Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

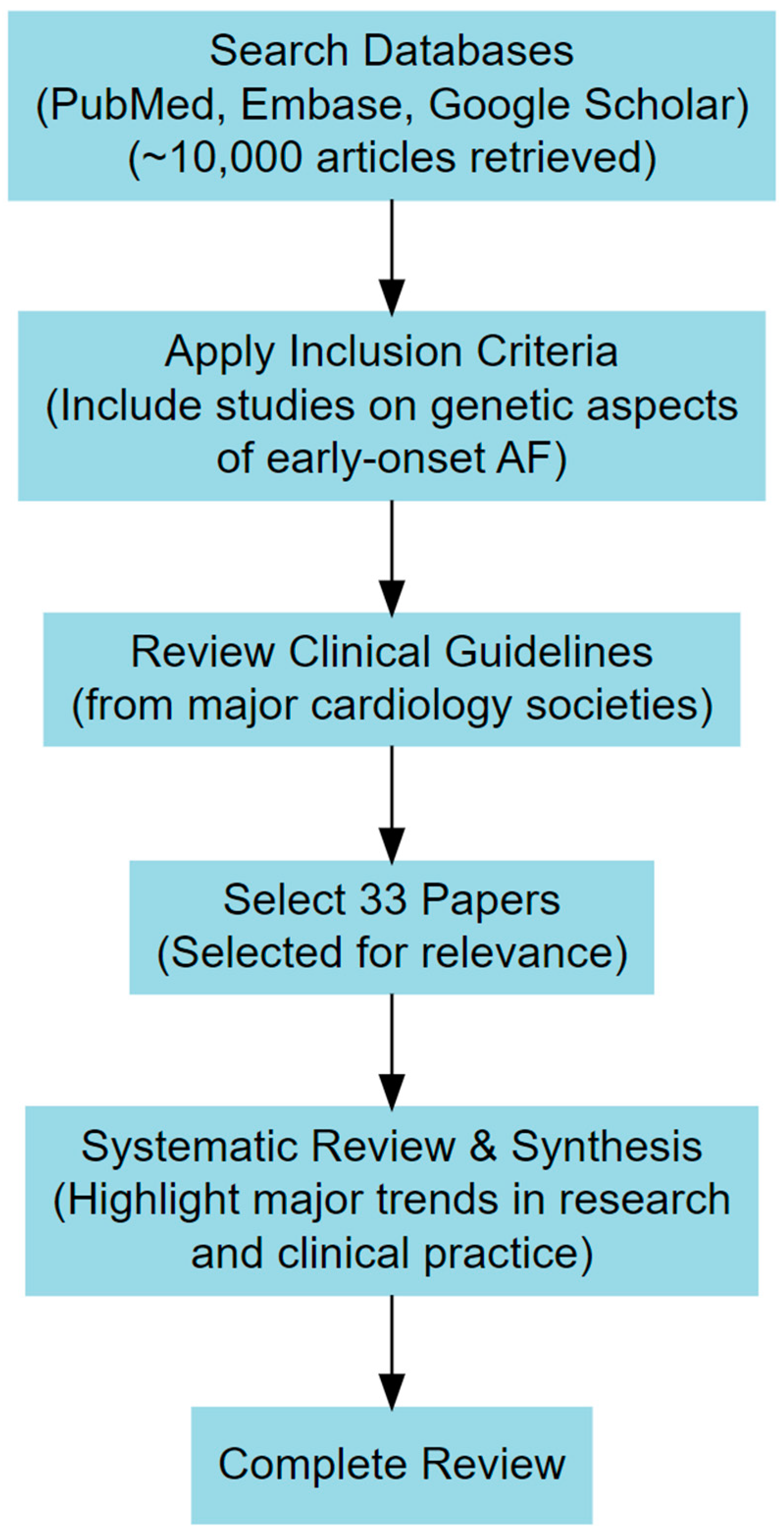

2. Materials and Methods

3. Clinical and Genetic Landscape of Early-Onset Atrial Fibrillation

4. Atrial Cardiomyopathy and Early Onset Atrial Fibrillation

5. Current Guideline Recommendation on Genetic Testing in Atrial Fibrillation

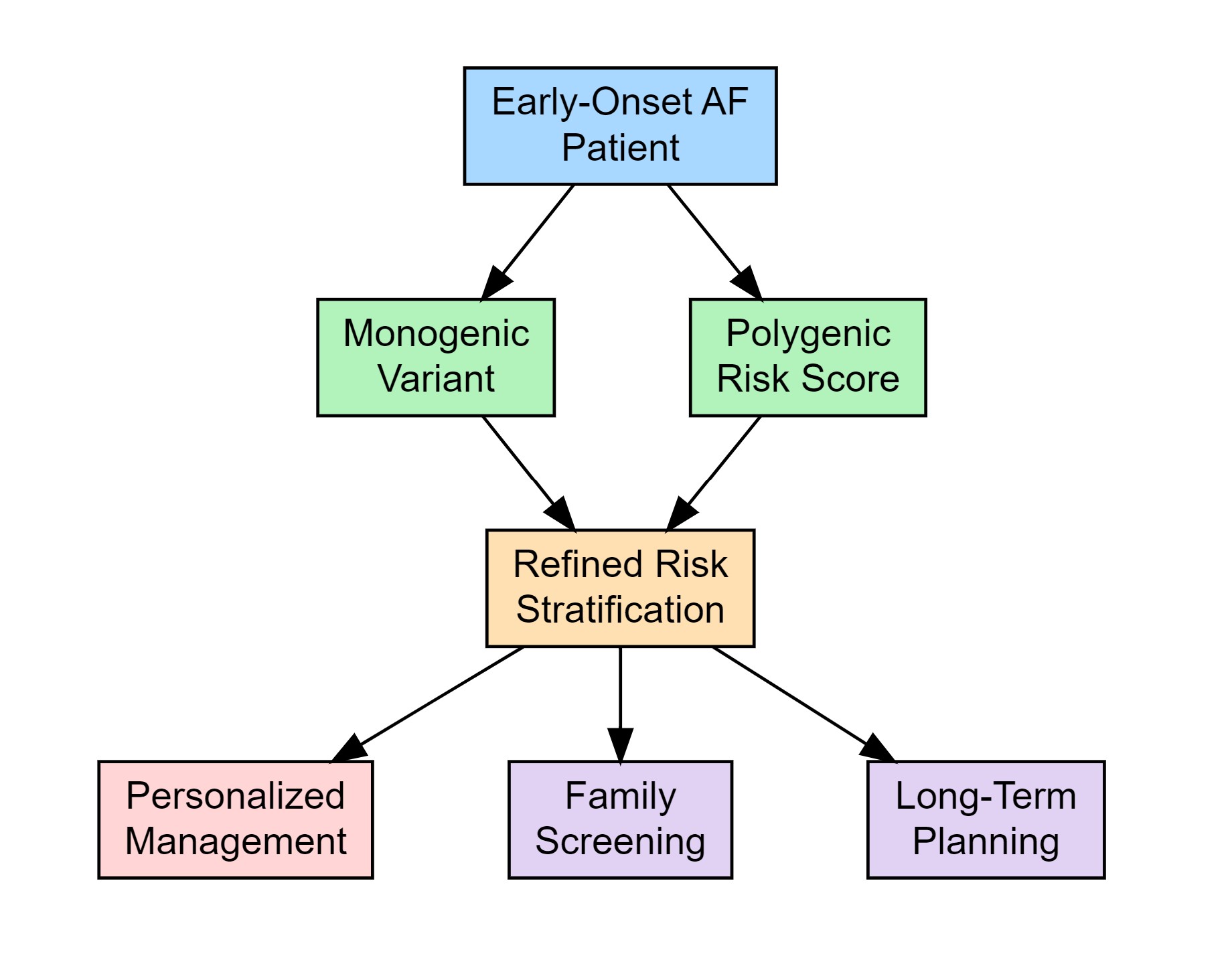

6. Clinical Implications of Genetic Testing

7. Challenges, Limitations, and Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

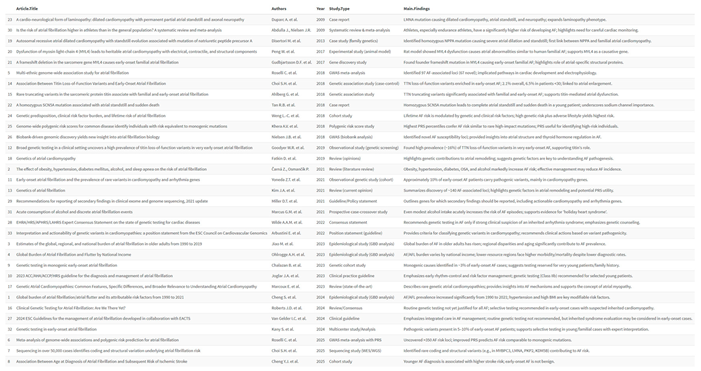

References

- Shantsila E, Choi EK, Lane DA, Joung B, Lip GYH. Atrial fibrillation: comorbidities, lifestyle, and patient factors. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2024;37:100784. Published 2024 Feb 1. [CrossRef]

- Čarná Z, Osmančík P. The effect of obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, alcohol, and sleep apnea on the risk of atrial fibrillation. Physiol Res. 2021 Dec 30;70(Suppl4):S511-S525. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jiao M, Liu C, Liu Y, Wang Y, Gao Q, Ma A. Estimates of the global, regional, and national burden of atrial fibrillation in older adults from 1990 to 2019: insights from the Global Burden of Disease study 2019. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1137230. Published 2023 Jun 12. [CrossRef]

- Ohlrogge AH, Brederecke J, Schnabel RB. Global Burden of Atrial Fibrillation and Flutter by National Income: Results From the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Database. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023 Sep 5;12(17):e030438. [CrossRef]

- 5. Roselli C, Chaffin MD, Weng LC, Aeschbacher S, Ahlberg G, Albert CM, et al. Multi-ethnic genome-wide association study for atrial fibrillation. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1225–33. [CrossRef]

