Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

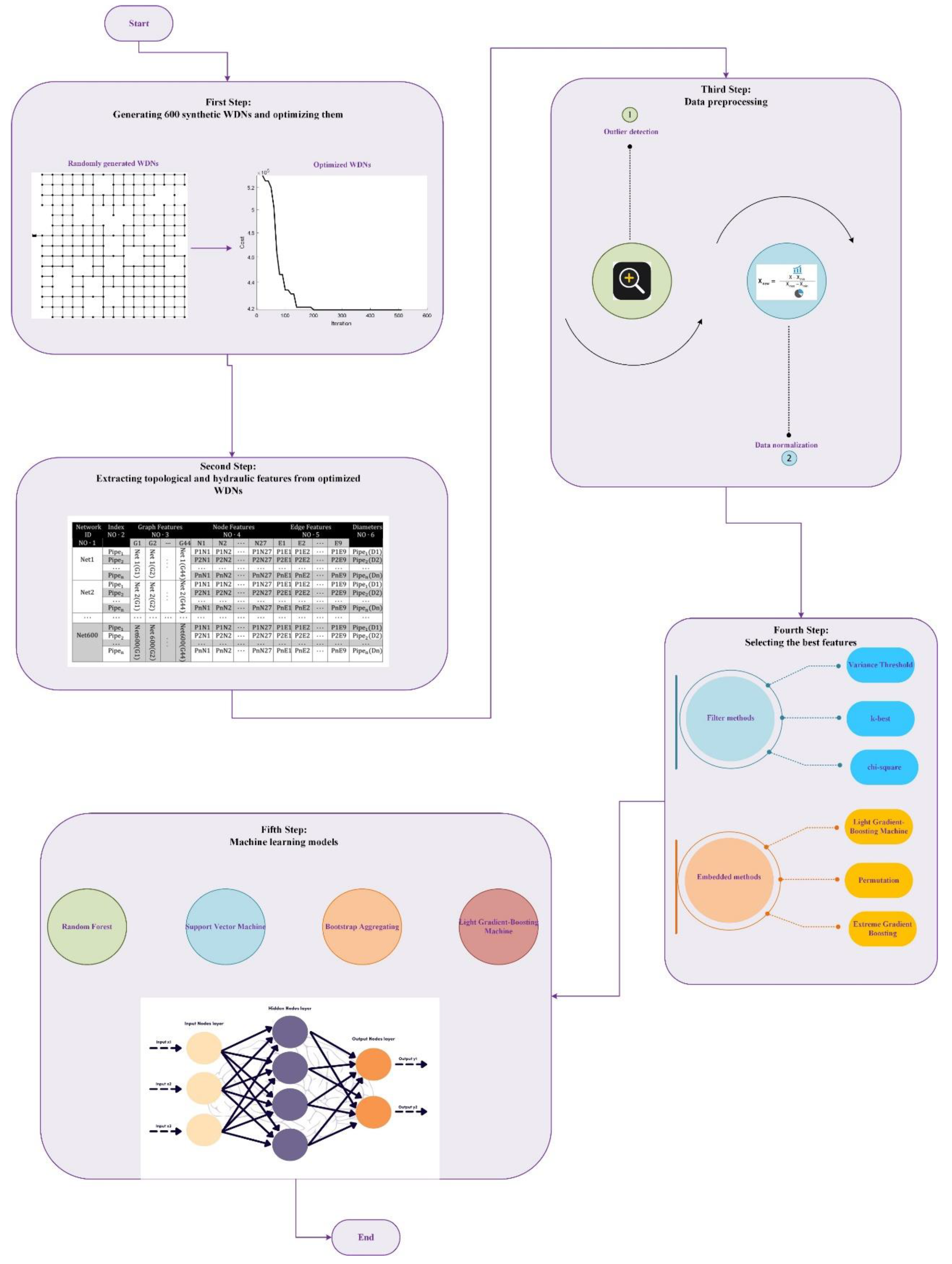

2. Methodology

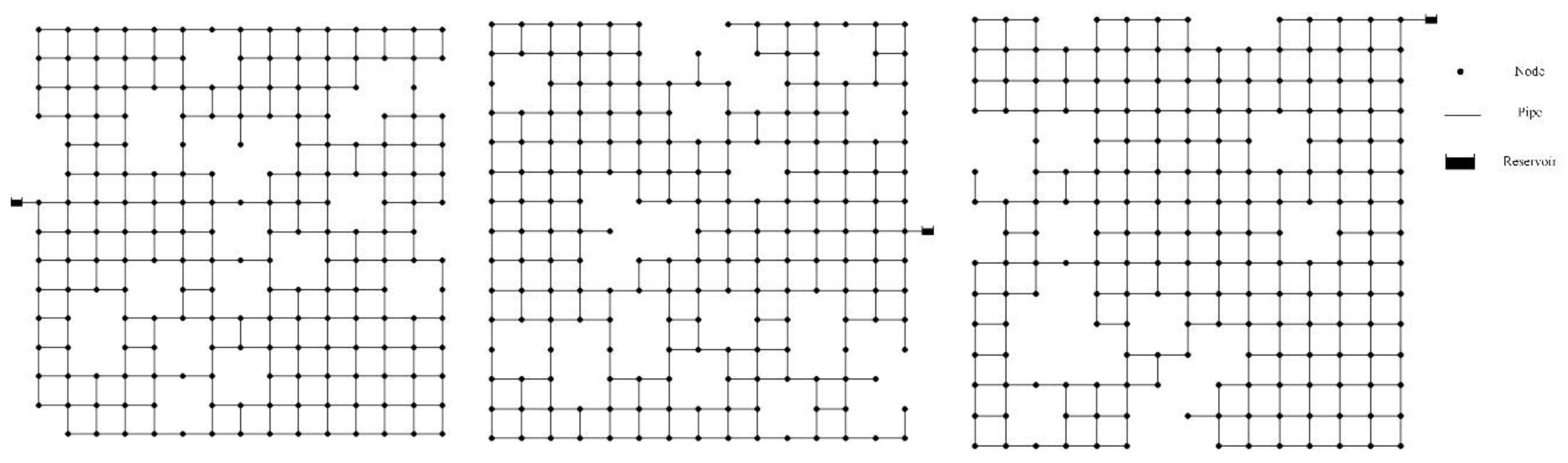

2.1. Synthetic Water Distribution Network Generation

