1. Introduction

Information security has become a focal point, and cryptographic techniques are increasingly prevalent. Under resource constraints, lightweight block ciphers are widely used due to their simple architecture, high efficiency, and ease of implementation. Common lightweight block ciphers include PRESENT [

1], GIFT, SKINNY [

2], LED [

3], and CRAFT [

4], etc..

Fault Analysis (FA) is a specialized form of side-channel analysis that can be considered an active analysis method targeting physical cryptographic embedded devices [

5]. It involves executing fault injection on a device to force it into an abnormal state and analyzing the collected faulty ciphertexts to recover keys using knowledge of the cryptographic algorithm. Fault injection can be achieved by altering power voltage [

6], external clock frequency [

7], temperature [

8], or exposing circuits to lasers [

9] during key scheduling or encryption. There is also the permanent fault model, where attackers employ more aggressive means to damage cryptographic devices, resulting in persistent faults [

9].

Fault injection and its accompanying analysis techniques are among the most effective methods for analyzing cryptographic devices. The most renowned analysis technique in this field was the Differential Fault Analysis (DFA) that utilize the differences between the correct and faulty ciphertexts from fixed inputs to recover keys [

10]. In 2010, Courtois et al. proposed Algebraic Fault Analysis (AFA) [

11], combining fault analysis with algebraic analysis. It translates differential fault information into algebraic equations and integrates them with encryption algorithms. In 2018, Zhang et al. introduced a novel fault analysis method called Persistent Fault Analysis (PFA) [

12]. Their fault model lies between transient and permanent faults. Faults are injected into algorithm constants stored in memory (ROM), such as an element within an S-box. Unless ROM is refreshed, the fault persists through all subsequent encryptions, affecting rounds accessing the specific faulty S-box element, and disappears once the fault-injected device is reset. PFA primarily conducts statistical analysis on the value distribution of ciphertext bytes and can be used as a ciphertext-only cryptanalysis method.

In 2022, Zhang et al. introduced APFA [

13], merging the persistent fault model with algebraic fault analysis. Faults are injected into S-boxes stored in memory, causing a deviation in one element. Since S-box data is bijective, data passing through the S-box during encryption deviates after fault injection, significantly enhancing the solving success rate and efficiency of algebraic analysis. Fang et al. decomposed 4-bit S-boxes into two 2-bit S-boxes, reducing intermediate variable usage and effectively enhancing solving efficiency [

14].

The equation systems constructed in APFA are in the satisfiability problem (SAT) form that can be solved by Off-the-shelf SAT solvers, such as CryptoMiniSAT [

15]. The SAT inputs consist of clauses in conjunctive normal form (CNF), where clauses are connected by conjunction ∧. Each clause comprises literals connected by disjunction ∨, with each literal being either a positive or negative variable. Additionally, CryptoMiniSAT supports XOR syntax inputs, offering convenience in equation transformation. Previous APFA research describes S-boxes by Tseitin transformation to decompose higher-degree terms into linear combinations. Conjunctive normal form is then used to depict the Boolean relationships of all valid input-output pairs [

16]. This approach necessitates numerous intermediate variables to construct data relationships before and after S-boxes [

13,

14]. Studies have shown that CNF clauses generated by the Logic Friday tool exhibit significant advantages in SAT solvers, reducing clause redundancy compared to traditional Tseitin transformation [

17].

Motivations. Prior APFA research overlooked the implications of faulty S-boxes during the key scheduling process. Our investigation reveals that prominent cryptographic standards like AES [

18] and PRESENT [

1] incorporate S-boxes into their key scheduling algorithms, leveraging the same S-box implementation as the encryption stage [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. This previously unaddressed challenge necessitates a comprehensive extension of APFA to encompass the key scheduling phase. In this paper, we present our investigation and findings on extending algebraic persistent fault analysis to encompass the key scheduling stage of cryptographic algorithms.

Our Contributions

We extend fault injection and analysis to the key scheduling stage, discovering that algebraic persistent fault analysis remains applicable, but find that it comes with two challenges. Firstly, it introduces uncertainty. Deviating from the definition of bijection of S-box, round keys can no longer be traced back to a unique master key, making it difficult to reduce key search space to a single solution. Secondly, the constructed algebraic equations are larger and more complex, demanding higher solving efficiency. Increasing the depth of fault analysis can reduce uncertainty and consequently shrink the key search space, thus leveraging the first problem. However, increased depth results in larger algebraic equations, necessitating improved solving efficiency to address the second problem. Our main contributions are as follows:

Using the 80-bit version of PRESENT as an example, we extend APFA fault injection and analysis to the S-box in the key scheduling stage with compact S-box modeling. Experiments demonstrate that algebraic persistent fault analysis remains applicable when delving into the key scheduling stage. The key search space is difficult to reduce to a single solution; increasing fault analysis depth can shrink the key search space. Experiments show that when the fault analysis encompasses the entire key scheduling and encryption processes, the key search space can approach uniqueness.

Since the descriptions of S-boxes account for significant computational resources consumed for solving the SAT problem in APFA, we propose a truth table-based optimization method for S-box modeling. By representing S-boxes with optimized truth tables and utilizing the Logic Friday tool, S-boxes are converted into CNF representation, reducing clause count and eliminating the need for auxiliary variables. Compared to previous construction methods, our algebraic construction significantly enhances solving efficiency in APFA, especially in high-complexity scenarios. For PRESENT, SKINNY, and CRAFT encryption algorithms, the required number of variables and clauses to establish complete algebraic equations are nearly halved, with solving efficiency improved by tens or even hundreds of times. Besides, we discovered that if solving time is constrained, improved efficiency also translates to higher solving success rates.

2. Background

2.1. Notation Table

Table 1 defines the notations used in this paper.

2.2. Lightweight Block Ciphers in SPN Structure

We use PRESENT [

1], SKINNY [

2], and CRAFT [

4] as our target block ciphers. The Substitution-Permutation Network (SPN) is an iterative core structure used in block ciphers, achieving encryption strength through alternating nonlinear substitution (Substitution) and linear permutation (Permutation) operations over multiple rounds. A standard SPN structure consists of

R iterative rounds, each comprising three core operations:

AddRoundKey (AK): The round key is XORed with the intermediate state, introducing key dependency.

