1. Introduction

The zebrafish (

Danio rerio) has become a cornerstone of vertebrate biomedical research, renowned for its suitability in developmental biology, genetics, and disease modeling. Key attributes such as external fertilization, optical transparency during early development, small size, and rapid embryogenesis enable real-time imaging and precise experimental manipulation [

1,

2]. Additionally, the high degree of genetic conservation with humans—approximately 70% genome orthology—underscores its value for translational studies [

3]. The ease of embryo collection and cost-effective husbandry further support its widespread use. The introduction of genome editing technologies, particularly CRISPR/Cas9, has significantly expanded the zebrafish’s role in functional genomics, enabling precise gene disruption and disease model generation [

4].

In parallel with in vivo applications, the establishment of zebrafish cell lines from embryonic and adult tissues has created complementary in vitro systems that support mechanistic studies under defined conditions. Early-stage embryo-derived lines such as ZF4, ZFL, and ZEM2 maintain stable proliferation and exhibit pluripotent or multipotent features across passages [

5,

6,

7]. These cultures provide platforms for toxicological testing, drug screening, and molecular analysis, while also aligning with the ethical principles of the 3Rs—Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement—by reducing reliance on live animal experimentation [

8,

9]. Their long-term stability and scalability make them increasingly indispensable in vertebrate cellular and molecular biology.

Technological advances have continued to refine these systems. The adoption of feeder-free and chemically defined media has improved reproducibility across laboratories [

10,

11], while transfection methods such as nucleofection have enhanced gene delivery efficiency in zebrafish cells, enabling both transient and stable expression [

12]. Optimized CRISPR/Cas9 systems using zebrafish-specific promoters have made in vitro gene editing feasible and reproducible [

4]. A recent milestone in the field is the protocol by Geyer

et al. (2023), which enables the derivation of cell lines from individual 24–36 hpf embryos, coupled with parallel genotyping to generate wild-type and homozygous mutant cultures [

13]. This overcomes previous limitations in isolating viable mutant lines from early-lethal or morphologically indistinct phenotypes, and facilitates the controlled production of genotype-defined cell lines.

Zebrafish-derived cell cultures have also emerged as powerful tools in oncology. Xenotransplantation of human and murine tumor cells into embryos or clonal zebrafish lines permits the study of tumor growth, metastasis, and host interaction in vivo without the need for immunosuppression [

14]. When integrated with 3D culture systems, organoid technology, and transcriptomics, these models enable high-throughput drug screening and mechanistic studies with high resolution and cost-efficiency [

15]. Altogether, the integration of zebrafish embryo cell lines with genome editing and advanced in vitro techniques reinforces their utility as versatile platforms for both basic and translational biomedical research.

To construct this review, we conducted a focused literature search using PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus, emphasizing studies on the generation and biomedical application of zebrafish embryo-derived cell lines. Search terms included “zebrafish embryo cell line,” “zebrafish culture,” “pluripotency zebrafish cell lines,” “zebrafish cell lines transfection,” and “zebrafish organoids”. We prioritized peer-reviewed reports describing original derivation protocols, functional characterization, and innovations relevant to disease modeling, genome editing, and regenerative medicine. Foundational articles were also included to trace the methodological evolution of the field. Key information such as derivation stage, media composition, transfection methods, and lineage potential, was extracted and summarized in comparative tables.

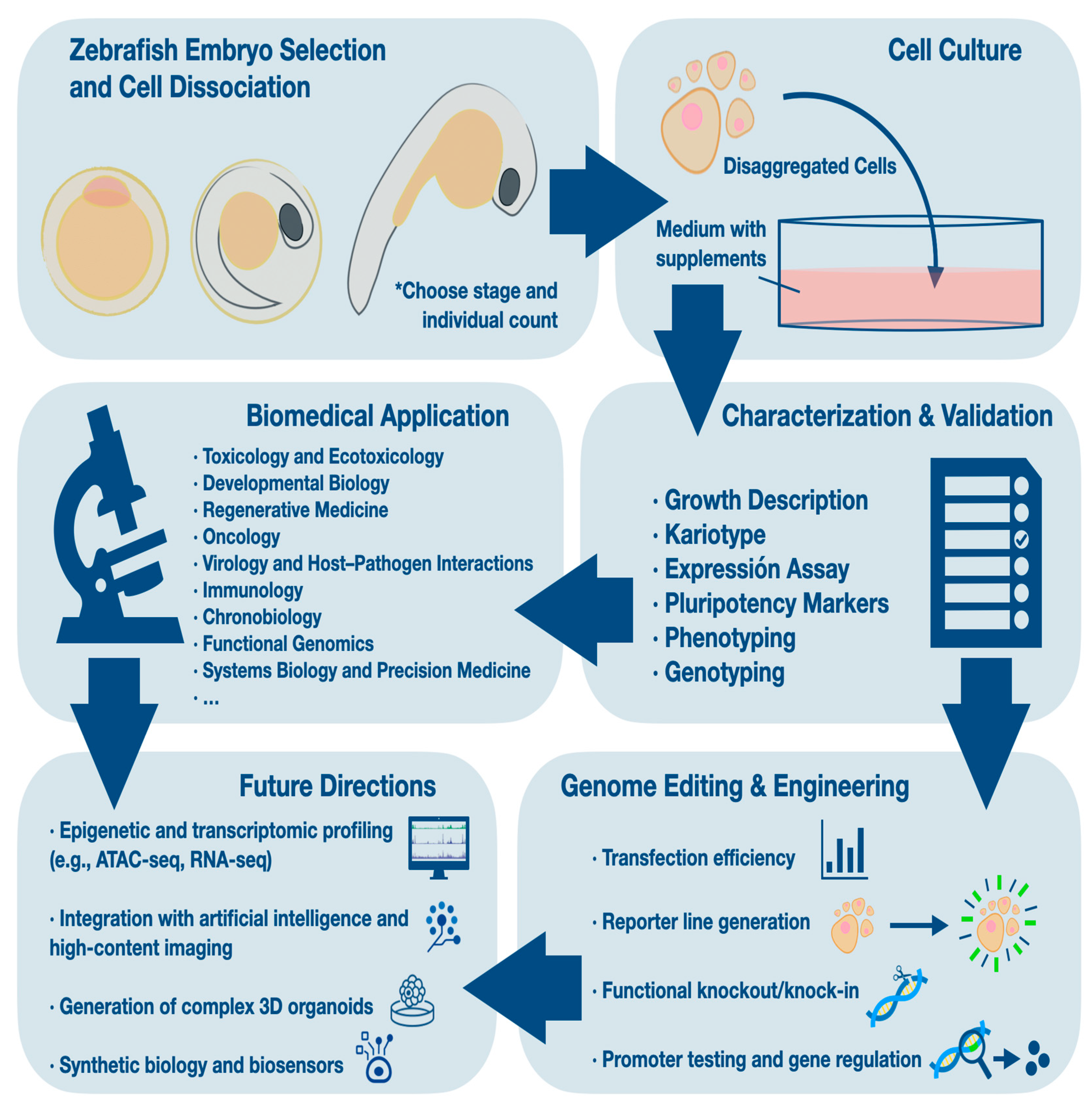

A general overview of the workflow for generating and applying zebrafish embryo-derived cell lines is depicted in

Figure 1.

