1. Introduction

Polypharmacy amongst patients with CLD has emerged as one of the rising therapeutic challenges encountered in the management of these patients (1)(2,3). Unlike the general population, there fewer studies examining the exact clinical case burden of polypharmacy amongst these patients’ cohorts. Its exact prevalence is variable but has been estimated to range between 12 to 35% (4). Additionally, despite its central role in drug metabolism, the consequences of rising medications count per patient on the liver hasn’t been exhaustively studied (3,5,6). Mechanistic Studies have shown that increasing medication counts per patient in cohorts with CLD is associated with a downstream risk (including drug-drug and drug-food interactions, adverse drug reactions) (4) (7). Of these risks, medication-related problems (MRPs) represent by far the most pressing, rising, and preventable cause of liver therapeutic morbidities (2,3). Patients with CLD usually take a combination of drugs due to various indications. These includes those related to the primary cause of CLD, complications resulting from decompensation, as well as some other non-hepatic morbidities these patients’ patients may have to take. In the general population a numerical threshold of ≥5 drugs are generally referred to as polypharmacy. Until recently, the exact threshold that constitutes polypharmacy in patients with CLD has remained a subject of unresolved debate. Danjuma et al recently reported on a systematic review that suggested a threshold of ≥5 drugs as constituting polypharmacy in these cohorts of patients (4). Despite this, the exact impact of polypharmacy on liver related clinical outcomes (such as all-cause mortality, rates of hospitalisation, and intensive care unit (ICU) admissions) remains unexplored. Some primary liver diseases such as hepatitis C and its sequelae (including hepatocellular carcinoma) have now well-established therapeutics that have been shown to significantly reduce mortality in these cohorts of patients (12–15). However, what has remained uncertain is the overall impact of total medication count (liver and non-liver related) on hard clinical endpoints. There is therefore residual uncertainty and the lack of clarity regarding the differential impact of polypharmacy fractions (liver and non-liver related polypharmacy) on critical downstream outcomes such as rates of hospitalization, LOS, critical care admissions and death. Patients with CLD have at baseline a disproportionately high mortality burden compared to those with other organ-specific morbidities (9–11). it is probable that exacerbating this baseline risk matrix with additional therapeutic risks such as rising medication counts will likely result in several unmeasured adverse clinical outcomes. Having a comprehensive understanding of the impact of liver and non-liver-related polypharmacy on “hard” clinical endpoints will not only assist in risk stratification but also strengthen the need for a thorough fool-proof framework for aggressive drug reconciliation in these cohorts of patients.

