Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

05 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

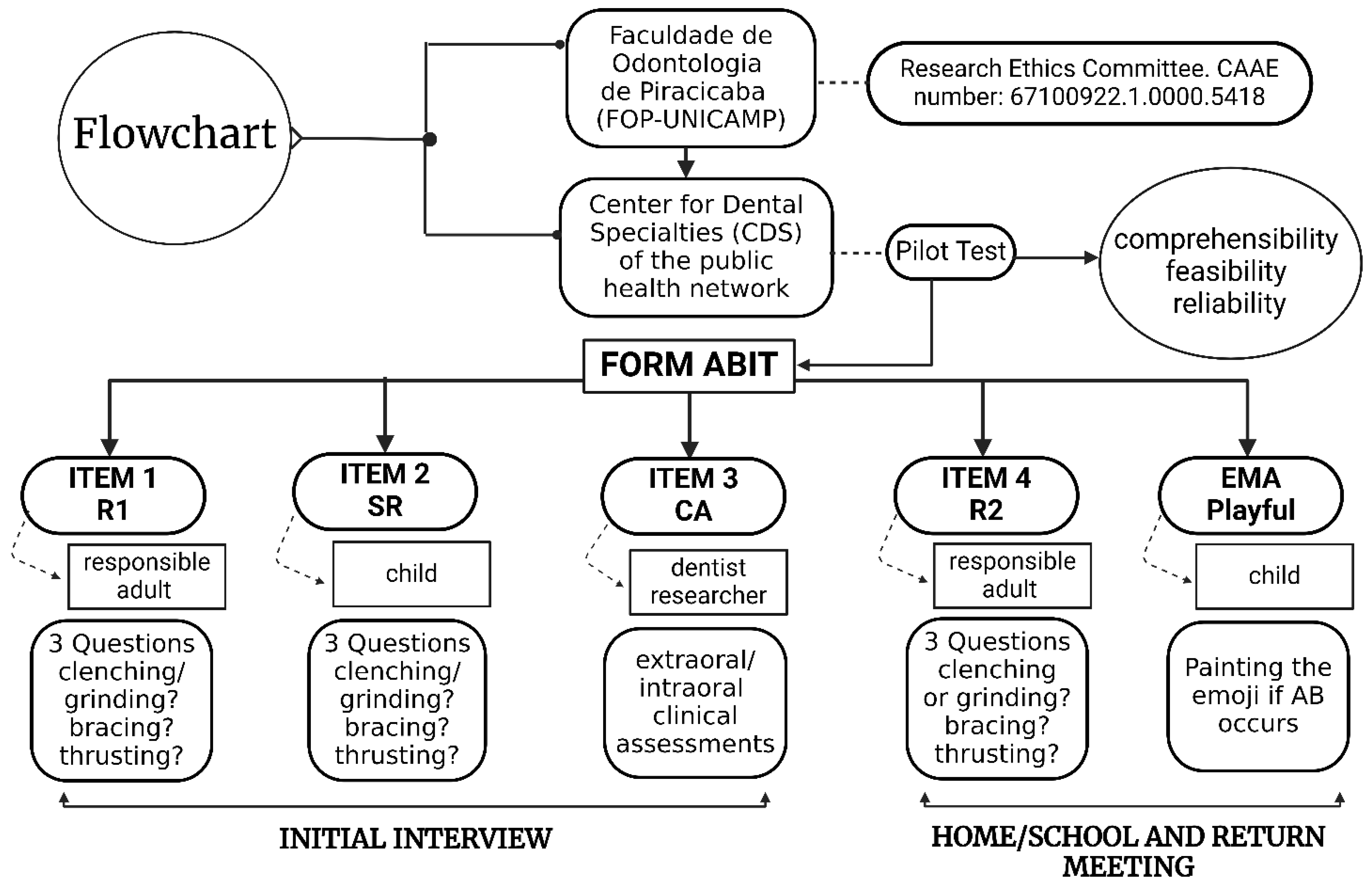

2. Materials and Methods

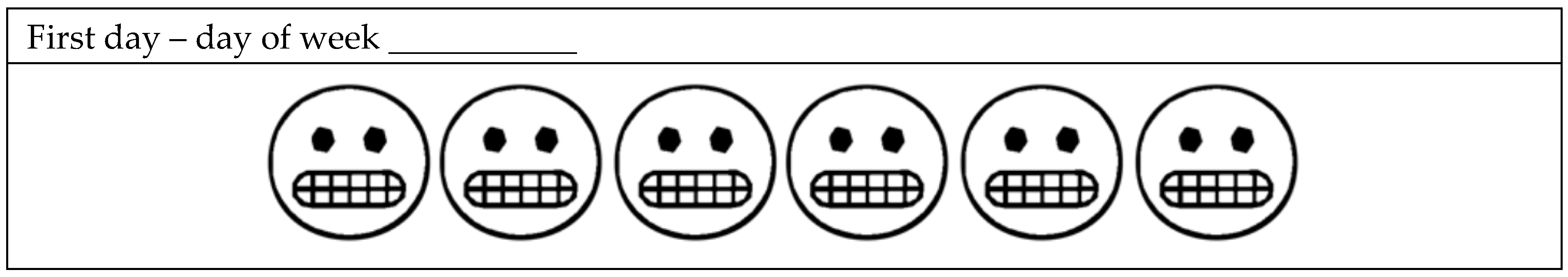

2.1. Tool Presentation

2.2. Cut-Off Points and Data Interpretation

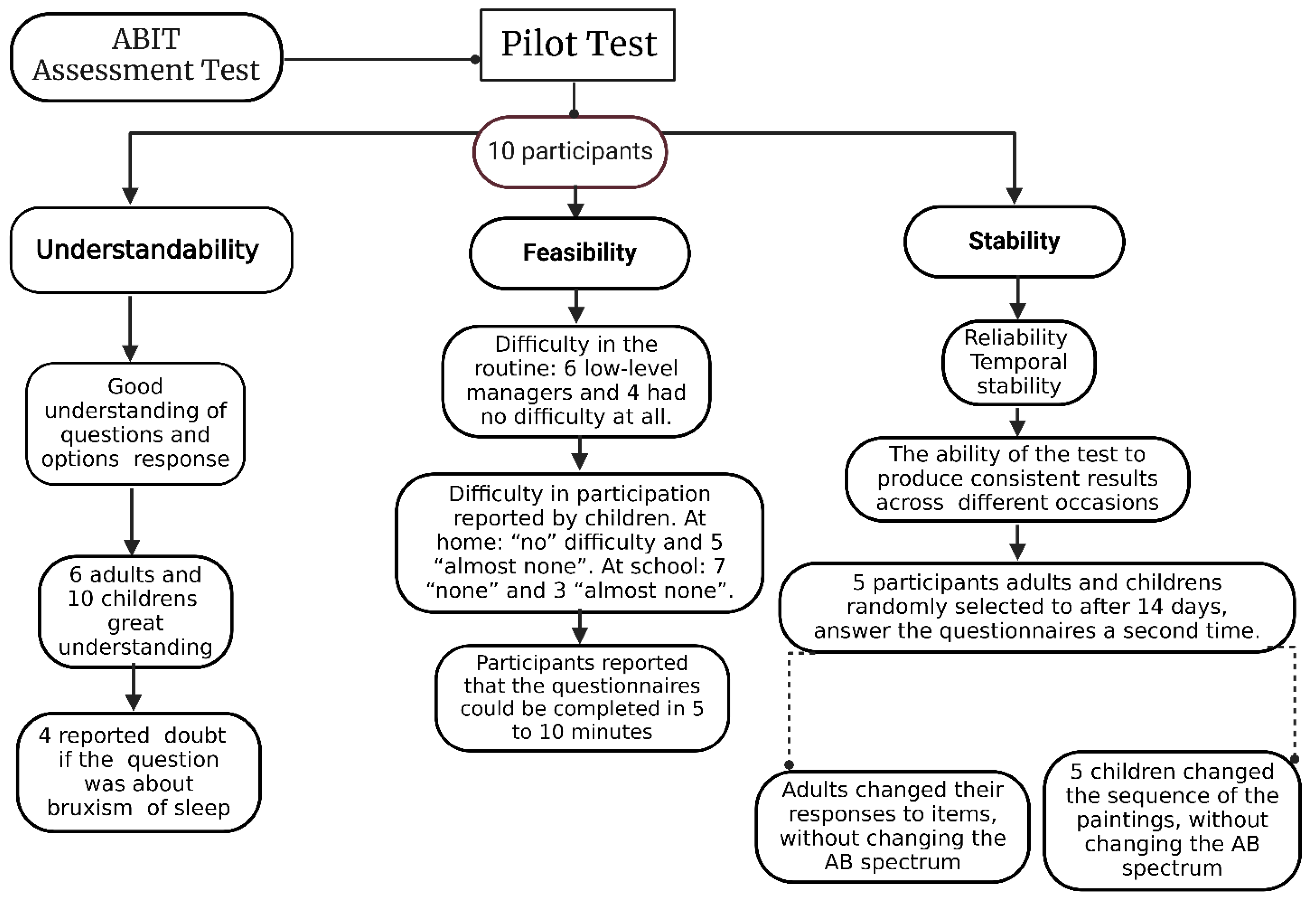

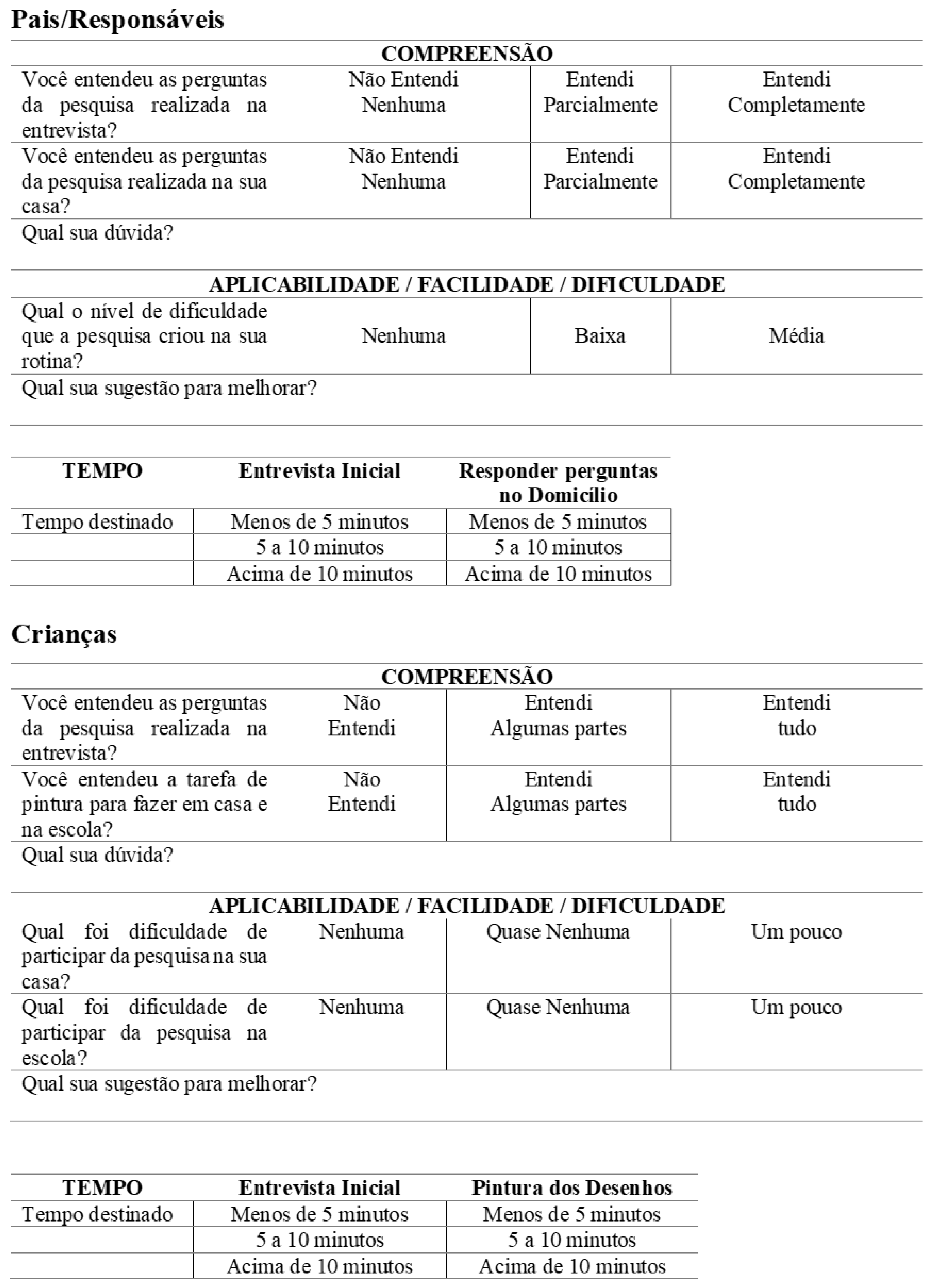

2.3. Pilot Study

3. Results

3.1. Testing ABIT Items

3.2. AB frequency in the Test Group

4. Discussion

4.1. About the Tool Development

4.2. Pilot Test of the Tool

4.3. Frequency of AB in the Pilot Group

