Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Neuropathological Findings in ASD and a Neurodevelopmental Narrative

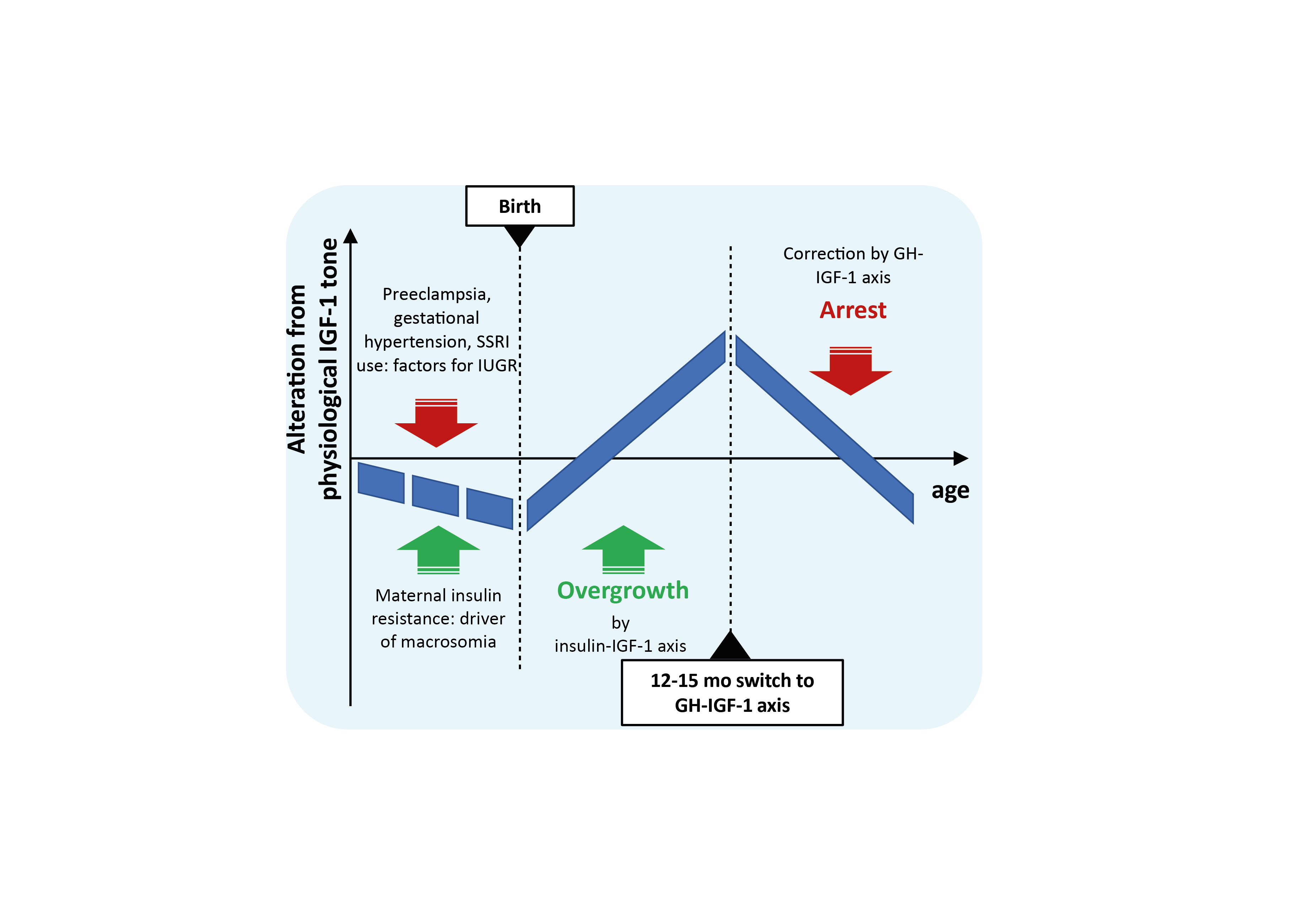

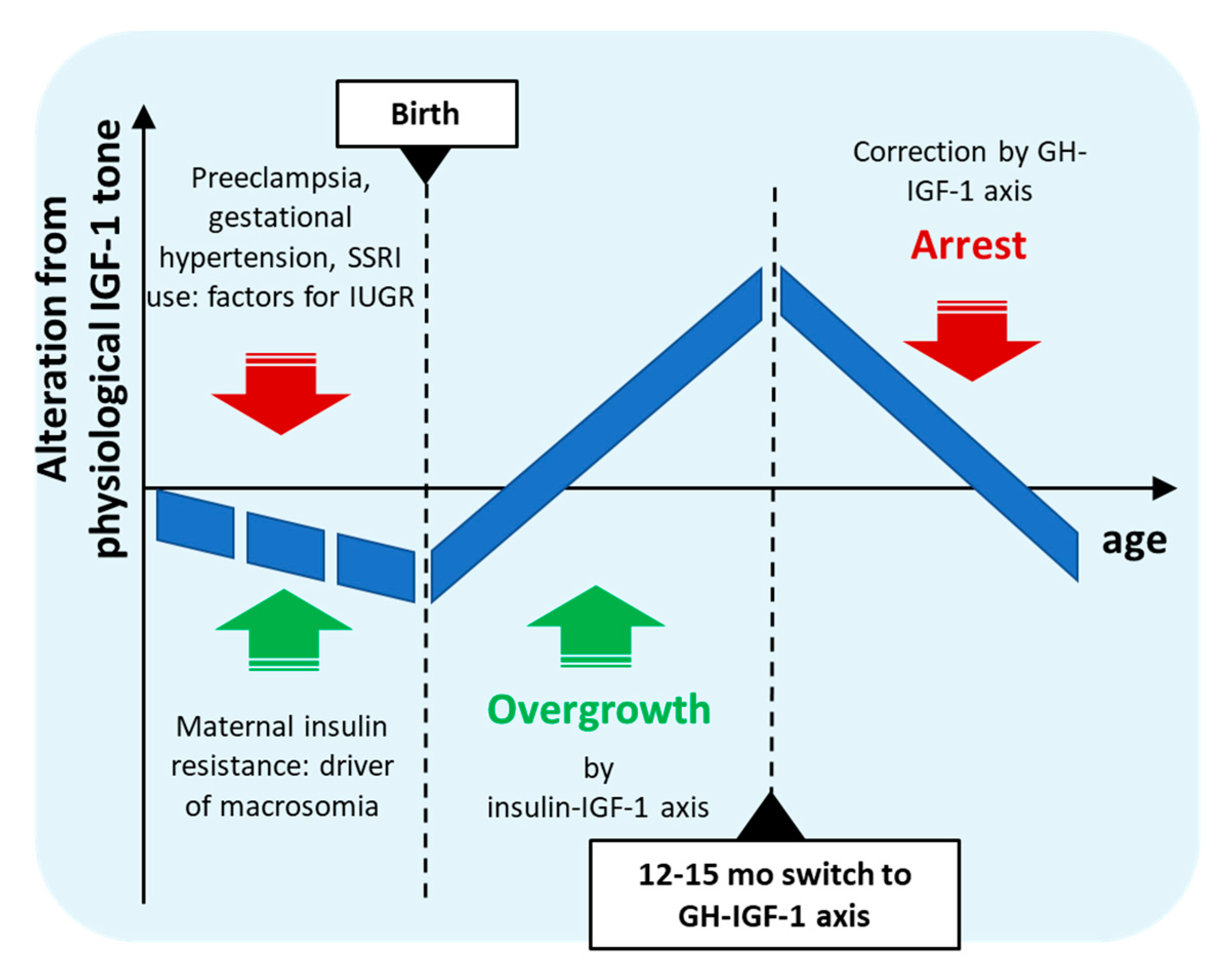

1.3. IGF-1 and Its Dysregulation in Perinatal Complications

2. Hypothesis

2.1. A Possible Etiological Role of IGF-1 Dysregulation in Idiopathic ASD

2.2. Explanation of Observations and Risk Factors of ASD

2.3. Prospective Testing of the Hypothesis

3. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| ASD | Autism spectrum disorder |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| GH | Growth hormone |

| GHRH | Growth hormone releasing hormone |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| IGFBP | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein |

| IUGR | Intrauterine growth restriction |

| PC | Purkinje cell |

| SGA | Small for gestational age |

| SSRI | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor |

References

- Lord, C.; Brugha, T.S.; Charman, T.; Cusack, J.; Dumas, G.; Frazier, T.; Jones, E.J.H.; Jones, R.M.; Pickles, A.; State, M.W.; et al. Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, A.; DeMayo, M.M.; Glozier, N.; Guastella, A.J. An Overview of Autism Spectrum Disorder, Heterogeneity and Treatment Options. Neurosci Bull 2017, 33, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.P.; Du, J. Brief Report: Forecasting the Economic Burden of Autism in 2015 and 2025 in the United States. J Autism Dev Disord 2015, 45, 4135–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordahl, C.W.; Andrews, D.S.; Dwyer, P.; Waizbard-Bartov, E.; Restrepo, B.; Lee, J.K.; Heath, B.; Saron, C.; Rivera, S.M.; Solomon, M.; et al. The Autism Phenome Project: Toward Identifying Clinically Meaningful Subgroups of Autism. Front Neurosci 2022, 15, 786220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, D.G. Examining the Causes of Autism. Cerebrum 2017, 2017, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hertz-Picciotto, I.; Schmidt, R.J.; Krakowiak, P. Understanding Environmental Contributions to Autism: Causal Concepts and the State of Science. Autism Research 2018, 11, 554–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova, M.F.; Casanova, E.L.; Frye, R.E.; Baeza-Velasco, C.; LaSalle, J.M.; Hagerman, R.J.; Scherer, S.W.; Natowicz, M.R. Editorial: Secondary vs. Idiopathic Autism. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniowiecka-Kowalnik, B.; Nowakowska, B.A. Genetics and Epigenetics of Autism Spectrum Disorder—Current Evidence in the Field. J Appl Genet 2019, 60, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.N.; Schendel, D.E.; Francis, R.W.; Windham, G.C.; Bresnahan, M.; Levine, S.Z.; Reichenberg, A.; Gissler, M.; Kodesh, A.; Bai, D.; et al. Recurrence Risk of Autism in Siblings and Cousins: A Multinational, Population-Based Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019, 58, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tick, B.; Bolton, P.; Happé, F.; Rutter, M.; Rijsdijk, F. Heritability of Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Meta-Analysis of Twin Studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2016, 57, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoli, D.S.; State, M.W. Autism Spectrum Disorder Genetics and the Search for Pathological Mechanisms. Am J Psychiatr 2021, 178, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van’t Hof, M.; Tisseur, C.; van Berckelear-Onnes, I.; van Nieuwenhuyzen, A.; Daniels, A.M.; Deen, M.; Hoek, H.W.; Ester, W.A. Age at Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis from 2012 to 2019. Autism 2021, 25, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozonoff, S.; Iosif, A.-M.; Baguio, F.; Cook, I.C.; Moore Hill, M.; Hutman, T.; Rogers, S.J.; Rozga, A.; Sangha, S.; Sigman, M.; et al. A Prospective Study of the Emergence of Early Behavioral Signs of Autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010, 49, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.J.H.; Venema, K.; Earl, R.; Lowy, R.; Barnes, K.; Estes, A.; Dawson, G.; Webb, S.J. Reduced Engagement with Social Stimuli in 6-Month-Old Infants with Later Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Longitudinal Prospective Study of Infants at High Familial Risk. J Neurodev Disord 2016, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, K.; Pickles, A.; Lord, C. Trajectories of Autism Severity in Children Using Standardized ADOS Scores. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brian, J.; Bryson, S.E.; Smith, I.M.; Roberts, W.; Roncadin, C.; Szatmari, P.; Zwaigenbaum, L. Stability and Change in Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis from Age 3 to Middle Childhood in a High-Risk Sibling Cohort. Autism 2016, 20, 888–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kočovská, E.; Billstedt, E.; Ellefsen, A.; Kampmann, H.; Gillberg, I.C.; Biskupstø, R.; Andorsdóttir, G.; Stóra, T.; Minnis, H.; Gillberg, C. Autism in the Faroe Islands: Diagnostic Stability from Childhood to Early Adult Life. Scient World J 2013, 592371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orm, S.; Andersen, P.N.; Fossum, I.N.; Øie, M.G.; Skogli, E.W. Brief Report: Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnostic Persistence in a 10-Year Longitudinal Study. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2022, 97, 102007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piven, J.; Elison, J.T.; Zylka, M.J. Toward a Conceptual Framework for Early Brain and Behavior Development in Autism. Mol Psychiatry 2017, 22, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazlett, H.C.; Gu, H.; Munsell, B.C.; Kim, S.H.; Styner, M.; Wolff, J.J.; Elison, J.T.; Swanson, M.R.; Zhu, H.; Botteron, K.N.; et al. Early Brain Development in Infants at High Risk for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nature 2017, 542, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, D.; Chang, L.; Ernst, T.M.; Curran, M.; Buchthal, S.D.; Alicata, D.; Skranes, J.; Johansen, H.; Hernandez, A.; Yamakawa, R.; et al. Structural Growth Trajectories and Rates of Change in the First 3 Months of Infant Brain Development. JAMA Neurol 2014, 71, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knickmeyer, R.C.; Gouttard, S.; Kang, C.; Evans, D.; Wilber, K.; Smith, J.K.; Hamer, R.M.; Lin, W.; Gerig, G.; Gilmore, J.H. A Structural MRI Study of Human Brain Development from Birth to 2 Years. J Neurosci 2008, 28, 12176–12182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, D.G. The Promise and the Pitfalls of Autism Research: An Introductory Note for New Autism Researchers. Brain Res 2011, 1380, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Son, M.J.; Son, C.Y.; Radua, J.; Eisenhut, M.; Gressier, F.; Koyanagi, A.; Carvalho, A.F.; Stubbs, B.; Solmi, M.; et al. Environmental Risk Factors and Biomarkers for Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Umbrella Review of the Evidence. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozonoff, S.; Young, G.S.; Carter, A.; Messinger, D.; Yirmiya, N.