1. Introduction

Bluetongue virus (BTV) produces a debilitating ruminant disease of mandatory notification to the world organization for animal health (WOAH) that leads to significant economic losses through loss of productivity. The disease is characterized by pyrexia, apathy, loss of appetite, and edemas of the face and lips. In the most severe cases, it generates respiratory distress and hemorrhages that can result in the characteristic cyanotic tongue that gives its name to the disease, and even lead to the death of animals [

1]. It can also produce abortions in pregnant ewes, which further contribute to the loss of productivity [

2]. An estimated 3 billion dollars are yearly lost to the industry as a result of BTV infections [

3]. Typically sheep are more prone to develop severe clinical signs than other ruminants but some serotypes can also severely affect cattle, such as in the case of the 2006 BTV-8 outbreak in Europe [

4].

BTV is the prototypical member of the genus

Orbivirus, family

Sedoreoviridae, that includes other relevant pathogens in animal health such as african horse sickness virus (AHSV) or epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus (EHDV) [

5]. It possesses a genome that consists of 10 segments that encodes for 7 structural proteins (named VP1 to VP7) and 4-5 non-structural proteins (named NS1 to NS5) [

6,

7]. BTV is principally transmitted by the bite of infected Culicoides spp. to the mammalian host [

2,

8]. Viremia is characteristically long in BTV infection, which probably facilitates the transmission of the virus back to the Culicoides vector [

9,

10]. Global warming, which has increased the habitat range of traditional competent vectors, as well as the likely adaptation of the virus to Culicoides species present in more temperate regions has led to the establishment of BTV in Europe [

11]. To further complicate disease control, BTV also possesses multiple serotypes (at least 29 have been described to date) that offer little heterologous cross-serotype protection. Although current inactivated vaccines are effective for homologous serotype protection, they only offer little protection against a different serotype. These vaccines cannot differentiate between infected and vaccinated animals, the so-called DIVA approach. Vaccines based on the expression of BTV subunits have the potential to be DIVA vaccines, as they only express parts of the virus. Much effort has been made to develop these subunit vaccines against BTV, either through the expression of recombinant BTV proteins or by expressing the coding sequences of these subunits in recombinant viral vaccine platforms [

12]. Some of these approaches have also shown some promising protection results as multiserotype vaccines [

13,

14,

15]. This is highly sought after in the field, as production of a single vaccine formulation could be sufficient to protect against BTV in regions in which multiple serotypes circulate.

Protection against BTV infections necessitates of a humoral and a cellular response. Early depletion and transfer studies demonstrated that solely humoral or cellular responses only offered partial protection against infection [

16,

17]. Vaccination should therefore aim at eliciting both arms of the adaptive immune response. Cellular immunity is particularly relevant in the case of BTV infections as it can be targeted by subunit vaccines to conserved antigens between serotypes such as VP7 and NS1 [

18,

19]. Indeed, we have found that expressing VP7 in a recombinant replication-defective adenovirus platform could confer BTV protection in sheep in the absence of neutralizing antibody [

20], while cellular responses to an NS1 epitope can also be protective in a murine model [

21]. In most cases, cellular protection is unlikely to confer sterile protection against BTV, and potent humoral antigens such as VP2, which contains the majority of neutralizing determinants, should be included in vaccines.

In the present work, we evaluated the immunogenicity and protective potential of a DNA plasmid platform (pPAL) that lacks resistance gene for selection and that the European Medicines Agency recently approved for leishmania vaccination in dogs [

22]. Expression of SARS-Cov2 spike and nucleoprotein in this DNA platform was also an effective vaccine in animal models against virulent challenge with SARS-Cov2 [

23]. As a proof of principle, we chose to express the highly conserved antigen VP7 and the main determinants for neutralizing antibodies VP2 from BTV-8 in this DNA expression system. We used a prime-boost regime either with two inoculations of the pPAL plasmids, or with a pPAL plasmid priming followed by a recombinant replication-defective adenovirus booster that encoded the same viral antigens. We evaluated the responses to vaccination and virulent BTV-8 challenge using only VP7 or VP2 as antigens, or with a combination of both antigens.

4. Discussion

In the present work, we show that delivery of BTV antigens VP7 and VP2 through a DNA priming followed by an adenovirus booster can fully protect mice against virulent BTV challenge. Heterologous prime-boost strategies have been used in the past and shown promising results in protecting against BTV [

14,

15,

31,

32,

33]. BTV antigen delivery through DNA prime followed by modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) booster can protect mice from BTV lethal challenge [

14,

31]. Similarly, antigen delivery through avian reovirus microspheres followed by MVA booster was also successful for protection in murine models [

32]. Heterologous strategies involving 2 viral vectors (ChAdOx1 vector and MVA) have also shown some efficacy in mice and sheep [

15,

33]. Our strategy nonetheless makes use of two delivery systems (pPAL and adenovirus platforms) that have been approved as vaccine by regulatory agencies. We also present an exhaustive assessment of the immune response generated by these heterologous strategies as well as their correlation with protection. We found that in the murine model, induction of anti-BTV CD8

+ T cells is crucial as this parameter showed the highest correlation coefficient with protection. We also found that neutralizing antibody induction correlated strongly with protection. Vaccination should therefore aim at stimulating both immune parameters, and vaccine potency is likely to rely on both parameters.

In support of this, we found that viremia was better controlled in groups that received VP2 than in the group that only received VP7. This is likely due to the presence of anti-VP2 neutralizing antibodies to BTV in these animals that quickly limit replication, whereas anti-VP7 antibodies cannot effectively neutralize BTV infection. We nonetheless detected low NAb titers in one mouse immunized solely with VP7 following adenovirus boost. Although antibodies to BTV-VP7 inner core protein are not thought to produce neutralization, reports exist of neutralizing determinants on the VP6 inner core proteins of rotavirus [

34,

35], another member of the

Sedoreoviridae family. Inner core proteins in

Sedoreoviridae are mainly exposed intracellularly during infection [

6], thus antibodies are unlikely to “classically” neutralized infection by preventing virus entry. It is more probable that neutralization against VP7 determinants would occur through intracellular mechanisms mediated for instance by antibody binding to the intracellular IgG receptor TRIM21 [

36]. The observation that some neutralizing antibodies can be elicited against BTV-VP7 suggests that neutralizing determinant could also exist on this conserved BTV protein. Further work will be required to elucidate this observation.

