1. Introduction

Excessive drinking can lead to many adverse physical symptoms, such as headaches, dizziness, and lightheadedness [

1,

2,

3]. In severe cases, it may even endanger the life and safety of oneself and others [

4]. When the amount of alcohol intake exceeds the body’s metabolic capacity, the alcohol concentration in the blood rises, and the alcohol enters the brain through the blood circulation, resulting in drunkenness [

5]. Beyond that, high levels of alcohol in the body disorders cellular function and antioxidant system. Alcohol metabolism in the body produces inflammatory mediators and cytokines, which may induce liver cell injury [

6].

Once alcohol is absorbed by the digestive system in body, it is transported to the liver through the blood circulation and oxidized into a toxic metabolite, acetaldehyde, mainly through the alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) in the liver cells [

7]. Acetaldehyde is then metabolized by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) to relatively non-toxic acetate [

8], which is finally converted to CO

2 and water and exhaled through the respiratory system or excreted in the urine [

9]. Although metabolites produced during alcohol metabolism may affect hangovers and liver dysfunction, natural products or functional foods that can initiate or promote alcohol metabolism should be able to alleviate hangovers and ultimately reduce liver damage [

10]. Under certain conditions, cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) is involved in the metabolism of alcohol. During the metabolic process, reactive oxygen species (ROS) was generated, which reduces the GSH content and increases lipid peroxidation in the liver [

11]. Therefore, long-term drinking is one of the main causes of oxidative stress in the body, which not only stimulates the production of ROS, but also disorders the homeostasis of the redox system [

12]. Therefore, if food products or ingredients possess the ability to promote alcohol metabolism, inhibit inflammatory substances, and enhance antioxidant enzyme activity, they may have the potential to improve alcohol metabolism, liver damage, and even drunkenness.

Freshwater clams (

Corbicula fluminea), also called the golden clams and Asiatic clams, are extensively grown in muddy bottoms of rivers, ponds, and lakes in freshwater or brackish water ecosystems (close to river mouths) of Asian countries [

13]. They are suitable for artificial breeding due to their fast growth and high reproductive capacity. However, freshwater clams are quite sensitive to water quality, so farm with clear and clean water for cultivation is required. As several studies have shown that freshwater clams contain high levels of nutrients and perform the effects of regulating blood lipids, protecting the liver, inhibiting cancer growth, and improving gastric ulcer [

14,

15,

16,

17], they have been developed into diverse health foods in the current market. Furthermore, the Compendium of Materia Medica (Bencao Gangmu) in Chinese also recorded that clams have medicinal effects on the metabolism of alcohol-induced toxicity. In the present study, we used freshwater clam aqueous extract (CE) as experimental material to explore its effects on blood ethanol content in rats fed with single dose of alcohol and to further elucidate its potent mechanism.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Ethanol Assay Kit was provided by Abnova (Taipei, Taiwan). Alcohol Dehydrogenase Activity Colorimetric Assay Kit and Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Activity Colorimetric Assay Kit were obtained from BioVision (Milpitas, CA, USA).Superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) assay kits were provided by Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The COX-2 antibody was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). The iNOS and TNF-α antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The β-actin antibody, RIPA lysis buffer, ammonium persulfate (NH4)2S2O8), and secondary antibody were purchased from Merck Millipore (Burlington, MA, USA). GE Healthcare AmershamTM ECL prime western blotting detection reagent, Cytiva Amersham™ Hybond™ PVDF membrane, and Coomassie assay protein reagent were obtained from Thermo-Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Sodiumdodecyl sulfate (SDS), ethanol, methanol and all other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Experimetal Material Preparation

The freshwater clam aqueous extract (CE) was a gift from Li Chuan Aquafarm Co., Ltd. (Hualien, Taiwan), which was prepared following the procedure previously published by Isnain et al. [

17]. Briefly, ddH

2O was used to extract dried freshwater clam meat powder at a ratio of 1:20 (w/v) for 24 h, and then the filtrate was obtained after centrifugation and filtration. The filtrate was dried with a lyophilizer after freezing to obtain CE, which was then kept at -20°C and orally administered to rats after being resuspended in ddH

2O.

2.3. Animals and Treatment

Five-week-old Wistar male rats were purchased from BioLASCO Co., Ltd. (Taipei, Taiwan) and housed in the animal room of National Pingtung University of Science and Technology. The environment was controlled under 12-h light/dark cycle, room temperature was maintained at 22 ± 2°C, and relative humidity was 60-80%. The animals were allowed to have diet and water freely. After the rats were stably raised for 1 week, they were divided into four groups (6 rats in each group): (1) Control group (C); (2) Vehicle group (V), which was given a single dose of 2 g/kg bw ethanol; (3) Low-dose CE group (CEL), which was given ethanol and 128 mg/ kg bw CE; (4) High-dose CE group (CEH), which was given ethanol and 256 mg/ kg bw CE. On the day of the experiment, the vehicle (ddH2O) and CE were administered to rats (fasting overnight) by gavage 20 min after the ethanol treatment. Serum was collected from the tail artery at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 h after ethanol treatment. At the end of the experiment, all animals were sacrificed and their blood and liver tissues were collected. All animal studies were conducted under the animal use protocol (NPUST-105-024) approved by the IUCUC of National Pingtung University of Science and Technology.

