1. Introduction

The protozoan parasite

Trypanosoma cruzi (

T. cruzi), is the causative agent of Chagas disease (CD). CD is endemic in South America, Central America and in parts of Mexico, however new cases have been reported in Europe [

1,

2], United States [

3], Canada, New Zealand and Australia [

4], mainly as a result of human migration originating from the Americas. Additionally, emerging research highlights potential shifts in the habitats of insect vectors, raising concerns about the disease’s possible spread to currently non-endemic regions [

5]. It is estimated that 6–7 million people worldwide are infected, while another 75 million people are considered at risk of infection [

6].

T. cruzi presents a complex life cycle, alternating between vertebrate (including humans) and invertebrate hosts (triatomine insect vector or “kissing” insect).

Metacyclogenesis is the transformation process of the replicative forms of

T. cruzi (epimastigotes), into the infective metacyclic trypomastigotes (MT) that occurs in hindgut and rectum of the insect vector. Free MT are mixed with urine and feces, and they are released by defecation during the next triatomine feeding cycle, infecting mammalian hosts by penetration of mucosal and epithelial lesions after an insect bite [

7]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying metacyclogenesis and replicating this process in vitro is essential understanding the biology of the parasite and developing innovative strategies to prevent the transmission and progression of CD.

Several factors have been identified as triggers for the metacyclogenesis of

T. cruzi. This process is driven by environmental signals such as changes in temperature and pH, as well as specific molecules found in the insect’s digestive tract, including peptides derive from mammalian alpha D-globin [

8,

9,

10]. Among the most extensively studied factors are nutrient availability—including glucose, amino acids, proteins, and lipids—as well as elevated levels of adenylate cyclase and cyclic AMP, which are linked to the parasite’s capacity to adapt to environmental conditions [

11,

12,

13]. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that nutritional stress induces the adhesion of epimastigotes to the substrate under in vitro differentiating conditions, further highlighting the role of environmental cues in triggering this process [

14].

The molecular events underlying parasite metacyclogenesis involve gene expression and protein synthesis changes. Some cellular pathways are downregulated including glucose energy metabolism (glycolysis, pyruvate metabolism, the Krebs cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation), amino acid metabolism, RNA transcription and DNA replication, cell division and differentiation [

15,

16]. By contrast, genes related to autophagia and infectivity are up-regulated. Nevertheless, an analysis of the literature indicates that most studies on

T. cruzi morphology, gene expression, and metabolic pathways predominantly focus on the epimastigote, amastigote, and blood trypomastigote forms. This could be attributed to the challenges associated with achieving high efficiency and purity in the in vitro production of MT.

Replicating in vivo conditions of the triatomine bug’s hindgut, presents significant challenges in an in vitro setting. The precise combination of environmental cues, such as temperature, pH, and specific molecules found in the insect’s digestive tract, is difficult to replicate. Developing a robust and standardized protocol that consistently induces the transformation of epimastigotes into MT remains an ongoing challenge.

In recent years, alternative methodologies of in vitro metacyclogenesis have emerged [

17]. However, TAU (Triatomine Artificial Urine) medium incubation is used, almost exclusively, to obtain MT in vitro. Briefly, epimastigotes are subjected to nutritional stress by incubation in TAU medium (which have composition and pH similar to triatomine urine and lacks any source of energy), followed by a longer incubation in TAU medium supplemented with same specific amino acids and glucose (TAU3AAG) [

18]. Under these conditions epimastigotes adhere to the surface of the culture flask and subsequently differentiate into MT. This process is characterized by the predominance of three intermediate parasite forms between epimastigotes and MT [

19]. However, numerous intermediate parasite forms involved in the in vivo metacyclogenesis into vector insect have been documented, that cannot be observed during TAU-induced metacycligenesis [

20,

21]. Furthermore, metacyclogenesis process is significantly reduced in epimastigotes maintained in in vitro cultures for prolonged periods [

11,

22].

The present study aimed to establish optimal in vitro conditions for metacyclogenesis of T. cruzi epimastigotes. To achieve this, parasites were subjected to various environmental stimuli to determine the ideal conditions for metacyclogenesis. We identified several conditions that showed higher metacyclogenesis rates than TAU, with epimastigote adherence to the substrate always being crucial. We also observed a strain-dependent relationship in the metacyclogenesis rate and we tested MT were infective on Vero cells. Notably, under these conditions, a greater diversity of intermediate forms was observed compared to those induced by TAU metacyclogenesis, closely resembling the forms observed during metacyclogenesis in the digestive tract of triatomines. This approach holds promise as an in vitro model that more accurately replicates the natural process occurring in vivo. Developing standardized protocols, refining purification techniques, and advancing our understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in metacyclogenesis will greatly enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of in vitro studies on T. cruzi MT.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Parasite Maintenance Culture Conditions

T. cruzi epimastigotes (Dm28c, Y, Cl Brener, Sylvio, Tulahuen strains) were cultured in liver infusion tryptose (LIT) medium (68 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 56 mM Na2HPO4, 44 mM glucose, 5 g/l tryptose, 5 g/l liver infusion, pH 7.2) supplemented with 5 µM Hemin, 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS, Internegocios-SA, Argentine) at 28°C. Subcultures were performed every 48 hr once the population density reached approximately 2-4 x 107 cells/ml, maintaining the culture in the exponential phase for nearly two weeks. Cell viability was assessed by direct microscopic examination. Parasites were quantified in Neubauer chamber or using a hematological counter (Wiener Lab Counter 19) in the white cells channel. The Tulahuen strain was maintained through long-term passages in mice. The Dm28c, Y, Cl Brener and Sylvio strains came from in vitro culture stocks.

