1. Introduction

Distant metastatic disease has historically been treated as incurable disease, however the concept of the oligometastatic state with the potential for long-term disease control is now widely accepted. Surgical and non-surgical techniques are used with curative intent for treatment of oligometastases throughout the body, with a growing body of evidence for its survival benefit. Focusing specifically on lung metastases, The International Registry of Lung Metastases [1] (IRLM) demonstrated in 1999 the significant survival benefit gained from resection. PulMiCC was a two-arm randomized controlled trial in colorectal cancer patients looking at whether adding metastasectomy to active monitoring improved survival [2]. This study was underpowered due to poor recruitment, failing to show survival benefit, with 95% confidence interval of hazard ratio for overall survival crossing 1. Metastasectomy continues to be performed in routine clinical practice. For patients who are not suitable candidates for surgery, ablative techniques are widely used. However, it is not known which, if any, of these techniques are superior to another, or whether we should be selecting certain patient groups for a particular treatment modality, thereby individualising patient care.

The rationale for the use of non-surgical ablative techniques is that the existing data demonstrates similar efficacy and long-term survival to the surgically treated patients in the IRLM [3,4]. Furthermore, these techniques carry minimal morbidity with acceptable toxicity profiles. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA), stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy (SBRT), microwave ablation (MWA) and cryoablation are widely used, with the largest body of evidence supporting the first two techniques [5–22]. Existing literature largely comprise of outcomes following treatment with single modality such as SBRT or RFA. Comparison of ablative techniques in the literature are limited to tumour-site specific case series [23].

With the current lack of randomised evidence to direct treatment selection, we aim to identify disease or patient-related factors which affect the choice of treatment. In addition, we hope to identify factors which may support one modality treatment over the other. In this retrospective study, we present the baseline characteristics of patients treated with RFA or SBRT for lung metastases at our institution. We report long-term outcomes with each treatment modality and review any potential correlation between baseline characteristics and any observed differences in outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

We included all patients who underwent RFA or SBRT for treatment of a lung metastasis between November 2011 and December 2019 at our institution, following institutional Research and Development committee approval. As the primary objective assessed was local progression-free survival (PFS), patients required at least one follow-up CT scan at 3 months after treatment to be included.

The following data was collected retrospectively using electronic patient records (EPR): age, gender, primary diagnosis, date of treatment, number of lesions treated simultaneously, size of metastases, acute and late (≥3 months post treatment) toxicities (CTCAE v4.0), ECOG performance status, oligometastatic status at the time of local intervention (up to 3 sites of extracranial metastases), time to local and distant progression, site of distant progression, date of death and any systemic treatment preceding or following the current therapy.

“Local treatment” included surgery and non-surgical techniques comprising RFA or SBRT. Synchronous extrapulmonary disease was recorded as “amenable to local treatment” if the disease was treated prior to the lung treatment, or if local treatment was planned to take place following the lung treatment. Any systemic treatment that was given prior to or following the RFA or SBRT episode was recorded, regardless of time interval from the episode being evaluated. Biologically Effective Dose (BED) was calculated with the following formula: BED= Total dose x (1 + (Dose per fraction/alpha-beta ratio)).

2.2. Imaging Review

All imaging was reviewed by two independent consultant radiologists specifically for the purpose of this evaluation to assess tumour size, site and local control. Local progression was defined for RFA patients as per Lencioni et al. as any increase in the ablation zone of the baseline CT done 4-6 weeks post ablation, any new enhancement of the ablation zone or more than 20% increase of the treated lesions (using modified RECIST criteria) [24]. For SBRT patients the criteria as defined by Huang et al. were used [25]. PFS was defined as the time from the start of the initial treatment to date of either local or distant progression, whichever was earlier. Distant progression was defined as progression of any disease outside of the lesion being treated.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated for each of the baseline characteristics, adverse events, and other outcome data, presented both overall and by treatment cohort. The categorical groups were compared using the Chi squared test for independence, using a 95% confidence interval. Numerical groups were compared using a non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test due to skewed data.

Local progression, distant progression and overall survival were estimated using the Kaplan Meier method, and the log rank test was used for comparison by treatment cohort, p≤0.05 was considered significant. Patients who did not experience event of interest were censored at their last follow-up date. Subgroups of interest (primary diagnosis (colorectal vs others) and largest treated lesion size (≤20mm vs >20mm) were also examined using these methods. Local progression-free survival (LPFS) was defined as being progression-free in the treatment field, and PFS as being progression-free in local and distant sites.

Univariable models were first constructed with treatment cohort as the only covariate. Subsequent univariate models looked at each of the other prognostic factors separately, adjusting for treatment cohort. Prognostic factors of interest were: lesion size (<=20mm vs >20mm), previous systemic anti-cancer therapy (SACT), subsequent SACT, oligometastatic disease, >1 lesion treated simultaneously, colorectal vs non-colorectal primary. Following this, a multivariable model was constructed using a backwards elimination stepwise procedure, with a p-value cutoff of 0.05. All of the variables in univariable analysis were considered for the final multivariable model, with treatment cohort, lesion size, and colorectal primary being forced into the model irrespective of statistical significance.

The final model after this model-fitting process is presented with adjusted hazard ratios and the p-value associated with each term in the model. Statistically significant variables at the 5% level are highlighted.

Stata 18 software was used to perform all statistical analyses (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Demographics

We retrospectively identified 106 patients who received RFA and 70 patients treated with SBRT. The baseline characteristics and differences are highlighted in

Table 1. The SBRT cohort contained mostly oligometastatic patients (91.4%) whereas 20% treated with RFA were oligometastatic (

Table 1). The SBRT cohort had larger tumours treated (median size 18 vs 11mm), more male in the cohort (63.4 vs 50%). The RFA cohort were younger (median age 65 vs 70.5), more likely to have more than one lesion treated simultaneously (27.4% vs 12.9%). The RFA cohort also received more systemic therapy, both before (76 vs 55.7%) and after local ablative treatment (72 vs 51.4%).