Another important aspect that is critical for BTV protection is the choice of antigen to include in the vaccine formulation. Our rationale was to focus on structural proteins as antigens, since they are present on the viral particles and this should allow for quicker recognition and elimination of virus and infected cells when compared to non-structural proteins, which require viral replication to occur for expression to begin. We chose VP7 and VP2 as antigens, as they are abundant proteins on the virion (260 and 60 copies, respectively [

6]) and therefore their availability for presentation to the immune system as viral antigen should be high during infection. Moreover, they are also known to contain cellular and humoral determinants [

19,

37]. We have found that VP7 could represent the basis for cross-serotype protection and that this is likely due to cellular immunity since we detected protection in mice and sheep in the absence of neutralizing antibodies [

13,

20]. Other studies also confirmed that induction of immunity to VP7 participate in protection [

31,

32]. The non-structural proteins NS1 and NS2 have also been used as immunogens in other studies to trigger cellular immunity. These non-structural proteins are conserved between serotypes and can therefore be used to elicit serotype cross-reactive T cells [

15,

18,

21]. Vaccination with these antigens can lead to protection in animal models, but protection was limited in sheep, possibly because only targeting these antigens is insufficient to control viral replication in the early stages of infection [

15,

33]. As previously discussed, VP2 improved protection against virulent BTV challenge in our experiment, and this is likely due to the induction of antibodies that can rapidly neutralize BTV infection. A recent study has corroborated this, showing that inclusion of VP2 in a recombinant MVA with NS1 and a truncated NS2 could offer protection in sheep against BTV challenge, whereas concomitant expression of VP7 with NS1 and the truncated NS2 only offered partial protection [

38]. This further indicates that the inclusion of cellular and humoral immune targets of BTV is a requisite to design effective BTV vaccines.

Curiously, we observed that homologous pPAL immunization could potentially elicit anti-BTV cytotoxic CD107a

+ CD4

+ T cells. We have previously observed a similar phenotype using pPAL vaccination against SARS-CoV2 [

23]. DNA vaccines are known to potentiate cellular responses [

39], although this phenotype has not been described before to the best of our knowledge. Whether this observation is specific to the pPAL expression system or it can be extended to other DNA vaccine platforms remains to be determined. The exact contribution of these cytotoxic CD4

+ T cells to infection resolution is not fully elucidated [

40]. Some studies indicate that they participate in virus clearance [

41,

42], however their presence could also lead to the loss of B cell germinal center observed in patients that succumbed to SARS-Cov2 infection [

43]. Our data nonetheless indicate that BTV is better controlled in this murine model by CD8

+ T cell activation, and as such vaccination should aim at triggering this cell population.

Although our data highlights the importance of cellular immunity for protection against BTV in IFNAR

(-/-) mice, the immune mechanisms that lead to protection could be different in the natural host. Indeed, a recent study has indicated that CD8

+ T cells could be detrimental for bluetongue disease outcome in sheep possibly through immune-mediated pathogenicity [

44]. We have however found in several experimental infections with BTV in sheep that CD8

+ T cells expand at day 10-15pi [

27,

45,

46] and this typically coincides with reduced viremia, which points at a role for these T cells in the removal of BTV-infected cells. We nonetheless detected that during the peak of viral replication T cell responses are acutely suppressed and this coincided with the overexpression of genes and molecules involved in the immunoregulatory PD1/PD-L1 pathway [

27]. In this context, and given the putative role of CD8

+ T cells in bluetongue immunopathology, it could be hypothesized that in the natural host these T cells would become activated during acute viral infection to clear infected cells but their prolonged activation could lead to immunopathology, hence the triggering of immune checkpoints to tightly regulate the activity of the population.

It is also important to note that, although IFNAR

(-/-) mice are excellent models to evaluate vaccine candidates against BTV, these mice are partially immunocompromised. As such, this model has some limitations when evaluating immune responses to vaccines [

47,

48]. We found that IFN-γ production was quite limited in these experiments when compared to previous work with immunocompetent transgenic mice susceptible to SARS-CoV2 [

23]. This could be due to the IFN deficiency of this murine model that could result in impaired IFN type II responses. In comparison, TNF-α responses appear enhanced when contrasted to previous studies in fully immunocompetent mice, which suggest that IFNAR

(-/-) mice may compensate their IFN-I deficiency by promoting pro-inflammatory cytokines production such as TNF-α. This is an important consideration when using this model to evaluate immune responses to vaccine candidates, given the importance of IFN-I in modulating adaptive immunity [

49]. As a result, IFN-I deficiency in these animals could limit and bias the adaptive immunity we observe. In spite of this, we found that IFNAR

(-/-) mice mounted T cell responses to a similar repertoire of VP7 epitopes than wild-type mice with the same genetic background [

19], and as many vaccination studies attest immune responses in these mice are sufficient to control viral replication. It would be nonetheless interesting to perform in future work a parallel vaccination study with immunocompetent mice to further evaluate the capacity of the IFNAR

(-/-) murine model to mount fully effective adaptive immune responses. These studies could help in the interpretation of immune results in IFNAR

(-/-) mice.

