1. Introduction

Virtual Reality (VR) is an innovative technology that allows users wearing the headset to immerse themselves in a different three-dimensional world with which they can interact with hand-controllers. VR is already used in several fields and different suggestions and applications have been developed also for the medical field. VR has been used in healthcare education [

1,

2,

3] and in clinical practice, to alienate patients from the stress and reclusion [

4] or to integrate traditional rehabilitative protocols [

5]. In literature, different VR applications have been proposed as rehabilitative approaches for patients with neurological conditions [

6,

7,

8], such as post-stroke and Alzheimer. The videogame of this category with the aim of motivating to fulfil the therapeutic requirements, improving physical fitness and reducing symptoms of diseases have been named “serious games” and they have been demonstrated successful and a valuable option also for elderly subjects [

9]. These games can be customized to suit the user’s abilities, allowing progress to be tracked and constantly improved. Compared to traditional methods, the use of VR allows for greater motivation and involvement, improving the rehabilitation experience and, consequently, clinical outcomes [

10]. Mixed reality has also been used in a similar context with positive results [

11,

12], although it is not an immersive but a holographic experience supplementary to the real world.

Moreover, several studies have explored how VR can be combined with art therapy to treat anxiety and social difficulties [

13] or to motivate patients during neurorehabilitation [

14,

15]. Arts efficiency in promoting health is generally recognized and the art therapy consists in treatment specifically designed on art effects [

16]. However, the outcomes of art therapy are rarely quantitative studied with founded on the principles of neuroaesthetics [

16].

In [

17], an aesthetic experience in virtual environment was presented as an upper-limb rehabilitative application for patients with neurological disorders. The immersive serious game was developed for VR headset, and it consisted in a painting activity. In front of the user, a white canvas was displayed, and the user would move his/her hand grabbing the controller to touch the canvas like painting and discovering the paint hidden under a white veil, the patient has the illusion to be able to paint an art masterpiece. With this experience, the patient can perform therapeutic movement with the arm while facing a more engaging activity. The rehabilitative protocol has been performed by patients with stroke and its efficacy has been demonstrated [

18,

19]. These VR experiences allow to record several kinematic and quantitative data useful for a post-processing evaluation of the performance through the calculation of different parameters (i.e. time of the trial, percentage of art discovered, normalized jerk, length of the trajectory make by the hand, times the hand has gone out the area of the art). Despite potentially useful also in other neurological diseases, this protocol of virtual art therapy has been applied only on patients with stroke until today.

In this study, this Virtual Art Therapy System was employed for the first time in patients with spinal cord injury, with the adjunction of a frequency analysis of their upper limb movements to assess the usability and the possible utility of this system in rehabilitation.

Global estimates suggest that in 2021, approximately 15.4 million people were living with a spinal cord injury (WHO Spinal cord injury fact sheet, 2024). In Western Europe in particular, recent studies [

20] document an incidence of between 16 and 19.4 new cases per million inhabitants per year. Spinal cord injuries represent a complex condition that has a significant impact on the patient's life, making the rehabilitation process crucial for the recovery of impaired motor and cognitive functions. The mostly used technologies for rehabilitation trainings in patients with SCI are transcranial magnetic stimulation, functional electrical stimulation and robotic-assisted therapy [

21]. However, rehabilitation aims not only to improve physical abilities, but also to support the patient's psychological and social well-being, with the goal of restoring, as far as possible, his or her autonomy in daily activities. Moreover, the deliverability and home-caring aspects should also be considered [

22]. The effectiveness of the treatment depends on a personalized approach that combines traditional rehabilitation techniques, such as the repetitive execution of task-oriented exercises, and more modern methodologies [

23]. In addition to the motor part, spinal cord injury rehabilitation must also address cognitive impairments, which are frequently present. Cognitive deficits, such as memory loss, difficulty in attention and executive processes, further limit autonomy and quality of life. However, traditional cognitive rehabilitation techniques usually focus on separate cognitive domains, without addressing the complexity of cognitive functions involved in everyday activities in an integrated manner. For this reason, it is essential to adopt an approach that considers the entire spectrum of cognitive abilities, promoting global rather than isolated improvement of individual skills and motivating approaches to rehabilitation [

24].

Several reviews [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30] have collected and analyzed literature finding to evaluate and assess the applicability of VR protocols in patients with SCI. They concord in considering VR a promising technology to produce interventions for SCI patients rehabilitation approaches and it can be used also for pain management [

31]. Also mixed reality has been used for the same purpose [

32,

33,

34].

The aim of the study is to make a first evaluation of the Virtual Art Therapy System for patients with spinal cord injury, testing its usability and performing an innovative statistical analysis of the kinematic data in order to derive new quantitative parameters, which may form the basis of future randomized clinical trials for testing the efficacy of this system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Virtual Art Therapy System: Hardware e Software

The system is composed by a Head-mounted display (HMD) for VR experience, the Meta Quest 2 with one controller for each hand. The serious game was developed in Unity engine (version 2018) built and installed on the HMD to make it work as a stand-alone device. The data about the user performances are saved automatically in txt file in the device memory (frequency of acquisition 50Hz) and they can be downloaded in a second moment connecting the HMD to the computer.

