1. Introduction

Workplace stressors and their causes have gained significant attention in recent years due to their profound impact on employee well-being, productivity, and organizational health (CBE et al., 2014; El-Sherbeeny et al., 2023). Stressors in the workplace are defined as any aspect of the job environment or conditions that create physical, emotional, or psychological strain on employees. These stressors are often linked to a variety of factors, including excessive workload, lack of autonomy, unclear job expectations, poor organizational communication, and insufficient resources (Tamunomiebi & Mezeh, 2021). Interpersonal conflicts, toxic work environments, and job insecurity further amplify stress levels among employees. Technological advancements have also contributed to stress, with the pressure to remain constantly connected and responsive outside traditional working hours (Lee et al., 2018; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016). Moreover, organizational changes, such as restructuring or downsizing, can exacerbate anxiety and uncertainty among the workforce. The increasing focus on workplace stressors stems from their detrimental effects on employee health, such as burnout, anxiety, depression, and chronic illnesses, which in turn impact productivity, absenteeism, and overall organizational performance (Cmiosh, 2024; El-Sherbeeny et al., 2023). As a result, employers and researchers are emphasizing the identification, assessment, and management of these stressors through strategies such as improved job design, enhanced communication, stress management training, and fostering a supportive work culture. This growing interest underscores the necessity for proactive measures to address workplace stress, ultimately ensuring sustainable employee well-being and organizational success (Zaki & Al-Romeedy, 2018).

Workplace stressors have a profound and multifaceted impact on employees, influencing their intention to quit, psychological distress, and psychological flexibility (Emerson et al., 2023). Chronic exposure to stressors such as excessive workloads, role ambiguity, micromanagement, lack of recognition, and interpersonal conflicts often leave employees feeling overwhelmed and undervalued (George, 2023). These stressors erode job satisfaction and organizational commitment, prompting many employees to consider leaving their jobs. Intention to quit often arises when individuals feel that their well-being, growth, or professional aspirations are being compromised due to unresolved stressors in the workplace (Alphy et al., 2023).

Additionally, workplace stressors are closely tied to heightened psychological distress, which encompasses feelings of anxiety, depression, frustration, and emotional exhaustion. The constant pressure to meet unrealistic expectations or deal with toxic environments creates an emotional toll that affects employees’ mental health and resilience. This psychological distress not only hampers productivity and job performance but also intensifies dissatisfaction, making the idea of quitting more appealing (McCormack & Cotter, 2013). Moreover, sustained exposure to workplace stress undermines psychological flexibility—the ability to adapt effectively to challenges, regulate emotions, and stay aligned with personal and professional goals (Archer et al., 2024; Chan & Wan, 2012). Employees with diminished psychological flexibility are more likely to become rigid in their thinking, less open to change, and less capable of finding creative solutions to workplace challenges. This reduction in adaptability further fuels their intention to quit, as the workplace becomes a source of persistent struggle rather than an environment conducive to growth and success (Putnam et al., 2014).

Psychological distress plays a significant role in shaping employees’ intentions to leave their jobs. Employees experiencing high levels of distress often feel drained, both mentally and emotionally, making it difficult for them to sustain their engagement and commitment to their roles (Afshar et al., 2022; Maslach & Leiter, 2016). This distress creates a negative perception of their work environment, leading them to view their current job as untenable or damaging to their overall well-being. The cumulative effect of stress-induced emotions, such as frustration, hopelessness, and disengagement, fosters a desire to seek relief through job change or resignation (Molino et al., 2019; Khairy et al., 2023).