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

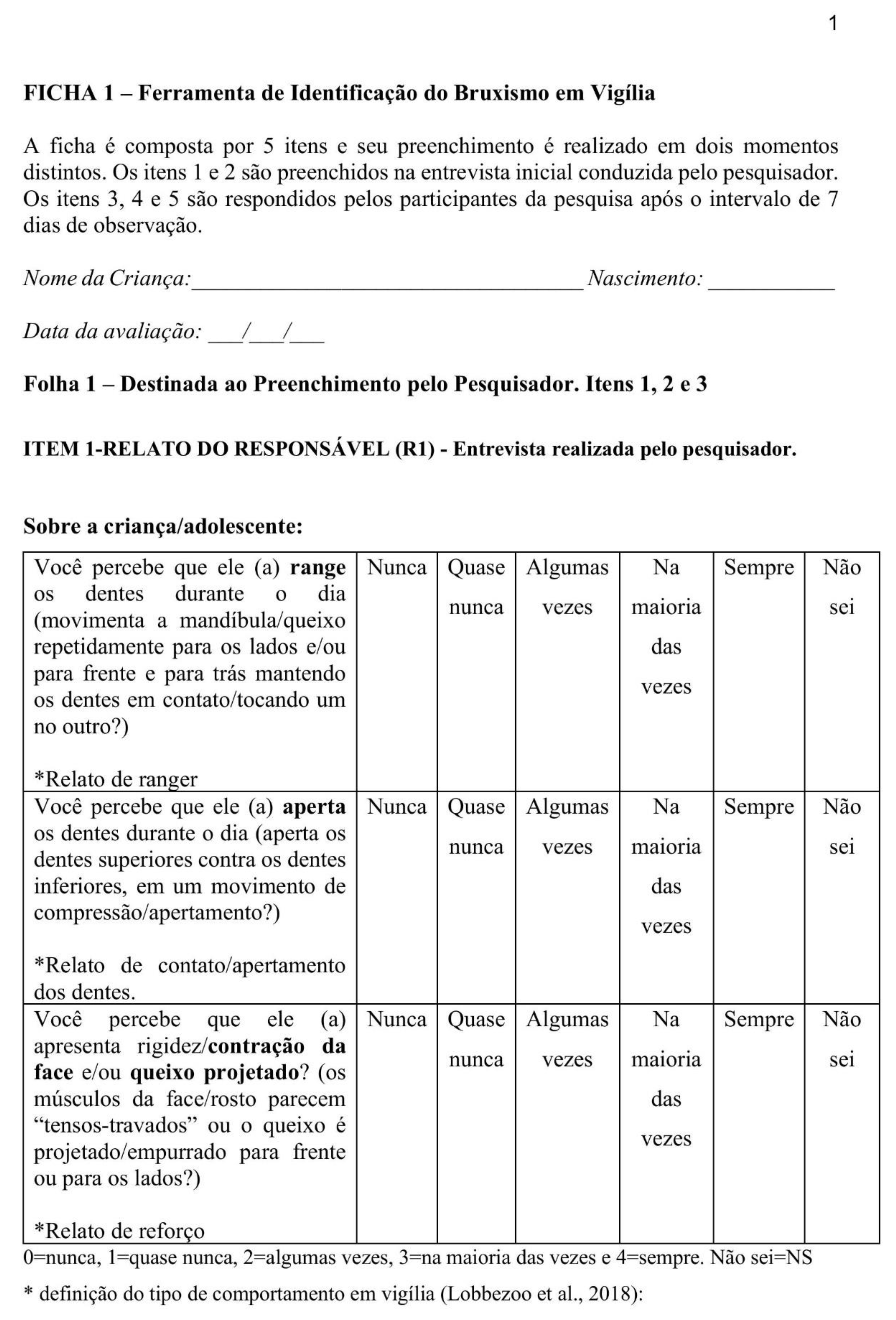

Appendix A.1 - Awake Bruxism Identification Tool (ABIT) in Brazilian Portuguese

Appendix A.2

Appendix B - Dental Wear Results

| Participant | Degree 0 | Degree 1 | Degree 2 | Degree 3 | Degree 4 |

| 1 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 22 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 19 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 20 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 22 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 19 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 20 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B Note: Individualized Data of Dental wear. Five-point ordinal grading scale: Grade 0 = no visible wear; Grade 1 = visible enamel wear; Grade 2 = visible wear with dentin exposure and loss of clinical crown height ≤ 1/3; Grade 3 = loss of clinical crown height >1/3 but < 2/3; Grade 4 = loss of clinical crown height ≥ 2/3 [5], with attention to distinguishing it from chemical wear, based on specific criteria [23,24]. Source: data by research (ICA-ABIT). | |||||

