Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

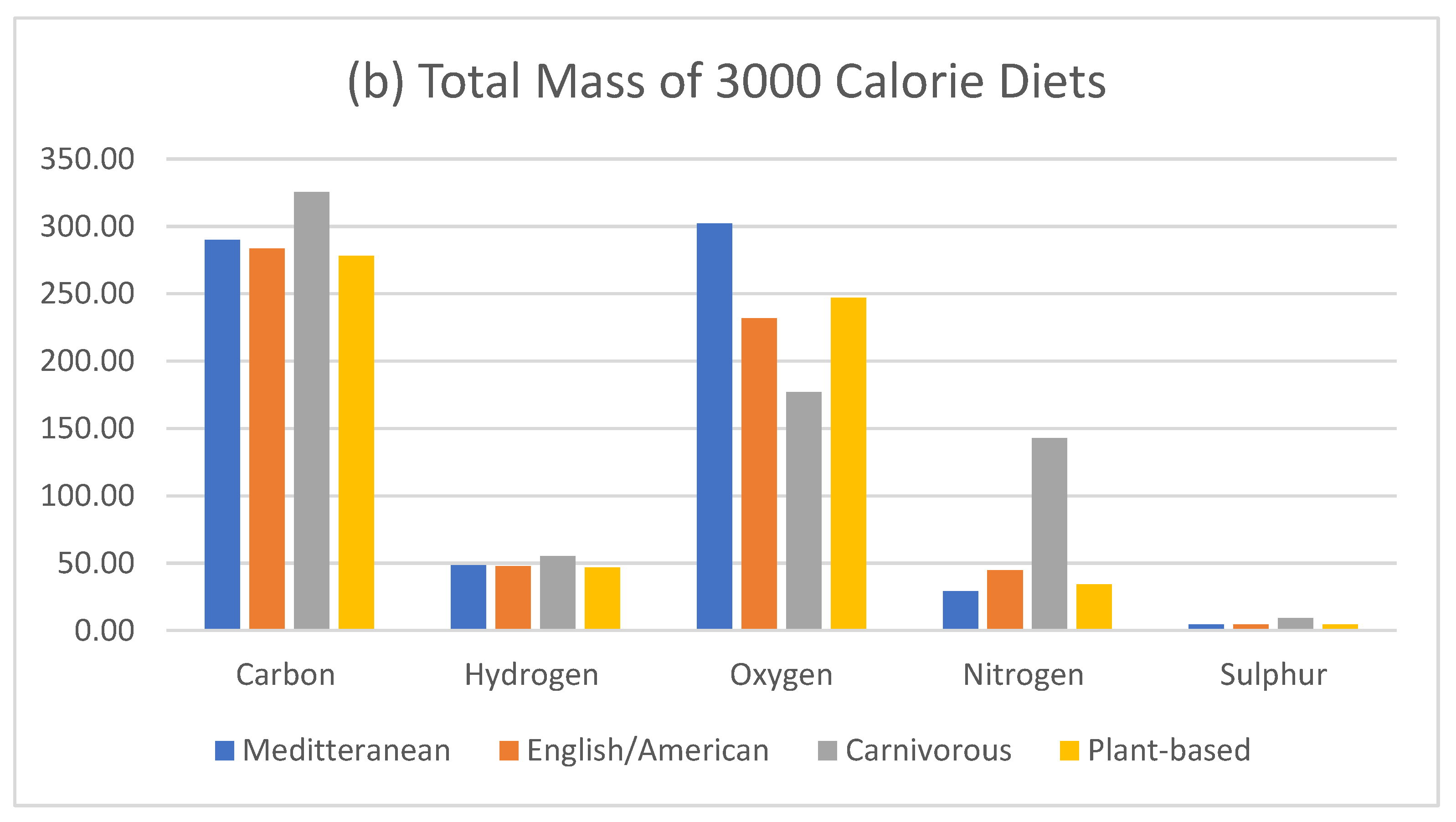

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Carbon

3. Oxygen

3.1. Basal Metabolic Rate

3.2. Metabolic Uniquity and Heat Production

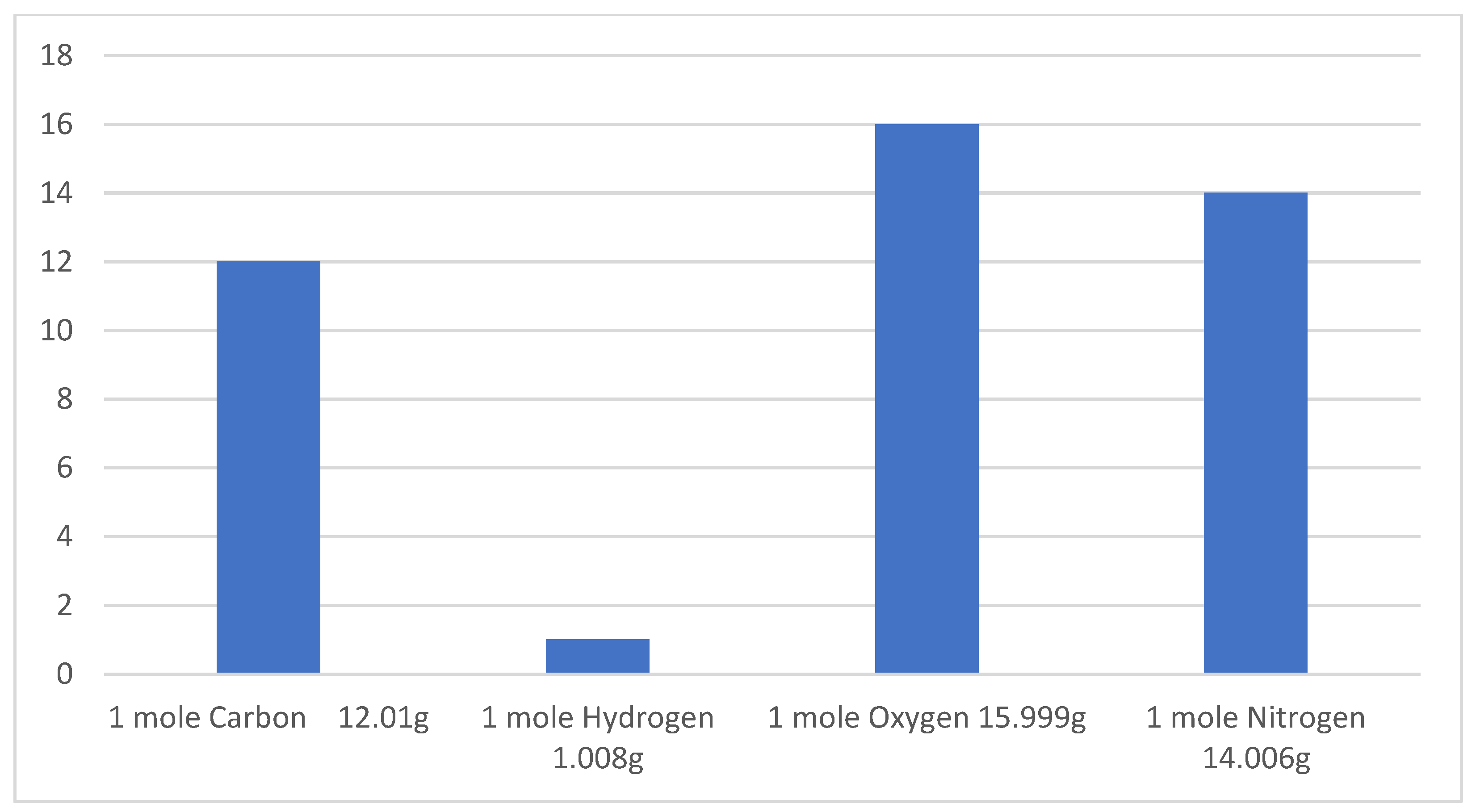

4. Elemental Composition Vs Mass

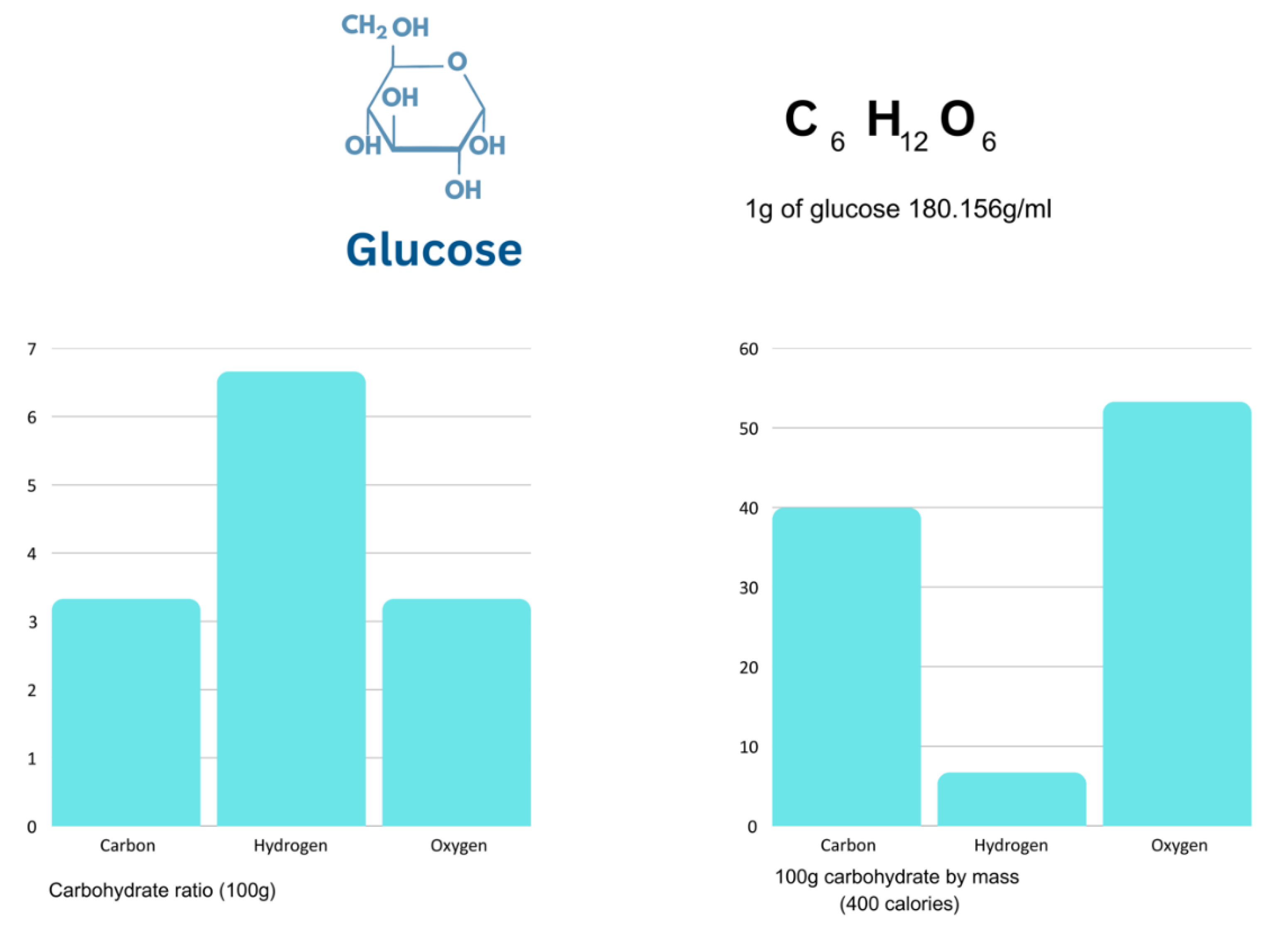

4.1. Carbohydrate

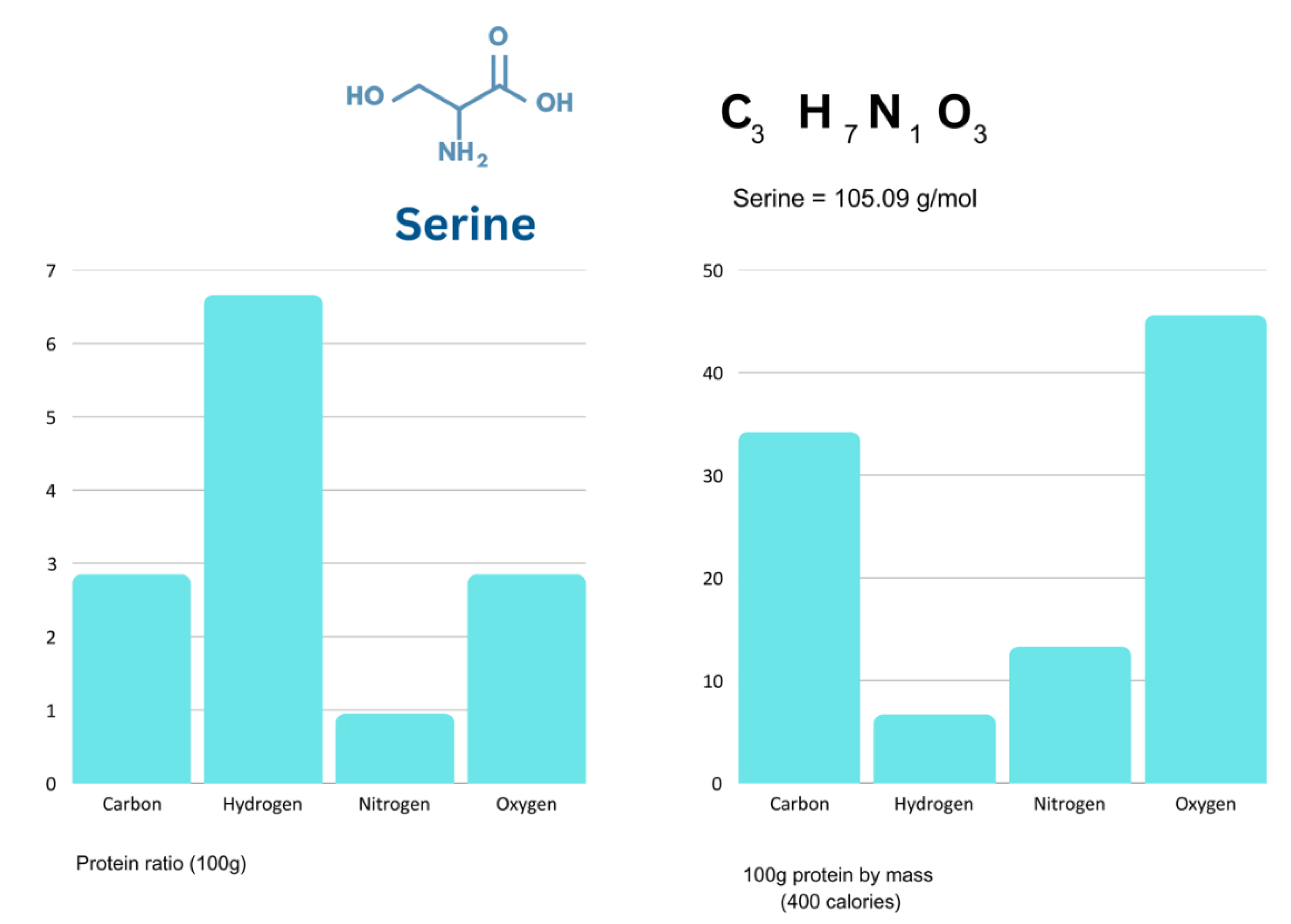

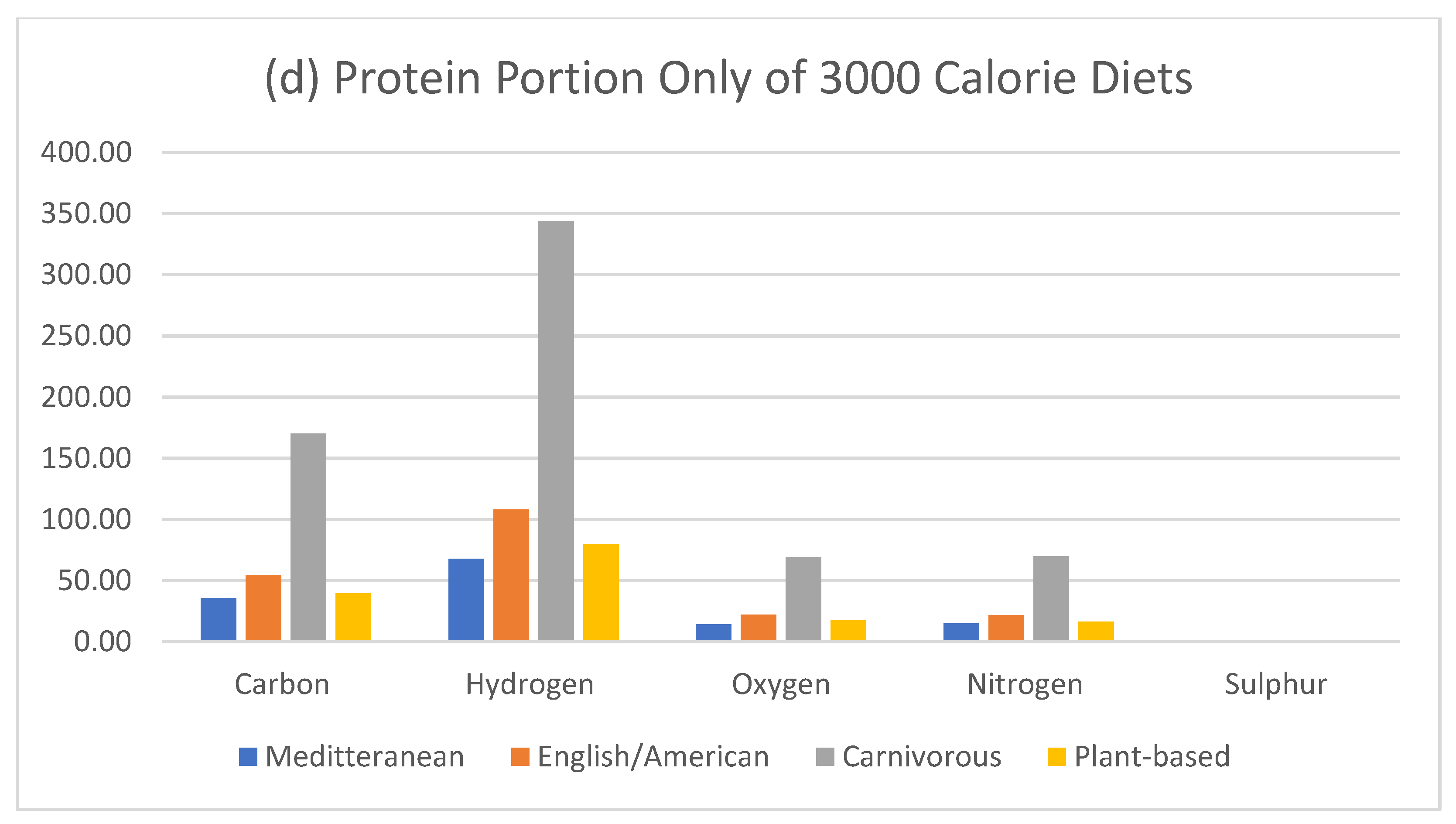

4.2. Protein

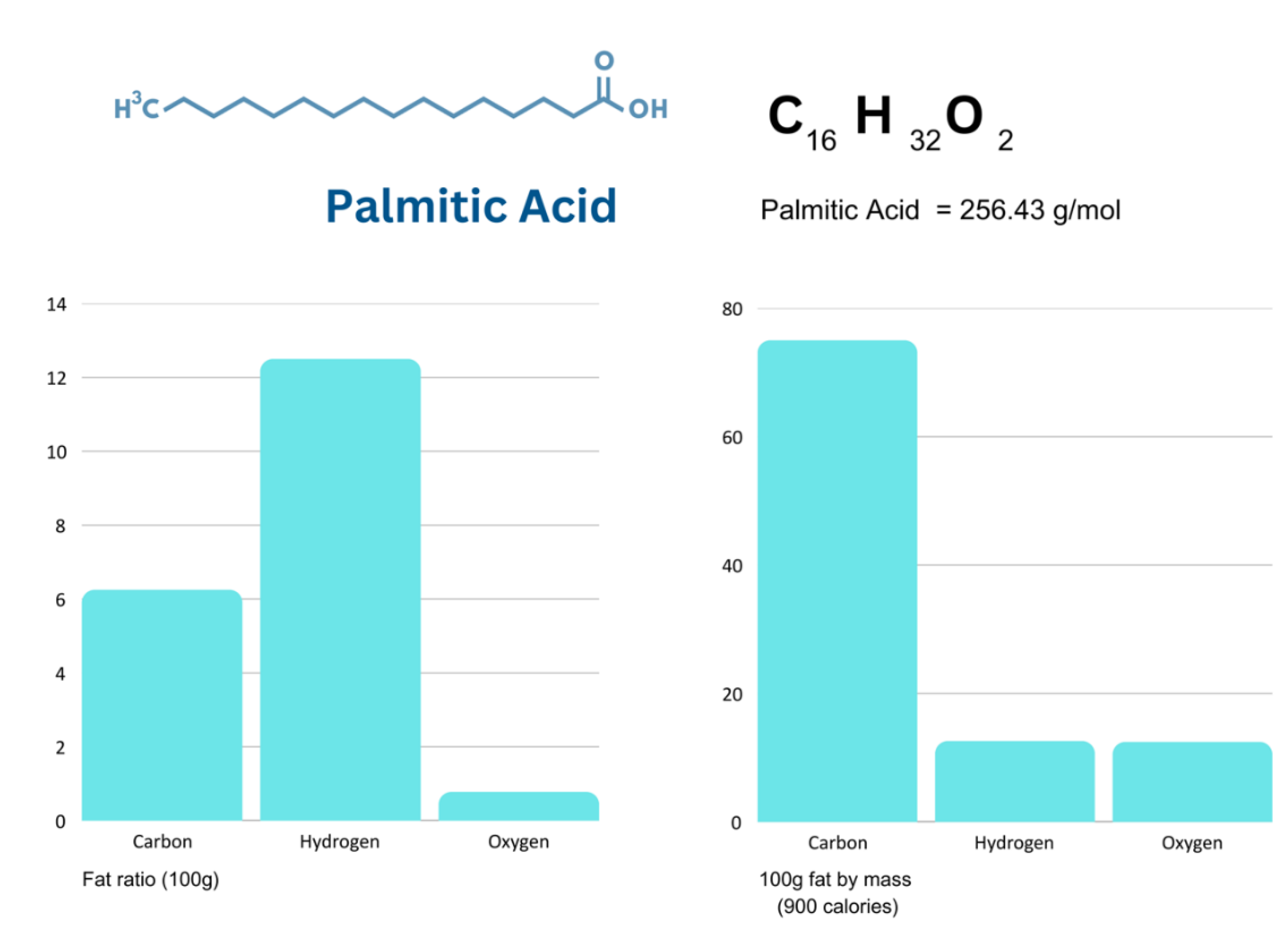

4.3. Fat

5. Elemental Storage and Dietary Substitution

5.1. Nitrogen Storage

5.2. Carbon Storage

5.3. Oxygen and Hydrogen Storage

