1. Introduction

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic widely used in medicine for the induction and maintenance of anesthesia. Ketamine anesthesia is applied in military field surgery because it enables simultaneous anesthesia for multiple patients and can save the lives of a significant number of casualties (Leslie et al., 2021; Butler 2017). However, in military medicine, ketamine is not recommended for high-ranking officers due to concerns, that it may impair their professionalism and, consequently, lead to inadequate command decisions (Barr et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2022).

Currently, it is impossible to abandon ketamine due to its numerous positive properties. The drug remains the safest general anesthetic, unlike all other anesthesiologic agents, as it uniquely stimulates and supports the cardiovascular and respiratory systems (Riccardi et al., 2023). Furthermore, many psychiatric side effects of ketamine can now be successfully managed, primarily through the use of neuroleptics (butyrophenone derivatives, benzodiazepines, and others), that correct unwanted changes (Li et al., 2016; Hashimoto, 2016).

However, the main problem with ketamine use is not related to intraoperative undesirable hemodynamic changes, but rather to long-term disturbances in the psycho-emotional sphere (sometimes lasting up to six months after ketamine anesthesia) (Pereira et al., 2024). Typically, such patients are not monitored by physicians after surgery, and subsequent deterioration of their cognitive functions and emotional state is rarely associated with ketamine's side effects.

Ketamine anesthesia can cause central nervous system (CNS) damage in the postoperative period, with postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) being particularly significant. POCD can develop in patients of various age groups with no history of psychoneurological conditions. According to various authors (Viderman et al., 2023; Belenichev et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2022; Ma et al., 2023), the frequency of POCD averages 36.8% of patients overall, ranges from 3% to 47% after cardiac surgery (with 42% of patients still affected 3-5 years after surgery), and from 7% to 26% after non-cardiac surgery (with 9.9% of patients affected for 3 months or more, and 1% of patients for over 2 years). Early POCD can lead to deterioration in patients' quality of life, specifically reducing their professionalism and level of socialization (Lee et al., 2015; Haller et al., 2021).

Among medications used to restore the psycho-emotional sphere in the postoperative period, piracetam is administered toward the end of surgery. However, there are extremely few other studies exploring pharmacological correction of POCD after ketamine. A neuroprotection concept has been proposed for POCD, aimed at timely restoration of neurochemical processes, cerebral hemodynamics, and elimination of cognitive-mnestic disorders (Fang et al., 2014). The complexity of developing staged neuroprotection after POCD lies precisely in the lack of exact knowledge about the subtle mechanisms of ketamine's neurotoxic action.

Our earlier research and data from other investigators have established that ketamine causes activation of ROS production through increased expression of i-NOS and n-NOS, neuroinflammation, dysfunction of neuronal mitochondria, initiation of neuroapoptosis, and consequently, deterioration of spatial and working memory, increased anxiety, and more episodes of depressive behavior (Belenichev et al., 2021; Belenichev et al., 2024a).

Currently, several nootropics have been proposed for POCD correction, including phenibut, ipacridine, cytoflavin, noopept, cerebrocurin, and thiocetam (Usenko et al., 2015; Colucci et al., 2012). However, modern nootropic agents and neurometabolic neuroprotectors do not fully resolve the POCD problem. Racetams (piracetam, phenotropil, pramiracetam) enhance anxiety and positively modulate anaerobic glycolysis in neurons, which exacerbates lactate acidosis. Cerebrocurin provides rapid metabolic effects, activates energy metabolism, reduces neuroapoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction, but does not affect amino-specific CNS systems such as GABA and serotonin, which play critical roles in the formation of anxiety, sadness, worry, anger, and emotional numbness (Dirks et al., 1984; Belenichev et al., 2022; Belenichev et al., 2025).

All this necessitates the development and creation of entirely new structures that would have affinity for GABA and 5HT2A receptors, influence genes associated with the expression of specific amino-specific system intermediates and the function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, as well as impact structural and functional abnormalities in the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and other brain regions (Sarawagi et al., 2021; Aznar, Herwig 2016; Sheng et al., 2021). Currently, developing more effective medications with improved safety profiles to enhance cognitive function and treat anxiety disorders is an important task in medicinal chemistry.

The stress response system involves several key receptor interactions in war-related PTSD. CRF1R is directly involved in stress response and anxiety. GABA(A) receptors are crucial for anxiety management and sleep disturbances. Serotonin receptors play key roles in mood regulation and traumatic memory processing. The complex symptomatology of PTSD involves multiple receptor systems, that are interconnected in addressing various symptoms: sleep disturbances (5-HT7, GABA(A)), hyperarousal (CRF1R, GABA(A)), depression (D2, 5-HT1A), anxiety (GABA(A), 5-HT1A), and cognitive issues (GluA3, M2).

In terms of treatment potential, a multi-target approach might be more effective for complex conditions like PTSD. Understanding receptor interactions could lead to more effective therapeutic strategies, with the potential for developing medications that address multiple symptoms simultaneously.

Based on the aforementioned considerations, our rational drug design strategy was directed toward combining the key structural features of various chemical classes of clinically confirmed pharmacophores (

Figure 1,

Table 1) and optimizing their molecules with saturated structural elements to increase lipophilicity and minimize toxicity.

Analysis of these reference compounds reveals essential pharmacophoric elements required for optimal nootropic and anxiolytic activity:

Core Structure Requirements

Essential azoheterocyclic core

N-methyl group for optimized GABA-A receptor binding

Strategically positioned cycloalkyl/heterocyclyl rings for receptor pocket compatibility

Linking Elements

Azapirone structure with piperazine linker

Specific alkylated terminal rings (pyrimidine, piperidine, pyridine, etc.)

Optimal four-carbon spacing between cyclic systems

Stability and Binding Elements

Cycloalkyl/alkyl groups for metabolic stability

Multiple hydrogen bond donors/acceptors

Flexible alkyl chains for conformational adaptation

Pharmacokinetic Considerations

The foundation of our rational design for promising bioactive substances is based on the modern experience of merging molecular fragments through spiro-conjunction. Moreover, azaheterocycles fused with spirocyclic fragments represent an exceptional tool in drug development, allowing for the adjustment of conformational and physicochemical properties of the investigated molecule (Zheng et al., 2014; Batista et al., 2022; Basavarajaet al., 2025).

The main advantage characteristic of this class of compounds is their inherent three-dimensional nature, which is beneficial for ligand interactions with the three-dimensional binding site of a biotarget. Another advantage is their solubility, which is associated with the high content of sp³-hybridized Carbon atoms. Importantly, this advantage liberates "lead compounds" from many pharmaco-technological and pharmacokinetic obligations that arise when implementing typical aromatic or heterocyclic structures. Furthermore, spiroheterocycles exhibit a broad spectrum of biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, anticonvulsant, antiproliferative, antimalarial, antimicrobial, and other types of activity (Zheng et al., 2014; Batista et al., 2022; Basavaraja et al., 2025; Kolomoets et al., 2017; Kholodnyak et al., 2016).

Therefore, the fusion of two molecular fragments was decided to be conducted

via a 5+1-heterocyclization reaction involving triazoloanilines and cycloalkanones (

Figure 2). We believe that the high content of sp³-hybridized Carbon atoms will not only improve drug-likeness criteria but also provide additional binding to molecular targets and lead to improved toxicological parameters.

Hence, to address above-mentioned challenges in treating cognitive and behavioral disorders following ketamine anesthesia, we employed a comprehensive research strategy combining computational design, organic synthesis, and biological evaluation.

Our approach focused on developing novel spiro(cycloalkyl-, heterocyclyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazolines with improved target engagement profiles and reduced side effects compared to existing agents. The comprehensive methodological approach enabled systematic investigation of our novel compounds from molecular design through behavioral and neurobiochemical evaluation. In the following sections, we present the results of these studies, beginning with in silico computational analyses and progressing to in vivo efficacy and mechanism evaluations.

2. Results

2.1. In Silico Analysis of Nootropic Potential

The main target for assessing the nootropic potential of the developed compounds was chosen glutamate receptor GluA3 (RCSB ID: 3LSX), due to its established role in the mechanisms of improving cognitive functions (Ahmed and Oswald, 2010). This ionotropic receptor mediates rapid excitatory synaptic transmission in the central nervous system and plays crucial roles in synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory processes. The selection of GluA3 as a target is particularly relevant given its involvement in cognitive enhancement pathways and its well-characterized structural interactions with established nootropics like piracetam (Gouhie et al., 2024; Ahmed and Oswald, 2010). Additionally, this receptor's role in neuroplasticity and potential therapeutic applications makes it an attractive target for novel cognitive enhancers (Tanimukai et al., 2009).

The binding interactions were analyzed using the CB-Dock2 methodology for protein-ligand blind docking, incorporating cavity detection and homologous template fitting as described by Liu et al. (2022) (

Figure 3,

Supplementary Materials,

Table S1).

Molecular docking analysis revealed that 13 compounds of 40 demonstrated binding affinities exceeding 7.3 kcal/mol within the GluA3 active pocket, surpassing the reference compound piracetam serving as a reference compound, that exhibited relatively weak binding affinity (-5.5 kcal/mol). This observation aligns with established structural studies of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor interactions, particularly the work of Ahmed and Oswald (2010), who demonstrated that related racetam compounds interact through distinct allosteric binding sites. AMPA receptors are tetramers composed of combinations of four subunits (GluA1-GluA4), which can assemble in various combinations to form functional channels.

The majority of synthesized compounds demonstrated binding affinities exceeding -8.0 kcal/mol against the target receptor, suggesting significant nootropic potential. Among which compounds 24 and 33 (-9.1 kcal/mol) show the strongest binding. Compound 24 is 2'-(pyridin-3-yl)-6'H-spiro[cyclohexane-1,5'-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazoline], while 33 is 2'-(adamantan-1-yl)-1-methyl-6'H-spiro[piperidine-4,5'-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazoline]. Compounds 13, 30, 28, 4, 21, 35 features preferably heterocyclic rings like benzofuran, furan, and thiophene, and show high-medium affinity (-8.8 to -8.5 kcal/mol). Medium affinity (-8.4 to -8.0 kcal/mol) is shown by group of compounds including 11, 8, 16, 23, 26, 37, and 40, etc. bearing various substituents at R position. Lower affinity (below -8.0 kcal/mol) notably includes compounds 1, 9, 10, and 36 with smaller ring systems.

Moreover, the recent analysis of spiro[1,5'/4,5'-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-

c]quinazoline] derivatives and their interaction with α1/β3/γ2L GABA(A) receptors (RCSB PDB ID: 6HUP) revealed important structure-activity relationships (

Table S2) (Antypenko et al., 2025a). Our findings indicate that an optimal balance between structural rigidity and conformational flexibility appears essential for maintaining effective binding interactions. Compounds containing expanded ring systems exhibited enhanced binding affinity, with calculated binding energies ranging from -12.4 to -11.8 kcal/mol. The strategic positioning of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors within these molecular structures contributed significantly to specific receptor interactions. Interestingly, the incorporation of electron-rich heterocyclic systems, particularly furan and thiophene moieties, generally resulted in diminished binding affinity, likely due to unfavorable electronic distribution patterns that disrupted optimal ligand-receptor interactions.

