Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

04 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

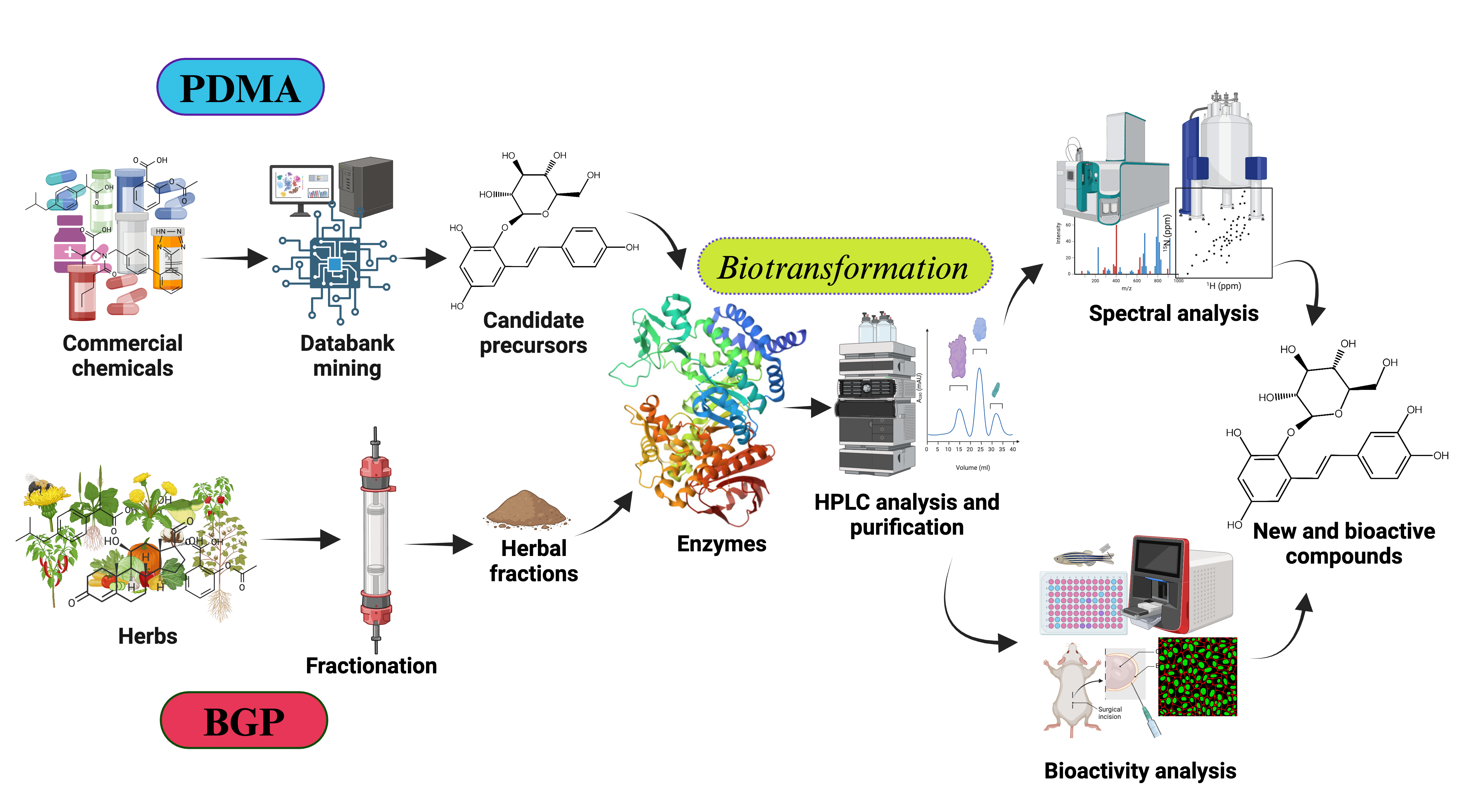

2. Finding New Compounds by Predicted Data Mining Approach (PDMA)

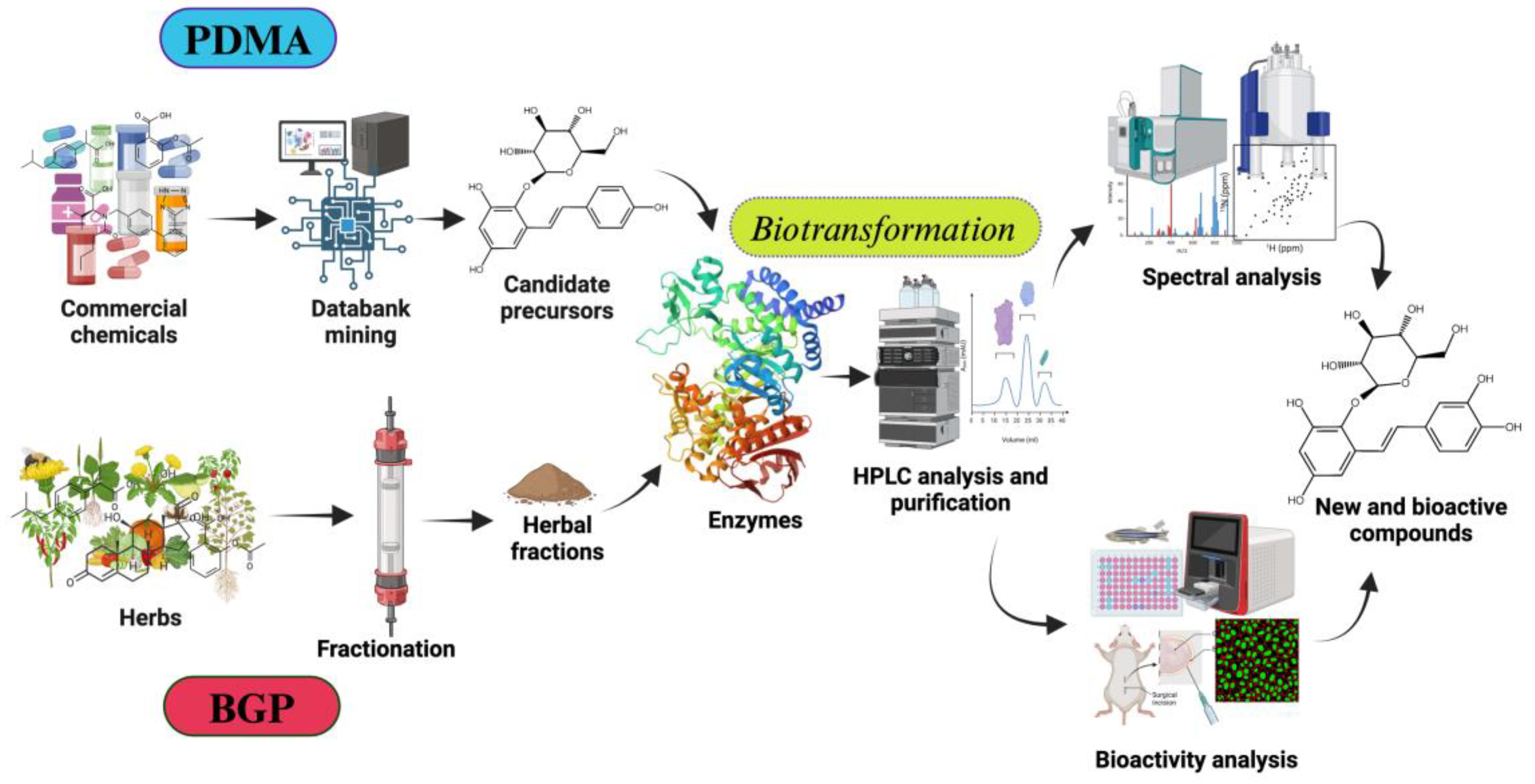

- Setting Screening Criteria (selecting suitable enzymatic reaction): Define clear screening criteria based on the target enzyme's known catalytic mechanism, substrate preference, and desired product characteristics. These criteria may include specific functional groups, structural features, physicochemical properties of precursor compounds, available at an industrial scale. For example, hydroxylation by tyrosinase (BmTYR) requires precursors contained a phenyl group mimicking the structure of tyrosine. glycosylation by glycosyltransferases (GTs) needs precursors with at least one hydroxyl group that can be glycosylated. O-Methylation by O-methyltransferases (OMTs) needs precursors with a catechol structure.

- Screening Candidate Precursors: Based on the defined screening criteria, potential candidate precursors could be screened from commercial chemical or natural product databases. These databases usually contain a vast amount of compound structures and related information. In some cases, customized catalogs of commercially available compounds are used.

