Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

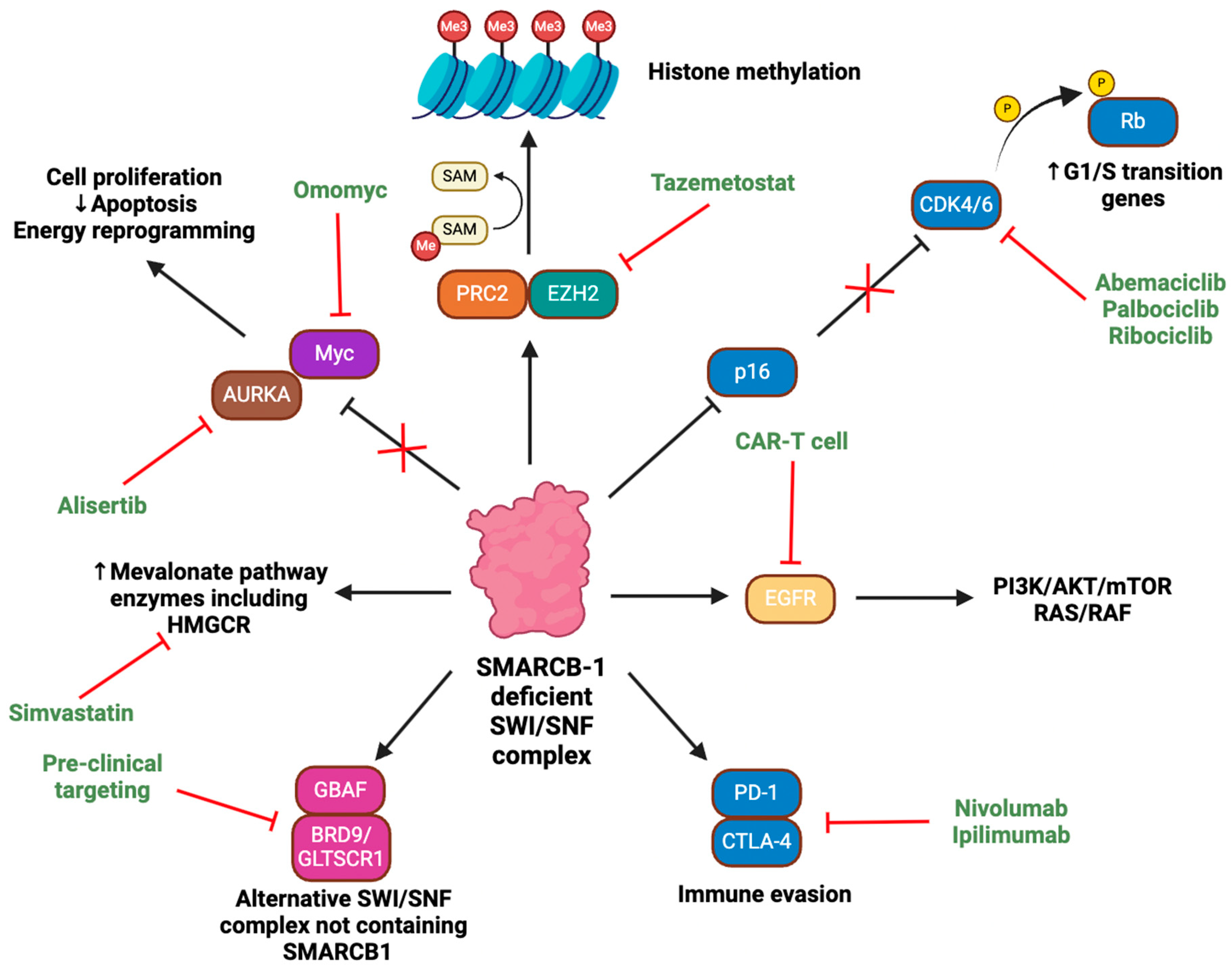

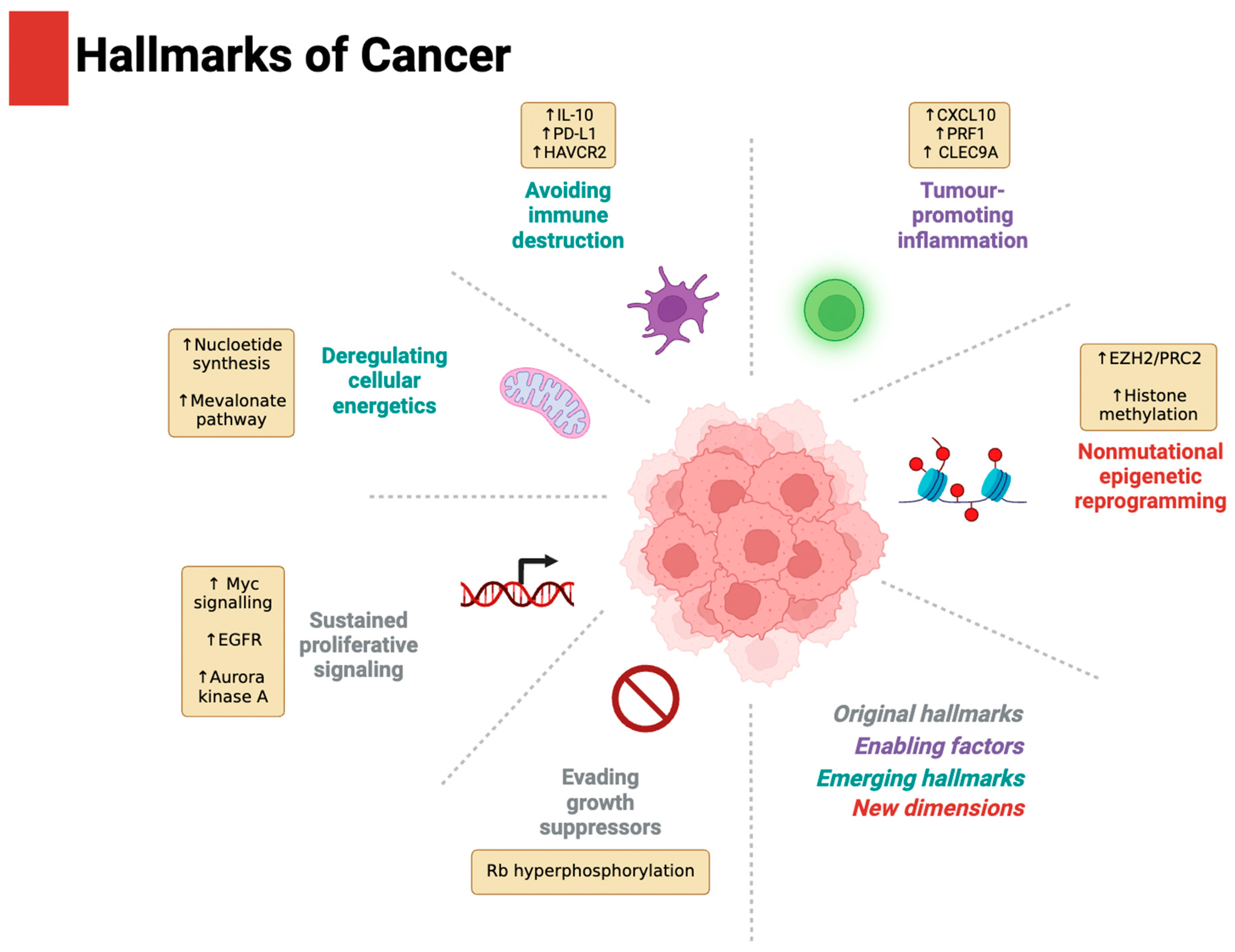

Driver of the Hallmarks of Cancer

Evading Growth Suppressors and Sustaining Proliferative Signalling

Tumour-Promoting Inflammation and Avoiding Immune Destruction

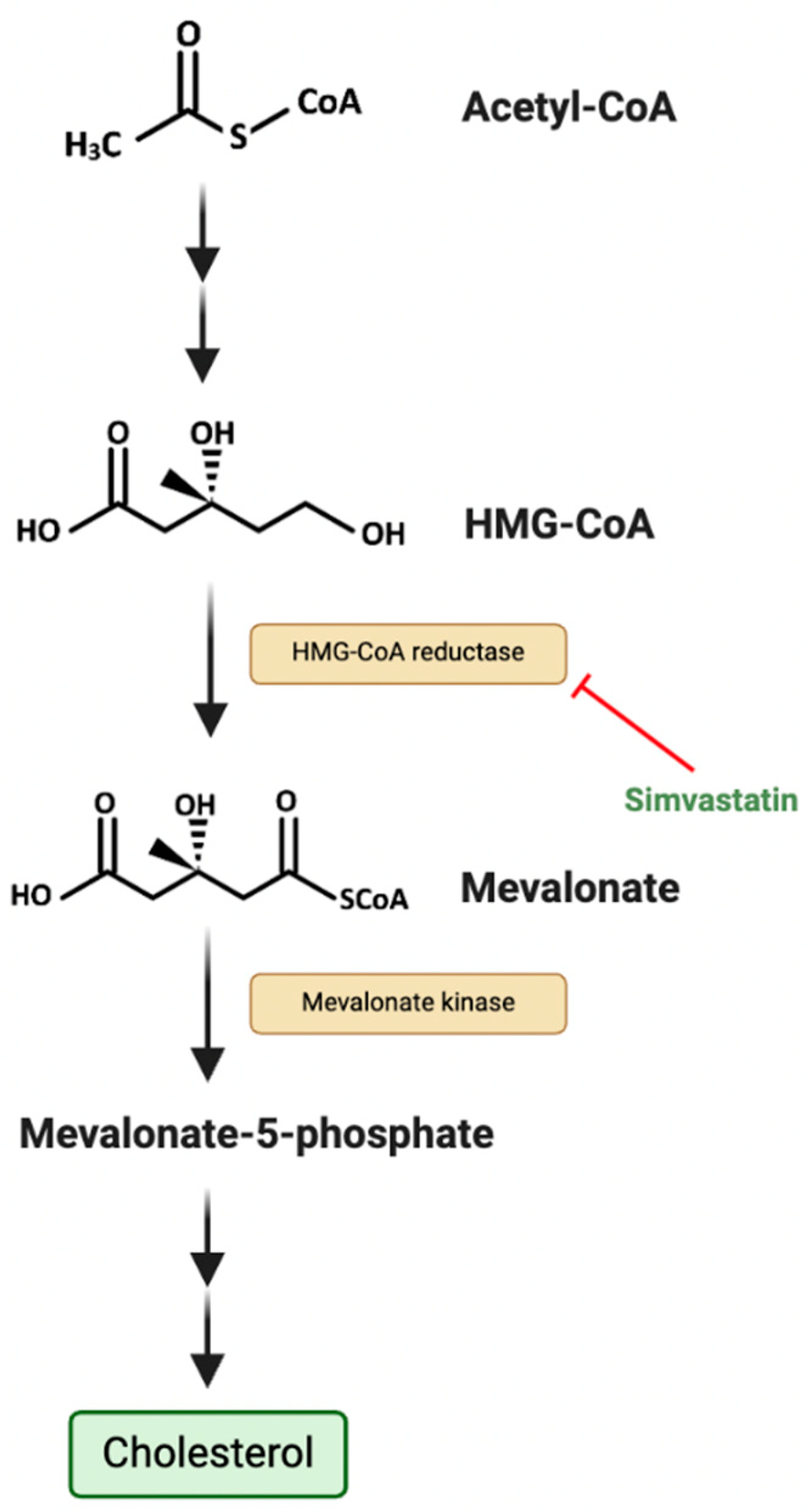

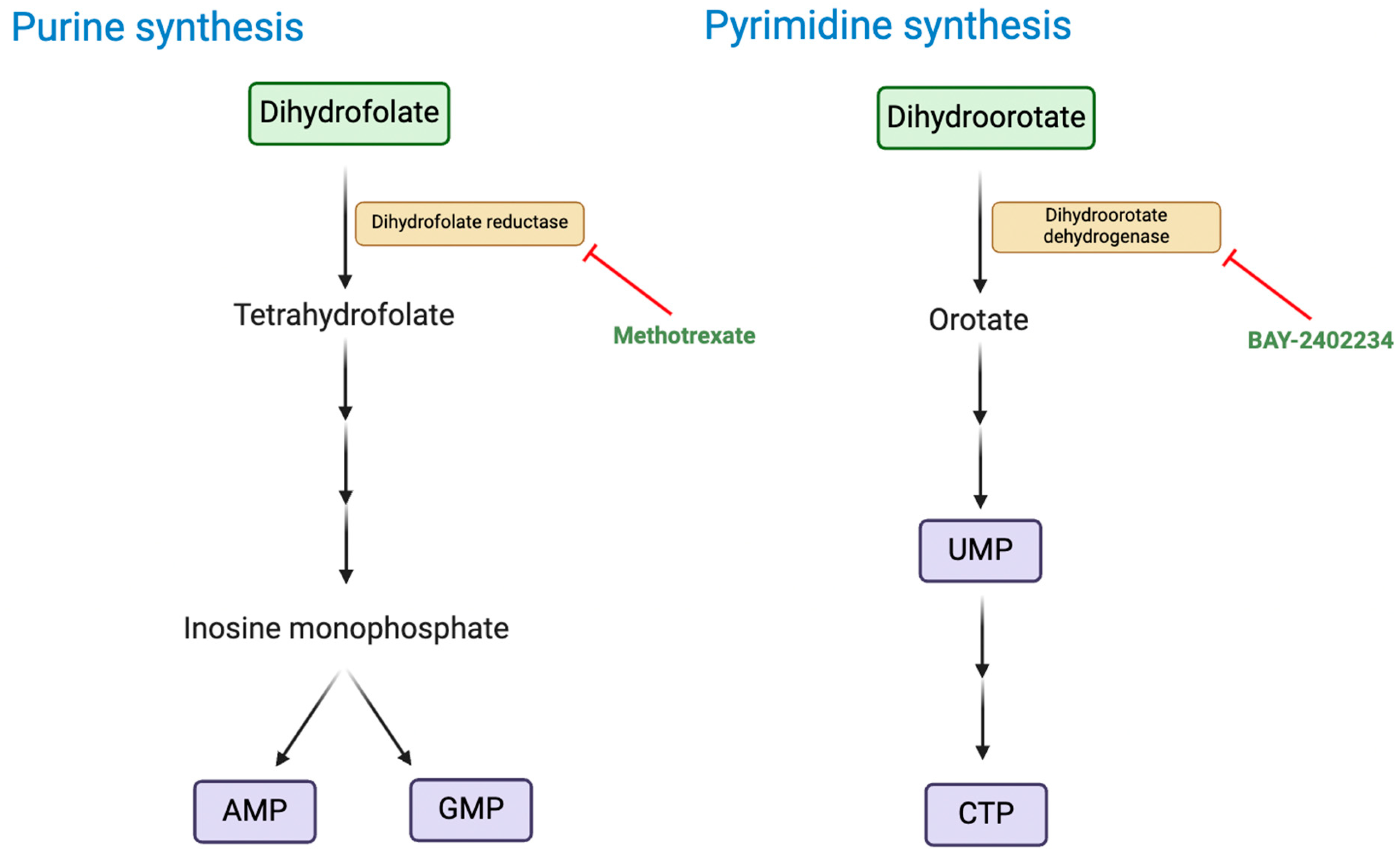

Deregulating Cellular Energetics

Non-Mutational Epigenetic Reprogramming

Ongoing Trials and Future Direction

Immunotherapies

| Trial number | Phase | SMARCB-1 targeting therapies | Disorder | Target | Status | Sites | Primary outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT06622941 [60] | II | Nivolumab (ONO-4538) | RT | PD-1 | Not yet recruiting | Osaka and Tokyo, Japan. | Objective response rate |

| NCT05407441 [57] | I/II | Tazemetostat, nivolumab, ipilimumab. | SMARCB1 negative or SMARCA4- deficient tumours including RT | EZH2, PD-1, CTLA-4 | Recruiting | Boston, USA. | Toxicity and dosing parameters |

| NCT05286801 [55] | I/II | Tiragolumab and Atezolizumab | SMARCB1 or SMARCA4 deficient tumours including RT | TIGIT, PD-L1 | Recruiting | USA, Canada, and Australia. | Objective response rate and dose-limiting toxicities |

