Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

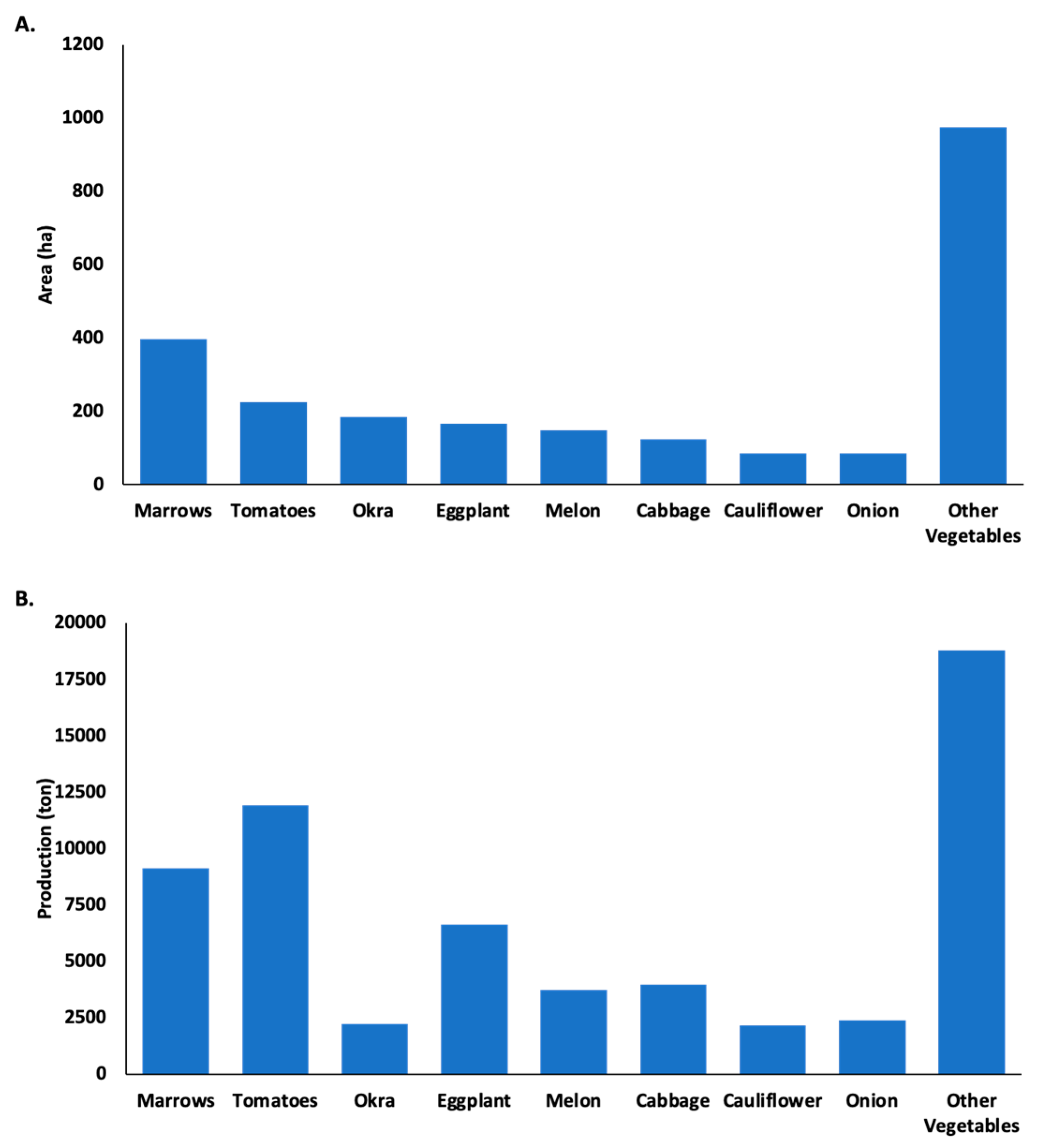

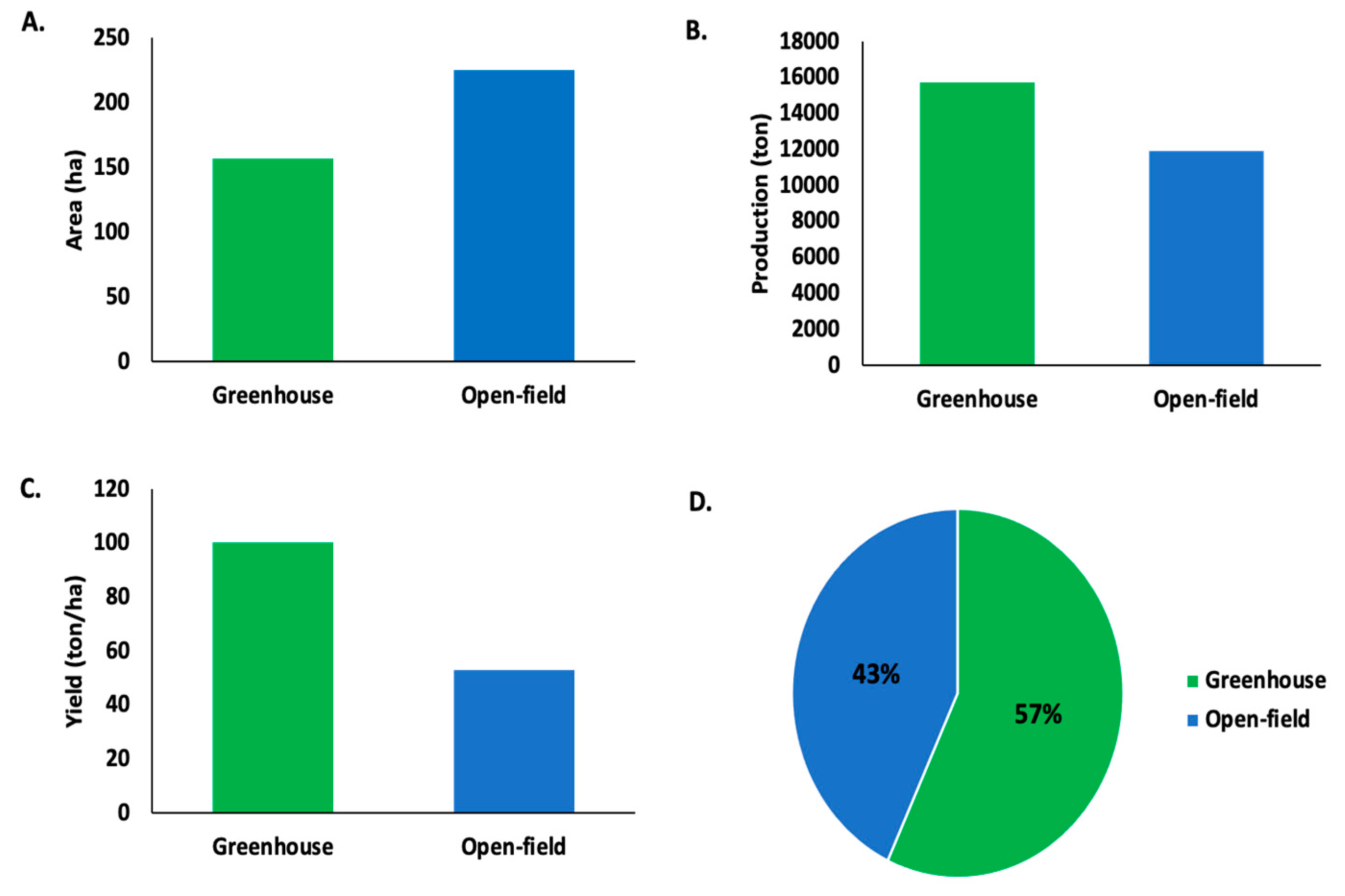

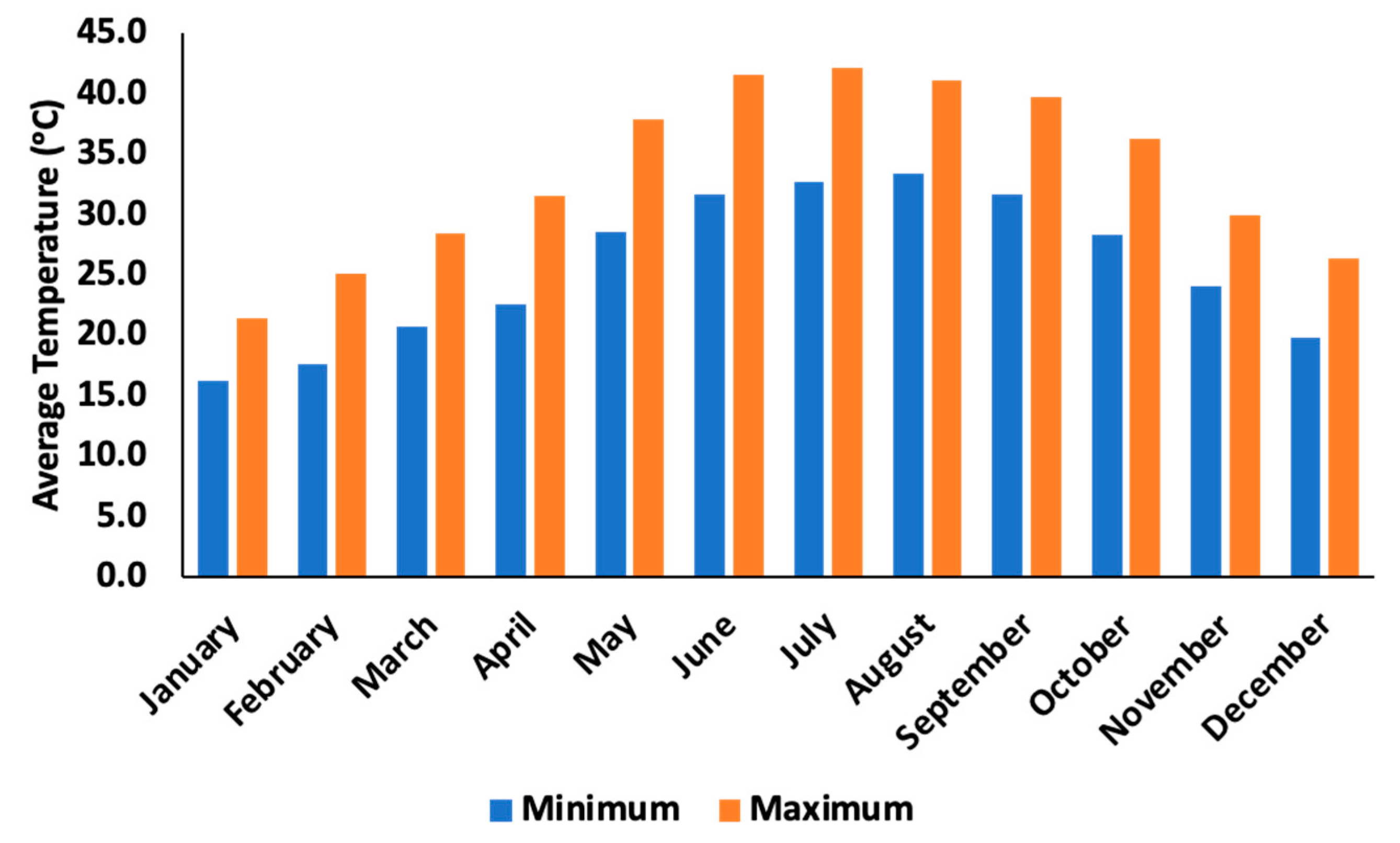

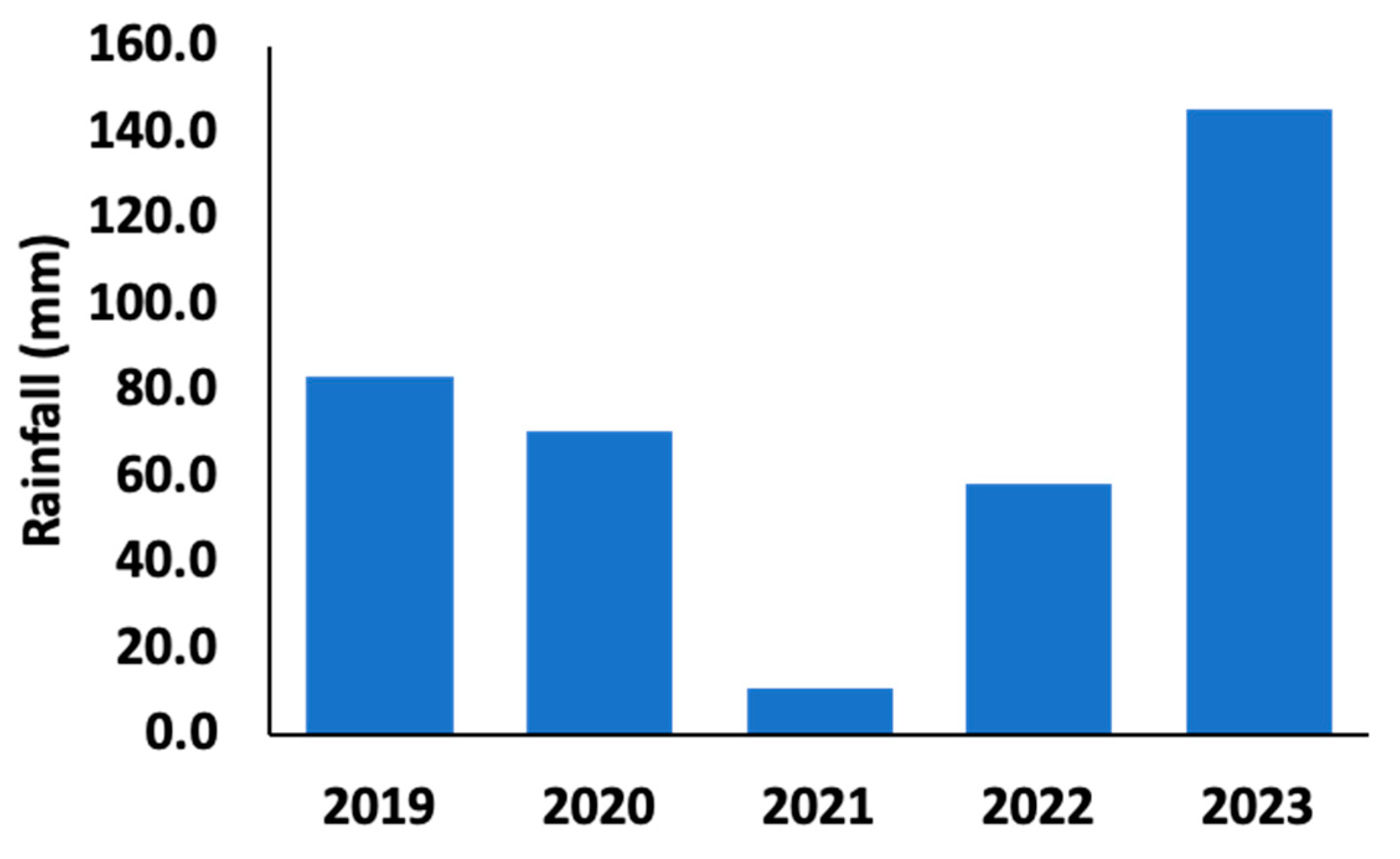

Current Practices

Challenges

Opportunities

Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Authors’ contributions Data curation

Competing interests

References

- Tanksley, S.D. The genetic, developmental, and molecular bases of fruit size and shape variation in tomato. The Plant Cell 2004, 16, S181–S189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qatar National Food Security Strategy 2018-2023. 2020. https://www.mme.gov.qa/pdocs/cview?siteID=2&docID=19772&year=2020.

- Qatar Imports Tomatoes, fresh or chilled | 2023. 2024. https://trendeconomy.com/data/h2/Qatar/0702#:~:text=Where%20does%20Qatar%20import%20Tomatoes,17%25%20(4.2%20million%20US%24).