Substitution Layer (SB): The parallel S-boxes perform nonlinear transformations on fixed-length data blocks. Typically 4-bit S-box is used in lightweight block ciphers.

Permutation Layer (PL): The substituted bits are deterministically rearranged to achieve diffusion across S-boxes. Common strategies include: (1) ShiftRows: Cyclic shifts by rows (e.g., SKINNY). (2) Bit Permutation: Fixed position mapping (e.g., PRESENT’s 64-bit permutation matrix). (3) MixColumns: Linear transformation based on a finite field (e.g., CRAFT’s MDS matrix can be implemented using XOR operations).

The typical algorithm structure is

.

Table 2 compares the core parameters of PRESENT, SKINNY, and CRAFT. All three use 4-bit S-boxes, with the specific input-output mappings shown in

Table 3. CRAFT’s tweak key (

) is used alongside the master key (

) in key scheduling.

The key scheduling algorithm for PRESENT-80, with a key size of 80 bits, is shown in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1 Key schedule of PRESENT-80 |

-

Input:

80-bit master key

-

Output:

64-bit round keys

- 1:

- 2:

for to 31 do

- 3:

- 4:

▹ Cyclic left shift by 61 bits - 5:

▹ Substitute the top 4 bits - 6:

▹ XOR with 5-bit round counter - 7:

end for - 8:

|

2.3. Algebraic Persistent Fault Analysis

The construction of APFA [

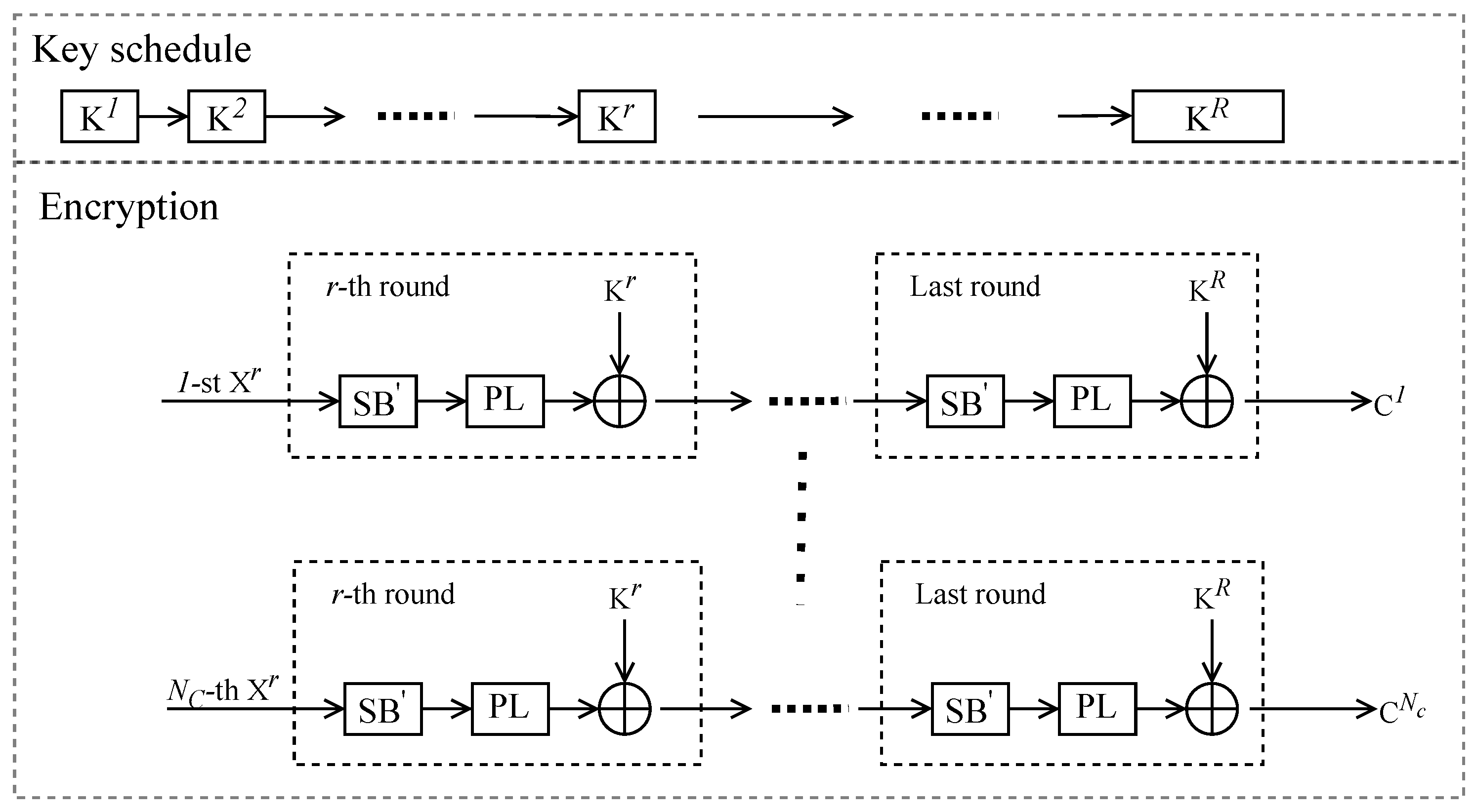

13] algebraic equations should launch multiple encryptions using the same key, as is illustrated in

Figure 1. APFA is a ciphertext-only cryptanalysis method, operating as follows:

An attacker injects a small fault into the S-box of an encryption device, affecting the output of one of its mappings and rendering the S-box’s mapping unbalanced. The faulty S-box () persists through multiple encryption rounds. The fault information in includes the fault location (l) and fault value (f), where .

The victim encrypts multiple plaintexts using a fixed key on the faulty encryption device.

The attacker collects ciphertexts containing fault information and establishes a system of algebraic equations based on the relationship between the key, encryption process, and fault information of the S-box.

SAT solving tools are used to solve the equations. If successful, the solution reveals the master key.

