1. Introduction

Job satisfaction reflects an employee’s overall attitude towards their job, including their feelings about various aspects of the job or an emotional response defining the degree to which people like their jobs, which may range from extreme satisfaction to extreme dissatisfaction [

1]. It significantly influences job performance, commitment, absenteeism, retention, and turnover rates, with dissatisfied health workers often seeking employment out of their specialty [

2,

3,

4].

Health workers are the cornerstone of effective health systems, playing a pivotal role in achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and delivering quality primary health care (PHC) [

5]. In Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), job satisfaction among health workers has been identified as a key determinant of their performance, retention, and overall productivity [

6] (Measurement of Job Satisfaction among Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-sectional Study, n.d.) [

8]. This is because a satisfied workforce is more likely to provide better patient care, foster trust and ensure continuity of care within communities. The significance of job satisfaction has garnered increasing attention, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where healthcare systems face numerous challenges, including workforce shortages and high turnover rates. Improving health workforce job satisfaction in resource-limited settings is essential for addressing systemic health challenges and ensuring the sustainability of health services.

Globally, job satisfaction among healthcare workers is influenced by a complex interplay of factors such as working conditions, organizational environment, job stress, role conflict and ambiguity, role perception and content, and organizational and professional commitment [

9]. Studies have consistently shown that factors such as fair remuneration, supportive supervision, adequate resources, and opportunities for career advancement are strongly associated with higher levels of job satisfaction [

10]. Recent Gallup statistics on job satisfaction indicated that a substantial proportion of the world’s 1 billion full-time workers are disengaged and experiencing declining overall wellbeing. Specifically, 41% of employees are stressed, 1 in 5 are lonely, half are watching for or actively seeking a new job and one in four experience burnouts either "very often" or "always" [

11]. Europeans are unhappier with their workplaces than workers in any other region, with only 14% of European employees engaged at work, a figure that is seven percentage points lower than the global average (21%) and nineteen (19) points lower than the U.S. and Canada (33%) " [

11].

The African context presents unique challenges to health worker job satisfaction. Frequent infectious disease outbreaks place significant strain on already overburdened healthcare system impacting workers well-being [

12,

13]. Poorly equipped facilities, limited access to essential medicines and supplies, and inadequate infrastructure such as electricity and water, further hinder job satisfaction [

14]. In addition, many African countries face severe workforce shortages, leading to heavy workloads and burnout. While low salaries, lack of benefits, lack of recognition and unsafe working environments drive high attrition rates [

15,

16].Despite these challenges, Africa presents various opportunities that can be harnessed. There is notable willingness among health workers to further develop skills and knowledge, proactive search of solutions to enhance stock-outs of drugs and other medical devices, and motivational factors to improve the quality of care [

15]. Non-financial incentives and human resources management tools play an important role in motivating health professionals. Acknowledging their professionalism and addressing professional goals such as career development, recognition and further qualification can uphold and strengthen the professional ethos of health workers [

17].