References

- Lobbezoo, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Glaros, A.G.; Kato, T.; Koyano, K.; Lavigne, G.J.; de Leeuw, R.; Manfredini, D.; Svensson, P.; Winocur, E. Bruxism defined and graded: An international consensus. J. Oral. Rehabil. 2013, 40, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Raphael, K.G.; Wetselaar, P.; Glaros, A.G.; Kato, T.; Santiago, V.; Winocur, E.; De Laat, A.; De Leeuw, R.; et al. International consensus on the assessment of bruxism: Report of a work in progress. J. Oral Rehabil. 2018, 45, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raphael, K.G.; Santiago, V.; Lobbezoo, F. Is bruxism a disorder or a behaviour? Rethinking the international consensus on defining and grading of bruxism. J. Oral Rehabil. 2016, 43, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Arreghini, A.; Lombardo, L.; Visentin, A.; Cerea, S.; Castroflorio, T.; Siciliani, G. Assessment of Anxiety and Coping Features in Bruxers: A Portable Electromyographic and Electrocardiographic Study. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache 2016, 30, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Naeije, M. A reliability study of clinical tooth wear measurements. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2001, 86, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Ahlberg, J.; Lobbezoo, F. Bruxism definition: Past, present, and future—What should a prosthodontist know? J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiffman, S.; Stone, A.A.; Hufford, M.R. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 4, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Câmara-Souza, M.B.; Carvalho, A.G.; Figueredo, O.M.C.; Bracci, A.; Manfredini, D.; Rodrigues Garcia, R.C.M. Awake bruxism frequency and psychosocial factors in college preparatory students. Cranio 2023, 41, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storari, M.; Serri, M.; Aprile, M.; Denotti, G.; Viscuso, D. Bruxism in children: What do we know? Narrative Review of the current evidence. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2023, 24, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, G.; Pająk, A.; Wójcicki, M. Global Prevalence of Sleep Bruxism and Awake Bruxism in Pediatric and Adult Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman Rubin, P.; Erez, A.; Peretz, B.; Birenboim-Wilensky, R.; Winocur, E. Prevalence of bruxism and temporomandibular disorders among orphans in southeast Uganda: A gender and age comparison. Cranio 2018, 36, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetselaar, P.; Vermaire, E.J.H.; Lobbezoo, F.; Schuller, A.A. The prevalence of awake bruxism and sleep bruxism in the Dutch adolescent population. J. Oral. Rehabil 2021, 48, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, J.M.D.; Pauletto, P. , Massignan, C., D'Souza, N.; Gonçalves, D.A.G., Flores-Mir, C.; De Luca Canto, G. Prevalence of awake Bruxism: A systematic review. J. Dent. 2023, 138, 104715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, J.K.; Lucietto, T.M.; Scheffel, D.L.S.; Ramos, A.L.; Provenzano, M.G.A. Sleep and Awake Bruxism in Pediatric Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study of Prevalence and Associated Factors. J. Adv. Med. Med. Res. 2024, 36, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, A.; Bracci, A.; Ahlberg, J.; Câmara-Souza, M.B.; Bucci, R.; Conti, P.C.R.; Dias, R.; Emodi-Perlmam, A.; Favero, R.; Häggmän-Henrikson, B.; Michelotti, A.; Nykänen, L.; Stanisic, N.; Winocur, E.; Lobbezoo, F.; Manfredini, D. Ecological Momentary Assessment of Awake Bruxism Behaviors: A Scoping Review of Findings from Smartphone-Based Studies in Healthy Young Adults. J Clin Med. 2023, 28, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runyan, J.D.; Steinke, E.G. Virtues, ecological momentary assessment/intervention and smartphone technology. Front Psychol. 2015, 6, 6–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Bracci, A.; Djukic, G. BruxApp: the ecological momentary assessment of awake bruxism. Minerva Stomatol. 2016, 65, 252–255. [Google Scholar]

