1. Introduction

The first known evidence for the existence of dark matter dates back to Zwicky’s 1933 investigation of Coma Cluster. It involves identifying non-luminous matter dark matter by analyzing the motion of celestial bodies in gravitational orbits. It is estimated that around 27% of the universe consists of dark matter, with the remainder composed of dark energy and baryonic matter [1]. Dark matter particles have existed since the very beginning of the universe.

According to the early universe theory, the WIMPs formation occurred during the thermal bath. Dark matter annihilation dominates after the thermal freeze-out phase, during which dark matter particle formation and annihilation were in equilibrium. They fragmented into many chains of particles consistent with the traditional model [2].

The rotational velocity of objects at a distance far from the galactic center is almost equal to that of those close to the galaxy nucleus, according to the flat rotational curve of the galaxy [3].

Considering a star orbiting at a distance "r" from the galactic centre which is in mechanical equilibrium. By balancing the forces, we come to know that the velocity (

) is inversely proportional to the square root of the radius (r).

For example, the flat rotation curve of NGC 6503 galaxy is given below.

Figure 1 indicates the relation between the radius (r) and the rotational velocity () of the stars and the gas from the galactic center. According to the Keplerian rotation, the velocity measurements should decline as the distance increases but the observed data doesn’t match with the theoretical prediction. Instead, the rotational velocity is found to be almost constant with the distance indicating the presence of additional non-luminous mass responsible for the additional velocity for the distant objects. And hence maintaining the galaxy structure, rather than falling at a farther distance.

Figure 1.

Galactic rotation curve for NGC 6503 showing disk and gas contribution plus the dark matter halo contribution needed to match the observational data [4].

Figure 1.

Galactic rotation curve for NGC 6503 showing disk and gas contribution plus the dark matter halo contribution needed to match the observational data [4].

Evidence for dark matter also comes from gravitatonal lensing. It occurs when massive objects such as galaxy clusters bend the light from background object due to their gravitatonal field. This allows to infer the presence of unseen mass which cannot be visible matter alone. In particular the bending of light in ways that exceed what would be expected from visible matter suggest the presence of dark matter which adds on to the gravitatonal field but doesn’t emit or interact with electromagnetic radiation [3].

From the data of various CMB measurements like WMAP and Planck data it is found that the total density of the universe contributed by various sources like Baryon matter, Dark energy and curvature energy should be equal to 1. Out of this contribution, the dark energy is almost 0.673 and the contributions from baryon mass is about 0.1. Curvature density contributions are almost negligible. However stil we need to account for the remaining mass. This is where the DM provides solution to this problem as it can account for the remaining density [5,6].

The baryon density is ∼ 0.1 which is too little, according to big-bang nucleosynthesis, in order to explain the dark matter in the Universe. The known structure is not well reproduced by N-body simulations of structure development in a neutrino-dominated Universe, despite the possibility that a neutrino species of mass O (30 eV) may supply the appropriate dark-matter density [5]. Moreover, it is hard to see how such a neutrino might comprise the dark matter in galaxy halos (basically from the Pauli principle). Therefore, it would seem likely that some non baryonic, non-relativistic substance is needed.

2. Dark matter, its nature and influence in shaping the cosmos

2.1. Technologies for the dark matter detection

Different kinds of detectors use different techniques,involving signals such as phonons for solid targets,photons for liquid targets and charge signals for semiconductors. [7]. The various types of detectors includes the Scintillator (solid or liquid) such as the DAMA experiment at the LNGS underground laboratory uses very low-radioactive NaI(Tl) crystals to seek for dark matter, the Germanium detectors such as CoGeNT experiment involves p-type point contact germanium for WIMPs search, the Cryogenic bolometers use the charge or scintillation signal in addition to the phonon signal to give particle discrimination, for example CDMS II experiment uses germanium and silicon bolometers to search for DM, the Liquid noble-gas detectors such as XENON, LUX and PandaX use liquid argon (LAr) and liquid xenon (LXe) to reach high scintillation and ionisation yields and further detectors such Superheated fluids, Directional detectors and Novel detectors are also in search for the DM signature. For more details regarding the technologies involved in DM experiments, refer [7].

2.2. Possible candidates

Some possible dark matter candidates include Majorona particles, Goldstone boson, pyrons, maximos which can be ruled out due to non astrophysical consideration. Other candidates, such as brown dwarf, old white dwarfs, neutron stars contribute too little to the dark matter content. [1]. The major candidates of dark matter include WIMPs (Weakly Interacting Massive Particles) and Axions. WIMPs being preferred over Axions due to various reasons such as they arise naturally in a large number of theoretical models and for reasonable ranges of WIMP mass and annihilation cross section, the relic abundance of dark matter can be obtained through the robust mechanism of thermal freeze-out, possibly augmented with some other production mechanisms. Thermal WIMPs represent a promising target for DM experiments as a large fraction of their typical detection rates are within reach of current or planned detectors, making them testable by experiment.

WIMPs (Weakly Interacting Massive Particles) are considered to be long lived or stable particles that are left from the Big Bang which interacts weakly or sub weakly and have a mass range of around 2 GeV to 100 TeV. It can be found directly in low-background laboratory detectors if they are present in the halo, or indirectly by observing energetic neutrinos from WIMPs that have accumulated and then annihilated in the Sun and/or Earth. It has a greater interaction cross section than axions, axinos, gravitinos, and sterile neutrinos, making them an appealing experimental target [8].

2.3. Detection of WIMPs

Since dark matter particles primarily interact gravitationally and only weakly via other forces, detecting them is highly challenging. This is especially true if there is any background noise, such as electron recoil events, or if the atoms chosen as target substances to interact with DM particles disintegrate. A particle that constitutes all of dark matter is predicted to have mass in the range ∼ 100 GeV to 1 TeV. Therefore a particle that makes up 10% of dark matter has mass ∼ 30 GeV to 300 GeV, which refers to WIMP miracle which leads to the conclusion that weak-scale particles are great candidates for dark matter. The WIMP miracle provide a model-independent reason for dark matter at the weak scale and has a significant implications for how dark matter might be detected.