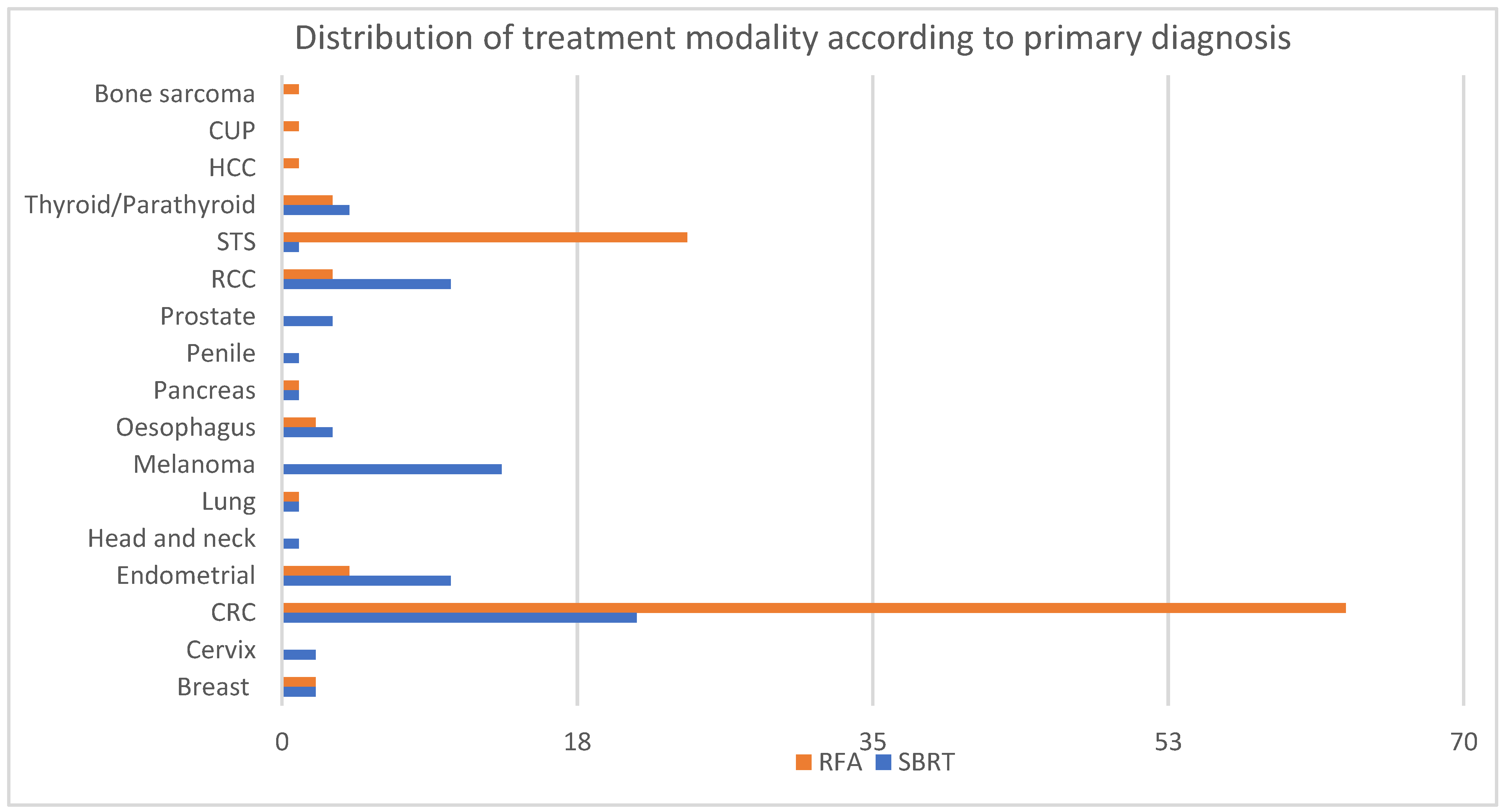

The most commonly treated primaries were patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) and soft tissue sarcoma (STS) primaries (47.7% and 14.2% respectively), followed by endometrial cancer, melanoma and renal cell carcinoma (RCC) (8%, 7.4% and 7.4% respectively). The distribution of primary diagnoses differed between the two treatment modalities (

Figure 1). The majority of patients with melanoma (100%), RCC (77%) and endometrial cancer (71%) were treated with SBRT. On the other hand, patients with STS (96%) and CRC (75%) were preferentially treated with RFA.

3.2. Adverse Events

In the SBRT group, 51.4% experienced grade 1-2 acute toxicity, fatigue being the commonest (37.1%), followed by cough (12.8%). One patient (2.9%) experienced grade 3 or greater acute toxicity. Eight patients (11.4%) experienced grade 1-2 late toxicity, with three patients developing grade 1-2 pneumonitis. One patient (2.9%) experienced grade 3 pneumonitis. This patient had been treated with Cyberknife, 54Gy in 3 fractions, and pneumonitis occurred 4 months following SBRT. No other late grade >=3 toxicities were recorded in the SBRT group.

In the RFA group, 49% of patients experienced grade 1-2 acute toxicity with grade 1-2 pneumothorax being the most common complication (44.3% of the patients). None of these patients required hospitalization. Eight patients (7.5%) experienced grade 3 or greater acute toxicity. Four patients had grade 3 pneumothorax, two patients had a grade 4 chest infection, one patient had haemothorax, and one patient had grade 3 pericardial puncture. One patient had a contained air-embolism with air in the pulmonary veins and left atrium but no systemic embolism. This last patient developed a chronic necrotizing pneumonia and aspergillosis at the site of the ablation zone. In terms of late toxicity, only one patient had G1 dyspnoea.

3.3.1. Local Control by Primary Site

Local control (LC) was similar with both treatment modalities in breast, endometrial and RCC (

Table S1). Colon and rectal cancer patients achieved better LC with RFA compared to SBRT (LC 89.7% vs 64.2% and 96.2% vs 71.4% respectively).

3.3.2. Local Control with SBRT by Biologically Effective Dose (BED)

The most common dose regimen used was 60Gy in 8 fractions (36.1%), followed by 55Gy in 5, 54Gy in 3, and 50Gy in 5 (27.8%, 20.8 and 6.9% respectively). As biologically effective doses vary widely depending on the primary site being treated, BED delivered was calculated with the following alpha-beta ratios: 1.5 for Prostate, 2 for adenoid cystic, 2.5 for melanoma, 3 for RCC and thyroid papillary carcinoma, 4 for breast and sarcoma, and 10 for colorectal, oesophageal, cervical, endometrial and pancreatic cancer.

