Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Methods

Study Design

Setting

Participants

Variables and Data Measurement

Study Size

Statistical Analysis

Ethics Consideration

Results

Characteristics of the Study Group

Patients' Expectations

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | See further datalis: https://panelariadna.pl/regulamin.pdf?v=10052024

|

| 2 | PRACTA is a Polish-Norwegian research project whose aim was to activate older people in medical practice. The study consisted of a baseline questionnaire, implementation of the intervention, and a follow-up questionnaire administered 1 month after the intervention. |

References

- Chassin, M.R. The Urgent Need to Improve Health Care Quality—Institute of Medicine National Roundtable on Health Care Quality. JAMA, 1998, 280(11), 1000. [CrossRef]

- Krot, K. Quality and Marketing of Medical Services; Wolters Kluwer Polska: Warsaw, Poland, 2021.

- Kędra, E.; Chudak, B. Quality of Medical Services and Medical Effectiveness. Public Health Nursing, 2011, 1(1).

- Kurji, Z.; Shaheen, Z.; Mithani, Y. Review and Analysis of Quality Healthcare System Enhancement in Developing Countries. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc., 2015, 65(7), 776–781.

- Brown, A. Communication and Leadership in Healthcare Quality Governance: Findings from Comparative Case Studies of Eight Public Hospitals in Australia. J. Health Organ. Manag., 2020, 34(2), 144–161. [CrossRef]

- Mühlbacher, A.; Stolk, E. Patient-Reported Satisfaction, Experiences, and Preferences: Same but Different? Value Health, 2023, 26(1), 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Hoff, T.; Prout, K.; Carabetta, S. How Teams Impact Patient Satisfaction: A Review of the Empirical Literature. Health Care Manag. Rev., 2021, 46(1), 75. [CrossRef]

- Maślach, D.; Karczewska, B.; Szpak, A.; Charkiewicz, A.; Krzyżak, M. Does Place of Residence Affect Patient Satisfaction with Hospital Health Care? Ann. Agric. Environ. Med., 2020, 27(1), 86–90. [CrossRef]

- Świątoniowska-Lonc, N.; Polański, J.; Tański, W.; Jankowska-Polańska, B. Impact of Satisfaction with Physician–Patient Communication on Self-Care and Adherence in Patients with Hypertension: Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Health Serv. Res., 2020, 20(1), 1046. [CrossRef]

- Arraras, J.I.; Giesinger, J.; Shamieh, O.; et al. Cancer Patient Satisfaction with Health Care Professional Communication: An International EORTC Study. Psychooncology, 2022, 31(3), 541–547. [CrossRef]

- Ćwik, K. The Impact of Quality Management Systems on the Efficiency of Public Hospital Services in Poland; Department of Macroeconomics, 2024. Available online: https://repozytorium.bg.ug.edu.pl/info/phd/UOGf58bc44d40f044048b1a1b8161629b5f/ (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Act of 16 June 2023 on Quality in Health Care and Patient Safety.

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and Elaboration. Int. J. Surg., 2014, 12(12), 1500–1524. [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G. Improving the Quality of Web Surveys: The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J. Med. Internet Res., 2004, 6(3), e132. [CrossRef]

- Krot, K. Trust in the Doctor-Patient Relationship: Implications for Healthcare Facility Management; CeDeWu: Warsaw, Poland, 2019.

- Donabedian, A. Evaluating the Quality of Medical Care. Milbank Q., 2005, 83(4), 691–729. [CrossRef]

- Pawelczyk, K.; Maniecka-Bryła, I.; Targowski, M.; Samborska-Sablik, A. Patient Satisfaction as One of the Indicators of Healthcare Quality: A Case Study of a Primary Care Clinic. Acta Clin. Morphol., 2006, 3, 20–21.

