Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Summary of Models for In Vitro Studies

1.2. Comparison of 2D and 3D Models

1.3. Spheroids in Personalized Medicine

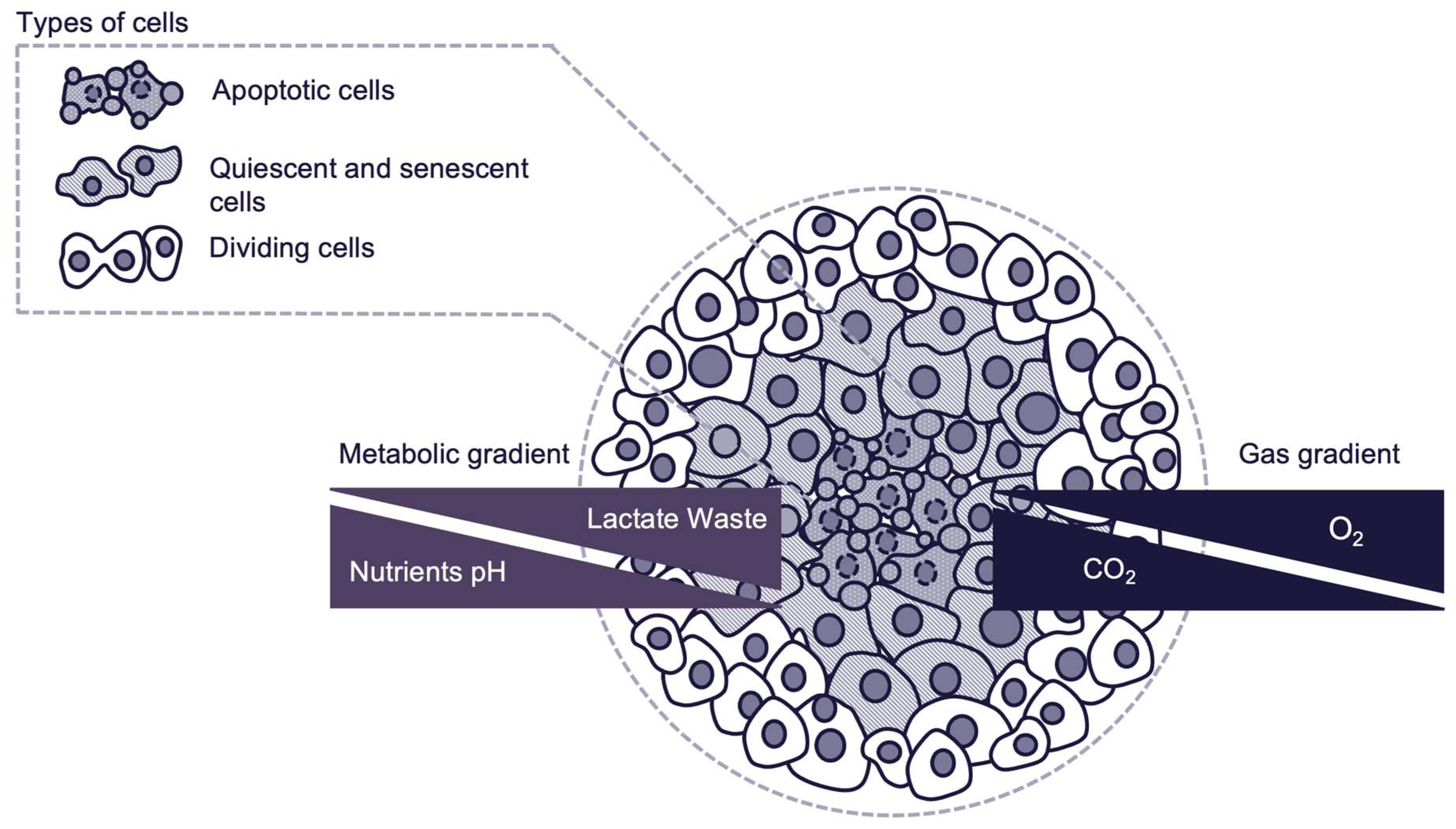

- Proliferative outer layer: Consisting of actively dividing cells, with high accessibility to oxygen and nutrients.

- Quiescent intermediate layer: Consisting of quiescent and senescent cells with reduced metabolic activity due to limited nutrient and oxygen availability.

- Hypoxic apoptotic core: Consisting of cells in apoptotic state due to severe nutrient and oxygen deprivation. Core environment mimics what is observed in poorly vascularized tumor regions in vivo.