5.4. Hydrogen

6. Body Mass Index

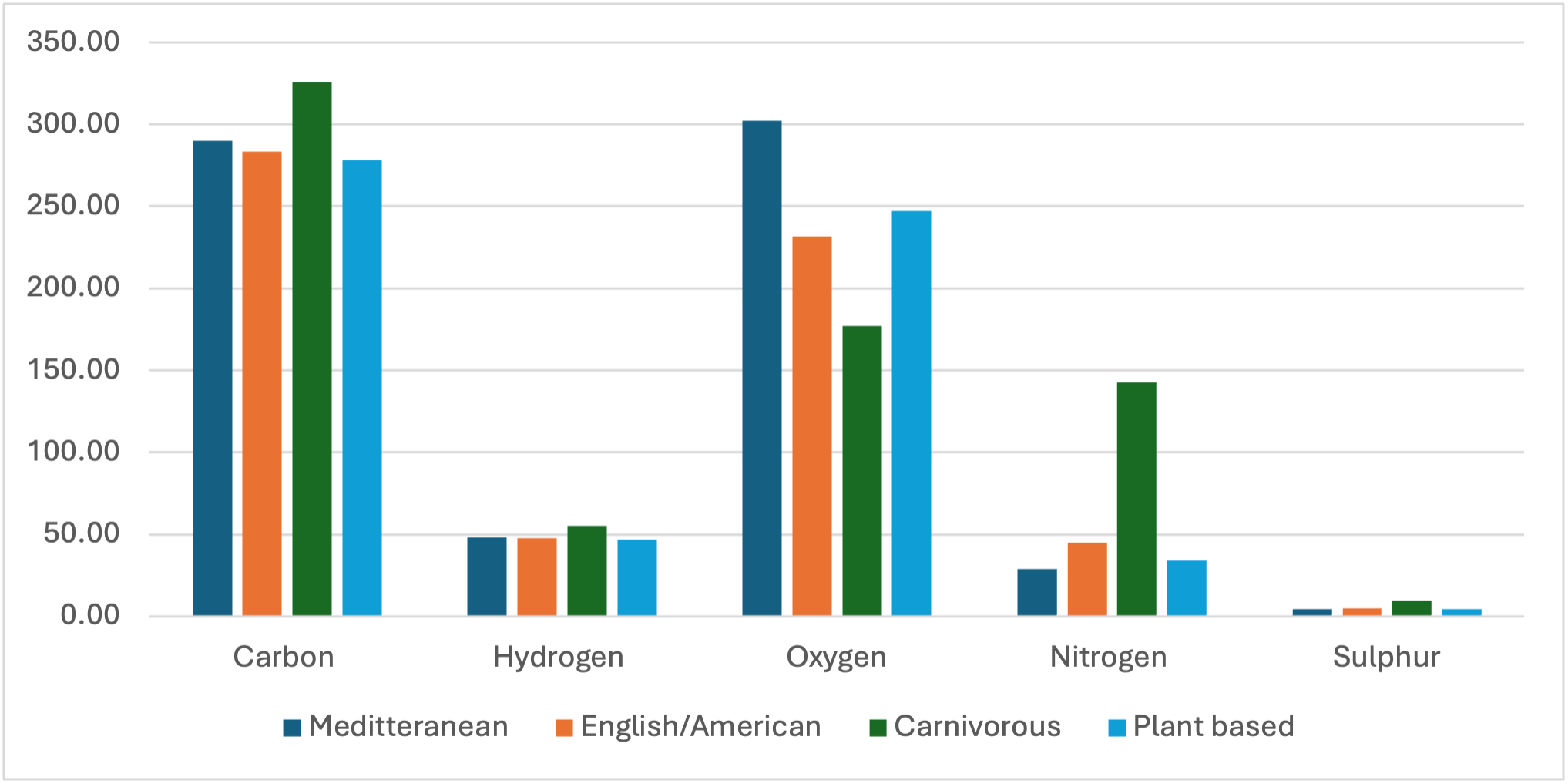

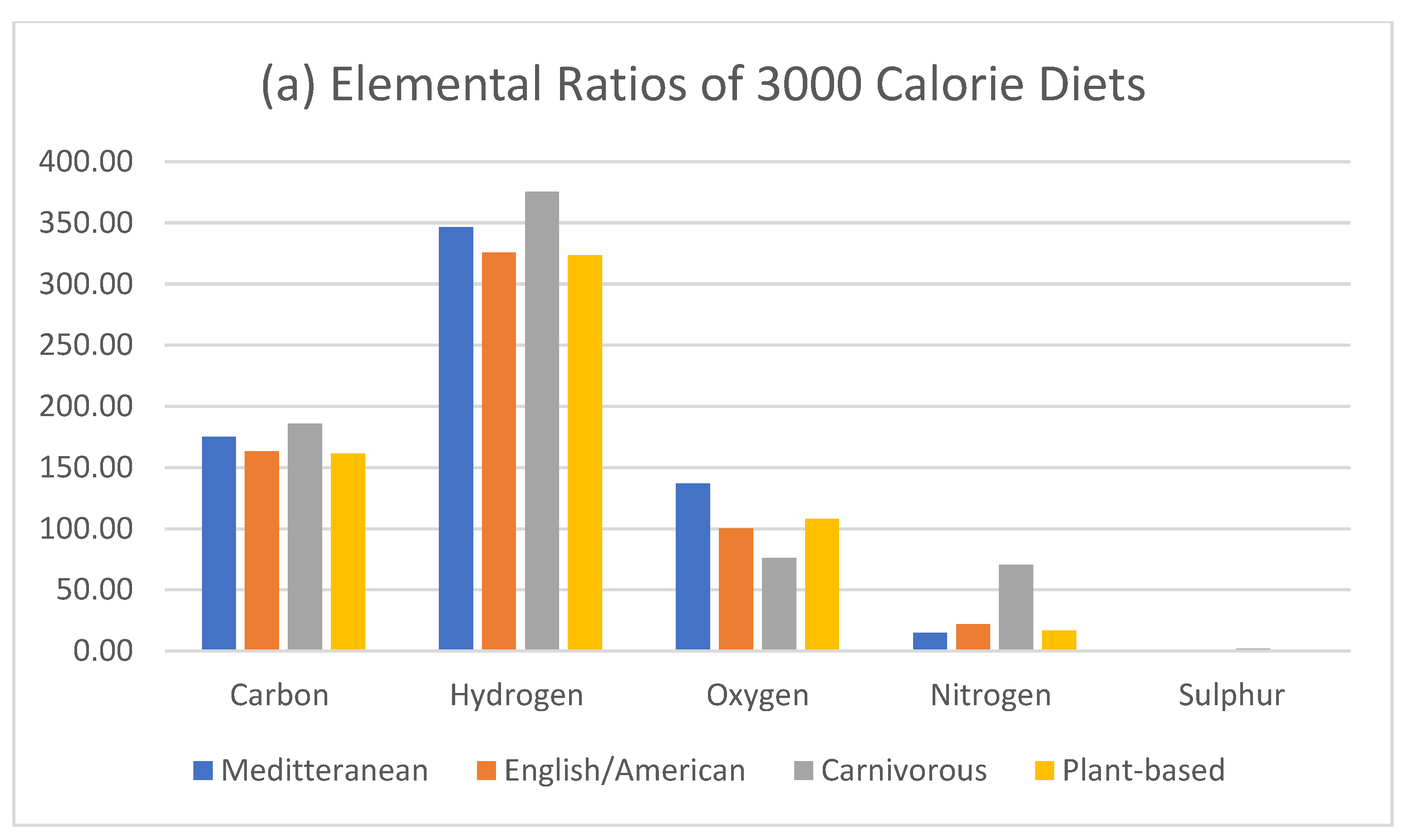

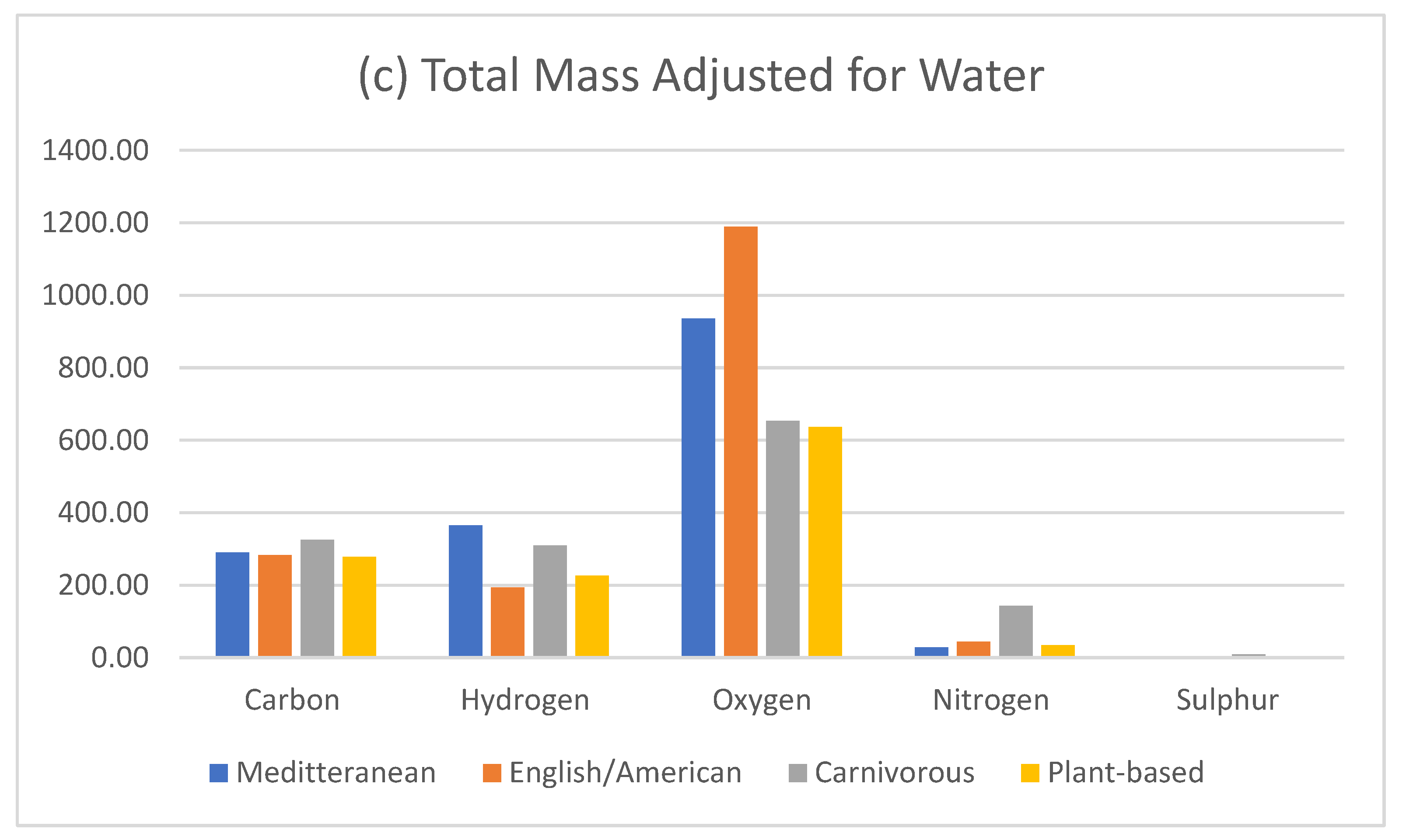

7. Dietary Comparison of Mass

8. Epigenetic Programming

8.1. Epigenetic Programming Energy Metabolism and Human Intervention

9. Deficiency

10. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| CO | Carbon Monoxide |

| CO₂ (CO2) | Carbon Dioxide |

| O₂ (O2) | Oxygen |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| 1-CM | One-Carbon Metabolism |

| MAT | Methionine Adenosyltransferase |

| BMR | Basal Metabolic Rate |

| RQ | Respiratory Quotient |

