1. Introduction

Access to and the sustainable management of food, water, and energy are integral components of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, forming the foundation of three key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

1]. Different crops can be agriculture directly on the land in the open atmosphere, but many products require to use the of greenhouses to provide the best environments and circumstances that are considered ideal for product agriculture. Greenhouses are engineered structures designed to regulate key factors affecting crop growth such as solar radiation, temperature, relative humidity, light intensity, and carbon dioxide levels thereby enhancing agricultural productivity year-round [

2].

Over 40% of the Earth’s land surface consists of arid and semi-arid regions, which are home to more than one-third of the global population [

3], the majority of whom rely on agriculture to meet their basic needs. In these regions, factors such as air temperature and humidity play a critical role in agricultural productivity [

4]. In arid and semi-arid climates, increased irrigation during the summer months often results in elevated humidity levels inside greenhouses, which can have adverse effects on crop production. High air humidity can significantly reduce crop yields, as seen with cucumber production, where excessive humidity stress has been shown to substantially decrease yield [

5]. Furthermore, elevated humidity levels inside greenhouses can lead to poor crop growth, increased susceptibility to bacterial spread, and, in severe cases, crop destruction.

In arid environments, optimal plant growth and productivity require different moisture levels compared to tropical climates [

6]. The climatic conditions in arid and semi-arid regions pose significant challenges to cultivation and irrigation, with agriculture and the provision of adequate water often considered critical concerns. Researchers have consistently sought innovative technologies to address these issues. For instance, a study evaluated an atmospheric water harvesting system under diverse climatic conditions, focusing on its application in arid regions [

7]. Another initiative introduced Smart Farm technology for urban agriculture, aiming to reduce carbon footprints and dependence on conventional freshwater supplies [

8].

Humidity control becomes imperative in terms of attaining optimum crop yield and avoiding greenhouse diseases, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions with very severe climatic challenges. Free humidity stimulates fungal diseases, reduces nutrient transfer, and will also cause physiological disorders like hyperhydricity [

9,

10,

11]. High humidity promotes leaf condensation, increasing disease such as botrytis risk and inhibiting vital nutrient transfer, while low humidity causes dehydration and growth inhibition [

12,

13]. Maintaining the relative humidity between 60-80% is ideal for most crops, supporting transpiration, photosynthesis, and overall plant health [

14,

15].

Vegetables like cucumbers and tomatoes are most vulnerable to humidity fluctuations. Humidity significantly affects leaf photosynthesis, crop yield, and fruit quality [

5,

16,

17]. It has been established that increased ventilation in greenhouses can reduce disease severity in cucumber by up to 70% [

18]. High humidity exerts the same impact on initiating fungal diseases in vegetables like tomato leaf mold, hence the need for proper management to be employed [

19].

Nighttime conditions tend to exacerbate humidity problems due to lowered temperatures and elevated relative humidity, which induce condensation and increased risk of disease [

15,

20]. Adequate management of humidity is required for there to be sustainable greenhouse agriculture, particularly in dry regions where interactions of temperature and humidity greatly impact crop yield [

13,

15]. Sustainable practices in Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) provide optimum conditions for growing and exclude climate issues, leading to higher quality crops and yields [

9,

21].

2. Techniques and Approaches for Humidity Control in Greenhouses

Humidity control is required effectively to optimize greenhouse conditions for crop growth and production. Studies have established various means and technologies of humidity control in greenhouses. The integration of traditional and new techniques is required to control humidity according to climatic factors, crop requirements, and greenhouse types.

2.1. Ventilation Systems

Ventilation is also the most frequent way of humidity control in greenhouses. Natural ventilation, achieved by the location of vents, allows for air exchange, removing excess moisture. Mechanical ventilation systems, using fans and ducts, provide more accurate and controlled humidity regulations. For instance, studies have shown that the inclusion of additional ventilation holes in greenhouses can decrease the severity of disease in cucumber plants by up to 70% [

18]. Besides, the use of natural ventilation, evaporative cooling, and shading has proven to contain greenhouse power consumption while maximizing indoor conditions for productivity by plants in warm climatic conditions [

22,

23].

2.2. Dehumidification Technologies

Dehumidification techniques are the core of managing greenhouse humidity, ensuring optimal conditions for plant growth, minimizing the occurrence of disease, and optimizing overall productivity. Techniques range from traditional approaches to emerging technologies, each individually tailored to address specific environmental issues and operational needs. Traditional methods (ventilation of warm humid air and heating) are energy wasteful. Thus, active dehumidification systems such as vapor-compression (heat pump) dehumidifiers and desiccant-based dehumidifiers have been researched to control the greenhouse humidity more precisely.

Vapor-compression dehumidifiers (typically implemented as heat pump dehumidifiers) use a refrigeration cycle to condense water from air. These are typically fitted with an evaporator coil (for cooling air below dew point, removing water) and a condenser coil (for reheating the dehumidified air). This closed-cycle dehumidification can reduce humidity autonomously year-round, unlike ventilation which is dependent on external conditions.

Heat pump dehumidifiers have succeeded in reducing greenhouse relative humidity by a significant amount, as backed up by experimental results where it was decreased from around 89% to 51% RH when distributed units were employed [

24]. They also provide optimum vapor pressure deficit levels, typically 0.2 to 0.7 kPa brought on by the drier microclimate that encourages healthy plant growth and reduces foliar moisture [

25]. Their use has effectively eliminated condensation on crops in mild climates. In addition, the reduction in humidity has been shown to inhibit fungal diseases; in one trial, there were no fungal infections and fungicide use was greatly reduced, with the dehumidifier consuming as little as 4 W/m² [

26]. Improved microclimate conditions have also meant higher yields, with a Canadian study reporting a 2% reduction in crop loss and revenue gain of approximately

$3,000, reflecting the dual benefits of disease prevention and economic gain from improved climate control [

27]. However, those systems are energy consumers, predicated on the continuous supply of electricity to run compressors and fans, which may boost operating expenses and compromise viability where energy costs are high or power infrastructure is limited [

26,

28].

Desiccant dehumidification of greenhouses has been promising, especially in warm and humid climates and water-limited regions [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Solar-heated liquid desiccant systems have successfully lowered humidity and temperature and enabled crop production where otherwise highly limited [

33]. Solid desiccant wheels were also successful in ensuring low humidity in wet seasons [

33]. Solid desiccant systems, particularly rotary beds, account for about 66% of desiccant systems used in air conditioning [

34]. However, they require high regeneration temperatures (typically above 90 °C) and rely on low heat capacity air for regeneration. In contrast, liquid desiccant systems offer greater flexibility in design and installation. Unlike solid systems, they allow off-site and asynchronous regeneration, and the desiccant solution can be externally cooled or heated, improving energy efficiency [35; 36]. Additionally, liquid desiccant systems operate at lower regeneration temperatures and can reduce operating costs by up to 40% compared to solid systems [

37].

Desiccant systems function best in the context of an integrated climate control strategy (using evaporative cooling or auxiliary refrigeration) [

26,

29]. They are advantageous because of lower energy costs if renewable heat is utilized and potential water recycling, though the percentage of humidity load they can handle may be limited by regeneration capability. In general, desiccant-based dehumidification is a more environmentally friendly option than sole compressor-based cooling in greenhouses, with clear benefits in some environments.

3. Methodology

In order to assess the effectiveness of humidity control systems, an overall model was utilized to quantify moisture removal from air rate in a Jordanian Dhiban greenhouse.

