1. Introduction

Existing approaches to software protection can generally be classified into two main categories [

1]. The first category focuses on the use of static and dynamic code validation techniques. These methods typically involve embedding objects into the generated executable files, such as through watermarking or software birth marking [

2,

3], which aim to identify and protect the software uniquely. The second category is a more radical approach, which involves utilizing hardware to safeguard the software [

15]. In this approach, the target program is divided into multiple segments that are encrypted and executed on secure coprocessors, providing an additional layer of protection.

Despite these advancements, the risk of attacks against software protection remains prevalent for several key reasons. Firstly, hardware-based protection mechanisms are inherently limited. Hardware architecture defines two distinct execution modes: privileged mode, which allows full system-wide access to resources, and user mode, which has restricted access [

16]. If malicious code or analysis tools manage to execute in privileged mode, no higher-level protection mechanism exists to stop them, rendering the system vulnerable. Secondly, bugs and debugging functions in operating systems are inevitable. Modern OS kernels and third-party device drivers contain millions of lines of code [

6], and nearly all commodity operating systems provide tools that allow the observation of other processes’ address spaces and the attachment of threads for debugging purposes. These capabilities make it exceedingly difficult to prevent someone with malicious intent from exploiting these debugging tools to circumvent software protection mechanisms.

The growing adoption of hardware virtualization technologies, however, has opened up new avenues for addressing these security concerns. Previous efforts have attempted to retrofit trusted execution environments onto commodity systems by isolating malicious code from the system kernel within separate virtual machines (VMs) [

7,

8], or by using active monitors to track and manage security-sensitive behaviors. While these approaches provide some degree of protection, they typically involve significant performance overhead or require intrusive modifications to either the application code or the system kernel, making them difficult to adopt in practice.

In this paper, I propose a transparent, external approach to software protection that overcomes the limitations of previous solutions. Unlike prior methods, my design does not require any modifications to the existing operating system or application code. Even the control flow between the application and the OS kernel remains unchanged, ensuring compatibility with existing software infrastructures. HBSP leverages Intel VT (Virtualization Technology) to create a transparent execution environment, eliminating the need for in-guest components or partial/full system virtualization. Furthermore, my solution incorporates Memory-Hiding technology, which enables the hypervisor to conceal itself in a private memory region, effectively masking its presence from the host OS. This allows the hypervisor to operate transparently while maintaining the ability to monitor and control the execution state of the target application.

2. Design Goals

The rapid advancement of Hardware-Enabled Virtualization (HEV) technologies presents an opportunity to adopt new and more effective methods of software defense [

6]. Virtualization has long been seen as a promising approach to enhancing software security by providing a secure execution environment that can isolate critical components of the system from potential threats. My primary motivation is to provide an additional layer of software protection in environments that are otherwise untrusted, all while ensuring that the solution remains external and transparent to the existing software running on the system. The ease of adoption is also a key consideration, as the solution should not impose significant changes or disruptions to the current system.

In response to these requirements, I have designed and implemented the HBSP framework, a lightweight, flexible, and highly efficient system that leverages HEV technology for software protection. The primary design goals of HBSP can be summarized as follows:

Install/Uninstall on the Fly

HBSP can be installed and uninstalled on the fly without requiring a reboot or significant modification to the existing OS, ensuring seamless integration and minimal disruption. Its non-intrusive operation allows it to function externally, preserving system integrity and user experience. This dynamic approach also simplifies debugging and maintenance, enabling quick updates without system instability. Additionally, by operating outside the host OS, HBSP enhances security, reducing susceptibility to attacks. This flexibility makes it adaptable across diverse system configurations while maintaining performance and reliability.

Flexible Configuration

Another key design goal of HBSP is to offer flexible configuration options, allowing the hypervisor to adapt to various protection strategies. It supports both compile-time and runtime configuration, enabling tailored security settings. The flexibility in configuration also allows Optimized resource management and the system can dynamically allocates resources, ensuring efficiency. Sensitive content is handled separately to minimize performance overhead while maintaining protection. The hypervisor’s configurability allows security to be tailored to specific software needs, making HBSP suitable for diverse protection use cases.

Support for Other HEV Technologies

Currently, HBSP is built to support Intel VT technology, however, I recognize that other hardware virtualization technologies, such as AMD SVM, are widely adopted in the market. To ensure that HBSP remains adaptable and efficient across different platforms, I have designed a modular architecture that abstracts hardware-specific details, enabling seamless extension to new platforms. The abstraction layer minimizes refactoring costs, ensuring platform independence and easy adaptation to future virtualization advancements. This design goal ensures that HBSP can remain compatible with a wide range of hardware platforms, providing users with flexibility in choosing the hardware that best suits their needs.