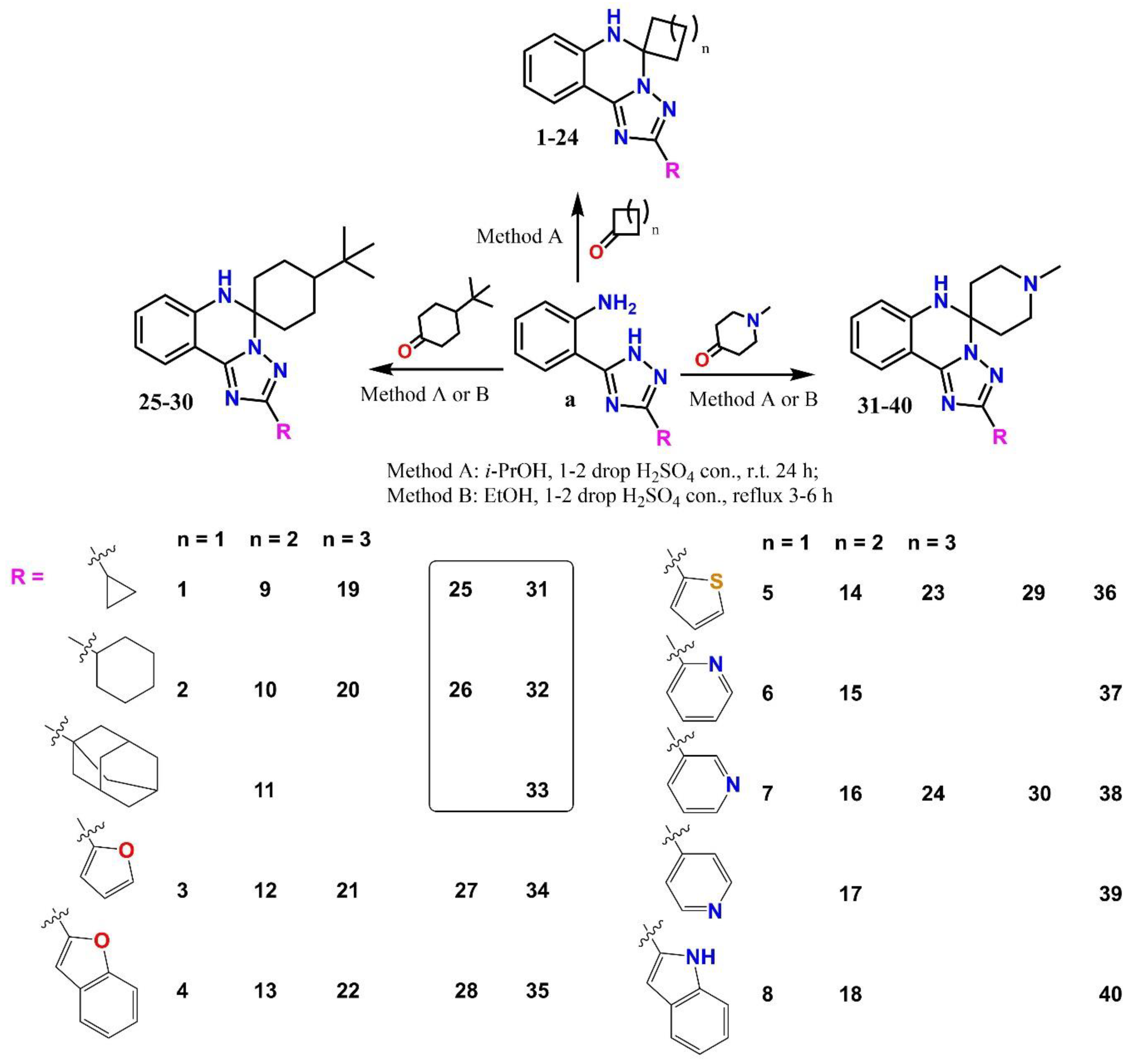

2.2. Synthesis of Novel spiro[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazoline derivatives

One of the approaches for constructing spiro derivatives is the [5+1]-cyclocondensation reactions, based on the interaction of 1,5-binucleophiles with carbonyl compounds (Kholodnyak et al., 2016a). Similarly, spiro[1,2,4]triazoloquinazolines (

1-

40) were obtained, specifically through the interaction of [2-(3-R-1

H-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl)phenyl]amines (

a) with cycloalkanones (cyclobutanone, cyclopentanone, cyclohexanone, 4-

tert-butylcyclohexanone) or

N-methylpiperidone (

Figure 4).

The cyclocondensation proceeded without peculiarities in propan-2-ol in the presence of a catalytic amount of sulfuric acid, following a mechanism that included three main processes: carbinolamine formation, elimination of a water molecule, and intramolecular cyclization (Pylypenko et al., 2024). The target products are formed with satisfactory and high yields (67-95%) (

Supplementary Materials, Spectral data). Furthermore, the reaction also proceeds in other organic solvents that are miscible with water and indifferent to the starting amines.

The formation of compounds 1-40 was confirmed by chromatography-mass spectrometry, 1H and 13C NMR spectra, and elemental analysis. In the 1H NMR spectra, the aromatic protons of the heterocycle form a characteristic ABCD system, which is represented by two doublets (H-7, H-9) and two triplets (H-8, H-10) with corresponding chemical shifts (Kholodnyak et al., 2016a). The characteristic proton of the NH-group (position 6) for these compounds is observed in the spectrum as a singlet in a wide range (7.22-3.79 ppm), and its chemical shift is determined by the donor-acceptor properties of the substituents in positions 2 and 5. In some compounds, the signal of this proton is absent or resonates together with the aromatic protons of the quinazoline cycle. The proton signals of the spiro-condensed fragment in position 6' and the substituent in position 2 of compounds 1-40 in most cases are easily interpreted and have classical shifts and multiplicity (Breitmaier, 2002). The 13C NMR spectra of compounds additionally confirm the regioselective course of the [5+1]cyclocondensation reaction. Thus, the characteristic signals of the sp3-hybridized Carbon atom in position 1,5' were observed at 83.1-70.0 ppm.

2.3. In Silico ADMET Evaluation

For

in vivo study, we selected 5 compounds:

25,

26,

31-

33. The selection represents distinct structural variations (different R-groups or spiro-cyclic/heterocyclic systems) to explore structure-activity relationship of activity: spiro-junction of cyclohexane

vs. N-methylpiperidine; 2'-position substituent: cyclopropyl

vs. cyclohexyl

vs. adamantyl; additional substituents:

tert-butyl group in compounds

25 and

26. Besides these compounds show consistently low toxicity predictions across multiple parameters (Antypenko et al., 2025b) compared to other compounds in the series (

Table 2).

ProTox-II (Banerjee et al., 2024) and SwissADME analysis (Daina et al., 2017) were conducted to determine their compliance with toxicity and drug-likeness criteria. The results of the toxicity study showed that these compounds, like piracetam and fabomotizole that were chosen as references for further in vivo studies, belong to toxicity class IV. All compounds are distinctive for showing "no" predictions for all toxicity parameters evaluated, indicating a potentially safer pharmacological profile. Still, cytotoxicity is predicted for all mentioned substances, except 25 and 26.

Most of the studied compounds, like the reference drugs, meet the criteria for drug-likeness: MW (Da) (< 500), n-HBA (< 10), n-HBD (≤ 5), TPSA (< 140 Ų) and logP (≤ 5) (

Table 3). The satisfactory TPSA value (> 140 Ų) for all compounds also correlates well with passive molecular transport across membranes. That is, the studied compounds will have a high ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier and flexibly interact with molecular targets. Additionally, the studied compounds show high predicted bioavailability. An exception to these criteria is compound

26, which has a high lipophilicity value (logP = 5.14), which can also be a positive characteristic, taking into account the structure of the neuron membrane. Importantly, the studied compounds pass the "drug-likeness" criteria for all filters (Lipinski, Veber, Muegge, Ghose, Egan), which are widely used in drug design. Only compound

25 and

26 piracetam have few violations of Veber and Egan filters.

Moreover, all compounds in this study were evaluated against Brenk structural filters and Pan-Assay Interference compounds (PAINS) criteria. No structural alerts were identified, suggesting a reduced likelihood of false positives or reactive functionalities in the tested chemical series. However, absence of these alerts does not guarantee lack of other potential mechanisms of interference, and standard validation protocols were still employed.

2.4. Evaluation of Behavioral and Neurobiochemical Effects In Vivo

2.4.1. Open Field Test Following Ketamine Anesthesia

The ketamine-induced cognitive impairment paradigm was selected as the primary screening model for evaluating novel nootropic compounds (Duman et al., 2012; Zanos and Gould, 2018; Krystal et al., 2019). This model demonstrates particular relevance for the structure-based approach due to the overlapping mechanisms between the target compounds and ketamine in glutamatergic and monoaminergic systems. The ketamine model offers several advantages for evaluating novel compounds. First, ketamine's well-characterized antagonism of NMDA receptors produces reproducible cognitive deficits that can be quantitatively measured. Second, these deficits share neurochemical similarities with a variety of clinical conditions where cognitive improvement is desired. Third, the model allows us to assess both direct cognitive enhancement and the ability to reverse the induced deficit, providing additional insights into the mechanisms of action of the compounds. Furthermore, this model is particularly relevant for the evaluation of compounds structurally related to reference molecules in the study, as these agents often act through glutamate-dependent mechanisms. Thus, the ketamine model provides a mechanistically relevant framework for evaluating the structural approach to drug development.