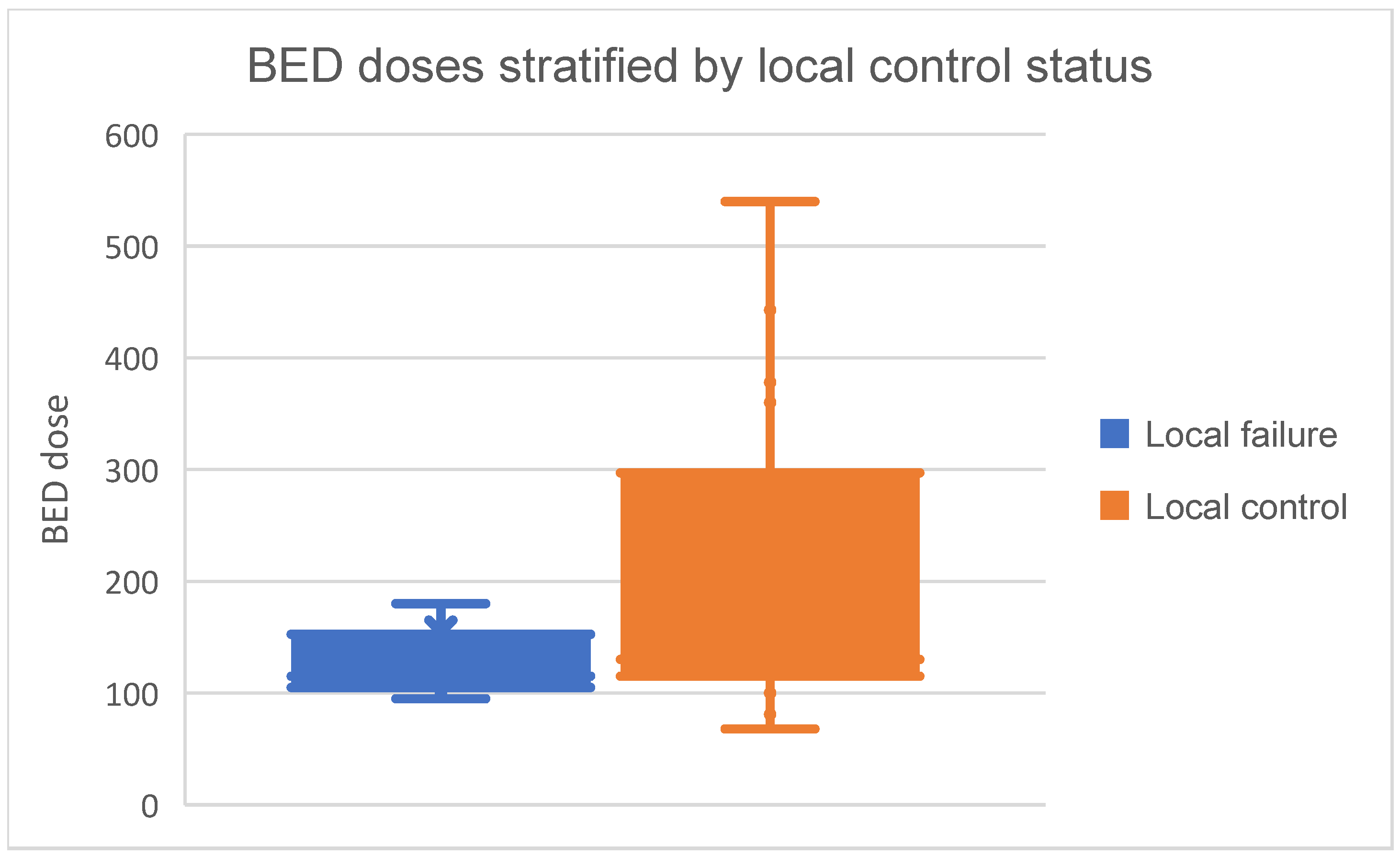

Median BED dose prescribed was 127Gy (range= 68-540Gy, interquartile range (IQR)= 108.5-240Gy). BED doses in those with local control and local failure are visually presented as Box and whisker plot in

Figure 2. Among those with local control, median BED dose prescribed was 130Gy (IQR= 115-297Gy. Patients with local failure generally received lower BED doses, with a median of 115Gy (IQR= 105-152.5Gy). Median BED dose prescribed to colorectal lung metastases was 105Gy (IQR= 105-115Gy).