| NCT04416568 [53] | II | Nivolumab and Ipilimumab | SMARCB1-negative tumours | PD-1, CTLA-4 | Recruiting | Texas, USA. | Objective overall response rate |

| Trial number | Phase | SMARCB-1 targeting therapies | Disorder | Target | Status | Sites | Primary outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT06193759 [61] | I | Cytotoxic T lymphocytes directed against proteogenomically determined tumour-specific antigens | Paediatric brain tumours, including RT. | Various tumour-specific antigens | Recruiting | Washington, USA. | Various adverse event and toxicity parameters |

| NCT05835687 [62] | I | Locoregional autologous B7-H3-CAR T cells | Primary CNS neoplasms including RT | B7-H3-positive tumours | Recruiting | Tennessee, USA. | Maximum tolerated dose |

| NCT05103631 [25] | I | GPC3-CART cells and IL-15 | Solid tumours including RT | GPC3-positive tumours | Recruiting | Texas, USA. | Dose-limiting toxicities |

| NCT04897321 [63] | I | Autologous B7-H3-CAR T cells | Solid tumours including RT | B7-H3-positive tumours | Recruiting | Tennessee, USA. | Maximum tolerated dose |

| NCT04715191 [26] | I | GPC3-CART cells and IL-15/21 | Paediatric solid tumours including RT | GPC3-positive tumours | Recruiting | Texas, USA. | Dose-limiting toxicities |

| NCT04377932 [27] | I | GPC3-CART cells and IL-15 | Paediatric solid tumours including RT | GPC3-positive tumours | Recruiting | Texas, USA. | Dose-limiting toxicities |

| NCT04185038 [64] | I | Locoregional autologous B7-H3-CAR T cells | Paediatric CNS tumours including RTs | B7-H3-positive tumours | Recruiting | Washington, USA. | Feasibility and adverse event parameters |

| NCT03618381 [65] | I | EGFR806 CAR T Cell Immunotherapy | Recurrent/refractory solid tumours in children and young adults including RT | EGFR | Recruiting | Washington, USA. | Maximum tolerated dose, feasibility, and adverse event parameters. |

| NCT04483778 [66] | I | B7-H3-CAR T cells | Recurrent/refractory solid tumours in children and young adults including RT | B7-H3-positive tumours | Active, not recruiting | Washington, USA. | Various safety, tolerability, toxicity, and feasibility parameters |