For the faulty S-box

, assume the fault occurs at

(fault location

l, i.e., the

l-th byte of

S), causing

to become

. Consequently, for each round’s

, it holds that

. This inequality is represented by CNF in Equation (

1) and (2), where

means the

j-th bit of

d. Since

s can not be 0 simultaneously, there must be at least one bit

that is not zero, indicating that

.

3. Extending APFA to the Key Scheduling Phase

In this section, we explore the effects of extending the faulty S-box to the key scheduling phase. Our experiments and analyses confirm that APFA remains effective when fault injection and analysis are extended to the key scheduling process.

3.1. Implementation with Shared S-box

When translating encryption algorithms from theory to practice, circuit implementations vary according to specific requirements. If throughput is prioritized, designs may consider executing the same operations in parallel, such as replicating S-boxes to allow parallel data processing through multiple S-boxes, thus enhancing efficiency. Conversely, to minimize the area of implementation circuits, reducing the number of implemented S-boxes is a viable approach. In circuit implementations of encryption devices, a single instance of an S-box may suffice, reducing circuit scale, with all related data passing through the S-box sequentially. Designs for AES [

19,

20] and PRESENT [

21,

22,

23] reflect such considerations.

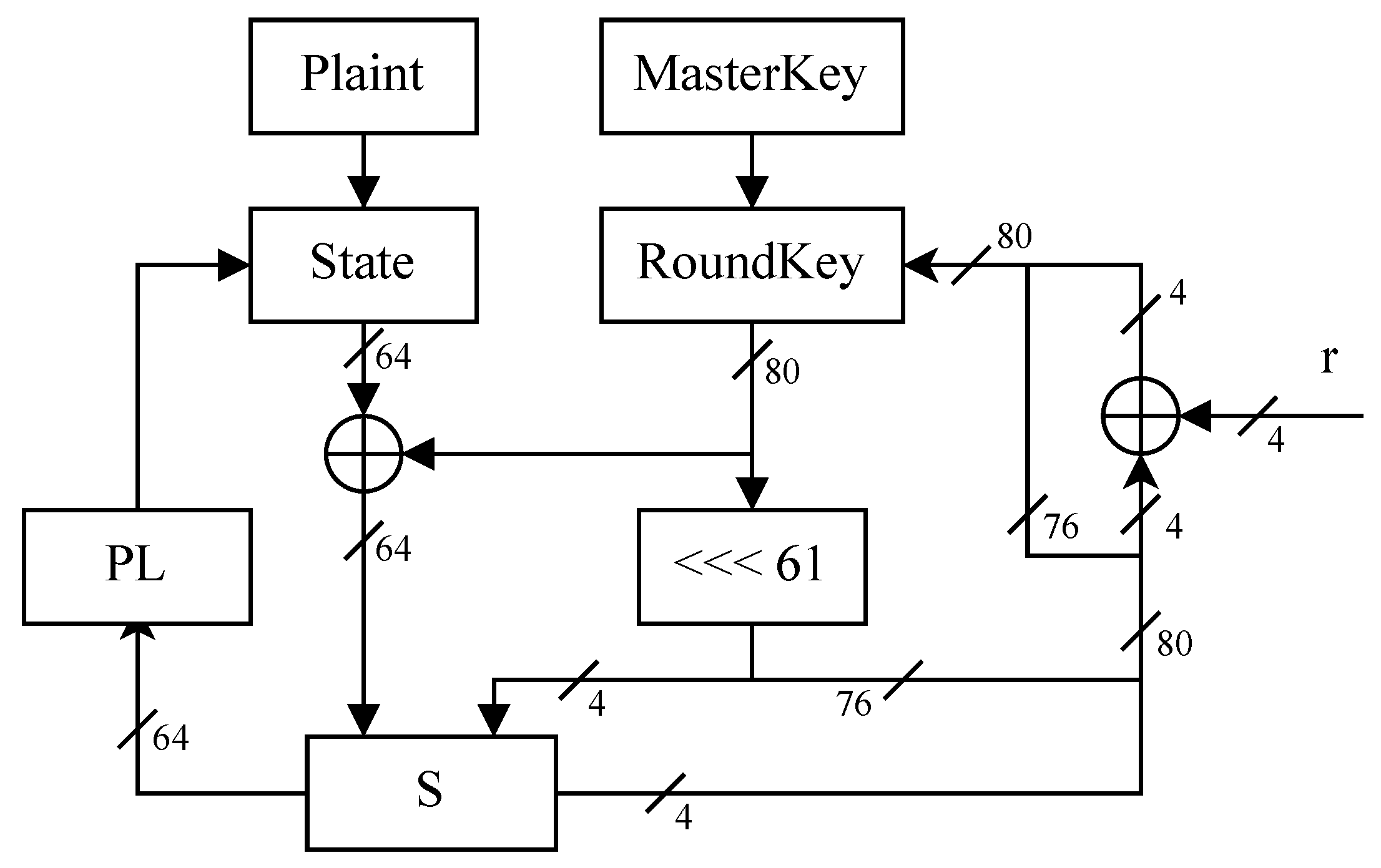

Practical circuits balance throughput and area based on requirements. For the PRESENT encryption algorithm’s implementation, we assume a single S-box instance is used, with the key scheduling and encryption phases serially utilizing this S-box. A simplified representation of the data flow in its serial circuit construction is shown in

Figure 2, where

r denotes the current round.

Focusing on the PRESENT encryption algorithm, where the key scheduling process requires the same S-box as used in encryption, we extend APFA fault injection to the key scheduling phase, assuming only one S-box instance in the circuit. Fault injection into the S-box affects both the encryption and key scheduling SB operations.

The use of a faulty S-box in the key scheduling phase significantly increases the scale and complexity of the algebraic system. We propose a new algebraic construction method for the S-box that greatly improves solving efficiency. Due to the structure of this paper, the introduction and effects of this method are discussed in

Section 4.2 and

Section 5, respectively.

Our primary focus is on the feasibility of extending APFA to the key scheduling phase. Given the superior performance of our algebraic construction method, this section discusses extending APFA to the key scheduling phase using our proposed S-box modeling method exclusively.