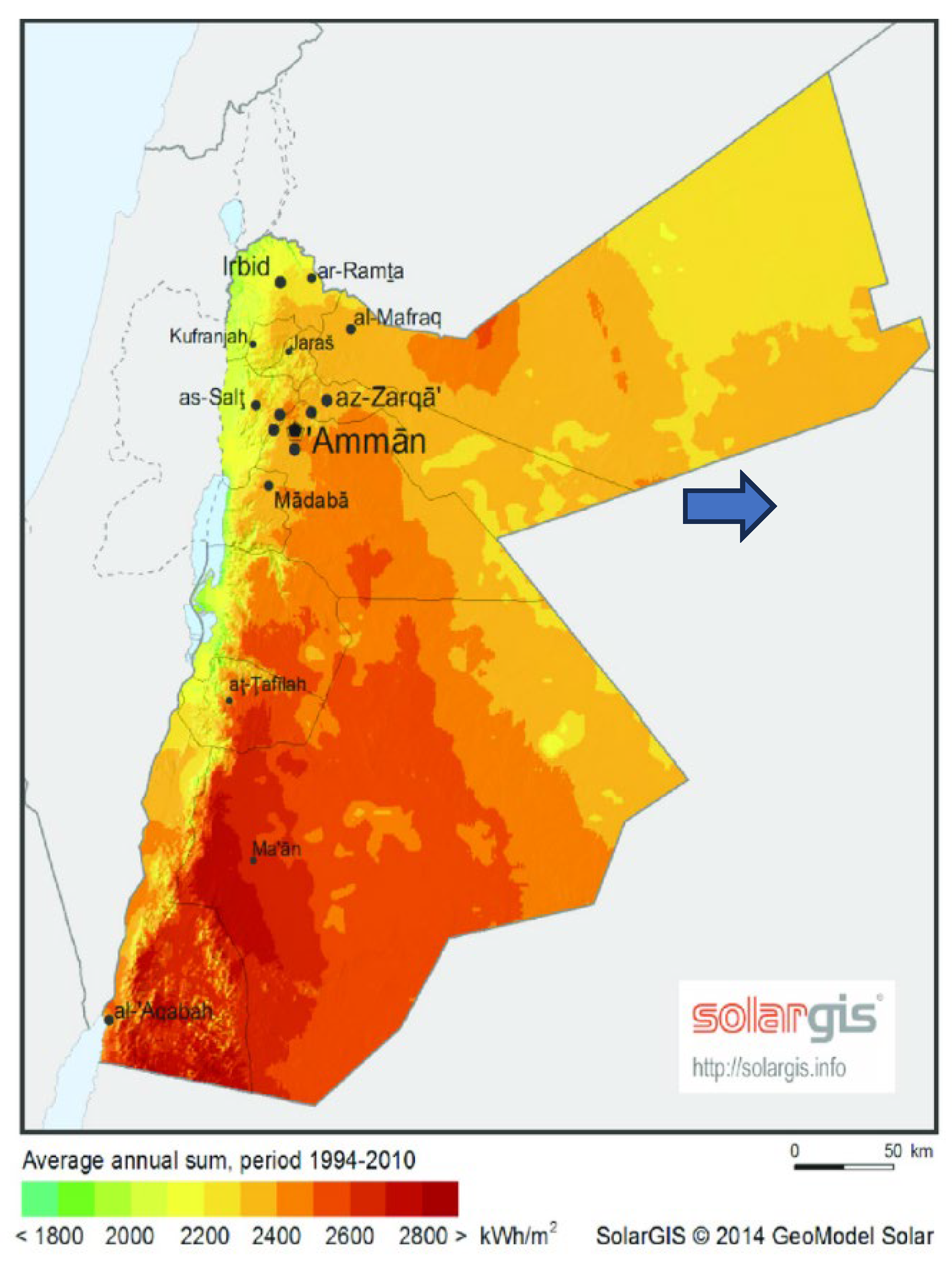

Figure 1 presents a solar radiation map of Jordan, illustrating the spatial distribution of the average annual solar irradiation [

38]. The map also highlights the location of the investigated greenhouse in the Dhiban area, marked by a blue arrow. Dhiban is situated in the Madaba Governorate, southwest of Amman.

The greenhouse itself serves as a testbed for investigating humidity control in the context of semi-arid climate conditions. The methodology involves combining experimental data acquisition, system performance analysis, and modeling techniques to investigate the effectiveness of customized dehumidification strategies tailored to the local environment’s unique regional challenges.

3.1. Greenhouse Equipment and Measurement Techniques

Agriculture within Jordan, either under open skies or in covered arrangements like greenhouses, is faced with numerous issues, the majority of which are increased by climate change. Globally, elsewhere, temperature increase and altered weather pattern have disrupted agricultural activity, and Jordan is no exception. There have been more frequent occurrences of worse weather, like more heatwaves and less rainfall, on top of impacting already scarce water resources [

39,

40,

41]. This summer has been particularly brutal, with record-breaking temperatures further testing greenhouse operations in Dhiban, Jordan. The combination of high temperatures and elevated humidity levels in Dhiban has created conditions that challenge traditional greenhouse management practices. The notable decline in cucumber yields during peak summer months highlights the urgent need for innovative approaches to address these climatic challenges and enhance crop resilience.

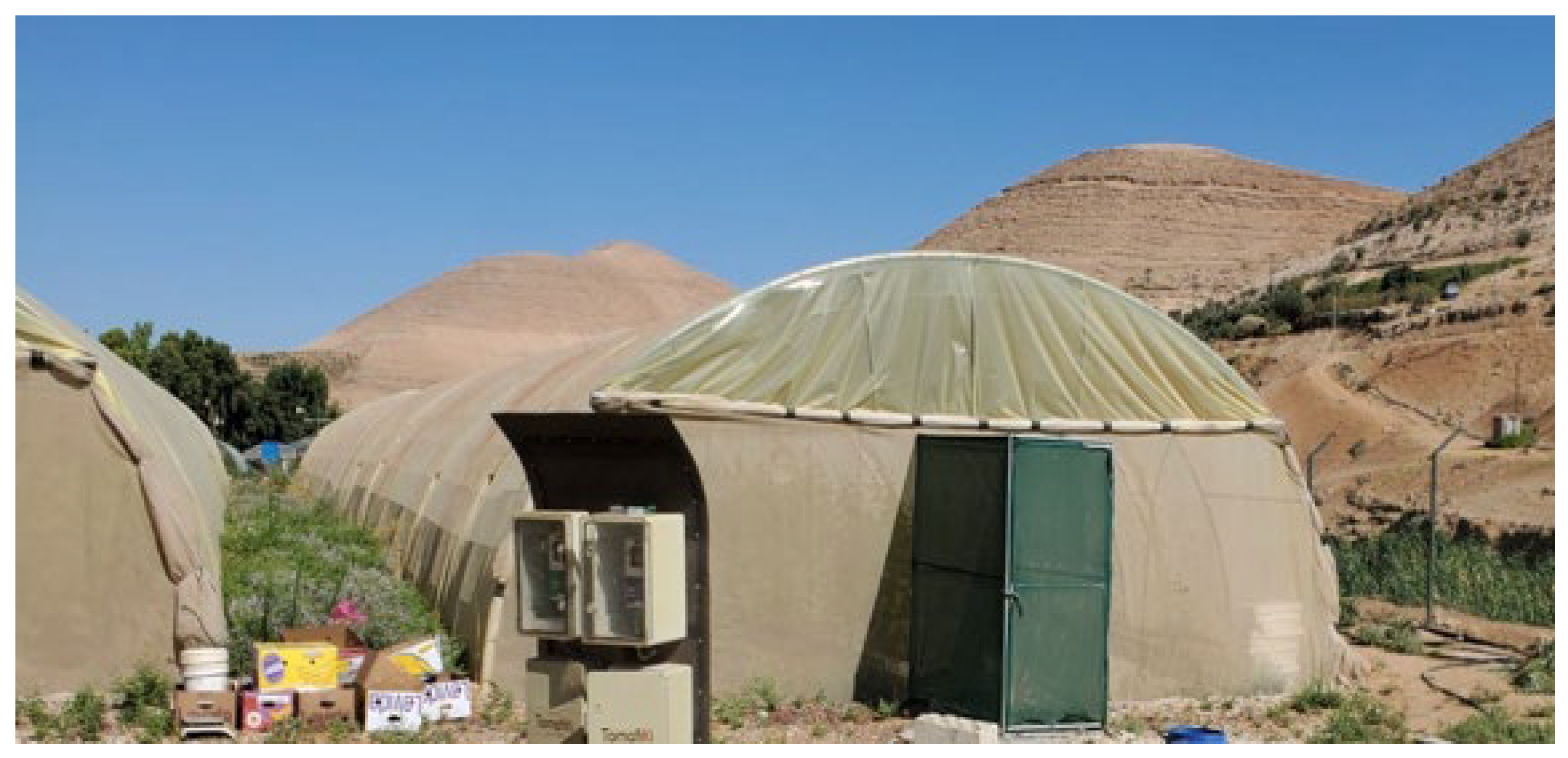

Dhiban greenhouses in Jordan’s Madaba Governorate have been built to achieve maximum cucumber yields despite the unfavorable climatic conditions. One of the greenhouses is 9 by 50 meters, providing a controlled environment significant for successful crop growth within arid and semi-arid environments. The combined area covered in cucumber farming by four of these greenhouses is 1,800 square meters.