2.2. In Vitro Metacyclogenesis

T. cruzi epimastigotes differentiation was performed under chemically defined conditions in MT-LIT medium (LIT medium formulated with 6.7 mM Na

2HPO

4 and 4.7 mM NaH

2PO

4, replacing the standard concentration of 56 mM Na

2HPO

4) supplemented with 5 µM hemin, 10 % heat-inactivated FCS, adjusted to pH 4, 5, or 6, M16 medium (68 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 56 mM Na

2HPO

4, 44 mM glucose, 1.25 g/l tryptose, 5 µM hemin, 2.5% heat-inactivated FCS, pH: 4, 5, or 6), [

23], or TAU medium as describe by [

18]. Briefly, exponential epimastigotes culture were collected by centrifugation at 5500 x g 10 min RT, washed twice with PBS buffer, and suspended in corresponding medium to a final concentration of 5 x 10

6 cells/ml to culture T25 flasks laid flat (10 ml/flask) and incubated at 28°C. TAU medium-induced metacyclogenesis was performed as described by Contreras et al. (18). Briefly, epimastigotes were collected, washed twice with PBS buffer, and subjected to nutritional stress by incubation for 2 h at 28°C in TAU medium (190 mM NaCl, 17 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl

2, 2 mM CaCl

2, 8 mM phosphate buffer pH 6.0) at a density of 5×10

8 parasites/ml. Then, they were diluted 1:100 in TAU3AAG Medium (TAU medium plus 10 mM Glucose, 2 mM L-aspartic acid, 50 mM L-glutamic acid and 10 mM L-proline) and allowed to attach to culture T25 flasks laid flat (10 ml/flask) at 28° C, 72 h.

In all cases, metacyclogenesis was monitored using an inverted microscope. Supernatants were collected after 3, 5, 7, 10 and 12 days of differentiation and the metacyclogenesis percentage was calculated as 100 x the amount of metacyclic trypomastigotes/amount of total parasites counted with or without Giemsa staining [

19]. Briefly, cells were collected by centrifugation at 5500g for 10 minutes at room temperature, washed twice with PBS, and fixed in methanol for 10 minutes to preserve morphology. Fixed cells were transferred onto clean microscope slides and air-dried. A Giemsa working solution (1:10 dilution in stabilized water) was applied to fully cover the cells, followed by a 30-minute incubation at room temperature. The slides were gently rinsed with drinking water, air-dried, and mounted with a drop of Canadian balsam and a coverslip. The stained cells were examined under a light microscope (Olympus CH30 RF200, Japan) for morphological identification.

To evaluate the time-dependent development of intermediate forms during in vitro T. cruzi metacyclogenesis, parasites were immunofluorescently stained. Briefly, cells were centrifuged, washed twice with PBS, allowed to settle on polylysine-coated coverslips, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at RT for 20 min. The fixed parasites were washed with PBS and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. Parasites were incubated with mouse anti-T. cruzi primary antibody diluted in 1% BSA in PBS for 3 h at RT. Unbound antibodies were washed with 0.01% Tween 20 in PBS, and then the slides were incubated with goat FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (fluorescein; Jackson ImmunoResearch) and 2 μg/ml DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) for 1 hr. Finnally, the slides were washed with 0.01% Tween 20 in PBS and mounted with VectaShield (Vector Laboratories).

Ultra-resolution expansion microscopy was used to visualize intermediate forms during metacyclogenesis in acidic media following the methodology described by Alonso V.L. [

24]. Briefly, two million parasites were washed, allowed to settle on poly-D-lysine-coated coverslips, and fixed with 4% formaldehyde and acrylamide. Gelation was performed using a monomer solution, followed by polymerization on ice and incubation at 37 °C. The gels were detached using a denaturation buffer and incubated at 95 °C for 1.5 hours. After overnight expansion in Milli-Q water, gels were washed in PBS, stained with DAPI and NHS-ester Alexa Fluor 647 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) overnight at 4 °C, and subjected to a second round of expansion with multiple water exchanges [

25]. Images were acquired using a confocal Zeiss LSM880 microscope. ImageJ software was used to pseudocoloring and processing all images.

To assess the relationship between the metacyclogenesis rate and glucose concentration, differentiation of T. cruzi epimastigotes Dm28c was performed in MT-LIT or M16 medium pH 6, with glucose concentrations of 44 mM (0.8 g/L), 22 mM (0.4 g/L), or 11 mM (0.2 g/L). Cultures were incubated for 7 days at 28° C. Cells were collected, and the percentage of metacyclogenesis was determined, as previously described. The pH of the medium was monitored throughout the process.