Finally, our data show that heterologous prime-boost improves the titers of neutralizing antibodies, when compared to the homologous DNA vaccination strategy. We also found in a previous study that homologous adenovirus expressing VP2 elicited minimal titers of neutralizing antibodies [

13]. Although this could be due to the antigen, as we have been able to obtain adequate neutralizing antibody titers to other viral antigens such as the hemagglutinin from peste des petits ruminants virus with recombinant adenovirus vaccines when using homologous prime-boost vaccination [

50]. Adequate neutralizing antibody titers against SARS-CoV2 can also be reached with homologous recombinant adenovirus vaccines or with pPAL [

23,

51]. Nonetheless, one of the main advantages of heterologous prime-boost vaccination over homologous vaccination is that it improves neutralization antibody generation. For instance, in immunocompromised patients, adenovirus prime followed by mRNA vaccine boost against COVID’19 was shown to improve neutralizing antibody titers [

52]. Similarly, we found that DNA prime-adenovirus boost with BTV antigens improved cellular responses when compared to homologous DNA vaccination. Adenovirus-based VP7 delivery improved the polyfunctionality of anti-BTV T cells, a feature associated to more effective immune responses to pathogens [

53]. Evidence exists that heterologous prime-boost strategies also enhance cellular immunity by increasing the number of responding cells and promoting effector memory differentiation [

52,

54,

55,

56]. Heterologous prime-boost strategies can therefore be advantageous as they potentiate both arms of adaptive immunity. Although in the context of veterinary medicine the licensing of two vaccine reagents could be costly, it could still be a useful strategy to explore to produce BTV vaccines that induce long-lasting immunity, particularly if they allow for multiserotype protection.

We herein report a promising strategy for BTV vaccination that consists in a heterologous prime boost strategy with DNA and adenovirus vectors that express VP7 and VP2 proteins from BTV. Expression of both antigens induced potent cellular and humoral immunity that led to protection. Importantly, we could not detect viremia in the vaccinated group that received both antigens, which indicates that this vaccine could produce sterile protection. It will be important in future studies to evaluate the protective efficacy of this heterologous prime-boost regime in a natural host of the disease. Heterologous DNA-adenovirus prime-boost vaccinations are therefore a promising strategy to explore for the development of DIVA BTV vaccines.

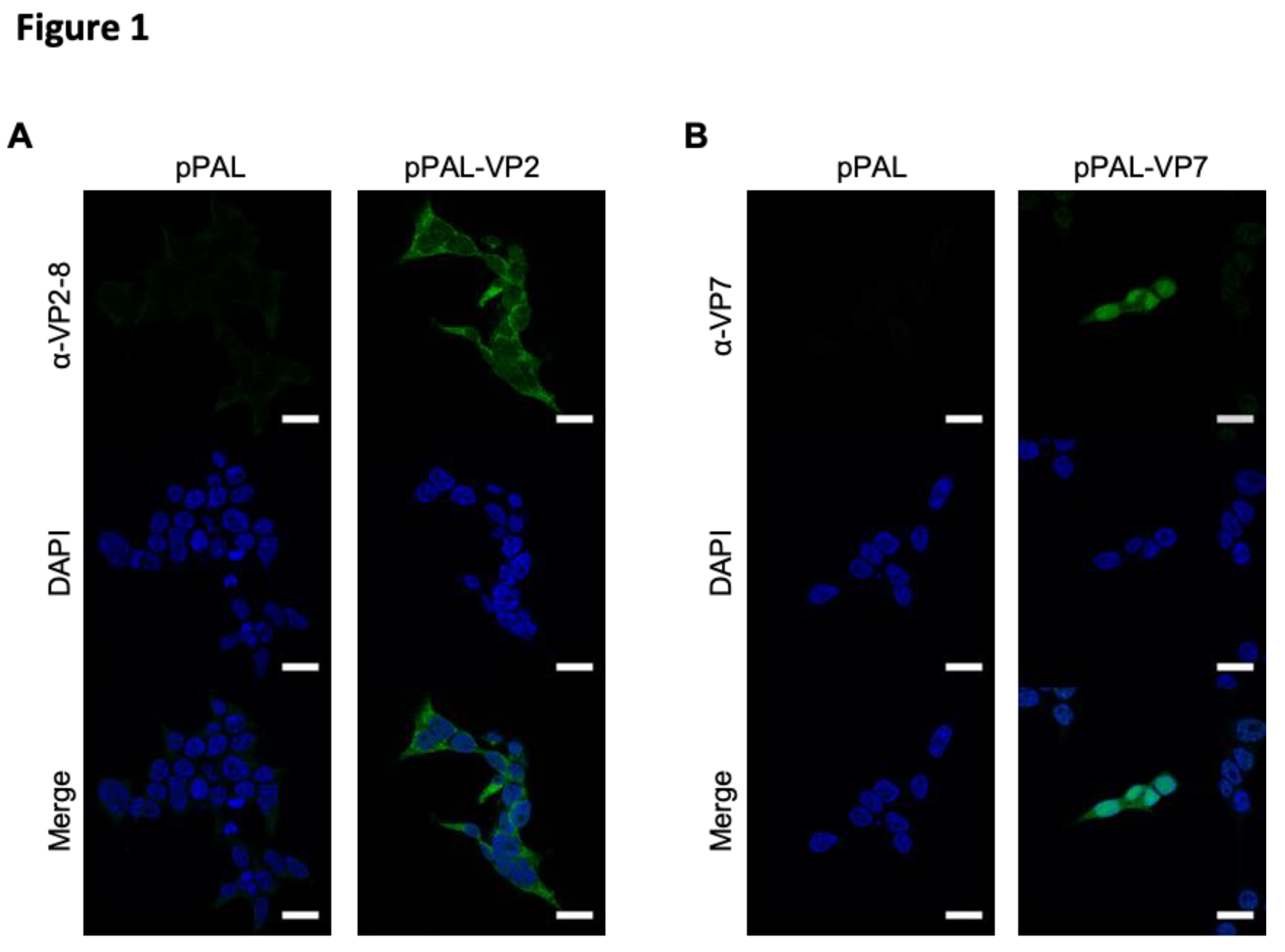

Figure 1.

