1. Introduction

Scientific research plays a crucial role in driving technological advancements and fostering economic growth. In Japan, where natural resources are limited, science and technology have been fundamental pillars of national strength. Over the past few decades, the Japanese government has implemented various policies to enhance research and innovation, with the aim of maintaining the country's global competitiveness (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications 2016). However, contrary to their original intentions, these policies have significantly impacted the structure, sustainability, and overall productivity of scientific research in Japan.

This review examines how science policy changes have affected Japan's research ecosystem over recent decades. To address these challenges, this review also explores potential remedies, including the role of University Research Administrators (URAs), a recently introduced profession in academia (Takahashi and Ito 2023). The review aims to provide insights into balancing research funding allocations, ensuring sustainable career pathways, and reinvesting in fundamental science to revitalize Japan's scientific foundation.

2. Analytical Framework

This review examines the impact of Japanese science and technology policy reforms through an analytical framework structured around three key dimensions: financial resources ("money"), temporal capacity ("time"), and human capital ("people"). These categories are not novel but are widely acknowledged in the science policy literature as central to sustaining long-term, curiosity-driven research (Igami 2017). "Money" refers to changes in national-level research funding structures, including the shift toward competitive grants and targeted allocations, and their effects on basic science (Aagaard, Kladakis, and Nielsen 2019). "Time" captures the reduction in researchers' available hours for scientific work due to increasing administrative and institutional demands (Monde 2024). "People" addresses the destabilization of research careers, the rise of fixed-term employment, the declining number of graduate students, and growing psychological stress among researchers (Hornyak 2022).

By organizing the analysis along these three dimensions, this paper provides a systematic lens through which to evaluate the cumulative effects of policy reforms on Japan's research ecosystem. This approach allows the discussion to move beyond individual policy components and toward an integrated understanding of how financial resources, time, and people—three core pillars of scientific work—have been reshaped by policy-driven institutional reforms.

3. Japan: science and technology-driven country

Japan, which is scarce in natural resources, should base its national strength on scientific research and technological development (Omi 1996). This belief is embodied by the Science and Technology Basic Law, enacted in 1995, which requires formulation of a new basic plan every five years. The plan guides science and technology policy for the relevant period. The first plan started in 1995, was renamed at 6th plan in 2021 as the “Science, Technology, and Innovation Basic Plan”, in accordance with the amendment of the above law as the “Science, Technology and Innovation Basic Law” enforced in 2020. This change was made to put more stress on fostering innovation and redirecting universities toward implementation of the research and development for the society, rather than conducting just curiosity–driven researches. These plans describes specific science policy measures to be executed and thus drive the advancement of science and technology, and realize innovation in Japan. The Science, Technology and Innovation Basic Plan is formulated with an eye on trends in the Japanese economy. It includes a target ratio of research funding to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and specific strategies and policies to stimulate scientific research development(Mitsubishi Research Institute Inc. 2016).

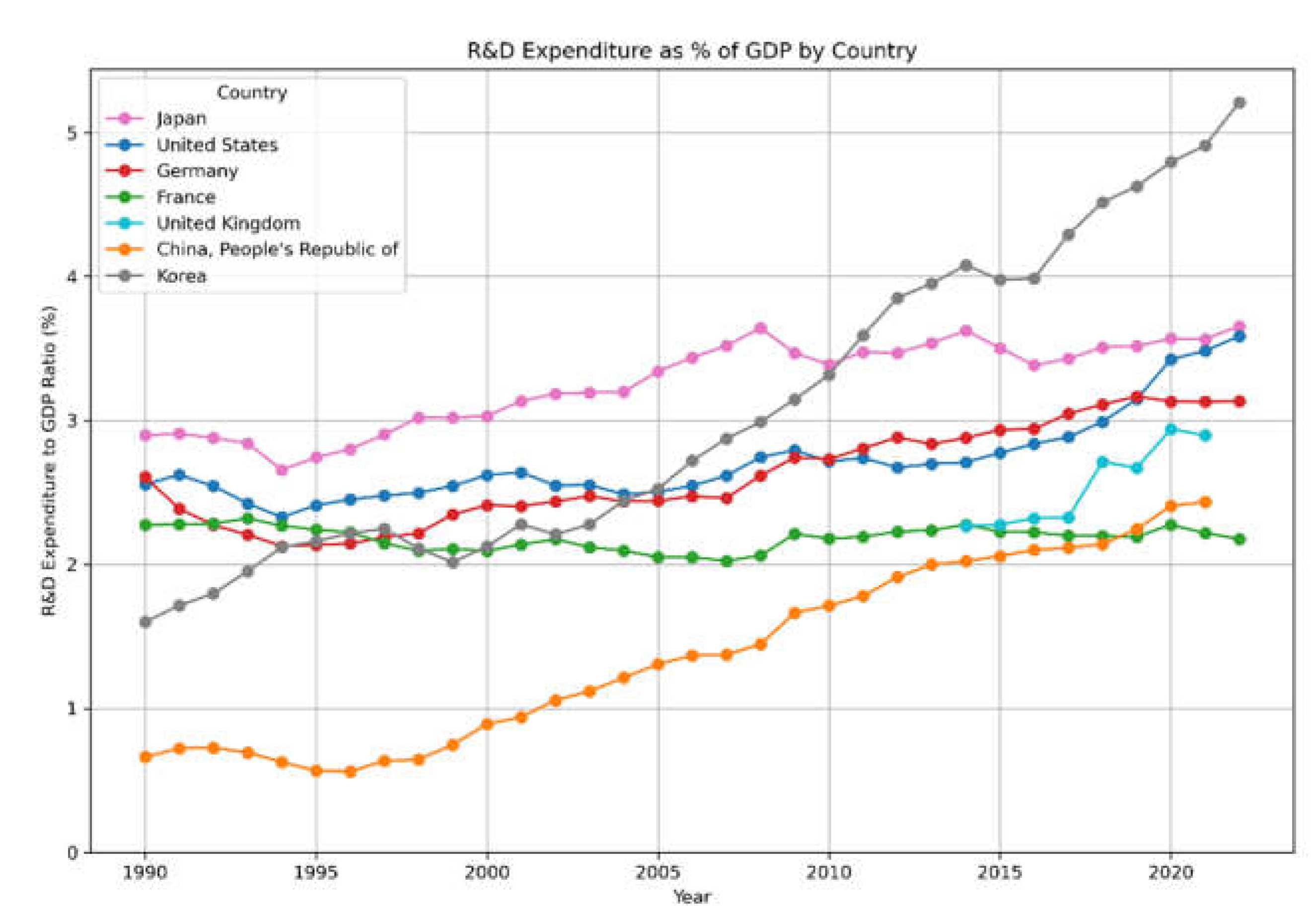

Japan’s research and development expenditure, when expressed as a percentage of GDP, has exhibited limited growth over the past 15 years, particularly in comparison with other science-oriented G7 countries and neighboring economies (

Figure 1). In the 5th Science and Technology Basic Plan that covered 2016-2020 period, a target was set to achieve research and development (R&D) investment of at least 4% of GDP through both public and private sector contributions. However, this goal has not yet been achieved. In 2023, a record-high research and development (R&D) investment of 3.7% of GDP was recorded. (Source:

2024 (Reiwa 6) Report on the Survey of Research and Development, Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications) (

https://www.stat.go.jp/data/kagaku/index.html). Thus, Japan's research and development investments remain insufficient to support its self-proclaimed status as a science-driven nation.