2. Overview of Zebrafish Embryo Cell Culture

Zebrafish cell lines are commonly derived from early developmental stages such as the blastula, gastrula, or pre-hatching embryo, when cells exhibit high proliferative capacity and, under appropriate conditions, can retain pluripotent or multipotent features [

9]. Early protocols relied on complex media formulations supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS), trout serum, or trout embryo extract to support survival and proliferation [

1,

2,

16]. Over time, these media were refined using more defined formulations—such as DMEM, DMEM/F12, and RPMI—often enriched with insulin, selenium, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and Kit ligand to maintain undifferentiated states and promote sustained growth [

8,

10].

Among available media, Leibovitz’s L-15 has become one of the most widely used for zebrafish and other teleost cell lines. Its buffering capacity without the need for CO₂ makes it ideal for laboratories without CO₂ incubators, while its compatibility with culture temperatures of 26–28°C suits zebrafish biology. Numerous lines, including DRCF, ZFL, PAC2, ZEF1/ZEF2, and PAC2-luc, are maintained in L-15 supplemented with 10–20% FBS, and in the case of ZFL, also with HEPES to stabilize pH [

12,

15,

17,

18].

In parallel, alternative media formulations have been developed to accommodate the specific requirements of distinct cell lines. For example, pluripotent-like lines such as ZES1 and Z428 are maintained in feeder-free DMEM-based media supplemented with bFGF, which support both self-renewal and directed differentiation while eliminating the need for feeder layers [

10,

11]. Feeder-free systems—defined as culture methods that do not rely on a layer of supportive "feeder" cells—have become essential for improving reproducibility and reducing variability caused by undefined factors secreted by feeder layers. The transition to these systems was also applied to the ZEB2J line, initially established on RTS34st feeder cells and later adapted to feeder-free, serum-based conditions (Xing et al., 2008). Similarly, Liu et al. (2010) describe the generation of ZSSJ cells, also derived via initial co-culture with RTS34st cells. These lines express canonical stem cell markers—including nanog, sox2, and pou5f1—and have demonstrated the ability to form embryoid bodies and contribute to all germ layers in vivo. Other lines such as ZBE3 and PTEN-mutant tumor lines from ptenb−/− or ptena+/− ptenb−/− fish are cultured in standard DMEM with 10% FBS for use in cancer modeling and immune interaction assays [

19,

20]. ZF4 and ZEB2J are commonly maintained in DMEM/F12. Altogether, the shift toward defined, feeder-free culture conditions enhances reproducibility and facilitates downstream applications such as transfection, gene editing, and directed differentiation.

Beyond media composition, physical and environmental parameters play a crucial role in culture success. Most zebrafish lines are propagated at 26–28°C under ambient CO₂. Surface coatings with gelatin or extracellular matrix proteins enhance cell adhesion, and in earlier protocols, feeder layers—particularly RTS34st—were essential for maintaining stem-like phenotypes [

22,

23]. Some of these feeder cells were genetically engineered to express supportive factors like kit ligand a (

kitlga) and stromal cell-derived factor 1b (s

df-1b), boosting long-term proliferation of primordial germ cells (PGCs) from

vasa::RFP transgenic embryos [

8]. Modern culture strategies now support both self-renewal and directed differentiation into lineages such as neural or muscular cells via specific growth factor combinations [

9].

A detailed summary of the most widely used zebrafish cell lines—including their origin, media, key characteristics, and applications—is presented in

Table 1.

3. Protocols for Establishing Cell Lines

The establishment of zebrafish cell lines typically begins with the enzymatic dissociation of early-stage embryos—most commonly at the blastula or gastrula stages—when cells are undifferentiated and highly proliferative. Treatments with pronase, trypsin, or collagenase enable removal of the chorion and extracellular matrix, yielding single-cell suspensions suitable for seeding onto surfaces pre-coated with gelatin, poly-L-lysine, or extracellular matrix proteins to enhance cell adhesion [

2,

27]. Early protocols often relied on feeder layers, such as RTS34st cells from rainbow trout spleen, to support cell survival and outgrowth, a strategy used in generating the ZEB2J line [

21]. Although these methods initially required pooling 50–100 embryos, current approaches enable culture initiation from single embryos—a significant advance that facilitates genotype-specific studies and reduces animal use. The individualized strategy described by Geyer

et al. (2023), covered in detail in

Section 7, exemplifies this shift [

13].

Both haploid and diploid embryos have been used successfully. While haploid cultures are transient and generally unsuitable for long-term maintenance, their hemizygous nature makes them valuable for detecting recessive mutations in screening assays [

8,

16]. In contrast, diploid-derived lines exhibit greater genomic and proliferative stability, and are typically used in long-term studies across various biological applications.

Several well-characterized lines illustrate the range of derivation strategies. ZEM-2, derived from pooled blastula embryos, was originally cultured in media containing trout extract and serum. Its derivative, ZEM-2A, adapted to a simplified formulation with 5% FBS, shows increased transfection efficiency using viral promoters such as CMV, SV40, and RSV [

27]. Similarly, the ZF4 line, derived from 24 hpf embryos, supports stable transfection and prolonged growth [

5], while PAC2 cells—also from 24 hpf embryos—have proven useful in circadian biology and CRISPR experiments, particularly in the form of the luciferase-expressing PAC2 reporter line [

18,

24,

26].

Pluripotent-like lines such as ZES1 and Z428 have been derived under feeder-free conditions using DMEM supplemented with bFGF, and are characterized by stable proliferation, embryoid body formation, and expression of stemness markers including

pou5f1 (

oct4),

nanog,

sox2, and

lin28 [

10,

11]. These lines are particularly suitable for developmental and differentiation studies. Others, such as ZBE3, are optimized for transfection efficiency and viral susceptibility [

19], while ZEF1/ZEF2, derived from 5–10 somite embryos, support high-efficiency nucleofection for transgene delivery [

12].

Beyond embryonic sources, alternative protocols have enabled the derivation of lines from adult tissues and tumor models. The DRCF line, obtained from caudal fin tissue, exhibits fibroblastic morphology and is highly amenable to transfection [

17]. Tumor-derived lines, including fibroblast-like PTEN-KO cultures from

ptenb−/−embryos and endothelial-like cells from spontaneous tumors in

ptena+/−;ptenb−/− fish, provide valuable tools for modeling tumorigenesis, migration, and angiogenesis [

20].