3.2. Experimental Setup

We assume the key scheduling and encryption processes use the same faulty S-box instance. For the PRESENT encryption algorithm, using the faulty S-box

(Note that originally

). Compared to the initial APFA, extending to the key scheduling phase requires reflecting the S-box fault information during key scheduling. The complete process is detailed in Algorithm 2.

|

Algorithm 2 APFA on 80-Bit PRESENT (Key schedule using faulty S-box) |

-

Input:

-

Output:

▹ Output: Recovered master key - 1:

▹ Store original S-box value - 2:

▹ Inject fault at S-box position l

- 3:

for ; ; do

- 4:

▹ Normal key scheduling constraints - 5:

▹ Faulty S-box constraints - 6:

end for - 7:

for do

- 8:

for ; ; do ▹ Analyze the last encryption rounds - 9:

▹ S-box substitution constraints - 10:

▹ Faulty S-box constraints - 11:

▹ Permutation layer constraints - 12:

- 13:

end for

- 14:

▹ Bind ciphertext to final state - 15:

end for - 16:

▹ Invoke solver to recover key |

Here, “genKeyScheduleFaultConstraints” and “genFaultSBoxConstraints” represent constraints related to the faulty S-box during key scheduling and encryption, respectively, i.e., .

Extending APFA to the key scheduling phase, the algebraic equation system includes the following constraints:

Multiple encryptions use the same key.

Constraints of the key scheduling process (using the faulty S-box). Since multiple encryptions use the same key, this constraint needs to be added only once.

Constraints of the encryption process (using the faulty S-box).

Additional constraints on the faulty S-box (the mapped value of the original S-box at the fault location cannot appear in the data output through the faulty S-box, i.e., ). This additional constraint must be added whenever data passes through a faulty S-box.

3.3. Results with Faulty S-box in Key Schedule

In our experiments, we simulated fault injection using software and employed CryptoMiniSAT v5.11.22 as the SAT solver to resolve algebraic equations. For fairness, we configured the solver to execute in a single-threaded mode. The experiments were conducted on a PC equipped with 32 GB of memory and a 3.5 GHz Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-13600KF CPU, utilizing an Ubuntu 24.04.4 virtual machine. The virtual machine was allocated 16 GB of memory and 8 processors.

