Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

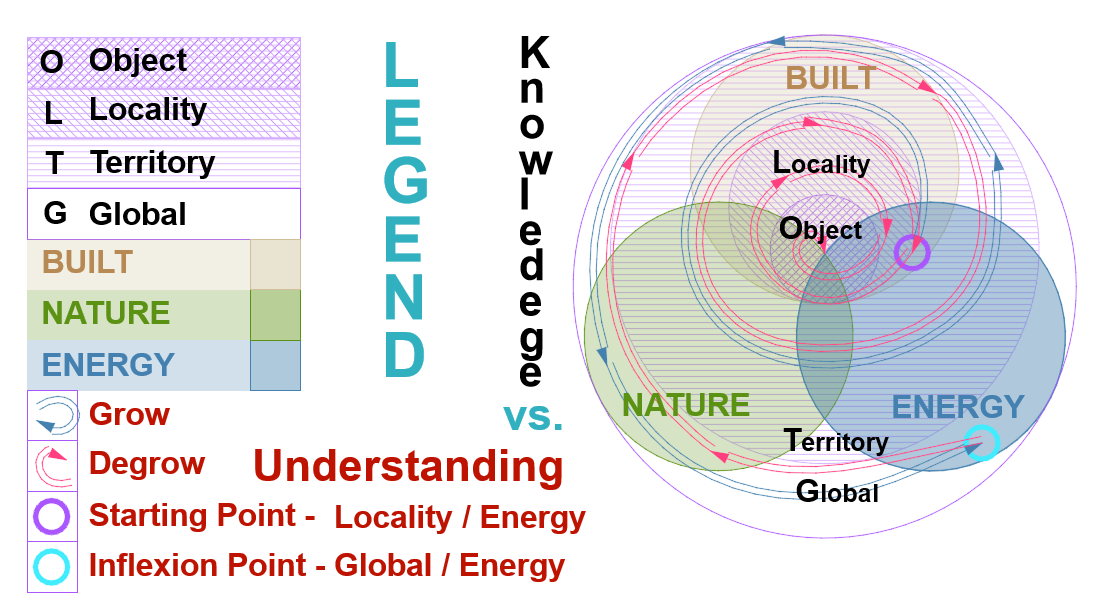

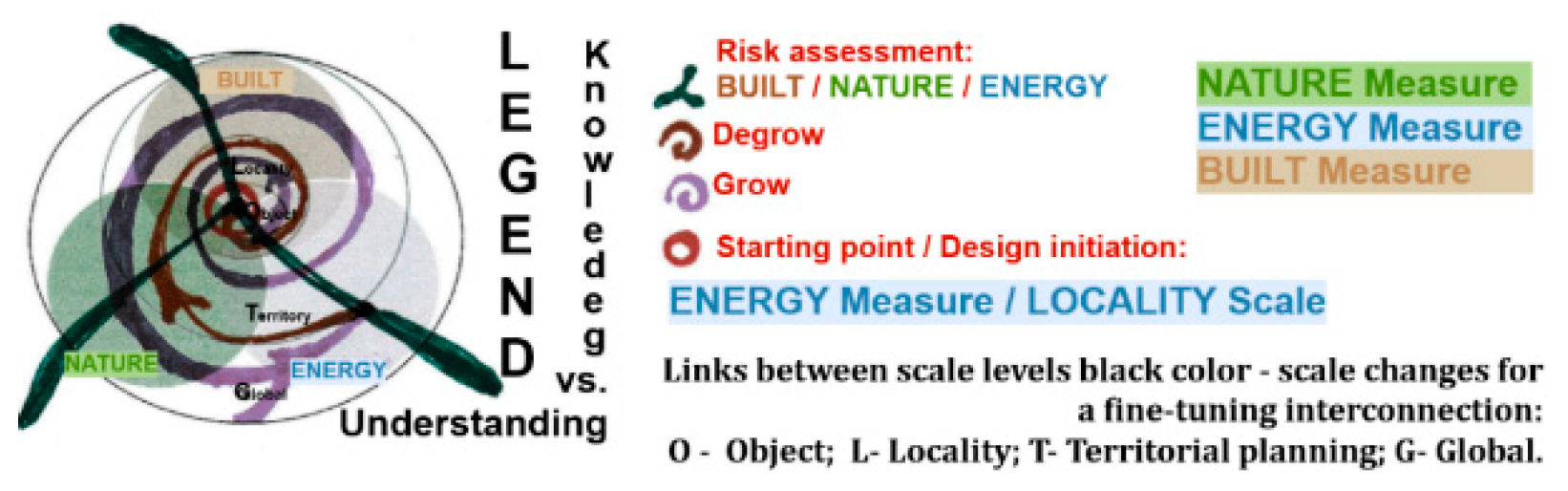

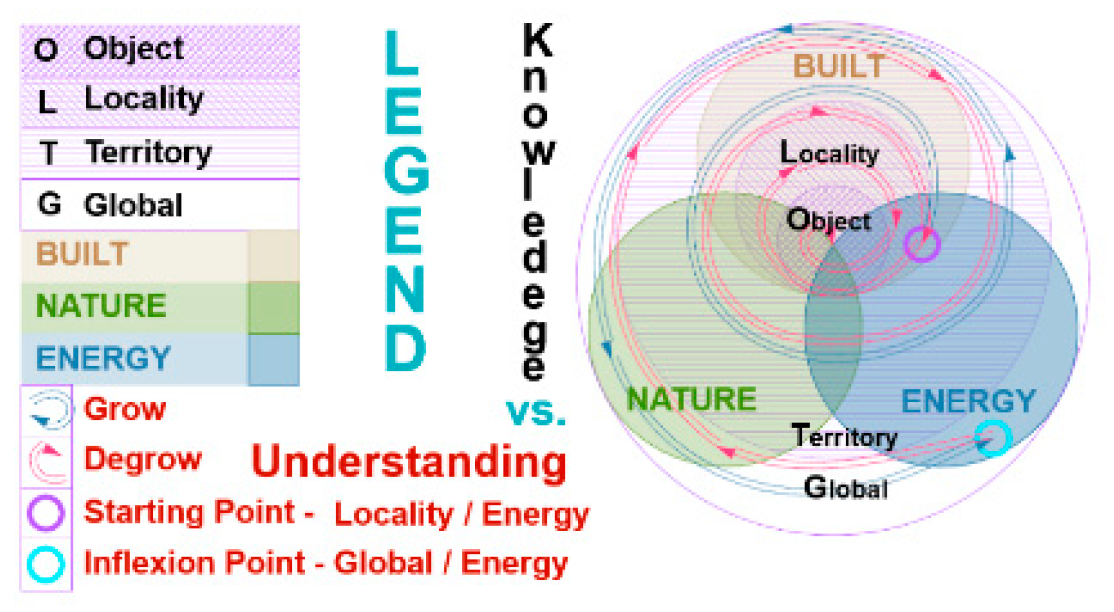

Holistic Framework - Methodology

- "Technical vs. Humanist" as BUILT Criteria

- "Technology vs. Tradition" as NATURE Criteria

- "Active vs. Passive" as ENERGY Criteria

- B—BUILT+ E—ENERGY+ N—NATURE on the scales from small to large,

- O—Object, L—Locality, T—Territory, G—Global, applied for projects on any starting points.

| Acronym | measure↓ | LEGEND - MEASURE/SCALE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N - O | Nature - Object | NATURE Technology | OBJECT plot scale |

| N - L | Nature - Locality | NATURE Technology | LOCALITY dam/polder scale |

| N - T | Nature - Territory | NATURE Technology | TERRITORY hydrologic basin scale |

| N - G (*) | Nature - Global (*) | NATURE Tradition | GLOBAL scale (*) |

| B - O | Built - Object | BUILT Technical | OBJECT plot scale |

| B - L | Built - Locality | BUILT Technical | LOCALITY dam/polder scale |

| B - T | Built - Terilor | BUILT Technical | TERRITORY hydrologic basin scale |

| B - G (*) | Built - Global (*) | BUILT Humanist | GLOBAL scale (*) |

| E - O | Energy - Object | ENERGY Active | OBJECT plot scale |

| E - L | Energy - Locality | ENERGY Active | LOCALITY dam/polder scale |

| E - T | Energy - Territory | ENERGY Active | TERRITORY hydrologic basin scale |

| E – G (*) | Energy – Global (*) | ENERGY Passive | GLOBAL scale (*) |

| (*) The Global-scale is the "correct assessment," including sine qua non-design principles and the Humanist related to Understanding. | |||

| 1 | Climate change mitigation | renewable energy production | Substantial contribution |

| 2 | Climate change adaptation | flood protection, [NBS] 2 | Substantial contribution |

| 3 | DNSH The sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources | Polder - wetland | Substantial contribution |

| 4 | DNSH The transition to a circular economy | recycled materials, preserved built works | Substantial contribution |

| 5 | DNSH Pollution prevention and control | attention needed - materials | DNSH |

| 6 | DNSH The protection and restoration of Biodiversity and ecosystems | Wildlife corridors with biocapacity/biodiversity - wetland impact | Substantial contribution |

NATURE10 — Regenerative Dyad "Tradition vs. Technology"

| Scale Global | correct assessment |

|---|---|

| Green | Increased Biodiversity of local species measures (after invasive species issues) |

| Agriculture | Following the Anthropocene-specific era of industrial agriculture, locally adapted cultures for regenerative. Pesticide-free European agriculture |

| Blue | Water management - longitudinal connectivity & transversal connectivity related to wild corridors (after Anthropocene excessive Hydropower measures, excessive micro hydro number) |

| Biodiversity | Wetland areas and longitudinal watercourse connectivity (following the Antropocene’s decreased Biodiversity) |

| Soil | Soil health measures are needed after the Anthropocene - specific soil degradation. |

| Risks related | Water Scarcity / Risks relevant to energy production are to be evaluated |

| Scale Object | plot |

| Green | Increasing biocapacity/ biodiversity |

| Agriculture | Pesticide-free crop rotation, Increasing Biodiversity |

| Blue | Irrigation canals needed/ ponds needed |

| Biodiversity | Increasing biodiversity measures, connectivity related to wild corridors |

| Soil | Pesticide-free crop rotation |

| Risks related | Water footprint/ Energy production to be evaluated |

| Scale Locality | dam/polder |

| Green | Increasing biocapacity/ biodiversity |

| Agriculture | Pesticide-free crop rotation, Increasing Biodiversity |

| Blue | Irrigation canals needed/ ponds&dams needed, longitudinal connectivity & transversal connectivity related to wild corridors |