- Tan, T.; Al-Khalaqi, A.; Al-Khulaifi, N. Qatar national vision 2030. Sustainable development: An appraisal from the Gulf Region 2014, 19, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Secretariat For Development Planning: Qatar National Vision 2030. 2008. https://www.npc.qa/en/QNV/Documents/QNV2030_English_v2.pdf.

- Hassen, T.B.; El-Bilali, H. In X International Agriculture Symposium, Agrosym 2019, Jahorina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 3-6 October 2019. Proceedings. 1337-1343.

- Amhamed, A.; et al. Food security strategy to enhance food self-sufficiency and overcome international food supply chain crisis: the state of Qatar as a case study. Green Technology, Resilience, and Sustainability 2023, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dobashi, H.; Wright, S. Developing the Desert: How Qatar Achieved Dairy Self-Sufficiency Through Baladna. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.U.; Begum, F.; Ahmed, A.; Talukder, N. A blessing inside a calamity: Baladna food industries in Qatar. International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development 2020, 19, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrouz, J.P.; Katramiz, E.; Ghali, K.; Ouahrani, D.; Ghaddar, N. Comparative analysis of sustainable desiccant–Evaporative based ventilation systems for a typical Qatari poultry house. Energy Conversion and Management 2021, 245, 114556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloui, S.; Zghibi, A.; Mazzoni, A.; Elomri, A.; Triki, C. Groundwater resources in Qatar: A comprehensive review and informative recommendations for research, governance, and management in support of sustainability. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies 2023, 50, 101564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddek, S.; et al. How greenhouse horticulture in arid regions can contribute to climate-resilient and sustainable food security. Global Food Security 2023, 38, 100701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, W.; et al. Benchmarking techno-economic performance of greenhouses with different technology levels in a hot humid climate. Biosystems Engineering 2024, 244, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choab, N.; et al. Effect of greenhouse design parameters on the heating and cooling requirement of greenhouses in moroccan climatic conditions. IEEE Access 2020, 9, 2986–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanciu, C.; Stanciu, D.; Dobrovicescu, A. Effect of greenhouse orientation with respect to EW axis on its required heating and cooling loads. Energy Procedia 2016, 85, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanghellini, C.; Dai, J.; Kempkes, F. Effect of near-infrared-radiation reflective screen materials on ventilation requirement, crop transpiration and water use efficiency of a greenhouse rose crop. Biosystems Engineering 2011, 110, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsafaras, I.; et al. Intelligent greenhouse design decreases water use for evaporative cooling in arid regions. Agricultural Water Management 2021, 250, 106807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, A.; Farid, M.; Subiantoro, A.; Norris, S. Sustainable cooling strategies to minimize water consumption in a greenhouse in a hot arid region. Agricultural Water Management 2022, 274, 107960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, S.; et al. A review on opportunities for implementation of solar energy technologies in agricultural greenhouses. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 285, 124807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirich, A.; Choukr-Allah, R. In Water resources in arid areas: The way forward. 481-499 (Springer).

- Soussi, M.; Chaibi, M.T.; Buchholz, M.; Saghrouni, Z. Comprehensive Review on Climate Control and Cooling Systems in Greenhouses under Hot and Arid Conditions. Agronomy 2022, 12, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, A.; Ghosh, S. A review of ventilation and cooling technologies in agricultural greenhouse application. Iranica Journal of Energy & Environment 2011, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Maslak, K.; Nimmermark, S. Thermal energy use for dehumidification of a tomato greenhouse by natural ventilation and a system with an air-to-air heat exchanger. Agricultural and Food Science 2017, 26, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, V.; Sharma, S. Survey of cooling technologies for worldwide agricultural greenhouse applications. Solar Energy 2007, 81, 1447–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawalbeh, M.; Aljaghoub, H.; Alami, A.H.; Olabi, A.G. Selection criteria of cooling technologies for sustainable greenhouses: A comprehensive review. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress 2023, 38, 101666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baille, A.; Kittas, C.; Katsoulas, N. Influence of whitening on greenhouse microclimate and crop energy partitioning. Agricultural and forest meteorology 2001, 107, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, R.; Kouravand, S.; Hassan-Beygi, R. Analysis of wind turbine usage in greenhouses: wind resource assessment, distributed generation of electricity and environmental protection. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects 2023, 45, 7846–7866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P. A solar cooling system for greenhouse food production in hot climates. Solar energy 2005, 79, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanien, R.H.E.; Li, M.; Dong Lin, W. Advanced applications of solar energy in agricultural greenhouses. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 54, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, M.S.; et al. A critical review on efficient thermal environment controls in indoor vertical farming. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 425, 138923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum: How vertical farming can save water and support food security. 2023. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/06/how-vertical-farming-can-save-water-and-support-food-security/.