- Andaleeb, S.S. Service Quality Perceptions and Patient Satisfaction: A Study of Hospitals in a Developing Country. Soc. Sci. Med., 2001, 52(9), 1359–1370. [CrossRef]

- Zineldin, M. The Quality of Health Care and Patient Satisfaction: An Exploratory Investigation of the 5Qs Model at Some Egyptian and Jordanian Medical Clinics. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur., 2006, 19(1), 60–92. [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Lee, H.; Kim, C.; Lee, S. The Service Quality Dimensions and Patient Satisfaction Relationships in South Korea: Comparisons Across Gender, Age, and Types of Service. J. Serv. Mark., 2005, 19(3), 140–149. [CrossRef]

- Van Den Assem, B.; Dulewicz, V. Doctors’ Trustworthiness, Practice Orientation, Performance, and Patient Satisfaction. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur., 2015, 28(1), 82–95. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.M.; Russell, R.S.; White, S.W. Perceptions of Care Quality and the Effect on Patient Satisfaction. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag., 2016, 33(8), 1202–1229. [CrossRef]

- Naoum, S.; Konstantinidis, T.I.; Spinthouri, M.; Mitseas, P.; Sarafis, P. Patient Satisfaction and Physician Empathy at a Hellenic Air Force Health Service. Mil. Med., 2021, 186(9–10), 1029–1036. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.R. Patient Views on Quality Care in General Practice: Literature Review. Soc. Sci. Med., 1994, 39(5), 655–670. [CrossRef]

- Gabel, L.L.; Lucas, J.B.; Westbury, R.C. Why Do Patients Continue to See the Same Physician? Fam. Pract. Res. J., 1993, 13(2), 133–147.

- Hashim, M.J. Patient-Centered Communication: Basic Skills. Am. Fam. Physician, 2017, 95(1), 29–34.

- Bradshaw, A.; Raphaelson, S. Improving Patient Satisfaction with Wait Times. Nursing2024, 2021, 51(4), 67. [CrossRef]

- Dansky, K.H.; Miles, J. Patient Satisfaction with Ambulatory Healthcare Services: Waiting Time and Filling Time. J. Healthc. Manag., 1997, 42(2), 165.

- Piekutowski, J. Migration: An Untapped (for Now) Opportunity for Poland; Warsaw Enterprise Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 2023. Available online: https://wei.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Migracje-niewykorzystana-na-razie-szansa-Polski-raport.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Govere, L.; Govere, E.M. How Effective is Cultural Competence Training of Healthcare Providers on Improving Patient Satisfaction of Minority Groups? A Systematic Review of Literature. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs., 2016, 13(6), 402–410. [CrossRef]

- Wlodarczyk, D.; Chylińska, J.; Lazarewicz, M.; et al. Enhancing Doctors’ Competencies in Communication with and Activation of Older Patients: The Promoting Active Aging (PRACTA) Computer-Based Intervention Study. J. Med. Internet Res., 2017, 19(2), e45. [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, M.; Rzadkiewicz, M.; Adamus, M.; et al. Primary Care Patients’ Expectations Regarding Medical Appointments and Their Experiences During a Visit: Does Age Matter? Patient Prefer. Adherence, 2017, 11, 1221–1233. [CrossRef]

- Mühlbacher, A.; Stolk, E. Patient-Reported Satisfaction, Experiences, and Preferences: Same but Different? Value Health, 2023, 26(1), 1–3. [CrossRef]

| Category | Subcategory | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 406 | 56.00 |