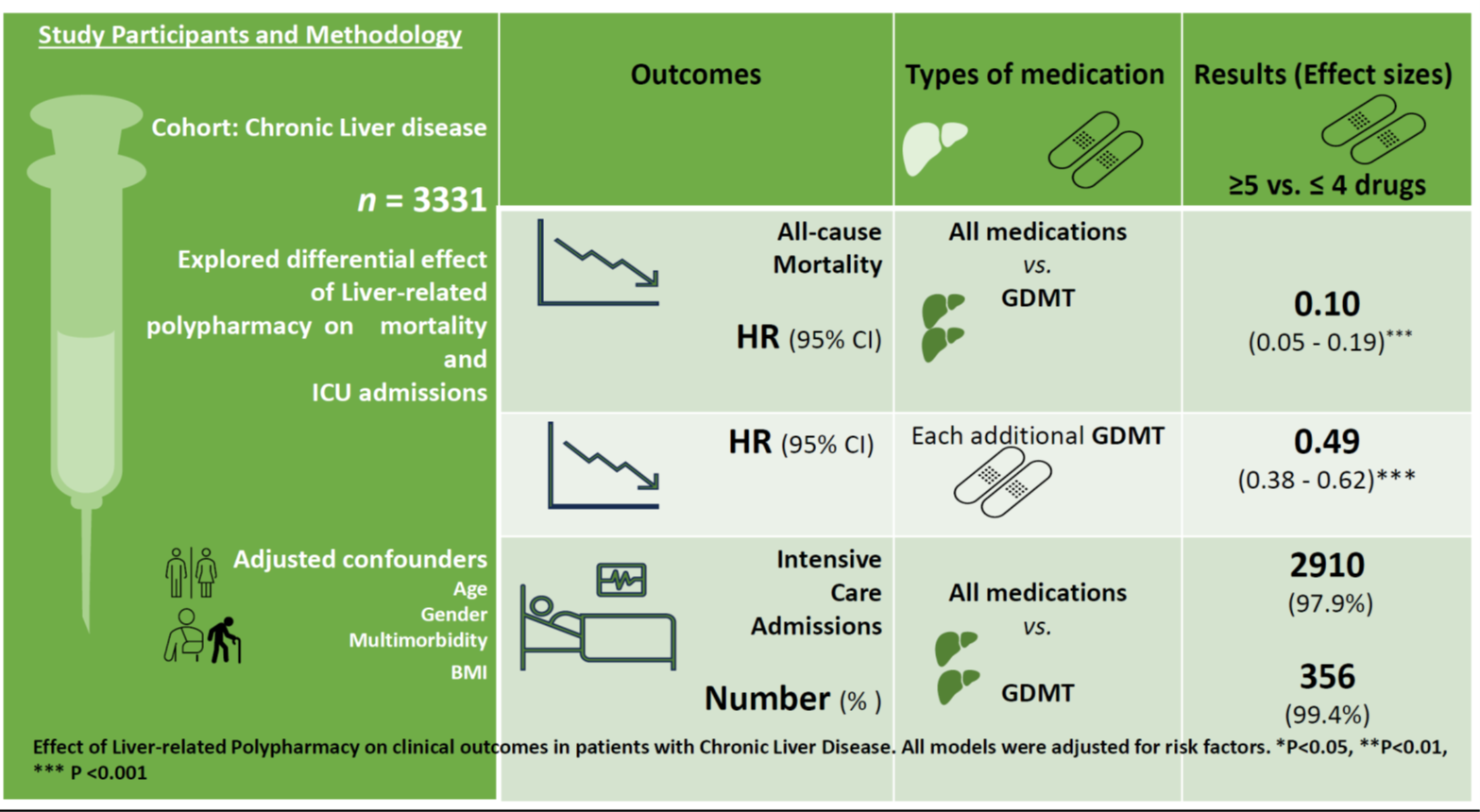

In this study, we have set out to examine clinical phenotypes of polypharmacy in patients with CLD and the effect of each of these distinct phenotypes on the risk of adverse outcomes such as ICU admissions and death.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This is a retrospective cohort study that examined patients receiving care at tertiary care centres within the Weill Cornell Medicine-affiliated Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha Qatar between October 2018 to August 2021. Data was extracted from an online patient repository database (Cerner®) which keeps socio-demographic parameters as well as prescription records. Variables included in the analyses include age, gender, ethnicity, number, and types of long-term conditions, Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), serum albumin, Prothrombin time, number of admissions, length of hospital stay, intensive care admission. Others include the number of each patient’s medication and body mass index (BMI). The study is reported based on STROBE reporting guidelines (11).

2.2. Participants

The patient population was comprised of participants with confirmed diagnoses of CLD who were admitted (for both CLD and non-CLD related reasons) and managed in inpatient wards. The care model of CLD inpatient care in HMC requires admission to general medical wards for both general medical and CLD-related-morbidities with in-reach inputs from specialist hepatologists. We included prescription records of patients in this study stored in the online repository database rather than recent prescription records so that the entire range of patient prescriptions could be adequately accounted for.

2.3. Ethics Declarations

All study documentation including consent to use collected data as reviewed and approved by the independent research board of the Medical Research committee (Hamad Medical Corporation). (MRC-01-21-937).

2.4. Medications

We included all medications patients have been taking for the past 4 months. This includes medications for the management of primary cause of CLD, management of complications of CLD, as well as other medications as part of the prescription for associated long-term conditions. All medications included in this study had undergone pharmacy-led drug reconciliation [consistent with Beers (16) and STOPP Criteria] at all clinical encounters associated with every single patient visit, ensuring accuracy and consistency in medication records.

2.5. Drug Classification

We utilized the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system (17) to categorize all drugs encountered in the study into distinct therapeutic classes. Specifically, we used the following ATC codes to classify “liver-specific” medications; A05, and A05B (supplementary table 4).

2.6. Long Term Conditions (LTC’s)

We considered the following LTC’s: ischemic heart disease (IHD), type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), stroke and stroke-related outcomes, and chronic arthritic morbidities. Only LTC’s with records of confirmation by internationally recognized diagnostic standards and benchmarks were included in the study. For example, we defined CKD according to the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration Equation (CKD-EPI) definition as creatinine clearance < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (18); Diabetes mellitus was defined as a glycated haemoglobin level ≥ 6.5%, and or use of antihyperglycemic drugs or insulin (except where they have had these prescriptions based on other morbidities other than Diabetes mellitus).

2.7. Case Ascertainment and Definitions

We defined the following in this study.

Minor Polypharmacy was defined as the intake of 2-3.

Moderate Polypharmacy was defined as the intake of 4-5.

Major polypharmacy was defined as the intake of ≥5 drugs.

Non-liver related polypharmacy was defined as intake of ≥5 non-liver related medications.

Hyper polypharmacy refers to the intake of ≥10 medications.

Mortality was defined as death due to all causes within the hospital during index admission, or 30 days after discharge.

Significant LTC refers to patients with ≥ 3 LTCs.

We defined prolonged LOS as a hospital stay that was greater than the 75th percentile for the specific diagnostic entity (upper-quartile LOS).