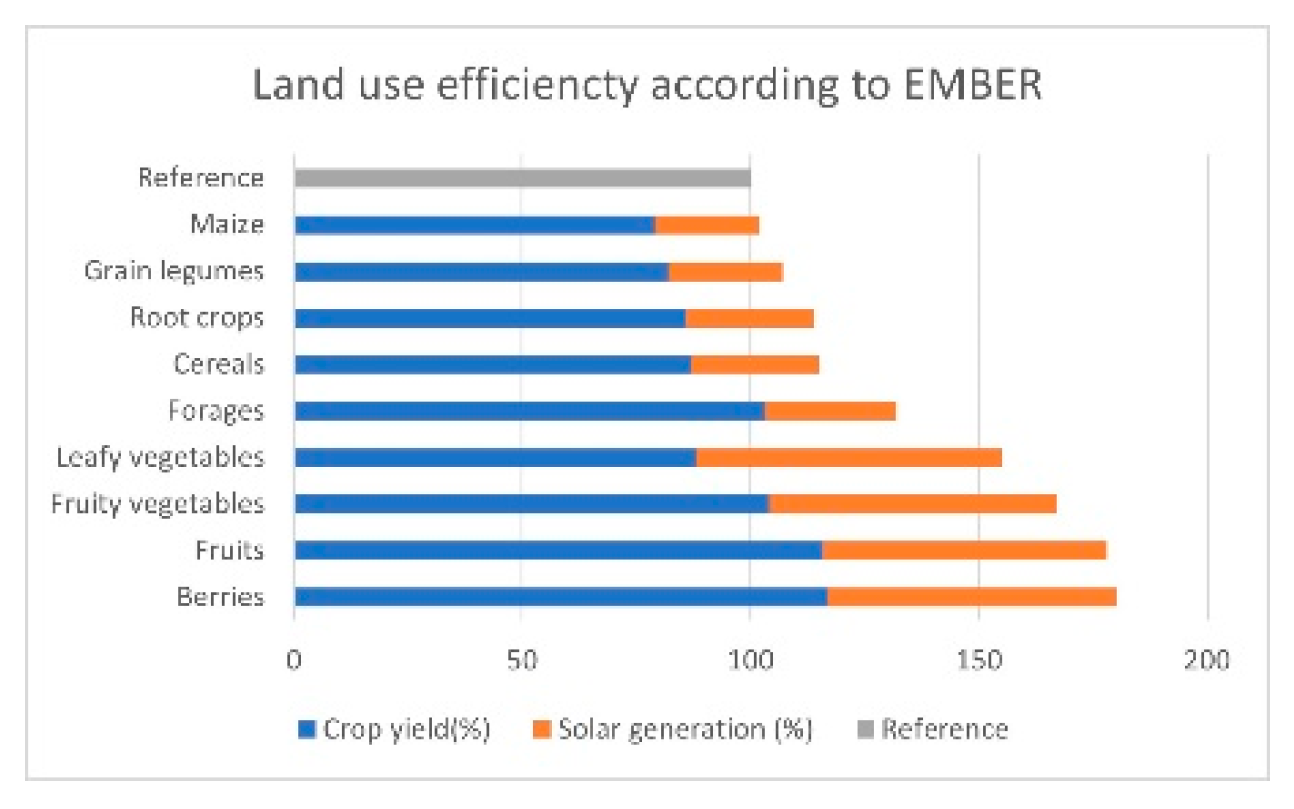

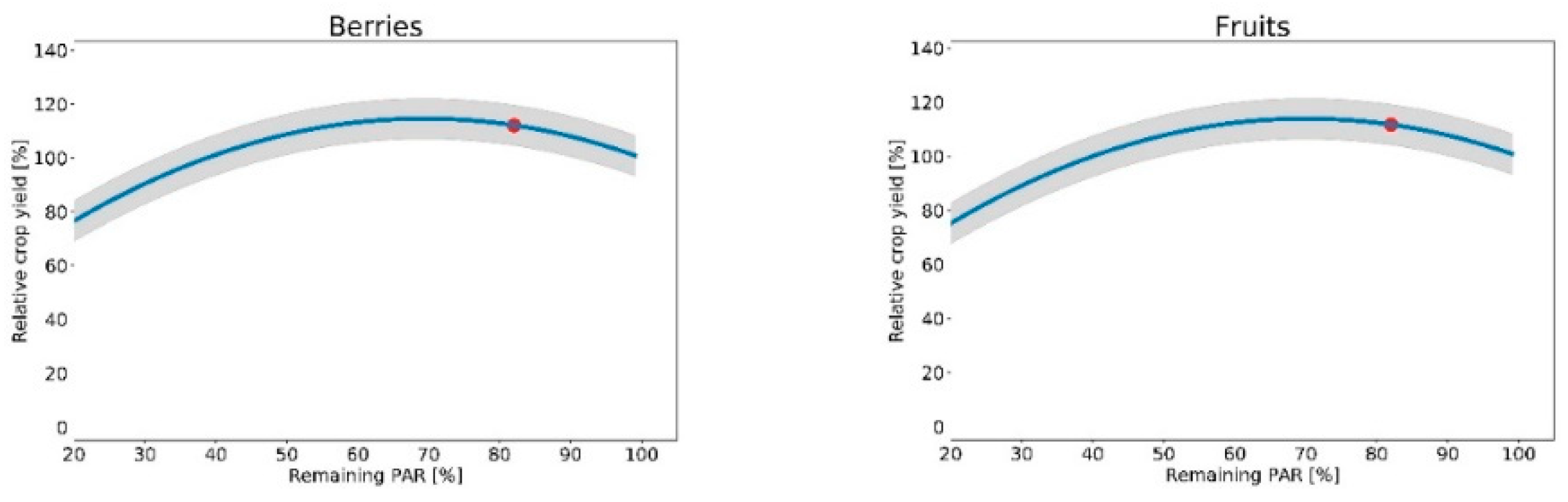

| Biodiversity | Biodiversity improvement measures, such as meander renaturation, connectivity related to wild corridors |

| Soil | Pesticide-free crop rotation in an agricultural community |

| Risks related | Water footprint/ Energy production to be evaluated |

| Scale Territory | Hydrological Basin |

| Green | Increasing biocapacity/ biodiversity |

| Agriculture | Pesticide-free crop rotation, Increasing Biodiversity |

| Blue | Wetland areas, dams needed, longitudinal connectivity & transversal connectivity related to wild corridors |

| Biodiversity | Increasing Biodiversity measures for local species, connectivity related to wild corridors |

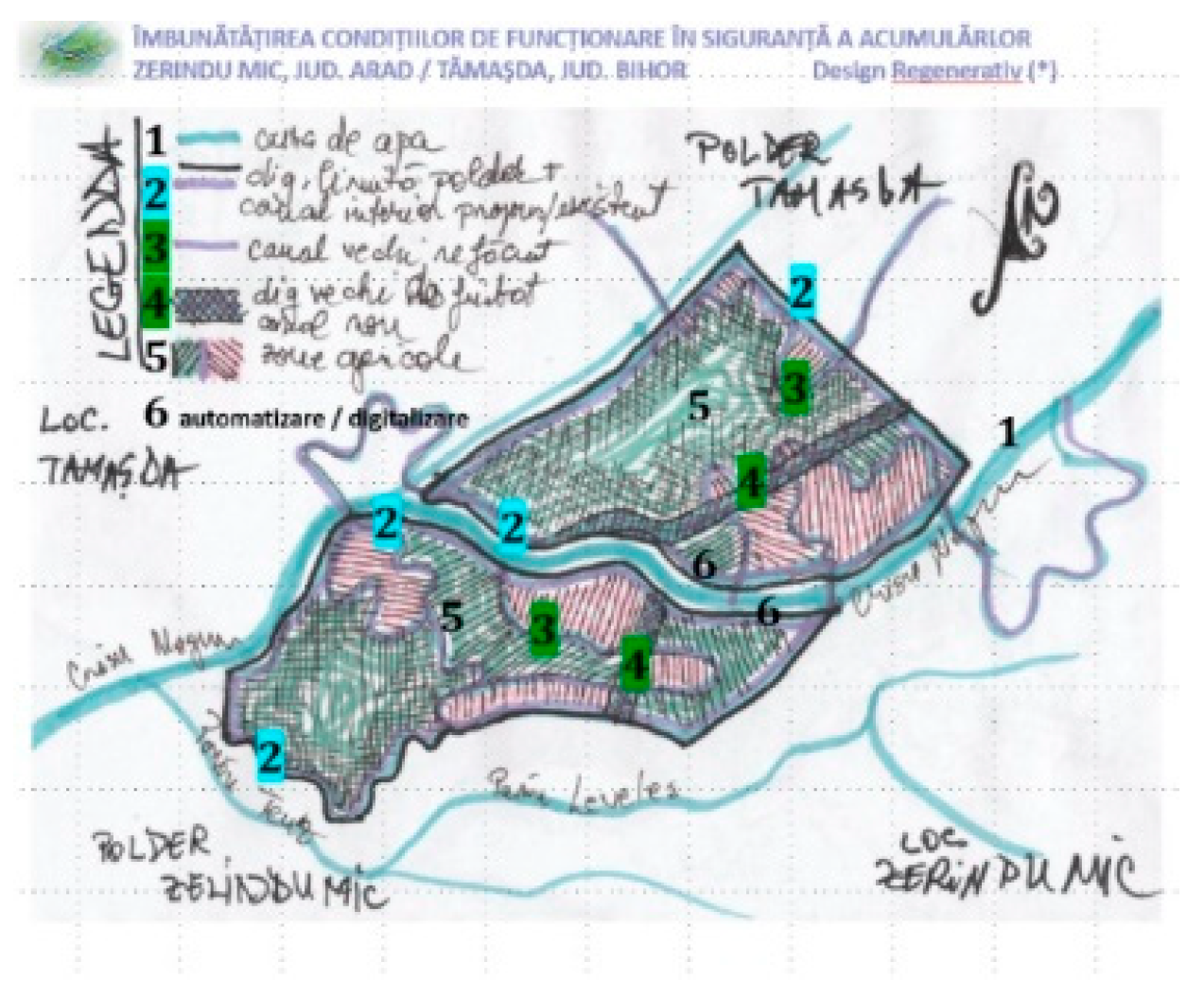

| Soil | Soil health improvement measures |

| Risks related | Water Scarcity /Biodiversity issues/ Energy production to be evaluated |