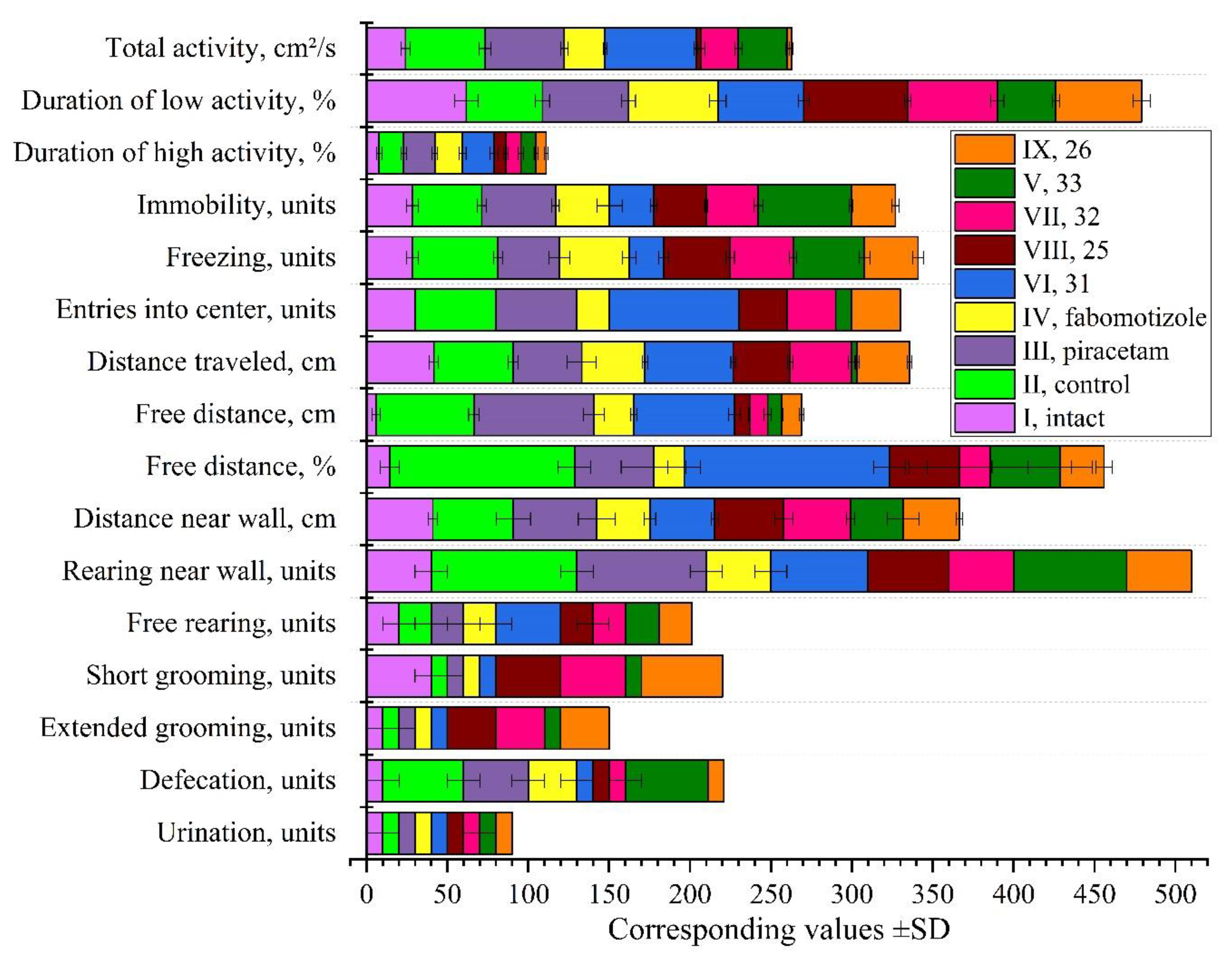

Analysis of specific behavioral indicators in the open field test revealed that ketamine anesthesia significantly altered the behavioral characteristics of experimental animals (

Table S3,

Figure 5). Administration of ketamine (control group) led to a significant increase in total motor activity (48862.22±3612.2 cm²/s

vs. 24175.01±2839.76 cm²/s in intact animals) and distance traveled by animals two days post-anesthesia. Notably, free distance increased both in absolute units (604.8±32.71 cm

vs. 59.37±26.31 cm in intact animals) and as a percentage of total motor activity (11.43±1%

vs. 1.43±0.61%), representing an approximately 10-fold increase. Significant aggression was observed in animals two days after anesthesia. Additionally, the control group exhibited a 1.86-fold increase in freezing episodes (529±27

vs. 284±35 units) and a 1.5-fold increase in immobility (429±27

vs. 284±35 units). These behavioral changes collectively indicate the development of anxiety and heightened excitability in animals following ketamine anesthesia.

Regarding the reference compounds, piracetam administration increased free distance compared to both intact and control groups (743.3±64.21 cm), but failed to reduce freezing episodes (378±65 units) or immobility (455±24 units), both remaining significantly higher than intact values. The number of wall rearings under piracetam remained elevated compared to the intact group (8±1 vs. 4±1 units), while short grooming acts remained at the control level (lower than intact values), and defecation frequency remained elevated (4±1 vs. 1±1 units in intact animals). These observations suggest that piracetam not only failed to reduce anxiety and fear following ketamine anesthesia but potentially exacerbated these states and the associated discomfort.

In contrast, fabomotizole significantly reduced free distance compared to control (245.32±18.23 cm vs. 604.8±32.71 cm), normalized immobility (334±77 units), and modestly reduced freezing episodes (432±42 vs. 529±27 units), though the latter remained significantly higher than intact values. However, fabomotizole did not normalize wall rearings, had minimal effects on high and low activity durations, and did not affect grooming behavior. These data indicate that fabomotizole partially reduces anxiety and fear after ketamine anesthesia but has limited impact on animal discomfort and cognitive activity.

Administration of tested compound in 10 mg/kg, namely 33 led to significant reductions in overall activity compared to the control group, though still elevated above intact levels (30321.33±1244.3 cm²/s). This group exhibited a pronounced alteration in activity structure, with a significant increase in immobility episodes (574±121 units). Compound 33 did not significantly reduce distance traveled but did decrease both high activity (9.33±1.22% vs. 15.12±1.63% in control) and low activity (36.21±2.33% vs. 47.11±4.22% in control and 61.71±7.08% in intact) durations. Animals displayed low mobility and preference for dark corners during testing, suggesting suppression of exploratory and cognitive activities. The number of center entries decreased (1 vs. 5 in control), potentially indicating either suppressed cognitive activity or persistent anxiety, despite reduced freezing episodes compared to control.

Compound 31 effectively reduced aggression following ketamine anesthesia while promoting active exploratory behavior. Animals receiving this compound showed significantly increased total activity compared to both control and intact groups (56177.4±1276.8 cm²/s). High activity duration was significantly increased (19.4±2.33%), suggesting enhanced cognitive engagement. The increased number of center entries (8 vs. 5 in control) and free rearings (4±1 vs. 2±1 units) further support improved exploratory behavior. However, the elevated free distance (622.3±34.3 cm), particularly in the context of increased high activity, may indicate somewhat inefficient exploratory patterns with excessive movements. Importantly, compound 31 significantly reduced anxiety markers, as evidenced by decreased freezing episodes (212±31 vs. 529±27 units), reduced immobility (274±21 vs. 429±27 units), increased center entries, and reduced defecation (1±1 vs. 5±1 units). These findings suggest a potential disinhibitory effect of compound 31.

Compounds 25, 26, and 32 demonstrated particularly favorable behavioral profiles. All three compounds effectively reduced post-ketamine aggression while normalizing total activity to near-intact levels. Each compound significantly normalized high activity duration compared to control, while compound 25 additionally increased low activity duration (64.22±2.12% vs. 47.11±4.22% in control), suggesting enhanced quality of exploratory and cognitive behaviors. All three compounds significantly reduced freezing episodes and immobility, indicating anxiolytic effects.

Notably, compounds 25, 26, and 32 significantly reduced free distance, suggesting improved efficiency of exploratory activity. The number of center entries normalized to intact levels (3 entries), further supporting normalized cognitive function. Animals receiving these compounds also exhibited significantly increased short (4±1, 4±1, and 5±1 units, respectively, vs. 1±1 in control) and extended grooming (3±1 units for all three vs. 1±1 in control), along with decreased defecation (1±1 units for all three vs. 5±1 in control), indicating reduced anxiety and aggression alongside increased comfort.

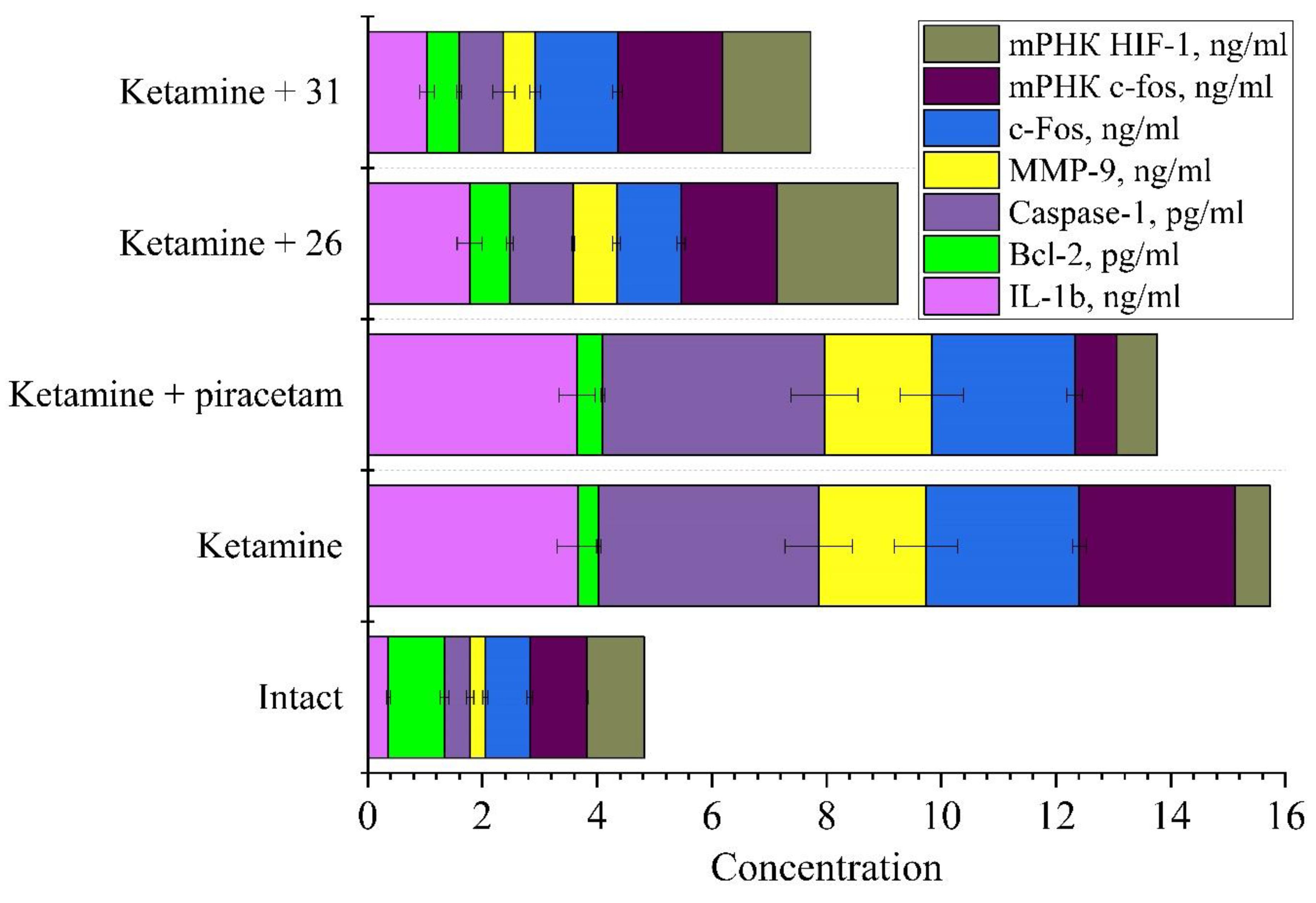

1.1.1. Study of Markers of Neuronal Damage

The experimental data presented in

Figure 6 (

Tables S4 and S5) provide valuable insights into the neurobiochemical changes induced by ketamine anesthesia and the potential neuroprotective effects of chosen two representatives, compounds

31 and

26, compared to the reference drug piracetam.