2.2. Water Distribution Network Optimization

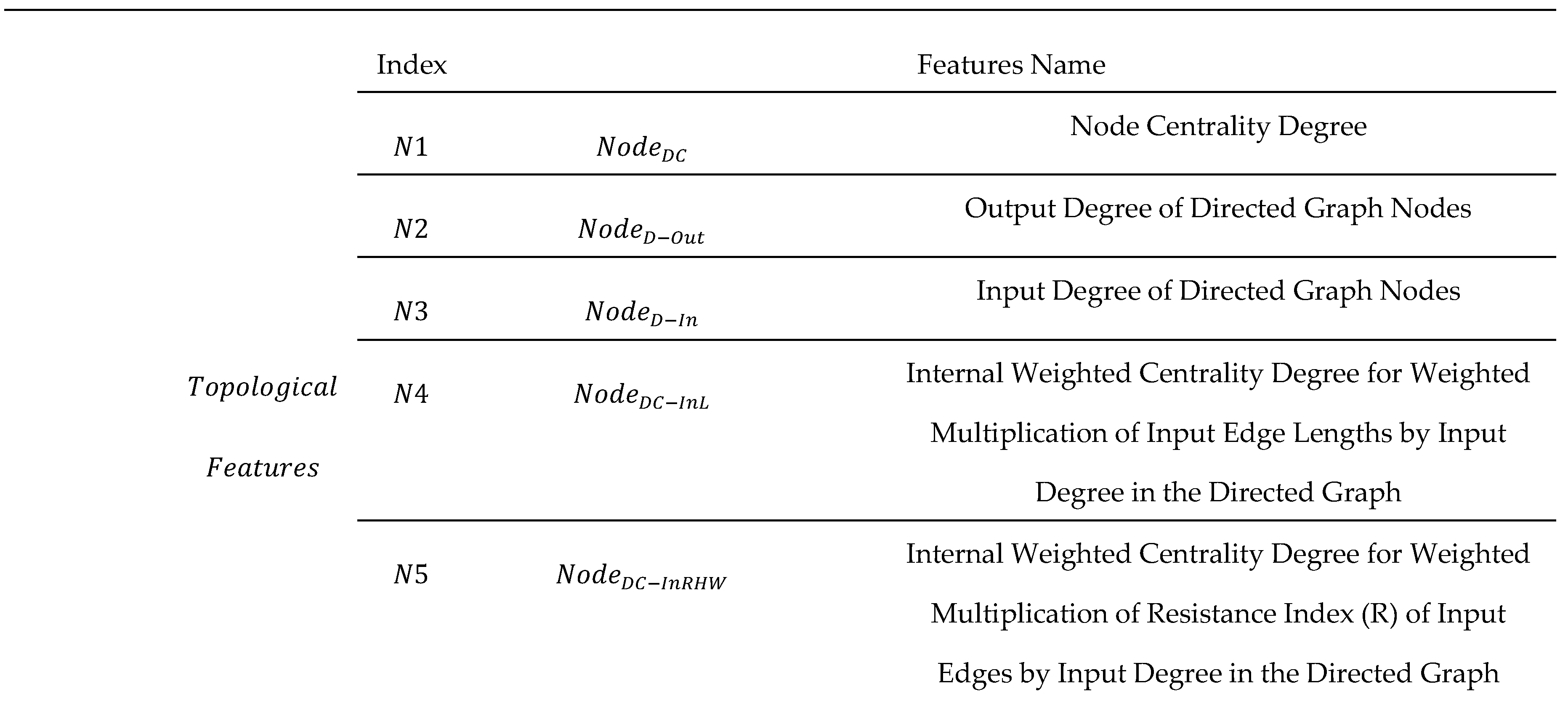

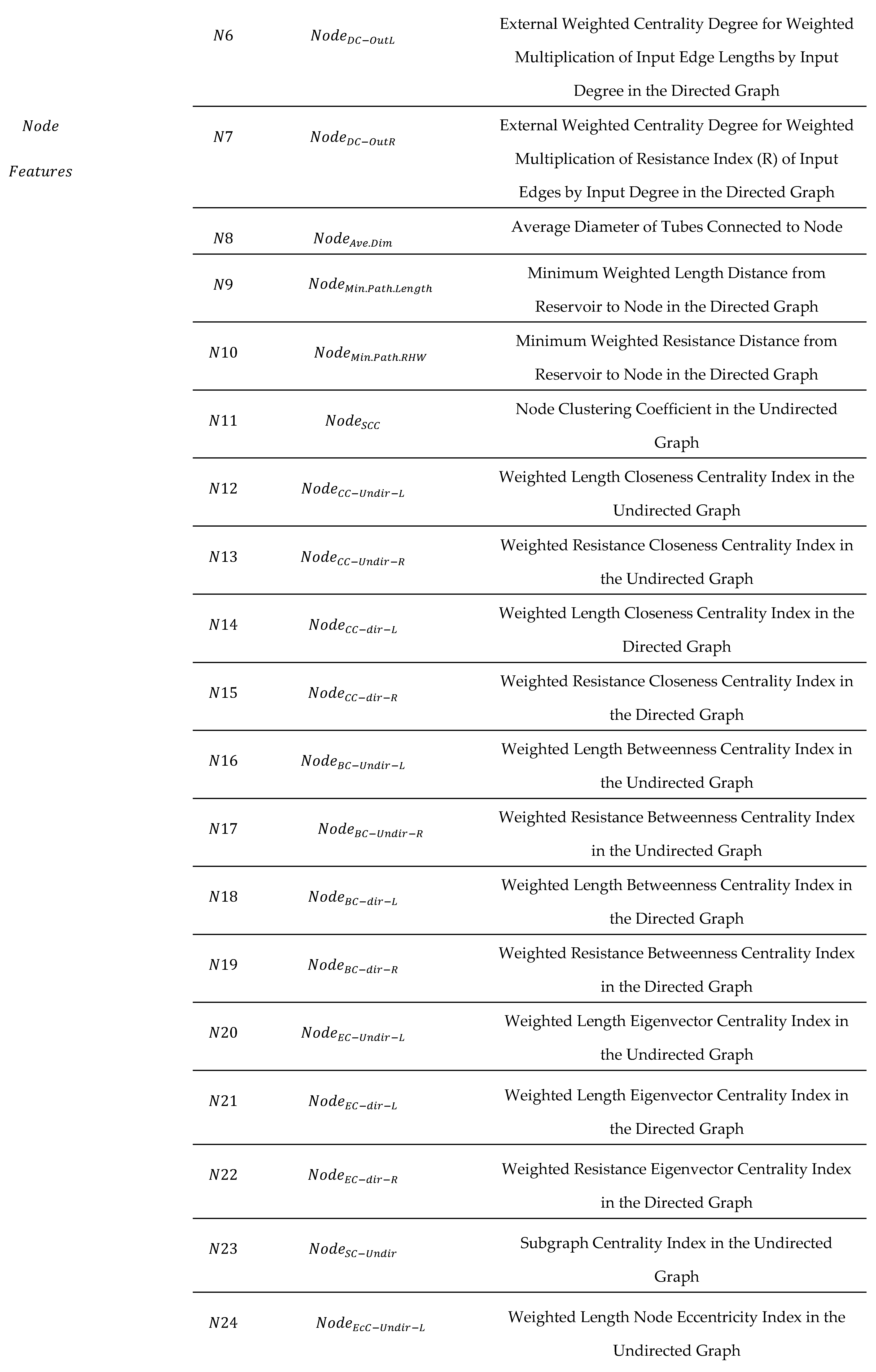

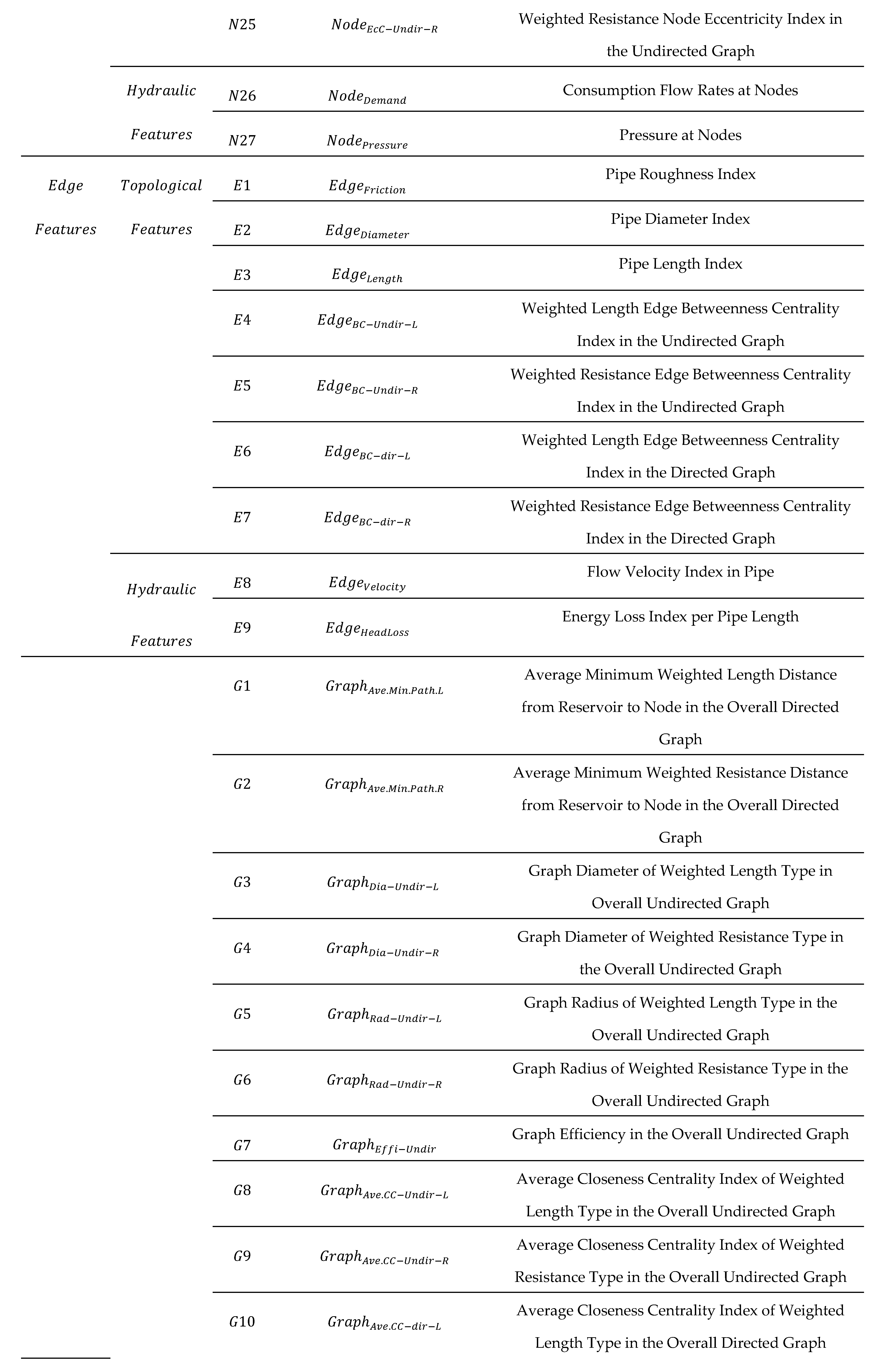

