Submitted:

02 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Intervention and Treatment Protocol

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethics Statement

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

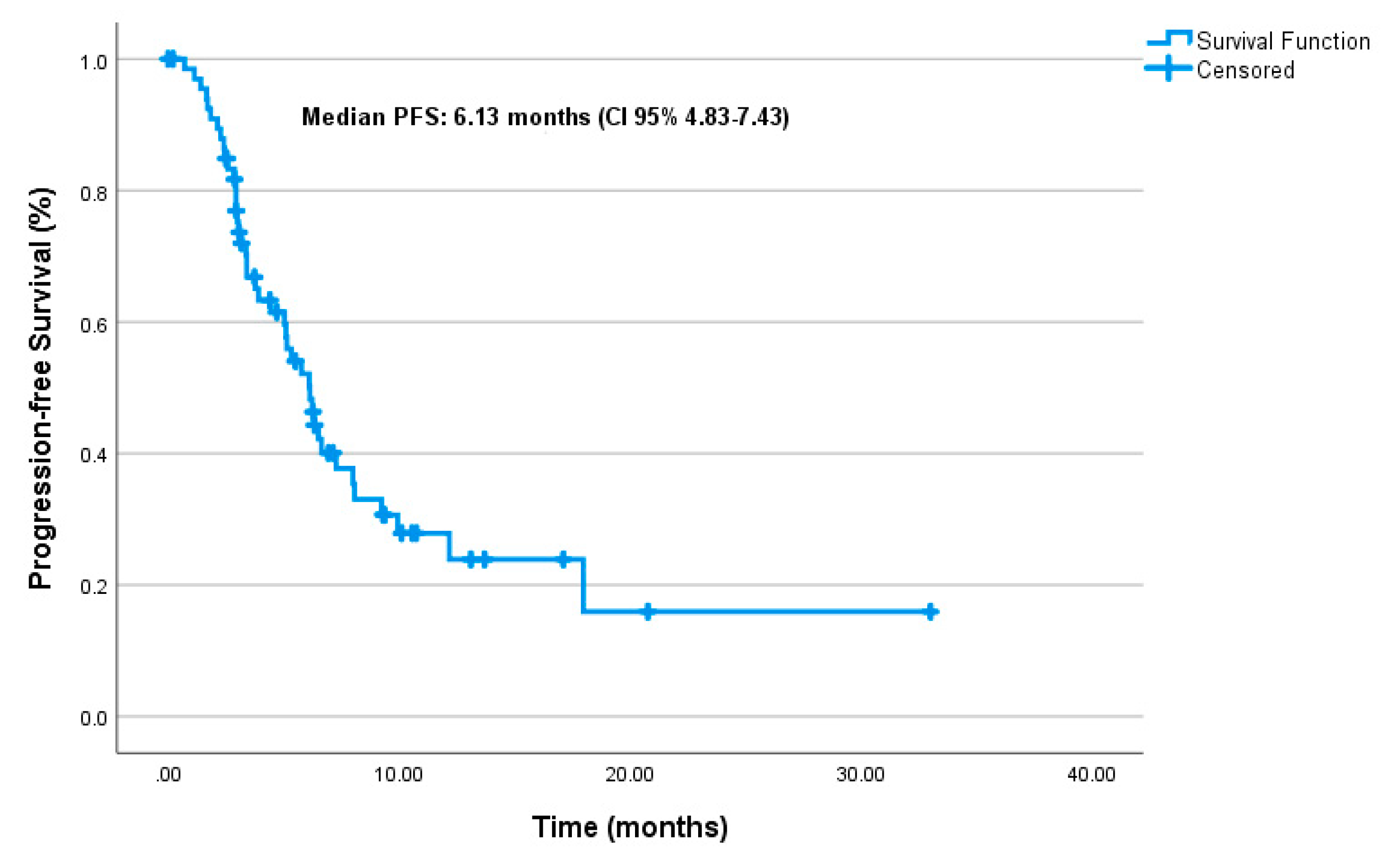

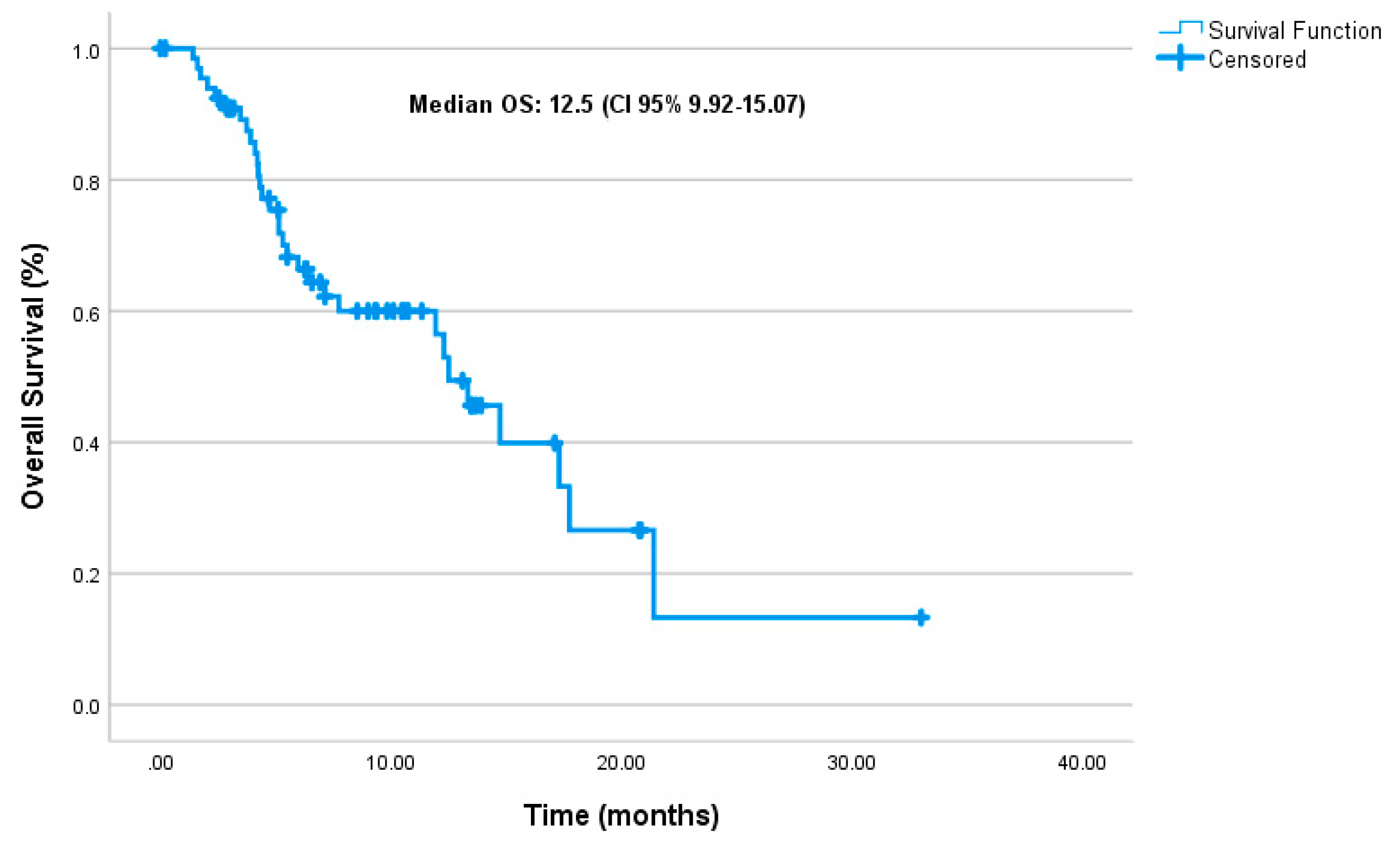

3.2. Effectiveness

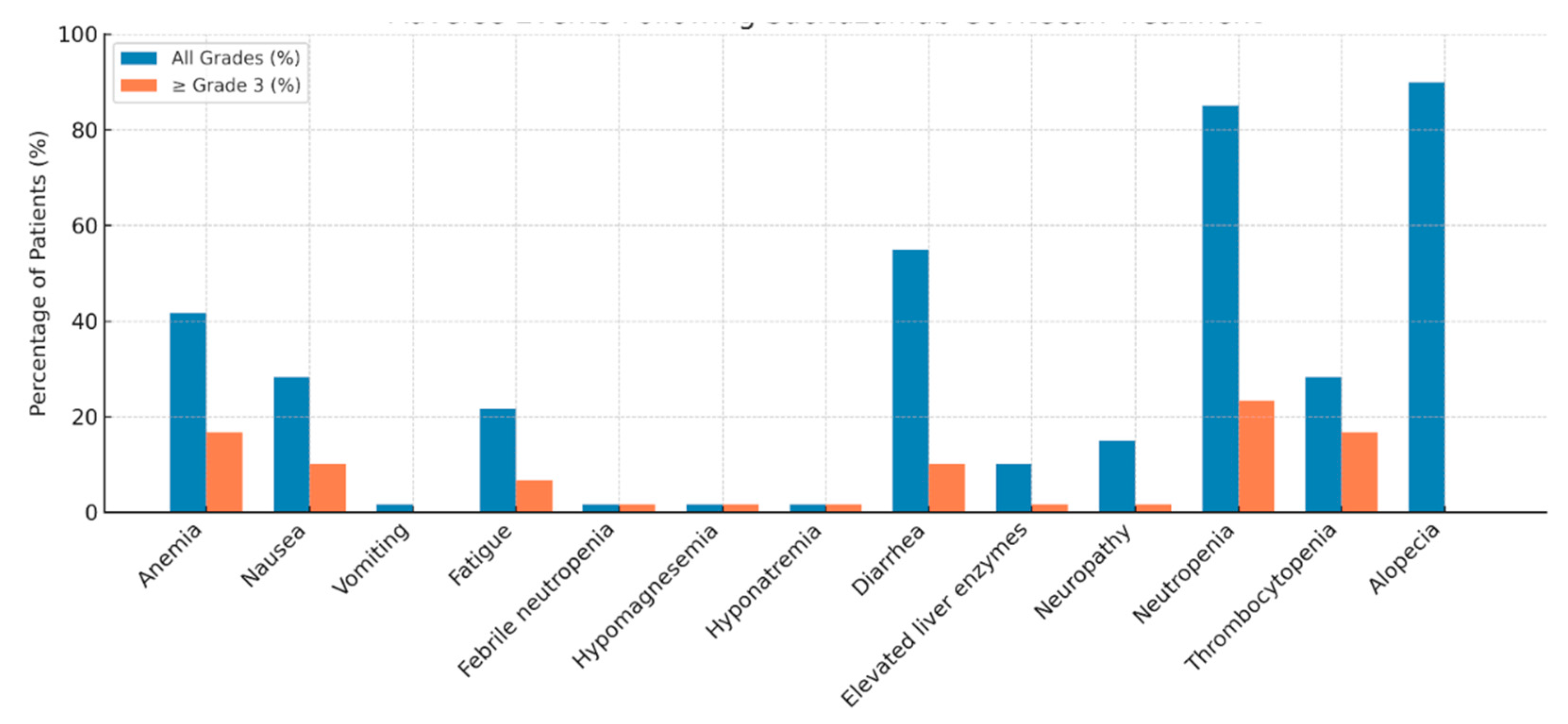

3.3. Safety and Adverse Events

4. Discussion

4.1. Real-World Effectiveness Compared to Clinical Trials

4.2. Safety and Tolerability Profile

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jallah JK, Dweh TJ, Anjankar A, Palma O. A review of the advancements in targeted therapies for breast cancer. Cureus. 2023;15(10). [CrossRef]

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2021;71(3):209-49. [CrossRef]