To evaluate the role of substrate interaction in metacyclogenesis, the experiment was repeated in MT-LIT (pH 6), M16 (pH 6) or TAU mediumunder agitation conditions (120 rpm) in an orbital shaker (ECOTRON, Infors HT).

2.3. Susceptibility of T. cruzi strains to Undergo Metacyclogenesis In Vitro

T. cruzi epimastigotes (Dm28c, Y, Cl Brener, Sylvio, Tulahuen strains) were subjected to in vitro differentiation in MT-LIT medium (pH 6), M16 medium (pH 6) or TAU medium, and metacyclogenesis percentage was calculated as 100 x amount of metacyclic trypomastigotes/amount of total parasites counted with or without Giemsa staining, as previously described.

2.4. Cell Line Culture and Infection

Kidney tissue derived from a normal adult African green monkey Vero cell line (ATCC CCL-81) was cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA), supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FCS in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were seeded in 24-well plates containing 18 mm glass slices, at 2.5 × 105 cells/well and maintained for 24 hr in DMEM supplemented with 2% (v/v) FCS. After 24 hr culture, the medium was renewed with the addition of metacyclic trypomastigotes (MOI 10:1), obtained by in vitro differentiation in MT-LIT medium (pH 6), M16 medium (pH 6) or TAU medium, as described previously. After 24 h culture supernatants were discarded, culture was washed with PBS and the medium renewed. Four days p.i., cells were fixed in methanol and stained with Giemsa. The percentage of infected cells and the mean number of amastigotes per infected cell were determined. Three hundred from each quadrupled were counted and the experiment was repeated three independent times.

Cell-derived trypomastigotes were obtained by infection with metacyclic trypomastigotes of Vero cell monolayers after 5 days p.i. The supernatant was collected; trypomastigotes were counted in a Neubauer chamber, fixed in methanol and stained with Giemsa, as previously described. Images were acquired with an epifluorescence Nikon Eclipse Ni-U microscope. ImageJ software was used processes all images.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 3.0 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) using the One-Way Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey test. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and represent one of three independent experiments performed. Significance was set at p<0.05. At least 4 biological replicas per experimental group were used in each experimental round. Three independent experiments were carried out on different days using different culture batches.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Trypanosoma cruzi In Vitro Metacyclogenesis Is Modulated by pH, Glucose and Agitation

In

T. cruzi triatomine vectors, the pH of the rectal contents changes significantly following a blood meal. Initially, the pH rises rapidly from 5.9 to 8.4 due to urine production. Over time, however, it gradually decreases [

26]. These natural pH fluctuations, driven by the vector’s feeding behavior, create environmental changes that the parasite must adapt to, playing a key role in the process of metacyclogenesis.

Under in vitro conditions, deviations from neutral pH in the culture medium have been shown to significantly enhance metacyclogenesis rates. Castellani et al. [

27] reported approximately 40% induction of metacyclic forms in HIL medium when the pH was lowered from 7.2 to 6.7, though this process was completely inhibited at pH 6.3. Contreras et al. [

20] demonstrated that culturing in TAU medium at pH 6 for 2 hours, followed by a 72-hour incubation in TAU-P medium (TAU supplemented with proline), achieves high metacyclogenesis rates. Extending this incubation period does not increase yields and results in MT losing their infective capacity. Acid stress and nutritional deprivation drive mitochondrial remodeling, increase reactive oxygen species production and intensify autophagy. This combination of low pH and nutrient limitation effectively triggers metacyclogenesis within a short timeframe [