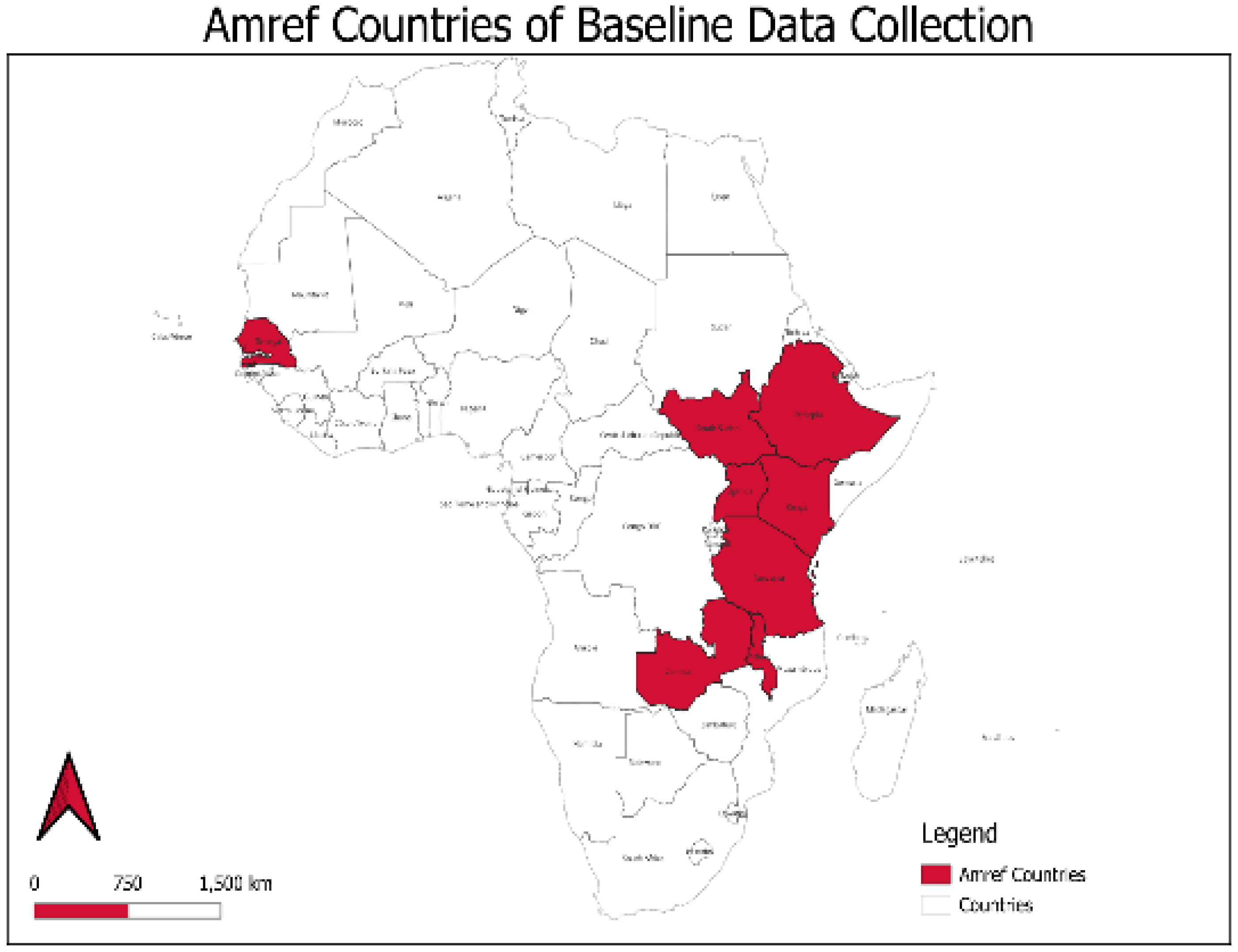

Between March and August 2023, a baseline evaluation was conducted across eight African Countries where Amref Health Africa implements its programs: Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Senegal, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. The baseline aimed to inform key strategic directions, including strengthening a fit-for-purpose health workforce for improved skills and productivity. This paper documents the levels and predictors of job satisfaction among health workers in primary healthcare settings across these eight countries.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The baseline evaluation employed a cross-sectional study design with quantitative methods to assess job satisfaction across five dimensions: employee-employer relationships, remuneration and recognition, professional development, physical environment and facilities, and supportive supervision.

Study Sites

This study presents findings from eight African countries- Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Senegal, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia, where Amref Health Africa implements health programs.

Figure 1 shows the geographical locations of these countries.

In Ethiopia, data was collected from four regional states- Oromia, Amhara, Afar, South Ethiopia regional States and Addis Ababa city administration. The country’s health workforce heavily relies on Health Extension Workers (HEWs), who form the backbone of its primary healthcare system by delivering essential services at the community level, particularly in preventive and promotive care. This program has significantly enhanced access to basic healthcare in rural areas. Ethiopia prioritizes primary healthcare with a strong emphasis on disease prevention and community-based interventions [

18,

19]. However, challenges include a shortage of trained healthcare professionals, uneven distribution of workers between urban and rural areas, limited professional development opportunities and a high population-to-health-worker ratio, all of which strain the system and impact job satisfaction and service delivery [

20].

In Kenya, the study was conducted in eight counties- Nairobi, Narok, Vihiga, Siaya, Nyeri, West Pokot, Samburu and Tharaka Nithi. These counties were purposively selected to represent diverse geographical settings, including urban, rural, arid and semi-arid regions, and to address unique Primary Health Care (PHC) challenges and the presence of Amref Health Africa programs. Kenya operates a decentralized healthcare system, with county governments playing a central role in service delivery [

21]. The country has a diverse health workforce, including doctors, nurses, clinical officers and community health volunteers (CHVs), but faces inequitable distribution, particularly in rural and marginalized areas. A robust private health sector creates competitive opportunities, often contributing to attrition in the public sector. Despite the government investments in human resources for health, such as expanding training institutions, and increasing healthcare worker training in rural areas, challenges remain in absorbing trained professionals into the workforce, leading to unemployment among qualified health workers [

22].

In Uganda, data was collected from five districts of Iganga, Mayuge, Bugiri, Namayinga and Pader. Like Kenya, Uganda operates a decentralized health system with a strong focus on community-based healthcare delivery [

21]. The country has made progress in addressing workforce shortages by scaling up training programs, particularly for frontline health workers, to improve the detection, reporting and response to disease epidemics [

23]. However, significant challenges persist, including widespread workforce shortages, high absenteeism rates, and limited access to essential medical supplies, all of which negatively impact job satisfaction [

24]. To address these issues, Uganda has adopted task-shifting strategies, enabling community health workers (CHWs) to take on expanded roles in healthcare delivery [

25,

26].

Tanzania’s health workforce emphasizes task sharing and integrating CHWs to address acute shortages of skilled professionals [

26]. The government has prioritized workforce development in its national strategies but challenges persist, particularly in rural areas. Issues such as low salaries, limited opportunities for promotion and career development, and inadequate training programs negatively affect workforce morale and retention [

27]. While decentralization of health services has improved community access, it has also increased administrative burdens on health workers. Data was collected from nine regions of Morogoro, Tanga, Mara, Songwe, Lindi, Tabora, Singida, Kaskazini Unguja and Kaskazini Pemba.

In Malawi, data was collected from six districts- Mchinji, Chitipa, Karonga, Salima, Mangochi and Chikwawa. The country has one of the world’s lowest health worker densities, with critical shortages of skilled professionals such as doctors and nurses [

28]. To address this, the government introduced initiatives like the Emergency Human Resources Program to increase workforce numbers and improve distribution. However, low salaries, heavy workloads, and limited access to essential equipment and supplies continue to undermine job satisfaction. International aid and partnerships, including support from the UK Department for International Development (DfID) and Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), play a vital role in training and retaining health workers [

29].