3.4. Progression-Free Survival and Overall Survival

3.4.1. Local PFS

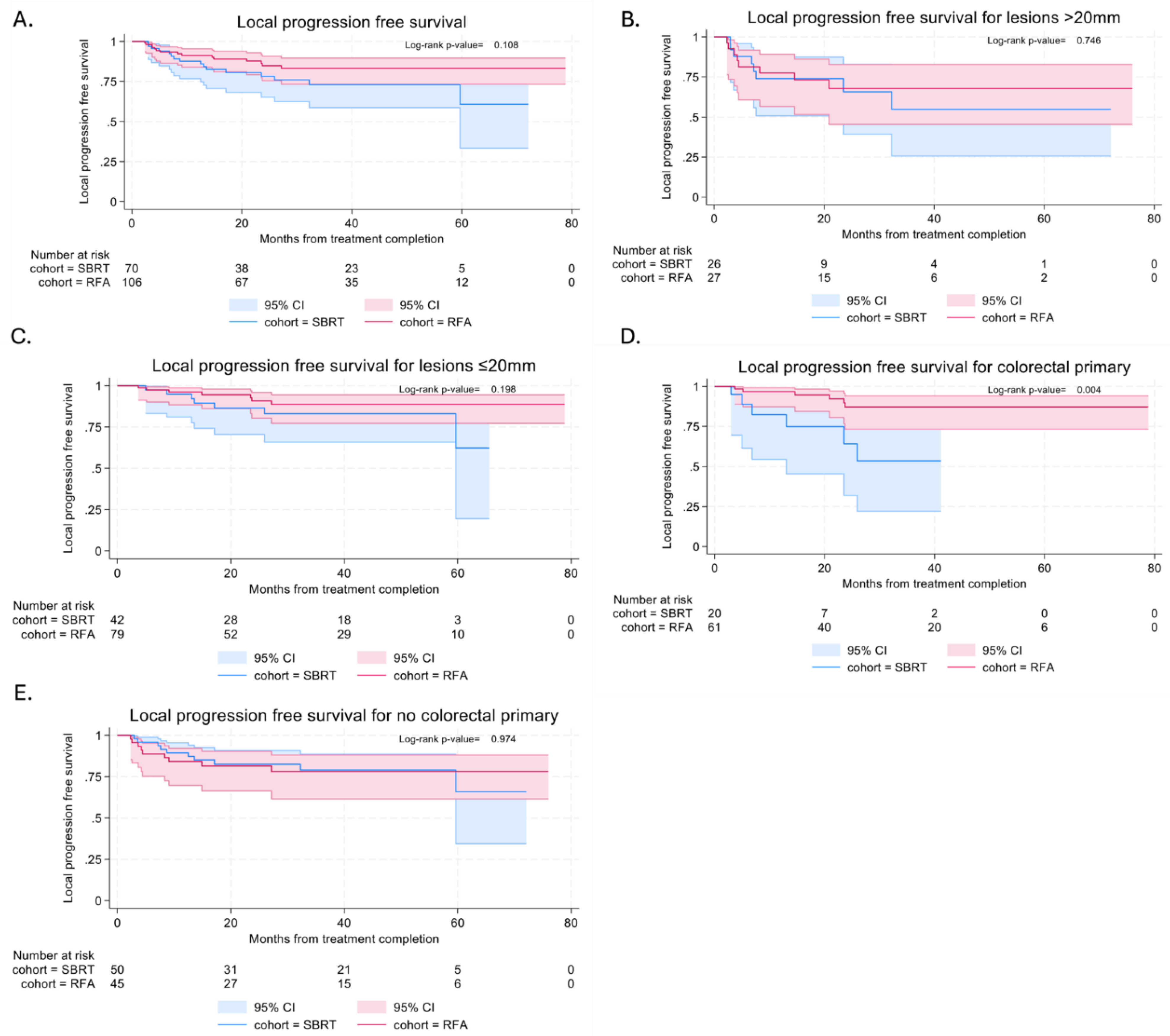

Local PFS (LPFS) was similar in both SBRT and RFA cohorts, with median time to local progression not reached in either cohort (

Figure 3a). In the SBRT cohort, local PFS at 6 and 12 months were 94.0% (95% CI: 84.7%-97.7%) and 87.6% (95% CI: 76.7%-93.6%). In the RFA cohort, local PFS at 6 and 12 months were 93.3% (95% CI: 86.5%-96.8%) and 91.3% (95% CI: 83.9%-95.4%).

Subgroup analysis of lesions stratified by size (<=20mm vs >20mm) showed similar LPFS with both techniques in both smaller (p=0.198) and larger lesions (p=0.746) (

Figure 3b and 3c). In view of the difference in local control between colorectal patients treated with RFA and SBRT, subgroup analysis was also performed. This showed better LPFS in colorectal patients treated with RFA (p=0.004) and this effect was not maintained in non-colorectal patients (p=0.974) (

Figure 3d and 3e).