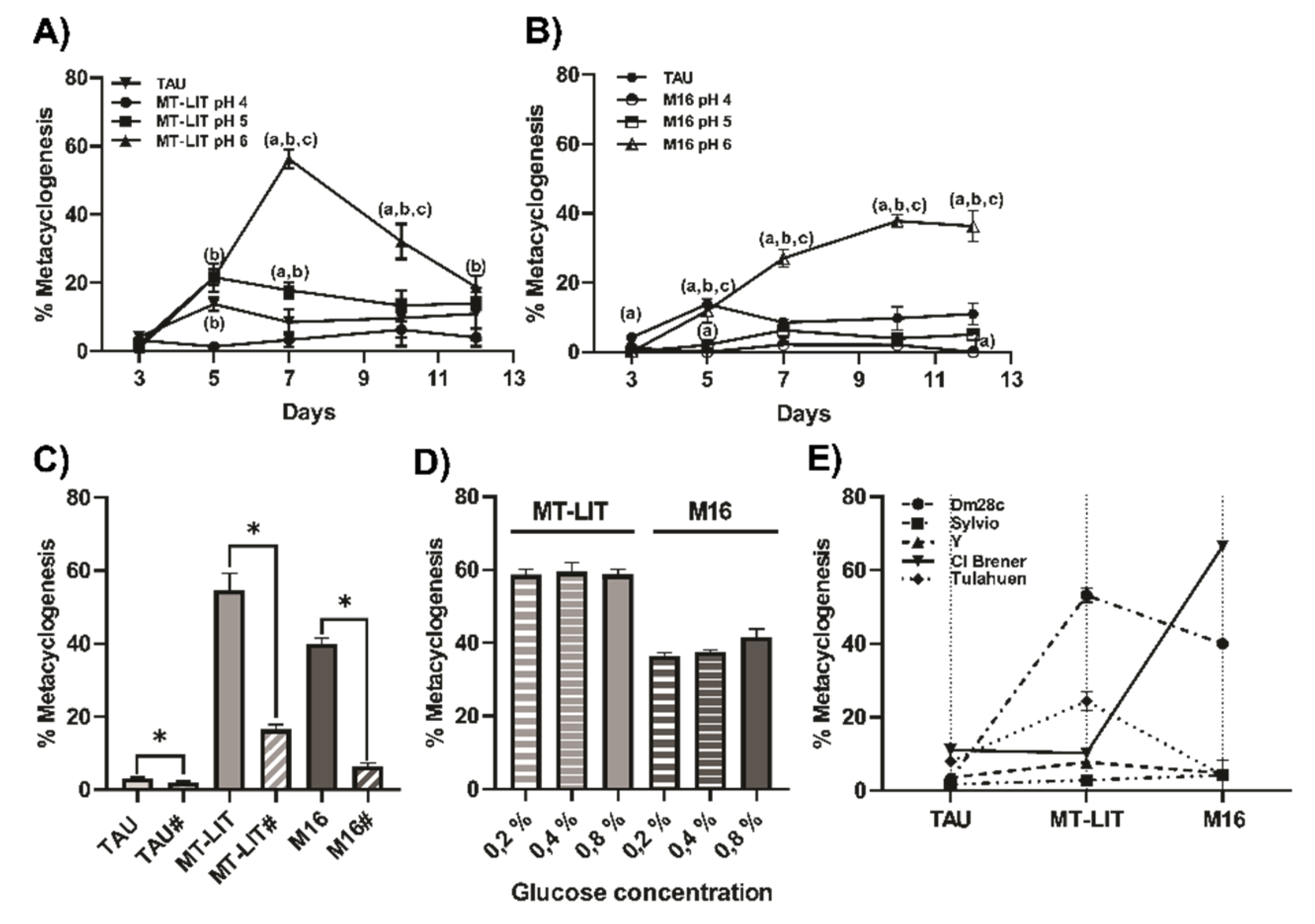

9]. When we assayed the impact of pH (pH 6, 5 or 4) and medium composition (MT-LIT, M16 and TAU medium) a direct correlation between pH and the metacyclogenesis capacity of

T. cruzi epimastigotes (Dm28c strain) was observed. The optimal pH was 6, resulting in approximately 60 % metacyclogenesis in MT-LIT, after 7 days of culture, and 40 % in M16 medium after, 10 days. It should be noted that the yield of MT was similar in both media (MT-LIT: 14,4.10

6 ± 4,8.10

6 MT/ml; M16: 15,3.10

6 ± 4,4.10

6 MT/ml, data not show). By contrast, the TAU medium yielded less than 10 % compared to another medium analyzed (0,6.10

6 ± 0,2.10

6 MT/ml) at 3 days of epimastigote differentiation, which is considered the optimal time of MT production in this method [

18], (

Figure 1A,B).

In triatomine rectum, during an established infection, two thirds of the population of epimastigotes are attached by a small hydrophobic region on the flagellum via nonspecific interaction. Attachment promotes the development of infectious MT. However, unattached epimastigotes also transform into MT. Trypomastigotes arise from different developmental stages, long and short epimastigotes, giant cells and spheromastigotes, but also from epimastigotes in which two different daughter cells arise through unequal cell division, an epimastigote and a MT [

26]. The proportion of MT in the total population depends on the duration of the infection, the triatomine species and the T. cruzi strains, and can be up to 50% in established infections.

We then investigated the influence of parasite interaction with the support surface during the in vitro metacyclogenesis process. As shown in

Figure 1C, adherence is essential for metacyclogenesis in both MT-LIT and M16 media. Agitation caused a significant decrease in metacyclogenesis, from 58% to 18% in MT-LIT medium and from 39% to 7% in M16 medium, respectively. Metacyclic trypomastigotes are nearly absent in epimastigote cultures maintained in the exponential growth phase. A small MT population emerges at the end of this phase, likely due to environmental changes such as nutrient depletion or pH shifts caused by metabolism [31,32]. However, long-term cultured parasites exhibit a reduced capacity to transform into MT compared to those cycled between invertebrate and vertebrate hosts. De Lima et al. [

11] proposed the existence of two physiologically distinct epimastigote populations in in vitro cultures: one multiplying and glucose-adapted, and another capable of differentiation under nutritional stress. The low glucose concentration in the triatomine intestinal tract induced a proteolytic metabolism, whereas parasites in glucose-supplemented culture media, as commonly used in laboratories, rely on glycolytic metabolism to survive.