In Zambia, data was collected from four provinces and districts- Central (Kabwe), Copperbelt (Kitwe), Luapula (Mwense) and Eastern (Sinda). The country’s health workforce has grown due to increased investments in training institutions and partnerships with global health initiatives. However, high attrition rates remain a challenge, particularly in rural and remote areas. Contributing factors include inadequate remuneration, limited career advancement opportunities, and insufficient infrastructure. The introduction of community health assistants has been a significant innovation, extending care to underserved areas and alleviating the workload of formal health workers.

South Sudan faces some of the most severe health workforce challenges globally due to conflict and limited infrastructure. The health workforce is small, with most of the health facilities functional as a result of donor funding (World Health Organization, 2024). Frequent insecurity disrupts service delivery and deters workers from remaining in the profession [

30]. Despite these challenges, there is growing international support to train health workers locally and build capacity for a resilient health system. Data was collected from five states and counties- Warrap (Twic East, Tonj South), Western Bahr el Ghazal (Wau), Eastern (Kapoeta South), Central Equatoria (Juba and Kajokeji), and Western Equatoria (Yambio, Maridi, and Nzara).

In Senegal, data was collected from five districts- Kolda, Sédhiou, Goudomp, Matam, Guédiawaye. The expanding health infrastructure in Senegal has been accompanied by a growing health workforce, which is attributed to reinforced training programs that built on the national training plan for health personnel that was established in 1996 [

31]. The country has a strong tradition of community-based healthcare, with health posts and community health workers playing vital roles. However, disparities in workforce distribution and insufficient financial incentives remain significant barriers to achieving equitable health service delivery. Recent investments in digital health have improved workforce efficiency and data management, though these initiatives are still in the early stages.

2.2. Study Respondents

The health workforce data was collected from health facility and community health workers present in the health facility at the time of the survey. The study included healthcare workers who had worked in primary health facilities (health centers, dispensaries, health posts and Nursing homes) for more than one year. Facility in-charge and 2 health care workers per facility ie Nurses/midwives, Clinical Officer, Medical Officer and admins were interviewed. At community level, Community Health Volunteers working within the catchment area of the facility targeted were interviewed.

2.3. Data Collection

The survey data collection tool was organized into five dimensions: employee-employer relationships, remuneration and recognition, professional development, physical environment, and supportive supervision, to effectively assess job satisfaction and health workers. The responses were measured on a 5-point Likert scale of 0: Not applicable, 1: Very dissatisfied, 2: Dissatisfied, 3: Neutral, 4: Satisfied and 5: Very satisfied. Each country engaged trained research assistants in data collection, after piloting of tools. Data collection continued simultaneously in all the countries using KoboCollect tool and stored in secure Kobo servers. The data was then downloaded into Excel workbooks for cleaning and later uploaded into R version 4.2.3 (c) 2023, The R foundation for Statistical Computing, for analysis.

2.4. Sample Size Determination

Each of the countries used a two-stage cluster sampling formula to compute the number of health facilities and health workers per facility to be interviewed. Below is the formula, where:

n= is the required sample size

Z= z- score corresponding to 95% confidence interval, which is 1.96

MOE= desired margin of error, which is 0.05

DEFF= Design effect accounting for clustering at both levels. Therefore,

DEFF=1+(M1-1)*ICC1+(M2ij-1)*ICC2ij where:

M1= Average size of primary clusters (e.g # of Health workers in a subcounty per 10,000 population)

M2ij= Average size of HFs within each Sub county (e.g # of HWs in a HF)

ICC1= Estimated intra-cluster correlation coefficient at the primary cluster level

ICC2ij= Estimated intra-cluster correlation coefficient at the secondary cluster level within each primary cluster

Each country adjusted the calculated sample sizes by 10% to cater for non-responses. The table 1 below presents the numbers of health facilities and the number of health workers in a country that were interviewed.

2.5. Data Analysis

For analysis, quantitative data underwent univariate (descriptive) and bivariate (cross-tabulation) analysis, with results presented in tables disaggregated by country, gender, and age categories. The data was grouped into five themes that spoke about different elements that make up job satisfaction. These themes were analyzed separately but their results collectively formed the overall job satisfaction. These were;

1. Employer-Employee Relationship

This component of job satisfaction was assessed by looking at factors such as the support received from the management, the evaluation of work based on a fair system of performance standards, and the extent to which the institutional rules in place made it easy to work.

2. Remuneration

When evaluating remuneration as an aspect of job satisfaction, different components were considered. These included; the pay being commensurate for the amount of work done, the pay being commensurate for one’s skills, the bonuses and allowances received, and whether the worker’s efforts were being recognized.

3. Professional Development

Job satisfaction as it regards to the professional development of health workers was examined by looking at the Training Opportunities for Professional Development that were available to the health workers, their satisfaction on the Space and Opportunities to Learn New Skills, and the Quality of Blended Training Received.

4. Physical Environment

This was composed of factors like the Protection against Occupational Hazards, the Sufficiency of Work Equipment, the Safety of the Physical Environment, and satisfaction regarding the Housing facilities/housing allowance Provided.

