Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Geological and Environmental Context

2.1. Geological Setting

2.2. Environmental Characterization

3. Materials and Methods

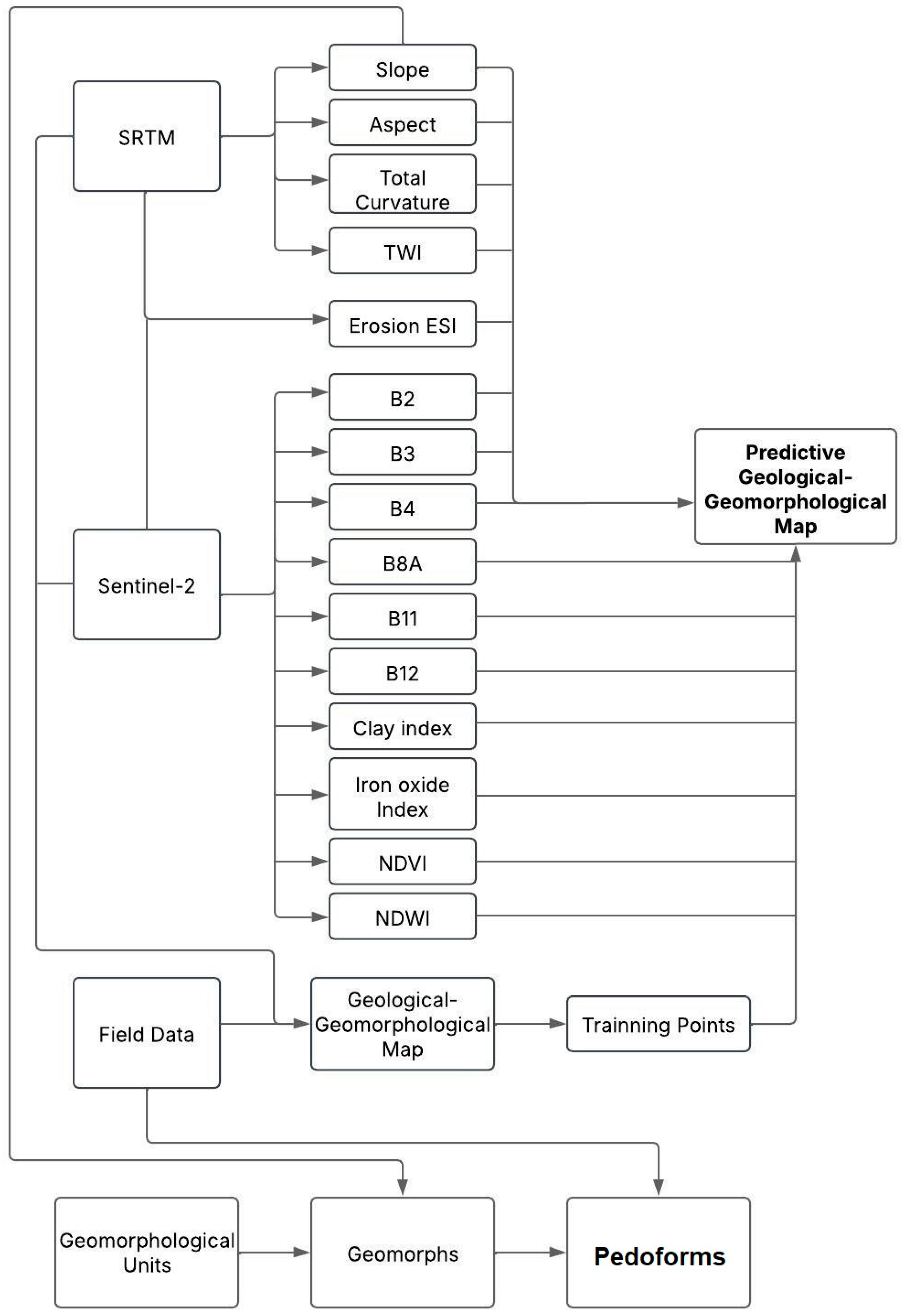

3.1. Geomorphological and Geological Classification Map Using Random Forest (Sentinel-2 & SRTM)

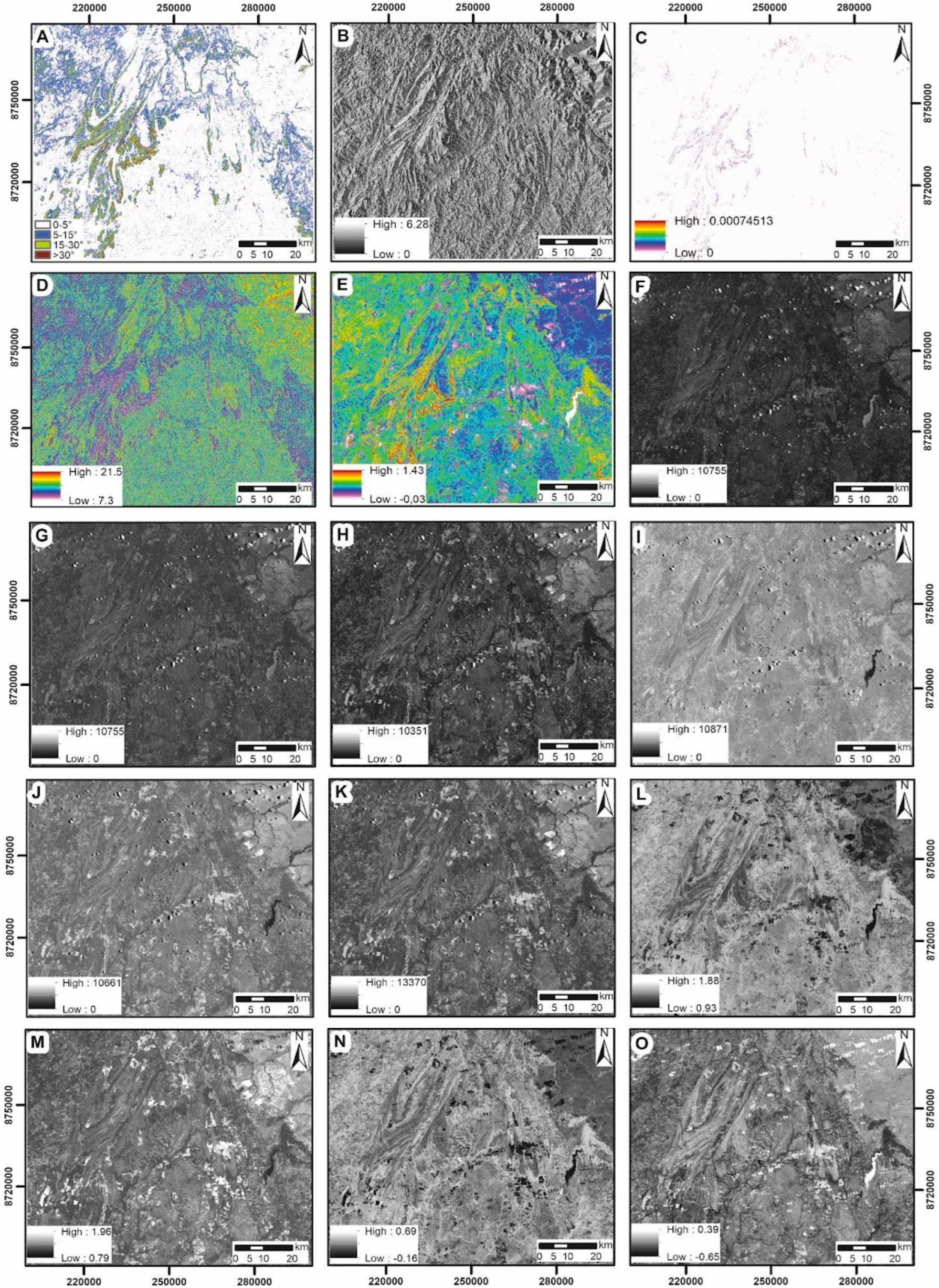

3.1.1. Sentinel-2 and SRTM Data

3.1.2. Random Forest Classification

3.1.3. Accuracy Assessment

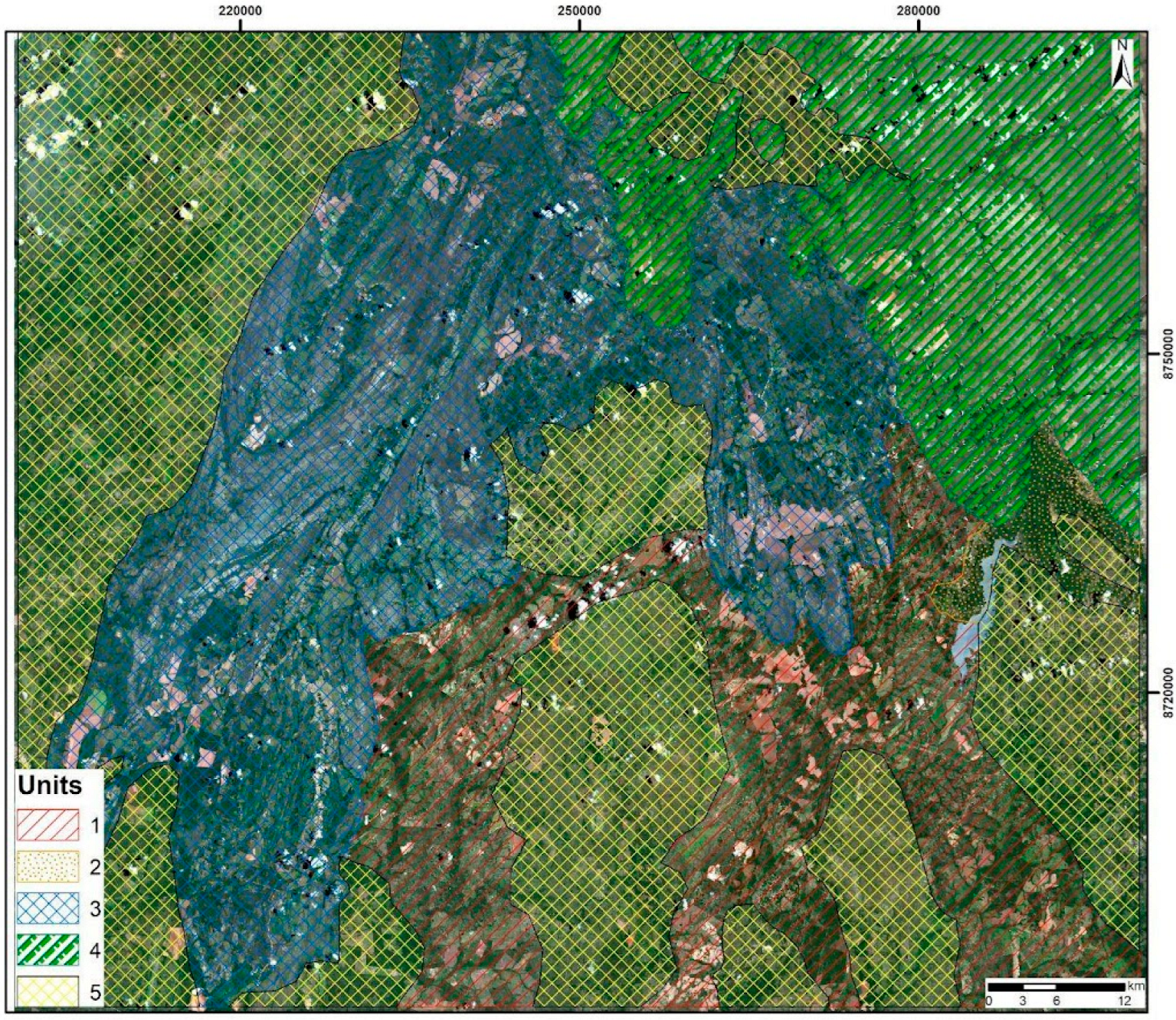

3.2. Pedo-Geomorphological Map

4. Results

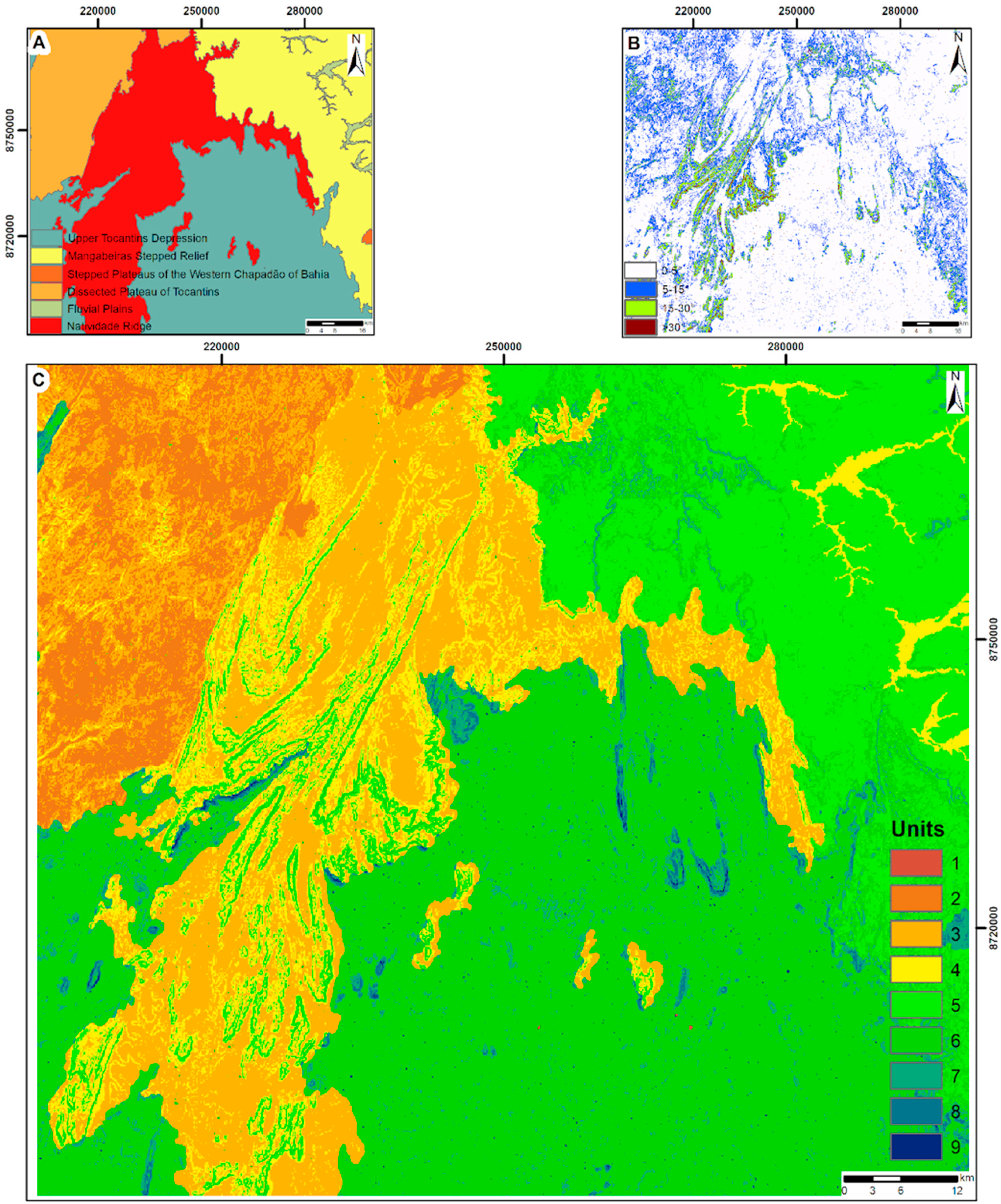

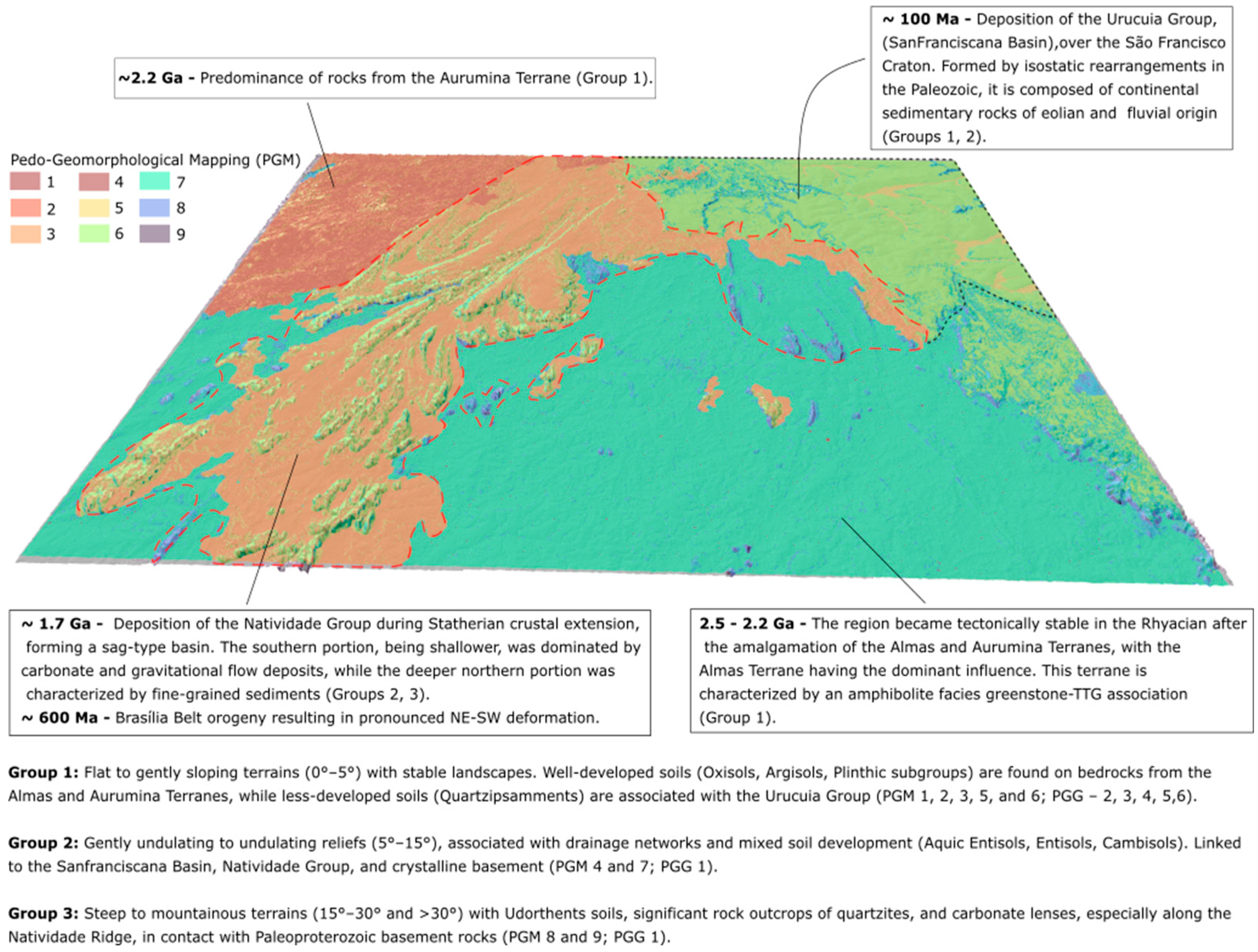

4.1. Pedo-Geomorphological Map (PGM)

4.2. Predictive Geological-Geomorphological Map (PGG Map)

5. Discussion