2.4. Measurement of Serum Ethanol Concentration

The ethanol concentration of serum samples from rats was analyzed using the Ethanol Assay Kit. In brief, 90 μL working reagent (containing 80 μL assay buffer, 1 μL enzyme A, 1 μL enzyme B, 2.5 μL NAD and 14 μL MTT) was added to 10 μL of serum sample, and the mixture was allowed to react at room temperature for 30 min after mixing gently and thoroughly. Then, 100 μL stop reagent was used to terminate the reaction. The absorbance was read at a wavelength of 565 nm using an ELISA reader, and the ethanol concentration in the serum was calculated using the formula provided by the manufacturer.

2.5. Analysis of Hepatic Alcohol Dehydrogenase (ADH) and Acetaldehyde Dehydrogenase (ALDH) Activities

The ADH and ALDH activities in the liver tissue of rats were analyzed using the ADH and ALDH Activity Colorimetric Assay Kits according to the manufacturer’s manual. 50 mg of tissue was added to 200 μL of ice-cold assay buffer and homogenized, followed by centrifugation (13,000× g, 10 min) to remove insoluble matter. Then, 2 μL of liver homogenate was transferred to the 96-well plate, and 100 μL of reaction mixture (containing 82 μL ADH assay buffer, 8 μL developer, and 10 μL substrate) was added to each well and allowed to react at 37°C. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm using an ELISA reader, and the activities of ADH and ALDH were calculated using the formula provided by the manufacturer.

2.6. Analysis of Hepatic Catalase (CAT) and Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Activities

For the analysis of gastric CAT activity, 10 mg of liver tissue was added to 100 μL of buffer (containing 1 mM EDTA and 50 mM K2HPO4) and homogenized. After centrifugation at 10,000× g for 15 min at 4°C, the supernatant for CAT activity analysis was obtained. Prepared the homogenate of gastric tissue for SOD activity determination, 30 mg of liver tissue was transferred into the homogenizing tube filled with beads, then 270 μL of buffer (containing 12 mM K2HPO4, 8 mM KH2PO4, and 1.5% KCl) was added and then homogenized. The supernatant was then obtained by centrifugation of the homogenate for 30 min at 16,400× g at 4°C. Then, the CAT and SOD activities of supernatant fraction were analyzed using commercial assay kit according to the manufacturer’s procedure.

2.7. Analysis of Hepatic Protein Expression

After the liver tissue was homogenized with lysis buffer, the protein level of the homogenate was determined. The above protein solution was added with 1/6 volume of sample buffer, heated at 100°C for 10 min, cooled in an ice bath, and then subjected to protein electrophoresis using SDS-PAGE. Then, the proteins after electrophoresis were transferred from the gel to the polyvinylidene difluride (PVDF) membrane at 300 mA for 2 h. After transfer, the PVDF membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk powder solution [soaked in PBST (phosphate buffered saline tween 20)] at room temperature for 1 h. Then, the primary antibody (β-actin, COX-2, iNOS and TNF-α) diluted with skim milk powder solution was added to react at room temperature overnight. After reacted with the primary antibody, the PVDF membrane was washed with PBST followed by incubation in secondary antibody solution for 1-2 h. Thereafter, the membrane was incubated with ECL reagent for 1 min, and the signal of the target proteins was captured by a luminescent imaging system (Hansor, Taichung, Taiwan). The ImageJ® software was applied to quantify the signal intensity of target proteins.

2.8. Statistical analysis

The data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s multiple comparison test to test for significant differences among treatments (p<0.05). Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD).