3. System Implementation

The implementation of HBSP on unmodified commodity OSes presents challenges. This section describes the HBSP architecture, its control flow, and its management of the guest OS. It concludes with an analysis of the Memory-Hiding technology.

3.1. HBSP Architecture

Figure 1 illustrates the HBSP architecture, built upon the BluePill project and adapted for the x86 platform. HBSP consists of three layers: Platform Related Layer, HBSP Interfaces, and the Third Hypervisor Layer.

Platform Related Layer: This layer masks the differences among various HEV technologies and provides unified interfaces for upper layers. Key routines in this layer are listed in

Table 1.

HBSP Interfaces: These interfaces, referred to as Strategy, allow for flexible behavior and resource management. For memory management, the Platform Related Layer calls the appropriate functions based on the chosen strategy.

Third Hypervisor Layer: This layer implements the custom hypervisor logic, built upon HBSP Interfaces. It includes:

Currently, HBSP supports a single guest machine but can be extended to support multiple VMs without affecting the host OS.

3.2. HBSP Control Flow

HBSP functions as a controller between the guest machines and physical hardware. The system can exist in three contexts: guest application (Ring 3), guest kernel (Ring 0/1), and hypervisor (VMM). At any point, a #VMEXIT event triggered by guest instructions will switch control to the hypervisor, which processes the event and then resumes the guest machine.

Figure 2 illustrates the flow of control between the guest machine and the hypervisor when handling #VMEXIT events. For example, when the guest application executes a CPUID instruction, the hypervisor handles the event before transferring control back to the guest.

HBSP also intercepts I/O access to allow the hypervisor to perform additional operations before returning control to the guest machine (see Transition 5, 6).

3.3. Memory-Hiding Technology

Memory-hiding technology ensures the hypervisor remains concealed from the guest OS by modifying the guest’s page table. It clones the current page table and adjusts the mapping of the hypervisor’s virtual address to a special spare page address. This technique prevents the guest OS from accessing the hypervisor, as shown in Figure 4.

The page table is restored to its original state when the system exits the hypervisor context, making the hypervisor invisible again.

Currently, this technology does not support PAE mode, but it is a potential future enhancement.

4. Case Study: Protecting Software with HBSP

In this case study, we explore the effectiveness of HBSP (Hypervisor-Based Software Protection) by introducing a novel hypervisor, SNProtector, designed to protect critical application components such as the serial key validation algorithm and the registration state. The central goal of SNProtector is to ensure the security of the software even if its source code becomes publicly accessible. As long as the SNProtector hypervisor remains active and unaltered, it prevents attackers from modifying or tampering with the application’s core components, maintaining its integrity.

A fundamental challenge in software protection lies in preventing unauthorized modifications to sensitive parts of the software, particularly those associated with serial key validation. Traditional protection schemes often leave these mechanisms vulnerable to attack. To address this, SNProtector leverages a novel technique known as Memory-Hiding Strategy (MHS). MHS works by concealing critical registration-related code and data, making them completely inaccessible to user-space applications or reverse engineering tools. By ensuring that these hidden pages are not referenced within the guest OS’s virtual memory space, this strategy significantly enhances the protection of the software. Even in cases where attackers gain access to the source code, they will be unable to interfere with the protected registration logic as long as the hypervisor remains secure.

4.1. Improvement Over Conventional Serial Key Protection

Traditional serial key protection mechanisms often fail to provide robust security. These conventional methods typically verify the serial key only once during the initial installation or registration process. However, this static approach is highly vulnerable. If an attacker intercepts the registration process, they can either bypass the serial key validation or reverse-engineer the algorithm to generate valid keys, rendering the protection ineffective.

To overcome this limitation, SNProtector introduces a dynamic verification mechanism, which makes it significantly harder for attackers to predict or bypass the protection. This mechanism involves the use of a timer simulation feature that periodically triggers a check on the registration state stored within the hypervisor’s memory space. This dynamic check is performed after a fixed number of Context Register (CR3) switches, a method that ensures the verification process is carried out asynchronously. By periodically triggering the check without relying on any predictable or static pattern, SNProtector reduces the likelihood of an attacker anticipating or intercepting the validation check.

