Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Case Reports

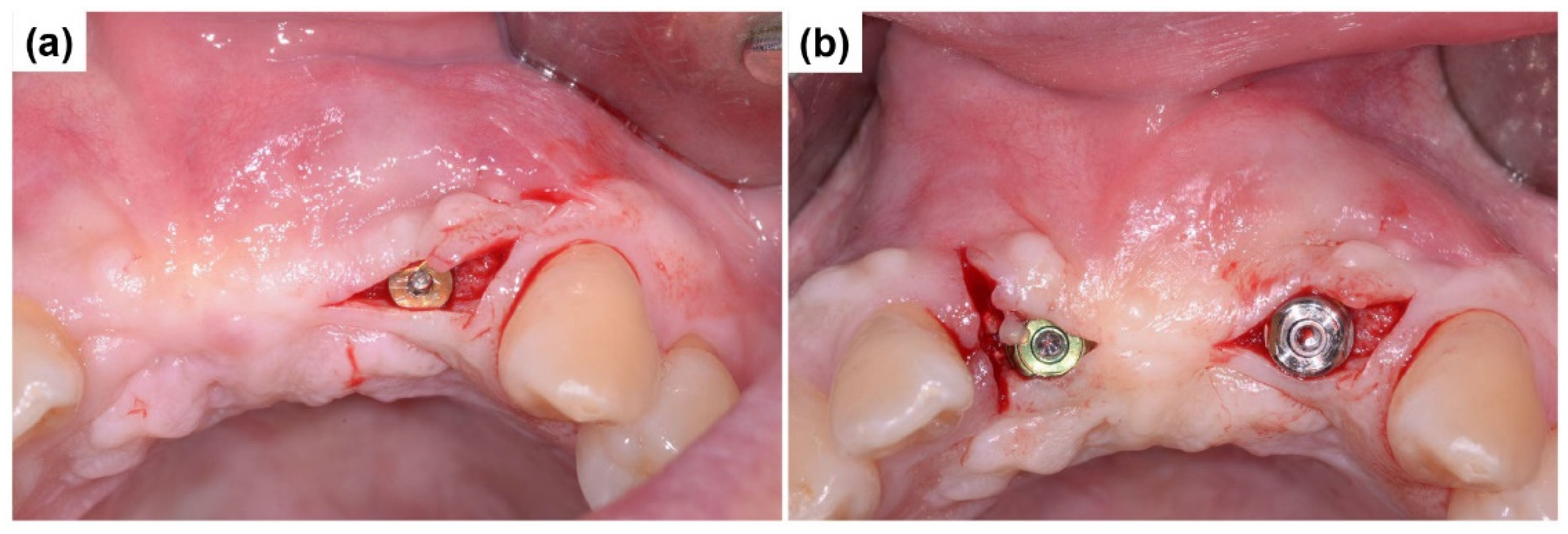

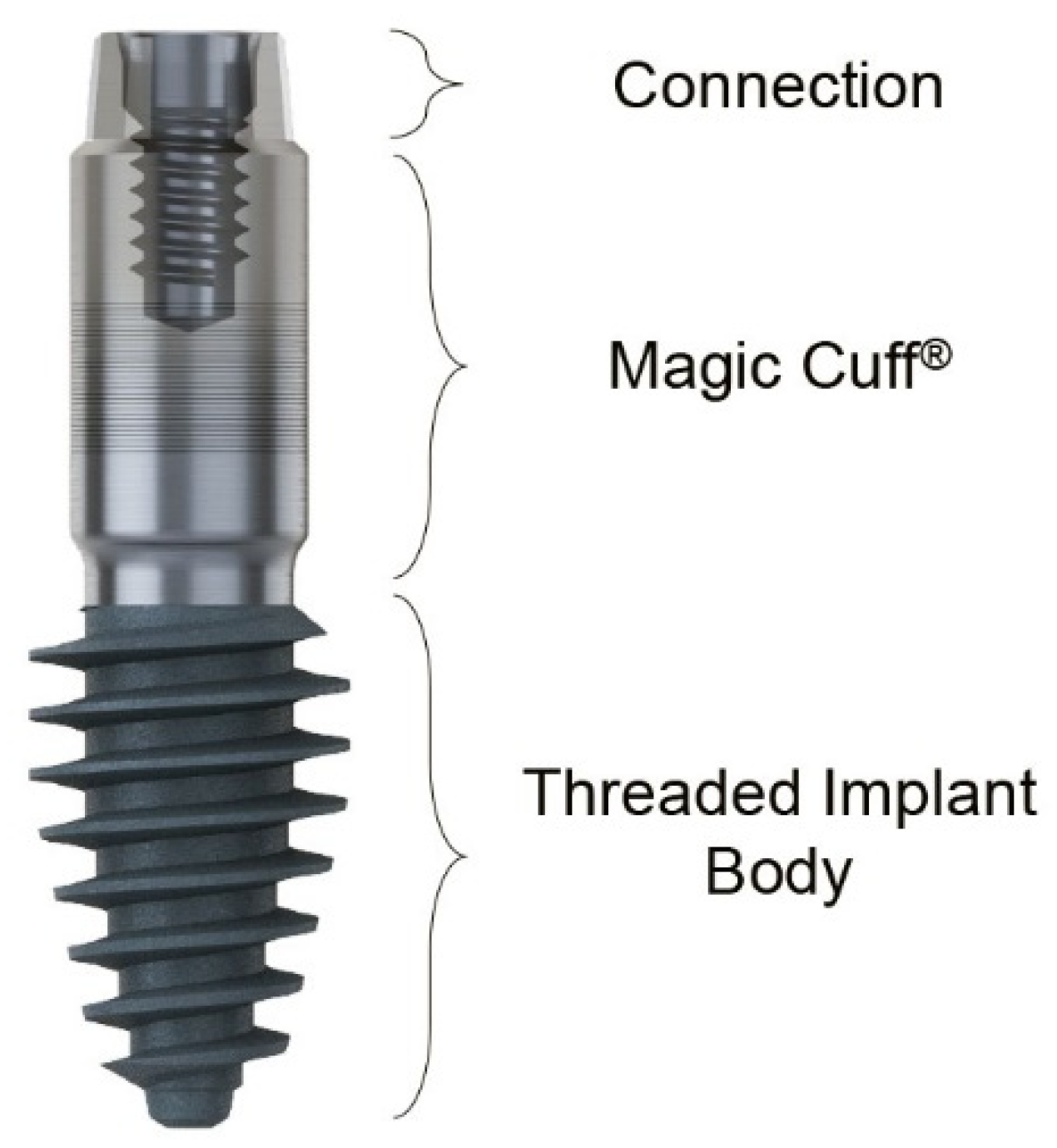

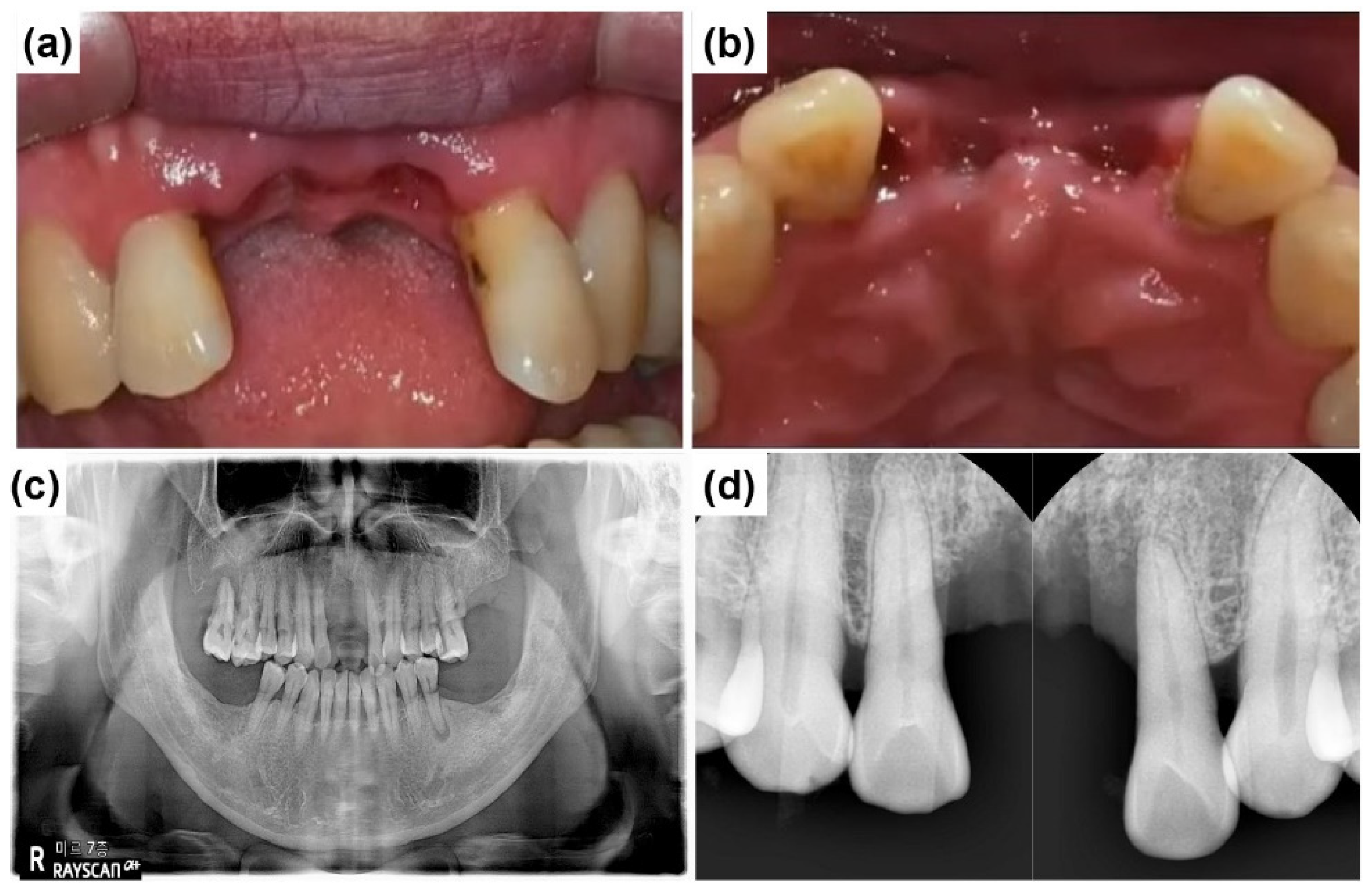

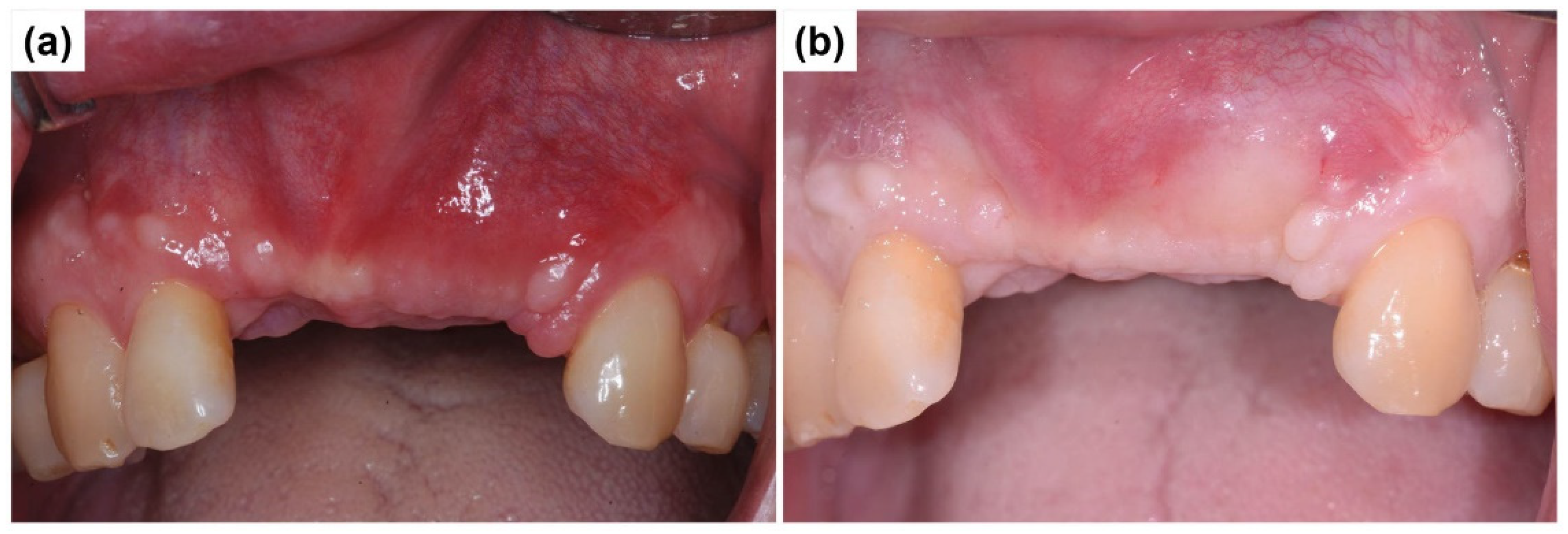

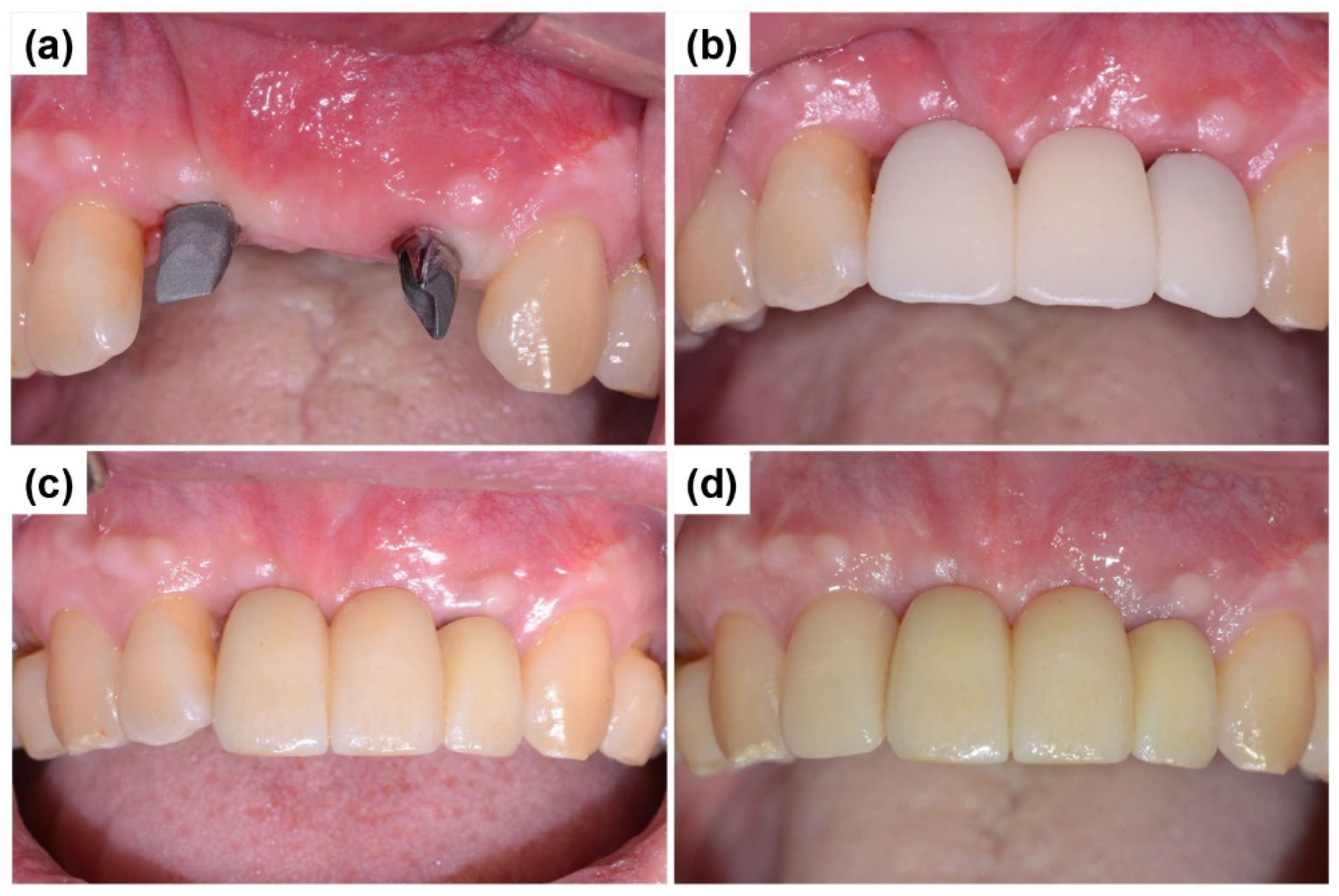

