Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Location, Materials and Methods

| Meteorological Data | |||||||

| Station Name | Coordinates | Data Type | Resolution | Period | |||

| Davis Station "Valley" | 33°45'33.65"N 35°55'43.83"E Bekaa Valley (Rural) |

Wind speed Wind direction Air temperature |

Half hourly | 2022 Summer season |

|||

| Davis Station « Highway » | 33°50'17.12"N 35°55'6.64"E Urban area of Zahlé |

Wind speed Wind direction Air temperature |

Half hourly | 2022 Summer season |

|||

| Davis Station « Hill » | 33°50'59.68"N 35°54'33.55"E Slope Peri-urban |

Wind speed Wind direction Air temperature |

Half hourly | 2022 Summer season |

|||

| Davis Station « Home » | 33°51'10.67"N 35°55'17.01"E Peri-urban |

Wind speed Wind direction Air temperature |

Half hourly | 2023 Summer season |

|||

| Mobile Measurements | Zahlé Region (Urban and rural areas) | Air temperature, wind speed, vertical atmospheric temperature | - | 2022-2023 Summer season |

|||

| Satellite data | |||||||

| Satellite | Band | Spatial Resolution | Spectral Resolution | ||||

| Aster-TIR | Thermal bands (B10 to B14) | 90 m | 8.125 – 11.65 μm | ||||

3. Results

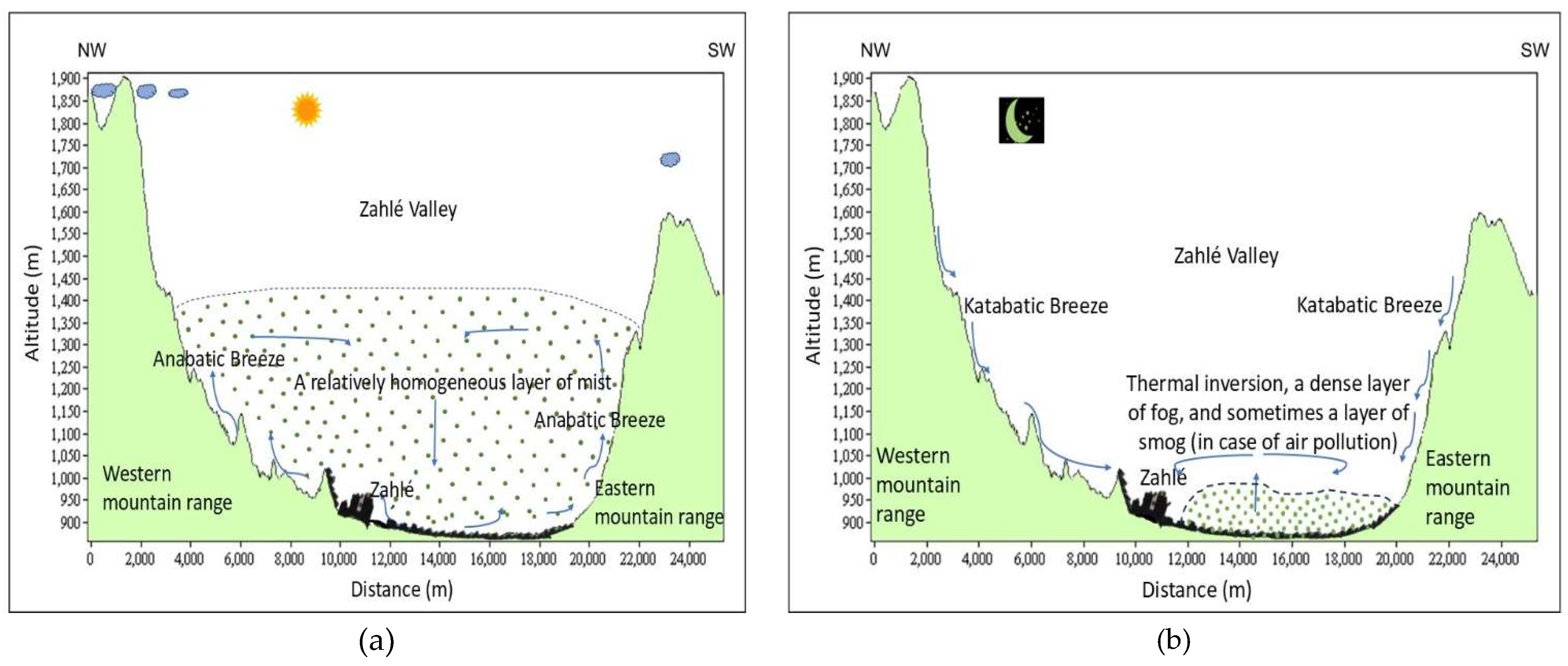

3.1. Thermal Breezes Types and Characteristics

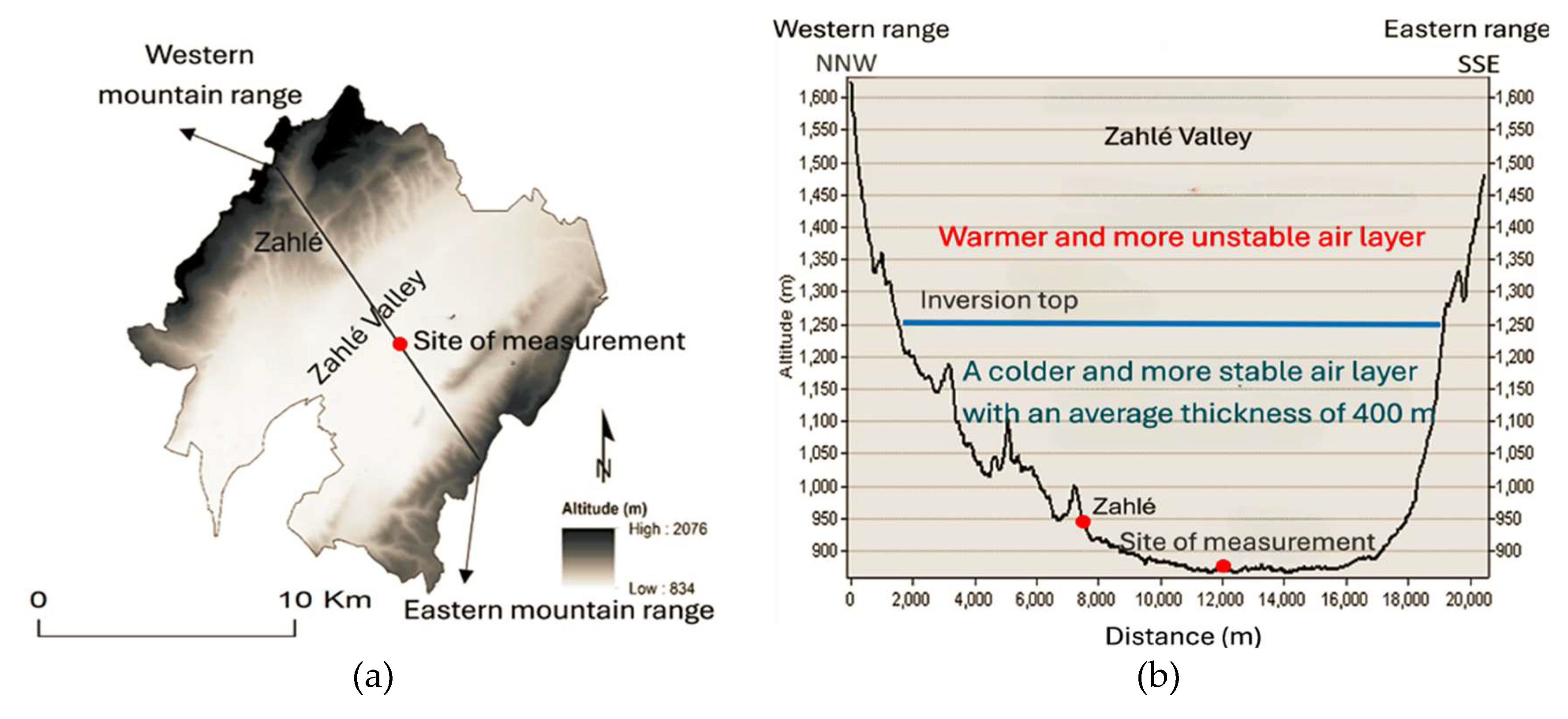

- The Davis "Highway" station, installed in 2022 in the Zahlé urban area. This is an urban station located at an altitude of 914 meters above sea level;