2.2. Protocol of Acquisition

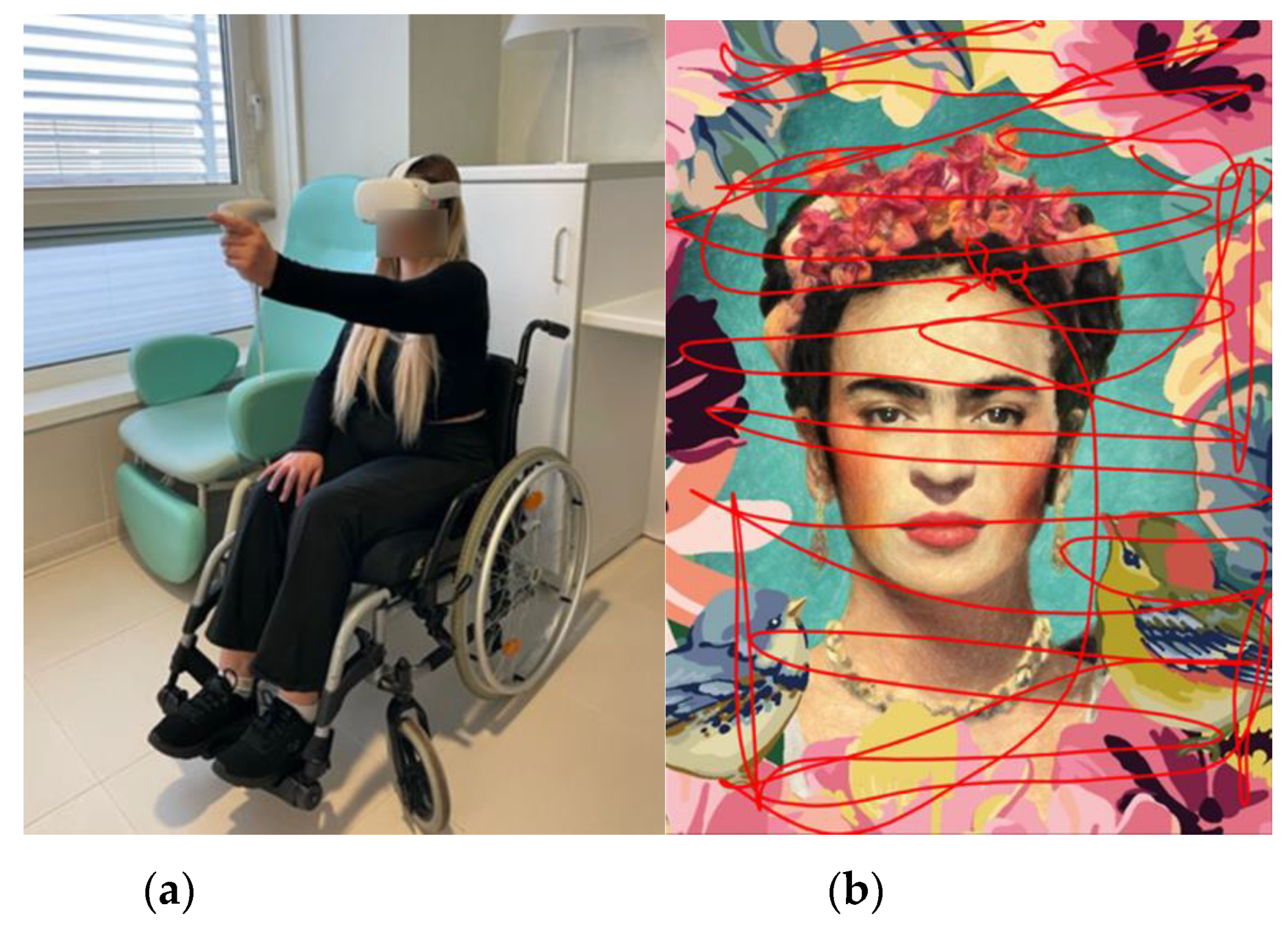

The painting experience is developed to be performed with one hand using only one controller. The other controller can be used by the therapist to manage the experience, such as changing the canvas or positioning the canvas to personalize the space according to the user’s arm length and motor capability. The participant wearing the HMD moves the controller grasped in his/her hand to interact with the canvas and to paint the virtual canvas (

Figure 1). The participant has no guide or indications according to which moves the hand, and the system was able to record the x,y,z coordinates of the hand movements.

The protocol consists in a first calibration phase, in which the user set the canvas in the correct position in space and the system record the capability of the user to reach the corners of the canvas in both horizontal and vertical orientations. After the calibration, two different lists of 30 randomized stimuli each are presented to the user. All the canvases had a rectangular shape (60 cm × 40 cm), half of the stimuli hare in a vertical orientation and half horizontal. The two lists are named “experimental” and “control”. The first list of stimuli was formed by high resolution pictures of famous paintings (such as Starry Night of van Gogh or the Creation of Adam of Michelangelo). The second list was formed by a set of undefinable stimuli maintaining the same color palette and the same amount of brightness of the art masterpieces, these stimuli were obtained by a blur-filtering of the original paintings with a low resolution to make the feature unrecognizable (according to the control stimuli previously used [

17]). The order of submission of the lists to the participants has been randomized. Each session lasted twenty minutes, for a total of forty minutes of therapy. During this time, the participant was required to uncover as many canvases as possible. The time of each session also included any breaks, which were necessary to allow the participant to rest.