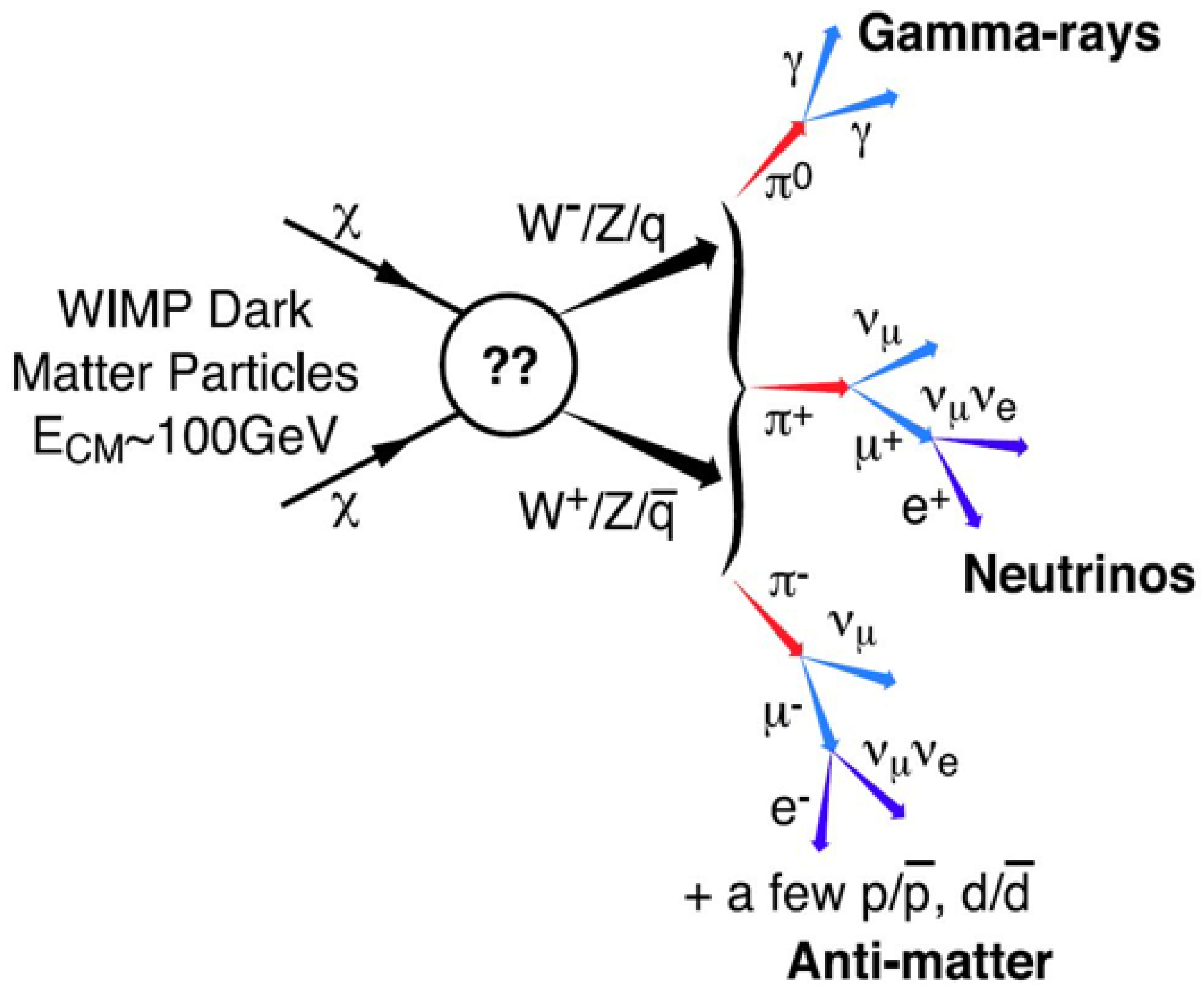

In the

Figure 2, the "X" in the accompanying graphic represents the annihilation of WIMPs. It provides an illustrative idea of this process. The various models of WIMPs’ self-interactions suggest that they may interact through a physical force field that is currently unknown. They may also annihilate one another to produce standard model particles like pions, which then decay into neutrinos and gamma rays as byproducts. The bosons in the

Figure 2, are W and Z.

Figure 2.

Illustration of Annihilation of WIMPs [9]

Figure 2.

Illustration of Annihilation of WIMPs [9]

WIMPs (X) must annihilate to other particles in order to have the observed remnant density. Assuming that these extra particles are Standard model(Y) particles which yields the consequences for the detection, and the requirement of XX→ YY interactions results in three feasible approaches for dark matter detection. Below is a list of them.

Particle colliders: When particles collide, the total energy and momentum are conserved. If dark matter particles are produced, they escape detection, leading to an imbalance in the observed energy and momentum. This "missing energy" is a key indicator. Dark matter can be created at particle colliders using YY → XX. Such events are undetected, although they are frequently accompanied by associated production mechanisms, such as YY → XX + (Y), where ‘(Y)’ signifies one or more standard model particles. These events are visible and provide dark matter signatures at colliders.

Indirect detection: This process considers the mechanism which involves the annihilation of DM particles with a baryonic particle as well as self-annihilation. When they annihilate each-other they tend to produce particles like neutrinos as well as gamma rays, along with other kinds of standard model particles. If an excess of this kind of particles are found then backtracking them can give the location of DM halo. If dark matter annihilated in the early Universe, it must likewise annihilate now via XX → YY, and the annihilation products may be found [10].

Direct detection: Dark matter can scatter off normal matter via XY → XY interactions, depositing energy that can be detected with sensitive, low background detectors. This approach is the most preferred among all others. The underlying premise behind this is to allow the DM flux from the galactic halo to scatter with the nucleus of the target substance, which is typically Xenon atoms. The main reasons for selecting Xenon are that it can be purified to a high degree, its internal radioactivity is low, and its mass matches that of WIMPs, a proposed candidate for DM. Additionally, using Xenon as a target material has the advantage of significantly reducing background noise. When WIMPs are scattered from the target nuclei, the theoretical limits of events of this detection can be set, as well as the detector’s threshold limit, to obtain the values of the scattering cross section and mass, which is very useful for further studies.

2.4. Interaction cross section of WIMPs

Galaxies consist of stars, dust, dark matter, and gas. Surveys like GAIA and CHANDRA allow us to calculate the distribution and density of stars, dust, and gas. By applying Laplace equations and knowing the total gravitational potential energy of a galaxy, we can determine the total density of all its components [?]. This numerical analysis has determined the local dark matter density of the Milky Way to be approximately 0.3 to 0.6 GeV/. The dynamics of star motion within the Milky Way galaxy confirm this value range, demonstrating that dark matter density is independent of radial profile.