Figure 2 illustrates a sample of greenhouses used in this study.

Dhiban’s climate is characterized by arid conditions, with hot summers and relatively mild winters. The average annual temperature ranges from 15°C to 30°C, with summer temperatures often exceeding 35°C. These climatic conditions present significant challenges for greenhouse agriculture, especially during the summer months when high temperatures and humidity levels can negatively impact crop health and yield. The summer of 2024 was particularly severe, with extreme heat intensifying the difficulties faced by local farmers and necessitating innovative solutions for sustainable agricultural practices. The observations from the cultivation period of June to August 2024 reveal challenges related to high humidity, which adversely affected the health and yield of cucumber crops. The captured photos, shown in

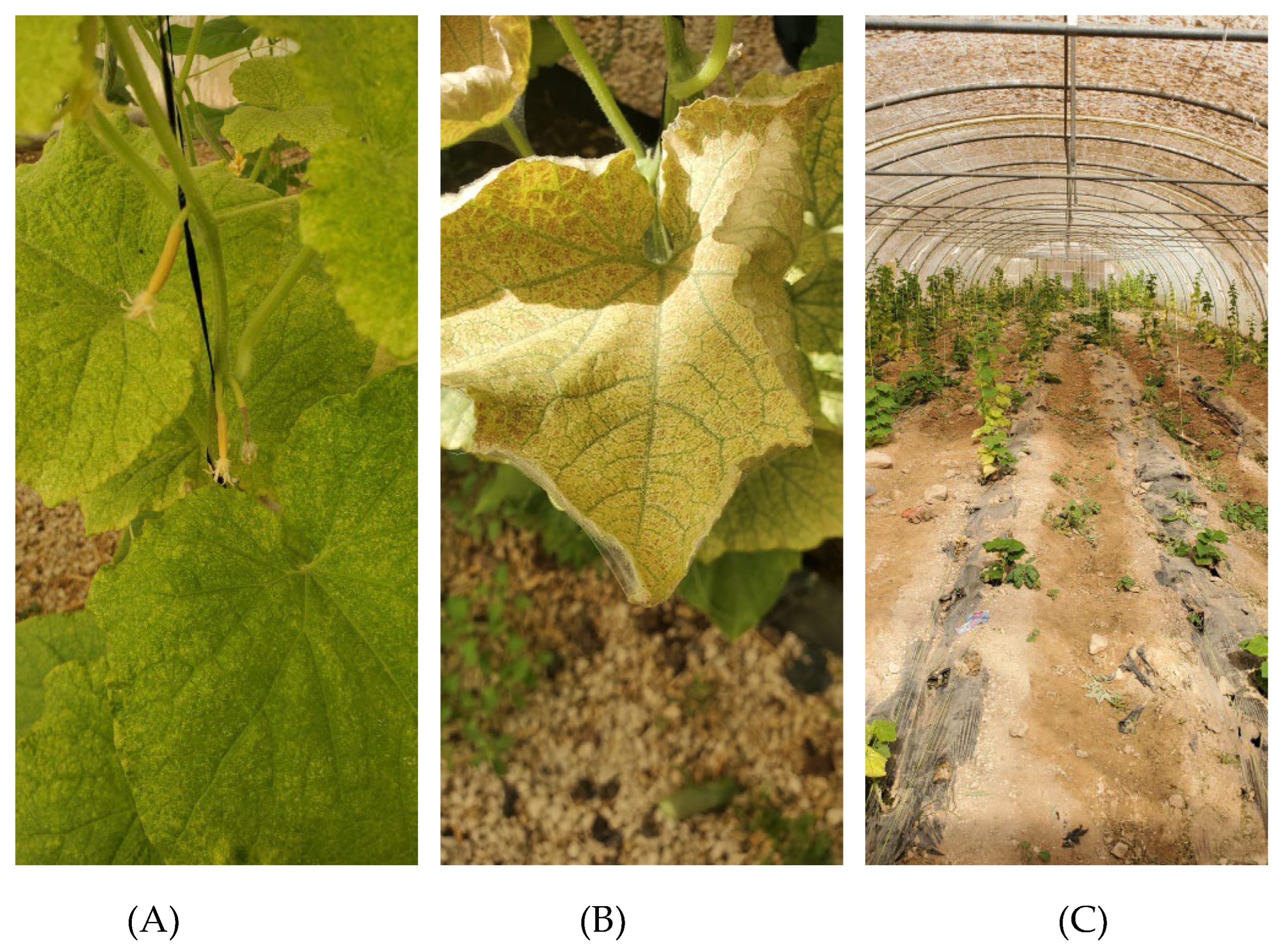

Figure 3, provide visual evidence of these challenges, highlighting key issues encountered during this period.

The observations during the June to August 2024 show the imperative need for better humidity management within the Dhiban greenhouse. In Image A, cucumber young fruits are drying. It is because of the high humidity stress that results in interference with pollination activities. Excess moisture within the greenhouse environment can inhibit pollen transfer, leading to abortion of fruit. Moreover, these conditions predispose the plants to fungal pathogens, which infect flowers and young fruit so that they abort prematurely. Yellowing of leaves (chlorosis) is seen in some areas of the greenhouse in Image B. Chlorosis is an indication of physiological stress, which can be caused by nutrient deficiencies exacerbated by reduced transpiration rates in the humid environment. Apart from it, high humidity favors the infection of fungal disease such as downy mildew, which besides damaging the leaf also reduces plant photosynthesis capabilities. All such impacts collectively divert plant growth and drastically cut crop yields. Because of increased heat in greenhouses due to high temperature, the farmers made use of the clay coating technique on the plastic cover to meet the challenge from excess heat. The greenhouse is covered with plastic that is clay-coated, and it has the effect of diffusing incoming light. It reduces direct solar radiation and lowers the inner temperature, thus creating an optimal condition for plants to grow. It also reduces light intensity slightly, an effect that could impact photosynthesis if not regulated.

Table 1 illustrates the total cucumber cultivation yield for two distinct periods in 2024, February to April and June to August, highlighting the impact of relative humidity on crop productivity.

During the first cultivating period (February to April), the relative humidity was 50-55% and perfect conditions for cucumber crops to develop. The result at this time had a stupendously high yield of 11,750 kg, with this suggesting improved environmental conditions in terms of pollinating and growing. In a reverse incidence of the second cultivating period from June to August, the relative humidity rose horribly to 70-80% in relation to the horribly high summer temperatures. This elevated humidity adversely affected the health of the plants via outbreaks of diseases, ineffective pollination, and hindrance in the growth of fruit. Consequently, the production declined to as little as 500 kg, accentuating the detrimental effects of elevated humidity on green house cucumber cultivation.

This contrast turns out to be a clear illustration of how humidity control is essential in aiding greenhouse productivity, particularly in warm summer weather conditions over regions such as Dhiban, Madaba. This underlines the necessity of performing effective mitigation measures, including ventilation, dehumidifying, and enhanced irrigation, for sustaining crop yield under challenging climatic conditions. The greenhouse complex was utilized to grow cucumber crops to test humidity and temperature management efficiency. For the optimization of the greenhouse conditions, monitoring of humidity and temperature is essential. Digital hygrometers and PT100 sensors were installed at three points in the greenhouse to monitor the relative humidity and dry bulb temperature in real time with an accuracy of ±2% and ±0.7 K for the relative humidity and temperature measurements, respectively. The data were logged using a data logger at 30-minute intervals. The period of growing cucumbers was from 10 June to 25 August 2024, and seed planting began on 19 April 2024.