- Manfredini, D.; Ahlberg, J.; Aarab, G.; Bracci, A.; Durham, J.; Ettlin, D.; Gallo, L.M.; Koutris, M.; Wetselaar, P.; Svensson, P.; Lobbezoo, F. Towards a Standardized Tool for the Assessment of Bruxism (STAB)-Overview and general remarks of a multidimensional bruxism evaluation system. J Oral Rehabil. 2020, 47, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, A.; Lombardo, L.; Siciliani, G.; Bracci, A.; Guarda-Nardini, L.; Djukic, G.; Manfredini, D. Smartphone-based application for EMA assessment of awake bruxism: compliance evaluation in a sample of healthy young adults. Clin Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emodi-Perlman, A.; Manfredini, D.; Shalev, T.; Yevdayev, I.; Frideman-Rubin, P.; Bracci, A.; Arnias-Winocur, O.; Eli, I. Awake Bruxism-Single-Point Self-Report versus Ecological Momentary Assessment. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zani, A.; Lobbezoo, F.; Bracci, A.; Djukic, G.; Guarda-Nardini, L.; Favero, R.; Ferrari, M.; Aarab, G.; Manfredini, D. Smartphone-based evaluation of awake bruxism behaviours in a sample of healthy young adults: findings from two University centres. J Oral Rehabil. 2021, 48, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Verhoeff, M.C.; Aarab, G.; Bracci, A.; Koutris, M.; Nykänen, L.; Thymi, M.; Wetselaar, P.; Manfredini, D. The bruxism screener (BruxScreen): Development, pilot testing and face validity. J Oral Rehabil. 2023, 51, 13442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, C.; Ozgunaltay, G. Evaluation of tooth wear and associated risk factors: A matched case-Control study. Niger J Clin Pract. 2018, 21, 1607–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlueter, N.; Luka, B. Erosive tooth wear - a review on global prevalence and on its prevalence in risk groups. Br Dent J. 2018, 224, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likert, R. A Technique for the Measurement of Attitudes. Archives of Psychology 1932, 140, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Saúde. Lei nº 8.080; Diário Oficial da União: Brasil, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Castrillon, E.E.; Ou, K.L.; Wang, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, X.; Svensson, P. Sleep bruxism: an updated review of an old problem. Acta Odontol Scand. 2016, 74, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saracutu, O.I.; Manfredini, D.; Bracci, A.; Val, M.; Ferrari, M.; Colonna, A. Comparison Between Ecological Momentary Assessment and Self-Report of Awake Bruxism Behaviours in a Group of Healthy Young Adults. J Oral Rehabil. 2025, 52, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.L.; Fagundes, D.M.; Soares, P.B.F.; Ferreira, M.C. Knowledge of parents/caregivers about bruxism in children treated at the pediatric dentistry clinic. Sleep Sci. 2019, 12, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, T.R.; de Lima, L.C.M.; Neves, É.T. B.; Arruda, M.J.A.L.L.A.; Perazzo, M.F.; Paiva, S.M.; Serra-Negra, J.M.; Ferreira, F.M.; Granville-Garcia, A.F. Factors associated with awake bruxism according to perceptions of parents/guardians and self-reports of children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2022, 32, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracci, A.; Lobbezoo, F.; Häggman-Henrikson, B.; Colonna, A.; Nykänen, L.; Pollis, M.; Ahlberg, J.; Manfredini, D. International Network For Orofacial Pain And Related Disorders Methodology INfORM. Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives on Awake Bruxism Assessment: Expert Consensus Recommendations. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saracutu, O.I.; Manfredini, D.; Bracci, A.; Ferrari Cagidiaco, E.; Ferrari, M.; Colonna, A. Awake bruxism behaviors frequency in a group of healthy young adults with different psychological scores. Cranio. 2024, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucci, R.; Manfredini, D.; Lenci, F.; Simeon, V.; Bracci, A.; Michelotti, A. Comparison between Ecological Momentary Assessment and Questionnaire for Assessing the Frequency of Waking-Time Non-Functional Oral Behaviours. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, R.; Vaz, R.; Rodrigues, M.J.; Serra-Negra, J.M.; Bracci, A.; Manfredini, D. Utility of Smartphone-based real-time report (Ecological Momentary Assessment) in the assessment and monitoring of awake bruxism: A multiple-week interval study in a Portuguese population of university students. J Oral Rehabil. 2021, 48, 1307–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colonna, A.; Lobbezoo, F.; Bracci, A.; Ferrari, M.; Val, M.; Manfredini, D. Long-Term Study on the Fluctuation of Self-Reported Awake Bruxism in a Cohort of Healthy Young Adults. J Oral Rehabil. 