- Roselli C, Surakka I, Olesen MS, Sveinbjornsson G, Marston NA, Choi SH, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide associations and polygenic risk prediction for atrial fibrillation in more than 180,000 cases. Nat Genet. 2025 Mar;57(3):539-547. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H., Jurgens, S.J., Xiao, L. et al. Sequencing in over 50,000 cases identifies coding and structural variation underlying atrial fibrillation risk. Nat Genet 57, 548–562 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Yun-Jiu Cheng, Hai Deng, Hui-Qiang Wei, Wei-Dong Lin, Zhuomin Liang, Yili Chen et al. Association Between Age at Diagnosis of Atrial Fibrillation and Subsequent Risk of Ischemic Stroke. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2025;14(4). [CrossRef]

- Chalazan, B. , Freeth, E., Mohajeri, A. et al. Genetic testing in monogenic early-onset atrial fibrillation. Eur J Hum Genet 31, 769–775 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, Benjamin EJ, Chyou JY, Cronin EM, et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2023;149:e1–156. [CrossRef]

- Yoneda ZT, Anderson KC, Quintana JA, et al. Early-onset atrial fibrillation and the prevalence of rare variants in cardiomyopathy and arrhythmia genes. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6:1371–1379.

- Goodyer WR, Dunn K, Caleshu C, et al. Broad genetic testing in a clinical setting uncovers a high prevalence of titin loss-of-function variants in very early onset atrial fibrillation. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2019;12:e002713.

- Kim JA, Chelu MG, Li N. Genetics of atrial fibrillation. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2021;36(3):281–287. [CrossRef]

- Choi SH, Weng LC, Roselli C, et al. Association Between Titin Loss-of-Function Variants and Early-Onset Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2018;320(22):2354–2364.

- Yoneda ZT, Anderson KC, Ye F, Quintana JA, O'Neill MJ, Sims RA, et al. Mortality Among Patients With Early-Onset Atrial Fibrillation and Rare Variants in Cardiomyopathy and Arrhythmia Genes. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7(7):733–741. [CrossRef]

- Fatkin D, Huttner IG, Johnson R. Genetics of atrial cardiomyopathy. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2019;34:275–81.

- Disertori M, Quintarelli S, Grasso M, et al. Autosomal recessive atrial dilated cardiomyopathy with standstill evolution associated with mutation of natriuretic peptide precursor A. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013;6:27–36.

- Peng W, Li M, Li H, et al. Dysfunction of myosin light-chain 4 (MYL4) leads to heritable atrial cardiomyopathy with electrical, contractile, and structural components: evidence from genetically-engineered rats. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e007030.

- Gudbjartsson DF, Holm H, Sulem P, et al. A frameshift deletion in the sarcomere gene MYL4 causes early-onset familial atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:27–34.

- Tan RB, Gando I, Bu L, et al. A homozygous SCN5A mutation associated with atrial standstill and sudden death. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Duparc A, Cintas P, Somody E, et al. A cardio-neurological form of laminopathy: dilated cardiomyopathy with permanent partial atrial standstill and axonal neuropathy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009;32:410–415.

- Ahlberg G, Refsgaard L, Lundegaard PR, et al. Rare truncating variants in the sarcomeric protein titin associate with familial and early-onset atrial fibrillation. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4316. [CrossRef]

- Weng LC, Preis SR, Hulme OL, et al. Genetic predisposition, clinical risk factor burden, and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2018;137:1027–1038.

- Khera AV, Chaffin M, Aragam KG, et al. Genome-wide polygenic risk scores for common disease identify individuals with risk equivalent to monogenic mutations. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1219–1224.

- Nielsen JB, Thorolfsdottir RB, Fritsche LG, et al. Biobank-driven genomic discovery yields new insight into atrial fibrillation biology. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1234–1239.

- Van Gelder IC, Rienstra M, Bunting KV, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2024;45(36):3314–3414. [CrossRef]

- Wilde AAM, Semsarian C, Márquez MF, et al. European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA)/Heart Rhythm Society (HRS)/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS)/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS) Expert Consensus Statement on the state of genetic testing for cardiac diseases. Europace. 2022;24:1307–67. [CrossRef]

- Miller DT, Lee K, Gordon AS, et al. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2021 update: a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2021;23:1391–1398. [CrossRef]

- Abdulla J, Nielsen JR. Is the risk of atrial fibrillation higher in athletes than in the general population? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2009;11:1156–1159. [CrossRef]

- Marcus GM, Vittinghoff E, Whitman IR, et al. Acute consumption of alcohol and discrete atrial fibrillation events. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1503–1509. [CrossRef]

- Kany S, Jurgens SJ, Rämö JT, et al. Genetic testing in early-onset atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(34):3111–3123. [CrossRef]

- Huang K, Trinder M, Roston TM, et al. The Interplay Between Titin, Polygenic Risk, and Modifiable Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37(6):848–856. [CrossRef]

- Arbustini E, Behr ER, Carrier L, et al. Interpretation and actionability of genetic variants in cardiomyopathies: a position statement from the European Society of Cardiology Council on cardiovascular genomics. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:1901–1916. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).