1.4. Applications of Spheroids Models

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

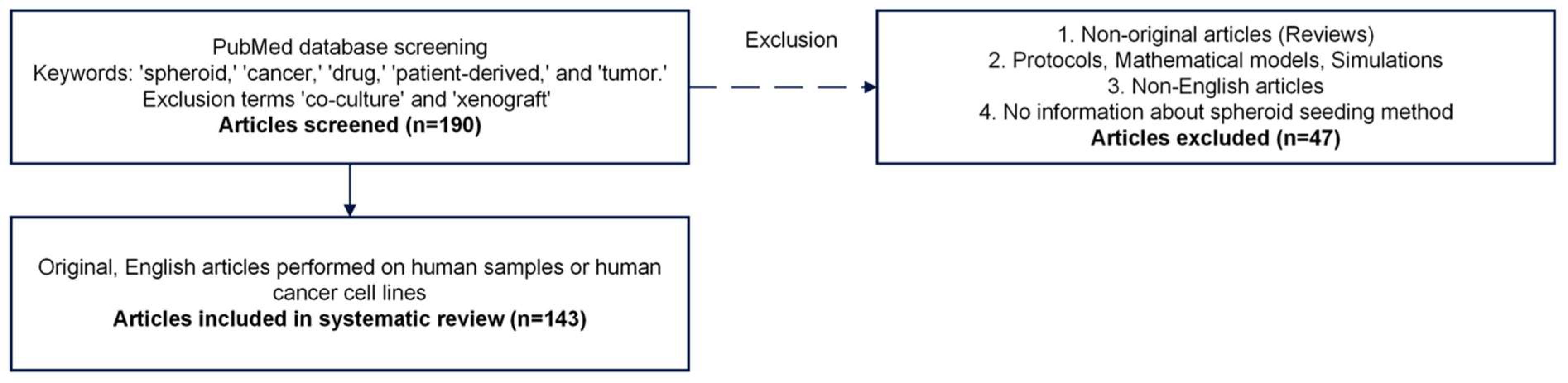

3.1. Database Screening

3.2. Systematic Review

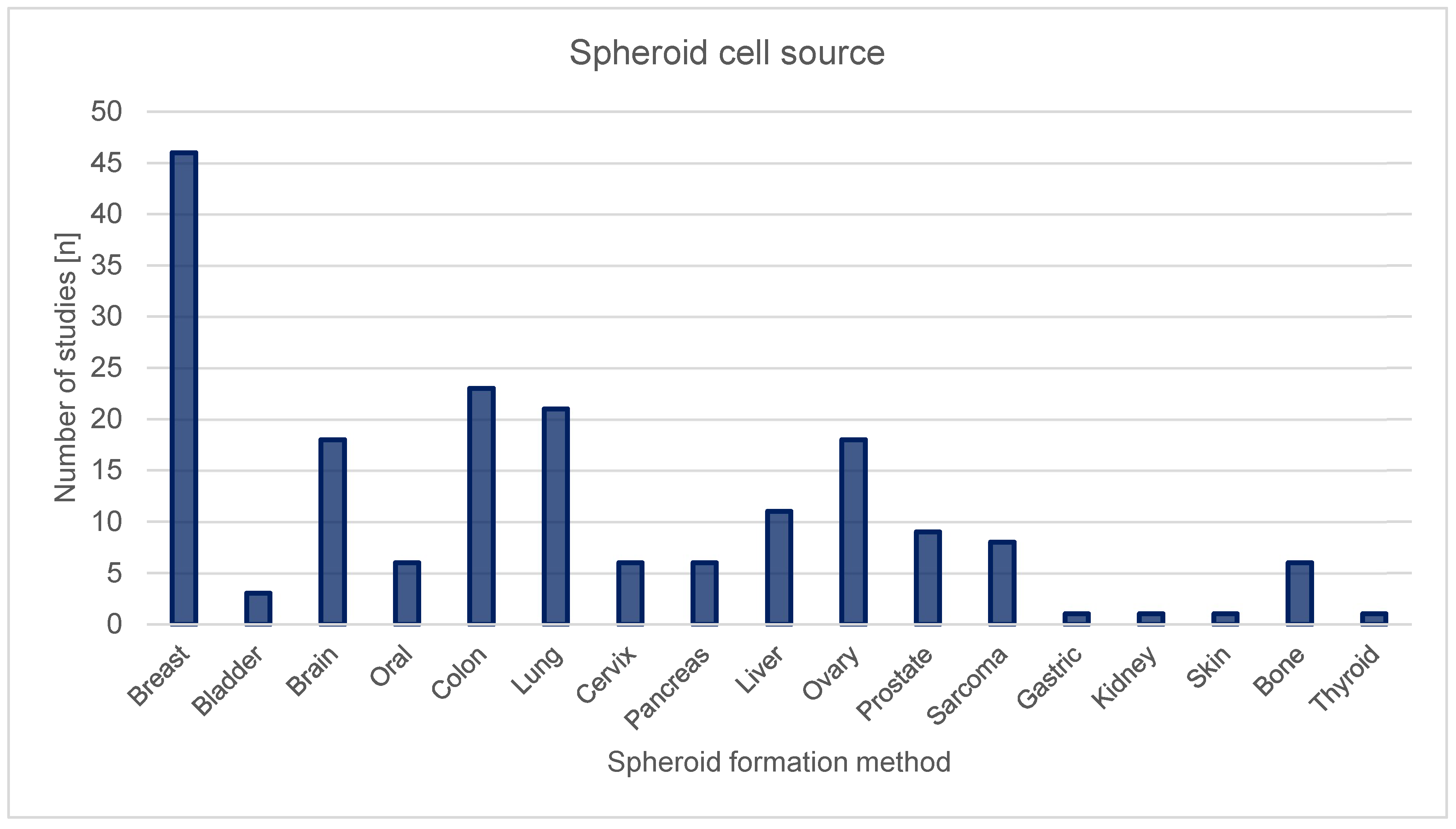

3.2.1. Source of Spheroids

Breast Cancer

Colon Cancer

Lung Cancer

Ovarian Cancer

Brain Cancer

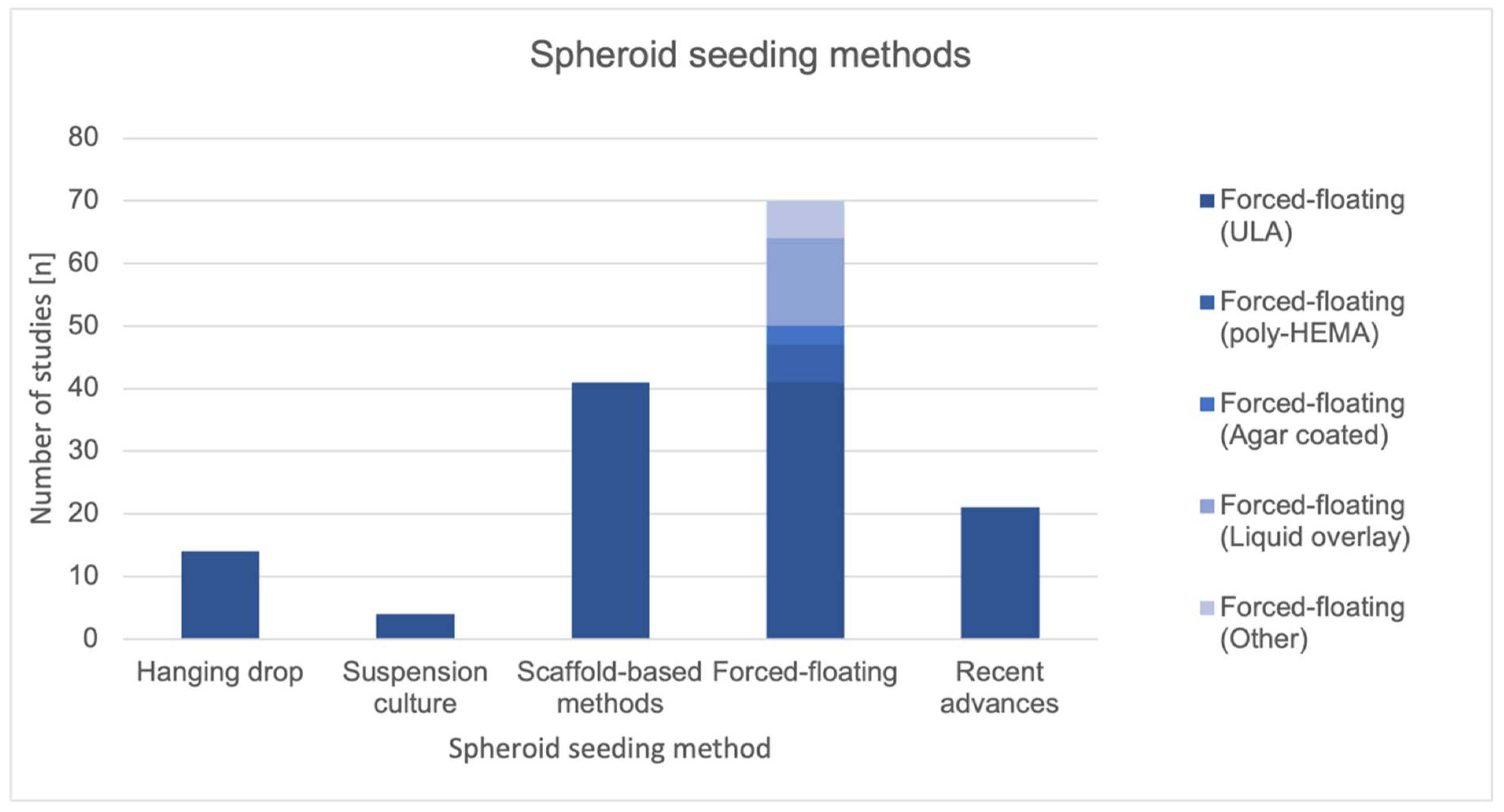

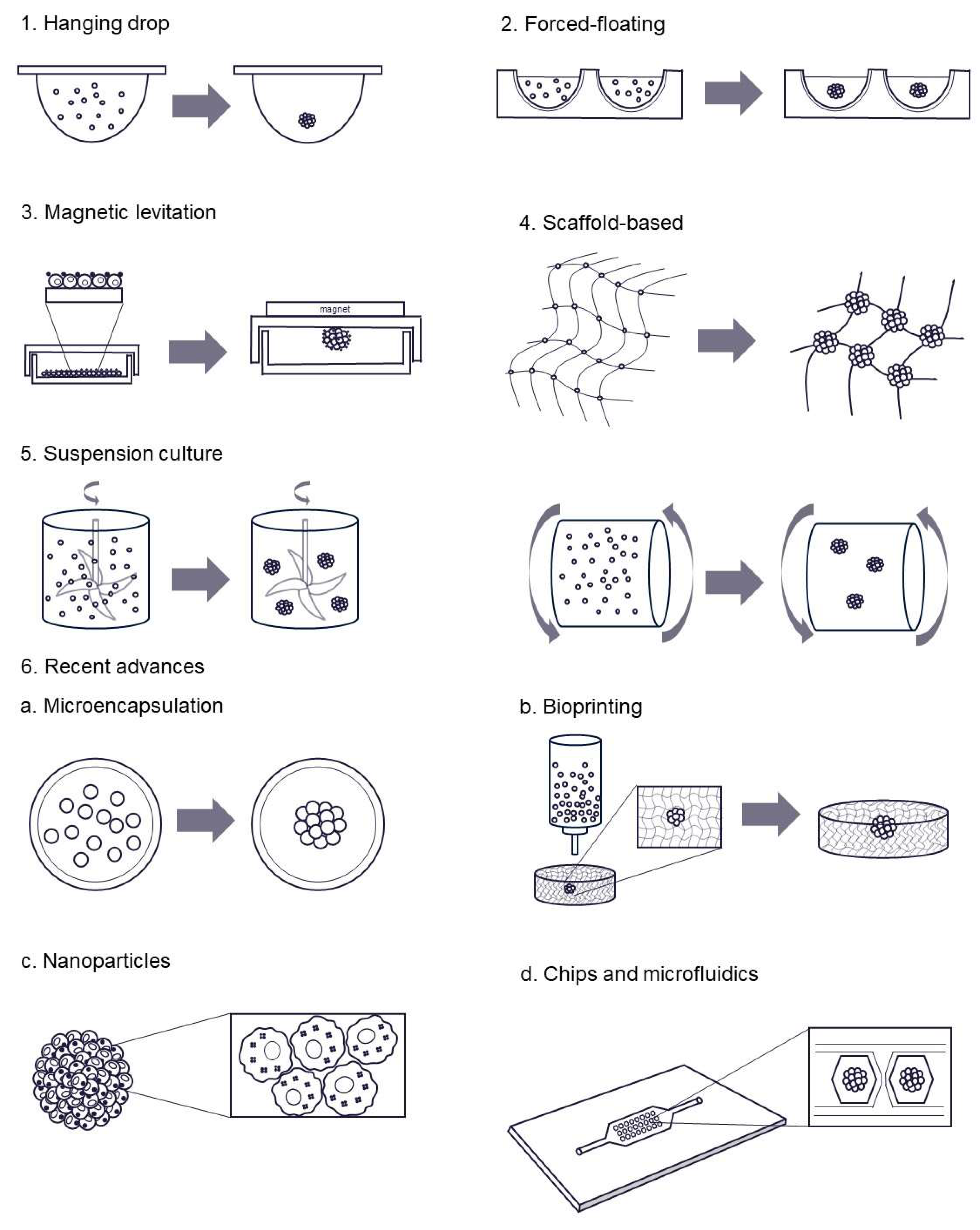

3.2.2. Spheroid Seeding Methods

Forced Floating

Scaffold-Based

Hanging Drop

Suspension Culture

Recent Advances in Spheroid Seeding Methods

Magnetic Levitation

Summary of Spheroid Seeding Method

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung lymphoma |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| Poly-HEMA | Poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate |

| PLGA | poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid |

| SCLC | Small cell lung cancer |

| ULA | Ultra-low attachment |

References

- Harrison, R.G. The Outgrowth of the Nerve Fiber as a Mode of Protoplasmic Movement. J Exp Zool 1910, 9, 787–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, W.F.; Syverton, J.T.; Gey, G.O. Studies on the Propagation in Vitro of Poliomyelitis Viruses. IV. Viral Multiplication in a Stable Strain of Human Malignant Epithelial Cells (Strain HeLa) Derived from an Epidermoid Carcinoma of the Cervix. J Exp Med 1953, 97, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Raju, P. 5.42 - In Vitro Cancer Model for Drug Testing. In Comprehensive Biotechnology (Second Edition); Moo-Young, M., Ed.; Academic Press: Burlington, 2011; pp. 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, R.M.; McCredie, J.A.; Inch, W.R. Growth of Multicell Spheroids in Tissue Culture as a Model of Nodular Carcinomas2. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 1971, 46, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslin, S.; O’Driscoll, L. The Relevance of Using 3D Cell Cultures, in Addition to 2D Monolayer Cultures, When Evaluating Breast Cancer Drug Sensitivity and Resistance. Oncotarget 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoarau-Véchot, J.; Rafii, A.; Touboul, C.; Pasquier, J. Halfway between 2D and Animal Models: Are 3D Cultures the Ideal Tool to Study Cancer-Microenvironment Interactions? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslin, S.; O’Driscoll, L. Three-Dimensional Cell Culture: The Missing Link in Drug Discovery. Drug Discovery Today 2013, 18, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C.; Teng, Y. Is It Time to Start Transitioning From 2D to 3D Cell Culture? Front Mol Biosci. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodbye, Flat Biology? Nature 2003, 424, 861–861. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontoura, J.C.; Viezzer, C.; dos Santos, F.G.; Ligabue, R.A.; Weinlich, R.; Puga, R.D.; Antonow, D.; Severino, P.; Bonorino, C. Comparison of 2D and 3D Cell Culture Models for Cell Growth, Gene Expression and Drug Resistance. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2020, 107, 110264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi-Mendes, T.; Eduardo, R.; Domenici, G.; Brito, C. 3D Cancer Models: Depicting Cellular Crosstalk within the Tumour Microenvironment. Cancers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habanjar, O.; Diab-Assaf, M.; Caldefie-Chezet, F.; Delort, L. 3D Cell Culture Systems: Tumor Application, Advantages, and Disadvantages. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamb, A. What’s Wrong with Our Cancer Models? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2005, 4, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilazieva, Z.; Ponomarev, A.; Rutland, C.; Rizvanov, A.; Solovyeva, V. Promising Applications of Tumor Spheroids and Organoids for Personalized Medicine. Cancers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, P.; Bentivoglio, V.; Varani, M.; Signore, A. Three-Dimensional In Vitro Tumor Spheroid Models for Evaluation of Anticancer Therapy: Recent Updates. Cancers 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Harane, S.; Zidi, B.; El Harane, N.; Krause, K.-H.; Matthes, T.; Preynat-Seauve, O. Cancer Spheroids and Organoids as Novel Tools for Research and Therapy: State of the Art and Challenges to Guide Precision Medicine. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agastin, S.; Giang, U.-B.T.; Geng, Y.; DeLouise, L.A.; King, M.R. Continuously Perfused Microbubble Array for 3D Tumor Spheroid Model. Biomicrofluidics 2011, 5, 024110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhasan, L.; Qi, A.; Al-Abboodi, A.; Rezk, A.; Chan, P.P.Y.; Iliescu, C.; Yeo, L.Y. Rapid Enhancement of Cellular Spheroid Assembly by Acoustically Driven Microcentrifugation. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2016, 2, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.J.; Kim, H.S.; Kwon, J.A.; Song, J.; Choi, I. Adjustable and Versatile 3D Tumor Spheroid Culture Platform with Interfacial Elastomeric Wells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 6924–6932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Árnadóttir, S.S.; Jeppesen, M.; Lamy, P.; Bramsen, J.B.; Nordentoft, I.; Knudsen, M.; Vang, S.; Madsen, M.R.; Thastrup, O.; Thastrup, J.; L Andersen, C. Characterization of Genetic Intratumor Heterogeneity in Colorectal Cancer and Matching Patient-Derived Spheroid Cultures. Molecular Oncology 2018, 12, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, N.; Seo, O.W.; Lee, J.; Hulme, J.; An, S.S.A. Real-Time Monitoring of Cisplatin Cytotoxicity on Three-Dimensional Spheroid Tumor Cells. Drug Des Devel Ther 2016, 10, 2155–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, R.M.; Calabro-Jones, P.; Thomas, T.N.; Sharp, T.R.; Byfield, J.E. Surgical Adjuvant Therapy in Colon Carcinoma: A Human Tumor Spheroid Model for Evaluating Radiation Sensitizing Agents. Cancer 1981, 47, 2349–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomä, P.; Impidjati; Reininger-Mack, A.; Zhang, Z.; Thielecke, H.; Robitzki, A. A More Aggressive Breast Cancer Spheroid Model Coupled to an Electronic Capillary Sensor System for a High-Content Screening of Cytotoxic Agents in Cancer Therapy: 3-Dimensional in Vitro Tumor Spheroids as a Screening Model. J Biomol Screen 2005, 10, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, L.; Yeap, S.K.; Ali, N.M.; Ho, W.Y.; Ky, H.; Satharasinghe, D.A.; Liew, W.C.; Tan, S.W.; Wang, M.-L.; Cheong, S.K.; Ong, H.K. Phenotypic and microRNA Characterization of the Neglected CD24+ Cell Population in MCF-7 Breast Cancer 3-Dimensional Spheroid Culture. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association 2020, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, E.A.; Gencoglu, M.F.; Corbett, D.C.; Stevens, K.R.; Peyton, S.R. An Omentum-Inspired 3D PEG Hydrogel for Identifying ECM-Drivers of Drug Resistant Ovarian Cancer. APL Bioengineering 2019, 3, 026106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, J.; Egan, T.; Mercier, P.; Zustiak, S.P. Glioblastoma Spheroid Growth and Chemotherapeutic Responses in Single and Dual-Stiffness Hydrogels. Acta Biomaterialia 2023, 163, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calori, I.R.; Alves, S.R.; Bi, H.; Tedesco, A.C. Type-I Collagen/Collagenase Modulates the 3D Structure and Behavior of Glioblastoma Spheroid Models. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Wen, J.; Su, Y.; Ma, H. Microfluidic Platform for Studying the Anti-Cancer Effect of Ursolic Acid on Tumor Spheroid. ELECTROPHORESIS 2022, 43, 1466–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Liu, W.; Yan, B. Breast Cancer MCF-7 Cell Spheroid Culture for Drug Discovery and Development. J Cancer Ther. 2022, 13, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.C.W.; Gupta, M.; Cheung, K.C. Alginate-Based Microfluidic System for Tumor Spheroid Formation and Anticancer Agent Screening. Biomedical Microdevices 2010, 12, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ma, N.; Sun, X.; Li, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, F.; Sun, S.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Ye, H.; Ge, J.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, X.; Leong, K.; Chen, Y.; Gu, Z. Automated Evaluation of Tumor Spheroid Behavior in 3D Culture Using Deep Learning-Based Recognition. Biomaterials 2021, 272, 120770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, V.; Esteves, F.; Chakrabarty, A.; Cockle, J.; Short, S.; Brüning-Richardson, A. High-Content Analysis of Tumour Cell Invasion in Three-Dimensional Spheroid Assays. Oncoscience 2015, 2, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Close, D.A.; Johnston, P.A. Detection and Impact of Hypoxic Regions in Multicellular Tumor Spheroid Cultures Formed by Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells Lines. SLAS Discovery 2022, 27, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.; Meunier, L.; Barbe, L.; Provencher, D.; Guenat, O.; Gervais, T.; Mes-Masson, A.-M. Empirical Chemosensitivity Testing in a Spheroid Model of Ovarian Cancer Using a Microfluidics-Based Multiplex Platform. Biomicrofluidics 2013, 7, 011805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, V.; Fürst, T.; Gurská, S.; Džubák, P.; Hajdúch, M. Evaporation-Reducing Culture Condition Increases the Reproducibility of Multicellular Spheroid Formation in Microtiter Plates. JoVE 2017, e55403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, V.; Fürst, T.; Gurská, S.; Džubák, P.; Hajdúch, M. Reproducibility of Uniform Spheroid Formation in 384-Well Plates: The Effect of Medium Evaporation. SLAS Discovery 2016, 21, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M.L.; Bruselles, A.; Francescangeli, F.; Pucilli, F.; Vitale, S.; Zeuner, A.; Tartaglia, M.; Baiocchi, M. Colorectal Cancer Spheroid Biobanks: Multi-Level Approaches to Drug Sensitivity Studies. Cell Biology and Toxicology 2018, 34, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamecha, D.; Le, D.; Chakravarty, T.; Perera, K.; Dutta, A.; Menon, J.U. Fabrication of PNIPAm-Based Thermoresponsive Hydrogel Microwell Arrays for Tumor Spheroid Formation. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2021, 125, 112100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D.R.; Moreira, A.F.; Correia, I.J. The Effect of the Shape of Gold Core–Mesoporous Silica Shell Nanoparticles on the Cellular Behavior and Tumor Spheroid Penetration. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 7630–7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenici, G.; Eduardo, R.; Castillo-Ecija, H.; Orive, G.; Montero Carcaboso, Á.; Brito, C. PDX-Derived Ewing’s Sarcoma Cells Retain High Viability and Disease Phenotype in Alginate Encapsulated Spheroid Cultures. Cancers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufau, I.; Frongia, C.; Sicard, F.; Dedieu, L.; Cordelier, P.; Ausseil, F.; Ducommun, B.; Valette, A. Multicellular Tumor Spheroid Model to Evaluate Spatio-Temporal Dynamics Effect of Chemotherapeutics: Application to the Gemcitabine/CHK1 Inhibitor Combination in Pancreatic Cancer. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eetezadi, S.; Evans, J.C.; Shen, Y.-T.; de Souza, R.; Piquette-Miller, M.; Allen, C. Ratio-Dependent Synergism of a Doxorubicin and Olaparib Combination in 2D and Spheroid Models of Ovarian Cancer. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2018, 15, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, H.; Kimura, R.; Onuma, S.; Ito, A.; Yu, Y.; Yoshino, Y.; Matsunaga, T.; Endo, S.; Ikari, A. Elevation of Anticancer Drug Toxicity by Caffeine in Spheroid Model of Human Lung Adenocarcinoma A549 Cells Mediated by Reduction in Claudin-2 and Nrf2 Expression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eimer, S.; Dugay, F.; Airiau, K.; Avril, T.; Quillien, V.; Belaud-Rotureau, M.-A.; Belloc, F. Cyclopamine Cooperates with EGFR Inhibition to Deplete Stem-like Cancer Cells in Glioblastoma-Derived Spheroid Cultures. Neuro-Oncology 2012, 14, 1441–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sadek, I.A.; Miyazawa, A.; Shen, L.T.-W.; Makita, S.; Mukherjee, P.; Lichtenegger, A.; Matsusaka, S.; Yasuno, Y. Three-Dimensional Dynamics Optical Coherence Tomography for Tumor Spheroid Evaluation. Biomed. Opt. Express 2021, 12, 6844–6863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enmon, R.M.; O’Connor, K.C.; Lacks, D.J.; Schwartz, D.K.; Dotson, R.S. Dynamics of Spheroid Self-Assembly in Liquid-Overlay Culture of DU 145 Human Prostate Cancer Cells. Biotechnol Bioeng 2001, 72, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flørenes, V.A.; Flem-Karlsen, K.; McFadden, E.; Bergheim, I.R.; Nygaard, V.; Nygård, V.; Farstad, I.N.; Øy, G.F.; Emilsen, E.; Giller-Fleten, K.; Ree, A.H.; Flatmark, K.; Gullestad, H.P.; Hermann, R.; Ryder, T.; Wernhoff, P.; Mælandsmo, G.M. A Three-Dimensional Ex Vivo Viability Assay Reveals a Strong Correlation Between Response to Targeted Inhibitors and Mutation Status in Melanoma Lymph Node Metastases. Translational Oncology 2019, 12, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Li, X.B.; Wang, L.X.; Lv, X.H.; Lu, Z.; Wang, F.; Xia, Q.; Yu, L.; Li, C.M. One-Step Dip-Coating-Fabricated Core–Shell Silk Fibroin Rice Paper Fibrous Scaffolds for 3D Tumor Spheroid Formation. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 7462–7471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.J.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, X.X.; Kang, Y.J.; Lu, Z.S.; Li, Y.; Li, C.M.; Yu, L. Spontaneous Formation of Tumor Spheroid on a Hydrophilic Filter Paper for Cancer Stem Cell Enrichment. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2019, 174, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wu, M.; Luan, Q.; Papautsky, I.; Xu, J. Acoustic Bubble for Spheroid Trapping, Rotation, and Culture: A Tumor-on-a-Chip Platform (ABSTRACT Platform). Lab Chip 2022, 22, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencoglu, M.F.; Barney, L.E.; Hall, C.L.; Brooks, E.A.; Peyton, S.R. Comparative Study of Multicellular Tumor Spheroid Formation Methods and Implications for Drug Screening. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2018, 4, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendre, D.A.J.; Ameti, E.; Karenovics, W.; Perriraz-Mayer, N.; Triponez, F.; Serre-Beinier, V. Optimization of Tumor Spheroid Model in Mesothelioma and Lung Cancers and Anti-Cancer Drug Testing in H2052/484 Spheroids. Oncotarget 2021, 12, No–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheytanchi, E.; Naseri, M.; Karimi-Busheri, F.; Atyabi, F.; Mirsharif, E.S.; Bozorgmehr, M.; Ghods, R.; Madjd, Z. Morphological and Molecular Characteristics of Spheroid Formation in HT-29 and Caco-2 Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines. Cancer Cell International 2021, 21, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goisnard, A.; Daumar, P.; Dubois, C.; Aubel, C.; Roux, M.; Depresle, M.; Gauthier, J.; Vidalinc, B.; Penault-Llorca, F.; Mounetou, E.; Bamdad, M. LightSpot®-FL-1 Fluorescent Probe: An Innovative Tool for Cancer Drug Resistance Analysis by Direct Detection and Quantification of the P-Glycoprotein (P-Gp) on Monolayer Culture and Spheroid Triple Negative Breast Cancer Models. Cancers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Chen, Y.; Ji, W.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Ge, R. Enrichment of Cancer Stem Cells by Agarose Multi-Well Dishes and 3D Spheroid Culture. Cell and Tissue Research 2019, 375, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, J.; Jacobi, C.; Hahn, M.; Schmid, V.; Welz, C.; Schwenk-Zieger, S.; Stauber, R.; Baumeister, P.; Becker, S. Spheroid-Based 3D Cell Cultures Enable Personalized Therapy Testing and Drug Discovery in Head and Neck Cancer. Anticancer Res 2017, 37, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Lim, J.Y.; Cho, K.; Lee, H.W.; Park, J.Y.; Ro, S.W.; Kim, K.S.; Seo, H.R.; Kim, D.Y. Anti-Cancer Effects of YAP Inhibitor (CA3) in Combination with Sorafenib against Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) in Patient-Derived Multicellular Tumor Spheroid Models (MCTS). Cancers 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmer, J.; Struve, N.; Brüning-Richardson, A. Characterization of the Effects of Migrastatic Inhibitors on 3D Tumor Spheroid Invasion by High-Resolution Confocal Microscopy. JoVE 2019, No. 151, e60273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herter, S.; Morra, L.; Schlenker, R.; Sulcova, J.; Fahrni, L.; Waldhauer, I.; Lehmann, S.; Reisländer, T.; Agarkova, I.; Kelm, J.M.; Klein, C.; Umana, P.; Bacac, M. A Novel Three-Dimensional Heterotypic Spheroid Model for the Assessment of the Activity of Cancer Immunotherapy Agents. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 2017, 66, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.Y.; Yeap, S.K.; Ho, C.L.; Rahim, R.A.; Alitheen, N.B. Development of Multicellular Tumor Spheroid (MCTS) Culture from Breast Cancer Cell and a High Throughput Screening Method Using the MTT Assay. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e44640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.Y.; Liew, S.S.; Yeap, S.K.; Alitheen, N.B. Synergistic Cytotoxicity between Elephantopus Scaber and Tamoxifen on MCF-7-Derived Multicellular Tumor Spheroid. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2021, 2021, 6355236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.; Cohen-Harazi, R.; Maizels, Y.; Koman, I. Patient-Derived Tumor Spheroid Cultures as a Promising Tool to Assist Personalized Therapeutic Decisions in Breast Cancer. Translational Cancer Research; Vol 11, No 1 (January 26, 2022): Translational Cancer Research 2021.