BUILT11 — Regenerative Dyad "Humanist vs. Technical"

| Scale Global | correct assessment |

|---|---|

| Recyclable | The existing built environment that supports PV systems |

| Heritage Value | Revitalizing the traditional household after vernacular heritage-specific degradation in the Anthropocene |

| Cultural Landscape | Revitalizing the cultural landscape after a possible Anthropocene-specific degradation |

| Social | Traditional agricultural plots for energy community / agrarian communities’ circular metabolism community.12 |

| Degrowth | Revitalizing an intangible heritage through measures specific to traditional culture encompasses daily life routines that follow the circadian cycle and agricultural activities that follow the lunar cycle |

| Risks related | Risks relevant to energy production are to be evaluated. |

| Scale Object | plot |

| Recyclable | Built environment rehabilitation - photovoltaic support |

| Heritage Value | Cultural landscape preserved on traditional plots, particular heritage elements, as fences or others |

| Cultural Landscape | Traditional landscape design |

| Social | Social Impact of Agrarian/ Energy Communities |

| Degrowth | Agrarian/Energy communities according to a traditional design |

| Risks related | Risk of aggressive intervention in the cultural landscape |

| Scale Locality | dam/polder |

| Recyclable | Circular metabolism on a large scale as a metropolitan/ basin scale12 |

| Heritage Value | Industrial dams – evaluated as industrial/technical heritage value |

| Cultural Landscape | Cultural heritage preservation |

| Social | Human-centred measures large-scale, infrastructure interventions with social impact evaluated |

| Degrowth | Degrowth and interconnectivity in large-scale infrastructure interventions |

| Risks related | Energy production / Biodiversity to be evaluated |

| Scale Territory | hydrological basin |

| Recyclable | Heritage preservation as a circular economy measure |

| Heritage Value | Heritage studies, thematic heritage visit route basinal scale |

| Cultural Landscape | Cultural landscape studies |

| Social | Circular metabolism12 / Energy / Agrarian communities |

| Degrowth | Heritage preservation as a degrow measure |

| Risks related | Biodiversity issues / Energy production to be evaluated |

ENERGY13 14—Regenerative Dyad "Passive vs. Active"

| Scale Global | correct assessment |

|---|---|

| Carbon footprint | Carbon sequestration through nature-based solutions measures |

| Water footprint | Related to hydrogen production and hydropower production |

| Renewable Energy | Agrivoltaics, translucent solar panels on irrigation canals, micro-hydro fish-friendly |

| Energy Consumption | Hydrogen production |

| Risks related | Water / Energy / Built / Biodiversity risks related |

| Scale Object | plot |

| Carbon footprint | Plot Carbon footprint / Carbon storage to be assessed |

| Water footprint | Irrigation needed |

| Renewable Energy | PV production to be assessed |

| Energy Consumption | Irrigation pump consumption to be evaluated |

| Risks related | Water / Biodiversity issues /Energy / Built risks related |

| Scale Locality | dam/polder |

| Carbon footprint | Carbon footprint / Carbon storage to be assessed |

| Water footprint | Hydrogen and hydropower production to be evaluated Irrigation needed, Biodiversity wetland needs |

| Renewable Energy | Hydrogen production/PV production to be assessed |

| Energy Consumption | Irrigation pumps consumption/Consumption in Hydrogen production to be evaluated |

| Risks related | Water / Biodiversity issues /Energy / Built risks related |

| Scale Territory | hydrological basin |

| Carbon footprint | Carbon storage to be assessed |

| Water footprint | Hydrogen and hydropower production and other consumers to be evaluated |

| Renewable Energy | Production to be assessed/ potential production |

| Energy Consumption | Consumers/potential consumers |

| Risks related | Water / Biodiversity issues /Energy / Built risks related. |

New BUILT [S-SV] vs. [Z-AR] Regenerative Dyad "Humanist vs. Technical"

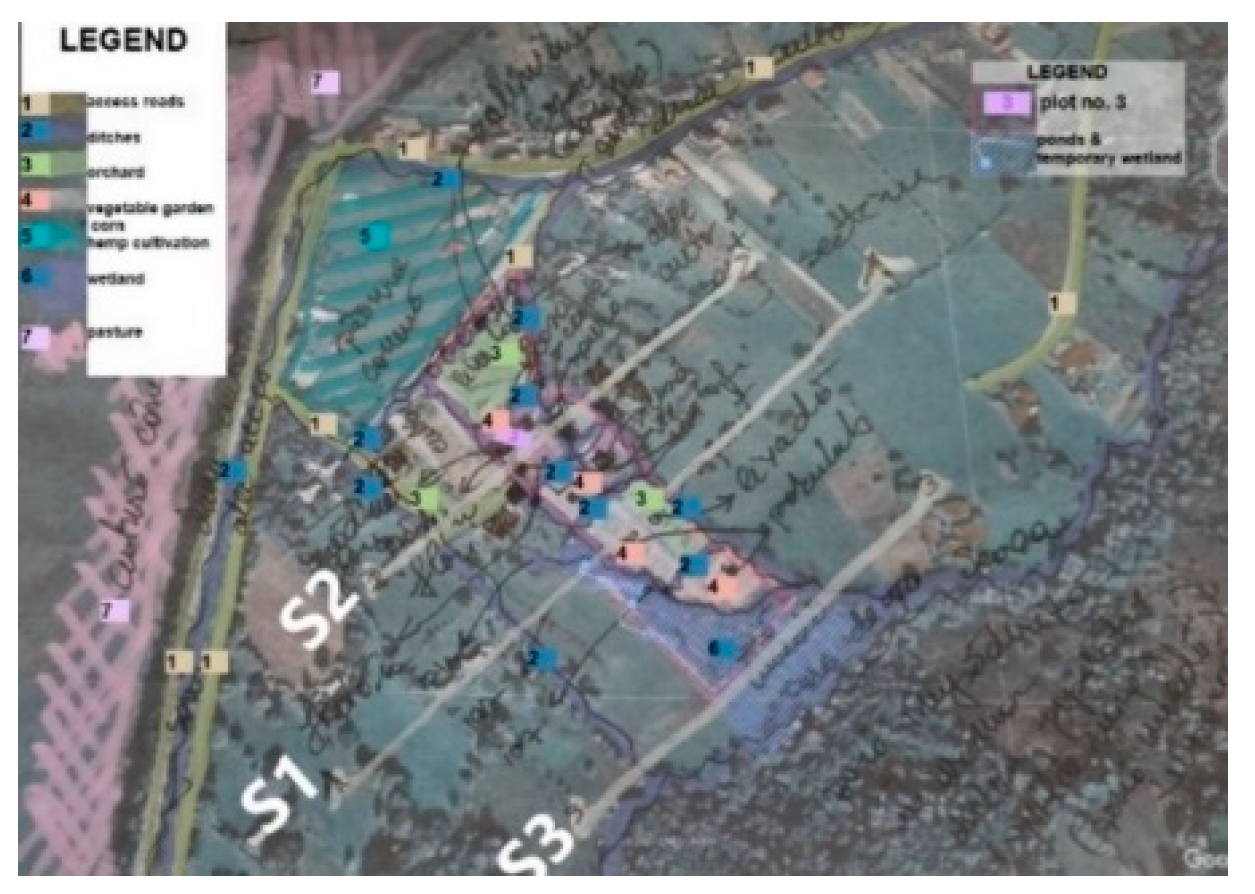

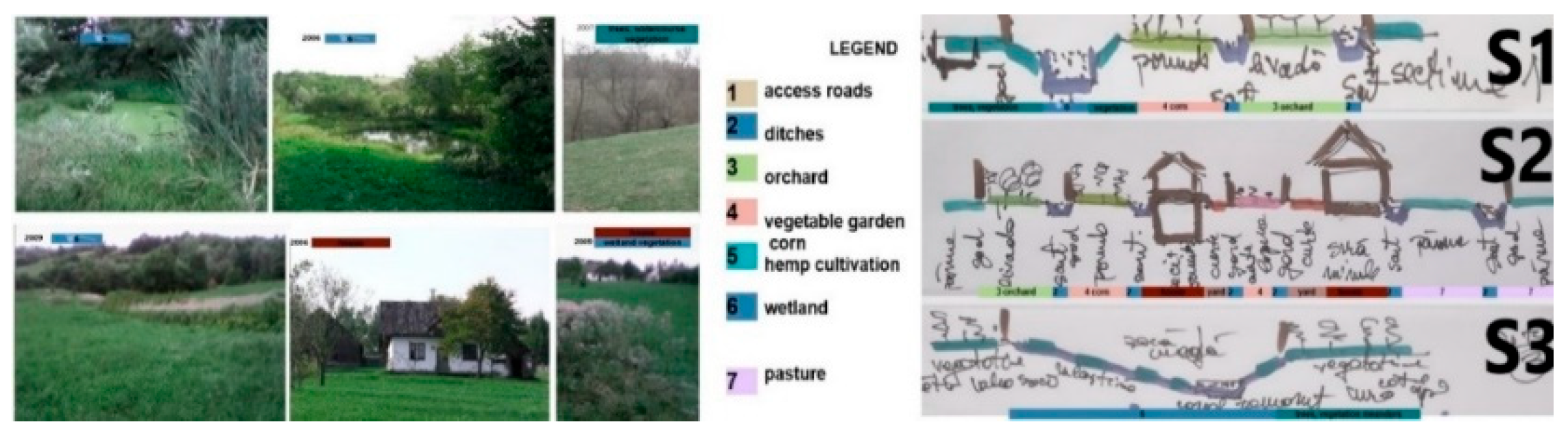

Traditional Rural Plots [S-SV] vs. [Z-AR] Antropocen Agricultural Plots

BUILT [S-SV] Study Case Traditional Rural Plots – Boroaia, Suceava County, Romania

