1. Introduction

The engineering profession in South Africa is integral to the country’s socio-economic development, catalysing technological innovation, infrastructure expansion, and industrial competitiveness. However, the long-term sustainability of the engineering workforce is at risk due to high attrition rates within the engineering skills pipeline. A substantial proportion of students enrolling in engineering programmes do not complete their qualifications, leading to a persistent shortage of qualified engineering professionals. This challenge extends beyond academia, affecting industries that depend on skilled engineers to drive innovation, economic growth, and sustainable development.

As the regulatory authority overseeing the engineering profession, the Engineering Council of South Africa (ECSA) plays a pivotal role in fostering a sustainable pipeline of qualified engineers. Academic institutions, meanwhile, act as the fundamental training hubs that shape future engineers through rigorous curricula and practical exposure. Given the interdependent nature of these roles, a structured and sustained collaboration between ECSA and academic institutions is imperative to tackle the multifaceted challenges contributing to student attrition. By jointly identifying key barriers ranging from academic preparedness and financial constraints to institutional support and industry alignment, they can develop targeted interventions to enhance student retention, improve graduation rates, and ultimately ensure a resilient engineering workforce for South Africa’s future development.

This study aims to comprehensively investigate the root causes of student attrition in engineering programmes and develop a robust framework for collaboration between ECSA and academic institutions to address this pressing issue. By integrating insights from existing research, analysing institutional data, and engaging with key stakeholders, the study seeks to identify actionable strategies that enhance student retention and graduation rates. Furthermore, the research will explore innovative approaches such as mentorship programmes, curriculum enhancements, financial support mechanisms, and industry-academic partnerships to foster a more inclusive and sustainable engineering workforce in South Africa.

1.1. Objectives

The objectives of this study are as follows:

To assess the engineering skills pipeline, including student enrollment, progression, and dropout trends.

To identify factors contributing to student attrition, such as academic challenges, financial constraints, and industry misalignment.

To evaluate the impact of industry-academia gaps on student retention.

1.2. Pipeline from School Exit Examinations to Professional Registration

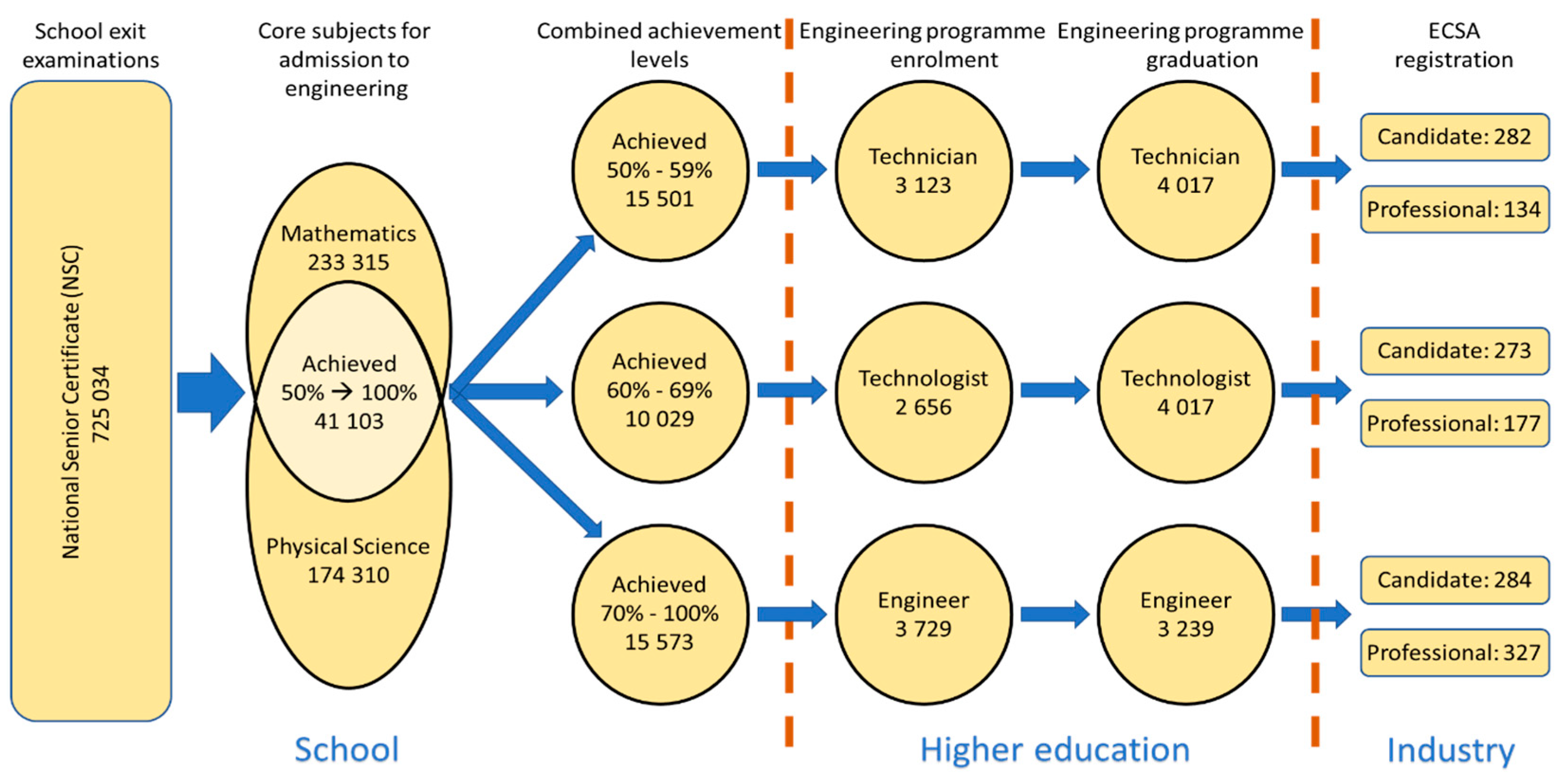

A 2022 ECSA report on the engineering skills pipeline aimed to quantify the progression of potential engineering professionals from school through to professional registration with ECSA. The report provides insights into the challenges and attrition rates at various stages of this pipeline.