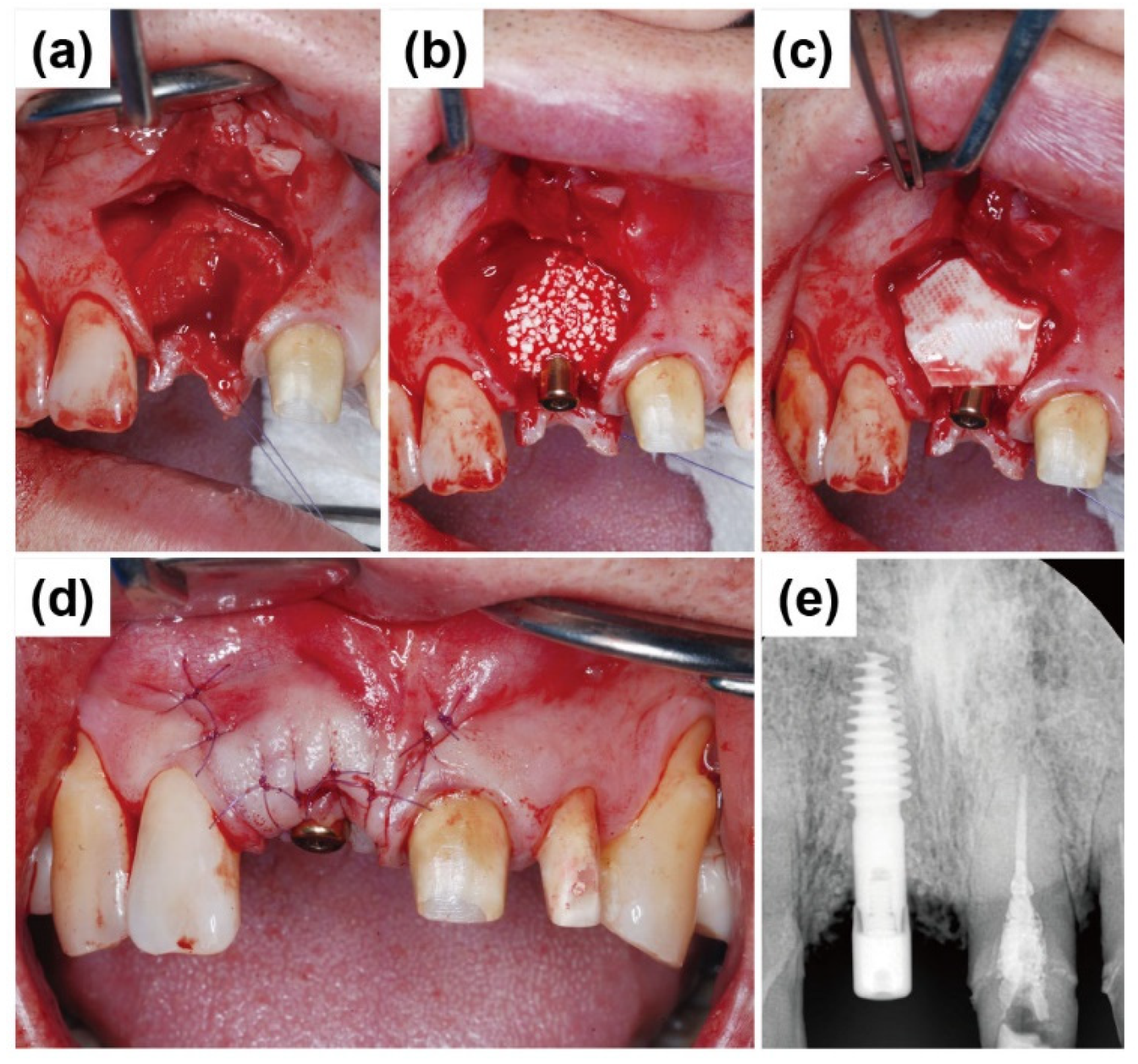

2.1. Case Report 1

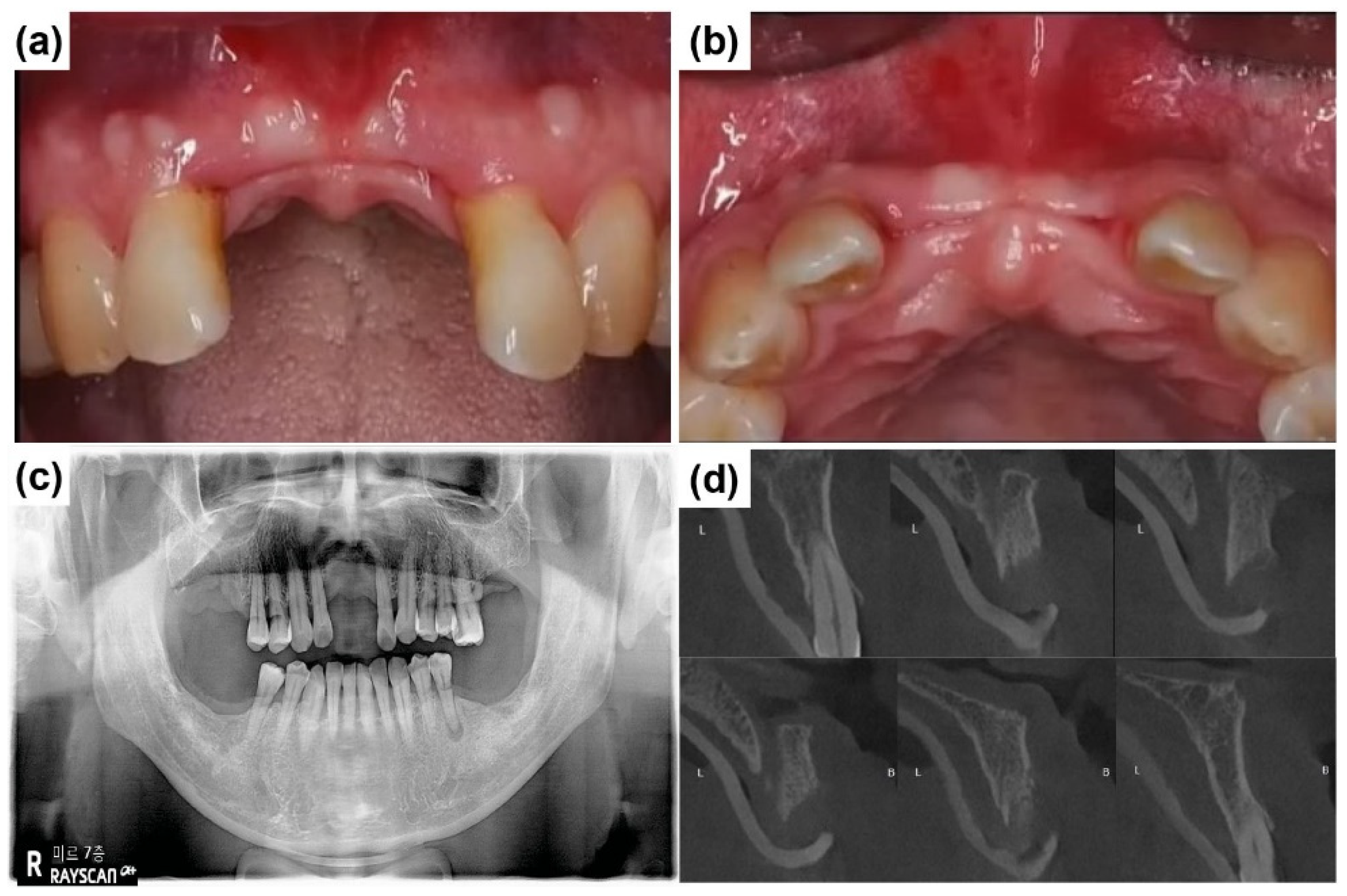

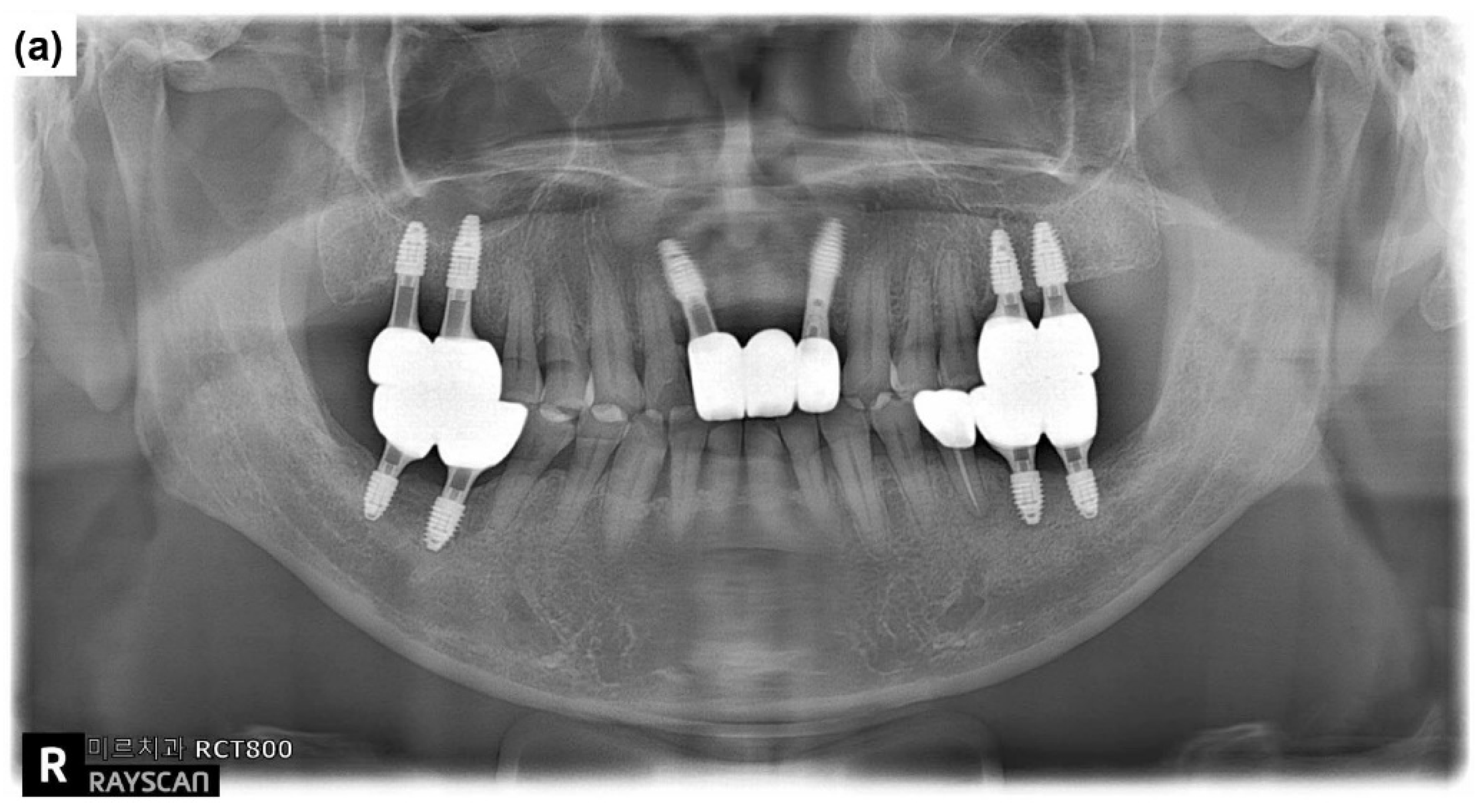

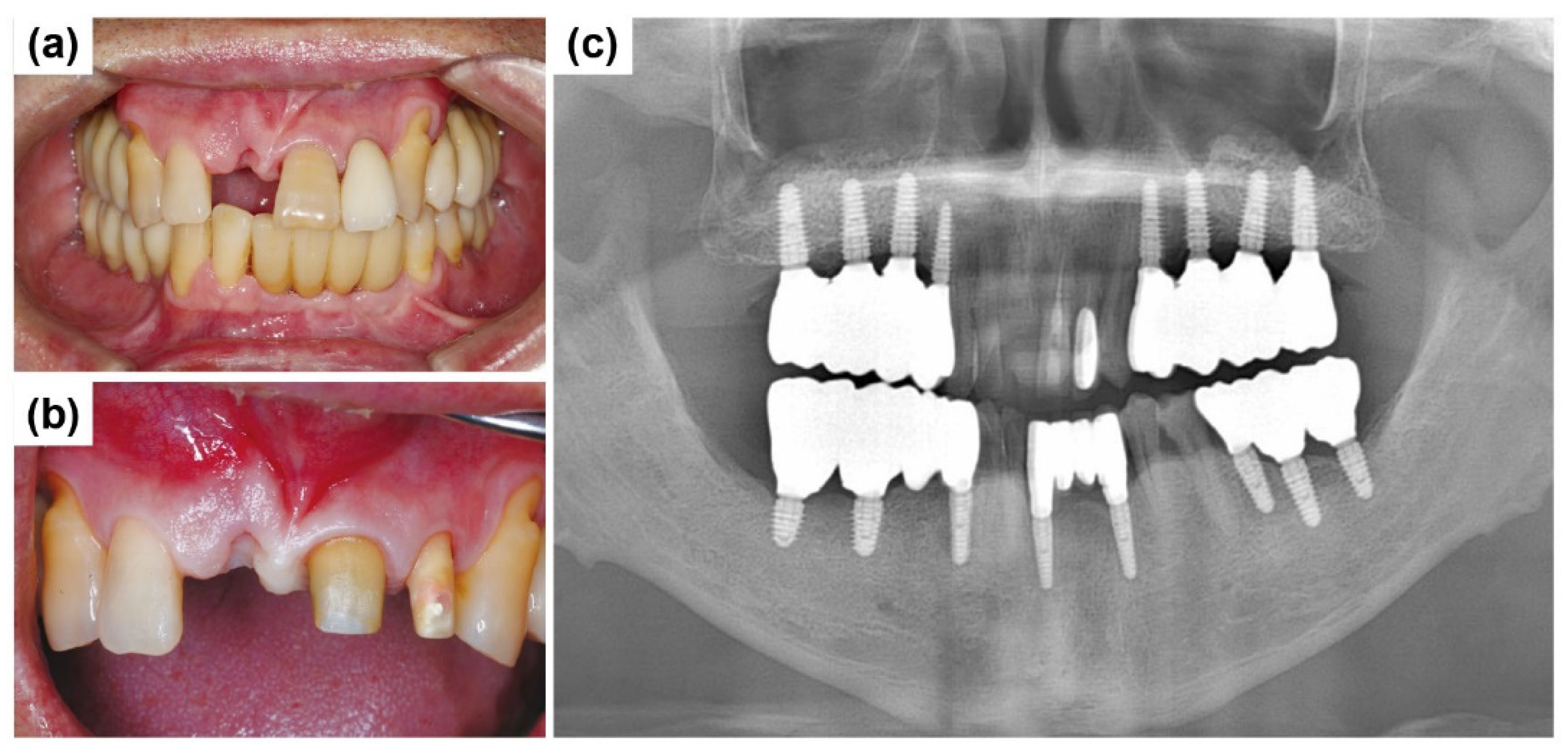

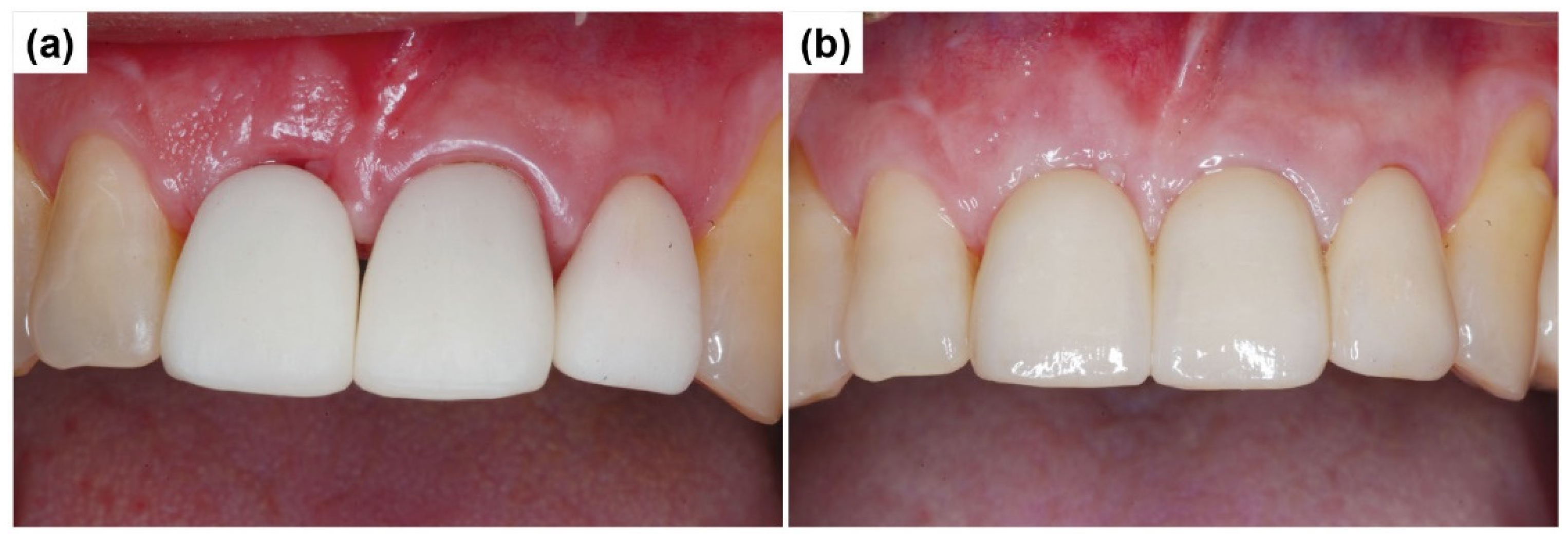

2.2. Case Report 2

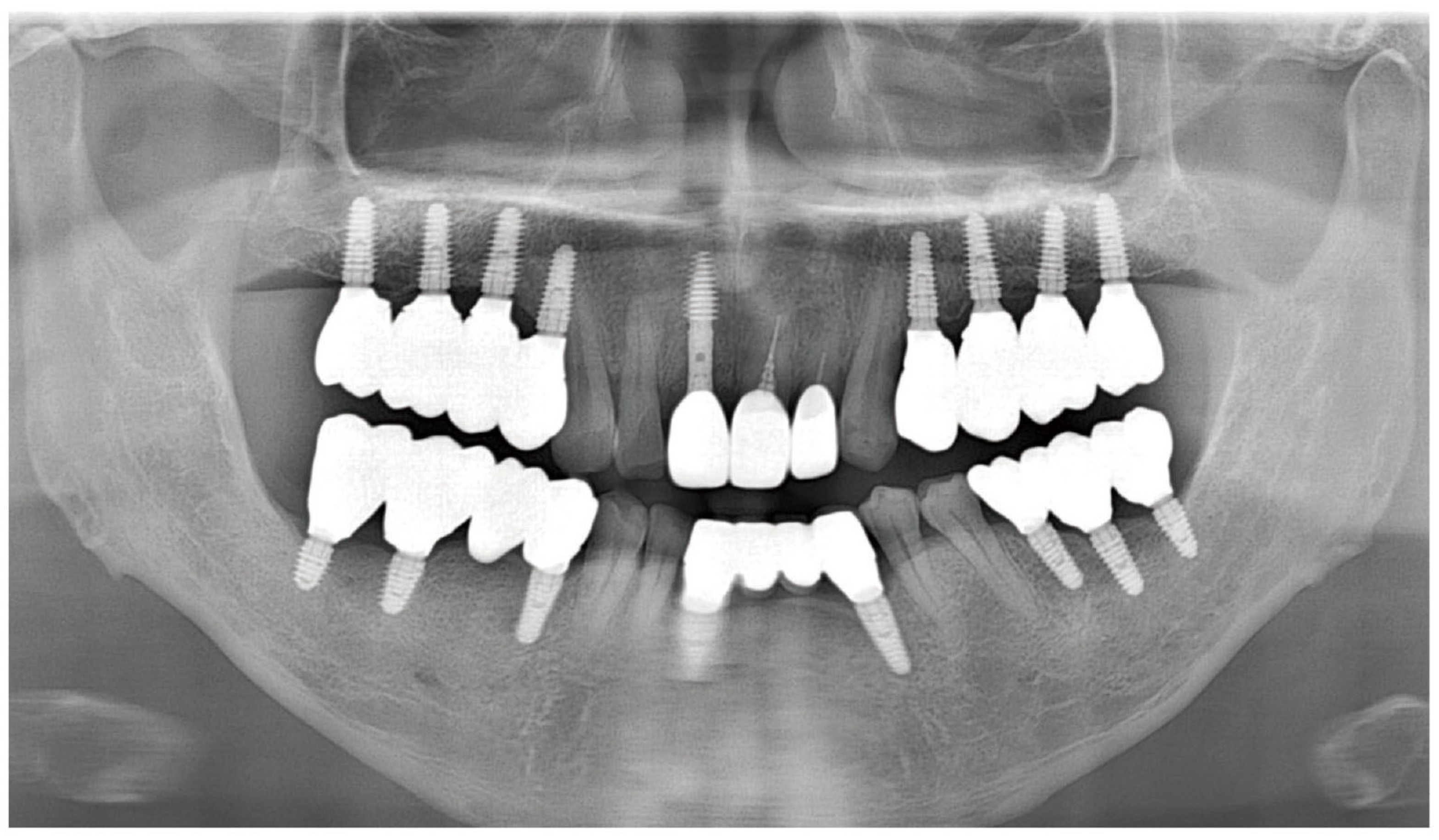

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, P.; Yu, S.; Zhu, G. The psychosocial impacts of implantation on the dental aesthetics of missing anterior teeth patients. Br. Dent. J. 2012, 213(11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pithon, M.M.; Nascimento, C.C.; Barbosa, G.C.G.; Coqueiro, R.S. Do dental esthetics have any influence on finding a job? Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial. Orthop. 2014, 146, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boardman, N.; Darby, I.; Chen, S. A retrospective evaluation of aesthetic outcomes for single-tooth implants in the anterior maxilla. Clin. Oral. Implants. Res. 2016, 27, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.D.; Verma, A.; Dubey, T.; Thakur, S. Basal osseointegrated implants: classification and review. Int. J. Contemp. Med. Res. 2017, 4, 2329–2335. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, K.; Madan, S.; Mehta, D.; Shah, S. P.; Trivedi, V.; Seta, H. Basal implants: An asset for rehabilitation of atrophied resorbed maxillary and mandibular jaw–A prospective study. Ann. Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 11, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chiapasco, M.; Casentini, P.; Zaniboni, M. Bone augmentation procedures in implant dentistry. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac Implants. 2009, 24, 237–259. [Google Scholar]