Additionally, while a more advanced solution using VMX Preemption Timer could be employed for more precise control over the timing of these verification events, it is important to note that widespread hardware support for this feature is still limited. As such, SNProtector does not currently implement this feature but remains effective with its existing timer-based mechanism. This approach guarantees that the timer trap, which controls the verification process, cannot be easily intercepted or manipulated by attackers. Even in a multi-tasking environment, such as Windows, where multiple processes are running concurrently, this verification process is sufficiently robust to withstand attempts to subvert the protection.

The security benefits provided by SNProtector over conventional serial key protection mechanisms are evident. By introducing dynamic, unpredictable verification checks and utilizing the Memory-Hiding Strategy to safeguard critical application data, the protection mechanism becomes much more resilient to common attacks such as reverse engineering or tampering with the registration process.

4.2. SNProtector Hypervisor Code

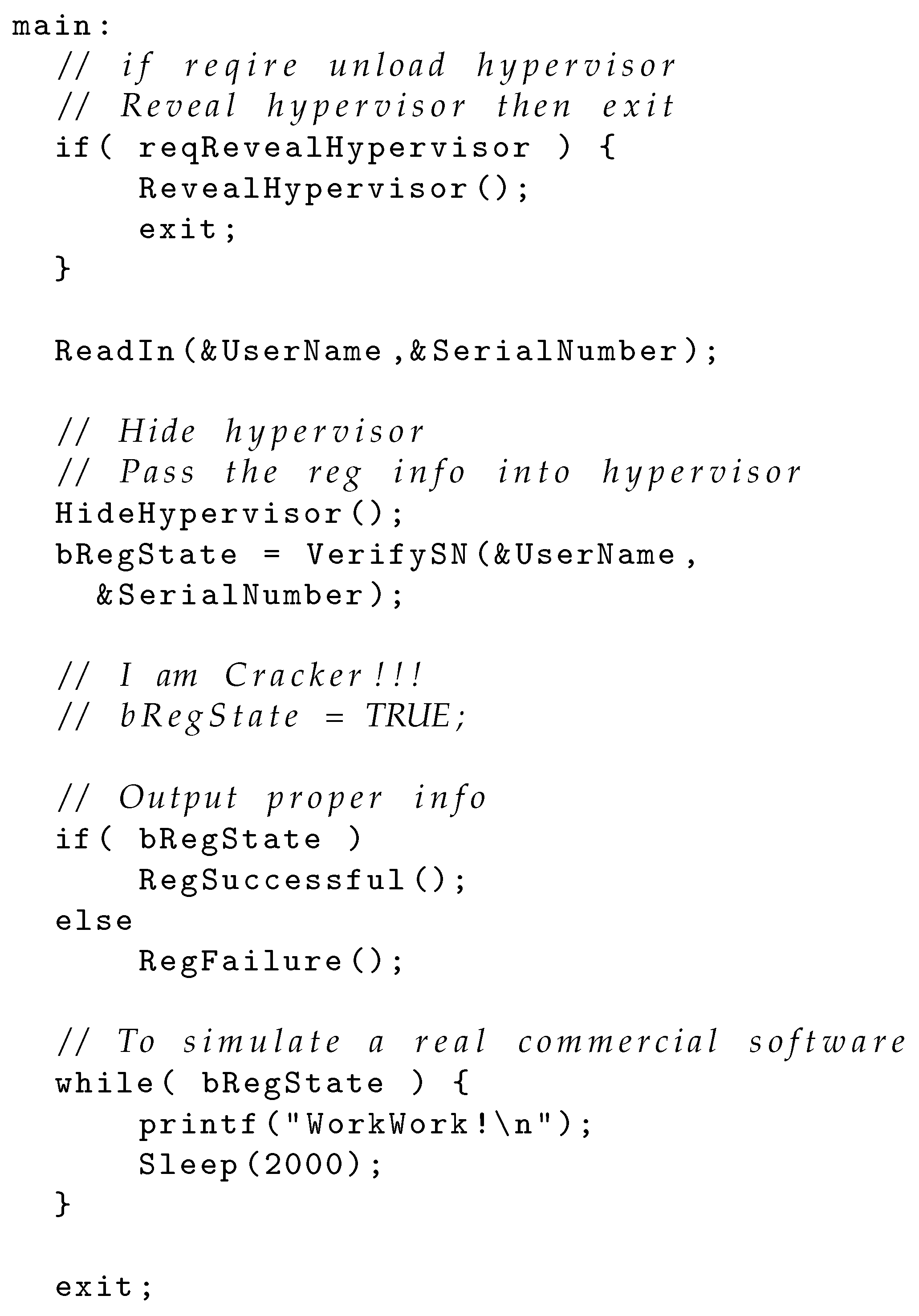

The implementation of the protected software, alongside its interaction with the hypervisor, is outlined in the following pseudocode:

Figure 1 shows the pseudocode for the protected software running under the

SNProtector hypervisor. The key steps include verifying the serial number, hiding the hypervisor, and then passing the registration information to the hypervisor for further validation. The main loop of the software simulates the typical behavior of a commercial application by repeatedly checking and verifying the registration state.

