Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

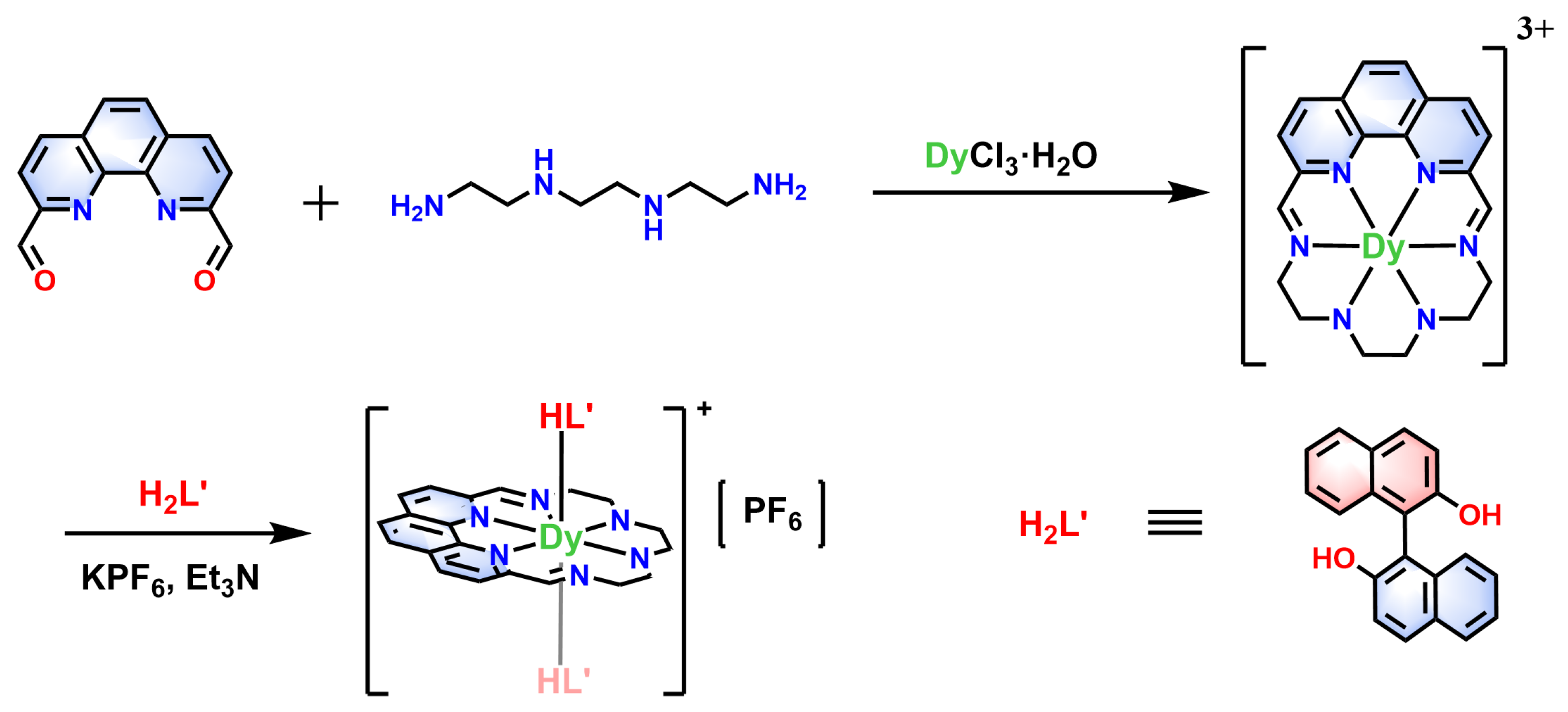

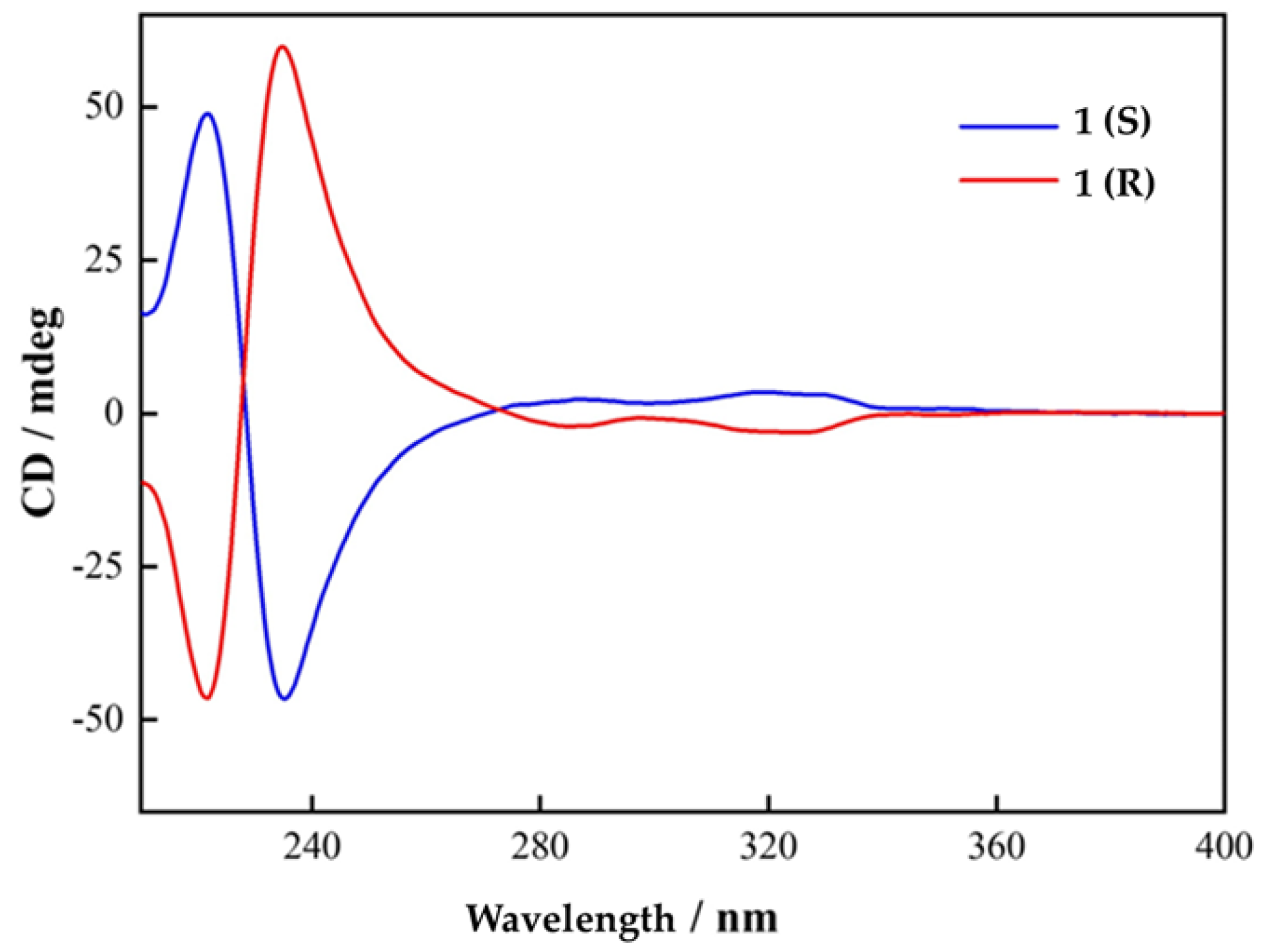

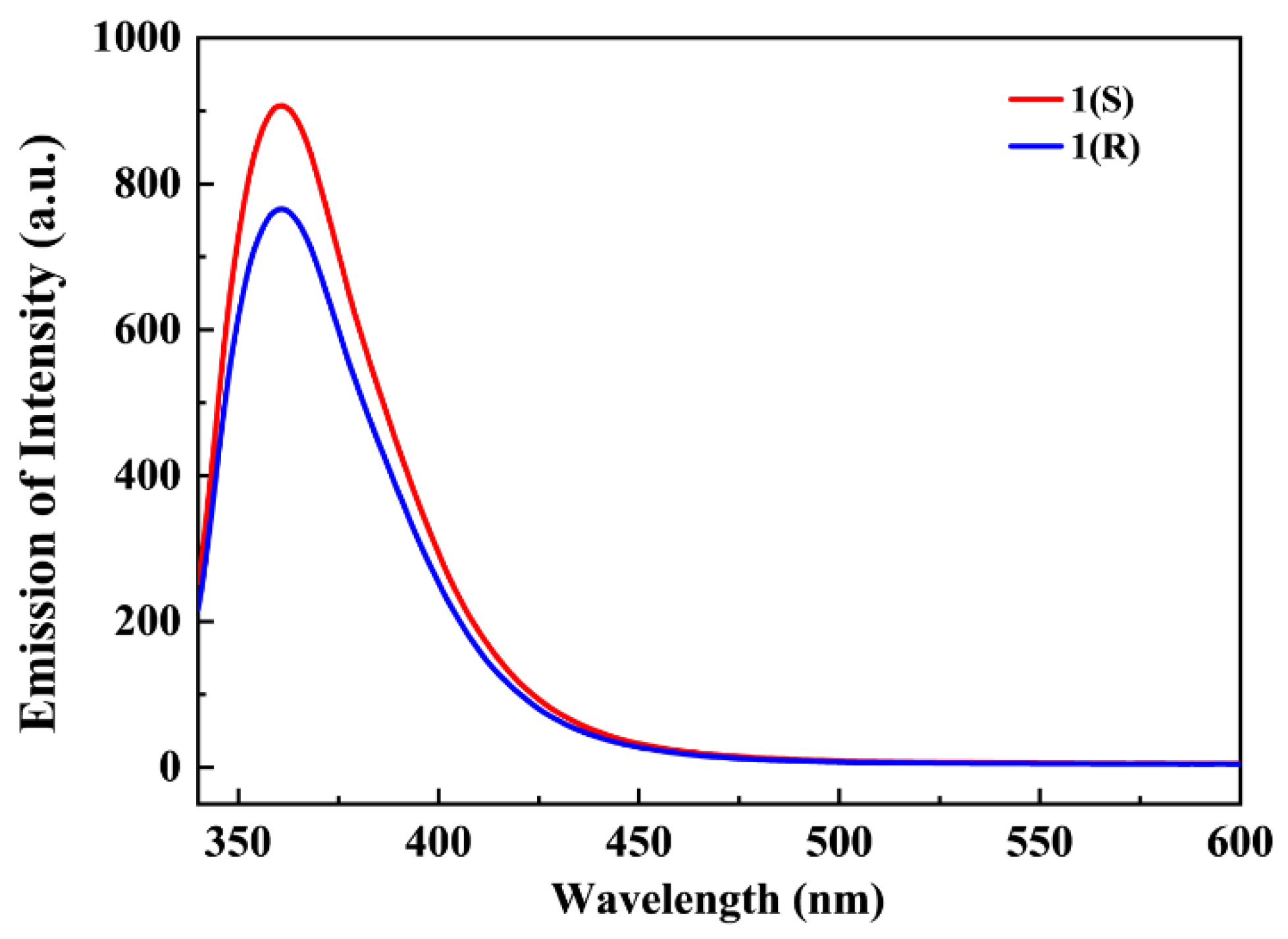

2.1. Synthesis and Characterizations

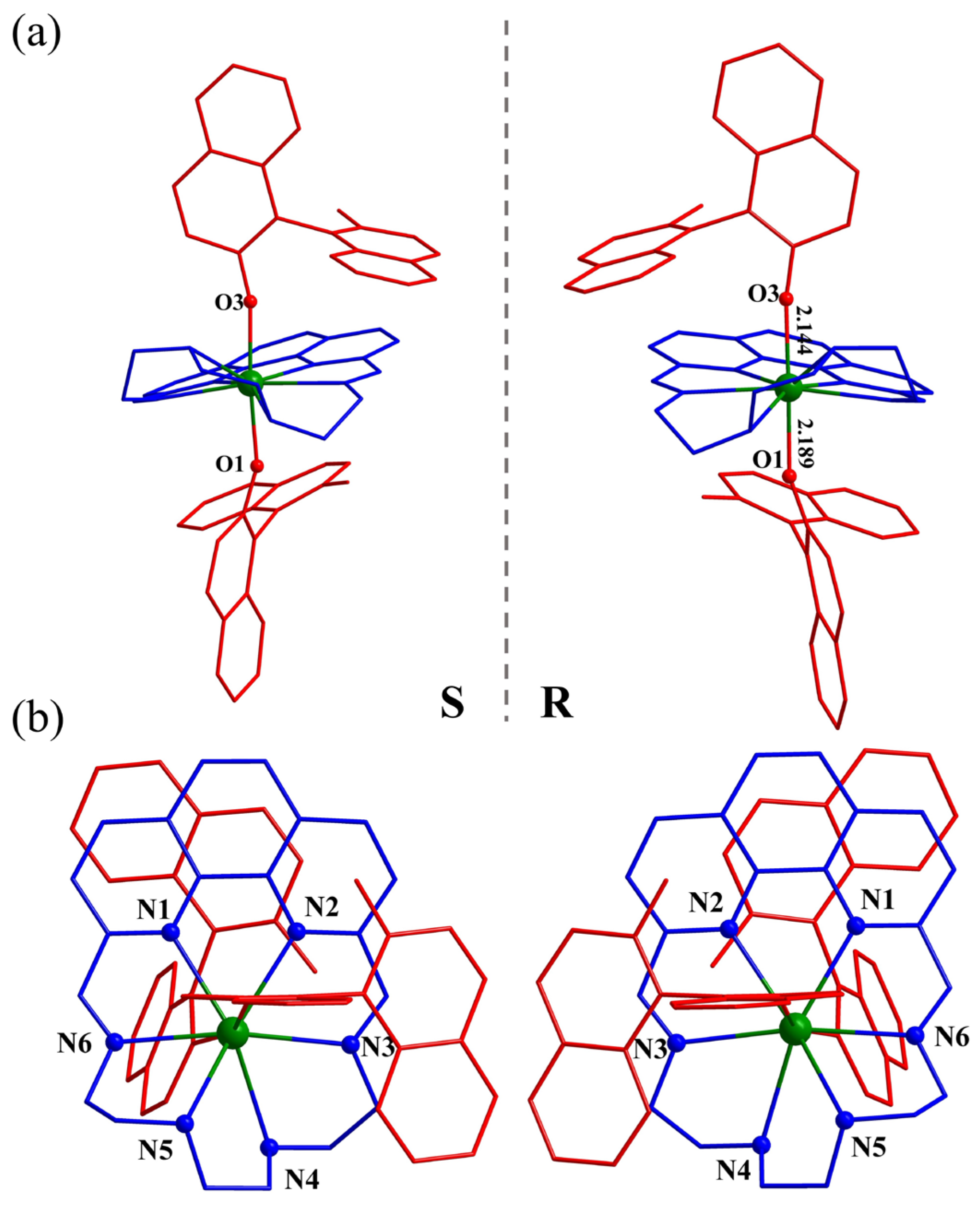

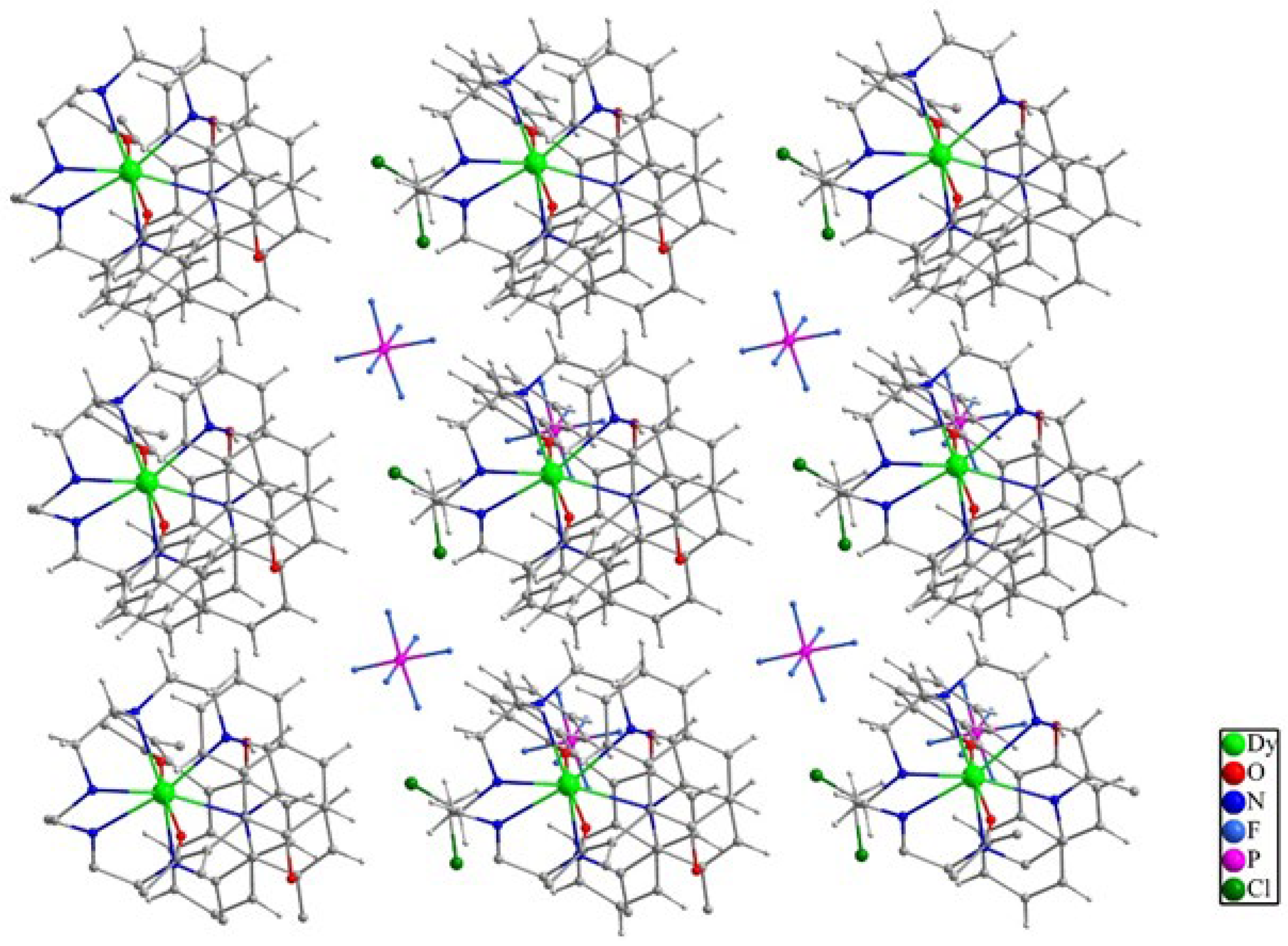

2.2. Structure

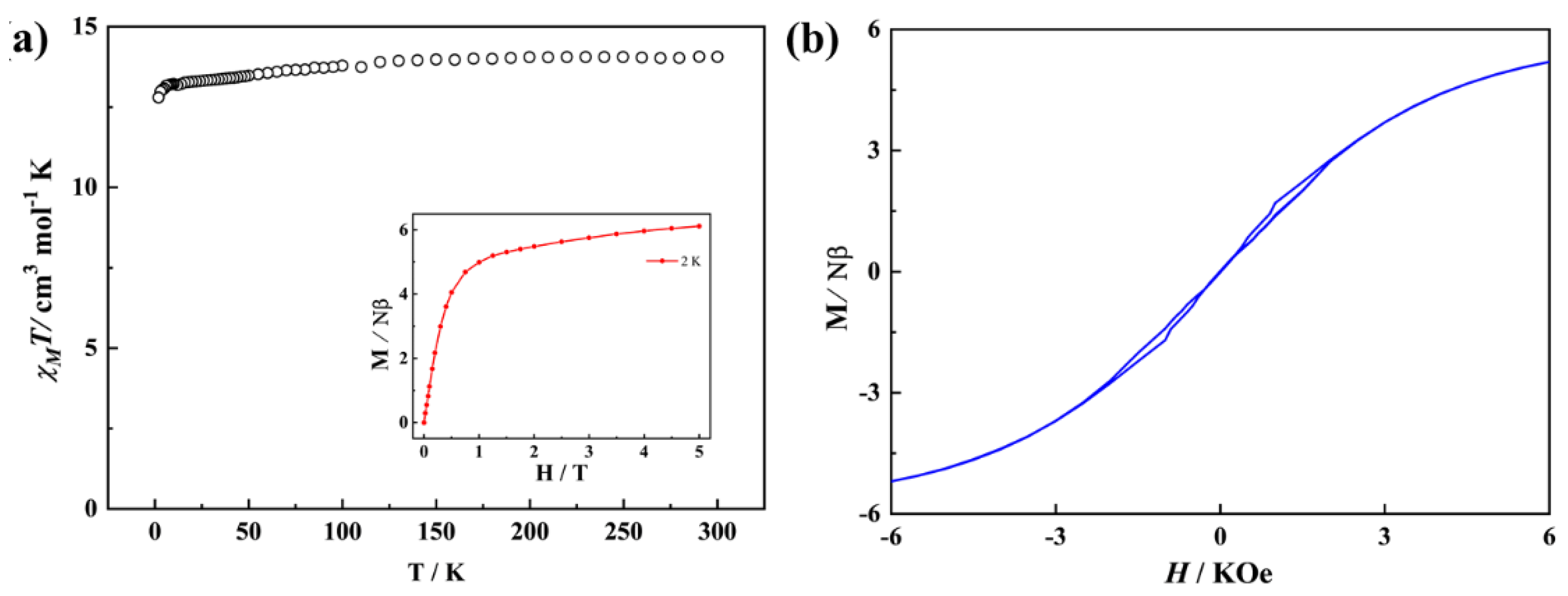

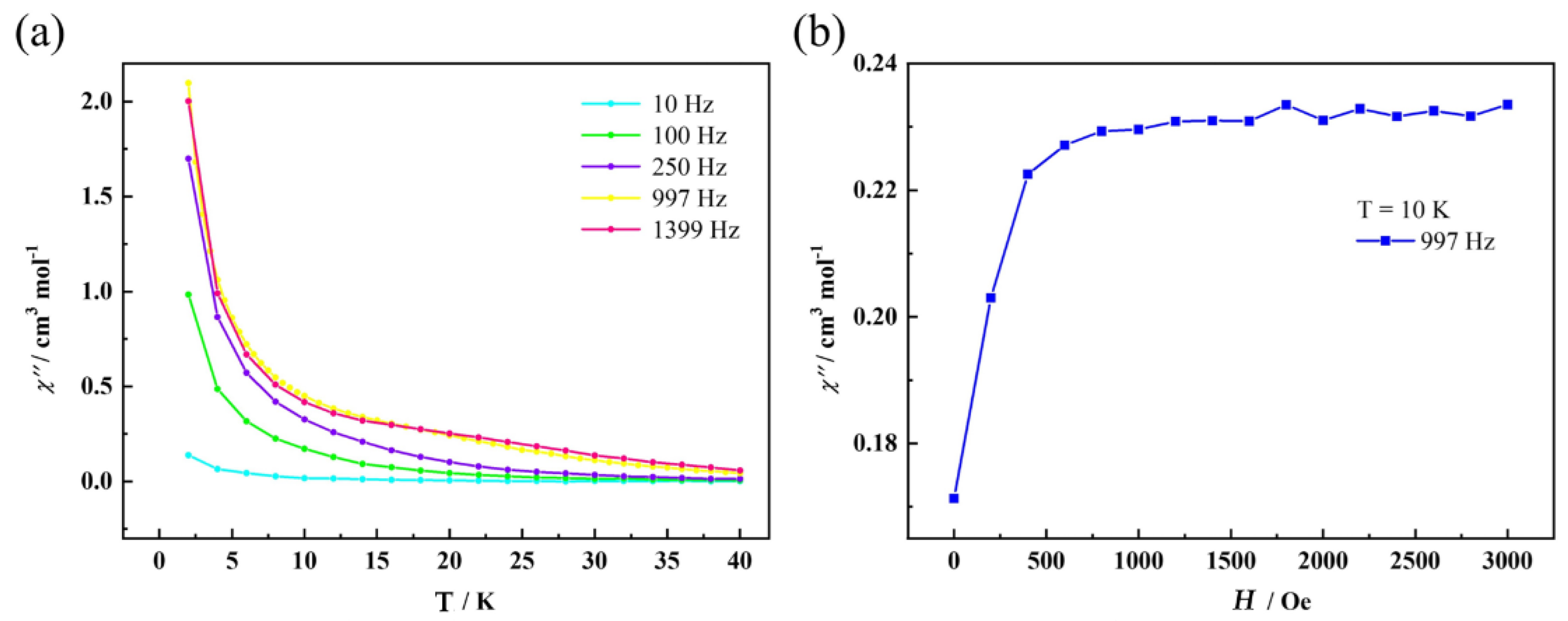

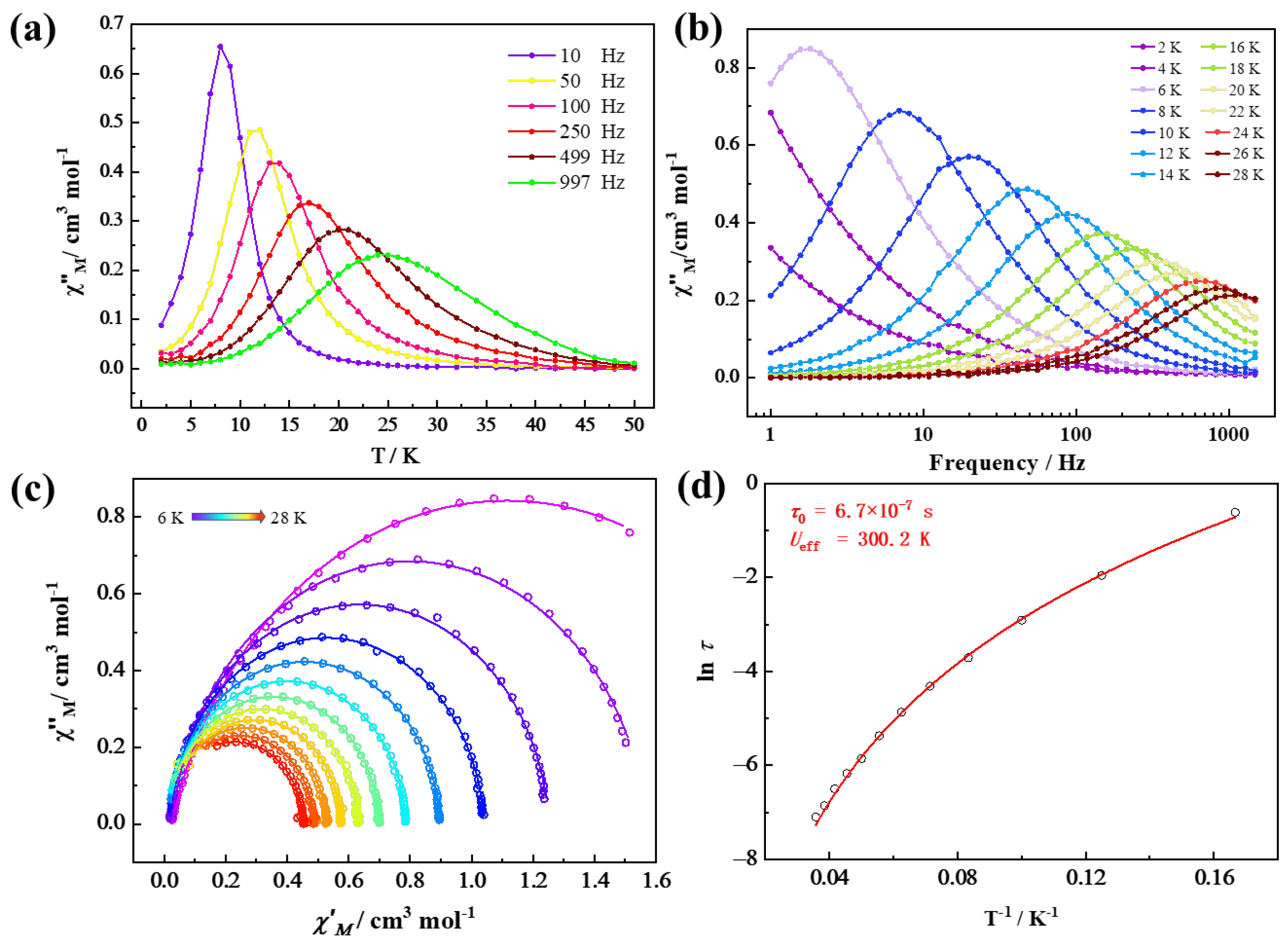

2.3. Magnetism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis and Preparations

3.1.1. Synthesis of the Precursor phenN6-Dy

3.1.2. Synthesis of Complex [Dy(phenN6)(HL’)2]PF6⋅CH2Cl2 (1R/1S)

3.2. Physical Measurements

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chipman, J.A.; Berry, J.F. Paramagnetic Metal–Metal Bonded Heterometallic Complexes. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 2409–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.-S.; Bar, A.K.; Layfield, R.A. Main Group Chemistry at the Interface with Molecular Magnetism. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 8479–8505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kragskow, J.G.C.; Mattioni, A.; Staab, J.K.; Reta, D.; Skelton, J.M.; Chilton, N.F. Spin–phonon coupling and magnetic relaxation in single-molecule magnets. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 4567–4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakrzewski, J.J.; Liberka, M.; Wang, J.; Chorazy, S.; Ohkoshi, S.