3.2. Model Description

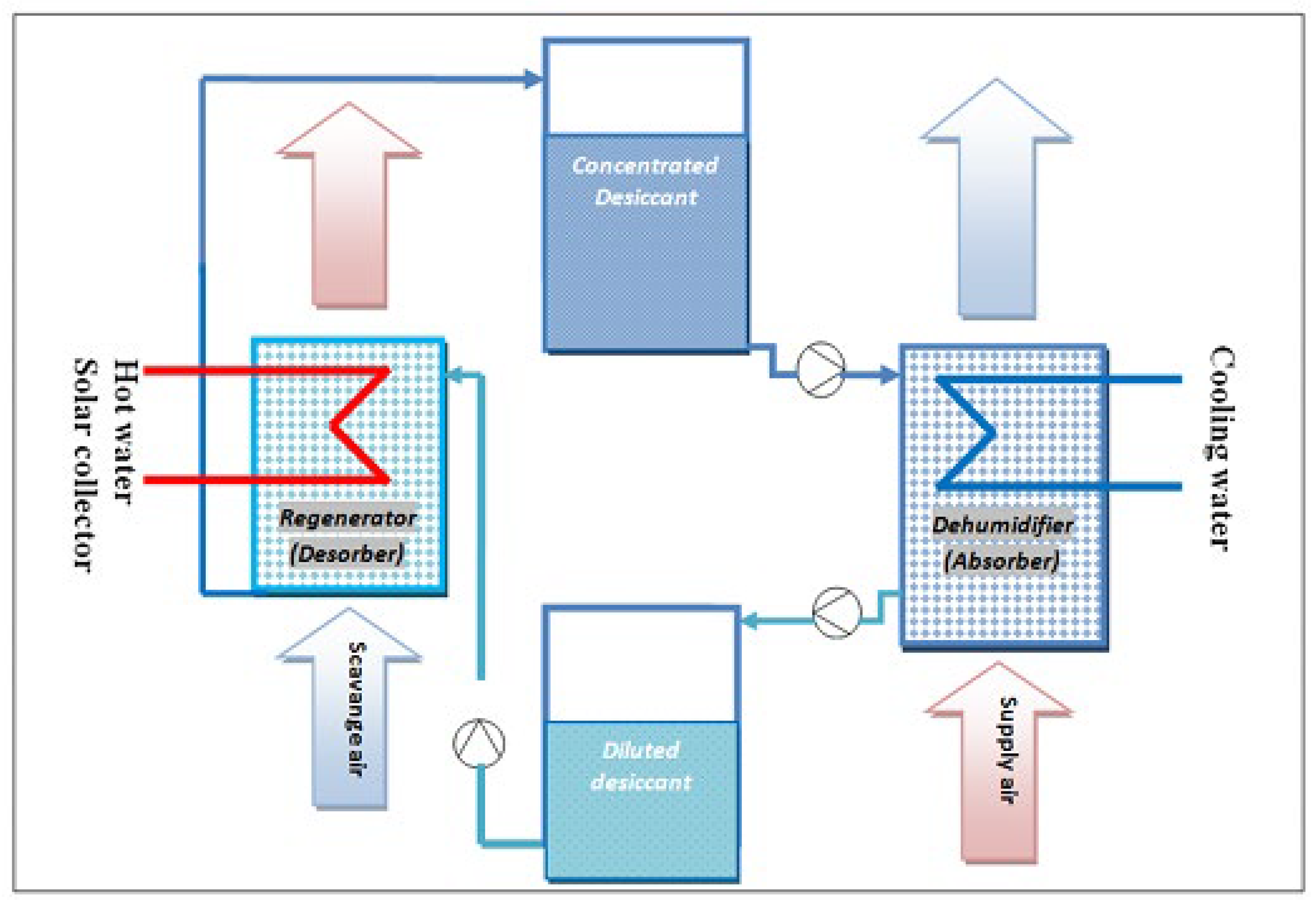

Figure 4 presents a schematic of the open-cycle liquid desiccant system studied. This system operates at atmospheric pressure and uses a concentrated hygroscopic solution as an adsorbent to extract water vapor from the air, which is then supplied to the greenhouse.

The diluted, heated solution is regenerated using a solar thermal evacuated tube system and subsequently pumped to the regenerator. In the regenerator, a secondary air stream removes the absorbed water vapor, which is condensed into liquid water for irrigation in a condenser.

The absorber modeled in this study operates under adiabatic conditions and is externally cooled using CELdek-type structured packing material. In this setup, a concentrated desiccant solution is continuously sprayed over the packed tower, while a stream of moist air passes through the packing material, enabling heat and mass exchange. Calcium chloride was selected as the desiccant material for this study due to its high hygroscopicity, cost-effectiveness, and ease of availability. A desiccant solution with a concentration of 48% by weight was used. To facilitate air circulation, the moist air inside the greenhouse was directed through a duct system equipped with a fan operating at a mass flow rate of 2 kg/s (equivalent to 7200 kg/h). This air was then introduced into the absorber unit, which contained the CaCl

2 solution and structured packing material to enhance mass transfer. As the air passed through the absorber, it underwent dehumidification by transferring moisture to the desiccant. The treated air, now at an acceptable humidity level, was subsequently recirculated into the greenhouse to maintain optimal environmental conditions for crop growth. The modeling approach is grounded in mass and energy balance equations applied to differential elements within the packing-filled chamber. This work builds upon the foundational model proposed by [

42] and incorporates further developments. The mathematical description of the cross-flow heat and mass exchanger is detailed in Jaradat et al. (2022b). The ε-NTU relationship for the cross-flow configuration, assuming an infinite number of CELdek packing rows, is defined by Equation (1) [

42,

43].

The number of transfer units (NTU) is determined based on the mass transfer coefficient (β), the specific surface area of the packing material (Av), and the total volume of the packing (VT), as defined by Equation (2).

The mass and heat transfer coefficients (β and α, respectively) are connected in relation to the Lewis number (Le) as given in Equation 3.

The model considers pure desiccant solutions, with their thermophysical properties including vapor pressure, density, viscosity, thermal capacity, and differential enthalpy of dilution taken from the data provided by [

44].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. System Performance in Controlling Air Humidity