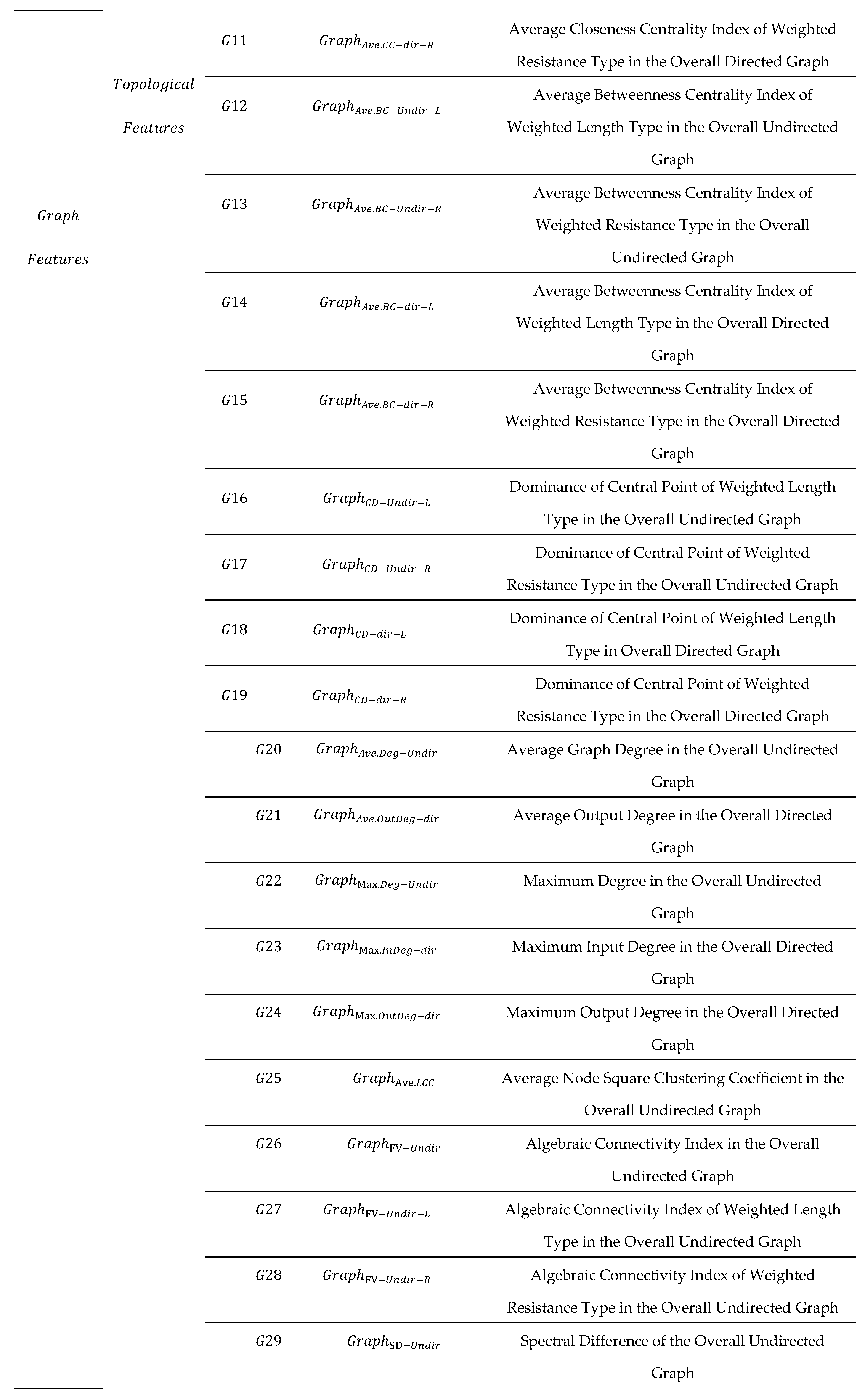

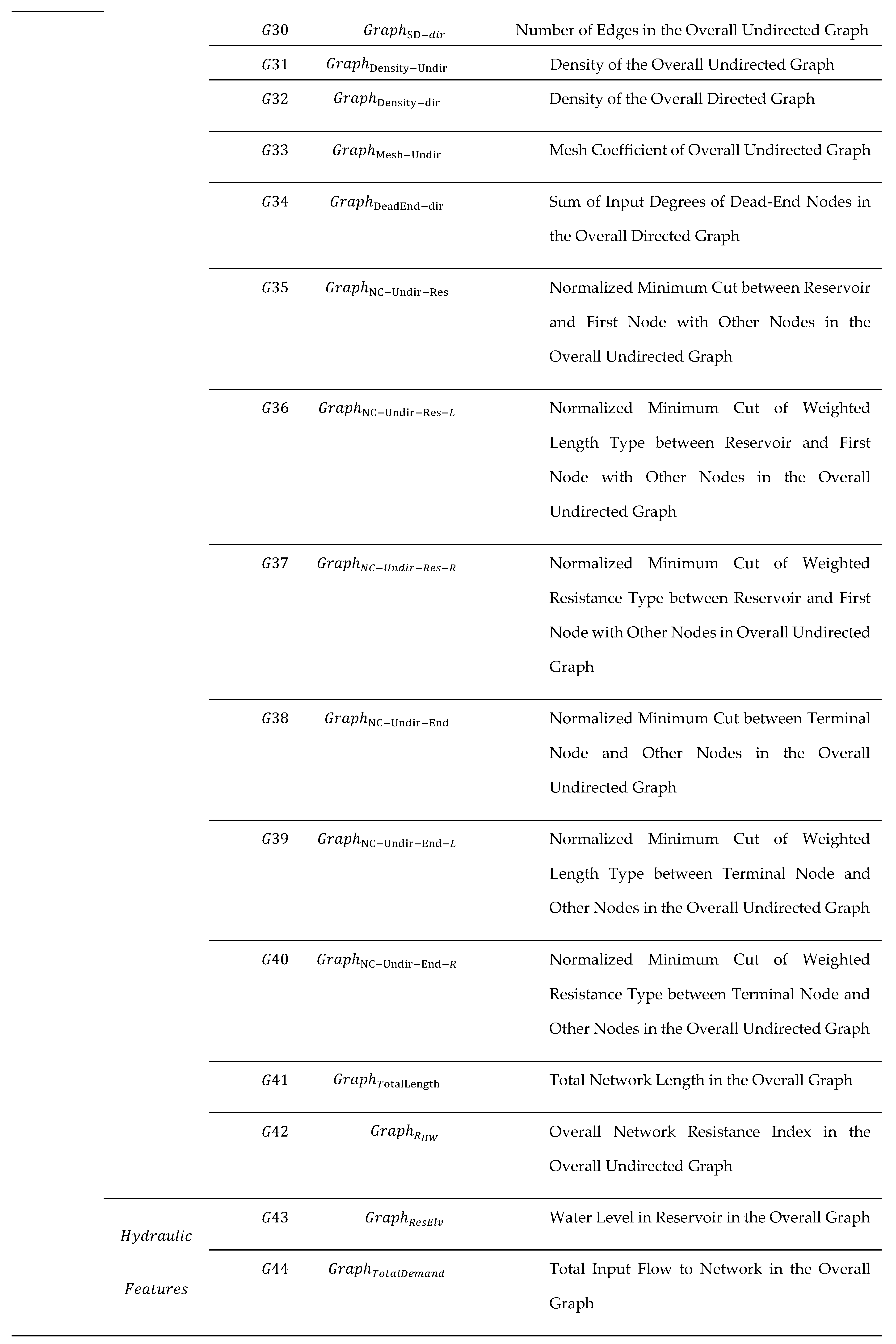

2.3. Topological and Hydraulic Features

- Node and overall network graph features are assigned to pipes.