-i. Optical Phenomena in Molecule-Based Magnetic Materials. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 5930–6050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallini, M.; Gomez-Segura, J.; Ruiz-Molina, D.; Massi, M.; Albonetti, C.; Rovira, C.; Veciana, J.; Biscarini, F. Magnetic Information Storage on Polymers by Using Patterned Single-Molecule Magnets. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 888–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Meng, Y.-S.; Jiang, S.-D.; Wang, B.-W.; Gao, S. Approaching the uniaxiality of magnetic anisotropy in single-molecule magnets. Sci. China Chem. 2023, 66, 683–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damgaard-Møller, E.; Krause, L.; Tolborg, K.; Macetti, G.; Genoni, A.; Overgaard, J. Quantification of the Magnetic Anisotropy of a Single-Molecule Magnet from the Experimental Electron Density. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 21203–21209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Genoni, A.; Gao, S.; Jiang, S.; Soncini, A.; Overgaard, J. Observation of the asphericity of 4f-electron density and its relation to the magnetic anisotropy axis in single-molecule magnets. Nature Chem. 2020, 12, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Perfetti, M. Electronic structure and magnetic anisotropy design of functional metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 490, 215213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, A.K.; Pichon, C.; Sutter, J.-P. Magnetic anisotropy in two- to eight-coordinated transition–metal complexes: Recent developments in molecular magnetism. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 308, 346–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.-S.; Chilton, N.F.; Winpenny, R.E.P.; Zheng, Y.-Z. On Approaching the Limit of Molecular Magnetic Anisotropy: A Near-Perfect Pentagonal Bipyramidal Dysprosium(III) Single-Molecule Magnet. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 16071–16074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.-N.; Xu, G.-F.; Guo, Y.; Tang, J. Relaxation dynamics of dysprosium(III) single molecule magnets. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 9953–9963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Du, S.-N.; Ruan, Z.-Y.; Zhao, X.-J.; Chen, Y.-C.; Liu, J.-L.; Tong, M.-L. Aggregation-induced suppression of quantum tunneling by manipulating intermolecular arrangements of magnetic dipoles. Aggregate 2024, 5, e441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reta, D.; Kragskow, J.G.C.; Chilton, N.F. Ab Initio Prediction of High-Temperature Magnetic Relaxation Rates in Single-Molecule Magnets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 5943–5950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blagg, R.J.; Ungur, L.; Tuna, F.; Speak, J.; Comar, P.; Collison, D.; Wernsdorfer, W.; McInnes, E.J.L.; Chibotaru, L.F.; Winpenny, R.E.P. Magnetic relaxation pathways in lanthanide single-molecule magnets. Nature Chem. 2013, 5, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.