The protocol of acquisition is common between the two groups of subjects. The main difference regards the presence of the physiotherapist near the patient during the experience. Considering the system as a tool for clinicians, the physiotherapist had the liberty to intervene to help the patient in the activity.

To evaluate the usability of the system, after the experiment, the NASA Task Load Index [

35] and the User Satisfaction Evaluation Questionnaire (USEQ) [

36] were evaluated for both the “control” and “experimental” lists and both the groups of participants.

2.3. Partecipants

A group of 13 healthy subjects (30 ± 7 years old) were acquired in the laboratory of Industrial Bioengineering of Sapienza University of Rome, they presented no comorbidities or musculoskeletal diseases, and they were volunteers providing informed consent before the experiment. Because the aim of enrolling a control group was to obtain the reference values of the best possible performance during the task, we enrolled young adults.

The group of 13 patients (50 ± 20 years old) with spinal cord injury consisted of patients admitted to the IRCCS Fondazione Santa Lucia. where the experimental activities took place. This study was approved by the Lazio Area 5 Territorial Ethics Committee. Before the training session, clinical staff evaluated the patient with different clinical scales: Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM); Graded Redefined Assessment of Strength, Sensibility, and Prehension (GRASSP); Upper Extremity Motor Score (UEMS); Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS).

The inclusion criteria, against which patients were selected for virtual reality rehabilitation training, consider cognitive abilities, in order to understand and perform the required task, and both traumatic and non-traumatic spinal cord injury events. Patients were classified according to the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI) with impairment grade C or D as defined by the scale proposed by the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA), and UEMS score higher than 12. Respiratory non-autonomous subjects, with severe neurological nonspecific spinal cord injury associated with upper limb impairment (e.g., brachial plexus injury, severe cerebral plexus injury, etc.), as well as subjects with a medical history of visual disturbances or a diagnosis of photosensitive epilepsy or with seizure episodes were excluded from the study.

Information of the patients are reported in

Table 1.

2.4. Kinematic Data Acquisition and Processing

The data saved from the performance are:

Controller’s coordinates in space and time;

“score”, the percentage of pixels discovered of the canvas;

“error”, the number of times the controller went through the canvas exceeding 2,9 cm.

These data were elaborated and analyzed in post-processing with a MATLAB specific script. About the controller’s trajectories, only the x and y coordinates were considered to study the plane of the canvas, then the trajectories have been elaborated selecting only the samples of the actual canvas uncover activities and applying a moving average filter. From these data, some parameters have been calculated. The kinematic quantities:

and the spectral quantities obtained from an analysis in the frequency domain for trajectory on separately x and y components, taking into account the sampling frequency of the system (50Hz):

dominant frequency of the power spectrum (Hz), selected as the frequency of the spectrum with the highest magnitude;

mean value of magnitude of the spectrum (in meters, m);

energy spectrum (m2), calculated as the sum of the squares of the amplitudes of the spectrum;

variance of the spectrum (m2), calculated as the dispersion of the spectral content around its centroid.

2.5. Statistica Analysis

Each parameter has been calculated for both “control” and “experimental” stimuli and for each participant. Then, medians and quartiles (in box-whiskers plot) or means for each group have been reported. An inferential statistical analysis has been performed to compare the results from the two groups of subjects. After a normality check, a T-test or a Wilcoxon test was applied according to the data distribution. For all the analyses the alpha level of statistical significance was set at 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Kinematic and Spectral Quantities