Immunofluorescence studies confirmed VP2 and VP7 expression by pPAL plasmids. HEK-293 cells were transfected with pPAL-VP2 pPAL-VP7, or pPAL-empty as control. After 48h, cells were fixed permeabilized and stained to detect the expression of VP2-8 or VP7, before counterstaining nucleic acids with DAPI. (A) VP2-8 expression in pPAL-empty or pPAL-VP2-8 transfected HEK293 cells. (B) VP7 expression in pPAL-empty or pPAL-VP7 transfected HEK293 cells.

Figure 1.

Immunofluorescence studies confirmed VP2 and VP7 expression by pPAL plasmids. HEK-293 cells were transfected with pPAL-VP2 pPAL-VP7, or pPAL-empty as control. After 48h, cells were fixed permeabilized and stained to detect the expression of VP2-8 or VP7, before counterstaining nucleic acids with DAPI. (A) VP2-8 expression in pPAL-empty or pPAL-VP2-8 transfected HEK293 cells. (B) VP7 expression in pPAL-empty or pPAL-VP7 transfected HEK293 cells.

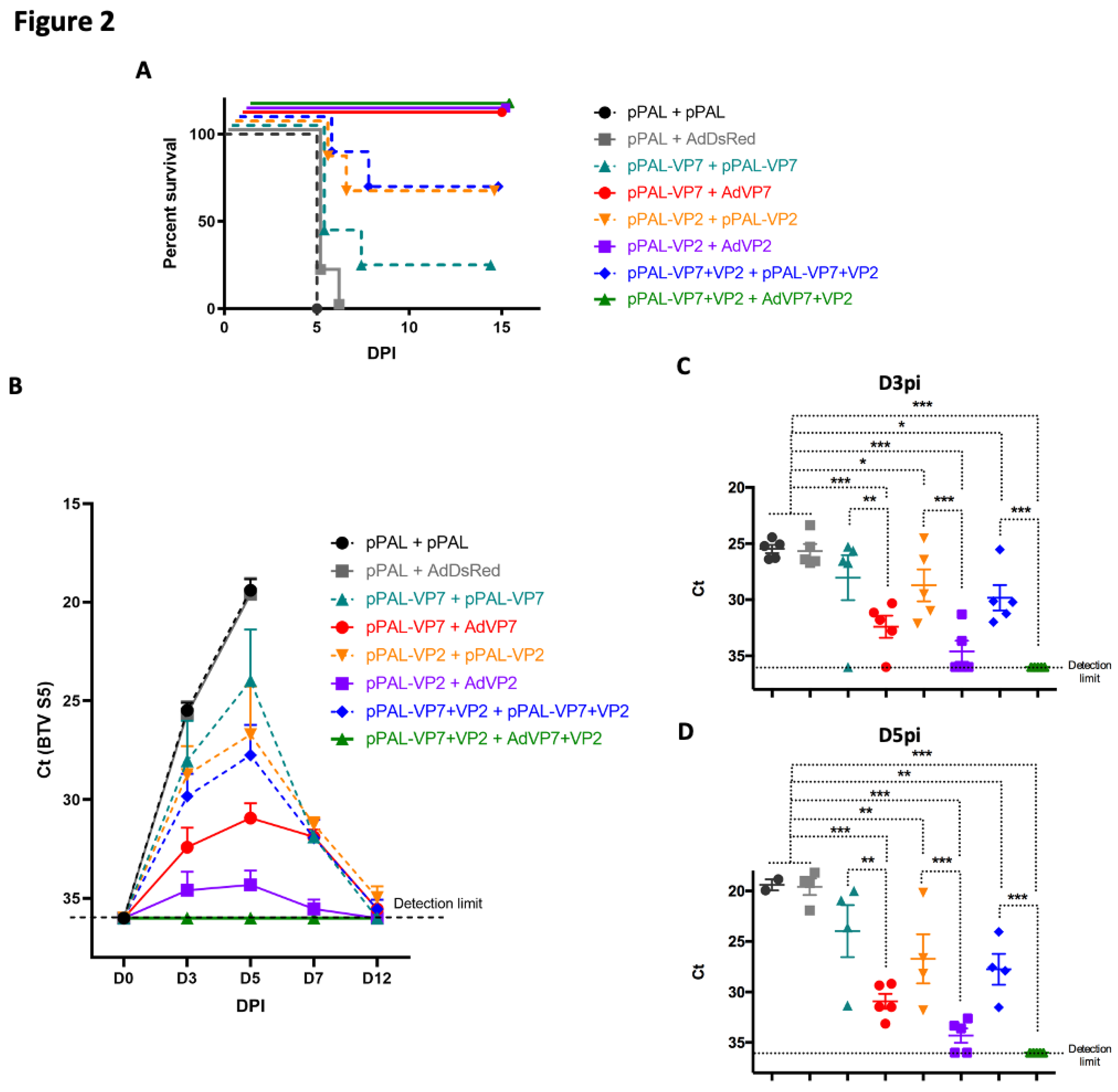

Figure 2.

pPAL and adenovirus vaccination protects against BTV-8 challenge and controls viral replication. (A) IFNAR(-/-) mice were immunized with VP7 and/or VP2 delivered as homologous pPAL or heterologous pPAL+adenovirus immunizations. Mice were challenged with 1000pfu BTV-8, and monitored daily for appearance of clinical signs of disease. Survival curve for each vaccinated group is shown. (B-D) Blood samples were obtained from infected mice at day 0 (pre-challenge) and at days 3, 5, 7 and 12 post-infection (DPI), and RNA extracted. RT-qPCR was performed to detect BTV RNA presence in these samples. (B) Ct mean values for BTV segment 5 fragment (BTV S5) are plotted for all timepoints assessed for each treatment group. Ct individual values at (C) day 3 post-infection (D3PI) and (D) day 5pi (D5PI) are plotted for each vaccinated group. * p<0.05; **p<0.01; *** p<0.001 One-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD post-test. Detection limit of RT-qPCR for BTV S5 fragment (Ct<36) is indicated.