2025, 52, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asami, K.; Fujisawa, M.; Saito-Murakami, K.; Miura, S.; Fujita, T.; Imamura, Y.; Koyama, S. Assessment of awake bruxism-Combinational analysis of ecological momentary assessment and electromyography. J Prosthodont Res. 2024, 68, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracci, A.; Lobbezoo, F.; Colonna, A.; Bender, S.; Conti, P.C.R.; Emodi-Perlman, A.; Häggman-Henrikson, B.; Klasser, G.D.; Michelotti, A.; Lavigne, G.J.; Svensson, P.; Ahlberg, J.; Manfredini, D. Research routes on awake bruxism metrics: Implications of the updated bruxism definition and evaluation strategies. J Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwasnicka, D.; Kale, D.; Schneider, V.; Keller, J.; Yeboah-Asiamah Asare, B.; Powell, D.; Naughton, F.; Ten Hoor, G.A.; Verboon, P.; Perski, O. Systematic review of ecological momentary assessment (EMA) studies of five public health-related behaviours: review protocol. BMJ Open. 2021, 11, e046435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brostolin, M.R.; Souza, T.M.F. de. A docência na educação infantil: pontos e contrapontos de uma educação inclusiva. Cad CEDES 2023, 43, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poluha, R.L.; Macário, H.S.; Câmara-Souza, M.B.; De la Torre Canales, G.; Ernberg, M.; Stuginski-Barbosa, J. Benefits of the combination of digital and analogic tools as a strategy to control possible awake bruxism: A randomised clinical trial. J Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, I.M.; Vale, M.P.; Alonso, L.S.; Abreu, L.G.; Tourino, L.F.P.G.; Serra-Negra, J.M.C. Association Between Probable Awake Bruxism and School Bullying in Children and Adolescents: A Case-Control Study. Pediatr Dent. 2022, 44, 284–289. [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne, G.J.; Rompré, P.H.; Montplaisir, J.Y. Sleep bruxism: validity of clinical research diagnostic criteria in a controlled polysomnographic study. J Dent Res. 1996, 75, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giudice, M.; Marra, A.; Barba, A.; Passariello, N.; D'Onofrio, F. Hypertrophy of the masseter: a rare case associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Minerva stomatol 1992, 41, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prado, I.M.; Abreu, L.G.; Pordeus, I.A.; Amin, M.; Paiva, S.M.; Serra-Negra, J.M. Diagnosis and prevalence of probable awake and sleep bruxism in adolescents: an exploratory analysis. Braz Dent J. 2023, 34, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nykänen, L.; Manfredini, D.; Lobbezoo, F.; Kämppi, A.; Bracci, A.; Ahlberg, J. Assessment of awake bruxism by a novel bruxism screener and ecological momentary assessment among patients with masticatory muscle myalgia and healthy controls. J Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgenberg-Sydney, P.B.; Lorenzon, A.L.; Pimentel, G.; Petterle, R.R.; Bonotto, D. Probable awake bruxism - prevalence and associated factors: a cross-sectional study. Dental Press J Orthod. 2022, 27, e2220298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Ahlberg, J.; Aarab, G.; Bender, S.; Bracci, A.; Cistulli, P.A.; Conti, P.C.; De Leeuw, R.; Durham, J.; Emodi-Perlman, A.; Ettlin, D.; Gallo, L.M.; Häggman-Henrikson, B.; Hublin, C.; Kato, T.; Klasser, G.; Koutris, M.; Lavigne, G.J.; Paesani, D.; Peroz, I.; Svensson, P.; Wetselaar, P.; Lobbezoo, F. Standardised Tool for the Assessment of Bruxism. J Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 29–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Lobbezoo, F. Sleep bruxism and temporomandibular disorders: A scoping review of the literature. J Dent. 2021, 111, 103711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, A.; Noveri, L.; Ferrari, M.; Bracci, A.; Manfredini, D. Electromyographic Assessment of Masseter Muscle Activity: A Proposal for a 24 h Recording Device with Preliminary Data. J Clin Med. 2022, 12, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Jacobs, R.; De Laat, A.; Aarab, G.; Wetselaar, P.; Manfredini, D. Kauwen op bruxisme. Diagnostiek, beeldvorming, epidemiologie en oorzaken [Chewing on bruxism. Diagnosis, imaging, epidemiology and aetiology]. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 2017, 124, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Classical test theory. Med Care. 2006, 44 (Suppl 3), S50–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquali, L. Psicometria. Rev esc enferm USP [Internet] 2009, 43, 992–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vet, H.; Terwee, C.; Mokkink, L.; Knol, D. Measurement in Medicine: A Practical Guide, 1 ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, Brazil, 2011; pp. 1–338. [Google Scholar]