- The Davis "Valley" station, installed in 2022 in the Bekaa Valley, in a rural site within the rural area of the Bar Elias municipality. This station is located at an altitude of 870 meters;

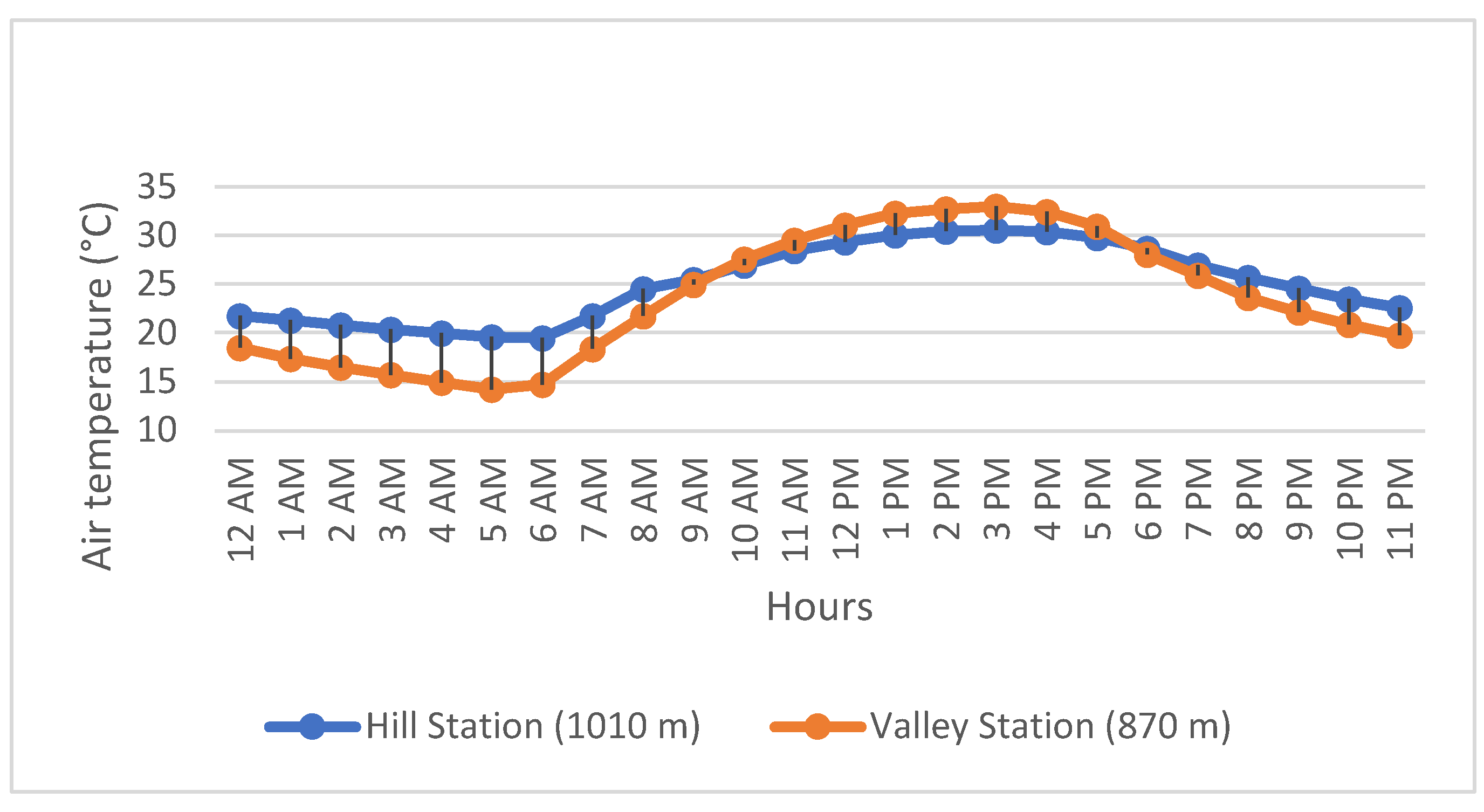

- The Davis "Hill" station, established in 2022 on a peri-urban hill around the Zahlé agglomeration. This station is situated at an altitude of 1010 meters above sea level;

- The Davis "Home" station, installed in 2023 on a slope in a peri-urban site at an altitude of 990 meters above sea level.