- Cuyún Carter G, Mohanty M, Stenger K, Morato Guimaraes C, Singuru S, Basa P, et al. Prognostic factors in hormone receptor-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HR+/HER2–) advanced breast cancer: a systematic literature review. Cancer Management and Research. 2021:6537-66.

- Gradishar WJ, Moran MS, Abraham J, Abramson V, Aft R, Agnese D, et al. NCCN Guidelines® insights: breast cancer, version 4.2023: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2023;21(6):594-608.

- Gennari A, André F, Barrios C, Cortes J, de Azambuja E, DeMichele A, et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer☆. Annals of oncology. 2021;32(12):1475-95.

- Li CH, Karantza V, Aktan G, Lala M. Current treatment landscape for patients with locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: a systematic literature review. Breast cancer research. 2019;21:1-14. [CrossRef]

- Diana A, Franzese E, Centonze S, Carlino F, Della Corte CM, Ventriglia J, et al. Triple-negative breast cancers: systematic review of the literature on molecular and clinical features with a focus on treatment with innovative drugs. Current oncology reports. 2018;20:1-11. [CrossRef]

- Nardin S, Del Mastro L. Sacituzumab Govitecan in HR-positive HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. Annals of Translational Medicine. 2023;11(5):228. [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg DM, Cardillo TM, Govindan SV, Rossi EA, Sharkey RM. Trop-2 is a novel target for solid cancer therapy with sacituzumab govitecan (IMMU-132), an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC). Oncotarget. 2015;6(26):22496. [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg DM, Sharkey RM. Sacituzumab govitecan, a novel, third-generation, antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) for cancer therapy. Expert opinion on biological therapy. 2020;20(8):871-85. [CrossRef]