Considering the local DM density at our position in the galaxy to be

∼ 0.3 GeV/

with mass

= 100 GeV, the number density(n) is given by,

where, n ≈ 3 ×

therefore WIMP velocity, v≈ 300 and the WIMP flux will be J = n v≈

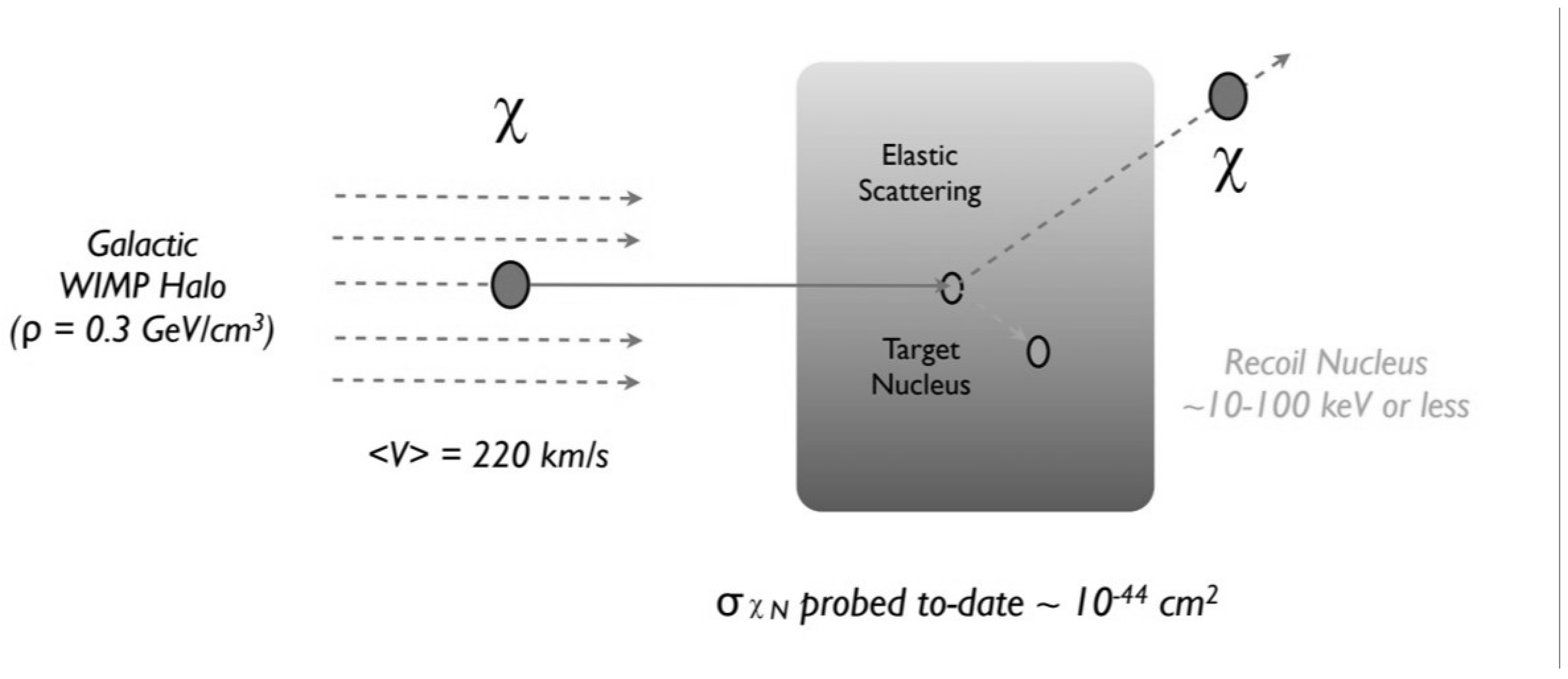

A pictorial representation of the above mechanism involving scattering is shown below,

Figure 3.

Coherent scattering of WIMPs off nuclei [11]

Figure 3.

Coherent scattering of WIMPs off nuclei [11]

The fundamental expression for the differential event rate in elastic WIMP-nucleus scattering is as follows:

where,

R - direct detection event rate

Q - energy deposited in the detector

- WIMP density near the Earth

- total cross section ignoring the form factor suppression

F(Q) - elastic nuclear form factor

f(v) - 3D velocity distribution function of the WIMPs impinging on the detector.

= WIMPs mass

- reduced mass of target nucleus and WIMPs

The Dark Matter Direct Detection experiment called XENON is looking for WIMPs through the use of liquid Xenon as a sensitive detection medium [7]. According to Super Symmetry (SUSY), these particles are thought to be pervasive throughout the universe, have a mass in the range of 100 GeV and disregard electromagnetic interactions.