These diverse methodologies highlight the versatility of zebrafish cell culture systems, which can be tailored to specific experimental goals.

Table 1 summarizes the main features of established zebrafish lines, including their origin, key markers, karyotype, transfection strategies, and applications. Despite this diversity, a major challenge persists: the lack of standardized benchmarking across cell lines. Comparative data on growth rates, differentiation capacity, or transfection efficiency under equivalent conditions remain scarce. Addressing this gap through systematic studies would enhance reproducibility and help guide the selection of the most appropriate lines for specific assays or screening platforms.

4. Pluripotency in Zebrafish Cell Lines

Pluripotency—the capacity of a cell to give rise to all three germ layers—is a defining feature of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and has been investigated in zebrafish both in vivo and in vitro. Zebrafish ES-like lines such as ZES1 and Z428, derived from blastula-stage embryos under feeder-free conditions, express key transcription factors shared with mammalian ESCs (

Table 2) along with alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity as an enzymatic marker [

10,

11]. These lines can form embryoid bodies and have demonstrated the potential to contribute to all three germ layers in chimera assays, indicating functional pluripotency [

22,

23].

Despite these similarities, interspecies differences in regulatory programs must be considered. Zebrafish embryonic cells express unique early developmental markers such as

tdgf1 and

gdf3, which are not conserved in human ESCs [

28]. Additionally, while zebrafish ES-like cells express the surface antigen SSEA1 prior to the onset of Pou5f1 and Nanog expression [

29], human ESCs are characterized by the expression of markers such as SSEA3, SSEA4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81, and CD24, alongside OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG [

30]. These distinctions underscore the necessity of species-specific criteria when assessing stemness. A comparative summary of molecular and functional pluripotency features in zebrafish and human ESCs is presented in

Table 2.

A comparative perspective across model organisms highlights both the potential and current limitations of zebrafish embryo-derived cell lines. In contrast to murine and human pluripotent stem cells, which are extensively characterized using molecular and functional benchmarks such as OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, zebrafish cell lines still lack standardized criteria for pluripotency. Moreover, while zebrafish blastula-derived cultures can express key genes such as

pou5f1 and

sox2, the expression of pluripotency-associated proteins in vitro remains low or undetectable under standard conditions [

29]. The interpretation of pluripotency in zebrafish must therefore be approached cautiously, and functional assays equivalent to teratoma formation or directed differentiation are still underdeveloped in this species.

In comparison, medaka (

Oryzias latipes) embryonic stem-like cells, such as MES1, retain a diploid karyotype, maintain long-term self-renewal, contribute to chimeras in vivo, and activate regulatory elements from mammalian pluripotency genes [

35]. These lines express conserved pluripotency genes including

nanog,

oct4,

sall4,

klf4,

tcf3, and

ronin, and downregulate them upon differentiation, offering a stronger model for understanding vertebrate pluripotency [

36].

Other teleosts, such as red sea bream (

Chrysophrys major), have yielded embryonic stem-like cell lines (SBES1) with in vitro differentiation capacity into multiple lineages including neuron- and muscle-like cells [

37]. These comparative examples suggest that the zebrafish model may benefit from further methodological development aimed at stabilizing pluripotent states and validating in vitro differentiation potential.

Additionally, transcriptional network conservation across vertebrates has been documented, but fish-specific differences in marker behavior, such as the early expression of SSEA1 prior to

pou5f1 or

sox2 activation in zebrafish colonies, emphasize the need to establish lineage- and species-specific standards [

29,

38].

It is important to differentiate between molecular pluripotency, defined by the expression of canonical transcription factors, and functional pluripotency, evidenced by self-renewal and multilineage differentiation in vitro or in vivo. Although zebrafish ES-like lines robustly express key transcription factors, most resemble a "primed" state similar to the post-implantation epiblast, rather than the "naïve" state of the inner cell mass. Regulatory differences support this interpretation: in zebrafish, Sox2 is predominantly linked to neural specification, unlike its central role in pluripotency maintenance in human ESCs [

29,

33]. Moreover, zebrafish ESCs lack well-characterized epigenetic profiles, such as the differential usage of Oct4 enhancers observed in human systems (Heng & Ng, 2010 [

34].

Nevertheless, zebrafish lines like Z428 have been directed to differentiate into neuronal, hepatic, and cardiac lineages [

7,

31], supporting their relevance for regenerative biology and in vitro modeling of lineage specification. These functional capabilities, however, can be compromised by spontaneous differentiation and epigenetic drift, particularly under long-term culture. As such, continuous molecular profiling—via transcriptomic and epigenetic analyses—is critical to validate and preserve the stem-like state during propagation [

13]. In sum, zebrafish ES-like lines represent a promising, though still developing, platform for studying vertebrate pluripotency and differentiation.

5. Transfection Capabilities and Strategies

The capacity for efficient transfection is a critical parameter when selecting zebrafish cell lines for gene editing, functional assays, or long-term lineage tracing. Early studies demonstrated that lines such as ZEM-2A and ZF4 are amenable to transgene delivery using mammalian promoters—such as CMV, SV40, and RSV—supporting transient expression and, in some cases, stable integration via neomycin resistance [

5,

27]. PAC2 cells, especially the luciferase-reporter variant, have been widely used in circadian biology, maintaining stable luminescent output for over 20 days, while ZBE3 supports GFP expression and viral infection, making it suitable for host–pathogen interaction studies [

18,

19].

A broad range of delivery strategies has been applied to zebrafish lines. Chemical transfection agents such as FuGENE HD and Nanofectin have shown moderate success, but certain lines, like ZF4, require physical methods for efficient gene delivery. Nucleofection—an electroporation-based technique—has proven particularly effective in fibroblast-like lines resistant to chemical reagents [

12,

39]. For example, in ZF4 cells, nucleofection of a pmaxGFP plasmid reached 72% efficiency, compared to only 32% with lipofection using X-tremeGENE HP [

39]. Similarly, PAC2 cells showed 40–50% efficiency when nucleofected with GFP plasmids, compared to only 5% using FuGENE 6 [

25].

Importantly, delivery systems must be considered in conjunction with the molecular cargos introduced. In addition to fluorescent reporters, functional constructs such as those based on the Tol2 transposon system and CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing platforms have been tested. Tol2, originally from

Oryzias latipes, is not a transfection method but a cargo that can be introduced via standard lipofection or electroporation and requires co-delivery with Tol2 transposase mRNA to achieve stable integration. Although commonly used in embryos, successful use in cell lines has been less frequently reported and remains largely qualitative [

40,

41].