Inflammatory and apoptotic markers. Ketamine anesthesia significantly increased IL-1β concentration (approximately 11.8-fold) in the rat brain cytosolic fraction compared to intact animals. This substantial elevation indicates pronounced neuroinflammatory activation. Both compounds 31 and 26 demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties, reducing IL-1β levels by 72% and 51.5% respectively, compared to the control group. Notably, compound 31 showed superior anti-inflammatory efficacy. In contrast, piracetam failed to mitigate ketamine-induced IL-1β elevation, suggesting its limited anti-inflammatory capacity in this model.

The anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 was markedly reduced (by 63.4%) following ketamine administration, indicating compromised neuroprotective mechanisms. Both test compounds partially restored Bcl-2 levels, with compound 26 demonstrating greater efficacy (96.2% increase from control) compared to compound 31 (56.6% increase). Piracetam showed modest Bcl-2 restoration (25.1% increase), substantially less effective than the test compounds.

Inflammasome activation. Caspase-1, a key component of the inflammasome complex and indicator of pyroptotic cell death, was dramatically increased (8.5-fold) by ketamine anesthesia. Compounds 31 and 26 significantly attenuated this elevation, reducing levels by 79.7% and 71.3% respectively, with compound 31 showing slightly superior efficacy. Piracetam showed no effect on caspase-1 levels, suggesting its inability to modulate inflammasome activation.

Matrix metalloproteinase and neuronal activation. MMP-9, associated with blood-brain barrier disruption and neuroinflammation, increased 7.2-fold following ketamine administration. Both test compounds reduced MMP-9 levels, though the reduction did not reach the intact animal baseline. Piracetam showed no effect on MMP-9 elevation.

The neuronal activation marker c-fos increased 3.4-fold with ketamine anesthesia. Compounds 31 and 26 reduced c-fos protein levels by 46.1% and 58.1% respectively, with compound 26 showing greater efficacy. Piracetam minimally affected c-fos protein levels.

Gene expression analysis. The mRNA expression data from the CA1 hippocampal region revealed interesting patterns. Ketamine increased c-fos mRNA expression 2.7-fold, consistent with the protein level findings. Compounds 31 and 26 partially normalized c-fos transcription, reducing it by 32.5% and 38.4% respectively. Interestingly, piracetam reduced c-fos mRNA below intact animal levels, suggesting potential transcriptional suppression, that did not translate to proportional protein reduction.

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) mRNA was reduced by 38.9% following ketamine administration, indicating impaired hypoxic adaptation. Both test compounds not only restored but significantly elevated HIF-1 mRNA levels above intact baselines. Compound 26 showed superior efficacy, increasing HIF-1 mRNA 3.5-fold compared to control. Piracetam showed minimal effect on its ketamine-induced reduction.

1.1. Preliminary Structure-Activity Relationships from Experimental Findings

The experimental data revealed notable correlations between molecular structure and biological activity (

Table 4). Two key structural elements appeared to significantly influence the biological properties of the compounds:

1.1.1. Effect of Spiro-Junction Type

Compounds with cyclohexane spiro-junction (25 and 26) exhibited stabilizing effects on ketamine-induced behavioral alterations, with particularly effective normalization of exploratory behaviors. In neurobiochemical assays, compound 26 showed strong efficacy in restoring Bcl-2 levels and upregulating HIF-1 mRNA.

Compounds featuring N-methylpiperidine spiro-junction (31, 32, and 33) demonstrated varied activity profiles depending on their 2'-substituent. Notably, compound 31 exhibited pronounced effects on inflammatory markers, with superior reduction of IL-1β and caspase-1 levels.

1.1.1. Influence of 2'-Position Substituents

Different substituents at the 2'-position resulted in distinct biological profiles:

Cyclopropyl combined with N-methylpiperidine (compound 31) produced stimulatory and anxiolytic effects while demonstrating strong anti-inflammatory activity.

Cyclohexyl derivatives (compounds 26 and 32) consistently normalized ketamine-induced hyperactivity, with compound 26 showing exceptional ability to restore Bcl-2 levels and upregulate HIF-1 mRNA.

Adamantyl substitution (compound 33) resulted in a unique profile with sedative-like properties.

1.1.1. Behavioral and Biochemical Correlations

The compounds displaying the strongest anxiolytic effects (25, 26, and 32) also increased grooming behaviors, suggesting a link between reduced anxiety and comfort-associated behaviors. The normalization of locomotor activity by compound 26 correlated with its remarkable ability to upregulate HIF-1 mRNA, suggesting a potential connection between adaptive stress responses and behavioral normalization.

The compound with the strongest anti-inflammatory activity (31) showed pronounced anxiolytic effects while stimulating exploratory behavior, indicating a potential relationship between reduced neuroinflammation and improved cognitive function.

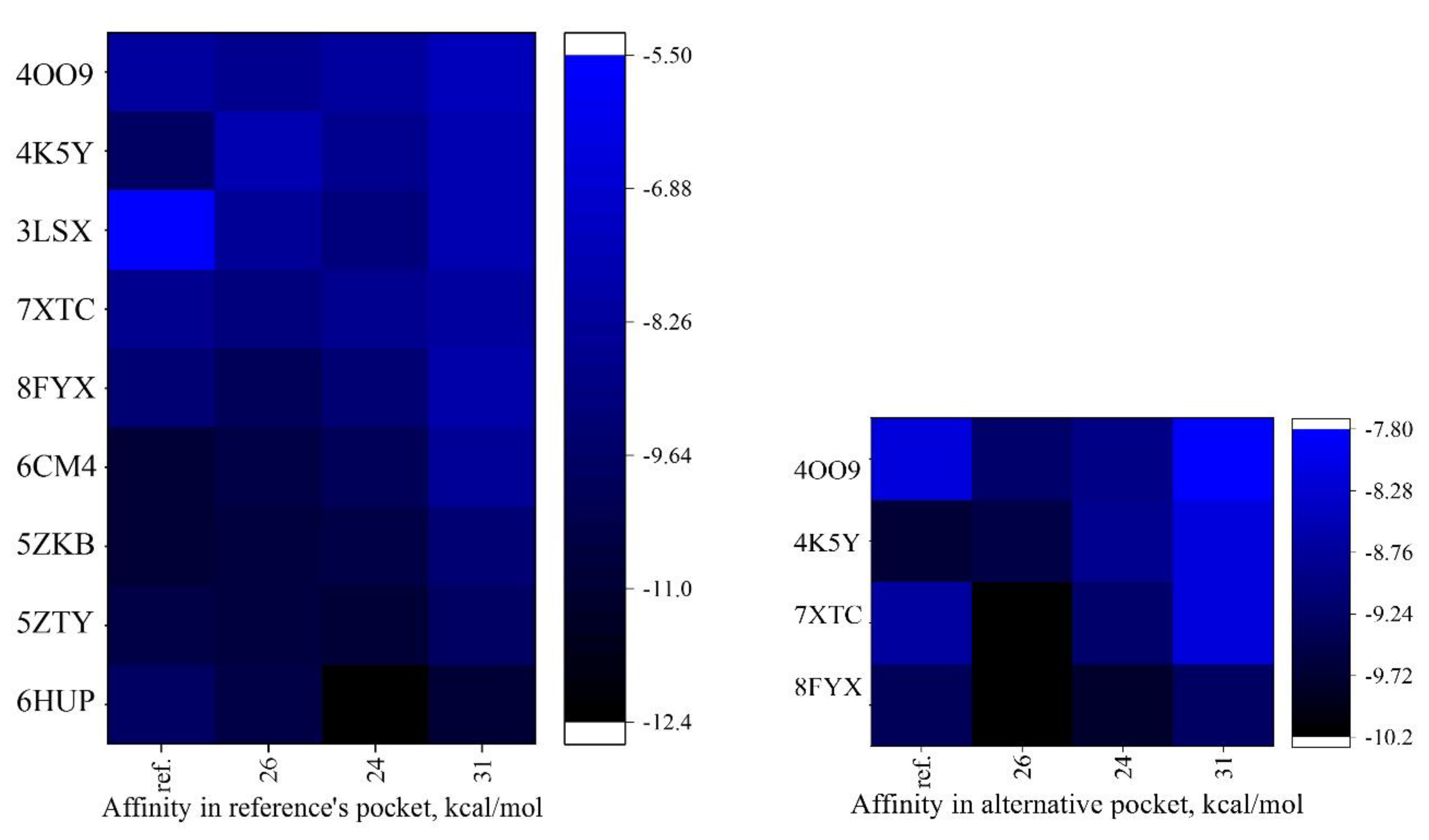

1.1. Molecular Docking Analysis of Receptor Interactions

1.1.1. Receptor Binding Profiles

Three representative compounds were selected for detailed receptor binding analysis based on their distinctive profiles: compound 24 (exceptional binding affinity in initial screening), 26 (balanced behavioral profile with HIF-1 upregulation), and 31 (strong anti-inflammatory activity).

Molecular docking studies were performed with key neuroreceptors including CB2 (5ZTY), GABA(A)R α1/β3/γ2L (6HUP), M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (5ZKB), D2 dopamine receptor (6CM4), serotonin receptors 5-HT1A (8FYX) and 5-HT7 (7XTC), CRF1R (4K5Y), GluA3 (3XSL), and mGluR5 (4OO9) (

Figure 7,

Tables S6-S14, Materials and methods).

The binding analyses revealed distinct profiles for each compound: 26 demonstrated balanced binding across multiple targets, with particularly strong affinity for M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (-10.7 kcal/mol) and GABA(A) receptors (-10.4 kcal/mol). Compound 31 showed generally lower binding affinities than compounds 24 and 26 across most targets, suggesting its biological activity may involve mechanisms beyond direct receptor interactions. And 24, despite not being tested in behavioral assays, exhibited exceptional binding to GABA(A) receptors (-12.4 kcal/mol), substantially exceeding the reference compound diazepam (-9.8 kcal/mol).