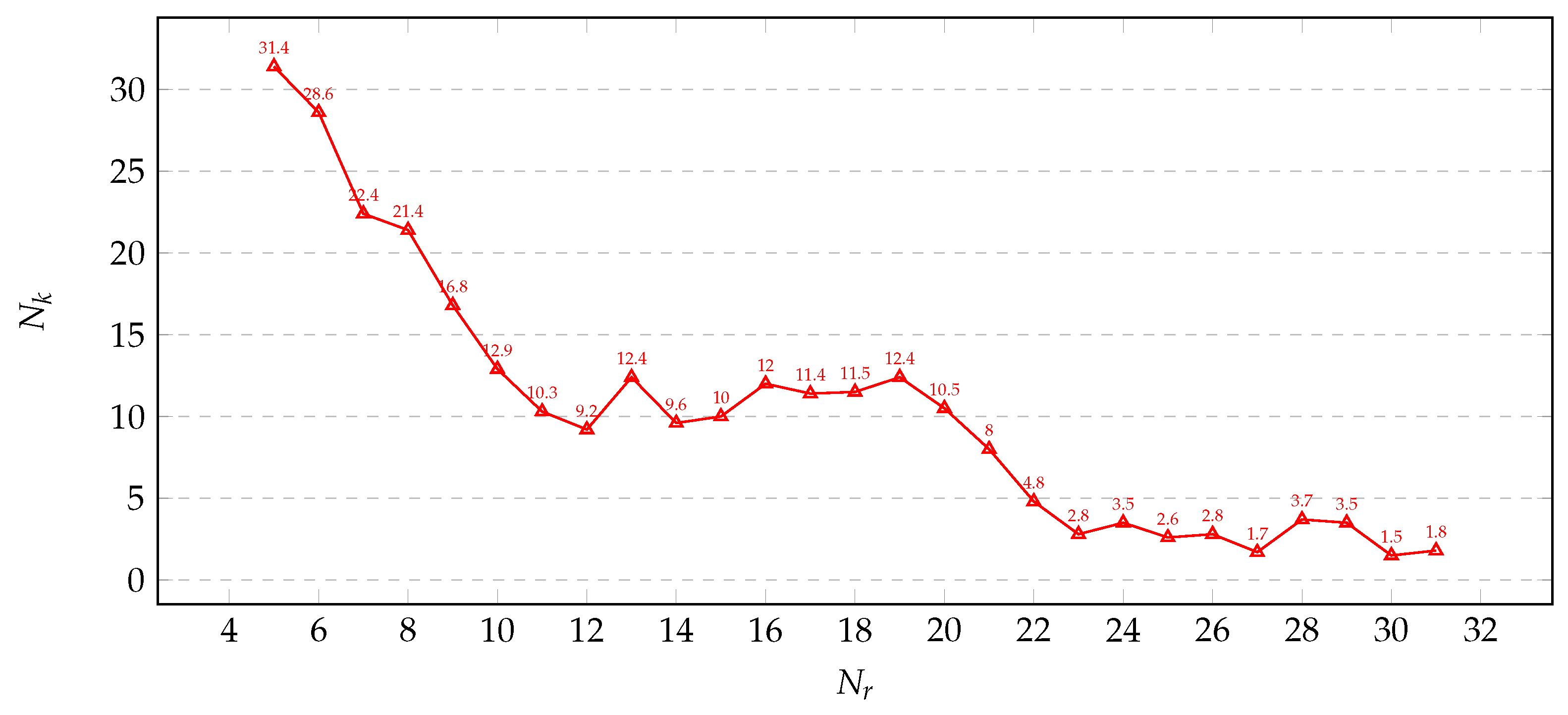

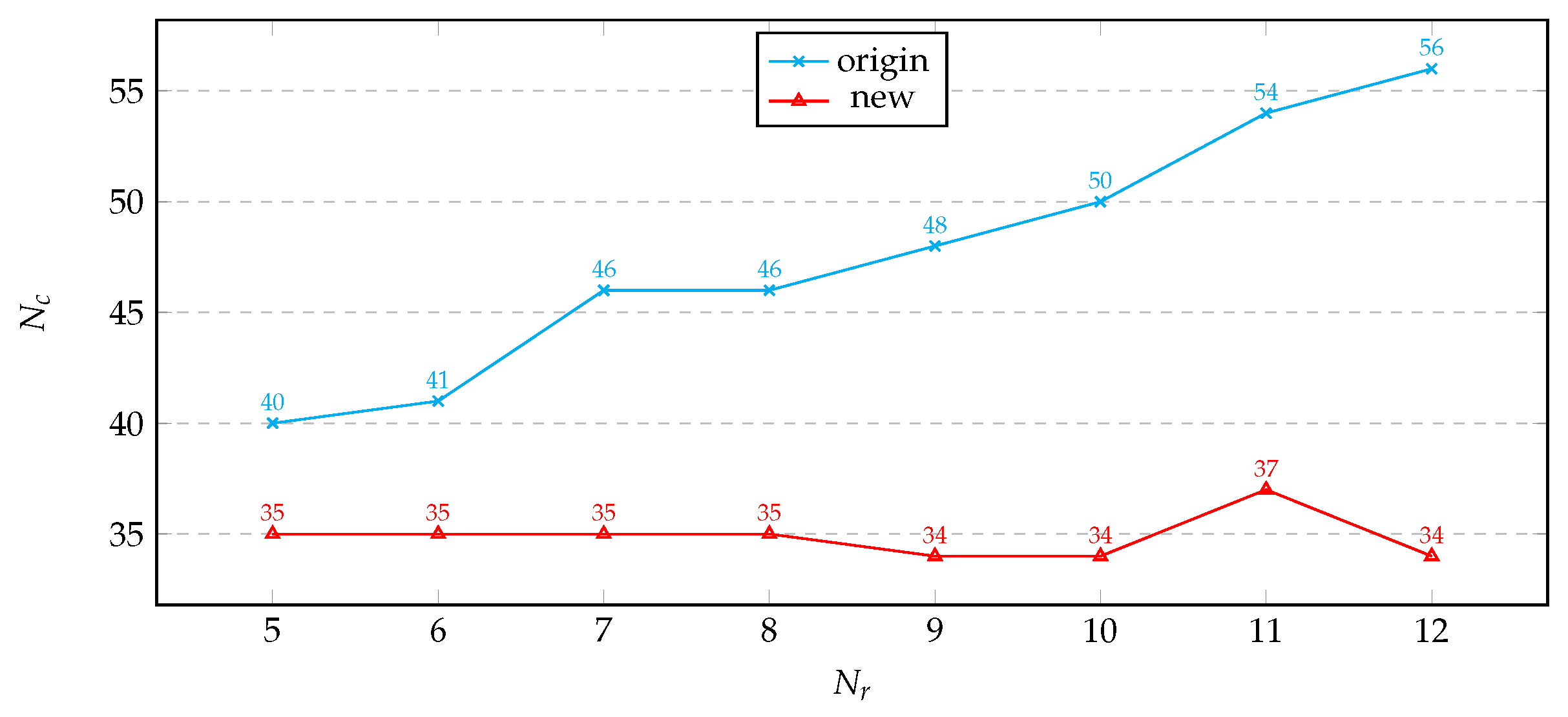

We measured the size of the master key search space after solving. As the depth of fault analysis increased from 5 to all encryption rounds, the average number of master key search space solutions obtained is shown in

Figure 3. As the fault depth increases, the size of the master key search space decreases. When fault analysis covers the entire encryption and key scheduling process, the key search space approaches uniqueness.

Since APFA is a ciphertext-only cryptanalysis method, it focuses solely on the last few rounds (equivalent to the fault analysis depth) of the encryption process. When constructing the system of algebraic equations, we include all key scheduling processes and the constraint equations corresponding to the last few rounds of encryption. Assuming a fault analysis depth of , if no faults exist in the key scheduling process, the round key for the -th round, , can be deduced uniquely and the unique master key () can be recovered accordingly.

However, if faults are injected into and the analysis is extended to the key scheduling process, uncertainty is also introduced into this process. Consequently, we are unable to make the search space for converge, which further complicates reducing the search space for the master key to a single solution.

Since the rules of key scheduling are deterministic, increasing the depth of fault analysis allows for a more in-depth examination, gradually eliminating the interference caused by faulty S-boxes, thereby reducing the search space of the master key. Ultimately, when , meaning the fault analysis covers the entire key scheduling and encryption processes, the search space for the master key is reduced to approach uniqueness. However, it still cannot fully converge because, for the first S-box encountered in the key scheduling process, there may be multiple inputs corresponding to the desired S-box output, a problem that remains unresolved.

4. Algebraic Construction of the S-Box

The solving efficiency of APFA is influenced by the scale of the algebraic equation system. In constructing the algebraic system, addition operations can be directly represented using XOR, while permutation operations are realized through variable mapping. The core challenge lies in the algebraic representation of the S-box, as its complexity directly impacts the processing efficiency of the SAT solver [

15]. This section introduces a novel method for S-box construction, with its innovation highlighted in

Section 4.2.

4.1. Classical ANF-CNF Conversion Method

The classical approach models the S-box by converting Algebraic Normal Form (ANF) to CNF. Taking the 4-bit S-box used in PRESENT as an example, assume

and

are the S-box input and output, respectively. The ANF representation of the S-box is expressed in Equation (

3). The AND operation is denoted by

, which may be omitted.

Each nonlinear term

requires the introduction of an intermediate variable

, establishing constraints as shown in Equation (

4). Each term can be considered an independent CNF clause.

For an S-box with n nonlinear terms, intermediate variables and CNF clauses are required. The original S-box in the PRESENT encryption algorithm requires 8 intermediate variables and 28 clauses for representation.

Assuming a 1-bit fault is injected into the S-box at fault location with fault value . Its algebraic representation requires 11 intermediate variables and 43 clauses.

While this method accurately models the S-box, the introduction of intermediate variables significantly increases the problem’s dimensionality, leading to a substantial expansion of the SAT solving space.

4.2. Truth Table-Based Optimized S-Box Modeling Method

We propose a direct modeling method based on truth table optimization. Let the S-box input be

and output

. Define a boolean function

, as shown in Equation (

5).