5.1. Relationship Between the Generated Maps and Landscape Evolution

5.2. Influence of Geology and Geomorphology in the Landscape Evolution

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lacerda, M.P.C. , Barbosa, I. O. Pedomorphogeological relationships and distribution of pedoforms in the Águas Emendadas ecological station, Federal District. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo 2012, 36, 709–721. [Google Scholar]

- Conacher, A.J. , Dalrymple, J B. The nine unit landsurface model. An approach to pedogeomorphic research. Geoderma, 1977, 18, 127–144. [Google Scholar]

- Toscani, R. , Campos, J.E.G., Martins-Ferreira, M.A.C., Matos, D.R., Borges, C.C.A., Dias, A.N.C., Chemale, F. The Statherian Natividade Basin evolution constrained by U–Pb geochronology, sedimentology, and paleogeography, central Brazil. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 2021, 112-2, 103618.

- Dardenne, M.A. The Brasília fold belt. Tectonic Evolution of South America; Cordani, E. J. Milani, A. T. Filho, Ed.; Sociedade Brasileira de Geologia: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2000; pp. 231–263. [Google Scholar]

- Valeriano, C.D.M. , Pimentel, M. M., Heilbron, M., Almeida, J. C. H., & Trouw, R. A. J. Tectonic evolution of the Brasília Belt, Central Brazil, and early assembly of Gondwana. Geological Society, London, Special Publications2008, 294-1, 197–210.

- Toscani, R. , Campos, J. E.G., Matos, D.R., Martins-Ferreira, M.A.C. Complex depositional environments on a siliciclastic carbonate platform with shallow-water turbidites: The Natividade Group, central Brazil. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 2021, 102, 102939. [Google Scholar]

- State of Tocantins, Brazil. Atividade do Programa de Zoneamento Ecológico-Econômico do Estado do Tocantins: Integração à Base de Dados Geográficos do Estado do Tocantins., 2012 Available online:. Available online: https://www.to.gov.br/seplan/zoneamento-ecologico-economico-do-estado-do-tocantins/5n96nvzropdp (accessed on 06 April 2025).

- Martins-Ferreira, M.A.C. , Chemale, F. , Coelho Dias, A.N.C., & Campos, J.E.G. Proterozoic intracontinental basin succession in the western margin of the São Francisco Craton: Constraints from detrital zircon geochronology. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 2018, 81, 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, F.F.M. , Hasui, Y., Brito Neves, B.B., Fuck, R.A. Brazilian structural provinces: An introduction. Earth-Science Reviews,1981, 17-1, 1–29.

- Almeida, F.F.M. O Cráton do São Francisco. Revista Brasileira de Geociências,1977, 7-4, 349–364.

- Pimentel, M.M. The tectonic evolution of the Neoproterozoic Brasília Belt, central Brazil: A geochronological and isotopic approach. Brazilian Journal of Geology,2016, 46-1, 67–82.

- Fuck, R.A. , Pimentel, M.M., Alvarenga, C.J.S., & Dantas, E.L. The Northern Brasília Belt. São Francisco Craton, Eastern Brazil. Tectonic Genealogy of a Miniature Continent Heilbron, M., Cordani, U. G., Alkmim F. F., Eds.; Springer, 2017; pp. 205–220.

