Submitted:

02 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Data Mining in Hospitality Industry

| Researcher(s)/Year | Target(s) | Tool(s) | Result(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Mohammadrezapour et al., 2020) [23] | Comparing two clustering methods | K-means, C-means | C-means yielded higher accuracy than K-means |

| (Matz and Hermawan, 2020) [24] | Proposing a model for a cluster of a loyal customer | LRIFMQ, CLV, AHP, k-means | Customers were grouped into six clusters |

| (Mahdiraji et al., 2019) [25] | Clustering and ranking bank customers using RFM | RFM modeling, BWM, COPRAS | Classifying customers into six clusters and selected two groups as influential ones |

| (Syakur et al., 2018) [26] | Determining the best number of clusters | K-means, elbow method | Defining an appropriate number of clusters using the elbow method |

| (Doğan et al., 2018) [27] | Clustering retail customers | RFM modeling, K-means, Two-step | Comparing two types of clustering results |

| (Mosavi and Afsar, 2018) [11] | Analyzing bank customers’ value | FAHP, K-means, random forest classification | Presenting the model according to the applied attributes |

| (Peker et al., 2017) [28] | Developing services and increasing profits | LRFMP, K-means, Calinski-Harabasz, Davies-Bouldin, Silhouette | Clustering customers into five groups |

| (Dursun and Caber, 2016) [1] | Clustering hotel customers | RFM modeling, K-means | Offering proper strategies to each group |

| (Ansari and Riasi, 2016) [12] | Combining data mining methods to cluster steel industries’ customers | LRFM modeling, Two-step, genetic algorithm, C-means | Classifying customers into two groups, rendering tailored strategies |

| (Ganjali and Teimourpour, 2016) [29] | Clustering insurance customers | K-means, CLV, association rule, decision tree, Davies-Bouldin | Classifying customers into five clusters |

| (Sarvari and Ustundag, 2016) [30] | Clustering fast-food customers | Associated rules, RFML modeling, K-means | Having proper groups is critical to forming strong associations |

| (Abirami and Pattabiraman, 2016) [31] | Clustering customers | RFM modeling, K-means, Association Rules | Predicting customers’ behavior, improving customer satisfaction |

| (Srihadi et al., 2016) [10] | Clustering foreign customers | K-means | Identifying groups, proposing proper strategies |

| (Chang et al., 2009) [32] | Finding important variables influenced by customer loyalty | Decision tree analysis | Exploring customer behavior |

| (Mohammadian and Makhani, 2016) [33] | Analyzing data to identify customer intentions | RFM modeling, CLV | Grouping customers into eight clusters to understand customers |

| (You et al., 2015) [34] | Clustering customers | RFM modeling, K-means, CHAID decision trees, Pareto Values | Offering precision marketing strategies |

| (Dimitrovski and Todorović, 2015) [35] | Understanding customer behavior | K-means, chi-square test, Hierarchical method | Understanding visitor intentions, presenting appropriate promotions |

| (Wei et al., 2013) [36] | Clustering hairdressing industry customers | K-means, RFM modeling | Identifying customers, offering proper strategies |

| (Chen et al., 2012) [19] | Understanding retail customers | K-means, RFM modeling, decision tree | Classifying customers into five clusters |

| (Liao et al., 2012) [37] | Finding hidden patterns in data | K-means, Apriori algorithm | Exploring group-buying customer behavior |

| (Hosseini et al., 2010) [38] | Clustering SAPCO customers | K-means, WRFM, CLV | Assessing customers, proposing an effective model for understanding customers |