3.4.2. Progression-Free Survival

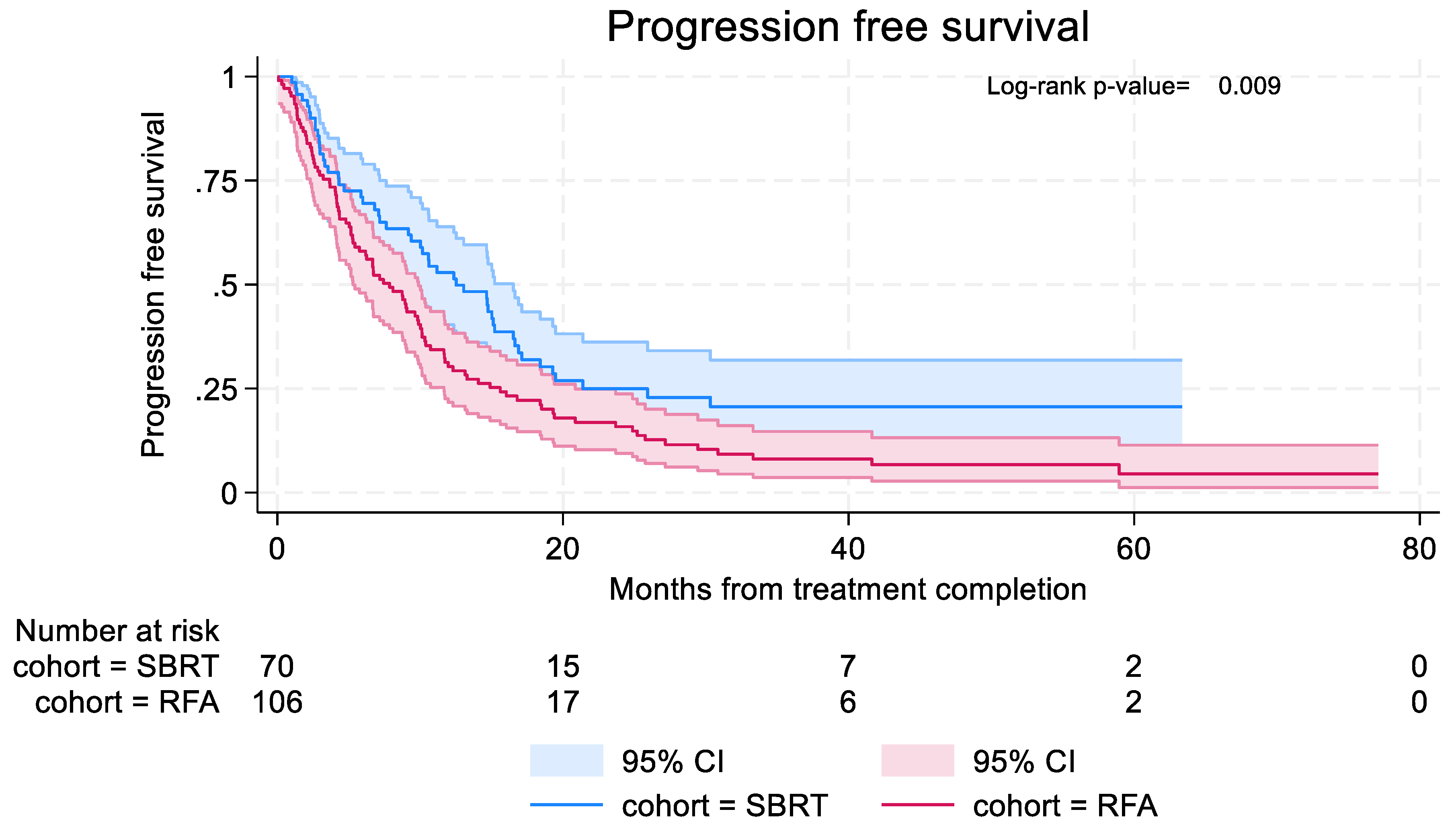

Time to distant or local progression was longer in the SBRT cohort, with median time to progression 12.5 months (95% CI: 9.2–16.5) in the SBRT cohort compared to 7.9 months (95% CI: 5.3–9.9) in the RFA cohort (

Figure 4). In the SBRT cohort, 6-month and 12-month PFS were 69.5% (95% CI: 57.1% - 79.0%) and 52.9% (95% CI: 40.3% - 63.9%) respectively. In the RFA cohort, 6-month and 12-month PFS were 58.0% (95% CI: 48.0%-66.8%) and 30.3% (95% CI: 21.7% - 39.3%) respectively.

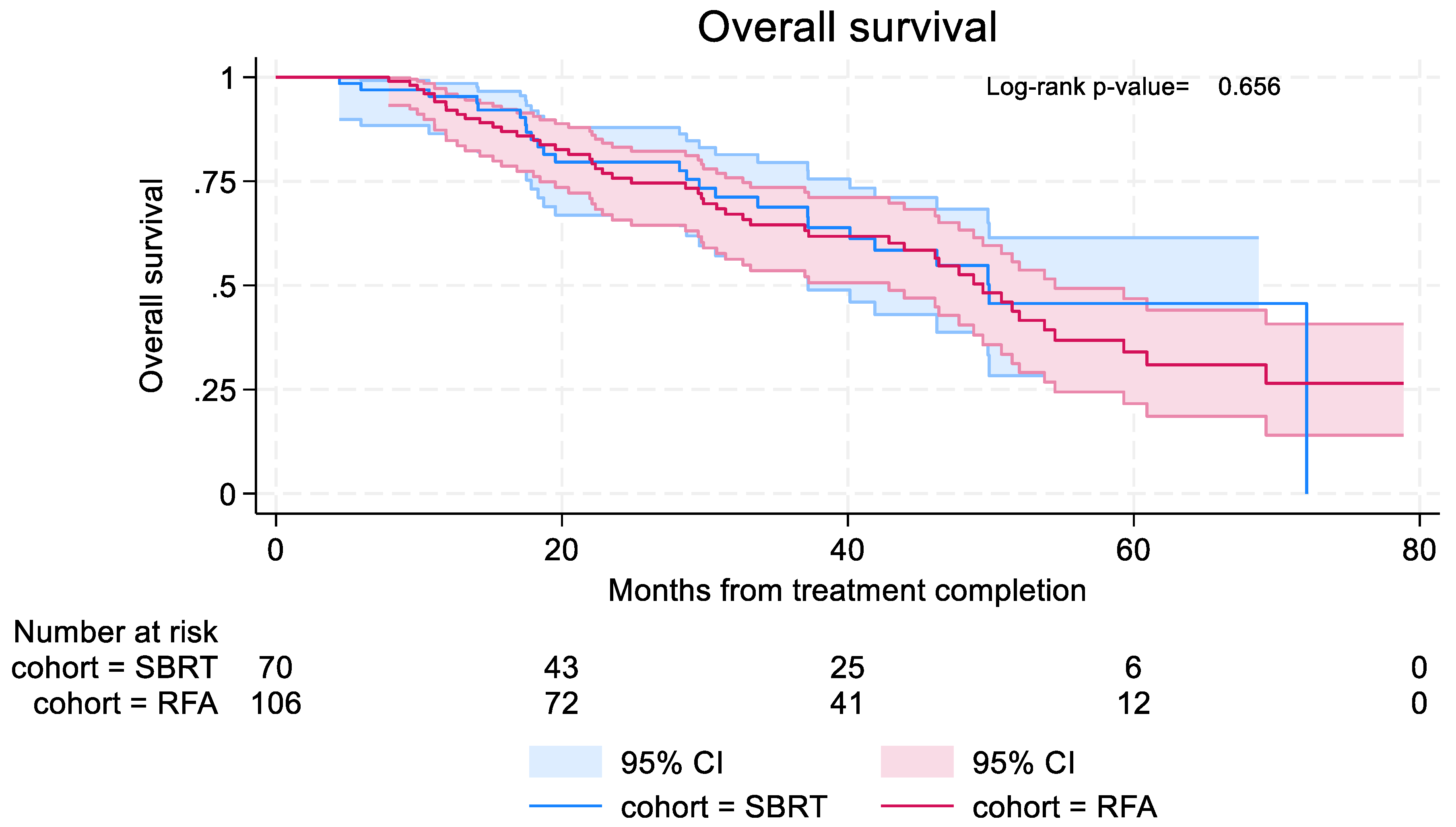

3.4.3. Overall Survival

Overall survival was similar in both groups, with median OS 49.9 months (95% CI: 37.2–not reached) in the SBRT group and 49.4 months (95% CI: 42.93 – 54.5) in RFA group (

Figure 5). In the SBRT cohort, 6-month and 12-month OS were 97.0% (95% CI: 88.4%-99.2%) and 95.4% (95% CI: 86.4%-98.5%). In the RFA cohort, 6-month and 12 month OS were 100% and 92.1% (95% CI: 84.8%-96.0%).