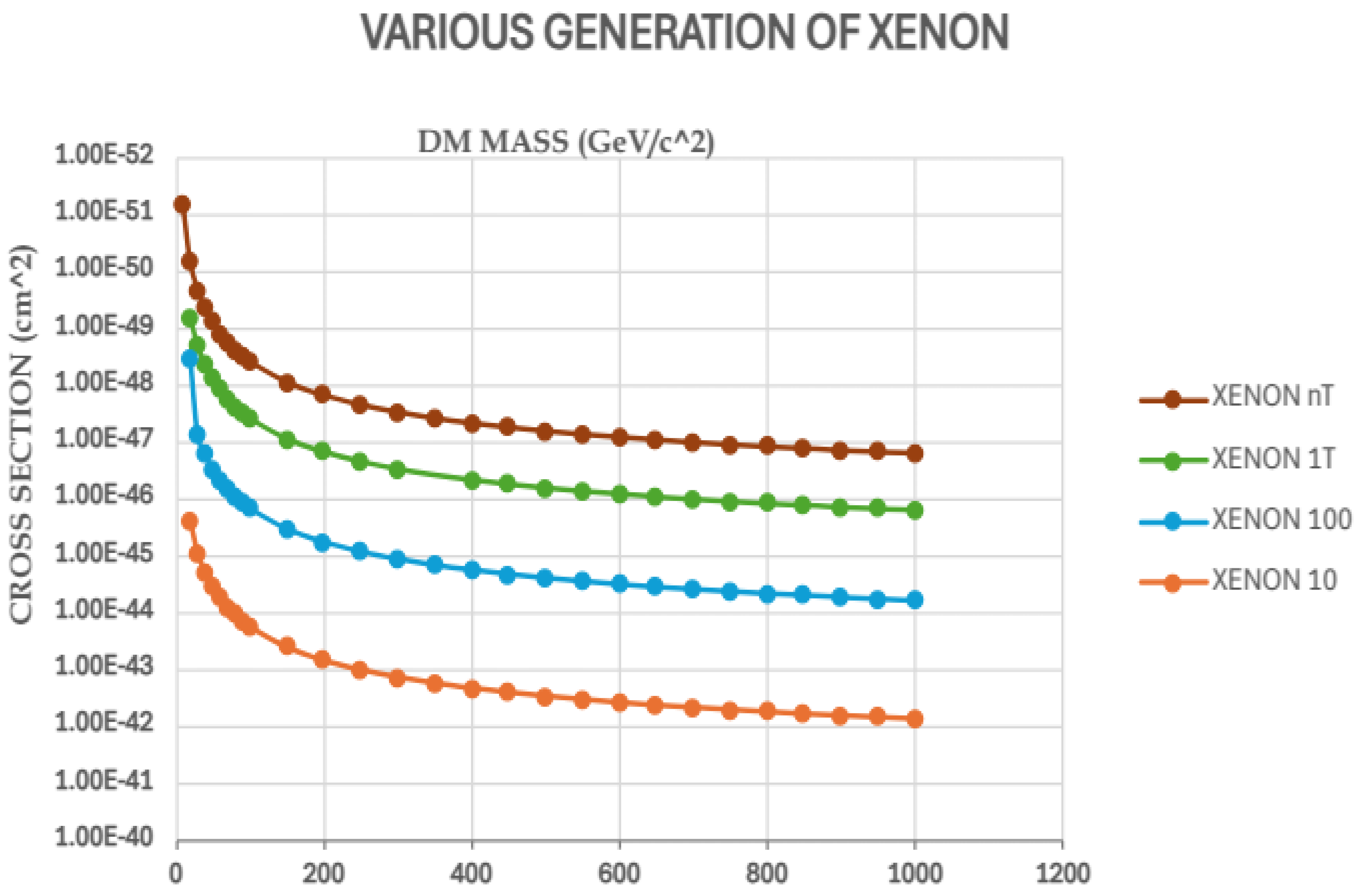

Different generations of XENON experiments are now being conducted in order to obtain signs regarding DM particles. Experiments like XENON 10, XENON 100, XENON 1T, and XENON nT are commonly employed. However, experiments such as PANDAX [12] and LUX [13] are also used to search for potential signals.

The case that involves dark matter interaction with a light mediator undertaken in PANDAX experiment, closely resembles the details in the referenced paper [?]. A key distinction lies in the differential event rate equation. Here, the cross-section differential with respect to recoil energy exhibits velocity independence [?]. Furthermore, the differential event rate depends on the mediator mass and momentum transfer, as evident from the equations below. However, when the mediator mass significantly exceeds the momentum transfer, the resulting relationship mirrors the derived Equation (

4) without considering a light mediator.

where,

= DM-nucleon cross section in the limit of zero momentum transfer, () = 0

And the cross section is proportional to the mediator mass and momentum transfer,

whereas, = mediator mass and = nuclear form factor.

The fundamental distinction between all of the generations of XENON experiments is that they use varying amounts of liquid Xenon, as indicated by their respective designations. For example, XENON 100 uses 100 kilogram of liquid Xenon. The larger the amount of Xenon in the detector, the more background noise can be reduced, as well as the scattering cross-section, which improves the chance of interaction. The relative capacity of different detectors to detect the WIMP mass is determined by both the WIMP and target masses, as well as their energy thresholds.

XENON 10: The Gran Sasso National Laboratory’s XENON 10 experiment used a 15 kilogram Xenon dual phase Time Projection Chamber (XeTPC) to look for WIMPs. In order to distinguish signal from background down to 4.5 keV nuclear recoil energy, the detector simultaneously detects the scintillation and the ionization caused by radiation in pure liquid xenon [14]. A upper limit of 8.8 x for a WIMP mass of 100 GeV/ and lower limit of 4.5 x for a WIMP mass of 30 GeV/ has been set for the WIMP-nucleon spin-independent cross-section. This analysis is based on 58.6 live days of data, collected between October 6, 2006 and February 14, 2007, and utilizes a fiducial mass of 5.4 kg.

XENON 100: The XENON 100 experiment is a follow up of XENON 10 dark matter search project that seeks to reduce background rate by a factor of 100 while increasing the fiducial liquid Xenon target mass to 100 kg in comparison to the XENON 10 experiment. Data were collected over a period of 224.6 days in an ultra low electromagnetic background fiducial cylinder holding 34 kg of liquid Xenon. Unlocking the region of interest resulted in two events, consistent with the background expectation of (1.0 ± 0.2) events. After analyzing these data, the spin independent elastic WIMP-nucleon scattering cross section () has an upper limit of at least 2 x at 55 GeV/ [15].

XENON 1T: The XENON 1T exposes subjects to 1.0 ton × year of radiation using a liquid Xenon time projection chamber with a fiducial mass of (1.30±0.01) T. A profile likelihood analysis parameterized in spatial and time dimensions excludes new parameter space for the WIMP-nucleon spin-independent elastic scatter cross-section for WIMP masses above 6 GeV/, with a minimum of 4.1 × at 30 GeV/.

XENON nT: Utilizing 8.6 tonnes of Xenon in total, XENON nT is the newest member of the XENON family. By replacing the TPC with a new cryostat, the detector system’s core, XENON 1T could be upgraded quickly thanks to the reuse of its infrastructure and subsystems. In 2020, data collection for the XENON nT experiment began. Based on extensive simulations, the sensitivity to spin-independent interactions for a 50 GeV/ WIMP after five years with a 4 tonne fiducial volume is estimated to be 1.4 × [16].

2.5. Density profiles

The density of DM is a crucial parameter in determining the scattering cross section. Therefore, the different dark matter density profiles are taken into account in order to set the limit on mass and cross section of WIMPs. Several heuristic fitting function have been developed which capture the shape of individual DM halos and the shape of luminosity matter distribution including DM. Some of the most preferred profiles are Einasto, NFW, Isothermal and Burket dark matter density profiles.

Einasto profile

Einasto profiles are among the most popular models. Their models incorporate einasto’s power law logarithmic density slope, which is used to predict star distribution. This paradigm is currently referred to as the Einasto model. Only a few Einasto attributes can be computed analytically [17] [?].

where, x =

Here, r = ; = 1.5 (shape parameter); = scale radius

= dark matter density at radius (r) from the centre of the galactic black hole and n = best fit parameter

NFW profile

Navarro Frenk White profile is represented as NFW profile. It was proposed in the year 1996. Fitting the NFW profile to the equilibrium mass density in simulation revealed that it can characterize the mass density profile over two decades with respect to radius, regardless of halo mass [18] [?] . The dark matter density is given by,

where, x = ; r = radius and = scale radius

= density at scale radius

Isothermal profile

The isothermal profile assumes a constant density throughout the halo. In contrast to the cuspy profile, the density distribution selected by observing the rotation curves of low surface brightness and dwarf spiral galaxies has essentially constant dark matter density at the galactic center. Because the density in the central region is constant on the kpc scale, such profiles are known as cored profiles. The dark matter density is given by [19] [?],

The isothermal model is an approximation, and numerous factors can induce variation from this profile, such as mergers related with the creation of a halo, rendering the spherical collapse model insufficient.