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Bryson, S.; Carver, L.J.; Constantino, J.N.; Dobkins, K.; et al. Recurrence Risk for Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Baby Siblings Research Consortium Study. Pediatrics 2011, 128, e488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maenner, M.J.; Shaw, K.A.; Bakian, A. V.; Bilder, D.A.; Durkin, M.S.; Esler, A.; Furnier, S.M.; Hallas, L.; Hall-Lande, J.; Hudson, A.; et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2018. MMWR. Surveill Summ 2021, 70, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomes, R.; Hull, L.; Polmear Locke Mandy, W. What Is the Male-to-Female Ratio in Autism Spectrum Disorder? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017, 56, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wu, F.; Ding, Y.; Hou, J.; Bi, J.; Zhang, Z. Advanced Parental Age and Autism Risk in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2017, 135, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandin, S.; Schendel, D.; Magnusson, P.; Hultman, C.; Surén, P.; Susser, E.; GrØnborg, T.; Gissler, M.; Gunnes, N.; Gross, R.; et al. Autism Risk Associated with Parental Age and with Increasing Difference in Age between the Parents. Mol Psychiatry 2016, 21, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.; Reichenberg, A.; Kolevzon, A. Prenatal and Perinatal Metabolic Risk Factors for Autism: A Review and Integration of Findings from Population-Based Studies. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2021, 34, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dachew, B.A.; Mamun, A.; Maravilla, J.C.; Alati, R. Pre-Eclampsia and the Risk of Autism-Spectrum Disorder in Offspring: Meta-Analysis. Br J Psychiatr 2018, 212, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, Y.C.; Keskin-Arslan, E.; Acar, S.; Sozmen, K. Prenatal Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Use and the Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Reprod Toxicol 2016, 66, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leshem, R.; Bar-Oz, B.; Diav-Citrin, O.; Gbaly, S.; Soliman, J.; Renoux, C.; Matok, I. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) During Pregnancy and the Risk for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in the Offspring: A True Effect or a Bias? A Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis. Curr Neuropharmacol 2021, 19, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Jing, J.; Bowers, K.; Liu, B.; Bao, W. Maternal Diabetes and the Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorders in the Offspring: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Autism Dev Disord 2014, 44, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Geng, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, G. Prenatal, Perinatal, and Postnatal Factors Associated with Autism: A Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2017, 96, e6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, J.; Wilson, C.A. The Association between Gestational Diabetes and ASD and ADHD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, D.A.; Rajanandh, M.G. Does Metabolic Syndrome during Pregnancy Really a Risk to Autism Spectrum Disorder? Diab Metabol Syndr: Clin Res Rev 2020, 14, 1591–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, S.; Xu, S.; Weng, S.; Liu, Z. Maternal Body Mass Index and Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Offspring: A Meta-Analysis. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 34248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modabbernia, A.; Velthorst, E.; Reichenberg, A. Environmental Risk Factors for Autism: An Evidence-Based Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Mol Autism 2017, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Rao, S.C.; Bulsara, M.K.; Patole, S.K. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Preterm Infants: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20180134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, J.; Su, Y.; Lu, H.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Shang, S.; Yue, W. Association of Birth Weight with Risk of Autism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2022, 92, 101934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.J.; Chang, J.; Chawarska, K. Early Generalized Overgrowth in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Prevalence Rates, Gender Effects, and Clinical Outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014, 53, 1063–1073.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawarska, K.; Campbell, D.; Chen, L.; Shic, F.; Klin, A.; Chang, J. Early Generalized Overgrowth in Boys With Autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011, 68, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cárdenas-de-la-Parra, A.; Lewis, J.D.; Fonov, V.S.; Botteron, K.N.; McKinstry, R.C.; Gerig, G.; Pruett, J.R.; Dager, S.R.; Elison, J.T.; Styner, M.A.; et al. A Voxel-Wise Assessment of Growth Differences in Infants Developing Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neuroimage Clin 2021, 29, 102551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, R.; Gabriele, S.; Persico, A.M. Head Circumference and Brain Size in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 2015, 234, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courchesne, E.; Carper, R.; Akshoomoff, N. Evidence of Brain Overgrowth in the First Year of Life in Autism. J Am Med Assoc 2003, 290, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazlett, H.C.; Poe, M.D.; Gerig, G.; Styner, M.; Chappell, C.; Smith, R.G.; Vachet, C.; Piven, J. Early Brain Overgrowth in Autism Associated With an Increase in Cortical Surface Area Before Age 2 Years. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011, 68, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, M.D.; Nordahl, C.W.; Li, D.D.; Lee, A.; Angkustsiri, K.; Emerson, R.W.; Rogers, S.J.; Ozonoff, S.; Amaral, D.G. Extra-Axial Cerebrospinal Fluid in High-Risk and Normal-Risk Children with Autism Aged 2–4 Years: A Case-Control Study. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surén, P.; Stoltenberg, C.; Bresnahan, M.; Hirtz, D.; Lie, K.K.; Lipkin, W.I.; Magnus, P.