4. Stagnation of economy and decrease of scientific strength in Japan

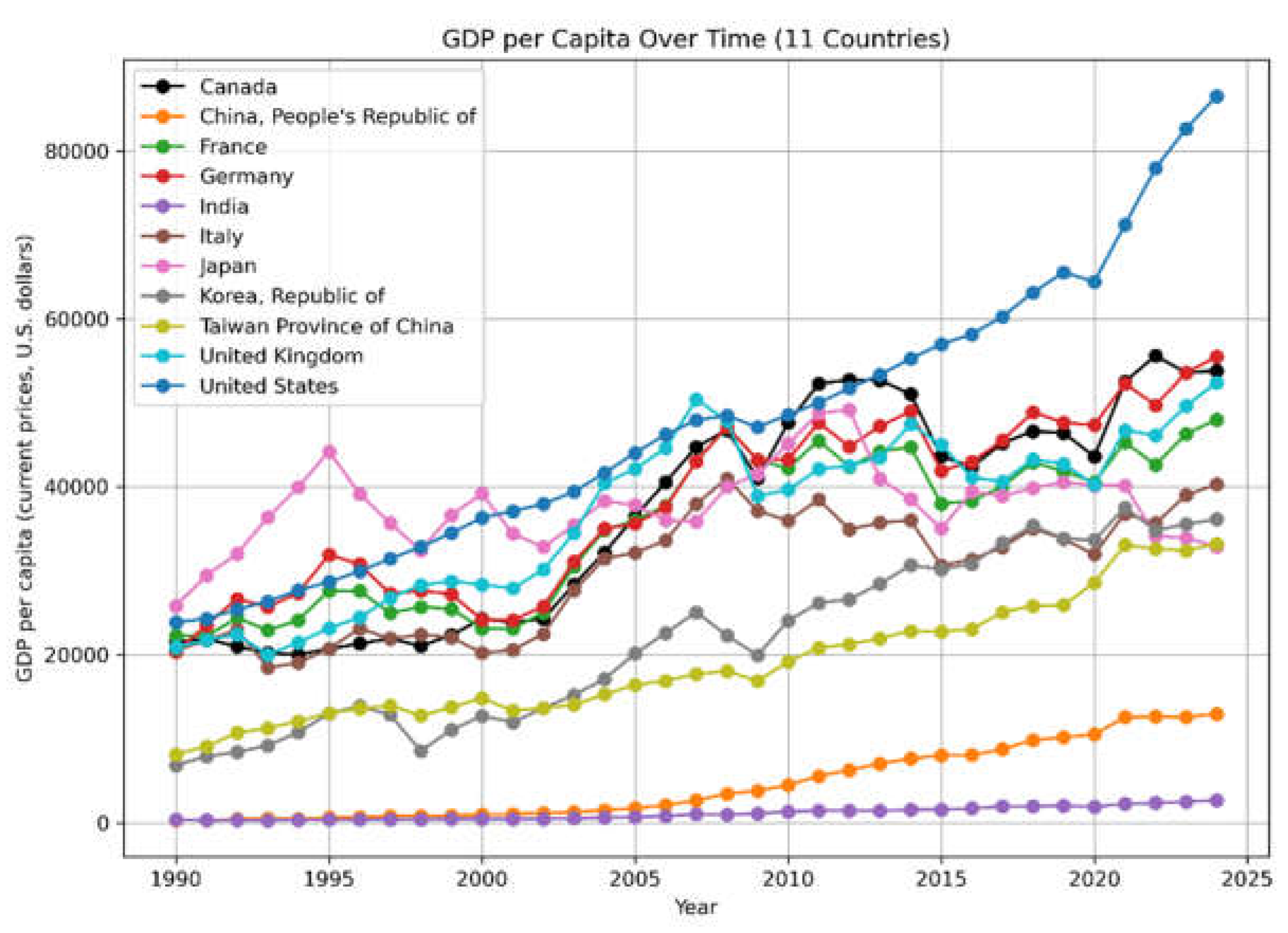

Because economic growth is closely interrelated with advances in science and technology—each reinforcing the other (Watanabe and Hemmert 1998)—stagnation in one has a severe impact on the other. Now Japan is suffering from staggering in both. Japanese economic growth has been staggering over the last 30 years as shown in the comparison among G7 countries and Japan’s neighbors (

Figure 2, Data from IMF at

https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/). Besides, Japan is the only country in G7 that showed virtually no increase of average wages over the last 30 years (Asia Pacific Dept International Monetary Fund (IMF) 2023). Japan, therefore, cannot be regarded as a rich country anymore. Given the interrelationships between science and economy, it may not be surprising that Japanese research activities have also been staggering, which was demonstrated as decreases in the ranking of number of scientific publications, and top 10% most cited papers (13

th in the ranking measured during 2019-2021)(Ikarashi 2023; National Institute of Science and Technology Policy (NISTEP) 2024). The decline of scientific activity has been readily recognized, warned, and discussed(Mainichi Shimbun Investigative Team 2019; Toyoda 2019; Iwamoto 2019 ).

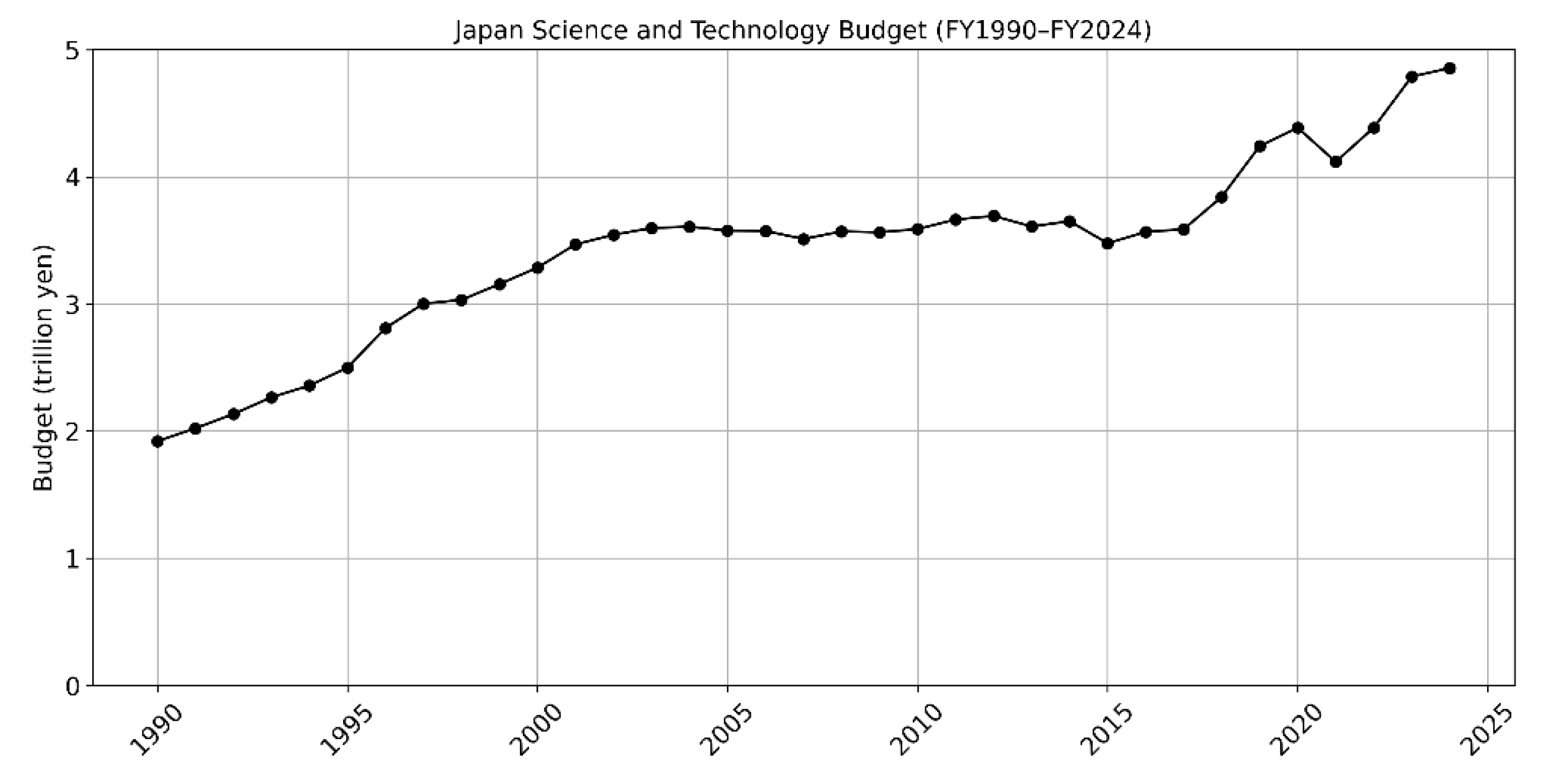

Does this indicate that the overall budget for science and technology has been reduced in recent years? Not necessarily. Although there have been periods of stagnation and even slight declines, the government’s budget for science and technology has generally increased over the past few decades (

Figure 3). The issue is not the total amount of funding, but rather the manner in which these funds are allocated. In recent years, changes in Japanese science policies—such as the introduction of the "competition principle" and "selection and concentration"—have notably affected basic research in particular. Nonetheless, the targeted allocation of funds is only one factor that has impacted scientific research in Japan. Other factors include issues related to "people" and "time": a decrease in the number of doctoral students and tenure-track researchers, as well as insufficient time dedicated to research. In the following sections, we will examine these factors in detail.

5. Corporatization of National Universities: Intended Reforms and Unintended Consequences

In Japan, basic scientific research, which serves as a critical source of technological innovation, is primarily conducted by universities, whereas industrial research tends to be more application-oriented. In particular, national universities have a primary role since more than half of the national budget for basic research, KAKENHI granted by MEXT, are distributed to national universities. For example, KAKENHI in 2024 were awarded to national universities with 59.8% (34.9 billion yen), private universities with 20.9% (12.2 billion yen), public universities with 6.0% (3.5 billion yen), and other institutes for the rest (MEXT statistics

https://www.jsps.go.jp/file/storage/kaken_27_kohyo6-1/0-1_r6.pdf). Therefore, any changes in policies regarding national universities have significant influences on the research activities in Japan.