- For each pipe, the average of features from connecting nodes is calculated and assigned as a descriptive feature.

- Features derived from the overall network graph are uniformly applied to all pipes within that network, aiding in network differentiation during the learning process.

- Undirected graphs are used for features such as square clustering coefficient, node eccentricity, and pipe length index.

- Directed graphs are necessary for features like degree of centrality and shortest path from the reservoir to nodes.

- Some features, including node closeness centrality index and betweenness centrality indices, require examination of both directed and undirected graphs.

- R = Pipe resistance

- = Pipe length

- C = Hazen-Williams coefficient

- = Pipe diameter

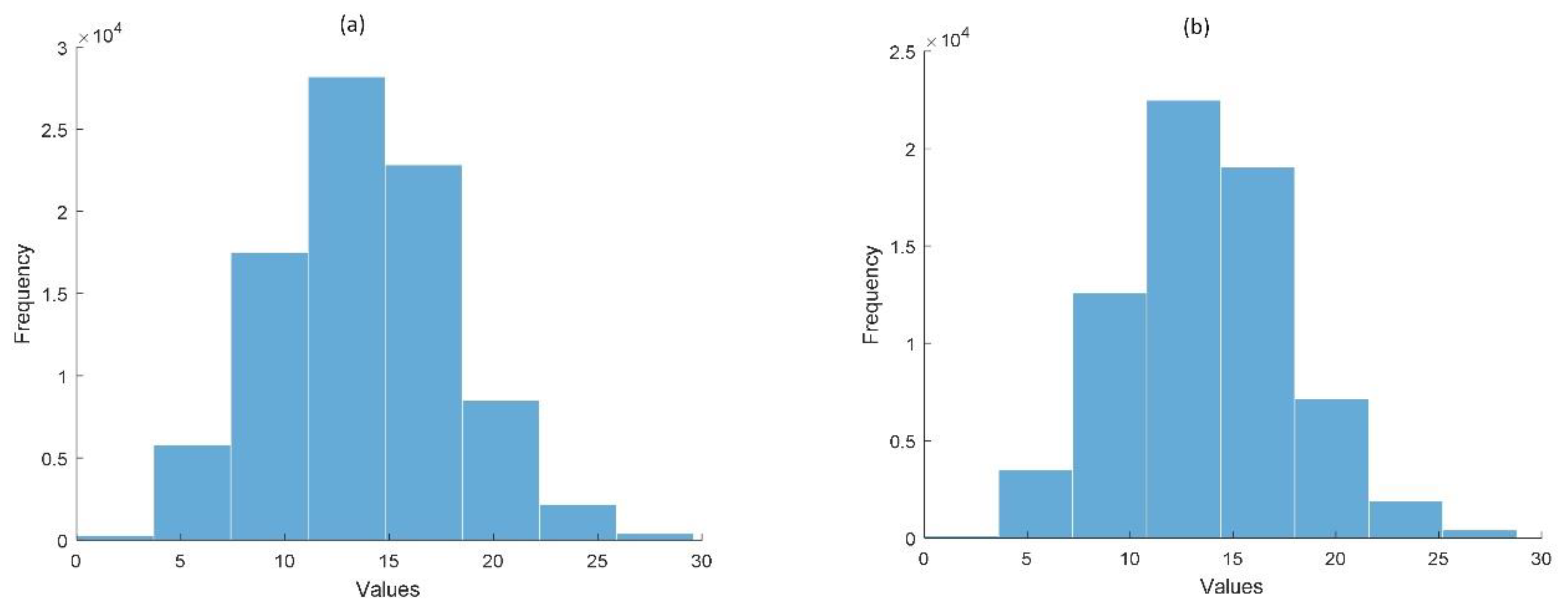

2.4. Database Preparation

- Outlier Data Detection: Identifying and handling outliers is crucial as these anomalous values can significantly impact model training, reducing accuracy and generalizability. In this study outliers are defined as data points that differ by more than four times the standard deviation from the mean of the same data set. Once identified, outliers are removed from the final database.

- Data Normalization: Normalization is performed using the Min-max normalization method. This step is vital for (1) aligning features with different scales, and (2) preventing disproportionate impact of varying value ranges (e.g., pipe lengths vs. node pressures) on machine learning model performance.

2.5. Feature Selection Methods

- 1.

- Chi2

- 2.

- Var

- 3.

- Kb

- 4.

- LGB

- 5.

- Per

- 6.

- Xg

2.6. Machine Learning Models

2.6.1. Regression in Machine Learning

- 1.

- Random Forest (RF)

- 2.

- SVM

- 3.

- BAG

- 4.

- LGB

2.6.2. Model Evaluation

- : The real value of the objective variable.

- : The predicted value of objective variable.

- : The mean value of objective variable.

- : The total number of samples.