An important detail in this pseudocode is the commented-out line `bRegState = TRUE;`, which simulates a cracking attempt by an attacker. If this line is uncommented, it would immediately bypass the registration check and falsely mark the software as registered. However, the actual registration state in the hypervisor remains unaffected, ensuring that the tampering behavior can be detected.

4.3. Detection of Tampering Behavior

One of the primary advantages of using the SNProtector hypervisor is its ability to detect tampering attempts. In the scenario where the attacker modifies the application’s memory space (e.g., by forcing `bRegState = TRUE`), the hypervisor will detect this action. Since the registration state in the hypervisor memory is hidden and separate from the application’s memory space, the attacker’s attempt to alter the application’s registration state does not affect the value stored in the hypervisor.

As a result, any modification to the application’s behavior is immediately detected as a tampering attempt, as the registration state in the hypervisor remains secure. This makes it significantly harder for attackers to crack or bypass the protection mechanisms.

4.4. Performance Optimization and Overhead

While the protection mechanism introduced by SNProtector is highly effective, it is also designed to minimize the performance overhead typically associated with virtualization-based protections. To achieve this, SNProtector stores the registration state within the application’s memory space in addition to the hypervisor memory space. This dual-storage strategy reduces the need for frequent trap invocations, allowing the application to check the registration state directly without triggering a trap to the hypervisor.

Although handling a virtual machine monitor (VMM) trap incurs an overhead of several hundred clock cycles, this overhead is minimized in practice because the traps are only triggered when necessary. The net result is that the overall performance impact of the protection system is limited, and the software can run with only a small reduction in performance, making it suitable for commercial use. The SNProtector hypervisor provides a robust and efficient solution for protecting software from tampering, even in the case where the application’s source code is publicly available. By leveraging advanced techniques like memory hiding and dynamic registration state verification, SNProtector ensures that the software remains protected against reverse engineering and cracking attempts. The approach successfully circumvents the weaknesses of traditional serial key protection mechanisms, while also providing an efficient and scalable solution with minimal performance overhead.

5. Experiments and Results

In order to evaluate the performance and effectiveness of the SNProtector, I conducted a series of experiments using a standard desktop setup. The experiments were performed on a machine with an Intel Core2 Duo E6320 processor and 2GB of RAM. The testbed was set up with Windows XP SP3 as the guest operating system, and an SNProtector was installed across both processor cores to observe its impact on system performance and the efficacy of its protection mechanism.

5.1. Microbenchmarks

To assess the overhead caused by intercepting instructions in the hypervisor, I conducted micro benchmarking tests.

Table 2 presents the clock cycles required for executing the CPUID instruction before and after the installation of SNProtector. The CPUID instruction was chosen as a benchmarking metric as it is frequently used in system profiling and because of its sensitivity to hypervisor intervention. The test hardware was selected to reflect real-world deployment scenarios, and to maintain compatibility with older OS versions.

As shown in

Table 2, the execution cycle for the CPUID instruction increased significantly after SNProtector was loaded. Specifically, the number of clock cycles required to handle this instruction jumped from 218 to 2573, reflecting the overhead introduced by the hypervisor in managing instruction interceptions and the VMCS region. This overhead is expected, as trapping to the hypervisor and handling these traps involves additional processing by the system.

5.2. Application Benchmarks

While microbenchmarks show a substantial performance degradation for individual instructions (about 11 times more cycles), the impact of SNProtector on real-world applications is much less pronounced. I tested the performance of applications running under SNProtector by measuring the total program runtime in a series of benchmarks.

5.3. Web Server Experiment

In addition to CPU-bound benchmarks, I also conducted a web server performance test to measure the throughput in terms of bytes per second (Bps). For this experiment, I used the default configuration of Apache 2.2.11 on a Windows XP SP3 system. The test website was configured with 10 randomly sized files, ranging from 1KB to 8MB in size. A remote host was used to generate HTTP requests to fetch all the files with 100 concurrent connections, simulating typical usage patterns for a web server.

