Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

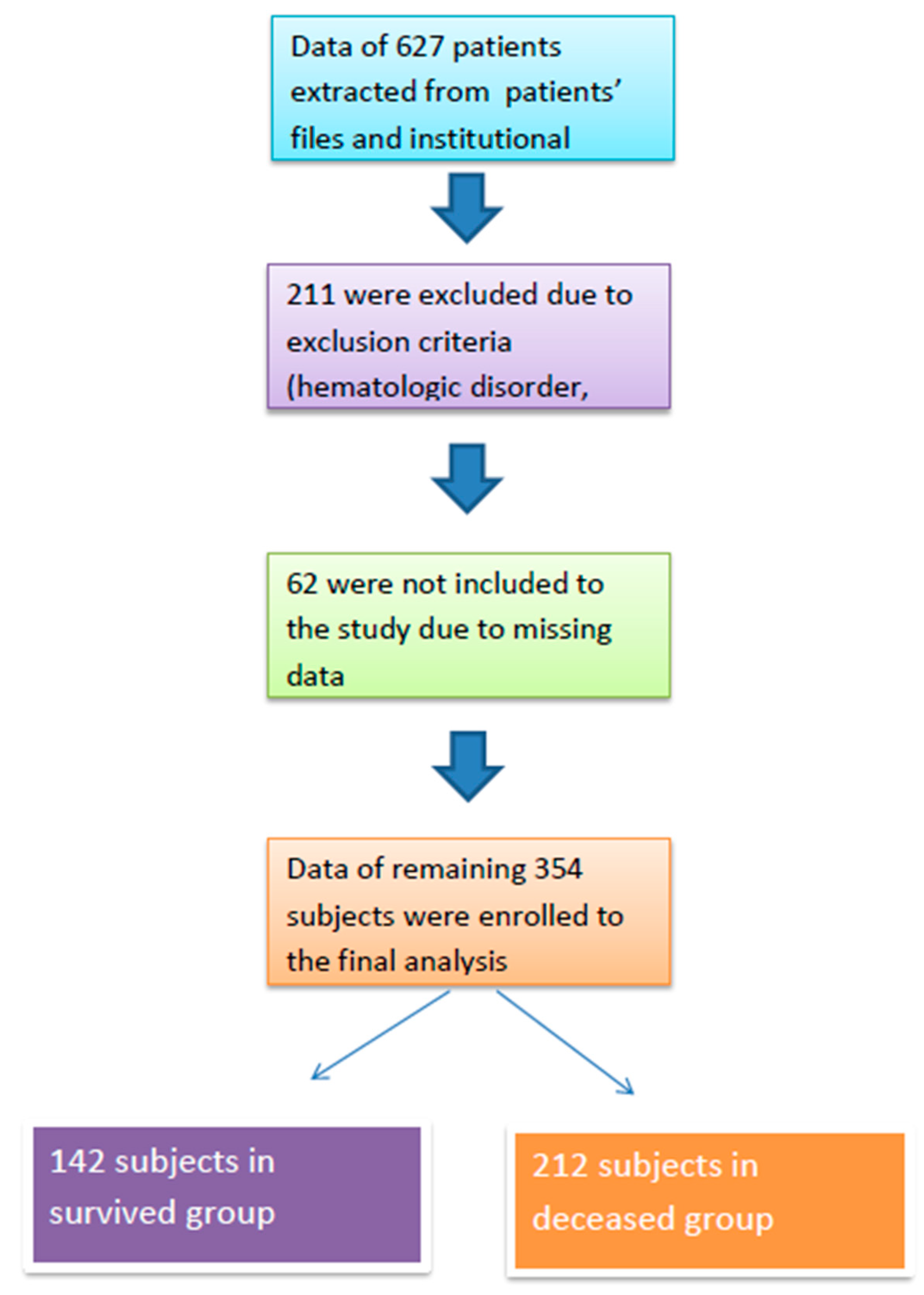

Study Population

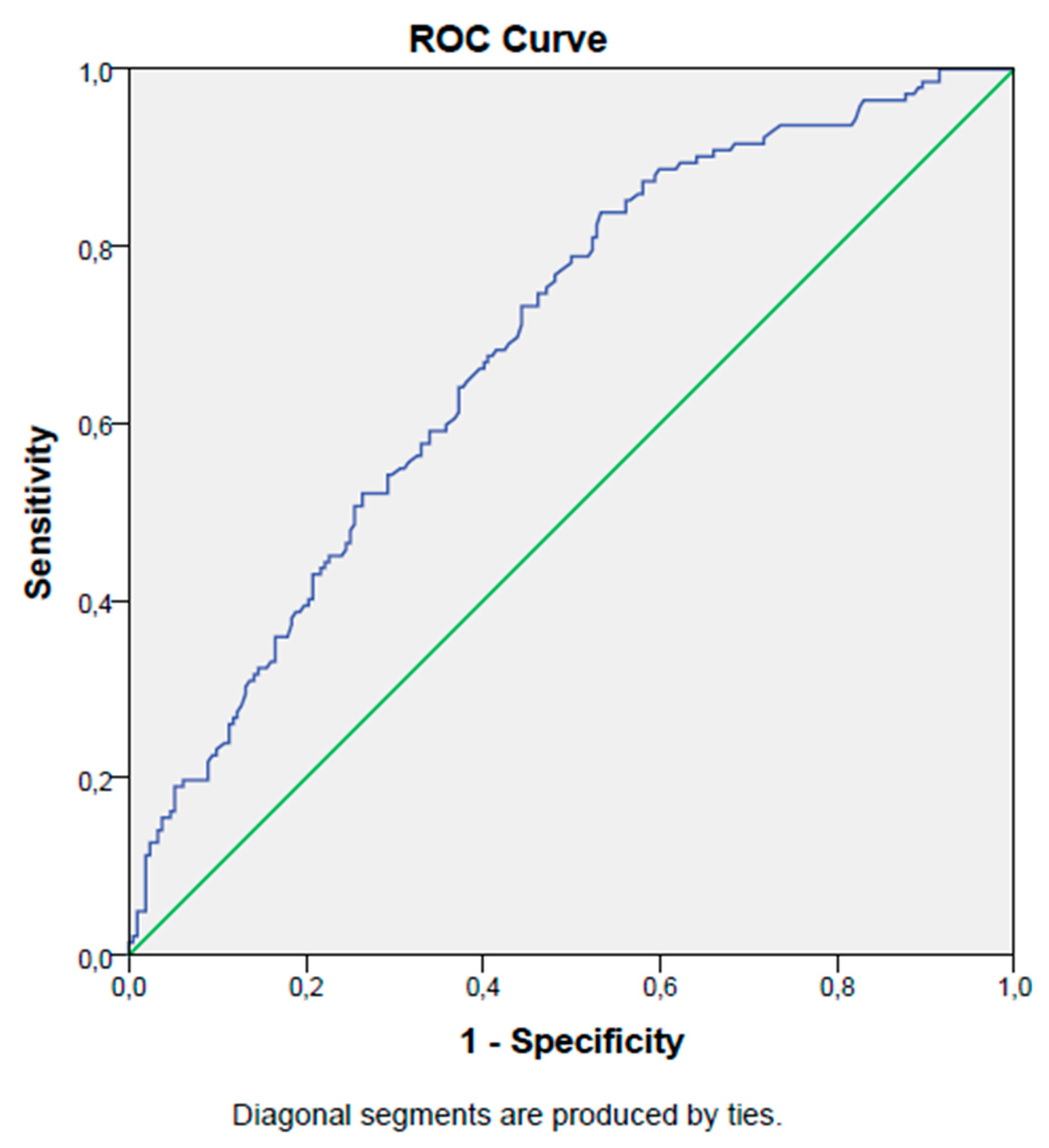

Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WBC | White blood cell count |

| neu | Neutrophil count |

| lym | Lymphocyte count |

| mono | Monocyte count |

| RDW | Red cell distribution width |

| PLT | Platelet count |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| Htc | Hematocrit |

| PDW | Platelet distribution width |

| MPV | Mean platelet volume |

| PG | Plasma glucose |

| CRP | c-reactive protein |

| PNI | Prognostic nutritional index |

References

- Pellathy, T. P., M. R. Pinsky, and M. Hravnak. "Intensive Care Unit Scoring Systems.". Crit Care Nurse 2021, 41, 54–64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagoz, I., G. Aktas, H. Yoldas, I. Yildiz, M. N. Ogun, M. Bilgi, and A. Demirhan. "Association between Hemogram Parameters and Survival of Critically Ill Patients.". J Intensive Care Med 2019, 34, 511–13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagoz, I., B. Ozer, I. Ital, M. Turkoglu, A. Disikirik, and S. Ozer. "C-Reactive Protein-to-Serum Albumin Ratio as a Marker of Prognosis in Adult Intensive Care Population.". Bratisl Lek Listy 2023, 124, 277–79.