| Male | 319 | 44.00 | |

| Age | 18-24 years | 80 | 11.03 |

| 25-34 years | 142 | 19.59 | |

| 35-44 years | 106 | 14.62 | |

| 45-54 years | 131 | 18.07 | |

| 55+ years | 266 | 36.69 | |

| Marital status | Miss/Bachelor | 142 | 19.59 |

| Separated/divorced | 62 | 8.55 | |

| Widower | 31 | 4.28 | |

| A marriage | 490 | 67.59 | |

| Education | Primary | 20 | 2.76 |

| Vocational | 60 | 8.28 | |

| Secondary school, no final exams | 93 | 12.83 | |

| Secondary school, with exam | 261 | 36.00 | |

| Higher | 291 | 40.14 | |

| Domicile | Very big city (500+ thousand) | 100 | 13.79 |

| Big city (100-500 thousand) | 130 | 17.93 | |

| Average city (20-99 thousand) | 152 | 20.97 | |

| Small city (do 20 thousand) | 86 | 11.86 | |

| Village | 257 | 35.45 | |

| Lives with:* | Alone | 87 | 12.00 |

| Spouse | 467 | 64.41 | |

| Children | 251 | 34.62 | |

| Grandchildren | 14 | 1.93 | |

| Others members of family | 170 | 23.45 | |

| Other persons | 15 | 2.07 | |

| Working person | 455 | 62.76 | |

| Financial situation | Good | 38 | 5.24 |

| Rather good | 173 | 23.86 | |

| Average | 379 | 52.28 | |

| Rather bad | 94 | 12.97 | |

| Bad | 41 | 5.66 | |

| Current health status | Very good | 21 | 2.90 |

| Good | 279 | 38.48 | |

| Average | 305 | 42.07 | |

| Bad | 106 | 14.62 | |

| Very bad | 14 | 1.93 | |

| Number of diseases | None | 178 | 24.55 |

| 1 disease | 237 | 32.69 | |

| 2 diseases | 177 | 24.41 | |

| 3 diseases | 94 | 12.97 | |

| More | 39 | 5.38 | |

| Type of visit | POZ/ family medicine | 327 | 45.10 |

| AOS/ specialised healthcare | 398 | 54.90 | |

| Category | Subcategory | Sum (M ± SD) |

p-value (sum) | Overall rating (M ± SD) | p-value (overall rating) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 80.43 ± 19.20 | 0.98 | 7.37 ± 2.48 | 0.62 |

| Male | 80.46 ± 18.85 | 7.46 ± 2.16 | |||

| Age | 18-24 years | 78.75 ± 20.13 | 0.25 | 7.11 ± 2.37 | 0.29 |

| 25-34 years | 80.04 ± 20.44 | 7.25 ± 2.19 | |||

| 35-44 years | 81.46 ± 16.84 | 7.47 ± 2.18 | |||

| 45-54 years | 77.82 ± 18.75 | 7.27 ± 2.44 | |||

| 55+ years | 82.06 ± 18.83 | 7.64 ± 2.41 | |||

| Marital status | Miss/Bachelor | 77.51 ± 20.20 | 0.08 | 7.11 ± 2.37 | 0.13 |

| Separated/divorced | 84.89 ± 20.47 | 7.94 ± 2.38 | |||

| Widower | 81.23 ± 18.42 | 7.58 ± 2.66 | |||

| A marriage | 80.68 ± 18.46 | 7.42 ± 2.30 | |||

| Education | Primary | 81.45 ± 17.86 | 0.73 | 7.90 ± 2.17 | 0.64 |

| Vocational | 79.77 ± 21.76 | 7.43 ± 2.26 | |||

| Secondary school, no final exams | 81.91 ± 19.13 | 7.46 ± 2.11 | |||

| Secondary school, with exam | 79.26 ± 19.21 | 7.25 ± 2.49 | |||

| Higher | 81.11 ± 18.38 | 7.50 ± 2.30 | |||

| Domicile | Very big city (500+ thousand) | 79.52 ± 18.31 | 0.76 | 7.28 ± 2.47 | 0.57 |

| Big city (100-500 thousand) | 80.80 ± 20.36 | 7.18 ± 2.46 | |||

| Average city (20-99 thousand) | 78.96 ± 17.78 | 7.44 ± 2.15 | |||

| Small city (do 20 thousand) | 81.65 ± 20.00 | 7.67 ± 2.27 | |||

| Village | 81.10 ± 19.09 | 7.48 ± 2.37 | |||

| He lives alone | No | 80.74 ± 18.71 | 0.26 | 7.46 ± 2.29 | 0.16 |

| Yes | 78.28 ± 21.24 | 7.08 ± 2.67 | |||

| He lives with his spouse | No | 79.21 ± 20.94 | 0.19 | 7.31 ± 2.49 | 0.36 |

| Yes | 81.13 ± 17.89 | 7.47 ± 2.25 | |||

| Lives with children | No | 80.39 ± 19.79 | 0.91 | 7.34 ± 2.41 | 0.24 |

| Yes | 80.56 ± 17.56 | 7.55 ± 2.19 | |||

| He lives with his grandchildren | No | 80.50 ± 19.08 | 0.61 | 7.41 ± 2.34 | 0.71 |