In 2004, the Japanese government transformed national universities into corporate entities under a new legal framework. This corporatization was implemented with the aim of enhancing managerial autonomy, enabling universities to operate more flexibly, and fostering competition among institutions to improve performance and global visibility. According to MEXT, the shift was intended to allow each university to define its own strategic direction, streamline operations, and develop distinctive educational and research profiles (MEXT 2023; Amano 2006).

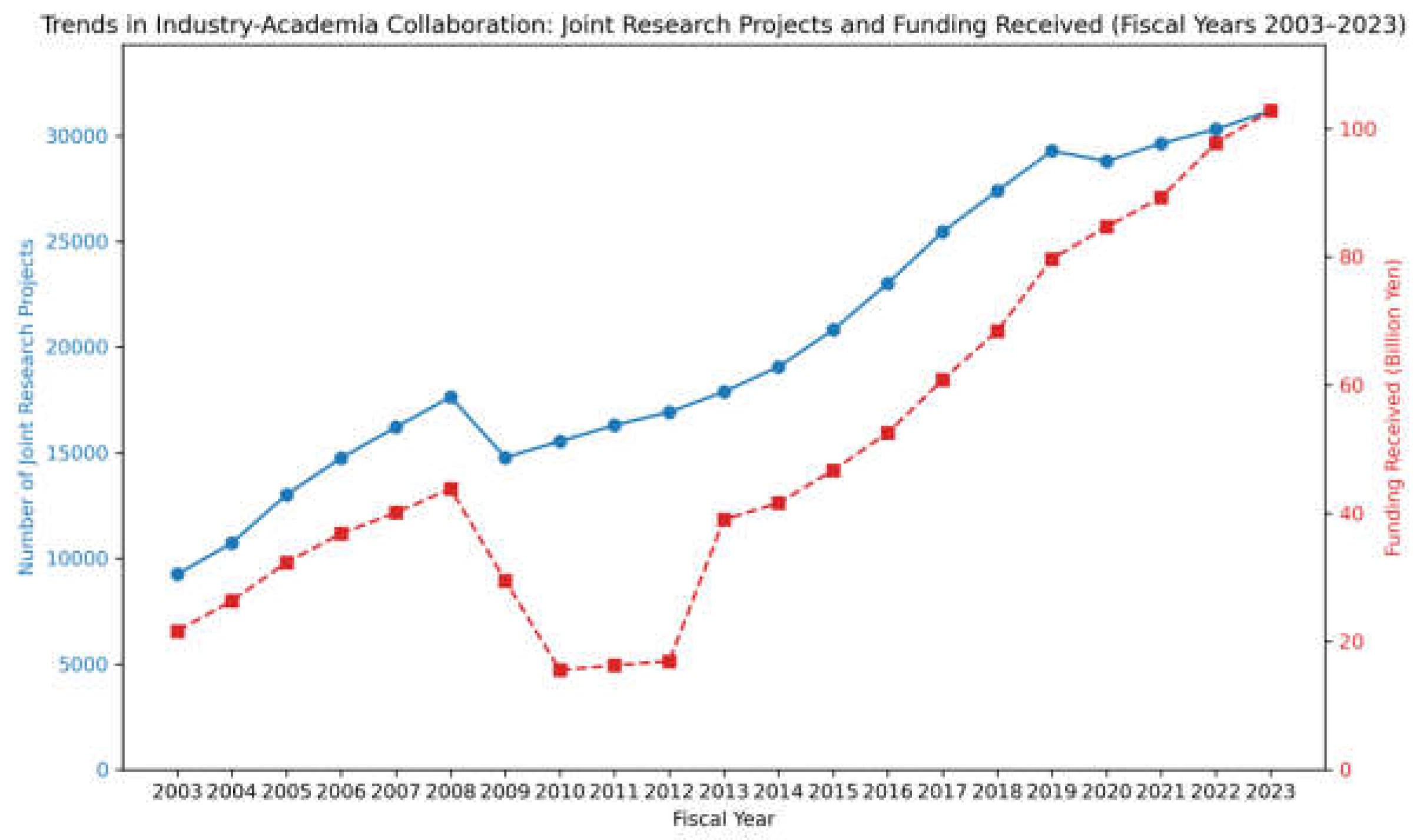

After corporatization, national universities in Japan steadily increased their industry-academia collaborations, boosting the number and value of joint and commissioned research projects (

Figure 4). Many universities established dedicated liaison offices, set up incentive systems for faculty engagement, and strengthened intellectual property management. As a result, self-generated income from commissioned research, intellectual property licensing, and donations significantly increased, leading to greater financial autonomy and improved transparency in university management (Yoshida 2007). In an interview (

https://kyoiku.yomiuri.co.jp/rensai/contents/41-1.php), Makoto Gokami, President of the University of Tokyo states that corporatization was inevitable, with no real alternatives available at the time. He notes that the deterioration of national universities had already become a serious problem by the 1980s, and suggests that had the situation been allowed to continue, the outcome would have been even more disastrous. He defined the university as a "hub for driving social transformation" and has undertaken reforms in university management, including the issuance of Japan’s first university bonds in 2020, through which 20 billion yen was raised.(Gokami 2019; Murata 2021; Hanawa 2021). Overall, corporatization opened up new avenues for national universities to strengthen their financial autonomy, promote innovation, and enhance their role as engines of societal transformation.

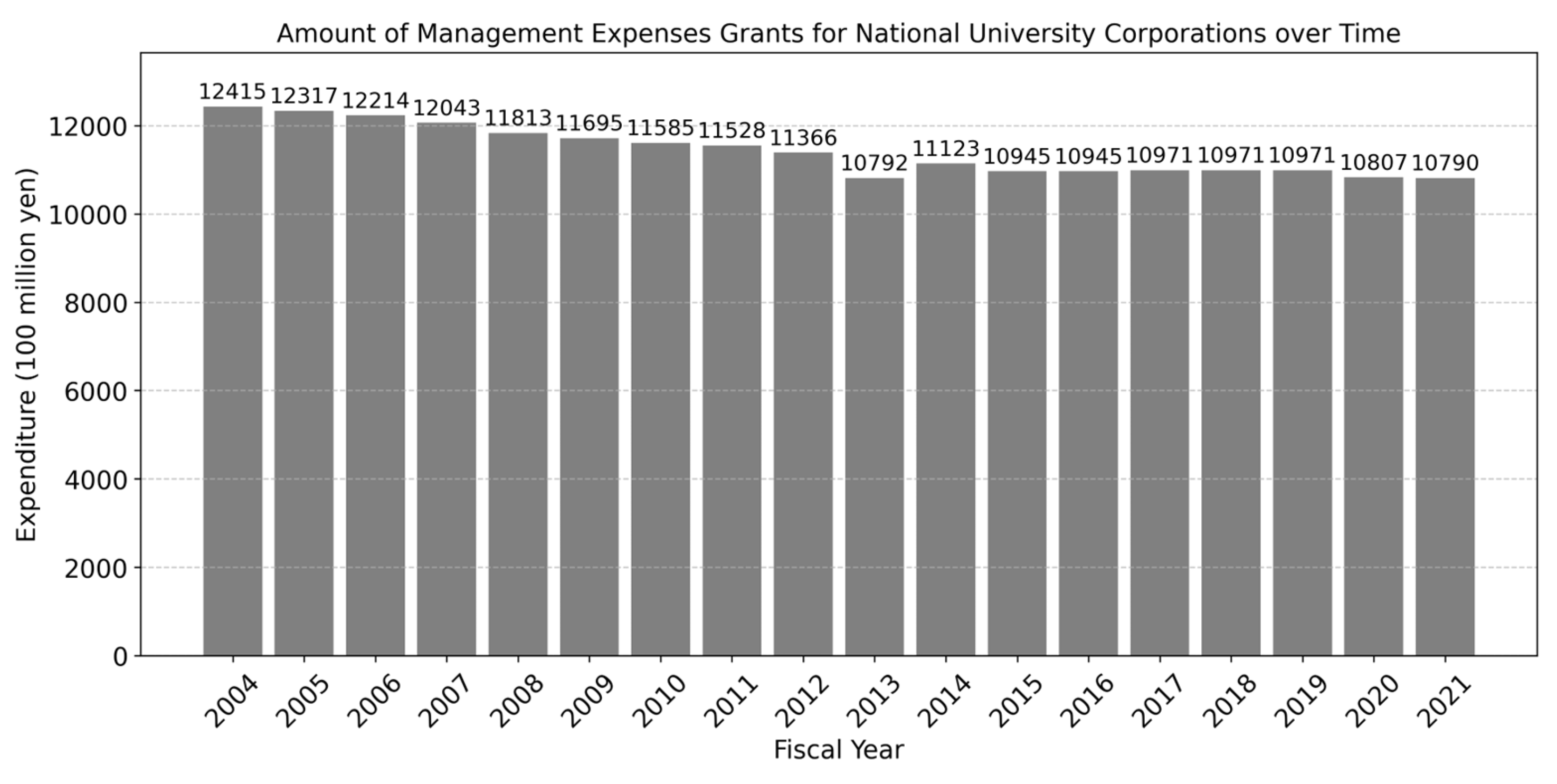

However, despite these intended benefits, the implementation of corporatization has also produced negative consequences for Japan's academic research system (Yamagiwa and Fujii 2018; Asahi Shimbun Investigative Team 2024; Mainichi Shimbun Investigative Team 2019). Most notably, the policy was accompanied by a steady reduction in the "Management Expenses Grants for National University Corporations"—a key source of stable institutional funding. The grants were reduced by approximately 1% annually, resulting in a 10% decrease over a decade (