- Titsinides, S.; Agrogiannis, G.; Karatzas, T. Bone grafting materials in dentoalveolar reconstruction: A comprehensive review. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2019, 55, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rispoli, L.; Fontana, F.; Beretta, M.; Poggio, C. E.; Maiorana, C. Surgery guidelines for barrier membranes in guided bone regeneration (GBR). J. Otolaryngol. Rhinol. 2015, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, R.; Mishra, N.; Alexander, M.; Gupta, S.K. Implant survival between endo-osseous dental implants in immediate loading, delayed loading, and basal immediate loading dental implants a 3-year follow-up. Ann. Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 7, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccuzzo, M.; Savoini, M.; Dalmasso, P.; Ramieri, G. Long-term outcomes of implants placed after vertical alveolar ridge augmentation in partially edentulous patients: A 10-year prospective clinical study. Clin. Oral. Implants. Res. 2017, 28, 1204–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnu, V.A.; Sanyal, P.K.; Tewary, S.; Nilesh, K.; Prasad, R.M.S.; Pawashe, K. A split-mouth clinico-radiographic comparative study for evaluation of crestal bone and peri-implant soft tissues in immediately loaded implants with and without platelet-rich plasma bioactivation. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospects. 2019, 13, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Kumar, S.; Singh, R.; Vaibhav, V.; Kedia, N.B.; Singh, A.K. Basal implants-A new era of prosthodontic dentistry. IP. Ann. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 2020, 6, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.R.; Hong, M.H. Improved biocompatibility and osseointegration of nanostructured calcium-incorporated titanium implant surface treatment (XPEED®). Materials. 2024, 17, 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makary, C.; Menhall, A.; Lahoud, P.; Yang, K.R.; Park, K.B.; Razukevicius, D.; Traini, T. Bone-to-implant contact in implants with plasma-treated nanostructured calcium-incorporated surface (XPEEDActive) compared to non-plasma-treated implants (XPEED): a human histologic study at 4 weeks. Materials. 2024, 17, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makary, C.; Menhall, A.; Lahoud, P.; An, H.W.; Park, K.B.; Traini, T. Nanostructured calcium-incorporated surface compared to machined and SLA dental implants—A split-mouth randomized case/double-control histological human study. Nanomaterials. 2023, 13, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Sánchez, I.; Sanz-Martín, I.; Ortiz-Vigón, A.; Molina, A.; Sanz, M. Complications in bone-grafting procedures: classification and management. Periodontol. 2000. 2022, 88, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buser, D.; Ingimarsson, S.; Dula, K.; Lussi, A.; Hirt, H.P.; Belser, U.C. Long-term stability of osseointegrated implants in augmented bone: a 5-year prospective study in partially edentulous patients. Int. J. Periodontics. Restorative. Dent. 2002, 22, 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Simion, M.; Fontana, F.; Rasperini, G.; Maiorana, C. Vertical ridge augmentation by expanded-polytetrafluoroethylene membrane and a combination of intraoral autogenous bone graft and deproteinized anorganic bovine bone (Bio Oss). Clin. Oral. Implants. Res. 2007, 18, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosai, H.; Anchlia, S.; Patel, K.; Bhatt, U.; Chaudhari, P.; Garg, N. Versatility of basal cortical screw implants with immediate functional loading. Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery. J. Maxillofac. Oral. Surg. 2022, 21, 824–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrektsson, T.; Johansson, C. Osteoinduction, osteoconduction and osseointegration. Eur. Spine. J. 2001, 10 (Suppl 2), S96–S101. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A.K.; Dixit, N.; Punde, P.; Sinha, K.T.; Jalaluddin, M.; Kumar, A. Stress distribution in cortical bone around the basal implant–A finite element analysis. J. Pharm. Bioallied. Sci. 2021, 13 (Suppl 1), S633–S636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.M.; Othman, K.S.; Samad, A.A.; Mahmud, P.K. Comparison between basal and conventional implants as a treatment modality in atrophied ridges. J. Dent. Implant. Res. 2019, 38, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chrcanovic, B.R.; Albrektsson, T.; Wennerberg, A. Bone quality and quantity and dental implant failure: A systematic re-view and meta-analysis. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2017, 30, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beri, A.; Pisulkar, S.G.; Bansod, A.; Shrivastava, A.; Jain, R.; Deshmukh, S. Rapid smile restoration: basal implants for the edentulous mandible with immediate loading. Cureus. 2024, 16, e62655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalaut, P.; Shekhawat, H.; Meena, B. Full-mouth rehabilitation with immediate loading basal implants: A case report. Na-tl. J. Maxillofac. Surg 2019, 10, 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.M.; Mahmud, P.K.; Othman, K.S.; Samad, A.A. Single piece dental implant: A remedy for atrophic ridges. Int. J. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck. Surg. 2019, 8, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, G.V.; Agrawal, N.; Shukla, N.; Aishwarya, K.; Ponnamma, C.C.; Raj, A. An evaluation of the efficacy and acceptabil-ity of basal implants in traumatically deficient ridges of the maxilla and the mandible. Cureus 2023, 15, e43443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, C.; Deora, S.; Abraham, D.; Gaba, R.; Kumar, B.T.; Kudva, P. Vascularized interpositional periosteal connective tissue flap: A modern approach to augment soft tissue. J. Indian. Soc. Periodontol. 2015, 19, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, A.L.; Kotsakis, G.A.; McHale, M.G.; Lareau, D.E.; Hinrichs, J.E.; Romanos, G.E. Soft tissue surgical procedures for optimizing anterior implant esthetics. Int J. Dent. 2015, 2015, 740764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atri, F.; Nokar, K. Prosthetic Soft tissue management in esthetic implant restorations, Part I: Presurgical planning, implant placement, and restoration timing. A narrative review. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2024, 10, e900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccioli, U.; Fonzar, A.; Lanzuolo, S.; Meloni, S.M.; Lumbau, A.I.; Cicciù, M.; Tallarico, M. Tissue recession around a dental implant in anterior maxilla: How to manage soft tissue when things go wrong? Prosthesis. 2021, 3, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).