Submitted:

05 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Case Description and Discussion

2.1. Anamnesis

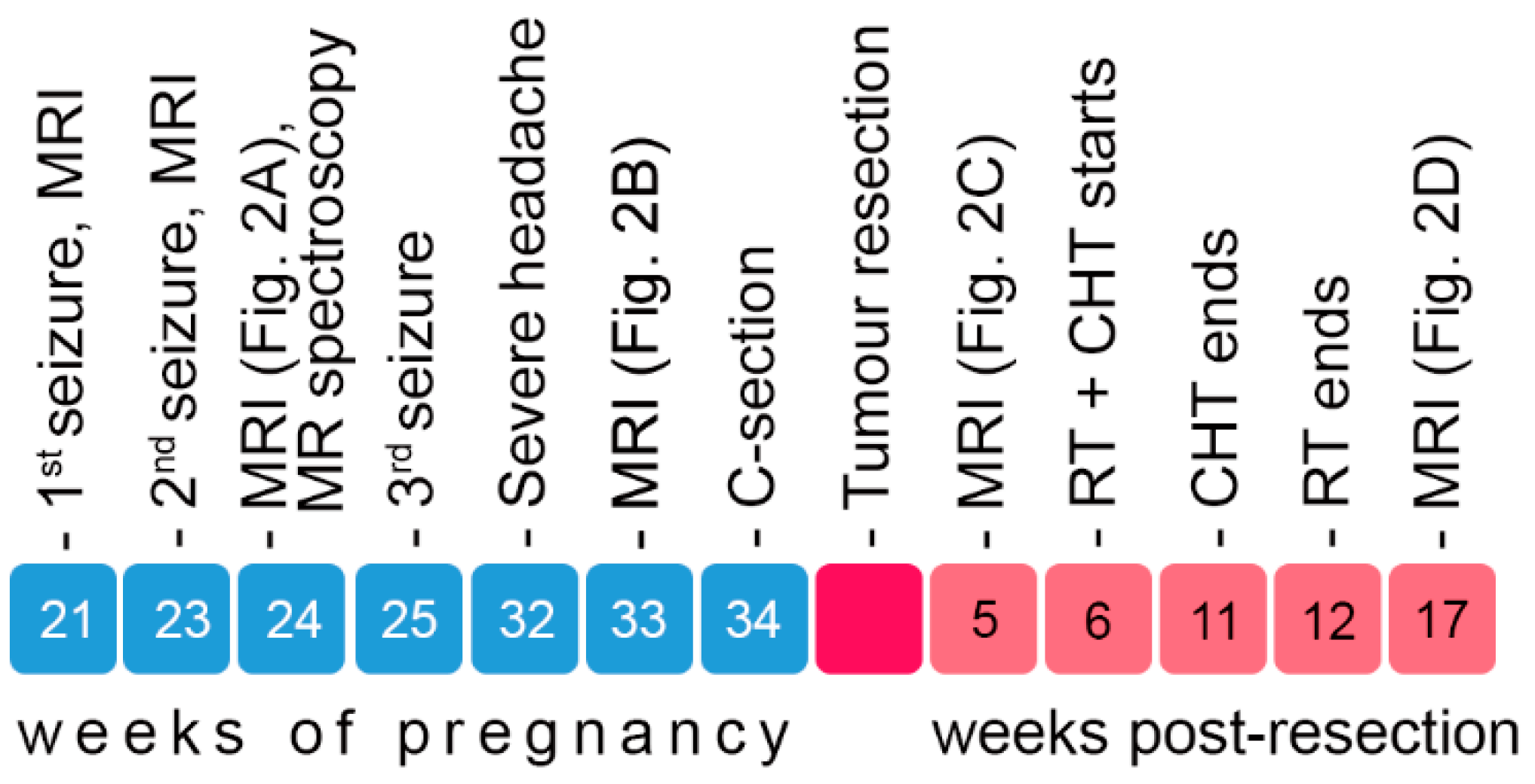

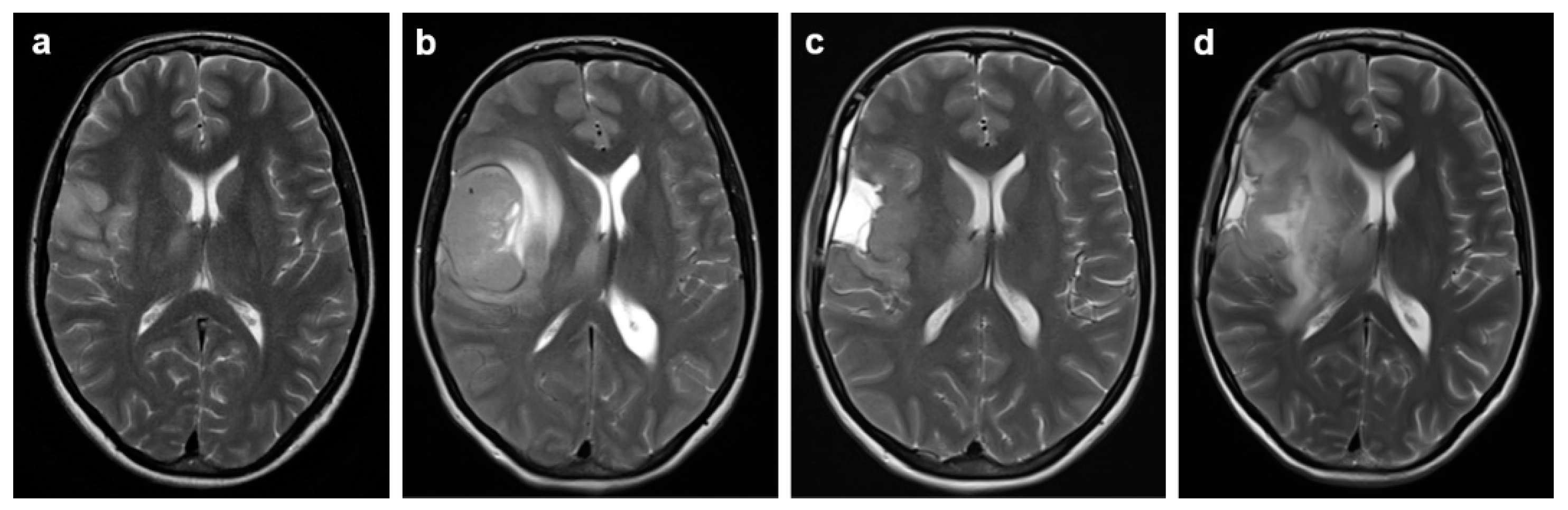

2.2. Symptom Development, Imaging and Surgical Intervention

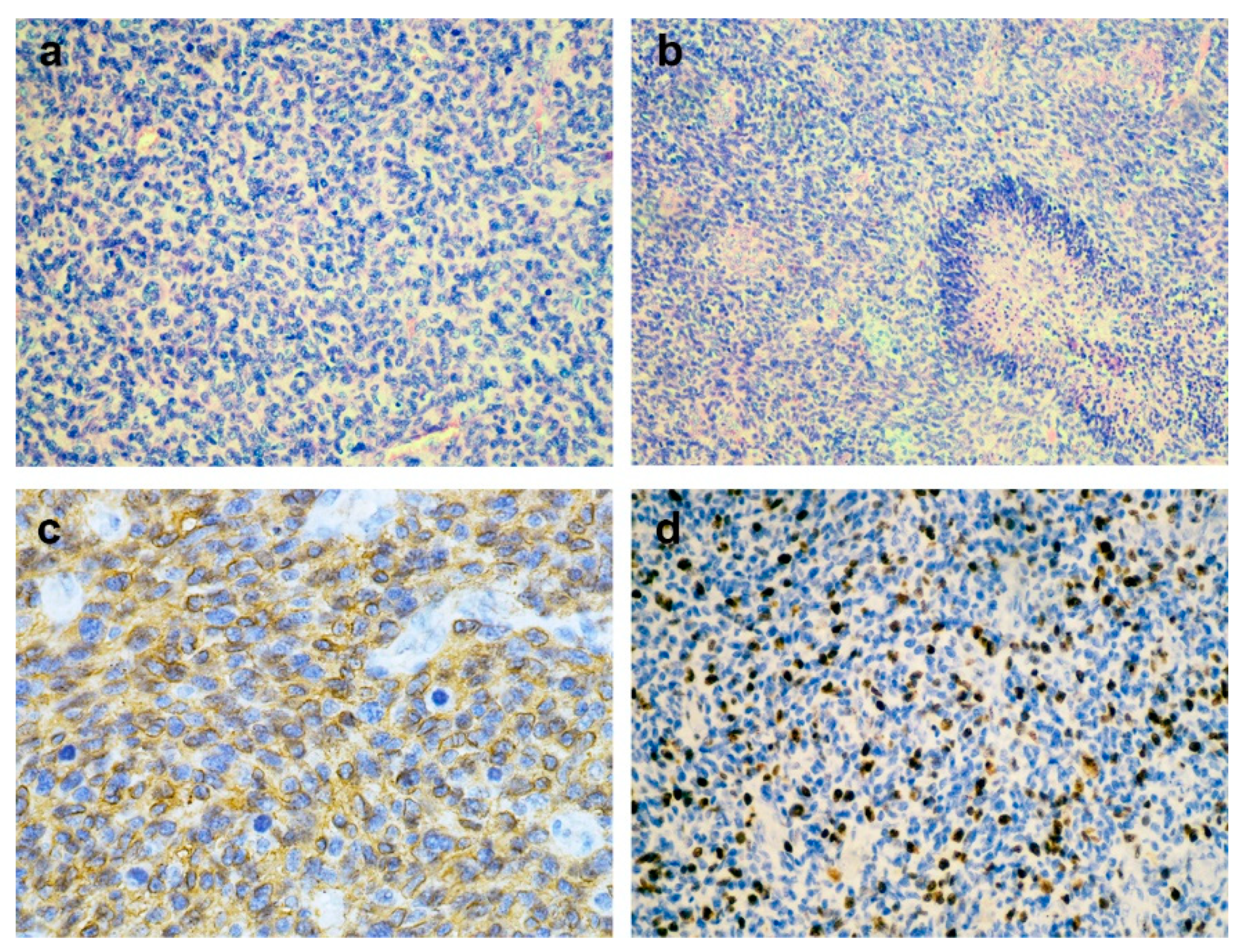

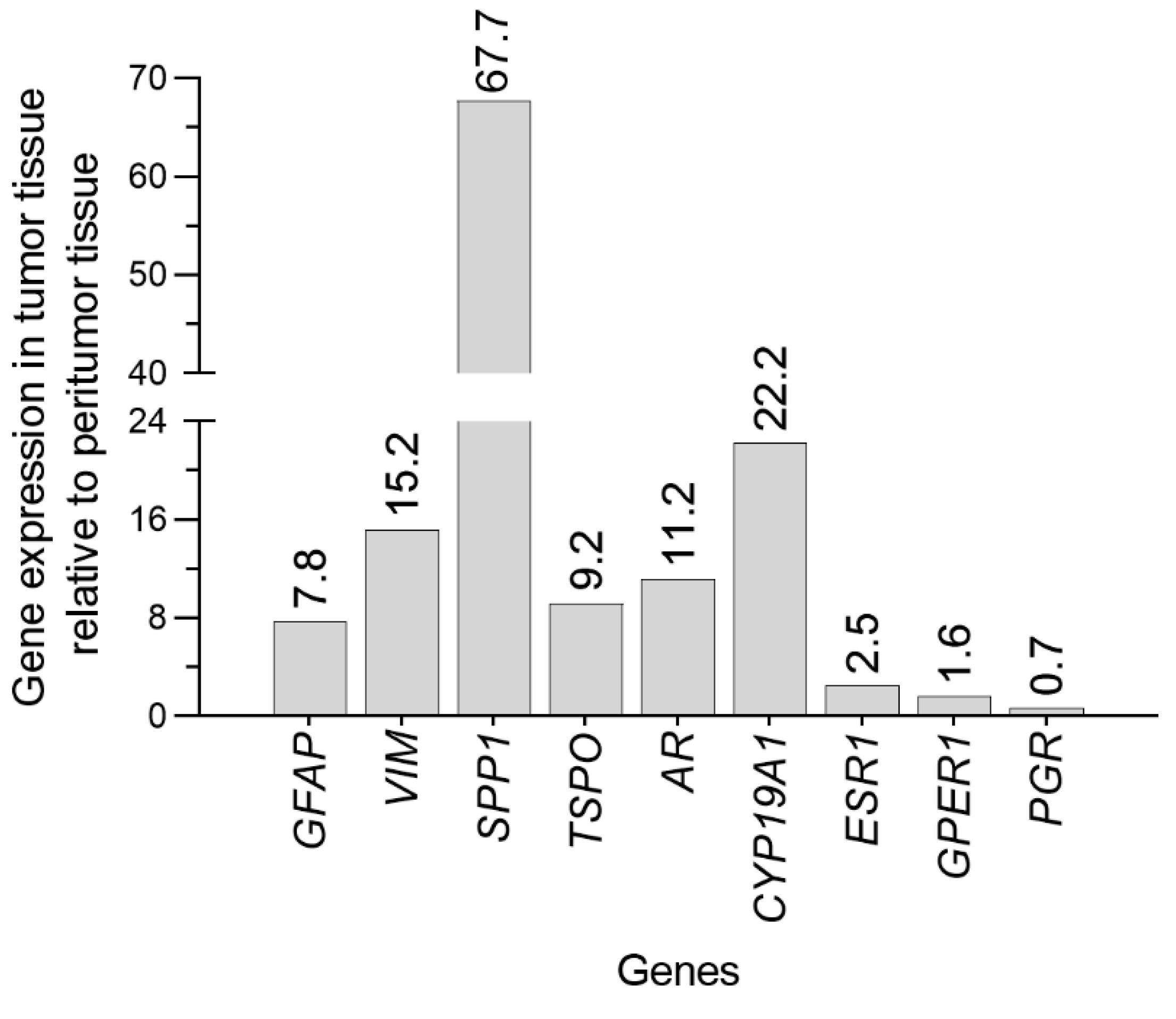

2.3. Pathology and Molecular Analysis

2.3. Postoperative Course

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AR | Androgen receptor |

| ATRX | Alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation, X-linked |

| CHT | Chemotherapy |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CYP19A1 | Aromatase |

| ESR1 | Estrogen receptor α |

| FLAIR | Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery |

| GB | Glioblastoma |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| GPER | G protein-coupled estrogen receptor |

| IDH | Isocitrate dehydrogenase |

| IVF | In vitro fertilization |

| Ki-67 | Marker of proliferation Kiel 67 |

| MAP2 | Microtubule-associated protein 2 |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| Olig2 | Oligodendrocyte lineage transcription factor 2 |

| p53 | Tumor protein p53 |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PGR | Progesterone receptor |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| SSP1 | Osteopontin |