- Hornung, A.; Poettler, M.; Friedrich, R.P.; Weigel, B.; Duerr, S.; Zaloga, J.; Cicha, I.; Alexiou, C.; Janko, C. Toxicity of Mitoxantrone-Loaded Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles in a HT-29 Tumour Spheroid Model. Anticancer Res 2016, 36, 3093. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Yu, P.; Tang, J. Characterization of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer MDA-MB-231 Cell Spheroid Model. Onco Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 5395–5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jove, M.; Spencer, J.A.; Hubbard, M.E.; Holden, E.C.; O’Dea, R.D.; Brook, B.S.; Phillips, R.M.; Smye, S.W.; Loadman, P.M.; Twelves, C.J. Cellular Uptake and Efflux of Palbociclib In Vitro in Single Cell and Spheroid Models. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2019, 370, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, F.N.; Kim, C.-H.; Lee, K.-H.; Kim, C.-D.; Lim, J.; Lee, T.; Park, C.G.; Kim, T.-H. Gold Nanostructure-Integrated Conductive Microwell Arrays for Uniform Cancer Spheroid Formation and Electrochemical Drug Screening. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2023, 222, 115003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamikamkar, S.; Behzadfar, E.; Cheung, K.C. A Novel Approach to Producing Uniform 3-D Tumor Spheroid Constructs Using Ultrasound Treatment. Biomedical Microdevices 2018, 20, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, H.; Fryknäs, M.; Larsson, R.; Nygren, P. Loss of Cancer Drug Activity in Colon Cancer HCT-116 Cells during Spheroid Formation in a New 3-D Spheroid Cell Culture System. Experimental Cell Research 2012, 318, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karshieva, S.S.; Glinskaya, E.G.; Dalina, A.A.; Akhlyustina, E.V.; Makarova, E.A.; Khesuani, Y.D.; Chmelyuk, N.S.; Abakumov, M.A.; Khochenkov, D.A.; Mironov, V.A.; Meerovich, G.A.; Kogan, E.A.; Koudan, E.V. Antitumor Activity of Photodynamic Therapy with Tetracationic Derivative of Synthetic Bacteriochlorin in Spheroid Culture of Liver and Colon Cancer Cells. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2022, 40, 103202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, E.E.; Sampaio, S.C. Crotoxin Modulates Events Involved in Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition in 3D Spheroid Model. Toxins 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-H.; Suhito, I.R.; Angeline, N.; Han, Y.; Son, H.; Luo, Z.; Kim, T.-H. Vertically Coated Graphene Oxide Micro-Well Arrays for Highly Efficient Cancer Spheroid Formation and Drug Screening. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2020, 9, 1901751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Ahn, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J.; Park, D.; Jeon, N.L. Tumor Spheroid-on-a-Chip: A Standardized Microfluidic Culture Platform for Investigating Tumor Angiogenesis. Lab Chip 2019, 19, 2822–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, S.J.; Close, D.A.; Johnston, P.A. High Content Screening Characterization of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Multicellular Tumor Spheroid Cultures Generated in 384-Well Ultra-Low Attachment Plates to Screen for Better Cancer Drug Leads. ASSAY and Drug Development Technologies 2019, 17, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochanek, S.J.; Close, D.A.; Camarco, D.P.; Johnston, P.A. Maximizing the Value of Cancer Drug Screening in Multicellular Tumor Spheroid Cultures: A Case Study in Five Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cell Lines. SLAS Discovery 2020, 25, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshkin, V.; Ailles, L.E.; Liu, G.; Krylov, S.N. Metabolic Suppression of a Drug-Resistant Subpopulation in Cancer Spheroid Cells. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 2016, 117, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroupová, J.; Hanuš, J.; Štěpánek, F. Surprising Efficacy Twist of Two Established Cytostatics Revealed by A-La-Carte 3D Cell Spheroid Preparation Protocol. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2022, 180, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudláčová, J.; Kotrchová, L.; Kostka, L.; Randárová, E.; Filipová, M.; Janoušková, O.; Fang, J.; Etrych, T. Structure-to-Efficacy Relationship of HPMA-Based Nanomedicines: The Tumor Spheroid Penetration Study. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Jain, S.; Ghosh, B.; Zorin, V.; Biswas, S. Polylactide-Based Block Copolymeric Micelles Loaded with Chlorin E6 for Photodynamic Therapy: In Vitro Evaluation in Monolayer and 3D Spheroid Models. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2017, 14, 3789–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal-Nag, M.; McGee, L.; Titus, S.A.; Brimacombe, K.; Michael, S.; Sittampalam, G.; Ferrer, M. Exploring Drug Dosing Regimens In Vitro Using Real-Time 3D Spheroid Tumor Growth Assays. SLAS Discovery 2017, 22, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama, R.; Zhang, L.; Naim, J.M.; Williams, J.; Zhou, A.; Su, B. Development, Validation and Pilot Screening of an in Vitro Multi-Cellular Three-Dimensional Cancer Spheroid Assay for Anti-Cancer Drug Testing. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2013, 21, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgraf, L.; Kozlowski, A.; Zhang, X.; Fournelle, M.; Becker, F.-J.; Tretbar, S.; Melzer, A. Focused Ultrasound Treatment of a Spheroid In Vitro Tumour Model. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.-M.; Lang, M.-D.; Shi, W.-B.; Liu, J.-W. A Collagen-Based Multicellular Tumor Spheroid Model for Evaluation of the Efficiency of Nanoparticle Drug Delivery. Artificial Cells, Nanomedicine, and Biotechnology 2016, 44, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Hong, S.; Jung, B.; Jeong, S.Y.; Byeon, J.H.; Jeong, G.S.; Choi, J.; Hwang, C. In Vitro Lung Cancer Multicellular Tumor Spheroid Formation Using a Microfluidic Device. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2019, 116, 3041–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lim, W.; Cho, H.; Park, S. High-Throughput Screening of Anti-Cancer Drugs Using a Microfluidic Spheroid Culture Device with a Concentration Gradient Generator. Current Protocols 2022, 2, e529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemmo, S.; Atefi, E.; Luker, G.D.; Tavana, H. Optimization of Aqueous Biphasic Tumor Spheroid Microtechnology for Anti-Cancer Drug Testing in 3D Culture. Cellular and Molecular Bioengineering 2014, 7, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lu, B.; Dong, X.; Zhou, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, T.; Bao, L. Enhancement of Cisplatin-Induced Cytotoxicity against Cervical Cancer Spheroid Cells by Targeting Long Non-Coding RNAs. Pathology - Research and Practice 2019, 215, 152653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.; Park, S. A Microfluidic Spheroid Culture Device with a Concentration Gradient Generator for High-Throughput Screening of Drug Efficacy. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.-T.; Gu, J.; Wang, H.; Wu, A.; Sun, J.; Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Kong, Y.; Wu, M.X.; Wu, T. Thermosensitive and Conductive Hybrid Polymer for Real-Time Monitoring of Spheroid Growth and Drug Responses. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 2147–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lin, H.; Song, J.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Zheng, C. A Novel SimpleDrop Chip for 3D Spheroid Formation and Anti-Cancer Drug Assay. Micromachines 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, C.; Frongia, C.; Jorand, R.; Fehrenbach, J.; Weiss, P.; Maandhui, A.; Gay, G.; Ducommun, B.; Lobjois, V. Live Cell Division Dynamics Monitoring in 3D Large Spheroid Tumor Models Using Light Sheet Microscopy. Cell Division 2011, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, Q.; Becker, J.H.; Macaraniag, C.; Massad, M.G.; Zhou, J.; Shimamura, T.; Papautsky, I. Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma Spheroid Models in Agarose Microwells for Drug Response Studies. Lab Chip 2022, 22, 2364–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, N.H.; Nielsen, B.S.; Nhat, S.L.; Skov, S.; Gad, M.; Larsen, J. Monocyte Infiltration and Differentiation in 3D Multicellular Spheroid Cancer Models. Pathogens 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.K.; Saelim, B.; Taweesap, M.; Pachana, V.; Panrak, Y.; Makchuchit, N.; Jaroenpakdee, P. Anti-EGFR Targeted Multifunctional I-131 Radio-Nanotherapeutic for Treating Osteosarcoma: In Vitro 3D Tumor Spheroid Model. Nanomaterials 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruhashi, R.; Akizuki, R.; Sato, T.; Matsunaga, T.; Endo, S.; Yamaguchi, M.; Yamazaki, Y.; Sakai, H.; Ikari, A. Elevation of Sensitivity to Anticancer Agents of Human Lung Adenocarcinoma A549 Cells by Knockdown of Claudin-2 Expression in Monolayer and Spheroid Culture Models. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2018, 1865, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnik, D.; Sahana, J.; Corydon, T.J.; Kopp, S.; Nassef, M.Z.; Wehland, M.; Infanger, M.; Grimm, D.; Krüger, M. Dexamethasone Inhibits Spheroid Formation of Thyroid Cancer Cells Exposed to Simulated Microgravity. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molyneaux, K.; Wnek, M.D.; Craig, S.E.L.; Vincent, J.; Rucker, I.; Wnek, G.E.; Brady-Kalnay, S.M. Physically-Cross-Linked Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Cell Culture Plate Coatings Facilitate Preservation of Cell–Cell Interactions, Spheroid Formation, and Stemness. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials 2021, 109, 1744–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monazzam, A.; Josephsson, R.; Blomqvist, C.; Carlsson, J.; Långström, B.; Bergström, M. Application of the Multicellular Tumour Spheroid Model to Screen PET Tracers for Analysis of Early Response of Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Research 2007, 9, R45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, T.; Takemura, Y.; Miura, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Kakizaki, F.; An, H.; Maekawa, H.; Yamaura, T.; Kawada, K.; Sakai, Y.; Yuba, Y.; Terajima, H.; Obama, K.; Taketo, M.M.; Miyoshi, H. Novel and Efficient Method for Culturing Patient-Derived Gastric Cancer Stem Cells. Cancer Science 2023, 114, 3259–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaad, E.O.; Chambers, K.F.; Futrega, K.; Clements, J.A.; Doran, M.R. The Microwell-Mesh: A High-Throughput 3D Prostate Cancer Spheroid and Drug-Testing Platform. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueggler, A.; Pilotto, E.; Perriraz-Mayer, N.; Jiang, S.; Addeo, A.; Bédat, B.; Karenovics, W.; Triponez, F.; Serre-Beinier, V. An Optimized Method to Culture Human Primary Lung Tumor Cell Spheroids. Cancers 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashimoto, Y.; Okada, R.; Hanada, S.; Arima, Y.; Nishiyama, K.; Miura, T.; Yokokawa, R. Vascularized Cancer on a Chip: The Effect of Perfusion on Growth and Drug Delivery of Tumor Spheroid. Biomaterials 2020, 229, 119547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigjeh, S.E.; Yeap, S.K.; Nordin, N.; Kamalideghan, B.; Ky, H.; Rosli, R. Citral Induced Apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 Spheroid Cells. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2018, 18, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittayaboon, K.; Leetanaporn, K.; Sangkhathat, S.; Roytrakul, S.; Navakanitworakul, R. Cytotoxic Effect of Metformin on Butyrate-Resistant PMF-K014 Colorectal Cancer Spheroid Cells. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 151, 113214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohya, S.; Kajikuri, J.; Endo, K.; Kito, H.; Matsui, M. KCa1.1 K+ Channel Inhibition Overcomes Resistance to Antiandrogens and Doxorubicin in a Human Prostate Cancer LNCaP Spheroid Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.S.; Aryasomayajula, B.; Pattni, B.; Mussi, S.V.; Ferreira, L.A.M.; Torchilin, V.P. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles Co-Loaded with Doxorubicin and α-Tocopherol Succinate Are Effective against Drug-Resistant Cancer Cells in Monolayer and 3-D Spheroid Cancer Cell Models. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2016, 512, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, K.; Sato, K.; Nakamura, T.; Yoshida, Y.; Murata, S.; Yoshida, K.; Kanemoto, H.; Umemori, K.; Kawai, H.; Obata, K.; Ryumon, S.; Hasegawa, K.; Kunisada, Y.; Okui, T.; Ibaragi, S.; Nagatsuka, H.; Sasaki, A. Reproduction of the Antitumor Effect of Cisplatin and Cetuximab Using a Three-Dimensional Spheroid Model in Oral Cancer. Int J Med Sci 2022, 19, 1320–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pampaloni, F.; Mayer, B.; Kabat Vel-Job, K.; Ansari, N.; Hötte, K.; Kögel, D.; Stelzer, E.H.K. A Novel Cellular Spheroid-Based Autophagy Screen Applying Live Fluorescence Microscopy Identifies Nonactin as a Strong Inducer of Autophagosomal Turnover. SLAS Discovery 2017, 22, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.C.; Jeong, H.; Son, S.H.; Kim, Y.; Han, D.; Goughnour, P.C.; Kang, T.; Kwon, N.H.; Moon, H.E.; Paek, S.H.; Hwang, D.; Seol, H.J.; Nam, D.-H.; Kim, S. Novel Morphologic and Genetic Analysis of Cancer Cells in a 3D Microenvironment Identifies STAT3 as a Regulator of Tumor Permeability Barrier Function. Cancer Research 2016, 76, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattni, B.S.; Nagelli, S.G.; Aryasomayajula, B.; Deshpande, P.P.; Kulkarni, A.; Hartner, W.C.; Thakur, G.; Degterev, A.; Torchilin, V.P. Targeting of Micelles and Liposomes Loaded with the Pro-Apoptotic Drug, NCL-240, into NCI/ADR-RES Cells in a 3D Spheroid Model. Pharmaceutical Research 2016, 33, 2540–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perche, F.; Patel, N.R.; Torchilin, V.P. Accumulation and Toxicity of Antibody-Targeted Doxorubicin-Loaded PEG–PE Micelles in Ovarian Cancer Cell Spheroid Model. Journal of Controlled Release 2012, 164, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, P.; Enciu, A.-M.; Tanase, C.; Dudau, M.; Albulescu, L.; Maxim, M.-E.; Darie-Niță, R.N.; Brincoveanu, O.; Avram, M. Assessing Polysaccharides/Aloe Vera–Based Hydrogels for Tumor Spheroid Formation. Gels 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulze, L.; Congiu, T.; Brevini, T.A.L.; Grimaldi, A.; Tettamanti, G.; D’Antona, P.; Baranzini, N.; Acquati, F.; Ferraro, F.; de Eguileor, M. MCF7 Spheroid Development: New Insight about Spatio/Temporal Arrangements of TNTs, Amyloid Fibrils, Cell Connections, and Cellular Bridges. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, S.; Mehta, P.; Horst, E.N.; Ward, M.R.; Rowley, K.R.; Mehta, G. Comparative Analysis of Tumor Spheroid Generation Techniques for Differential in Vitro Drug Toxicity. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavan, S.; Mehta, P.; Xie, Y.; Lei, Y.L.; Mehta, G. Ovarian Cancer Stem Cells and Macrophages Reciprocally Interact through the WNT Pathway to Promote Pro-Tumoral and Malignant Phenotypes in 3D Engineered Microenvironments. J Immunother Cancer 2019, 7, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, A.C.L.; Valadão, I.C.; Cardoso, E.C.; Martins, V.R.; Oliveira, L.M.S.; Bevilacqua, E.M.A.F.; Geraldo, M.V.; Jaeger, R.G.; Goldberg, G.S.; Freitas, V.M. Environmental Control of Mammary Carcinoma Cell Expansion by Acidification and Spheroid Formation in Vitro. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 21959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roering, P.; Siddiqui, A.; Heuser, V.D.; Potdar, S.; Mikkonen, P.; Oikkonen, J.; Li, Y.; Pikkusaari, S.; Wennerberg, K.; Hynninen, J.; Grenman, S.; Huhtinen, K.; Auranen, A.; Carpén, O.; Kaipio, K. Effects of Wee1 Inhibitor Adavosertib on Patient-Derived High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer Cells Are Multiple and Independent of Homologous Recombination Status. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudi, R.; Madjd, Z.; Ebrahimi, M.; Najafi, A.; Korourian, A.; Shariftabrizi, A.; Samadikuchaksaraei, A. Evidence for Embryonic Stem-like Signature and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Features in the Spheroid Cells Derived from Lung Adenocarcinoma. Tumor Biology 2016, 37, 11843–11859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouhani, M.; Goliaei, B.; Khodagholi, F.; Nikoofar, A. Lithium Increases Radiosensitivity by Abrogating DNA Repair in Breast Cancer Spheroid Culture. Arch Iran Med. 2014, 17, 352–360. [Google Scholar]