To clarify the impact of glucose disponibility in our metacyclogeneis protocol, we assayed three differents glucose concentration in the MT-LIT and M16 medium. Sourprisingly, we observed similar metacyclogenesis levels in cultures maintained in medium containing 0.2, 0.4 and 0.8 % glucose, to each medium (

Figure 1D). The spontaneous metacycligenesis in aging cultures on LIT medium at pH 7.2 unaffected by glucose concentration and remained below 5% in all cases (data not shown).

T. cruzi is currently subdivided into seven taxonomic distinct genetic groups, called “discrete typing units” (DTUs), from TcI to TcVI and Tcbat [

27]. Regardless of the DTU, the rates of in vitro metacyclogenesis for T. cruzi strains is highly variable [

28].

We assayed the metacyclogenesis rate in epimastigotes from different DTUs, specifically TcI (Dm28c and Silvio 10/1), TcII (Y), and TcIV (Cl Brener and Tulahuen). Except for the Tulahuen strain, which was transformed into epimastigotes (in LIT medium, pH 7.2) from bloodstream trypomastigotes obtained from a C57BL/6 mouse infection, all Trypanosoma cruzi strains analyzed correspond to epimastigotes that had been cultured in vitro for extended periods. As can be observed in

Figure 1 E, different outcomes were observed depending on the T. cruzi strain studied and the medium assayed. As already mentioned, Dm28c T. cruzi strain shows high metacyclogenesis rates in MT-LIT and M16 media compared to TAU medium (19 and 13 times in relation to % metacyclogenesis in TAU medium, respectively). Metacyclogenesis rates were significantly lower for the Y and Sylvio strains; however, both exhibited high metacyclogenesis rates in MT-LIT, with the Sylvio strain also showing elevated rates in M16 medium. We also observed high metacyclogenesis percentages for CL Brener strain only when M16 medium was used, and Tulahuen strain in MT-LIT medium. These findings support the idea that metacyclogenesis induction rate is determined not only by the pH and composition of the medium, but also by the T. cruzi strain. Contrary to previous reports by other authors [

28,

29], we do not found correlation between the metacyclogenesis rate and DTU T. cruzi strain classification.

3.2. In Vitro Metacyclogenesis of Trypanosoma cruzi in MT-LIT or M16 Medium Generates Intermediate Morphological Forms Bearing Resemblance to Those Reported in the Digestive Tract of Triatomine Vectors