3.2. Air Temperature

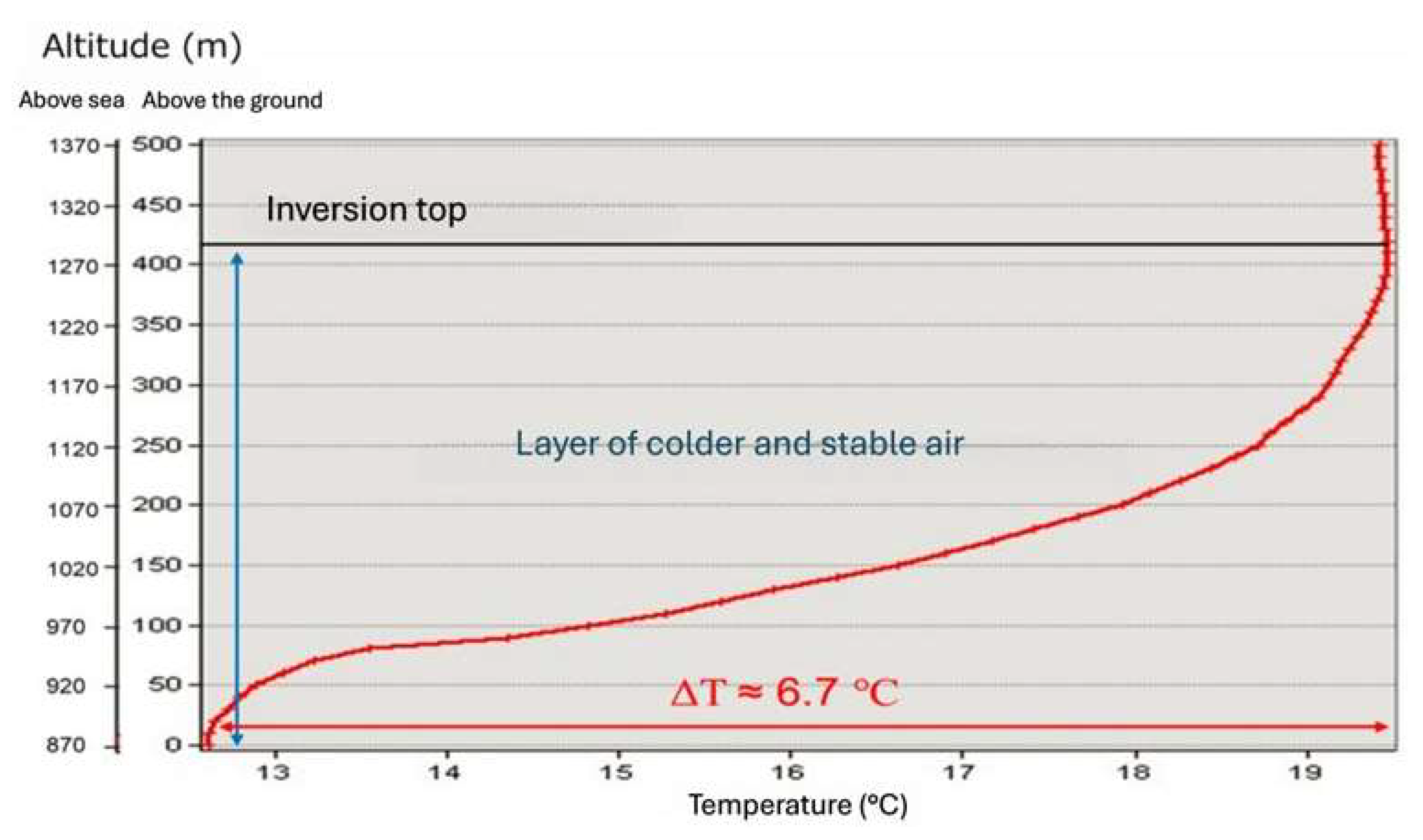

3.2.1. Thermal Inversion

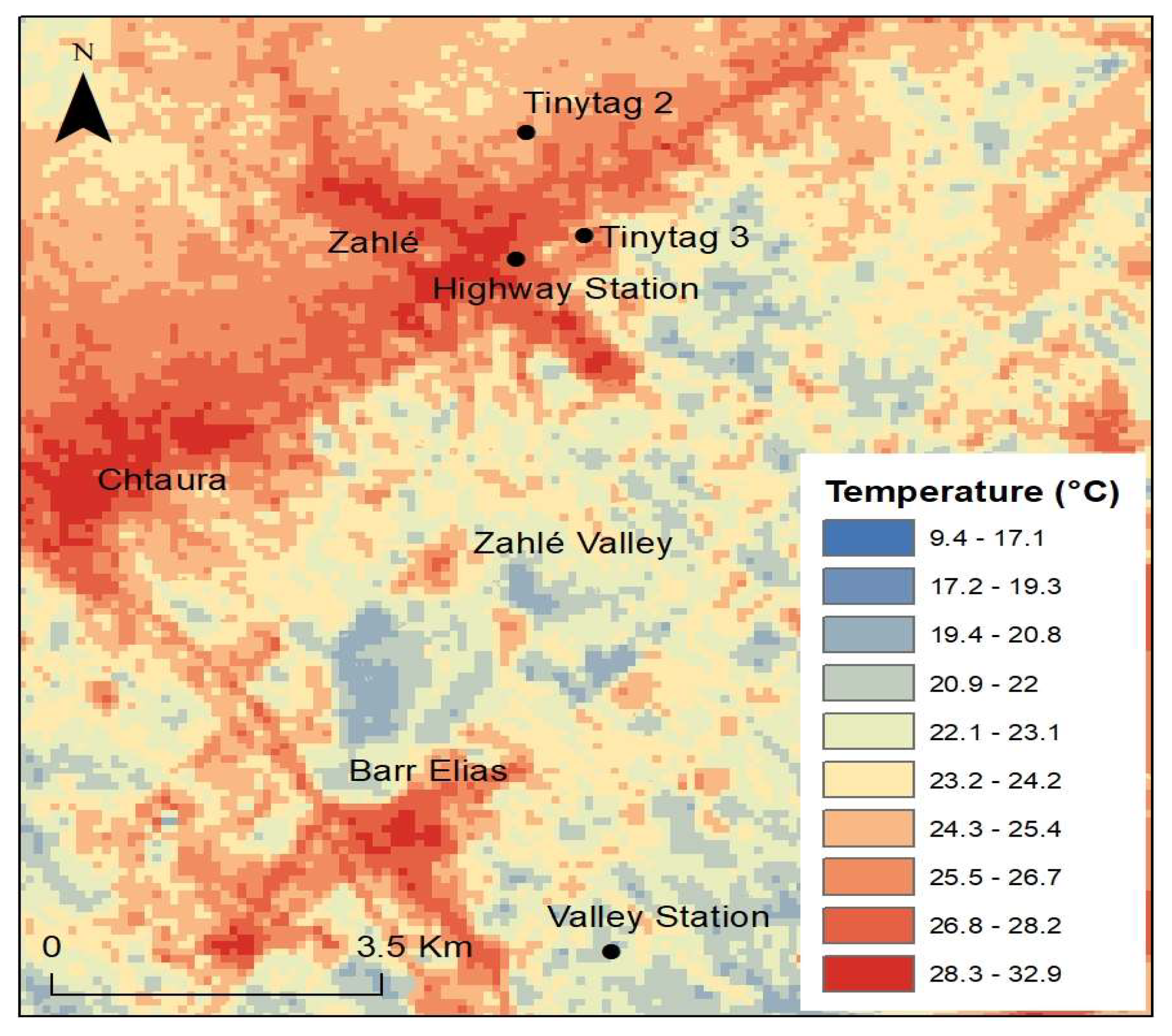

3.2.2. Urban Heat Island (UHI)

- The hottest areas (26.67-32.92°C) include the densely populated urban centers of Zahlé, Chtaura, and Barr Elias, as well as the peaks of the eastern mountain range (SE of the map). These heights, ranging between 1100 m and 1500 m in altitude, are warmer than the lower regions at the valley floor (870 m in altitude) due to nocturnal thermal inversion. Urban surfaces store heat during the day and remain relatively warm at night. The city absorbs 15 to 30% more energy than a non-urban area [37].

- The coolest areas (<24°C) correspond to the agricultural lands in the Valley, where vegetable farming still dominates. These lands do not overheat during the day due to evapotranspiration. At night, surface cooling is enhanced by the nocturnal breeze, which carries cooler air to the valley floor, as well as by the irrigation of these agricultural areas. Due to the relatively high amount of latent heat, sensible heat remains low in rural areas.