Targeting Epigenetic Aberrations

Targeting Auxiliary Oncogenic Aberrations

Next Frontiers in Rhabdoid Tumour Research and Treatment

Author Contributions

Conflicts of interest

References

- Pawel, B. R., SMARCB1-deficient Tumors of Childhood: A Practical Guide. Pediatric and Developmental Pathology 2017, 21 (1), 6-28. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G. W.; Hong, A. L., SMARCB1-Deficient Cancers: Novel Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Vulnerabilities. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14 (15). [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N. K.; Godbole, N.; Sanmugananthan, P.; Gunda, S.; Kasula, V.; Baggett, M.; Gajjar, A.; Kouam, R. W.; D'Amico, R.; Rodgers, S., Management of Atypical Teratoid/Rhabdoid Tumors in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg 2024, 181, e504-e515. [CrossRef]

- Nemes, K.; Bens, S.; Bourdeaut, F.; Johann, P.; Kordes, U.; Siebert, R.; Frühwald, M. C., Rhabdoid Tumor Predisposition Syndrome. In GeneReviews(®), Adam, M. P.; Feldman, J.; Mirzaa, G. M.; Pagon, R. A.; Wallace, S. E.; Amemiya, A., Eds. University of Washington, Seattle. Copyright © 1993-2025, University of Washington, Seattle. GeneReviews is a registered trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle. All rights reserved.: Seattle (WA), 1993.

- Sultan, I.; Qaddoumi, I.; Rodríguez-Galindo, C.; Nassan, A. A.; Ghandour, K.; Al-Hussaini, M., Age, stage, and radiotherapy, but not primary tumor site, affects the outcome of patients with malignant rhabdoid tumors. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 2010, 54 (1), 35-40. [CrossRef]

- Lee, R. S.; Stewart, C.; Carter, S. L.; Ambrogio, L.; Cibulskis, K.; Sougnez, C.; Lawrence, M. S.; Auclair, D.; Mora, J.; Golub, T. R.; Biegel, J. A.; Getz, G.; Roberts, C. W. M., A remarkably simple genome underlies highly malignant pediatric rhabdoid cancers. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2012, 122 (8), 2983-2988. [CrossRef]

- Nemes, K.; Fruhwald, M. C., Emerging therapeutic targets for the treatment of malignant rhabdoid tumors. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2018, 22 (4), 365-379. [CrossRef]

- Kalimuthu, S. N.; Chetty, R., Gene of the month: SMARCB1. J Clin Pathol 2016, 69 (6), 484-9. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C. W.; Leroux, M. M.; Fleming, M. D.; Orkin, S. H., Highly penetrant, rapid tumorigenesis through conditional inversion of the tumor suppressor gene Snf5. Cancer Cell 2002, 2 (5), 415-25. [CrossRef]

- Han, Z. Y.; Richer, W.; Freneaux, P.; Chauvin, C.; Lucchesi, C.; Guillemot, D.; Grison, C.; Lequin, D.; Pierron, G.; Masliah-Planchon, J.; Nicolas, A.; Ranchere-Vince, D.; Varlet, P.; Puget, S.; Janoueix-Lerosey, I.; Ayrault, O.; Surdez, D.; Delattre, O.; Bourdeaut, F., The occurrence of intracranial rhabdoid tumours in mice depends on temporal control of Smarcb1 inactivation. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 10421. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, R.; Zin, F.; Thomas, C.; Bens, S.; Gayden, T.; Karamchandani, J.; Dudley, R. W.; Nemes, K.; Johann, P. D.; Oyen, F.; Kordes, U.; Jabado, N.; Siebert, R.; Paulus, W.; Kool, M.; Frühwald, M. C.; Albrecht, S.; Kalpana, G. V.; Hasselblatt, M., Inhibition of nuclear export restores nuclear localization and residual tumor suppressor function of truncated SMARCB1/INI1 protein in a molecular subset of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors. Acta Neuropathol 2021, 142 (2), 361-374. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G. W.; Hong, A. L., SMARCB1-Deficient Cancers: Novel Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Vulnerabilities. Cancers 2022, 14 (15), 3645.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R. A., Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011, 144 (5), 646-74. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D., Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discovery 2022, 12 (1), 31-46. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R. A., The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 2000, 100 (1), 57-70. [CrossRef]

- Betz, B. L.; Strobeck, M. W.; Reisman, D. N.; Knudsen, E. S.; Weissman, B. E., Re-expression of hSNF5/INI1/BAF47 in pediatric tumor cells leads to G1 arrest associated with induction of p16ink4a and activation of RB. Oncogene 2002, 21 (34), 5193-203. [CrossRef]

- Weissmiller, A. M.; Wang, J.; Lorey, S. L.; Howard, G. C.; Martinez, E.; Liu, Q.; Tansey, W. P., Inhibition of MYC by the SMARCB1 tumor suppressor. Nat Commun 2019, 10 (1), 2014. [CrossRef]

- García-Gutiérrez, L.; Delgado, M. D.; León, J., MYC Oncogene Contributions to Release of Cell Cycle Brakes. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10 (3). [CrossRef]

- Amati, B.; Land, H., Myc—Max—Mad: a transcription factor network controlling cell cycle progression, differentiation and death. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 1994, 4 (1), 102-108. [CrossRef]

- Baudino, T. A.; McKay, C.; Pendeville-Samain, H.; Nilsson, J. A.; Maclean, K. H.; White, E. L.; Davis, A. C.; Ihle, J. N.; Cleveland, J. L., c-Myc is essential for vasculogenesis and angiogenesis during development and tumor progression. Genes Dev 2002, 16 (19), 2530-43. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Tu, R.; Liu, H.; Qing, G., Regulation of cancer cell metabolism: oncogenic MYC in the driver’s seat. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2020, 5 (1), 124. [CrossRef]