1.1.1. Analysis of Binding Interactions

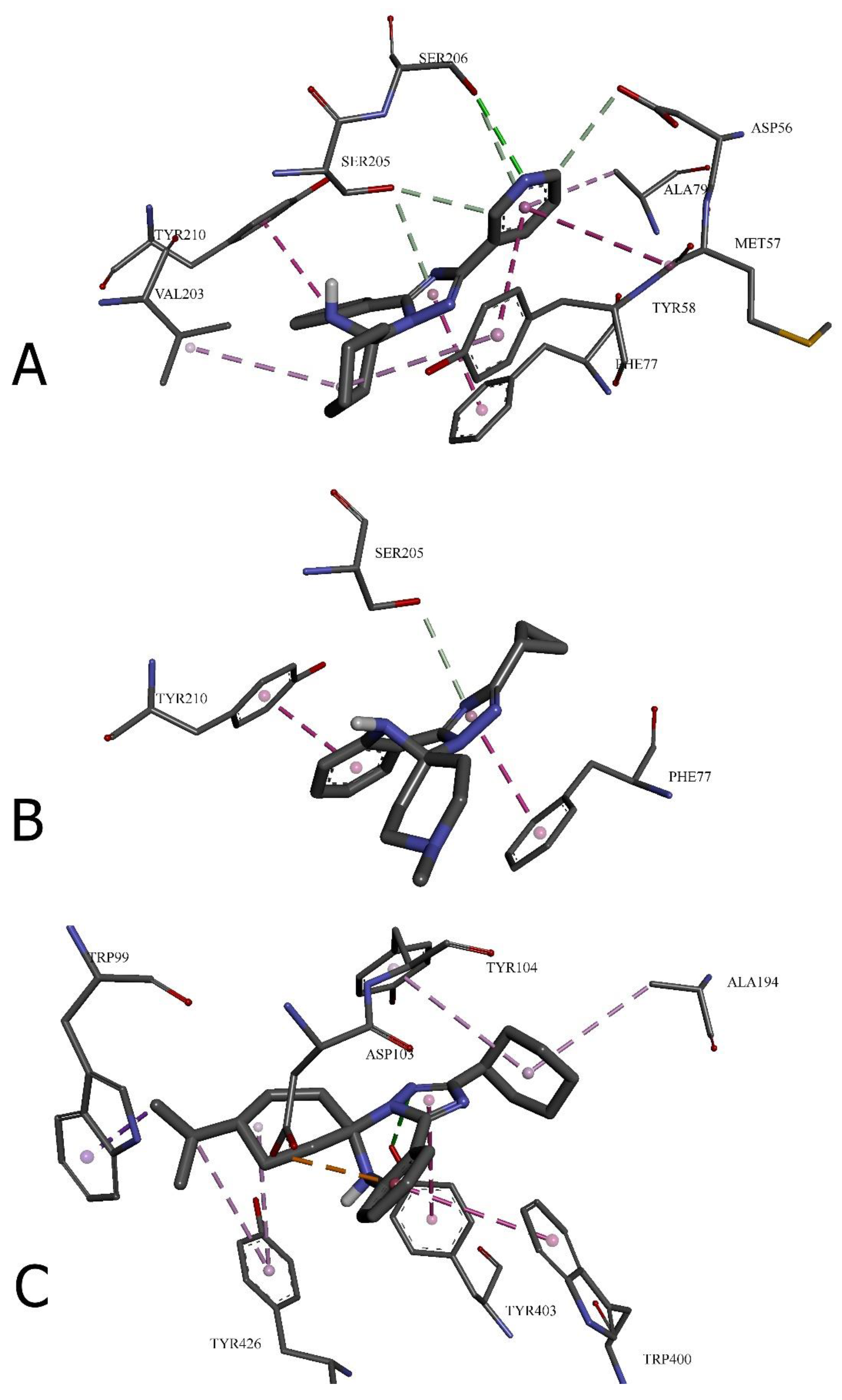

Detailed examination of binding modes (

Figure 8) revealed structure-specific interaction patterns:

Compound 24 formed multiple hydrogen bonds with the GABA(A) receptor, including a strong conventional hydrogen bond with SER206 (3.09 Å) and extensive hydrophobic contacts, particularly π-π stacked interactions with TYR58, TYR210, and PHE77.

Compound 31 displayed a more selective interaction profile with GABA(A) receptors, primarily featuring a π-donor hydrogen bond with SER205 (3.75 Å) and π-π stacked hydrophobic interactions with PHE77 and TYR210.

Compound 26 exhibited distinctive binding to the M2 muscarinic receptor, with a strong conventional hydrogen bond with TYR403 (2.88 Å) and a unique electrostatic π-anion interaction with ASP103. Its hydrophobic interaction network featured π-sigma interaction with TRP99 and π-π T-shaped interactions with TRP400 and TYR403.

1.1. Summary of Key Findings

This comprehensive investigation of novel spiro[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazoline derivatives has yielded several important findings. The compounds demonstrated promising binding profiles to key neuroreceptors, particularly GluA3 and GABA(A). Chemical synthesis via [5+1]-cyclocondensation produced the target compounds in good to excellent yields (67-95%), with full structural confirmation by spectroscopic methods.

In the ketamine-induced cognitive impairment model, compounds 25, 26, and 32 demonstrated superior anxiolytic and cognitive-normalizing properties compared to reference drugs piracetam and fabomotizole. Neurobiochemical analysis revealed that compounds 31 and 26 attenuated ketamine-induced neuroinflammation, apoptosis, and dysregulation of adaptive stress responses through apparently different mechanisms, with compound 31 showing stronger anti-inflammatory effects and compound 26 displaying greater influence on cell survival pathways.

Molecular docking studies revealed structure-specific binding profiles, with compound 24 showing exceptional GABA(A) binding, compound 26 displaying balanced multi-target engagement, and compound 31 exhibiting moderate receptor binding despite strong anti-inflammatory activity. These finding suggest that structural modifications to the spiro[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazoline scaffold can produce compounds with distinct pharmacological profiles targeting different aspects of ketamine-induced neurotoxicity.

The following discussion will explore the mechanistic implications of these findings, integrate the observed structure-activity relationships into a broader therapeutic context, and examine the potential applications and limitations of these compounds as novel neuroprotective agents.

3. Discussion

The molecular docking analysis revealed modest binding affinity of the novel compounds to the glutamate receptor GluA3, which is consistent with recent systematic reviews of racetam efficacy by Gouhie et al. (2024). These reviews found variable cognitive enhancement outcomes in clinical settings, suggesting that direct GluA3 interaction may not be the primary mechanism of action. This mechanistic complexity is further supported by recent analyses of nootropic compounds that highlight the diverse molecular pathways involved in cognitive enhancement (Jędrejko et al., 2023). Moreover, the comprehensive review by Jędrejko and colleagues also revealed that nootropic compounds can act through multiple mechanisms, including modulation of neurotransmitter systems, enhancement of neuronal metabolism, improvement of cerebral blood flow, and influence on neuroplasticity pathways.

The promising molecular docking results provided a strong rationale for proceeding with the synthesis of these compounds. Our synthetic efforts successfully delivered the target molecules in good to excellent yields (67-95%), enabling further characterization and biological evaluation. The [5+1]-cyclocondensation reaction proceeded efficiently in propan-2-ol with a catalytic amount of sulfuric acid, following a mechanism that included carbinolamine formation, elimination of water, and intramolecular cyclization (Pylypenko et al., 2024).

1.1. ADMET Profiles and Compound Selection

Following successful synthesis and structural confirmation of compounds 1-40, we proceeded to evaluate their safety profiles through comprehensive toxicity prediction studies. This critical step in the investigation aimed to identify compounds with optimal therapeutic indices for subsequent biological evaluation.

In comparison to reference drugs included in the analysis (piracetam and fabomotizole), the novel spiro[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazoline derivatives exhibited generally higher molecular weights and aromaticity, but comparable or lower rotatable bond counts and polar surface areas. Notably, fabomotizole contained significantly more of them (6) than any of the novel compounds (1-2), suggesting the designed derivatives may benefit from reduced conformational entropy penalties upon binding. Piracetam, a marketed nootropic drug included as a reference, failed to meet several Ghose criteria due to its small size (MW < 160) and low lipophilicity (WLOGP < -0.4). This observation suggests that compounds with minor violations may still represent viable drug candidates, particularly when strong target engagement is demonstrated, as marketed drugs do not always conform to all druggability filters, particularly those with unique physicochemical properties or specific mechanisms of action.

Interestingly, the reference compounds demonstrated markedly different solubility profiles. Piracetam exhibited exceptional water solubility across all three models (classified as "highly soluble" by ESOL and Ali), consistent with its low molecular weight and hydrophilic character. Fabomotizole showed moderate solubility comparable to many of the novel derivatives, supporting the potential pharmaceutical viability of compounds with similar solubility profiles. The latter also demonstrated BBB penetration. Piracetam, as expected from its highly hydrophilic nature, showed no BBB penetration, consistent with its well-established favorable safety profile, but limited brain exposure.

Based on the favorable safety and pharmacokinetic profiles identified through in silico analyses, five representative compounds (25, 26, 31-33) were selected for in-depth biological evaluation. These compounds were chosen to represent key low-toxicity structural variations within the library, allowing for meaningful structure-activity relationship determinations in physiologically relevant models.

1.1. Behavioral Effects and Neurobiochemical Mechanisms

The ketamine-induced cognitive impairment paradigm was selected as the primary screening model due to its well-characterized neurochemical profile and relevance to the target compounds' presumed mechanisms. Ketamine's antagonism of NMDA receptors produces reproducible cognitive deficits that share neurochemical similarities with various clinical conditions where cognitive improvement is desired.

Our behavioral analysis in the open field test following ketamine anesthesia revealed that compounds 25, 26, and 32 exhibited the most favorable profiles among all tested substances. These compounds effectively normalized behavioral parameters disrupted by ketamine, reducing anxiety and improving cognitive function without causing excessive stimulation or sedation. Compound 31 demonstrated potent anxiolytic and stimulatory effects but may promote somewhat inefficient exploratory behavior. Compound 33 showed mixed effects with some anxiolytic properties but potential cognitive suppression. The reference compounds piracetam and fabomotizole exhibited limited efficacy, with piracetam potentially exacerbating certain anxiety parameters and fabomotizole showing only partial anxiolytic effects.

The neurobiochemical analyses of compounds 31 and 26 provided mechanistic insights into their observed behavioral effects. Both compounds demonstrated substantial neuroprotective properties across multiple parameters compared to piracetam, but with different efficacy profiles suggesting distinct mechanistic pathways:

Compound 31 showed superior anti-inflammatory and anti-inflammasome activity, as evidenced by greater reductions in IL-1β and caspase-1 levels, suggesting potent modulation of innate immune responses in the brain. Compound 26 demonstrated stronger effects on anti-apoptotic protein restoration and HIF-1 expression, indicating potentially greater influence on cell survival pathways and hypoxic adaptation.