| RER | Respiratory Exchange Ratio |

| VO₂ (VO2) | Volume of Oxygen Consumption |

| VCO₂ (VCO2) | Volume of Carbon Dioxide Production |

| TBG | Thyroxine Binding Globulin |

| T4 | Thyroxine |

| SERCA1 & 2 | Sarcoplasmic/Endoplasmic Reticulum Calcium ATPase 1 & 2 |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| FSANZ | Food Standards Australia New Zealand |

| CID | Compound Identifier (used by PubChem) |

References

- Mantzioris E, Villani A (2019) Translation of a Mediterranean-style diet into the Australian Dietary Guidelines: a nutritional ecological and environmental perspective. Nutrients, 2507. [CrossRef]

- Dietitian/Nutritionists from the Nutrition Education Materials Online “NEMO” team (Queensland Government) & (2021) Mediterranean-style diet, https://www.health.qld.gov. 23 May.

- The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (2014) Mediterranean diet: reducing cardiovascular disease risk.

- Hess JM (2022) Modeling dairy-free vegetarian and vegan USDA food patterns for non-pregnant nonlactating adults. The Journal of Nutrition, 2097. [CrossRef]

- Morgan J (1979) The life and adventures of William Buckley.

- Hicks, C.S. (1963) ‘Climatic adaptation and drug habituation of the Central Australian Aborigine’, Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 42, pp. 39–57.