Figure 2.

pPAL and adenovirus vaccination protects against BTV-8 challenge and controls viral replication. (A) IFNAR(-/-) mice were immunized with VP7 and/or VP2 delivered as homologous pPAL or heterologous pPAL+adenovirus immunizations. Mice were challenged with 1000pfu BTV-8, and monitored daily for appearance of clinical signs of disease. Survival curve for each vaccinated group is shown. (B-D) Blood samples were obtained from infected mice at day 0 (pre-challenge) and at days 3, 5, 7 and 12 post-infection (DPI), and RNA extracted. RT-qPCR was performed to detect BTV RNA presence in these samples. (B) Ct mean values for BTV segment 5 fragment (BTV S5) are plotted for all timepoints assessed for each treatment group. Ct individual values at (C) day 3 post-infection (D3PI) and (D) day 5pi (D5PI) are plotted for each vaccinated group. * p<0.05; **p<0.01; *** p<0.001 One-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD post-test. Detection limit of RT-qPCR for BTV S5 fragment (Ct<36) is indicated.

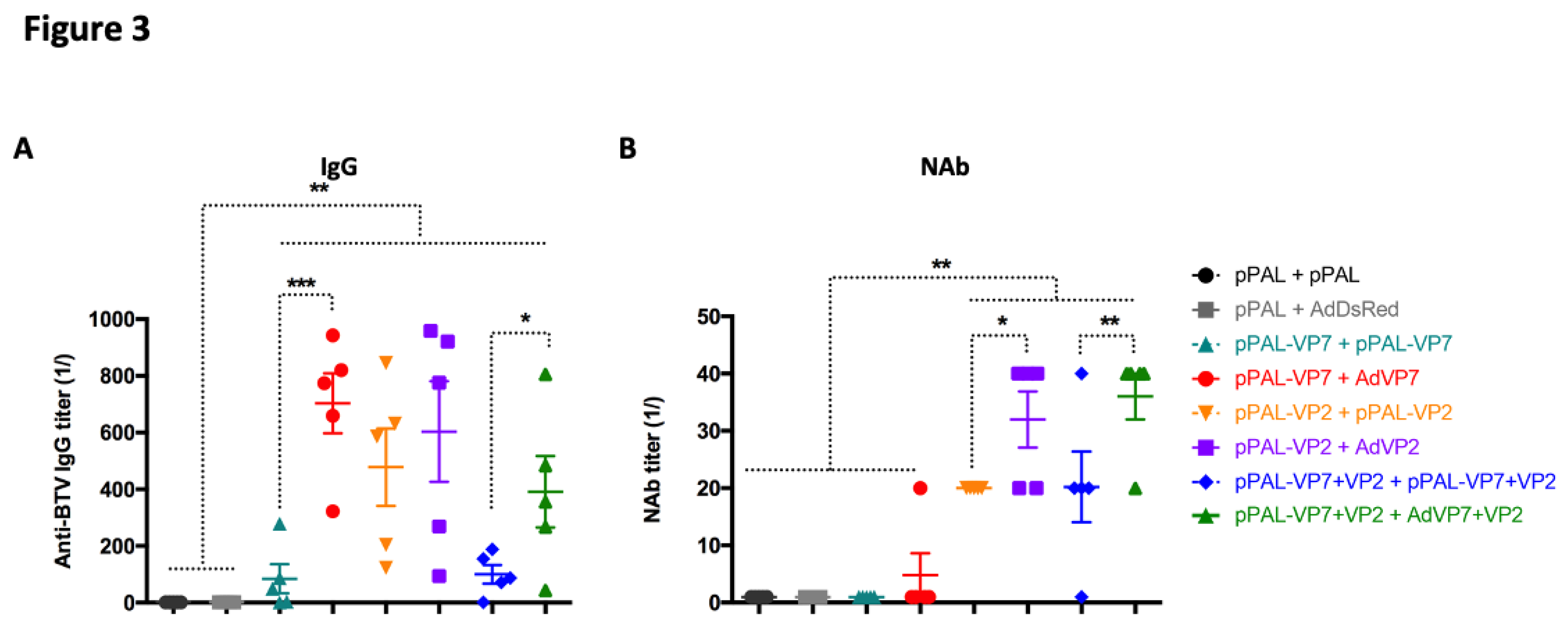

Figure 3.

pPAL and adenovirus immunization induces anti-BTV humoral immune responses. Sera from immunized mice were collected 14 days post-booster vaccination and analyzed for the presence of (A) anti-BTV IgG and (B) neutralizing antibodies (NAb) to BTV-8. (A) Anti-BTV IgG titers (1/) (mean ± SEM) were assessed by ELISA in immunized animals for each vaccination regime. (B) NAb titers to BTV-8 (1/) (mean ± SEM) were measured by seroneutralization assays in Vero cells. * p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 One-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD post-test.

Figure 3.

pPAL and adenovirus immunization induces anti-BTV humoral immune responses. Sera from immunized mice were collected 14 days post-booster vaccination and analyzed for the presence of (A) anti-BTV IgG and (B) neutralizing antibodies (NAb) to BTV-8. (A) Anti-BTV IgG titers (1/) (mean ± SEM) were assessed by ELISA in immunized animals for each vaccination regime. (B) NAb titers to BTV-8 (1/) (mean ± SEM) were measured by seroneutralization assays in Vero cells. * p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 One-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD post-test.