- Nagayama A, Vidula N, Ellisen L, Bardia A. Novel antibody–drug conjugates for triple negative breast cancer. Therapeutic advances in medical oncology. 2020;12:1758835920915980. [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg DM, Stein R, Sharkey RM. The emergence of trophoblast cell-surface antigen 2 (TROP-2) as a novel cancer target. Oncotarget. 2018;9(48):28989. [CrossRef]

- Bardia A, Rugo HS, Tolaney SM, Loirat D, Punie K, Oliveira M, et al. Final results from the randomized phase III ASCENT clinical trial in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer and association of outcomes by human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and trophoblast cell surface antigen 2 expression. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2024;42(15):1738-44. [CrossRef]

- Rugo HS, Bardia A, Marmé F, Cortés J, Schmid P, Loirat D, et al. Overall survival with sacituzumab govitecan in hormone receptor-positive and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer (TROPiCS-02): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2023;402(10411):1423-33. [CrossRef]

- Spring LM, Nakajima E, Hutchinson J, Viscosi E, Blouin G, Weekes C, et al. Sacituzumab govitecan for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: clinical overview and management of potential toxicities. The Oncologist. 2021;26(10):827-34. [CrossRef]

- Püsküllüoğlu M, Pieniążek M, Las-Jankowska M, Streb J, Ziobro M, Pacholczak-Madej R, et al. Sacituzumab govitecan for second and subsequent line palliative treatment of patients with triple-negative breast cancer: a Polish real-world multicenter cohort study. Oncology and Therapy. 2024;12(4):787-801. [CrossRef]

- Reinisch M, Bruzas S, Spoenlein J, Shenoy S, Traut A, Harrach H, et al. Safety and effectiveness of sacituzumab govitecan in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer in real-world settings: first observations from an interdisciplinary breast cancer centre in Germany. Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology. 2023;15:17588359231200454. [CrossRef]

- Grinda T, Morganti S, Hsu L, Yoo T-K, Kusmick RJ, Aizer AA, et al. Real-World outcomes with sacituzumab govitecan among breast cancer patients with central nervous system metastases. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2025;11(1):22. [CrossRef]

- Kalinsky K, Spring L, Yam C, Bhave MA, Ntalla I, Lai C, et al. Real-world use patterns, effectiveness, and tolerability of sacituzumab govitecan for second-line and later-line treatment of metastatic triple-negative breast cancer in the United States. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2024;208(1):203-14. [CrossRef]

- Kang C. Sacituzumab Govitecan: A Review in Unresectable or Metastatic HR+/HER2− Breast Cancer. Targeted Oncology. 2024;19(2):289-96.

- W DeClue R, Fisher MD, Gooden K, Walker MS, Le TK. Real-world outcomes in metastatic HR+/HER2-, HER2+ and triple negative breast cancer after start of first-line therapy. Future Oncology. 2023;19(13):909-23. [CrossRef]

- Xu B, Wang S, Yan M, Sohn J, Li W, Tang J, et al. Sacituzumab govitecan in HR+ HER2− metastatic breast cancer: the randomized phase 3 EVER-132-002 trial. Nature Medicine. 2024;30(12):3709-16. [CrossRef]

- Caputo R, Buono G, Piezzo M, Martinelli C, Cianniello D, Rizzo A, et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan for the treatment of advanced triple negative breast cancer patients: a multi-center real-world analysis. Frontiers in oncology. 2024;14:1362641. [CrossRef]

- Alaklabi S, Roy AM, Zagami P, Chakraborty A, Held N, Elijah J, et al. Real-World Clinical Outcomes With Sacituzumab Govitecan in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. JCO Oncology Practice. 2024:OP. 24.00242. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo A, Rinaldi L, Massafra R, Cusmai A, Guven DC, Forgia DL, et al. Sacituzumab govitecan vs. chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer: a meta-analysis on safety outcomes. Future Oncology. 2024;20(20):1427-34. [CrossRef]

- Hanna D, Merrick S, Ghose A, Devlin MJ, Yang DD, Phillips E, et al. Real world study of sacituzumab govitecan in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Cancer. 2024;130(12):1916-20. [CrossRef]