Figure 1 presents a high-level overview of student movement through the different pipeline stages in 2020, highlighting key transition points and drop-off rates within the engineering education and professional development process.

A total of 725 034 students wrote their final National Senior Certificate examinations in 2020. Only 20% of the 15 501 students were eligible for entrance to an engineering diploma qualification (having achieved Level 4, or 50%-59%) enrollment. 27% of eligible students enrolled in a technologist qualification, and 24% enrolled in an engineering degree qualification. While these figures suggest a reasonable transition into engineering education, they also reveal a concerning trend up to 75% of eligible students did not pursue an engineering qualification. This indicates that despite meeting the minimum entry requirements, a significant portion of potential engineering students either opt for other fields or face barriers preventing them from enrolling.

Even more concerning is the low conversion rate to professional registration. Of the students eligible to enter engineering programs, only 1.6% ultimately attained professional registration with ECSA in 2020. When considering only those who actually enrolled in engineering programmes, this figure rises to just 6%. These statistics starkly highlight the high attrition rate across the engineering pipeline, underscoring the urgent need for interventions to improve retention, support students through their academic journey, and bridge the gap between graduation and professional registration.

High attrition rates among engineering students are a global concern, with South Africa experiencing particularly alarming statistics. Studies indicate that the average non-completion rate for engineering programs in the country hovers around 50%, a figure comparable to international trends (Bernold, Spurlin, & Anson, 2007). Engineering programmes often demand high levels of mathematical and technical proficiency, which, combined with socio-economic factors, contribute to student dropout rates. The consequences of these high attrition rates are significant, as they exacerbate the already critical shortage of engineering professionals needed for national development and infrastructure projects.

A case study conducted at the Faculty of Engineering at the University of KwaZulu-Natal by Pocock provides insights into these attrition trends (Pocock, 2012). The research revealed a positive trend between 2005 and 2008, with first-year engineering student attrition rates decreasing from over 22% to below 14%. However, in 2009, this trend reversed, with an uptick to over 17%, a shift that was potentially linked to changes in the national high school curriculum. This suggests that foundational education plays a crucial role in students’ ability to succeed in engineering programmes.

1.3. Contributing Factors to High Attrition Rates in Engineering

Further research supports these arguments, indicating that factors such as inadequate high school preparation, financial constraints, lack of academic support, and limited industry exposure contribute to student dropouts in engineering (BusinessTech, 2015). The transition from high school to tertiary education in South Africa has been particularly challenging for students from underprivileged backgrounds, who often struggle with adapting to university-level coursework and the financial burden associated with higher education.

In addition, engineering education in South Africa has historically been criticised for its theoretical emphasis, with limited practical applications in the early years of study. This disconnect between academic learning and industry expectations often results in disengagement among students, further exacerbating dropout rates. The role of professional bodies such as the ECSA in bridging this gap by ensuring industry-relevant curricula and providing mentorship programmes has become increasingly critical in addressing these challenges.

Economic hardships play a significant role in student retention within engineering programs, particularly in South Africa, where financial exclusion remains a major barrier to higher education. Engineering degrees are typically longer and more expensive compared to other disciplines due to the need for specialised equipment, laboratory access, and practical training components. Many students, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds, struggle to afford tuition fees, textbooks, and accommodation, which increases the likelihood of dropping out.

Pocock further found that 49% of students who left the engineering faculty cited financial difficulties as the primary reason for their departure (Pocock, 2012). The financial burden is exacerbated by additional expenses such as transportation, food, and the cost of compulsory practical training, which many students cannot afford without external financial support. While financial aid programmes such as the National Student Financial Aid Scheme provide some relief, they often fall short of covering all associated costs, leaving students vulnerable to attrition.

Moreover, students from low-income households frequently take on part-time jobs to sustain themselves, which can negatively impact their academic performance. Balancing work and a demanding engineering curriculum leads to exhaustion, lower grades, and withdrawal from the programme. Research has shown that financial stress significantly reduces student engagement and increases dropout rates, particularly in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics fields that require continuous focus and extensive study hours (Ahmed, Kloot, & Collier-Reed, 2014).

Another key challenge contributing to high attrition rates among engineering students is the misalignment between academic training and industry requirements. While engineering curricula in South Africa and globally are designed to provide students with technical knowledge and problem-solving abilities, they often fall short in preparing students for the diverse skill sets demanded by the modern workforce. As a result, many students graduate with strong technical expertise but lack the practical, industry-relevant skills needed to thrive in real-world engineering environments.

1.4. The Impact of Limited Practical Exposure on Engineering Student Retention

Employers increasingly seek engineering graduates who possess not only technical expertise but also strong skills in project management, teamwork, leadership, communication, and financial acumen. The ability to manage projects effectively, collaborate within multidisciplinary teams, and understand the financial implications of engineering decisions are critical for success in the field. However, engineering education often emphasises theoretical learning, with limited exposure to real-world applications and industry-standard practices. As a result, graduates may struggle to transition from the classroom to the workplace, leading to feelings of inadequacy, frustration, and, ultimately, dissatisfaction with their chosen career path.