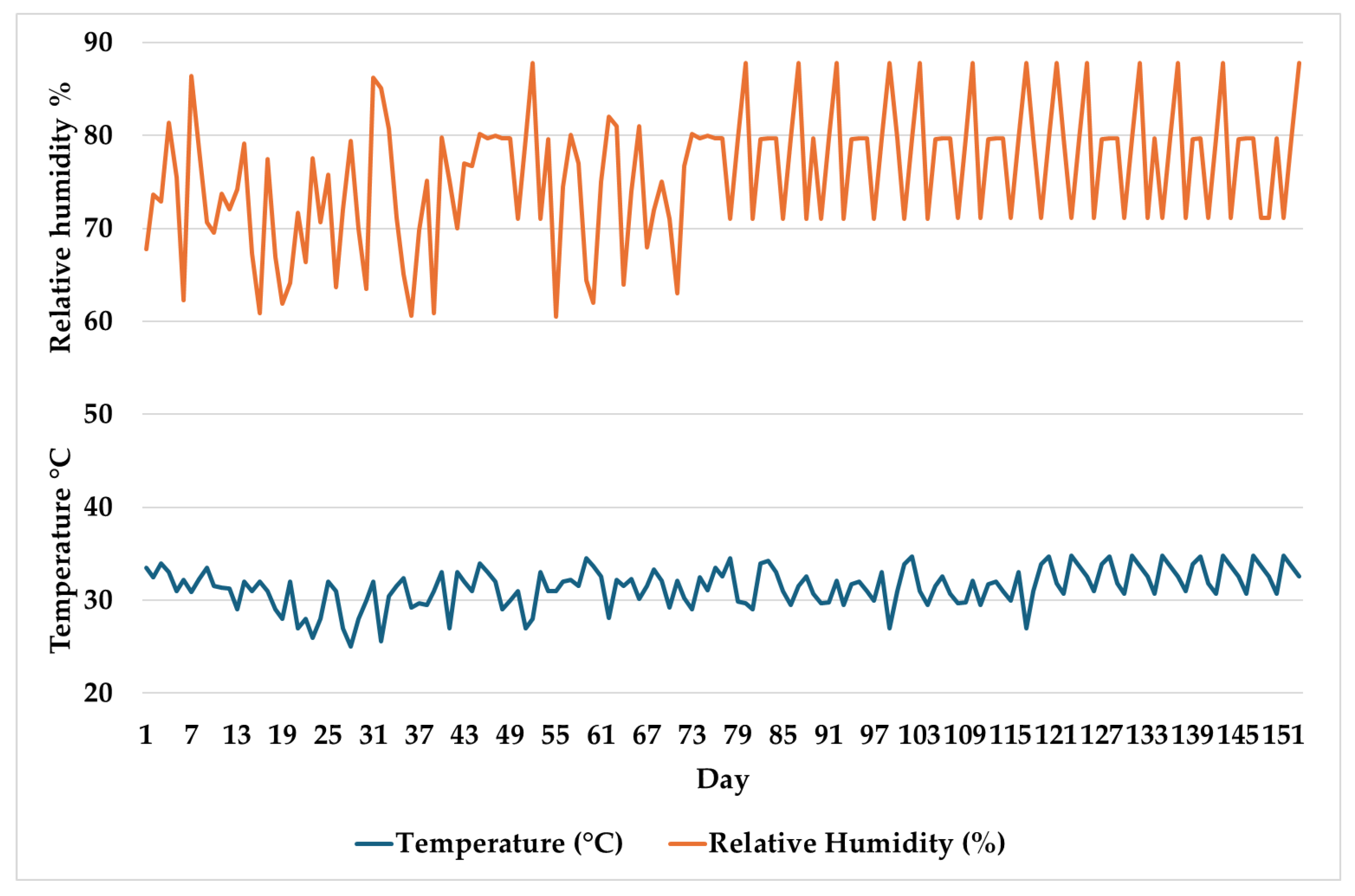

The numerical model has been designed and run with aiming in reducing air relative humidity to the comfortable circumstances of cucumber crops. The inlet air-relative humidity and dry pulp temperature are shown in

Figure 5. The figure depicts air relative humidity and temperature behavior during the cultivation period.

The data were collected continuously using digital sensors positioned at representative locations inside the greenhouse. The temperature values fluctuate between approximately 23°C and 36°C, showing the typical daily and seasonal variations characteristic of the semi-arid climate of Dhiban. On the other hand, the relative humidity consistently exhibits high values, frequently exceeding 70% and often peaking close to 90%, particularly during the early and late stages of the cultivation period. The figure highlights the critical challenge faced during the summer season, where elevated temperatures are coupled with persistent high relative humidity, creating unfavorable conditions for cucumber cultivation. These conditions, if left uncontrolled, could lead to significant reductions in crop yield due to heat stress and the increased risk of disease outbreaks. This dataset serves as the baseline for evaluating the performance of the implemented dehumidification system.

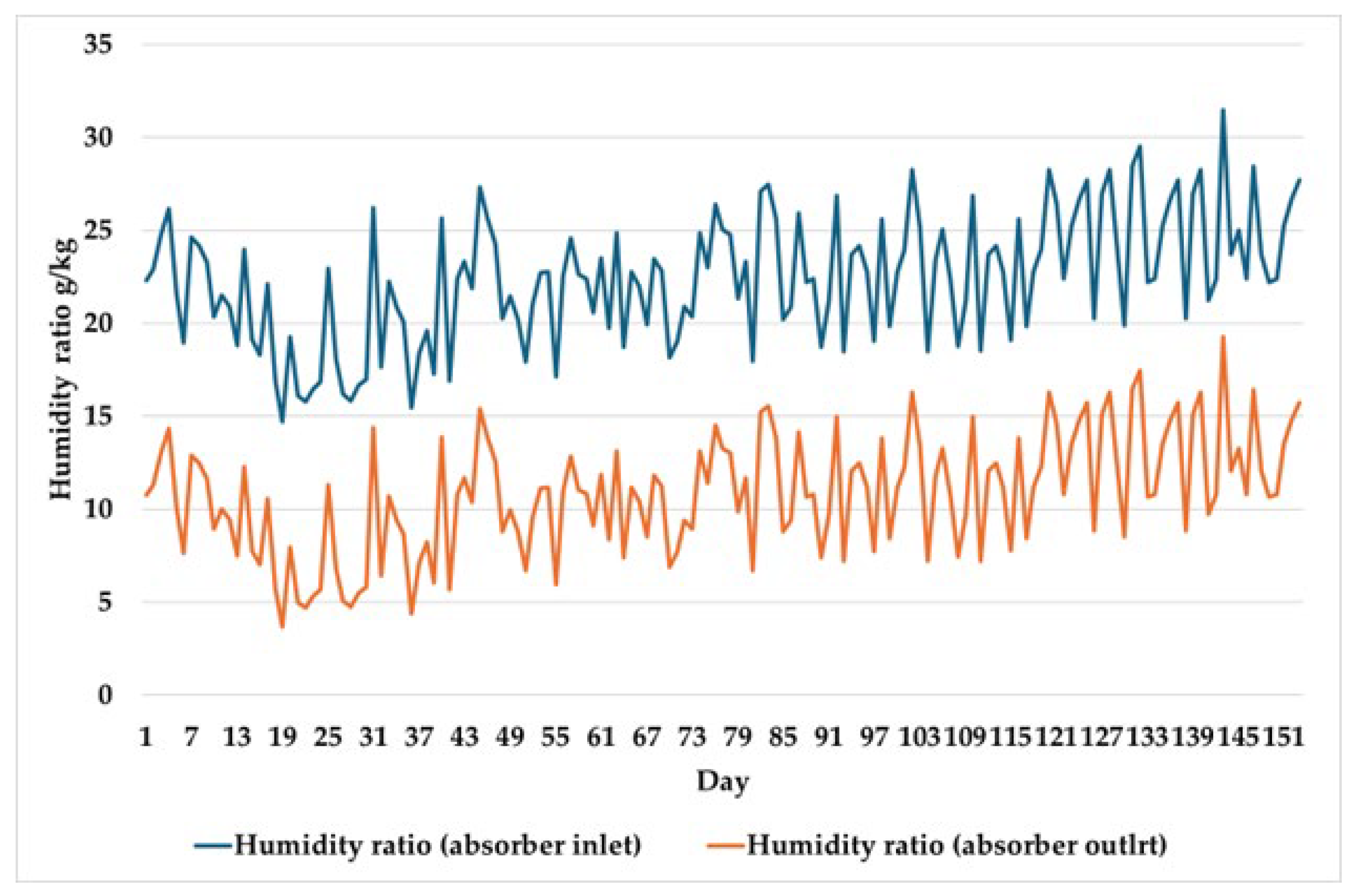

Figure 6 illustrates the daily variation of the air humidity ratio (in g/kg) at the inlet and outlet of the liquid desiccant dehumidifier during the cucumber cultivation period.

The inlet humidity ratio fluctuated between approximately 17 g/kg and 28 g/kg, reflecting the combined effect of high irrigation demand and plant transpiration under the semi-arid summer conditions of Dhiban. After the dehumidification process using a 48% CaCl2 solution, the outlet humidity ratio was consistently reduced, ranging between 8 g/kg and 18 g/kg. This significant reduction in moisture content demonstrates the system’s ability to effectively lower the humidity ratio by up to 10 g/kg, improving the internal greenhouse climate. Maintaining lower humidity levels is critical for cucumber production, as it helps mitigate the risk of fungal diseases, improves nutrient transport, and enhances stomatal function. By preventing excessive humidity buildup, especially during the night, the system contributes to better crop health and productivity. The observed pattern confirms the model’s effectiveness and aligns with previous findings showing that controlling the humidity ratio within optimal limits directly supports higher yields and reduced crop losses in greenhouse cucumber cultivation.