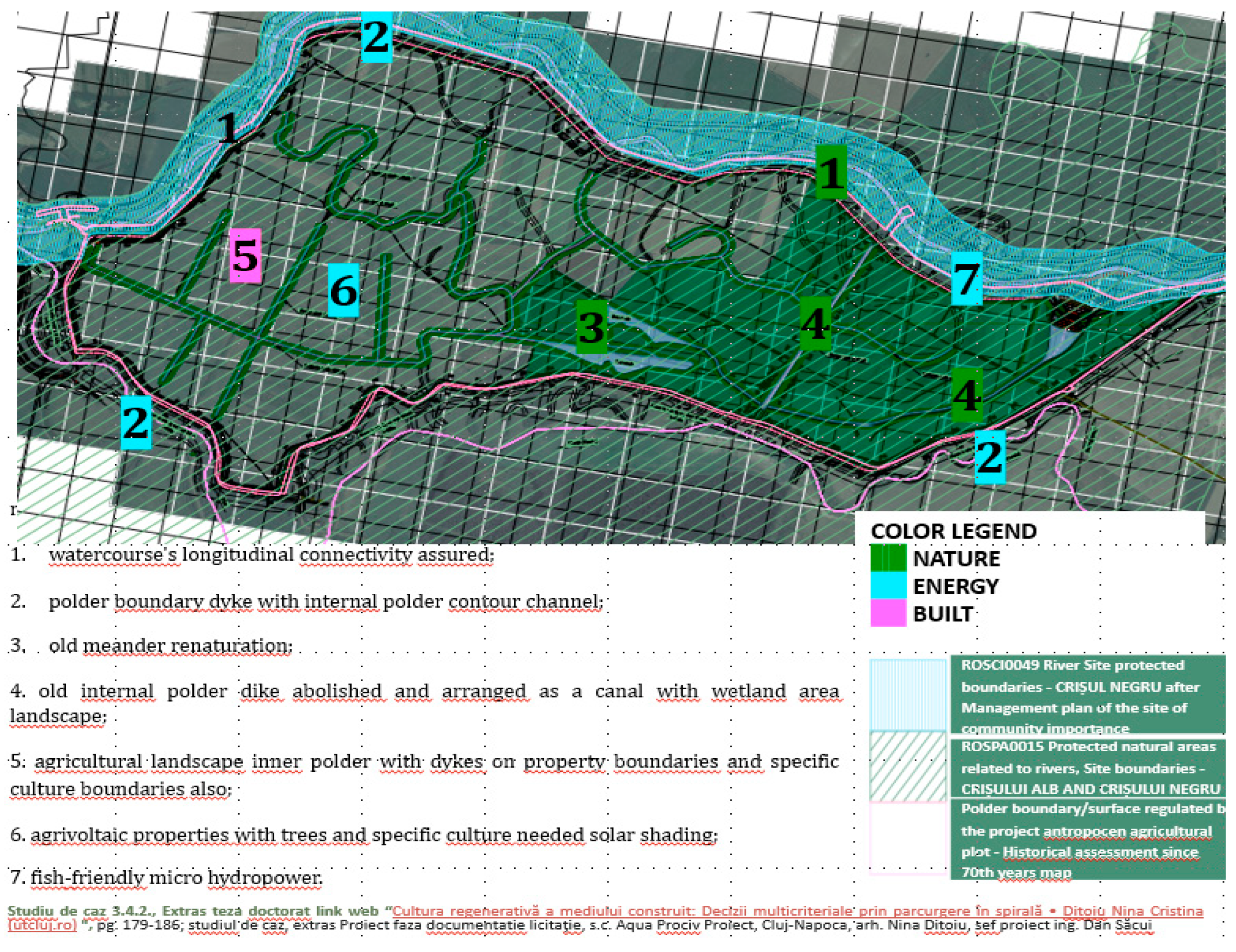

BUILT [Z-AR]35 Study Case Anthropocene Agricole Plots - Zerind Polder, Arad County, Romania

New NATURE [Z-AR] Regenerative Dyad "Tradition vs. Technology"

| Carbon Sequestration (Tones of Carbon per year) |

Boreal Forest | Temperate Forest | Temperate Grassland | Tropical Forest | Desert and semi-desert | Tundra | Wetland | Tropical Savana | Croplands |

| Surface (ha) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Vegetation Carbon Sequestration | 64 | 120 | 7 | 120 | 2 | 6 | 43 | 29 | 2 |

| Soil Carbon Sequestration | 344 | 123 | 236 | 123 | 42 | 127 | 643 | 117 | 80 |

| Overall Carbon Sequestration | 408 | 243 | 243 | 243 | 44 | 133 | 686 | 146 | 82 |

| Biodiversity metrics | G-res tool metric |

|---|---|

| Cropland Grassland Heathland and shrub / Tundra Intertidal Hard Structures Intertidal sediment Lakes Sparsely vegetated land Urban Woodland and Forest Coastal Saltmarsh Rivers |

Cropland Grassland/Shrubland Bare area Permanent snow/Ice Waterbodies Settlements Forest Drained Peatlands Wetland |

New ENERGY [Z-AR] Regenerative Dyad "Passive vs. Active"