Figure 5), based on the assumption that universities would compensate for the shortfall through increased competitiveness and external income generation. This was realized as a result of the Ministry of Finance's strong intent (Mainichi Shimbun Investigative Team 2019; Yamagiwa and Fujii 2018). The routine research and development funding per faculty member has decreased in tandem with reductions in operating expense grants (Igami and Kanda 2024). In practice, this reduction in core funding has severely constrained routine research activities.

Obviously, the corporatization of national universities and the reduction of Management Expense Grants for National University Corporations are two distinct issues and should not be conflated. Indeed, during the process of enacting the National University Corporation Act, the following supplementary resolution was adopted: "In calculating the amount of management expense grants and other funding, efforts must be made to secure an amount that ensures education and research activities at each national university can be carried out even more reliably than before, taking into full account the level of public funding provided prior to incorporation." (Supplementary Resolution, July 8, 2003) (

https://www.sangiin.go.jp/japanese/joho1/kousei/gian/156/pdf/k031560561560.pdf). Contrary to this resolution, however, the reduction of Management Expense Grants has been implemented alongside corporatization (Mizuta 2024). Akito Arima, who as Minister of Education played a leading role in promoting the corporatization of national universities, later expressed regret, characterizing the reform as a failure due to the government's failure to uphold its initial promises (Nakayama 2020).

Policies that gradually extended the retirement age from 60 to 65 implemented during the same period (2001-2013) further tightened the budgets in national universities. Since a major portion of the Management Expenses Grants was used to fund faculty salaries, many institutions were forced to freeze new permanent hires, leading to a shortage of younger faculty and a decline in faculty diversity (Nakatomi 2011; Gokami 2019).

While the overall operational budget decreased, the proportion of funding distributed through competitive grants increased. For example, the FY2004 and FY2018 were compared, while total science budget decreased by 5% from 1.93 trillion yen to 1.84 trillion yen, the competitive grant increased from 0.36 trillion yen to 0.43 trillion yen, or 18.7% to 23.2% of the total amount (MEXT 2018a). In 2019, the government went further and introduced MEXT-evaluation based differential allocation for approximately 10% of the Management Expenses Grants for National University Corporations, despite the grants’ original purpose of serving as a source of fundamental research funding (Asahi Shimbun Investigative Team 2024; Takeuchi 2019). Thus, the trend toward increasingly competitive allocation of funding shows no sign of abating and has had a significant impact on the basic operation of scientific research. Competitive allocation of funding based on university evaluations conducted by MEXT raises another crucial issue—namely, the potential threat to university autonomy—although that is beyond the scope of this review paper. There is strong concern that the evaluation-based allocation of Management Expense Grants has been used as a means of controlling university behavior (Asahi Shimbun Investigative Team 2024).

While the principle of university self-governance remains an admirable goal, the financial and administrative pressures arising from corporatization have arguably undermined the ability of national universities to sustain a vibrant research environment. The adoption of corporatized governance structures—marked by centralized control, performance-based evaluations, and managerial oversight—has often led to increased bureaucratization, constrained academic discretion in hiring and budgeting, and heightened pressure to deliver short-term results. Rather than fostering strategic innovation and autonomy, the reforms have produced resource-starved institutions caught in a cycle of competition and compliance. In sum, while corporatization was introduced as a means to modernize governance and improve agility, the simultaneous reduction of core institutional funding has significantly weakened Japan’s research ecosystem, raising deep concerns about its long-term resilience and international competitiveness. (Shimada 2022; Asahi Shimbun Investigative Team 2024).

6. “ Selection and concentration”: a shift toward top-down, targeted budget allocation prioritizing specific research areas

Alongside the introduction of competitive principles, the notion of “selection and concentration” has been upheld as a tenet. This targeted budget allocation approach, whereby the Japanese government directs funds toward select research areas, first emerged in the Second Basic Plan for Science and Technology (FY2001–FY2005). The second plan concentrated investment on four specific fields chosen by the government, and the tendency toward prioritization in budget distribution has grown ever more pronounced in subsequent years. Because the overall science and technology budget was not increased, areas not prioritized—and even essential expenditures such as operating subsidies for national universities—experienced budget cuts.

A key proponent of this prioritization approach is the Council for Science, Technology and Innovation (CSTI). Although the CSTI originally did not have authority over budget allocation, a 2013 amendment to the Act for Partial Revision of the Act for the Establishment of the Cabinet Office enabled the Cabinet Office to secure its own budget. Consequently, the CSTI evolved from an organization that objectively assessed budgets into one that allocates its own funds and administers large-scale research grant programs (Suda 2021). Another notable aspect of this targeted budget allocation is its application-oriented nature, which tends to overlook basic science. Research proposals that present a clear pathway to practical implementation are more likely to receive funding. Yet, groundbreaking innovations are rarely predictable at the stage when their foundational ideas are conceived in basic research; their significance is often recognized only in hindsight.

In the preceding sections, the focus has been on “money.” We now turn to the issue of “people.” At the heart of scientific progress are the individuals engaged in research. Without exceptionally talented scientists, no meaningful advances in science can be achieved.

7. Introduction of the fixed-term employment system into national and public universities institutes and its drawbacks

A common argument about the factor hindering university research is the presence of aging faculty whose activity levels are declining. In order to foster continual academic exchange and acceptance of diverse expertise—vital for energizing education and research, in 1997, at national universities, fixed-term employment was introduced, as outlined by the law “Act on Term of Office of University Teachers, etc.”. By this law, positions other than full professorships and tenure-track associate or assistant professorships in national and public universities became subject to fixed-term contracts. This had a huge impact on scientific research community in Japan. The contracts typically last five years with only one possible renewal, with a maximum contract duration of ten years before mandatory departure. Although postdoctoral researchers were already in unstable positions due to short-term contracts ranging from one to several years, assistant professors—who are mostly non-tenured in Japan—as well as higher-ranked lecturers and associate professors without tenure, also found themselves in precarious situations. Even if they produced notable results and built strong publication records, this did not necessarily lead to a permanent position due to extremely limited job availability. In some cases, individuals even reverted from assistant professorship back to postdoctoral positions, further highlighting the severe instability of the system (Young Academy of Japan 2014).

Fixed-term positions come with obvious drawbacks in Japanese science development. First, in this situation, many young researchers are compelled to choose research topics that yield short-term results, leaving them little room to take on ambitious projects that could lead to significant innovation. Second, researchers must constantly search for their next position, preventing them from fully dedicating themselves to their work. Third, fixed-term faculty members often feel compelled to prioritize their own career progression over student education.

The limited prospects for securing a permanent academic position have been associated with elevated psychological stress among researchers. This issue has been highlighted in various reports, including a 2022 Nature article in which early-career scientists in Japan describe feeling “disposable” under fixed-term employment arrangements (Hornyak 2022). Similarly, Katayama (2022) documents numerous cases of forced contract terminations, suggesting systemic instability in research employment (Katayama 2022). In some instances, stress arising from job insecurity has been mentioned in connection with scientific misconduct, though comprehensive psychological studies on this relationship remain limited. These observations indicate the need for further empirical investigation into how employment conditions affect research ethics and morale in Japan’s academic system.

The former president of the University of Tokyo, Dr. Makoto Gokami succinctly captures the current state of academia in his book, A Vision for the Future of Universities: Building a Knowledge-Intensive Society (tentative translation) (2019), stating: "Researchers hired on fixed-term contracts are not necessarily granted permanent positions, even if they achieve significant research accomplishments. As a result, many young researchers are forced to conduct their work under constant uncertainty about their future." This situation significantly influences the career decisions of undergraduate students in the lab, as they witness firsthand how even accomplished senior researchers struggle to secure permanent positions. Thus, research positions no longer constitute a genuine profession, rendering them unappealing as a career path for younger generations.