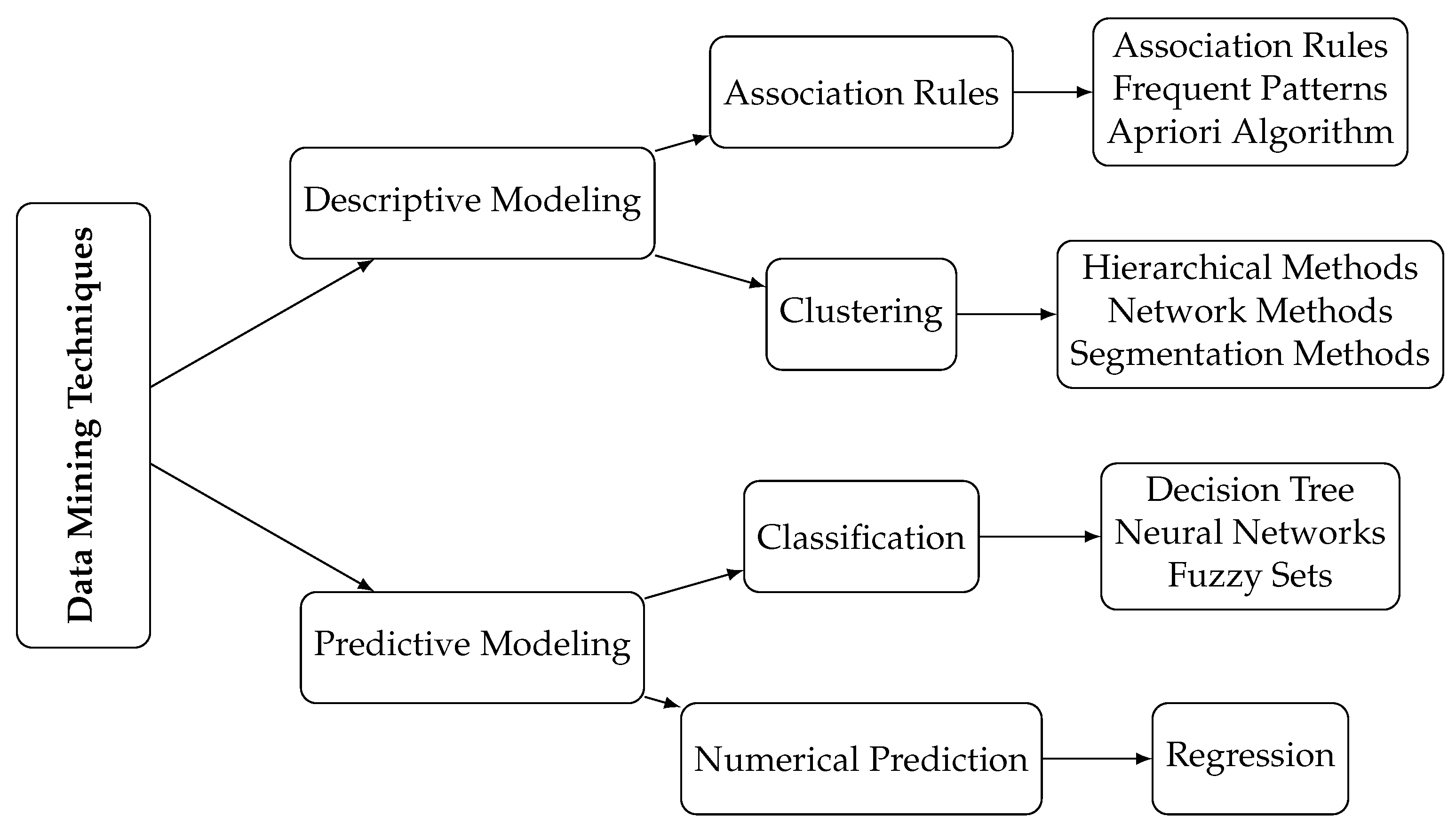

2.2. Customer Segmentation Techniques

2.3. RFM vs. RMD: The Need for an Enhanced Segmentation Model

3. Basic Concepts

3.1. K-Means

3.2. Association Rules and Customer Behavior Analysis

3.3. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) Approaches for Customer Prioritization