| Yes | 77.86 ± 17.37 | 7.64 ± 2.56 | |||

| He lives with other family members | No | 79.98 ± 18.23 | 0.23 | 7.34 ± 2.31 | 0.16 |

| Yes | 81.96 ± 21.46 | 7.64 ± 2.43 | |||

| He lives with other people | No | 80.41 ± 19.05 | 0.73 | 7.40 ± 2.35 | 0.52 |

| Yes | 82.13 ± 18.85 | 7.80 ± 1.47 | |||

| Working person | No | 81.17 ± 19.96 | 0.43 | 7.43 ± 2.32 | 0.51 |

| Yes | 80.02 ± 18.48 | 7.18 ± 2.69 | |||

| Financial situation | Good | 83.39 ± 19.43 | 0.21 | 7.42 ± 2.48 | 0.01 |

| Rather good | 81.35 ± 18.00 | 7.75 ± 2.11 | |||

| Average | 80.18 ± 19.49 | 7.43 ± 2.27 | |||

| Rather bad | 77.06 ± 16.87 | 6.64 ± 2.66 | |||

| Bad | 84.05 ± 22.64 | 7.59 ± 2.70 | |||

| Current health status | Very good | 80.81 ± 18.12 | 0.66 | 7.52 ± 2.23 | 0.11 |