- 1915.

- Simmons A (1796) American cookery or the art of dressing viands fish poultry and vegetables.

- Irwin D (1830) The housewife’s guide or an economical and domestic art of cookery.

- Glasse H (1747) The art of cookery made plain and easy.

- Editors at Nutrition Australia (2013) Nutrition Australia.

- /: at Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) Australian Food Composition Database, https, 23 May.

- Sedley, L. (2023) Epigenetics. In: Dinan, T.G. (ed.) Nutritional Psychiatry: A Primer for Clinicians. Cambridge University Press, pp. 172–211.

- Fan, J. , Kamphorst, J.J. et al. (2014) ‘Glutamine-driven oxidative phosphorylation is a major ATP source in transformed mammalian cells in both normoxia and hypoxia’, Molecular Systems Biology, 9(1), p. 712.

- Alberti, K.G. (1977) ‘The biochemical consequences of hypoxia’, Journal of Clinical Pathology, s3-11(1), pp. 14–20.

- Pé Rez-Mato, I. , Castro, C. et al. (1999) ‘Methionine adenosyltransferase S-nitrosylation is regulated by the basic and acidic amino acids surrounding the target thiol’, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 274(24).

- Thomas, D.D. (2015) ‘Breathing new life into nitric oxide signaling; A brief overview of the interplay between oxygen and nitric oxide.’, Redox Biology, 5, pp. 225–233.

- Schwart L, Guais, A et al (2010) Carbon dioxide is largely responsible for the acute inflammatory effects of tobacco smoke. /: Inhal Toxicol 22(7): 543–551 https. [CrossRef]

- Kent, L.R. (1961) ‘Carbon dioxide therapy as a medical treatment for stuttering’, Journal of Speech Hearing Disorders, 26, pp. 268–271.

- LaVerne, A.A. (1973) ‘Carbon dioxide therapy (CDT) of addictions’, Behavioral Neuropsychiatry, 11–12(1–6), p. 13.

- E: L (2025) A Critical Analysis of Dietetics – Part 1, 2025.

- Kellogg, J.H. (1927) The New Dietetics; A guide to scientific feeding in Health and Disease, The Modern Medical Publishing Company.