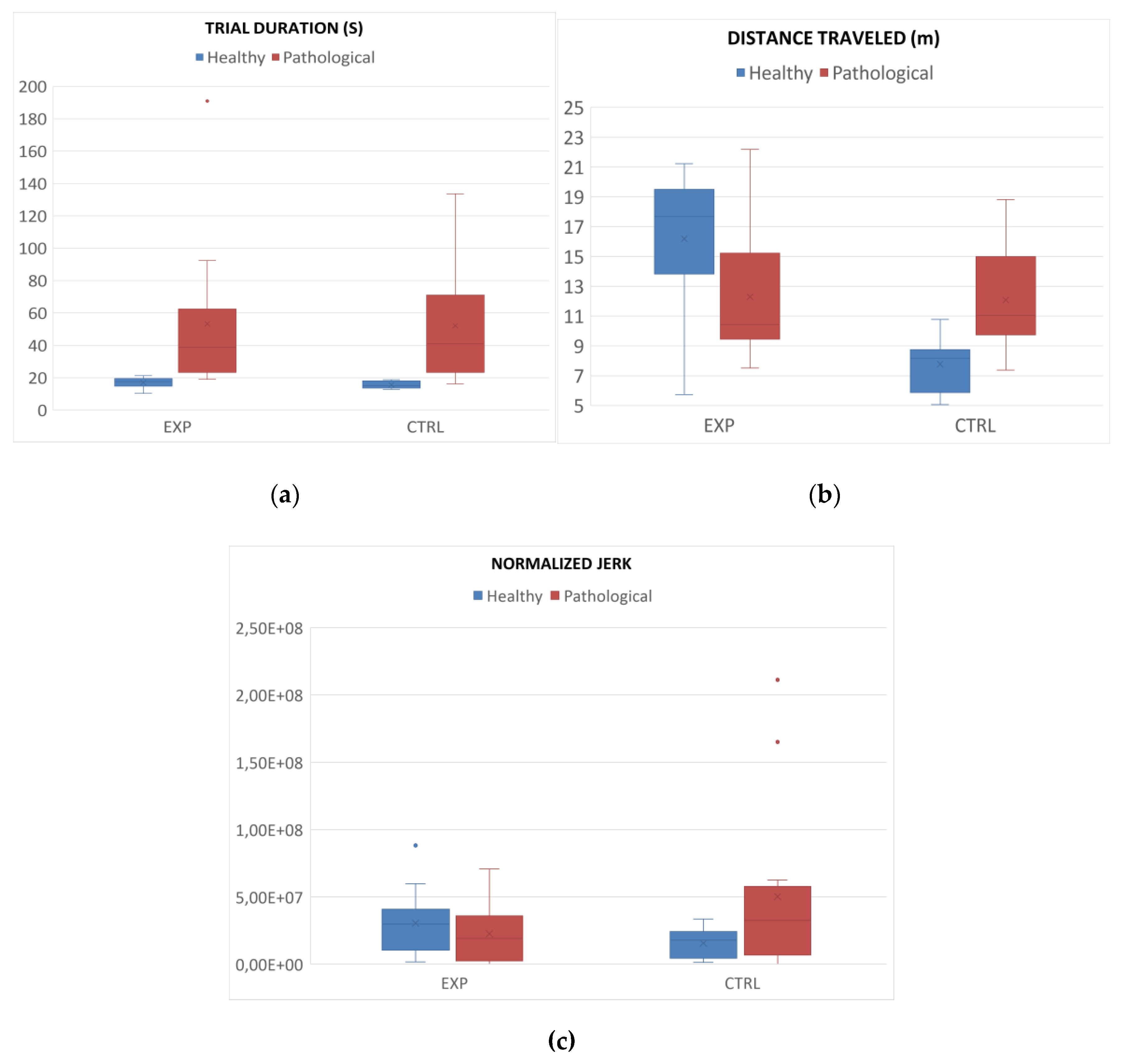

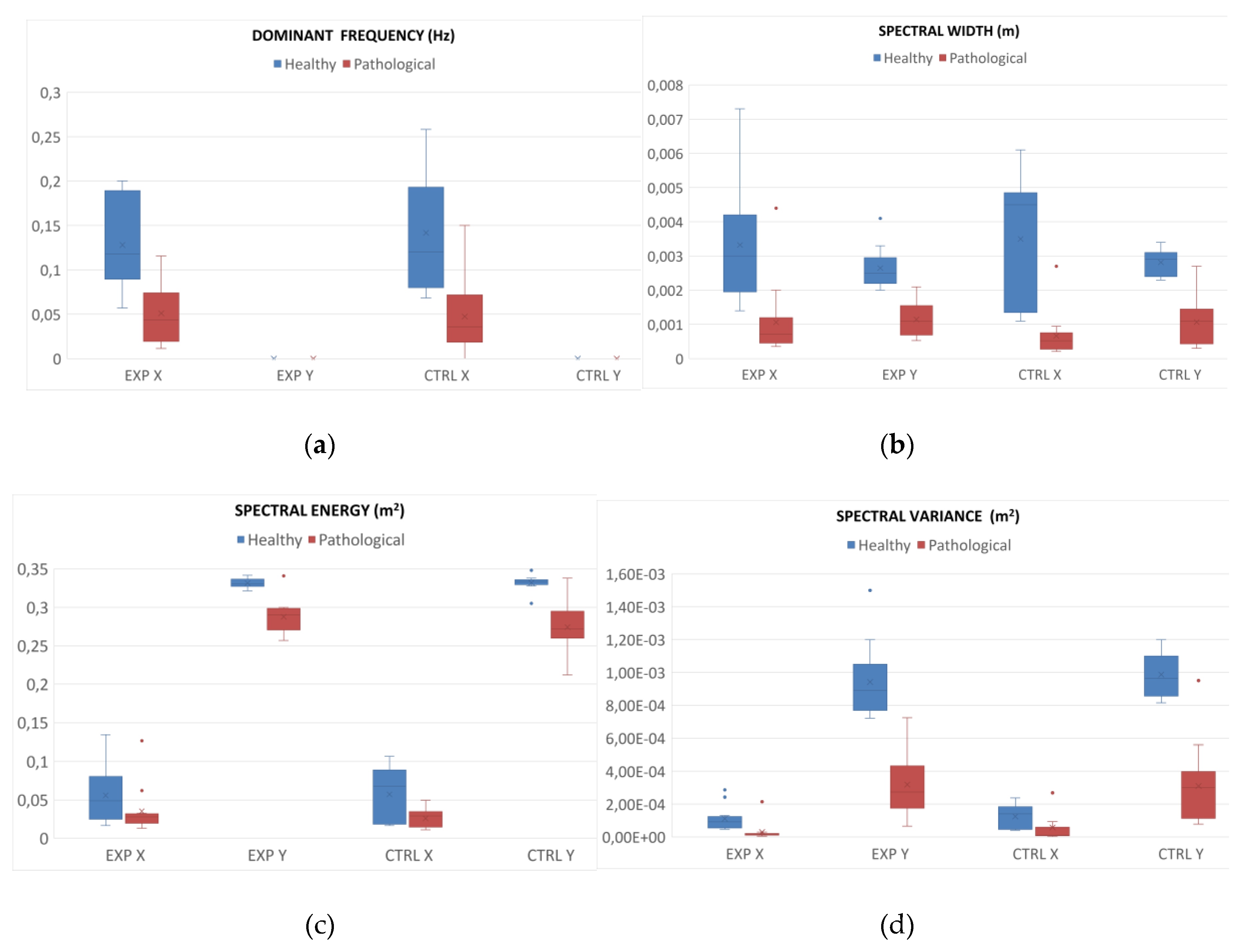

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 shows the results about the values of the parameters calculated for both groups, healthy subjects and patients, and for both lists, “control” and “experimental” stimuli, in healthy and pathological subjects.

Table 2 and

Table 3 report the results (p-value) of the t-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for each parameter between the two group of subjects for both control and experimental lists.

3.2. Usability

To evaluate the usability of the system, NASA and USEQ questionnaires were submitted to the participants and the final scores were calculated. USEQ items mean values were 4,24 (on 5) for “control” and 4,37 (on 5) for “experimental” with a final comprehensive score of 25,46 and 26,23 respectively. 4.69 and 5 were the scores for the “clarity” item and 4.69 and 4.46 for the “successful use”. No statistically significant differences were found out between healthy subjects and patients.

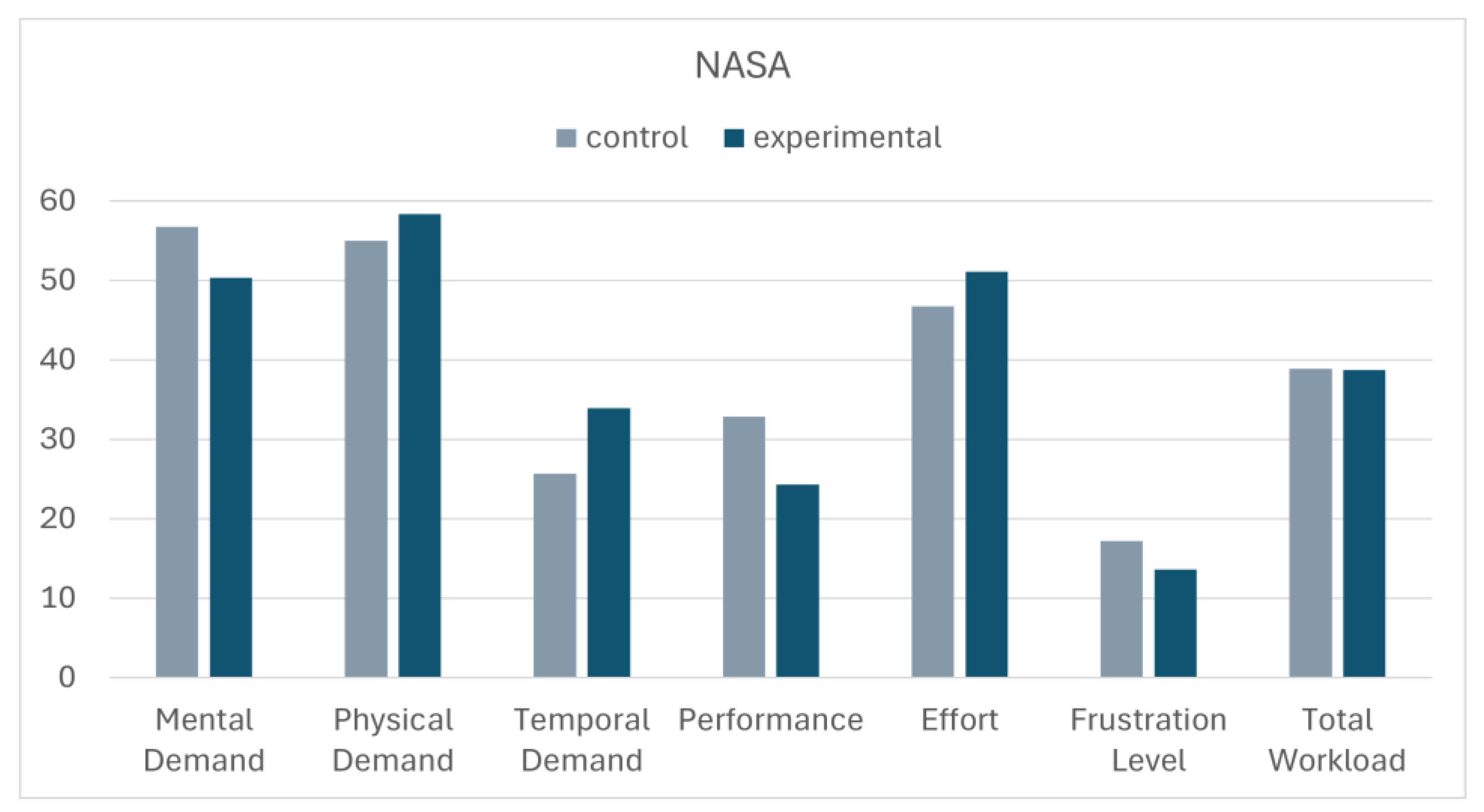

While the mean values for the NASA among the items were for “control” and “experimental” stimuli respectively reported on the bar chart of

Figure 4. The t-test applied to compare the two lists shows only a significant different for the “Temporal Demand” item. Despite longer time was required for artistic paintings, neither effort nor frustration were significantly higher for these stimuli.