2.8. Statistical Analyses

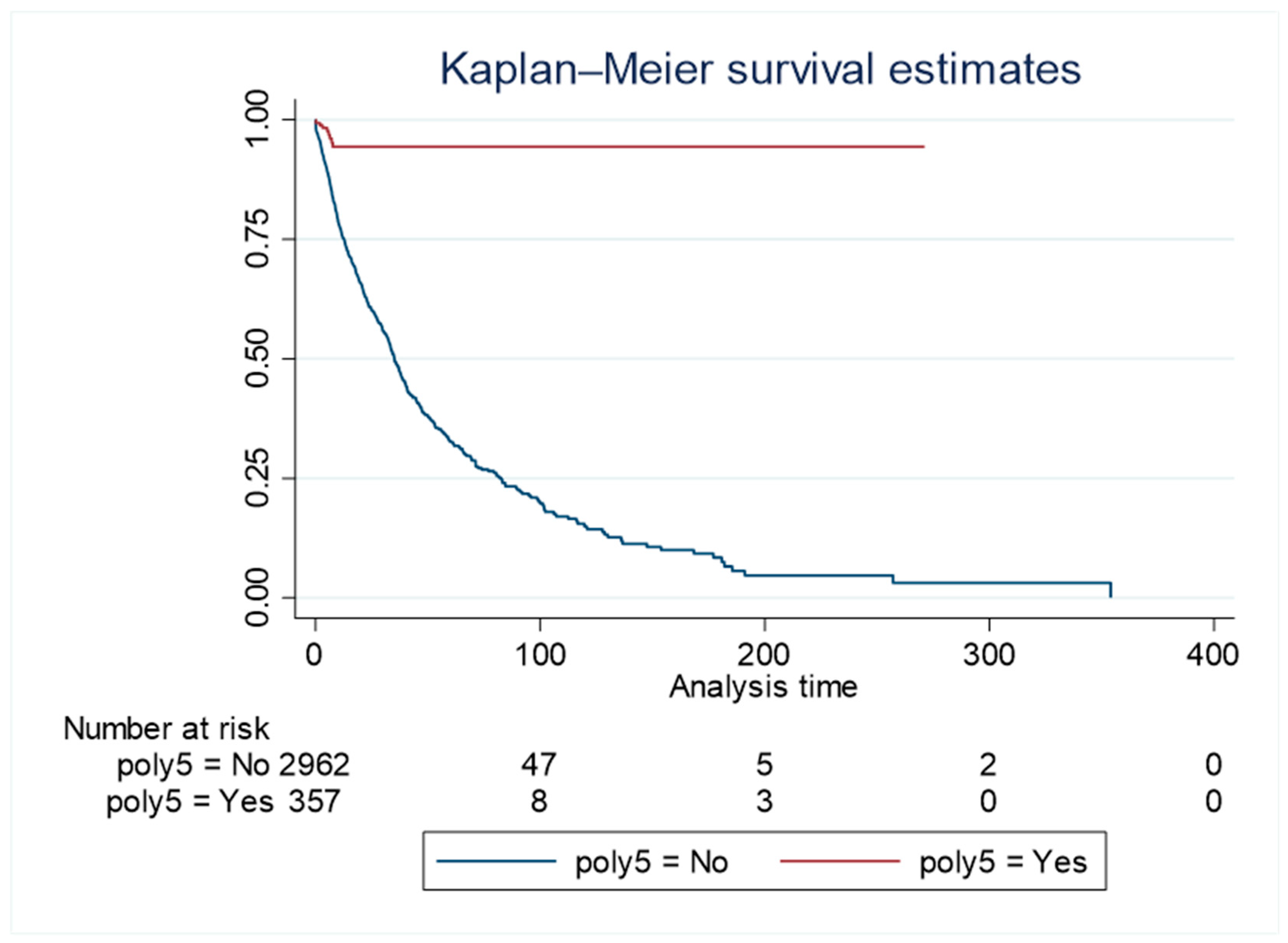

In descriptive analyses, frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables and mean and standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range) for numerical variables (depending on the distribution). Chi-square tests were used to compare category variables for individuals who died and those who were alive, while t-tests were used to test hypotheses for numerical variables. The null hypothesis (H₀) assumes no significant difference in the mean values of comparison groups (patients with and without polypharmacy), while the alternative hypothesis (H₁) assumes a significant difference exists. Kaplan Meier survival curves were used to display and compare survival by polypharmacy status with survival time measured from hospitalization to death, or date of last follow-up, for censoring. Cox regression was used for computing the hazards of death with the number of CLD medications as a continuous variable first and then categorized into polypharmacy categories of ≥5 drugs and ≥10 drugs. We adjusted for confounders (age, BMI, and gender) and prognostic variables which were mostly comorbid conditions. The final model included age, gender, number of CLD medications, cancer, cardiovascular disease, CLD, diabetes mellitus, BMI, CKD, stroke or neural conditions, and organ transplant. Adjusted HRs were reported as effect measures, together with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Exact p-values were reported and interpreted as evidence against the null hypothesis.

