. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2021, 17, 591-600. [CrossRef]

- Hassanein, E. H. M.; Althagafy, H. S.; Baraka, M. A.; Amin, H. Hepatoprotective effects of diosmin: a narrative review. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology 2025, 398, 1, 279-295 . [CrossRef]

- Klimek-szczykutowicz, M.; Szopa, A.; Ekiert, H. Citrus limon (Lemon) phenomenon—a review of the chemistry, pharmacological properties, applications in the modern pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetics industries, and biotechnological studies. Plants, 2020, 9, 1, 119. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Shi, W.; Li, L.; Liu, H.; Chen, Z.; Wu, L. Metabolism and pharmacological activities of the natural health-benefiting compound diosmin. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 10,8472-8492. doi: 10.1039/d0fo01598a.

- Carević, T.; Kolarević, S.; Kolarević, M. K.; Nestorović, N.; Novović, K.; Nikolić, B.; Ivanov, M. Citrus flavonoids diosmin, myricetin and neohesperidin as inhibitors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: evidence from antibiofilm, gene expression and in vivo analysis. Biomed Pharmacother 2024, 181, 117642. [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, S.; Akbar, M.; Khan, M. A.; Sunita, K.; Parveen, S.; Pawar, J. S.; Massey, S.; Agarwal, N. R.; Husain, S. A. Plant metabolite diosmin as the therapeutic agent in human diseases. Curr Res Pharmacol Drug Discov 2022. 3, 100122. [CrossRef]

- Yarmolinsky, L.; Nakonechny, F.; Budovsky, A.; Zeigerman, H.; Khalfin, B.; Sharon, E.; Yarmolinsky, L.; Ben-Shabat, S.; Nisnevitch, M. Antimicrobial and antiviral compounds of Phlomis viscosa poiret. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2. [CrossRef]

- Pushkaran, A. C.; Vinod, V.; Vanuopadath, M.; Nair, S. S.; Nair, S. V.; Vasudevan, A. K.; Biswas, R.; Mohan, C. G. Combination of repurposed drug diosmin with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid causes synergistic inhibition of mycobacterial growth. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 1. [CrossRef]

- Chan, B. C. L.; Ip, M.; Gong, H.; Lui, S. L.; See, R. H.; Jolivalt, C.; Fung, K. P.; Leung, P. C.; Reiner, N. E.; Lau, C. B. S. synergistic effects of diosmetin with erythromycin against ABC transporter over-expressed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) RN4220/PUL5054 and inhibition of MRSA pyruvate kinase. Phytomedicine 2013, 20, 7, 611–614. [CrossRef]

- Aires, A.; Marrinhas, E.; Carvalho, R.; Dias, C.; Saavedra, M. J. Phytochemical composition and antibacterial activity of hydroalcoholic extracts of Pterospartum tridentatum and Mentha pulegium against Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Biomed Res Int 2016, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Barberis, A.; Deiana, M.; Spissu, Y.; Azara, E.; Fadda, A.; Serra, P. A.; D’Hallewin, G.; Pisano, M.; Serreli, G.; Orrù, G.; Scano, A.; Steri, D.; Sanjust, E. Antioxidant, antimicrobial, and other biological properties of pompia juice. Molecules 2020, 25, 14. [CrossRef]

- Contreras, O.; Angulo, A.; Santafé, G. Antifungal potential of isoespintanol extracted from Oxandra xylopioides diels (Annonaceae) against intrahospital isolations of Candida spp. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11110. [CrossRef]

- Guembe, M.; Cruces, R.; Peláez, T.; Mu, P.; Bouza, E. Assessment of biofilm production in candida isolates according to species and origin of infection. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2017, 35, 1, 37–40. [CrossRef]

- Kawai, A.; Yamagishi; Mikamo, H. Time-lapse tracking of Candida tropicalis biofilm formation and the antifungal efficacy of liposomal amphotericin B. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 70, 559–564. [CrossRef]

- Helmy, M. W.; Ghoneim, A. I.; Katary, M. A.; Elmahdy, R. K. The synergistic anti-proliferative effect of the combination of diosmin and BEZ-235 (Dactolisib) on the HCT-116 colorectal cancer cell line occurs through inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/MTOR/NF-ΚB Axis. Mol Biol Rep 2020, 47, 3, 2217–2230. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, N. A. ´; Vicente, V.; Martínez, C. Synergistic Effect of Diosmin and Interferon-a on Metastatic Pulmonary Melanoma. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 2009, 24, 3, 347-52. [CrossRef]

- Artanti, A. N.; Jenie, R. I.; Rumiyati, R.; Meiyanto, E. Hesperidin and diosmin increased cytotoxic activity cisplatin on hepatocellular carcinoma and protect kidney cells senescence. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2024, 25, 12, 4247–4255. [CrossRef]

- Zeya, B.; Nafees, S.; Imtiyaz, K.; Uroog, L.; Fakhri, K. U.; Rizvi, M. A. M. Diosmin in combination with naringenin enhances apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Oncol Rep 2022, 47, 1. [CrossRef]

- Cantón, E.; Martín, E.; Espinel-Ingroff, A. Métodos estandarizados por el CLSI para el estudio de la sensibilidad a los antifúngicos (Documentos M27-A3, M38-A y M44-A). Rev Iberoam Micol 2007, 15, 1–17.