4. Discussion

The main objective of the research was to verify the usability and feasibility of an innovative approach to upper limb rehabilitation based on the development of immersive virtual reality in patients with spinal cord injury.

The analyses conducted in this context showed significant and promising results that provide a quantitative perspective in the use of art therapy to support rehabilitation methods. Statistical analysis of the parameters in comparison with the control group of healthy subjects showed several significant results for this disease in both the categories of stimuli. Among the kinematic quantities, the time of the trial and the length of the trajectory are both statistically significant, while the normalize jerk has given no significative results.

Another innovative aspect of this study was the spectral analysis that allowed to obtain parameters from the frequency analysis of the one-dimensional trajectories over time of the subject's hand, that were not calculated in previous applications of this system [

17,

18,

19]. The results of this study demonstrate that both healthy and pathological subjects, in front of a canvas and without guides to follow, prioritize the horizontal movement of the hand over the vertical one, demonstrated by the fact that the dominant frequencies on the y-axis are zero. Furthermore, the other spectral parameters, energy, variance and amplitude of the spectrum, are mostly statistically significant between the patient and healthy groups. This result could be associated to the main deficit in shoulder flexion in patients with spinal cord injury, and to the need of help for contrasting gravity during the upper limb treatment of these patients. In further studies, this analysis could be important to verify the match between the rehabilitative aims and the actual execution of the tasks by the patients.

Consequently, this collection of parameters could be used to assess the patient's improvement performance during rehabilitation activity and thus support the physiotherapist in selecting and adapting the patient's rehabilitation protocol. It will be particularly supportive to further confirm the validity of these quantitative parameters when correlations with qualitative clinical scales are made. In this way, assessment scales can be created to complement the clinical ones.

Furthermore, it is interesting to note, that although the patients were in some cases helped by physiotherapists who deemed it necessary for the rehabilitation pathway of the patients, the results also show a clear difference with the reference group.

Virtual reality was already used in the rehabilitation of patients with spinal cord injury for the recovery of walking ability [

26], pain relief [

30], upper limb functional recovery [

38]. Also the art-therapy was administered on these patients, but painting protocols were mainly used only for improving their mood and well-being [

39,

40]. Our study was the first one combined these two approaches in patients with spinal cord injury.

The System was based on the Michelangelo effect that was described as an effect of art in reducing the fatigue and improving the performance of patients [

17,

18,

19]. In this study, it could be observed in some parameters recorded for patients that resulted more similar to those recorded for healthy subjects for artistic stimuli and not for control stimuli, such as the energy spectrum along x-axis and the normalized jerk. We did not observe a reduction of fatigue, but patients reported a higher temporal demand for artistic stimuli, despite the effort was not higher in presence of art, and not real differences were observed in terms of timing needed to complete the task.

It must be borne in mind that no inclusion criteria were set for this study regarding the age of the participants. In fact, the age range of the patients is very wide, with the only limitation being the age of majority, while for the control group, an attempt was made to create a reference group corresponding to the best possible performance.

A limit of our study is the sample size: the small sample of patients may not allow generalization of the results obtained and that the lack of long-term follow-up limits the possibility of assessing the sustainability of the improvements observed over time. These activities will be carried out in subsequent studies in order to suggest a clinical practice guidelines based on evidence from a randomized controlled trial [

41].

The results obtained from the NASA and USEQ scales by the patients support the usability of the system. In particular, the scores provided for the USEQ items demonstrate that the system was understood and appreciated by all the patients. The NASA results show that the total workload is 40%, but it is necessary to consider the wide range of age and degree of pathology of the patients. In fact, the minimum score for workload was 6.67 and the maximum 78.33. Furthermore, no significant differences were found between the control and experimental stimuli, for both scales. The only significant item was the perception of time required by the exercise, which was greater for the experimental subjects, both for the global average and for the scores attributed by the individual patients. This can be explained by considering that for the experimental stimulus the subject was more inclined to observe the painting instead of proceeding quickly in the mere gesture of uncovering the canvas.