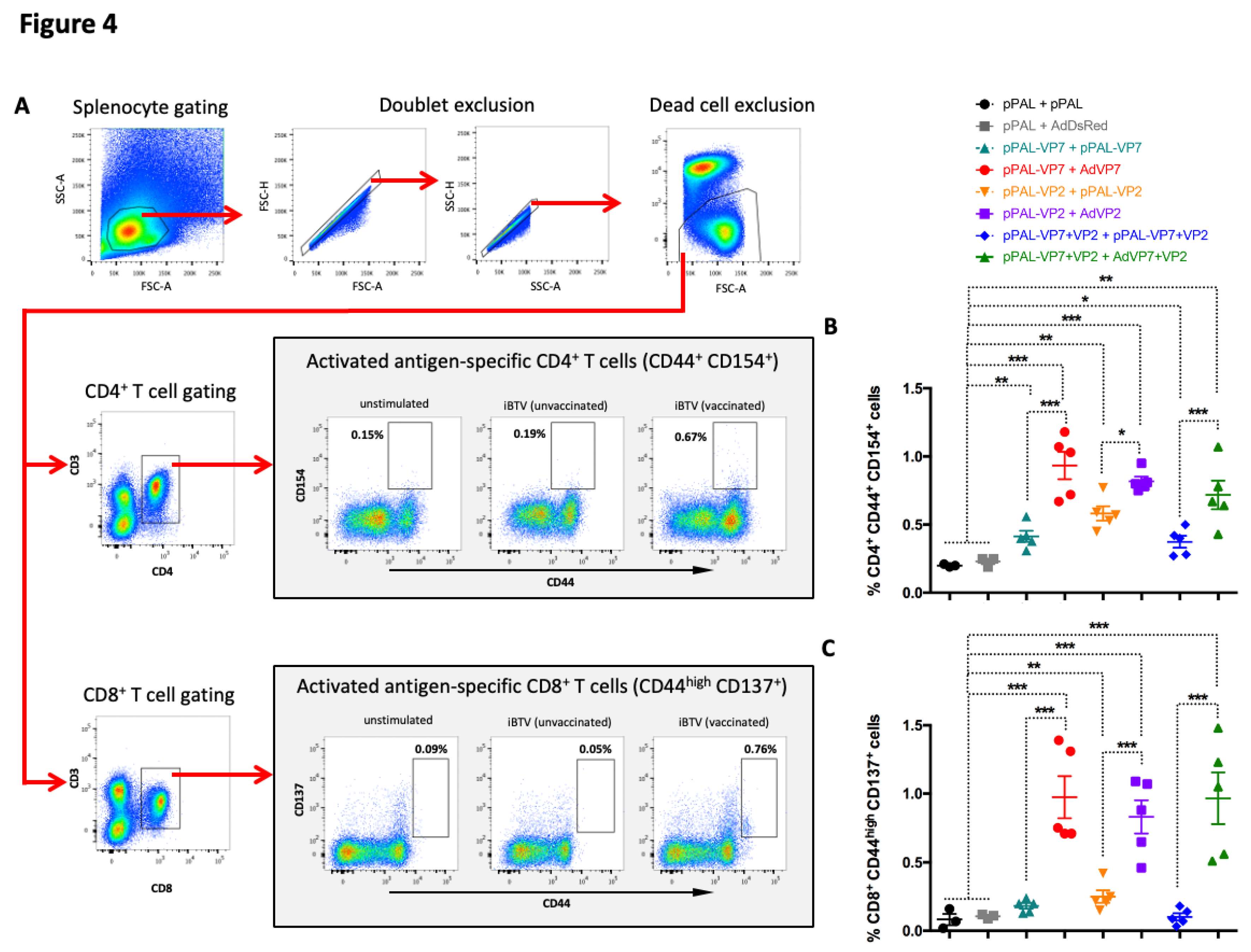

Figure 4.

Activation marker induction in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells stimulated with iBTV. Splenocytes were stimulated with iBTV (or left unstimulated as control) for 8h and stained for CD3, CD4, CD8, CD44, CD137 and CD154 expression. (A) Gating strategy for CD4+ CD44+ CD154+ and CD8+ CD44high CD137+ cells is shown. CD44+ CD154+ events for CD4+ T cells and CD44high CD137+ events for CD8+ T cells were considered activated antigen-specific cells. FSC-A/SSC-A dot-plots were used for splenocyte gating, followed by doublet and dead cell exclusion. CD3/CD4 and CD3/CD8 dot-plots were used for CD4+ T and CD8+ T cell gating respectively. Activated antigen-specific cell gating was established using unstimulated splenocytes for each culture as shown. (B) Percentage of CD4+ CD44+ CD154+ cells in iBTV cultures of vaccinated or control mice. (C) Percentage of CD8+ CD44high CD137+ cells in iBTV cultures of vaccinated or control mice. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 One-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD post-test.

Figure 4.

Activation marker induction in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells stimulated with iBTV. Splenocytes were stimulated with iBTV (or left unstimulated as control) for 8h and stained for CD3, CD4, CD8, CD44, CD137 and CD154 expression. (A) Gating strategy for CD4+ CD44+ CD154+ and CD8+ CD44high CD137+ cells is shown. CD44+ CD154+ events for CD4+ T cells and CD44high CD137+ events for CD8+ T cells were considered activated antigen-specific cells. FSC-A/SSC-A dot-plots were used for splenocyte gating, followed by doublet and dead cell exclusion. CD3/CD4 and CD3/CD8 dot-plots were used for CD4+ T and CD8+ T cell gating respectively. Activated antigen-specific cell gating was established using unstimulated splenocytes for each culture as shown. (B) Percentage of CD4+ CD44+ CD154+ cells in iBTV cultures of vaccinated or control mice. (C) Percentage of CD8+ CD44high CD137+ cells in iBTV cultures of vaccinated or control mice. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 One-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD post-test.