This gap between academic training and industry needs can contribute to higher dropout rates in several ways. First, students may become disillusioned with their education if they perceive it as irrelevant to the challenges they will face in the workforce. Inadequate exposure to practical, industry-related experiences, such as internships or co-op programmes, can create a disconnect between what students learn and what employers expect. Additionally, when students realise they are not equipped with the essential “soft skills” that many employers require, they may lose confidence in their ability to succeed in the engineering profession and opt to leave the program.

Research has highlighted that the lack of industry-relevant skills is a significant contributor to dissatisfaction among engineering graduates, with many employers reporting that new hires often require extensive retraining to meet the demands of the workplace (BusinessTech, 2015). Furthermore, students who feel unprepared for the professional world are less likely to persist in their studies. They may perceive the engineering degree as insufficient for achieving their career goals, particularly if they are unable to see clear pathways from academia to industry.

Addressing high engineering attrition rates requires a multifaceted approach considering academic, financial, and industry-related factors. Strengthening collaboration between universities and professional regulatory bodies like ECSA can help ensure that curricula are aligned with industry needs, incorporate practical learning experiences, and offer robust student support mechanisms. By implementing targeted interventions such as mentorship programs, financial aid initiatives, and curriculum reforms, South Africa can work towards reducing engineering attrition rates and fostering a sustainable engineering workforce that meets the country’s developmental needs.

2. Materials and Methods

The pragmatic paradigm was followed in the current study, which entails the use of different methods (qualitative and quantitative research methods) to explore a phenomenon (Sefotho, 2021). The study employed a sequential explanatory mixed method design which is characterised by collecting quantitative data and analysis before the collection of qualitative data. This design was used to gather complete and holistic insights from ECSA registered candidates and lecturers from academic institutions.

Non-probability sampling, specifically volunteer sampling, was employed for the qualitative and quantitative components of the study. For the quantitative component, 263 registered candidates were sampled while 10 lecturers were sampled for the qualitative component of the study.

The table below presents the demographic information of the participants who took part in the quantitative component of the study. This includes details such as age group, candidacy category and engineering discipline.

| Age group |

| |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

| 25-34 |

140 |

53.2% |

| 35-44 |

84 |

31.9% |

| 45+ |

29 |

11.0% |

| Under 25 |

10 |

3.8% |

| Candidacy category |

| Candidate Certificated Engineer |

8 |

3.0% |

| Candidate Engineer |

111 |

42.2% |

| Candidate Engineering Technician |

46 |

17.5% |

| Candidate Engineering Technologist |

98 |

37.3% |

| Engineering discipline |

| Agricultural |

1 |

0.4% |

| Chemical |

20 |

7.6% |

| Civil |

125 |

47.5% |

| Electrical |

52 |

19.8% |

| Industrial |

9 |

3.4% |

| Mechanical |

52 |

19.8% |

| Mechatronics |

1 |

0.4% |

| Metallurgical |

1 |

0.4% |

| Mining |

2 |

0.8% |

The largest age group of registered engineering candidates was between 25-34 years, comprising 53.2% of the sample (n=140). The next largest group was aged 35-44 (31.9%, n=84), representing mid-career professionals. Registered engineering candidates aged 45 years and above represented 11.0% of the sample (n=29). Very few registered engineering candidates were under 25 (3.8%, n=10). The majority of registered engineering candidates identified as Candidate Engineers (42.2%, n=111), closely followed by Candidate Engineering Technologists (37.3%, n=98). Candidate Engineering Technicians made up 17.5% (n=46) of registered engineering candidates. Only 3.0% of the registered engineering candidates were Candidate Certificated Engineers (n=8). The predominant engineering discipline was Civil Engineering (47.5%, n=125). Electrical and Mechanical Engineering each accounted for 19.8% (n=52). Chemical Engineering accounted for 7.6% (n=20), and smaller fields such as Industrial Engineering (3.4%, n=9), Mining (0.8%, n=2), Agricultural, Mechatronics, and Metallurgical Engineering each represented less than 1%.

Structured and open-ended questionnaires were used to collect data from ECSA candidates and university lecturers to understand their experiences with academic, financial, and institutional challenges that contribute to attrition and their views on the recommendations on effective support mechanisms. Structured questionnaires were disseminated to ECSA registered engineering candidates while open ended questionnaires were distributed to lecturers.

The qualitative data was analysed using thematic analysis. The Kruskal-Wallis H test was employed for quantitative data. This is a non-parametric statistical method and it was used to determine whether there are statistically significant differences between the medians of the engineering candidates. It was chosen over parametric alternatives due to the nature of the data, which did not meet the assumptions of normality or homogeneity of variance required for parametric testing. Following a significant Kruskal-Wallis result, post-hoc analysis was conducted using mean rank comparisons to identify where differences existed among the groups. The mean ranks provided insight into the direction and relative magnitude of differences between groups.

A reliability test was run on SPSS to assess the reliability of the questionnaire. The KMO value of 0.765 indicated the items in the questionnaire were sufficiently correlated. The significant Bartlett’s Test (p < .001) confirms adequate inter-item correlation. For the qualitative component, data quality was ensured through trustworthiness including credibility, confirmability, transferability, and dependability.

The study was guided by the following ethical considerations: voluntary participation, informed consent, avoidance of harm, confidentiality, and anonymity.

3. Results

3.1. Presentation of Quantitative Findings

This section presents the findings of the quantitative component of the study. The results are based on responses collected through structured questionnaire, and statistical analyses were conducted to examine patterns and differences among groups.