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; Schjølberg, S.; Susser, E.; et al. Early Growth Patterns in Children with Autism. Epidemiol 2013, 24, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, N.; Travers, B.G.; Bigler, E.D.; Prigge, M.B.D.; Froehlich, A.L.; Nielsen, J.A.; Cariello, A.N.; Zielinski, B.A.; Anderson, J.S.; Fletcher, P.T.; et al. Longitudinal Volumetric Brain Changes in Autism Spectrum Disorder Ages 6-35 Years. Autism Res 2015, 8, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, E.; Calderoni, S.; Marchi, V.; Muratori, F.; Cioni, G.; Guzzetta, A. The First 1000 Days of the Autistic Brain: A Systematic Review of Diffusion Imaging Studies. Front Hum Neurosci 2015, 9, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J.J.; Gu, H.; Gerig, G.; Elison, J.T.; Styner, M.; Gouttard, S.; Botteron, K.N.; Dager, S.R.; Dawson, G.; Estes, A.M.; et al. Differences in White Matter Fiber Tract Development Present From 6 to 24 Months in Infants With Autism. Am J Psychiatr 2012, 169, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solso, S.; Xu, R.; Proudfoot, J.; Hagler, D.J.; Campbell, K.; Venkatraman, V.; Carter Barnes, C.; Ahrens-Barbeau, C.; Pierce, K.; Dale, A.; et al. Diffusion Tensor Imaging Provides Evidence of Possible Axonal Overconnectivity in Frontal Lobes in Autism Spectrum Disorder Toddlers. Biol Psychiatry 2016, 79, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinonen, K.; Räikkönen, K.; Pesonen, A.K.; Andersson, S.; Kajantie, E.; Eriksson, J.G.; Vartia, T.; Wolke, D.; Lano, A. Trajectories of Growth and Symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children: A Longitudinal Study. BMC Pediatr 2011, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, M.; García-Esteban, R.; Iñiguez, C.; Costa, O.; Fernández-Somoano, A.; Rodríguez-Delhi, C.; Ibarluzea, J.; Lertxundi, A.; Tonne, C.; Sunyer, J.; et al. Head Circumference and Child ADHD Symptoms and Cognitive Functioning: Results from a Large Population-Based Cohort Study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019, 28, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Qiu, T.; Ke, X.; Xiao, X.; Xiao, T.; Liang, F.; Zou, B.; Huang, H.; Fang, H.; Chu, K.; et al. Autism Spectrum Disorder as Early Neurodevelopmental Disorder: Evidence from the Brain Imaging Abnormalities in 2-3 Years Old Toddlers. J Autism Dev Disord 2014, 44, 1633–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino, J.N.; Charman, T. Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Reconciling the Syndrome, Its Diverse Origins, and Variation in Expression. Lancet Neurol 2016, 15, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.; Luthert, P.; Dean, A.; Harding, B.; Janota, I.; Montgomery, M.; Rutter, M.; Lantos, P. A Clinicopathological Study of Autism. Brain 1998, 121, 889–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, M.F.; Buxhoeveden, D.P.; Switala, A.E.; Roy, E.; Switala, A. Minicolumnar Pathology in Autism. Neurology 2002, 58, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmen, S.J.M.C.; Van Engeland, H.; Hof, P.R.; Schmitz, C. Neuropathological Findings in Autism. Brain 2004, 127, 2572–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, A.P.A.; Basson, M.A. The Neuroanatomy of Autism – a Developmental Perspective. J Anat 2017, 230, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, E.R.; Kemper, T.L.; Bauman, M.L.; Rosene, D.L.; Blatt, G.J. Cerebellar Purkinje Cells Are Reduced in a Subpopulation of Autistic Brains: A Stereological Experiment Using Calbindin-D28k. Cerebellum 2008, 7, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegiel, J.; Flory, M.; Kuchna, I.; Nowicki, K.; Ma, S.Y.; Imaki, H.; Wegiel, J.; Cohen, I.L.; London, E.; Wisniewski, T.; et al. Stereological Study of the Neuronal Number and Volume of 38 Brain Subdivisions of Subjects Diagnosed with Autism Reveals Significant Alterations Restricted to the Striatum, Amygdala and Cerebellum. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2014, 2, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, T.L.; Bauman, M.L. The Contribution of Neuropathologic Studies to the Understanding of Autism. Neurology Clinics 1993, 11, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, E.R.; Kemper, T.L.; Rosene, D.L.; Bauman, M.L.; Blatt, G.J. Density of Cerebellar Basket and Stellate Cells in Autism: Evidence for a Late Developmental Loss of Purkinje Cells. J Neurosci Res 2009, 87, 2245–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triarhou, L.C.; Ghetti, B. Stabilisation of Neurone Number in the Inferior Olivary Complex of Aged “Purkinje Cell Degeneration” Mutant Mice. Acta Neuropathol 1991, 81, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanjani, H.; Herrup, K.; Mariani, J. Cell Number in the Inferior Olive of Nervous and Leaner Mutant Mice. J Neurogenet 2004, 18, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heckroth, J.A.; Abbott, L.C. Purkinje Cell Loss from Alternating Sagittal Zones in the Cerebellum of Leaner Mutant Mice. Brain Res 1994, 658, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, G. On the Connections of the Inferior Olives with the Cerebellum in Man. Brain 1908, 31, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, E.D.; Babij, R.; Cortés, E.; Vonsattel, J.P.G.; Faust, P.L. The Inferior Olivary Nucleus: A Postmortem Study of Essential Tremor Cases versus Controls. Mov Disord 2013, 28, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.S.; Hauser, S.L.; Purpura, D.P.; Delong,; G Robert; Swisher, C. N. Autism and Mental Retardation Neuropathologic Studies Performed in Four Retarded Persons With Autistic Behavior. Arch Neurol 1980, 34, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavroudis, I.; Petridis, F.; Kazis, D.; Njau, S.N.; Costa, V.; Baloyannis, S.J. Purkinje Cells Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2019, 34, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhari, K.; Wang, L.; Kruse, J.; Winters, A.; Sumien, N.; Shetty, R.; Prah, J.; Liu, R.; Shi, J.; Forster, M.; et al. Early Loss of Cerebellar Purkinje Cells in Human and a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurol Res 2021, 43, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.; Mcknight, S.; Ai, J.; Baker, A.J. Purkinje Cell Vulnerability to Mild and Severe Forebrain Head Trauma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2006, 65, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Aleman, I.; Pons, S.; Santos-Benito, F.F. Survival of Purkinje Cells in Cerebellar Cultures Is Increased by Insulin-like Growth Factor I. Eur J Neurosci 1992, 4, 864–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croci, L.; Barili, V.; Chia, D.; Massimino, L.; Van Vugt, R.; Masserdotti, G.; Longhi, R.; Rotwein, P.; Consalez, G.G. Local Insulin-like Growth Factor I Expression Is Essential for Purkinje Neuron Survival at Birth. Cell Death Differ 2011, 18, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukudome, Y.; Tabata, T.; Miyoshi, T.; Haruki, S.; Araishi, K.; Sawada, S.; Kano, M. Insulin-like Growth Factor-I as a Promoting Factor for Cerebellar Purkinje Cell Development. Eur J Neurosci 2003, 17, 2006–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, P.; Xing, Y.; Dai, Z.; D’Ercole, J.A. In Vivo Actions of Insulin-like Growth Factor-I (IGF-1) on Cerebellum Development in Transgenic Mice: Evidence That