3. Results and Discussion

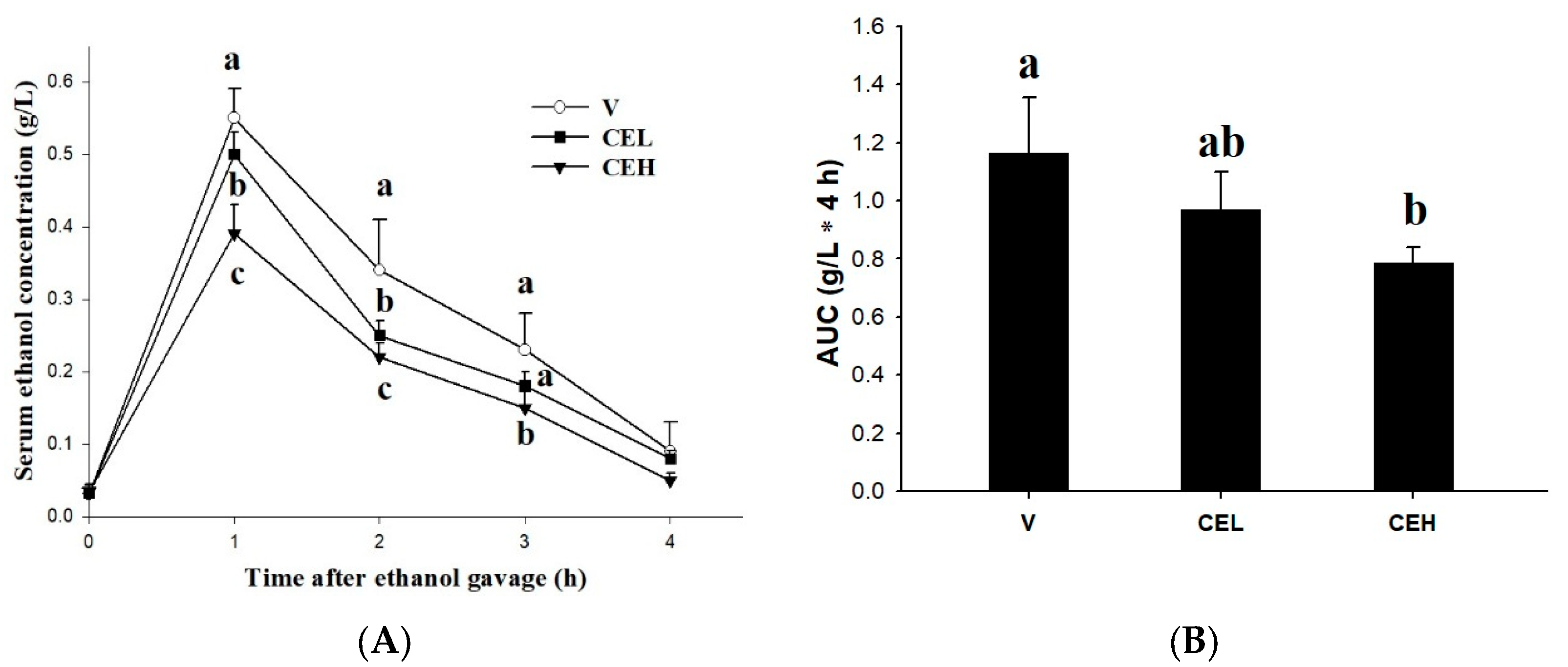

3.1. Effect of CE Supplement on Serum Ethanol Concentration in Rats

Figure 1A shows the effect of oral administration of CE on the ethanol concentration in rat serum. Blood samples were collected at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 h after treatment with 2 g/kg bw of ethanol, and the serum ethanol concentration was determined. The results showed that the treatment of ethanol obviously increased the ethanol concentration in the serum of rats, which reached its peak at 1 h after ethanol-loaded, then gradually decreased and reached the lowest level after 4 h. The serum ethanol concentration of rats in the vehicle group (V) was as high as 0.55±0.04 g/L at the 1st h, while the administration of CE reduced the serum ethanol levels in rats. The serum ethanol concentrations of rats of the 1-fold CE (CEL) and 2-fold CE (CEH) groups were 0.50±0.03 g/L and 0.39±0.04 g/L, respectively. There was a significant difference between the CEH group and the V group (

p<0.05), and this trend was maintained until the 2nd and 3rd h, but there was no significant difference among all groups after the 4th h (

p>0.05). The area under the serum ethanol curve (AUC) represents the extent of total exposure to the ethanol in subjects over a given period of time. The results showed in

Figure 1B indicated that the AUC of rats in the CEH group is significantly lower than that in the V group (

p<0.05), while there is no significant difference in AUC between the CEM group and the V group. Since ancient times, freshwater clams have been considered to possess hepatoprotective effects in Asia, and even the Compendium of Materia Medica (Bencao Gangmu) in Chinese recorded that freshwater clams have medicinal properties in alcohol detoxification. The previous study performed by Chijimatsu et al. [

18] also showed that freshwater clam extract accelerated the clearance of ethanol in the blood of rats acutely treated ethanol. Moreover, freshwater clam protein hydrolysate was reported that could be a potential functional food for advancing alcohol metabolism in an acute alcohol exposure animal model [

19]. Freshwater clams have been widely documented to contain several biologically active ingredients, such as phytosterols, polysaccharides, carotenoids, essential amino acids, and peptides [

16,

20,

21], which may be one of the main factors that enable freshwater clams to promote alcohol metabolism. Our previous study also pointed out that CE has a certain amount of taurine [

22], which has been found to stimulate the metabolism of alcohol.