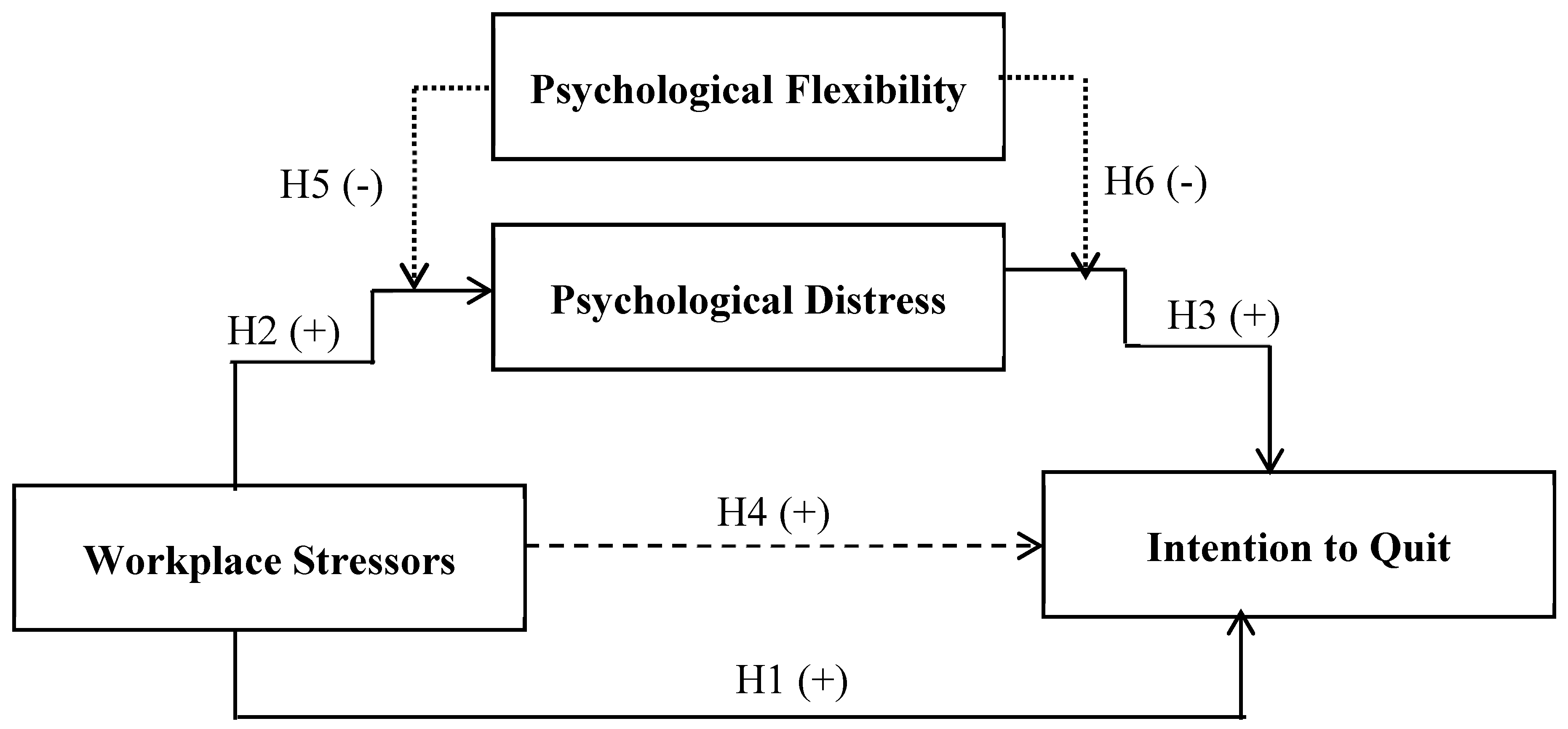

The relationship between workplace stressors, psychological distress, and the intention to quit is intricately connected, forming a cascade where stressors trigger distress, which, if unaddressed, leads to dissatisfaction and a strong desire to leave. This dynamic is particularly pronounced among male hospitality and tourism workers, who face unique stressors such as long hours, customer-facing roles, and fluctuating demands compounded by societal expectations of resilience. While the link between workplace stress and turnover intentions is acknowledged, significant gaps remain in understanding the direct effects of stressors on distress and psychological flexibility, particularly in this male-dominated context. The mediating role of psychological distress, which connects stressors to turnover intentions, requires further exploration to clarify how addressing distress might weaken this link and improve retention. Additionally, the potential moderating role of psychological flexibility, a critical yet underexplored variable, merits investigation to determine its ability to buffer the impact of stressors and reduce distress and turnover. Gender-specific insights are another overlooked area, as most research focuses on mixed-gender samples or female-dominated roles, leaving the unique stressors, coping mechanisms, and responses of male workers underexplored. In Egypt’s sociocultural context, men are often expected to be the primary breadwinners, which subjects them to heightened pressure to endure job-related stress without complaint; combined with the hospitality sector’s demanding conditions and the country’s gendered labor dynamics, male workers face a unique confluence of stressors that merits focused investigation. Addressing these gaps through targeted research can provide actionable solutions, such as tailored interventions, to mitigate stress, enhance psychological resilience, and promote employee retention in high-stress industries such as hospitality and tourism. In this vein, this study aims to (A) assess the direct effect of workplace stressors on the intention to quit, psychological distress, and psychological flexibility, (B) explore the mediating role of psychological distress in the link between workplace stressors and the intention to quit, (C) examine the moderating role of psychological flexibility in the link between workplace stressors and psychological distress, and (D) investigate the moderating role of psychological flexibility in the link between workplace stressors and the intention to quit.

This study makes significant contributions by providing a deeper understanding of the unique experiences of male hospitality and tourism workers regarding workplace stressors, psychological distress, psychological flexibility, and their influence on the intention to quit. It offers novel insights into the mediating role of psychological distress and the moderating role of psychological flexibility, enriching the theoretical frameworks in occupational psychology and human resource management. Additionally, the research informs the development of targeted, evidence-based interventions to mitigate stress, enhance resilience, and reduce turnover rates in this high-stress industry. These contributions will help organizations create healthier work environments and improve employee retention, ultimately enhancing operational efficiency and workforce well-being.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Transactional Model of Stress and Coping

The transactional model of stress and coping provides a robust theoretical framework to examine the relationships among workplace stressors, psychological distress, psychological flexibility, and the intention to quit, as outlined in this study focusing on male hospitality and tourism workers. This model emphasizes that stress arises not only from external stressors but also from an individual’s appraisal of these stressors and their perceived ability to cope (Dillard, 2019). It views stress as a dynamic interaction between the person and their environment, making it highly relevant for understanding the workplace dynamics in the hospitality and tourism sector (Zaki & Al-Romeedy, 2018; El-Sherbeeny et al., 2023). Workplace stressors in this industry, such as demanding schedules, interpersonal conflicts, and job insecurity, often create high-pressure environments (Mustafa et al., 2015).

According to the model, stress occurs when these stressors are appraised as threatening during the primary appraisal process (Aliane et al., 2023). Male hospitality and tourism workers may perceive these stressors as particularly challenging due to societal pressures and cultural expectations of resilience and stoicism (Zaki & Al-Romeedy, 2018). If, during the secondary appraisal, they feel they lack adequate coping resources—such as organizational support or personal resilience—this perception of imbalance leads to psychological distress (Heath et al., 2020; Labrague & de Los Santos, 2021). The model helps explain how these cognitive appraisals transform external workplace demands into internal emotional and psychological strain (Agina et al., 2023). Psychological distress, a core focus of this study, aligns with the model’s outcomes of ineffective stress appraisal and coping (Spătaru et al., 2024).

When workers are unable to manage or adapt to the demands of their jobs, they experience heightened levels of anxiety, frustration, or burnout (McCormack & Cotter, 2013). In the context of this study, psychological distress acts as a mediator between workplace stressors and the intention to quit (Baquero, 2023). Workers may interpret quitting as the only viable coping strategy when they perceive their work environment as unmanageable and their mental well-being as compromised. This decision reflects the outcome of coping described in the model, where leaving the organization becomes an effort to escape an overwhelming situation (Alphy et al., 2023).