- Rodriguez-Tudela, J. L. Method for determination of minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) by broth dilution of fermentative yeasts. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2003, 9, 467–474. [CrossRef]

- Contreras, O.; Angulo, A.; Santafé, G. Mechanism of antifungal action of monoterpene isoespintanol against clinical isolates of Candida tropicalis. Molecules 2022, 27, 5808. [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Martínez, O. I.; Angulo-Ortíz, A.; Santafé Patiño, G.; Sierra Martinez, J.; Berrio Soto, R.; de Almeida Rodolpho, J. M.; de Godoy, K. F.; de Freitas Aníbal, F.; de Lima Fragelli, B. D. Synergistic antifungal effect and in vivo toxicity of a monoterpene isoespintanol obtained from Oxandra xylopioides Diels. Molecules 2024, 29, 18. [CrossRef]

| Candida spp. | DIO MIC50 | DIO MIC90 | FLZ MIC90 |

| Ca02 | 660.4 | 1150 | 55.34 |

| Ca77 | 1079 | 1952 | 2.3 |

| Ct03 | 916 | 1756 | 154.5 |

| Ct74 | 808.8 | 1526 | 241.8 |

| Cg01 | 1199 | 2251 | 214.3 |

| Ch01 | 853.2 | 1655 | 133.9 |

| Ck01 | 1168 | 2118 | 69.99 |

| Cp02 | 947 | 1670 | 42.09 |

| Cau75 | 669.7 | 1786 | 75.65 |

| Candida spp. isolates | DIO | AFB |

| C. albicans | 00.00 ± 4.39 | 00.00 ± 4.48 |

| C. glabrata | 00.00 ± 6.63 | 00.00 ± 4.77 |

| C. tropicalis | 35.35 ± 1.88 | 6.49 ± 0.92 |

| C. haemulonii | 69.81 ± 1.16 | 12.75 ± 3.92 |

| C. auris | 74.75 ± 4.22 | 38.49 ± 3.71 |

| C. krusei | 78.41 ± 4.79 | 91.26 ± 2.17 |

| C. parapsilosis | 87.85 ± 2.18 | 30.43 ±2 .78 |

| Candida spp. isolates | DIO | AFB |

| C. albicans | 00.00 ± 3.12 | 00.00 ± 3.14 |

| C. glabrata | 00.00 ± 5.68 | 00.00 ± 5.41 |

| C. tropicalis | 11.53 ± 3.09 | 10.2 ± 1.67 |

| C. haemulonii | 00.00 ± 0.00 | 00.00 ± 0.00 |

| C. auris | 23.65 ± 1.24 | 4.24 ± 3.48 |

| C. krusei | 11.92 ± 2.99 | 19.67 ± 3.32 |

| C. parapsilosis | 00.00 ± 0.00 | 00.00 ± 0.00 |

| Candida spp. | MIC90 Single | MIC90 in Combination | FIC Indices | Effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLZ | AFB | DIO | FLZ-DIO | AFB-DIO | FLZ-DIO | AFB-DIO | FLZ-DIO | AFB-DIO | |

| Ca02 | 55.34 | 9.91 | 1150 | 2.2 - 49.9 | 0.82 - 93.99 | 0.08 | 0.16 | Sng | Sng |

| Ct74 | 241.8 | 9.87 | 1526 | 112.6 – 730.6 | 1.18 - 73.32 | 0.94 | 0.17 | Sng | Sng |

| Cg01 | 214.3 | 4.11 | 2251 | 103.5 - 1036 | 0.35 - 186.9 | 0.94 | 0.17 | Sng | Sng |

| Ch01 | 133.9 | 8.89 | 1655 | 94.7 - 1170 | 0.82 - 153.5 | 1.41 | 0.18 | S.I. | Sng |

| Ck01 | 69.99 | 3.30 | 2118 | 46.9 - 1469 | 2.08 - 1298 | 1.36 | 1.24 | S.I. | S.I. |

| Cp02 | 42.09 | 4.05 | 1670 | 20.3 - 792.7 | 3.791- 1534 | 0.96 | 1.85 | Sng | S.I. |

| Cau75 | 75.65 | 18.41 | 1786 | 55.4 - 1338 | 0.853-82.89 | 1.48 | 0.09 | S.I. | Sng |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).