- Sakumoto, M.; Oyama, R.; Takahashi, M.; Takai, Y.; Kito, F.; Shiozawa, K.; Qiao, Z.; Endo, M.; Yoshida, A.; Kawai, A.; Kondo, T. Establishment and Proteomic Characterization of Patient-Derived Clear Cell Sarcoma Xenografts and Cell Lines. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology - Animal 2018, 54, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, F.; Jamali, T.; Kavoosi, G.; Ardestani, S.K.; Vahdati, S.N. Stabilization of Zataria Essential Oil with Pectin-Based Nanoemulsion for Enhanced Cytotoxicity in Monolayer and Spheroid Drug-Resistant Breast Cancer Cell Cultures and Deciphering Its Binding Mode with gDNA. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 164, 3645–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambi, M.; Samuel, V.; Qorri, B.; Haq, S.; Burov, S.V.; Markvicheva, E.; Harless, W.; Szewczuk, M.R. A Triple Combination of Metformin, Acetylsalicylic Acid, and Oseltamivir Phosphate Impacts Tumour Spheroid Viability and Upends Chemoresistance in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Drug Des Devel Ther 2020, 14, 1995–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, S.; Mehta, V.; Ravi, S.; Sharma, C.S.; Rath, S.N. A Novel Design of Microfluidic Platform for Metronomic Combinatorial Chemotherapy Drug Screening Based on 3D Tumor Spheroid Model. Biomedical Microdevices 2021, 23, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Särchen, V.; Shanmugalingam, S.; Kehr, S.; Reindl, L.M.; Greze, V.; Wiedemann, S.; Boedicker, C.; Jacob, M.; Bankov, K.; Becker, N.; Wehner, S.; Theilen, T.M.; Gretser, S.; Gradhand, E.; Kummerow, C.; Ullrich, E.; Vogler, M. Pediatric Multicellular Tumor Spheroid Models Illustrate a Therapeutic Potential by Combining BH3 Mimetics with Natural Killer (NK) Cell-Based Immunotherapy. Cell Death Discovery 2022, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıyar, E.; Karpat, O.; Sezan, S.; Baylan, S.M.; Kıpçak, A.; Guven, K.; Erdal, E.; Fırtına Karagonlar, Z. EGFR and Lyn Inhibition Augments Regorafenib Induced Cell Death in Sorafenib Resistant 3D Tumor Spheroid Model. Cellular Signalling 2023, 105, 110608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauer, S.J.; Tarpley, M.; Shah, I.; Save, A.V.; Lyerly, H.K.; Patierno, S.R.; Williams, K.P.; Devi, G.R. Bisphenol A Activates EGFR and ERK Promoting Proliferation, Tumor Spheroid Formation and Resistance to EGFR Pathway Inhibition in Estrogen Receptor-Negative Inflammatory Breast Cancer Cells. Carcinogenesis 2017, 38, bgx003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.; Ahmed, M.; Lorenzi, F.; Nateri, A.S. Spheroid-Formation (Colonosphere) Assay for in Vitro Assessment and Expansion of Stem Cells in Colon Cancer. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports 2016, 12, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, K.; Lee, J.; Yarmush, M.L.; Parekkadan, B. Microcavity Substrates Casted from Self-Assembled Microsphere Monolayers for Spheroid Cell Culture. Biomedical Microdevices 2014, 16, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheth, D.B.; Gratzl, M. Electrochemical Mapping of Oxygenation in the Three-Dimensional Multicellular Tumour Hemi-Spheroid. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2019, 475, 20180647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortt, R.L.; Wang, Y.; Hummon, A.B.; Jones, L.M. Development of Spheroid-FPOP: An In-Cell Protein Footprinting Method for 3D Tumor Spheroids. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2023, 34, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Tayalia, P. Three-Dimensional Cryogel Matrix for Spheroid Formation and Anti-Cancer Drug Screening. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2020, 108, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhito, I.R.; Angeline, N.; Lee, K.-H.; Kim, H.; Park, C.G.; Luo, Z.; Kim, T.-H. A Spheroid-Forming Hybrid Gold Nanostructure Platform That Electrochemically Detects Anticancer Effects of Curcumin in a Multicellular Brain Cancer Model. Small 2021, 17, 2002436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanenbaum, L.M.; Mantzavinou, A.; Subramanyam, K.S.; del Carmen, M.G.; Cima, M.J. Ovarian Cancer Spheroid Shrinkage Following Continuous Exposure to Cisplatin Is a Function of Spheroid Diameter. Gynecologic Oncology 2017, 146, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Hu, K.; Sun, J.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Liu, M.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, F.; Gu, N. High Quality Multicellular Tumor Spheroid Induction Platform Based on Anisotropic Magnetic Hydrogel. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 10446–10452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taubenberger, A.V.; Girardo, S.; Träber, N.; Fischer-Friedrich, E.; Kräter, M.; Wagner, K.; Kurth, T.; Richter, I.; Haller, B.; Binner, M.; Hahn, D.; Freudenberg, U.; Werner, C.; Guck, J. 3D Microenvironment Stiffness Regulates Tumor Spheroid Growth and Mechanics via P21 and ROCK. Advanced Biosystems 2019, 3, 1900128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrones, M.; Deben, C.; Rodrigues-Fortes, F.; Schepers, A.; de Beeck, K.O.; Van Camp, G.; Vandeweyer, G. CRISPR/Cas9-Edited ROS1 + Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cell Lines Highlight Differential Drug Sensitivity in 2D vs 3D Cultures While Reflecting Established Resistance Profiles. Journal of Translational Medicine 2024, 22, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tevis, K.M.; Cecchi, R.J.; Colson, Y.L.; Grinstaff, M.W. Mimicking the Tumor Microenvironment to Regulate Macrophage Phenotype and Assessing Chemotherapeutic Efficacy in Embedded Cancer Cell/Macrophage Spheroid Models. Acta Biomaterialia 2017, 50, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To, H.T.; Le, Q.A.; Bui, H.T.; Park, J.-H.; Kang, D. Modulation of Spheroid Forming Capacity and TRAIL Sensitivity by KLF4 and Nanog in Gastric Cancer Cells. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2023, 45, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torisawa, Y.; Takagi, A.; Nashimoto, Y.; Yasukawa, T.; Shiku, H.; Matsue, T. A Multicellular Spheroid Array to Realize Spheroid Formation, Culture, and Viability Assay on a Chip. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uematsu, N.; Zhao, Y.; Kiyomi, A.; Yuan, B.; Onda, K.; Tanaka, S.; Sugiyama, K.; Sugiura, M.; Takagi, N.; Hayakawa, A.; Hirano, T. Chemo-Sensitivity of Two-Dimensional Monolayer and Three-Dimensional Spheroid of Breast Cancer MCF-7 Cells to Daunorubicin, Docetaxel, and Arsenic Disulfide. Anticancer Res 2018, 38, 2101. [Google Scholar]