- Oh, S.; Lu, C. Vertical farming - smart urban agriculture for enhancing resilience and sustainability in food security. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2022, 98, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, A.; Valipour, M.S.; Rashidi, S. Performance Enhancement Techniques in Humidification–Dehumidification Desalination Systems: A Detailed Review. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2024, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ismaili, A.M.; Jayasuriya, H. Seawater greenhouse in Oman: A sustainable technique for freshwater conservation and production. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 54, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemai, N.; Soussi, M.; Chaibi, M.T. Opportunities for Implementing Closed Greenhouse Systems in Arid Climate Conditions. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; et al. Next-generation water-saving strategies for greenhouses using a nexus approach with modern technologies. Nature Communications 2025, 16, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, F.; Al-Ansari, T. Design and analysis of a renewable energy driven greenhouse integrated with a solar still for arid climates. Energy Conversion and Management 2022, 258, 115512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.A.; Hossain, A.K. Development of an integrated reverse osmosis-greenhouse system driven by solar photovoltaic generators. Desalination and Water Treatment 2010, 22, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.D.; González, R.A.; Sánchez-Molina, J.A.; Berenguel, M.; Rodríguez, F. Reverse osmosis desalination for greenhouse irrigation: Experimental characterization and economic evaluation based on energy hubs. Desalination 2024, 574, 117281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahdab, Y.D.; Schücking, G.; Rehman, D.; Lienhard, J.H. Cost effectiveness of conventionally and solar powered monovalent selective electrodialysis for seawater desalination in greenhouses. Applied Energy 2021, 301, 117425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahdab, Y.D.; Rehman, D.; Schücking, G.; Barbosa, M.; Lienhard, J.H.V. Treating Irrigation Water Using High-Performance Membranes for Monovalent Selective Electrodialysis. ACS ES&T Water 2021, 1, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorzhiev, S.S.; Bazarova, E.G.; Pimenov, S.V.; Dorzhiev, S.S. Application of renewable energy sources for water extraction from atmospheric air. Energy Reports 2021, 7, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Danook, S.H.; AL-bonsrulah, H.A.Z.; Veeman, D.; Wang, F. A Recent and Systematic Review on Water Extraction from the Atmosphere for Arid Zones. Energies 2022, 15, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, A.; et al. Recent Development of Atmospheric Water Harvesting Materials: A Review. ACS Materials Au 2022, 2, 576–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPotin, A.; Kim, H.; Rao, S.R.; Wang, E.N. Adsorption-based atmospheric water harvesting: impact of material and component properties on system-level performance. Accounts of chemical research 2019, 52, 1588–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; et al. A roadmap to sorption-based atmospheric water harvesting: from molecular sorption mechanism to sorbent design and system optimization. Environmental Science & Technology 2021, 55, 6542–6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; et al. A solar-driven atmospheric water extractor for off-grid freshwater generation and irrigation. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schor, N.; et al. Robotic disease detection in greenhouses: combined detection of powdery mildew and tomato spotted wilt virus. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2016, 1, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañadas, J.; Sánchez-Molina, J.A.; Rodríguez, F.; del Águila, I.M. Improving automatic climate control with decision support techniques to minimize disease effects in greenhouse tomatoes. Information Processing in Agriculture 2017, 4, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šalagovič, J.; et al. Microclimate monitoring in commercial tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) greenhouse production and its effect on plant growth, yield and fruit quality. Frontiers in Horticulture 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahonen, T.; Virrankoski, R.; Elmusrati, M. In 2008 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Mechtronic and Embedded Systems and Applications. 403-408 (IEEE).

- Lavanaya, M.; Parameswari, R. In 2018 Second International Conference on Green Computing and Internet of Things (ICGCIoT). 547-552 (IEEE).

- García-Ruiz, R.A.; López-Martínez, J.; Blanco-Claraco, J.L.; Pérez-Alonso, J.; Callejón-Ferre, Á.J. Ultraviolet Index (UVI) inside an Almería-Type Greenhouse (Southeastern Spain). Agronomy 2020, 10, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; et al. Mid-infrared absorption-spectroscopy-based carbon dioxide sensor network in greenhouse agriculture: development and deployment. Applied Optics 2016, 55, 7029–7036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, S.M.-e.; et al. IoT-based sensor data fusion for determining optimality degrees of microclimate parameters in commercial greenhouse production of tomato. Sensors 2020, 20, 6474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siregar, B.; Fadli, F.; Andayani, U.; Harahap, L.; Fahmi, F. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 012087 (IOP Publishing).

- Seyar, M.H.; Ahamed, T. Development of an IoT-Based Precision Irrigation System for Tomato Production from Indoor Seedling Germination to Outdoor Field Production. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; et al. Enhancement for Greenhouse Sustainability Using Tomato Disease Image Classification System Based on Intelligent Complex Controller. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimberg, R.; Teitel, M.; Ozer, S.; Levi, A.; Levy, A. Estimation of Greenhouse Tomato Foliage Temperature Using DNN and ML Models. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.-H.; Lee, T.S.; Kim, K.; Park, S.H. A Deep Learning Model to Predict Evapotranspiration and Relative Humidity for Moisture Control in Tomato Greenhouses. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemming, S.; Zwart, F.d.; Elings, A.; Petropoulou, A.; Righini, I. Cherry Tomato Production in Intelligent Greenhouses—Sensors and AI for Control of Climate, Irrigation, Crop Yield, and Quality. Sensors 2020, 20, 6430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-H.; et al. A study on greenhouse automatic control system based on wireless sensor network. Wireless Personal Communications 2011, 56, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyezza, H.; Bouhedda, M.; Kara, R.; Rebouh, S. Smart platform based on IoT and WSN for monitoring and control of a greenhouse in the context of precision agriculture. Internet of Things 2023, 23, 100830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; et al. Accumulation of microplastics in greenhouse soil after long-term plastic film mulching in Beijing, China. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 828, 154544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonsong, P.; Ussawarujikulchai, A.; Prapagdee, B.; Pansak, W. Contamination of microplastics in greenhouse soil subjected to plastic mulching. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2025, 37, 103991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, H.U.; et al. In Microplastics in Agriculture and Food Science (eds Pasquale Avino, Cristina Di Fiore, & Stefano Farris) 147-156 (Academic Press, 2025).