- Saboia, A. M. , Oliveira, C. G., Dantas, E. L., Scandolara, J. E., Cordeiro, P., Rodrigues, J. B., & Sousa, I. M. C. The 2.26 to 2.18 Ga Arc-Related Magmatism of the Almas-Conceição do Tocantins Domain: An Early Stage of the São Francisco Paleocontinent Assembly in Central Brazil. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 2020, 104, 102757. [Google Scholar]

- Saboia, A. M. , Fuck, R. A., Dantas, E. L. Oliveira, C. G., Corrêa, R. T., Rodrigues, J. B., Scandolara, J. E., Costa, F. G., Cuadros, F. A., Uchigasaki, K. Paleoproterozoic (2.26–2.0 Ga) arc magmatism and geotectonic evolution of the Cavalcante-Natividade Block, Central Brazil. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2025, 154, 105350. [Google Scholar]

- Saboia, A. M.; Oliveira, C. G.; Dantas, E. L.; Cordeiro, P.; Scandolara, J. E.; Rodrigues, J. B.; Sousa, I. M. C. The Siderian crust (2. 47–2.3 Ga) of the Goiás Massif and its role as a building block of the São Francisco paleocontinent. Precambrian Res. 2020, 350, 105901. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlein, A.; Paim, P. S. G.; Tassinari, C. C. G.; Pedreira, A. J. Análise estratigráfica de bacias rifte Paleo-Mesoproterozoicas dos crátons Amazônico e São Francisco, Brasil. Geonomos 2015, 23(2), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboia, A. M. O vulcanismo em Monte do Carmo e Litoestratigrafia do Grupo Natividade, Estado de Tocantins; Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade de Brasília: Brasília, 2009; 96p. [Google Scholar]

- Schobbenhaus, C.; Bellizzia, A. (Coords.). Mapa geológico da América do Sul, escala 1:5.000.000; CGMW - CPRM - DNPM - UNESCO: Brasília, 2001; Available online: https://rigeo.sgb.gov.br/handle/doc/2542?mode=full (accessed on 06 April 2025).

- Fuck, R. A.; Dantas, E. L.; Pimentel, M. M.; Botelho, N. F.; Armstrong, R.; Laux, J. H.; Junges, S. L.; Soares, J. E.; Praxedes, I. F. Paleoproterozoic crust-formation and reworking events in the Tocantins Province, central Brazil: A contribution for Atlantica supercontinent reconstruction. Precambrian Res. 2014, 244, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, I. M. C.; Giustina, M. E. S. D.; Oliveira, C. G. Crustal evolution of the northern Brasília Belt basement, central Brazil: A Rhyacian orogeny coeval with a pre-Rodinia supercontinent assembly. Precambrian Res. 2016, 273, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins-Ferreira, M. A. C.; Dias, A. N. C.; Chemale, F.; Campos, J. E. G.; Seraine, M.; Novais-Rodrigues, E. Multistage crustal accretion by magmatic flare-up and quiescence intervals in the western margin of São Francisco Craton: U–Pb–Hf and geochemical constraints from the Almas Terrane. Gondwana Res. 2020, 85, 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, P. F. O.; Oliveira, C. G. The Goiás Massif: Implications for a pre-Columbia 2. 2–2.0 Ga continent-wide amalgamation cycle in central Brazil. Precambrian Res. 2017, 298, 403–420. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, E. L. C. C. A gênese e o contexto tectônico da mina Córrego Paiol, Terreno Almas-Conceição: um depósito de ouro hospedado em anfibolito do embasamento da Faixa de Dobramento Brasília; Tese de Doutorado, Universidade de Brasília: Brasília, 2001; 189p. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, C. C. A.; Toledo, C. L. B.; Silva, A. M.; Chemale, F.; Santos, B. A.; Figueiredo, F. L.; Zacchi, E. N. P. Unraveling a Hidden Rhyacian magmatic arc through provenance of metasedimentary rocks of the Crixás greenstone belt, Central Brazil. Precambrian Res. 2021, 353, 106022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadros, F. A.; Botelho, N. F.; Fuck, R. A.; Dantas, E. L. The peraluminous Aurumina Granite Suite in central Brazil: An example of mantle–continental crust interaction in a Paleoproterozoic cordilleran hinterland setting? Precambrian Res. 2017, 299, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J. B. S. Aspectos lito-estruturais e evolução crustal da região centro-norte de Goiás; Tese de Doutorado, Instituto de Geociências, Universidade Federal do Pará: Pará, 1984; 210p. [Google Scholar]

- Dardenne, M. A. , Giustina, M. E. S. D., Sabóia, A. M., Bogossian, J. Datação geocronológica U–Pb da sequência vulcânica de Almas, Tocantins. In Simpósio Geológico Centro-Oeste, 11; SBG: 2009; pp. 1 CD-ROM.