Burket profile

Burket (1995) attempted to determine the optimum density law that matched the reported rotational curve of a dwarf galaxy believed to be dominated by dark matter. It is an empirical law that resembles pseudo isothermal halo model [20] [?]. The dark matter density is given by,

where, x =

3. Constraint on mass and cross section of WIMPs

Detecting dark matter signature is one of the greatest challenges in today’s research. Various underground detectors worldwide are searching for traces of dark matter using direct and indirect detection approaches. Here, we have considered the direct detection method focusing on the different generations of XENON detector in order to constraint the mass and cross section of WIMPs.

In the case of direct detection of dark matter, the scattering cross section can be calculated from the event rate (R), it is proportional to the number of nuclei in the target and the WIMP nucleus scattering cross section and is given by,

Where,

= number of nuclei in the target

= WIMP nucleus scattering cross section

= Dark matter density

= Average WIMP velocity in lab frame,

Event rate(R) in a potential detector is determined by integrating overall recoils,

By considering the nature of cold dark matter, the scattering takes place at non relativistic speed.

The velocity distribution function of dark matter particles is given by [21],

Where,

= dispersed velocity of WIMPs (∼ 260

)

Where,

= escape velocity of WIMPs (∼ 580 )

= solid angle (4)

= reduced mass of target nucleus and WIMPs

4. Results and discussion

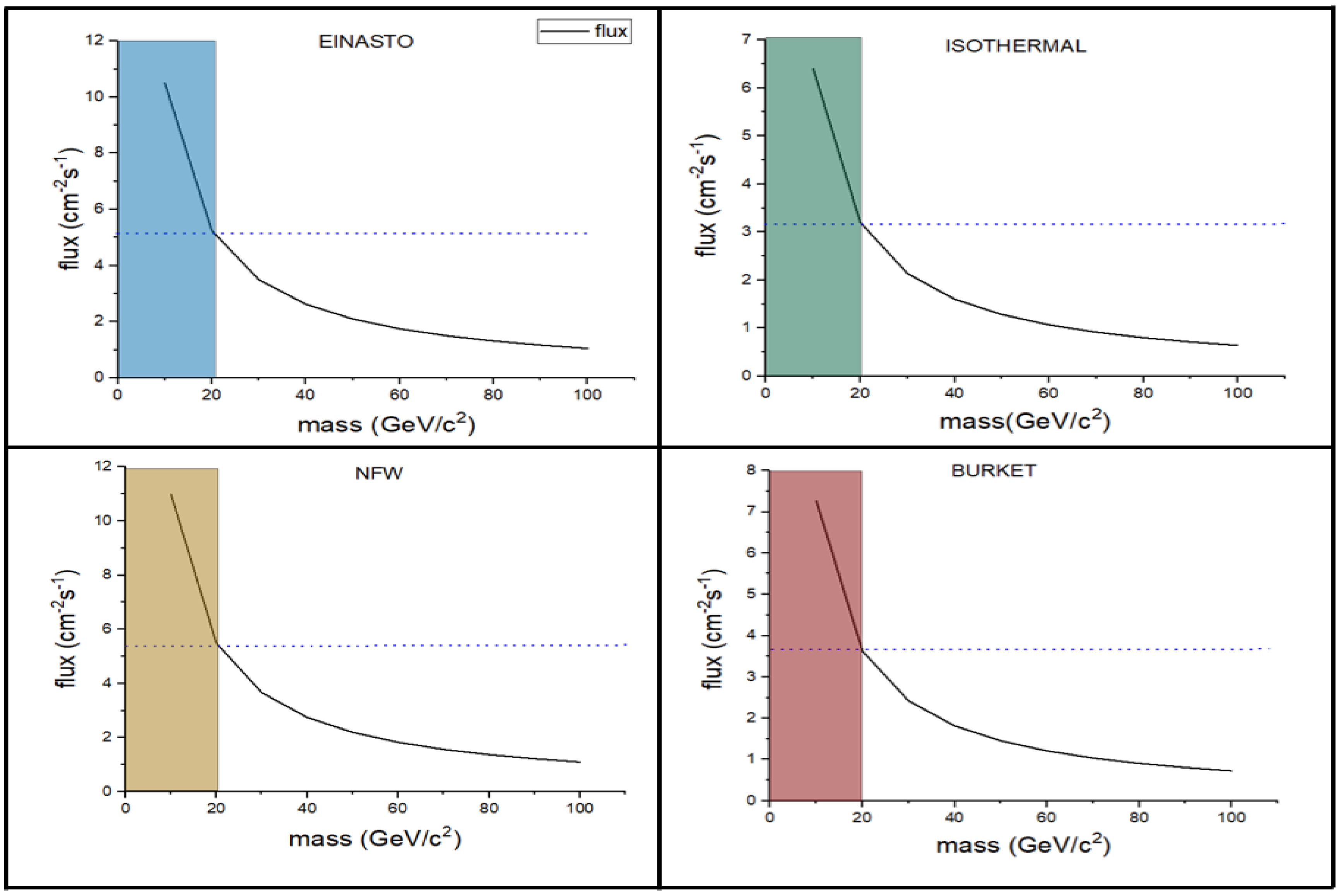

To constraint, mass vs cross section graph was plotted for different XENON generations. Since the cross section() is dependent on the dark matter density(), various dark matter density profiles were studied and the corresponding density values has been obtained. By plotting flux against WIMPs mass, we determine the lower mass limit for WIMPs. We then constrained the cross-section and further refined WIMP mass limit by examining different XENON generations.

From the graphs plotted for the different generation of XENON detectors using a dark matter density of around 0.36 GeV/, it can be seen that for the different generations of XENON experiments the cut off mass of WIMPs is around 40 GeV/ and cross section limits of WIMPs at corresponding cut offs are as 1.63 × , 1.4 × , 0.4 × and 0.37 × respectively.

Figure 4.

Mass (GeV/) vs Cross section () plots for different XENON generations. The lower limit for mass of WIMPs can be obtained from these plots.

Figure 4.

Mass (GeV/) vs Cross section () plots for different XENON generations. The lower limit for mass of WIMPs can be obtained from these plots.

Figure 5.