5. Supportive Supervision

Supportive supervision was analyzed by looking at the Coaching Received from the Direct Supervisor, the Extent to which suggestions are heard by the supervisor, and the Availability of supervisor to answer work-related questions.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Professional Characteristics

A total of 1,711 health workers participated in the study, with representation from Tanzania (36%), Uganda (18%), Senegal (11%), Ethiopia (10%), Kenya (8%), Malawi (7%), Zambia (5%) and South Sudan (4%). The median length of service among respondents was 8 years, with Zambia reporting the longest median at 11 years and Ethiopia the shortest at 7 years. Overall, the median facility service length was 4 years, with Zambia and Senegal having the highest at 6 years and Ethiopia and Malawi the lowest at 3 years. Gender distribution revealed, women made up the majority of health workers in most countries apart from Malawi and South Sudan. Overall, 59% of respondents were female, with Zambia exhibiting the highest proportion (72%), followed by Tanzania (64%), Senegal (60%), Kenya (59%), Uganda (58%), Ethiopia (55%), South Sudan (45%) and Malawi (43%). The median age of respondents was 36 years, with Zambia reporting the highest median at 42 years and Ethiopia the lowest at 30 years. Community-based health workers made up 40% of the workforce, with the highest representation in Senegal (77%) and the lowest in Ethiopia (8.2%), while facility-based health workers accounted for the remaining 60%. See

Table 2 for details.

3.2. Job Satisfaction

Satisfaction with the employer-employee relationship was highest in Zambia (80%) and lowest in Tanzania (16%). Remuneration satisfaction was notably higher in Senegal (63%) and followed by Zambia (49%) but extremely low in Malawi (9.8%) and Ethiopia (2.3%). Overall, 44% of the respondents reported being satisfied with their professional development, with Uganda leading (62%) and Ethiopia reporting the lowest satisfaction (29%). Satisfaction with the physical environment stood at 27% overall, with Uganda reporting highest (40%) and Kenya the lowest (12%). Satisfaction with supervisory support was at 62%, with Zambia showing the highest satisfaction levels (73%) and Ethiopia the lowest (30%). See

Table 3 below.

3.3. Predictors of Employer-Employee Relationship Satisfaction

The multivariable analysis of employer-employee relationship satisfaction revealed significant variations based on country, demographics, and job-related factors (

Table 4). Health workers in Zambia showed the highest odds of satisfaction with their employer (OR = 4.97, 95% CI: 2.48–10.30, p < 0.001), followed by Uganda (OR = 2.17, 95% CI: 1.35–3.49, p = 0.001). Conversely, Tanzania struggles the most (OR = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.11–0.27, p < 0.001), indicating widespread dissatisfaction. Satisfaction was also associated with longer service duration. Health workers satisfied with their employer had a mean service duration of 11.1 years, compared to 9.7 years for those dissatisfied (OR = 1.03, 95% CI: 1.01–1.06, p = 0.014). Professional cadre influenced satisfaction, with facility-based workers being more likely to report satisfaction than community-based workers (OR = 3.49, 95% CI: 2.51–4.89, p < 0.001). Job attributes such as pay, professional growth opportunities, the physical environment, and supervisory support were strongly correlated with employer satisfaction. Workers satisfied with their pay were 74% more likely to be satisfied with their employer (OR = 1.74, 95% CI: 1.25–2.41, p = 0.001). Positive perceptions of professional development (OR = 2.24, 95% CI: 1.73–2.92, p < 0.001) and the workplace environment (OR = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.47–2.66, p < 0.001) significantly increased satisfaction. The strongest association was with supervisory support, where workers who felt supported were over three times more likely to be satisfied with their employer (OR = 3.34, 95% CI: 2.51–4.45, p < 0.001).

3.4. Predictors of Remuneration Satisfaction

Table 5 present the predictors of remuneration satisfaction across the eight countries. Health workers in Senegal were the most satisfied with their pay (OR = 26.34, 95% CI: 10.04–90.98, p < 0.001), followed by those in Zambia (OR = 19.47, 95% CI: 6.98–69.82, p < 0.001). In contrast, only 2.3% of Ethiopian health workers reported satisfaction with their remuneration. Significant satisfaction levels were also observed in Kenya (OR = 8.49, 95% CI: 3.10–30.02, p < 0.001), Uganda (OR = 8.86, 95% CI: 3.46–30.13, p < 0.001), and Tanzania (OR = 4.98, 95% CI: 1.94–16.98, p = 0.003). While univariable analysis suggested an association between length of service and remuneration satisfaction (OR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.03–1.07, p < 0.001), this was not significant in the multivariable model (OR = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.99–1.05, p = 0.281). Facility-based health workers were significantly less likely to be satisfied with their pay than community-based workers (OR = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.15–0.28, p < 0.001). Job attributes also played a critical role in remuneration satisfaction. Positive employer-employee relationships (OR = 1.64, 95% CI: 1.17–2.31, p = 0.004), professional development opportunities (OR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.18–2.15, p = 0.002), and a favourable physical environment (OR = 1.57, 95% CI: 1.16–2.12, p = 0.003) were all associated with higher remuneration satisfaction. However, supervisory support was not a significant predictor in the multivariable analysis (OR = 1.11, 95% CI: 0.80–1.56, p = 0.525).