| Good | 81.49 ± 18.45 | 7.58 ± 2.15 | |||

| Average | 79.60 ± 19.14 | 7.32 ± 2.35 | |||

| Bad | 80.70 ± 19.92 | 7.39 ± 2.62 | |||

| Very bad | 75.57 ± 23.53 | 5.93 ± 3.27 | |||

| Number of diseases | None | 77.75 ± 18.89 | 0.19 | 7.11 ± 2.31 | 0.36 |

| 1 disease | 80.45 ± 18.87 | 7.51 ± 2.21 | |||

| 2 diseases | 82.54 ± 19.69 | 7.55 ± 2.34 | |||

| 3 diseases | 81.71 ± 18.24 | 7.40 ± 2.62 | |||

| More | 80.15 ± 19.06 | 7.62 ± 2.50 | |||

| Type of visit | POZ | 77.52 ± 19.04 | <0.001 | 7.20 ± 2.30 | 0.03 |

| AOS | 82.85 ± 18.71 | 7.59 ± 2.36 |

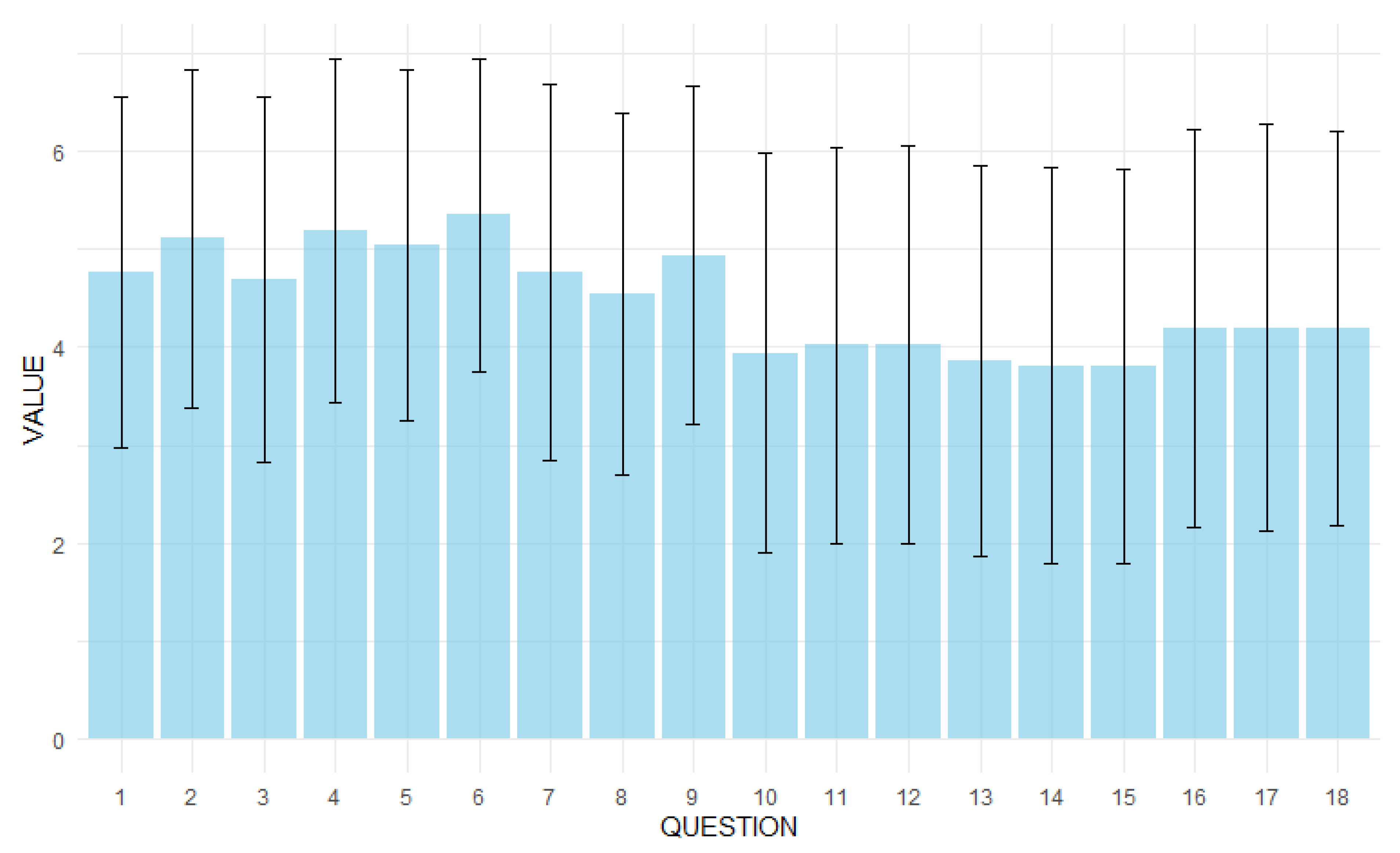

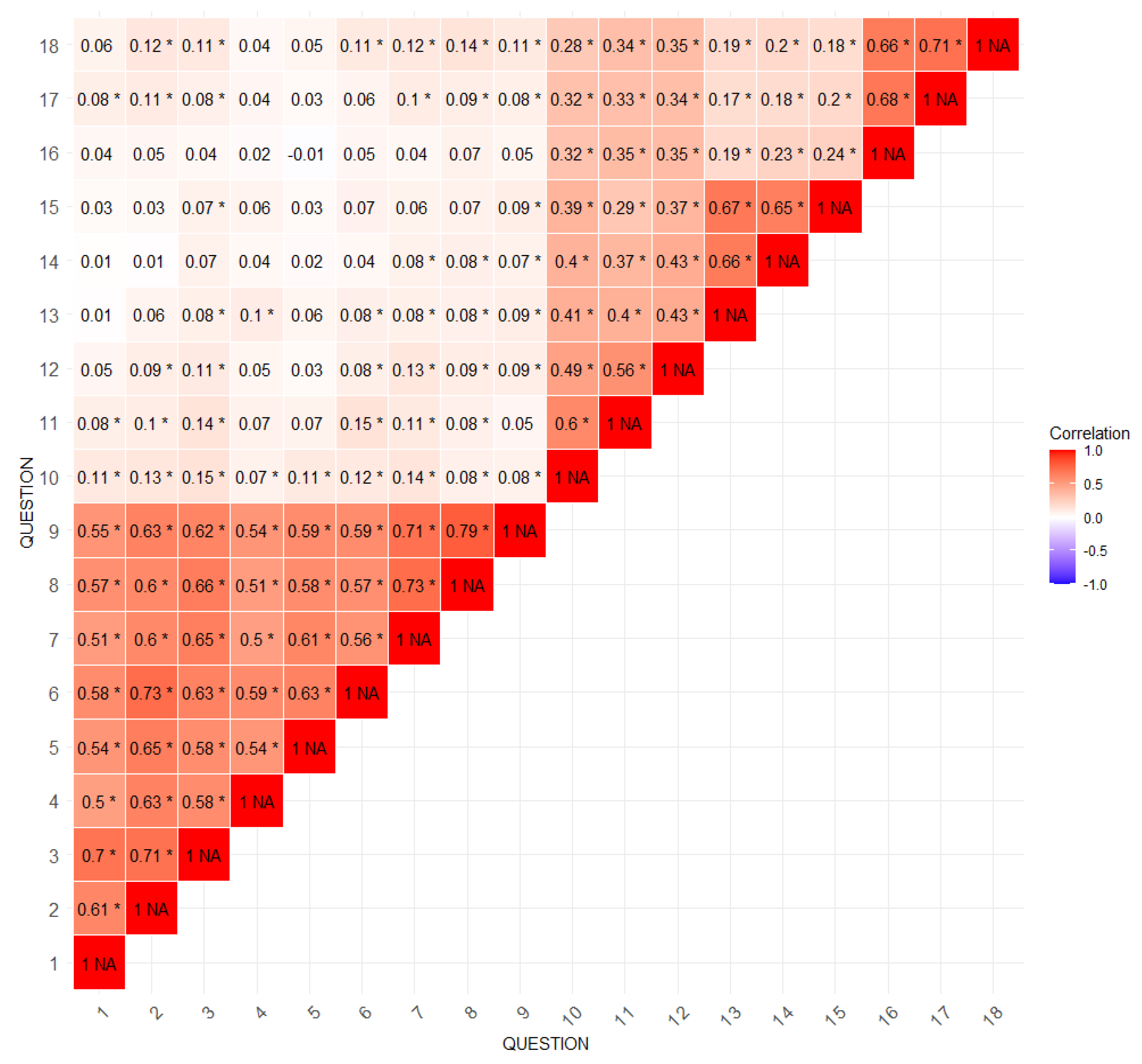

| During the visit, the doctor: | AOS M ± SD |

POZ M ± SD |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| found the cause of my symptoms | 4.85 ± 1.85 | 4.68 ± 1.70 | 0.071 |

| presented me a probable further course of treatment | 5.38 ± 1.66 | 4.79 ± 1.76 | 0.000 |

| discussed the possible consequences of the disease | 4.87 ± 1.85 | 4.46 ± 1.86 | 0.002 |

| presented the results of the research conducted | 5.51 ± 1.62 | 4.80 ± 1.84 | 0.000 |

| he gave me advice about the medicines I take | 5.18 ± 1.79 | 4.87 ± 1.79 | 0.008 |