CRISPR/Cas9-based editing has been demonstrated in zebrafish cell lines using plasmid or viral delivery systems. For example, PAC2 cells were successfully edited using a lentiviral vector expressing Cas9 and sgRNA driven by the zebrafish U6 promoter, resulting in functional loss-of-gene expression of

ctgfa, although editing efficiency was not quantified [

4]. In contrast, the DRCF line was transfected with a pEGFP-N1 plasmid using Lipofectamine LTX, confirming transgene expression but without reporting efficiency [

17].

These diverse strategies are summarized in

Table 3, which compiles delivery methods, cargo types (e.g., GFP, Tol2, CRISPR), and reported efficiencies across several zebrafish cell lines. While quantitative benchmarks remain limited and sometimes qualitative, the table serves as a practical guide to help researchers align their goals with the most appropriate cell models and transfection protocols.

In some cases, such as PAC2 cells edited with lentiviral CRISPR/Cas9, editing was validated functionally but no quantitative mutation frequency was reported [

4]. Future work should emphasize the standardization of transfection protocols across laboratories and the systematic reporting of both transient and stable expression metrics. Optimizing promoter compatibility, delivery conditions, and validation methods tailored to zebrafish cells will be critical for improving reproducibility and expanding their utility in biomedical research.

Zebrafish cell models provide flexibility across applications. Feeder-free lines like ZES1, Z428, and ZBE3 are suited to developmental biology and viral infection models [

11,

19], while ZF4, ZEM-2A, and PAC2-luc are optimal for high-throughput reporter assays and pharmacological screens [

18,

27]. However, standardized quantitative benchmarks for transfection efficiency across zebrafish lines remain scarce.

Table 3 offers a consolidated starting point for guiding experimental design and evaluating methodological feasibility.

6. Applications of Zebrafish Cell Lines

Zebrafish cell lines, derived from both embryonic and adult tissues, have become indispensable tools in biomedical and environmental sciences. Their vertebrate origin, high genetic similarity to humans, and responsiveness to genetic and pharmacological manipulation make them highly suitable for diverse in vitro applications. These include toxicology, developmental biology, oncology, immunology, neurobiology, chronobiology, and increasingly, regenerative and translational medicine. Serving as simplified yet biologically relevant systems, these cultures complement in vivo zebrafish models by offering scalable platforms for controlled, high-throughput experimentation.

In toxicological research, several zebrafish lines have demonstrated strong utility in environmental monitoring and xenobiotic metabolism studies. The ZFL line, derived from adult liver tissue, is a benchmark model for hepatic toxicity, particularly through inducible expression of cytochrome P450 enzymes like CYP1A1 in response to TCDD [

6]. ZF4 cells, obtained from 24 hpf embryos, are widely used to assess the toxicity of nanoparticles, pesticides, and endocrine-disrupting compounds [

15,

25]. Meanwhile, the ZEM2S line, adapted to simplified serum-free media, has been applied in ecotoxicological testing, supporting reproducible and ethically sound assays [

25].

In developmental biology, ES-like lines such as ZES1 and Z428 offer robust platforms for studying early lineage specification and stemness. These lines express canonical pluripotency markers, form embryoid bodies in vitro, and contribute to germ layers in chimeric assays [

11,

22,

23]. They can be directed toward specific lineages—including neuronal, hepatic, and cardiac fates—under defined protocols, thus providing valuable models for vertebrate development and regenerative research [

27,

31]. Their functional analogy to mammalian ESCs makes them key models for exploring evolutionarily conserved pathways.

In the oncology field, zebrafish cell lines have enabled both in vitro and in vivo cancer studies. Tumor-derived lines from

ptena+/−; ptenb−/− backgrounds recapitulate hallmarks of cancer such as angiogenesis, migration, and drug resistance [

20]. These cells support detailed analysis of tumor biology and integrate well with xenotransplantation assays in zebrafish embryos. The development of zebrafish patient-derived xenograft (zPDX) models further enhances their translational value, offering a cost-effective, vertebrate-compatible platform for drug screening and personalized therapy evaluation [

42]. Coupled with transcriptomic and imaging techniques, these models allow real-time monitoring of tumor progression and treatment response.

Zebrafish lines also support virology, immunology, and chronobiology. For instance, ZBE3 is susceptible to viral infection and supports GFP expression, facilitating real-time analysis of viral replication and host–pathogen interactions [

19]. PAC2 and ZEB2J have been used to study innate immune pathways and stress responses, while the PAC2-luc line enables monitoring of circadian gene expression through its stable luciferase reporter system [

18].

Recent advances in molecular tools have broadened the experimental scope of zebrafish cell cultures. ZEF1 and ZEF2 fibroblasts from somite-stage embryos, as well as the DRCF line from adult fin, show high compatibility with nucleofection and transgene expression [

12,

17]. The implementation of CRISPR/Cas9 editing directly in vitro now enables generation of mutant cell lines from individually genotyped embryos, streamlining functional genomics and reducing reliance on animal experimentation [

13].

From a translational perspective, zebrafish cell lines are bridging basic research and clinical innovation. Their conserved signaling networks and drug metabolism profiles support the modeling of human disease variants and compound screening in scalable, ethically favorable systems. However, direct comparison with mammalian models remains limited. Systematic benchmarking of drug metabolism, genome editing fidelity, and stress response dynamics would help define their role in preclinical pipelines and identify context-specific advantages. Future efforts focused on standardizing culture conditions, validating long-term pluripotency, and integrating omics approaches will be crucial to position zebrafish cell lines as robust, reproducible, and versatile tools for personalized medicine, toxicology, and regenerative biology.

7. Generation of Genotype-Defined Zebrafish Cell Lines from Individual Embryos

The establishment of zebrafish cell lines from individually genotyped embryos marks a significant methodological advance in functional genomics. Conventional protocols typically involve pooling dozens or hundreds of embryos from incrosses to ensure sufficient cell yield and promote outgrowth. While effective for wild-type or homogeneous populations, this approach poses limitations when studying early-lethal mutations or phenotypes without overt morphological features, where homozygous mutants cannot be distinguished visually. As a result, generating stable mutant cell lines from such backgrounds has remained a longstanding challenge, restricting in vitro analysis of numerous developmental and disease-related genes.

To address this, Geyer

et al. (2023) introduced a robust and scalable method for deriving zebrafish cell lines from individual 24–36 hpf embryos [

13]. The procedure begins with dechorionation and bleaching of each embryo to reduce microbial contamination. Enzymatic dissociation using pronase and trypsin yields a single-cell suspension, which is seeded into individual wells of a 96-well plate. In parallel, an aliquot of dissociated cells is processed for PCR-based genotyping. This dual workflow enables retrospective identification of the genotype—wild-type, heterozygous, or homozygous mutant—associated with each well, circumventing the need for morphological selection and allowing precise assignment of genetic identity to each culture.