- Manfredini, D.; Ahlberg, J.; Wetselaar, P.; Svensson, P.; Lobbezoo, F. The bruxism construct: From cut-off points to a continuum spectrum. J Oral Rehabil. 2019, 46, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuert, C.E.; Kunz, T.; Gummer, T. An empirical evaluation of probing questions investigating question comprehensibility in web surveys. Int. J. Soc. Res. 2024, 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, A.C.; Alexandre, N.M.C.; Guirardello, E. de B. Propriedades psicométricas na avaliação de instrumentos: avaliação da confiabilidade e da validade. Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde 2017, 26, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winocur, E.; Messer, T.; Eli, I.; Emodi-Perlman, A.; Kedem, R.; Reiter, S.; Friedman-Rubin, P. Awake and Sleep Bruxism Among Israeli Adolescents. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marceliano, C.R.V.; Gavião, M.B.D. Possible sleep bruxism and biological rhythm in school children. Clin Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 2979–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracci, A.; Djukic, G.; Favero, L.; Salmaso, L.; Guarda-Nardini, L.; Manfredini, D. Frequency of awake bruxism behaviours in the natural environment. A 7-day, multiple-point observation of real-time report in healthy young adults. J Oral Rehabil. 2018, 45, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, R.E.; Auclair, C.W. The clinical management of awake bruxism. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017, 148, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zani, A.; Lobbezoo, F.; Bracci, A.; Ahlberg, J.; Manfredini, D. Ecological Momentary Assessment and Intervention Principles for the Study of Awake Bruxism Behaviors, Part 1: General Principles and Preliminary Data on Healthy Young Italian Adults. Front Neurol. 2019, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walentek, N.P.; Schäfer, R.; Bergmann, N.; Franken, M.; Ommerborn, M.A. Relationship between Sleep Bruxism Determined by Non-Instrumental and Instrumental Approaches and Psychometric Variables. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024, 21, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Scores | Cutoff Values | Clinical Interpretation Possibilities | AB Spectrum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | 0 a 4 | Greater than or equal to 1* | Possible | 12 |