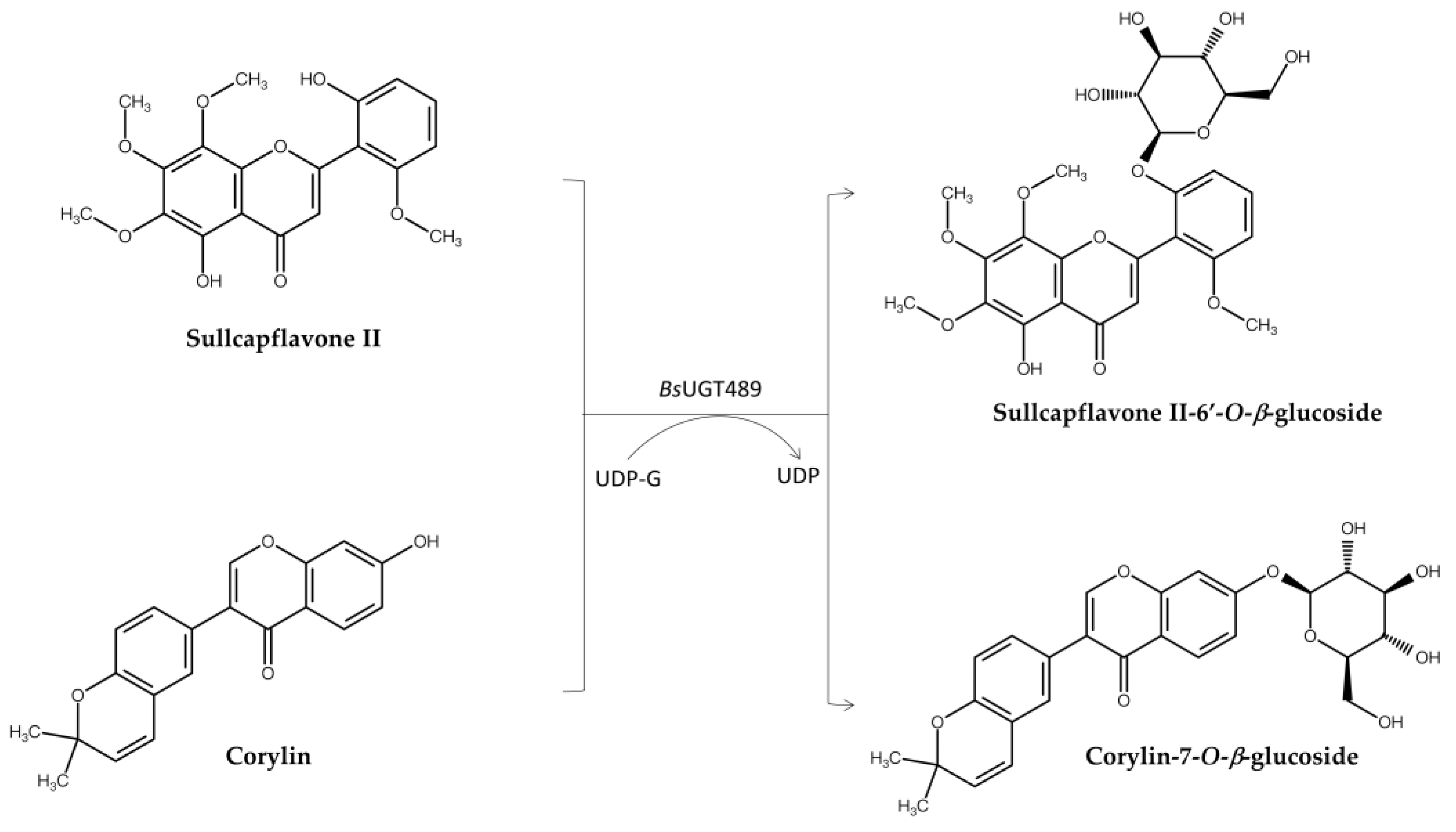

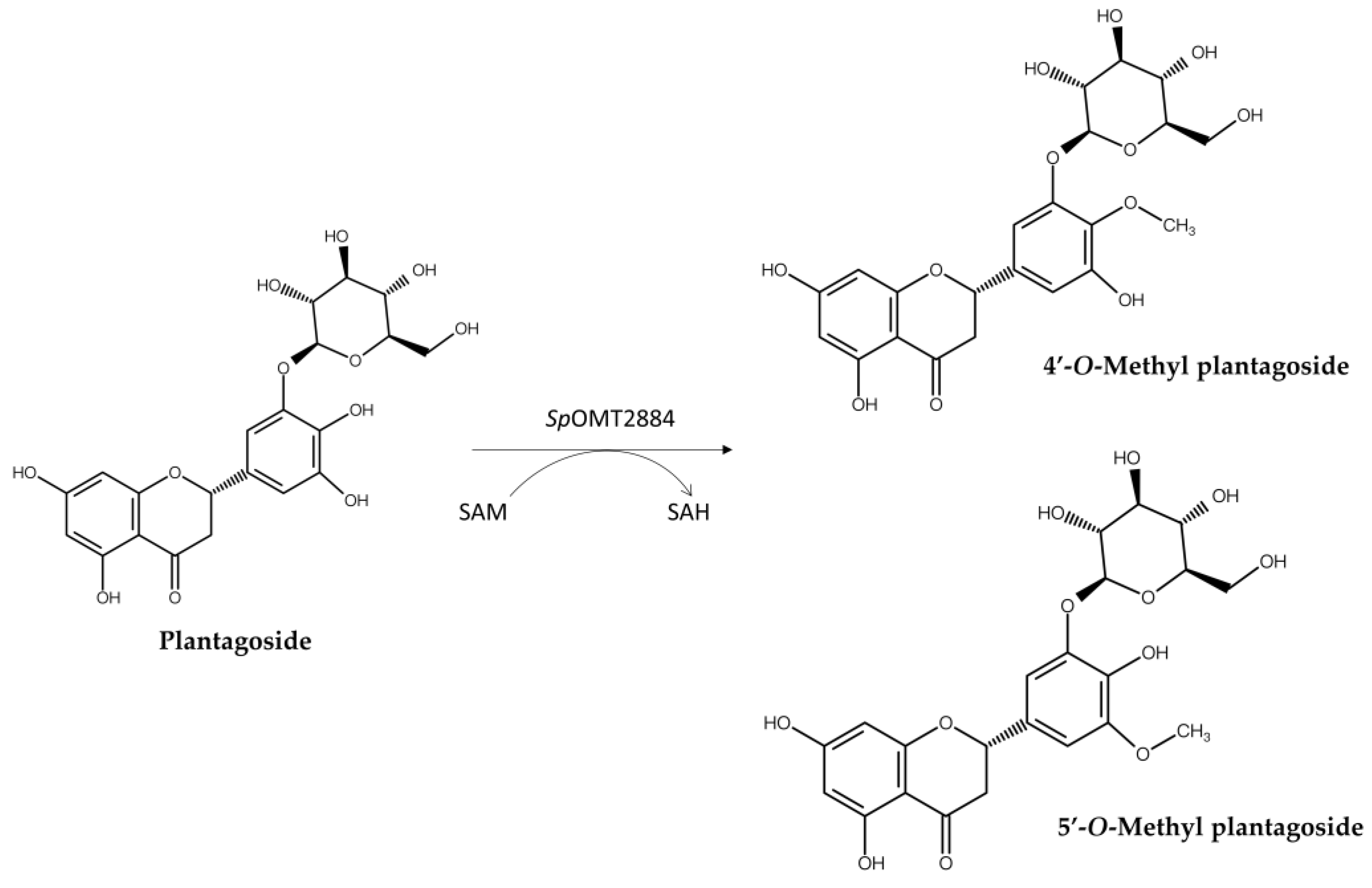

- Predicting Biotransformation Product Structure: For the selected candidate precursors, the structures of potential biotransformation products under the action of the target enzyme are determined using chemical drawing software (such as Reaxys® or SciFindern®). This step requires researchers to have a certain knowledge on the enzyme's catalytic mechanism; for instance, BmTYR primarily catalyzes ortho-hydroxylation, GTs catalyze the transfer of sugar moieties, and OMTs catalyze the transfer of methyl groups.

- Verifying Product Novelty: The predicted biotransformation product structures are uploaded to chemical databases (e.g., Reaxys®, PubChem®, or SciFindern®) to verify their novelty, confirming whether each product is a known compound. Only precursors that yield novel derivatives are further selected for subsequent experimental validation.

- In Vitro Biotransformation and Product Identification: The selected precursors are reacted with the target enzyme in vitro. The biotransformed products are analyzed using isolation methods, such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Once the putative new compounds are purified, their chemical structures can be identified using techniques such as mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR).

- Bioactivity Evaluation: Alternatively, the identified compounds may undergo bioactivity testing to evaluate their potential application value. The tested activities may include antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and anti-diabetic properties, etc.

- High Efficiency: PDMA enables rapid in silico screening of a large number of compounds, targeting potential precursors and thereby significantly reducing the time required to find suitable biotransformation substrates.

- Reduced Cost: By minimizing the number of trial-and-error experiments, PDMA helps to lower the consumption of experimental reagents, enzymes, and human resources, as well as reducing costs associated with clinical trials.

- Predicting Novelty: PDMA predicts whether the product is a novel compound before experimentation, avoiding the risk of redundant research on known compounds and increasing the likelihood of discovering new entities.

- Knowledge-Based Guidance: PDMA can predict outcomes based on the enzyme's characteristics and the precursor's structure, experimental design and helping researchers better understand the potential results of biotransformation reactions.

- Applicable to Various Enzymes and Reactions: The PDMA concept is not limited to specific enzymes or reaction types. It can be adapted based on the catalytic properties of different enzymes and applied to various biotransformation processes, including hydroxylation, glycosylation, and methylation.