Piracetam showed limited efficacy across most parameters, with modest effects only on Bcl-2 levels and c-fos transcription, consistent with its known mild neuroprotective profile. The differential regulation of HIF-1 by the test compounds is particularly noteworthy, as it suggests potential enhancement of adaptive hypoxic responses that may confer broader neuroprotection beyond inflammatory modulation.

These neurobiochemical findings align with established literature on ketamine-induced neurotoxicity. Ketamine-induced NMDA receptor hyperstimulation triggers excessive Ca²⁺ influx, initiating a cascade of pathological events including reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, neuroinflammation, and neuroapoptosis (Xia et al., 1996; Simões et al., 2018). This mechanism is consistent with ketamine anesthesia precipitating postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD), characterized by anxiety and cognitive impairments stemming from neuroapoptotic processes. Particularly compelling is the dose-dependent apoptotic neurodegeneration observed in immature mouse brains following ketamine exposure, suggesting developmental vulnerability to anesthetic neurotoxicity (Behrooz et al., 2024).

The neuroapoptotic pathway appears intricately linked to ketamine-induced c-fos expression across multiple brain regions. Our findings of elevated c-fos mRNA expression in the CA1 hippocampal region corroborate the previous observations of increased c-fos-positive cell density following ketamine anesthesia (Belenichev et al., 2021) and align with independent reports in the literature (Zhang et al., 2022; Massara et al., 2016), establishing a consistent pattern of ketamine-induced neuronal activation in hippocampal structures critical for memory formation.

POCD pathophysiology extends beyond neuronal activation to include enhanced transcription and expression of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, alongside microglial activation within the hippocampus. A pivotal finding in the study concerns ketamine's enhancement of caspase-1 expression, which not only elevates TNF-α and IL-1β levels but also initiates pyroptosis - a distinct form of programmed cell death. Caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis emerges as a significant pathway involved in mitochondria-related apoptosis underlying ketamine-induced hippocampal neurotoxicity (Ye et al., 2018).

Further exacerbating these pathological processes, ketamine-induced matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) expression amplifies both neuroapoptosis and neuroinflammation, potentially through blood-brain barrier disruption (Wu et al., 2020). The molecular basis of ketamine neurotoxicity further involves significant reduction in anti-apoptotic protein (Bcl-2) expression, increased pro-apoptotic protein Bax expression, and stimulated cytochrome-c release from mitochondria in primary cortical neurons (Lei et al., 2012). Our investigation reveals that anesthetic-induced neuroapoptosis and cognitive dysfunction are associated with suppression of protective proteins HSP70 and HIF-1 expression (Belenichev et al., 2023), with decreased HIF-1 expression specifically documented in this study.

1.1. Structure-Activity Relationships

The integration of behavioral, neurobiochemical, and molecular docking data reveals comprehensive structure-activity relationships that provide valuable insights for future drug development (

Table 4).

1.1.1. Influence of Spiro-Junction Type

The spiro-junction (cyclohexane vs. N-methylpiperidine) appears to dictate not only behavioral outcomes but also specific neurobiochemical pathways:

Cyclohexane spiro-junction (compounds 25 and 26) confers stabilizing effects on ketamine-induced behavioral alterations. Neurobiochemically, compound 26 demonstrated superior efficacy in Bcl-2 restoration and HIF-1 upregulation, suggesting that this structural element may preferentially modulate cell survival pathways and hypoxic adaptation mechanisms rather than direct anti-inflammatory actions. Cyclohexane-based spirocycles (compounds 24 and 26) generally confer stronger receptor binding affinities than the N-methylpiperidine spirocycle (compound 31).

N-methylpiperidine spiro-junction (compounds 31, 32, and 33) yields diverse activity profiles that strongly depend on the 2'-substituent. The basic nitrogen atom in the piperidine ring may enhance compound 31's anti-inflammatory properties, as evidenced by its superior reduction of IL-1β and caspase-1 levels. This suggests that the N-methylpiperidine scaffold may facilitate interactions with inflammatory mediators or their regulatory pathways, despite reduced receptor binding.

1.1.1. Impact of 2'-Position Substituents

The 2'-position substituent critically determines both behavioral and neurobiochemical profiles:

Pyridin-3-yl substituent (24): substantially enhances GABA(A) receptor binding (-12.4 kcal/mol vs. -9.8 kcal/mol for diazepam), suggesting strong anxiolytic potential. Improves glutamate receptor binding, indicating possible cognitive enhancement properties. The nitrogen-containing aromatic ring likely forms additional hydrogen bonds within binding pockets, as evidenced by the strong conventional hydrogen bond with SER206 (3.09 Å) and multiple hydrophobic interactions.

Cyclohexyl substituent (26): provides balanced binding across multiple targets, correlating with its comprehensive neuroprotective profile. The conformational flexibility of the cyclohexyl group may allow adaptable binding to diverse receptor architectures. This structural feature appears optimal for HIF-1 upregulation and Bcl-2 restoration, suggesting enhanced cell survival mechanism engagement. Its strong binding to the M2 muscarinic receptor (-10.7 kcal/mol) is notable and may contribute to its balanced cognitive effects.

Cyclopropyl substituent (31): less favorable for direct receptor binding, particularly at dopamine and serotonin receptors. However, this structural feature appears to enhance anti-inflammatory and anti-inflammasome activity, suggesting specific interactions with inflammatory pathways. The compact, rigid cyclopropyl group may facilitate interactions with specific modulators of inflammatory cascades rather than neurotransmitter receptors.

Adamantyl substitution (33): the adamantyl-piperidine derivative displays a unique sedative-like profile. While not directly examined in the neurobiochemical analyses, its structural properties suggest it may have distinct effects on neuronal signaling, possibly through enhanced blood-brain barrier penetration or interaction with sedation-mediating receptors.

1.1.1. Behavioral Markers and Neurobiochemical Correlates

Self-grooming behavior and neuroinflammation: compounds 25, 26, and 32 significantly increased both short and extended grooming behaviors. Both compounds 26 and 31 (examined in the neurobiochemical analyses) reduced IL-1β and caspase-1 levels, suggesting that attenuation of neuroinflammation might contribute to normalized grooming patterns. The differential effects on c-fos expression (with compound 26 showing greater reduction) may further explain the nuanced behavioral differences between these compounds.

Locomotor activity and HIF-1 expression: the normalization of locomotor activity observed with compound 26 correlates with its remarkable ability to upregulate HIF-1 mRNA. HIF-1 plays a critical role in neural adaptation to stress conditions, and its enhanced expression may contribute to improved behavioral recovery through optimized neuronal metabolism and resilience.

1.1. Molecular Mechanisms and Target Hypotheses

The molecular docking analyses provide mechanistic insights into the receptor binding profiles that may underlie the observed neurobiochemical and behavioral effects. Our analysis of binding to multiple neuronal targets (

Figure 7,

Table S6) revealed distinct binding patterns for different structural classes.

The differential effects on inflammatory markers (IL-1β, caspase-1), apoptotic regulators (Bcl-2), and adaptive response factors (HIF-1) suggest multiple molecular targets for these compounds:

Compound 31's superior anti-inflammatory and anti-inflammasome activity suggests potential interaction with inflammasome components (NLRP3, ASC) or upstream regulators. Its moderate binding to GABA(A) receptors (-10.8 kcal/mol) may contribute to its anxiolytic effects.

Compound 26's pronounced effect on Bcl-2 and HIF-1 suggests possible modulation of mitochondrial function or hypoxia-sensing pathways. Its balanced binding across multiple receptors, particularly M2 muscarinic (-10.7 kcal/mol) and GABA(A) (-10.4 kcal/mol), correlates with its comprehensive neuroprotective profile.

Compound 24's exceptional binding to GABA(A) receptors (-12.4 kcal/mol) suggests it may have strong anxiolytic properties, though this was not directly evaluated in the behavioral studies.

The interplay between glutamatergic and GABAergic neurotransmission critically influences cognitive behaviors affected by ketamine. Post-ketamine activation of specific GABAergic pathways beneficially impacts spontaneous motor behavior, environmental habituation, and spatial learning in experimental paradigms. This suggests a potential shift in GABAergic signaling from receptor-mediated effects toward neurometabolic functions, particularly energy metabolism and mitochondrial processes (Belenichev et al., 2025; Farahmandfar et al., 2017; Davidson and deGraaff, 2013; Lisek et al., 2022).

Our data align with findings that modulation of serotonergic signaling - specifically 5-HT1A receptor blockade coupled with 5-HT2A receptor activation - reduces hippocampal apoptosis and attenuates anxiety, motor impairments, and environmental habituation deficits induced by various pharmacological agents (Shahidi et al., 2019; Pham and Gardier, 2019). The novel compounds investigated here, possessing affinity for GABA and specific serotonin receptor subtypes, appear to interrupt the cascade of adverse molecular and biochemical reactions following ketamine administration.

1.1. Multi-Target Engagement and Polypharmacology

The integration of molecular docking, neurobiochemical, and behavioral data suggests a complex mechanistic framework for these compounds:

Multi-target engagement hypothesis: the balanced binding profiles across multiple receptors, particularly for compounds 24 and 26, align with contemporary understanding of effective cognitive enhancement requiring engagement of complementary pathways rather than strong interaction with a single receptor type, as highlighted by Jędrejko et al. (2023).

Divergent primary mechanisms:

26 appears to function primarily through enhanced cell survival pathways (Bcl-2 restoration) and adaptive responses (HIF-1 upregulation), facilitated by balanced receptor engagement.

31 primarily modulates inflammatory pathways (IL-1β and caspase-1 reduction) with moderate receptor interaction, suggesting its mechanism involves signaling cascades downstream of receptor activation.

24's strong GABA(A) and glutamate receptor binding suggests direct neurotransmitter system modulation as its primary mechanism.

Structure-dependent signaling pathway activation:

Cyclohexane spirocycle + cyclohexyl substituent (26): preferentially activates cell survival and hypoxic adaptation pathways.

N-methylpiperidine spirocycle + cyclopropyl substituent (31): primarily modulates inflammatory signaling cascades.

Cyclohexane spirocycle + pyridin-3-yl substituent (24): directly modulates inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmission.

1.1. Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

This integrated analysis provides rational guidance for therapeutic applications and further optimization:

Target-specific compound selection:

For anti-anxiety applications with mild sedation: compound 24 (strongest GABA(A) binding).

For neuroprotection with balanced cognitive effects: compound 26 (optimal Bcl-2 and HIF-1 modulation).

For anti-neuroinflammatory applications with anxiolytic properties: compound 31 (superior anti-inflammatory profile).

Structural optimization approaches:

For enhanced GABA(A) binding: incorporate pyridin-3-yl substituent at 2'-position.

For balanced neuroprotection: utilize cyclohexyl substituent at 2'-position with cyclohexane spirocycle.

For anti-inflammatory potency: explore modifications of the cyclopropyl-piperidine scaffold.

Hybrid compound development:

Compounds incorporating features of both 26 and 31 might yield candidates with dual neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties.