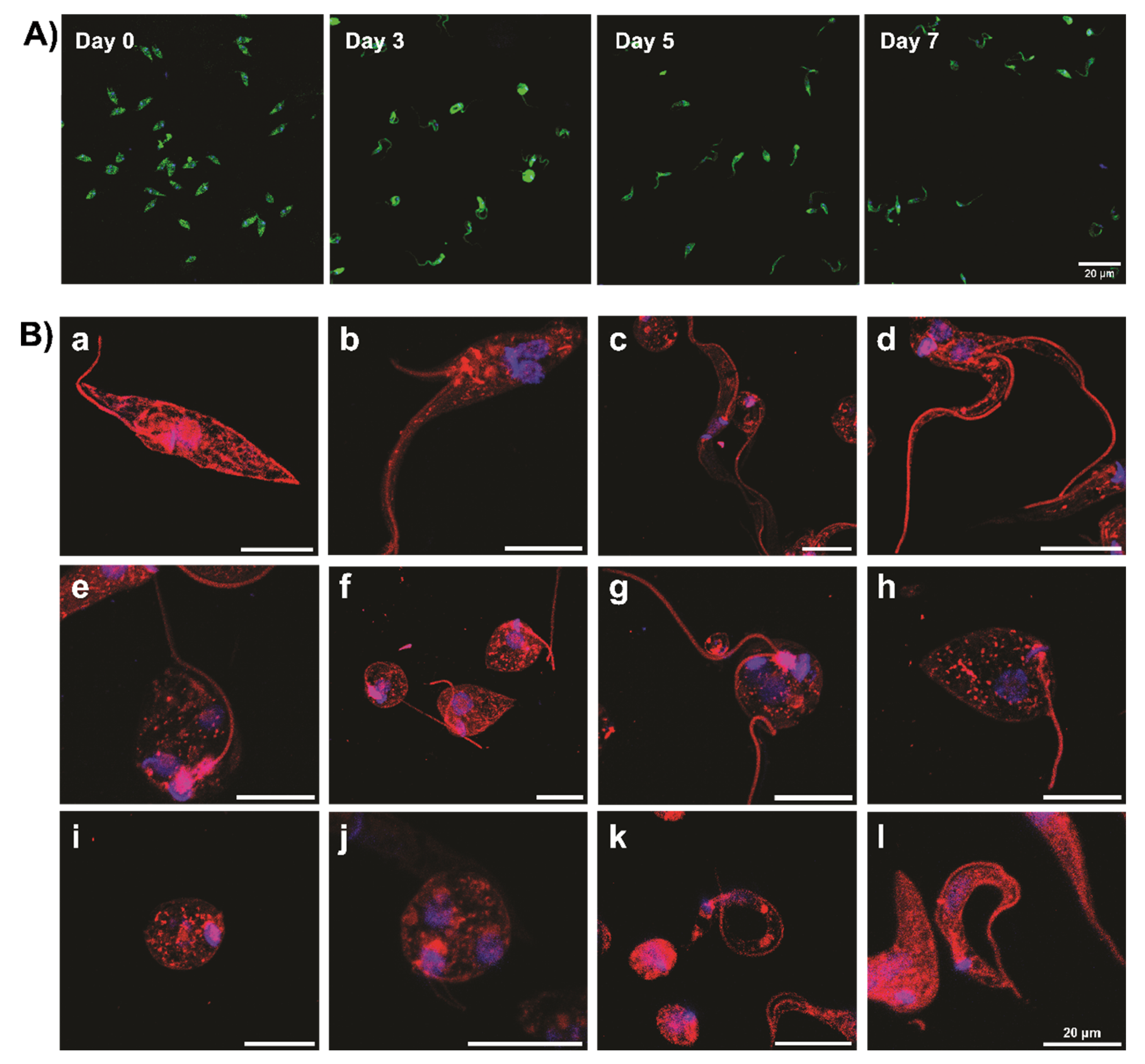

Metacyclogenesis, a key event in the T. cruzi life cycle, has been extensively studied in vitro, focusing on the transition from epimastigotes to metacyclic trypomastigotes, marked by the migration of the kinetoplast to the cell’s posterior end. However, alternative pathways, such as development from spheromastigotes—commonly observed in the vector—and less frequently noted processes like unequal divisions, ring-like forms, and giant cells, remain largely unexplored [

23]. Carlos Chagas documented diverse forms leading to MTs, with over 18 distinct forms classified within the vector [35].

Interestingly, during metacyclogenesis in TAU medium, only epimastigote and MT forms were observed, with minimal or no intermediate forms, consistent with Goncalves et al. [

21]. In contrast, differentiation induced in MT-LIT or M16 medium (pH 6) revealed a diverse array of intermediate stages, including spheromastigotes, epimastigotes, and ring forms, ultimately leading to MT formation (

Figure 2, based on [

17,35]).

3.3. Trypanosoma cruzi MT Obtained Through In Vitro Metacyclogenesis in MT-LIT or M16 Media Exhibit High Infectivity Rates

During metacyclogénesis, parasites increase the expression of proteins needed for surviving in the mammalian medium and infecting cells. Many of them are involved in complement system evading, modulation, and/or manipulation of defense cells responses, mucosal cell infection, and survival at the inner of macrophages [

15,

19]. Consequently, it is expected that only parasites that have fully completed the metacyclogenesis process will be able to achieve the maximum capacity for infecting mammalian cells.