The results of this web server test revealed that the overhead introduced by running SNProtector was minimal. The throughput reduction due to SNProtector was measured at just 0.55%, demonstrating that SNProtector has little to no effect on the performance of a heavily concurrent system like a web server.

5.4. Overall Performance Impact

When I combine the results from the SPEC CPU2006 benchmarks and the web server experiment, the average overhead of SNProtector on the guest operating system was found to be just 0.25%. This value is quite low, indicating that the overall impact on system performance is minimal, thus making it suitable for real time applications such as financial systems and industrial software. Additionally, the hypervisor can operate without modifying the OS which makes it ideal for environments where software integrity must be maintained, such as cloud computing and embedded systems.

6. Related Work

The development of high-assurance execution environments has been an ongoing challenge, especially in securing sensitive applications while maintaining performance. A key aspect of this field involves intercepting guest operating system exceptions and interrupts, which is achieved by utilizing Hypervisor-Based Software Protection (HBSP). One of the notable systems in this space is

Overshadow [

5]. Overshadow implements a unique approach where an additional layer of address translation is added, providing distinct views of a sensitive application’s address space based on the current context. This is accomplished without affecting the underlying operating system (OS) or legacy protected applications. More specifically, even hardware, the kernel, and other programs can only access encrypted content from the protected application’s virtual space.

When comparing SNProtector with Overshadow, the performance of SNProtector stands out as superior, especially in terms of instruction interception. While both approaches aim to provide high-security environments, SNProtector is designed with performance optimization in mind, offering significantly higher execution speeds when intercepting instructions.

In addition to

Overshadow, many other systems have been developed to create high-assurance execution environments by running sensitive applications in isolated virtual machines (VMs). One such system is

Proxos [

9], which utilizes trusted VMs to execute protected applications. This approach allows resources from untrusted VMs to be used securely by the protected VM. Similarly,

iKernel [

10] enhances the reliability and security of commodity operating systems by isolating potentially buggy or malicious device drivers in separate VMs. The isolation of untrusted components from the OS and the applications helps mitigate the risk of malicious activities.

Another approach used in partitioning system calls and separating privileges is explored in

Separation of Privilege [

11]. This technique divides the system call interface to allow secure execution of code in distinct VMs, ensuring that critical tasks can run without interference from less trusted processes. Hypervisor-based monitoring solutions, as outlined in [

9], are also used to monitor for malicious behaviors, particularly when it comes to handling sensitive instructions. While these systems offer varying degrees of isolation and security, they often require modifications to both the kernel and the application code. This contrasts with my approach, which provides a higher level of performance and has a reduced impact on legacy OS kernels due to its optimized design.

Proxos [

9], for instance, requires significant changes to both the application and kernel code, which may present compatibility issues with existing software. Other systems, such as Igor Burdonov’s work [

11],

Ether [

12], and

Lares [

14], focus on security and performance, but they tend to incur high performance penalties. Specifically, these systems suffer from considerable overhead when applying their security measures, making them less suitable for environments where performance is critical. In contrast,

iKernel [

10] has not published experimental statistics on temporal overhead, and its real-world applicability remains uncertain.

Moreover, hardware-based solutions, such as Intel’s

Trusted Execution Technology (TXT) [

13], offer an alternative to software-based solutions. Intel TXT provides an isolated execution environment for software, ensuring that even unauthorized software is unable to observe or interfere with the protected execution environment. This technology focuses on securing both input and storage channels, offering a high level of data security. While Intel TXT is a powerful complement to memory-hiding techniques, it is only available on specific hardware platforms, limiting its universality.

In comparison, the Memory-Hiding technology proposed in SNProtector is more widely applicable and does not require specialized hardware. It enhances security by intercepting sensitive instructions and providing isolation without the performance degradation commonly seen in other systems. SNProtector also excels in terms of its efficiency, allowing for higher performance while still maintaining a strong level of protection against tampering.

Overall, while several systems have been developed to secure applications through virtualization, trusted execution environments, and hypervisor-based protection, SNProtector differentiates itself by offering a higher-performance solution with minimal impact on legacy systems. my approach provides an optimized design that balances both security and performance, making it a promising alternative to existing methods that often compromise on one of these factors. A prototype implementation demonstrated HBSP’s effectiveness in protecting software while maintaining minimal performance overhead (0.25%), making it a practical and scalable security solution. Future enhancements will focus on dynamic memory encryption and advanced behavioral analysis to strengthen HBSP’s resilience against evolving security threats. This work establishes HBSP as a promising, high-performance approach to hypervisor-based software protection. operating system (OS), hardware, or even software.