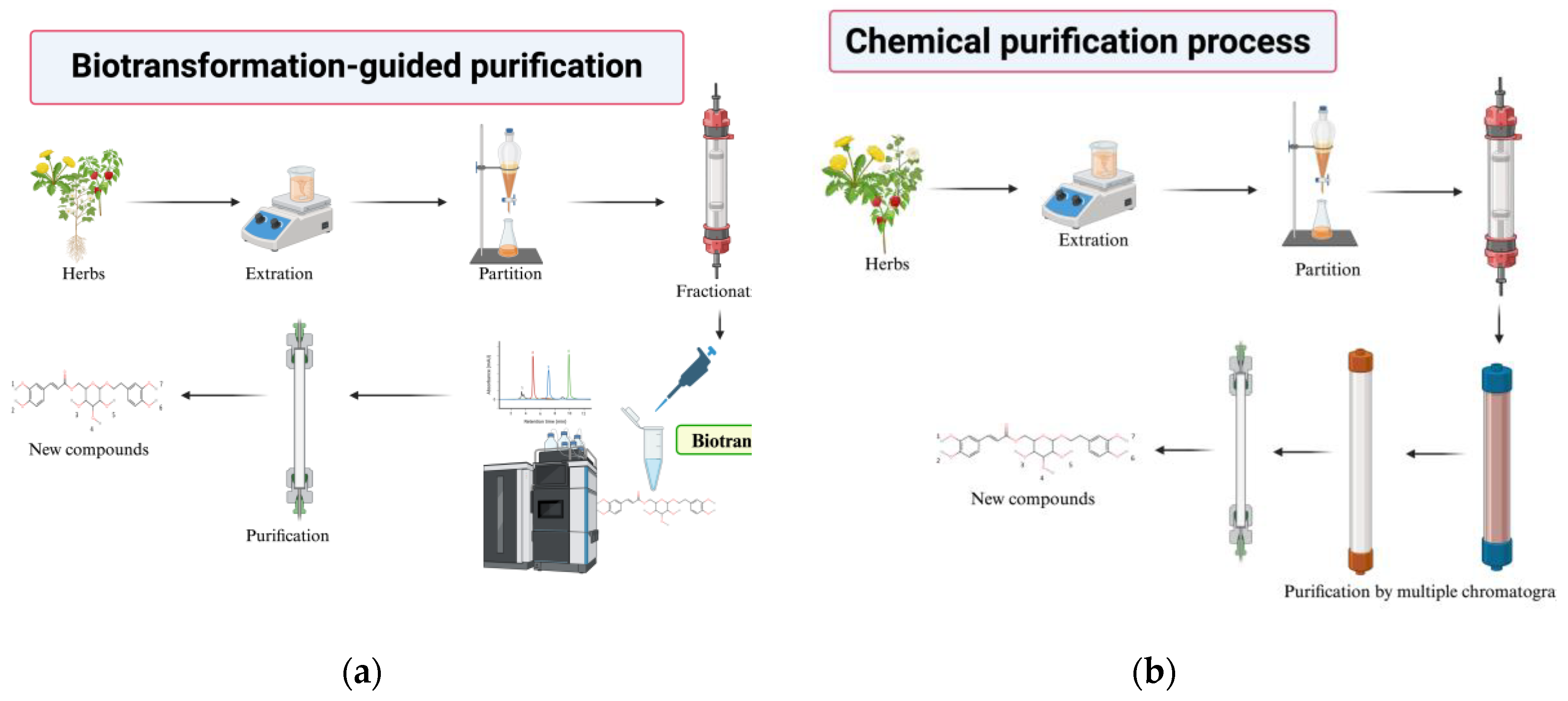

3. Finding New Compounds by Biotransformation-Guided Purification (BGP)

- Discovery of Novel Bioactive Compounds: BGP facilitates the identification of new molecules that are structurally related to known bioactive precursors but possess altered or enhanced properties.

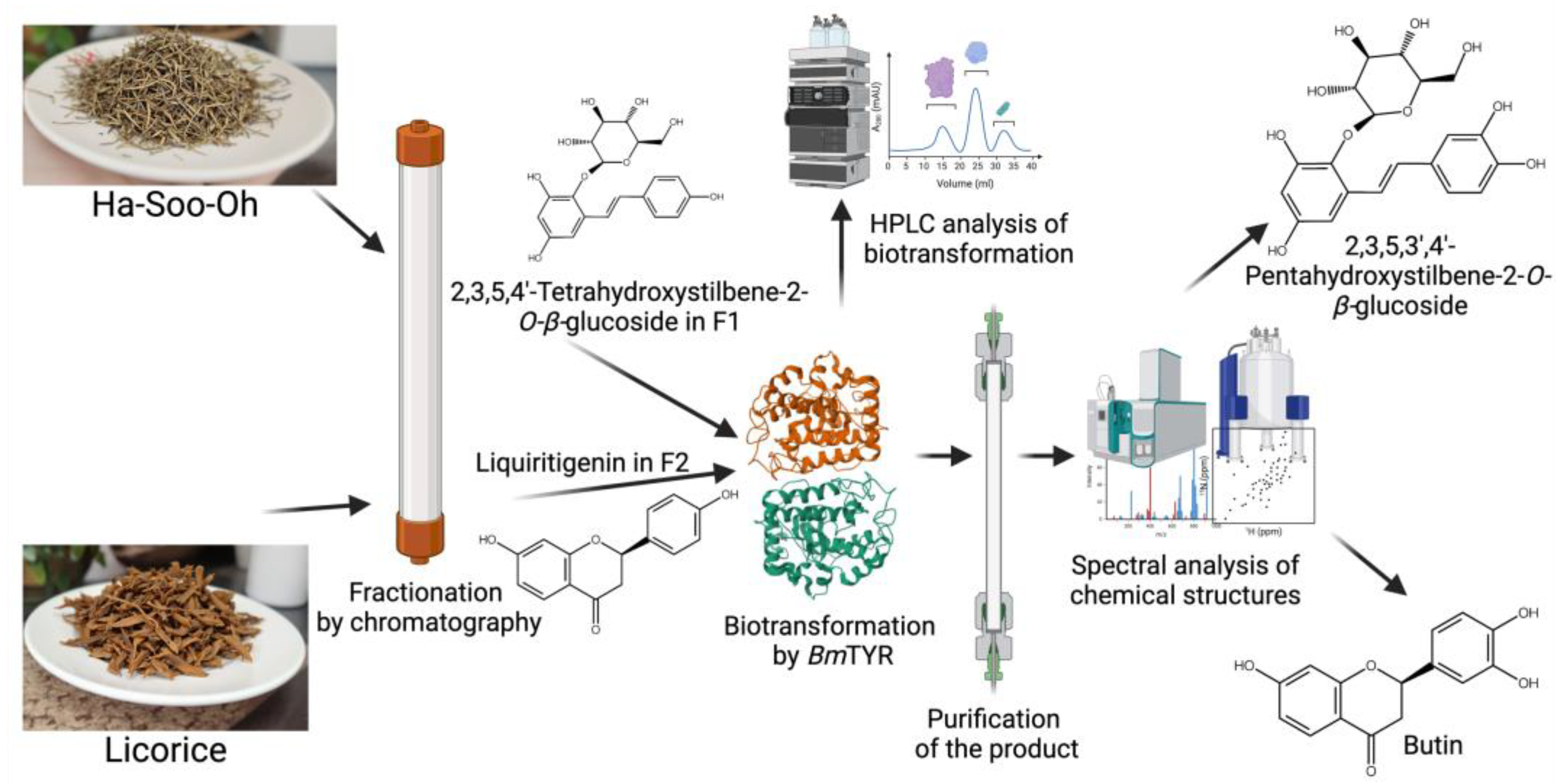

- Enhanced Bioactivity: Enzymatic biotransformation can modify the functional groups of precursor molecules, leading to derivatives with significantly improved bioactivity, as demonstrated by the enhanced antioxidant activity of butin and PSG.