5. Conclusions

The immersive virtual system based on the Michelangelo effect was used on a group of patients with Spinal Cord Injury and on a control group of healthy subjects. Kinematic and spectral parameters were calculated and compared between the two groups. The results obtained support the hypothesis that these parameters allow to quantitatively evaluate the performance of the patients and that therefore they could be useful for future acquisitions and the creation of quantitative scales to support purely qualitative clinical scales. Furthermore, the NASA and USEQ scales have received positive evaluation feedback on the system from patients, making it easy to understand and use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I.; development of the VR System: G.T. and M.I.; methodology, S.D.A.; software, G.T.; validation, M.F.; data collection, G.G.C. and V.L.; formal analysis, G.C.; investigation, F.T.; resources, M.I., G.S. and F.T.; data curation, G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F.; writing—review and editing, M.I. and F.T.; visualization, F.B. and F.M.; supervision, G.S.; project administration, M.I.; funding acquisition, M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was founded by the NEUROMETAVERSE project financed in the framework of Translational Research Line of Santa Lucia Foundation by the Italian Ministry of Health, an by the HeART Project financed by Sapienza University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Lazio Area 5 Territorial Ethics Committee for clinical studies (Protocol code: 154/SL/24, date of approval: 22th May 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Signed informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Because data involve clinical information of patients an anonymous database is available only after motivated requests to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sung, H.; Kim, M.; Park, J.; Shin, N.; Han, Y. Effectiveness of Virtual Reality in Healthcare Education: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sustain. 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Tene, T.; Vique López, D.F.; Valverde Aguirre, P.E.; Orna Puente, L.M.; Vacacela Gomez, C. Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality in Medical Education: An Umbrella Review. Front. Digit. Heal. 2024, 6, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Mergen, M.; Graf, N.; Meyerheim, M. Reviewing the Current State of Virtual Reality Integration in Medical Education - a Scoping Review. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Graf, L.; Liszio, S.; Masuch, M. Playing in Virtual Nature: Improving Mood of Elderly People Using VR Technology. ACM Int. Conf. Proceeding Ser. 2020, 155–164. [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Li, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Ma, J.; Li, G.; Gan, L.; Shang, X.; Wu, Z. Virtual Reality Rehabilitation versus Conventional Physical Therapy for Improving Balance and Gait in Parkinson’s Disease Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 4186–4192. [CrossRef]

- Quan, W.; Liu, S.; Cao, M.; Zhao, J. A Comprehensive Review of Virtual Reality Technology for Cognitive Rehabilitation in Patients with Neurological Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Mani Bharathi, V.; Manimegalai, P.; George, S.T.; Pamela, D.; Mohammed, M.A.; Abdulkareem, K.H.; Jaber, M.M.; Damaševičius, R. A Systematic Review of Techniques and Clinical Evidence to Adopt Virtual Reality in Post-Stroke Upper Limb Rehabilitation. Virtual Real. 2024, 28. [CrossRef]

- Ceradini, M.; Losanno, E.; Micera, S.; Bandini, A.; Orlandi, S. Immersive VR for Upper-Extremity Rehabilitation in Patients with Neurological Disorders: A Scoping Review. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2024, 21, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Wiemeyer, J.; Kliem, A. Serious Games in Prevention and Rehabilitation-a New Panacea for Elderly People? Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 41–50. [CrossRef]

- Bressler, M.; Merk, J.; Gohlke, T.; Kayali, F.; Daigeler, A.; Kolbenschlag, J.; Prahm, C. A Virtual Reality Serious Game for the Rehabilitation of Hand and Finger Function: Iterative Development and Suitability Study. JMIR Serious Games 2024, 12, e54193. [CrossRef]

- Franzò, M.; Marinozzi, F.; Finti, A.; Lattao, M.; Trabassi, D.; Castiglia, S.F.; Serrao, M.; Bini, F. Mixed Reality-Based Smart Occupational Therapy Personalized Protocol for Cerebellar Ataxic Patients. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1023. [CrossRef]

- Ham, Y.; Yang, D.S.; Choi, Y.; Shin, J.H. Effectiveness of Mixed Reality-Based Rehabilitation on Hands and Fingers by Individual Finger-Movement Tracking in Patients with Stroke. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2024, 21, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Shamri Zeevi, L. Making Art Therapy Virtual: Integrating Virtual Reality Into Art Therapy With Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Hadjipanayi, C.; Banakou, D.; Michael-Grigoriou, D. Art as Therapy in Virtual Reality: A Scoping Review. Front. Virtual Real. 2023, 4, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Salera, C.; Capua, C.; De Angelis, D.; Coiro, P.; Venturiero, V.; Savo, A.; Marinozzi, F.; Bini, F.; Paolucci, S.; Antonucci, G.; et al. Michelangelo Effect in Cognitive Rehabilitation: Using Art in a Digital Visuospatial Memory Task. Brain Sci. 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Iosa, M.; Antonucci, G.; De Bartolo, D. Are Neuroaesthetic Principles Applied in Art Therapy Protocols for Neurorehabilitation? A Systematic Mini-Review. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Iosa, M.; Aydin, M.; Candelise, C.; Coda, N.; Morone, G.; Antonucci, G.; Marinozzi, F.; Bini, F.; Paolucci, S.; Tieri, G. The Michelangelo Effect: Art Improves the Performance in a Virtual Reality Task Developed for Upper Limb Neurorehabilitation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- De Giorgi, R.; Fortini, A.; Aghilarre, F.; Gentili, F.; Morone, G.; Antonucci, G.; Vetrano, M.; Tieri, G.; Iosa, M. Virtual Art Therapy: Application of Michelangelo Effect to Neurorehabilitation of Patients with Stroke. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Tieri, G.; Iosa, M.; Fortini, A.; Aghilarre, F.; Gentili, F.; Rubeca, C.; Mastropietro, T.; Antonucci, G.; De Giorgi, R. Efficacy of a Virtual Reality Rehabilitation Protocol Based on Art Therapy in Patients with Stroke: A Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 863. [CrossRef]

- Scivoletto, G.; Miscusi, M.; Forcato, S.; Ricciardi, L.; Serrao, M.; Bellitti, R.; Raco, A. The Rehabilitation of Spinal Cord Injury Patients in Europe. In; 2017; pp. 203–210 ISBN 9783319395456.