Following genotyping, wells containing cells of the desired genotype can be expanded and, if needed, pooled to establish clonal or monoclonal lines. While not all wells reach confluence, the protocol reports high success rates, with up to 80% of uncontaminated cultures achieving sufficient outgrowth. Crucially, embryos are collected after zygotic genome activation, ensuring transcriptional competence and proliferative capacity in derived cells. This method is particularly advantageous for studying early-lethal mutations or genotypes incompatible with adult viability, offering a direct route to mutant cell lines without the need to maintain or breed homozygous adult fish.

The protocol also provides important ethical and logistical benefits. By eliminating the need to rear embryos to feeding stages or adulthood, it aligns with the 3Rs reducing animal use and potential suffering. Moreover, because the entire procedure occurs before the onset of autonomous feeding, it falls outside the scope of animal experimentation under EU Directive 2010/63/EU, streamlining regulatory requirements while maintaining high ethical standards.

Cell lines derived from single, genotyped embryos are highly suitable for downstream applications such as transcriptomics, genome editing, compound screening, and phenotypic characterization under defined in vitro conditions. Their genetic uniformity enhances reproducibility and facilitates the direct linkage between genotype and cellular phenotype.

In summary, the single-embryo derivation protocol developed by Geyer et al. (2023) opens new avenues for generating genetically defined zebrafish cell lines. It overcomes previous technical and ethical limitations, enabling high-resolution, reproducible studies of mutant phenotypes in a vertebrate system and reinforcing the zebrafish model’s role in scalable, genotype-driven biomedical research.

8. Efficiency and Challenges

The efficiency of establishing and maintaining zebrafish cell lines depends on multiple variables, including the embryonic stage of isolation, enzymatic dissociation methods, medium composition, use of feeder layers, and the capacity of the culture system to preserve both genetic and phenotypic stability over time. Early protocols, such as those described by Collodi

et al. (1992), relied on pooling blastula-stage embryos and employing complex media supplemented with trout serum and embryo extract [

2]. Although these methods produced lines such as ZEM-2 and ZEM-2A, they often lacked reproducibility and scalability.

Subsequent advances—including the use of chemically defined, feeder-free media enriched with fish serum and growth factors like bFGF—have markedly improved culture stability and proliferative capacity. This is exemplified by the successful establishment of ES-like lines such as ZES1 and Z428, which express key pluripotency markers and are maintained over extended passages [

10,

11]. Despite these improvements, several limitations remain that hinder the widespread and standardized use of zebrafish cell lines.

One major concern is genomic instability. Many widely used lines exhibit abnormal karyotypes (

Table 1). For instance, ZF4 is hyperploid, with an average chromosome count of ~120 and ZEM-2A shows a modal number of 77 [

5,

27]. Such chromosomal abnormalities can alter gene expression profiles, cellular behavior, and response to experimental manipulations. This variability poses a significant barrier to reproducibility and highlights the need for routine cytogenetic validation. Without standardized karyotyping or genomic authentication, cross-study comparisons and translational applications may be compromised.

A critical future direction is the implementation of rigorous quality control frameworks for zebrafish cell lines. Unlike mammalian cell culture, where repositories such as European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (ECACC,

https://www.culturecollections.org.uk/ECACC) or American Type Culture Collection (ATCC,

https://www.atcc.org/) require thorough authentication, most zebrafish lines are maintained without formalized validation. This increases the risk of misidentification, contamination, or genetic drift over time. Basic cell line quality assessment should include at minimum: (i) regular mycoplasma testing, (ii) karyotyping to assess chromosomal integrity, (iii) monitoring for phenotypic stability and growth rates, and (iv) molecular authentication using species-specific markers.

To facilitate standardization, we propose a practical checklist of essential quality controls that can be adopted by laboratories working with zebrafish cell lines (

Table 4). Adopting such standards would ensure reproducibility and inter-lab comparability, crucial steps for the zebrafish in vitro model to reach broader acceptance in biomedical research.

Maintaining pluripotency in ES-like lines also remains challenging. Although ZES1 and Z428 exhibit stable expression of canonical transcription factors such as

pou5f1,

nanog, and

sox2, spontaneous differentiation frequently occurs, even under optimized feeder-free and serum-reduced conditions [

10,

11]. This may reflect intrinsic differences in signaling dynamics and chromatin regulation between zebrafish and mammals, or suboptimal adaptation of mammalian ESC culture protocols to teleost systems. While chemically defined media have improved consistency, the field still lacks a zebrafish-specific pluripotency maintenance system analogous to those developed for mouse or human ESCs. Moreover, the absence of feeder cells—though beneficial for ethical and technical reasons—may accelerate loss of stem-like features over time, necessitating regular monitoring of marker expression and differentiation potential.

Transfection efficiency is another technical bottleneck. While lines like ZEM-2A and PAC2 respond well to chemical reagents such as FuGENE HD and Nanofectin [

18,

27], others like ZF4 are refractory to chemical transfection and require electroporation-based methods such as nucleofection [

12]. Variability in transfection outcomes likely arises from differences in membrane composition, chromatin accessibility, or cell cycle status. Moreover, the limited availability of zebrafish-optimized promoters, selection markers, and expression vectors restricts the generalizability of transgenic and gene-editing protocols. Broader access to molecular tools tailored to zebrafish biology would enhance reproducibility and facilitate standardization across laboratories.

Despite these limitations, zebrafish cell lines remain powerful platforms for in vitro research. They offer scalable, cost-effective, and ethically favorable alternatives to animal models in areas such as high-throughput toxicity testing, genetic manipulation, and disease modeling. To fully realize their potential in biomedical research, however, rigorous standardization and quality control are imperative. This includes genomic authentication (e.g., karyotyping, STR profiling), regular mycoplasma testing, documentation of passage number, and functional characterization of stemness and differentiation capacity. The establishment of centralized zebrafish cell line repositories—similar to ATCC or ECACC—would further support reproducibility, reduce redundancy, and promote cross-laboratory consistency.

As zebrafish cell culture technologies continue to evolve, addressing these technical and standardization challenges will be essential to strengthen their role in modern cell biology, functional genomics, and translational applications.

9. Future Perspectives

The continued evolution of zebrafish cell culture hinges on refining existing methodologies while integrating innovative technologies to enhance reproducibility, biological relevance, and translational potential. One of the most immediate priorities is the development of chemically defined, xeno-free media tailored specifically to zebrafish cells. Current reliance on fetal bovine serum (FBS), fish serum, or trout embryo extract introduces batch variability, limits standardization, and raises ethical concerns. Replacing these undefined components with recombinant growth factors and fully defined supplements would promote inter-laboratory reproducibility and align zebrafish systems with regulatory and clinical standards [

10,

11]. Such formulations could also improve the maintenance of pluripotency and enable precise, lineage-directed differentiation under controlled conditions—key requirements for modeling development and disease in vitro.