- Sathe AG, Diderichsen PM, Fauchet F, Phan SC, Girish S, Othman AA. Exposure-Response Analyses of Sacituzumab Govitecan Efficacy and Safety in Patients With Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2025;117(2):570-8. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Li H, Yang W, Shi Y. Improving efficacy of TNBC immunotherapy: based on analysis and subtyping of immune microenvironment. Frontiers in immunology. 2024;15:1441667. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Value |

| Age (median, range) | 48(29-78) |

|

De novo metastasis Molecular classification |

18(26.5%) |

| mTNBC mHRPBC |

35(51.5%) 33(48.5%) |

|

Her2 Status Her2 0 Her2 +1 Her2 +2 (FISH negative) |

52(76.4%) 10(14.7%) 6(8.8%) |

|

ECOG PS 0 1 Metastatic Sites Liver Lung |

48(70.6%) 20(29.4%) 35(51.5%) 39(57.4%) |

| Brain | 29(42.6%) |

| Bone | 39(57.4%) |

| Lymph Node |

58(85.3%) |

| Prior Immunotherapy | 22(32.4%) |

| Dose reduction due to Toxicity | 20(29.4%) |

| Treatment discontinuation due to toxicity | 2(2.9%) |

|

Prior Chemotherapy Agents Taxane Anthracycline Carboplatin Capecitabine |

64(94.1%) 54(79.4%) 48(70.6%) 53(77.9%) |

| Local Treatment | 60(88.2%) |

|

Prior Lines of Therapy in Metastatic Set ≤3 lines >3 lines |

29(42.6%) 38(55.9%) |

| Number of SG Cycles (median, range) | 7(3-37) |

| G-CSF use with SG | 60(88.2%) |

| Variable | mPFS (months) | 95% CI | p-value | HR(95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