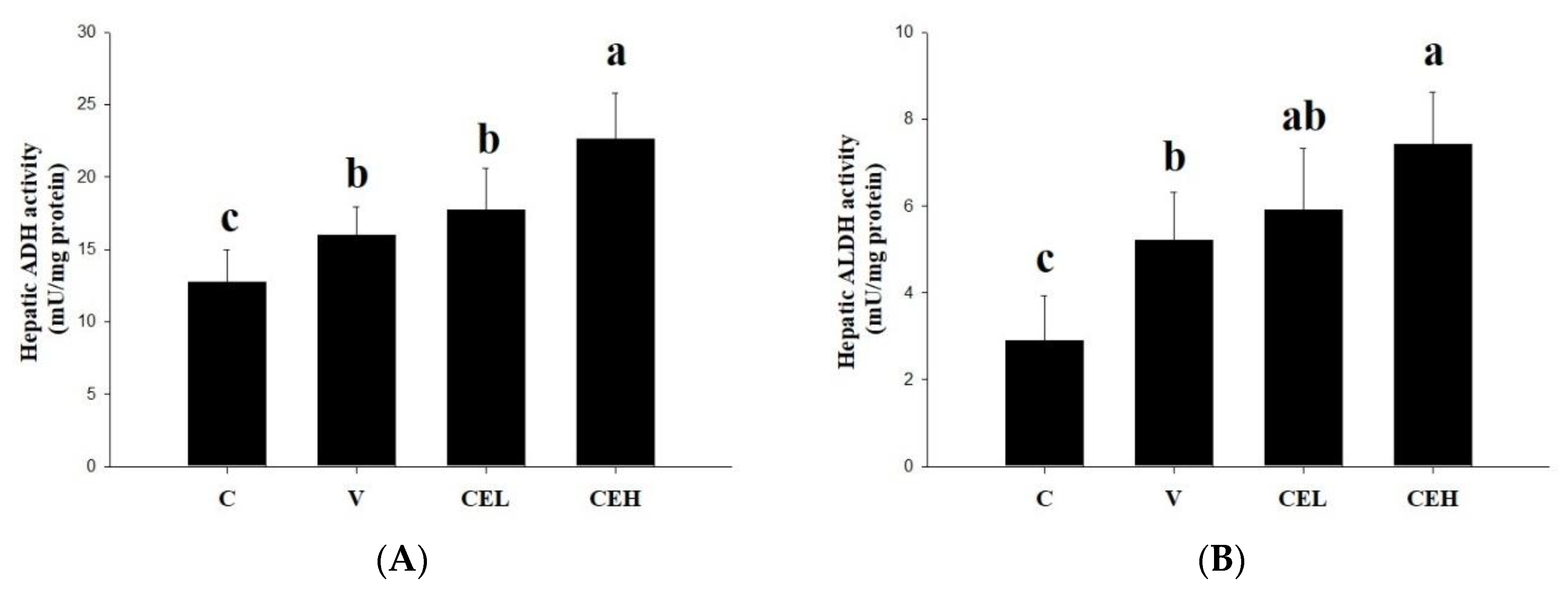

3.2. Effect of CE Supplement on the Activities of Hepatic ADH and ALDH in Rats

One of the main pathways of alcohol metabolism in the human body is that when blood flows through the liver, ALD catalyzes the metabolism of alcohol into acetaldehyde [

23]. In the present study, we measured the ADH activity in rat liver to clarify whether the CE can reduce the serum ethanol concentration in rats by activating the activity of enzymes related to alcohol metabolism. As shown in

Figure 2A, the hepatic ALD activity of ethanol-fed rats in V group was slightly induced compared with that of rats in C group. After administering the CE, the activity of hepatic ADH in the rats was further increased, and a significant difference was found between the CEH group and the V group (

p<0.05). It is suggested that administration of CE increased the ALD activity in the liver, accelerated the metabolism of ethanol, and thus accelerated the clearance of ethanol in serum of rats. Moreover, we further analyzed the activity of ALDH in the liver and found that the ALDH activity in the rats in the CEH group was significantly higher than that in the V group (

Figure 2B;

p<0.05). ALDH is a critical enzyme for the body to convert the more harmful acetaldehyde, a major factor of a series of unpleasant effects, into the relatively non-toxic acetate [

24]. Any natural substances or products that can increase the activity of ADH and ALDH in the liver should have a positive effect on alcohol metabolism and reduce the concentration of alcohol in the blood [

25]. Red ginger, Korean pear, mango, asparagus, and fenugreek have been found to increase the activities or expression of ADH and ALDH, thereby alleviating hangovers and their associated symptoms [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. A protein hydrolysate prepared from the meat of freshwater clam also was indicated that could be a potential nature product for improving alcohol metabolism through enhancement of hepatic ADH and ALDH activities [

19]. The results in the present study showed that CE administration by gavage remarkably enhancing the activities of ADH and ALDH of liver in rats, implying CE could be a candidate nutraceutical for accelerating alcohol metabolism in the body or reliving hangover.