3.3.1. Shannon Entropy

3.3.2. TOPSIS

3.3.3. BWM

3.3.4. CLV

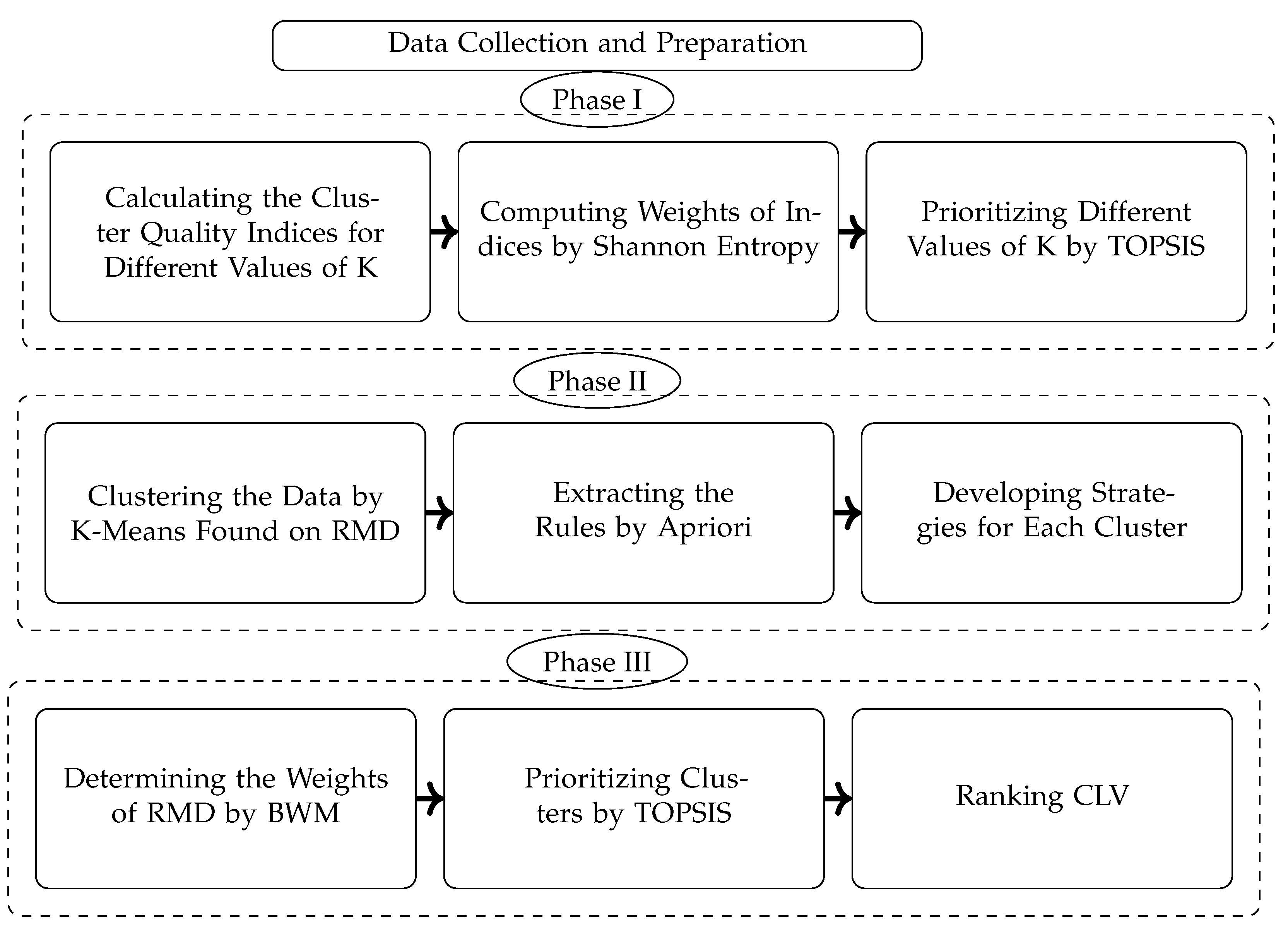

4. Research Methodology

5. Case study and Results

5.1. Clustering Model

| Number of k | Silhouette | Davies-Bouldin | Calinski-Harabasz |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight of validity indices | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.28 |

| 2 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 831.2 |

| 3 | 0.82 | 0.62 | 1096.65 |

| 4 | 0.78 | 0.66 | 1287.77 |

| 5 | 0.70 | 0.63 | 1347.64 |

| 6 | 0.73 | 0.61 | 1602.60 |

| 7 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 1484.12 |

| 8 | 0.74 | 0.70 | 1654.36 |

| 9 | 0.73 | 0.68 | 1613.19 |

| 10 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 1652.56 |

| RMD Indices | Minimum | Maximum | St. dev. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R (Recency) | 10 | 365 | 126.8 | 97.0 |