- Wilson, B.C. (2014) Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and the Religion of Biologic Living. Indiana University Press.

- Kellogg, J.H. (1899) ‘Are we to be a toothless race?’, Dental Register, 53(3), pp. 135–144.

- Harris, J.A. , Benedict, F.G. (1919) A biometric study of basal metabolism in man. Alpha Editions.

- Roza, A.M. , Shizgal, H.M. (1984) ‘The Harris Benedict equation reevaluated; resting energy requirements and the body cell mass.’, American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 40.

- Patel, H.K. (2023) ‘Physiology respiratory quotient’, StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing.

- Liebig, M. (1842) ‘The source of animal heat’, Provincial Medical and Surgical Journal, 4(103), pp. 488–489.

- Scholander, P.F. , Hammel, H.T. et al. (1958) ‘Cold adaptation in Australian Aborigines’, The Journal of Physiology, 12, pp. 212–216.

- Flowers, P. , Theopold, K. et al. (2019) Gas laws for ideal gases. Chemistry 2e, /: at: https.

- White, G.H. , Morice, R. (1980) ‘Diagnostic biochemical tests in Aboriginals’, Medical Journal of Australia, 1(SP1), pp. 6–8.

- Takeda, K. , Mori, Y. et al. (1989) ‘Sequence of the variant thyroxine-binding globulin of Australian Aborigines.’, Journal of Clinical Investigation, 83(4), pp. 1344–1348.

- Qi, X. , Chan, W.L. et al. (2014) ‘Temperature-responsive release of thyroxine and its environmental adaptation in Australians.’, Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 281(1779).

- Simonides, W.S. , Thelen, M.H.M. (2001) ‘Mechanism of thyroid-hormone regulated expression of the SERCA Genes in skeletal muscle: implications for thermogenesis.’, American Journal of Physiology, cited in text.

- Ulivieri, A. , Lavra, L. et al. (2022) ‘Thyroid hormones regulate cardiac repolarization and QT-interval related gene expression in hiPSC cardiomyocytes.’, Scientific Reports, 12(1).

- Rasmussen, M.; et al. (2011) ‘An Aboriginal Australian genome reveals separate human dispersals into Asia.’, Science, 334, pp. 94–98.

- Hancock, G. (2022) Ancient Apocalypse. Netflix.

- Alley, R.B. (2004) ‘The Roger Revelle Commemorative Lecture Series—Abrupt climate changes: Oceans, ice, and us, Oceanography, 17(4), pp. 194–206.

- a: Kanazawa (2007) Big and tall soldiers are more likely to survive battle, 2007; 22. [CrossRef]

- Bouttes, N.; et al. (2011) ‘Last Glacial Maximum CO₂ and δ¹³C successfully reconciled.’, Geophysical Research Letters, 38(L02705).

- Judd, E.J.; et al. (2024) ‘A 485-million-year history of Earth's temperature’, Science, 385(6650), pp. 1316–1320.

- Gerhart, L.M. , Ward, J.K. (2010) ‘Plant responses to low [CO₂] of the past. ’, New Phytologist, 188(3), pp. 674–695.

- Akiel, R. (2025) ’Molar Mass of Dietary Elements’, In Chem 201: General Chemistry I OER. College of the Canyons. LibreTexts. https://chem.libretexts.

- Pant, R. , Firmal, P. et al. (2021) ‘Epigenetic regulation of adipogenesis in development of metabolic syndrome.’, Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 8.

- Jéquier, E. (1994) ‘Carbohydrates as a source of energy’, American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 59(3), pp. 682S–685S.

- Fernández-Elías, V.E. , Ortega, J.F. et al. (2015) ‘Relationship between muscle water and glycogen recovery after prolonged exercise in the heat in humans’, European Journal of Applied Physiology, 115, pp. 1919–1926.

- Ceperuelo-Mallafré, V. , Ejarque, M. et al. (2016) ‘Adipose tissue glycogen accumulation is associated with obesity-linked inflammation in humans’, Molecular Metabolism, 5(1), pp. 5–18.

- Tafeit, E.; et al. (2019) ‘Using body mass index ignores the intensive training of elite special force personnel.’, Experimental Biology and Medicine, 244(11), pp. 873–879.

- Moon, J. , Koh, G. (2020) ‘Clinical Evidence and Mechanisms of High-Protein Diet-Induced Weight Loss, Journal of Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome, 29, pp. 166–173.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (2025) PubChem Compound Summary for CID 985, Palmitic Acid. Available at: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.

- Listrat, A. , Lebret, B. et al. (2016) ‘How muscle structure and composition influence meat and flesh quality’, Scientific World Journal. [CrossRef]

- Meznaric, M. , Cvetko, E. (2016) ‘Size and proportions of slow-twitch and fast-twitch muscle fibers in human costal diaphragm, BioMed Research International, 2016, Article ID 5946520.

- Sanitarium Health Food Company (2023) Weet-Bix Original. Available at: https://www.sanitarium.

- McDonald's Australia (2023) Main food menu – Allergen, ingredients and nutrition info. Available at: https://mcdonalds.com.

- Hungry Jack's (2025) Chicken. Available at: https://www.hungryjacks.com.

- Aldi (2025) Chicken Schnitzel. Available at: https://www.aldi.com.

- Burke LM, Whitfield J, Heikura IA, Ross MLR, Tee N, Forbes SF, Hall R, McKay AKA, Wallett AM, Sharma AP (2020) ‘Adaptation to a low carbohydrate high fat diet is rapid but impairs endurance exercise metabolism and performance despite enhanced glycogen availability’. The Journal of Physiology.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).