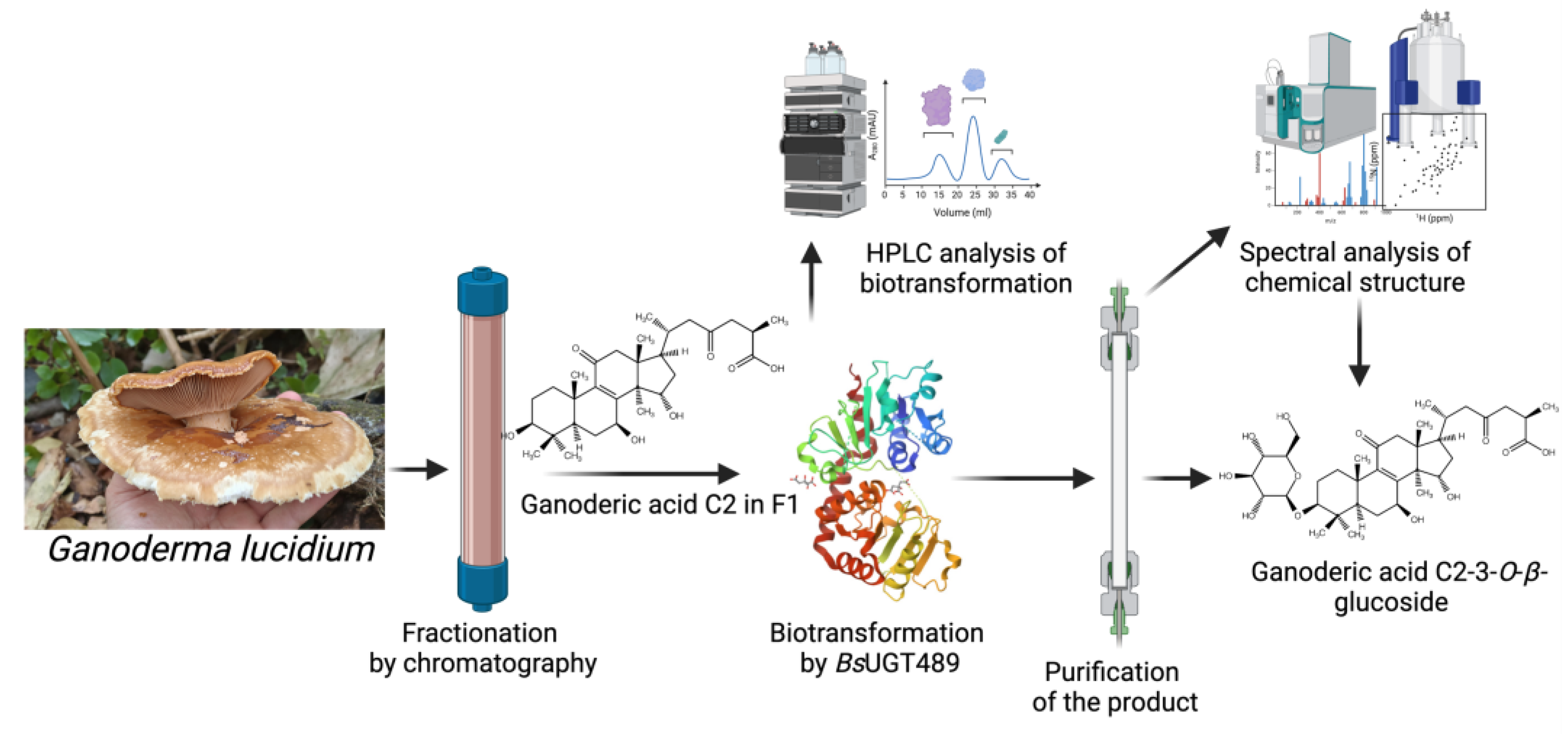

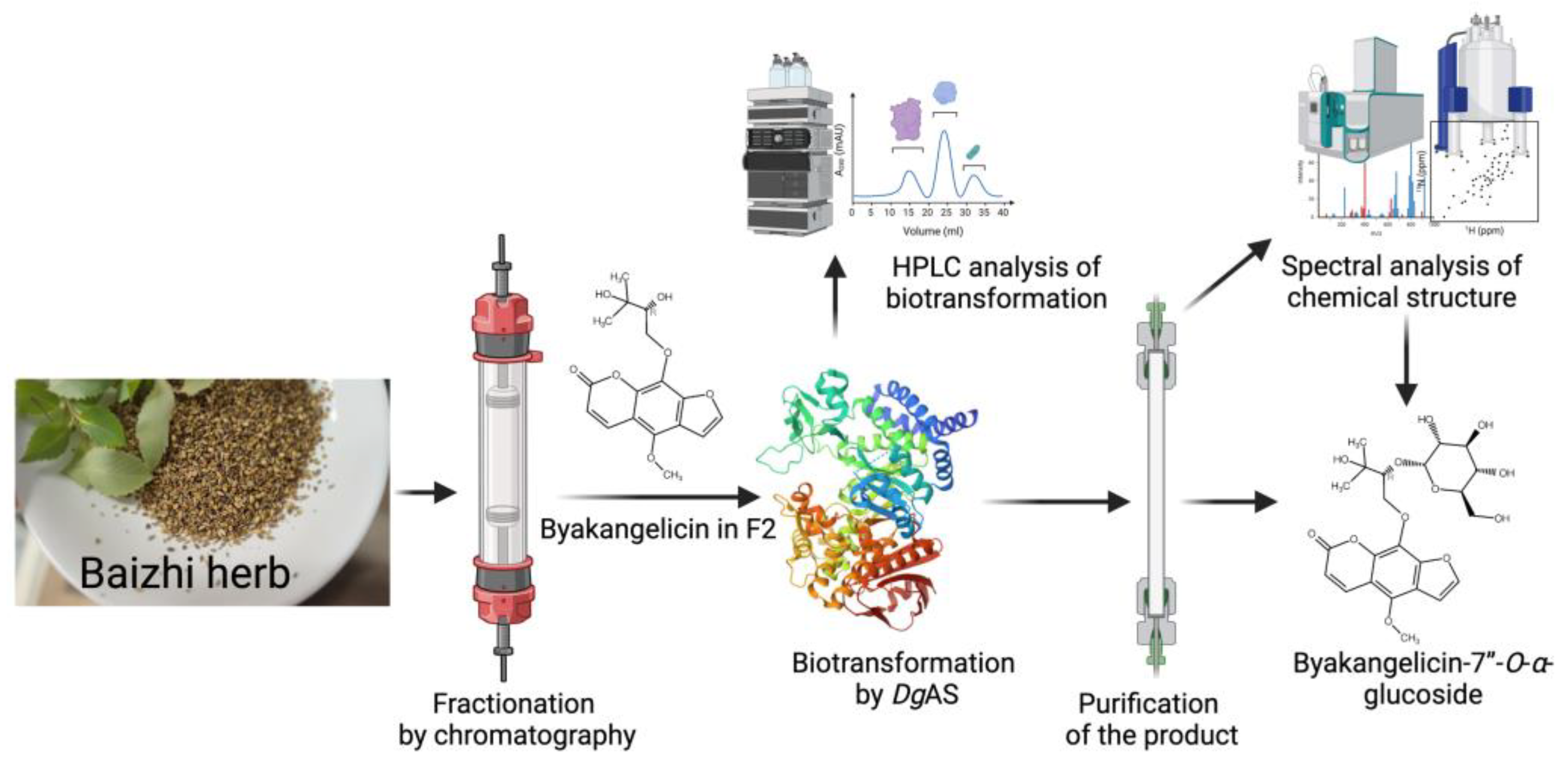

- Improved Physicochemical Properties: BGP can be used to generate derivatives with enhanced pharmaceutical properties, such as significantly increased aqueous solubility, as seen with the Ganoderma glucosides GAC2-3-O-β-glucoside and GAC2-3,15-O-β-diglucoside and byakangelicin-7’’-O-α-glucoside from Baizhi.

- Increased Yield of Active Ingredients: By selectively biotransforming a specific precursor within a complex mixture and then purifying the valuable product, BGP can sometimes lead to higher yields of the target compound compared to direct isolation from the natural source, as observed in the production of butin.

- Cost-Effectiveness: BGP can utilize crude or partially purify extracts as starting materials, potentially reduce the need for extensive initial purification of precursors, and lead the process more economical.

- Efficiency in Screening Biotransformable Compounds: BGP offers an efficient method to screen complex natural extracts for compounds that can be biotransformed by specific enzymes, rather than testing expensive pure compounds individually.