For a given faulty S-box, convert it into a truth table of a Boolean function, where possible patterns have a value of 1 and impossible patterns have a value of 0. This truth table is input into the Logic Friday software. By invoking the Quine-McCluskey algorithm, a CNF description can be output [

24]. The Espresso algorithm is used to simplify the sum-of-products representation [

25].

For the PRESENT encryption algorithm, using the faulty S-box

(Note that originally

), the truth table input to the Logic Friday tool is shown in

Table 4.

After data transformation and reduction by the tool, the resulting CNF data is shown in Equation (

6).

This algebraic construction method for the S-box does not require the introduction of additional auxiliary variables, and the results can be directly viewed as conforming to the format required by SAT solvers such as CryptoMiniSAT.

A comparison of the number of variables and clauses required for different S-box modeling methods is shown in

Table 5. For the faulty S-box, we uniformly assume a 1-bit fault is injected at location

with fault value

.

5. APFA with Compact S-Box Modeling

We applied APFA to the PRESENT, SKINNY, and CRAFT encryption algorithms, utilizing our algebraic representation of the S-box and comparing it to the traditional method. For the faulty S-box used in the encryption process, we assumed a 1-bit fault was injected at fault location with fault value .

5.1. APFA on PRESENT

We assumed that the S-boxes used in the key scheduling and encryption phases of PRESENT reside in different memory units, with only the S-box in the encryption phase being faulty. The S-box used in the encryption phase has a single instance, through which all data is processed sequentially.

We implemented APFA on both the 80-bit and 128-bit versions of the PRESENT encryption algorithm. For the S-box, we employed two different algebraic construction methods.

Using our S-box algebraic construction method, the number of variables and clauses required to construct the complete algebraic expression is significantly reduced under different fault analysis depths and numbers of faulty ciphertexts. For the 80-bit version of PRESENT, we set parameters

,

. The comparison with the original APFA is shown in

Table 6.

For the 128-bit version, we set parameters

,

. The comparison with the original APFA is shown in

Table 7.

We consider these parameters representative. In experiments, both S-box construction methods with these parameters can solve successfully in a relatively short time, facilitating comparison.

Our algebraic representation significantly reduces the solving time for APFA, and as increases, the advantage becomes more pronounced due to the expanding scale of the algebraic system.

5.2. APFA on SKINNY-64

We conducted APFA on three versions of the SKINNY-64 encryption algorithm. When the key length is 64 bits, both the original and our S-box construction methods successfully solve in a short time. For key lengths of 128 and 192 bits, due to our computational resource limitations, the original S-box construction method’s solving efficiency becomes highly unstable, often failing to solve within 24 hours. We only perform comparisons on SKINNY-64-64.

Using our S-box algebraic construction method, for a key length of 64 bits, we set parameters

,

. The comparison with the original APFA is shown in

Table 8.

Using our S-box algebraic construction method, we set the parameters as follows: for a key length of 128 bits,

and

; for a key length of 192 bits,

and

. The algebraic construction and the average solving time are detailed in

Table 9. For a key length of 192 bits, when

is set to 7, the key can always converge to a single-digit value, but it does not consistently converge to a unique value.

5.3. APFA on CRAFT

CRAFT uses a 128-bit key and a 64-bit tweak to generate four 64-bit round keys, which are cycled through during encryption. The key information is obfuscated by the tweak key, thus multiple possible keys exist, with the correct key among them. Alternatively, we can recover the total 256-bit round key, which is determinable, but multiple combinations of master key and tweak key can produce this round key.

We do not consider finding a unique solution as the termination condition. In the experiment, we increase or as much as possible, ultimately reducing the key search space to 16, marking this as a successful solution.

For the CRAFT encryption algorithm, we set the parameters

and

. The comparison with the original APFA is shown in

Table 10. When

reaches 11, using the original construction of the S-box, we are unable to find a solution within 5 days.

5.4. Exploration with Limited Solving Time

In practice, due to limitations in computing resources, we often cannot invest unlimited time in automated analysis. Typically, a maximum time is set, and if unsolved within this timeframe, it is considered a failure.