- Darr, J.; Klochendler, A.; Isaac, S.; Geiger, T.; Eden, A., Phosphoproteomic analysis reveals Smarcb1 dependent EGFR signaling in Malignant Rhabdoid tumor cells. Mol Cancer 2015, 14, 167. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Cimica, V.; Ramachandra, N.; Zagzag, D.; Kalpana, G. V., Aurora A is a repressed effector target of the chromatin remodeling protein INI1/hSNF5 required for rhabdoid tumor cell survival. Cancer Res 2011, 71 (9), 3225-35. [CrossRef]

- Kohashi, K.; Nakatsura, T.; Kinoshita, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Yamada, Y.; Tajiri, T.; Taguchi, T.; Iwamoto, Y.; Oda, Y., Glypican 3 expression in tumors with loss of SMARCB1/INI1 protein expression. Hum Pathol 2013, 44 (4), 526-33. [CrossRef]

- Interleukin-15 Armored Glypican-3-specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor Expressing Autologous T Cells As Immunotherapy for Patients with SOLID TUMORS (CATCH). Center for, C.; Gene Therapy, B. C. o. M.; The Methodist Hospital Research, I., Eds. 2021.

- Interleukin-15 and -21 Armored Glypican-3-specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor Expressing Autologous T Cells as an Immunotherapy for Children With Solid Tumors (CARE). Center for, C.; Gene Therapy, B. C. o. M., Eds. 2021.

- Interleukin-15 Armored Glypican-3-specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor Expressing Autologous T Cells as Immunotherapy for Children With Solid Tumors. Center for, C.; Gene Therapy, B. C. o. M., Eds. 2020.

- Gregory, G. L.; Copple, I. M., Modulating the expression of tumor suppressor genes using activating oligonucleotide technologies as a therapeutic approach in cancer. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2023, 31, 211-223. [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Luo, J.; Wu, Y.; Shen, G.; Kuang, X., The biological essence of synthetic lethality: Bringing new opportunities for cancer therapy. MedComm – Oncology 2024, 3 (1), e70. [CrossRef]

- Radko-Juettner, S.; Yue, H.; Myers, J. A.; Carter, R. D.; Robertson, A. N.; Mittal, P.; Zhu, Z.; Hansen, B. S.; Donovan, K. A.; Hunkeler, M.; Rosikiewicz, W.; Wu, Z.; McReynolds, M. G.; Roy Burman, S. S.; Schmoker, A. M.; Mageed, N.; Brown, S. A.; Mobley, R. J.; Partridge, J. F.; Stewart, E. A.; Pruett-Miller, S. M.; Nabet, B.; Peng, J.; Gray, N. S.; Fischer, E. S.; Roberts, C. W. M., Targeting DCAF5 suppresses SMARCB1-mutant cancer by stabilizing SWI/SNF. Nature 2024, 628 (8007), 442-449. [CrossRef]

- Dedes, K. J.; Wilkerson, P. M.; Wetterskog, D.; Weigelt, B.; Ashworth, A.; Reis-Filho, J. S., Synthetic lethality of PARP inhibition in cancers lacking BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Cell Cycle 2011, 10 (8), 1192-9. [CrossRef]

- Chun, H. E.; Johann, P. D.; Milne, K.; Zapatka, M.; Buellesbach, A.; Ishaque, N.; Iskar, M.; Erkek, S.; Wei, L.; Tessier-Cloutier, B.; Lever, J.; Titmuss, E.; Topham, J. T.; Bowlby, R.; Chuah, E.; Mungall, K. L.; Ma, Y.; Mungall, A. J.; Moore, R. A.; Taylor, M. D.; Gerhard, D. S.; Jones, S. J. M.; Korshunov, A.; Gessler, M.; Kerl, K.; Hasselblatt, M.; Fruhwald, M. C.; Perlman, E. J.; Nelson, B. H.; Pfister, S. M.; Marra, M. A.; Kool, M., Identification and Analyses of Extra-Cranial and Cranial Rhabdoid Tumor Molecular Subgroups Reveal Tumors with Cytotoxic T Cell Infiltration. Cell Rep 2019, 29 (8), 2338-2354 e7. [CrossRef]

- Forrest, S. J.; Al-Ibraheemi, A.; Doan, D.; Ward, A.; Clinton, C. M.; Putra, J.; Pinches, R. S.; Kadoch, C.; Chi, S. N.; DuBois, S. G.; Leavey, P. J.; LeBoeuf, N. R.; Mullen, E.; Collins, N.; Church, A. J.; Janeway, K. A., Genomic and Immunologic Characterization of INI1-Deficient Pediatric Cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2020, 26 (12), 2882-2890. [CrossRef]

- Pecci, F.; Cognigni, V.; Giudice, G. C.; Paoloni, F.; Cantini, L.; Saini, K. S.; Abushukair, H. M.; Naqash, A. R.; Cortellini, A.; Mazzaschi, G.; Alia, S.; Membrino, V.; Araldi, E.; Tiseo, M.; Buti, S.; Vignini, A.; Berardi, R., Unraveling the link between cholesterol and immune system in cancer: From biological mechanistic insights to clinical evidence. A narrative review. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2025, 209, 104654. [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Wen, X.; Qin, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, T.; Di, Y.; He, W., Metabolism-regulated ferroptosis in cancer progression and therapy. Cell Death & Disease 2024, 15 (3), 196. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Xu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, X.; Shi, S., Functional significance of cholesterol metabolism in cancer: from threat to treatment. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2023, 55 (9), 1982-1995. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, F.; Yokogami, K.; Yamada, A.; Moritake, H.; Watanabe, T.; Yamashita, S.; Sato, Y.; Takeshima, H., Targeting cholesterol biosynthesis for AT/RT: comprehensive expression analysis and validation in newly established AT/RT cell line. Hum Cell 2024, 37 (2), 523-530. [CrossRef]

- A Phase 1 Study Using Simvastatin in Combination With Topotecan and Cyclophosphamide in Relapsed and/or Refractory Pediatric Solid and CNS Tumors. Children's Healthcare of, A., Ed. 2015.