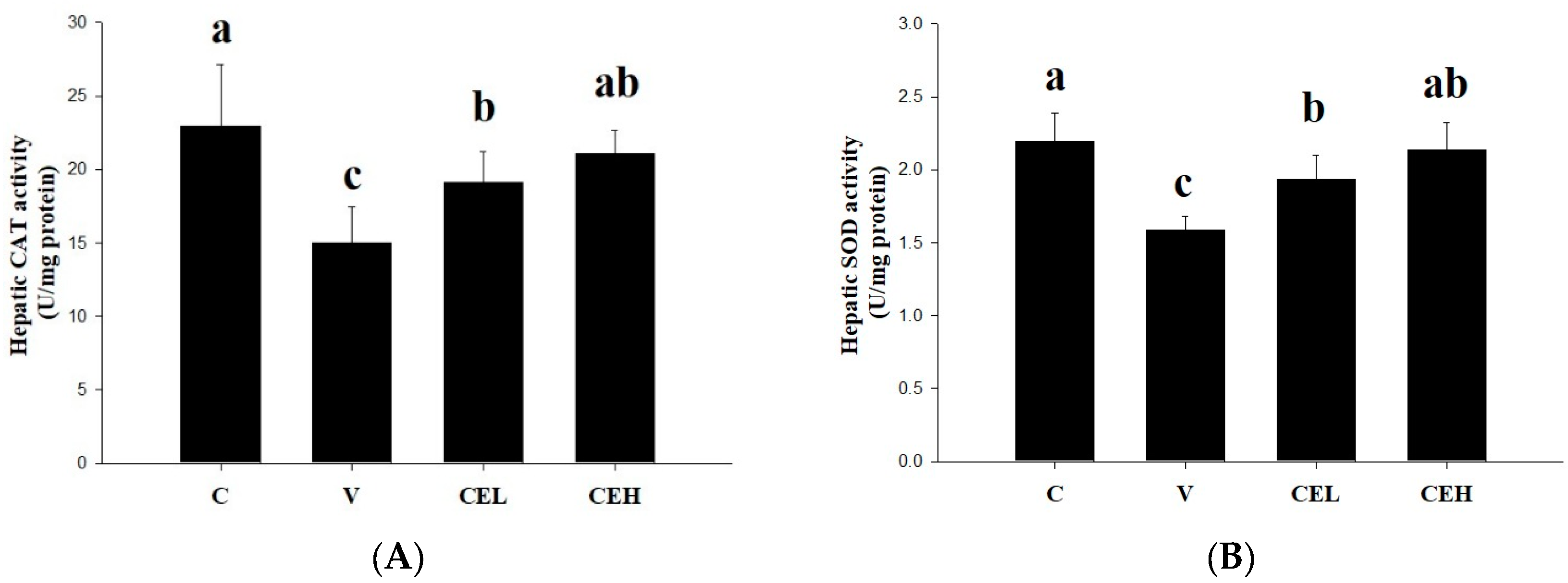

3.3. Effect of CE Supplement on the Activities of Hepatic CAT and SOD in Rats

The effects of CE on the CAT and SOD activities of liver in rats are shown in

Figure 3. Alcohol-loaded remarkably reduced the activities of CAT and SOD in the liver (group C v.s. group V). Administration of CE at either low- or high-doses (group CEL or group CEH) significantly increased the activities of CAT and SOD (

p<0.05). After alcohol consumption, ethanol flows through the blood to the liver, and a large amount of ethanol is converted into acetaldehyde, which accumulates in the liver and promotes the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to oxidative stress and liver damage [

31]. CAT and SOD are known to be the major antioxidant enzymes in the liver that can protect against diverse oxidants yielded during alcohol metabolism [

32]. Furthermore, oxidative stress caused by alcohol has been indicated to deplete antioxidant enzymes in the body, including CAT and SOD [

33], which were depressed by alcohol-loaded in this study. Administration of CE significantly restored the activities of hepatic CAT and SOD, implying that CE improved alcohol-induced damage of antioxidant enzyme system of liver in rats.