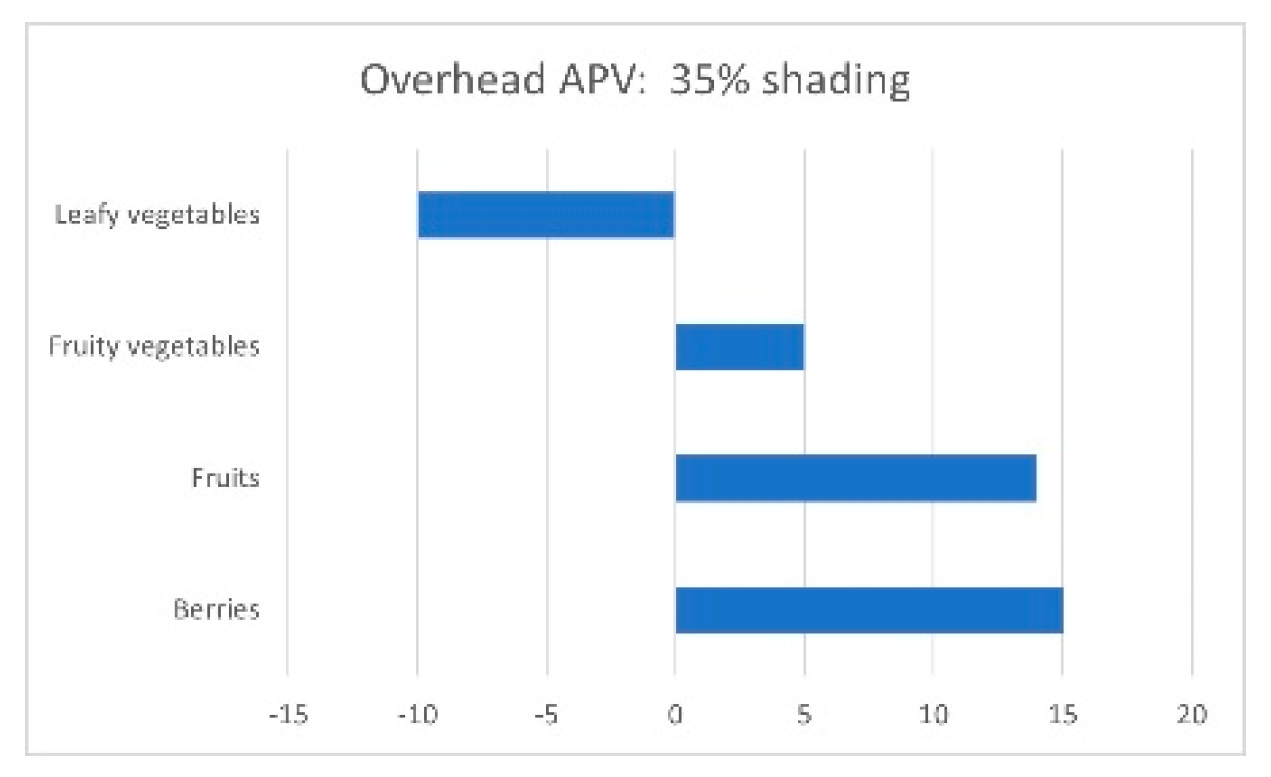

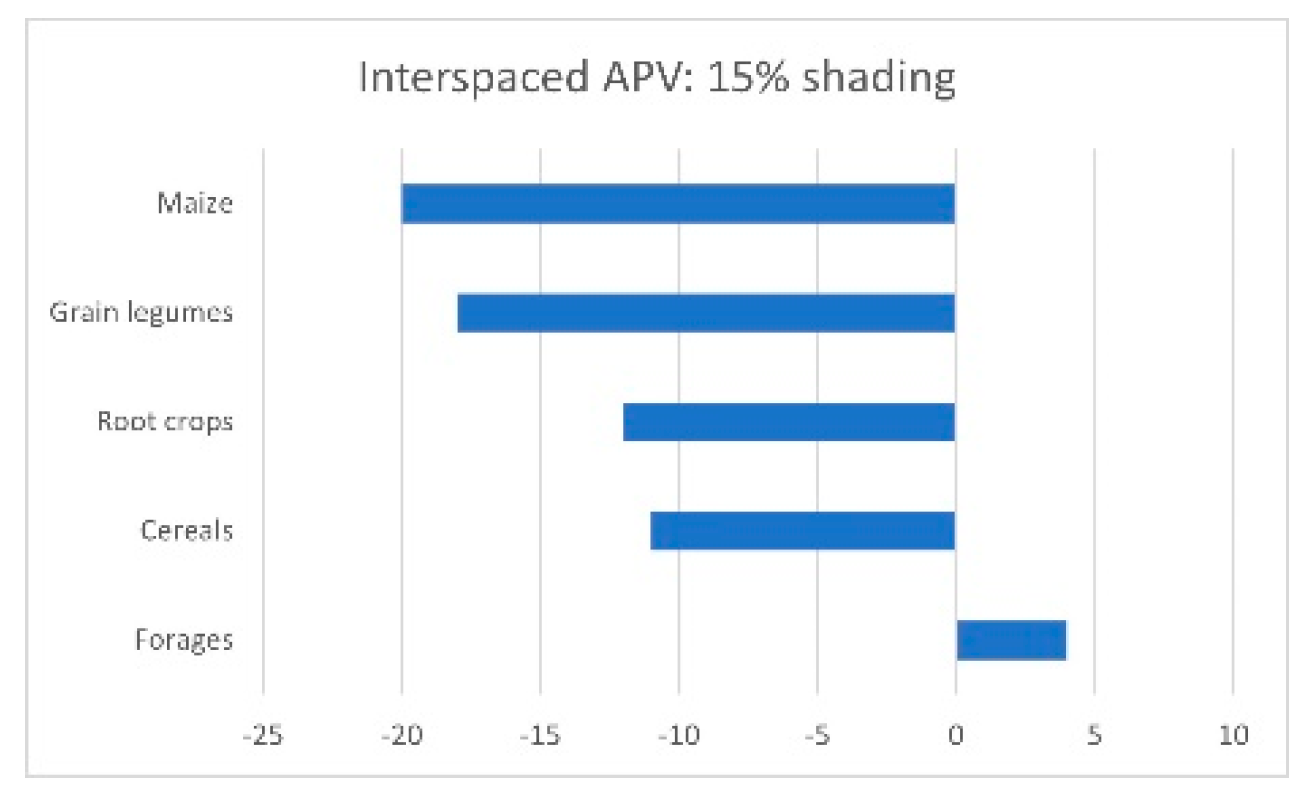

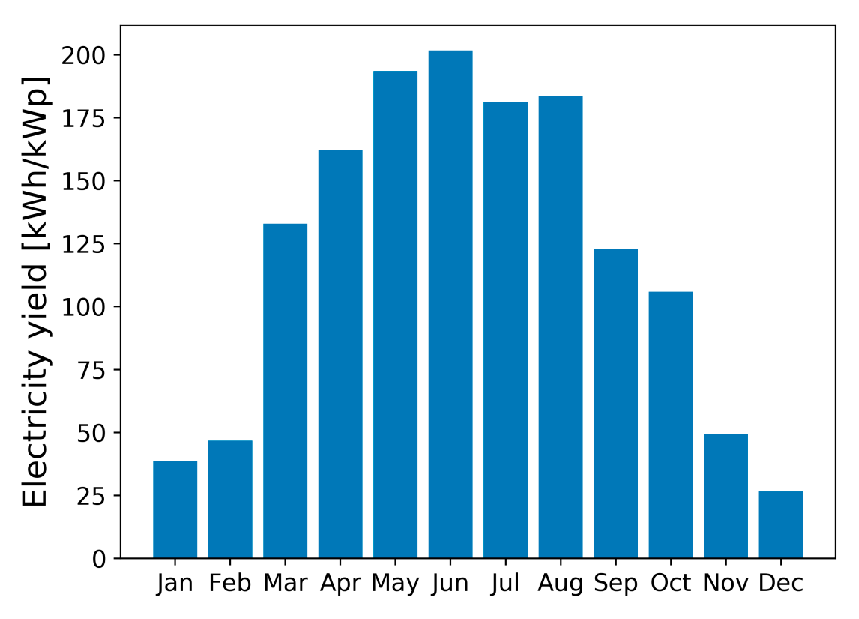

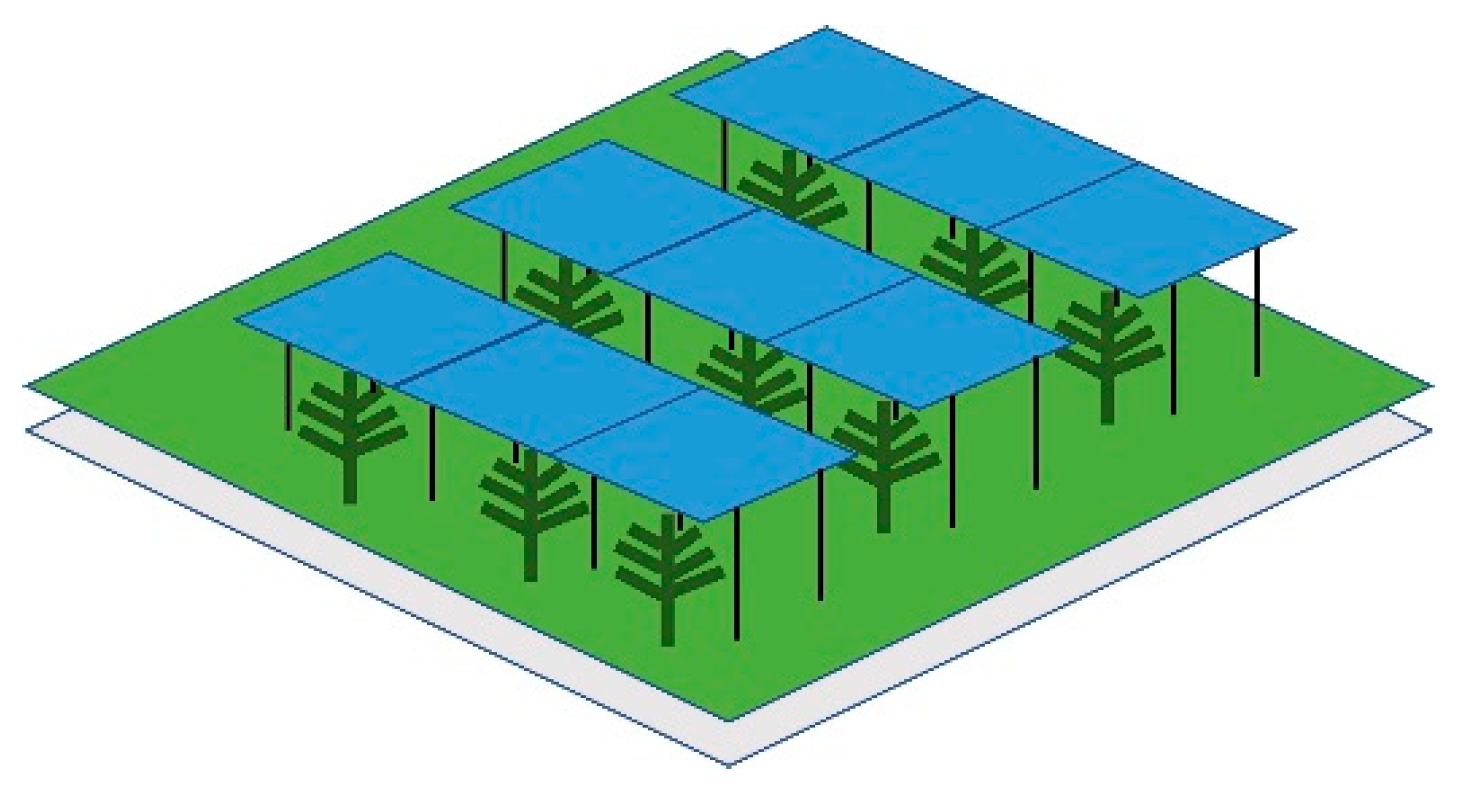

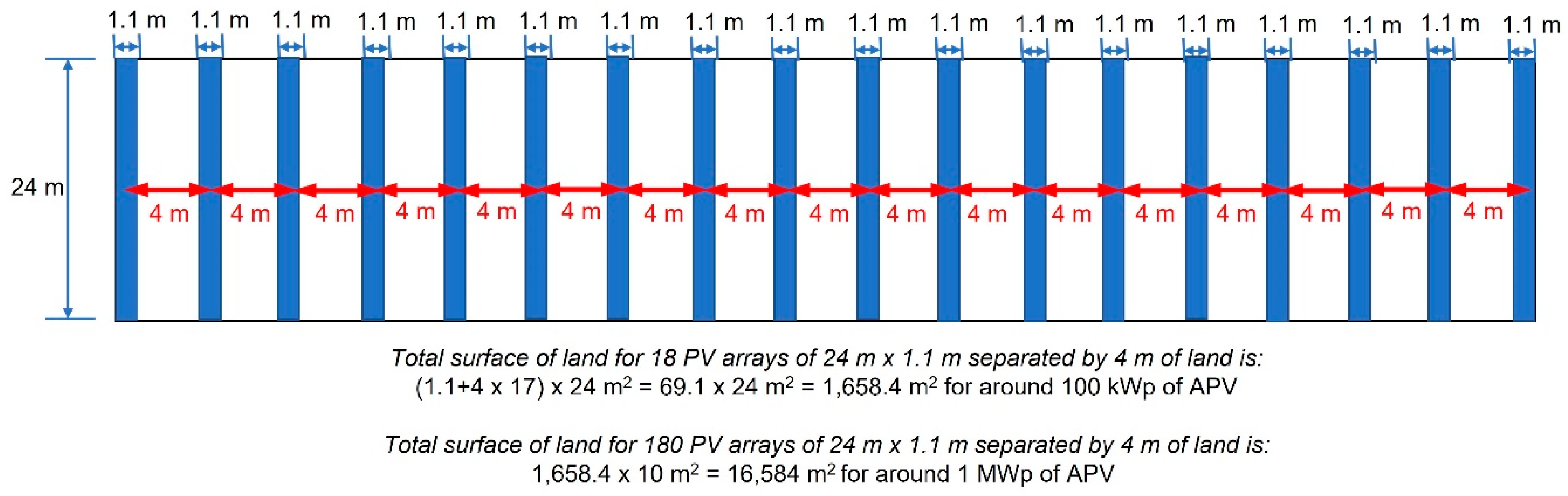

Agrivoltaics Production

Photovoltaic Covering Irrigation Canals.

Solar Storage Potential

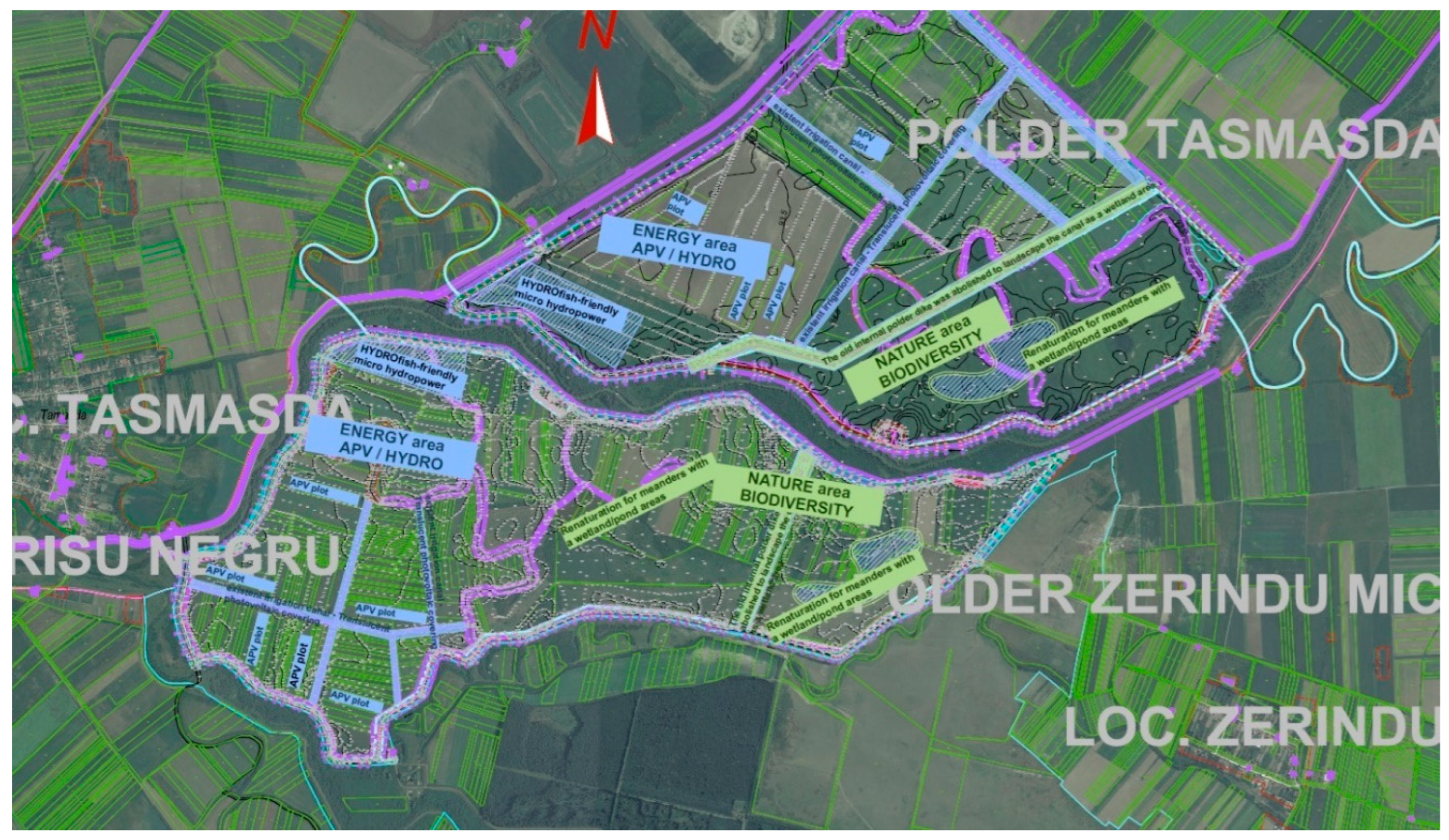

- ENERGY AREA: APV plots, fish-friendly micro-hydropower, and existing irrigation canal—transparent photovoltaic covering;

- NATURE AREA: Renaturation for meanders with wetland/pond areas. The old internal polder dike was removed to transform the canal into a wetland area.