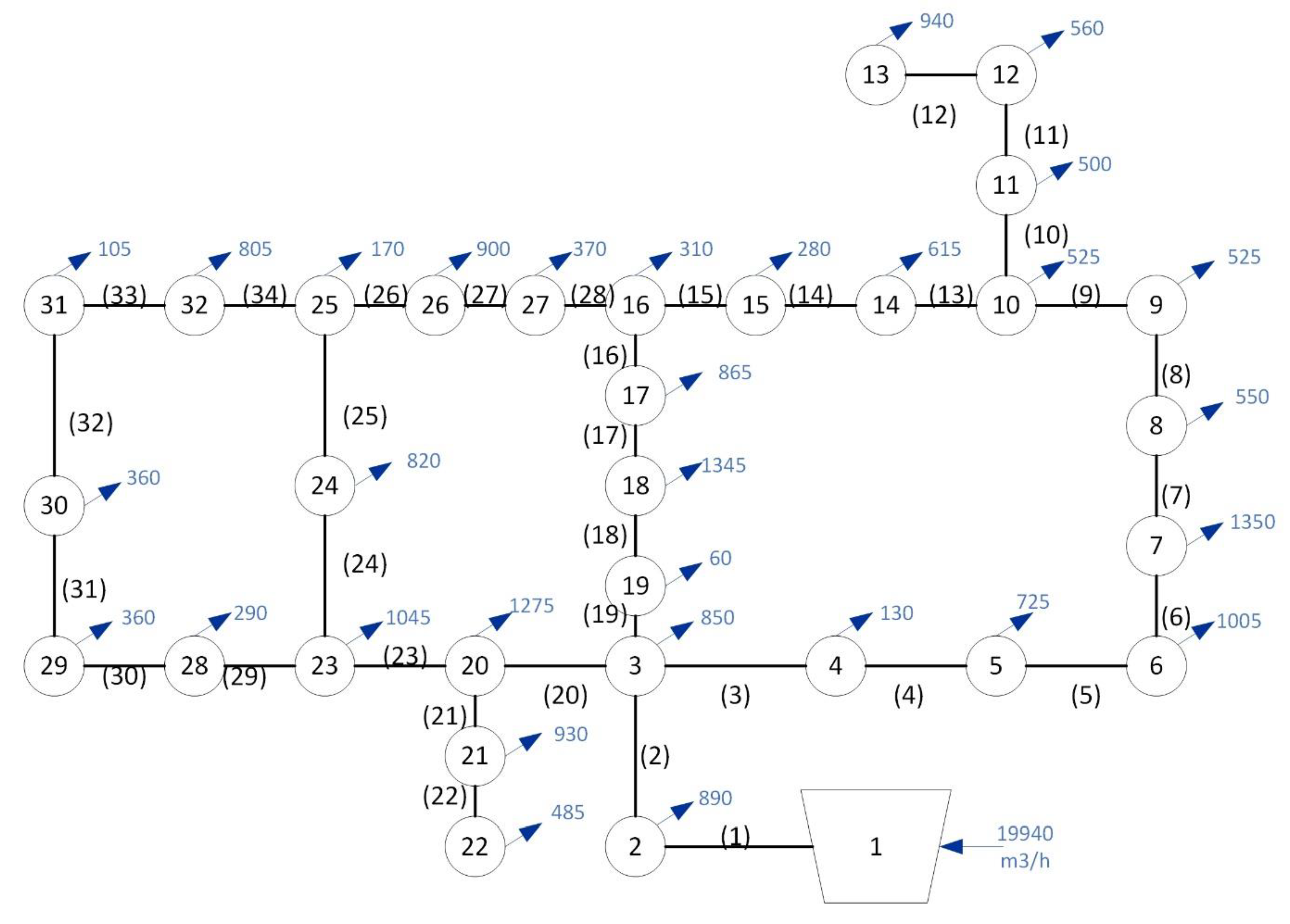

2.6.3. Hanoi WDN

- Minimum pressure head at demand nodes: 30 meters

- Hazen-Williams coefficient for all pipes: 130

3. Results and Discussion

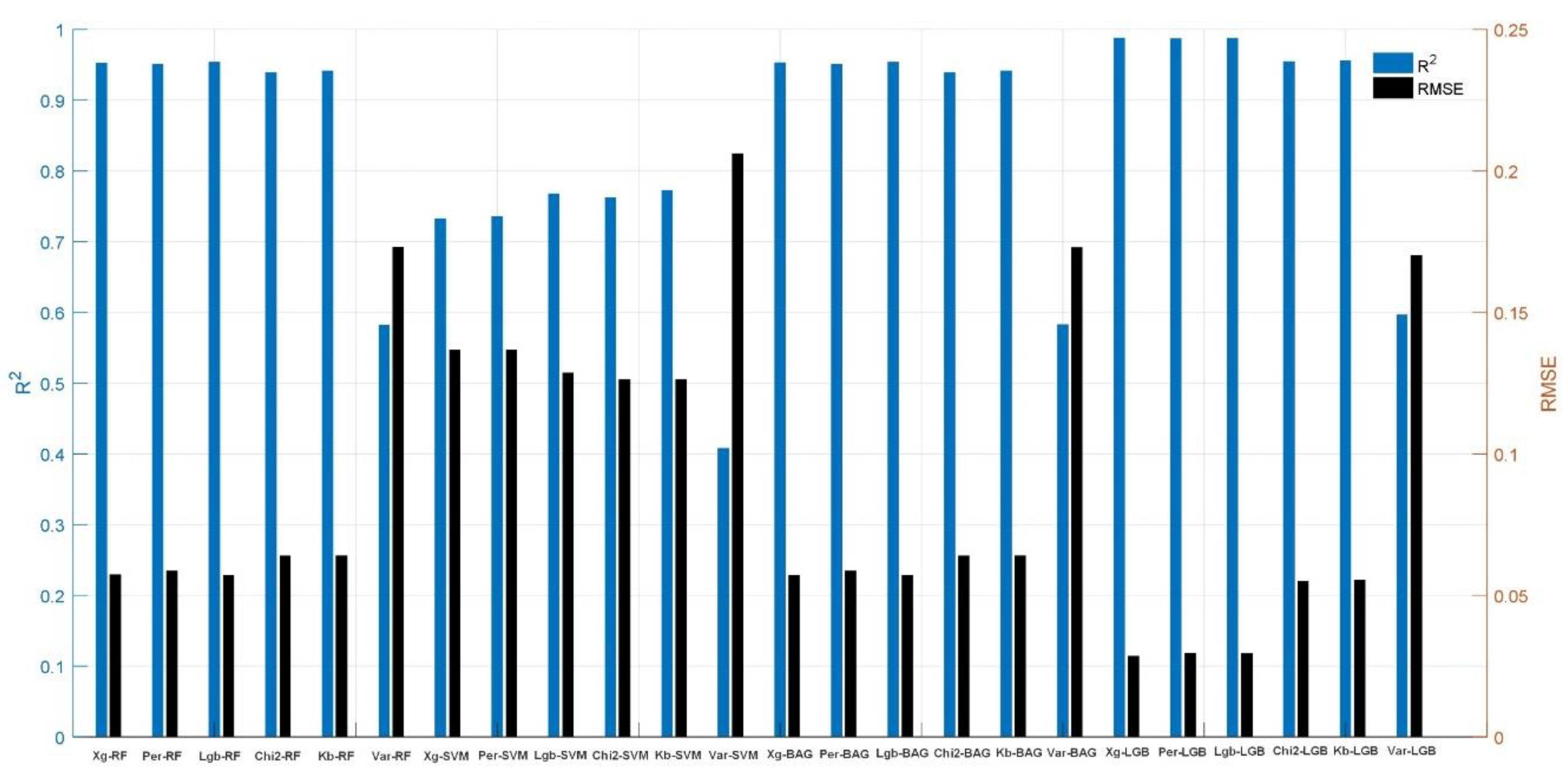

- Node-related features dominate in four methods (Xg, Per, LGB, and Chi2)

- Overall network graph properties are most prominent in two methods (Kb and Var)

- N5 and N7 (weighted node centrality degrees) consistently appear in the top quartile for most methods, except Var

- Features using pipe resistance (R) as a weighted criterion show greater importance than those using pipe length

- Node features: 50% on average

- Pipe features: 26% on average

- Graph features: 24% on average

- Filter methods (e.g., Kb and Var) tend to select more overall network graph features

- Embedded methods (e.g., Xg, Per, LGB) primarily select node and pipe features

- Top features from each selection method are paired with corresponding optimal diameters

- These feature sets are used as inputs for four machine learning models

- Hyperparameters for each model are optimized using the Grid search algorithm (detailed in Table 7)

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Appendix A

References

- Ahmed, A. A.; Sayed, S.; Abdoulhalik, A.; Moutari, S.; Oyedele, L. Applications of machine learning to water resources management: A review of present status and future opportunities. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 140715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsahaf, A.; Petkov, N.; Shenoy, V.; Azzopardi, G. A framework for feature selection through boosting. Expert Systems with Applications 2022, 187, 115895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, A.; Toloşi, L.; Sander, O.; Lengauer, T. Permutation importance: a corrected feature importance measure. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amali, S.; Faddouli, N.E.E.; Boutoulout, A. Machine learning and graph theory to optimize drinking water. Procedia Computer Science 2018, 127, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsene, C.T.; Gabrys, B.; Al-Dabass, D. Decision support system for water distribution systems based on neural networks and graphs theory for leakage detection. Expert Systems with Applications 2012, 39, 13214–13224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Hur, A.; Weston, J. A user’s guide to support vector machines. Data mining techniques for the life sciences 2010, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondy, J.A.; Murty, U. S. R 1976. GRAPH THEORY WITH APPLICATIONS. Elsevier Science Publishing Co.; Inc. 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10017.

- Breiman, L. Bagging Predictors. Machine Learning 1996, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forest. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, G.; Sahin, F. A survey on feature selection methods. Computers & electrical engineering 2014, 40, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. Journal of artificial intelligence research 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.Y.J.; Guikema, S.D. Prediction of water main failures with the spatial clustering of breaks. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2020, 203, 107108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Li, J. Optimal sensor placement for leak location in water distribution networks: A feature selection method combined with graph signal processing. Water research, 2023, 242, 120313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.; Austin, M.A.; Mishra, S.; Blackburn, M. Teaching Machines to Understand Urban Networks: A Graph Autoencoder Approach. International Journal on Advances in Networks and Services 2020, 13, 70–81. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348992449.