IGF-I Increases Proliferation of Granule Cell Progenitors. Dev Brain Res 1996, 95, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolbert, D.L.; Clark, B.R. GDNF and IGF-I Trophic Factors Delay Hereditary Purkinje Cell Degeneration and the Progression of Gait Ataxia. Exp Neurol 2003, 183, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitoun, E.; Finelli, M.J.; Oliver, P.L.; Lee, S.; Davies, D.K.E. AF4 Is a Critical Regulator of the IGF-1 Signaling Pathway during Purkinje Cell Development. J Neurosci 2009, 29, 15366–15374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, H.T.J.; Dreyfus, C.F.; Back, I.B. Neurotrophin-3 Selectively Increases Cultured Purkinje Cell Survival. Neuroreport 1994, 5, 2497–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Cory, S.; Dreyfus, C.F.; Black, I.B. NGF and Excitatory Neurotransmitters Regulate Survival and Morphogenesis of Cultured Cerebellar Purkinje Cells. J Neurosci 1991, 11, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoumari, A.M.; Wehrlé, R.; De Zeeuw, C.I.; Sotelo, C.; Dusart, I. Inhibition of Protein Kinase C Prevents Purkinje Cell Death but Does Not Affect Axonal Regeneration. J Neurosci 2002, 22, 3531–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, M.E.; Mason, C.A. Granule Neuron Regulation of Purkinje Cell Development: Striking a Balance Between Neurotrophin and Glutamate Signaling. J Neurosci 1998, 18, 3563–3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mount, H.T.J.; Dean, D.O.; Alberch, J.; Dreyfus, C.F.; Black, I.B. Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Promotes the Survival and Morphologic Differentiation of Purkinje Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995, 92, 9092–9096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhala, R.; Turpeinen, U.; Riikonen, R. Low Levels of Insulin-like Growth Factor-I in Cerebrospinal Fluid in Children with Autism. Dev Med Child Neurol 2001, 43, 614–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riikonen, R.; Makkonen, I.; Vanhala, R.; Turpeinen, U.; Kuikka, J.; Kokki, H. Cerebrospinal Fluid Insulin-like Growth Factors IGF-1 and IGF-2 in Infantile Autism. Dev Med Child Neurol 2006, 48, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riikonen, R.; Vanhala, R. Levels of Cerebrospinal Fluid Nerve-Growth Factor Differ in Infantile Autism and Rett Syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol 1999, 41, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riikonen, R. Insulin-like Growth Factors in the Pathogenesis of Neurological Diseases in Children. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18, 2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou Khalil, R. Insulin-Growth-Factor-1 (IGF-1): Just a Few Steps behind the Evidence in Treating Schizophrenia and/or Autism. CNS Spectr 2019, 24, 277–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinman, G. IGF – Autism Prevention/Amelioration. Med Hypotheses 2019, 122, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riikonen, R. Treatment of Autistic Spectrum Disorder with Insulin-like Growth Factors. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2016, 20, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costales, J.; Kolevzon, A. The Therapeutic Potential of Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 in Central Nervous System Disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016, 63, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.M.; Joncas, G.; Reinhardt, R.R.; Farrer, R.; Quarles, R.; Janssen, J.; Mcdonald, M.P.; Crawley, J.N.; Powell-Braxton, L.; Bondy, C.A. Biochemical and Morphometric Analyses Show That Myelination in the Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 Null Brain Is Proportionate to Its Neuronal Composition. J Neurosci 1998, 18, 5673–5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulford, B.E.; Ishii, D.N. Uptake of Circulating Insulin-Like Growth Factors (IGFs) into Cerebrospinal Fluid Appears to Be Independent of the IGF Receptors as Well as IGF-Binding Proteins. Endocrinology 2001, 142, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Kastin, A.J. Interactions of IGF-1 with the Blood-Brain Barrier in Vivo and in Situ. Neuroendocrinology 2000, 72, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.I.; Clemmons, D.R. Insulin-Like Growth Factors and Their Binding Proteins: Biological Actions. Endocr Rev 1995, 16, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakar, S.; Liu, J.-L.; Stannard, B.; Butler, A.; Accili, D.; Sauer, B.; Leroith, D. Normal Growth and Development in the Absence of Hepatic Insulin-like Growth Factor I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999, 96, 7324–7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sun, H.; Yakar, S.; LeRoith, D. Elevated Levels of Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF)-I in Serum Rescue the Severe Growth Retardation of IGF-I Null Mice. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 4395–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratikopoulos, E.; Szabolcs, M.; Dragatsis, I.; Klinakis, A.; Efstratiadis, A. The Hormonal Action of IGF1 in Postnatal Mouse Growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 19378–19383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.G.; Clayton, P.E. Endocrine Control of Growth. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2013, 163, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.H.; Harding, J.E.; Breier, B.H.; Gluckman, P.D. Fetal Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF)-I and IGF-II Are Regulated Differently by Glucose or Insulin in the Sheep Fetus. Reprod Fertil Dev 1996, 8, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowden, A.L. The Insulin-like Growth Factors and Feto-Placental Growth. Placenta 2003, 24, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, A.; Hindmarsh, P.C.; Stanhope, R.G.; Turton, J.P.G.; Cole, T.J.; Preece, M.A.; Dattani, M.T. The Role of Growth Hormone in Determining Birth Size and Early Postnatal Growth, Using Congenital Growth Hormone Deficiency (GHD) as a Model. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2005, 63, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dattani, M.T.; Malhotra, N. A Review of Growth Hormone Deficiency. Paediatr Child Health 2019, 29, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, K.K.; Langkamp, M.; Ranke, M.B.; Whitehead, K.; Hughes, I.A.; Acerini, C.L.; Dunger, D.B. Insulin-like Growth Factor I Concentrations in Infancy Predict Differential Gains in Body Length and Adiposity: The Cambridge Baby Growth Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2009, 90, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xing, K.H.; Qi, J.