Discussions

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

Technical:

|

Technical:

|

| Opportunities | Threats |

Technical:

|

Technical:

|

| The need for a balance between Technical and Humanistic perspectives and between Energy and Nature is crucial. This discussion highlights the differences in the interdisciplinary authors’ team. There are also precise measurements needed, such as accurate figures in energy production or budgeting, and the importance of preserving Biodiversity, which can be accounted for through biodiversity credits or carbon credits as part of the same budget. Additionally, the topic encompasses the concept of double materiality, a widely discussed concept internationally. Understanding the reasons that drive the need for a taxonomy with environmental DNSH principles, the Knowledge vs Understanding spiral that expands and contracts scales and metrics in Nature, Energy, and Built environments, involving relevant multidisciplinary experts, is about conquering Understanding through multidisciplinary Knowledge. There is no single best option. It is about making compromises, rechecking, and reviewing the spiral as often as necessary. In particular cases, the technical design should be developed to apply any other necessary measures related to Built/heritage or Nature/Green, trees, or Nature/Biodiversity risks. The method was demonstrated in a particular water-related environment and explained the need to solve Energy-related risks following the other crucial issues in Nature & Built, which needed to be achieved, at least after the DNSH principles. The discussions will follow a technical approach related to other necessary studies. The case study is more about the conceptual design stage, proposing to achieve essential Energy without ignoring Nature or Built goals. It is so relevant for this preliminary design stage, when it is opportune to implement other goals, not just for solar Energy, that in the final stages, it will not be possible or at least more foreseeable if ignored from the beginning a proper conceptual design. | |

Conclusion

Acronyms

Acknowledgment

Webography

- https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/en/publications/studies/agrivoltaics-opportunities-for-agriculture-and-the-energy-transition.html

References

- Alexander, Christopher., The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe-The Phenomenon of Life (Center for Environmental Structure, Berkeley, California, 2014, first ed. 1980).

- Bellstedt, Carolin., Gerardo Ezequiel Martín Carreño, Aristide Athanassiadis, Shamita Chaudhry, METABOLISM of CITIES (CityLoops-D4.4–Urban Circularity Assessment Method, Version 1.0 <2022-05-31>).

- Bennett, John G., Elementary systematics: A Tool for Understanding Wholes (Bennett Books, the Estate of J.G. Bennett, United States of America, 1993).

- Brown, Martin., FutuRestorative: Working Towards a New Sustainability (RIBA Publishing, 2016).

- Czyżak, Paweł., Tatiana Mindeková, Empowering farmers in Central Europe: the case for agri-PV (EMBER: Published, 2024).

- Denholm, Paul., Mohammed Hand, Maddalena Jackson, Sini Ong, Land-Use Requirements of Modern Wind Power Plants in the United States (National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Innovation for Our Energy Future, Technical Report: NREL/TP-6A2-45834, 2009).

- Dilip da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers: Alexander’s Eye and Ganga’s Descent (Publisher: University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 2019).

- Dițoiu, Nina Cristina., Ph. D. Thesis – Summary "The regenerative culture of the built environment: Multicriteria decisions in the double-way spiral", 2023.

- Diţoiu, Nina Cristina., Mihaela Ioana Maria Agachi, Mugur Balan, Newness touches conventional history: the research of the photovoltaic technology on a wooden church heritage building (WMCAUS 2020 IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering 960 (2020) 022055 IOP Publishing Part of ISSN: 1757-899X).

- Droege, Peter., ed., URBAN ENERGY TRANSITION Renewable Strategies for Cities and Regions (Elsevier, 2018).

- El Hafidi, El Mokhtar., El Ghaouti Chahid, Abdelhadi Mortadi, Said Laasri, Study on a new solar-powered desalination system to alleviate water scarcity using impedance spectroscopy (MaterialsToday: PROCEEDING, March 2024).

- Ferreira, Carla S.S., Milica Kašanin-Grubin, Marijana Kapović Solomun, Svetlana Sushkova, Tatiana Minkina,.

- Wenwu Zhao, Zahra Kalantari, Wetlands as nature-based solutions for water management in different environments (Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health Volume 33, June 2023, 100476).

- Gheorghiu, Cristian., Mircea Scripcariu, Gabriela Sava, Miruna Gheorghiu, Alexandra Lidia Dina, Agrivoltaics potential in Romania – A symbiosis between agriculture and energy (EMERG, Volume VIII, Issue 3/2022 ISSN 2668-7003, ISSN-L 2457-5011). [CrossRef]

- Ghinoiu, Ion., (coordonator general) Habitatul. Răspunsuri la chestionarele Atlasului Etnografic Român (Volumul II Banat, Crișana, Maramureș, ISBN 978-973-8920-21-7 Ed. Etnologică, București, 2010). (Volumul III Transilvania, ISBN 978-973-8920-31-6, Ed. Etnologică București, 2011). (Volumul IV Moldova, ISBN 978-973-8920-23-1 Ed. Etnologică, București, 2017).

- Hawken, Paul., Regeneration: Ending the Climate Crisis in One Generation (Penguin Books: UK, 2021).

- Heidegger, Martin., The Question Concerning Technique (Basic Writings: Martin Heidegger, Ed. David Farrell Krell, New York: Harper Collins, 1993).

- Heidegger, Martin., Întrebarea privitoare la tehnică, in: Originea operei de artă, translated by Gabriel Liiceanu after: Die Frage nach der Technik (Vortrage und Aufsatze, Teil I, Neske, Pfullingen, 1967), (reprint, Bucharest: Humanitas, 2011).

- Honeck, Erica., Arthur Sanguet, Martin A. Schlaepfer, Nicolas Wyler, Anthony Lehmann, Methods for identifying green infrastructure (SN - Published online: 28 October 2020).

- Kindel, Peter J. Biomorphic Urbanism: A Guide for Sustainable Cities (Why ecology should be the fondationa of urban development: Medium SOM, Apr 2019).

- Kumar N.M.,; K. Sudhakar,; M. Samykano, Techno-economic analysis of 1 MWp grid connected solar PV plant in Malaysia (International Journal of Ambient Energy: Vol. 40, No. 4, 2019).

- Laasri, Said., El Mokhtar El Hafidi, Abdelhadi Mortadi, El Ghaouti Chahid, Solar-powered single-stage distillation and complex conductivity analysis for sustainable domestic wastewater treatment (Environmental Science and Pollution Research: Volume 31, April 2024).

- Laub, Moritz., Lisa Pataczek, Arndt Feuerbacher, Sabine Zikeli, Petra Högy, Contrasting yield responses at varying levels of shade suggest different suitability of crops for dual land-use systems: a meta-analysis (Agronomy for Sustainable Development: Volume 42, June 2022).

- Leach, Neil., Uitati-l pe Heidegger/Forget Heidegger (bilingv, Ed. Paideia, Bucuresti, Romania, 2006).

- Lin, David., Laurel Hanscom, Adeline C Murthy, Alessandro Galli, Mikel Cody Evans, Evan Neill, Maria Serena Mancini and others, Ecological Footprin Accounting for Countries: Updates and Results of the National Footprint Accounts, 2012-2018 (MPDI Resources, 2018). [CrossRef]

- Mortadi, A.; E. El Hafidi,; H. Nasrellah,; M. Monkade,; R. El Moznine, Analysis and optimisation of lead-free perovskite solar cells: investigating performance and electrical characteristics (Materials for Renewable and Sustainable Energy: 2024).

- Ong, S.; C. Campbell,; P. Denholm,; R. Margolis,; G. Health, Land-Use Requirements for Solar Power Plant in the United States (National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Technical Report NREL/TP-6A20-56290, June 2013).

- Sagmeister, Stefan, Jesssica Walsh, Sagmeister & Walsh – Beauty (Book: Phaidon Press Ltd, London, 2018).

- Saunders, Paul J. Land Use Requirements of Solar and Wind Power Generation: Understanding a Decade of Academic Research (Publisher: Energy Innovation Reform Project, Nov. 2020).

- Scripcaru, Gheorghe., Boroaia O reintoarcere in spirit (Monografie reeditată comuna Boroaia, 2013).

- Seamon, David., Place, Place Identity, and phenomenology: a triadic Interpretation based on J.G. Bennett’s Systematics (The Role of Place Identity in Perception, Understanding, and Design of Built Environments, Editors: Hernan Casakin and Fatima Bernardo, Bentham Science Publishers, 2012).

- Tapia, Carlos., Marco Bianchi, Mirari Zaldua, Marion Courtois, Philippe Micheaux Naudet, Andrea Bassi, Philippe Micheaux Naudet and others, CIRCTER - Circular Economy and Territorial Consequences (ESPON: Applied Research, Final Report, 2019).

- Widmer J.; Christ B.; Grenz J.; Norgrove L.; Agrivoltaics, a promising new tool for electricity and food production: A systematic review, (Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews: March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Weisauer, Caro., 100 Questions about Hundertwasser (100 X Hundertwasser. Artist-Visionary-Nonconformist, METROVERLAG: 2016).

- Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE, Agrivoltaics: Opportunities for Agriculture and the Energy Transition (A Guideline for Germany: February 2024).

- VERS UN CADASTRE SOLAIRE 2.0, note no. 148, april 2019, APUR (atelier parisien d’urbanisme) Directrice de la publication: ALBA, Dominique, Note réalisée par: Gabriel SENEGAS, Sous la direction de : Olivier RICHARD, Cartographie et traitement statistique: Apur, www.apur.org.

- Vallée de la Seine, enjeux & perspectives, Dynamiques agricoles et alimentaires, Coopération des agences d’urbanisme APUR, AUCAME, AURBSE, AURH, L’INSTITUTE, Vallée de la Seine, contrat de plan inter- régional État-Régions Vallée de la Seine, 2021.

- Romanian Government: The 2021-2030 Integrated National Energy and Climate Plan (April 2020),.

- Integrated National Energy and Climate Plan of ROMANIA (2021-2030 Update).