This study also highlights the importance of psychological flexibility as a moderating factor, which aligns with the model’s emphasis on coping mechanisms. Psychological flexibility enhances an individual’s ability to adjust their responses to stressors, stay focused on their long-term values, and reframe challenges in a more adaptive way (Dawson & Golijani-Moghaddam, 2020). Male hospitality and tourism workers with higher psychological flexibility are better equipped to appraise stressors as manageable and to adopt positive coping strategies, reducing their psychological distress and lowering their intention to quit. In contrast, workers with lower psychological flexibility may adopt rigid coping approaches, viewing quitting as the only solution to escape their stress (Baquero, 2023; Khairy et al., 2023).

2.2. The Effect of Workplace Stressors on the Intention to Quit

Workplace stressors play a critical role in shaping employees’ intention to quit, particularly in demanding industries such as hospitality and tourism. These stressors, which include excessive workloads, lack of role clarity, interpersonal conflicts, and inadequate resources, create a challenging work environment that can overwhelm employees (El-Sherbeeny et al., 2023; Kusluvan, 2003). When workers perceive these stressors as persistent and unmanageable, they begin to feel dissatisfied with their jobs and disconnected from their organizations (Maslach & Leiter, 2022). This dissatisfaction serves as a primary driver of turnover intentions, as employees seek relief from the stress-laden environment by considering alternative employment opportunities (Aliane et al., 2023). One of the most significant pathways through which workplace stressors influence the intention to quit is through their psychological impact (Park et al., 2017). Persistent exposure to stressors often leads to emotional exhaustion, mental fatigue, and burnout, particularly in high-stress roles within hospitality and tourism (Yoo, 2023; El-Sherbeeny et al., 2024).

Employees who are emotionally depleted struggle to maintain their productivity and engagement, and the workplace begins to feel like a source of strain rather than a space for growth. The constant demands of dealing with difficult customers, long hours, and unpredictable schedules further exacerbate these effects, making quitting an appealing solution to escape from the cycle of stress (Maslach & Leiter, 2022; Al-Romeedy, 2019). Workplace stressors also undermine employees’ perception of organizational support and fairness. When employees feel that their concerns about excessive workloads or toxic workplace dynamics are ignored or that their efforts are not adequately recognized, their trust in the organization diminishes (Zhang et al., 2014; Agina et al., 2023). A lack of managerial responsiveness to employee needs fosters feelings of alienation and resentment. In such scenarios, employees may perceive quitting as the only way to regain a sense of control over their well-being and professional lives. This breakdown in the employee–organization relationship significantly contributes to turnover intentions (Bailey et al., 2017; Zaki & Al-Romeedy, 2018). Hence, the following hypothesis is adopted:

H1. Workplace stressors positively affect the intention to quit.

2.3. The Effect of Workplace Stressors on Psychological Distress

Workplace stressors have a profound and direct effect on psychological distress, significantly influencing employees’ mental and emotional well-being. These stressors, such as excessive workloads, role ambiguity, interpersonal conflicts, and lack of resources, create a challenging environment that demands constant adaptation (Fordjour et al., 2020). When employees perceive these demands as exceeding their capacity to cope, it triggers feelings of anxiety, frustration, and helplessness. Over time, the cumulative impact of these stressors heightens psychological distress, leaving employees vulnerable to emotional and cognitive strain that affects their overall functioning (Khairy et al., 2023).

A key mechanism through which workplace stressors induce psychological distress is their persistence and intensity. Chronic exposure to high levels of stress creates a state of emotional exhaustion, where employees feel drained and unable to recover. This condition is particularly prevalent in industries such as hospitality and tourism, where fast-paced and unpredictable work environments amplify the effects of stressors (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2015; Maslach & Leiter, 2016). Employees in such settings often experience a constant sense of being overwhelmed, leading to irritability, difficulty concentrating, and a pervasive sense of unease. These emotional reactions are hallmarks of psychological distress, directly linked to the unrelenting demands of their work environment (Van Heugten, 2011; Agina et al., 2023). Interpersonal stressors, such as conflicts with colleagues or lack of support from supervisors, further exacerbate psychological distress (Somaraju et al., 2022).

When employees face strained workplace relationships, it undermines their sense of belonging and trust within the organization (Schein & Schein, 2018). This social disconnection compounds the emotional burden of stressors, as employees may feel isolated and unsupported in their efforts to manage challenges. The result is an intensification of distress, characterized by feelings of loneliness, resentment, and diminished morale, which further erodes their ability to perform and cope effectively (El-Sherbeeny et al., 2023). So, the following hypothesis is adopted:

H2. Workplace stressors positively affect psychological distress.

2.4. The Effect of Psychological Distress Positively Affects the Intention to Quit

Psychological distress has a strong positive effect on employees’ intention to quit, as it significantly undermines their mental well-being and job satisfaction (Hussain et al., 2020). When employees experience psychological distress, characterized by feelings of anxiety, frustration, and emotional exhaustion, they often perceive their work environment as a primary source of their discomfort (Emam & Abdel Majeed, 2024; Al-Romeedy, 2019). This association creates a desire to escape the distressing conditions, making quitting the job an increasingly appealing option. The emotional toll of distress reduces employees’ capacity to engage with their work, fostering disconnection and dissatisfaction that ultimately influence their decision to leave (Giao et al., 2020; Aliane et al., 2023).