- Kes, M. M. G.; Morales-Rodriguez, F.; Zaal, E. A.; de Souza, T.; Proost, N.; van de Ven, M.; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M. M.; Jansen, J. W. A.; Berkers, C. R.; Drost, J., Metabolic profiling of patient-derived organoids reveals nucleotide synthesis as a metabolic vulnerability in malignant rhabdoid tumors. Cell Reports Medicine 2025, 6 (1), 101878. [CrossRef]

- Kenny, C.; O'Meara, E.; Ulas, M.; Hokamp, K.; O'Sullivan, M. J., Global Chromatin Changes Resulting from Single-Gene Inactivation-The Role of SMARCB1 in Malignant Rhabdoid Tumor. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13 (11). [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lee, R. S.; Alver, B. H.; Haswell, J. R.; Wang, S.; Mieczkowski, J.; Drier, Y.; Gillespie, S. M.; Archer, T. C.; Wu, J. N.; Tzvetkov, E. P.; Troisi, E. C.; Pomeroy, S. L.; Biegel, J. A.; Tolstorukov, M. Y.; Bernstein, B. E.; Park, P. J.; Roberts, C. W., SMARCB1-mediated SWI/SNF complex function is essential for enhancer regulation. Nat Genet 2017, 49 (2), 289-295. [CrossRef]

- Hoy, S. M., Tazemetostat: First Approval. Drugs 2020, 80 (5), 513-521. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Troisi, E. C.; Howard, T. P.; Haswell, J. R.; Wolf, B. K.; Hawk, W. H.; Ramos, P.; Oberlick, E. M.; Tzvetkov, E. P.; Ross, A.; Vazquez, F.; Hahn, W. C.; Park, P. J.; Roberts, C. W. M., BRD9 defines a SWI/SNF sub-complex and constitutes a specific vulnerability in malignant rhabdoid tumors. Nat Commun 2019, 10 (1), 1881. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Ogiwara, H., Efficacy of glutathione inhibitor eprenetapopt against the vulnerability of glutathione metabolism in SMARCA4-, SMARCB1- and PBRM1-deficient cancer cells. Scientific Reports 2024, 14 (1), 31321. [CrossRef]

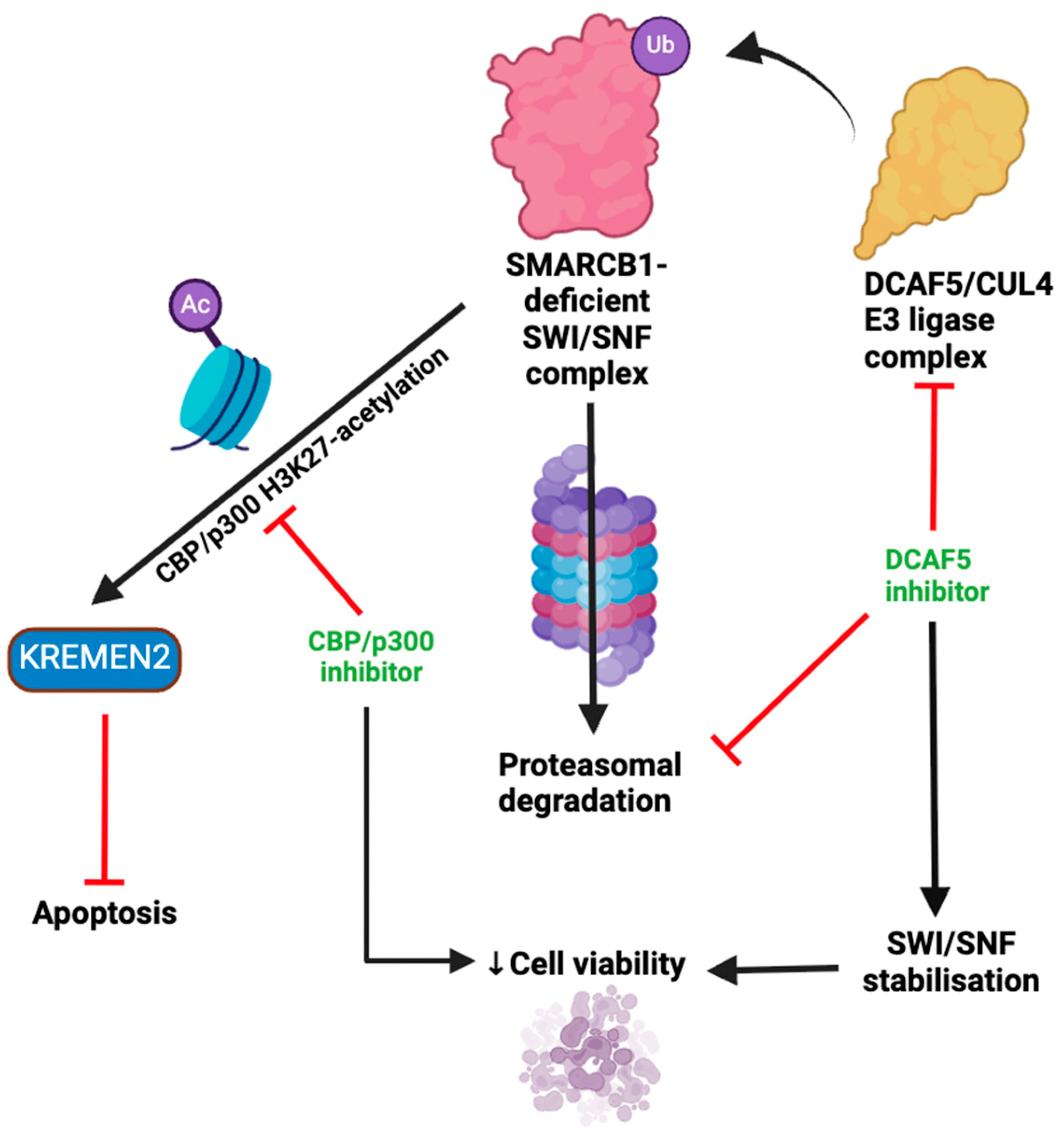

- Sasaki, M.; Kato, D.; Murakami, K.; Yoshida, H.; Takase, S.; Otsubo, T.; Ogiwara, H., Targeting dependency on a paralog pair of CBP/p300 against de-repression of KREMEN2 in SMARCB1-deficient cancers. Nature Communications 2024, 15 (1), 4770. [CrossRef]