A promising direction involves the expansion of three-dimensional (3D) culture models, including spheroids and organoids. Zebrafish liver and embryonic cells have already been adapted to 3D formats using hanging-drop systems, hydrogel matrices, and low-adhesion platforms [

15]. These models recapitulate tissue architecture more faithfully than 2D cultures, offering enhanced cellular organization, more physiologically relevant gene expression, and greater utility in toxicology, oncology, and pharmacological testing. The incorporation of co-culture systems—either with different zebrafish lineages or with mammalian cells—adds another layer of complexity, enabling in vitro modeling of intercellular communication, immune interactions, and tumor–stroma dynamics.

Recent advances demonstrate the feasibility of adapting 3D culture techniques and organoid models to zebrafish-derived cell lines. Park

et al. (2022) reported that zebrafish liver and embryonic cell lines such as ZFL and ZEM2S can be cultured under low-attachment conditions using DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, leading to the spontaneous formation of uniform spheroids without additional scaffolds [

43]. This three-dimensional (3D) spheroid-based in vitro platform showed enhanced viability, stable morphology, and increased expression of differentiation-associated markers compared to traditional 2D cultures. Furthermore, hepatic organoids derived from ZFL cells under these conditions displayed apical microvilli and polarized cellular organization, closely resembling in vivo liver architecture.

Despite these promising results, the field remains underdeveloped compared to mammalian organoid systems. Standardized protocols for zebrafish spheroid formation, matrix embedding, and long-term maintenance are lacking, and comparative transcriptomic or functional validation is still rare. Nevertheless, the successful adaptation of organoid technology to zebrafish cell lines offers an unprecedented opportunity to study cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, tissue-specific differentiation, and environmental toxicity in a physiologically relevant context. Looking ahead, the development of advanced zebrafish in vitro models will likely involve the incorporation of three-dimensional (3D) culture systems, organoid technologies, and co-culture platforms. These systems offer enhanced physiological relevance and can better replicate in vivo architecture and signaling gradients. Although 3D culture is well established in mammalian systems, only limited efforts have been made to adapt these strategies to zebrafish-derived cell lines.

Furthermore, integrating transcriptomic and epigenomic profiling (e.g., RNA-seq, ATAC-seq) will be crucial for defining cellular states and regulatory programs. Although RNA-seq has been widely applied to zebrafish-derived cell lines, chromatin accessibility profiling using ATAC-seq remains largely unexplored in these in vitro systems. Recent studies have successfully implemented ATAC-seq in zebrafish embryos, as well as in sorted in vivo cell types such as neurons and osteoblasts, providing valuable insight into gene regulatory elements during development [

44,

45,

46]. However, no studies to date have applied ATAC-seq to zebrafish cell lines such as ZF4, ZFL, or PAC2. This lack of epigenomic data in cell lines represents a major knowledge gap—and an opportunity to explore chromatin remodeling, lineage specification, and responses to environmental stimuli in vitro.

Emerging technologies in synthetic biology, biosensor design, and artificial intelligence (AI) promise to transform zebrafish cell lines into powerful platforms for systems biology and precision medicine. Engineered zebrafish cells carrying synthetic gene circuits could serve as living biosensors for environmental toxins or therapeutic compounds. Simultaneously, AI-driven analysis of high-content imaging and multi-omics data may allow predictive modeling of cellular behaviors, drug responses, or disease states. These advances will depend on expanding the toolkit of zebrafish-specific molecular resources—including inducible promoters, CRISPRa/i systems, and optogenetic modules for spatiotemporal control of gene expression.

The recent development of protocols for deriving cell lines from individually genotyped embryos represents a paradigm shift in functional screening and disease modeling. These monoclonal mutant lines facilitate the study of early-lethal mutations, genotype-specific drug responses, and cell-intrinsic transcriptional phenotypes without requiring large-scale breeding [

13]. When combined with CRISPR-based genome editing and single-cell transcriptomics, such systems offer high-resolution interrogation of gene function, epistatic interactions, and regulatory pathways in a vertebrate model.

Importantly, zebrafish cell cultures align closely with the ethical principles of the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement). Their derivation from early-stage embryos, compatibility with multiwell formats, and scalability for high-throughput assays reduce the need for live animal experimentation. As global regulatory frameworks increasingly encourage non-mammalian alternatives for toxicity and efficacy testing, zebrafish-derived lines may fill a critical niche between mammalian cell cultures and whole-organism models.

In conclusion, zebrafish cell lines are rapidly transitioning from experimental platforms to foundational tools in developmental biology, toxicology, oncology, and regenerative medicine. With ongoing progress in culture standardization, genomic fidelity, and functional validation, these models are poised to play a central role in modern biomedical research. Their unique combination of vertebrate-specific features, genetic accessibility, scalability, and ethical compatibility makes them ideal candidates for next-generation in vitro systems bridging basic science and translational innovation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Á.J.A. and L.S.; methodology, Á.J.A. and L.G.L.; investigation, Á.J.A. and L.G.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Á.J.A.; writing—review and editing, Á.J.A. and L.G.L.; supervision, L.S. and A.B.; project administration, L.S. and A.B.; funding acquisition, X.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by NAME OF FUNDER, grant number XXX” and “The APC was funded by XXX”. Check carefully that the details given are accurate and use the standard spelling of funding agency names at

https://search.crossref.org/funding. Any errors may affect your future funding.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3Rs |

Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement |

| AP |

Alkaline Phosphatase |

| ALP |

Alkaline Phosphatase |

| ATAC-seq |

Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing |

| ATCC |

American Type Culture Collection |

| bFGF |

Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| CD24 |

Cluster of Differentiation 24 |

| CMV |

Cytomegalovirus (viral promoter) |

| CRISPR |

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| CRISPRa/i |

CRISPR activation/interference |

| ctgfa |

Connective Tissue Growth Factor a |

| CYP1A1 |

Cytochrome P450 1A1 |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| DMEM/F12 |

DMEM supplemented with Ham’s F12 Nutrient Mix |

| DRCF |

Danio rerio Caudal Fin cell line |

| ECACC |

European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures |

| ESC |

Embryonic Stem Cell |

| FBS |

Fetal Bovine Serum |

| fli1 |

Friend Leukemia Virus Integration 1 |

| G418 |

Geneticin (aminoglycoside antibiotic) |

| gdf3 |

Growth Differentiation Factor 3 |

| GFP |

Green Fluorescent Protein |

| HEPES |

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (buffering agent) |

| hESC |

Human Embryonic Stem Cell |

| hpf |

Hours Post-Fertilization |

| kdr |

Kinase Insert Domain Receptor (VEGFR2) |

| klf4 |

Kruppel-like Factor 4 |

| KO |

Knockout |

| L-15 |

Leibovitz’s L-15 Medium |

| lin28 |

LIN28 Homolog A |

| MPC |

2-methacryloxyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine |

| nanog |

Homeobox protein Nanog |

| oct4 |

Octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (pou5f1) |

| PAC2 |

Zebrafish embryonic fibroblast cell line derived from 24 hpf embryos |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| pEGFP-N1 |