One of the ways psychological distress drives the intention to quit is through its impact on job satisfaction. Distressed employees often find it difficult to derive meaning or fulfillment from their work, as their focus shifts from achieving goals to merely coping with their emotional strain. Over time, this dissatisfaction grows, leading employees to view their current role as incompatible with their personal and professional needs (Xue et al., 2022; Ross, 2017). For example, in industries such as hospitality and tourism, where emotional labor is a constant demand, psychological distress exacerbates feelings of being overwhelmed and undervalued, further intensifying the desire to resign (Khairy et al., 2023).

Additionally, psychological distress impairs employees’ ability to maintain positive workplace relationships, which can influence their intention to quit (Hebles et al., 2022). Distressed employees may become less communicative, more irritable, or less effective in resolving conflicts, leading to strained interactions with colleagues and supervisors (Hagemeister & Volmer, 2018). These deteriorating relationships can leave employees feeling isolated and unsupported in the workplace. This social disconnection reinforces their perception of the work environment as a source of harm rather than support, pushing them closer to the decision to leave (Alphy et al., 2023). Therefore, the following hypothesis is suggested:

H3. Psychological distress positively affects the intention to quit.

2.5. The Mediating Role of Psychological Distress in the Link Between Workplace Stressors and the Intention to Quit

Psychological distress plays a critical mediating role in the relationship between workplace stressors and employees’ intention to quit by acting as the psychological mechanism that connects the external pressures of stressors to the internal decision-making process regarding turnover. Workplace stressors, such as excessive workloads, role ambiguity, and interpersonal conflicts, create an environment that overwhelms employees and triggers psychological distress (Agina et al., 2023). This distress, characterized by emotional exhaustion, anxiety, and frustration, emerges as a direct consequence of these stressors and significantly shapes how employees perceive their work environment and evaluate their options, including leaving their job (Maslach & Leiter, 2016; Zaki & Al-Romeedy, 2018). Employees exposed to persistent stressors are likely to experience heightened distress, which undermines their ability to find satisfaction or meaning in their work (El-Sherbeeny et al., 2023). This distress erodes their motivation and commitment, leading them to view the workplace as a source of harm rather than a place of growth or stability (Leiter, 2013). In this way, psychological distress serves as the pathway through which workplace stressors negatively influence an employee’s emotional and cognitive connection to their job, driving their intention to quit (Harmsen et al., 2018; Shaukat et al., 2017). Distressed employees are also less likely to view stressors as manageable or temporary and more likely to feel overwhelmed and incapable of meeting job demands (Abdelrahman & Emam, 2022). This diminished coping ability intensifies feelings of helplessness and dissatisfaction, further reinforcing the link between workplace stressors and the decision to leave. As a result, psychological distress becomes a crucial factor that bridges the external pressures of stressors and the behavioral outcome of turnover intentions (Nazari & Alizadeh Oghyanous, 2021; Emam & Abdel Majeed, 2024; Aliane et al., 2023). Accordingly, the following hypothesis is developed:

H4. Psychological distress mediates the link between workplace stressors and the intention to quit.

2.6. The Moderating Role of Psychological Flexibility in the Link Between Workplace Stressors and Psychological Distress

Psychological flexibility plays a critical moderating role in the relationship between workplace stressors and psychological distress by influencing how employees perceive and respond to stress-inducing situations (Haldorai et al., 2023; Balducci et al., 2024).

Psychological distress affects how employees perceive their ability to cope with workplace challenges (Giorgi et al., 2015). When overwhelmed by distress, employees may lose confidence in their skills and feel incapable of meeting organizational demands (Drapeau et al., 2012). This perception amplifies feelings of dissatisfaction and triggers a survival response, where quitting becomes a rational option to escape the stressor-laden environment. Furthermore, unresolved psychological distress often impacts interpersonal relationships at work, exacerbating feelings of isolation and alienation, which further contribute to the intention to quit. In many cases, employees believe that leaving their current position is the only way to restore their mental health and regain control over their lives (Zaki & Al-Romeedy, 2018).

As a personal resource, psychological flexibility allows individuals to adapt their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors to effectively manage workplace demands, even in the presence of significant stressors (Fuchs et al., 2023). Employees with high psychological flexibility are better equipped to handle challenges without becoming overwhelmed, as they can reframe stressors, accept difficult emotions, and maintain focus on their values and goals. This ability helps to buffer the impact of workplace stressors on psychological distress (Zaki & Al-Romeedy, 2018). Furthermore, psychological flexibility mitigates the effect of workplace stressors on distress by enhancing emotional regulation (Russo et al., 2024). Employees with greater flexibility are more adept at recognizing and accepting their emotions without letting them dictate their actions (Emam & Abdel Majeed, 2024; Agina et al., 2023). For instance, in a high-stress environment such as hospitality and tourism, flexible employees may acknowledge feelings of frustration or anxiety without allowing these emotions to interfere with their ability to perform or engage with others. This emotional resilience acts as a protective factor, reducing the likelihood that workplace stressors will lead to anxiety, frustration, or burnout (Mohd-Shamsudin et al., 2024; Al-Romeedy, 2019).

On the other hand, employees with low psychological flexibility are more vulnerable to workplace stressors because they are less able to adapt to changing demands or regulate their emotional responses (Atkins & Parker, 2012). These individuals are more likely to perceive stressors as overwhelming, leading to heightened psychological distress (Ross, 2017). They may struggle to separate their emotional reactions from their actions, which can exacerbate feelings of anxiety and helplessness. Thus, the moderating role of psychological flexibility highlights its importance as a key factor that determines whether workplace stressors translate into psychological distress or are effectively managed (Abdelrahman & Emam, 2022). Hence, the following hypothesis is postulated:

H5. Psychological flexibility moderates the link between workplace stressors and psychological distress.