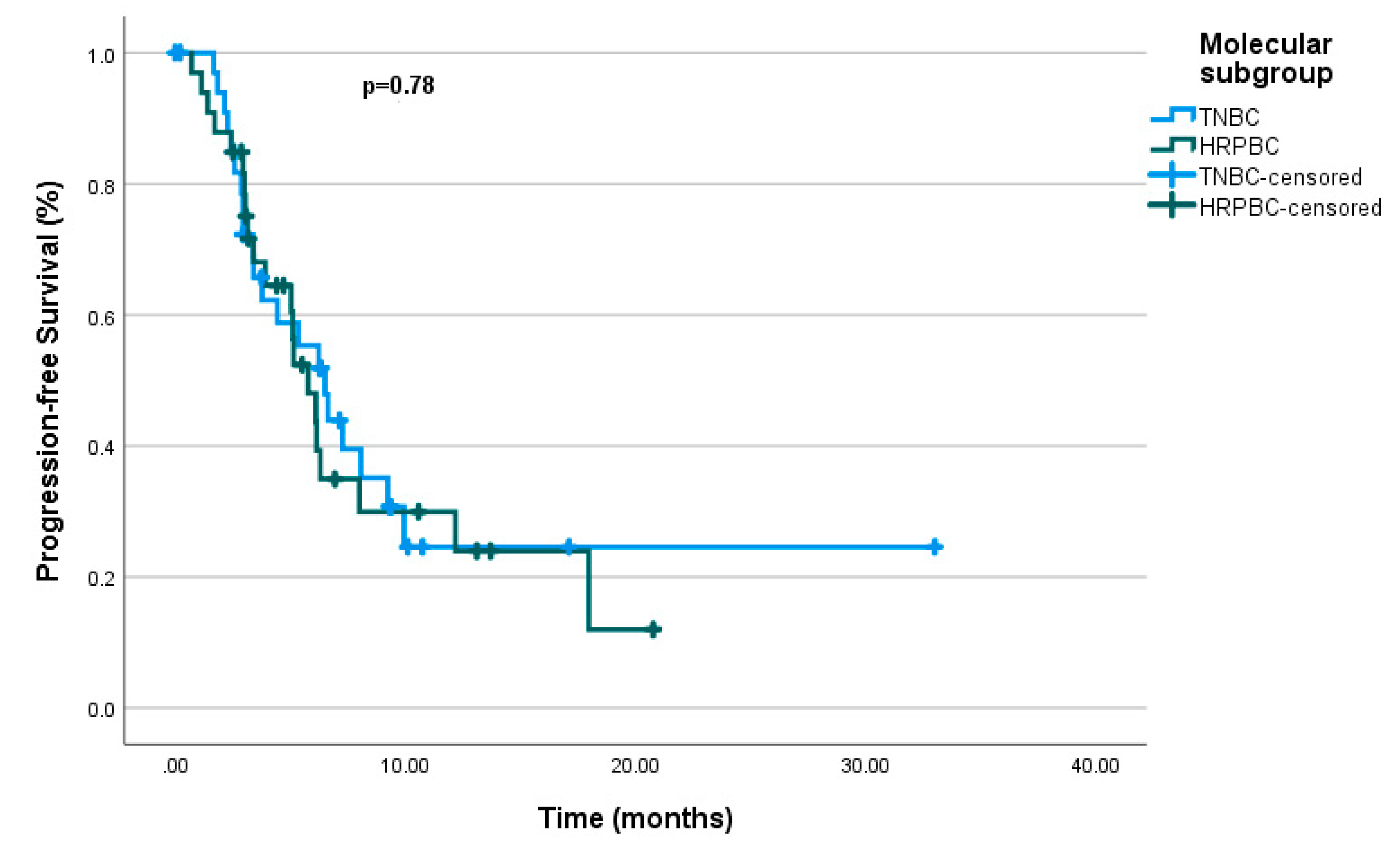

| Molecular subgroup 0.78 | 0.733 (0.384-1.401) |

0.348 | |||

| mTNBC | 6.5 | (4.45 – 8.54) | |||

| mHRPBC | 5.76 | (4.28 – 7.24) | |||

| De novo met | 5.13 | (1.97 – 8.28) | 0.63 | ||

| ECOG PS 0.004 | 1.968 (0.999-3.875) |

0.050 | |||

| ECOG PS-0 | 7.26 | (5.32 – 9.21) | |||

| ECOG PS-1 | 3.76 | (2.26 – 5.27) | |||

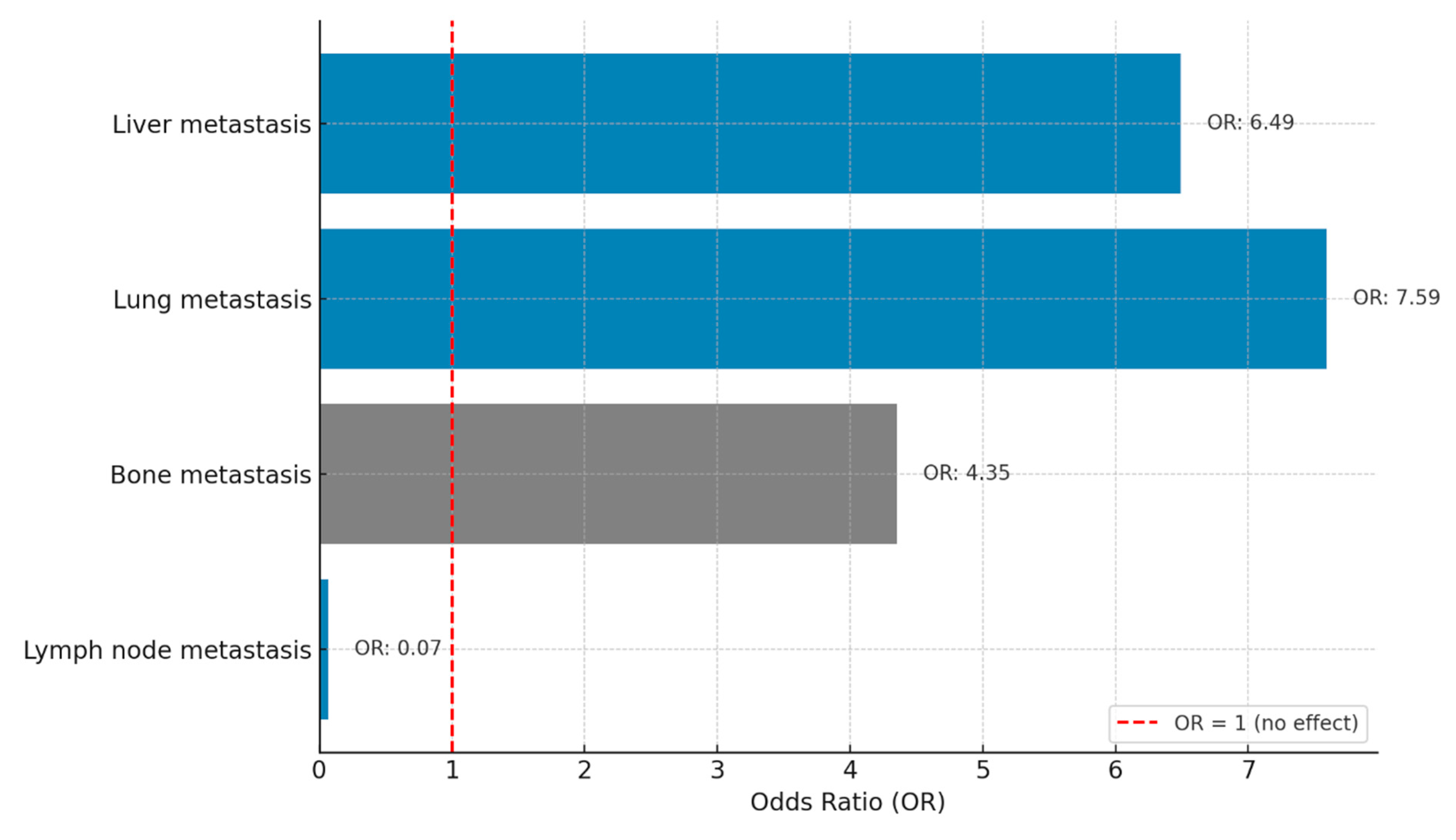

| Metastatic site | |||||

| Liver | 4.43 | (2.74 – 6.12) | 0.002 | 2.046 (1.008-4.151 |

0.047 |

| Lung | 3.9 | (2.30 – 7.76) | 0.088 | ||

| Brain | 5.03 | (2.74 – 6.12) | 0.253 | ||

| Bone | 5.03 | (3.18 – 6.88) | 0.004 | 1.873 (0.896-3.913) |

0.095 |

| Lymph nodes | 6.5 | (4.07 – 8.92) | 0.086 | ||

| Prior ICIs | 6.30 | (2.31 – 10.28) | 0.886 | ||

| Prior chemotherapy | |||||

| Taxane | 6.13 | (4.86 – 7.40) | 0.692 | ||

| Antracycline | 6.13 | (4.79 – 7.47) | 0.717 | ||

| Carboplatin | 6.23 | (4.62 – 7.84) | 0.762 | ||

| Capecitabine | 6.13 | (4.94 – 7.32) | 0.703 | ||

| Local treatment | 6.13 | (4.90 – 7.36) | 0.929 | ||

| No. of chemotherapy lines | |||||

| ≤3 lines chemotherapy | 5.33 | (2.89 – 7.76) | 0.796 | ||

| >3 lines chemotherapy | 6.23 | (5.32 – 7.14) | 0.836 | ||

| Dose reduction due to Toxicity | 3.13 | (0.13 – 6.13) | 0.270 | ||

| G-CSF Use with SG | - | - | 0.097 | ||

| At diagnosis Ki-67≤20 | 6.13 | (4.55 – 7.71) | 0.897 | ||

| At diagnosis Ki-67>20 | 5.76 | (4.27 – 7.25) | 0.897 | ||

| Metastatic setting Ki-67≤20 | 6.13 | (3.46 – 8.80) | 1 | ||

| Metastatic setting Ki-67>20 | 6.23 | (4.67 – 7.79) | 1 | ||

| Variable | mOS (months) | 95% CI | p-value | HR(95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