Mass (GeV/) vs Flux ( ) using different dark matter density profiles. Top left: Einasto profile(blue). Top right: Isothermal profile(green). Bottom left: NFW profile(dark yellow). Bottom right: Burket profile(red).

Figure 5.

Mass (GeV/) vs Flux ( ) using different dark matter density profiles. Top left: Einasto profile(blue). Top right: Isothermal profile(green). Bottom left: NFW profile(dark yellow). Bottom right: Burket profile(red).

From

Figure 3, the plots of flux of dark matter particle with the mass of WIMPs for different profiles provides the evident for the cut off limits of mass for WIMPs to be around 40 GeV/

, as below this the mass of WIMPs are significantly low to give sufficient recoil energy.

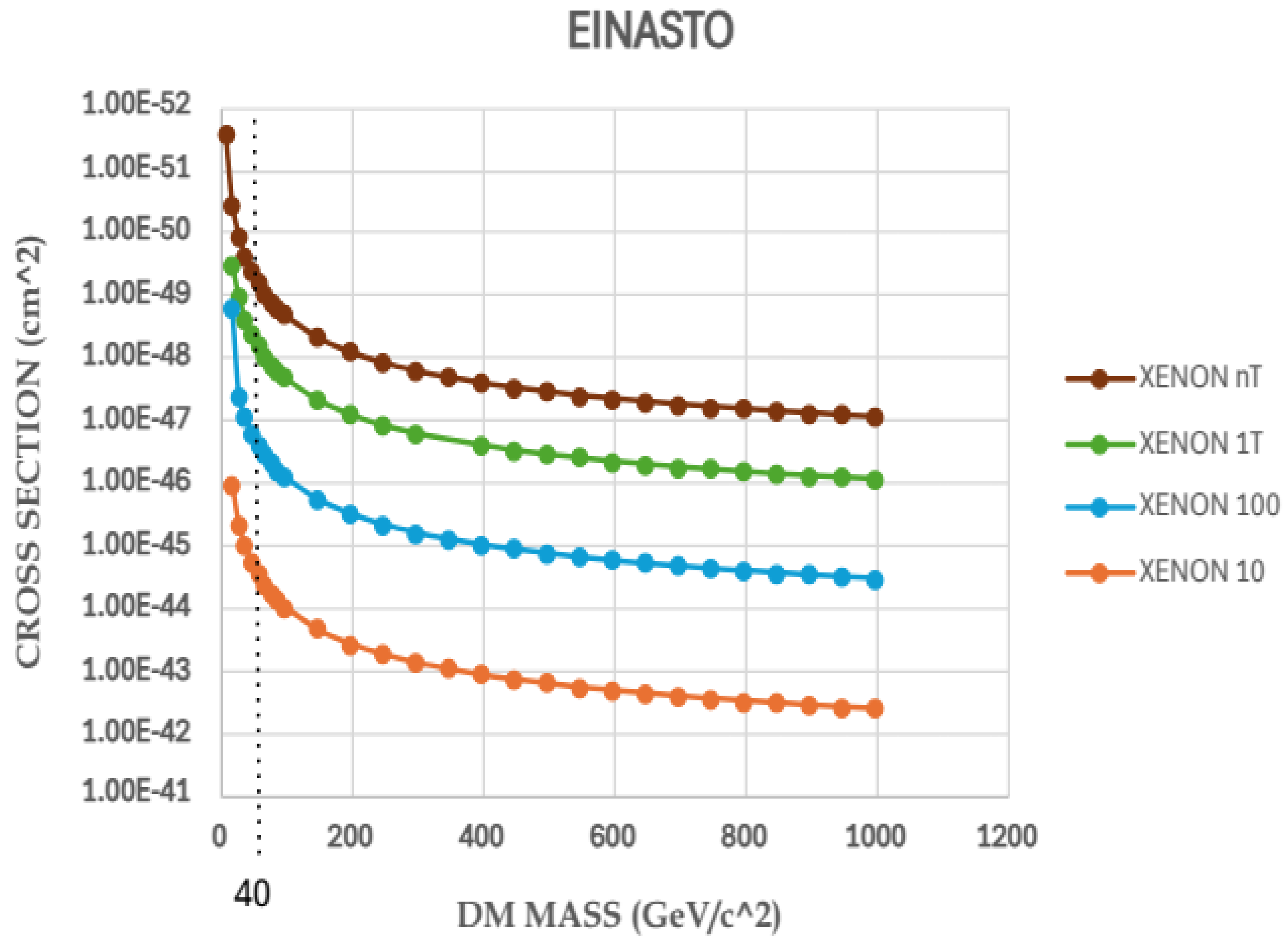

Figure 6.

Mass (GeV/) vs Cross section () for different XENON generations with the dark matter density value obtained from Einasto profile

Figure 6.

Mass (GeV/) vs Cross section () for different XENON generations with the dark matter density value obtained from Einasto profile

Using the obtained density value 0.3226 GeV/ from Einasto profile, it is found that cut off limit for WIMPs mass is around 40 GeV/.