2.7. The Moderating Role of Psychological Flexibility in the Link Between Workplace Stressors and the Intention to Quit

Psychological flexibility plays a crucial moderating role in the relationship between workplace stressors and employees’ intention to quit by influencing how employees process and respond to the challenges they face. Workplace stressors, such as excessive workloads, role ambiguity, and interpersonal conflicts, often lead to frustration and dissatisfaction, increasing the likelihood of turnover intentions (Mansour & Tremblay, 2018; Emam & Abdel Majeed, 2024). However, employees with high psychological flexibility are better equipped to manage these stressors effectively, reducing their impact on the decision to quit. By enabling individuals to adapt their thinking and behavior to align with long-term goals, psychological flexibility helps mitigate the negative effects of stressors on employees’ attitudes toward their jobs and organizations (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010; Khairy et al., 2023).

Additionally, psychological flexibility enhances emotional regulation, which plays a pivotal role in moderating turnover intentions. Employees with high flexibility are better able to manage negative emotions, such as frustration or anxiety, that often accompany workplace stressors (Shao et al., 2022; Bakker & de Vries, 2021). Instead of allowing these emotions to dominate their decision making, they focus on their broader goals and values, such as career development or financial stability. This ability to maintain perspective despite stressors decreases the likelihood of impulsive decisions to quit, even in challenging work environments (Greenhaus et al., 2009; Al-Romeedy, 2019).

In contrast, employees with low psychological flexibility are more susceptible to the negative effects of workplace stressors, as they are less able to adapt or manage their emotional responses. These individuals may perceive stressors as insurmountable and experience heightened dissatisfaction, leading to stronger turnover intentions (Ramaci et al., 2019; Emam & Abdel Majeed, 2024). Without the capacity to reframe or cope with challenges, the connection between workplace stressors and the decision to quit becomes more direct and pronounced. Thus, psychological flexibility serves as a protective factor, moderating the relationship by reducing the extent to which workplace stressors influence employees’ decisions to leave their jobs (McCormack & Cotter, 2013; El-Sherbeeny et al., 2023). So, the following hypothesis is suggested:

H6. Psychological flexibility moderates the link between workplace stressors and the intention to quit.

The theoretical framework of the study is illustrated below in

Figure 1.

3. Methods

3.1. Measures

A quantitative approach was used to collect data. A structured survey was conducted to examine the impact of workplace stressors on male hospitality workers’ intention to quit, focusing on the roles of psychological distress and psychological flexibility. All variables were measured using established scales adapted from previous research and assessed on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Workplace stressors were measured with a four-item scale adapted from Mahmood et al. (2010). The intention to quit was evaluated using a six-item scale from Baquero (2022) and Treglown et al. (2018). Psychological distress was assessed with a six-item scale based on Massé et al. (1998) and Baquero (2023), and psychological flexibility was measured with a six-item scale developed by Gloster et al. (2021). A complete list of these measurement items is provided in

Table 1.

The study utilized a self-administered questionnaire. The original English version was translated into Arabic by a bilingual expert and then back-translated into English by a second bilingual professional to ensure accuracy. The original and back-translated versions were compared for consistency. Since the translations aligned, the Arabic version of the questionnaire was used with participants to enhance the clarity and improve the response rates.

3.2. Data Collection

The study model was assessed using data from full-time employees at five-star hotels in Egypt, chosen for their prominent role within the country’s hospitality sector. These hotels are ideal for the study due to the high-pressure nature of their work environments, characterized by demanding customer expectations, long working hours, and emotionally taxing tasks. These conditions expose employees to significant stressors, increasing the likelihood of psychological distress and a higher intention to quit. The hospitality industry’s high turnover rate further supports the exploration of factors influencing employees’ decision to leave. Additionally, studying male employees in this context provides valuable insights into how gender-specific stressors and coping mechanisms affect psychological flexibility, thereby contributing to a deeper understanding of the relationship between workplace stress, distress, and turnover intentions.

In Egypt, male dominance in the workplace remains prevalent, with women participating in the labor force at relatively low rates of 20% to 25% (Nazier & Ramadan, 2016). Sociocultural factors such as poor working conditions, limited opportunities, exploitation, violence, and harassment intensify these challenges for workers, particularly in the hospitality sector.

A quantitative research design was used, with a survey methodology targeting employees who had at least one year of experience at five-star hotels in Greater Cairo. The one-year experience requirement ensured participants had sufficient exposure to the work environment to provide meaningful insights. According to Morrison (1993), employees typically gain a good understanding of an organization’s culture within six months, making this duration appropriate for the study.

Data were collected from employees across 22 five-star hotels in Greater Cairo during January and February 2025. In 2022, the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities listed 30 five-star hotels in this region. A judgmental sampling approach was employed to select the hotels, while a convenience sampling method was used to gather responses from voluntarily participating employees. The survey was administered after obtaining verbal consent from hotel management, with employee participation remaining voluntary and anonymous to ensure confidentiality.

In total, 334 valid responses were collected, surpassing the recommended minimum sample size of 220 respondents (Hair et al., 2010), based on a 1:10 ratio of variables to respondents. This sample size was deemed sufficient for the analysis.

3.3. Data Analysis

The study used partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) for data analysis, a widely adopted method for both confirmatory and exploratory research. PLS-SEM is particularly effective for theory validation and model extension, making it ideal for analyzing complex relationships (Hair et al., 2014). This technique is commonly used in strategic and management studies, including research in hospitality and tourism. (Ali et al., 2018). Data processing was performed using WarpPLS statistical software, version 7.0.

To assess non-response bias, t-tests were conducted comparing early and late responses (p > 0.05), revealing no significant differences, which indicates that non-response bias was not a concern. Additionally, to evaluate the common method variance (CMV), the study employed Harman’s single-factor test and principal component analysis. The results showed that no single factor explained more than 50% of the total variance, suggesting that CMV was not a significant issue in this study.