- Cha, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Chia, R.W. Microplastics contamination and characteristics of agricultural groundwater in Haean Basin of Korea. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 864, 161027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorasan, C.; Taladriz-Blanco, P.; Rodriguez-Lorenzo, L.; Espiña, B.; Rosal, R. New versus naturally aged greenhouse cover films: Degradation and micro-nanoplastics characterization under sunlight exposure. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 918, 170662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.; et al. Assessment of Microplastics Pollution on Soil Health and Eco-toxicological Risk in Horticulture. Soil Systems 2023, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeck, C.; Davies, G.; Krause, S.; Schneidewind, U. Microplastics and nanoplastics in agriculture—A potential source of soil and groundwater contamination? Grundwasser 2023, 28, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, L.M.; et al. Field response of N2O emissions, microbial communities, soil biochemical processes and winter barley growth to the addition of conventional and biodegradable microplastics. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2022, 336, 108023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; et al. Stimulated soil CO2 and CH4 emissions by microplastics: A hierarchical perspective. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2024, 194, 109425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeley, M.E.; Song, B.; Passie, R.; Hale, R.C. Microplastics affect sedimentary microbial communities and nitrogen cycling. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viaroli, S.; Lancia, M.; Re, V. Microplastics contamination of groundwater: Current evidence and future perspectives. A review. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 824, 153851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; et al. Microplastics in soils: a review of possible sources, analytical methods and ecological impacts. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 2020, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, J. Characterization of microplastics and the association of heavy metals with microplastics in suburban soil of central China. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 694, 133798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathan, S.I.; et al. Soil Pollution from Micro- and Nanoplastic Debris: A Hidden and Unknown Biohazard. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate, C.; et al. Soil Bioplastic Mulches for Agroecosystem Sustainability: A Comprehensive Review. Agriculture 2023, 13, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maplecroft. Global Risk Portfolio. 2009. https://www.maplecroft.com/global-risk-data/.

- AeroFarms to Establish New Commercial Indoor Vertical Farm in Qatar Free Zones. 2022. https://qfz.gov.qa/aerofarms-joins-qfz/.

- Ajjur, S.B.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Towards sustainable energy, water and food security in Qatar under climate change and anthropogenic stresses. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Planning Council: Qatar Atlas. 2024. https://gis.psa.gov.qa/QatarAtlas/index.

- National Planning Council: Agriculture. 2024. https://www.npc.qa/en/statistics/Statistical%20Releases/Economic/Agriculture/1_Agricuitural_2022_AE.pdf.

- FAOSTAT 2023. 2023. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL.

- National Planning Council: Water Statistics. 2022. https://www.npc.qa/en/statistics/Statistical%20Releases/Environmental/Water/Water_Statistics_2021_EN.pdf.

- Hassad Food: Mahaseel For Marketing & Agriculture Services Company. 2018. https://www.hassad.com/marketing-local-produce/.

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorologische Zeitschrift 2006, 15, 2559–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karanisa, T.; et al. Agricultural production in Qatar’s hot arid climate. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Planning Council: Physical and Climate Features. 2024. https://www.npc.qa/en/statistics/Statistical%20Releases/Environmental/Physical%20and%20Climate%20Features/Physical_Climate_Features_2023_AE.pdf.

- Hussein, H.; Lambert, L.A. A rentier state under blockade: Qatar’s water-energy-food predicament from energy abundance and food insecurity to a silent water crisis. Water 2020, 12, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shomar, B.; Sankaran, R. Groundwater Contamination in Arid Coastal Areas: Qatar as a Case Study. Groundwater 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manawi, Y.; Fard, A.K.; Hussien, M.A.; Benamor, A.; Kochkodan, V. Evaluation of the current state and perspective of wastewater treatment and reuse in Qatar. Desalination Water Treat 2017, 71, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Planning Council: Environmental Statistics. 2024. https://www.npc.qa/en/statistics/Statistical%20Releases/Environmental/Environmental%20Statistics/Environment_11_2023.pdf.

- Patel, S.; Karanisa, T.; Khalek, M.A. Backyard Urban Agriculture in Qatar: Challenges & Recommendations. Environmental Network Journal 2021. http://hdl.handle.net/10576/30946.

- Shomar, B.; Sankaran, R.; Solano, J.R. Mapping of trace elements in topsoil of arid areas and assessment of ecological and human health risks in Qatar. Environmental Research 2023, 225, 115456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwish, M.A.; Mohtar, R. Qatar water challenges. Desalination and Water Treatment 2013, 51, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. AQUASTAT Country Profile – Qatar. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome, Italy. 2008. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/6d1c5804-a9b1-497c-99b7-10ad04a1bce1/content.