3.1.1. Factors Contribution Attrition

Various factors were identified as contributing to student attrition in engineering programmes. These factors were assessed through Likert-scale survey items and analysed to identify potential group differences. The key categories include academic, financial, and institutional factors contributing to attrition.

This subsection presents the findings related to engineering candidates’ perceptions of academic readiness, learning barriers, and the alignment between students’ abilities and programme expectations.

| Test Statisticsa,b |

| |

The academic workload in my engineering program was manageable. |

My lecturers/instructors provided sufficient academic support. |

I received effective mentorship from academic staff. |

Course content was clearly relevant to practical engineering applications. |

| Kruskal-Wallis H |

21.006 |

1.238 |

6.413 |

5.694 |

| df |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| Asymp. Sig. |

<.001 |

.744 |

.093 |

.127 |

| a. Kruskal Wallis Test |

| b. Grouping Variable: Candidacy category |

The Kruskal-Wallis test indicated a statistically significant difference in participants' perceptions of academic workload across candidacy categories (H = 21.006, p < .001). Post-hoc analysis of mean ranks will be used to further explore the group-level differences. However, no statistically significant differences were found for items related to academic support (p = .744), mentorship (p = .093), or course content relevance (p = .127), and thus, mean ranks for these items will not be explored as this implies similar perceptions across all candidate groups.

| Mean ranks |

| |

Candidacy category |

N |

Mean Rank |

| The academic workload in my engineering program was manageable. |

Candidate Engineer |

111 |

110.26 |

| Candidate Technologist |

98 |

149.92 |

| Candidate Technician |

46 |

145.70 |

| Candidate Certificated Engineer |

8 |

135.31 |

| Total |

263 |

|

The mean rank results suggest that Candidate Engineers found the academic workload significantly more demanding than the other groups. In contrast, Candidate Technologists reported the highest perceived manageability, with a mean rank of 149.92, followed closely by Candidate Technicians (Mean Rank = 145.70) and Candidate Certificated Engineers (Mean Rank = 135.31). Candidate Engineers reported the lowest perceived manageability, with a mean rank of 110.26, indicating that this group experienced greater challenges in coping with the academic workload compared to their peers.

The Kruskal-Wallis test was further used to assess whether perceptions of financial support varied significantly across different candidacy categories.

| Test Statisticsa,b |

| |

I had sufficient financial resources to support my academic progress. |

Access to scholarships/bursaries was adequate during my studies. |

Financial support from my family or guardians was consistent throughout my studies. |

My overall academic performance improved due to adequate financial support. |

| Kruskal-Wallis H |

3.598 |

2.350 |

2.258 |

7.167 |

| df |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| Asymp. Sig. |

.308 |

.503 |

.521 |

.067 |

| a. Kruskal Wallis Test |

| b. Grouping Variable: Candidacy category |

The Kruskal-Wallis test revealed no statistically significant differences for financial-related items, including perceptions of having sufficient financial resources to support academic progress (p = .308), access to scholarships or bursaries (p = .503), consistency of financial support from family or guardians (p = .521), and the belief that financial support improved academic performance (p = .067).

| Test Statisticsa,b |

| |

My institution provided adequate resources (laboratories, software, library) to support my studies. |

Support services provided by my institution (counselling, career services, mentoring) enhanced my academic experience |

Institutional staff were responsive and helpful when addressing student queries or issues. |

| Kruskal-Wallis H |

25.102 |

2.722 |

2.633 |

| df |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| Asymp. Sig. |

<.001 |

.437 |

.452 |

| a. Kruskal Wallis Test |

| b. Grouping Variable: Candidacy category |

The findings indicated significant difference in perceptions of adequacy of institutional resources across candidacy categories (H = 25.102, p < .001). This suggests that perceptions regarding laboratory, software, and library resources vary considerably among Candidate Engineers, Technologists, Technicians, and Certificated Engineers. No statistically significant difference was found (H = 2.722, p = .437) on institutional support services. Similarly, perceptions about institutional staff responsiveness showed no statistically significant differences across candidate categories (H = 2.633, p = .452). This finding implies uniform experiences or concerns regarding institutional responsiveness.

| Mean Ranks |

| |

Candidacy category |

N |

Mean Rank |

| My institution provided adequate resources (laboratories, software, library) to support my studies. |

Candidate Engineer |

111 |

157.00 |

| Candidate Technologist |

98 |

113.36 |

| Candidate Technician |

46 |

115.53 |

| Candidate Certificated Engineer |

8 |

108.19 |

| Total |

263 |

|

Candidate Engineers reported the highest levels of perceived resource adequacy, with a mean rank of 157.00, suggesting they were the most satisfied with the support provided by their institutions. In contrast, Candidate Certificated Engineers reported the lowest perceived adequacy (Mean Rank = 108.19), followed by Candidate Technologists (113.36) and Candidate Technicians (115.53). These results suggest that Candidate Engineers had a more favourable view of the institutional support provided, compared to other candidacy groups.