-S.; Day, B.M.; Chen, Y.-C.; Tong, M.-L.; Mansikkamäki, A.; Layfield, R.A. Magnetic hysteresis up to 80 kelvin in a dysprosium metallocene single-molecule magnet. Science 2018, 362, 1400–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, S.; Zhu, X.; Ying, B.; Dong, Y.; Sun, A.; Li, D.-f. Macrocyclic Hexagonal Bipyramidal Dy(III)-Based Single-Molecule Magnets with a D6h Symmetry. Cryst. Growth Des. 2023, 23, 6967–6973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gil, Y.; Zhao, C.; Wu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Li, X.L.; Aravena, D.; Tang, J. A conjugated Schiff-base macrocycle weakens the transverse crystal field of air-stable dysprosium single-molecule magnets. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 4982–4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, J.; Yang, Q.; Liu, D.; Tang, J.; Zhang, B. Fine-Tuning the Anisotropies of Air-Stable Single-Molecule Magnets Based on Macrocycle Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Cheng, Z.; Wu, Y.; Jing, R.; Tian, S.-Q.; Chen, L.; Li, Z.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Cui, H.-H.; Yuan, A. Tuning the Equatorial Negative Charge in Hexagonal Bipyramidal Dysprosium(III) Single-Ion Magnets to Improve the Magnetic Behavior. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 3664–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenis, A.S.; Mondal, A.; Giblin, S.R.; Alexandropoulos, D.I.; Tang, J.; Layfield, R.A.; Stamatatos, T.C. 'Kick-in the head': high-performance and air-stable mononuclear DyIII single-molecule magnets with pseudo-D6h symmetry from a [1+1] Schiff-base macrocycle approach. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinehart, J.D.; Long, J.R. Exploiting single-ion anisotropy in the design of f-element single-molecule magnets. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 2078–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Tolpygin, A.O.; Mamontova, E.; Lyssenko, K.A.; Liu, D.; Albaqami, M.D.; Chibotaru, L.F.; Guari, Y.; Larionova, J.; Trifonov, A.A. An unusual mechanism of building up of a high magnetization blocking barrier in an octahedral alkoxide Dy3+-based single-molecule magnet. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 1166–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, H.; Xia, Z.; Ungur, L.; Liu, D.; Chibotaru, L.F.; Ke, H.; Chen, S.; Gao, S. An Inconspicuous Six-Coordinate Neutral DyIII Single-Ion Magnet with Remarkable Magnetic Anisotropy and Stability. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 7158–7166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.-S.; Yu, K.-X.; Reta, D.; Ortu, F.; Winpenny, R.E.P.; Zheng, Y.-Z.; Chilton, N.F. Field- and temperature-dependent quantum tunnelling of the magnetisation in a large barrier single-molecule magnet. Nature Commun. 