| M (Monetary) | 667 | 4724 | 1252.3 | 501.6 |

| D (Duration) | 1 | 12 | 3.4 | 1.6 |

| Clusters | N | RMD Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 579 | 1.00 | 414.10 | 211.60 | R↑M↓D↓ |

| 2 | 24 | 8.45 | 3221.50 | 202.58 | R↑M↑D↑ |

| 3 | 81 | 3.66 | 1214.61 | 185.40 | R↑M↓D↑ |

| 4 | 26 | 2.76 | 1314.88 | 14.00 | R↓M↑D↓ |

| 5 | 315 | 3.57 | 806.17 | 114.01 | R↓M↓D↑ |

| 6 | 81 | 1.32 | 542.76 | 33.75 | R↓M↓D↓ |

| Total | 1107 | 3.46 | 1252.34 | 126.84 |

5.2. Clustering Analysis

5.3. Association Rule Results

5.4. Comparison and Evaluation of Clusters

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Contextual Insights

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- A. Dursun and M. Caber, (2016), Using data mining techniques for profiling profitable hotel customers: An application of RFM analysis, Tour Manag Perspect, 18, 153-160.

- P. Ristoski and H. Paulheim, (2016), Semantic Web in data mining and knowledge discovery: A comprehensive survey, Journal of Web Semantics, 36, 1-22, Accessed: Feb. 27, 2025, [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1570826816000020.

- J. A. McCarty and M. Hastak, (2007), Segmentation approaches in data-mining: A comparison of RFM, CHAID, and logistic regression, J Bus Res, 60, 6, 656-662.

- Y. H. Hu and T. W. Yeh, (2014), Discovering valuable frequent patterns based on RFM analysis without customer identification information, Knowl Based Syst, 61, 76-88.

- V. Kumar, Y. Bhagwat, and X. Zhang, (2015), Regaining ‘lost’ customers: The predictive power of first-lifetime behavior, the reason for defection, and the nature of the win-back offer, J Mark, 79, 4, 34-55, Jul. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Jain, (2010), Data clustering: 50 years beyond K-means, Pattern Recognit Lett, 31, 8, 651-666, Accessed: Feb. 24, 2025, [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167865509002323.

- P. Rousseeuw, (1987), Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis, J Comput Appl Math, 20, 53-65, Nov., Accessed: Feb. 27, 2025, [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0377042787901257.

- T. Calinski and J. Harabasz, (1974), A dendrite method for cluster analysis, Communications in Statistics, 3, 1, 1-27, Accessed: Mar. 02, 2025.

- D. Davies and D. W. Bouldin, (1979), A cluster separation measure, IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell, 1, 2, 224-227, Accessed: Mar. 02, 2025, [Online]. Available:.

- T. F. Srihadi, D. Sukandar, and A. W. Soehadi, (2016), Segmentation of the tourism market for Jakarta: Classification of foreign visitors’ lifestyle typologies, Tour Manag Perspect, 19, 32-39.

- A. B. Mosavi and A. Afsar, (2018), Customer value analysis in banks using data mining and fuzzy analytic hierarchy processes, Int J Inf Technol Decis Mak, 17, 03, 819-840.

- A. Ansari and A. Riasi, (2016), Customer clustering using a combination of fuzzy c-means and genetic algorithms, International Journal of Business and Management, 11, 7, 59.

- Y. Tu, K. Chen, H. Wang, and Z. Li, (2020), Regional Water Resources Security Evaluation Based on a Hybrid Fuzzy BWM-TOPSIS Method, Int J Environ Res Public Health, 17, 14, 4987.

- A. Çalık, S. L. Sain, and K. Guo, (2020), Evaluation of Social Media Platforms using Best Worst Method and Fuzzy VIKOR Methods: A Case Study of Travel Agency, Iranian Journal of Management Studies, 19, 3, 197-208. [CrossRef]

- G. George, M. R. Haas, and A. Pentland, (2014), Big data and management, Academy of Management Journal, 57, 2, 321-326.

- C. H. Cheng and Y. S. Chen, (2009), Classifying the segmentation of customer value by the RFM model and RS theory, Expert Syst Appl, 36, 3, 4176-4184.