3.5. Predictors of Health Worker Satisfaction with Professional Development

Table 6 outline the predictors of health worker satisfaction with professional development. Health workers satisfied with employer-employee relationships were significantly more likely to be satisfied with their professional development (OR = 2.20, 95% CI: 1.69–2.85, p < 0.001). Satisfaction with remuneration (OR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.19–2.13, p = 0.002), the physical environment (OR = 1.71, 95% CI: 1.32–2.22, p < 0.001), and supervisory support (OR = 3.58, 95% CI: 2.78–4.62, p < 0.001) were also strong predictors. While satisfaction varied by country, it was not a significant predictor after adjusting for other factors. Although health workers in Uganda and South Sudan reported higher satisfaction, these findings were not statistically significant in the multivariable analysis. Demographic factors such as sex, age, and professional cadre had no significant impact, nor did facility tenure or total years of service.

3.6. Predictors of Physical Environment Satisfaction

The predictors of physical environment satisfaction are presented in

Table 7. Satisfaction with the physical environment was significantly influenced by employer-employee relationships (OR = 1.96, 95% CI: 1.46–2.64, p < 0.001), remuneration satisfaction (OR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.18–2.14, p = 0.002), professional development satisfaction (OR = 1.68, 95% CI: 1.29–2.19, p < 0.001), and supervisory support (OR = 2.14, 95% CI: 1.59–2.91, p < 0.001). Health care workers in Kenya (OR = 0.26, 95% CI: 0.13–0.53, p < 0.001) and Zambia (OR = 0.49, 95% CI: 0.24–0.99, p = 0.046) were significantly less likely to report satisfaction with their physical environment compared to Ethiopian workers.

Interestingly, while the length of service did not emerge as a significant predictor, facility-based workers were significantly less likely to report satisfaction with the physical environment compared to community-based workers (OR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.23–0.41, p < 0.001).

3.7. Predictors of Supportive Supervision Satisfaction

The predictors of satisfaction with supportive supervision are summarized in

Table 8. Satisfaction was most strongly associated with remuneration (OR = 2.39, 95% CI: 1.77–3.22, p < 0.001) and employer-employee relationships (OR = 2.51, 95% CI: 1.90–3.30, p < 0.001). Similarly, satisfaction with professional development (OR = 1.95, 95% CI: 1.41–2.68, p < 0.001) and the physical environment (OR = 2.10, 95% CI: 1.59–2.76, p < 0.001) were significant predictors of supportive supervision satisfaction. Tanzania (OR=6.53, 95% CI: 4.19-10.33, p<0.001) and Kenya (OR= 5.02, 95% CI: 2.88-8.89, p<0.001) showed the highest and significant levels of satisfaction with supervision, while health workers in Malawi (OR =1.86, 95% CI: 1.05–3.29, p=0.032) were significantly less likely to report satisfaction.

4. Discussion

This study offers insights into the demographic and professional characteristics of health workers across eight African countries, highlighting variations in workforce composition, tenure, and gender distribution. Tanzania had the largest representation (36%), followed by Uganda (18%) and Senegal (11%), while Zambia (5%) and South Sudan (4%) had the smallest, reflecting differences in workforce distribution and study participation.

The median length of service was 8 years, with Zambia reporting the longest at 11 years and Ethiopia the shortest at 7 years. Zambia and Senegal had the longest median facility service duration (6 years), suggesting a relatively stable workforce, whereas Ethiopia and Malawi had the shortest (3 years), potentially indicating higher turnover or workforce mobility. The high turnover in some Countries could point to job dissatisfaction, poor working conditions, or lack of career growth opportunities. Countries such as Zambia and Uganda which showed longer service duration may be because of better retention policies but could also indicate fewer opportunities for mobility or promotion. While the findings suggest that health workers have multiple years of service, sub-Saharan Africa is faced with challenges such as corruption, poor working conditions and sub-optimal use of time which end up affecting the overall healthcare delivery [

32].

Women comprised the majority of health workers in all countries except Malawi and South Sudan. Overall, 59% of respondents were female, with the highest proportion in Zambia (72%) whereas Malawi (43%) and South Sudan (45%) have a more balanced or male-dominated workforce. Such variations may have implications for gender-sensitive health services, particularly in maternal and child health programs, where female health workers often play a crucial role. The predominance of female health workers aligns with global trends, particularly in nursing and community health roles where women make up 70% of the workforce [

33].

The median age of health workers was 36 years, with Zambia having the oldest median at 42 years and Ethiopia the youngest at 30 years. The relatively older workforce in Zambia suggests a more experienced health sector, whereas Ethiopia’s younger workforce could indicate recent recruitment efforts or higher attrition of older health professionals. However, Africa’s general population is notably young, with a median age of about 20 years. This youthful demographic suggests that the health workforce may also be relatively young, which calls for in-service trainings, mentorship, and career progression opportunities to improve care [

34].

Furthermore, the findings highlight disparities between facility-based and community-based workforce distribution. Senegal and Zambia have a higher proportion of community-based health workers (CBHWs), reinforcing their commitment to primary healthcare and outreach services. Conversely, Ethiopia’s workforce is predominantly facility-based (92%), suggesting a potential gap in community-level service delivery. Expanding community-based programs in such contexts may enhance healthcare access, especially in rural and underserved areas.

4.1. Health Worker Satisfaction with Employer-Employee Relationship

Health workers in Zambia exhibited the highest levels of satisfaction with employer (80%), followed by Uganda at 66%, suggesting stronger organizational support, better working conditions, or more effective management structures. These findings were not very different from a similar study conducted in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa in which the overall levels of job satisfaction were 82.6%, 71% and 52.1% respectively. In contrast, Tanzania reported significantly lower satisfaction at 16%, indicating potential challenges in employer engagement, communication, or workplace policies [

35]. Longer service duration and being a facility-based health work were associated with higher satisfaction with employer. Similarly, job attributes such as pay, professional growth opportunities, the physical environment and supervisory support were strongly correlated with employer satisfaction. These findings are similar to that of a similar study conducted in Ethiopia which reported salary and incentives, benefit packages, recognition by management, patient appreciation, working environment, developmental opportunities, better management, clear communication, and staff working relationship as strong predictors of job satisfaction [

36].