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creaco, E.; Franchini, M. Low Level Hybrid Procedure for the Multi-Objective Design of Water Distribution Networks. Procedia Engineering 2014, 70, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, A.; Cutler, D.R.; Stevens, J.R. Random forests. Ensemble machine learning: Methods and applications 2012, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desyani, T.; Saifudin, A.; Yulianti, Y. Feature selection based on naive bayes for caesarean section prediction. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2020, 879, 012091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuerlein, J. W. Decomposition model of a general water supply network graph. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 2008, 134, 822–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nardo, A.; Di Natale, M.; Giudicianni, C.; Musmarra, D.; Santonastaso, G.F.; Simone, A. Water distribution system clustering and partitioning based on social network algorithms. Procedia Engineering 2015, 119, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nardo, A.; Giudicianni, C.; Greco, R.; Herrera, M.; Santonastaso, G.F. Applications of graph spectral techniques to water distribution network management. Water 2018, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, N.; Mays, L. W.; Lansey, K. E. Optimal Reliability-Based Design of Pumping and Distribution Systems. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 1990, 116, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmani, R.; Walters, G. A.; Savic, D. A. Trade-Off Between Total Cost and Reliability for Anytown Water Distribution Network. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 2005, 131, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmani, R.; Walters, G.; Savic, D. Evolutionary Multi-Objective Optimization of the Design and Operation of Water Distribution Network: Total Cost Vs. Reliability Vs. Water Quality. Journal of Hydroinformatics 2006, 8, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fida, M.A.F.A.; Ahmad, T.; Ntahobari, M. October. Variance threshold as early screening to Boruta feature selection for intrusion detection system. 2021 13th International Conference on Information & Communication Technology and System (ICTS); 2021; pp. 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, O.; Khang, D.B. A two-phase decomposition method for optimal design of looped water distribution networks. Water Resour Res 1990, 26, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, D.P.; Thool, R.C. February. Intrusion detection system using bagging ensemble method of machine learning. 2015 international conference on computing communication control and automation; 2015; pp. 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudicianni, C.; Nardo, A.; Oliva, G.; Scala, A.; Herrera, M. A Dimensionality-Reduction Strategy to Compute Shortest Paths in Urban Water Networks. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammatopoulou, M.; Kanellopoulos, A.; Vamvoudakis, K.G.; Lau, N. A Multi-step and Resilient Predictive Q-learning Algorithm for IoT with Human Operators in the Loop: A Case Study in Water Supply Networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.03899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, I. Linear Programming Analysis of a Water Supply System. AIIE Transactions 1969, 1, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon, I.; Elisseeff, A. An introduction to variable and feature selection. Journal of machine learning research 2003, 3, 1157–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Hamam, Y.M.; Brameller, A. Hybrid method for the solution of piping networks. Proc. of the IEEE 1971, 118, 1607–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Pei, J.; Kamber, M. Data mining: Concepts and techniques; Elsevier, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Han, R.; Liu, J.; Spectral clustering and genetic algorithm for design of district metered areas in water distribution systems. Procedia Engineering 2017, 186, 152–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.03.221. Hsieh, C.P.; Chen, Y.T.; Beh, W.K.; Wu, A.Y.A 2019, October. Feature selection framework for XGBoost based on electrodermal activity in stress detection. In 2019 IEEE International Workshop on Signal Processing Systems (SiPS).; 330-335. IEEE. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/SiPS47522.2019.9020321.

- Hua, Y. An efficient traffic classification scheme using embedded feature selection and lightgbm. 2020 Information Communication Technologies Conference (ICTC); 2020; pp. 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Injadat, M. N.; Moubayed, A.; Nassif, A.B.; Shami, A. Systematic Ensemble Model Selection Approach for Educational Data Mining. Knowledge-Based Systems 2020, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.; Yoo, D.; Kang, D.; Kim, J. Linear model for estimating water distribution system reliability. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management. ASCE 2016, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadu, MS.; Gupta, R.; Bhave, PR. Optimal design of water networks using a modified genetic algorithm with reduction in search space. J Water Resour Plan Manage 2008, 134, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Park, Y.J.; Lee, J.; Wang, S.H.; Eom, D.S. Novel leakage detection by ensemble CNN-SVM and graph-based localization in water distribution systems. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2017, 65, 4279–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmeli, D.; Gadish, Y.; Meyers, S. Design of Optimal Water Distribution Networks. Journal of the Pipeline Division 1968, 94, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.Y. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Kesavan, H.K.; Chandrashekar, M. Graph theoretic models for pipe network analysis. J. Hydraul. Div 1972, 98, 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomytska, I.; Bazylevych, I.; Teslyuk, V.; Karamysheva, I. The chi-square test and data clustering combined for author identification. 2023 IEEE 18th International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technologies (CSIT); 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutner, M. H.; Nachtsheim, C. J.; Neter, J. Applied Linear Statistical Models, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakou, M.S.; Demetriades, M.; Vrachimis, S.G.; Eliades, D.G.; Polycarpou, M.M. EPyT: An EPANET-Python Toolkit for Smart Water Network Simulations. Journal of Open Source Software 2023, 8(92), 5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Setiono, R. Chi2: Feature selection and discretization of numeric attributes. Proceedings of 7th IEEE international conference on tools with artificial intelligence; 1995; pp. 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liy-González, P.-A.; Santos-Ruiz, I.; Delgado-Aguiñaga, J.-A.; Navarro-Díaz, A.; López-Estrada, F.-R.; Gómez-Peñate, S. Pressure interpolation in water distribution networks by using Gaussian processes: Application to leak diagnosis. MDPI Water 2024, 12, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaremi, Y.; Haghighi, A.; Ghafouri, H. R. Optimization of Pump Scheduling Program in Water Supply Systems Using a Self-Adaptive NSGA-II; a Review of Theory to Real Application. Water Resour Manage 2017, 31, 1283–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L. J.; Simpson, A. R. Pipe Optimisation Using Genetic Algorithms. Research Report No. R93. Department of Civil Engineering, University of Adelaide. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ostfeld, A. Water distribution systems connectivity analysis. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 2005, 131, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, T. D.; Park, N. S. Multiobjective Genetic Algorithms for Design of Water Distribution Networks. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 2004, 130, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, E.; Ostfeld, A. Graph theory modeling approach for optimal operation of water distribution systems. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 2016, 142, 04015061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, E.; Ostfeld, A. Optimal pump scheduling in water distribution systems using graph theory under hydraulic and chlorine constraints. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2016, 142, 04016037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, P.; Boulesteix, A.-L.; Bischl, B. Tunability: Importance of Hyperparameters of Machine Learning Algorithms. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2018, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeswaran, A.; Narasimhan, S.; Narasimhan, S. Graph Partitioning Algorithm for Leak Detection in Water Distribution Networks. J.Computers and Chemical Engineering 2018, 108, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyahi, M.M.; Rahmanshahi, M.; Ranginkaman, M.H. Frequency domain analysis of transient flow in pipelines; application of the genetic programming to reduce the linearization errors. Journal of Hydraulic Structures 2018, 4, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyahi, M. M.; Bakhshipour, A. E.; Haghighi, A. Probabilistic Warm Solutions-Based Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithm, Application in Optimal Design of Water Distribution Networks. Sustainable Cities and Society 2023, 91, 104424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyahi, M.M.; Bakhshipour, A.E.; Giudicianni, C.; Dittmer, U.; Haghighi, A.; Creaco, E. An Analytical Solution for the Hydraulics of Looped Pipe Networks. Engineering Proceedings 2024, 69, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyahi, M.M.; Giudicianni, C.; Haghighi, A.; Creaco, E. Coupled multi-objective optimization of water distribution network design and partitioning: a spectral graph-theory approach. Urban Water Journal 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert Messenger, R.; and Lewis Mandell, L. A Modal Search Technique for Predictibe Nominal Scale Multivariate Analys. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1972, 768–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossman, L.A.; Woo, H.; Tryby, M.; Shang, F.; Janke, R.; Haxton, T. EPANET 2.2 User Manual; Water Infrastructure Division. Center for Environmental Solutions and Emergency Response, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Samani, H. M.; Taghi, S. Optimization of Water Distribution Networks. Journal of Hydraulic Research 1996, 34, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savic, D. A.; Walters, G., A. Genetic Algorithms for Least-Cost Design of Water Distribution Networks. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 1997, 123, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaake, J. C., Jr; Lai, D. Linear Programming and Dynamic Programming Application to Water Distribution Network Design. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Department of Civil Engineering: M.I.T. Hydrodynamics Laboratory 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Schapire, R.E. The strength of weak learnability. Machine Learning 1990, 5, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholkopf, B.; Smola, A.J. Learning with kernels: support vector machines, regularization, optimization, and beyond; MIT press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, A. R.; Dandy, G. C.; Murphy, L. J. Genetic Algorithms Compared to Other Techniques for Pipe Optimization. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 1994, 120, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y. C.; Mays, L. W.; Duan, N.; Lansey, K. E. Reliability-Based Optimization Model for Water Distribution Systems. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 1987, 113, 1539–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamee, P.K.; Sharma, A.K. Design of Water Supply Pipe Networks; John Wiley: New Jersey, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todini, E. Looped Water Distribution Networks Design Using a Resilience Index Based Heuristic Approach. Urban Water 2000, 2, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuysuzoglu, G.; Birant, D. Enhanced Bagging (eBagging): A Novel Approach for Ensemble Learning. The International Arab Journal of Information Technology 2020, 17, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzatchkov, V.G.; Alcocer-Yamanaka, V.H.; Bourguett Ortíz, V. Graph Theory Based Algorithms for Water Distribution Network Sectorization Projects. In Water Distribution Systems Analysis Symposium; American Society of Civil Engineers: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2016; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulanicki, B.; Zehnpfund, A.; Martinez, F. Simplification of water distribution network models. in Proc.; 2nd Int. Conf. on Hydroinformatics. Balkema Rotterdam, Netherlands.;, 493–500. 1996. [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, A.-J.; Stoianov, I.; Chazerain, A. Hydraulically informed graph theoretic measure of link criticality for the resilience analysis of water distribution networks. Applied network science 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapnik, V. The nature of statistical learning theory. Springer science & business media. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, B.; Anuradha, J. A review of feature selection and its methods. Cybernetics and information technologies 2019, 19, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Wang, S.; Shi, M.; Xia, Q.; Jin, W. Research on partition strategy of an urban water supply network based on optimized hierarchical clustering algorithm. Water Supply 2022, 22, 4387–4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Shami, A. On Hyperparameter Optimization of Machine Learning Algorithms: Theory and Practice. Neurocomputing 2020, 415, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, A.; Jeffrey, P. Robustness and vulnerability analysis of water distribution networks using graph theoretic and complex network principles. Water Distribution Systems Analysis 2010, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, A.; Otoo, R.A.; Jeffrey, P. Resilience enhancing expansion strategies for water distribution systems: A network theory approach. Environmental Modelling and Software 2011, 26, 1574–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Liu, C.; Zemiti, N.; Yang, C. Optimal feature selection for EMG-based finger force estimation using LightGBM model. 2019 28th IEEE international conference on robot and human interactive communication (RO-MAN); 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, A.; Casari, A. Feature engineering for machine learning: Principles and Techniques for Data Scientists; O'Reilly Media, Inc., 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Diameter (mm) |