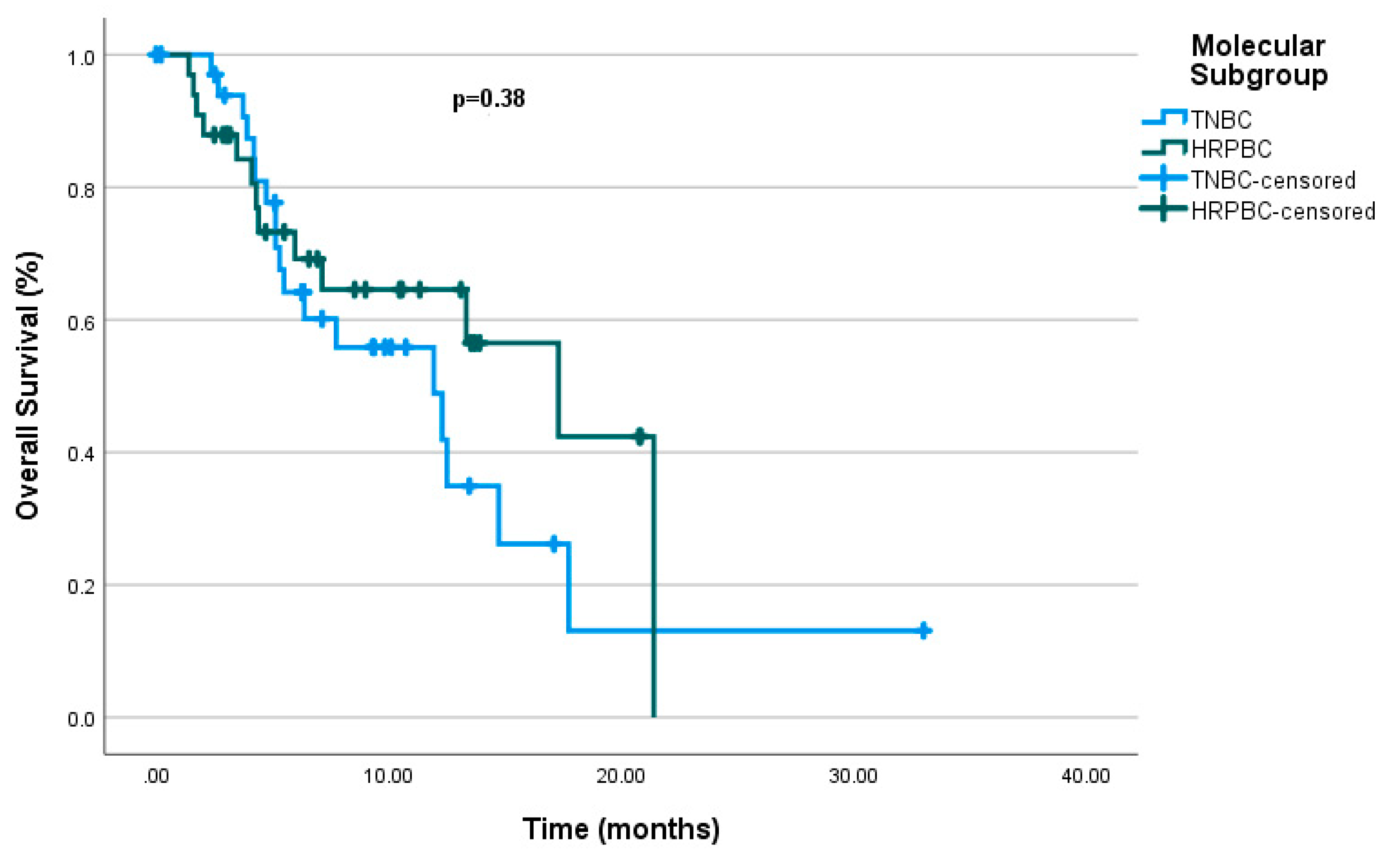

| Molecular subgroup 0.380 | 0.467 (0.221-0.987) |

0.046 | |||

| mTNBC | 11.93 | (5.22 – 18.64) | |||

| mHRPBC | 11.3 | (9.16 – 25.4) | |||

| De novo met | 14.73 | (4.23 – 25.23) | 0.716 | ||

| ECOG-PS 0.178 | |||||

| ECOG-0 | 14.73 | (10.52-18.94) | |||

| ECOG-1 | 13.33 | (2.56-24.10) | |||

| Metastatic site | |||||

| Liver | 5.96 | (2.79-9.14) | 0.001 | 3.15 (1.184-8.383) |

0.022 |

| Lung | 7.13 | (3.65-14.78) | 0.076 | ||

| Brain | 7.13 | (1.07-13.18) | 0.02 | 1.398 (0.609-3.205 |

0.429 |

| Bone | 11.93 | (4.98-18.88) | 0.008 | 2.283 (0.927-5.624) |

0.073 |

| Lymph nodes | 12.5 | (10.72-14.27) | 0.884 | ||

| Prior ICIs | 12.5 | (10.31-14.68) | 0.963 | ||

| Prior chemotherapy | |||||

| Taxane | - | - | 0.293 | ||

| Antracycline | 13.33 | (4.56-22.10) | 0.963 | ||

| Carboplatin | 12.30 | (4.71-19.88) | 0.04 | ||

| Capecitabine | 12.50 | (9.95-15.04) | 0.613 | ||

| Local treatment | 12.50 | (10.75-14.24) | 0.673 | ||

| No. of chemotherapy lines | |||||

| ≤3 lines chemotherapy | 14.73 | (4.99-24.47) | 0.745 | ||

| >3 lines chemotherapy | 12.30 | (5.81-18.79) | 0.724 | ||

| G-CSF use with SG | 13.33 | (6.96-19.69) | 0.724 | ||

| At diagnosis Ki-67 0.460 | |||||

| Ki-67≤ 20% | 14.73 | (4.85-22.63) | |||

| Ki-67>20% | 12.30 | (6.02-18.57) | |||

| Metastatic setting Ki-67 0.184 | |||||

| Ki-67≤20% | 14.73 | (2.81-30.21) | |||

| Ki-67>20% | 12.50 | (10.82 -14.17) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).