7. Conclusion

In this paper, I have introduced HBSP (Hypervisor-Based Software Protection), hat enables the transparent interception of guest OS actions without requiring modifications to the existing operating system (OS), hardware, or even software. The key feature of this design lies in its ability to operate under the guest OS, running as an external hypervisor that can intercept and manage sensitive operations, thus providing a robust layer of security without interfering with the normal functioning of the system. Future enhancements will focus on dynamic memory encryption to further protect sensitive data, advanced behavioral analysis using machine learning to detect sophisticated attacks, and hardware-assisted protection by leveraging technologies like Intel SGX and AMD SEV while also adding multi-layer protection mechanisms, and expanding cross-platform compatibility to Linux and macOS, while conducting real-world deployments will further refine HBSP’s robustness.

References

- Zambreno, J.; Honbo, D.; Choudhary, A.; Simha, R.; Narahari, B. High-Performance Software Protection Using Reconfigurable Architectures. Proceedings of the IEEE 2006, 94, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Sun, X.; Sun, G.; Yang, Y. A Combined Static and Dynamic Software Birthmark Based on Component Dependence Graph. Intelligent Information Hiding and Multimedia Signal Processing, 2008. IIHMSP ’08 International Conference, 15-17 Aug. 2008; pp. 1416–1421. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.; Lim, H.-i; Choi, S.; Han, T. A Static Java Birthmark Based on Operand Stack Behaviors. Information Security and Assurance, 2008. ISA 2008. International Conference, 24-26 April 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Invisible Things Lab. BluePill Project. Available online: http://www.bluepillproject.org/stuff/nbp-0.32-public.zip.

- Chen, X.; Tal Garfinkel, E.; Lewis, C.; Subrahmanyam, P.; Waldspurger, C.A.; Boneh, D.; Dwoskin, J.; Ports, D.R.K. Overshadow: A Virtualization-Based Approach to Retrofitting Protection in Commodity Operating Systems. ASPLOS’08, March 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Petroni, N.L.; Hicks, P.M. Automated detection of persistent kernel control-flow attacks. In Proceedings of the 14th Computer and communications security, Alexandria, Virginia, USA, Oct. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Waldspurger, C.A. Memory resource management in VMware ESX server. In Proceedings of the Fifth Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation, December 2002; pp. 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, M.; Lim, B.H.; Hutchins, G. Fast Transparent Migration for Virtual Machines. In Proceedings of the USENIX Annual Technical Conference, April 2005; pp. 391–394. [Google Scholar]

- Ta-Min, R.; Litty, L.; Lie, D. Splitting Interfaces: Making Trust Between Applications and Operating Systems Configurable. In Proceedings of the Seventh Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation, November 2006; pp. 279–292. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, P.L.; Chan, E.M.; Farivar, P.R.; Mallick, N.; Carlyle, J.C.; David, F.M.; Campbell, R.H. iKernel: Isolating Buggy and Malicious Device Drivers Using Hardware Virtualization Support. In Proceedings of the Third IEEE International Symposium on Dependable, Autonomic and Secure Computing, September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Burdonov, I.; Kosachev, A.; Iakovenko, P. Virtualization-based separation of privilege: working with sensitive data in untrusted environment. In Proceedings of the 1st EuroSys Workshop on Virtualization Technology for Dependable Systems, Mar. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dinaburg, A.; Royal, P.; Sharif, M.; Lee, W. Ether: malware analysis via hardware virtualization extensions. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM conference on Computer and communications security, Oct. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Intel. Intel Trusted Execution Technology Architecture Overview; September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, B.D.; Carbone, M.; Sharif, M.; Lee, W. Lares: An Architecture for Secure Active Monitoring Using Virtualization. Security and Privacy, 2008. SP 2008. IEEE Symposium, 18-22 May 2008; pp. 233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Gao, L.; Zhang, Y. Improving Memory Encryption Performance in Secure Processors. IEEE Trans. Computers (TC) 2005, 56, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russinovich, M.E.; Solomon, D.A. Microsoft Windows Internals, Fourth Edition: Microsoft Windows Server 2003, Windows XP, and Windows 2000; Microsoft Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).