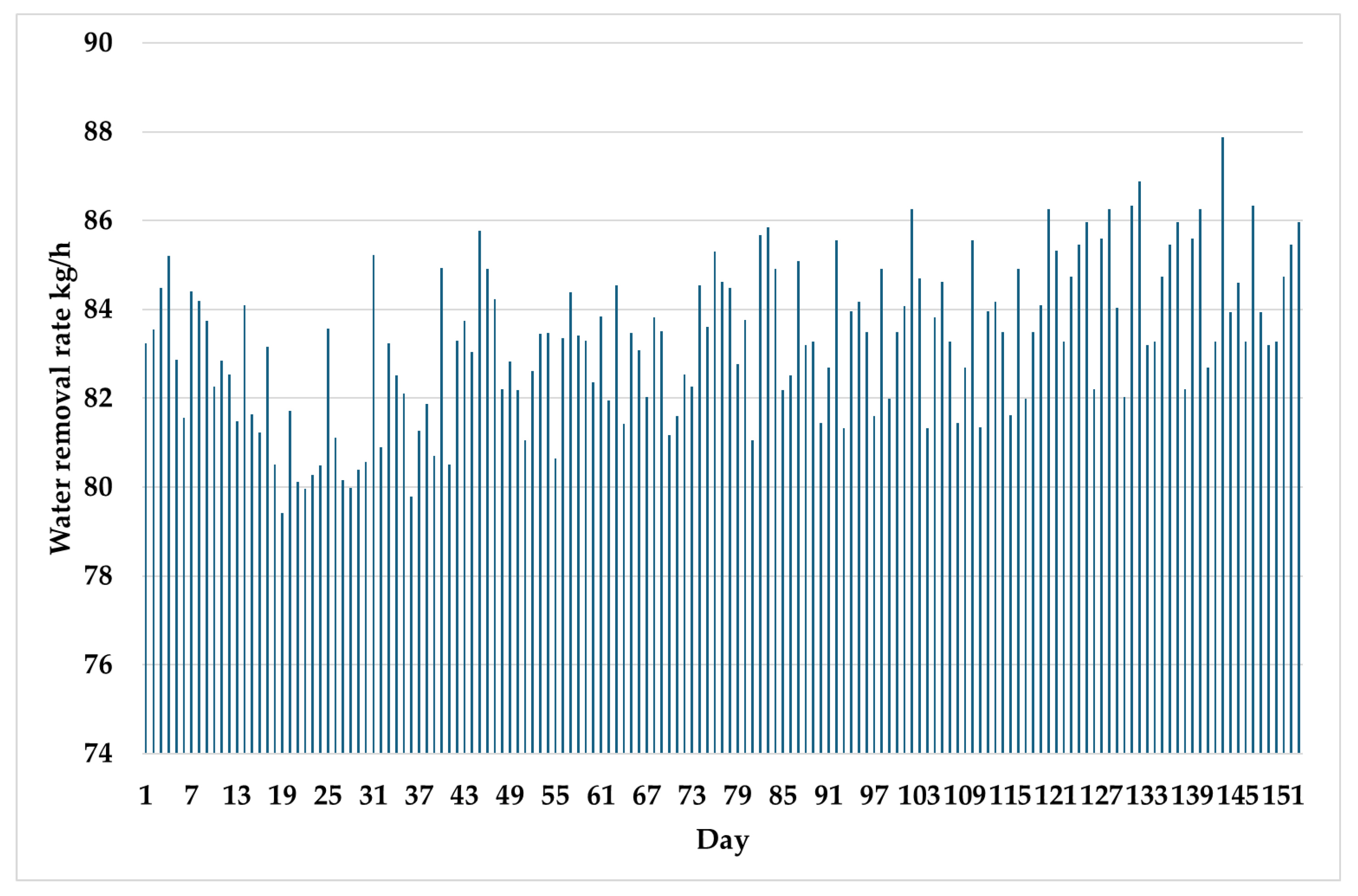

Figure 7 shows the daily variation of the water removal rate (kg/h) achieved by the liquid desiccant dehumidification system during the cucumber cultivation period. The water removal rate was calculated by multiplying the dry air mass flow rate by the difference between the inlet and outlet humidity ratios, reflecting the actual amount of moisture extracted from the greenhouse air.

The results reveal that the system maintained a stable water removal capacity throughout the cultivation cycle, with values generally ranging between 78 kg/h and 86 kg/h. Variations in removal rates are attributed to changes in external weather conditions, plant transpiration rates, and internal greenhouse climate dynamics. The gradual increase in water removal towards the latter part of the period is associated with higher ambient humidity and crop maturity, leading to intensified transpiration. This sustained and effective moisture removal ensured that relative humidity levels inside the greenhouse were kept within desirable limits, contributing to improved cucumber health and yield. The figure highlights the system’s reliability and responsiveness in maintaining greenhouse air conditions under semi-arid climatic stress.

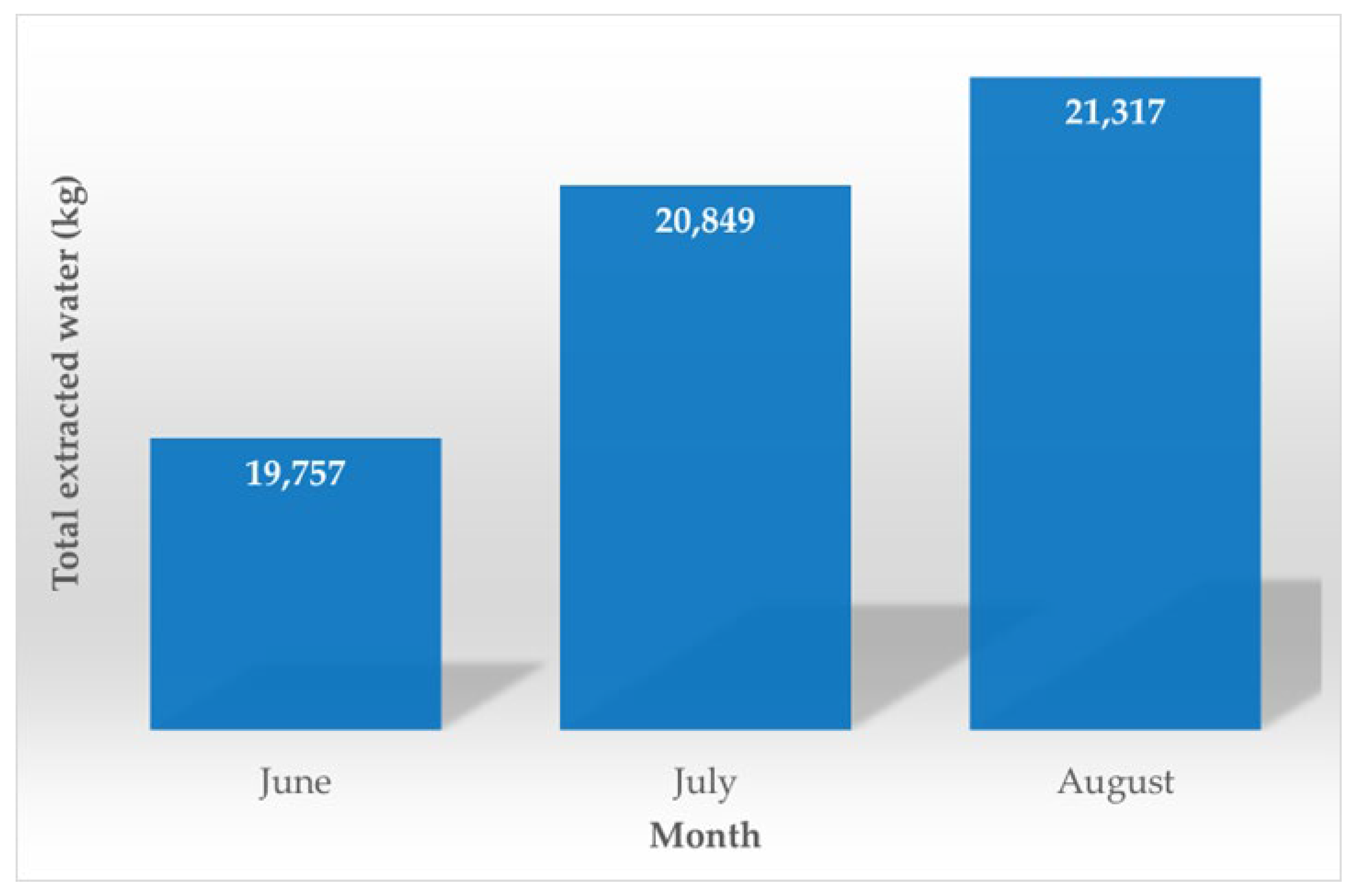

Figure 8 illustrates the total amount of water extracted by the liquid desiccant dehumidification system on a monthly basis during the cucumber cultivation period, considering an average operation of 8 hours per day.