4.2. Health Worker Satisfaction with Remuneration

Senegal (63%) and Zambia (49%) reported the highest levels of satisfaction with pay, possibly due to better compensation structures or incentives. Conversely, Ethiopia had alarmingly low remuneration satisfaction at 2.3%, signalling the need for salary reviews and better financial incentives to retain health workers. Health worker satisfaction with remuneration in Africa varies across regions and is influenced by multiple factors. These findings align with the findings of a study conducted in Ethiopia which documented that despite governmental efforts to enhance health infrastructure and workforce numbers, national health services often struggle to attract and retain health workers. This challenge is partly due to inadequate remuneration and insufficient attention to incentives and motivation, leading to decreased productivity and increased turnover among health professionals [

36]. Facility-based health workers were significantly less satisfied with their remuneration compared to community-based workers. This could be due to differences in workload, compensation models, or perceived fairness in pay structures such as working conditions, resource availability, and management practices. The findings are similar to studies conducted in Eastern Ethiopia and South Africa [

37].

4.3. Health Workers’ Satisfaction with Professional Development

Overall, 44% of health workers were satisfied with professional growth opportunities. Uganda led (62%), potentially reflecting stronger training programs and career advancement pathways. Ethiopia (29%) had the lowest satisfaction, suggesting limited access to capacity-building opportunities and career progression. Organizations that prioritize career development contribute positively to health workers’ satisfaction, as documented by Essex County Council in the UK where emphases on career progression of its social workers led to improved moral and retention [

38]. The strongest predictors of health worker’s satisfaction with professional development were supervisory support, employer-employee relations, satisfaction with remuneration and the physical work environment. These findings align with existing literature that emphasizes the importance of supportive work environments, fair compensation, and effective supervision in enhancing job satisfaction among healthcare professionals [

39].

4.4. Health Worker Satisfaction with Physical Environment

Employer-employee relationships, remuneration satisfaction, professional development satisfaction, and supervisory support play significant roles in shaping perceptions of the physical workspace. Existing literature suggests that positive employer-employee relationships foster a sense of workplace belonging and trust, which directly influences satisfaction with the physical work environment [

40].

4.5. Satisfaction with Supportive Supervision

The findings indicate that satisfaction with supportive supervision is significantly influenced by remuneration, employer-employee relationships, professional development opportunities, and the physical work environment. These results align with previous studies emphasizing the role of financial incentives and workplace relationships in enhancing supervisory satisfaction [

39]. Similarly, strong employer-employee relationships foster trust and communication, leading to a more positive supervisory experience [

41].

5. Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the characteristics, job satisfaction, and workforce dynamics of health workers across eight African countries. The findings reveal significant variations in satisfaction levels based on factors such as country of operation, job attributes, and demographic characteristics. Zambia and Senegal reported higher satisfaction across several domains, especially regarding remuneration, supervisory support, and professional development opportunities. In contrast, Tanzania and Ethiopia showed lower satisfaction, especially concerning employer-employee relationships, remuneration, and the physical working environment.

The results underscore the importance of country-specific workforce strategies in shaping health worker satisfaction, retention, gender equity and workforce distribution. Key determinants of satisfaction included the employer-employee relationship, remuneration, and physical environment. Additionally, community-based workers, particularly in Senegal, expressed varying levels of satisfaction compared to facility-based workers, highlighting the impact of employment the nature on job satisfaction.

Countries like Zambia and Uganda report longer service durations, suggesting greater workforce retention, while Ethiopia and Malawi have shorter service lengths, potentially indicating higher turnover. The gender distribution varies across Countries, with Zambia having higher proportion of female workers, whereas Malawi and South Sudan have a more balanced or male -dominated workforce. Additionally, the distribution of community-based verses facility-based workers differs significantly, with Countries like Senegal and Zambia emphasizing community-based health services while Ethiopia relies more on facility-based care.

To enhance workforce satisfaction and retention, the study calls for targeted interventions focusing on job-related factors such as improved remuneration, supportive supervision, professional development, and better working conditions. The disparities across countries suggest that tailored strategies, accounting for local contexts and challenges, will be essential for addressing these issues effectively.

Addressing these factors will be crucial for strengthening the health workforce, improving health outcomes, and achieving sustainable healthcare progress. This study serves as a valuable resource for policymakers and organizations aiming to improve health worker satisfaction and retention in the African context.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M, Y.O and M.J; Data curation, S.M, L.O, B.A, M.J and R.K; Formal analysis, L.O, B.A and R.K; Investigation, S.M and M.J; Methodology, S.M, Y.O and M.J; Software, S.M, Y.O and M.J; Validation, S.M, L.O, M.J, B.A and R.K; Writing – original draft, S.M, Y.O, S.K, L.O, R.M, B.A, M.J, I.G and R.K; Writing – review & editing, S.M, Y.O, S.K, L.O, R.M, B.A, M.J, L.N, I.G and R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding and no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The research was funded by Amref Health Africa.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The countries were governed by approved research protocols that were either approved by local ethics committees or were exempted. Five countries received ethical approval: Ethiopia, Kenya approved by the Amref Ethics and Scientific Review Committee (ESRC), ESRC P1580/2023 on 21 November 2023. Tanzania approved by the National Institute for Medical research, NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol.IX/4440 on 27th October 2023 and by the Zanzibar Health Research Institute, ZAHREC/04/PR/NOV/2023/35 on 17 November 2023. Zambia approved by Eres Converge, an independent ethics board, 2023 -Nov-001 on 28 November 2023 and the National Health Research Authority (NHRA) on 27 November 2023). Uganda approved by Uganda Christian University Review and Ethics Committee, UCUREC-2023-699 on 7 November 2023. South Sudan, Malawi and West Africa were exempted.