3.1.2. Collaboration Between ECSA and Academic Institutions

Participants’ views were explored regarding the importance of collaboration between ECSA and academic institutions.

| Test Statisticsa,b |

| |

Collaboration between ECSA and academic institutions is crucial for addressing engineering attrition. |

Joint initiatives by ECSA and academic institutions can effectively address student challenges. |

Increased financial support/scholarships for engineering students would reduce attrition. |

Enhanced mentorship and academic advising programs would reduce attrition. |

More practical, industry-linked learning experiences would reduce attrition. |

Improved institutional resources (e.g., labs, software access) would reduce attrition. |

Regular workshops on coping mechanisms and stress management from academic institutions would reduce attrition. |

| Kruskal-Wallis H |

13.934 |

9.627 |

3.296 |

12.100 |

8.536 |

22.479 |

11.767 |

| df |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| Asymp. Sig. |

.003 |

.022 |

.348 |

.007 |

.036 |

<.001 |

.008 |

| a. Kruskal Wallis Test |

| b. Grouping Variable: Candidacy category |

The table indicates that participants differed in their views on the importance of collaboration between ECSA and academic institutions (H = 13.934, p = .003), the effectiveness of joint initiatives between these entities (H = 9.627, p = .022), and the role of enhanced mentorship and academic advising programmes in reducing attrition (H = 12.100, p = .007). Significant differences were also observed for perceptions regarding the need for more practical, industry-linked learning experiences (H = 8.536, p = .036), improved institutional resources such as laboratories and software (H = 22.479, p < .001), and the potential value of regular workshops on stress management and coping mechanisms (H = 11.767, p = .008). However, no statistically significant difference was found in perceptions related to increased financial support or scholarships as a means to reduce attrition (H = 3.296, p = .348). The table below provides the mean ranks for statistically different items.

| Mean ranks |

| |

Candidacy category |

(n) |

Mean Rank |

| Collaboration between ECSA and academic institutions is crucial for addressing engineering attrition. |

Candidate Engineer |

104 |

119.80 |

| Candidate Technologist |

93 |

138.72 |

| Candidate Technician |

41 |

109.18 |

| Candidate Certificated Engineer |

8 |

68.06 |

| Total |

246 |

|

| Joint initiatives by ECSA and academic institutions can effectively address student challenges. |

Candidate Engineer |

104 |

115.79 |

| Candidate Technologist |

93 |

137.81 |

| Candidate Technician |

41 |

119.00 |

| Candidate Certificated Engineer |

8 |

80.38 |

| Total |

246 |

|

| Enhanced mentorship and academic advising programs would reduce attrition. |

Candidate Engineer |

104 |

117.27 |

| Candidate Technologist |

93 |

137.94 |

| Candidate Technician |

41 |

117.48 |

| Candidate Certificated Engineer |

8 |

67.44 |

| Total |

246 |

|

| More practical, industry-linked learning experiences would reduce attrition. |

Candidate Engineer |

104 |

117.56 |

| Candidate Technologist |

93 |

136.33 |

| Candidate Technician |

41 |

117.62 |

| Candidate Certificated Engineer |

8 |

81.75 |

| Total |

246 |

|

| Improved institutional resources (e.g., labs, software access) would reduce attrition. |

Candidate Engineer |

104 |

104.18 |

| Candidate Technologist |

93 |

145.98 |

| Candidate Technician |

41 |

128.51 |

| Candidate Certificated Engineer |

8 |

87.56 |

| Total |

246 |

|

| Regular workshops on coping mechanisms and stress management from academic institutions would reduce attrition. |

Candidate Engineer |

104 |

112.37 |

| Candidate Technologist |

93 |

138.63 |

| Candidate Technician |

41 |

126.44 |

| Candidate Certificated Engineer |

8 |

77.25 |

| Total |

246 |

|

For the item on collaboration between ECSA and academic institutions as a strategy to address engineering attrition, Candidate Technologists reported the highest agreement (Mean Rank = 138.72), followed by Candidate Engineers (119.80) and Candidate Technicians (109.18), while Candidate Certificated Engineers reported the lowest agreement (68.06). A similar trend was observed for perceptions of joint initiatives by ECSA and academic institutions to address student challenges. Here too, Candidate Technologists reported the highest support (137.81), followed by Candidate Technicians (119.00), Candidate Engineers (115.79), and again, Candidate Certificated Engineers reported the lowest support (80.38).

Regarding the statement that enhanced mentorship and academic advising programmes would reduce attrition, Candidate Technologists held the strongest view (Mean Rank = 137.94), followed closely by Candidate Technicians (117.48) and Candidate Engineers (117.27). Candidate Certificated Engineers, however, again showed the least agreement (67.44). Perceptions on the value of more practical, industry-linked learning experiences followed a similar pattern, with Candidate Technologists showing the highest level of support (136.33), while Candidate Certificated Engineers reported the lowest (81.75). Mean ranks for Candidate Engineers and Candidate Technicians were similar, at 117.56 and 117.62, respectively. In terms of improving institutional resources (e.g., labs, software), Candidate Technologists reported the highest level of perceived impact (Mean Rank = 145.98), followed by Candidate Technicians (128.51), Candidate Engineers (104.18), and Candidate Certificated Engineers (87.56), indicating a strong disparity in perceived resource adequacy and its potential to reduce attrition. Finally, regarding the perceived value of regular workshops on coping mechanisms and stress management, Candidate Technologists once again expressed the strongest agreement (138.63), followed by Candidate Technicians (126.44), Candidate Engineers (112.37), and Candidate Certificated Engineers (77.25).

The findings suggest that Candidate Technologists consistently reported higher perceived value across all intervention strategies, while Candidate Certificated Engineers demonstrated the lowest levels of agreement.

3.2. Presentation of Qualitative Findings

This section presents the qualitative findings derived from open-ended responses provided by academic staff participants. Thematic analysis was employed to interpret patterns in the data, focusing on their insights regarding the causes of attrition in engineering education, the role of professional bodies such as ECSA, and strategies for improving student retention. The main themes identified included factors contributing to attrition, the role of ECSA and institutional partnerships, and strategies for retention. The analysis is supported by direct quotations from participants (labelled KP-1 to KP-10).