- Gouvernement de France, Ordre de méthode: Instruction technique DGPE/SDPE/2025-93 (Objet: Application des dispositions réglementaires relatives aux installations agrivoltaïques et photovoltaïques au sol dans les espaces naturels, agricoles et forestiers).

| 1 | John G. Bennett, Elementary systematics: A Tool for Understanding Wholes (Bennett Books, the Estate of J.G. Bennett, United States of America, 1993), 27. |

| 2 | Carla S. S. Ferreira, Milica Kašanin-Grubin, Marijana Kapović Solomun, Svetlana Sushkova, Tatiana Minkina, Wenwu Zhao and Zahra Kalantari, Wetlands as nature-based solutions for water management in different environments (Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health: Volume 33, June 2023, 100476), 6. "Wetlands have emerged as NBS in various water resources management practices, including regulating the hydrological cycle and improving water quality. However, natural wetlands worldwide continue to be threatened by anthropogenic and climate drivers" https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2468584423000363 (visited: april 2025). |

| 3 | Caro Weisauer, 100 Questions about Hundertwasser (100 X Hundertwasser. Artist-Visionary-Nonconformist, METROVERLAG: 2016, ISBN 978-3-99300-261-9), 31, 35. "Hundertwasser was convinced that the creation of the earth took place in spiral form”. https://www.kunsthauswien.com/en/education/100-x-hundertwasser/ (visited: april 2025). |

| 4 | Nina Cristina Dițoiu, Ph. D. Thesis – Summary "The regenerative culture of the built environment: Multicriteria decisions in the double-way spiral", 2023. https://doctorat.utcluj.ro/theses/view/OZxZ2SPxgn5edlY60K2Gi3FKCdAH5uP4XDqNfXmH.pdf (visited: april 2025). |

| 5 | John G. Bennett, Elementary systematics: A Tool for Understanding Wholes (Bennett Books, the Estate of J.G. Bennett, United States of America, 1993), 9. |

| 6 | Nina Cristina Dițoiu, Ph. D. Thesis – Summary "The regenerative culture of the built environment: Multicriteria decisions in the double-way spiral", 2023. |

| 7 | ibidem, Diţoiu, N.C.’s concept, Sketch & cad drawing. |

| 8 | John G. Bennett, Elementary systematics: A Tool for Understanding Wholes (Bennett Books, the Estate of J.G. Bennett, United States of America, 1993), 8-17. |

| 9 |

https://ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance-taxonomy/home (visited: april 2025). |

| 10 |

https://ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance-taxonomy/home Related to 4 taxonomy criteria: DNSH The protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems; DNSH Climate change mitigation; DNSH Climate change adaptation; DNSH The sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources (visited: april 2025). |

| 11 |

https://ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance-taxonomy/home Related to 3 taxonomy criteria: DNSH Climate change mitigation; DNSH Climate change adaptation; DNSH The transition to a circular economy (visited: april 2025). |

| 12 | Aristide Athanassiadis, https://www.circularmetabolism.com/ (visited: april 2025). |

| 13 |

https://ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance-taxonomy/home Related essential to one taxonomy criteria: DNSH Climate change mitigation (visited: april 2025). |

| 14 | Peter Droege, ed., URBAN ENERGY TRANSITION Renewable Strategies for Cities and Regions (Elsevier, 2018), 31-49, 85-113. |

| 15 |

Aqua Prociv Proiect, Company, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, "Renaturation of Zerind & Tămaşda polders, Arad and Bihor counties” (Romania Team Project: Concept Sketch &cad drawing landcape design - Arch. Nina Cristina Dițoiu; Cad Drawings & Hidrotechnical Design - Eng. Dragoş Gros, Team Coordinator Eng. Dan Săcui). |

| 16 | ran.cimec.ro cimec map Tumular necropolis Daco-Roman period (3rd - 4th century) RAN 147081.01 LMI code (List of Historical Monuments) List of Historical Monuments from 2010, SV-I-s-B-05398 (visited: april 2025). |

| 17 | ran.cimec.ro cimec map |

| 18 | Gheorghe Scripcaru, BOROAIA O reintoarcere in spirit (Monografie reeditată comuna Boroaia ISBN 973-98476-5-X, 2013), 87-88, 90. [tr.n.]“Names of some families (...) C.” Boroaia “hypothesis of transfer from Transylvania”, “Transylvanian words among the village inhabitants (dar-ar, lual-ar, mancai-ar, basna, ciubar, flacau (...) pisti, tongue, house, amu, etc.)” (...) “from a certain Bora and Boroaia’s wife, with whom the peasants emigrated from Transylvania”.

|

| 19 | Ion Ghinoiu, (coordonator general), Habitatul. Răspunsuri la chestionarele Atlasului Etnografic Român (Volumul IV Moldova, ISBN 978-973-8920-23-1 Ed. Etnologică, București, 2017). |

| 20 | Gheorghe Scripcaru, BOROAIA O reintoarcere in spirit (Monografie reeditată comuna Boroaia ISBN 973-98476-5-X, 2013), 39. [tr.n.]"Undoubtedly, the name of the village comes from a man named Bora from Transylvania, with which the population took refuge in this area on the estates of the Rasca and Neamt monasteries after Horia’s uprising, and Bora, which derives from Bor, imposes itself as a purely Romanian word".

|

| 21 | Ion Ghinoiu, (coordonator general), Habitatul. Răspunsuri la chestionarele Atlasului Etnografic Român (Volumul II Banat, Crișana, Maramureș, ISBN 978-973-8920-21-7 Ed. Etnologică, București, 2010), 114. [tr.n.]"In 1480, it is said that Macea had 4800 souls, who mostly disappeared after a plague, about 50 families remained, 150 families left Moldova, near Suceava: Ar 8”.

|

| 22 | Gheorghe Scripcaru, BOROAIA O reintoarcere in spirit (Monografie reeditată comuna Boroaia ISBN 973-98476-5-X, 2013), 25. [tr.n.] "in Drăguşeni, the archaeological excavations of V. Ciurea discovered (...) concludes that Boroaia is also a prehistoric locality (...) and on the terrace of the Tîrziu stream, N. Zaharia also found fragments of bones, anthropic and zoomorphic figurines and a flat stone axe belonging to the developed Neolithic (Cucuteni phase A)”.

|

| 23 | ran.cimec.ro cimec map Tumular necropolis Daco-Roman period (3rd - 4th century) RAN 147081.01 LMI code (List of Historical Monuments) List of Historical Monuments from 2010, SV-I-s-B-05398 (visited: april 2025). |

| 24 | Secuta, Moldavia (1892-1898) map https://maps.arcanum.com/en/map/romania- 1892/?layers=22&bbox=2968946.7689266833%2C6061625.993676056%2C2975910.6244568615%2C6064161.797620838. (visited: april 2025). [tr.n.] "The groundwater is at a depth of 6-18 m, and in some places, it reaches 30 m. (...) The Moldova River has an unstable riverbed and often causes floods. Also, on the commune’s territory, the Risca stream is confluent with the Moldova River, which increases the risk of these floods. The hydrographic network is formed by the Moişa and Săcuţa streams that flow into Saca, the latter into the Risca River and Risca into the Moldova River. When it rains, the flow of these streams is very high, and when there is drought, the streams dry up completely (hence the name) due to the bed formed by very permeable rocks".

|

| 25 | Ion Ghinoiu, (coordonator general), Habitatul. Răspunsuri la chestionarele Atlasului Etnografic Român (Volumul IV Moldova, ISBN 978-973-8920-23-1 Ed. Etnologică, București, 2017). |

| 26 |

https://dragusanul.ro/povestea-asezarilor-sucevene-boroaia/ (visited: april 2025). [tr.n.]"Although the uric of August 4, 1400, by which Alexander the Good (...) «A village, of Berea» appeared, not only through name to Boroaia (...) 1796: (...) When it is concluded that the Saca Valley (Sacuta location) (...) located between Bogdăneși and Boroaia (at that time - the proof that the current hearth of Boroaia is later), (...) commands them to move to these estates in Saca Valley”. |

| 27 |

https://www.comunaboroaia.ro/muzeul-neculai-cercel/ (visited: april 2025). |

| 28 |

http://boroaia.uv.ro/5.htm (visited: april 2025). [tr.n.]"inhabitants of Boroaia village came from Transylvania between 1742 and 1774, which constitute two certain historical references; One (1742) that does not include the Boroaia among the estates of the monasteries Râzca, Neamt and Secu, another that includes (1774) as the estates of these three monasteries, when their captain, Bora, dying, remained the woman of Boroaia (Bora’s feminine)”.

|

| 29 |

https://dragusanul.ro/povestea-asezarilor-sucevene-boroaia/ (visited: april 2025). [tr.n.] "1899: It is published towards the general knowledge that, on November 18, 1899, 11 hours, will be held, in the premises of the City Hall of the respective communes on which each of the goods noted below, oral public auction for leasing the lands, of hay and of the mountain hollows for the pasture, by their land, Boroaia: (...) C. Family name (7 ha, 8000 sqm)".

|

| 30 | Ion Ghinoiu, (coordonator general), Habitatul. Răspunsuri la chestionarele Atlasului Etnografic Român (Volumul IV Moldova, ISBN 978-973-8920-23-1 Ed. Etnologică, București, 2017), 39, 140, 143-144, 451-454. |

| 31 | Martin Brown, FutuRestorative: Working Towards a New Sustainability (RIBA Publishing, 2016) https://fairsnape.com/2016/03/23/futurestorative-working-towards-a-new-sustainability/ (visited: april 2025). |

| 32 |

https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/landcoverexplorer/ (visited: april 2025). |

| 33 |

https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/ (visited: april 2025). |

| 34 |

https://geoportal.ancpi.ro/imobile.html (visited: april 2025). |

| 35 |

Aqua Prociv Proiect, Company, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, "Renaturation of Zerind & Tămaşda polders, Arad and Bihor counties” (Romania Team Project: Architecture Concept Sketch - Arch. Nina Cristina Dițoiu; Cad Drawings & Hidrotechnical Design - Eng. Dragoş Gros, Coordinator Eng. Dan Săcui). |

| 36 |

https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/landcoverexplorer/ (visited: april 2025). |

| 37 |

https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/ (visited: april 2025). |

| 38 | Ion Ghinoiu, (coordonator general), Habitatul. Răspunsuri la chestionarele Atlasului Etnografic Român (Volumul II Banat, Crișana, Maramureș, ISBN 978-973-8920-21-7 Ed. Etnologică, București, 2010), (Volumul III Transilvania, ISBN 978-973-8920-31-6, Ed. Etnologică București, 2011). |

| 39 | ibidem. |

| 40 |

https://www.wkcgroup.com/tools-room/carbon-sequestration-calculator/ (visited: april 2025). |

| 41 |

https://www.biodiversity-metrics.org/understanding-biodiversity-metrics.html (visited: april 2025). |

| 42 |

https://www.grestool.org/ (visited: april 2025). |

| 43 |

Aqua Prociv Proiect, Company, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, "Renaturation of Zerind & Tămaşda polders, Arad and Bihor counties” (Romania Team Project: Architecture Concept Sketch - Arch. Nina Cristina Dițoiu; Cad Drawings & Hidrotechnical Design - Eng. Dragoş Gros, Coordinator Eng. Dan Săcui). |

| 44 | Paul Hawken, Regeneration: Ending the Climate Crisis in One Generation (Penguin Books: UK, 2021), 198-201, 212-213. |

| 45 | ibidem, 210-211. |

| 46 | Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE, Agrivoltaics: Opportunities for Agriculture and the Energy Transition (A Guideline for Germany: February 2024). https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/en/publications/studies/agrivoltaics-opportunities-for-agriculture-and-the-energy-transition.html (visited: april 2025). |

| 47 | Said Laasri, El Mokhtar El Hafidi, Abdelhadi Mortadi & El Ghaouti Chahid, Solar-powered single-stage distillation and complex conductivity analysis for sustainable domestic wastewater treatment (Environmental Science and Pollution Research: Volume 31, April 2024, pages 29321–29333). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11356-024-33134-y (visited: april 2025). |