- Finally, these two zones are separated by intermediate temperature areas. This consists of an urban fabric of more or less dispersed single-family houses, including both mineralized surfaces such as roads and buildings, as well as some natural spaces like orchard-gardens and unpaved paths.

- 1.

- Zahlé agglomeration

- 2.

- Barr Elias agglomeration

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barry, R. G. Mountain weather and climate. Routledge. 2013. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780203416020/mountain-weather-climate-roger-barry.

- Whiteman, C. D. Diurnal Mountain Wind. In C. D. Whiteman (Éd.), Mountain Meteorology : Fundamentals and Applications. Oxford University Press 2000. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J. E. Sea Breeze and Local Winds. Cambridge University Press 1994.

- Carrega, P. Approches de la structure thermique et hygrométrique d’une brise de mer par mesures aéroportées. Climat, pollution atmosphérique, santé 1995. Hommage à Gisèle Escourrou, 165-175. https://pascal-francis.inist.fr/vibad/index.php?action=getRecordDetail&idt=6322224.

- Beltrando, G., Dahech, S., & Madelin, M. L’intérêt de l’étude des brises thermiques : Exemples des brises littoraux et orographiques. Bulletin de la Société géographique de Liège 2008, 51, 49-61.

- Dahech, S. Le vent à Sfax (Tunisie) : Impact sur le climat et la pollution atmosphérique. These de doctorat, Paris 7 2007. https://www.theses.fr/2007PA070002.

- Samar, S. C. Analyse de l’aérologie locale dans la région de Beyrouth durant la période estivale. ГЕОИНФОРМАЦИОННОЕ ОБЕСПЕЧЕНИЕ УСТОЙЧИВОГО РАЗВИТИЯ ТЕРРИТОРИЙ 2018, 281.

- Dahech, S. Impact de la brise de mer sur le confort thermique au Maghreb oriental durant la saison chaude. Cybergeo 2014. [CrossRef]

- Fallot, J. Etude de la ventilation de la vallée de la Sarine en Gruyère. Geographica Helvetica 1991, 46(1), 32-41. [CrossRef]

- Sakr, S. Thermal mechanisms in the wade Jamajem valley. journal of the college of basic education, وقائع المؤتمر الدولي العلمي الافتراضي الاول للعلوم الاجتماعية/الجزء الثانية/الجغرافية 2020. https://www.iasj.net/iasj/download/90997bd557164118.

- Zeinaldine, R., & Dahech, S. Topoclimatic characteristics of Zahlé (Eastern Lebanon) : Thermal breezes and urban heat island phenomenon – Preliminary results. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2023, 154(3), 1075-1098. [CrossRef]

- King, V. J., & Davis, C. A case study of urban heat islands in the Carolinas. Environmental Hazards 2007, 7(4), 353-359. [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.-W., & Cheng, W.-L. Air quality influenced by urban heat island coupled with synoptic weather patterns. Science of The Total Environment 2009, 407(8), 2724-2733. [CrossRef]

- Dettwiller, J. Deep Soil Temperature Trends and Urban Effects at Paris. Journal of Applied Meteorology (1962-1982) 1970, 9(1), 178-180.

- Oke, T. R. Boundary Layer Climates. Psychology Press 1987.

- Bourque, A. Les changements climatiques et leurs impacts. VertigO - la revue électronique en sciences de l’environnement 2000, Volume 1 Numéro 2, Article Volume 1 Numéro 2. [CrossRef]

- Oke, T. R., & Cleugh, H. A. Urban heat storage derived as energy balance residuals. Boundary-Layer Meteorology 1987, 39(3), 233-245.

- Arnfield, A. J. Two decades of urban climate research : A review of turbulence, exchanges of energy and water, and the urban heat island. International Journal of Climatology 2003, 23(1), 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Kastendeuch, P., Najjar, G., Lacarrere, P., & Colin, J. Modélisation de l’îlot de chaleur urbain à Strasbourg. Climatologie 2010, 7, 21-37. [CrossRef]

- Acero, J. A., Arrizabalaga, J., Kupski, S., & Katzschner, L. Urban heat island in a coastal urban area in northern Spain. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2013, 113(1), 137-154. [CrossRef]

- Oke, T. R., Mills, G., Christen, A., & Voogt, J. A. Urban Climates. Cambridge University Press 2017.