2018, 9, 3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhao, C.; Feng, T.; Liu, X.; Ying, X.; Li, X.-L.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Tang, J. Air-Stable Chiral Single-Molecule Magnets with Record Anisotropy Barrier Exceeding 1800 K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 10077–10082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.-J.; Wu, S.-Q.; Li, J.-X.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Sato, O.; Kou, H.-Z. Structural Modulation of Fluorescent Rhodamine-Based Dysprosium(III) Single-Molecule Magnets. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 2308–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.-S.; Yu, K.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Liu, C.-M.; Kou, H.-Z. From dinuclear to two-dimensional Dy(III) complexes: single crystal–single crystal transformation and single-molecule magnetic behavior. J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 1550–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canaj, A.B.; Dey, S.; Martí, E.R.; Wilson, C.; Rajaraman, G.; Murrie, M. Insight into D6h Symmetry: Targeting Strong Axiality in Stable Dysprosium(III) Hexagonal Bipyramidal Single-Ion Magnets. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 14146–14151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-H.; Zhai, Y.-Q.; Chen, W.-P.; Ding, Y.-S.; Zheng, Y.-Z. Air-Stable Hexagonal Bipyramidal Dysprosium(III) Single-Ion Magnets with Nearly Perfect D6h Local Symmetry. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 16219–16224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.-J.; Luo, Q.-C.; Li, Z.-H.; Zhai, Y.-Q.; Zheng, Y.-Z. Bis-Alkoxide Dysprosium(III) Crown Ether Complexes Exhibit Tunable Air Stability and Record Energy Barrier. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2308548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Zhu, Z.; Li, X.-L.; Tang, J. Air-stable chiral mono- and dinuclear dysprosium single-molecule magnets: steric hindrance of hexaazamacrocycles. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 4049–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.-S.; Liu, C.-M.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Kou, H.-Z. Trinuclear Dy(III) Single-Molecule Magnets with Two-Step Relaxation. Chin. J. Chem. 2023, 41, 2641–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, S.; Li, X.-L.; Mansikkamäki, A.; Tang, J. Air-Stable Dy(III)-Macrocycle Enantiomers: From Chiral to Polar Space Group. CCS Chem. 2022, 4, 3762–3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gómez-Coca, S.; Dolinar, B.S.; Yang, L.; Yu, F.; Kong, M.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Song, Y.; Dunbar, K.R. Hexagonal Bipyramidal Dy(III) Complexes as a Structural Archetype for Single-Molecule Magnets. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 2610–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.S.; Blackmore, W.J.A.; Zhai, Y.Q.; Giansiracusa, M.J.; Reta, D.; Vitorica-Yrezabal, I.; Winpenny, R.E.P.; Chilton, N.F.; Zheng, Y.Z. Studies of the Temperature Dependence of the Structure and Magnetism of a Hexagonal-Bipyramidal Dysprosium(III) Single Molecule Magnet. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Yao, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C.; Zhou, Y.-Q.; Du, S.-N.; Liu, J.-L.; Tong, M.-L. Engineering a high-barrier d-f single-molecule magnet centered with hexagonal bipyramidal Dy(III) unit. Sci. China Chem. 2024, 67, 3291–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Li, D.-Y.; Cao, C.; Luo, T.-K.; Hu, Z.-B.; Peng, Y.; Liu, S.-J.; Zheng, Y.-Z.; Wen, H.-R. Effect of Substituents in Equatorial Hexaazamacrocyclic Schiff Base Ligands on the Construction and Magnetism of Pseudo D6h Single-Ion Magnets. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 21909–21918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenis, A.S.; Mondal, A.; Giblin, S.R.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Psycharis, V.; Alexandropoulos, D.I.; Tang, J.; Layfield, R.A.; Stamatatos, T.C. Unveiling new [1+1] Schiff-base macrocycles towards high energy-barrier hexagonal bipyramidal Dy(III) single-molecule magnets. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 12730–12733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).