3. Results

3.1.1. Study Population Charateristics

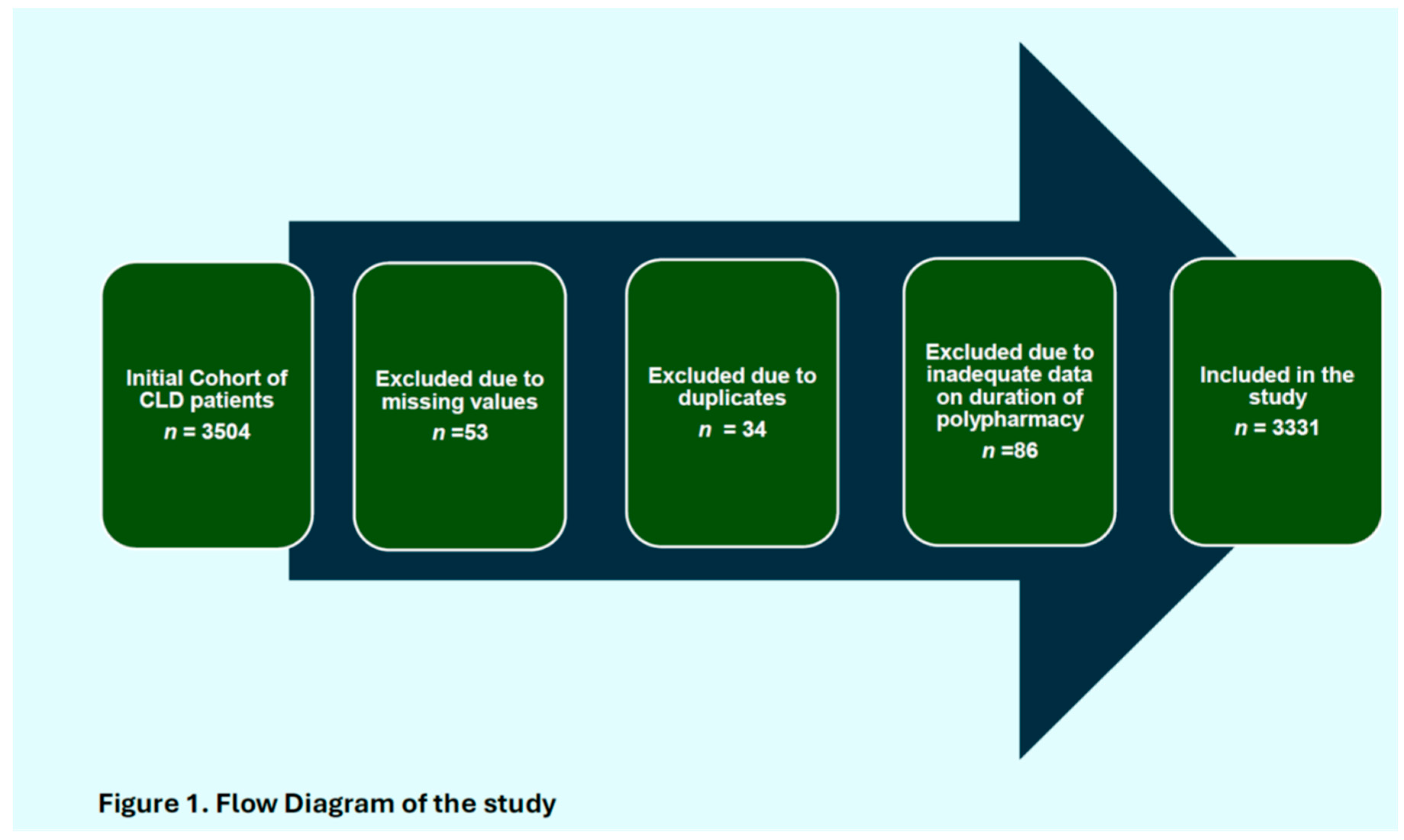

A total of 3331 participants meeting the inclusion criteria were included in the analyses (Figure 1). The median age of the study population was 50 years (interquartile range [IQR] 40–63), of these about 71.0% (n = 2 366) were males. Table 1. The median model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score was 9 ([7–12]); with a comparatively high risks patients amongst those that died (11 [8–14]), compared to survivors (7 [6–10]). About a third (20.71%, n = 690) of the study population were comprised of patients with metabolic-associated steatohepatitis (MASH): 19.6% (n = 665) Hepatitis B; 2.1%; 19.33% (n = 644) Autoimmune Hepatitis; 10.09 % (n = 336) Hepatitis C; whilst 19.99% (n = 666) were comprised of patients with chronic liver disease due to other aetiologies.(supplementary table 3). The most common comorbidities were adverse cardiovascular outcomes (37.6%), with the proportion of participants with hypertension, or type 2 diabetes mellitus at 35.1% and 26.2%, respectively. A total of 762 (22.9%) individuals died during the study period. Compared to those who were alive at the end of the study period, individuals who died were significantly older (mean age 59.1 years [SD 16.7] vs. 46.6 years (SD 14.9), respectively, p < 0.001) and were more likely to have a higher number of comorbidities (

Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of the study.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of the study.