Cost of pipes (€) |

| 16 | 10.34 |

| 20 | 11.18 |

| 25 | 12.22 |

| 32 | 13.69 |

| 40 | 15.36 |

| 50 | 17.45 |

| 63 | 20.17 |

| 75 | 22.67 |

| 90 | 25.81 |

| 110 | 30.89 |

| 125 | 35.38 |

| 160 | 48.84 |

| 200 | 66.80 |

| 250 | 95.25 |

| 315 | 141.83 |

| 400 | 216.60 |

| 500 | 327.50 |

| 600 | 438.40 |

| 800 | 660.20 |

| 1000 | 882.00 |

| Network ID NO.1 |

Index NO.2 |

Graph Features NO.3 |

Node Features NO.4 |

Edge Features NO.5 |

Diameters NO.6 |

|||||||||

| G1 | G2 | … | G44 | N1 | N2 | … | N27 | E1 | E2 | … | E9 | |||

| Net 1 | Pipe1 | Net 1(G1) | Net 1(G2) | … | Net 1(G44) | P1N1 | P1N2 | … | P1N27 | P1E1 | P1E2 | … | P1E9 | Pipe1(D1) |

| Pipe2 | P2N1 | P2N2 | … | P2N27 | P2E1 | P2E2 | … | P2E9 | Pipe2(D2) | |||||

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | |||||

| Pipen | PnN1 | PnN2 | … | PnN27 | PnE1 | PnE2 | … | PnE9 | Pipen(Dn) | |||||

| Net 2 | Pipe1 | Net 2(G1) | Net 2(G2) | … | Net 2(G44) | P1N1 | P1N2 | … | P1N27 | P1E1 | P1E2 | … | P1E9 | Pipe1(D1) |

| Pipe2 | P2N1 | P2N2 | … | P2N27 | P2E1 | P2E2 | … | P2E9 | Pipe2(D2) | |||||

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | |||||

| Pipen | PnN1 | PnN2 | … | PnN27 | PnE1 | PnE2 | … | PnE9 | Pipen(Dn) | |||||

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Net 600 | Pipe1 | Net 600(G1) | Net 600(G2) | … | Net 600(G44) | P1N1 | P1N2 | … | P1N27 | P1E1 | P1E2 | … | P1E9 | Pipe1(D1) |

| Pipe2 | P2N1 | P2N2 | … | P2N27 | P2E1 | P2E2 | … | P2E9 | Pipe2(D2) | |||||

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | |||||

| Pipen | PnN1 | PnN2 | … | PnN27 | PnE1 | PnE2 | … | PnE9 | Pipen(Dn) | |||||

| Index | Graph Features | Node Features | Edge Features | Diameters (mm) |

|||||||||

| G1 | G2 | … | G44 | N1 | N2 | … | N27 | E1 | E3 | … | E9 | ||

| 0 | 379 | 407 | … | 3749 | 2.50 | 0.50 | … | 11.80 | 87 | 31 | … | 0.01 | 200 |

| 1 | 379 | 407 | … | 3749 | 2.50 | 1.00 | … | 11.90 | 108 | 71 | … | 0.00 | 600 |

| 2 | 379 | 407 | … | 3749 | 3.50 | 1.50 | … | 13.70 | 112 | 94 | … | 0.04 | 125 |

| 3 | 379 | 407 | … | 3749 | 3.00 | 1.00 | … | 11.90 | 112 | 22 | … | 0.00 | 500 |

| 4 | 379 | 407 | … | 3749 | 3.50 | 1.50 | … | 14.20 | 111 | 23 | … | 0.20 | 200 |

| 5 | 379 | 407 | … | 3749 | 2.50 | 1.00 | … | 15.20 | 114 | 29 | … | 0.22 | 50 |

| 6 | 379 | 407 | … | 3749 | 3.00 | 1.50 | … | 18.70 | 111 | 21 | … | 0.03 | 160 |

| 7 | 379 | 407 | … | 3749 | 3.00 | 1.50 | … | 18.90 | 111 | 22 | … | 0.00 | 800 |

| 8 | 379 | 407 | … | 3749 | 2.50 | 1.50 | … | 18.70 | 96 | 92 | … | 0.00 | 400 |

| 9 | 379 | 407 | … | 3749 | 3.50 | 2.00 | … | 18.50 | 96 | 78 | … | 0.00 | 315 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| 85735 | 484 | 507 | … | 3672 | 3.00 | 0.50 | … | 28.80 | 120 | 46 | … | 0.00 | 250 |

| 85736 | 484 | 507 | … | 3672 | 3.00 | 1.50 | … | 36.50 | 118 | 54 | … | 0.30 | 40 |

| 85737 | 484 | 507 | … | 3672 | 3.00 | 1.50 | … | 45.00 | 106 | 63 | … | 0.03 | 250 |

| 85738 | 484 | 507 | … | 3672 | 3.00 | 1.00 | … | 46.30 | 87 | 38 | … | 0.02 | 315 |

| 85739 | 484 | 507 | … | 3672 | 3.00 | 1.50 | … | 52.20 | 88 | 49 | … | 0.22 | 90 |

| 85740 | 484 | 507 | … | 3672 | 3.00 | 1.50 | … | 58.80 | 91 | 40 | … | 0.06 | 315 |

| 85741 | 484 | 507 | … | 3672 | 3.00 | 1.50 | … | 63.80 | 92 | 89 | … | 0.08 | 315 |

| 85742 | 484 | 507 | … | 3672 | 3.00 | 2.00 | … | 68.20 | 83 | 45 | … | 0.03 | 1000 |

| 85743 | 484 | 507 | … | 3672 | 3.00 | 2.00 | … | 70.20 | 90 | 35 | … | 0.01 | 800 |

| 85744 | 484 | 507 | … | 3672 | 2.00 | 1.50 | … | 35.80 | 89 | 63 | … | 0.09 | 800 |

| Index | Graph Features | Node Features | Edge Features | Diameters (mm) |

|||||||||

| G1 | G2 | … | G44 | N1 | N2 | … | N27 | E1 | E3 | … | E9 | ||

| 0 | 0.23 | 0.04 | … | 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.00 | … | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.14 | … | 0.01 | 0.19 |