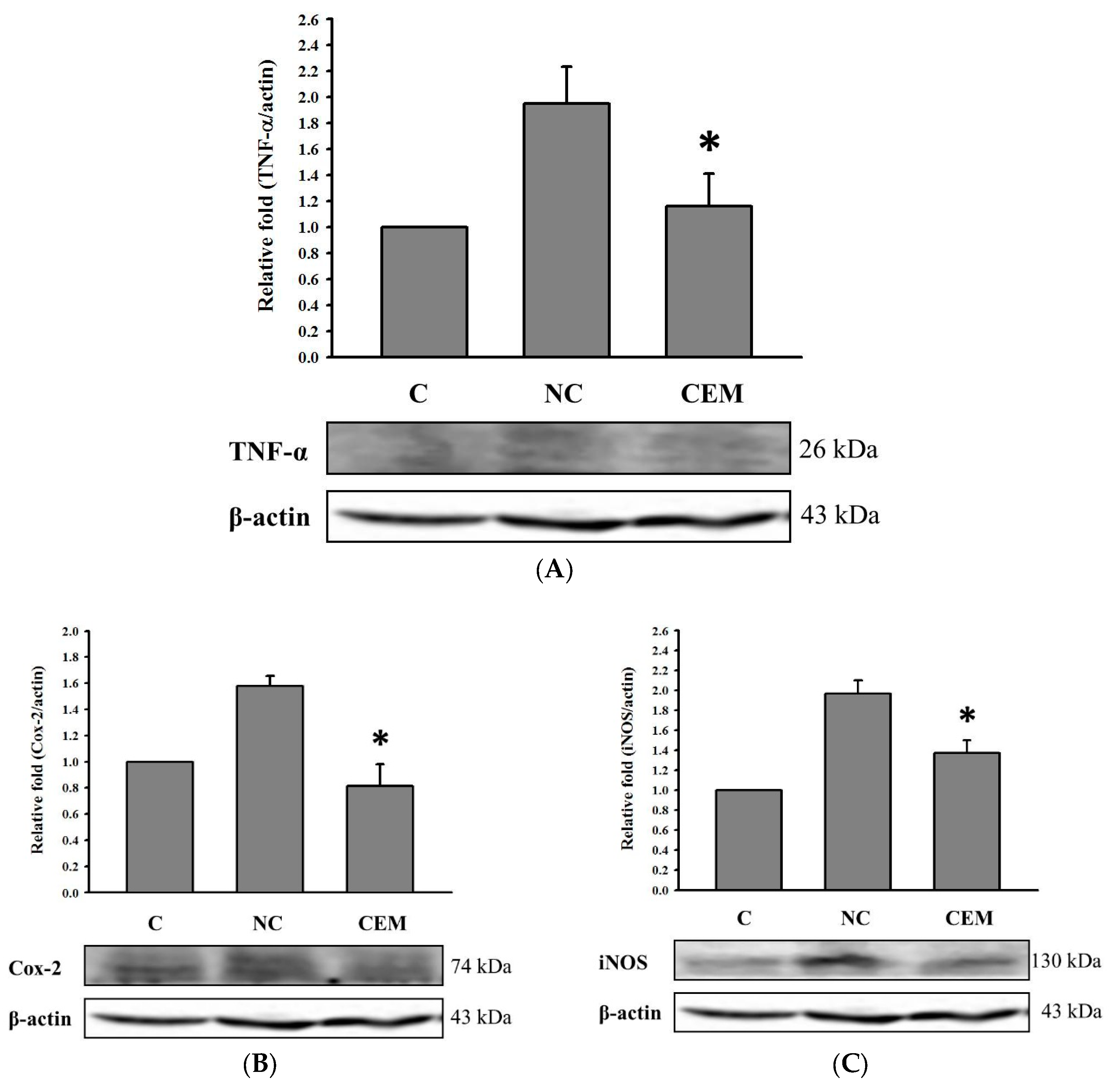

3.4. Effect of CE Supplement on Expression of TNF-α, COX-2, and iNOS Proteins of liver in Rats

In addition to producing ROS and reducing antioxidant enzymes, consuming alcohol also activates pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α [

34].

Figure 4A shows that the effect of 256 mg/ kg bw of CE administration on hepatic TNF-α protein expression in alcohol-fed rats. The expression of TNF-α in group V was remarkably higher than that in group C, and CE administration significantly reduced the alcohol-induced increase in TNF-α protein expression (

p<0.05). Moreover, we also found that alcohol given enhanced the expression of COX-2 and iNOS in the liver of rats (group V v.s. group C;

Figure 4B and 4C). Several literatures indicate that alcohol treatment increased the expression of inflammatory markers COX-2 and iNOS proteins in liver cells [

35,

36,

37,

38], suggesting that elevated production of COX-2 and iNOS is involved in alcohol metabolism. CE administration significantly decreased the expression of COX-2 and iNOS in the liver of rats, implying that CE can reduce the inflammatory status associated with alcohol metabolism.