3.2.1. Factors Contributing to Attrition: Insights from Lecturers

A recurring theme from participant narratives was the inadequate foundational preparation that students bring from their basic education into higher education particularly in mathematics and science.

KP-10 pointed out that:

The quality of basic education received... fails to prepare students for the demand of the scientific fundamentals. KP-10

KP-5 further highlighted key factors that contributes to foundational gaps:

Poor Maths and Science schooling; Poor conception of engineering as a field.’ KP-5

KP-4 indicated that the gap in basic education can manifest through challenges with the language, compounding students' struggle to assimilate technical content.

The first challenge is the high school and university gap experienced by students from previously disadvantaged schools. The quality of basic education received by a vast majority of students (who are from the low income and working class households) fails to prepare students for the demand of the scientific fundamentals. Additionally, language can be a challenge. KP-4

The participants insights reflect a systemic issue manifested in a misalignment between secondary education and the academic demands of engineering programs. Van Broekhuizen, Van der Berg, & Hofmeyr (2016) found that the quality of school attended is a strong predictor of university success. Hlalele (2019) found that language remains a silent barrier for many students in rural and township schools. When students transition to English-dominant institutions, especially in STEM fields, they are at a double disadvantage where language delays conceptual understanding of already complex topics.

Financial challenges also emerged as one of the recurring barriers to student retention and success in engineering education. While the degree of emphasis varied across participants, most agreed that financial challenges play a critical role in academic attrition. According to KP-8, financial and logistical challenges intersects directly with attendance and academic engagement. KP-8 also noted a gap in funding structures that overlook basic living expenses such as food costs.

Financial constraints have a huge impact. Students who live far from campus and use public transport to reach campus may skip days of class to save on transport costs. Student loans cover accommodation, books and tuition, but do not contribute to food costs. KP-8

KP-4 made a significant observation and highlighted that bursary and funding models often don’t allow for academic setbacks which can cause attrition.

I think that a majority of students in all disciplines face significant financial constraints in higher education because of the socio-economic conditions of this country and their manifestation in higher education. This constraint means that students are faced with nutritional, resource and stress-related challenges that adversely impact their ability to focus on intellectual demands. Additionally, lack of funds means that there is no grace for failure, STEM students who obtained access through bursaries often lose them when they don’t pass - many of these structures don’t allow second chances, this adds psychological strain. KP-4

The literature also indicates that financial exclusion and food insecurity are major drivers of student dropout, especially in STEM faculties (Mkhize, 2024; Pitsoe & Letseka, 2018; Sallee, Kohler, Haumesser, & Hine, 2023). Similarly, Del Savio, Galantini and Pachas (2022) found that financial stress leads to higher dropout rates in engineering, not only because of resource gaps but also due to emotional burnout.

In contrast, KP-7 presented a counterargument:

In my opinion, it is not the financial constraints that are hampering engineering student's abilities, but rather their unsuitability to be an engineering student is hampering their ability. We provide everything the engineering student needs, from free data to computer labs fully connected to the internet, to components and equipment to do all their laboratories and experiments. Just put students with an aptitude for engineering in the lecture venues and the attrition rates will become a non-issue. Lastly, put the best engineering lecturers (based on merit and not DEI) into facilitate each classroom, and attrition will become a non-issue. KP-7

KP-7 suggested that institutions provide adequate resources such as free data, lab equipment, and internet access, implying that student failure is more about aptitude and motivation than financial hardship.

3.2.2. Institutional Challenges

The participants indicated that institutional challenges in addressing engineering student attrition are characterised by inconsistent and a lack of program-specific interventions. KP-9 indicated a lack of confidence in the depth or impact of existing interventions to reduce attrition.

A few initiatives… just not sure how effective is the reach. KP-9

Similarly, KP-4 noted that:

I have not come across any interventions that have specifically targeted to address the retention of engineering students. KP-4

KP-10 raised a critical concern regarding staff support, arguing that:

Academics have no support time or resources for academic development… All institutions do this superficially. KP-10

KP-7 outlined that while support structures exist, some retention strategies may prioritise throughput over genuine academic fit or quality.

Several support structures exist for struggling students that deal with Psychological Self-Image issues to Time-management skills to Study Techniques, to Tutoring Mentors, etc. Unfortunately, Government Subsidies encourage Institutions to "help" students that shouldn't be studying engineering to be successful enough to graduate, but these students are the ones that contribute to the high attrition rates. KP-7

On a more optimistic note, KP-1 indicated existing strategies at their institution used to support engineering students:

We have Academic Success Coaches to address study skills and educational barriers. The student counselling unit and student health centre are available for all students. We are trying to introduce more academic advising, especially for students who have failed multiple courses, to help them to make realistic and efficient subject courses when registering. KP-1

The above comments are similar with the findings of the study conducted by Boughey & McKenna (2016) which highlighted that institutional support in South Africa is often fragmented, under-resourced, and disconnected from students’ lived experiences.

3.2.3. Role of ECSA and Institutional Partnerships

Participants emphasised the need for ECSA to go beyond compliance checks and become a transformational partner in addressing socio-academic challenges within engineering education. KP-2 stated that:

ECSA must do real QA of academic programs, not just box-ticking exercises. KP-2

Accreditation must look at pedagogy and curriculum design—not just admin compliance. KP-10

KP-2 and KP-10 suggests that ECSA must focus on quality assurance model that does not only prioritise procedural compliance than educational effectiveness, curriculum quality or student-centred outcomes.