8. Non-renewal of contracts and its negative effect on the sustainability of Japanese science

Non-renewal of contracts—commonly known as “Yatoi-dome” in Japanese—has become a pervasive issue in Japanese academia, undermining the sustainability of scientific research (The Science Council of Japan's Executive Committee 2022; Katayama 2022). This practice affects a wide range of fixed-term employees, including postdoctoral researchers, laboratory technicians, and university administrative staff as well as university faculty. Originally, the amended Labor Contract Act—effective from April 1, 2013—introduced the “indefinite-term conversion rule” with an intention to ensure job stability for temporary workers. Under this rule, employees in administrative or educational positions gain the right to convert their contracts to indefinite employment after five years, while those in research-related roles (including fixed-term faculty and researchers, and lab technicians) obtain this right after ten years. The intent of this law was to secure long-term employment; however, the rule has produced an unintended consequence.Many researchers and staff are employed on time-limited grants, and universities often lack the budget to offer permanent positions. To avoid triggering the right to indefinite employment, institutions frequently terminate contracts just before the requisite five- or ten-year thresholds are reached. This deliberate non-renewal forces highly skilled personnel to leave their positions despite ongoing research needs. In many cases, the same positions are refilled with new individuals—sometimes even with the same person after a six-month “cooling-off” period—highlighting that the issue stems not from a genuine budgetary shortfall, but from a systemic workaround to evade the conversion mandate (Sasaki 2018).

The non-renewal practice adversely affects Japan’s research system: it strips individuals of job security, impairs project continuity for lab leaders, and ultimately benefits no one. Although these practices are widely criticized as being contrary to the spirit of the law—and there are instances where their legal impropriety has led to litigation—many affected employees refrain from pursuing legal action, likely due to concerns about potential negative impacts on their careers. While the indefinite-term conversion rule was designed to promote job stability, it has ironically jeopardized the careers of personnel including people engaged in scientific research, compromising the overall research activity in Japan.

9. Expansion of graduate education and the “10,000 Postdocs Project” and their consequences

In academia, it is widely believed that the deconstruction of the research ecosystem began with the “strategic focus on graduate schools” policy implemented in the 1990s (Motomura 2009). This reform involved expanding graduate education, reassigning faculty affiliations from undergraduate schools to graduate schools, and reorganizing graduate school majors—all supported by preferential government budget allocations. The shift in focus resulted in increased graduate student enrollment without a significant rise in faculty numbers, nearly doubling the student-to-faculty ratio (MEXT 2018b). Because most Ph.D. students pursued academic careers—and were not necessarily welcomed by industry (Enoki and Hamanaka 2014)—the academic job market became oversaturated with applicants (Motomura 2009).

One of the factors that worsened the academic job market for scientists in Japan was the “10,000 Postdocs Project”, introduced under the first Science and Technology Basic Plan (1995–2000)(Science and Technology Policy Symposium Executive Committee 2010). The Japanese government implemented an employment funding subsidy program aimed at doubling the number of postdoctoral fellows, more than ten thousand postdocs, to strengthen Japanese research activity. The plan assumed that a significant amount of postdoctoral fellows would make transition into industry jobs, but this expectation was not met. In reality, Japanese industries are generally reluctant to hire PhD holders who are too highly specialized and older, as they do not align well with the company’s career path system (Enoki and Hamanaka 2014). Meanwhile, job opportunities in academia remain extremely limited, as previously described. Another contributing factor is that many graduate students tend to pursue academic careers rather than industry positions. This further intensifies the competition for academic jobs, making the job market even more challenging (Kobayashi 2016). The number of postdocs were indeed nearly doubled by the plan, from 6,224 postdocs in 1996 to 11,127 in 2002 (

https://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/shingi/chukyo/chukyo4/008/gijiroku/03112101/004/009.pdf), but job opportunities did not increase for them. As a result, many postdoctoral researchers struggle to secure permanent positions and find themselves repeatedly moving from one temporary postdoc position to another as their contracts expire. This cycle has resulted in an aging postdoctoral population, with 20.7% of postdocs aged 35–39 and 16.4% over 40, out of a total of 14,237 postdoctoral fellows in the fiscal year 2012 (

https://www.nistep.go.jp/wp/wp-content/uploads/NISTEP-postdoc2012-PressJ.pdf). According to fiscal year 2021 data, of the 13,657 postdocs, 11.5% were between 40 and 44 years old, 6.8% were between 45 and 49 years old, and 11.6% were over 50, showing significant increase of aged postdocs (30% of postdocs were over the age of 40) (

https://doi.org/10.15108/rm337).

Given that Japanese science policy prioritizes the careers of young researchers, the oversupply of postdoctoral researchers produced under the 10,000-Postdocs Plan has led to increasingly limited opportunities for securing permanent academic positions as they age. Consequently, this cohort appears to have become a neglected generation. No party has assumed responsibility for the shortcomings of the 10,000 Postdocs Project. Instead, on March 26, 2024, MEXT announced a similar initiative—this time aimed at tripling the number of PhD holders—titled “Get a PhD—Doctoral Human Resources Action Plan.” The plan sets a goal of increasing the number of PhDs per one million population to one of the highest levels worldwide by 2040 (a threefold increase relative to the 2020 level). Although MEXT calls on industry to expand its recruitment of PhD holders, it remains uncertain whether industry is adequately prepared to integrate such highly qualified individuals into its workforce.

10. Decreased Number of Graduate Students, the Core Driving Force of Research

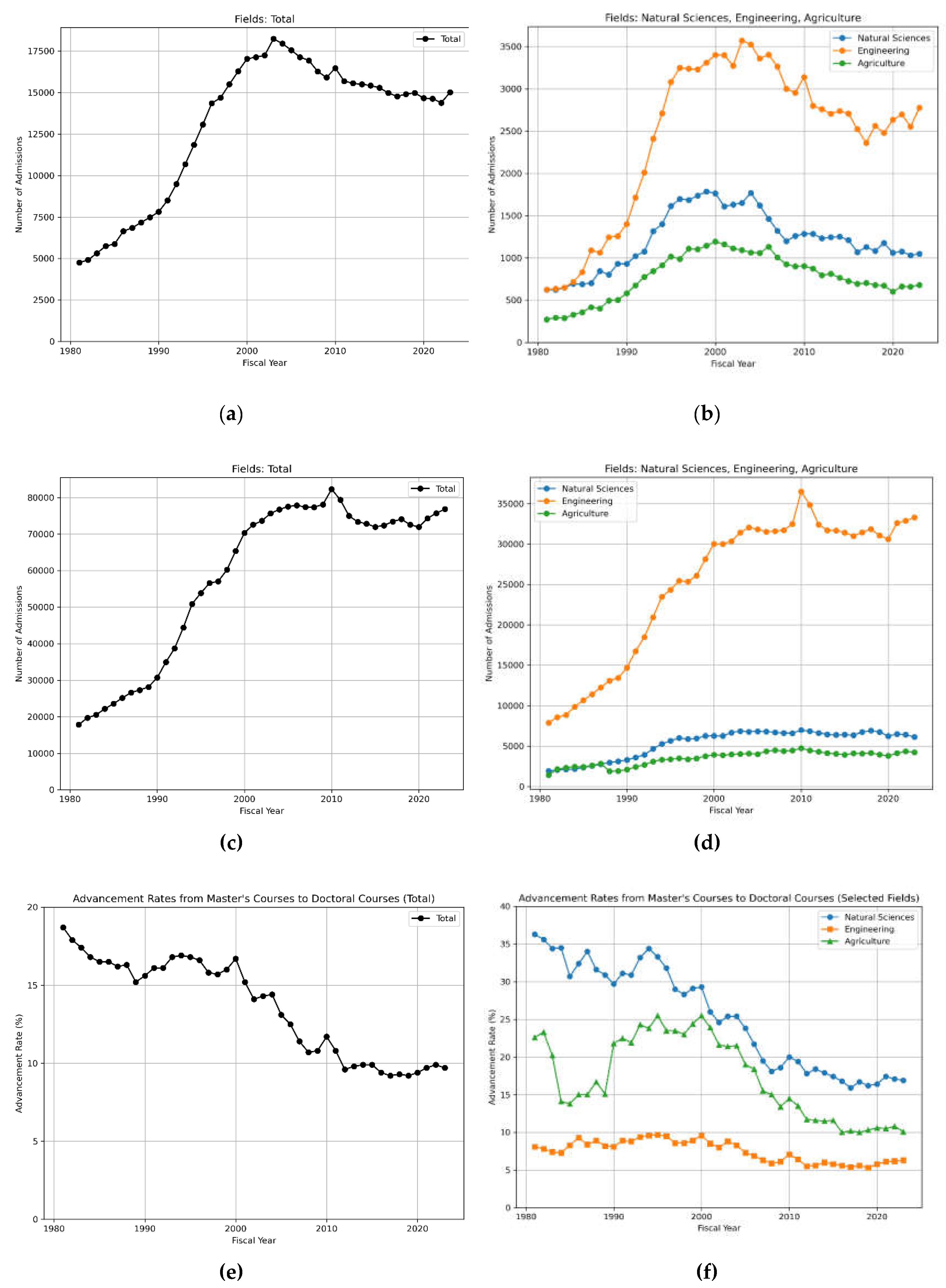

One of the significant manifestations of the decline in Japan’s research activity is the marked decrease in the number of graduate students in science and technology fields, as illustrated in