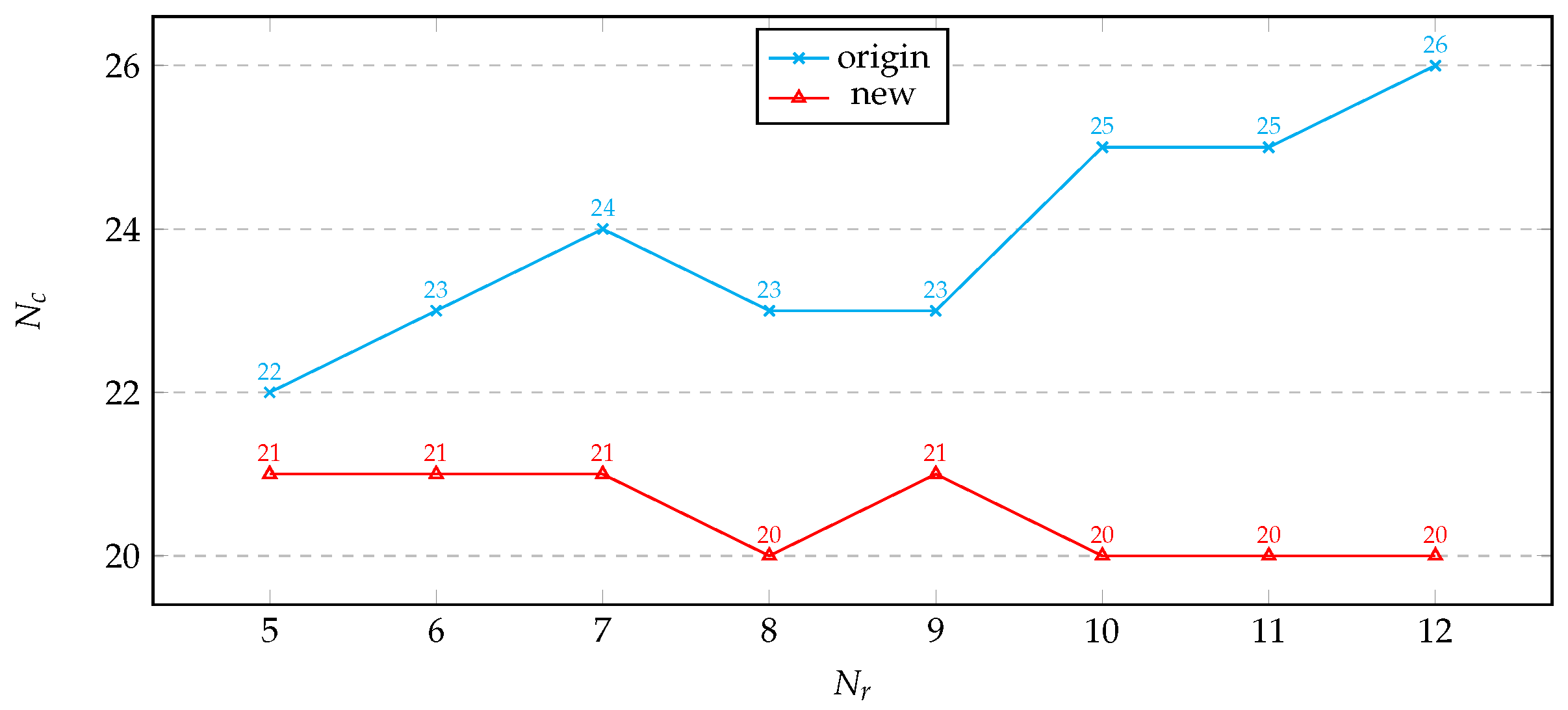

We set the SAT solver’s solving time to 3600s and conducted APFA on both versions of PRESENT. We gradually increased the fault analysis depth and recorded the number of ciphertexts required for successful solving within the time limit. The results are shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

Under the time constraint, it can be observed that as the fault analysis depth increases, the number of ciphertexts required for solving using the original S-box construction method tends to rise. In contrast, using our model to construct the S-box, the number of ciphertexts required remains stable.

At the same fault analysis depth, based on the principle of Boolean function equivalence, the algebraic properties of different S-box construction methods are essentially the same, as both describe the S-box [

26]. Theoretically, as the fault analysis depth increases, due to deeper analysis, the number of faulty ciphertexts required for successful solving using both S-box construction methods should decrease or remain stable, but should not rise.

With a constraint on solving time, aiming for a unique solution, an increase in faulty ciphertexts also means an increase in known conditions, which can improve solving efficiency and success rate. An increase in fault depth represents deeper exploration of faulty ciphertext information, which can also improve solving efficiency and success rate to some extent. However, both an increase in faulty ciphertexts and fault analysis depth lead to an increase in equation scale, requiring the solver to spend more time handling additional algebraic equations. These equations may not be necessary for successful solving, but the solver still needs to invest resources to verify them to ensure the results are not refuted by this information.

An increase in faulty ciphertexts has a linear impact on known conditions and equation scale. An increase in fault analysis depth has a linear impact on deep information exploration, but an exponential impact on equation scale. Each increase in fault analysis depth multiplies the complexity of the equation scale. Therefore, we believe there is a critical value for the impact of fault analysis depth on solving time. When the fault analysis depth is less than this value, an increase in depth means more efficient use of faulty ciphertexts, improving the success rate within the time limit, which is our main focus; when the depth exceeds this value, we focus more on the increase in solving time it brings.

Due to the relatively complex algebraic construction of the S-box in the original model, the problem scale becomes too large to solve within a limited time, necessitating an increase in ciphertext quantity to provide more "cost-effective" valid information. Using our S-box model, its algebraic construction is more conducive to the SAT solver extracting the key information contained within, and the critical value of fault analysis depth is much higher than that of the original S-box model, thus performing better in higher complexity scenarios.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we validated the feasibility of extending APFA fault injection and analysis to the key scheduling phase. Injecting faults into the key scheduling process presents challenges for cryptanalysis, making it difficult to recover the correct key. In such cases, increasing the depth of fault analysis can reduce the search space for the master key. For the 80-bit version of the PRESENT encryption algorithm, using 30 faulty ciphertexts in our experiments, we observed that as the fault analysis depth increased, the key search space decreased. When fault analysis covered the entire encryption process, the key search space converged to near uniqueness.

We proposed an optimized algebraic representation for S-boxes in APFA, utilizing a truth table-based optimized S-box modeling method that eliminates the need for auxiliary variables and offers superior performance. We implemented this improvement across various SPN-based block ciphers, achieving significant enhancements in APFA solving efficiency, with improvements ranging from tens to hundreds of times, and better adaptability to high-complexity scenarios.

This work highlights the potential of our improved APFA method in enhancing the applicability and efficiency of fault-based cryptanalysis, particularly when fault injection extends to the key scheduling phase. Future research could further explore the optimization of this approach and its application to other cryptographic algorithms and fault models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Q. and H.L.; methodology, H.L.; software, H.L.; validation, H.L., Y.X., C.O. and A.W.; formal analysis, H.L.; investigation, C.O.; resources, K.Q.; data curation, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L.; writing—review and editing, K.Q.; visualization, H.L.; supervision, A.W.; project administration, K.Q.; funding acquisition, K.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Cryptologic Science Fund of China (No. 2025NCSF02011), National Natural Science Foundation of China (62102025), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (4222035), and Beijing Institute of Technology Research Fund Program for Young Scholars (XSQD-202024003).

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and decision to publish results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| APFA |

Algebraic Persistent Fault Analysis |

| FA |

Fault Analysis |

| DFAD |

Differential Fault Analysis |

| AFA |

Algebraic Fault Analysis |

| PFA |

Persistent Fault Analysis |

| SAT |

satisfiability problem |

| CNF |

Conjunctive Normal Form |

| ANF |

Algebraic Normal Form |

References

- Bogdanov, A.; Knudsen, L.R.; Leander, G.; Paar, C.; Poschmann, A.; Robshaw, M.J.; Seurin, Y.; Vikkelsoe, C. PRESENT: An ultra-lightweight block cipher. In Proceedings of the Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems-CHES 2007: 9th International Workshop, Vienna, Austria, September 10-13, 2007. Proceedings 9. Springer, 2007, pp. 450–466.