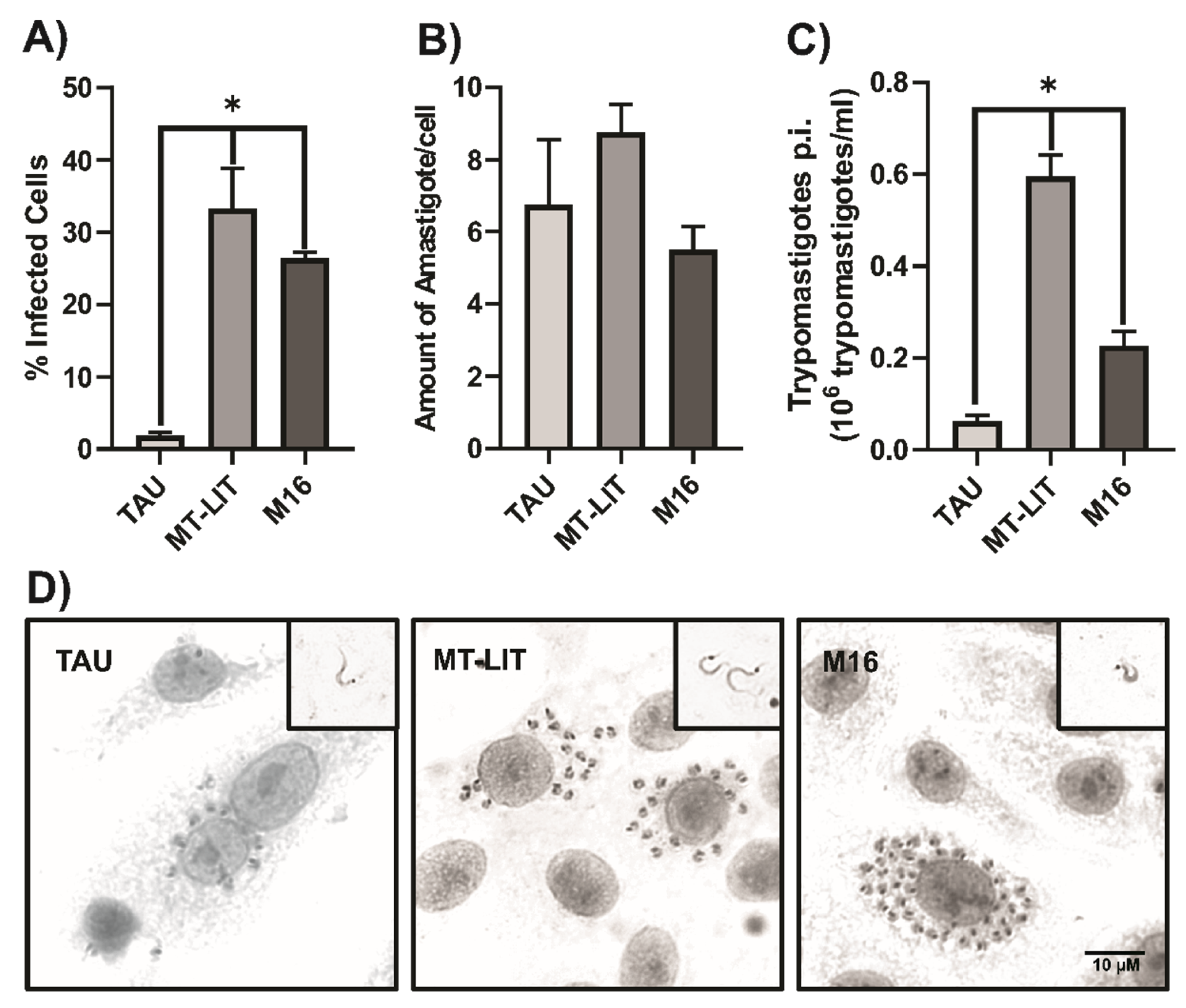

To assess the infectivity of T. cruzi metacyclic trypomastigotes obtained using our metacyclogenesis protocol, Vero cells were exposed to MT (Dm28c strain) derived from MT-LIT, M16, or TAU media, using the same multiplicity of infection (MOI). The percentage of infected cells, the number of amastigotes per infected cell, and the amount of trypomastigotes released were quantified (

Figure 3A–C, respectively).

As shown in

Figure 3, MT obtained from MT-LIT and M16 media exhibit high infectivity rates, surpassing those observed for MT derived from TAU medium. Furthermore cells infected with MT-LIT-derived MT released significantly more trypomastigotes after five days than those infected with M16-derived MT.

Collectively, these results suggest that metacyclogenesis in MT-LIT and M16 media not only yields a higher proportion of MT but also that these exhibit higher infectivity compared to those generated in TAU medium, even when the strains (Dm28c and CLBrener) have been maintained for extended periods in in vitro cultures.

4. Conclusions

For over half a century, researchers have sought to understand and develop controlled in vitro conditions that accurately replicate the metacyclogenesis process of Trypanosoma cruzi. Despite these efforts, standardized in vitro protocols that reliably achieve high metacyclogenesis efficiency across all T. cruzi strains have yet to be established.

In this study, we evaluated a range of stress conditions to induce metacyclogenesis and identified culture conditions that produce intermediate forms of T. cruzi, closely resembling those observed during the natural metacyclogenesis process within the vector insect. Our results further reveal that the ability of specific stress factors to trigger metacyclogenesis is more dependent on the strain than on the DTU classification.

Author Contributions

Virginia Perdomo: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, visualization, project administration, writing—original draft preparation, funding acquisition. Esteban Serra: conceptualization, methodology, project administration, writing—review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition. Victoria Boselli: methodology, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation. Romina Manarin: methodology, investigation.

Funding

This research was funded by FONCyT, grant number PICT-2020 SERIEA-01704; Universidad Nacional de Rosario (UNR), grant number ACRE 80020190300048UR, and ASaCTeI, grant number PEICID-2023-115.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw and processed data supporting this research are available at: doi:10.57715/UNR/EZQUQI.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dolores Campos and Rodrigo Vena for technical assistance with mammalian cell culture and microscopy, respectively. We wish to thank Dr. E. Chiari (Federal University of Minas Gerais) for T. cruzi epimastigotes Y strain, and to Dr. Ana Rosa Perez and Lic. Cecilia Farre (IDICER-CONICET) for T. cruzi trypomastigote Tulahuen strain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

CD

DTU |

Chagas Disease

Discrete Typing Units |

LIT

MT |

Liver infusion tryptose medium

Metacyclic trypomastigotes |

MT-LIT

TAU

T. cruzi

|

Metacyclic trypomastigotes- Liver infusion tryptose medium

Triatomine Artificial

Urine

Trypanosoma cruzi |

References

- Arsuaga, M. , et al., Imported infectious diseases in migrants from Latin America: A retrospective study from a referral centre for tropical diseases in Spain, 2017-2022. Travel Med Infect Dis, 2024. 59: p. 102708.

- Giancola, M.L. , et al., Chagas Disease in the Non-Endemic Area of Rome, Italy: Ten Years of Experience and a Brief Overview. Infect Dis Rep, 2024. 16(4): p. 650-663.

- Hochberg, N.S. and S.P. Montgomery, Chagas Disease. Ann Intern Med, 2023. 176(2): p. ITC17-ITC32.

- Jackson, Y. A. Pinto, and S. Pett, Chagas disease in Australia and New Zealand: risks and needs for public health interventions. Trop Med Int Health, 2014. 19(2): p. 212-8.