- Gorayeb, P. S. S.; Costa, J. B. S.; Lemos, R. L.; Gama, J. R. T.; Bemerguy, R. L.; Hasui, Y. O Pré-Cambriano da Região de Natividade, GO. Rev. Bras. Geoci. 1988, 18, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J. E. G.; Dardenne, M. A. Origem e evolução tectônica da Bacia Sanfranciscana. Rev. Bras. Geoci. 1997, 27(3), 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomfim, L. F. C.; Gomes, R. A. D. Aquífero Urucuia – Geometria e Espessura: Idéias para Discussão. In XIII Congresso Brasileiro de Águas Subterrâneas; Associação Brasileira de Águas Subterrâneas: São Paulo, 2002; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Köppen, W. Climatología: Con un estudio de los climas de la tierra; Fondo de Cultura Económica: México, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Batalha, M. A. O cerrado não é um bioma. Biota Neotrop. 2011, 11, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J. F.; Walter, B. M. T. Physiognomies of the Cerrado Biome. In Cerrado: Environment and Flora; Sano, S. M., Almeida, S. P., Ribeiro, J. F., Eds.; Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária - Centro de Pesquisa Agropecuária dos Cerrados: Planaltina, DF, Brazil, 2008; pp. 152–212. [Google Scholar]

- Pelegrino, M. H. P.; Guilherme, L. R. G.; Lima, G. O.; Poppiel, R.; Adhikari, K.; Demattê, J. M.; Curi, N.; Menezes, M. D. Optimizing soil texture spatial prediction in the Brazilian Cerrado: Insights from random forest and spectral data. Geoderma Regional 2025, 40, e00922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Brasil | Mapa de Biomas do Brasil. Escala 1:5,000,000. IBGE – Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 2004. URL: https://www.ibge.gov.br/geociencias/informacoes-ambientais/vegetacao/15842-biomas.html. (accessed on 06 April 2025).

- Motta, P. E. F.; Curi, N.; Franzmeier, D. P. Relation of soils and geomorphic surfaces in the Brazilian Cerrado. In The Cerrado. In The Cerrados of Brazil: Ecology and Natural History of a Neotropical Savanna; Oliveira, P. S., Marquis, R. J., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, 2002; p. 368. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, J. F.; Walter, B. M. T. Fitofisionomias do bioma cerrado. In Cerrado: Ambiente e Flora; Sano, S. M., Almeida, S. P. de, Eds.; EMBRAPA-CPAC: Planaltina, DF, 1998; pp. 89–166. [Google Scholar]

- McBratney, A. B.; Mendonça Santos, M. L.; Minasny, B. On digital soil mapping. Geoderma 2003, 117, 3–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenny, H. Factors of soil formation. Soil Sci. 1941, 52, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State of Tocantins, Brazil. Plano de informação de solos em escala 1:250.000 com recorte espacial para o sudeste do Estado do Tocantins: Atualização de dados vetoriais temáticos geoespaciais da Base de Dados Geográficos. Atividade do Programa de Zoneamento Ecológico-Econômico do Estado do Tocantins. Integra a Base de Dados Geográficos do Estado do Tocantins, 2012. URL: https://geoportal.to.gov.br/geonetwork/srv/api/records/e7d58a49-ed18-4ab8-ad9b-0d6049bd4a30, (accessed on 06 April 2025).

- Van der Werff, H.; Van der Meer, F. Sentinel-2A MSI and Landsat 8 OLI provide data continuity for geological remote sensing. Remote Sens. 2016, 8(11), 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Radzuma, T.; Mukosi, N. C. Usefulness of Sentinel-2 satellite data to aid in geoscientific mapping work: A case study of Giyani Greenstone Belt area. Episodes J. Int. Geoscience 2023, 46(3), 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malainine, C. E.; Raji, O.; Ouabid, M.; Bodinier, J. L.; El Messbahi, H. Prospectivity mapping of carbonatite-associated iron oxide deposits using an integration process of ASTER and Sentinel-2A multispectral data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43(13), 4951–4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B. C. A normalized difference water index for remote sensing of vegetation liquid water from space. Imaging Spectrometry 1995, 2480, 225–236. [Google Scholar]