| 1 | 0.23 | 0.04 | … | 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.20 | … | 0.14 | 0.70 | 0.64 | … | 0.00 | 0.59 |

| 2 | 0.23 | 0.04 | … | 0.41 | 0.75 | 0.40 | … | 0.16 | 0.80 | 0.92 | … | 0.07 | 0.11 |

| 3 | 0.23 | 0.04 | … | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.20 | … | 0.14 | 0.80 | 0.02 | … | 0.00 | 0.49 |

| 4 | 0.23 | 0.04 | … | 0.41 | 0.75 | 0.40 | … | 0.16 | 0.77 | 0.04 | … | 0.38 | 0.19 |

| 5 | 0.23 | 0.04 | … | 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.20 | … | 0.17 | 0.85 | 0.11 | … | 0.44 | 0.03 |

| 6 | 0.23 | 0.04 | … | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.40 | … | 0.22 | 0.77 | 0.01 | … | 0.06 | 0.15 |

| 7 | 0.23 | 0.04 | … | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.40 | … | 0.22 | 0.77 | 0.02 | … | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| 8 | 0.23 | 0.04 | … | 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.40 | … | 0.22 | 0.40 | 0.90 | … | 0.01 | 0.39 |

| 9 | 0.23 | 0.04 | … | 0.41 | 0.75 | 0.60 | … | 0.21 | 0.40 | 0.73 | … | 0.00 | 0.30 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| 85736 | 0.55 | 0.05 | … | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.40 | … | 0.42 | 0.95 | 0.42 | … | 0.56 | 0.02 |

| 85737 | 0.55 | 0.05 | … | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.40 | … | 0.52 | 0.65 | 0.54 | … | 0.06 | 0.24 |

| 85738 | 0.55 | 0.05 | … | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.20 | … | 0.54 | 0.17 | 0.22 | … | 0.04 | 0.30 |

| 85739 | 0.55 | 0.05 | … | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.40 | … | 0.61 | 0.20 | 0.36 | … | 0.44 | 0.07 |

| 85740 | 0.55 | 0.05 | … | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.40 | … | 0.68 | 0.27 | 0.25 | … | 0.12 | 0.30 |

| 85741 | 0.55 | 0.05 | … | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.40 | … | 0.74 | 0.30 | 0.86 | … | 0.17 | 0.30 |

| 85743 | 0.55 | 0.05 | … | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.60 | … | 0.82 | 0.25 | 0.19 | … | 0.15 | 0.80 |

| 85744 | 0.55 | 0.05 | … | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.40 | … | 0.41 | 0.22 | 0.54 | … | 0.17 | 0.80 |

| Hyperparameter Tuning with Grid search | Embedded Methods | ||

| Xg | LGB | Per | |

| n-estimators | 1350 | 1500 | 1500 |

| eta | 0.250 | - | - |

| gamma | 0.002 | - | - |

| Max-depth | 15 | 12 | 12 |

| Num-leaves | - | 45 | 45 |

| Learning-rate | - | 0.011 | 0.011 |

|

Methods Selected Features |

Kb | Chi2 | Var | LGB | Per | Xg | ||||||

| N5 | N5 | E1 | E9 | N5 | E9 | |||||||

| N7 | N7 | E3 | E8 | N7 | N5 | |||||||

| E5 | E5 | G43 | N5 | E3 | E8 | |||||||

| N8 | N8 | G44 | N7 | E9 | N7 | |||||||

| E9 | N17 | G7 | E3 | E1 | E1 | |||||||

| E3 | E9 | G20 | E1 | E5 | E3 | |||||||

| E1 | N15 | G21 | N8 | E8 | N8 | |||||||

| G42 | N19 | G23 | E5 | N8 | N10 | |||||||

| N23 | E8 | G30 | N10 | N10 | E5 | |||||||

| G12 | N18 | G31 | N6 | N6 | N6 | |||||||

| G8 | N2 | G32 | N4 | N3 | N26 | |||||||

| G4 | N10 | G35 | N17 | N17 | N4 | |||||||

| G17 | N3 | G36 | N26 | N1 | E6 | |||||||

| G13 | N13 | G39 | E4 | N23 | E7 | |||||||

| G10 | N6 | G41 | N19 | N25 | N17 | |||||||

| G41 | E3 | N1 | N9 | N4 | N20 | |||||||

| G6 | N4 | N2 | E6 | G25 | N15 | |||||||

| G18 | N14 | N5 | N18 | G3 | E4 | |||||||

| G27 | N22 | N7 | E7 | G2 | N9 | |||||||

| G2 | E1 | N23 | N20 | G10 | N19 | |||||||

| Node features percentage | 20 | 75 | 25 | 60 | 55 | 60 | ||||||

| Pipe features percentage | 20 | 25 | 10 | 40 | 25 | 40 | ||||||

| Over all graph features percentage | 60 | 0.0 | 65 | 0.0 | 20 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Hyperparameter tuning with Grid search | Ensemble model | |||

| RF | SVM | BAG | LGB | |

| n-estimators | 250 | - | 140 | 1500 |

| Max-depth | 30 | - | - | - |

| Min-samples-split | 10 | - | - | 12 |

| Max-samples | - | - | 0.7000 | - |

| Max-features | - | - | 0.7500 | - |

| C | - | 1.0000 | - | - |

| kernel | - | ‘ rbf ‘ | - | - |

| gamma | - | - | 0.0001 | - |

| Num-leaves | - | - | - | 45 |

| Learning-rate | - | - | - | 0.0110 |

| Pipe number | Predicted diameters | Node number | Pressure head from Xg-LGB model (m) | ||

| Pipe diameters from Kadu et al. (2008) (in) |

Continuous pipe diameters from Xg-LGB model (in) |

Commercial pipe diameters from Xg-LGB model (in) |

|||

| 1 | 40 | 38.9 | 40 | 1 | 100.00 |

| 2 | 40 | 36.9 | 40 | 2 | 97.14 |

| 3 | 40 | 40.7 | 40 | 3 | 61.67 |

| 4 | 40 | 40.3 | 40 | 4 | 57.39 |

| 5 | 40 | 39.9 | 40 | 5 | 52.09 |

| 6 | 40 | 39.5 | 40 | 6 | 46.56 |

| 7 | 40 | 39.1 | 40 | 7 | 45.29 |

| 8 | 40 | 40.0 | 40 | 8 | 43.83 |

| 9 | 30 | 33.7 | 30 | 9 | 42.69 |

| 10 | 30 | 35.4 | 40 | 10 | 39.40 |

| 11 | 30 | 34.9 | 30 | 11 | 39.01 |

| 12 | 24 | 27.4 | 30 | 12 | 37.85 |

| 13 | 16 | 18.2 | 20 | 13 | 36.44 |

| 14 | 12 | 14.0 | 16 | 14 | 37.81 |

| 15 | 12 | 13.0 | 12 | 15 | 37.66 |

| 16 | 16 | 18.4 | 20 | 16 | 38.17 |

| 17 | 20 | 22.1 | 24 | 17 | 45.01 |

| 18 | 24 | 24.4 | 24 | 18 | 51.52 |

| 19 | 24 | 28.2 | 30 | 19 | 60.16 |

| 20 | 40 | 40.0 | 40 | 20 | 51.41 |

| 21 | 20 | 23.4 | 24 | 21 | 47.56 |

| 22 | 12 | 13.1 | 12 | 22 | 42.40 |

| 23 | 40 | 39.2 | 40 | 23 | 45.98 |

| 24 | 30 | 34.6 | 30 | 24 | 41.44 |

| 25 | 30 | 34.4 | 30 | 25 | 38.72 |

| 26 | 20 | 21.4 | 20 | 26 | 36.67 |

| 27 | 12 | 14.1 | 16 | 27 | 36.69 |

| 28 | 12 | 14.6 | 16 | 28 | 39.30 |

| 29 | 16 | 17.6 | 16 | 29 | 36.26 |

| 30 | 12 | 14.5 | 16 | 30 | 36.26 |

| 31 | 12 | 13.0 | 12 | 31 | 36.47 |

| 32 | 16 | 17.6 | 16 | 32 | 36.74 |

| 33 | 20 | 23.9 | 24 | ||

| 34 | 24 | 26.8 | 24 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).