Plasmid expressing Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein under CMV promoter |

| PGC |

Primordial Germ Cell |

| pou5f1 |

POU domain class 5 transcription factor 1 |

| ronin |

Required for Nuclear Factor Activation in Stem Cells |

| RSV |

Rous Sarcoma Virus |

| RTS34st |

Rainbow Trout Spleen Stromal Cell Line |

| sall4 |

Spalt Like Transcription Factor 4 |

| SDF-1b |

Stromal Cell-Derived Factor 1 beta |

| sox2 |

SRY-box Transcription Factor 2 |

| SSEA |

Stage-Specific Embryonic Antigen |

| STR |

Short Tandem Repeat |

| TCDD |

2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin |

| tcf3 |

Transcription Factor 3 |

| tdgf1 |

Teratocarcinoma-Derived Growth Factor 1 |

| Tol2 |

Transposon originally from Oryzias latipes |

| TRA-1-60/81 |

Tumor-Related Antigens |

| vasa |

DEAD-box Helicase 4 (germ cell marker) |

| zPDX |

Zebrafish Patient-Derived Xenograft |

| Z428 |

Zebrafish embryonic stem-like cell line |

| ZBE3 |

Zebrafish Blastula-derived Embryonic cell line with high transfection efficiency |

| ZEB2J |

Zebrafish Embryonic Blastula-derived cell line adapted from co-culture |

ZEM-2

ZEM-2A

ZEM2S |

Zebrafish Embryonic cell lines with varying serum/media conditions |

| ZES1 |

Zebrafish embryonic stem-like cell line |

| ZF4 |

Zebrafish Fibroblast cell line |

| ZFL |

Zebrafish Liver cell line |

References

- Bradford, C.S.; Sun, L.; Collodi, P.; Barnes, D.W. Cell Cultures from Zebrafish Embryos and Adult Tissues. J. Tissue Cult. Methods 1994, 16, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collodi, P.; Kame, Y.; Ernst, T.; Miranda, C.; Buhler, D.R.; Barnes, D.W. Culture of Cells from Zebrafish (Brachydanio Rerio) Embryo and Adult Tissues. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 1992, 8, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, K.; Clark, M.D.; Torroja, C.F.; Torrance, J.; Berthelot, C.; Muffato, M.; Collins, J.E.; Humphray, S.; McLaren, K.; Matthews, L.; et al. The Zebrafish Reference Genome Sequence and Its Relationship to the Human Genome. Nature 2013, 496, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Lin, J.; Chen, Q.; Lv, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wen, X.; Lin, F. An Efficient Vector-Based CRISPR/Cas9 System in Zebrafish Cell Line. Mar. Biotechnol. 2024, 26, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driever, W.; Rangini, Z. Characterization of a Cell Line Derived from Zebrafish (Brachydanio Rerio) Embryos. Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. - Anim. 1993, 29, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, C.; Zhou, Y.L.; Collodi, P. Derivation and Characterization of a Zebrafish Liver Cell Line. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 1994, 10, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, C.; Liu, Y.; Ma, C.; Collodi, P. Cell Cultures Derived from Early Zebrafish Embryos Differentiate in Vitro into Neurons and Astrocytes.

- Fan, L.; Moon, J.; Wong, T.-T.; Crodian, J.; Collodi, P. Zebrafish Primordial Germ Cell Cultures Derived from Vasa::RFP Transgenic Embryos. Stem Cells Dev. 2008, 17, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarlo, C.A.; Zon, L.I. Embryonic Cell Culture in Zebrafish. In Methods in Cell Biology; Elsevier, 2016; Vol. 133, pp. 1–10 ISBN 978-0-12-803475-0.

- Ho, S.Y.; Goh, C.W.P.; Gan, J.Y.; Lee, Y.S.; Lam, M.K.K.; Hong, N.; Hong, Y.; Chan, W.K.; Shu-Chien, A.C. Derivation and Long-Term Culture of an Embryonic Stem Cell-Like Line from Zebrafish Blastomeres Under Feeder-Free Condition. Zebrafish 2014, 11, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, N.; Schartl, M.; Hong, Y. Derivation of Stable Zebrafish ES-like Cells in Feeder-Free Culture. Cell Tissue Res. 2014, 357, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badakov, R.; Jaźwińska, A. Efficient Transfection of Primary Zebrafish Fibroblasts by Nucleofection. Cytotechnology 2006, 51, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, N.; Kaminsky, S.; Confino, S.; Livne, Z.B.-M.; Gothilf, Y.; Foulkes, N.S.; Vallone, D. Establishment of Cell Lines from Individual Zebrafish Embryos. Lab. Anim. 2023, 57, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizgirev, I.; Revskoy, S. Generation of Clonal Zebrafish Lines and Transplantable Hepatic Tumors. Nat. Protoc. 2010, 5, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, I.R.; Micali Canavez, A.D.P.; Schuck, D.C.; Costa Gagosian, V.S.; De Souza, I.R.; De Albuquerque Vita, N.; Da Silva Trindade, E.; Cestari, M.M.; Lorencini, M.; Leme, D.M. A 3D Culture Method of Spheroids of Embryonic and Liver Zebrafish Cell Lines. J. Vis. Exp. 2023, 64859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamei, Y.; Collodi, P.; Ernst, T.; Barnes, D.W. CULTURE OF CELLS FROM ADULT ZEBRAFISH (BRACHYDANIO RERIO) AND EMBRYO. In Animal Cell Technology; Elsevier, 1992; pp. 17–19 ISBN 978-0-7506-0421-5.

- Meena, L.L.; Goswami, M.; Chaudhari, A.; Nagpure, N.S.; Gireesh-Babu, P.; Dubey, A.; Das, D.K. Development and Characterization of a New DRCF Cell Line from Indian Wild Strain Zebrafish Danio Rerio (Hamilton 1822). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 46, 1337–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallone, D.; Santoriello, C.; Gondi, S.B.; Foulkes, N.S. Basic Protocols for Zebrafish Cell Lines.