- S. Erevelles, N. Fukawa, and L. Swayne, (2016), Big Data consumer analytics and the transformation of marketing, J Bus Res, 69, 2, 897-904, Accessed: Mar. 02, 2025, [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0148296315002842.

- G. D. Samarasinghe and D. S. R. Samarasinghe, (2013), Green decisions: Consumers’ environmental beliefs and green purchasing behaviour in Sri Lankan context, International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development, 7, 2, 172-184. [CrossRef]

- D. Chen, Sai. L. Sain, and K. Guo, (2012), Data mining for the online retail industry: A case study of RFM model-based customer segmentation using data mining, Journal of Database Marketing & Customer Strategy Management, 19, 3, 197-208, Sep. [CrossRef]

- M. Ostovare and M. R. Shahraki, (2019), Evaluation of hotel websites using the multicriteria analysis of PROMETHEE and GAIA: Evidence from the five-star hotels of Mashhad, Tour Manag Perspect, 30, 107-116.

- C.-I. Ho and Y.-L. Lee, (2007), The development of an e-travel service quality scale, Tour Manag, 28, 6, 1434-1449.

- R. Law, S. Qi, and D. Buhalis, (2010), Progress in tourism management: A review of website evaluation in tourism research, Tour Manag, 31, 3, 297-313.

- O. Mohammadrezapour, O. Kisi, and F. Pourahmad, (2020), Fuzzy c-means and K-means clustering with genetic algorithm for identification of homogeneous regions of groundwater quality, Neural Comput Appl, 32, 8, 3763-3775.

- A. Matz and A. T. Hermawan, (2020), Customer Loyalty Clustering Model Using K-Means Algorithm with LRIFMQ Parameters, Inform, 5, 2, 54-61.

- H. A. Mahdiraji, E. K. Zavadskas, A. Kazeminia, and A. A. Kamardi, (2019), Marketing strategies evaluation based on big data analysis: A CLUSTERING-MCDM approach, Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 32, 1, 2882-2898.

- M. A. Syakur, B. K. Khotimah, E. M. S. Rochman, and B. D. Satoto, (2018), Integration k-means clustering method and elbow method for identification of the best customer profile cluster, IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng, 336, 1.

- O. Doğan, E. Ayçin, and Z. A. Bulut, (2018), Customer Segmentation by Using RFM Model and Clustering Methods: A Case Study in Retail Industry, International Journal of Contemporary Economics and Administrative Sciences, 8, 1, 1-19.

- S. Peker, A. Kocyigit, and P. E. Eren, (2017), LRFMP model for customer segmentation in the grocery retail industry: A case study, Marketing Intelligence & Planning.

- M. Ganjali and B. Teimourpour, (2016), Identify Valuable Customers of Taavon Insurance in Field of Life Insurance with Data Mining Approach, UCT Journal of Research in Science, Engineering and Technology, 4, 1, 1-10.

- P. A. Sarvari, A. Ustundag, and H. Takci, (2016), Performance evaluation of different customer segmentation approaches based on RFM and demographics analysis, Kybernetes.

- M. Abirami and V. Pattabiraman, (2016), Data mining approach for intelligent customer behavior analysis for a retail store, The 3rd International Symposium on Big Data and Cloud Computing Challenges, 283-291.

- H. H. Chang, Y. H. Wang, and W. Y. Yang, (2009), The impact of e-service quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty on e-marketing: Moderating effect of perceived value, Total Quality Management and Business Excellence, 20, 4, 423-443, Apr. [CrossRef]

- M. Mohammadian and I. Makhani, (2016), RFM-Based customer segmentation as an elaborative analytical tool for enriching the creation of sales and trade marketing strategies, International Academic Journal of Accounting and Financial Management, 3, 6, 21-35.

- Z. You, Y.-W. Si, D. Zhang, X. Zeng, S. Leung, and T. Li, (2015), A decision-making framework for precision marketing, Expert Syst Appl, 42, 7, 3357-3367.

- D. Dimitrovski and A. Todorovic, (2015), Clustering wellness tourists in spa environment, Tour Manag Perspect, 16, 259-265, Accessed: Mar. 02, 2025, [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211973615300040.