The results show a steady increase in the total recovered water over the summer season. In June, the system extracted approximately 19,757 kg of water, which increased to 20,849 kg in July and reached 21,317 kg in August. This trend can be attributed to the progressive rise in ambient temperature and plant transpiration as the summer season advanced and the cucumber crops matured, leading to higher moisture release into the greenhouse environment. The ability of the dehumidification system to consistently capture and recover this moisture is crucial for managing indoor humidity levels while simultaneously providing a valuable source of water that can be reused for irrigation. The data confirm the system’s effective performance under varying summer conditions, highlighting its potential to contribute to water savings and improved crop management in semi-arid greenhouse applications.

4.2. Discussion and Comparison with Related Studies

The results show that the CaCl

2 dehumidification system maintained the greenhouse air within acceptable temperature and humidity ranges. Daytime temperatures rose as expected under semi-arid conditions, while relative humidity (RH) was generally kept below the critical 70% threshold. This is important because excessive humidity (>70% RH) in greenhouses is known to foster fungal diseases and even nutrient uptake issues in cucumber plants [

45]. By operating the liquid-desiccant dehumidifier during periods of high moisture (e.g., nighttime and early morning), the system prevented RH from staying elevated overnight. The result was a more stable humidity profile that stayed largely within the optimal range for cucumbers (approximately 60–70% RH) [

45]. This aligns with best-practice recommendations for cucumber cultivation, as prolonged RH above 70% can quickly increase disease pressure and reduce crop performance. The efficacy of the dehumidifier is evident in

Figure 6, which plots the humidity ratio of the air before and after passing through the desiccant unit. The humidity ratio downstream of the absorber is markedly lower than the inlet air, demonstrating active moisture removal from the greenhouse air. On average, the system achieved a substantial drop in absolute humidity (g moisture per kg dry air), especially during peak transpiration hours when the plants release the most water vapor. This drying effect reflects the high affinity of concentrated CaCl

2 for water vapor, and it allowed the greenhouse to maintain a drier environment than would be possible with ventilation alone (which in a semi-arid region can still be insufficient at night when outside air cools and RH rises). The design and analysis were aided by an ε-NTU modeling approach for the absorber, which provided predictions of the dehumidifier’s effectiveness. Using the effectiveness-NTU method, the heat and mass transfer performance of the packed-bed absorber could be estimated and optimized [

46].

In practice, the observed moisture removal rates and outlet air conditions corresponded well with the model’s predictions, indicating that the ε-NTU approach accurately captured the coupled heat–mass exchange in the CaCl2 absorber. This modeling framework was crucial in sizing the dehumidifier to handle the cucumber crop’s transpiration load and in anticipating the system’s performance under varying greenhouse conditions. Figure 7 presents the water removal rate (kg/h) achieved by the dehumidification system over the cultivation period. The moisture removal rate tracks the growth stages of the crop and diurnal climate patterns. Early in the growing period, when the plant canopy was small, water removal rates were modest. As the cucumber crop reached full canopy and transpiration increased, the dehumidifier consistently extracted higher amounts of water vapor, often peaking during the late morning and evening periods when humidity tended to accumulate. These peaks in Figure 7 indicate the system’s responsiveness to plant water release as the cucumbers transpired more, the CaCl2 solution absorbed more moisture, helping to rapidly bring down the greenhouse humidity. Toward the end of the season, as plants were mature or being cleared, the water removal tapered off. Overall, the system showed an ability to remove on the order of several kilograms of water per hour during peak conditions, which is comparable to the moisture generation rate by the crop. This confirms the dehumidifier’s capacity was well-matched to the greenhouse load.

The performance observed in Dhiban, Jordan is consistent with findings from other controlled environment studies using liquid desiccants in semi-arid or Mediterranean climates. For example, the study [

47] demonstrated that a CaCl

2-based hybrid dehumidification system could effectively regulate humidity in a Mediterranean greenhouse (Greece), resulting in improved plant evapotranspiration and microclimate conditions. Their semi-arid greenhouse trials with cucumbers showed that using CaCl

2 to absorb moisture kept the humidity at optimal levels for transpiration, thereby enhancing the plants’ ability to cool themselves and uptake nutrients. This mirrors our result that maintaining lower humidity via desiccant dehumidification avoids the stifling of transpiration that occurs when air is saturated. In both cases (the Greek study and the present work), the desiccant system created a drier and more uniform climate, especially during critical periods of high humidity, without the large energy penalty of traditional ventilation.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the performance of a CaCl2-driven open-cycle liquid desiccant dehumidification system for climate control and water recovery in a Jordan-based semi-arid area Dhiban greenhouse. Using an effectiveness-based (ε–NTU) modeling approach, the system was modeled under actual climatic and operation conditions for a June-August 2024 period of cucumber growing. The results indicated a substantial reduction in relative humidity (RH) and absolute humidity content inside the greenhouse. The system maintained the RH under 60% during the operating period, significantly reducing the risk of fungal diseases and stress physiological disorders caused by excessive humidity. The air humidity ratio was also reduced by as much as 8.6 g/kg on average after traveling through the absorber unit, with the highest reductions of up to 13.2 g/kg.

The water removal rate varied between 78 kg/h and 86 kg/h depending on the day and internal load, to yield a total recovered water of 19,757 kg in June, 20,849 kg in July, and 21,317 kg in August, on an 8-hour per day basis. This recovered water is a valuable supplementary source of irrigation water, especially under local conditions of water shortage. The system’s economic sustainability under both unsubsidized and subsidized water price scenarios is confirmed through the feasibility of the system. These findings confirm the dual environmental and agronomic benefits of liquid desiccant technology, enabling more climate-resilient and sustainable greenhouse cultivation in arid and semi-arid regions. Future research should entail integrating renewable energy sources for desiccant regeneration and assessing long-term impacts on crop yield, water productivity, and system scalability across different crops and regions.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Mustafa Jaradat and Munjed Al Sharif; methodology, Mustafa Jaradat and Anas Y. Alshoubaki; software, Mustafa Jaradat and Nooh Alshyab; validation, Munjed Al Sharif, Mustafa Jaradat, and Anas Y. Alshoubaki; formal analysis, Anas Y. Alshoubaki; investigation, Arwa Abdelhay; resources, Serena Sandri and Al HayajnehAli ; data curation, Hayajneh, Luay Jum’a; writing—original draft preparation, Mustafa Jaradat, Anas Y. Alshoubaki; writing—review and editing, Munjed Al Sharif, Mustafa Jaradat, and Ismail Abushaikha; visualization, Luay Jum’a and Arwa Abdelhay; supervision, Serena Sandri and Ali ; project administration, Nooh Alshyab and Luay Jum’a; funding acquisition, Serena Sandri. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the PRIMA Programme (Horizon 2020, European Union), as part of the BONEX project, grant agreement number 2141 ‘Boosting Nexus Framework Implementation in the Mediterranean.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the German Jordanian University (GJU), represented by the seed grant fund SNREM 01/2024 from the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSA). This funding was supported for the construction of a liquid desiccant pilot plant.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- United Nations. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1). 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1.

- Achour, Y.; Ouammi, A.; Zejli, D. Technological progresses in modern sustainable greenhouses cultivation as the path towards precision agriculture. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 147, 111199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, R.; Karthikeyan, N.; Chaliha, S.; Dembele, B. Addressing climate and conflict-related loss and damage in fragile states: A focus on Mali. IIED. 2025. Available online: https://www.iied.org/22618iied.