4. Results

4.1. Participant’s Profile

Table 2 presents the demographic and work-related characteristics of the 334 participants. Most participants were aged 36–55 years (59.88%) and held a bachelor’s degree (82.04%). The majority were married (59.58%), with a smaller proportion being single (38.62%) and divorced (1.80%). Regarding tenure, most participants had been in their current roles for more than 6 years (43.71%), followed by those with 1–3 years (29.64%) and 4–6 years (26.65%).

4.2. Measurement Model

The evaluation of the four-factor model, which includes workplace stressors (WS), psychological distress (PD), intention to quit (ITQ), and psychological flexibility (PF), was conducted using Kock’s (2021) ten fit indices. All the criteria used for assessment were found to be supported (See

Appendix A). All indices met their respective acceptance thresholds, confirming the model’s robustness and validity across multiple dimensions.

Table 1 reveals that all the constructs showed acceptable reliability and convergent validity, as indicated by their composite reliability (CR), Cronbach’s alpha (CA), and average variance extracted (AVE) values. The variance inflation factors (VIF) were within acceptable limits, suggesting that multicollinearity was not a significant issue. This suggests that the measurement model is valid and reliable.

Table 3 presents the discriminant validity results using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, which compares the square root of the AVE for each construct with the correlations between constructs. Discriminant validity is established when the square root of a construct’s AVE is greater than its correlation with other constructs. The results confirmed that all constructs showed sufficient discriminant validity because the square roots of their AVE values were greater than their correlations with other constructs. This suggests that each construct is distinct and measures a unique aspect of the model.

Table 4 presents the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratios and corresponding p-values, which are used to assess discriminant validity between constructs. A ratio below 0.85 is considered excellent, and values below 0.90 are acceptable for demonstrating discriminant validity. The p-values for HTMT ratios should be less than 0.05 to confirm that the constructs are distinct. The HTMT ratios for all construct pairs were well below the thresholds of 0.90 (and most were below 0.85), indicating that the constructs were sufficiently distinct. The p-values confirmed the significance of these ratios, strengthening the evidence for discriminant validity across the constructs.

4.3. Structural Model and Results of Testing Hypotheses

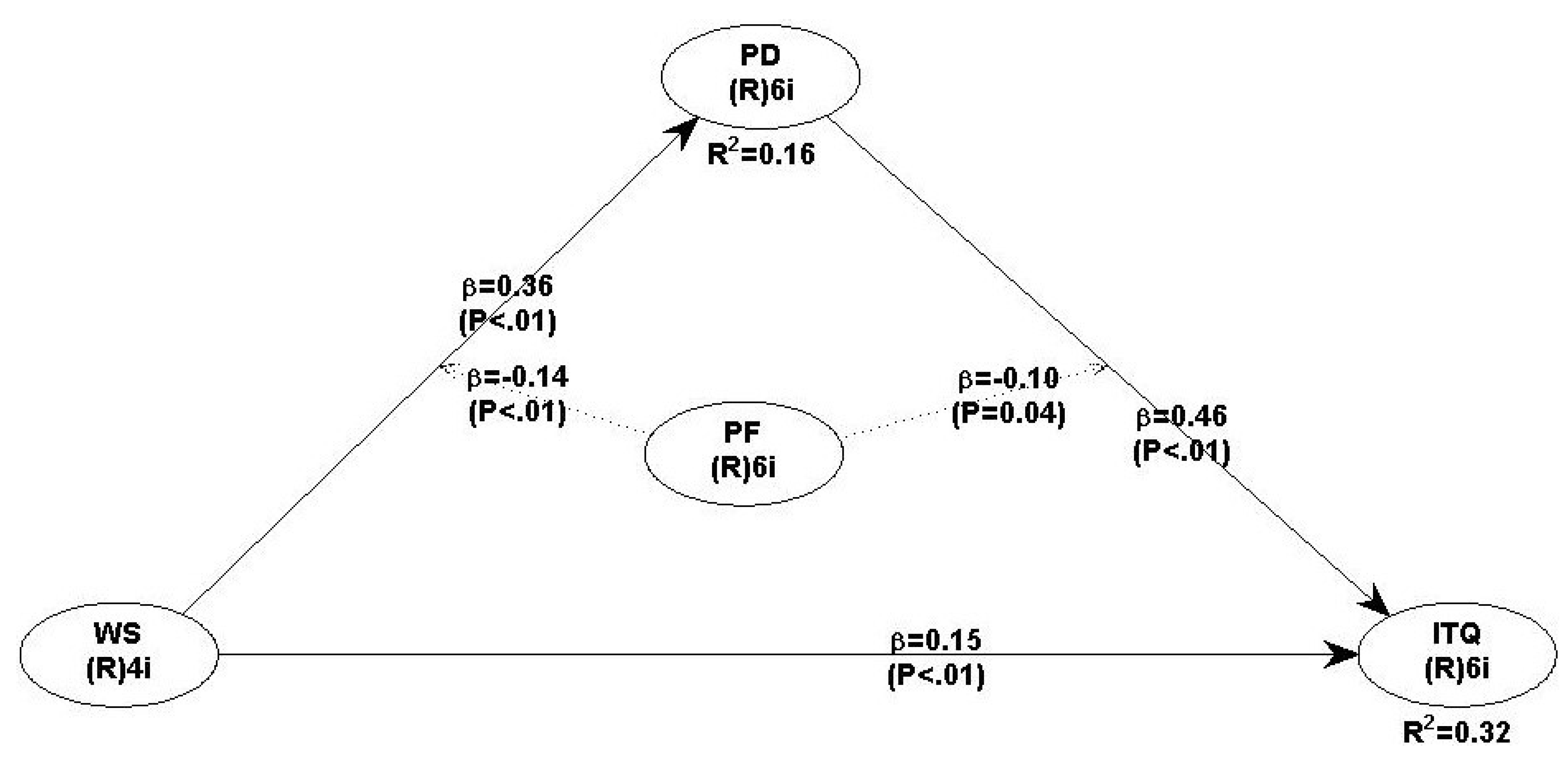

Figure 2 and

Table 5 provide a summary of the direct and moderating effects among the hypothesized relationships involving WS, PD, ITQ, and PF. As depicted in

Figure 2, WS is positively correlated with both ITQ (β = 0.15,

p < 0.01) and PD (β = 0.36,

p < 0.01), indicating that WS contributes to an increase in both ITQ and PD, thereby supporting Hypotheses H1 and H2.