Figure 6. Since the early 2000s, the number of students enrolling in graduate programs—particularly doctoral courses—has steadily declined. One might assume that this trend could be attributed to demographic shifts, such as Japan’s declining birthrate (Yonezawa 2020). In fact, the 18-year-old population peaked at 2.05 million in 1992 and has steadily declined since then, reaching 1.09 million in 2023—a reduction of nearly half over 30 years—according to a MEXT document. (

https://www.mext.go.jp/content/20250128-mxt_koutou02-000039883_14.pdf). In contrast, the number of university entrants and the university enrollment rate have shown a steady increase over the past 30 years (

https://www.mext.go.jp/content/20240719-koutou02-000037140_14.pdf). While the number of enrollments in master's programs at graduate schools has not shown as drastic a decrease as that observed in doctoral programs, a notable trend is the significant decline in the advancement rate from master’s to doctoral programs (

Figure 6e, 6f). These statistics suggest that the declining birthrate is unlikely to be the primary cause of the trend. Rather, as discussed below, the issue lies in the diminishing motivation among undergraduate and master’s students to pursue doctoral study.

Surveys conducted by the National Institute of Science and Technology Policy (NISTEP) indicate that students forgo doctoral education primarily due to economic hardship and structural issues in the academic labor market. Key concerns include financial insecurity during graduate study, uncertainty about career prospects after obtaining a PhD, and the perception that the long-term return on investment is not justified by the limited availability of stable academic positions (Watanabe, Kawamura, and Tsuchiya 2023). These concerns are reinforced by structural trends within academia itself, including the proliferation of fixed-term contracts, limited prospects for secure academic employment, and the overall lack of sustainable career pathways for early-career researchers.

This convergence of evidence—statistical trends in enrollment, survey responses, and structural labor conditions—points to a deeper issue: the erosion of research careers as a viable and attractive option for young people. Graduate students have traditionally been the primary engine of university-based research. As their numbers decline, laboratories become underpopulated, and the cycle of scientific innovation is disrupted. Graduate schools in Japan are, in effect, becoming hollowed out—not due to a lack of capable and motivated students, but because these talented students no longer see a future in research. This situation reflects a broader structural failure in science and education policy to support and incentivize the next generation of researchers.

Thus far, we have examined issues concerning financial resources and human capital in research. Next, we turn our attention to the significant impact that university reforms and the increased ratio of competitive funding have had on the dimension of time.

11. Declining research time amid increasing administrative demands

Regarding research time, the introduction of competition among universities and the reallocation of budgets based on institutional evaluations have substantially reduced the time available for scholarly investigation. To respond to the demands of university reform, faculty members are compelled to allocate significant time to administrative tasks—such as fulfilling evaluation requirements, preparing proposal documentation, and drafting proposals for competitive funding—in addition to their educational responsibilities, rather than devoting their efforts to research. Notably, the proportion of research time among faculty across all universities declined markedly from 46.5% in 2002 to 37.2% in 2008, and, according to the available data, remained largely unchanged until 2018 (Igami and Kanda 2020). This reduction in dedicated research time underscores the urgent need to provide specialized support to help alleviate the administrative load and enable researchers to focus more effectively on their scholarly pursuits.

12. Expectation for the research administrators (URAs) for the support of researchers in academia

A shortage of dedicated time for research in universities is often cited as one of the major causes of decreased research capabilities in Japan (Toyoda 2019). University researchers are too busy with administrative tasks related to university reforms, institutional evaluations, and preparing extramural grant proposals. To reduce these administrative burdens, the role of supporting specialists—namely, University Research Administrators (URAs), a new profession introduced in 2011—has been expanded. URAs are similar to research management and administration professionals (RMAs) who work with researchers at universities in Europe and North America (Yang-Yoshihara, Poli, and Kerridge 2023). Although Japan's URA system was modeled after U.S. research administrators (Takahashi 2023), Japanese URAs are expected to work more closely with researchers to drive research development rather than merely managing research budgets, as dedicated officials already handle the administrative aspects of research expenditures (Yamano 2016). By the Japanese government's initiatives to implement URAs in academia, the number of URAs has increased significantly over the past decade, reaching 1,512 at 172 institutions in FY2022 (Takahashi and Ito 2023). Research Administration and Management in Japna (RMAN-J) , a professional organization for URA members, was established in March 2015 to support their activities and to formalize the new profession (Takahashi and Ito 2023). URAs are expected to become a catalyst for innovation in Japan (Ito 2024).

Presently, URAs are expected to fulfill a broad array of roles—including pre-award and post-award support, facilitating industry-academia collaborations, and research management (Takahashi 2016; Takahashi et al. 2018). However, for URAs to serve as the driving force in fundamentally addressing the decline in Japan's research capacity, it is desirable that they not be confined solely to an expert role but also assume positions that allow them to contribute to university management (Mitsubishi Research Institute Inc. 2017) and ultimately science and technology policy at governmental level. Enhancing their status and expanding their influence would significantly strengthen efforts to restore Japan's research capabilities.

13. Maximizing the Possibility for Innovation to Happen: Rebalancing Japan's Research Funding

In recent decades, Japan has increasingly embraced a strategy of targeted funding—concentrating national research investments in a limited number of strategic fields such as AI, quantum technology, and biotechnology (e.g., Science, Technology and Innovation Basic Plans). This approach seeks to align scientific output with national priorities and generate economic and societal impact. Indeed, some targeted programs have yielded visible successes: for example, government support played a significant role in advancing iPS cell research, which culminated in Nobel Prize-winning work and has since led to high-profile translational applications (Soma et al. 2024; Sawamoto et al. 2025). These outcomes demonstrate that targeted investment can be effective, especially when national goals are clear and long-term institutional support is provided.

However, targeted funding has its own limitations and trade-offs. Emphasizing alignment with predefined goals and short-term outcomes may constrain researchers’ flexibility and creativity. Basic science—by its very nature—requires time, tolerance for failure, and freedom from rigid performance metrics. A retrospective analysis of several Nobel Prize-winning discoveries illustrates this point vividly. Osamu Shimomura, fascinated by the chemical properties of bioluminescent proteins, identified green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a byproduct while characterizing aequorin from jellyfish (Shimomura 2005). GFP later revolutionized cell biology. Similarly, Tasuku Honjo discovered the PD-1 molecule while investigating programmed cell death, a finding that ultimately led to immune checkpoint inhibitors and transformed cancer therapy (Okazaki and Honjo 2007) Yoshizumi Ishino accidentally identified unusual repeated DNA sequences in the E. coli genome, later known as CRISPR, which laid the groundwork for genome editing technologies (Ishino, Krupovic, and Forterre 2018). Shinya Yamanaka demonstrated that terminally differentiated mammalian cells could be reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, building on John Gurdon's earlier discovery of reversible cell differentiation (Yamanaka 2020; Gurdon 1962).

These groundbreaking innovations were not the result of top-down directives but rather emerged from investigator-driven curiosity and long-term support for fundamental research. They often originated from modest laboratories without the expectation of immediate societal impact. Winning lottery tickets cannot be selectively purchased in advance; similarly, future transformative discoveries cannot be engineered solely through targeted investment.

Therefore, striking the right balance between targeted and broad-based funding is essential. While strategic investment can catalyze progress in key national areas, a healthy research environment also depends on distributed, stable support for bottom-up, curiosity-driven science. Broadly distributing small- to mid-scale grants—as demonstrated in life sciences and medicine (Ohniwa, Takeyasu, and Hibino 2023)—is more effective at promoting the emergence of new research topics than concentrating large grants among a few elite institutions. Japan’s future research policy should not pose these funding models as mutually exclusive, but rather aim to optimize their coexistence.

Rebalancing the current funding structure—by restoring baseline institutional support, invigorating small- and mid-scale competitive grants, and safeguarding academic career pathways—may help revitalize scientific creativity, sustain diverse research cultures, and secure long-term innovation capacity. Such measures are crucial to ensuring that the seeds of tomorrow's innovations, which often germinate unpredictably, are not overlooked or lost.