- Sabins, F. F. Remote sensing for mineral exploration. Ore Geol. Rev. 1999, 14, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danoedoro, P.; Zukhrufiyati, A. Integrating spectral indices and geostatistics based on Landsat-8 imagery for surface clay content mapping in Gunung Kidul area, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 36th Asian Conference on Remote Sensing, Asia Quezon, Metro Manila, Philippines, 12 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Casari, R. A. D. C. N.; Neumann, M. B.; Ribeiro, W. Q.; Olivetti, D.; Tavares, C. J.; Pereira, L. F.; Ramos, M. L. G.; Pereira, A. F.; Silva Neto, S. P.; Roig, H. L. Estimation of Soybean Evapotranspiration Using SSEBop Model with High-Resolution Imagery from an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Rev. Bras. Meteorol. 2024, 39, e39240007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeriano, M. M.; Rossetti, D. F. Topodata: Brazilian full coverage refinement of SRTM data. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 32(2), 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, G. P. M.; Pistune, H. F.; Silva, M. A. S. Applications of computing in geomorphology studies–A case study. Iberoam. J. Appl. Comput. 2023, 11(1).

- Passy, P.; Théry, S. The use of SAGA GIS modules in QGIS. QGIS Gen. Tools 2018, 1, 107–149 822. [Google Scholar]

- Vujovi´c, F.; ´Culafi´c, G.; Valjarevi´c, A.; Br ¯danin, E.; Durlevi´c, U. Comparative geomorphometric analysis of drainage basin using AW3D30 model in ArcGIS and QGIS environment: Case Study of the Ibar River Drainage Basin, Montenegro. Agric. For. 2024, 70(1), 217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Milevski, I. Estimation of soil erosion risk in the upper part of Bregalnica watershed—Republic of Macedonia, based on digital elevation model and satellite imagery. In Proceedings from the 5th International Conference on Geographic Information Systems, Fatih University, Istanbul, 08; pp 351–358. 20 July.

- Chapungu, L.; Nhamo, G.; Dube, K.; Chikodzi, D. Soil erosion in the savanna biome national parks of South Africa. Phys. Chem. Earth, Parts A/B/C 2023, 130, 103376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabosa, L. F. C.; Yokoyama, E.; Mendes, T. L.; Almo, P. M.; de Aguiar, G. Z. Utilizing Random Forest algorithm for identifying mafic and ultramafic rocks in the Gameleira Suite, Archean-Paleoproterozoic basement of the Brasília Belt, Brazil. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2024, 141, 104952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, C. T.; Oka-Fiori, C.; Santos, L. J. C.; Sirtoli, A. E.; Silva, C. R.; Botelho, M. F. Soil prediction using artificial neural networksvand topographic attributes. Geoderma 2013, 195, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acton, D. F. The relationship of pattern and gradient of slopes to soil type. Can. J. Soil Sci. 1965, 45(1), 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrard, A. J. Soil geomorphology; Springer Science & Business Media: 1992; p 272.

- Ippoliti, R. G. A.; Costa, L. M.; Schaefer, C. E. G. R.; Fernandes Filho, E. I.; Gaggero, M. R.; Souza, E. Análise digital do terreno: ferramenta na identificação de pedoformas em microbacia na região de “Mar de Morros” (MG). Rev. Bras. Ciência Solo 2005, 29, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A. B. A.; Barbosa, V. R. F.; Faria, K. M. S.; Martins, E. S.; Soares Neto, G. B. Geomorphologic Map of the Brazilian Cerrado by geomorphometric archetypes. Rev. Bras. Geomorfologia 2022, 23(3), 1674–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leão, T. P. Solos: uma introdução; Editora Universidade de Brasília: Brasília, 2024; ISBN 978-65-5846-063-3. [Google Scholar]

- Dantas, M. E.; Shinzato, E.; Carvalho Filho, A. de; Lumbreras, J. F.; Teixeira, W. G.; Rocha, M. G.; Machado, M. F. Origem das 846 paisagens do estado do Tocantins. In: Rocha, M. G. (Org.), Geodiversidade do Estado do Tocantins. In Rocha, M. G. (Org.), Geodiversidade do Estado do Tocantins; CPRM: Goiânia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jakhmola, R. P. , Dash, C., Singh, S., Patel, N. K., Verma, A. K., Pati, P., Awasthi, A. K., Sarma, J. N. Holocene landscape evolution of the Brahmaputra River valley in the upper Assam Basin (India): Deduced from the soil-geomorphic studies. Quaternary Science Reviews, 316, 2023, 108243.

- Campos, J. E. G. Hidrogeologia do Distrito Federal: bases para a gestão dos recursos hídricos subterrâneos. Revista Brasileira de Geociências, 34(1), 2004, 41-48.

- Martins-Ferreira, M. A. C. , & Campos, J. E. G. Compartimentação geomorfológica como suporte para estudos de evolução 854 geotectônica: Aplicação na região da Chapada dos Veadeiros, GO. Revista Brasileira de Geomorfologia, 18(3), 2017.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).