- Panno, S.; et al. A review of the most common and economically important diseases that undermine the cultivation of tomato crop in the mediterranean basin. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazen, M.; et al. Evaluation of Tomato Cultivars against Early Leaf Blight (Alternaria solani) in net greenhouse Qatar. Journal of Advances in Agriculture 2023, 14, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-marri, M.; et al. Impact of irrigation method on root rot and wilt diseases in tomato under net greenhouse in the state of qatar. Journal of Advances in Agriculture 2018, 8, 1452–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desneux, N.; et al. Integrated pest management of Tuta absoluta: practical implementations across different world regions. Journal of Pest Science 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.H.; et al. Vector Transmission of Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Thailand Virus by the Whitefly Bemisia tabaci: Circulative or Propagative? Insects 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arah, I.K.; Amaglo, H.; Kumah, E.K.; Ofori, H. Preharvest and postharvest factors affecting the quality and shelf life of harvested tomatoes: a mini review. International Journal of Agronomy 2015, 2015, 478041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Planning Council: Labor Force. 2024. https://www.npc.qa/en/statistics/Statistical%20Releases/Social/Labor%20Force/2_Labour_Force_2023_AE.pdf.

- Qatar Reseach, Development and Innovation (QRDI) Council. 2024. https://qrdi.org.qa/en-us/.

- QU’s Center for Advanced Materials (CAM) Leads Groundbreaking Research on Thermal Energy Storage Materials. 2023. https://www.qu.edu.qa/en-us/newsroom/Pages/newsdetails.aspx?newsID=7046.

- Nishad, S.; Krupa, I. Phase change materials for thermal energy storage applications in greenhouses: A review. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2022, 52, 102241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naemi, S.; Al-Otoom, A. Smart sustainable greenhouses utilizing microcontroller and IOT in the GCC countries; energy requirements & economical analyses study for a concept model in the state of Qatar. Results in Engineering 2023, 17, 100889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salt-Based Cooling and Wastewater/Brine Reuse by Photo-Electrodialysis for Hydroponic Greenhouses. 2024. https://innolight.qrdi.org.qa/projects/40150.

- Development of novel and sustainable cooling technologies for self-sufficient greenhouses and buildings. 2020. https://innolight.qrdi.org.qa/projects/32080#Publications.

- VFarms. 2025. https://vfarms.qa/.

- Hydrogel Agriculture to Support Food Security in Qatar. 2020. https://connect.qrdi.org.qa/projects?id=34036&query=MME01-0906-190024%09.

- Climate smart agriculture and indoor farming. 2024. https://www.ksp.go.kr/english/pageView/info-eng/985?listCount=30&page=0&srchText=&pjtCd=pjta&nationCd=QA.

- Concept Design and Validation of an Energy-efficient Clear Solar Glass Greenhouse for Higher Food Production in Arid Climate of Qatar. 2024. https://connect.qrdi.org.qa/projects?id=40361&query=MME04-0607-230060.

- Berg, G. Plant–microbe interactions promoting plant growth and health: perspectives for controlled use of microorganisms in agriculture. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2009, 84, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-C.; Glick, B.R.; Bashan, Y.; Ryu, C.-M. Enhancement of plant drought tolerance by microbes. Plant Responses to Drought Stress 2012, 383–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, S.; Arora, N. Soybean production under flooding stress and its mitigation using plant growth-promoting microbes. Environmental Stresses in Soybean Production 2016, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dias, M.C.; Freitas, H. Drought and salinity stress responses and microbe-induced tolerance in plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11, 591911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehra, A.; Raytekar, N.A.; Meena, M.; Swapnil, P. Efficiency of microbial bio-agents as elicitors in plant defense mechanism under biotic stress: A review. Current Research in Microbial Sciences 2021, 2, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Sarma, B.K.; Upadhyay, R.S.; Singh, H.B. Compatible rhizosphere microbes mediated alleviation of biotic stress in chickpea through enhanced antioxidant and phenylpropanoid activities. Microbiological Research 2013, 168, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BiBi, A.; Bibi, S.; Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Abu-Dieyeh, M.H. Isolation and evaluation of Qatari soil rhizobacteria for antagonistic potential against phytopathogens and growth promotion in tomato plants. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 22050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.E.; et al. Tomato leaf diseases detection using deep learning technique. Technology in Agriculture 2021, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Ahmed, T.; Abu-Dieyeh, M.; Al-Ghouti, M.A. Investigating the quality and efficiency of biosolid produced in qatar as a fertilizer in tomato production. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rumaihi, A.; et al. A techno-economic assessment of biochar production from date pits in the MENA region. Computer Aided Chemical Engineering 2022, 51, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhalifa, S.; et al. Simulation of food waste pyrolysis for the production of biochar: A Qatar case study. Computer Aided Chemical Engineering 2019, 46, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; et al. Biochar from vegetable wastes: agro-environmental characterization. Biochar 2020, 2, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, P.; Alherbawi, M.; Pradhan, S.; Al-Ansari, T.; Mckay, G. Estimation of Poultry Litter and Its Biochar Production Potential Through Pyrolysis in Qatar. Chemical Engineering Transactions 2024, 109, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, P.; et al. Pyrolysis characteristics, kinetic, and thermodynamic analysis of camel dung, date stone, and their blend using thermogravimetric analysis. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; et al. Effects of Biochar Application on Tomato Yield and Fruit Quality: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luigi, M.; et al. Effects of biochar on the growth and development of tomato seedlings and on the response of tomato plants to the infection of systemic viral agents. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 862075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Senge, M.; Dai, Y. Effects of salinity stress on growth, yield, fruit quality and water use efficiency of tomato under hydroponics system. Reviews in Agricultural Science 2016, 4, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajyan, T.; et al. In XXX International Horticultural Congress IHC2018: International Symposium on Water and Nutrient Relations and Management of 1253. 33-40.