- Mao, B.; Wu, W.; Davidson, G.; Marhold, J.; Li, M.; Mechler, B. M.; Delius, H.; Hoppe, D.; Stannek, P.; Walter, C.; Glinka, A.; Niehrs, C., Kremen proteins are Dickkopf receptors that regulate Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Nature 2002, 417 (6889), 664-7. [CrossRef]

- Sumia, I.; Pierani, A.; Causeret, F., Kremen1-induced cell death is regulated by homo- and heterodimerization. Cell Death Discov 2019, 5, 91. [CrossRef]

- Marhelava, K.; Pilch, Z.; Bajor, M.; Graczyk-Jarzynka, A.; Zagozdzon, R., Targeting Negative and Positive Immune Checkpoints with Monoclonal Antibodies in Therapy of Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11 (11). [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, M.; Nie, H.; Yuan, Y., PD-1 and PD-L1 in cancer immunotherapy: clinical implications and future considerations. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2019, 15 (5), 1111-1122. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. C.; Ssu, C. T.; Tsao, Y. P.; Liou, T. L.; Tsai, C. Y.; Chou, C. T.; Chen, M. H.; Leu, C. M., Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4-Ig (CTLA-4-Ig) suppresses Staphylococcus aureus-induced CD80, CD86, and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in human B cells. Arthritis Res Ther 2020, 22 (1), 64. [CrossRef]

- Bolm, L.; Petruch, N.; Sivakumar, S.; Annels, N. E.; Frampton, A. E., Gene of the month: T-cell immunoreceptor with immunoglobulin and ITIM domains (TIGIT). J Clin Pathol 2022, 75 (4), 217-221. [CrossRef]

- Davis, K. L.; Fox, E.; Isikwei, E.; Reid, J. M.; Liu, X.; Minard, C. G.; Voss, S.; Berg, S. L.; Weigel, B. J.; Mackall, C. L., A Phase I/II Trial of Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Children and Young Adults with Relapsed/Refractory Solid Tumors: A Children's Oncology Group Study ADVL1412. Clin Cancer Res 2022, 28 (23), 5088-5097. [CrossRef]

- Phase 2 Proof of Concept Study of Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Children and Young Adults With Relapsed or Refractory INI1-negative Cancers. Gateway for Cancer, R., Ed. 2020.

- Nutsch, K.; Banta, K. L.; Wu, T. D.; Tran, C. W.; Mittman, S.; Duong, E.; Nabet, B. Y.; Qu, Y.; Williams, K.; Muller, S.; Patil, N. S.; Chiang, E. Y.; Mellman, I., TIGIT and PD-L1 co-blockade promotes clonal expansion of multipotent, non-exhausted antitumor T cells by facilitating co-stimulation. Nat Cancer 2024, 5 (12), 1834-1851. [CrossRef]

- A Phase 1/2 Study of Tiragolumab (NSC# 827799) and Atezolizumab (NSC# 783608) in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory SMARCB1 or SMARCA4 Deficient Tumors. 2022.

- Kang, N.; Eccleston, M.; Clermont, P. L.; Latarani, M.; Male, D. K.; Wang, Y.; Crea, F., EZH2 inhibition: a promising strategy to prevent cancer immune editing. Epigenomics 2020, 12 (16), 1457-1476. [CrossRef]

- TAZNI: a Phase I/II Combination Trial of Tazemetostat with Nivolumab and Ipilimumab for Children with INI1-Negative or SMARCA4-Deficient Tumors. Bristol-Myers, S.; Epizyme, I., Eds. 2022.

- Sterner, R. C.; Sterner, R. M., CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer Journal 2021, 11 (4), 69. [CrossRef]

- Dabas, P.; Danda, A., Revolutionizing cancer treatment: a comprehensive review of CAR-T cell therapy. Med Oncol 2023, 40 (9), 275. [CrossRef]

- A Multicenter, Open-label, Uncontrolled Phase II Study to Investigate Efficacy and Safety of ONO4538 in Patients With Rhabdoid Tumor. 2024.

- Immunotherapy for Malignant Pediatric Brain Tumors Employing Adoptive Cellular Therapy (IMPACT). 2023.

- Loc3CAR: Locoregional Delivery of B7-H3-specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor Autologous T Cells for Pediatric Patients With Primary CNS Tumors. 2023.

- B7-H3-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor Autologous T-Cell Therapy for Pediatric Patients With Solid Tumors (3CAR). 2021.

- Phase 1 Study of B7-H3-Specific CAR T Cell Locoregional Immunotherapy for Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma/Diffuse Midline Glioma and Recurrent or Refractory Pediatric Central Nervous System Tumors. 2019.

- Phase I Study of EGFR806 CAR T Cell Immunotherapy for Recurrent/Refractory Solid Tumors in Children and Young Adults. 2018.

- Phase I Study of B7H3 CAR T Cell Immunotherapy for Recurrent/Refractory Solid Tumors in Children and Young Adults. 2020.

- Esteller, M.; Dawson, M. A.; Kadoch, C.; Rassool, F. V.; Jones, P. A.; Baylin, S. B., The Epigenetic Hallmarks of Cancer. Cancer Discov 2024, 14 (10), 1783-1809. [CrossRef]

- Sadida, H. Q.; Abdulla, A.; Marzooqi, S. A.; Hashem, S.; Macha, M. A.; Akil, A. S. A.; Bhat, A. A., Epigenetic modifications: Key players in cancer heterogeneity and drug resistance. Transl Oncol 2024, 39, 101821. [CrossRef]

- A Phase 1 Study of the EZH2 Inhibitor Tazemetostat in Pediatric Subjects With Relapsed or Refractory INI1-Negative Tumors or Synovial Sarcoma. 2015.