- J. T. Wei, M. C. Lee, H. K. Chen, and H. H. Wu, (2013), Customer relationship management in the hairdressing industry: An application of data mining techniques, Expert Syst Appl, 40, 18, 7513-7518.

- S. H. Liao, Y. J. Chen, and M. Y. Deng, (2010), Mining customer knowledge for tourism new product development and customer relationship management, Expert Syst Appl, 37, 6, 4212-4223.

- S. M. Hosseini, A. Maleki, and M. R. Gholamian, (2010), Cluster analysis using a data mining approach to develop CRM methodology to assess customer loyalty, Expert Syst Appl, 37, 5259-5264.

- H. A. Mahdiraji, E. Kazimieras Zavadskas, A. Kazeminia, and A. Abbasi Kamardi, (2019), Marketing strategies evaluation based on big data analysis: A CLUSTERING-MCDM approach, Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 32, 1, 2882-2898, Jan. [CrossRef]

- W. Y. Loh and Y. S. Shih, (1997), Split selection methods for classification trees, Statistica Sinica, 815-840.

- G. H. Laursen, (2011), Business analytics for sales and marketing managers: How to compete in the information age, 41, John Wiley & Sons.

- J. T. Wei, S. Y. Lin, and H. H. Wu, (2010), A review of the application of the RFM model, African Journal of Business Management, 4, 19, 4199.

- R. Kahan, (1998), Using database marketing techniques to enhance your one-to-one marketing initiatives, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 15, 5, 491-493.

- J. Miglautsch, (2000), Thoughts on RFM scoring, Journal of Database Marketing & Customer Strategy Management, 8, 1, 67-72.

- P. Baecke and D. Poel, (2011), Data augmentation by predicting spending pleasure using commercially available external data, J Intell Inf Syst, 36, 3, 367-383.

- P. Hanafizadeh and M. Mirzazadeh, (2011), Visualizing market segmentation using self-organizing maps and the Fuzzy Delphi method-ADSL market of a telecommunication company, Expert Syst Appl, 38, 1, 198-205.

- A. Mesforoush and M. J. Tarokh, (2013), Customer profitability segmentation for SMEs case study: Network equipment company, International Journal of Research in Industrial Engineering, 2, 1, 30-44.

- T. Calinski and J. Harabasz, (1974), A dendrite method for cluster analysis, Commun Stat Theory Methods, 3, 1, 1-27. [CrossRef]

- D. L. Davies and D. W. Bouldin, (1979), A Cluster Separation Measure, IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell, PAMI-1, 2, 224-227. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, W. Gong, and Y. Kawamura, (2004), Customer behavior pattern discovering with web mining, Asia-Pacific Web Conference, 844-853.

- S. Ramasamy and K. Nirmala, (2020), Disease prediction in data mining using association rule mining and keyword-based clustering algorithms, International Journal of Computers and Applications, 42, 1, 1-8.

- P. Yoon and C.-L. Hwang, (1995), Multiple attributes decision making: An introduction, 31, 8, Sage Publications.

- M. A. Alao, T. R. Ayodele, A. S. O. Ogunjuyigbe, and O. M. Popoola, (2020), Multi-criteria decision-based waste to energy technology selection using entropy-weighted TOPSIS technique: The case study of Lagos, Nigeria, Energy, 117675.

- Y. Wang, Z. Wen, and H. Li, (2020), Symbiotic technology assessment in iron and steel industry based on entropy TOPSIS method, J Clean Prod, 120900.

- J. Rezaei, (2015), Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method, Omega (Westport), 53, 49-57.

- S. Guo and H. Zhao, (2017), Fuzzy best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method and its applications, Knowl Based Syst, 121, 23-31.

- M. Khalilzadeh, L. Katoueizadeh, and E. K. Zavadskas, (2020), Risk identification and prioritization in banking projects of payment service provider companies: An empirical study, Frontiers of Business Research in China, 14, 1, 1-27.

- M. Khajvand and M. J. Tarokh, (2011), Estimating customer future value of different customer segments based on adapted RFM model in retail banking context, Procedia Comput Sci, 3, 1327-1332, Accessed: Mar. 04, 2025.