4. Conclusions

The results of this study showed that administration of CE could reduce the serum alcohol concentration of rats fed with alcohol. The possible mechanism may be related to the fact that CE can increase the activity of ADH and ALDH in the liver of rats, thereby accelerating the metabolism of alcohol. Moreover, CE can increase the activities of CAT and SOD in the liver and reduce the protein expressions of COX-2, iNOS and TNF-α, indicating that CE can improve the antioxidant status of rats and is beneficial to the metabolism of alcohol.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-T.C., S.-W.T., and Y.-K.C.; methodology, P.-Y.C., I-C.C., and C.-Y.K.; software, I-C.C. and T.-M.W.; validation, T.-M.W. and K.-C.T.; formal analysis, I-C.C., and C.-Y.K.; investigation, P.-Y.C., I-C.C., and C.-Y.K.; resources, S.-T.C. and S.-W.T.; data curation, I-C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.-Y.C. and I-C.C.; writing—review and editing, S.-T.C., S.-W.T., and Y.-K.C.; visualization, T.-M.W. and Y.-K.C.; supervision, K.-C.T. and Y.-K.C ; project administration, Y.-K.C.; funding acquisition, S.-T.C., S.-W.T., and Y.-K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan under grant number NSTC 111-2622-B-020-003.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The experimental procedures performed on animal were conducted under the guideline and protocol approved by the IACUC of National Pingtung University of Science and Technology (approved protocol NPUST-105-024).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Mr. Chih-Chiang Tsai and Mr. Chien-Hsing Chiang, employees of Li Chuan Aquafarm Co., Ltd. (Hualien, Taiwan), for providing the freshwater clam used in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yokoyama, M.; Yokoyama, T.; Funazu, K.; Yamashita, T.; Kondo, S.; Hosoai, H.; Yokoyama, A.; Nakamura, H. Associations between headache and stress, alcohol drinking, exercise, sleep, and comorbid health conditions in a Japanese population. J Headache Pain 2009, 10, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penning, R.; McKinney, A.; Verster, J.C. Alcohol hangover symptoms and their contribution to the overall hangover severity. Alcohol and Alcoholism 2012, 47, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.K.; Hobbs, M.; Klipp, L.; Bell, S.; Edwards, K.; O’Hara, P.; Drummond, C. Monitoring drinking behaviour and motivation to drink over successive doses of alcohol. Behavioural Pharmacology 2010, 21, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, R.L.J.; Hammond, L.; Harris, S. Systemic effects of excessive alcohol consumption. Nursing2025 2023, 53, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, A. Alcohol in the body. Bmj 2005, 330, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaratani, H.; Tsujimoto, T.; Douhara, A.; Takaya, H.; Moriya, K.; Namisaki, T.; Noguchi, R.; Yoshiji, H.; Fujimoto, M.; Fukui, H. The effect of inflammatory cytokines in alcoholic liver disease. Mediators of Inflammation 2013, 2013, 495156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umulis, D.M.; Gürmen, N.M.; Singh, P.; Fogler, H.S. A physiologically based model for ethanol and acetaldehyde metabolism in human beings. Alcohol 2005, 35, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, J.F.M.; Barbancho, M. Acetaldehyde detoxification mechanisms in Drosophila melanogaster adults involving aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) enzymes. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 1992, 22, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Suh, H.J.; Hong, K.B.; Jung, E.J.; Ahn, Y. Combination of cysteine and glutathione prevents ethanol-induced hangover and liver damage by modulation of Nrf2 signaling in HepG2 cells and mice. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-Y.; Lee, G.-H.; Hoang, T.-H.; Kim, S.W.; Kang, C.G.; Jo, J.H.; Chung, M.J.; Min, K.; Chae, H.-J. Turmeric extract (Curcuma longa L.) regulates hepatic toxicity in a single ethanol binge rat model. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Han, M.; Matsumoto, A.; Wang, Y.; Thompson, D.C.; Vasiliou, V. Glutathione and transsulfuration in alcohol-associated tissue injury and carcinogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol 2018, 1032, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J.; Min, T.; Bai, Y.; He, J.; Cao, H.; Che, Q.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. Oxidative stress in alcoholic liver disease, focusing on proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids: A review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 278, 134809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilarri, M.I.; Freitas, F.; Costa-Dias, S.; Antunes, C.; Guilhermino, L.; Sousa, R. Associated macrozoobenthos with the invasive Asian clam Corbicula fluminea. Journal of Sea Research 2012, 72, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chijimatsu, T.; Tatsuguchi, I.; Oda, H.; Mochizuki, S. A Freshwater clam (Corbicula fluminea) extract reduces cholesterol level and hepatic lipids in normal rats and xenobiotics-induced hypercholesterolemic rats. J Agric Food Chem 2009, 57, 3108–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.L.; Hsu, C.C.; Yen, G.C. Hepatoprotection by freshwater clam extract against CCl4-induced hepatic damage in rats. Am J Chin Med 2010, 38, 881–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, N.; Chen, S.; Ye, X.; Zhong, J.; Wu, N.; Dong, S.; Yang, B.; Liu, D. Antioxidant and anti-tumor activity of a polysaccharide from freshwater clam, Corbicula fluminea. Food Funct 2013, 4, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isnain, F.S.; Liao, N.C.; Tsai, H.Y.; Zhao, Y.J.; Huang, C.H.; Hsu, J.L.; Wardani, A.K.; Chen, Y.K. Freshwater clam extract attenuates indomethacin-induced gastric damage in vitro and in vivo. Foods 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chijimatsu, T.; Yamada, A.; Miyaki, H.; Yoshinaga, T.; Murata, N.; Hata, M.; Abe, K.; Oda, H.; Mochizuki, S. Effect of freshwater clam (Corbicula fluminea) extract on liver function in rats. Journal of the Japanese Society for Food Science and Technology-Nippon Shokuhin Kagaku Kogaku Kaishi 2008, 55, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhang, C.; Qin, X.; Cao, W.