Informed Consent Statement

The researchers obtained informed consent from all participants before they participated. The participants were informed that they were free to end their involvement in the interview any time. They were also assured that withdrawal from the study would not affect in any way the intended support from Amref Health Africa. To protect confidentiality, records contained no names or other personal identifiers. Interviews were also conducted in privacy to ensure there were no other people around to listen to the interviews. Care was also taken not to raise expectations that the participants or their family or community would receive material benefits such as money because of their participation. Consent for publication is not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the Amref Health Africa leadership and management for the crucial role they played in the successful undertaking of this survey. Without your approval and financing, this undertaking would not have been possible. We also acknowledge the special role that was played by the country teams and focal persons in ensuring the smooth running of the survey and the end-to-end delivery of a successful study. We deeply appreciate the effort you put into ensuring that the survey was conducted successfully. Our deepest gratitude goes to all the participants from the different countries who sacrificed their time to take part in the survey and to give valuable feedback and responses to the questions we raised. We also appreciate the research assistants who diligently took the participants through the survey with great patience and skill to enable us have quality data that has helped in writing of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper. All authors have contributed significantly to the creation of this manuscript and have read and approved the final version submitted. There are no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence our findings.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LMICs |

Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| PHC |

Primary Health Care |

| UHC |

Universal Health Coverage |

| HEWs |

Health Extension Workers |

| CHVs |

Community Health Volunteers |

| CHWs |

Community Health Workers |

| DfID |

Department for International Development |

| NORAD |

Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation |

| DHS |

Demographic and Health Survey |

| DHIS |

District Health Information System |

References

- J. M. Ivancevich, R. Konopaske, and M. T. Matteson, Organizational, Behavior & Management, Tenth Edition. 2014.

- M. A. I. Gazi, M. F. Yusof, M. A. Islam, M. Bin Amin, and A. R. bin S. Senathirajah, “Analyzing the impact of employee job satisfaction on their job behavior in the industrial setting: An analysis from the perspective of job performance,” Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, vol. 10, no. 4, p. 100427, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lu et al., “Job satisfaction and associated factors among healthcare staff: a cross-sectional study in Guangdong Province, China,” BMJ Open, vol. 6, no. 7, p. e011388, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. G. Toh, E. Ang, and M. Kamala Devi, “Systematic review on the relationship between the nursing shortage and job satisfaction, stress and burnout levels among nurses in oncology/haematology settings,” Int J Evid Based Healthc, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 126–141, Jun. 2012. [CrossRef]

- “Primary health care.” Accessed: Mar. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/primary-health-care.

- S. P. P. Choi, K. Cheung, and S. M. C. Pang, “Attributes of nursing work environment as predictors of registered nurses’ job satisfaction and intention to leave,” J Nurs Manag, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 429–439, Apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- “Measurement of job satisfaction among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study.” Accessed: Mar. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/mi.2022.62.

- S. Luboga, A. Hagopian, J. Ndiku, E. Bancroft, and P. McQuide, “Satisfaction, motivation, and intent to stay among Ugandan physicians: a survey from 18 national hospitals,” Int J Health Plann Manage, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 2–17, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- H. Lu, K. L. Barriball, X. Zhang, and A. E. While, “Job satisfaction among hospital nurses revisited: A systematic review,” Int J Nurs Stud, vol. 49, no. 8, pp. 1017–1038, Aug. 2012. [CrossRef]

- L. H. Aiken, S. P. Clarke, D. M. Sloane, J. Sochalski, and J. H. Silber, “Hospital Nurse Staffing and Patient Mortality, Nurse Burnout, and Job Dissatisfaction,” JAMA, vol. 288, no. 16, pp. 1987–1993, Oct. 2002. [CrossRef]

- “State of the Global Workplace Report - Gallup.” Accessed: Mar. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://www.gallup.com/workplace/349484/state-of-the-global-workplace.aspx.

- P. A. Afulani et al., “Job satisfaction among healthcare workers in Ghana and Kenya during the COVID-19 pandemic: Role of perceived preparedness, stress, and burnout,” PLOS Global Public Health, vol. 1, no. 10, p. e0000022, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- “Second round of the national pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the,” 2021.

- J. Frenk et al., “Health professionals for a new century: Ttransforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world,” The Lancet, vol. 376, no. 9756, pp. 1923–1958, Dec. 2010.

- F. N. Jaeger, M. Bechir, M. Harouna, D. D. Moto, and J. Utzinger, “Challenges and opportunities for healthcare workers in a rural district of Chad,” BMC Health Serv Res, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 1–11, Jan. 2018.