- Forsyth, C. , et al., Climate change and Trypanosoma cruzi transmission in North and central America. Lancet Microbe, 2024. 5(10): p. 100946.

- WHO. 2025 2025-01-06; Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chagas-disease-(american-trypanosomiasis).

- Melo, R.F.P., A. A. Guarneri, and A.M. Silber, The Influence of Environmental Cues on the Development of Trypanosoma cruzi in Triatominae Vector. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2020. 10: p. 27.

- Loshouarn, H. and A.A. Guarneri, The interplay between temperature, Trypanosoma cruzi parasite load, and nutrition: Their effects on the development and life-cycle of the Chagas disease vector Rhodnius prolixus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2024. 18(2): p. e0011937.

- Pedra-Rezende, Y. , et al., Starvation and pH stress conditions induced mitochondrial dysfunction, ROS production and autophagy in Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis, 2021. 1867(2): p. 166028.

- Garcia, E.S. , et al., Induction of Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclogenesis in the gut of the hematophagous insect vector, Rhodnius prolixus, by hemoglobin and peptides carrying alpha D-globin sequences. Exp Parasitol, 1995. 81(3): p. 255-61.

- De Lima, A.R. , et al., Cultivation of Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes in low glucose axenic media shifts its competence to differentiate at metacyclic trypomastigotes. Exp Parasitol, 2008. 119(3): p. 336-42.

- Wainszelbaum, M.J. , et al., Free fatty acids induce cell differentiation to infective forms in Trypanosoma cruzi. Biochem J, 2003. 375(Pt 3): p. 705-12.

- Hamedi, A. , et al., In vitro metacyclogenesis of Trypanosoma cruzi induced by starvation correlates with a transient adenylyl cyclase stimulation as well as with a constitutive upregulation of adenylyl cyclase expression. Mol Biochem Parasitol, 2015. 200(1-2): p. 9-18.

- Figueiredo, R.C.B.Q., D. S. Rosa, and M.J. Soares, Differentiation Oftrypanosoma Cruziepimastigotes: Metacyclogenesis and Adhesion to Substrate Are Triggered by Nutritional Stress. Journal of Parasitology, 2000. 86(6): p. 1213-1218.

- Garcia-Huertas, P. , et al., Transcriptional changes during metacyclogenesis of a Colombian Trypanosoma cruzi strain. Parasitol Res, 2023. 122(2): p. 625-634.

- Losinno, A.D. , et al., Induction of autophagy increases the proteolytic activity of reservosomes during Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclogenesis. Autophagy, 2021. 17(2): p. 439-456.

- Rodriguez Duran, J. , et al., In vitro differentiation of Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes into metacyclic trypomastigotes using a biphasic medium. STAR Protoc, 2021. 2(3): p. 100703.

- Contreras, V.T. , et al., In vitro differentiation of Trypanosoma cruzi under chemically defined conditions. Mol Biochem Parasitol, 1985. 16(3): p. 315-27.

- Goncalves, C.S. , et al., Revisiting the Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclogenesis: morphological and ultrastructural analyses during cell differentiation. Parasit Vectors, 2018. 11(1): p. 83.

- Alarcon, M. , et al., Metacyclogenesis of Trypanosoma cruzi in B. ferroae (Reduviidae: Triatominae) and feces infectivity under laboratory conditions. Biomedica, 2021. 41(1): p. 179-186.

- Kollien, A.H. and G.A. Schaub, The development of Trypanosoma cruzi in triatominae. Parasitol Today, 2000. 16(9): p. 381-7.

- Contreras, V.T., A. R. De Lima, and G. Zorrilla, Trypanosoma cruzi: maintenance in culture modify gene and antigenic expression of metacyclic trypomastigotes. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, 1998. 93(6): p. 753-60.

- Rondinelli, E. , et al., Trypanosoma cruzi: an in vitro cycle of cell differentiation in axenic culture. Exp Parasitol, 1988. 66(2): p. 197-204.

- Alonso, V.L. , Ultrastructure Expansion Microscopy (U-ExM) in Trypanosoma cruzi: localization of tubulin isoforms and isotypes. Parasitol Res, 2022. 121(10): p. 3019-3024.

- de Hernandez, M.A. , et al., Ultrastructural Expansion Microscopy in Three In Vitro Life Cycle Stages of Trypanosoma cruzi. J Vis Exp, 2023(195).

- Schaub, G.A. , Interaction of Trypanosoma cruzi, Triatomines and the Microbiota of the Vectors-A Review. Microorganisms, 2024. 12(5).

- Silvestrini, M.M.A. , et al., New insights into Trypanosoma cruzi genetic diversity, and its influence on parasite biology and clinical outcomes. Front Immunol, 2024. 15: p. 1342431.

- Abegg, C.P. , et al., Polymorphisms of blood forms and in vitro metacyclogenesis of Trypanosoma cruzi I, II, and IV. Exp Parasitol, 2017. 176: p. 8-15.

- Caceres, T.M. , et al., Comparative analysis of metacyclogenesis and infection curves in different discrete typing units of Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasitol Res, 2024. 123(4): p. 181.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).