3.5.1. Univariable and Multivariable Analysis

Univariable analysis identified two factors potentially associated with adverse outcomes, independent of ablative treatment: i) lesions >20mm and ii) those who required SACT following treatment (

Table S2). In multivariable analysis, lesions >20mm remained statistically significant in adverse local PFS (HR 3.28 (95% CI: 1.59-6.78)), PFS (HR 1.47 (95%CI: 1.03-2.11)) and OS (HR 2.22 (95% CI: 1.38-3.58)) (

Table S2). Patients requiring no subsequent SACT also remained significant in predicting improved PFS (HR 0.48 (95% CI: 0.32-0.70)).

3.5.2. Cox Regression with Interaction Effects

No statistically significant interaction effects were found between lesion size and treatment cohort. For patients with colorectal primaries, those who received RFA had better local control than SBRT (HR 0.21 (HR 0.05-0.90)), p=0.035. Lesion size >20mm maintained statistical significance in predicting worse PFS and OS (

Table S2).

4. Discussion

Ablation of lung oligometastases is a potential life-prolonging treatment, as supported by the survival benefits reported in the long-term follow up of two randomized phase II trials [5,6]. We have observed differences in selection of patients for treatment with either RFA or SBRT at our institution. Almost all sarcoma patients were treated with RFA (96%), as were the majority of colorectal patients (75%). A substantial body of evidence supports RFA [7–12], but also SBRT in these patients [6,13–20]. Conversely, all melanoma patients at our institution were treated with SBRT. There is limited evidence specifically reviewing the use of either RFA or SBRT in melanoma patients [21,22], therefore it would be justifiable to use either. This may partly be explained by the specialties represented within tumour site-specific multidisciplinary teams.

There are other factors which may lead clinicians to preferentially choose RFA for patients. In the UK, funding may play a significant role: the NHS Clinical Commissioning Policy [26] (previously the Commissioning Through Evaluation Programme) only allows up to three separate metastases to be treated by SBRT (metachronous presentation). This means that if patients have multiple metastases at baseline or are predicted to have multiple lesions in the future, clinicians may be less inclined or unable to choose SBRT as the single modality of treatment, within the NHS. Clinical factors include i) size – lesions smaller than 5mm are technically difficult to treat with SBRT; and 2) the potential requirement for multiple ablative treatments to the lung may favour RFA as the treatment of choice. The latter is likely to be due to the uncertainties surrounding the safety of retreatment with SBRT or treatment of multiple lesions [27,28], particularly with respect to pulmonary toxicity, as well as the restrictions imposed by funding. With the high frequency of lung metastases and recurrences in STS, this may explain why RFA is preferentially used at our institution.

We observed that more RFA patients received systemic therapy, both prior to and after receiving RFA. This cohort contained fewer patients with oligometastatic disease. This may also reflect the initial decision-making process: that patients predicted to have a high chance of lung recurrence may have been preferentially treated with RFA due to the aforementioned concerns surrounding retreatment with SBRT. These patients would have also been more likely to require systemic therapy.

The excellent local control observed in the RFA group may have been confounded by a number of factors, including tumour size or histological primary. The lesions treated with RFA were overall smaller than those treated with SBRT – the smallest lesion being 3mm, and median diameter 11mm. Larger tumours have been associated with poorer prognosis regardless of treatment modality: poorer local control [28], PFS [7,8,11,20], and OS [8,11,12,18,20]. Multivariate analyses in our series confirmed larger lesions independently predict worse local PFS, PFS and OS.

Looking at histological primary, the majority of the local failures within the SBRT group were with colorectal cancer patients. This correlates with findings from a meta-analysis which found the local control rate of treated colorectal lung metastases to be 60% at three years [30]. Furthermore, colorectal metastases may be more radioresistant than metastases from other primary malignancies. This is supported by the findings from a study exploring the radiobiological parameters for lung and liver metastases, which looked at over 3000 metastases from 62 studies, and found that colorectal metastases were estimated to have a higher alpha/beta ratio [31]. This group achieved better local control with RFA in our series. Higher BED doses may achieve better control if SBRT were to be used, similar to that of melanoma and RCC [32–36]. This is also supported by our finding that those with local relapse received a lower median BED dose (115 vs 130Gy).

Other than size, differences in systemic treatment, rates of oligometastatic disease, and histology, the differential lesional local control observed between the RFA and SBRT patients may be explained by the difficulties with radiological assessment. As previously highlighted, it can be difficult to differentiate between radiation-induced lung injury and progression, and there may be a tendency to err on the side of caution and diagnose recurrence. We attempted to eliminate this potential for overdiagnosis by independently reviewing all imaging from all patients in both groups with two radiologists, using the High-Risk Factors as proposed by Huang and colleagues [6] for those treated with SBRT. PET-CT or histological confirmation were used to confirm local progression in our series. Despite these logical explanations, assessment of local control following SBRT continues to carry uncertainties. It will continue to cause difficulties in comparing the efficacy of radiotherapy versus other non-surgical ablative techniques.

Limitations of this evaluation include smaller patient numbers in some tumour subtypes and relatively low number of local progression events which limits LPFS analysis. Patients were excluded if they did not have at least one follow up scan following treatment which may have caused selection bias. The reason for this criteria is local PFS was the primary objective being assessed. This does mean if a patient was referred from a remote centre and does not return for follow-up after treatment, outcomes will not be captured. Furthermore, as with any retrospective studies, the data was subject to information and recall bias. Lack of histopathological confirmation at the time of local control failure was a further limitation. This is an increasingly common dilemma in the metastatic setting where re-biopsy may not be in patient’s best interest due to risks involved.