Additionally, PD is positively correlated with ITQ (β = 0.46, p < 0.01), suggesting that higher levels of PD lead to an increase in ITQ, thus supporting Hypothesis H3.

Furthermore, the relationships between WS and PD, as well as between PD and ITQ, are moderated by PF. Specifically, PF dampens the positive correlation between WS and PD (β = −0.14, p < 0.01) and between PD and ITQ (β = −0.10, p = 0.04), providing support for Hypotheses H5 and H6.

Furthermore, the mediation effect in this study was assessed using the method developed by Preacher and Hayes (2008), a widely recognized statistical technique for evaluating mediation. This approach effectively demonstrated how psychological distress (PD) mediates the relationship between workplace stressors (WS) and the intention to quit (ITQ). The results presented in

Table 6 support Hypothesis H4, confirming that PD significantly mediates the relationship between WS and ITQ. The mediation effect is considered significant, as the bootstrapped confidence interval does not include zero.

According to Cohen’s (1988) guidelines, effect sizes (f

2) are classified as follows: values of f

2 ≥ 0.02 indicate a small effect, f

2 ≥ 0.15 represent a medium effect, and f

2 ≥ 0.35 signify a large effect. In reference to

Table 7, workplace stressors (WS) have a small effect on the intention to quit (ITQ) (f

2 = 0.052), while psychological distress (PD) exhibits a medium effect on ITQ (f

2 = 0.242). The interaction between psychological flexibility (PF) and PD also has a small effect on ITQ (f

2 = 0.021). Conversely, WS demonstrates a medium effect on PD (f

2 = 0.137), while the interaction between PF and WS on PD shows a small effect (f

2 = 0.028).

5. Discussion

This study explored the impact of workplace stressors on employees’ intention to quit, with a specific focus on the role of psychological distress as a mediator and psychological flexibility as a moderator. The findings revealed that workplace stressors have a positive impact on employees’ intention to quit, consistent with the results of Jasiński and Derbis (2022). Stressors often reduce employees’ ability to view their roles positively or envision long-term career growth within the organization (Ren et al., 2024). When the workplace environment is characterized by high stress and low support, employees may no longer see value in staying with the organization (Agina et al., 2023). This perception not only erodes their engagement but also pushes them to seek environments that offer better working conditions and greater personal satisfaction. Ultimately, the cumulative effects of workplace stressors on psychological health, organizational trust, and career outlook make the intention to quit a likely outcome for many employees in high-stress industries such as hospitality and tourism (Alphy et al., 2023).

The findings also indicated that workplace stressors positively affect psychological distress, which aligns with the results of Lorente et al. (2021). Workplace stressors that threaten an employee’s sense of stability or predictability can heighten psychological distress by creating feelings of uncertainty and insecurity (Lin et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2018). For example, unclear job roles or frequent changes in organizational policies disrupt employees’ sense of control, leaving them feeling vulnerable and anxious. This lack of clarity often leads to hypervigilance and rumination, where employees dwell on potential negative outcomes. These cognitive processes amplify the psychological impact of stressors, making it harder for employees to maintain emotional balance and further deepening their distress (Abdelrahman & Emam, 2022).

Additionally, the findings showed that psychological distress positively impacts employees’ intention to quit, consistent with the results of Labrague and de Los Santos (2021). Psychological distress reduces employees’ ability to cope with workplace challenges, making quitting seem like the most viable solution to protect their mental health. Distressed employees often experience reduced resilience and an inability to manage additional stressors, amplifying the perception that their current job is unmanageable (Abdelrahman & Emam, 2022). This diminished capacity for coping can result in a cycle where distress leads to withdrawal behaviors, such as disengagement and absenteeism, which eventually culminate in the decision to quit. The pervasive influence of psychological distress highlights its critical role in shaping employees’ turnover intentions (Milne, 2013; Wong et al., 2024).

Moreover, the findings showed that psychological distress mediates the link between workplace stressors and the intention to quit. The mediating role of psychological distress highlights its central function in converting workplace stressors into actionable outcomes, such as quitting (St-Jean et al., 2023; Allisey et al., 2014). Rather than stressors directly causing employees to leave, it is the psychological toll these stressors impose that drives the decision-making process (Thompson, 2010). This underscores the importance of understanding psychological distress not merely as a byproduct of workplace stressors but as a key mechanism that shapes employees’ responses to stress and their subsequent career decisions. This mediation pathway provides valuable insight into the complex dynamics between stressors, mental health, and turnover intentions (El-Sherbeeny et al., 2023).