14. Japan’s Unique Challenges

Although this paper has focused on the unintended consequences of science policy reforms in Japan, many of the mechanisms discussed—such as fixed-term academic employment, competitive research grants, and targeted funding—are not unique to Japan. Across countries, similar policies have been implemented to enhance researcher mobility, the agility of scientific research, and alignment with national innovation goals. Fixed-term contracts are indeed common in the early stages of academic careers, such as postdoctoral positions. However, successful performance during this phase typically leads to clear advancement pathways, including tenure-track appointments or permanent academic positions (Castellacci and and Viñas-Bardolet 2021).

In contrast, Japan’s academic system structurally lacks mechanisms to ensure career continuity based on research performance, often leading to the expiration of contracts even for researchers with a strong record of academic publications, as discussed in the previous sections. While the institutional and legal frameworks themselves contribute to structural instability, immediate reform of the laws may not be feasible. Therefore, practical measures—such as enhancing research management support through the deployment of University Research Administrators (URAs)—are crucial for mitigating the negative effects within the existing system.

URAs in Japan are highly skilled professionals, often holding a Ph.D. in science, who work closely with researchers (Institute for Future Engineering 2018; Yano, Murakami, and Hayashi 2013). They help reduce administrative burdens by supporting tasks such as university evaluations, grant proposal preparation, and coordination of industry–academia collaborations.

15. Conclusion

Innovation requires a series of essential stages—from fundamental discoveries in basic science, which plant the seeds of innovation, to the development of applied research and the societal implementation of new technologies. Every stage is indispensable. However, Japan's science policy has introduced a 'selection and concentration' strategy and overemphasized competitive principles, placing disproportionate focus on later stages. As a result, increased emphasis on competitive and implementation-focused funding has undermined support for both curiosity-driven basic research and the operational infrastructure of universities. Furthermore, the introduction of fixed-term appointments for faculty at national universities has imposed excessive competitive pressures on researchers. Consequently, long-term projects have become unfeasible, and even sustaining a basic livelihood is increasingly difficult. Additionally, the demands of evaluation have further deprived researchers of the time needed to conduct meaningful research. These shifts in science policy have rendered Japan's research environment highly unstable, particularly undermining the sustainability of basic science. Although some measures—such as the introduction of research support positions (i.e., University Research Administrators, or URAs)—have been implemented, fundamental reforms are urgently needed to restore a stable research infrastructure.

Funding

This research was funded by Japan Society for Promotion of Science (JSPS), grant number KAKENHI JP20K03260 and KAKENHI JP25K06356.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Professor Hiroyasu Nakano for his encouragement. I am also grateful to the National Institute of Science and Technology Policy (NISTEP) for making well-structured public data available.

Conflicts of Interest

The author is currently employed as a University Research Administrator (URA), but declares no conflict of interest related to the content or conclusions of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GDP |

Gross Domestic Produce |

| MEXT |

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology |

| URA |

University Research Administrator |

| NISTEP |

The National Institute of Science and Technology Policy |

References

- Aagaard, Kaare, Alexander Kladakis, and Mathias Wullum Nielsen. 2019. 'Concentration or dispersal of research funding?', Quantitative Science Studies, 1: 117-49.

- Amano, Ikuo. 2006. 'Corporatization of National Universities: Current Status and Challenges (Translation of Japanese 国立大学の法人化 : 現状と課題)', Nagoya journal of higher education, 6: 147-69.

- Asahi Shimbun Investigative Team. 2024. The National Universities at the Brink: Twenty Years After Corporatization, What Is Eroding Japan’s Universities? (Translation of.

- Asia Pacific Dept International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2023. 'Structural Barriers to Wage Income Growth in Japan', IMF Staff Country Reports, 2023: A003.

- Castellacci, Fulvio, and Clara and Viñas-Bardolet. 2021. 'Permanent contracts and job satisfaction in academia: evidence from European countries', Studies in Higher Education, 46: 1866-80.

- Enoki, Eisuke, and Junko Hamanaka. 2014. 'The Reality of Underutilized Highly Educated Talent in Japan: Why Do Japanese Companies Not Recruit and Utilize PhD Holders?', Works: 6-8.

- Gokami, Makoto. 2019. The Future Landscape of Universities: Creating a Knowledge-Based Society (Translated from Japanese.

- Gurdon, J. B. 1962. 'The developmental capacity of nuclei taken from intestinal epithelium cells of feeding tadpoles', J Embryol Exp Morphol, 10: 622-40.

- Hanawa, Takeo. 2021. 'Repayment Resources of "University Bond" and Equal Opportunity of the National University Corporations in Japan ; Reviewing the Revenue Bonds of Public Universities in the United States', The annual bulletin of social science, 55: 161-78.

- Hornyak, T. 2022. ''I feel disposable': Thousands of scientists' jobs at risk in Japan', Nature.

- Igami, Masatsura. 2017. 'A consideration on the background of the recent stagnation of Japanese scientific research : Evidence from research results of the National Institute of Science and Technology Policy (NISTEP) 日本の科学研究力の停滞の背景をよむ : 科学技術・学術政策研究所の調査研究より', Kagaku, 87: 744-55.

- Igami, Masatsura, and Yumiko Kanda. 2020. "Detailed analyses on full-time equivalent R&D expenditure and the number of researchers in Japanese universities " In Technical Report. National Institute of Science and Technology Policy (NISTEP).

- ———. 2024. "Temporal Changes in R&D Expenditures at the University Faculty Level: A Trial Using the Survey of Research and Development." In NISTEP DISCUSSION PAPER. National Institute of Science and Technology Policy.

- Ikarashi, A. 2023. 'Japanese research is no longer world class - here's why', Nature, 623: 14-16.

- Institute for Future Engineering. 2018. "Report on the Survey Analysis for Quality Assurance of Research Administrators: FY 2017 MEXT Commissioned Project (Translation of 平成 29 年度文部科学省委託事業 リサーチ・アドミニストレーターの質保証に 向けた調査分析 調査報告書)." In.

- Ishino, Yoshizumi, Mart Krupovic, and Patrick Forterre. 2018. 'History of CRISPR-Cas from Encounter with a Mysterious Repeated Sequence to Genome Editing Technology', Journal of Bacteriology, 200: 10.1128/jb.00580-17.

- Ito, Takeo. 2024. 'URA as a Catalyst for Innovation in Japan : From the Case Study of Kyoto University', The journal of Information Science and Technology, 74: 22-27.

- Iwamoto, Noa. 2019 Scientists are Disappearing: Japan May No Longer Win Nobel Prizes (Translation of Japanese 科学者が消える: ノーベル賞が取れなくなる日本) (Toyo Keizai Inc.).

- Katayama, Satoshi. 2022. 'Mass Non-Renewals of Researchers and Faculty at National University Corporations and R&D Organizations (Translation of Japanese 国立大学法人,研究開発法人等における研究者,教員の大量雇止め)', Journal of Japanese Scientists, 57: 44-45.

- Kobayashi, Takehiko. 2016. 'The Postdoc Problem and Workforce Mobility: Saving Japanese Science (Translation of Japanese ポスドク問題と人材の流動化—日本のサイエンスを救うために—))', Science Portal (Japan Science and Technology Agency), Accessed 2025.02.21.

- Mainichi Shimbun Investigative Team. 2019. The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Scientific Empire.

- MEXT. 2018a. "Historical Developments and Potential Structural Causes of the Decline in Japan’s Research Capability: Document 2-2 for the 68th Meeting of the Subdivision on Science of the Council for Science and Technology, , 2018." In. 3 July.

- ———. 2018b. "Overview of the Key Developments and Structural Factors Behind Japan's Declining Research Capacity (Reference Data Collection)(Translation of Japanese 日本の研究力低下の主な経緯・構造的要因案(参考データ集))." In Materials for the 68th Academic Subcommittee Meeting, edited by Culture Ministry of Education, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT).

- ———. 2023. "The historical development of national university corporatization in Japan (Translation of Japanese 国立大学の法人化の経緯)." In.

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. 2016. Survey Report on the Promotion of Innovation Policy (Translation of Japanese イノベーション政策の推進に関する調査結果報告書) (総務省行政評価局).

- Mitsubishi Research Institute Inc. 2016. "Analysis of Government R&D Investment Target Setting and Investment Effects (Translation of Japanese)." In Investigation and Analysis Report on Policy Issues Concerning the Promotion of "Science for Policy" in Science and Technology Innovation Policies (Translation from Japanese 政府研究開発投資目標の設定・投資効果の分析 科学技術イノベーション政策における「政策のための科学」推進に関する政策課題についての調査分析). Mitsubishi Research Institute.

- ———. 2017. "Survey Report on the Challenges for Strengthening the URA System (Translation of Japanese URAシステム強化に向けた諸課題に関する調査)." In MEXT FY2016 Commissioned Project for the Development of Science and Technology Human Resources.

- Mizuta, Kensuke. 2024. 'Historical transitions in critical issues of national university corporations' finance 国立大学法人の制度・会計・財務状況に関する論点と変遷', The Doshisha business review 75: 591-627.