Hybrids of 24 and 26 could enhance both direct GABA(A) modulation and cell survival pathway activation.

Several promising research directions emerge from this work:

Receptor binding assays: experimental validation of the computational docking predictions through radioligand binding studies to confirm target engagement.

Pathway-specific investigations: examination of the effects of these compounds on specific signaling pathways, particularly inflammasome components, HIF-1 regulatory mechanisms, and Bcl-2 associated proteins.

Structure-based design: utilization of the identified structure-activity relationships to design next-generation compounds with enhanced target selectivity or multi-target profiles.

Extended behavioral evaluation: comprehensive behavioral assessment of compound 24 to validate its predicted anxiolytic potential based on exceptional GABA(A) binding.

Dose-response relationships: investigation of dose-dependent effects on receptor binding, neurobiochemical markers, and behavioral outcomes to establish optimal therapeutic windows.

1.1. Limitations of the Study

There are several key limitations that should be acknowledged:

Methodological limitations:

Single-dose testing: the in vivo evaluation tested compounds at only one dose, limiting understanding of dose-response relationships and therapeutic windows.

Limited timeframe: the study focused on acute effects following ketamine administration rather than long-term outcomes.

Protein-level validation: while the study provided valuable mRNA expression data for key markers (c-fos and HIF-1), we acknowledge the absence of protein-level validation through Western blot analysis for some markers.

Absence of preliminary cell studies: the research proceeded directly to in vivo models without initial evaluation in relevant cell lines.

Single animal model: using only the ketamine-induced cognitive impairment model may limit generalizability to other types of cognitive disorders.

Sample size consideration: the study uses n=6-10 animals per group, which is relatively small.

Mechanistic limitations:

Indirect target validation: while molecular docking predicted binding to various receptors, direct receptor binding assays were not performed to confirm actual engagement with proposed targets.

Incomplete pathway analysis: the neurobiochemical investigation focused on selected markers but did not comprehensively analyze all potential pathways involved in ketamine-induced neurotoxicity.

Limited pharmacokinetic data: the study lacks information on blood-brain barrier penetration, central nervous system exposure, or metabolic stability of the compounds, relying primarily on in silico predictions.

Translational limitations:

Sex differences unexplored: the study does not address potential sex-based differences in drug responses.

Limited behavioral assessment: the behavioral evaluation relied primarily on the open field test.

Species limitation: using only rats limits extrapolation to human conditions.

Age considerations: the study used adult rats but did not explore how these compounds might affect developing or aging brains.

Technical limitations:

Structural characterization gaps: X-ray crystallography confirmation of the three-dimensional structure was not included.

Manufacturing considerations: the synthesis, while successful at laboratory scale, may face challenges in scale-up for potential clinical development.

Despite these limitations, the study provides a valuable foundation for the development of novel neuroprotective agents. The comprehensive neuroprotective profile of compounds 31 and 26 against multiple ketamine-induced pathological processes presents promising therapeutic potential for preventing or treating anesthetic-induced neurocognitive dysfunction. Their differential mechanistic actions on inflammatory, apoptotic, and adaptive pathways warrant further investigation in diverse anesthetic exposure paradigms and potential clinical translation.

4. Materials and Methods

1.1. Molecular Docking

CB-Dock2 (Liu et al., 2022; CB-Dock2, 2025), a protein-ligand auto blind docking tool, that inherits the curvature-based cavity detection procedure with AutoDock Vina, was used for calculations of tested substances’ affinity to 10 macromolecules from RCSB Protein Data Bank, namely 5ZTY (Ivy et al., 2020; RCSB PDB - 5ZTY, 2025), 6HUP (Frans et al., 2025; RCSB PDB - 6HUP, 2025), 5ZKB (Suno et al., 2018; RCSB PDB - 5ZKB, 2025), 6CM4 (Wang et al., 2018; RCSB PDB - 6CM4, 2025), 8FYX (Li et al., 2012, RCSB PDB - 8FYX, 2025), 7XTC (Hagan et al., 2000; RCSB PDB - 7XTC, 2025), 3LSX (Ahmed and Oswald, 2010; RCSB PDB - 3LSX, 2025), 4K5Y (Seymour et al., 2003, RCSB PDB - 4K5Y, 2025), and 4OO9 (Doré et al., 2014; RCSB PDB - 4OO9, 2025) (

Supplementary Materials,

Table S1, S2, S6-S14). And the following substances were used as the references: JWH-133: (6

aR,10

aR)-6,6,9-trimethyl-3-(2-methylpentan-2-yl)-6

a,7,10,10

a-tetrahydrobenzo[

c]chromene; diazepam: 7-chloro-1-methyl-5-phenyl-3

H-1,4-benzodiazepin-2-one; AFDX-384:

N-[2-[2-[(dipropylamino)methyl]piperidin-1-yl]ethyl]-6-oxo-5

H-pyrido[2,3-

b][

1,

4]benzodiazepine-11-carboxamide; etrumadenant: 3-[2-amino-6-[1-[[6-(2-hydroxypropan-2-yl)pyridin-2-yl]methyl]triazol-4-yl]pyrimidin-4-yl]-2-methylbenzonitrile; risperidone: 3-[2-[4-(6-fluoro-1,2-benzoxazol-3-yl)piperidin-1-yl]ethyl]-2-methyl-6,7,8,9-tetrahydropyrido[1,2-

a]pyrimidin-4-one; buspirone: 8-[4-(4-pyrimidin-2-ylpiperazin-1-yl)butyl]-8-azaspiro[4.5]decane-7,9-dione; SB-269970: 3-[[(2

R)-2-[2-(4-methyl-1-piperidinyl)ethyl]-1-pyrrolidinyl]sulfonyl]phenol; pramiracetam:

N-[2-[di(propan-2-yl)amino]ethyl]-2-(2-oxopyrrolidin-1-yl)acetamide; CP-154,526:

N-butyl-

N-ethyl-2,5-dimethyl-7-(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)-7

H-pyrrolo[3,2-

e]pyrimidin-4-amine; mavoglurant: methyl (3

aR,4

S,7

aR)-4-hydroxy-4-[(3-methylphenyl)ethynyl]octahydro-1

H-indole-1-carboxylate (

Figure 1).

1.1. Synthesis

Melting points were measured in open capillary tubes using a «Mettler Toledo MP 50» apparatus (Columbus, USA). Elemental analyses (C, H, N) were conducted on an ELEMENTAR vario EL cube analyzer (Langenselbold, Germany), with the results for elements or functional groups deviating by no more than ± 0.3% from the theoretical values. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra (500 MHz) were obtained on a Varian Mercury 500 spectrometer (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA), using TMS as an internal standard in a DMSO-d6 solution. LC-MS data were acquired using a chromatography/mass spectrometric system comprising the high-performance liquid chromatography «Agilent 1100 Series» (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, USA) equipped with a diode-matrix detector and mass-selective detector, «Agilent LC/MSD SL» (Agilent, Palo Alto, USA), with atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI).

The starting substances a were obtained according to the previously described method and physicochemical constants that correspond to the literature data (Kholodnyak et al., 2016; Shabelnyk et al., 2025). Synthetic studies were carried out according to general approaches using reagents from «Merck» (Darmstadt, Germany), «Sigma-Aldrich» (Missouri, USA) and «Enamine» (Kyiv, Ukraine).

General procedure for the synthesis of 2′-R-6'H-spiro(cycloalkyl-, heterocyclyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazolines (1-40):

To a solution of 10 mmol of the corresponding [2-(3-R-1H-1,2,4-triazolo-5-yl)phenyl]amine (a) in 10 ml of propanol-2 (or ethanol, propanol-1) was added 10 mmol of the corresponding ketone (cyclobutanone, cyclopentanone, cyclohexanone, 4-(tert-butyl)cyclohexan-1-one, 1-methyl-piperidone-4) and 2 drops of concentrated sulfate acid. The reaction mixture is left at room temperature for 24 hours (method A) or boiled for up to 6 hours (method B). Cool, pour into a 10% sodium acetate solution. The resulting precipitate is filtered and dried. Crystallize from methanol if necessary.

Synthesized compounds are white crystalline substances insoluble in water, soluble in alcohols, dioxane and DMF. Spectral data are found in the

Supplementary Materials.

1.1. Toxicity Studies

A virtual lab of website ProTox-II was used for the prediction toxicities of molecules (Banerjee et al., 2024; ProTox-II, 2025, Antypenko et al, 2025b). It incorporates molecular similarity, fragment propensities, most frequent features and (fragment similarity-based CLUSTER cross-validation) machine-learning, based a total of 33 models for the prediction of various toxicity endpoints such as acute toxicity, hepatotoxicity, cytotoxicity, carcinogenicity, mutagenicity, immunotoxicity, adverse outcomes (Tox21) pathways and toxicity targets. All methods, statistics of training set as well as the cross-validation results can be found at their website.

1.1. SwissADME Analysis

The SwissADME virtual laboratory was utilized to calculate the physicochemical descriptors and predict the ADME parameters, pharmacokinetic properties and drug-likeness (Daina et al., 2017; SwissADME, 2025; Antypenko et al, 2025b). The fundamental approaches and methodology underlying SwissADME, a free web-based tool designed for evaluating pharmacokinetics and drug-likeness, are detailed in the scientific literature.

1.1. Biological Assay

1.1.1. Animals

The studies were performed on a sufficient number of animals (a total of 54 rats: n = 6 intact, 6 control, and 42 experimental rats divided into groups III-IX), and all manipulations were carried out in accordance with the regulation on the use of animals in biomedical experiments (Council Directive 86/609/EEC) and the "General Ethical Principles of Animal Experiments" (EEC, 1986). (Directive 2010/63/EU). The ZSMPhU Commission on Bioethics decided to adopt the experimental study protocols and outcomes (Protocol № 3, dated March 22, 2024). The design, execution, analysis, and reporting of the animal experiments in this study adhere to the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines.

The research was conducted on Wistar rats aged 6 months with a weight of 220-290 g, obtained from the breeding facility of the Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology of the Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine. The quarantine (acclimatization) period for all animals was 14 days.

The animals were housed in polycarbonate cages measuring 550×320×180 mm with galvanized steel lids measuring 660×370×140 mm and glass drinking bottles. Each cage contained 5 rats. Every cage was labeled with information including the study number, species, sex, animal numbers, and dose. The cages were placed on shelves according to dosage levels and cage numbers indicated on the labels.

All rats were fed ad libitum a standard laboratory animal diet supplied by "Phoenix" company, Ukraine. Water from the municipal water supply (after reverse osmosis and UV sterilization) was provided without restriction. Alder (Alnus glutinosa) sawdust, previously treated by autoclaving, was used as bedding.

During the quarantine period, each animal was examined daily (behavior and general condition), and the animals were observed in their cages twice daily (for morbidity and mortality). Before starting the experiment, animals that met the inclusion criteria were randomly assigned to groups. Animals that did not meet the criteria were excluded from the experiment during quarantine.