| presented treatment recommendations | 5.59 ± 1.49 | 5.06 ± 1.68 | 0.000 |

| he talked to me about how I was feeling and how I was coping | 4.97 ± 1.87 | 4.52 ± 1.95 | 0.001 |

| he encouraged me | 4.70 ± 1.87 | 4.34 ± 1.81 | 0.004 |

| he showed me concern | 5.15 ± 1.69 | 4.69 ± 1.76 | 0.000 |

| he talked to me about what was harmful to my health | 4.11 ± 2.03 | 3.75 ± 2.04 | 0.018 |

| advised me what I could do to improve my functioning in everyday life | 4.14 ± 2.04 | 3.87 ± 1.99 | 0.078 |

| encouraged me to introduce favourable changes | 4.13 ± 2.01 | 3.90 ± 2.06 | 0.141 |

| he suggested how to maintain contacts with other people | 3.87 ± 2.01 | 3.84 ± 2.00 | 0.835 |

| he talked to me about how I can spend my time actively | 3.72 ± 2.00 | 3.91 ± 2.04 | 0.216 |

| told how to maintain life satisfaction | 3.73 ± 1.98 | 3.91 ± 2.04 | 0.232 |

| he was kind towards me | 4.31 ± 2.03 | 4.04 ± 2.01 | 0.077 |

| he treated me seriously | 4.36 ± 2.06 | 4.00 ± 2.09 | 0.022 |

| he showed me respect | 4.23 ± 1.99 | 4.09 ± 2.03 | 0.196 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).