- Monde, Kenji. 2024. 'More Research Time for Researchers (Translation of Japanese 研究者にもっと研究時間を)', Journal of Synthetic Organic Chemistry, 82: 115-15.

- Motomura, Yukiko. 2009. 'What exactly was the strategic focus on graduate schools?', Chemistry & Chemical Industry, 62: 873-76.

- Murata, Hirofumi. 2021. 'Promoting University Bonds and Academia-Industry Collaboration: Reflections on Six Years as President of the University of Tokyo — Makoto Gonokami on the University’s Role as a Driver of Societal Transformation (Translation of Japanse 大学債発行、産学連携を推進-。総長在任6年を総括 変革期の大学の使命 東京大学総長・五神真の「大学は、社会変革を駆動する拠点として」)', Zaikai 69: 16-21.

- Nakatomi, Koichi. 2011. 'Restructuring of academic freedom in national university corporations', The quarterly of the Ritsumeikan University Law Association, 333/334: 2495-523.

- Nakayama, Reiko. 2020. ""The Corporatization of National Universities Was a Failure" — Regret Expressed by Akito Arima, Former President of the University of Tokyo and Former Minister of Education (Translation of Japanese 「国立大学法人化は失敗だった」 有馬朗人元東大総長・文相の悔恨)." In Nikkei Business.

- National Institute of Science and Technology Policy (NISTEP). 2024. "Japanese Science and Technology Indicators 2024." In.

- Ohniwa, R. L., K. Takeyasu, and A. Hibino. 2023. 'The effectiveness of Japanese public funding to generate emerging topics in life science and medicine', PLoS One, 18: e0290077.

- Okazaki, Taku, and Tasuku Honjo. 2007. 'PD-1 and PD-1 ligands: from discovery to clinical application', International Immunology, 19: 813-24.

- Omi, Koji. 1996. Fundamental Law of Science and Technology (Yomiuri Shimbun).

- Sasaki, Dan. 2018. 'The 2018 Issue at National Universities and Its Resolution: A Case Study of the University of Tokyo (Translation of Japanese 国立大学における二〇一八年問題とその解決│東京大学の事例)', The Zenei: 1-8.

- Sawamoto, Nobukatsu, Daisuke Doi, Etsuro Nakanishi, Masanori Sawamura, Takayuki Kikuchi, Hodaka Yamakado, Yosuke Taruno, Atsushi Shima, Yasutaka Fushimi, Tomohisa Okada, Tetsuhiro Kikuchi, Asuka Morizane, Satoe Hiramatsu, Takayuki Anazawa, Takero Shindo, Kentaro Ueno, Satoshi Morita, Yoshiki Arakawa, Yuji Nakamoto, Susumu Miyamoto, Ryosuke Takahashi, and Jun Takahashi. 2025. 'Phase I/II trial of iPS-cell-derived dopaminergic cells for Parkinson’s disease', Nature.

- Science and Technology Policy Symposium Executive Committee. 2010. "Recommendations for Addressing the Issues Facing Young Researchers (e.g., Postdocs)." In.

- Shimada, Shinji 2022. 'Toward the Revival of Japan as a Nation of Science and Technology - Is Japan finished?', Proceedings for The 96th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Pharmacological Society, 96: 2-B-SL09.

- Shimomura, O. 2005. 'The discovery of aequorin and green fluorescent protein', J Microsc, 217: 1-15.

- Soma, Takeshi, Yoshinori Oie, Hiroshi Takayanagi, Shoko Matsubara, Tomomi Yamada, Masaki Nomura, Yu Yoshinaga, Kazuichi Maruyama, Atsushi Watanabe, Kayo Takashima, Zaixing Mao, Andrew J. Quantock, Ryuhei Hayashi, and Kohji Nishida. 2024. 'Induced pluripotent stem-cell-derived corneal epithelium for transplant surgery: a single-arm, open-label, first-in-human interventional study in Japan', The Lancet, 404: 1929-39.

- Suda, Momoko. 2021. 'The Transformation of the “Control Tower” for Science and Technology and the Decline of Japan’s Research Capabilities (Translation of Japanese 「科学技術の司令塔」の変質と日本の研究力衰退 )', Gakujutsu no Doko 26.

- Takahashi, Makiko. 2016. 'The function of URA skill standard for unified comprehension to diversified roels of URAs and related professionals', Journal of the Japan Society for Intellectual Production, 12: 19-29.

- ———. 2023. 'Research Managers and Administrators in Asia: History and Future Expectations.' in Simon Kerridge, Susi Poli and Mariko Yang-Yoshihara (eds.), The Emerald Handbook of Research Management and Administration Around the World (Emerald Publishing Limited).

- Takahashi, Makiko, Yoko Furusawa, Kazuma Edamura, and Koichi Sumikura. 2018. "Human Resources for Research Promotion and Application in Japanese Academia -From Competition to Cooperation of University-Industry Cooperation Coordinators and University Research Administrators-." In GRIPS DISCUSSION PAPER. National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS).

- Takahashi, Makiko, and Shin Ito. 2023. 'The Profession of Research Management and Administration in Japan.' in Simon Kerridge, Susi Poli and Mariko Yang-Yoshihara (eds.), The Emerald Handbook of Research Management and Administration Around the World (Emerald Publishing Limited).

- Takeuchi, Kenta. 2019. 'The Future of Management Expense Grants for National University Corporations: Debates over Performance-Based Allocation (Translation of 国立大学法人運営費交付金の行方 : 「評価に基づく配分」をめぐって)', Legislation and Research (立法と調査): 67-76.

- The Science Council of Japan's Executive Committee. 2022. 'Statement by the Executive Board of the Science Council of Japan: Aiming to Resolve the So-Called ”Yatoi-dome”(Non-Renewal) Issue for Fixed-Term Researchers and University Faculty (Translation of Japanese 有期雇用研究者・大学教員等のいわゆる「雇止め」問題の解決を目指して)', Trends in the sciences, 27: 7-9.

- Toyoda, Nagayasu. 2019. Japan’s Crisis as a Science and Technology Powerhouse (Translation of Japanse 科学立国の危機 失速する日本の研究力) (Toyo Keizai Inc.).

- Watanabe, Chihiro, and Martin Hemmert. 1998. 'The interaction between Technology and economy.' in M. Hemmert and C. Oberländer (eds.), Technology and Innovation in Japan: Policy and Management for the Twenty-First Century (Routledge).

- Watanabe, Eiichiro, Mari Kawamura, and Takahiro Tsuchiya. 2023. "The 2021 Survey of Japan Master’s Human Resource Profiling." In NISTEP RESEARCH MATERIAL Tokyo: National Institute of Science and Technology Policy.

- Yamagiwa, Juichi, and Satoshi Fujii. 2018. 'Interview with Kyoto University President Juichi Yamagiwa: Japan’s Universities Are Being Destroyed by "Austerity" and "Reform" (Translation of Japanese 京都大学 山極寿一総長インタビュー 日本の大学は今、「緊縮」と「改革」で滅びつつある)', Criterion: 134-48.

- Yamanaka, S. 2020. 'Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Cell Therapy-Promise and Challenges', Cell Stem Cell, 27: 523-31.

- Yamano, Masahiro. 2016. 'Comparative Understanding of Change of University Research Administrators (URA) between Japan and the USA: Expansion of the Role of Research Development (RD)', The journal of management and policy in higher education: 67-82.

- Yang-Yoshihara, Mariko, Susi Poli, and Simon Kerridge. 2023. 'Evolution of Professional Identity in Research Management and Administration.' in Simon Kerridge, Susi Poli and Mariko Yang-Yoshihara (eds.), The Emerald Handbook of Research Management and Administration Around the World (Emerald Publishing Limited).

- Yano, Masaharu, Toshie Murakami, and Teruyuki Hayashi. 2013. 'The current situation and system design of research administration in Japan 我が国のリサーチ・アドミニストレーターの現状と制度設計 : 東京大学の事例を中心として', Research in higher education, 45: 83-96.

- Yonezawa, Akiyoshi. 2020. 'Challenges of the Japanese higher education Amidst population decline and globalization', Globalisation, Societies and Education, 18: 43-52.

- Yoshida, Kana. 2007. 'Chapter 10: Management Expense Grants and Independent Revenue (Translation of Japanese 第10章 運営費交付金と自己収入)..' in Kiyoshi Yamamoto (ed.), A Study on the Financial and Managerial Reforms Following the Corporatization of National Universities (Translation of Japanese 国立大学法人化後の財務・経営に関する研究). ・.

- Young Academy of Japan. 2014. "Proposal of a Methodology for Enhancing Japan's Science and Technology through Support for Early-Career Researchers and the Utilization of Research Support Personnel (Translation of Japanese 若手研究者支援・研究支援人材活用を通じた日本の科学技術を高めていく方法論の提案)." In.: Science Council of Japan.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).