| TSPO | Translocator protein |

| VIM | Vimentin |

| H3K27me3 | Histone 3 Lys 27 trimethylation |

| CDKN2A | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A |

References

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Price, M.; Neff, C.; Cioffi, G.; Waite, K.A.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2016-2020. Neuro-oncology 2023, 25(12) Suppl 2, iv1–iv99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, A.F.; Juweid, M. Epidemiology and Outcome of Glioblastoma. In Glioblastoma [Internet]; De Vleeschouwer, S., Ed.; Codon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2017; pp. 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; Curschmann, J.; Janzer, R.C.; Ludwin, S.K.; Gorlia, T.; Allgeier, A.; Lacombe, D.; Cairncross, J.G.; Eisenhauer, E.; Mirimanoff, R.O. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. The New England journal of medicine 2005, 352, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Mantilla, E.; Sewell, J.; Hatanpaa, K.J.; Pan, E. Occurrence of Glioma in Pregnant Patients: An Institutional Case Series and Review of the Literature. Anticancer research 2020, 40, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelvink, N.C.A.; Kamphorst, W.; van Alphen, H.A.M.; Rao, B.R. Pregnancy-Related Primary Brain and Spinal Tumors. Archives of Neurology 1987, 44, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallud, J.; Duffau, H.; Razak, R.A.; Barbarino-Monnier, P.; Capelle, L.; Fontaine, D.; Frenay, M.; Guillet-May, F.; Mandonnet, E.; Taillandier, L. Influence of pregnancy in the behavior of diffuse gliomas: clinical cases of a French glioma study group. Journal of neurology 2009, 256, 2014–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peeters, S.; Pagès, M.; Gauchotte, G.; Miquel, C.; Cartalat-Carel, S.; Guillamo, J.S.; Capelle, L.; Delattre, J.Y.; Beauchesne, P.; Debouverie, M.; Fontaine, D.; Jouanneau, E.; Stecken, J.; Menei, P.; De Witte, O.; Colin, P.; Frappaz, D.; Lesimple, T.; Bauchet, L.; Lopes, M.; Bozec, L.; Moyal, E.; Deroulers, C.; Varlet, P.; Zanello, M.; Chretien, F.; Oppenheim, C.; Duffau, H.; Taillandier, L.; Pallud, J. Interactions between glioma and pregnancy: insight from a 52-case multicenter series. Journal of neurosurgery 2018, 128, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yust-Katz, S.; de Groot, J.F.; Liu, D.; Wu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Anderson, M.D.; Conrad, C.A.; Milbourne, A.; Gilbert, M.R.; Armstrong, T.S. Pregnancy and glial brain tumors. Neuro-oncology 2014, 16, 1289–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallud, J.; Mandonnet, E.; Deroulers, C.; Fontaine, D.; Badoual, M.; Capelle, L.; Guillet-May, F.; Page, P.; Peruzzi, P.; Jouanneau, E.; Frenay, M.; Cartalat-Carel, S.; Duffau, H.; Taillandier, L. Pregnancy increases the growth rates of World Health Organization grade II gliomas. Annals of neurology 2010, 67, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, D.T.; Parreño, M.G.; Batten, J.; Chamberlain, M.C. Management of malignant gliomas during pregnancy: a case series. Cancer 2008, 113, 3349–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Botello, D.; Rodríguez-Sanchez, J.R.; Cuevas-García, J.; Cárdenas-Almaraz, B.V.; Morales-Acevedo, A.; Mejía-Pérez, S.I.; Ochoa-Martinez, E. Pregnancy and brain tumors; a systematic review of the literature. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia 2021, 86, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Meador, K.J. Epilepsy and Pregnancy. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.) 2022, 28, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, B.; Forinash, A.B.; Murphy, J.A. Levetiracetam use in pregnancy. The Annals of pharmacotherapy 2009, 43, 1692–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadetzki, S.; Chetrit, A.; Freedman, L.; Stovall, M.; Modan, B.; Novikov, I. Long-term follow-up for brain tumor development after childhood exposure to ionizing radiation for tinea capitis. Radiation research 2005, 163, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauptmann, M.; Byrnes, G.; Cardis, E.; Bernier, M.O.; Blettner, M.; Dabin, J.; Engels, H.; Istad, T.S.; Johansen, C.; Kaijser, M.; Kjaerheim, K.; Journy, N.; Meulepas, J.M.; Moissonnier, M.; Ronckers, C.; Thierry-Chef, I.; Le Cornet, L.; Jahnen, A.; Pokora, R.; Bosch de Basea, M.; Figuerola, J.; Maccia, C.; Nordenskjold, A.; Harbron, R.W.; Lee, C.; Simon, S.L.; Berrington de Gonzalez, A.; Schüz, J.; Kesminiene, A. Brain cancer after radiation exposure from CT examinations of children and young adults: results from the EPI-CT cohort study. The Lancet. Oncology 2023, 24, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, K.S.; Cappuccini, F.; Asrat, T.; Flamm, B.L.; Carpenter, S.E.; Disaia, P.J.; Quilligan, E.J. Obstetric emergencies precipitated by malignant brain tumors. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2000, 182, 1215–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vougioukas, V.I.; Kyroussis, G.; Gläsker, S.; Tatagiba, M.; Scheufler, K.M. Neurosurgical interventions during pregnancy and the puerperium: clinical considerations and management. Acta neurochirurgica 2004, 146, 1287–1291; discussion 1291–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zottel, A.; Jovčevska, I.; Šamec, N.; Komel, R. Cytoskeletal proteins as glioblastoma biomarkers and targets for therapy: A systematic review. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2021, 160, 103283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalli, O.; Wilhelmsson, U.; Örndahl, C.; Fekete, B.; Malmgren, K.; Rydenhag, B.; Pekny, M. Astrocytoma grade IV (glioblastoma multiforme) displays 3 subtypes with unique expression profiles of intermediate filament proteins. Human Pathology 2013, 44, 2081–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicki, M.O.; Hayes, J.L.; Chiocca, E.A.; Lawler, S.E. Proteomic Analysis Implicates Vimentin in Glioblastoma Cell Migration. Cancers 2019, 11, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wang, G.; Ming, J.; Meng, X.; Han, B.; Sun, B.; Cai, J.; Jiang, C. Analysis of expression and prognostic significance of vimentin and the response to temozolomide in glioma patients. Tumor Biology 2016, 37, 15333–15339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.-Y.; Yeh, W.-L.; Huang, S.-M.; Tang, C.-H.; Lin, H.-Y.; Chou, S.-J. Osteopontin increases heme oxygenase–1 expression and subsequently induces cell migration and invasion in glioma cells. Neuro-oncology 2012, 14, 1367–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietras, A.; Katz, A.M.; Ekström, E.J.; Wee, B.; Halliday, J.J.; Pitter, K. L.; Werbeck, J.L.; Amankulor, N.M.; Huse, J.T.; Holland, E.C. Osteopontin-CD44 Signaling in the Glioma Perivascular Niche Enhances Cancer Stem Cell Phenotypes and Promotes Aggressive Tumor Growth. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Marisetty, A.; Schrand, B.; Gabrusiewicz, K.; Hashimoto, Y.; Ott, M.; Grami, Z.; Kong, L.Y.; Ling, X.; Caruso, H.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Y.A.; Fuller, G.N.; Huse, J.; Gilboa, E.; Kang, N.; Huang, X.; Verhaak, R.; Li, S.; Heimberger, A.B. Osteopontin mediates glioblastoma-associated macrophage infiltration and is a potential therapeutic target. The Journal of clinical investigation 2019, 129, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, B.; Yoon, D.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, J.; Hong, J.; Koo, H.; Sa, J.K. Integrative multi-omics characterization reveals sex differences in glioblastoma. Biology of Sex Differences 2024, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, L.; Lorenz, J.; Quach, S.; Braun, F.K.; Rothhammer-Hampl, T.; Ammer, L.M.; Vollmann-Zwerenz, A.; Bartos, L.M.; Dekorsy, F.J.; Holzgreve, A.; Kirchleitner, S.V.; Thon, N.; Greve, T.; Ruf, V.; Herms, J.; Bader, S.; Milenkovic, V.M.; von Baumgarten, L.; Menevse, A.N.; Hussein, A.; Sax, J.; Wetzel, C.H.; Rupprecht, R.; Proescholdt, M.; Schmidt, N.O.; Beckhove, P.; Hau, P.; Tonn, J.C.; Bartenstein, P.; Brendel, M.; Albert, N.L.; Riemenschneider, M.J. Translocator protein (18kDA) (TSPO) marks mesenchymal glioblastoma cell populations characterized by elevated numbers of tumor-associated macrophages. Acta neuropathologica communications 2023, 11, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammer, L.-M.; Vollmann-Zwerenz, A.; Ruf, V.; Wetzel, C.H.; Riemenschneider, M.J.; Albert, N.L.; Beckhove, P.; Hau, P. The Role of Translocator Protein TSPO in Hallmarks of Glioblastoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Rubin, J.B.; Lathia, J.D.; Berens, M.E.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. Females have the survival advantage in glioblastoma. Neuro-oncology 2018, 20, 576–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalcman, N.; Canello, T.; Ovadia, H.; Charbit, H.; Zelikovitch, B.; Mordechai, A.; Fellig, Y.; Rabani, S.; Shahar, T.; Lossos, A.; Lavon, I. Androgen receptor: a potential therapeutic target for glioblastoma. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 19980–19993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, N.; Khan, R.; Hung, M.-y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, T.J.C.; Lin, C. The prognostic significance of androgen receptor expression in gliomas. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 22122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, C.K.; Nna, U.J.; Sun, H.; Wilder-Romans, K.; Dresser, J.; Kothari, A.U.; Zhou, W.; Yao, Y.; Rao, A.; Stallard, S.; Koschmann, C.; Bor, T.; Debinski, W.; Hegedus, A.M.; Morgan, M.A.; Venneti, S.; Baskin-Bey, E.; Spratt, D.E.; Colman, H.; Sarkaria, J.N.; Chinnaiyan, A.M.; Eisner, J.R.; Speers, C.; Lawrence, T.S.; Strowd, R.E.; Wahl, D.R. Expression of the Androgen Receptor Governs Radiation Resistance in a Subset of Glioblastomas Vulnerable to Antiandrogen Therapy. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2020, 19, 2163–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariña-Jerónimo, H.; de Vera, A.; Medina, L.; Plata-Bello, J. Androgen Receptor Activity Is Associated with Worse Survival in Glioblastoma. Journal of integrative neuroscience 2022, 21, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, M.A.; Baskin, D.S.; Jenson, A.V.; Baskin, A.M. Hijacking Sexual Immuno-Privilege in GBM-An Immuno-Evasion Strategy. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Vega, A.M.; Del Moral-Morales, A.; Zamora-Sánchez, C.J.; Piña-Medina, A.G.; González-Arenas, A.; Camacho-Arroyo, I. Estradiol Induces Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition of Human Glioblastoma Cells. Cells 2020, 9, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Bian, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J. Expression of estrogen receptors, androgen receptor and steroid receptor coactivator-3 is negatively correlated to the differentiation of astrocytic tumors. Cancer epidemiology 2014, 38, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hönikl, L.S.; Lämmer, F.; Gempt, J.; Meyer, B.; Schlegel, J.; Delbridge, C. High expression of estrogen receptor alpha and aromatase in glial tumor cells is associated with gender-independent survival benefits in glioblastoma patients. J Neurooncol 2020, 147, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dueñas Jiménez, J.M.; Candanedo Arellano, A.; Santerre, A.; Orozco Suárez, S.; Sandoval Sánchez, H.; Feria Romero, I.; López-Elizalde, R.; Alonso Venegas, M.; Netel, B.; de la Torre Valdovinos, B.; Dueñas Jiménez, S.H. Aromatase and estrogen receptor alpha mRNA expression as prognostic biomarkers in patients with astrocytomas. Journal of Neuro-Oncology 2014, 119, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batistatou, A.; Kyzas, P.A.; Goussia, A.; Arkoumani, E.; Voulgaris, S.; Polyzoidis, K.; Agnantis, N.J.; Stefanou, D. Estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) protein expression correlates with BAG-1 and prognosis in brain glial tumours. Journal of Neuro-Oncology 2006, 77, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Arenas, A.; Hansberg-Pastor, V.; Hernández-Hernández, O.T.; González-García, T.K.; Henderson-Villalpando, J.; Lemus-Hernández, D.; Cruz-Barrios, A.; Rivas-Suárez, M.; Camacho-Arroyo, I. Estradiol increases cell growth in human astrocytoma cell lines through ERα activation and its interaction with SRC-1 and SRC-3 coactivators. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2012, 1823, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareddy, G.R.; Nair, B.C.; Gonugunta, V.K.; Zhang, Q.-g.; Brenner, A.; Brann, D.W.; Tekmal, R.R.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Therapeutic Significance of Estrogen Receptor β Agonists in Gliomas. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2012, 11, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, P.B.; Karve, A.S.; Zawit, M.; Arora, P.; Dave, N.; Awosika, J.; Li, N.; Fuhrman, B.; Medvedovic, M.; Sallans, L.; Kendler, A.; DasGupta, B.; Plas, D.; Curry, R.; Zuccarello, M.; Chaudhary, R.; Sengupta, S.; Wise-Draper, T.M. A Phase 0/I Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamics and Safety and Tolerability Study of Letrozole in Combination with Standard Therapy in Recurrent High-Grade Gliomas. Clinical Cancer Research 2024, 30, 2068–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirtz, A.; Lebourdais, N.; Rech, F.; Bailly, Y.; Vaginay, A.; Smaïl-Tabbone, M.; Dubois-Pot-Schneider, H.; Dumond, H. GPER Agonist G-1 Disrupts Tubulin Dynamics and Potentiates Temozolomide to Impair Glioblastoma Cell Proliferation. Cells 2021, 10, 3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello-Alvarez, C.; Camacho-Arroyo, I. Impact of sex in the prevalence and progression of glioblastomas: the role of gonadal steroid hormones. Biology of Sex Differences 2021, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).