- Jin, Y.L.; Chen, L.M.; Le, Y.; Li, Y.L.; Hong, Y.H.; Jia, K.T.; Yi, M.S. Establishment of a Cell Line with High Transfection Efficiency from Zebrafish Danio Rerio Embryos and Its Susceptibility to Fish Viruses. J. Fish Biol. 2017, 91, 1018–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choorapoikayil, S.; Overvoorde, J.; Den Hertog, J. Deriving Cell Lines from Zebrafish Embryos and Tumors. Zebrafish 2013, 10, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.G.; Lee, L.E.J.; Fan, L.; Collodi, P.; Holt, S.E.; Bols, N.C. Initiation of a Zebrafish Blastula Cell Line on Rainbow Trout Stromal Cells and Subsequent Development Under Feeder-Free Conditions into a Cell Line, ZEB2J. Zebrafish 2008, 5, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Fan, L.; Ganassin, R.; Bols, N.; Collodi, P. Production of Zebrafish Germ-Line Chimeras from Embryo Cell Cultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001, 98, 2461–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Crodian, J.; Collodi, P. Production of Zebrafish Germline Chimeras by Using Cultured Embryonic Stem (ES) Cells. In Methods in Cell Biology; Elsevier, 2004; Vol. 77, pp. 113–119 ISBN 978-0-12-564172-2.

- Senghaas, N.; Köster, R.W. Culturing and Transfecting Zebrafish PAC2 Fibroblast Cells. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2009, 2009, pdb.prot5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Salas-Vidal, E.; Rueb, S.; Krens, S.F.G.; Meijer, A.H.; Snaar-Jagalska, B.E.; Spaink, H.P. Genetic and Transcriptome Characterization of Model Zebrafish Cell Lines. Zebrafish 2006, 3, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culp, P.; Nüsslein-Volhard, C.; Hopkins, N. High-Frequency Germ-Line Transmission of Plasmid DNA Sequences Injected into Fertilized Zebrafish Eggs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1991, 88, 7953–7957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, C.; Collodi, P. Culture of Cells from Zebrafish (Brachydanio Rerio) Blastula-Stage Embryos. Cytotechnology 1994, 14, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Xu, W.; Xiang, S.; Tao, L.; Fu, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, W.; Xiao, Y.; Peng, L. Defining the Pluripotent Marker Genes for Identification of Teleost Fish Cell Pluripotency During Reprogramming. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 819682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, V.; Martí, M.; Belmonte, J.C.I. Study of Pluripotency Markers in Zebrafish Embryos and Transient Embryonic Stem Cell Cultures. Zebrafish 2011, 8, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, J.-M.; Gerbal-Chaloin, S.; Milhavet, O.; Qiang, B.; Becker, F.; Assou, S.; Lemaître, J.-M.; Hamamah, S.; De Vos, J. Brief Report: Benchmarking Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Markers During Differentiation Into the Three Germ Layers Unveils a Striking Heterogeneity: All Markers Are Not Equal. Stem Cells 2011, 29, 1469–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Gao, M.; Gao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Hong, Q.; Li, Z.; Yao, J.; Cheng, H.; Zhou, R. Directed Differentiation of Zebrafish Pluripotent Embryonic Cells to Functional Cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Rep. 2016, 7, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Angeles, A.; Ferrari, F.; Xi, R.; Fujiwara, Y.; Benvenisty, N.; Deng, H.; Hochedlinger, K.; Jaenisch, R.; Lee, S.; Leitch, H.G.; et al. Hallmarks of Pluripotency. Nature 2015, 525, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailovic, S.; Wolff, S.C.; Kedziora, K.M.; Smiddy, N.M.; Redick, M.A.; Wang, Y.; Lin, G.K.; Zikry, T.M.; Simon, J.; Ptacek, T.; et al. Single-Cell Dynamics of Core Pluripotency Factors in Human Pluripotent Stem Cells 2022.

- Bertero, A.; Madrigal, P.; Galli, A.; Hubner, N.C.; Moreno, I.; Burks, D.; Brown, S.; Pedersen, R.A.; Gaffney, D.; Mendjan, S.; et al. Activin/Nodal Signaling and NANOG Orchestrate Human Embryonic Stem Cell Fate Decisions by Controlling the H3K4me3 Chromatin Mark. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 702–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Schartl, M. Isolation and Differentiation of Medaka Embryonic Stem Cells. In Embryonic Stem Cell Protocols; Humana Press: New Jersey, 2006; Volume 329, pp. 3–16. ISBN 978-1-59745-037-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Manali, D.; Wang, T.; Bhat, N.; Hong, N.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Yan, Y.; Liu, R.; Hong, Y. Identification of Pluripotency Genes in the Fish Medaka. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2011, 7, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. -L.; Ye, H. -Q.; Sha, Z. -X.; Hong, Y. Derivation of a Pluripotent Embryonic Cell Line from Red Sea Bream Blastulas. J. Fish Biol. 2003, 63, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, A.V.; Camp, E.; Mullor, J.L. Fishing Pluripotency Mechanisms In Vivo. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2011, 7, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putri, R.R.; Ayisi, C.L. Transfection Of Difficult-To-Transfect Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) ZF4 Cells Using Chemical Transfection and Nucleofection Method. Juv. Ilm. Kelaut. Dan Perikan. 2023, 4, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuta, H.; Kawakami, K. Transient and Stable Transgenesis Using Tol2 Transposon Vectors. In Zebrafish; Lieschke, G.J., Oates, A.C., Kawakami, K., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2009; Volume 546, pp. 69–84. ISBN 978-1-60327-976-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lungu-Mitea, S.; Lundqvist, J. Potentials and Pitfalls of Transient in Vitro Reporter Bioassays: Interference by Vector Geometry and Cytotoxicity in Recombinant Zebrafish Cell Lines. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 2769–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Renzo, M.F.; Corso, S. Patient-Derived Cancer Models. Cancers 2020, 12, 3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.G.; Ryu, C.S.; Sung, B.; Manz, A.; Kong, H.; Kim, Y.J. Transcriptomic and Physiological Analysis of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals Impacts on 3D Zebrafish Liver Cell Culture System. Aquat. Toxicol. 2022, 245, 106105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Luan, Y.; Liu, T.; Lee, H.J.; Fang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Jin, Q.; Ang, K.C.; et al. A Map of Cis-Regulatory Elements and 3D Genome Structures in Zebrafish. Nature 2020, 588, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petratou, K.; Stehling, M.; Müller, F.; Schulte-Merker, S. Integration of ATAC and RNA-Sequencing Identifies Chromatin and Transcriptomic Signatures in Classical and Non-Classical Zebrafish Osteoblasts and Indicates Mechanisms of Entpd5a Regulation 2025.

- Quillien, A.; Abdalla, M.; Yu, J.; Ou, J.; Zhu, L.J.; Lawson, N.D. Robust Identification of Developmentally Active Endothelial Enhancers in Zebrafish Using FANS-Assisted ATAC-Seq. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).