| 48 | El Mokhtar El Hafidi, El Ghaouti Chahid, Abdelhadi Mortadi, Said Laasri, Study on a new solar-powered desalination system to alleviate water scarcity using impedance spectroscopy (MaterialsToday: PROCEEDING; March 2024). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2214785324001019?via%3Dihub (visited: april 2025). |

| 49 | N.M. Kumar,; K. Sudhakar,; M. Samykano, Techno-economic analysis of 1 MWp grid connected solar PV plant in Malaysia (International Journal of Ambient Energy: Vol. 40, No. 4, 2019), 434-443. DOI: 10.1080/01430750.2017.1410226 (visited: april 2025). |

| 50 | Paul J. Saunders, Land Use Requirements of Solar and Wind Power Generation: Understanding a Decade of Academic Research (Publisher: Energy Innovation Reform Project, Nov. 2020). |

| 51 | S. Ong,; C. Campbell,; P. Denholm,; R. Margolis,; G. Health, Land-Use Requirements for Solar Power Plant in the United States (National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Technical Report NREL/TP-6A20-56290, June 2013). |

| 52 | A. Mortadi,; E. El Hafidi,; H. Nasrellah,; M. Monkade,; R. El Moznine, Analysis and optimization of lead-free perovskite solar cells: investigating performance and electrical characteristics (Materials for Renewable and Sustainable Energy: Volume 13, April 2024), 219-232. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40243-024-00260-z (visited: april 2025). |

| 53 | Paul Denholm, Mohammed Hand, Maddalena Jackson, Sini Ong, Land-Use Requirements of Modern Wind Power Plants in the United States (National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Technical Report:NREL/TP-6A2-45834, August 2009). https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy09osti/45834.pdf (visited: april 2025). |

| 54 | Widmer J.; Christ B.; Grenz J.; Norgrove L.; Agrivoltaics, a promising new tool for electricity and food production: A systematic review, (Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews: March 2024). https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2024RSERv.19214277W/abstract (visited: april 2025). |

| 55 | Dr Paweł Czyżak & Tatiana Mindeková, EMBER Empowering farmers in Central Europe: the case for agri-PV Unlocking the vast potential of agri-PV brings benefits for farmers and energy systems in Central European countries (Published date: 29.08.2024, Published under a Creative Commons ShareAlike Attribution Licence <CC BY-SA 4.0>). https://ember-energy.org/latest-insights/empowering-farmers-in-central-europe-the-case-for-agri-pv/ (visited: april 2025). |

| 56 | Moritz Laub, Lisa Pataczek, Arndt Feuerbacher, Sabine Zikeli, Petra Högy, Contrasting yield responses at varying levels of shade suggest different suitability of crops for dual land-use systems: a meta-analysis (Agronomy for Sustainable Development: Volume 42, June 2022). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13593-022-00783-7 (visited: april 2025). |

| 57 |

https://iiw.kuleuven.be/apps/agrivoltaics/tool.html (visited: april 2025). |

| 58 |

https://github.com/PyPSA/atlite (visited: april 2025). |

| 59 | Cristian Gheorghiu, Mircea Scripcariu, Gabriela Sava, Miruna Gheorghiu, Alexandra Lidia Dina, Agrivoltaics potential in Romania–A symbiosis between agriculture and energy (EMERG, Volume VIII, Issue 3/2022 ISSN 2668-7003, ISSN-L 2457-5011). https://emerg.ro/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/9-AGRIVOLTAICS-POTENTIAL-IN-ROMANIA-–-A-SYMBIOSIS-BETWEEN-AGRICULTURE-AND-ENERGY.pdf (visited: april 2025). |

| 60 | Integrated National Energy and Climate Plan of ROMANIA, (2021-2030 Update, First draft version). https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2023-11/ROMANIA%20-%20DRAFT%20UPDATED%20NECP%202021-2030.pdf (visited: april 2025). |

| 61 | Gouvernement de France: Ordre de méthode, Bulletin official: Instruction technique DGPE/SDPE/2025-93 (Objet: Application des dispositions réglementaires relatives aux installations agrivoltaïques et photovoltaïques au sol dans les espaces naturels, agricoles et forestiers). https://info.agriculture.gouv.fr/boagri/instruction-2025-93 (visited: april 2025). |

| 62 | PHOTOVOLTAIC GEOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION SYSTEM. https://re.jrc.ec.europa.eu/pvg_tools/en/ (visited: april 2025). |

| 63 | Dițoiu Nina Cristina’s concept sketch, coordinator Aqua Prociv Proiect team Eng. Dan Săcui. "Renaturation of Zerind polder, Arad county” & ” Renaturation of Tămaşda polder, Bihor county” |

| 64 | Paul Hawken, Regeneration: Ending the Climate Crisis in One Generation (Penguin Books: UK, 2021), 84-85, 88-89, 96-99, 198-201, 210-213. |

| 65 | David Lin, Laurel Hanscom, Adeline C Murthy, Alessandro Galli, Mikel Cody Evans, Evan Neill, Maria Serena Mancini and others, Ecological Footprin Accounting for Countries: Updates and Results of the National Footprint Accounts, 2012-2018 (MPDI Resources: September 2018, 7(3):1-22, License CC BY 4.0). |

| 66 | CADASTRE SOLAIRE 2.0, note no. 148, april 2019, APUR (atelier parisien d’urbanisme) Directrice de la publication: ALBA, Dominique, Note réalisée par: Gabriel SENEGAS, Sous la direction de : Olivier RICHARD, Cartographie et traitement statistique: Apur, www.apur.org. https://www.apur.org/fr/nos-travaux/vers-un-cadastre-solaire-2-0 (visited: april 2025). |

| 67 | Peter J. Kindel, Biomorphic Urbanism: A Guide for Sustainable Cities (Why ecology should be the fondationa of urban development: Medium SOM, Apr 2019). https://som.medium.com/biomorphic-urbanism-a-guide-for-sustainable-cities-4a1da72ad656 (visited: april 2025). |

| 68 | Aristide Athanassiadis, https://www.circularmetabolism.com/ (visited: april 2025) |

| 69 | Carlos Tapia, Marco Bianchi, Mirari Zaldua, Marion Courtois, Philippe Micheaux Naudet, Andrea Bassi, Philippe Micheaux Naudet and others, CIRCTER - Circular Economy and Territorial Consequences (ESPON: Applied Research, Final Report, 09.05.2019), 7. https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/sites/default/files/circter_fr_main_report.pdf (visited: april 2025). |

| 70 | similar to Apur document about Seine Valley-Agricultural and food dynamics: Vallee de la Seine, enjeux & perspectives, Dynamiques agricoles et alimentaires, Coopération des agences d’urbanisme APUR, AUCAME, AURBSE, AURH, L’INSTITUTE, Vallée de la Seine, contrat de plan inter-régional État-Régions Vallée de la Seine, 2021. |

| 71 | |

| 72 | Christopher Alexander, The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe-The Phenomenon of Life (Center for Enviromental Structure, Berkeley, California, 2014, first ed. 1980), 15. |

| 73 | Carolin Bellstedt, Gerardo Ezequiel Martín Carreño, Aristide Athanassiadis, Shamita Chaudhry, METABOLISM of CITIES (CityLoops-D4.4–Urban Circularity Assessment Method, Version 1.0 <2022-05-31>), 35. https://cityloops.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Materials/UCA/CityLoops_WP4_D4.4_Urban_Circularity_Assessment_Method_Metabolism_of_Cities.pdf (visited: april 2025). |

| 74 |

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:World_map_of_countries_by_ecological_deficit_(2013).svg (visited: april 2025). |

| 75 | Erica Honeck, Arthur Sanguet, Martin A. Schlaepfer, Nicolas Wyler, Anthony Lehmann, Methods for identifying green infrastructure (SN: Applied science 2020). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42452-020-03575-4 (visited: april 2025). |

| 76 |

https://www.turbulent.be/projects (visited: april 2025). |

| 77 | |

| 78 | Peter Droege, ed., URBAN ENERGY TRANSITION Renewable Strategies for Cities and Regions (Elsevier, 2018), 31-49, 85-113. |

| 79 | Erica Honeck, Arthur Sanguet, Martin A. Schlaepfer, Nicolas Wyler, Anthony Lehmann, Methods for identifying green infrastructure (SN: Applied science 2020). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42452-020-03575-4 (visited: april 2025). |

| 80 | Stefan Sagmeister, Jesssica Walsh, Sagmeister & Walsh – Beauty (Book: Phaidon Press Ltd, ISBN 9780714877273, Nov 2018, London), 269. |

| 81 | David Seamon, Place, Place Identity, and phenomenology: a triadic Interpretation based on J.G. Bennett’s Systematics (The Role of Place Identity in Perception, Understanding, and Design of Built Environments, Editors: Hernan Casakin and Fatima Bernardo, Bentham Science Publishers, 2012). |

| 82 | Dilip da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers: Alexander’s Eye and Ganga’s Descent (Publisher: University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, Feb 2019) (chapter Waters of Eden), 123-136. (describes four rivers sourced in paradisep), 126. (the city manipulates only the earth surfacep), 155, 273-294. (After rivers (...) extreme hydraulic engeneering), 290. |

| 83 | Martin Heidegger, Întrebarea privitoare la tehnică, in: Originea operei de artă, translated by Gabriel Liiceanu after: Die Frage nach der Technik (Vortrage und Aufsatze, Teil I, Neske, Pfullingen, 1967), 120-169. (reprint, Bucharest: Humanitas, 2011), 134. |

| 84 | Martin Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology (Basic Writings: Martin Heidegger, Ed. David Farrell Krell, New York: Harper Collins, 1993), 311-341. |

| 85 | Neil Leach, Uitati-l pe Heidegger/Forget Heidegger (bilingv, Ed. Paideia, Bucuresti, Romania, 2006, translated by Magda Teodorescu, Dana Vais), 33-34, 66. |

| 86 | Stefan Sagmeister, Jesssica Walsh, Sagmeister & Walsh - Beauty (Book: Phaidon Press Ltd, ISBN 9780714877273, Nov 2018, London), 25. |

| 87 | David Seamon, Place, Place Identity, and phenomenology: a triadic Interpretation based on J.G. Bennett’s Systematics (The Role of Place Identity in Perception, Understanding, and Design of Built Environments, Editors: Hernan Casakin and Fatima Bernardo, Bentham Science Publishers, 2012). |

| PRODUCTION44 | CONSUMPTION - STORAGE45 |

|---|---|

|

|

| |

| Scenario | NPV (EURO) |

IRR (%/year) |

SPP (years) |

BCA (-) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAU | 23,327 | 37 | 4.38 | 1.25 |

| Interspaced APV | 1,914,339 | 17 | 8.38 | 1.22 |

| Overhead APV | 4,632,501 | 17 | 8.20 | 1.26 |

| Conventional PVP | 18,287,612 | 23 | 6.12 | 1.86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).