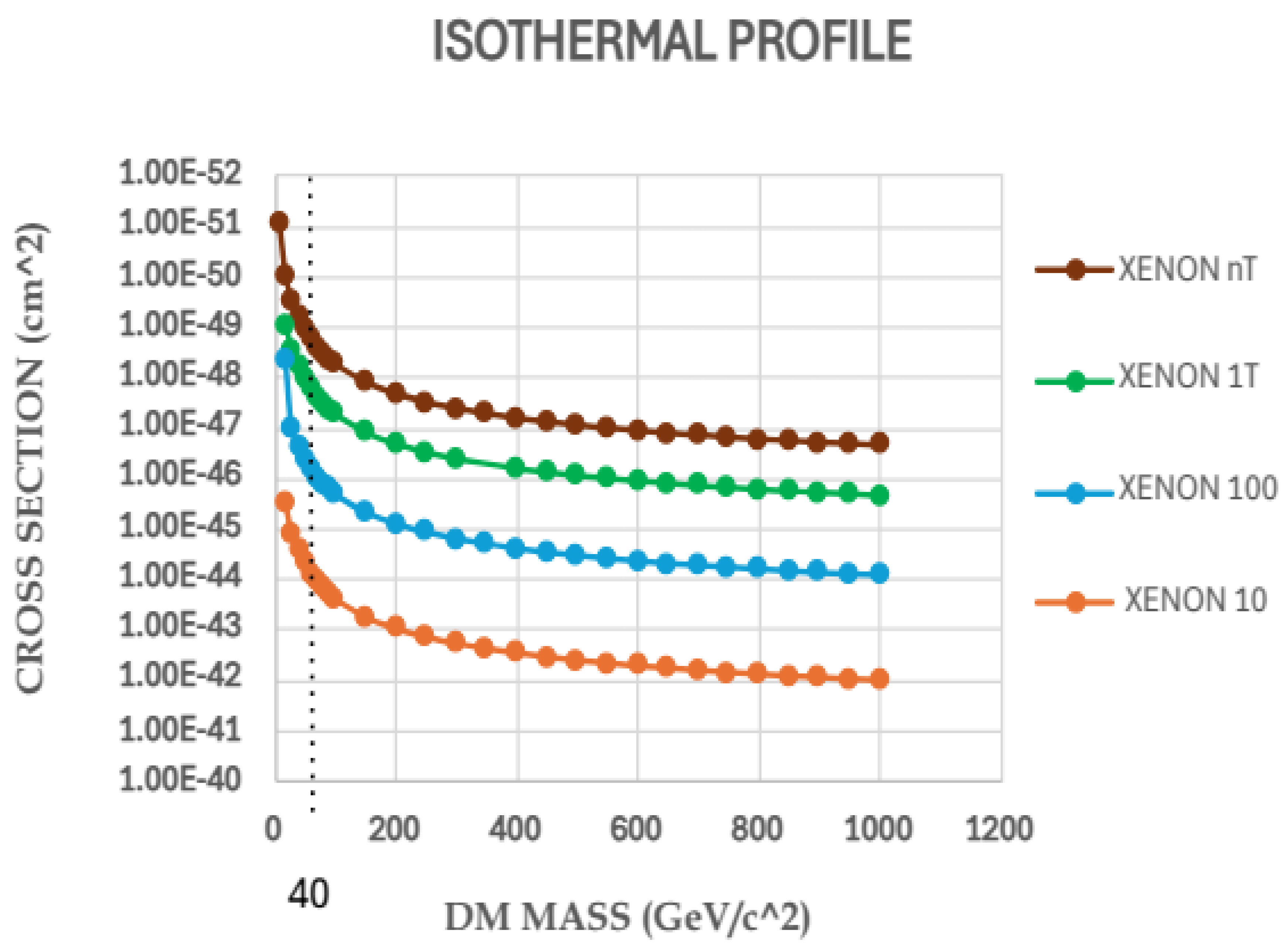

Figure 7.

Mass (GeV/) vs Cross section () for different XENON generations with the dark matter density value obtained from Isothermal profile

Figure 7.

Mass (GeV/) vs Cross section () for different XENON generations with the dark matter density value obtained from Isothermal profile

Similarly, using the density value from Isothermal profile, 0.2759 (GeV/), it is found that cut off limit for WIMPs mass is around 40 (GeV/).

Figure 8.

Mass (GeV/) vs Cross section () for different XENON generations with the dark matter density value obtained from NFW profile

Figure 8.

Mass (GeV/) vs Cross section () for different XENON generations with the dark matter density value obtained from NFW profile

Likewise, for the density value from NFW profile, 0.20 (GeV/), it is found that cut off limit for WIMPs mass is around 40 (GeV/).

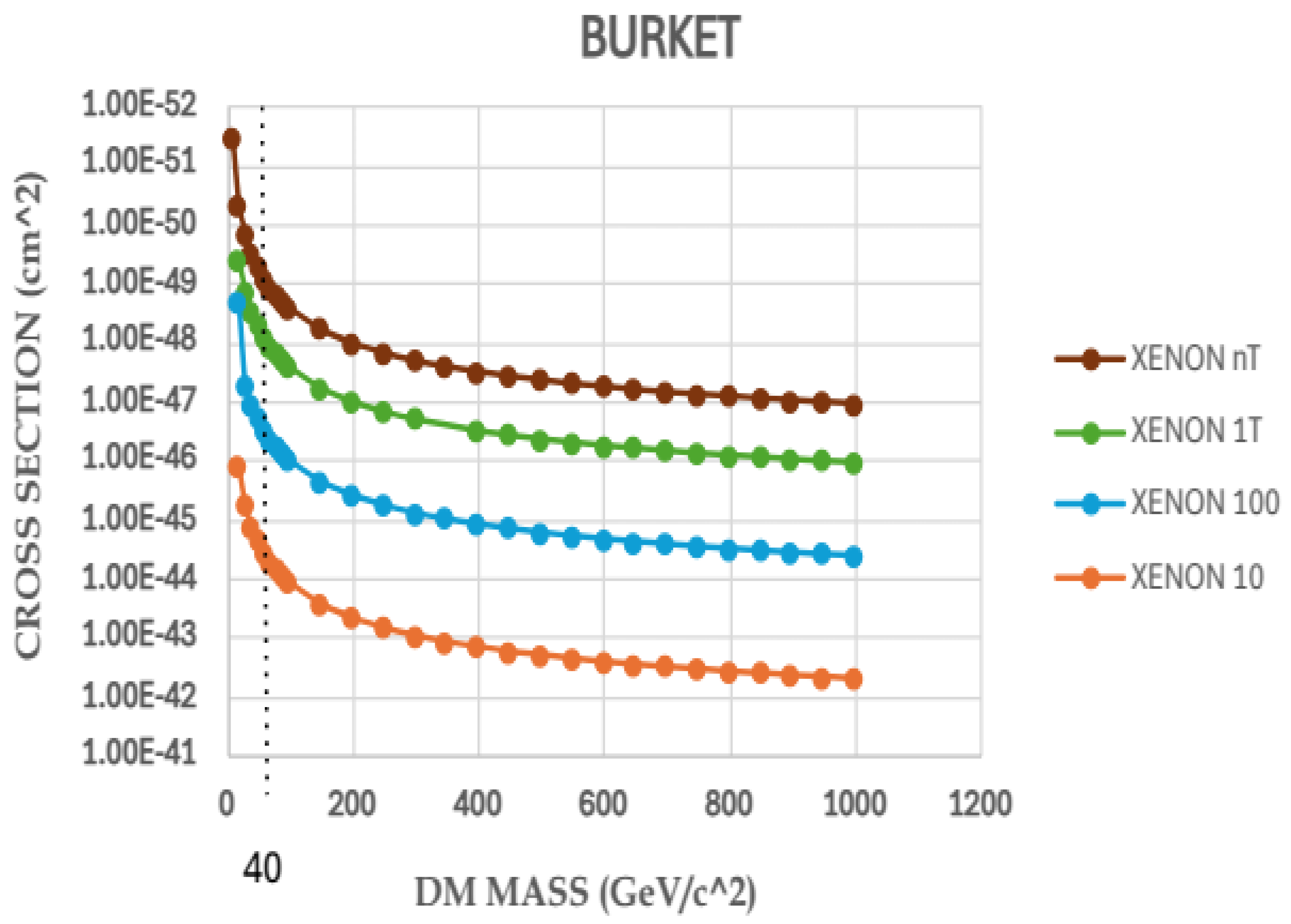

Figure 9.