3.1.3. Comparison of Length of Hospitalization, Length of ICU Stays, and Death by Polypharmacy Groups

Out of the total study participants, 358 (12.0%) had polypharmacy, with a significantly higher proportion of deaths, 753 (25.3%) amongst patient cohorts without polypharmacy, compared to 9 (2.5%) in the group with polypharmacy (p<0.01). There were comparable proportion of ICU admissions between the two polypharmacy groups (

Table 2).

3.1.4. Comparison of Survival by Polypharmacy Groups

The total duration of follow-up for the whole cohort was 42 772.6 person-days, with a higher follow-up duration (38 393.1 person-days) in the group without liver-related polypharmacy compared to the group with liver-related polypharmacy (4 379.5 person-days). The Kaplan Meier survival curve showed a higher survival rate over time in the polypharmacy group inclusive of liver-related medications compared to the group without polypharmacy (log-rank p<0.001, incidence of 0.02 (95% CI 0.02-0.2) in the polypharmacy group and 0.002 (95%CI 0.001 – 0.004) in the group without polypharmacy, respectively

Figure 2).

3.1.5. Association Between Polypharmacy and Mortality

Liver-related polypharmacy was associated with a significant reduction in mortality risk. Individuals receiving polypharmacy, including both liver- and non-liver-related medications, had approximately a 90% lower hazard of death compared to those without polypharmacy (HR 0.10, 95% CI 0.05–0.19). In additional analyses, with the medications entered as a total number of medications per individual, each additional medication conferred a protective effect against the hazards of death (HR 0.49, 95%CI 0.38 - 0.62), again with strong evidence against the null hypothesis at the study’s sample size (P<0.001) (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 2).

4. Discussion

In this examination of real-world data of patients with CLD attending a tertiary medical center, we found a lower proportion of deaths among patients with combined liver-specific and general polypharmacy compared to their age and gender-matched cohorts with no polypharmacy. Over a combined follow-up period of 42 772.6 person-days, study cohorts with polypharmacy (combined liver and non-liver specific) had about 90% reduction in the hazards of death. This represents the first report to our knowledge exploring the nexus between denominated medication counts (organ and non-organ specific) with differential survival outcomes in these patient cohorts. This finding adds to our understanding of the emerging role of various clinical polypharmacy therapeutic sub-classes in understanding the interaction between increasing medication counts and mortality (19). Although previous studies have explored some of the themes of polypharmacy in patients with CLD such as polypharmacy and drug-drug interactions (4), (20), (1), health-related quality of life (QoL) (21) (23), no previous studies have explicitly examined the exact nexus between medication counts and mortality in these cohorts of patients. Even in the limited cases where these themes were explored at all (22), studies instead have focused on the risk of developing liver disease or liver-related biochemical abnormalities due to polypharmacy, rather than mortality-related consequences of polypharmacy in the setting of liver disease (1-4). The recent report by Farooq et al (23) for example examined the impact of rising medication counts on quality of life, with CLD patients on moderate polypharmacy having a lower quality of life compared to those on other medication thresholds (P < 0.05). Hanai et al’s examination of a Japanese database of 239 patient cohorts with Liver cirrhosis reported on the interrelationship between polypharmacy, sarcopenia, and their combined effects on the risk of death (24). In their report, polypharmacy (HR,1.83; 95% CI, 1.01–3.37), sarcopenia (HR, 2.00;95% CI,1.12–3.50) independently predicted risks of death amongst cirrhotic patients (24). The lack of a clear categorization of liver-related and non-liver-related polypharmacy in the study by Hanai et al, and others meant that a direct inference could not be drawn on which of the pheno-groups of polypharmacy was responsible for the adverse point estimates of mortality reported in these studies. The novelty of our approach lies in its exploration and confirmation of the exact burden/effect of these pheno-groups on “hard clinical end points (such as actuarial survival) in these patient cohorts. The traditional paradigm derived mostly from previous studies has always been that rising medication counts were associated with reduced survival (25,26)(27)(28). A unifying feature of these studies have been their consideration of polypharmacy as a homogenous therapeutic phenotype with no functional dichotomy into disease and non-disease-specific sub-types. The implication of this has been discordant point estimates from disparate reports exploring this therapeutic morbidity; often resulting in persistent uncertainty regarding the exact association between rising medication counts and mortality in these cohorts of patients (25,26,28). The outcome of our study clearly suggests that both the numerical count, as well as the constituent of this count were equally important, with the latter perhaps more determinative than a simple numerical threshold. The importance of this emerging dichotomy was further highlighted in a recent report from an observational study examining various pheno-groups of polypharmacy vis-à-vis mortality outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure (19). This study for the first time reported that patient cohorts with excessive polypharmacy (≥9 medications) comprising of both guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) as well as other medications had the highest probability of survival up to 1.6 years compared to those with lower medication thresholds (≤4). In this study the mortality rate decreased by 18% for chronic heart failure patients with excessive polypharmacy [HR=0.82, 95% CI: 0.71 - 0.94]). Interestingly, patients with non-GDMT-related polypharmacy had increased risks of ICU admissions in this study (aOR=1.78, 95% CI: 1.13 - 2.70). The latter further highlights the clear divergence in adverse outcomes between the two sub-classes of polypharmacy. Depending on the nature of the primary cause of the CLD, patients are often on a cocktail of medications, some of which have proven survival benefits. The latter could potentially positively skew survival estimates when incorporated into patients’ treatment regimens. Direct-acting antiviral agents (DAA) for example have been conclusively shown to improve both morbidity and mortality matrices in patients with hepatitis C viral infection (14,15).