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, J. Analysis of the Relationship of Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 to the Growth Velocity and Feeding of Healthy Infants. Growth Hormone & IGF Research 2013, 23, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalkidou, A.; Petridou, E.; Papathoma, E.; Salvanos, H.; Trichopoulos, D. Growth Velocity during the First Postnatal Week of Life Is Linked to a Spurt of IGF-I Effect. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2003, 17, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñiguez, G.; Ong, K.; Bazaes, R.; Avila, A.; Salazar, T.; Dunger, D.; Mericq, V. Longitudinal Changes in Insulin-like Growth Factor-I, Insulin Sensitivity, and Secretion from Birth to Age Three Years in Small-for-Gestational-Age Children. J Clin Endocrin Metabol 2006, 91, 4645–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, D. Interrelation between Umbilical Cord Serum Sex Hormones, Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin, Insulin-like Growth Factor I, and Insulin in Neonates from Normal Pregnancies and Pregnancies Complicated by Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995, 80, 2217–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leger, J.; Noel, M.; Limal, J.M.; Czernichow, P. Growth Factors and Intrauterine Growth Retardation. II. Serum Growth Hormone, Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF) I, and IGF-Binding Protein 3 Levels in Children with Intrauterine Growth Retardation Compared with Normal Control Subjects: Prospective Study from Birth to Two Years of Age. Study Group of IUGR. Pediatr Res 1996, 40, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogilvy-Stuart, A.L.; Hands, S.J.; Adcock, C.J.; Holly, J.M.P.; Matthews, D.R.; Mohamed-Ali, V.; Yudkin, J.S.; Wilkinson, A.R.; Dunger, D.B. Insulin, Insulin-Like Growth Factor I (IGF-I), IGF-Binding Protein-1, Growth Hormone, and Feeding in the Newborn. J Clin Endocrin Metabol 1998, 83, 3550–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, L.C.K.; Tam, S.Y.M.; Kwan, E.Y.W.; Tsang, A.M.C.; Karlberg, J. Onset of Significant GH Dependence of Serum IGF-I and IGF-Binding Protein 3 Concentrations in Early Life. Pediatr Res 2001, 50, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaelsen, K. Effect of Protein Intake from 6 to 24 Months On-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) Levels, Body, Linear Growth Velocity, and Linear Growth: What Are the Implications for stunting and Wasting? Food Nutr Bull 2013, 34, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, L.; Sebastiani, G.; Lopez-Bermejo, A.; Díaz, M.; Gómez-Roig, M.D.; De Zegher, F. Gender Specificity of Body Adiposity and Circulating Adiponectin, Visfatin, Insulin, and Insulin Growth Factor-I at Term Birth: Relation to Prenatal Growth. J Clin Endocrin Metabol 2008, 93, 2774–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrand, J.; Nicolescu, R.; Kaguelidou, F.; Verkauskiene, R.; Sibony, O.; Chevenne, D.; Claris, O.; Lévy-Marchal, C. Catch-up Growth Following Fetal Growth Restriction Promotes Rapid Restoration of Fat Mass but without Metabolic Consequences at One Year of Age. PLoS One 2009, 4, e5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mericq, V.; Ong, K.K.; Bazaes, R.; Peña, V.; Avila, A.; Salazar, T.; Soto, N.; Iñiguez, G.; Dunger, D.B. Longitudinal Changes in Insulin Sensitivity and Secretion from Birth to Age Three Years in Small- and Appropriate-for-Gestational-Age Children. Diabetologia 2005, 48, 2609–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertsson-Wikland, K.; Karlberg, J. Natural Growth in Children Born Small for Gestational Age with and without Catch-up Growth. Acta Paediatr 1994, 83, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokken-Koelega, A.C.S.; De Ridder, M.A.J.; Lemmen, R.J.; Hartog, H. Den; De Muinck Keizer-Schrama, S.M.P.F.; Drop, S.L.S. Children Born Small for Gestational Age: Do They Catch Up? Pediatr Res 1995, 38, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, L.; López-Bermejo, A.; Díaz, M.; Marcos, M.V.; Casano, P.; De Zegher, F. Abdominal Fat Partitioning and High-Molecular-Weight Adiponectin in Short Children Born Small for Gestational Age. J Clin Endocrin Metabol 2009, 94, 1049–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geremia, C.; Cianfarani, S. Insulin Sensitivity in Children Born Small for Gestational Age (SGA). Rev Diab Stud 2004, 1, 58–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, C.; Osborn, J.F.; Haass, C.; Natale, F.; Spinelli, M.; Scapillati, E.; Spinelli, A.; Pacifico, L. Ghrelin, Leptin, IGF-1, IGFBP-3, and Insulin Concentrations at Birth: Is There a Relationship with Fetal Growth and Neonatal Anthropometry? Clin Chem 2008, 54, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, H.J.; Ebenbichler, C.F.; Huter, O.; Bodner, J.; Lechleitner, M.; Föger, B.; Patsch, J.R.; Desoye, G. Fetal Leptin and Insulin Levels Only Correlate in Large-for-Gestational Age Infants. Eur J Endocrinol 2000, 142, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalinbas, E.; Binay, C.; Simsek, E.; Aksit, M. The Role of Umbilical Cord Blood Concentration of IGF-I, IGF-II, Leptin, Adiponectin, Ghrelin, Resistin, and Visfatin in Fetal Growth. Am J Perinatol 2019, 36, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christou, H.; Connors, J.M.; Ziotopoulou, M.; Hatzidakis, V.; Papathanassoglou, E.; Ringer, S.A.; Mantzoros, C.S. Cord Blood Leptin and Insulin-like Growth Factor Levels Are Independent Predictors of Fetal Growth. J Clin Endocrin Metabol 2001, 86, 935–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simental-Mendía, L.E.; Castañeda-Chacón, A.; Rodríguez-Morán, M.; Guerrero-Romero, F. Birth-Weight, Insulin Levels, and HOMA-IR in Newborns at Term. BMC Pediatr 2012, 12, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cekmez, F.; Canpolat, F.E.; Pirgon, O.; Çetinkaya, M.; Aydinoz, S.; Suleymanoglu, S.; Ipcioglu, O.M.; Sarici, S.U. Apelin, Vaspin, Visfatin and Adiponectin in Large for Gestational Age Infants with Insulin Resistance. Cytokine 2011, 56, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiavaroli, V.; Cutfield, W.S.; Derraik, J.G.B.; Pan, Z.; Ngo, S.; Sheppard, A.; Craigie, S.; Stone, P.; Sadler, L.; Ahlsson, F. Infants Born Large-for-Gestational-Age Display Slower Growth in Early Infancy, but No Epigenetic Changes at Birth. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 14540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taal, H.R.; Vd Heijden, A.J.; Steegers, E.A.P.; Hofman, A.; Jaddoe, V.W.V. Small and Large Size for Gestational Age at Birth, Infant Growth, and Childhood Overweight. Obesity 2013, 21, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R.K.; Uhing, M.; Goday, P.S. Catch-down Growth in Infants Born Large for Gestational Age. Nutrition in Clinical Practice 2021, 36, 1215–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkawa, N.; Shoji, H.; Ikeda, N.; Suganuma, H.; Shimizu, T. Relationship between Insulin-like Growth Factor 1, Leptin and Ghrelin Levels and Catch-up Growth in Small for Gestational Age Infants of 27–31 Weeks during Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Admission. J Paediatr Child Health 2017, 53, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özkan, H.; Aydın, A.; Demir, N.; Erci, T.; Büyükgebiz, A. Associations of IGF-I, IGFBP-1 and IGFBP-3 on Intrauterine Growth and Early Catch-Up Growth. Biol Neonate 1999, 76, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, Q.; Cao, S.; Pang, J.; Zhang, H.; Feng, T.; Deng, Y.; Yao, J.; Li, H. A Meta-Analysis of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) Use during Prenatal Depression and Risk of Low Birth Weight and Small for Gestational Age. J Affect Disord 2018, 241, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, S.; Mitchell, A.A.; Louik, C.; Werler, M.M.; Chambers, C.D.; Hernández-Díaz, S. Antidepressant Use during Pregnancy and the Risk of Preterm Delivery and Fetal Growth Restriction. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2009, 29, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, M.; Makino, S.; Oguma, K.; Imai, H.; Takamizu, A.; Koizumi, A.; Yoshida, K. Fetal Growth Restriction as the Initial Finding of Preeclampsia Is a Clinical Predictor of Maternal and Neonatal Prognoses: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, S.K.; Edlow, A.G.; Neff, P.M.; Sammel, M.D.; Andrela, C.M.; Elovitz, M.A. Rethinking IUGR in Preeclampsia: Dependent or Independent of Maternal Hypertension? J Perinatol 2009, 29, 680–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-G.; Yang, L.; Qiao, Z.-X.; Guo, W. Effect of Gestational Hypertension on Fetal Growth Restriction, Endocrine and Cardiovascular Disorders. Asian J Surg 2022, 45, 1048–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehested, L.T.; Pedersen, P. Prognosis and Risk Factors for intrauterine Growth Retardation. Dan Med J 2014, 61, A4826. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberg, H.M.; Mercer, B.M.; Catalano, P.M. The Influence of Obesity and Diabetes on the Prevalence of Macrosomia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004, 191, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R. xue; He, X.J.; Hu, C.L. Maternal Pre-Pregnancy Obesity and the Risk of Macrosomia: A Meta-Analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2018, 297, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, R.F.; Abell, S.K.; Ranasinha, S.; Misso, M.; Boyle, J.A.; Black, M.H.; Li, N.; Hu, G.; Corrado, F.; Rode, L.; et al. Association of Gestational Weight Gain with Maternal and Infant Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Assoc 2017, 317, 2207–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlsson, F.; Diderholm, B.; Jonsson, B.; Nordén-Lindberg, S.; Olsson, R.; Ewald, U.; Forslund, A.; Stridsberg, M.; Gustafsson, J. Insulin Resistance, a Link between Maternal Overweight and Fetal Macrosomia in Nondiabetic Pregnancies. Horm Res Paediatr 2010, 74, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emerson, R.W.; Adams, C.; Nishino, T.; Hazlett, H.C.; Wolff, J.J.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Constantino, J.N.; Shen, M.D.; Swanson, M.R.; Elison, J.T.; et al. Functional Neuroimaging of High-Risk 6-Month-Old Infants Predicts a Diagnosis of Autism at 24 Months of Age. Sci Transl Med 2017, 9, eaag2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, E.; Calderoni, S.; Marchi, V.; Muratori, F.; Cioni, G.; Guzzetta, A. Network Over-Connectivity Differentiates Autism Spectrum Disorder from Other Developmental Disorders in Toddlers: A Diffusion MRI Study. Hum Brain Mapp 2017, 38, 2333–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, Q.; Xiao, R.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Jin, B.; Wen, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, H.; et al. A Structural MRI Study of Global Developmental Delay in Infants (<2 Years Old). Front Neurol 2022, 13, 952405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldateli, B.; Silveira, R.C.; Procianoy, R.S.; Belfort, M.; Caye, A.; Leffa, D.; Franz, A.P.; Barros, F.C.; Santos, I.S.; Matijasevich, A.; et al. Association between Preterm Infant Size at 1 Year and ADHD Later in Life: Data from 1993 and 2004 Pelotas Birth Cohorts. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2023, 32, 1589–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J.J.; Swanson, M.R.; Elison, J.T.; Gerig, G.; Pruett, J.R.; Styner, M.A.; Vachet, C.; Botteron, K.N.; Dager, S.R.; Estes, A.M.; et al. Neural Circuitry at Age 6 Months Associated with Later Repetitive Behavior and Sensory Responsiveness in Autism. Mol Autism 2017, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Xu, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, C. Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 Has the Potential to Be Used as a Diagnostic Tool and Treatment Target for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Cureus 2024, 16, e65393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dönmez, B.; Erbakan, K.; Erbaş, O. The Role of Insulin-like Growth Factor on Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Exp Basic Med Sci 2021, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, A.H.; Vahdatpour, C.; Sanfeliu, A.; Tropea, D. The Role of Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) in Brain Development, Maturation and Neuroplasticity. Neuroscience 2016, 325, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.P.; Yuen, G.; Placantonakis, D.G.; Vu, T.; Haiss, F.; O’Hearn, E.; Molliver, M.E.; Aicher, S.A. Why Do Purkinje Cells Die so Easily after Global Brain Ischemia? Aldolase C, EAAT4, and the Cerebellar Contribution to Posthypoxic Myoclonus. Adv Neurol 2002, 89, 331–359. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Xiao, G.-Y.; He, C.-Y.; Liu, X.; Fan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, N.-R. Serum Levels of Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 and Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein-3 in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Chin J Contempor Pediatr 2022, 24, 186–191. [Google Scholar]