- Chi, S. N.; Bourdeaut, F.; Casanova, M.; Kilburn, L. B.; Hargrave, D. R.; McCowage, G. B.; Pinto, N. R.; Yang, J.; Chadha, R.; Kahali, B.; Tapia, C.; Nysom, K., Update on phase 1 study of tazemetostat, an enhancer of zeste homolog 2 inhibitor, in pediatric patients with relapsed or refractory integrase interactor 1–negative tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology 40 (16_suppl), 10040-10040. [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Da, Y.; Xue, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zhuang, H.; Peng, M.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Simard, A.; Hao, J.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, R., Vorinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, suppresses dendritic cell function and ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Exp Neurol 2013, 241, 56-66. [CrossRef]

- A Phase I Study of SAHA and Temozolomide in Children With Relapsed or Refractory Primary Brain or Spinal Cord Tumors. 2010.

- Hummel, T. R.; Wagner, L.; Ahern, C.; Fouladi, M.; Reid, J. M.; McGovern, R. M.; Ames, M. M.; Gilbertson, R. J.; Horton, T.; Ingle, A. M.; Weigel, B.; Blaney, S. M., A pediatric phase 1 trial of vorinostat and temozolomide in relapsed or refractory primary brain or spinal cord tumors: a Children's Oncology Group phase 1 consortium study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013, 60 (9), 1452-7. [CrossRef]

- Nemes, K.; Johann, P. D.; Tüchert, S.; Melchior, P.; Vokuhl, C.; Siebert, R.; Furtwängler, R.; Frühwald, M. C., Current and Emerging Therapeutic Approaches for Extracranial Malignant Rhabdoid Tumors. Cancer Manag Res 2022, 14, 479-498. [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Huang, C.; Liu, K.; Li, X.; Dong, Z., Targeting AURKA in Cancer: molecular mechanisms and opportunities for Cancer therapy. Molecular Cancer 2021, 20 (1), 15. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyaya, S.; Campagne, O.; Robinson, G. W.; Onar-Thomas, A.; Orr, B.; Billups, C. A.; Tatevossian, R. G.; Broniscer, A.; Kilburn, L. B.; Baxter, P. A.; Smith, A. A.; Crawford, J.; Partap, S.; Ellison, D. W.; Stewart, C. F.; Patay, Z.; Gajjar, A. J., Phase II study of alisertib as a single agent in recurrent or progressive atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology 38 (15_suppl), 10542-10542. [CrossRef]

- Green, A. L.; Minard, C. G.; Liu, X.; Safgren, S. L.; Pinkney, K.; Harris, L.; Link, G.; DeSisto, J.; Voss, S.; Nelson, M. D.; Reid, J. M.; Fox, E.; Weigel, B. J.; Glade Bender, J., Phase 1 trial of selinexor in pediatric recurrent/refractory solid and CNS tumors (ADVL1414): A Children's Oncology Group Phase 1 Consortium Trial. Clin Cancer Res 2025. [CrossRef]

- Geoerger, B.; Bourdeaut, F.; DuBois, S. G.; Fischer, M.; Geller, J. I.; Gottardo, N. G.; Marabelle, A.; Pearson, A. D. J.; Modak, S.; Cash, T.; Robinson, G. W.; Motta, M.; Matano, A.; Bhansali, S. G.; Dobson, J. R.; Parasuraman, S.; Chi, S. N., A Phase I Study of the CDK4/6 Inhibitor Ribociclib (LEE011) in Pediatric Patients with Malignant Rhabdoid Tumors, Neuroblastoma, and Other Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2017, 23 (10), 2433-2441. [CrossRef]

- Phase I/II Multicenter Study to Assess Efficacy and Safety of Ribociclib (LEE011) in Combination With Topotecan and Temozolomide (TOTEM) in Pediatric Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Neuroblastoma and Other Solid Tumors. Innovative Therapies For Children with Cancer, C., Ed. 2022.

- A Multi-Center Phase II Study of Selinexor in Treating Recurrent or Refractory Wilms Tumor and Other Pediatric Solid Tumors. 2023.

- PHASE 1/2 STUDY TO EVALUATE PALBOCICLIB (IBRANCE®) IN COMBINATION WITH IRINOTECAN AND TEMOZOLOMIDE OR IN COMBINATION WITH TOPOTECAN AND CYCLOPHOSPHAMIDE IN PEDIATRIC PATIENTS WITH RECURRENT OR REFRACTORY SOLID TUMORS. Children's Oncology, G., Ed. 2018.

- Cesur-Ergün, B.; Demir-Dora, D., Gene therapy in cancer. J Gene Med 2023, 25 (11), e3550. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. S.; Moghe, M.; Rait, A.; Donaldson, K.; Harford, J. B.; Chang, E. H., SMARCB1 Gene Therapy Using a Novel Tumor-Targeted Nanomedicine Enhances Anti-Cancer Efficacy in a Mouse Model of Atypical Teratoid Rhabdoid Tumors. Int J Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 5973-5993. [CrossRef]

- McDermott, J.; Sturtevant, D.; Kathad, U.; Varma, S.; Zhou, J.; Kulkarni, A.; Biyani, N.; Schimke, C.; Reinhold, W. C.; Elloumi, F.; Carr, P.; Pommier, Y.; Bhatia, K., Artificial intelligence platform, RADR®, aids in the discovery of DNA damaging agent for the ultra-rare cancer Atypical Teratoid Rhabdoid Tumors. Frontiers in Drug Discovery 2022, 2. [CrossRef]

| Trial number | Phase | SMARCB-1 targeting therapies | Disorder | Target | Status | Sites | Primary outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT05985161 [80] | II | Selinexor | Solid tumours including RT | Exportin-1 | Recruiting | Various USA sites. | Complete and partial response |

| NCT05429502 [79] | I/II | Ribociclib | Solid tumours including RT | CDK4/6 | Recruiting | USA, UK, Spain, Singapore, Italy, Germany, France, and Australia. | Overall response rate and dose-limiting toxicities |

| NCT03709680 [81] | I/II | Palbociclib | Recurrent/refractory solid tumours including RT | CDK4/6 | Active, not recruiting | > 10 countries including USA, UK, Brazil, and Korea. | Event-free survival, first cycle dose-limiting toxicities, frequency of adverse events, complete response or partial response |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).