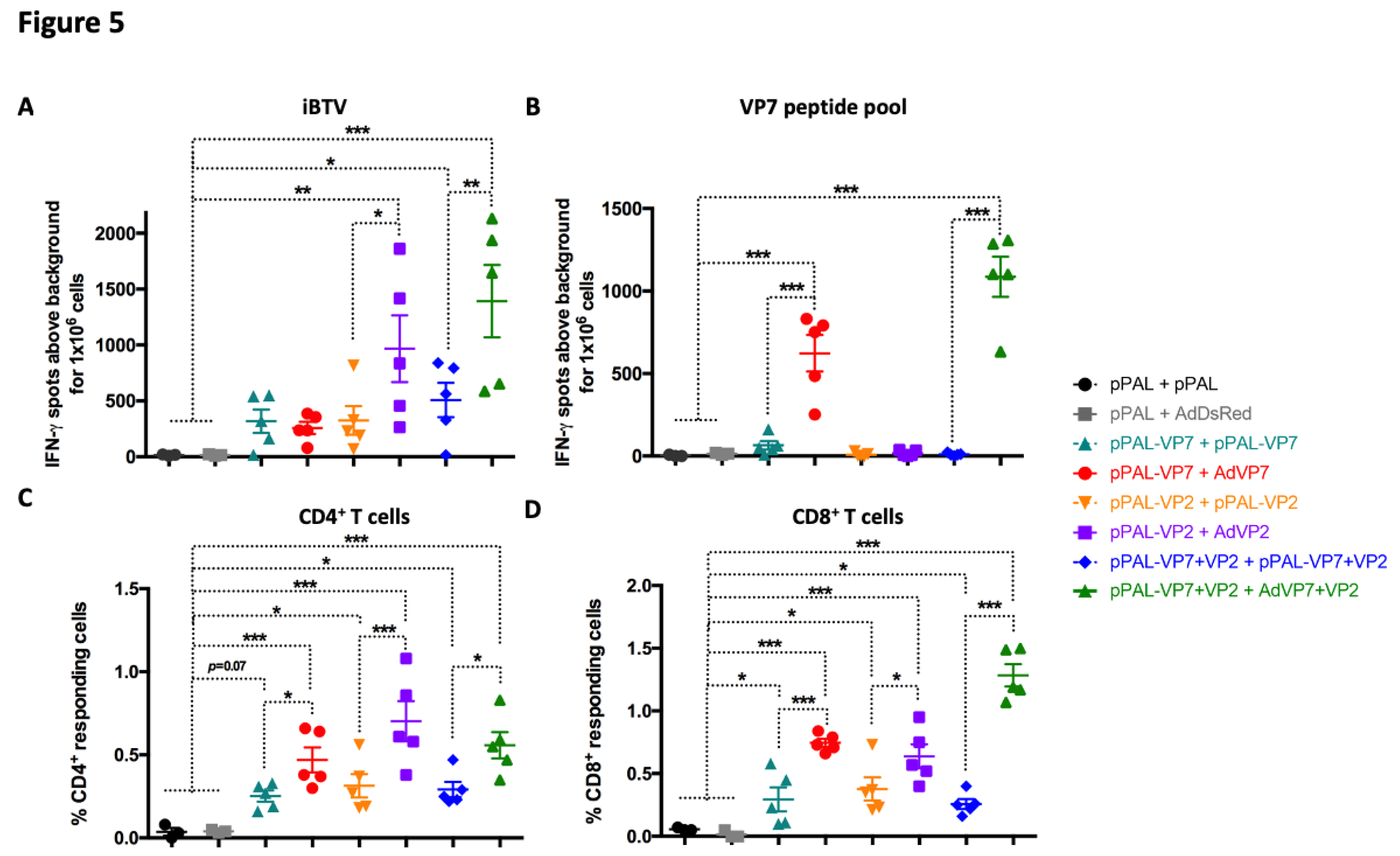

Figure 5.

Heterologous prime-boost improves T cell responses to BTV. (A and B) Splenocytes were seeded in anti-IFN-γ coated ELISPOT plates and stimulated overnight with (A) iBTV or (B) a VP7 immunogenic peptide pool. Splenocytes were discarded and ELISPOT plates revealed for IFN-γ secretion. (C and D) Intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) for CD107a, IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α was performed on iBTV stimulated splenocytes and marker expression analyzed by flow cytometry in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Total percentage of (C) CD4+ or (D) CD8+ T cells responding to iBTV stimulation (i.e. expressing at least one stimulation marker). * p<0.05; **p<0.01; *** p<0.001. One-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD post-test.

Figure 5.

Heterologous prime-boost improves T cell responses to BTV. (A and B) Splenocytes were seeded in anti-IFN-γ coated ELISPOT plates and stimulated overnight with (A) iBTV or (B) a VP7 immunogenic peptide pool. Splenocytes were discarded and ELISPOT plates revealed for IFN-γ secretion. (C and D) Intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) for CD107a, IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α was performed on iBTV stimulated splenocytes and marker expression analyzed by flow cytometry in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Total percentage of (C) CD4+ or (D) CD8+ T cells responding to iBTV stimulation (i.e. expressing at least one stimulation marker). * p<0.05; **p<0.01; *** p<0.001. One-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD post-test.