Regardless of underlying disease-related morbidity, but more so in patients with CLD, hospitalization and the increased LOS following this often contribute significantly to the overall morbidity and mortality burden of these patients (29). When we explored the effect of LOS stay between patients with both liver-specific and general polypharmacy, we found no difference in mortality matrices between the two groups. It is noteworthy that the LOS was analogous between the group with polypharmacy and the group without polypharmacy. (

Table 2). The probable reason for this outcome is multifactorial. Firstly, this could suggest that the presence of polypharmacy did not significantly impact the severity or duration of hospitalization for patients with CLD. Secondly, only a small number of patients with polypharmacy were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), which could indicate that the use of multiple medications (especially those that are GDMT) did not significantly increase the risk of critical illness or need for advanced medical care in this population. Other factors include the severity of CLD (often expressed by prognostic scores such as MELD) which invariably has a direct impact on survival outcomes regardless of the primary reason for admission. Furthermore, the primary reason for hospitalization (which may not be liver-related), as well as the quality of inpatient care, and the effectiveness of interventions received could wholly collectively impact mortality outcomes.

It is noteworthy that though our entire study cohort was comprised of hospitalized patients, medication misadventure or outright drug-related harm due to polypharmacy is not limited to hospitalized patients alone (2). This perspective was first articulated in the work reported by Hayward et al in their attempt to explore the exact impact of MRPs on patient outcomes in an outpatient ambulatory care setting. This study carried out a randomized evaluation of a pharmacist-led, patient-oriented medication education intervention over a 12-month follow-up period. The risk of possible harm attributable to MRPs was found to be low in 18.9% of episodes, medium in 33.1%, and high in 48.0% (31). The determination and adjudication of risks of possible harm was carried out using a risk matrix tool by a designated panel of clinicians. Additionally, this study reported a higher incidence rate of high-risk MRPs in patient cohorts with a higher Child-Pugh score (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.31; 95% CI, 1.09-1.56); greater comorbidity burden (IRR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.02-1.29). Perhaps denoting the effect of liver decompensation on the ability to handle therapeutic agents.

4.1. Strengths

This is the first attempt to our knowledge at a comprehensive examination of the exact interplay between organ and non-organ-specific polypharmacy and adverse clinical outcomes in patients with CLD. These findings provide new insights into the use of multiple medications in patients with CLD and may help to inform clinical decision-making when it comes to medication management in this population. The findings were notable in the context of recently published reports on polypharmacy in patients with CLD, as they suggest that the use of multiple medications may not always be associated with negative outcomes in this population (19). However, it is important to note that this study only included a specific population of patients with CLD, and further research is needed to better understand the risks and benefits of polypharmacy in this and other populations, especially the impact of the primary cause of CLD on polypharmacy driven morbidity and mortality outcomes. Despite the study period overlapping those of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, sub-group analyses did not establish any additional impact of COVID-19-related mortality on the study's overall mortality point estimate.

4.2. Limitations

Although we defined the duration of drug exposure, our study is limited by the lack of additional data on individual study participants' concordance with those medications (Figure 3). The reliance on medication refill as a surrogate marker for medication concordance may confound some of our study findings. We will additionally concede that the disproportionately higher number of deaths in the pheno-group without polypharmacy (although adjusted for age, gender, and multimorbidity) could have still been influenced by the severity of CLD amongst other factors. This will need further exploration through future studies. These, notwithstanding, the certainty around the point estimates of our key study findings is unlikely to be significantly impacted by this.

5. Conclusions

In a hospitalized cohort of patients with CLD, liver-related polypharmacy was associated with increased rates of survival. However, the role of non-liver-related medications in this context remains unclear, and it is uncertain how the primary cause of liver disease could have potentially impacted these outcomes. Further studies exploring these factors are needed to better inform clinical decision-making regarding polypharmacy management in this patient population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1

Table 1 – Comparison of multimorbidity by survival; S2

Table 2: S2

Table 2 – Association between the number of CLD medications and hazards of death: S3 Table 3: Showing the relative proportion of various diagnostic groups of the study population: S4 Table 4: The relative distribution of various drug classes amongst the study cohort: Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and approved the manuscript. M I D: study concept development, grant acquisition, liaison with the ethics committee, literature search, data interpretation, and preparation of initial and final drafts. MK: Literature search, data curation, data classification, preparation of initial and final manuscript draft. LN: Literature search, data curation classification, preparation of final manuscript drafts. BA: Literature search, data curation classification, preparation of final manuscript drafts AA: Literature search, data curation classification, preparation of final manuscript drafts MN: data curation classification, preparation of final manuscript drafts SA: Literature search, data curation classification, preparation of final manuscript drafts NA: data curation classification, preparation of final manuscript drafts DA: Study registration, data analyses, data interpretation, preparation of final manuscript drafts ALI: data curation classification, preparation of final manuscript drafts TC: Study concept development, Data analyses and interpretation, and preparation of initial and final drafts. LNA: data curation classification, analyses preparation of final manuscript drafts RM: data curation classification, preparation of final manuscript drafts RA: data curation, preparation of initial and final manuscript drafts ASF: data curation classification, preparation of final manuscript drafts MAA: data curation classification, data interpretation, preparation of final manuscript drafts