- P. Kotler, (1973), Atmospherics as a marketing tool, Journal of Retailing, 49, 4, 48-64, Accessed: Mar. 04, 2025.

- A. Kasprova, (2020), Customer Lifetime Value for Retail Based on Transactional and Loyalty Card Data, Ukrainian Catholic Institution.

- Z. Kahreh, A. Shirmohammadi, and M. Kahreh, (2017), Explanatory study towards analysis the relationship between Total Quality Management and Knowledge Management, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 600-604, Accessed: Mar. 04, 2025.

- F. F. Reichheld and J. Sasser, (1996), Zero defections: Quality comes to services, Harv Bus Rev, 68, 5, 105-111, Accessed: Mar. 04, 2025.

- C. Gurau and A. Ranchhod, (2002), How to calculate the value of a customer–Measuring customer satisfaction: A platform for calculating, predicting and increasing customer profitability, Journal of Targeting, Measurement & Analysis for Marketing, 10, 3, 203, Accessed: Mar. 04, 2025.

| Attributes | NC | LC | CBC | PC | BC | LoC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMD scores | R↑M↓D↓ | R↑M↑D↑ | R↑M↓D↑ | R↓M↑D↓ | R↓M↓D↑ | R↓M↓D↓ |

| N | 579 (52.3%) | 24 (2.16%) | 81 (7.31%) | 26 (2.34%) | 315 (28.45%) | 81 (7.31%) |

| Gender | Male (68%) | Male & Female (50%-50%) | Male (69%) | Male & Female (50%-50%) | Male (65%) | Male (66%) |

| Age group | 21-30 (26%) | 41-50 (41%) | 31-40 (28%) | 31-40 (38%) | 31-40 (28%) | 21-30 (27%) |

| Nationality | Iraqi (24%) | Iraqi (45%) | Chinese (17.3%) | Iraqi & Chinese (15.3%-15.3%) | Iraqi (23%) | Iraqi (18.5%) |

| Travel companion | Alone (68.22%) | Two people (20%) | Two (38.2%) | Alone (38%) | Alone (65.7%) | 1 (51.1%) |

| Job | Freelance (64.7%) | Freelance (41.6%) | Freelance (39.5%) | Employee (38%) | Freelance (62.2%) | Tourist (72.8%) |

| Travel intentions | Tourism (58.5%) | Tourism (43%) | Tourism (49.38%) | Office work (34.6%) | Office work (34.9%) | Tourism (50.6%) |

| Duration (days) | 1 (100%) | 7 (33.33%) | 4 (44%) | 1 (50%) | 2 (74.3%) | 1 (76.5%) |

| Clusters | Rule | Confidence | Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| New customers | [male → Iraqi, freelance] | 94.5% | 16.5% |

| [tourism → tourist] | 93.5% | 11.3% | |

| Loyal customers | [freelance → Iraqi, men] | 100% | 12.5% |

| [tourism → tourist] | 100% | 12.5% | |

| Collective Buying Customers | [men → freelance, 41-50] | 100% | 11.11% |

| [tourism → Chinese, 31-40] | 100% | 11.11% | |

| Potential customers | [men → Chinese] | 100% | 15.3% |

| [employee → women, 31-40, office work] | 83.87% | 23.4% | |

| Business customers | [men → Iraqi, freelance] | 94.11% | 10.7% |

| [men → office work, Freelance] | 100% | 12.5% | |

| Lost customers | [tourism → 61-90, tourist] | 88% | 12.3% |

| Clusters | Cluster Ranking By TOPSIS | N | D | M | R | CLV | CLV Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 0 | 52.3 | 0.009 | 0.012 | 0.33 | 0.09 | CLV4 |

| C2 | 0.86 | 2.16 | 0.66 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.59 | CLV1 |

| C3 | 0.13 | 7.3 | 0.12 | 0.1 | 0.25 | 0.13 | CLV2 |

| C4 | 0.21 | 2.34 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.001 | 0.07 | CLV3 |

| C5 | 0.12 | 28.45 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.097 | 0.05 | CLV5 |

| C6 | 0.14 | 7.31 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.008 | 0.01 | CLV6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).