Our study has highlighted differences in patient selection for RFA or SBRT in the treatment of lung metastases at our institution, accepting the differences in the two cohorts. For example, SBRT was primarily used in the oligometastatic setting while RFA was more commonly used in the polymetastatic setting. With this in mind, we found SBRT achieved better overall PFS with no significant difference in local control or overall survival when compared to RFA. Another significant finding was colorectal patients had better local control with RFA, supporting the outcomes from other studies which have suggested greater radioresistance in colorectal cancer. Higher BED doses in SBRT were associated with better local control – again, a finding which supports those from other studies [31–35]. Future research could focus on optimizing patient selection for the different modalities of treatment; defining and radiation dose schedules for radiosensitive and radioresistant tumour types. These would help to determine the optimum treatment modality for management of lung metastases, and to further individualise patient care.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Local control stratified by primary site and treatment modality; Table S2: Univariable and multivariable Cox-regression analysis.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Jennifer Pang, Daniel Tong and Merina Ahmed; Data curation, Laura Satchwell and Zayn Rajan; Formal analysis, Laura Satchwell and Zayn Rajan; Investigation, Jennifer Pang, Daniel Tong, Nicos Fotiadis, Mohammad Emarah and Helen Taylor; Methodology, Jennifer Pang, Daniel Tong and Merina Ahmed; Resources, Helen Taylor; Supervision, Merina Ahmed; Visualization, Daniel Tong; Writing – original draft, Jennifer Pang and Daniel Tong; Writing – review & editing, Daniel Tong, Nicos Fotiadis, Laura Satchwell, Zayn Rajan, Usman Bashir, Derfel Ap Dafydd, James McCall, David Cunningham and Merina Ahmed.

Acknowledgements/Funding

This independent research is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and the Institute of Cancer Research, London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not available.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

Merina Ahmed reports administrative support and statistical analysis were provided by National Institute for Health Research. Merina Ahmed reports a relationship with AstraZeneca that includes: consulting or advisory. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Pastorino U, Buyse M, Friedel G, Ginsberg RJ, Girard P, Goldstraw P, Johnston M, McCormack P, Pass H, Putnam JB Jr; International Registry of Lung Metastases. Long-Term Results of Lung Metastasectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;113(1):37-49. [CrossRef]

- Treasure T, Farewell V, Macbeth F, Monson K, Williams NR, Brew-Graves C, Lees B, Grigg O, Fallowfield L; PulMiCC Trial Group. Pulmonary Metastasectomy versus Continued Active Monitoring in Colorectal Cancer (PulMiCC): a multicentre randomized clinical trial. Trials. 2019; 20(1):718. [CrossRef]

- Widder J, Klinkenberg TJ, Ubbels JF, Wiegman EM, Groen HJ, Langendijk JA. Pulmonary oligometastases: metastasectomy or stereotactic ablative radiotherapy? Radiother Oncol. 2013;107(3):409-13. [CrossRef]

- Filippi AR, Guerrera F, Badellino S, Ceccarelli M, Castiglione A, Guarneri A, Spadi R, Racca P, Ciccone G, Ricardi U, Ruffini E. Exploratory Analysis on Overall Survival after Either Surgery or Stereotactic Radiotherapy for Lung Oligometastases from Colorectal Cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2016;28(8):505-12. [CrossRef]

- Palma DA, Olson R, Harrow S, Gaede S, Louie AV, Haasbeek C, Mulroy L, Lock M, Rodrigues GB, Yaremko BP, Schellenberg D, Ahmad B, Senthi S, Swaminath A, Kopek N, Liu M, Moore K, Currie S, Schlijper R, Bauman GS, Laba J, Qu XM, Warner A, Senan S. Stereotactic Radiotherapy for the comprehensive treatment of oligometastatic cancers: Long term results of the SABR-COMET phase II Randomised trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(25):2830-2838. [CrossRef]

- Gomez DR, Tang C, Zhang J, Blumenschein GR Jr, Hernandez M, Lee JJ, Ye R, Palma DA, Louie AV, Camidge DR, Doebele RC, Skoulidis F, Gaspar LE, Welsh JW, Gibbons DL, Karam JA, Kavanagh BD, Tsao AS, Sepesi B, Swisher SG, Heymach JV. Local Consolidative Therapy Vs. Maintenance Therapy or Observation for Patients With Oligometastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Long-Term Results of a Multi-Institutional, Phase II, Randomized Study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(18):1558-1565. [CrossRef]

- De Baère T, Aupérin A, Deschamps F, Chevallier P, Gaubert Y, Boige V, Fonck M, Escudier B, Palussiére J. Radiofrequency ablation is a valid treatment option for lung metastases: Experience in 566 patients with 1037 metastases. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(5):987-991. [CrossRef]

- Pennathur A, Abbas G, Qureshi I, Schuchert MJ, Wang Y, Gilbert S, Landreneau RJ, Luketich JD. Radiofrequency Ablation for the Treatment of Pulmonary Metastases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(4):1030-1039. [CrossRef]

- Chua TC, Sarkar A, Saxena A, Glenn D, Zhao J, Morris DL. Long-term outcome of image-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of lung metastases: an open-labeled prospective trial of 148 patients. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(10):2017-2022. [CrossRef]

- Akhan O, Guler E, Akinci D, Ciftci T, Kose IC. Radiofrequency ablation for lung tumors: outcomes, effects on survival, and prognostic factors. Diagnostic Interv Radiol. 2015;22(1):65-71. [CrossRef]

- Fanucchi O, Ambrogi MC, Aprile V, Cioni R, Cappelli C, Melfi F, Massimetti G, Mussi A. Long-term results of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of pulmonary metastases: a single institution experience. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016;23(1):57-64. [CrossRef]

- Gillams A, Khan Z, Osborn P, Lees W. Survival after radiofrequency ablation in 122 patients with inoperable colorectal lung metastases. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36(3):724-730. [CrossRef]

- Okunieff P, Petersen AL, Philip A, Milano MT, Katz AW, Boros L, Schell MC. Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT) for lung metastases. Acta Oncol (Madr). 2006;45(7):808-817. [CrossRef]

- Yoon SM, Choi EK, Lee SW, Yi BY, Ahn SD, Shin SS, Park HJ, Kim SS, Park JH, Song SY, Park CI, Kim JH. Clinical results of stereotactic body frame based fractionated radiation therapy for primary or metastatic thoracic tumors. Acta Oncol (Madr). 2006;45(8):1108-1114. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi W, Yamashita H, Niibe Y, Shiraishi K, Hayakawa K, Nakagawa K. Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for Metastatic Lung Cancer as Oligo-Recurrence: An Analysis of 42 Cases. Pulm Med. 2012;2012:1-5. [CrossRef]