- Voogt, J. A., & Oke, T. R. Thermal remote sensing of urban climates. Remote Sensing of Environment 2003, 86(3), 370-384. [CrossRef]

- Masson-Delmotte, V. P., Zhai, P., Pirani, S. L., Connors, C., Péan, S., Berger, N., Caud, Y., Chen, L., Goldfarb, M. I., & Scheel Monteiro, P. M. IPCC, 2021 : Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Report]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA 2021. https://researchspace.csir.co.za/dspace/handle/10204/12710.

- Charabi, Y. L’ilôt de chaleur urbain de la métropole lilloise : Mesures et spatialisation. These de doctorat, Lille 1 2001. https://theses.fr/2001LIL10079.

- Neumann, J., & Mahrer, Y. A Theoretical Study of the Land and Sea Breeze Circulation. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 1971, 28(4), 532-542. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J. E., Mansfield, D. A., & Milford, J. R. Inland penetration of sea-breeze fronts. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 1977, 103(435), 47-76. [CrossRef]

- Borne, K., Chen, D., & Nunez, M. A method for finding sea breeze days under stable synoptic conditions and its application to the Swedish west coast. International Journal of Climatology 1998, 18(8), 901-914. [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, A., Ornelas, A., & Lameiras, J. The Thermal Regulator Role of Urban Green Spaces : The Case of Coimbra (Portugal). Forests 2023, 14, 2351. [CrossRef]

- Markham, B. L., & Barker, J. L. Radiometric properties of U.S. processed landsat MSS data. Remote Sensing of Environment 1987, 22(1), 39-71. [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, A., Rokugawa, S., Matsunaga, T., Cothern, J. S., Hook, S., & Kahle, A. B. A temperature and emissivity separation algorithm for Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) images. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 1998, 36(4), 1113-1126. [CrossRef]

- Griend, A. a. V. D., & Owe, M. On the relationship between thermal emissivity and the normalized difference vegetation index for natural surfaces. International Journal of Remote Sensing 1993, 14(6), 1119-1131. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Gong, D., Mao, R., Kim, S.-J., Xu, J., Zhao, X., & Ma, Z. Cause and predictability for the severe haze pollution in downtown Beijing in November–December 2015. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 592, 627-638. [CrossRef]

- Anquetin, S., Guilbaud, C., & Chollet, J.-P. The Formation and Destruction of Inversion Layers within a Deep Valley. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 1998, 37(12), 1547-1560. [CrossRef]

- Vitasse, Y., Klein, G., Kirchner, J. W., & Rebetez, M. Intensity, frequency and spatial configuration of winter temperature inversions in the closed La Brevine valley, Switzerland. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2017, 130(3), 1073-1083. [CrossRef]

- Mahrt, L., Richardson, S., Seaman, N., & Stauffer, D. Non-stationary drainage flows and motions in the cold pool. Tellus A: Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography 2010, 62(5), 698-705. [CrossRef]

- Michelot, N., & Carrega, P. Topoclimatogie et pollution de l’air dans les Alpes-Maritimes : Mécanismes et conséquences en images. EchoGéo 2014. [CrossRef]

- Dubreuil, V., & Marchand, J.-P. Le climat, l’eau et les hommes (p. 330). Presses Universiatires de Rennes 1997. https://hal.science/hal-00318453.

- Abutaleb, K., Ngie, A., Darwish, A., Ahmed, M., Arafat, S., & Ahmed, F. Assessment of Urban Heat Island Using Remotely Sensed Imagery over Greater Cairo, Egypt. Advances in Remote Sensing 2015, 4, 35-47. [CrossRef]

- Dahech, S., & Ghribi, M. Réchauffement climatique en ville et ses répercussions énergétiques. Méditerranée. Revue géographique des pays méditerranéens / Journal of Mediterranean geography 2017, 128, Article 128. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N., & Wang, Y. Mechanisms for the isolated convections triggered by the sea breeze front and the urban heat Island. Meteorology and Atmospheric Physics 2021, 133(4), 1143-1157. [CrossRef]

- Dahech, S., Beltrando, G., & Bigot, S. Utilisation des données NOAA-AVHRR dans l’étude de la brise thermique et de l’Ilot de chaleur. Exemple de Sfax (se tunisien). Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography 2005. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).