- Anlar, B.; Oktem, F.; Bakkaloglu, B.; Haliloglu, M.; Oguz, H.; Unal, F.; Pehlivanturk, B.; Gokler, B.; Ozbesler, C.; Yordam, N. Urinary Epidermal and Insulin-Like Growth Factor Excretion in Autistic Children. Neuropediatrics 2007, 38, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.L.; Hediger, M.L.; Molloy, C.A.; Chrousos, G.P.; Manning-Courtney, P.; Yu, K.F.; Brasington, M.; England, L.J. Elevated Levels of Growth-Related Hormones in Autism and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007, 67, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, F.; Isık, Ü.; Aktepe, E.; Kılıc, F.; Sirin, F.B.; Bozkurt, M. Comparison of Serum VEGF, IGF-1, and HIF-1α Levels in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Healthy Controls. J Autism Dev Disord 2021, 51, 3564–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedini, M.; Mashayekhi, F.; Salehi, Z. Analysis of Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 Serum Levels and Promoter (Rs12579108) Polymorphism in the Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Clin Neurosci 2022, 99, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courchesne, E.; Campbell, K.; Solso, S. Brain Growth across the Life Span in Autism: Age-Specific Changes in Anatomical Pathology. Brain Res 2011, 1380, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jong, M.; Cranendonk, A.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Van Weissenbruch, M.M. IGF-I and Relation to Growth in Infancy and Early Childhood in Very-Low-Birth-Weight Infants and Term Born Infants. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0171650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, M.R.; Ziegler, D.A.; Makris, N.; Filipek, P.A.; Kemper, T.L.; Normandin, J.J.; Sanders, H.A.; Kennedy, D.N.; Caviness, V.S. Localization of White Matter Volume Increase in Autism and Developmental Language Disorder. Ann Neurol 2004, 55, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, J.; Ismail, L.C.; Victora, C.G.; Ohuma, E.O.; Bertino, E.; Altman, D.G.; Lambert, A.; Papageorghiou, A.T.; Carvalho, M.; Jaff, Y.A.; et al. International Standards for Newborn Weight, Length, and Head Circumference by Gestational Age and Sex: The Newborn Cross-Sectional Study of the INTERGROWTH-21 St Project. Lancet 2014, 384, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkin, T.J.; Murphy, M.J. The Gender Insulin Hypothesis: Why Girls Are Born Lighter than Boys, and the Implications for Insulin Resistance. Int J Obes 2006, 30, 1056–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durston, S.; Hulshoff Pol, H.E.; Casey, B.J.; Giedd, J.N.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Van Engeland, H. Anatomical MRI of the Developing Human Brain: What Have We Learned? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001, 40, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paus, T. Sex Differences in the Human Brain: A Developmental Perspective. Prog Brain Res 2010, 186, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethlehem, R.A.I.; Seidlitz, J.; White, S.R.; Vogel, J.W.; Anderson, K.M.; Adamson, C.; Adler, S.; Alexopoulos, G.S.; Anagnostou, E.; Areces-Gonzalez, A.; et al. Brain Charts for the Human Lifespan. Nature 2022, 604, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geary, M.P.P.; Pringle, P.J.; Rodeck, C.H.; Kingdom, J.C.P.; Hindmarsh, P.C. Sexual Dimorphism in the Growth Hormone and Insulin-like Growth Factor Axis at Birth. J Clin Endocrin Metabol 2003, 88, 3708–3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yüksel, B.; Özbek, M.N.; Mungan, N.Ö.; Darendeliler, F.; Budan, B.; Bideci, A.; Çetinkaya, E.; Berberoǧlu, M.; Evliyaoǧlu, O.; Yeflilkaya, E.; et al. Serum IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 Levels in Healthy Children between 0 and 6 Years of Age. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 2011, 3, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chellakooty, M.; Juul, A.; Boisen, K.A.; Damgaard, I.N.; Kai, C.M.; Schmidt, I.M.; Petersen, J.H.; Skakkebæk, N.E.; Main, K.M. A Prospective Study of Serum Insulin-like Growth Factor I (IGF-I) and IGF-Binding Protein-3 in 942 Healthy Infants: Associations with Birth Weight, Gender, Growth Velocity, and Breastfeeding. J Clin Endocrin Metabol 2006, 91, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, R.C.; King, W.D.; Winkler, M.K.; Fowlkes, J.L. Early Developmental Changes in IGF-I, IGF-II, IGF Binding Protein-1, and IGF Binding Protein-3 Concentration in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Children. Pediatr Res 2005, 58, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, B.M.; Knight, B.; Hopper, H.; Hill, A.; Powell, R.J.; Hattersley, A.T.; Clark, P.M. Measurement of Cord Insulin and Insulin-Related Peptides Suggests That Girls Are More Insulin Resistant than Boys at Birth. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 2661–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Qiu, Y.; Li, Y.; Cong, X. Genetics of Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Transl Psychiatry 2022, 12, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zur, R.L.; Kingdom, J.C.; Parks, W.T.; Hobson, S.R. The Placental Basis of Fetal Growth Restriction. Obstetr Gynecol Clin 2020, 47, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surico, D.; Bordino, V.; Cantaluppi, V.; Mary, D.; Gentilli, S.; Oldani, A.; Farruggio, S.; Melluzza, C.; Raina, G.; Grossini, E. Preeclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Restriction: Role of Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Trophoblast Crosstalk. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0218437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinthorsdottir, V.; McGinnis, R.; Williams, N.O.; Stefansdottir, L.; Thorleifsson, G.; Shooter, S.; Fadista, J.; Sigurdsson, J.K.; Auro, K.M.; Berezina, G.; et al. Genetic Predisposition to Hypertension Is Associated with Preeclampsia in European and Central Asian Women. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 5976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiarotti, F.; Venerosi, A. Epidemiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Review of Worldwide Prevalence Estimates since 2014. Brain Sci 2020, 10, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depastas, C.; Kalaitzaki, A. The Epidemiology of Autism Spectrum Disorder and Factors Contributing to the Increase in Its Prevalence. Arch Hellen Med 2022, 39, 308–312. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Xie, X.; Yuan, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, H. Epidemiological Trends of Maternal Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy at the Global, Regional, and National Levels: A Population-based Study. BMC Preg Childbirth 2021, 21, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horgan, R.; Monteith, C.; McSweeney, L.; Ritchie, R.; Dicker, P.; EL-Khuffash, A.; Malone, F.D.; Kent, E. The Emergence of a Change in the Prevalence of Preeclampsia in a Tertiary Maternity Unit (2004–2016). J Matern Fetal Neonat Med 2022, 35, 3129–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, N.A.; Everitt, I.; Seegmiller, L.E.; Yee, L.M.; Grobman, W.A.; Khan, S.S. Trends in the Incidence of New-Onset Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy Among Rural and Urban Areas in the United States, 2007 to 2019. J Am Heart Assoc 2022, 11, e023791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, K.K.; Harrington, K.; Cameron, N.A.; Petito, L.C.; Powe, C.E.; Landon, M.B.; Grobman, W.A.; Khan, S.S. Trends in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus among Nulliparous Pregnant Individuals with Singleton Live Births in the United States between 2011 to 2019: An Age-Period-Cohort Analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2023, 5, 100785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.C.; Freaney, P.M.; Perak, A.M.; Greenland, P.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Grobman, W.A.; Khan, S.S. Trends in Prepregnancy Obesity and Association with Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in the United States, 2013 to 2018. J Am Heart Assoc 2021, 10, e020717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, S.C.; Kim, S.Y.; Sharma, A.J.; Rochat, R.; Morrow, B. Is Obesity Still Increasing among Pregnant Women? Prepregnancy Obesity Trends in 20 States, 2003-2009. Prev Med (Baltim) 2013, 56, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baraban, E.; McCoy, L.; Simon, P. Increasing Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes and Pregnancy-Related Hypertension in Los Angeles County, California, 1991–2003. Prev Chronic Dis 2008, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Vishram, J.K.K.; Borglykke, A.; Andreasen, A.H.; Jeppesen, J.; Ibsen, H.; Jørgensen, T.; Palmieri, L.; Giampaoli, S.; Donfrancesco, C.; Kee, F.; et al. Impact of Age and Gender on the Prevalence and Prognostic Importance of the Metabolic Syndrome and Its Components in Europeans. the MORGAM Prospective Cohort Project. PLoS One 2014, 9, e107294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildrum, B.; Mykletun, A.; Hole, T.; Midthjell, K.; Dahl, A.A. Age-Specific Prevalence of the Metabolic Syndrome Defined by the International Diabetes Federation and the National Cholesterol Education Program: The Norwegian HUNT 2 Study. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wei, T.; Ni, W.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, J.; Xing, Y.; Xing, Q. Incidence and Risk Factors of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Prospective Cohort Study in Qingdao, China. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020, 11, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahratian, A. Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity among Women of Childbearing Age: Results from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Matern Child Health J 2009, 13, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztan, O.; Garner, J.P.; Constantino, J.N.; Parker, K.J. Neonatal CSF Vasopressin Concentration Predicts Later Medical Record Diagnoses of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 10609–10613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).