- Varan, G.; Akkın, S.; Demirtürk, N.; Benito, J.M.; Bilensoy, E. Erlotinib Entrapped in Cholesterol-Depleting Cyclodextrin Nanoparticles Shows Improved Antitumoral Efficacy in 3D Spheroid Tumors of the Lung and the Liver. Journal of Drug Targeting 2021, 29, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, M.; Gowan, S.; Boxall, F.; Patterson, L.; Zimmermann, M.; Court, W.; Lomas, C.; Mendiola, M.; Hardisson, D.; Eccles, S.A. Advances in Establishment and Analysis of Three-Dimensional Tumor Spheroid-Based Functional Assays for Target Validation and Drug Evaluation. BMC Biology 2012, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Li, Z.; Ye, H.; Cui, Z. Three-Dimensional Perfused Tumour Spheroid Model for Anti-Cancer Drug Screening. Biotechnology Letters 2016, 38, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J. Mixed Hydrogel Bead-Based Tumor Spheroid Formation and Anticancer Drug Testing. Analyst 2014, 139, 2449–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, M.J.; Keshishian, V.; Law, J.J.; Ho, J.C.; Favela, C.A.; Rees, P.; Smith, B.; Mohammad, S.; Hwang, R.F.; Rajapakshe, K.; Coarfa, C.; Huang, S.; Edwards, D.P.; Corr, S.J.; Godin, B.; Curley, S.A. Generation of an in Vitro 3D PDAC Stroma Rich Spheroid Model. Biomaterials 2016, 108, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Z.; Liao, Q.; Hu, Y.; You, L.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, Y. A Spheroid-Based 3-D Culture Model for Pancreatic Cancer Drug Testing, Using the Acid Phosphatase Assay. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2013, 46, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzel, C.; Riefke, B.; Gründemann, S.; Krebs, A.; Christian, S.; Prinz, F.; Osterland, M.; Golfier, S.; Räse, S.; Ansari, N.; Esner, M.; Bickle, M.; Pampaloni, F.; Mattheyer, C.; Stelzer, E.H.; Parczyk, K.; Prechtl, S.; Steigemann, P. 3D High-Content Screening for the Identification of Compounds That Target Cells in Dormant Tumor Spheroid Regions. Experimental Cell Research 2014, 323, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weydert, Z.; Lal-Nag, M.; Mathews-Greiner, L.; Thiel, C.; Cordes, H.; Küpfer, L.; Guye, P.; Kelm, J.M.; Ferrer, M. A 3D Heterotypic Multicellular Tumor Spheroid Assay Platform to Discriminate Drug Effects on Stroma versus Cancer Cells. SLAS Discovery 2020, 25, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Zhan, S.; Rui, C.; Sho, E.; Shi, X.; Ding, Y. Microporous Cellulosic Scaffold as a Spheroid Culture System Modulates Chemotherapeutic Responses and Stemness in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 5244–5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.-W.; Kuo, C.-T.; Tu, T.-Y. A Highly Reproducible Micro U-Well Array Plate Facilitating High-Throughput Tumor Spheroid Culture and Drug Assessment. Global Challenges 2021, 5, 2000056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Avci, N.G.; Akay, Y.; Esquenazi, Y.; Schmitt, L.H.; Tandon, N.; Zhu, J.J.; Akay, M. Temozolomide in Combination With NF-κB Inhibitor Significantly Disrupts the Glioblastoma Multiforme Spheroid Formation. IEEE Open Journal of Engineering in Medicine and Biology 2020, 1, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Liu, T.; Ying, Y.; Yu, X.; Wang, Z.; Gao, H.; Lin, T.; Fan, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Q.; Ge, Y.; Zeng, S.; Xu, C. Establishment of Bladder Cancer Spheroids and Cultured in Microfluidic Platform for Predicting Drug Response. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine 2024, 9, e10624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamawaki, K.; Mori, Y.; Sakai, H.; Kanda, Y.; Shiokawa, D.; Ueda, H.; Ishiguro, T.; Yoshihara, K.; Nagasaka, K.; Onda, T.; Kato, T.; Kondo, T.; Enomoto, T.; Okamoto, K. Integrative Analyses of Gene Expression and Chemosensitivity of Patient-Derived Ovarian Cancer Spheroids Link G6PD-Driven Redox Metabolism to Cisplatin Chemoresistance. Cancer Letters 2021, 521, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Sopko, N.A.; Kates, M.; Liu, X.; Joice, G.; Mcconkey, D.J.; Bivalacqua, T.J. Impact of Spheroid Culture on Molecular and Functional Characteristics of Bladder Cancer Cell Lines. Oncol Lett 2019, 18, 4923–4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Ni, C.; Grist, S.M.; Bayly, C.; Cheung, K.C. Alginate Core-Shell Beads for Simplified Three-Dimensional Tumor Spheroid Culture and Drug Screening. Biomedical Microdevices 2015, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Roberts, M.G.; Houdaihed, L.; Liu, Y.; Ho, K.; Walker, G.; Allen, C.; Reilly, R.M.; Manners, I.; Winnik, M.A. Investigating the Influence of Block Copolymer Micelle Length on Cellular Uptake and Penetration in a Multicellular Tumor Spheroid Model. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.Z.; Bryce, N.S.; Lanzirotti, A.; Chen, C.K.J.; Paterson, D.; de Jonge, M.D.; Howard, D.L.; Hambley, T.W. Getting to the Core of Platinum Drug Bio-Distributions: The Penetration of Anti-Cancer Platinum Complexes into Spheroid Tumour Models. Metallomics 2012, 4, 1209–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Z.; Bryce, N.S.; Siegele, R.; Carter, E.A.; Paterson, D.; de Jonge, M.D.; Howard, D.L.; Ryan, C.G.; Hambley, T.W. The Use of Spectroscopic Imaging and Mapping Techniques in the Characterisation and Study of DLD-1 Cell Spheroid Tumour Models. Integr. Biol. 2012, 4, 1072–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Yu, W.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, X. Development of an in Vitro Multicellular Tumor Spheroid Model Using Microencapsulation and Its Application in Anticancer Drug Screening and Testing. Biotechnology Progress 2005, 21, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuchowska, A.; Kwapiszewska, K.; Chudy, M.; Dybko, A.; Brzozka, Z. Studies of Anticancer Drug Cytotoxicity Based on Long-Term HepG2 Spheroid Culture in a Microfluidic System. ELECTROPHORESIS 2017, 38, 1206–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2D models | 3D models | |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages |

|

|

| Limitations |

|

|

| Potentials |

|

|

| Reference | Cancer primary site (histological type) | Cell line | Spheroid formation method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agastin S, 2011 [17] | Colon (adenocarcinoma), Breast (adenocarcinoma) | Colo205, MDA-MB-231 | Hanging drop |

| Alhasan L, 2016 [18] | Breast (carcinoma) | BT-474 | Scaffold-based methods |

| An HJ, 2020 [19] | Kidney (carcinoma) | A498 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Árnadóttir SS, 2018 [20] | Colon | Patient-derived | Forced-floating (not defined) |

| Baek N, 2016 [21] | Prostate (carcinoma), Bone (neuroblastoma), Lung (carcinoma), Cervix (adenocarcinoma), Bone (osteosarcoma) | DU145, SH-SY5Y, A549, HeLa, HEp2, 0U-2OS | Forced-floating (agar coated plates) |

| Barone RM, 1981 [22] | Colon (adenocarcinoma) | HT-29 | Suspension culture |

| Bartholomä P, 2005 [23] | Breast (carcinoma) | T-47D | Suspension culture |

| Boo L, 2020 [24] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Forced-floating (agar coated plates) |

| Brooks EA, 2019 [25] | Ovary (adenocarcinoma) | Patient-derived, AU565, BT549, SKOV-3 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Bruns J, 2022 [26] | Brain (glioblastoma) | Patient-derived, U87 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Calori IR, 2022 [27] | Brain (glioblastoma, medulloblastoma) | U87, T98G, A172, UW473 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Chang S, 2022 [28] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Recent advances |

| Chen G, 2022 [29] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Chen MC, 2010 [30] | Breast (melanoma) | LCC6/Her-2 | Recent advances |

| Chen Z, 2021 [31] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MDA-MB-231 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Cheng V, 2015 [32] | Brain (glioblastoma) | U87, U251 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Close DA, 2022 [33] | Oral (squamous cell carcinoma) | Cal33, FaDu, UM-22B, OSC-19 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Das T, 2013 [34] | Ovary (adenocarcinoma) | TOV112D | Hanging drop |

| Das V, 2016 [35] | Colon (carcinoma), Colon (adenocarcinoma), Bone (osteosarcoma), Cervix (adenocarcinoma), Colon (adenocarcinoma), Liver (carcinoma) | HCT116, HT29, U-2OS, HeLa, Caco-2, HepG2 | Forced-floating (liquid overlay) |

| Das V, 2017 [36] | Colon (carcinoma) | HCT116 | Forced-floating (liquid overlay) |

| De Angelis ML, 2018 [37] | Colon | Patient-derived | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Dhamecha D, 2021 [38] | Lung (carcinoma), Bone (osteosarcoma) | A549, MG-63 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Dias DR, 2016 [39] | Cervix (adenocarcinoma) | HeLa | Recent advances |

| Domenici G, 2021 [40] | Bone (sarcoma) | Patient-derived | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Dufau I, 2012 [41] | Pancreas (adenocarcinoma) | Capan-2 | Forced-floating (poly-HEMA) |

| Eetezadi S, 2018 [42] | Ovary (carcinoma), Ovary (adenocarcinoma) | UWB1.289, UWB1.289+BRCA1, OV-90, SKOV3, PEO1, PEO4, COV362 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Eguchi H, 2022 [43] | Lung (carcinoma) | A549 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Eimer S, 2012 [44] | Brain (glioblastoma) | Patient-derived | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| El-Sadek IA, 2021 [45] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Enmon RM Jr, 2001 [46] | Prostate (carcinoma) | DU 145 | Forced-floating (agar plates) |

| Flørenes VA, 2019 [47] | Skin (Melanoma) | Patient-derived | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Fu J, 2020 [48] | Liver (carcinoma), Prostate (carcinoma), Lung (carcinoma), Breast (adenocarcinoma) | HepG2, DU 145, A549, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Fu JJ, 2018 [49] | Prostate (carcinoma) | DU 145, LNCap | Scaffold-based methods |

| Gao Y, 2022 [50] | Lung (carcinoma) | A549 | Recent advances |

| Gencoglu MF, 2018 [51] | Breast (adenocarcinoma), Breast (carcinoma), Prostate (carcinoma), Prostate (adenocarcinoma), Ovary (adenocarcinoma) | AU565, BT549, BT474, HCC 1419, HCC 1428, HCC 1806, HCC 1954, HCC 202, HCC 38, ZR75 1, HCC 70, LNCaPcol, PC3, SKOV3 | Scaffold-based methods, Microwells, Suspension culture |

| Gendre DAJ, 2021 [52] | Lung (mesothelioma), Lung (adenocarcinoma) | H2052, H2052/484, H2452, LuCa1, LuCa61, LuCa62 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Gheytanchi E, 2021 [53] | Colon (adenocarcinoma) | HT-29, Caco-2 | Hanging drop, Forced-floating (Poly-HEMA) |

| Goisnard A, 2021 [54] | Breast (carcinoma), Breast (adenocarcinoma) | SUM1315, MDA-MB-231, HCC1937, SW527, DU4475 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Guo X, 2019 [55] | Ovary (adenocarcinoma), Colon (adenocarcinoma), Pancreas (carcinoma), Prostate (adenocarcinoma) | OVCAR3, SW620, PANC-1, PC3 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Hagemann J, 2017 [56] | Oral (carcinoma) | FaDu, Cal27, UPCI-SCC-154 | Forced-floating (ULA), Hanging drop |

| Han S, 2022 [57] | Liver | Patient-derived | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Harmer J, 2019 [58] | Brain (glioblastoma) | U251, KNS42 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Herter S, 2017 [59] | Colon (adenocarcinoma) | LS174T, LoVo | Hanging drop |

| Ho WY, 2012 [60] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Forced-floating (liquid overlay) |

| Ho WY, 2021 [61] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Hofmann S, 2022 [62] | Breast | Patient-derived | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Hornung A, 2016 [63] | Colon (adenocarcinoma) | HT-29 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Huang Z, 2020 [64] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MDA-MB-231 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Jove M, 2019 [65] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) Colorectal (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7, DLD-1 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Ju FN, 2023 [66] | Brain (glioblastoma) | U87 | Recent advances |

| Karamikamkar S, 2018 [67] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Karlsson H, 2012 [68] | Colon (carcinoma) | HCT-116 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Karshieva SS, 2022 [69] | Colon (carcinoma), Liver (carcinoma) | HCT-116, Huh7 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Kato EE, 2021 [70] | Lung (carcinoma) | A549 | Hanging drop |

| Kim CH, 2020 [71] | Liver (carcinoma) | HepG2 | Recent advances |

| Ko J, 2019 [72] | Brain (glioblastoma) | U87 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Kochanek SJ, 2019 [73] | Oral (carcinoma) | Cal33, Cal27, FaDu, UM-22B, BICR56, OSC-19, PCI-13, PCI-52, Detroit-562, UM-SCC-1, and SCC-9 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Kochanek SJ, 2020 [74] | Oral (carcinoma) | Cal33, FaDu, UM-22B, BICR56, OSC-19 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Koshkin V, 2016 [75] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Kroupová J, 2022 [76] | Colon (adenocarcinoma) | HT-29 | Forced-floating (not defined) |

| Kudláčová J, 2020 [77] | Brain (glioblastoma) | U87 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Kumari P, 2017 [78] | Cervix (adenocarcinoma), Lung (carcinoma) | HeLa, A549 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Lal-Nag M, 2017 [79] | Ovary (adenocarcinoma) | Hey-A8–GFP | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Lama R, 2013 [80] | Lung (carcinoma) | H292 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Landgraf L, 2022 [81] | Prostate (adenocarcinoma), Brain (glioblastoma) | PC-3, U87 | Forced-floating (liquid overlay) |