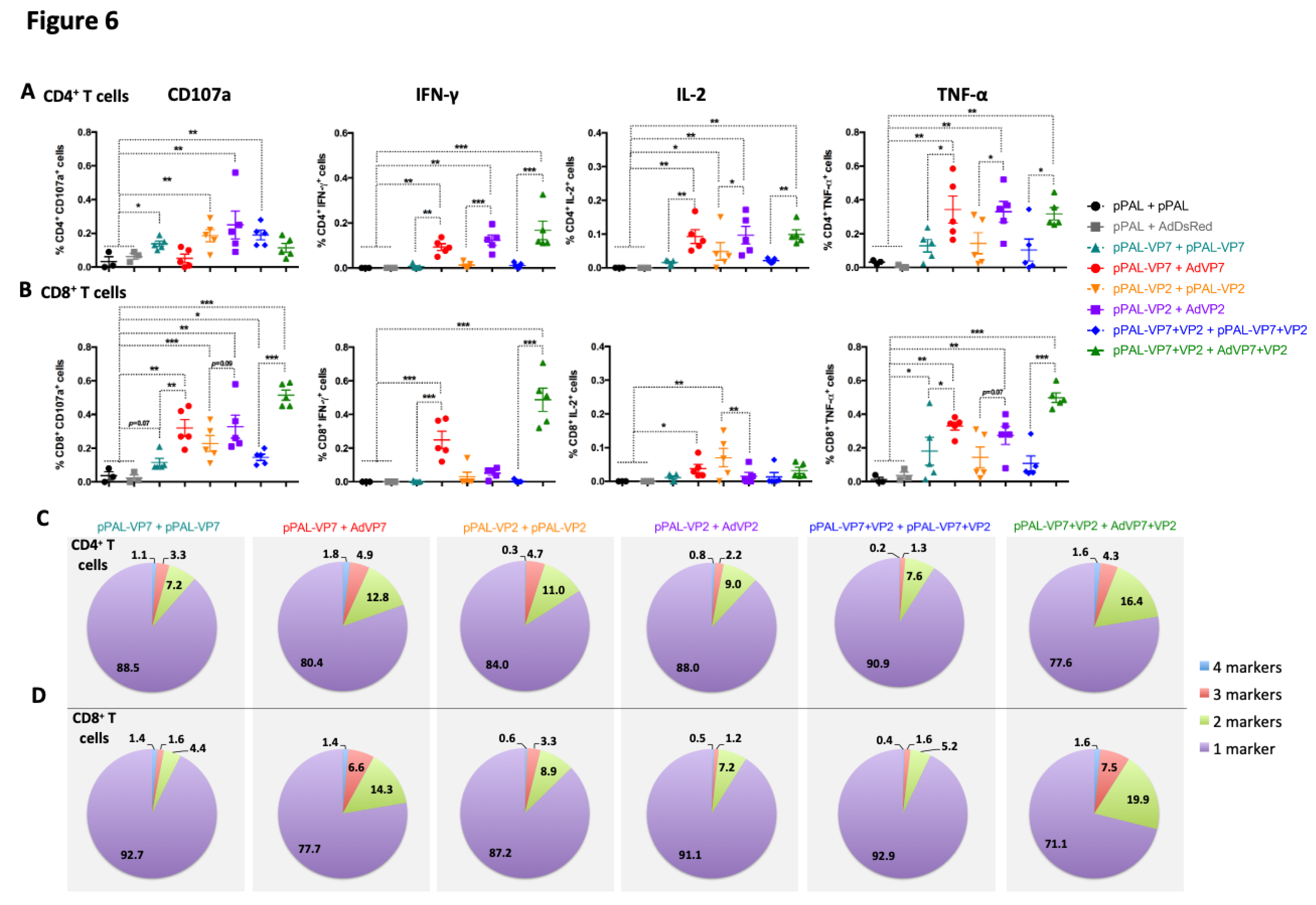

Figure 6.

Heterologous prime-boost with VP7 improves the induction of BTV-specific polyfunctional T cells. Splenocytes were stimulated with iBTV and expression of CD107a, IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α were assessed in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry analysis. (A and B) Expression of CD107a, IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α in (A) CD4+ T cells and (B) CD8+ T cells. * p<0.05; **p>0.01; *** p<0.001 One way ANOVA with Fisher‘s LSD post-test. (C and D) Percentage of simultaneous expression of one, two, three, or four stimulation markers in (C) CD4+ T cells and in (D) CD8+ T cells in response to iBTV for each vaccine regimen.

Figure 6.

Heterologous prime-boost with VP7 improves the induction of BTV-specific polyfunctional T cells. Splenocytes were stimulated with iBTV and expression of CD107a, IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α were assessed in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry analysis. (A and B) Expression of CD107a, IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α in (A) CD4+ T cells and (B) CD8+ T cells. * p<0.05; **p>0.01; *** p<0.001 One way ANOVA with Fisher‘s LSD post-test. (C and D) Percentage of simultaneous expression of one, two, three, or four stimulation markers in (C) CD4+ T cells and in (D) CD8+ T cells in response to iBTV for each vaccine regimen.

Table 1.

Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between immune parameters induced by vaccination and viral load at day 3 and 5 post-infection. Pearson correlation coefficients r were calculated with GraphPad Prism software using Ct values for BTV S5 and values of immune parameters. All coefficients had significant p values (p<10-3).

Table 1.

Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between immune parameters induced by vaccination and viral load at day 3 and 5 post-infection. Pearson correlation coefficients r were calculated with GraphPad Prism software using Ct values for BTV S5 and values of immune parameters. All coefficients had significant p values (p<10-3).

| Immune parameter |

Ct(BTV S5) D3pi |

Ct(BTV S5) D5pi |

|

p-value |

|

|

|

|

| IgG titre |

0.541 |

0.611 |

|

p<10-3

|

|

|

|

|

| NAb titre |

0.671 |

0.703 |

|

p<10-4

|

|

|

|

|

| IFN-γ counts (ELISpot) |

0.626 |

0.682 |

|

p<10-5

|

|

|

|

|

| CD4+CD44+CD154+ cells |

0.600 |

0.653 |

|

p<10-6

|

|

|

|

|

| CD8+CD44highCD137+ cells |

0.696 |

0.674 |

|

p<10-7

|

|

|

|

|

| CD4+(CD107a+/ IFN-γ+/ TNF-α+/ IL-2+) cells |

0.694 |

0.768 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CD8+ (CD107a+/ IFN-γ+/ TNF-α+/ IL-2+) cells |

0.791 |

0.814 |

|

|

|

|

|

|