The cages with animals were placed in separate rooms. Light regime: 12 hours light, 12 hours darkness. Air temperature was maintained within 19-25°C, and relative humidity at 50-70%. Temperature and humidity were recorded daily. Ventilation was set to provide approximately 15 room volumes per hour. The experimental animals were maintained on the same diet under standard vivarium conditions.

1.1.1. Behavioral Tests

Before conducting the experiment in the behavioral apparatus, the rats were randomly divided into nine groups: intact (I), control (II), and experimental (III-IX) groups, totaling n = 54 rats (n = 6 intact, 6 control, and 42 experimental rats).

The control (II) and experimental (III (piracetam), IV (fabomotizole), V (substance 33), VI (31), VII (32), VIII (25), IX (26) groups received ketamine anesthesia through intraperitoneal administration of 100 mg/kg ketamine, in the form of an injection solution ("Ketamin," injection solution, 25 mg/ml, batch No. PC 04150085099096, manufacturer "Pfizer," Germany) (Duman et al., 2012; Zanos and Gould, 2018; Krystal et al., 2019).

After the animals recovered from ketamine anesthesia, the investigated compounds were administered to the experimental (V-IX) groups once at a dose of 10 mg/kg intraperitoneally as a suspension in Tween-80.

As reference drugs, the following ones were used. Piracetam was administered to rats in group III once at a dose of 250 mg/kg intraperitoneally as an injection solution ("Piracetam", injection solution in ampoules, 200 mg/ml, batch No. UA/0054/01/01, manufacturer UCB Pharma S.A., Belgium). Fabomotizole was administered to rats in group IV once at a dose of 10 mg/kg intraperitoneally as an extemporaneous aqueous solution ("Afobazole", 5-ethoxy-2-[2-(morpholino)ethyl]thio]-benzimidazole, CAS:173352-21-1, manufacturer Sigma Aldrich, USA).

The intact group (I group) received a single intraperitoneal dose of physiological saline at a rate of 1 ml per 100 g of weight. The control group (II group), after ketamine administration, also received a single intraperitoneal dose of physiological saline at the same dosage.

The determination of motor and exploratory activity was conducted using the "Open Field" method with a custom-made arena measuring 80×80×35 cm. Experiments were performed in a well-lit room in complete silence. During the experiments, the influence of external and internal visual, olfactory, and auditory stimuli was excluded.

The animal was placed near the middle of one side facing the wall, after which it was allowed to move freely around the arena for 8 minutes. We evaluated the following parameters:

Total distance traveled (cm)

Overall motor activity (cm²/s)

Activity structure (high activity, low activity, inactivity, %)

Number of freezing episodes and entries into the center

Distance traveled near the wall (cm) and in the central area of the arena (cm, %)

Vertical exploratory activity (number of rearing on hind limbs near the wall and in the center)

Number of short and long grooming events

Number of defecation and urination acts

The assessment of animal behavior was conducted by a laboratory assistant who was unaware of the animal's specific experimental group assignment. Image capture and recording were performed using a SSC-DC378P color video camera (Sony, Japan). Video file analysis was conducted using Smartv 3.0 software (Harvard Apparatus, USA) (Belenichev et al., 2024b).

Our behavioral assessment employed nuanced parameters in the "open field" test, analyzing total activity, high activity, and inactivity durations. This approach provides insights into the structural components of locomotor behavior that correlate with neurobiological changes. Total activity represents comprehensive movement patterns, while the computer-assisted analysis distinguishes between high activity and inactivity states. Activation pattern alterations in the amygdala - a limbic structure associated with fear and anxiety - differentiate between low and high activity states during "open field" testing, connecting behavioral outcomes to contextual fear conditioning. These behavioral manifestations correlate with c-fos expression levels in the amygdala and broader limbic system.

Elevated high activity percentage indicates reduced anxiety and fear responses, reflecting improved psycho-emotional status. Notably, significant increases in high activity and center entries can indicate pharmacological side effects, such as the agitated disorientation observed with amphetamine and certain antidepressants. Conversely, increased low activity and inactivity percentages directly correlate with depressive-like behaviors. Inactivity specifically associates with dopaminergic deficiency or reduced receptor affinity in the mesolimbic system. Activity structure alterations also reflect disruptions in serotonergic signaling, particularly in 5HT1A/5HT2A receptor ratios.

Fear and depression manifest behaviorally as thigmotaxis - extended time spent near the apparatus walls where lighting is diminished. The "freezing" parameter quantifies anxiety responses, while "free distance" and "center entries" demonstrate cognitive activity and absence of anxiety, fear, and depression.

1.1.1. Removal of Animals from the Experiment

Animal decapitation using ether anesthesia was performed on the 15th day after the termination of the experiment from 9:00 to 11:00.

At the end of the experiment, 3 hours after the administration of the last dose of the drug, the animals were decapitated using ether anesthesia and the brain was removed.

1.1.1. Preparation of Biological Material

Blood was quickly removed from the brain, which was then separated from the meninges, and the studied pieces were placed in liquid nitrogen. Then they were crushed in liquid nitrogen to a powder-like state and homogenized in a 10-fold volume of medium at a temperature of (+2°C), which contained (in mmol): sucrose - 250 mM, tris-HCl buffer - 20 mM, EDTA - 1 mM (pH 7.4). At a temperature of (+4°C), the cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were separated by differential centrifugation using a Sigma 3-30k refrigerated centrifuge (Germany). To purify the fraction from large cellular fragments, preliminary centrifugation was performed for 7 minutes at 1000g, and then the supernatant was re-centrifuged for 20 minutes at 17000g. The supernatant was decanted and stored at -80°C. A portion of the brain was placed in Bouin's fixative for 24 hours. After the standard procedure of tissue dehydration and its impregnation with chloroform and paraffin, the brain pieces were embedded in paraplast (MkCormick, USA). Serial histological sections of the CA-1 zone of the hippocampus with a thickness of 5 μm were prepared on a Microm-325 rotational microscope (Microm Corp., Germany), which after processing with o-xylol and ethanol were used for real-time PCR research.

1.1.1. Polymerase Chain Reaction in Real Time

To determine the expression level of c-fos mRNA and HIF-1S mRNA, a CFX96 RT-PCR Detection Systems amplifier (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., USA) was used. In our studies, for PCR under time conditions, there were a set of reagents manufactured by Sintol, russia (No. R-415) that were used. The amplification composition included SYBR Green dye, SynTaq DNA polymerase with antibodies inhibiting enzyme activity, 0.2 μl each of forward and reverse-specific primers, dNTP-deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 1 μl of matrix (cDNA). The reaction mixture was adjusted to a total volume of 25 μl by adding deionized water. Specific primer pairs (5’-3’) for analysis of the studied and reference genes were selected using the PrimerBlast software (

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast) and manufactured by ThermoScientific, USA. Amplification took place under the following conditions: initiated denaturation 95°C – 10 min; further, 50 cycles: denaturation – 95°С, 15 s., primer annealing – 58–63°С, 30 s., and elongation – 72°С, 30 s. Registration of fluorescence intensity occurred automatically at the end of the elongation stage of each cycle through the automatic SybrGreen channel. The actin and beta (Actb) gene were used as a reference gene to determine the relative value of changes in the expression level of the studied genes.

1.1.1. Statistical Analysis

Experimental data were statistically analyzed using “StatisticaR for Windows 6.0” (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA, AXXR712D833214FAN5), “SPSS16.0”, and “Microsoft Office Excel 2010” software. Prior to statistical tests, we checked the results for normality (Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests). In the normal distribution, intergroup differences were considered statistically significant based on the parametric Student’s t-test. If the distribution was not normal, the comparative analysis was conducted using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test. To compare independent variables in more than two selections, we applied ANOVA dispersion analysis for the normal distribution and the Kruskal–Wallis test for the non-normal distribution. To analyze correlations between parameters, we used correlation analysis based on the Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficient. For all types of analysis, the differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05 (95%).

5. Conclusions

This study comprehensively examines the development of novel 2'-R-6'H-spiro(cycloalkyl-, heterocyclyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazolines as potential neuroprotective agents for cognitive and behavioral disorders following ketamine anesthesia. Through integrated computational, synthetic, and biological approaches, we have identified several promising compounds with superior profiles compared to established reference drugs.

The rational design strategy, incorporating key structural features from clinically validated pharmacophores, yielded a focused library of compounds with optimized drug-like properties. Molecular docking studies revealed that most compounds demonstrated significant affinity for multiple targets involved in neuroprotection and cognition, particularly with the glutamate receptor GluA3, with binding energies exceeding those of reference compounds piracetam and pramiracetam.

In silico ADMET evaluations indicated favorable toxicity profiles and drug-likeness parameters for the selected compounds, with most derivatives meeting established criteria for bioavailability and blood-brain barrier permeation. In vivo behavioral studies using the ketamine-induced cognitive impairment model revealed that compounds 25, 26, and 32 demonstrated superior efficacy in normalizing behavioral parameters, reducing anxiety-like behaviors, and improving cognitive function compared to piracetam and fabomotizole. Notably, compounds 31 and 26 exhibited distinct neurobiochemical profiles, with compound 31 showing superior anti-inflammatory properties and compound 26 demonstrating enhanced effects on cell survival pathways.

Detailed structure-activity relationship analyses established that, the spiro-junction significantly influences pharmacological activity, with cyclohexane spirocycles (25, 26) promoting normalized behavior and N-methylpiperidine derivatives (31-33) exhibiting diverse profiles depending on the 2'-substituent. The 2'-position substituent critically determines the behavioral and molecular effects, with cyclohexyl substitution (26, 32) normalizing hyperactivity and cyclopropyl-N-methylpiperidine (31) demonstrating anxiolytic and anti-inflammatory properties. Molecular docking revealed specific binding interactions that correlate with observed behavioral effects, particularly for GABA(A) and M2 muscarinic receptors.

The pronounced efficacy of these compounds in attenuating neuroinflammation, reducing caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis, restoring anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 levels, and upregulating HIF-1 expression suggests multifaceted neuroprotective mechanisms that address the complex pathophysiology of ketamine-induced neurotoxicity.

This work establishes 2'-R-6'H-spiro(cycloalkyl-, heterocyclyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazolines as a promising structural class for developing neuroprotective agents with potential applications extending beyond ketamine-induced cognitive dysfunction to post-COVID neurological sequelae and trauma-related neuropsychiatric conditions. Future research should focus on optimizing lead compounds through targeted structural modifications, elucidating precise molecular mechanisms through receptor binding studies, and evaluating efficacy in diverse neurological disorder models.

These findings not only advance our understanding of structure-activity relationships in triazoloquinazoline-based neuroprotectants but also provide rational frameworks for developing multi-target therapeutic strategies for complex neurological conditions characterized by cognitive dysfunction, anxiety, and neuroinflammation.

Supplementary Materials