Mass (GeV/) vs Cross section () plots for different XENON generations with the dark matter density value obtained from Burket profile

Figure 9.

Mass (GeV/) vs Cross section () plots for different XENON generations with the dark matter density value obtained from Burket profile

With the density value 0.23 (GeV/) obtained from the Burket profile, it is found that cut off limit for WIMPs mass is around 40 (GeV/).

The cross section obtained using different density values ranges from ( to ) respectively.

The NFW profile fits the Milky Way galaxy the best, according to recent studies. To have a better understanding of this, we have attempted to use all of these density profiles.At a solar radius scale of approximately 8 kpc, the density of all dark matter density profiles is nearly identical. The primary factor that differentiates these profiles is whether the dark matter distribution is cored (flattened slope) or cuspy (high slope) towards the galactic center. Despite the variation in slopes, the distribution of the various density profiles is similar at the solar radius, from which it is believed that most dark matter particles would approach the detector. Although the cut-off limits are the same, the cross-section values differ for different WIMP masses in different density profiles which can be seen as a slight variation in the above graphs for cross section and mass relation.

5. Conclusions

Several candidates have been proposed for dark matter like WIMPs, Axions, and some exotic candidates like Neutralino, Primordial black holes, Fermi balls however they have been ruled out except for WIMPs and Axions since they didn’t support the N body simulations. Among them WIMPs (cold dark matter) is the most favourable as it supports the theory for the early large scale structure formation [22]. Since they interact very weakly it becomes difficult to trace their signatures. Direct detection experiments uses elements like Xenon since it has a very low background activity, highly purified and the mass of Xenon matches the WIMPs mass range. This work primarily focuses on the different generations of XENON for setting the cut off limits of cross section and mass in the range (10 - 1000) GeV/. The results indicate that WIMPs with a mass below 40 GeV/ can be ruled out for detection as they are not tightly constraint and the cross section limits ranges from ( - ) depending on the generation of XENON detector. Similar calculations has been done using different dark matter density values obtained from studying the various density profiles. The plot between flux and mass of WIMPs for different DM density profiles also supports the cut off limit for mass to be around 40 GeV/.

It is also seen that for XENON 10, XENON 100 and XENON1T for mass around 10 GeV/ detectors arent able to detect but for XENONnT this WIMP mass can be detected however its not strongly constraint as the detector is not highly sensitive in that mass region.

References

- Arun, K.; Gudennavar, S.; Sivaram, C. Dark matter, dark energy, and alternate models: A review. Advances in Space Research 2017, 60, 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, N.; Xu, Y. WIMPs during reheating. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2022, 2022, 017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freese, K. Review of Observational Evidence for Dark Matter in the Universe and in upcoming searches for Dark Stars. EAS Publications Series 2009, 36, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pécontal, E.; Buchert, T.; Di Stefano, P.; Copin, Y.; Freese, K. Review of Observational Evidence for Dark Matter in the Universe and in upcoming searches for Dark Stars. European Astronomical Society Publications Series 2009, 36, 113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Aghanim, N.; Akrami, Y.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Ballardini, M.; Banday, A.J.; Barreiro, R.B.; Bartolo, N.; Basak, S.; et al. Planck2018 results: VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinshaw, G.; Larson, D.; Komatsu, E.; Spergel, D.N.; Bennett, C.L.; Dunkley, J.; Nolta, M.R.; Halpern, M.; Hill, R.S.; Odegard, N.; et al. NINE-YEAR WILKINSON MICROWAVE ANISOTROPY PROBE ( WMAP ) OBSERVATIONS: COSMOLOGICAL PARAMETER RESULTS. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2013, 208, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Undagoitia, T.M.; Rauch, L. Dark matter direct-detection experiments. Journal of Physics G: Nuclear and Particle Physics 2015, 43, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowski, L.; Sessolo, E.M.; Trojanowski, S. WIMP dark matter candidates and searches—current status and future prospects. Reports on Progress in Physics 2018, 81, 066201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morselli, A.; Cañadas, B.; Vitale, V. The indirect search for Dark Matter from the centre of the Galaxy with the Fermi LAT. Il Nuovo Cimento C 2011, 34, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leane, R.K. Indirect detection of dark matter in the galaxy. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.00513 2020.

- Goodman, M.W.; Witten, E. Detectability of certain dark-matter candidates. Physical Review D 1985, 31, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Xie, P.; Abdukerim, A.; Chen, W.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Cui, X.; Fan, Y.; Fang, D.; Fu, C.; et al. Search for light dark matter–electron scattering in the PandaX-II Experiment. Physical Review Letters 2021, 126, 211803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, C.F.P. Dark matter searches with LUX. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.03572 2017. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.03572.

- Chepel, V.; Araújo, H. Liquid noble gas detectors for low energy particle physics. Journal of Instrumentation 2013, 8, R04001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprile, E.; Aalbers, J.; Agostini, F.; Alfonsi, M.; Amaro, F.; Anthony, M.; Arneodo, F.; Barrow, P.; Baudis, L.; Bauermeister, B.; et al. XENON100 dark matter results from a combination of 477 live days. Physical Review D 2016, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration, X.; Aprile, E.; Aalbers, J.; Abe, K.; Maouloud, S.A.; Althueser, L.; Andrieu, B.; Angelino, E.; Angevaare, J.R.; Antochi, V.C.; et al. The XENONnT Dark Matter Experiment, 2024, [arXiv:physics.ins-det/2402.10446].

- Lin, H.N.; Li, X. The dark matter profiles in the Milky Way. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2019, 487, 5679–5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, X.; Eilers, A.C.; Necib, L.; Frebel, A. The dark matter profile of the Milky Way inferred from its circular velocity curve. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2024, 528, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebecca, L.; Arun, K.; Sivaram, C. Dark matter density distributions and dark energy constraints on structure formation including MOND. Indian Journal of Physics 2020, 94, 1491–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salucci, P. The distribution of dark matter in galaxies. The Astronomy and Astrophysics Review 2019, 27, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, J. Dark Matter direct detection of classical WIMPs. SciPost Physics Lecture Notes 2022, p. 055.

- Bertone, G. The moment of truth for WIMP dark matter. Nature 2010, 468, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).