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Zheng, H.; Lin, H.; Chen, Z. Hepatoprotective effect of clam (Corbicula fluminea) protein hydrolysate on alcohol-induced liver injury in mice and partial identification of a hepatoprotective peptide from the hydrolysate. Food Science and Technology 2022, 42, e61522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.J.; Liu, Y.C.; Chang, C.J.; Pan, M.H.; Lee, M.F.; Pan, B.S. Hepatoprotective mechanism of freshwater clam extract alleviates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: elucidated in vitro and in vivo models. Food Funct 2018, 9, 6315–6325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, N.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, R.; Ye, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, D.; Liu, R. Protein-bound polysaccharide from Corbicula fluminea inhibits cell growth in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0167889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isnain, F.S.; Liao, N.-C.; Tsai, H.-Y.; Zhao, Y.-J.; Huang, C.-H.; Hsu, J.-L.; Wardani, A.K.; Chen, Y.-K. Freshwater clam extract attenuates indomethacin-induced gastric damage in vitro and in vivo. Foods 2023, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Gan, L.Q.; Li, S.K.; Zheng, J.C.; Xu, D.P.; Li, H.B. Effects of herbal infusions, tea and carbonated beverages on alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase activity. Food Funct 2014, 5, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.S.; Hsiao, J.-R.; Chen, C.-H. ALDH2 polymorphism and alcohol-related cancers in Asians: A public health perspective. Journal of Biomedical Science 2017, 24, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, S.; Li, H.B. Natural products for the prevention and treatment of hangover and alcohol use disorder. Molecules 2016, 21, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Kwak, J.H.; Jeon, G.; Lee, J.W.; Seo, J.H.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, J.H. Red ginseng relieves the effects of alcohol consumption and hangover symptoms in healthy men: A randomized crossover study. Food Funct 2014, 5, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Isse, T.; Kawamoto, T.; Baik, H.W.; Park, J.Y.; Yang, M. Effect of Korean pear (Pyruspyrifolia cv. Shingo) juice on hangover severity following alcohol consumption. Food Chem Toxicol 2013, 58, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; S, K.C.; Min, T.S.; Kim, Y.; Yang, S.O.; Kim, H.S.; Hyun, S.H.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.S.; Choi, H.K. Ameliorating effects of Mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruit on plasma ethanol level in a mouse model assessed with H-NMR based metabolic profiling. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2011, 48, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.Y.; Cui, Z.G.; Lee, S.R.; Kim, S.J.; Kang, H.K.; Lee, Y.K.; Park, D.B. Effects of Asparagus officinalis extracts on liver cell toxicity and ethanol metabolism. J Food Sci 2009, 74, H204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaviarasan, S.; Anuradha, C.V. Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum graecum) seed polyphenols protect liver from alcohol toxicity: a role on hepatic detoxification system and apoptosis. Pharmazie 2007, 62, 299–304. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.-Y.; Gomelsky, M.; Duan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Gomelsky, L.; Zhang, X.; Epstein, P.N.; Ren, J. Overexpression of aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH2) transgene prevents acetaldehyde-induced cell injury in human umbilical vein endothelial cells: Role of ERK and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 11244–11252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, D.; Chhonker, S.K.; Naik, R.A.; Koiri, R.K. Modulation of antioxidant enzymes, SIRT1 and NF-κB by resveratrol and nicotinamide in alcohol-aflatoxin B1-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology 2021, 35, e22625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsermpini, E.E.; Plemenitaš Ilješ, A.; Dolžan, V. Alcohol-induced oxidative stress and the role of antioxidants in alcohol use disorder: A systematic review. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, G.; Petrasek, J.; Bala, S. Innate immunity and alcoholic liver disease. Dig Dis 2012, 30 Suppl 1, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, B.S.; Rodrigues, G.B.; Rocha, S.W.S.; Ribeiro, E.L.; Gomes, F.O.d.S.; e Silva, A.K.S.; Peixoto, C.A. Inhibition of NF-κB activation by diethylcarbamazine prevents alcohol-induced liver injury in C57BL/6 mice. Tissue and Cell 2014, 46, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.W.; Jang, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.G.; Cheon, Y.K.; Kim, Y.S.; Cho, Y.D.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, J.S.; Jin, S.Y.; et al. Increased expression of cyclooxygenase-2 is associated with the progression to cirrhosis. Korean J Intern Med 2010, 25, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.D.; Lee, S.R.; Kim, T.; Jang, S.A.; Kang, S.C.; Koo, H.J.; Sohn, E.; Bak, J.P.; Namkoong, S.; Kim, H.K.; et al. Fucoidan from Fucus vesiculosus protects against alcohol-induced liver damage by modulating inflammatory mediators in mice and HepG2 cells. Mar Drugs 2015, 13, 1051–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.H.; Jung, E.S.; Park, Y.M.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, B.K.; Kim, D.G.; Ryu, W.S. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in hepatocellular carcinoma and growth inhibition of hepatoma cell lines by a COX-2 inhibitor, NS-398. Clinical Cancer Research 2001, 7, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).