- Masmoudi, F.; et al. Novel Thermo-Halotolerant Bacteria Bacillus cabrialesii Native to Qatar Desert: Enhancing Seedlings’ Growth, Halotolerance, and Antifungal Defense in Tomato. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasseen, B.T.; Al-Thani, R.F. Endophytes and halophytes to remediate industrial wastewater and saline soils: Perspectives from Qatar. Plants 2022, 11, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elazazi, E.; et al. Genotypic Selection Using QTL for Better Productivity under High Temperature Stress in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Horticulturae 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, P.K.; Guo, B.; Leskovar, D.I. Assessing Tomato Genotypes for Organic Hydroponic Production in Stressful Environmental Conditions. HortScience 2024, 59, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, P.K.; Guo, B.; Leskovar, D.I. Optimizing hydroponic management practices for organically grown greenhouse tomato under abiotic stress conditions. HortScience 2023, 58, 1129–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QAFCO-Agrico-YARA trial station opening. 2019. https://www.qafco.qa/content/qafco-agrico-yara-trial-station-opening.

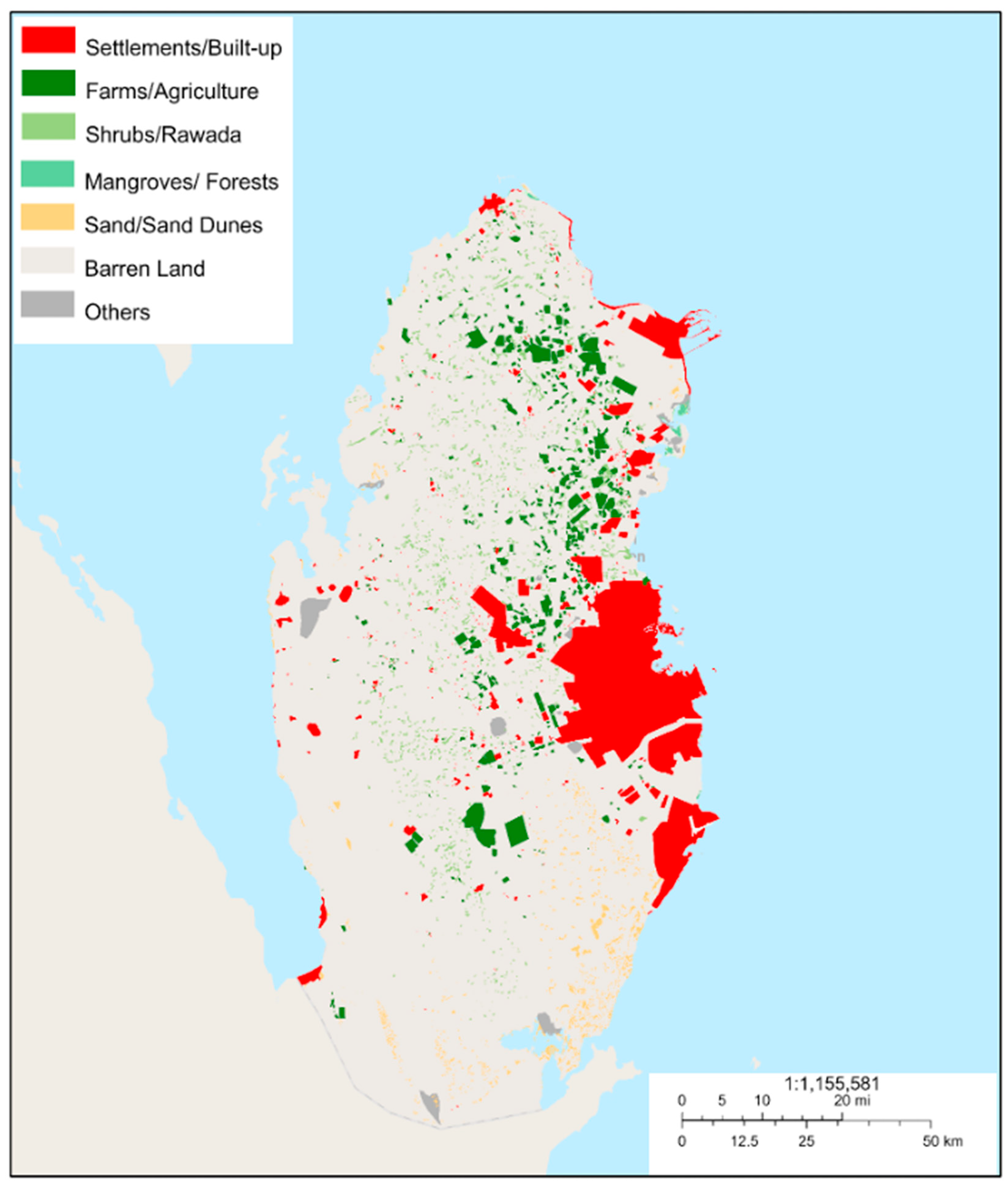

| Class | Area (hectars) |

|---|---|

| Settlements/Built-up | 118194.51 |

| Farms/Agriculture | 42778.82 |

| Shrubs/Rawada | 23326.21 |

| Mangroves/Forests | 968.37 |

| Sand/Sand Dunes | 13407.15 |

| Barren Land | 952851.86 |

| Others (Water Bodies/Exposed Land) | 9410.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).