- Begizew, G. Agricultural production system in arid and semi-arid regions. International Journal of Agricultural Science and Food Technology 2021, 7, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yang, Z.Q.; Lu, S.Y.; Zhang, Y.D.; Zheng, H. Effect mechanism of high temperature and high humidity stress on yield formation of cucumber. Chinese Journal of Agrometeorology 2022, 43, 392–407. [Google Scholar]

- Alar, H.S.; Sabado, D.C. Utilizing a greenhouse activities streamlining system towards accurate VPD monitoring for tropical plants. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Vision, Image and Signal Processing (ICVISP); IEEE, 2017; pp. 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashtoush, B.; Alshoubaki, A.Y. Solar-off-grid atmospheric water harvesting system: Performance analysis and evaluation in diverse climate conditions. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 906, 167600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Qu, H.; Yu, Z.G.; Zhang, Y.; Eey, T.J.; et al. A moisture-hungry copper complex harvesting air moisture for potable water and autonomous urban agriculture. Advanced Materials 2020, 32, 2002936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshiri, R.R.; Jones, J.W.; Thorp, K.R.; Ahmad, D.; Man, H.C.; Taheri, S. Review of optimum temperature, humidity, and vapour pressure deficit for microclimate evaluation and control in greenhouse cultivation of tomato: A review. International Agrophysics 2018, 32, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadiee, A.; Martin, V. Energy management in horticultural applications through the closed greenhouse concept: State of the art. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 5087–5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polivanova, O.B.; Bedarev, V.A. Hyperhydricity in plant tissue culture. Plants 2022, 11, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollet, I.V.; Pieters, J.G. (). Condensation and radiation transmittance of greenhouse cladding materials. Part 3: Results for glass plates and plastic films. Journal of Agricultural and Engineering Research 2000, 77, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, S.M.M.; Chavan, Y.A.; Pillai, M.R.; Diwate, V.M.; Oza, P.S.; Wagh, O.N. (). Real-time monitoring of temperature and humidity in agriculture automation. Journal of Survey in Fisheries Sciences 2023, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Chiarakul, P.; Pinich, S.; Sreshthaputra, A. Monitoring environmental factors associated with indoor growth chambers and greenhouses for cannabis cultivation. Journal of Architectural/Planning Research and Studies (JARS) 2024, 21, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, M.; Foroushani, S.; Sultan, M.; Bahrami, M. Comprehensive review on dehumidification strategies for agricultural greenhouse applications. Applied Thermal Engineering 2020, 181, 115978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, G.; Zhang, X. Molecular basis of cucumber fruit domestication. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2019, 47, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahia, E.M.; Gardea-Béjar, A.; Ornelas-Paz, J.D.J.; Maya-Meraz, I.O.; Rodríguez-Roque, M.J.; Rios-Velasco, C.; et al. Preharvest factors affecting postharvest quality. In Postharvest technology of perishable horticultural commodities; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khudhair, A.A.; Aljarah, N.S. The role of the relative humidity on the development of downy mildew infection of cucumber in the greenhouse in Baghdad. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; Institute of Physics, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ally, N.M.; Neetoo, H.; Ranghoo-Sanmukhiya, V.M.; Coutinho, T.A. Greenhouse-grown tomatoes: Microbial diseases and their control methods: A review. International Journal of Phytopathology 2023, 12, 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, B. Effects of environmental factors on crop diseases development. Journal of Plant Pathology & Microbiology 2021, 12, 553. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351956258.

- Lefers, R.M.; Srivatsa Bettahalli, N.M.; Fedoroff, N.V.; Ghaffour, N.; Davies, P.A.; Nunes, S.P.; et al. Hollow fibre membrane-based liquid desiccant humidity control for controlled environment agriculture. Biosystems Engineering 2019, 183, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoulem, M.; El Moueddeb, K.; Nehdi, E.; Boukhanouf, R.; Calautit, J.K. Greenhouse design and cooling technologies for sustainable food cultivation in hot climates: Review of current practice and future status. Biosystems Engineering 2019, 183, 121–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand Singh, M.; Singh, J.P.; Kumar Pandey, S.; Gladwin Cutting, N.; Sharma, P.; Shrivastav, V.; et al. A review of three commonly used techniques of controlling greenhouse microclimate. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 2018, 7, 3491–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulandaz, M.A.; Kabir, M.S.; Kabir, M.S.N.; Ali, M.; Reza, M.N.; Haque, M.A.; Jang, G.-H.; Chung, S.-O. Layout of Suspension-Type Small-Sized Dehumidifiers Affects Humidity Variability and Energy Consumption in Greenhouses. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cámara-Zapata, J.M.; Sánchez-Molina, J.; Rodriguez, F.; López, J. Evaluation of a dehumidifier in a mild weather greenhouse. Applied Thermal Engineering 2018, 146, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, M.; Foroushani, S.; Sultan, M.; Bahrami, M. Comprehensive review on dehumidification strategies for agricultural greenhouse applications. Applied Thermal Engineering 2020, 181, 115979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Gao, Z.; Guo, H.; Brad, R.; Waterer, D. Comparison of greenhouse dehumidification strategies in cold regions. Applied Engineering in Agriculture 2015, 31, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, M. Construction and analysis of heat-and mass exchangers for liquid desiccant systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Kassel, Kassel, Germany.

- Jaradat, M.; Al-Addous, M.; Albatayneh, A. Adaption of an evaporative desert cooler into a liquid desiccant air conditioner: Experimental and numerical analysis. Atmosphere 2019, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, M.; Fleig, D.; Vajen, K.; Jordan, U. Investigations of a dehumidifier in a solar-assisted liquid desiccant demonstration plant. Journal of Solar Energy Engineering 2019, 141, 031001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, M.; Albatayneh, A.; Juaidi, A.; Abdallah, R.; Ayadi, O.; Ibbini, J.; Campana, P.E. Liquid desiccant systems for cooling applications in broilers farms in humid subtropical climates. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2022, 51, 101902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, M.; Albatayneh, A.; Alsotary, O.; Hammad, R.; Juaidi, A.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Water harvesting system in greenhouses with liquid desiccant technology. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 415, 137587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbi, B.; Chen, Z.-H.; Sethuvenkatraman, S. Protected Cropping in Warm Climates: A Review of Humidity Control and Cooling Methods. Energies 2019, 12, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TIAX. Review of thermally activated technologies: Final report to the U.S. Department of Energy, the Distributed Energy Program. U.S. Department of Energy. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Öberg, V.; Goswami, D. A review of liquid-desiccant cooling. In Advances in solar energy; Böer, K., Ed.; American Solar Energy Society, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein, A. Review of liquid desiccant technology for HVAC applications. HVAC&R Research 2008, 14, 819–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenstein, A.I. Advanced commercial liquid-desiccant technology development study (NREL/TP-550-24688). National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jaradat, M.; Alsotary, O.; Juaidi, A.; Albatayneh, A.; Alzoubi, A.; Gorjian, S. Potential of Producing Green Hydrogen in Jordan. Energies 2022, 15, 9039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, M.; Al-Addous, M.; Albatayneh, A.; Dalala, Z.; Barbana, N. Potential study of solar thermal cooling in sub-Mediterranean climate. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, M.; Al Majali, H.; Bendea, C.; Bungau, C.C.; Bungau, T. Enhancing energy efficiency in buildings through PCM integration: A study across different climatic regions. Buildings 2024, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Addous, M.; Jaradat, M.; Bdour, M.; Dalala, Z.; Wellmann, J. Combined concentrated solar power plant with low-temperature multi-effect distillation. Energy Exploration & Exploitation 2020, 38, 1831–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, D.I.; Braun, J.E.; Klein, S.A. An effectiveness model of liquid-desiccant system heat/mass exchangers. Solar Energy 1989, 42, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, H.A.; Cabezas-Gómez, L.C. Effectiveness-NTU computation with a mathematical model for cross-flow heat exchangers. Brazilian Journal of Chemical Engineering 2007, 24, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, M.R. Properties of aqueous solutions of lithium and calcium chlorides: Formulations for use in air conditioning equipment design. International Journal of Thermal Sciences 2004, 43, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Zheng, J.; Celeste, L.; Guo, X.; Kholsa, S. Liquid desiccant dehumidification system for improving microclimate and plant growth in greenhouse cucumber production. Acta Horticulturae 2017, 1170, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, L.; Peña, X.; Pascual, C.; Prieto, J.; Ortiga, J.; Gommed, K. Design, simulation and testing of a hybrid liquid desiccant for independent control of temperature and humidity. In CISBAT 2015: Future Buildings and Districts – Sustainability from Nano to Urban Scale.; Lausanne, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lycoskoufis, I.; Mavrogianopoulos, G. A hybrid dehumidification system for greenhouses. Acta Horticulturae 2008, 797, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).