- Duan, R.; Qu, M.; Yuan, Y.; Lin, M.; Liu, T.; Huang, W.; Gao, J.; Zhang, M.; Yu, X. Clinical Benefit of Rehabilitation Training in Spinal Cord Injury. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976). 2021, 46, E398–E410. [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.; Atchison, K.; Noonan, V.K.; McKenzie, N.; Cadel, L.; Ganshorn, H.; Rivera, J.M.B.; Yousefi, C.; Guilcher, S.J.T. Models of Care Delivery from Rehabilitation to Community for Spinal Cord Injury: A Scoping Review. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 677–697. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Mendoza, B.; A. Santiago-Tovar, P.; A. Guerrero-Godinez, M.; García-Vences, E. Rehabilitation Therapies in Spinal Cord Injury Patients. In Paraplegia; IntechOpen, 2021.

- Stasolla, F.; Lopez, A.; Akbar, K.; Vinci, L.A.; Cusano, M. Matching Assistive Technology, Telerehabilitation, and Virtual Reality to Promote Cognitive Rehabilitation and Communication Skills in Neurological Populations: A Perspective Proposal. Technologies 2023, 11, 43. [CrossRef]

- Orsatti Sánchez, B.A.; Diaz Hernandez, O. Efficacy of Virtual Reality in Neurorehabilitation of Spinal Cord Injury Patients: A Systematic Review. Rev. Mex. Ing. Biomed. 2021, 42, 90–103. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Ai, H.; Liu, Y. Effects of Virtual Reality Rehabilitation after Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2024, 21, 191. [CrossRef]

- Alashram, A.R.; Padua, E.; Hammash, A.K.; Lombardo, M.; Annino, G. Effectiveness of Virtual Reality on Balance Ability in Individuals with Incomplete Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 72, 322–327. [CrossRef]

- de Miguel-Rubio, A.; Dolores Rubio, M.; Alba-Rueda, A.; Salazar, A.; Moral-Munoz, J.A.; Lucena-Anton, D. Virtual Reality Systems for Upper Limb Motor Function Recovery in Patients with Spinal Cord Injury: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Chi, B.; Chau, B.; Yeo, E.; Ta, P. Virtual Reality for Spinal Cord Injury-Associated Neuropathic Pain: Systematic Review. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 62, 49–57. [CrossRef]

- Scalise, M.; Bora, T.S.; Zancanella, C.; Safa, A.; Stefini, R.; Cannizzaro, D. Virtual Reality as a Therapeutic Tool in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation: A Comprehensive Evaluation and Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Leemhuis, E.; Giuffrida, V.; Giannini, A.M.; Pazzaglia, M. A Therapeutic Matrix: Virtual Reality as a Clinical Tool for Spinal Cord Injury-Induced Neuropathic Pain. Brain Sci. 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Heyn, P.; Baumgardner, C.; McLachlan, L.; Bodine, C. Mixed-Reality Exercise Effects on Participation of Individuals with Spinal Cord Injuries and Developmental Disabilities: A Pilot Study. Top. Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 2014, 20, 338–345. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, S.D.; Aaby, A.O.; Ravn, S.L. Psychological Outcomes of Extended Reality Interventions in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation: A Systematic Scoping Review. Spinal Cord 2025. [CrossRef]

- DeBre, E.; Gotsis, M. The Feasibility of Mixed Reality Gaming as a Tool for Physical Therapy Following a Spinal Cord Injury. J. Emerg. Investig. 2018, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, L.; Quiles, V.; Ortiz, M.; Iáñez, E.; Gil-Agudo, Á.; Azorín, J.M. Brain-Computer Interface Enhanced by Virtual Reality Training for Controlling a Lower Limb Exoskeleton. iScience 2023, 26. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Gómez, J.A.; Manzano-Hernández, P.; Albiol-Pérez, S.; Aula-Valero, C.; Gil-Gómez, H.; Lozano-Quilis, J.A. USEQ: A Short Questionnaire for Satisfaction Evaluation of Virtual Rehabilitation Systems. Sensors (Switzerland) 2017, 17, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.H.; Hinrichs, R.N.; Payne, V.G.; Thomas, J.R. Normalized Jerk: A Measure to Capture Developmental Characteristics of Young Girls’ Overarm Throwing. J. Appl. Biomech. 2000, 16, 196–203. [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.Y.; Hwang, D.M.; Cho, K.H.; Moon, C.W.; Ahn, S.Y. A Fully Immersive Virtual Reality Method for Upper Limb Rehabilitation in Spinal Cord Injury. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 44, 311–319. [CrossRef]

- Macrì, E.; Limoni, C. Artistic Activities and Psychological Well-Being Perceived by Patients with Spinal Cord Injury. Arts Psychother. 2017, 54, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Nazari, H.; Saadatjoo, A.; Tabiee, S.; Nazari, A. The Effect of Clay Therapy on Anxiety, Depression, and Happiness in People with Physical Disabilities. Mod. Care J. 2018, In Press. [CrossRef]

- Gerber, L.H.; Deshpande, R.; Prabhakar, S.; Cai, C.; Garfinkel, S.; Morse, L.; Harrington, A.L. Narrative Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Rehabilitation of People With Spinal Cord Injury: 2010-2020. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 100, 501–512. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).