- E. Moyo, M. Dzobo, P. Moyo, G. Murewanhema, I. Chitungo, and T. Dzinamarira, “Burnout among healthcare workers during public health emergencies in sub-Saharan Africa: Contributing factors, effects, and prevention measures,” Human Factors in Healthcare, vol. 3, p. 100039, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mathauer and I. Imhoff, “Health worker motivation in Africa: The role of non-financial incentives and human resource management tools,” Hum Resour Health, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1–17, Aug. 2006.

- “The Health Workforce in Ethiopia by World Bank Staff (Ebook) - Read free for 30 days.” Accessed: Mar. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://www.everand.com/book/80624101/The-Health-Workforce-in-Ethiopia.

- “Ethiopian Community Health Worker Programs.” Accessed: Mar. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://chwcentral.org/ethiopian-community-health-worker-programs/.

- A.A. Hilo and J. McPeak, “Addressing concerns of access and distribution of health workforce: a discrete choice experiment to develop rural attraction and retention strategies in southwestern Ethiopia,” BMC Health Serv Res, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 1–15, Dec. 2024.

- T. J. Bossert and J. C. Beauvais, “Decentralization of health systems in Ghana, Zambia, Uganda and the Philippines: a comparative analysis of decision space,” Health Policy Plan, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 14–31, Mar. 2002. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Okoroafor et al., “Investing in the health workforce in Kenya: trends in size, composition and distribution from a descriptive health labour market analysis,” BMJ Glob Health, vol. 7, no. Suppl 1, p. e009748, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Facilitator Guide - Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response District Level Training Course | WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/facilitator-guide-integrated-disease-surveillance-and-response-district-level-training (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- M. N. Mukasa et al., “Examining the organizational factors that affect health workers’ attendance: Findings from southwestern Uganda,” Int J Health Plann Manage, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 644–656, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. M. Dambisya and S. Matinhure, “Policy and programmatic implications of task shifting in Uganda: A case study,” BMC Health Serv Res, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Mar. 2012.

- S. C. Okoroafor and C. Dela Christmals, “Task Shifting and Task Sharing Implementation in Africa: A Scoping Review on Rationale and Scope,” Healthcare 2023, Vol. 11, Page 1200, vol. 11, no. 8, p. 1200, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Njunwa, “Employee’s Motivation in Rural Local Governments in Tanzania: Empirical Evidence from Morogoro District Council,” Journal of Public Administration and Governance, vol. 7, no. 4. [CrossRef]

- Malawi - Harmonized Health Facility Assessment : 2018-2019 Report (Vol. 1 of 4) : Main Report. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/417871611550272923/417871611550272923 (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Article: The Emigration of Health-Care Workers: Ma.. | migrationpolicy.org. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/emigration-health-care-workers-malawi%E2%80%99s-recurring-challenges (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Deteriorating Humanitarian Situation in South Sudan, Rising Attacks on Aid Workers ‘Worrying’ Special Representative Tells Security Council | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases. Available online: https://press.un.org/en/2021/sc14636.doc.htm (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- How did Senegal implement? | Exemplars in Global Health. Available online: https://www.exemplars.health/topics/stunting/senegal/how-did-senegal-implement (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- S. C. E. Anyangwe and C. Mtonga, “Inequities in the Global Health Workforce: The Greatest Impediment to Health in Sub-Saharan Africa,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2007, Vol. 4, Pages 93-100, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 93–100, Jun. 2007. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, “Delivered by women, led by men: a gender and equity analysis of the global health and social workforce,” Human Resources for Health Observer Series, no. 24, pp. 1–60, 2019. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/health-workforce/delivered-by-women-led-by-men.pdf?sfvrsn=94be9959_2 (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- B. Daniels, A. Yi Chang, R. Gatti, and J. Das, “The medical competence of health care providers in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from 16 127 providers across 11 countries,” Health Affairs Scholar, vol. 2, no. 6, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Blaauw et al., “Comparing the job satisfaction and intention to leave of different categories of health workers in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa,” Glob Health Action, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 19287, 2013. [CrossRef]

- B. K. Deriba, S. O. Sinke, B. M. Ereso, and A. S. Badacho, “Health professionals’ job satisfaction and associated factors at public health centers in West Ethiopia,” Hum Resour Health, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1–7, May 2017.

- H. Merga and T. Fufa, “Impacts of working environment and benefits packages on the health professionals’ job satisfaction in selected public health facilities in eastern Ethiopia: Using principal component analysis,” BMC Health Serv Res, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1–8, Jul. 2019.

- There’s a commitment to progression that’s led from the top’: how Essex made career development a priority for its social workers | Social Care Careers In Essex | The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/social-care-careers-in-essex/2025/feb/06/theres-a-commitment-to-progression-thats-led-from-the-top-how-essex-made-career-development-a-priority-for-its-social-workers (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- M. Willis-Shattuck, P. Bidwell, S. Thomas, L. Wyness, D. Blaauw, and P. Ditlopo, “Motivation and retention of health workers in developing countries: A systematic review,” BMC Health Serv Res, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–8, Dec. 2008.

- M. Dieleman, B. Gerretsen, and G. J. van der Wilt, “Human resource management interventions to improve health workers’ performance in low and middle income countries: A realist review,” Health Res Policy Syst, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–13, Apr. 2009.

- Mathauer and I. Imhoff, “Health worker motivation in Africa: The role of non-financial incentives and human resource management tools,” Hum Resour Health, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1–17, Aug. 2006.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).