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ekiert, H.M.; Szopa, A. Biological activities of natural products. Molecules 2020, 25, 5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muffler, K.; Leipold, D.; Scheller, M.-C.; Haas, C.; Steingroewer, J.; Bley, T.; Neuhaus, H.E.; Mirata, M.A.; Schrader, J.; Ulber, R. Biotransformation of triterpenes. Process Biochemistry 2011, 46, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Chen, X.; Jassbi, A.R.; Xiao, J. Microbial biotransformation of bioactive flavonoids. Biotechnology Advances 2015, 33, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luca, S.V.; Macovei, I.; Bujor, A.; Miron, A.; Skalicka-Wozniak, K.; Aprotosoaie, A.C.; Trifan, A. Bioactivity of dietary polyphenols: The role of metabolites. Critical Review of Food Scienes and Nutritions 2020, 60, 626–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, N.; Saify, Z.S. Enzymatic biotransformation of terpenes as bioactive agents. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry 2013, 28, 1113–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, P.; Francisco, R.; Andres, G.-G.; Antonio, M. Microbial transformation of triterpenoids. Mini-Reviews in Organic Chemistry 2009, 6, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badshah, S.L.; Faisal, S.; Muhammad, A.; Poulson, B.G.; Emwas, A.H.; Jaremko, M. Antiviral activities of flavonoids. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy 2021, 140, 111596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-Y.; Ding, H.-Y.; Wang, T.-Y.; Cai, C.-Z.; Chang, T.-S. Antioxidant and anti-α-glucosidase activities of biotransformable dragon’s blood via predicted data mining approach. Process Biochemistry 2023, 130, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.Y.; Ding, H.Y.; Wang, T.Y.; Liu, C.W.; Wu, J.Y.; Chang, T.S. Development of a new isoxsuprine hydrochloride-based hydroxylated compound with potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2024, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.S.; Wu, J.Y.; Ding, H.Y.; Tayo, L.L.; Suratos, K.S.; Tsai, P.W.; Wang, T.Y.; Fong, Y.N.; Ting, H.J. Predictive production of a new highly soluble glucoside, corylin-7-O-beta-glucoside with potent anti-inflammatory and anti-melanoma activities. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.S.; Ding, H.Y.; Wang, T.Y.; Wu, J.Y.; Tsai, P.W.; Suratos, K.S.; Tayo, L.L.; Liu, G.C.; Ting, H.J. In silico-guided synthesis of a new, highly soluble, and anti-melanoma flavone glucoside: Skullcapflavone II-6'-O-beta-glucoside. Biotechnology and Applied Biochemistry 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.-S.; Ding, H.-Y.; Wu, J.-Y.; Lee, C.-C.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.-C.; Wang, T.-Y. New methyl compounds using the predicted data mining approach (PDMA), coupled with the biotransformation of Streptomyces peucetius O-methyltransferase. Biocatalysis and Biotransformation 2025, 43, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.Y.; Wang, T.Y.; Wu, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.R.; Chang, T.S. Novel Ganoderma triterpenoid saponins from the biotransformation-guided purification of a commercial Ganoderma extract. Journal Bioscience Bioengineering 2023, 135, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.S.; Ding, H.Y.; Wu, J.Y.; Wang, M.L.; Ting, H.J. Biotransformation-guided purification of a novel glycoside derived from the extracts of Chinese berb Baizhi. Journal Bioscience Bioengineering 2024, 137, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Ding, H.Y.; Wang, T.Y.; Hsu, M.H.; Chang, T.S. A new stilbene glucoside from biotransformation-guided purification of Chinese herb Ha-Soo-Oh. Plants (Basel) 2022, 11, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.-Y.; Ding, H.-Y.; Wang, T.-Y.; Cai, C.-Z.; Chang, T.-S. Application of biotransformation-guided purification in Chinese medicine: an example to produce butin from licorice. Catalysts 2022, 12, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Baek, K.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, B.G. Using tyrosinase as a monophenol monooxygenase: A combined strategy for effective inhibition of melanin formation. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2016, 113, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, C.M.; Wang, D.S.; Chang, T.S. Improving free radical scavenging activity of soy isoflavone glycosides daidzin and genistin by 3’-hydroxylation using recombinant Escherichia coli. Molecules 2016, 21, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.S.; Wang, T.Y.; Chiang, C.M.; Lin, Y.J.; Chen, H.L.; Wu, Y.W.; Ting, H.J.; Wu, J.Y. Biotransformation of celastrol to a novel, well-soluble, low-toxic and anti-oxidative celastrol-29-O-beta-glucoside by Bacillus glycosyltransferases. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2021, 131, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Wang, T.Y.; Ding, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.R.; Lin, S.Y.; Chang, T.S. Enzymatic synthesis of novel vitexin glucosides. Molecules 2021, 26, 6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.S.; Wang, T.Y.; Yang, S.Y.; Kao, Y.H.; Wu, J.Y.; Chiang, C.M. Potential industrial production of a well-soluble, alkaline-stable, and anti-inflammatory isoflavone glucoside from 8-hydroxydaidzein glucosylated by recombinant amylosucrase of Deinococcus geothermalis. Molecules 2019, 24, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-S.; Chiang, C.-M.; Wu, J.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-L.; Ting, H.-J. Production of a new triterpenoid disaccharide saponin from sequential glycosylation of ganoderic acid A by 2 Bacillus glycosyltransferases. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 2021, 85, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yang, J.; Xie, Y. Improvement strategies for the oral bioavailability of poorly water-soluble flavonoids: An overview. International Journal of Pharmacy 2019, 570, 118642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.H.; Tseng, W.C.; Leu, Y.L.; Chen, C.Y.; Lee, W.C.; Chi, Y.C.; Cheng, S.F.; Lai, C.Y.; Kuo, C.H.; Yang, S.L.; et al. The flavonoid corylin exhibits lifespan extension properties in mouse. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopycki, J.G.; Rauh, D.; Chumanevich, A.A.; Neumann, P.; Vogt, T.; Stubbs, M.T. Biochemical and structural analysis of substrate promiscuity in plant Mg2+-dependent O-methyltransferases. Journal of Molecular Biology 2008, 378, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.G.; Kim, H.; Hur, H.G.; Lim, Y.; Ahn, J.H. Regioselectivity of 7-O-methyltransferase of poplar to flavones. Journal of Biotechnology 2006, 126, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: an overview. Journal of Nutrition Science 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solnier, J.; Martin, L.; Bhakta, S.; Bucar, F. Flavonoids as novel efflux pump inhibitors and antimicrobials against both environmental and pathogenic intracellular mycobacterial species. Molecules 2020, 25, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.M.; Chang, Y.J.; Wu, J.Y.; Chang, T.S. Production and anti-melanoma activity of methoxyisoflavones from the biotransformation of genistein by two recombinant Escherichia coli strains. Molecules 2017, 22, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.M.; Ding, H.Y.; Tsai, Y.T.; Chang, T.S. Production of two novel methoxy-isoflavones from biotransformation of 8-hydroxydaidzein by recombinant Escherichia coli expressing O-methyltransferase SpOMT2884 from Streptomyces peucetius. Intertnational Journal of Molecular Science 2015, 16, 27816–27823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Wu, C. Glycosyltransferase GT1 family: Phylogenetic distribution, substrates coverage, and representative structural features. Computional and Structrucral Biotechnology Journal 2020, 18, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Xu, W.; Guang, C.; Zhang, W.; Mu, W. Glycosylation of flavonoids by sucrose- and starch-utilizing glycoside hydrolases: A practical approach to enhance glycodiversification. Critical Review on Food Scienes and Nutrition 2023, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slamova, K.; Kapesova, J.; Valentova, K. "Sweet flavonoids": glycosidase-catalyzed modifications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-Y.; Ding, H.-Y.; Wang, T.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-L.; Ting, H.-J.; Chang, T.-S. Improving aqueous solubility of natural antioxidant mangiferin through glycosylation by maltogenic amylase from Parageobacillus galactosidasius DSM 18751. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestrom, L.; Przypis, M.; Kowalczykiewicz, D.; Pollender, A.; Kumpf, A.; Marsden, S.R.; Bento, I.; Jarzebski, A.B.; Szymanska, K.; Chrusciel, A.; et al. Leloir glycosyltransferases in applied biocatalysis: a multidisciplinary approach. International Journal of Molecular Science 2019, 20, 5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombard, V.; Golaconda Ramulu, H.; Drula, E.; Coutinho, P.M.; Henrissat, B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42, D490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Guang, C.; Mu, W. Amylosucrase as a transglucosylation tool: From molecular features to bioengineering applications. Biotechnology Advances 2018, 36, 1540–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-S.; Choi, K.-H.; Park, Y.-D.; Park, C.-S.; Cha, J.-H. Enzymatic Synthesis of Polyphenol Glycosides by Amylosucrase. Journal of Life Science 2011, 21, 1631–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulis, C.; Andre, I.; Remaud-Simeon, M. GH13 amylosucrases and GH70 branching sucrases, atypical enzymes in their respective families. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2016, 73, 2661–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rha, C.S.; Kim, H.G.; Baek, N.I.; Kim, D.O.; Park, C.S. Using Amylosucrase for the Controlled Synthesis of Novel Isoquercitrin Glycosides with Different Glycosidic Linkages. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2020, 68, 13798–13805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.H.; Yoo, S.H.; Choi, S.J.; Kim, Y.R.; Park, C.S. Versatile biotechnological applications of amylosucrase, a novel glucosyltransferase. Food Science and Biotechnology 2020, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, D.H.; Jung, J.H.; Ha, S.J.; Cho, H.K.; Jung, D.H.; Kim, T.J.; Baek, N.I.; Yoo, S.H.; Park, C.S. High-yield enzymatic bioconversion of hydroquinone to alpha-arbutin, a powerful skin lightening agent, by amylosucrase. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2012, 94, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.K.; Kim, H.H.; Seo, D.H.; Jung, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Baek, N.I.; Kim, M.J.; Yoo, S.H.; Cha, J.; Kim, Y.R.; et al. Biosynthesis of (+)-catechin glycosides using recombinant amylosucrase from Deinococcus geothermalis DSM 11300. Enzyme Microbiology and Technology 2011, 49, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.D.; Jung, D.H.; Seo, D.H.; Jung, J.H.; Seo, E.J.; Baek, N.I.; Yoo, S.H.; Park, C.S. Acceptor specificity of amylosucrase from Deinococcus radiopugnans and its application for synthesis of rutin derivatives. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2016, 26, 1845–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.R.; Rha, C.S.; Jung, Y.S.; Choi, J.M.; Kim, G.T.; Jung, D.H.; Kim, T.J.; Seo, D.H.; Kim, D.O.; Park, C.S. Enzymatic modification of daidzin using heterologously expressed amylosucrase in Bacillus subtilis. Food Science and Biotechnology 2019, 28, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rha, C.S.; Kim, E.R.; Kim, Y.J.; Jung, Y.S.; Kim, D.O.; Park, C.S. Simple and efficient production of highly soluble daidzin glycosides by amylosucrase from Deinococcus geothermalis. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2019, 67, 12824–12832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, A.T.; Jang, D.; Kim, M.S.; Seo, D.H.; Nam, T.G.; Rha, C.S.; Park, C.S.; Kim, D.O. Enrichment of polyglucosylated isoflavones from soybean isoflavone aglycones using optimized amylosucrase transglycosylation. Molecules 2020, 25, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.-Y.; Wang, T.-Y.; Wu, J.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-L.; Chang, T.-S. Enzymatic synthesis of novel and highly soluble puerarin glucoside by Deinococcus geothermalis amylosucrase. Molecules 2022, 27, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-M.; Wang, T.-Y.; Wu, J.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-R.; Lin, S.-Y.; Chang, T.-S. Production of new isoflavone diglucosides from glycosylation of 8-hydroxydaidzein by Deinococcus geothermalis amylosucrase. Fermentation 2021, 7, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Ding, H.Y.; Luo, S.Y.; Wang, T.Y.; Tsai, Y.L.; Chang, T.S. Novel glycosylation by amylosucrase to produce glycoside anomers. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, S.; Annadurai, S.; Abullais, S.S.; Das, G.; Ahmad, W.; Ahmad, M.F.; Kandasamy, G.; Vasudevan, R.; Ali, M.S.; Amir, M. Glycyrrhiza glabra (Licorice): A comprehensive review on its phytochemistry, biological activities, clinical evidence and toxicology. Plants (Basel) 2021, 10, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strategy | Enzyme | Precursor | Novel Product | Property of the New Compounds | Illustration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