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Documentation relating to the study Protocol as well as consents for access to patient-level data for the study were submitted and underwent rigorous review by the independent review panel of the medical research centre (MRC) Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha Qatar. Approval for access to this data was subsequently granted. (MRC-01-21-937)

Informed Consent Statement

Any research. Patient consent was waived because all documentation relating to the study protocol as well as consent for access to patient-level data for the study were submitted and underwent rigorous review by the independent review panel of the medical research centre (MRC) Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha Qatar. Approval of access to this data was subsequently granted.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CLD |

Chronic Liver Disease |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| HR |

Hazard Ratio |

| LOS |

Length of Stay |

| ICU |

Intensive Care Unit |

| MRP |

Medication-Related Problem |

| GDMT |

Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| ALT |

Alanine Aminotransferase |

| eGFR |

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| LTC |

Long-Term Condition |

| CKD |

chronic kidney disease |

| IHD |

ischemic heart disease |

| ATC |

Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System |

| MELD |

Model for End-stage Liver Disease |

| MASH |

Metabolic-Associated Steatohepatitis |

| QoL |

Quality of Life |

| DAA |

Direct-Acting Antiviral |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| STROBE |

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| HRs |

Hazard Ratios |

| STOPP |

Screening Tool of Older Persons' Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions |

| IRR |

Incidence Rate Ratio |

References

- Elzouki AN, Zahid M, Akbar RA, Alfitori GB, Cherichi Purayil S, Imanullah R, Danjuma MI. Polypharmacy and drug interactions amongst cirrhotic patients discharged from a tertiary center: Results from a national quality improvement audit. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2020 Dec;21(4):216-218. [CrossRef]

- Villén N, Guisado-Clavero M, Fernández-Bertolín S, Troncoso-Mariño A, Foguet-Boreu Q, Amado E, Pons-Vigués M, Roso-Llorach A, Violán C. Multimorbidity patterns, polypharmacy and their association with liver and kidney abnormalities in people over 65 years of age: a longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr. 2020 Jun 12;20(1):206. [CrossRef]

- Hayward KL, Patel PJ, Valery PC, Horsfall LU, Li CY, Wright PL, Tallis CJ, Stuart KA, Irvine KM, Cottrell WN, Martin JH, Powell EE. Medication-Related Problems in Outpatients with Decompensated Cirrhosis: Opportunities for Harm Prevention. Hepatol Commun. 2019 Mar 18;3(5):620-631. [CrossRef]

- Danjuma MI, Naseralallah L, Ansari S, Al Shebly R, Elhams M, AlShamari M, Kordi A, Fituri N, AlMohammed A. Prevalence and global trends of polypharmacy in patients with chronic liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023 May 12;102(19): e32608. [CrossRef]

- Hayward KL, Valery PC, Cottrell WN, Irvine KM, Horsfall LU, Tallis CJ, Chachay VS, Ruffin BJ, Martin JH, Powell EE. Prevalence of medication discrepancies in patients with cirrhosis: a pilot study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016 Sep 13;16(1):114. [CrossRef]

- Patel PJ, Hayward KL, Rudra R, Horsfall LU, Hossain F, Williams S, Johnson T, Brown NN, Saad N, Clouston AD, Stuart KA, Valery PC, Irvine KM, Russell AW, Powell EE. Multimorbidity and polypharmacy in diabetic patients with NAFLD: Implications for disease severity and management. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017 Jun;96(26): e6761. [CrossRef]

- Jaeschke H, Gores GJ, Cederbaum AI, Hinson JA, Pessayre D, Lemasters JJ. Mechanisms of hepatotoxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2002 Feb;65(2):166-76. [CrossRef]

- Torgersen J, Mezochow AK, Newcomb CW, Carbonari DM, Hennessy S, Rentsch CT, Park LS, Tate JP, Bräu N, Bhattacharya D, Lim JK, Mezzacappa C, Njei B, Roy JA, Taddei TH, Justice AC, Lo Re V 3rd. Severe Acute Liver Injury After Hepatotoxic Medication Initiation in Real-World Data. JAMA Intern Med. 2024 Aug 1;184(8):943-952. [CrossRef]

- Devarbhavi H, Asrani SK, Arab JP, Nartey YA, Pose E, Kamath PS. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J Hepatol. 2023 Aug;79(2):516-537. [CrossRef]

- Henry L, Paik J, Younossi ZM. Review article: the epidemiologic burden of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease across the world. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022 Sep;56(6):942-956. [CrossRef]

- Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Gøtzsche PC, Pocock SJ, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007. e296. [CrossRef]

- Mendizabal M, Piñero F, Ridruejo E, Herz Wolff F, Anders M, et al.; Latin American Liver Research; Educational and Awareness Network (LALREAN). Disease Progression in Patients with Hepatitis C Virus Infection Treated with Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Oct;18(11):2554-2563.e3. [CrossRef]

- Singal AG, Rich NE, Mehta N, Branch AD, Pillai A, et al., Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy for Hepatitis C Virus Infection Is Associated with Increased Survival in Patients with a History of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2019 Nov;157(5):1253-1263.e2. [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen JC, Nielsen EE, Feinberg J, Katakam KK, Fobian K, Hauser G, Poropat G, Djurisic S, Weiss KH, Bjelakovic M, Bjelakovic G, Klingenberg SL, Liu JP, Nikolova D, Koretz RL, Gluud C. Direct-acting antivirals for chronic hepatitis C. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Sep 18;9(9):CD012143. [CrossRef]

- Kalidindi Y, Jung J, Feldman R, Riley T 3rd. Association of Direct-Acting Antiviral Treatment with Mortality Among Medicare Beneficiaries with Hepatitis C. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Jul 1;3(7): e2011055. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher P, O'Mahony D. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons' potentially inappropriate Prescriptions): application to acutely ill elderly patients and comparison with Beers' criteria. Age Ageing. 2008 Nov;37(6):673-9. [CrossRef]

- WHOCC—ATC/DDD Index. [(accessed on 23 June 2024)]. Available online: https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/?code=J01&showdescription=no.

- Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration). A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009 May 5;150(9):604-12. [CrossRef]

- Danjuma MI, Sukik AA, Aboughalia AT, Bidmos M, Ali Y, Chamseddine R, Elzouki A, Adegboye O. In patients with chronic heart failure which polypharmacy pheno-groups are associated with adverse health outcomes? (Polypharmacy pheno-groups and heart failure outcomes). Curr Probl Cardiol. 2024 May;49(5):102194. [CrossRef]

- Fagiuoli S, Toniutto P, Coppola N, Ancona DD, Andretta M, Bartolini F, Ferrante F, Lupi A, Palcic S, Rizzi FV, Re D, Alvarez Nieto G, Hernandez C, Frigerio F, Perrone V, Degli Esposti L, Mangia A. Italian Real-World Analysis of the Impact of Polypharmacy and Aging on the Risk of Multiple Drug-Drug Interactions (DDIs) in HCV Patients Treated with Pangenotypic Direct-Acting Antivirals (pDAA). Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2023 Jan 18; 19:57-65. [CrossRef]

- Alrasheed M, Guo JJ, Lin AC, Wigle PR, Hardee A, Hincapie AL. The effect of polypharmacy on quality of life in adult patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States. Qual Life Res. 2022 Aug;31(8):2481-2491. [CrossRef]

- Stingl, J. C., & Viviani, R. (2025). Pharmacogenetic guided drug therapy – how to deal with phenoconversion in polypharmacy. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Farooq J, Sana MM, Chetana PM, Almuqbil M, Prabhakar Bhat N, Sultana R, Khaiser U, Mohammed Basheeruddin Asdaq S, Almalki MEM, Mohammed Sawadi Khormi A, Ahmad Albraiki S, Almadani ME. Polypharmacy in chronic liver disease patients: Implications for disease severity, drug-drug interaction, and quality of life. Saudi Pharm J. 2023 Aug;31(8):101668. [CrossRef]

- Hanai T, Nishimura K, Miwa T, Maeda T, Imai K, Suetsugu A, Takai K, Shimizu M. Prevalence, association, and prognostic significance of polypharmacy and sarcopenia in patients with liver cirrhosis. JGH Open. 2023 Feb 12;7(3):208-214. [CrossRef]

- Cashion W, McClellan W, Judd S, Goyal A, Kleinbaum D, Goodman M, Prince V, Muntner P, Howard G. Polypharmacy and mortality association by chronic kidney disease status: The REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke Study. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2021 Aug;9(4): e00823. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Zhang X, Yang L, Yang Y, Qiao G, Lu C, Liu K. Association between polypharmacy and mortality in the older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022 May-Jun; 100:104630. [CrossRef]

- Midão L, Brochado P, Almada M, Duarte M, Paúl C, Costa E. Frailty Status and Polypharmacy Predict All-Cause Mortality in Community Dwelling Older Adults in Europe. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Mar 30;18(7):3580. [CrossRef]

- Chang TI, Park H, Kim DW, Jeon EK, Rhee CM, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kang EW, Kang SW, Han SH. Polypharmacy, hospitalization, and mortality risk: a nationwide cohort study. Sci Rep. 2020 Nov 3;10(1):18964. [CrossRef]

- Davies LE, Kingston A, Todd A, Hanratty B. Is polypharmacy associated with mortality in the very old: Findings from the Newcastle 85+ Study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022 Jun;88(6):2988-2995. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).