- Demirkol, M. E., G. Aktas, M. Alisik, O. M. Yis, M. Kaya, and D. Kocadag. "Is the Prognostic Nutritional Index a Predictor of Covid-19 Related Hospitalizations and Mortality?". Malawi Med J 2023, 35, 15–21. [CrossRef]

- Aktas, G. "Association between the Prognostic Nutritional Index and Chronic Microvascular Complications in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus." J Clin Med 12, no. 18 (2023).

- Aktas, G. "Importance of the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index in Survival among the Geriatric Population. " Geriatr Gerontol Int 2024, 24, 444–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wullur, Yulia, and Nurpudji Astuti Taslim. "Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio, Prognostic Nutritional Index and Crp-Albumin Ratio Significantly Predict Mortality in Icu Patients with Low Nutrition Risk.". Nutr Clín Diet Hosp 2024, 44, 253–60.

- Sun, K., S. Chen, J. Xu, G. Li, and Y. He. "The Prognostic Significance of the Prognostic Nutritional Index in Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.". J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2014, 140, 1537–49. [CrossRef]

- Yan, L., T. Nakamura, A. Casadei-Gardini, G. Bruixola, Y. L. Huang, and Z. D. Hu. "Long-Term and Short-Term Prognostic Value of the Prognostic Nutritional Index in Cancer: A Narrative Review.". Ann Transl Med 2021, 9, 1630. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y. L., S. H. Sung, H. M. Cheng, P. F. Hsu, C. Y. Guo, W. C. Yu, and C. H. Chen. "Prognostic Nutritional Index and the Risk of Mortality in Patients with Acute Heart Failure." J Am Heart Assoc 6, no. 6 (2017).

- Zhang, J., X. Xiao, Y. Wu, J. Yang, Y. Zou, Y. Zhao, Q. Yang, and F. Liu. "Prognostic Nutritional Index as a Predictor of Diabetic Nephropathy Progression." Nutrients 14, no. 17 (2022).

- He, M., Q. Fan, Y. Zhu, D. Liu, X. Liu, S. Xu, J. Peng, and Z. Zhu. "The Need for Nutritional Assessment and Interventions Based on the Prognostic Nutritional Index for Patients with Femoral Fractures: A Retrospective Study.". Perioper Med (Lond) 2021, 10, 61. [CrossRef]

- Demirkol, M. E., G. Aktas, S. Bilgin, G. Kahveci, O. Kurtkulagi, B. M. Atak, and T. T. Duman. "C-Reactive Protein to Lymphocyte Count Ratio Is a Promising Novel Marker in Hepatitis C Infection: The Clear Hep-C Study." Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 68, no. 6 (2022): 838-41.

- Demirkol, Muhammed Emin, and Gulali Aktas. "C-Reactive Protein to Lymphocyte Count Ratio Could Be a Reliable Marker of Thyroiditis; the Clear-T Study.". Precision Medical Sciences 2022, 11, 31–34. [CrossRef]

- Faix, J. D. "Biomarkers of Sepsis. " Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2013, 50, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shami, I., H. M. A. Hourani, and B. Alkhatib. "The Use of Prognostic Nutritional Index (Pni) and Selected Inflammatory Indicators for Predicting Malnutrition in Covid-19 Patients: A Retrospective Study.". J Infect Public Health 2023, 16, 280–85. [CrossRef]

- Nomellini, V., L. J. Kaplan, C. A. Sims, and C. C. Caldwell. "Chronic Critical Illness and Persistent Inflammation: What Can We Learn from the Elderly, Injured, Septic, and Malnourished?". Shock 2018, 49, 4–14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, L., J. Huang, J. Ding, J. Kou, T. Shao, J. Li, L. Gao, W. Zheng, and Z. Wu. "Prognostic Nutritional Index Predicts Response and Prognosis in Cancer Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.". Front Nutr 2022, 9, 823087. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, R., M. Wehler, K. Mehler, D. Kreutzer, C. Koebnick, and E. G. Hahn. "Thrombocytopenia in Patients in the Medical Intensive Care Unit: Bleeding Prevalence, Transfusion Requirements, and Outcome.". Crit Care Med 2002, 30, 1765–71. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Y. Li, and X. Yang. "Platelet Phagocytosis by Leukocytes in a Patient with Cerebral Hemorrhage and Thrombocytopenia Caused by Gram-Negative Bacterial Infection.". J Int Med Res 2022, 50, 3000605221079102. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, O., D. M. Feldman, M. Diakow, and S. H. Sigal. "The Pathophysiology of Thrombocytopenia in Chronic Liver Disease.". Hepat Med 2016, 8, 39–50.