| Le VM, 2016 [82] | Lung (carcinoma), Colon (carcinoma), Brain (glioblastoma) | 95-D, HCT-116, U87 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Lee SW, 2019 [83] | Lung (carcinoma) | A549 | Recent advances |

| Lee Y, 2022 [84] | Lung (carcinoma) | H460, A549 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Lemmo S, 2014 [85] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MDA-MB-231 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Li M, 2019 [86] | Cervix (carcinoma) | C-33-A, DoTC2 4510 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Lim W, 2018 [87] | Colon (carcinoma), Brain (glioblastoma) | HCT-116, U87 | Recent advances |

| Lin ZT, 2021 [88] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MDA-MB-436 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Liu X, 2021 [89] | Sarcoma | HS-SY-II | Recent advances |

| Lorenzo C, 2011 [90] | Pancreas (adenocarcinoma) | Capan-2 | Forced-floating (poly-HEMA) |

| Luan Q, 2022 [91] | Lung (adenocarcinoma), Lung (carcinoma) | HCC4006, H1975, A549 | Scaffold-based methods, Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Madsen NH, 2021 [92] | Breast (adenocarcinoma), Colon (adenocarcinoma), Pancreas (carcinoma) | MCF-7, HT-29, PANC-1, MIA PaCa-2 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Marshall SK, 2022 [93] | Bone (osteosarcoma) | MG-63 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Maruhashi R, 2018 [94] | Lung (carcinoma) | A549 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Melnik D, 2020 [95] | Thyroid (carcinoma) | FTC-133 | Suspension culture |

| Molyneaux K, 2021 [96] | Brain (glioblastoma) | LN229, U87, Gli36 | Forced-floating (not defined) |

| Monazzam A, 2007 [97] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Forced-floating (agar plates) |

| Morimoto T, 2023 [98] | Gastric | Patient-derived | Scaffold-based methods |

| Mosaad EO, 2018 [99] | Prostate (cancer), Prostate (carcinoma) | C42B, LNCaP | Recent advances |

| Mueggler A, 2023 [100] | Lung | Patient-derived | Scaffold-based methods |

| Nashimoto Y, 2020 [101] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Recent advances |

| Nigjeh SE, 2018 [102] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MDA-MB-231 | Forced-floating (agar plates), Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Nittayaboon K, 2022 [103] | Colon (carcinoma) | PMF-k014 | Forced-floating (poly-HEMA) |

| Ohya S, 2021 [104] | Prostate (carcinoma) | LNCaP | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Oliveira MS, 2016 [105] | Breast (adenocarcinoma), Ovary (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7/Adr, NCI/Adr | Forced-floating (liquid overlay) |

| Ono K, 2022 [106] | Oral (carcinoma) | SAS, HSC-3, HSC-4, OSC-19 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Pampaloni F, 2017 [107] | Brain (glioblastoma) | U343 | Forced-floating (liquid overlay) |

| Park MC, 2016 [108] | Brain (glioblastoma) | Patient-derived and PC14PE6, PC14PE6_LvBr3, D54, LN428, LN751, U251E4, U87E4, SN-12C, SNU-119, SNU-216, SNU-668, SNU-719, HCC1171, HCC1195, HCC15, HCC1588, HCC2108, HCC44 | Forced-floating (not defined) |

| Pattni BS, 2016 [109] | Ovary (adenocarcinoma) | NCI/ADR-RES | Forced-floating (liquid overlay) |

| Perche F, 2012 [110] | Ovary (adenocarcinoma) | NCI/ADR-RES | Forced-floating (liquid overlay) |

| Preda P, 2023 [111] | Breast (adenocarcinoma), Brain (glioblastoma) | MDA-MB-231, U87 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Pulze L, 2020 [112] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Raghavan S, 2016 [113] | Breast (adenocarcinoma), Ovary (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7, OVCAR8 | Hanging drop, Forced-floating (liquid overlay) |

| Raghavan S, 2019 [114] | Ovary (adenocarcinoma) | A2780, OVCAR3 | Hanging drop |

| Ralph ACL, 2020 [115] | Breast (adenocarcinoma), Breast (carcinoma) | MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, T47D | Hanging drop |

| Roering P, 2022 [116] | Ovary (adenocarcinoma) | Patient-derived, CAOV3, OVCAR8 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Roudi R, 2016 [117] | Lung (carcinoma) | A549 | Forced-floating (poly-HEMA) |

| Rouhani M, 2014 [118] | Breast (carcinoma) | T47D | Forced-floating (liquid overlay) |

| Sakumoto M, 2018 [119] | Sarcoma | Patient-derived | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Salehi F, 2020 [120] | Breast (adenocarcinoma), Breast (carcinoma) | MDA-MB-231, T47D, MCF-7 | Forced-floating (liquid overlay), Hanging drop |

| Sambi M, 2020 [121] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MDA-MB-231 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Sankar S, 2021 [122] | Lung (carcinoma) | A549 | Recent advances |

| Särchen V, 2022 [123] | Sarcoma | RH30 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Sarıyar E, 2023 [124] | Liver (carcinoma) | Huh7 | Hanging drop |

| Sauer SJ, 2017 [125] | Breast (carcinoma), Breast (adenocarcinoma) | SUM149, SUM190, T47D, MCF-7 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Shaheen S, 2016 [126] | Colon (carcinoma) | HCT-116 | Forced-floating (not defined) |

| Shen K, 2014 [127] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MDA-MB-231 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Sheth DB, 2019 [128] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Recent advances |

| Shortt RL, 2023 [129] | Colon (carcinoma) | HCT-116 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Singh A, 2020 [130] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Suhito IR, 2021 [131] | Bone (neuroblastoma), Brain (glioblastoma) | SH-SY5Y, U-87 | Recent advances |

| Tanenbaum LM, 2017 [132] | Ovary (adenocarcinoma) | UCI101, A2780 | Forced-floating (not defined) |

| Tang S, 2017 [133] | Colon (adenocarcinoma), Ovary (adenocarcinoma) | HT-29, SKOV-3 | Hanging drop |

| Taubenberger AV, 2019 [134] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Terrones M, 2024 [135] | Lung (adenocarcinoma) | HCC78 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Tevis KM, 2017 [136] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MDA-MB-231 | Scaffold-based methods |

| To HTN, 2022 [137] | Stomach (carcinoma) | SNU-216, SNU-484, SNU-601, SNU-638, SNU-668, and SNU-719 | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Torisawa YS, 2007 [138] | Breast (adenocarcinoma), Liver (carcinoma) | MCF-7, HepG2 | Recent advances |

| Uematsu N, 2018 [139] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Recent advances |

| Varan G, 2021 [140] | Lung (carcinoma), Liver (carcinoma) | A549, HepG2 | Forced-floating (poly-HEMA) |

| Vinci M, 2012 [141] | Brain (glioblastoma), Oral (carcinoma), Breast (adenocarcinoma) | U87, KNS42, LICR-LON-HN4, MDA-MB-231 | Forced-floating (ULA), Agarose plates |

| Wan X, 2016 [142] | Colon (adenocarcinoma), Ovary (adenocarcinoma) | DLD-1, NCI/ADR | Scaffold-based methods |

| Wang Y, 2014 [143] | Cervix (adenocarcinoma) | HeLa | Scaffold-based methods |

| Ware MJ, 2016 [144] | Pancreas (carcinoma) | PANC-1, AsPc-1, BxPC-3, Capan-1, MIA PaCa-2 cells | Hanging drop |

| Wen Z, 2013 [145] | Pancreas (carcinoma) | MIAPaCa-2, PANC-1 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Wenzel C, 2014 [146] | Breast (carcinoma) | T47D | Forced-floating (liquid overlay) |

| Weydert Z, 2020 [147] | Ovary (adenocarcinoma) | HEY, SKOV-3 | Hanging drop |

| Wu G, 2019 [148] | Liver (carcinoma) | HepG2, Huh7 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Wu KW, 2020 [149] | Bladder (carcinoma), Lung (carcinoma), Liver (carcinoma) | T24, A549, Huh-7 | Recent advances |

| Xia H, 2020 [150] | Brain (glioblastoma) | LN229, U87 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Xiong Q, 2023 [151] | Bladder | Patient-derived | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Yamawaki K, 2021 [152] | Ovary | Patient-derived | Forced-floating (ULA) |

| Yoshida T, 2019 [153] | Bladder | Patient-derived | Scaffold-based methods |

| Yu L, 2015 [154] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Recent advances |

| Yu Q, 2021 [155] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MDA-MB-436, MDB-MB-231 | Scaffold-based methods |

| Zhang JZ, 2012 [156] | Colon (adenocarcinoma), Ovary (teratocarcinoma) | DLD-1, PA-1 ovarian cancer cells | Forced-floating (liquid overlay) |

| Zhang JZ, 2012 [157] | Colon (adenocarcinoma) | DLD-1 | Forced-floating (liquid overlay) |

| Zhang X, 2005 [158] | Breast (adenocarcinoma) | MCF-7 | Recent advances |

| Zuchowska A, 2017 [159] | Liver (carcinoma) | HepG2 | Recent advances |

| Spheroid formation method | Number of studies | Percentage of total number of studies |

|---|---|---|

| Forced-floating | 70 | 31.8% |

| Scaffold-based | 41 | 18.6% |

| Recent advances | 21 | 9.5% |

| Hanging drop | 14 | 6.4% |

| Suspension culture | 4 | 1.8% |

| Magnetic levitation | 0 | 0.0% |

| Spheroid formation method | Number of studies | Percentage of total number of studies |

|---|---|---|

| Forced-floating | 70 | 31.8% |

| Scaffold-based | 41 | 18.6% |

| Recent advances | 21 | 9.5% |

| Hanging drop | 14 | 6.4% |

| Suspension culture | 4 | 1.8% |

| Magnetic levitation | 0 | 0.0% |

| Method | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Forced floating method |

|

|

| Scaffold-based |

|

|

| Hanging drop method |

|

|

| Suspension culture |

|

|

| Microencapsulation |

|

|

| Bioprinting |

|

|

| Nanoparticle-assisted techniques |

|

|

| Microfluidics and lab-on-a-chip |

|

|

| Magnetic levitation |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).