- Rusthoven KE, Kavanagh BD, Burri SH, Chen C, Cardenes H, Chidel MA, Pugh TJ, Kane M, Gaspar LE, Schefter TE. Multi-Institutional Phase I/II Trial of Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Lung Metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(10):1579-1584. [CrossRef]

- Dhakal S, Corbin KS, Milano MT, Philip A, Sahasrabudhe D, Jones C, Constine LS. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for pulmonary metastases from soft-tissue sarcomas: Excellent local lesion control and improved patient survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(2):940-945. [CrossRef]

- Norihisa Y, Nagata Y, Takayama K, Matsuo Y, Sakamoto T, Sakamoto M, Mizowaki T, Yano S, Hiraoka M. Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for Oligometastatic Lung Tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2008;72(2):398-403. [CrossRef]

- Takeda A, Kunieda E, Ohashi T, Aoki Y, Koike N, Takeda T. Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for oligometastatic lung tumors from colorectal cancer and other primary cancers in comparison with primary lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2011;101:255-259. [CrossRef]

- Ricardi U, Filippi AR, Guarneri A, Ragona R, Mantovani C, Giglioli F, Botticella A, Ciammella P, Iftode C, Buffoni L, Ruffini E, Scagliotti GV. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for lung metastases. Lung Cancer. 2011;75:77-81. [CrossRef]

- Tanadini-Lang S, Rieber J, Filippi AR, Fode MM, Streblow J, Adebahr S, Andratschke N, Blanck O, Boda-Heggemann J, Duma M, Eble MJ, Ernst I, Flentje M, Gerum S, Hass P, Henkenberens C, Hildebrandt G, Imhoff D, Kahl H, Klass ND, Krempien R, Lohaus F, Petersen C, Schrade E, Wendt TG, Wittig A, Høyer M, Ricardi U, Sterzing F, Guckenberger M. Nomogram based overall survival prediction in stereotactic body radiotherapy for oligo-metastatic lung disease. Radiother Oncol. 2017;123(2):182-188. [CrossRef]

- Shashank A, Shehata M, Morris DL, Thompson JF. Radiofrequency ablation in metastatic melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109(4):366-369. [CrossRef]

- Tetta C, Carpenzano M, Algargoush ATJ, Algargoosh M, Londero F, Maessen JG, Gelsomino S. Non-surgical Treatments for Lung Metastases in Patients with Soft Tissue Sarcoma: Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT) and Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA). Curr Med Imaging. 2021;17(2):261-275. [CrossRef]

- Lencioni R, Crocetti L, Cioni R, Suh R, Glenn D, Regge D, Helmberger T, Gillams AR, Frilling A, Ambrogi M, Bartolozzi C, Mussi A. Response to radiofrequency ablation of pulmonary tumours: a prospective, intention-to-treat, multicentre clinical trial (the RAPTURE study). Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(7):621-628. [CrossRef]

- Huang K, Senthi S, Palma DA, Spoelstra FO, Warner A, Slotman BJ, Senan S. High-risk CT features for detection of local recurrence after stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2013;109(1):51-57. [CrossRef]

- Clinical Commissioning Policy Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) for patients with metachronous extracranial oligometastatic cancer (all ages) (URN: 1908) [200205P] NHS England. Assessed 1 November 2023. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/1908-cc-policy-sbar-for-metachronous-extracranial-oligometastatic-cancer.pdf.

- Owen D, Olivier KR, Mayo CS, Miller RC, Nelson K, Bauer H, Brown PD, Park SS, Ma DJ, Garces YI. Outcomes of Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT) treatment of multiple synchronous and recurrent lung nodules. Radiat Oncol. 2015;10(1). [CrossRef]

- Milano MT, Philip A, Okunieff P. Analysis of Patients With Oligometastases Undergoing Two or More Curative-Intent Stereotactic Radiotherapy Courses. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73(3):832-837. [CrossRef]

- Soga N, Yamakado K, Gohara H, Takaki H, Hiraki T, Yamada T, Arima K, Takeda K, Kanazawa S, Sugimura Y. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for unresectable pulmonary metastases from renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int. 2009;104(6):790-794. [CrossRef]

- Cao C, Wang D, Tian DH, Wilson-Smith A, Huang J, Rimner A. A systematic review and meta analysis of stereotactic body radiation therapy for colorectal pulmonary metastases. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11(12):5187-5198. [CrossRef]

- Klement RJ. Radiobiological parameters of liver and lung metastases derived from tumor control data of 3719 metastases. Radiother Oncol. 2017;123(2):218-226. [CrossRef]

- Stinauer MA, Kavanagh BD, Schefter TE, Gonzalez R, Flaig T, Lewis K, Robinson W, Chidel M, Glode M, Raben D. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for melanoma and renal cell carcinoma: impact of single fraction equivalent dose on local control. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:34. [CrossRef]

- Das A, Giuliani M, Bezjak A. Radiotherapy for Lung Metastases: Conventional to Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2023;33(2):172-180. [CrossRef]

- Hoerner-Rieber J, Duma M, Blanck O, Hildebrandt G, Wittig A, Lohaus F, Flentje M, Mantel F, Krempien R, Eble MJ, Kahl KH, Boda-Heggemann J, Rieken S, Guckenberger M. Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for pulmonary metastases from renal cell carcinoma-a multicenter analysis of the German working group “Stereotactic Radiotherapy”. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(11):4512-4522. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi N, Abe T, Noda SE, Kumazaki YU, Hirai R, Igari M, Aoshika T, Saito S, Ryuno Y, Kato S. Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for Pulmonary Oligometastasis from Colorectal Cancer. In Vivo. 2020;34(5):2991-2996. [CrossRef]

- Lee TH, Kang HC, Chie EK, Kim HJ, Wu HG, Lee JH, Kim KS. Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Pulmonary Metastasis from Colorectal Adenocarcinoma: Biologically Effective Dose 150 Gy is Preferred for Tumour Control. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2023;35(6):e384-e394. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).