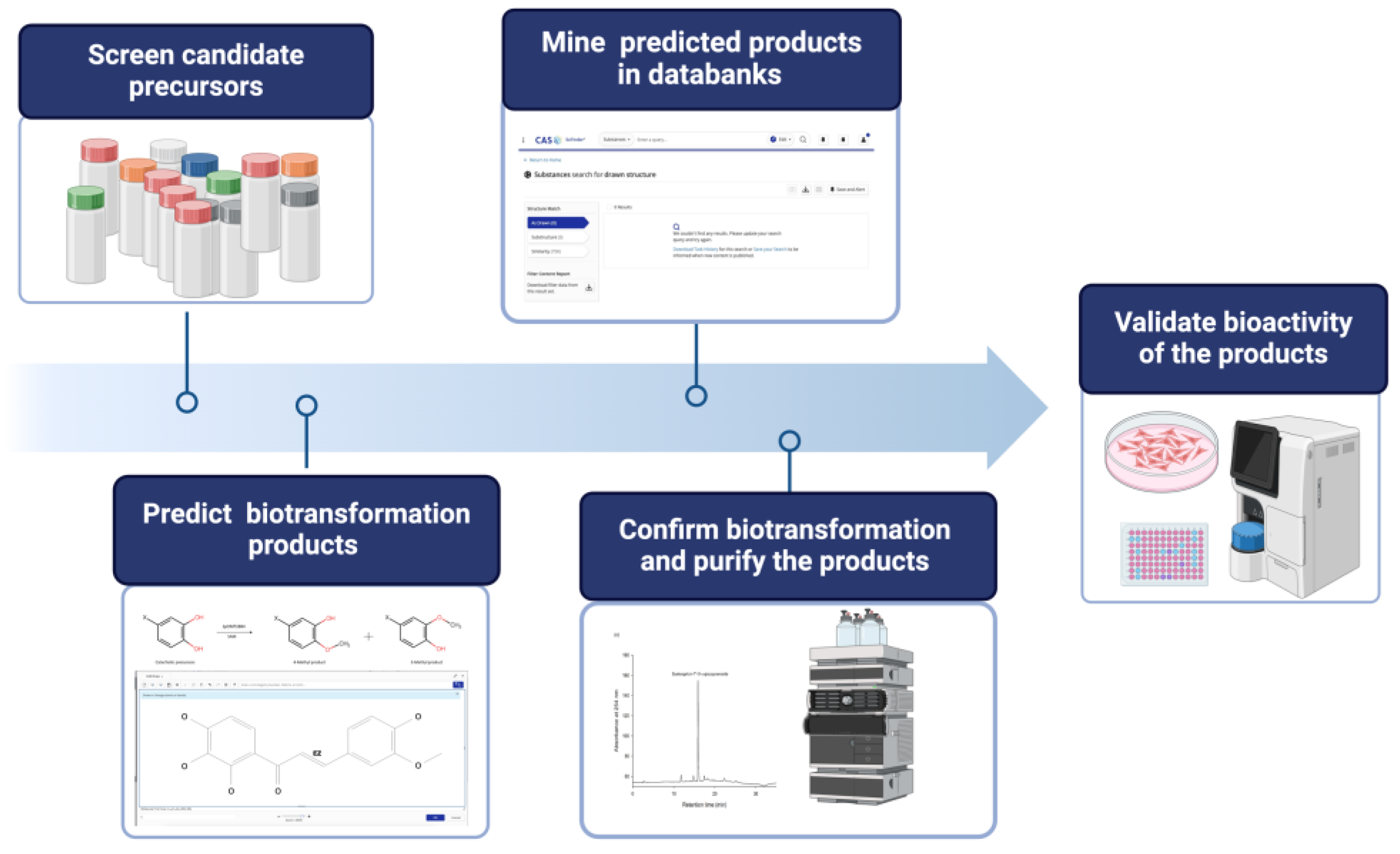

| Predicted data mining approach (PDMA) | BmTYR1,2 | Loureirin A Loureirin B |

3’-Hydroxyloureirin A 3’-Hydroxyloureirin B |

Improve both antioxidant and anti-α-glucosidase activity | Figure 3 | [8] |

| BmTYR | Isoxsuprine | 3’’-Hydroxyisoxsuprine | Improve both antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity | Figure 3 | [9] | |

| BsUGT4891,3 | Corylin | Corylin-7-O-β-glucoside | Improve both anti-inflammatory and anti-melanoma activity | Figure 4 | [10] | |

| BsUGT489 | Skullcapflavone II | Sullcapflavone II-6’-O-β-glucoside | Improve both solubility and anti-melanoma activity | Figure 4 | [11] | |

| SpOMT28841,4 | Plantagoside | 4′-O-Methyl plantagoside 5′-O-Methyl plantagoside |

No mention | Figure 5 | [12] | |

| Biotransformation-guided purification (BGP) | BsUGT489 | Ganoderma extract | Ganoderic acid C2-3-O-β-glucoside | Improve solubility and maintain anti-α-glucosidase activity | Figure 7 | [13] |

| DgAS1,5 | Baizhi herb | Byakangelicin-7’’-O-α-glucoside | Improve solubility | Figure 8 | [14] | |

| BmTYR | Ha-Soo-Oh herb | 2,3,5,3′,4′-Pentahydroxystilbene-2-O-β-glucoside | Improve antioxidant activity | Figure 9 | [15] | |

| BmTYR | Licorice herb | Butin | Improve antioxidant activity | Figure 9 | [16] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).