- Beierle, C.; Jean, J.; Kölbl, S.; Leander, G.; Moradi, A.; Peyrin, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Sasdrich, P.; Sim, S.M. The SKINNY family of block ciphers and its low-latency variant MANTIS. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology–CRYPTO 2016: 36th Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, August 14-18, 2016, Proceedings, Part II 36. Springer, 2016, pp. 123–153.

- Guo, J.; Peyrin, T.; Poschmann, A.; Robshaw, M. The LED block cipher. In Proceedings of the Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems–CHES 2011: 13th International Workshop, Nara, Japan, September 28–October 1, 2011. Proceedings 13. Springer, 2011, pp. 326–341.

- Beierle, C.; Leander, G.; Moradi, A.; Rasoolzadeh, S. CRAFT: lightweight tweakable block cipher with efficient protection against DFA attacks. IACR Transactions on Symmetric Cryptology 2019, 2019.

- Joye, M.; Tunstall, M.; et al. Fault analysis in cryptography; Vol. 147, Springer, 2012.

- Barenghi, A.; Bertoni, G.M.; Breveglieri, L.; Pelosi, G. A fault induction technique based on voltage underfeeding with application to attacks against AES and RSA. Journal of Systems and Software 2013, 86, 1864–1878.

- Aumüller, C.; Bier, P.; Fischer, W.; Hofreiter, P.; Seifert, J.P. Fault attacks on RSA with CRT: Concrete results and practical countermeasures. In Proceedings of the Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems-CHES 2002: 4th International Workshop Redwood Shores, CA, USA, August 13–15, 2002 Revised Papers 4. Springer, 2003, pp. 260–275.

- Hutter, M.; Schmidt, J.M. The temperature side channel and heating fault attacks. In Proceedings of the Smart Card Research and Advanced Applications: 12th International Conference, CARDIS 2013, Berlin, Germany, November 27-29, 2013. Revised Selected Papers 12. Springer, 2014, pp. 219–235.

- Skorobogatov, S.P.; Anderson, R.J. Optical fault induction attacks. In Proceedings of the Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems-CHES 2002: 4th International Workshop Redwood Shores, CA, USA, August 13–15, 2002 Revised Papers 4. Springer, 2003, pp. 2–12.

- Biham, E.; Shamir, A. Differential fault analysis of secret key cryptosystems. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO’97: 17th Annual International Cryptology Conference Santa Barbara, California, USA August 17–21, 1997 Proceedings 17. Springer, 1997, pp. 513–525.

- Courtois, N.T.; Jackson, K.; Ware, D. Fault-algebraic attacks on inner rounds of DES. In Proceedings of the E-Smart’10 Proceedings: The Future of Digital Security Technologies. Strategies Telecom and Multimedia, 2010.

- Zhang, F.; Lou, X.; Zhao, X.; Bhasin, S.; He, W.; Ding, R.; Qureshi, S.; Ren, K. Persistent fault analysis on block ciphers. IACR Transactions on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems 2018, pp. 150–172.

- Zhang, F.; Feng, T.; Li, Z.; Ren, K.; Zhao, X. Free fault leakages for deep exploitation: algebraic persistent fault analysis on lightweight block ciphers. IACR Transactions on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems 2022, pp. 289–311.

- Fang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, D.; Yan, H.; Fan, F.; Shu, L. Algebraic persistent fault analysis of SKINNY_64 based on s_box decomposition. Entropy 2022, 24, 1508.

- Soos, M.; Nohl, K.; Castelluccia, C. Extending SAT solvers to cryptographic problems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Theory and Applications of Satisfiability Testing. Springer, 2009, pp. 244–257.

- Knudsen, L.R.; Miolane, C.V. Counting equations in algebraic attacks on block ciphers. International Journal of Information Security 2010, 9, 127–135.

- Hu, X.; Xu, S.; Tu, Y.; Feng, X.; Zhang, W. CNF characterization of sets over Z2n and its applications in cryptography. Journal of systems science and complexity 2024, pp. 1–18.

- Daemen, J.; Rijmen, V. The design of Rijndael; Vol. 2, Springer, 2002.

- Banik, S.; Bogdanov, A.; Regazzoni, F. Atomic-AES: A compact implementation of the AES encryption/decryption core. In Proceedings of the Progress in Cryptology–INDOCRYPT 2016: 17th International Conference on Cryptology in India, Kolkata, India, December 11-14, 2016, Proceedings 17. Springer, 2016, pp. 173–190.

- Moradi, A.; Poschmann, A.; Ling, S.; Paar, C.; Wang, H. Pushing the limits: A very compact and a threshold implementation of AES. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology–EUROCRYPT 2011: 30th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Tallinn, Estonia, May 15-19, 2011. Proceedings 30. Springer, 2011, pp. 69–88.

- Hanley, N.; ONeill, M. Hardware comparison of the ISO/IEC 29192-2 block ciphers. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE computer society annual symposium on VLSI. IEEE, 2012, pp. 57–62.

- Tay, J.; Wong, M.D.; Wong, M.; Zhang, C.; Hijazin, I. Compact FPGA implementation of PRESENT with boolean s-box. In Proceedings of the 2015 6th Asia Symposium on Quality Electronic Design (ASQED). IEEE, 2015, pp. 144–148.

- Rolfes, C.; Poschmann, A.; Leander, G.; Paar, C. Ultra-lightweight implementations for smart devices–security for 1000 gate equivalents. In Proceedings of the Smart Card Research and Advanced Applications: 8th IFIP WG 8.8/11.2 International Conference, CARDIS 2008, London, UK, September 8-11, 2008. Proceedings 8. Springer, 2008, pp. 89–103.

- Quine, W.V. The problem of simplifying truth functions. The American mathematical monthly 1952, 59, 521–531.

- Brayton, R.K.; Hachtel, G.D.; McMullen, C.; Sangiovanni-Vincentelli, A. Logic minimization algorithms for VLSI synthesis; Vol. 2, Springer Science & Business Media, 1984.

- Zelewski, S. Komplexitätstheorie: als instrument zur klassifizierung und beurteilung von problemen des operations research; Springer-Verlag, 2013.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).