| SR | 0 a 4 | Greater than or equal to 1* | Possible | 12 |

| R2 | 0 a 4 | Greater than or equal to 1* | Possible | 12 |

| ICA | 0 a 6 | Greater than or equal to 1* | Probable | 6 |

| ECA | 0 a 2 | Greater than or equal to 1* | Probable | 2 |

| EMA | 0 a 42 | Greater than or equal to 4 days with paintings |

Possible corroborated by EMA Probable corroborated by EMA |

42 |

| 96 |

| Stage | Participant | Clinic Score |

Score R1 | Score R2 | Score SR | EMA | Score ABIT |

Spectrum AB | SB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 13 | 24 | Possible AB corroborated by EMA | Yes |

| T | 2 | 0 | 0 | Null | 0 | 0 | 0 | No AB | No |

| T | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No AB | Yes |

| T | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 21 | Possible AB corroborated by EMA | No |

| T | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Null | <4 | 0 | No AB | No |

| T | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | <4 | 0 | No AB | No |

| T | 7 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | <4 | 9 | Possible AB | Yes |

| T | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Null | <4 | 0 | No AB | No |

| T | 9 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 28 | Possible AB corroborated by EMA | DK |

| T | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Null | <4 | 0 | No AB | No |

| T | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 13 | 24 | Possible AB corroborated by EMA | |

| R | 1 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 22 | Possible AB corroborated by EMA | ||

| T | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 21 | Possible AB corroborated by EMA | |

| R | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 21 | Possible AB corroborated by EMA | ||

| T | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | <4 | 0 | No AB | |

| R | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No AB | ||

| T | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Null | <4 | 0 | No AB | |

| R | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No AB | ||

| T | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Null | <4 | 0 | No AB | |

| R | 0 | 0 | 0 | Null | <4 | 0 | No AB |

| Stage | AB Behavior | Parent´s Relats R1 |

Parent´s Relats R2 |

Child´s SR |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Teeth Griding | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| Retest | Teeth Griding | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Test | Teeth Clenching | 1 | 5 | 5 | 11 |

| Retest | Teeth Clenching | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| Test | Mandible Bracing/Thrusting | 3 | 4 | 3 | 10 |

| Retest | Mandible Bracing/Thrusting | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Stage | Participant | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1,85 |

| Test | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Test | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Test | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1,00 |

| Test | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.14 |

| Test | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0,14 |

| Test | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.14 |

| Test | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0,28 |

| Test | 9 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1,71 |

| Test | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0,14 |

| Test versus retest | |||||||||

| Test | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1,85 |

| Retest | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Test | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Retest | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0,71 |

| Test | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0,14 |

| Retest | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Test | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0,14 |

| Retest | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Test | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0,14 |

| Retest | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0,14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).