- Moreau, D., J. F. Timsit, A. Vesin, M. Garrouste-Orgeas, A. de Lassence, J. R. Zahar, C. Adrie, F. Vincent, Y. Cohen, B. Schlemmer, and E. Azoulay. "Platelet Count Decline: An Early Prognostic Marker in Critically Ill Patients with Prolonged Icu Stays.". Chest 2007, 131, 1735–41.

- uertas, M., J. L. Zayas-Castro, and P. J. Fabri. "Statistical and Prognostic Analysis of Dynamic Changes of Platelet Count in Icu Patients.". Physiol Meas 2015, 36, 939–53. [CrossRef]

- Korniluk, A., O. M. Koper-Lenkiewicz, J. Kamińska, H. Kemona, and V. Dymicka-Piekarska. "Mean Platelet Volume (Mpv): New Perspectives for an Old Marker in the Course and Prognosis of Inflammatory Conditions.". Mediators Inflamm 2019, 2019, 9213074.

- Cakir, Lutfullah, Gulali Aktas, OZGUR Enginyurt, and Sahika Altas Cakir. "Mean Platelet Volume Increases in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Independent of Hba1c Level.". Acta Medica Mediterranea 2014, 30, 425–28.

- Kocak, M. Z., G. Aktas, E. Erkus, T. T. Duman, B. M. Atak, and H. Savli. "Mean Platelet Volume to Lymphocyte Ratio as a Novel Marker for Diabetic Nephropathy.". J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2018, 28, 844–47. [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, Satilmis, Burcin Meryem Atak Tel, Gizem Kahveci, Tuba Taslamacioglu Duman, Ozge Kurtkulagi, Semanur Yurum, Asli Erturk, Buse Balci, and Gulali Aktas. "Hypothyroidism Is Strongly Correlated with Mean Platelet Volume and Red Cell Distribution Width.". National Journal of Health Sciences 2021, 6, 7–10.

- Aktas, Gulali, Basri Cakiroglu, MUSTAFA Sit, UGUR Uyeturk, Aytekin Alçelik, Haluk Savli, and Eray Kemahli. "Mean Platelet Volume: A Simple Indicator of Chronic Prostatitis.". Acta Medica Mediterranea 2013, 29, 551–54.

- Dagistan, Y., E. Dagistan, A. R. Gezici, S. Halicioglu, S. Akar, N. Özkan, and A. Gulali. "Could Red Cell Distribution Width and Mean Platelet Volume Be a Predictor for Lumbar Disc Hernias?" Ideggyogy Sz 69, no. 11-12 (2016): 411-14.

- Aktas, G., A. Alcelik, B. K. Tekce, V. Tekelioglu, M. Sit, and H. Savli. "Red Cell Distribution Width and Mean Platelet Volume in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome." Prz Gastroenterol 9, no. 3 (2014): 160-3.

- Balci, Sumeyye Buse , and Gulali Aktas. "A Comprehensive Review of the Role of Hemogram Derived Inflammatory Markers in Gastrointestinal Conditions.". Iranian Journal of Colorectal Research 2022, 10, 75–86.

- Cakır, Lutfullah, Gulali Aktas, Oznur Berke Mercimek, Ozgur Enginyurt, Yasemin Kaya, and Kutsal Mercimek. "Are Red Cell Distribution Width and Mean Platelet Volume Associated with Rheumatoid Arthritis.". Biomed Res 2016, 27, 292–94.

- Aktas, Gulali, Mehmet Zahid Kocak, Tuba Taslamacioglu Duman, Edip Erkus, Burcin Meryem Atak, Mustafa Sit, and Haluk Savli. "Mean Platelet Volume (Mpv) as an Inflammatory Marker in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity.". Bali Medical Journal 2018, 7, 650–53.

- Aktas, G., M. Sit, H. Tekce, A. Alcelik, H. Savli, T. Simsek, E. Ozmen, A. Z. Isci, and T. Apuhan. "Mean Platelet Volume in Nasal Polyps.". West Indian Med J 2013, 62, 515–8.

- Mandel, J., M. Casari, M. Stepanyan, A. Martyanov, and C. Deppermann. "Beyond Hemostasis: Platelet Innate Immune Interactions and Thromboinflammation." Int J Mol Sci 23, no. 7 (2022).