Moreover, KP-4 calls for a fundamental reimagining of ECSA’s role:

As the custodian and enforcer of the Engineering Profession Act, ECSA can do more as a public body to directly address the socio-economic challenges faced by engineering students whose higher education journey does not loophole them out of the South African challenges. ECSA needs to develop ways to be more than a policy creator, and instead develop ways to be a policy enabler and supporter of the disadvantaged. ECSA needs to consider how it can start setting up policies and structures that are contextual and drive universities to address the socio-economic and socio-cultural challenges through curriculum delivery. KP-4

KP-4 emphasised the need for contextual policy design, where ECSA works collaboratively with universities to embed social responsiveness into curriculum and support systems, particularly for historically marginalized groups.

KP-9 echoed a similar view, arguing that ECSA

ECSA must play a participatory role rather than just the perceived accreditation gatekeeping role. KP-9

Winberg, McKenna, & Wilmot (2020) advocates for regulatory bodies to shift from accountability frameworks toward developmental support, where institutions are empowered through partnerships rather than penalized for non-compliance.

3.2.4. Strategies for Retention

Participants identified a range of practical, evidence-informed strategies to improve retention in engineering programs. KP-5 recommended a shift toward learner-centred support systems that acknowledge the diverse educational and social backgrounds of students.

Scaffolded, mentored, extended programmes with contextualised and engaged learning KP-5

In addition to academic strategies, KP-5 also added other retention strategies including:

Career advice, mentorship, visibility of ECSA on campuses. KP-5

KP-3 proposed a systemic approach:

We need to foster deeper connections between industry and universities, as well as developing a greater identity of engineers, technologists, and technicians as part of an ecosystem. These are marketing opportunities which could be incentivised by the structures already in place for registration. KP-3

KP-8 stressed the value of proactive support, noting:

Early detection and sufficient resource to support where applicable. KP-8

Winberg, Adendorff, Bozalek, Conana, Pallitt, Wolff, Olsson and Roxå (2019) emphasised interverntions centrered around the importance of building professional identity in engineering education, noting that students who understand the value and scope of the profession are more likely to persist. Ahmed, Muldoon and Elsaadany (2021) found that structured mentorship programs improved students’ sense of belonging and resilience

4. Discussion of the Findings

Attrition in engineering education is influenced by a complex mix of academic, socio-economic, and institutional factors. Across the data, academic staff reflected a shared concern that students are not adequately prepared for the rigors of engineering programs. The academic pressures, particularly the overwhelming workload experienced during the first year of study, emerged as a critical factor contributing to early student attrition in engineering programmes. The transition from secondary to tertiary education has been identified in the literature as challenging for students who lack the foundational competencies in mathematics, science, and academic literacy (Hlalele, 2019; Van Broekhuizen, et al., 2016). According to Hlalele (2019), the initial academic shock can lead to a rapid decline in confidence and performance, especially in highly technical fields such as engineering.

The findings of this study highlight that academic factors, particularly workload and self-regulation skills, play a critical role in engineering student attrition. Qualitative responses from academic staff revealed that beyond academic preparedness in mathematics and science, competencies such as time management, self-discipline, and independent learning are essential for success in engineering programmes. Several participants noted that many students, particularly those from under-resourced schooling backgrounds, enter higher education without these foundational skills, making it difficult to cope with the intensive demands of the curriculum.

Quantitative results support this perspective. The Kruskal-Wallis test identified a statistically significant difference in perceptions of academic workload across candidacy categories, with Candidate Engineers reporting the highest levels of difficulty, suggesting they experience the most pressure. In contrast, Candidate Technologists and Candidate Technicians reported higher levels of perceived manageability. These findings point to a mismatch between institutional expectations and student readiness, especially in the early stages of engineering education. These insights are consistent with previous studies which have found that academic workload and inadequate time management are common predictors of student dropout in STEM fields (Aina, Aktaş, & Casalone, 2024; Ejiwale, 2013; González-Pérez, Martínez-Martínez, Rey-Paredes & Cifre, 2022; Ortiz-Lozano, Rua-Vieites, Bilbao-Calabuig, & Casadesús-Fa, 2020). Ortiz-Lozano et al. (2020) argued that persistence in higher education is closely linked to academic and social integration, and that students who are overwhelmed early in their studies are less likely to remain enrolled. Similarly, Aina et al. (2024) emphasised that engineering students must be supported not only through academic content but also through structured interventions that develop soft skills, such as planning and self-directed learning.

While no statistically significant differences were found across candidacy groups in terms of perceptions of financial support, qualitative data confirmed that financial challenges remains a systemic barrier. The lecturers frequently mentioned that students from low-income households struggle with food insecurity, transport costs, and rigid bursary structures that offer little room for academic recovery. These insights are consistent with prior research showing that financial stress impacts both academic performance and mental health (Pitsoe & Letseka, 2018; Sallee et al., 2023).

Moreover, Candidate Engineers reported the highest satisfaction with institutional resources while Candidate Certificated Engineers reported the lowest. This reflected discrepancies in access to labs, software, and learning tools across different streams or institutions. However, no significant differences were found regarding institutional support services or staff responsiveness. Yet, the qualitative responses painted a more complex picture, with some lecturers describing institutional support as fragmented, under-resourced, and insufficiently targeted. This supports Boughey and McKenna’s (2016) findings that academic development efforts in South Africa often lack depth and coherence.

Another key insight that emerged from both groups of participants is the need for ECSA to shift from a regulatory to a more developmental and participatory role. Statistically significant differences were found in how different candidate categories perceived the value of ECSA-academic collaboration and joint initiatives. However, other lecturers expressed concerns that ECSA’s current role is overly focused on procedural compliance, with little emphasis on pedagogical quality or social responsiveness. As suggested by Winberg, McKenna, and Wilmot (2020), professional bodies must evolve into partners that enable transformation rather than enforcing rigid accreditation processes. ECSA is thus encouraged to develop contextual and enabling policies, in collaboration with universities, that address the socio-academic realities of students.

Multiple retention strategies were identified across the data, many of which received statistically significant support in the survey. These included enhanced mentorship and academic advising, improved institutional resources, scaffolded and learner-centred programmes, stronger mentorship structures, and greater career exposure and industry engagement. Literature reinforces the value of professional identity development and resilience-building through structured mentorship (Pitsoe & Letseka, 2018; Sallee et al., 2023; Winberg et al., 2020).

5. Conclusion

The findings emphasise that student attrition in engineering is not the result of a single factor, but rather a convergence of academic, socio-economic, institutional, and systemic issues. Addressing this complex challenge requires a coordinated approach involving universities, ECSA, and broader educational reforms. Ultimately, reducing attrition and improving retention in engineering education is not only a matter of academic performance but a national imperative tied to transformation, skills development, and social justice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L, NT, S and B.; methodology, N.T.; software, N.T.; validation, L, NT and S; formal analysis, N.T.; investigation, L, NT and S; resources, L, NT and S; data curation, L and NT; writing—original draft preparation, NT and L ; writing—review and editing, L, NT and S; visualization, NT and L.; project administration, L, NT, B and S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Review Board of the Engineering Council of South Africa (November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

The data is unavailable in public platforms due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPTfor the purposes of brainstorming. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECSA |

Engineering Council of South Africa |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Ahmed, M., Muldoon, T. J., & Elsaadany, M. (2021). Employing faculty, peer mentoring, and coaching to increase the self-confidence and belongingness of first-generation college students in biomedical engineering. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, 143(12), 121001. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N., Kloot, B., & Collier-Reed, B. I. (2014). Why students leave engineering and built environment programmes when they are academically eligible to continue. European Journal of Engineering Education, 40(2), 128-144. [CrossRef]

- Aina, C., Aktaş, K., & Casalone, G. (2024). Effects of workload allocation per course on students’ academic outcomes: Evidence from STEM degrees. Labour Economics, 90. [CrossRef]

- Bernold, L. E., Spurlin, J. E., & Anson, C. (2007). Understanding Our Students: A Longitudinal-Study of Success and Failure in Engineering With Implications for Increased Retention. Journal of Engineering Education, 96(3), 263-274. [CrossRef]

- Boughey, C., & McKenna, S. (2016). Academic literacy and the decontextualised learner. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning (CriSTaL), 4(2), 1-9.

- Boughey, C., & McKenna, S. (2016). Academic literacy and the decontextualised learner. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning, 4(2), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- BusinessTech. (2015). Shocking number of engineering dropouts at SA universities. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/101122/shocking-number-of-engineering-dropouts-at-sa-universities/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Del Savio, A. A., Galantini, K., & Pachas, A. (2022). Exploring the relationship between mental health-related problems and undergraduate student dropout: A case study within a civil engineering program. Heliyon, 8(5). [CrossRef]

- ECSA. (2022). Engineering Skills Pipeline. Johannesburg: ECSA.

- ECSA. (2024). About Us: What is ECSA. Retrieved July 1, 2024, from https://ecsa.co.za/about/SitePages/What%20Is%20ECSA.aspx.

- Ejiwale, J. A. (2013). Barriers to successful implementation of STEM education. Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn), 7(2), 63-74. [CrossRef]

- González-Pérez, S., Martínez-Martínez, M., Rey-Paredes, V., & Cifre, E. (2022). I am done with this! Women dropping out of engineering majors. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. [CrossRef]

- Hlalele, D. J. (2019). Indigenous knowledge systems and sustainable learning in rural South Africa. Australian and international journal of rural education, 29(1), 88-100. [CrossRef]

- Mkhize, Z. (2024). First-Generation African Students in STEM Disciplines in South African Universities. Journal of First-generation Student Success, 4(3), 221-241. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Lozano, J. M., Rua-Vieites, A., Bilbao-Calabuig, P., & Casadesús-Fa, M. (2020). University student retention: Best time and data to identify undergraduate students at risk of dropout. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 57(1), pages 1303-1316. [CrossRef]

- Pitsoe, V., & Letseka, M. (2018). Access to and widening participation in South African higher education. In Contexts for diversity and gender identities in higher education: International perspectives on equity and inclusion (pp. 113-125). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Pocock, J. (2012). Leaving rates and reasons for leaving in an Engineering faculty in South Africa: A case study. South African Journal of Science, 108(3), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Sallee, M. W., Kohler, C. W., Haumesser, L. C., & Hine, J. C. (2023). Falling through the cracks: Examining one institution’s response to food insecure student-parents. The Journal of Higher Education, 94(4), 415-443. [CrossRef]

- Van Broekhuizen, H., Van der Berg, S., & Hofmeyr, H. (2016). Higher education access and outcomes for the 2008 South African national matric cohort (No. 10358). Stellenbosch University Economic Working Papers.

- Winberg, C., Adendorff, H., Bozalek, V., Conana, H., Pallitt, N., Wolff, K., Olsson, T. and Roxå, T., (2019). Learning to teach STEM disciplines in higher education: A critical review of the literature. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(8):930-947. [CrossRef]

- Winberg, C., McKenna, S., & Wilmot, K. (2020). Building knowledge in higher education. London: Routledge.

- Winberg, C., McKenna, S., & Wilmot, K. (2020). Building knowledge in higher education. London: Routledge.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).