- Akan, S. , and G. Aktas. "Relationship between Frailty, According to Three Frail Scores, and Clinical and Laboratory Parameters of the Geriatric Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus." Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 68, no. 8 (2022): 1073-77.

- Chen, Y., L. Liu, X. Yang, W. Wan, Y. Liu, and X. Zhang. "Correlation between Malnutrition and Mortality in Older Patients Aged ≥90 Years with Multimorbidity." Geriatr Nurs 59 (2024): 321-29.

- Suzuki, E., N. Kawata, A. Shimada, H. Sato, R. Anazawa, M. Suzuki, Y. Shiko, M. Yamamoto, J. Ikari, K. Tatsumi, and T. Suzuki. "Prognostic Nutritional Index (Pni) as a Potential Prognostic Tool for Exacerbation of Copd in Elderly Patients.". Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2023, 18, 1077–90. [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, M. D., T. Bala, Z. Wang, T. Loftus, and F. Moore. "Chronic Critical Illness Patients Fail to Respond to Current Evidence-Based Intensive Care Nutrition Secondarily to Persistent Inflammation, Immunosuppression, and Catabolic Syndrome." JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 44, no. 7 (2020): 1237-49.

- Molina, Pablo, Belén Vizcaíno, Emma Huarte, Luis M Pallardó, and Juan J Carrero. "Pathophysiology, Detection, and Treatment." In Nutritional Disorders in Chronic Kidney Disease, edited by Jonathan Craig, Donald Molony and Giovanni Strippoli, 617-57: Wiley, 2022.

- Khor, B. H., H. C. Tiong, S. C. Tan, R. Abdul Rahman, and A. H. Abdul Gafor. "Protein-Energy Wasting Assessment and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Acute Kidney Injury: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis." Nutrients 12, no. 9 (2020).

- Wang, D., X. Hu, L. Xiao, G. Long, L. Yao, Z. Wang, and L. Zhou. "Prognostic Nutritional Index and Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index Predict the Prognosis of Patients with Hcc.". J Gastrointest Surg 2021, 25, 421–27. [CrossRef]

- Xia, L. J., W. Li, J. C. Zhai, C. W. Yan, J. B. Chen, and H. Yang. "Significance of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio, Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio, Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio and Prognostic Nutritional Index for Predicting Clinical Outcomes in T1-2 Rectal Cancer." BMC Cancer 20, no. 1 (2020): 208.

- Jiang, Y., D. Xu, H. Song, B. Qiu, D. Tian, Z. Li, Y. Ji, and J. Wang. "Inflammation and Nutrition-Based Biomarkers in the Prognosis of Oesophageal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis." BMJ Open 11, no. 9 (2021): e048324.

- Xie, H., L. Wei, G. Yuan, M. Liu, S. Tang, and J. Gan. "Prognostic Value of Prognostic Nutritional Index in Patients with Colorectal Cancer Undergoing Surgical Treatment.". Front Nutr 2022, 9, 794489. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Survived Group | Deceased Group | p | ||

| Gender | Men (n,(%)) | 82 (58) | 130 (61) | 0.50 |

| Women (n,(%)) | 60 (42) | 82 (39) | ||

| Median (IQR) | ||||

| Age (years) | 68 (27) | 73 (22) | <0.001 | |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.2 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.7) | <0.001 | |

| WBC (k/mm3) | 11.5 (8.8) | 12.6 (10) | 0.46 | |

| neu (k/mm3) | 9.5 (8.2) | 10.5 (9) | 0.19 | |

| lym (k/mm3) | 1.12 (0.8) | 1(0.9) | 0.02 | |

| mono (k/mm3) | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.5) | 0.30 | |

| RDW (%) | 17 (4) | 16 (4) | 0.40 | |

| PLT (k/mm3) | 217 (115) | 199 (157) | 0.002 | |

| PDW (%) | 17 (4) | 17 (6) | 0.09 | |

| MPV (fL) | 9 (3) | 8 (2.9) | <0.001 | |

| PG (mg/dL) | 133 (75) | 143 (85) | 0.06 | |

| CRP (mg/L) | 49 (82) | 112 (102) | <0.001 | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.7) | 1.3 (1.2) | <0.001 | |

| Mean ± SD | ||||

| Hb (g/dL) | 12 ± 2.5 | 13 ± 2.4 | 0.48 | |

| Htc (%) | 36 ± 8 | 39 ± 7 | 0.56 | |

| PNI (%) | 39 ± 7.5 | 34 ± 7.3 | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).