Lastly, the findings revealed that psychological flexibility moderates the link between workplace stressors and psychological distress and the link between workplace stressors and the intention to quit. The moderating effect of psychological flexibility is evident in how it shapes employees’ cognitive appraisals of workplace stressors. Flexible employees are more likely to perceive stressors as manageable or temporary rather than as insurmountable threats (Boss et al., 2016; Aliane et al., 2023). An employee with high psychological flexibility may view excessive workload not as a failure of their abilities but as an opportunity to improve time management or seek support. This perspective reduces the emotional strain typically associated with stressors, preventing escalation to psychological distress (Slowiak & Jay, 2023; Abdelrahman & Emam, 2022). Furthermore, flexible employees are more likely to view stress-inducing situations as temporary or manageable rather than as overwhelming barriers (Abdelrahman & Emam, 2022). For example, an employee facing a demanding workload may recognize the opportunity to develop new skills or seek collaborative solutions rather than perceiving the situation as a reason to leave (Maslach & Leiter, 2022; Alphy et al., 2023). This adaptive mindset reduces the emotional burden of stressors, weakening the link between stress and the intention to quit (Agina et al., 2023).

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The study highlights the significant impact of workplace stressors on the intention to quit and psychological distress among male hospitality and tourism workers, directly supporting the transactional model of stress and coping. The model’s core premise of stress appraisal is validated, as workplace stressors such as long hours and customer complaints are often appraised as overwhelming, triggering psychological distress. This distress influences secondary appraisals, where quitting can be perceived as the only viable coping strategy. By showing that stressors lead to both distress and higher turnover intentions, the study demonstrates how external demands and internal appraisals jointly shape psychological and behavioral outcomes.

Psychological flexibility, a key resource for adaptive coping, allows individuals to reframe stressors and respond effectively. However, persistent and overwhelming stressors erode this flexibility, reducing the capacity to manage stress adaptively and creating a cycle of vulnerability to stress. This finding underscores how workplace stressors deplete internal resources, weakening individuals’ ability to cope with future challenges.

The study confirms that psychological distress positively affects the intention to quit, emphasizing the model’s focus on stress outcomes. Distress, reflecting a failure to cope with stressors, leads employees to perceive their work environment as intolerable, driving withdrawal behaviors such as quitting. This mediating role of distress clarifies the pathway between stressors and turnover, highlighting distress as a critical bridge between environmental demands and behavioral responses. Finally, psychological flexibility is shown to moderate the relationship between workplace stressors and both distress and intention to quit. Employees with higher flexibility can appraise stressors as manageable and employ effective coping strategies, reducing distress and mitigating turnover intentions. These findings enhance the model’s explanatory power by incorporating mediating and moderating effects, offering deeper insights into workplace dynamics in high-stress industries such as hospitality and tourism.

5.2. Practical Implications

The findings of this study have important practical implications for improving workplace environments, reducing employee turnover, and enhancing overall well-being in the hospitality and tourism sector. Organizations should focus on mitigating workplace stressors by addressing their root causes. This involves fair workload distribution, clear job descriptions, and the provision of adequate resources and support to employees. Managers could be trained to adopt supportive leadership styles, foster open communication, and manage interpersonal conflicts effectively. Reducing workplace stressors at their source can significantly lower employee psychological distress and reduce the likelihood of turnover.

Promoting psychological flexibility is another critical strategy for organizations. Psychological flexibility enables employees to adapt to challenges, regulate their emotions, and stay focused on their values and goals despite stressors. Employers can implement training programs, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) or acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), to help employees develop these skills. By fostering psychological flexibility, organizations can reduce the impact of workplace stressors on employees’ mental health and their intention to quit, thereby improving resilience and retention.

Organizations should also take proactive steps to address psychological distress among employees. Establishing robust mental health support systems, such as employee assistance programs (EAPs), access to counseling services, and regular wellness initiatives, can help employees manage distress effectively. Creating a workplace culture that normalizes seeking mental health support without stigma is essential. Furthermore, offering training sessions on stress management techniques and providing safe spaces for employees to discuss their challenges can alleviate psychological distress and improve overall job satisfaction.

Given the link between workplace stressors, psychological distress, and turnover intentions, organizations should also focus on developing targeted retention strategies. Recognizing employees’ contributions through rewards, promotions, and career development opportunities can enhance their sense of value and commitment to the organization. Flexible work arrangements and fostering a positive workplace culture can further improve job satisfaction. By addressing employees’ needs and reducing stress, organizations can retain talent and reduce the costs associated with high turnover.

Finally, these findings have implications for policy development in the hospitality and tourism industry. Industry stakeholders and policymakers should establish guidelines for mental health and workplace well-being, mandating stress management programs and regular assessments of workplace environments. Collaboration between organizations and policymakers can ensure a sustainable approach to reducing workplace stress, improving employee well-being, and enhancing the overall productivity of the sector.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

One limitation of this study is its focus solely on male hospitality and tourism workers, which restricts the generalizability of the findings to female workers or mixed-gender workforces. Gender differences in stress appraisal, coping mechanisms, and flexibility are well-documented, suggesting that the observed relationships may differ for women or in more diverse settings. Future research should examine the same model across mixed-gender samples or exclusively female workers to identify gender-specific nuances and develop tailored interventions for diverse employee groups in the hospitality and tourism industry.

The study primarily focused on hospitality and tourism workers within a specific cultural and geographic context, which may limit its applicability to workers in other regions or cultural settings. The role of workplace stressors, distress, and flexibility may vary due to cultural differences in work values, stress coping, and societal expectations. Future research should conduct cross-cultural comparisons to examine how cultural factors influence these relationships, providing a more global understanding of stress and its impacts on the hospitality and tourism sectors.

A further limitation is the lack of consideration of organizational-level factors, such as leadership styles, workplace policies, and organizational culture, which could influence the impact of workplace stressors on employees. These factors likely play a significant role in shaping how employees experience stress and develop coping mechanisms. Future research should integrate organizational variables into the model to provide a more comprehensive perspective on how workplace environments influence individual outcomes.

Finally, while the study demonstrated the moderating role of psychological flexibility, it did not investigate interventions aimed at enhancing flexibility or its potential variability across individuals. Psychological flexibility is a skill that can be developed through training programs, but the study did not address whether such interventions could mitigate the observed relationships. Future research should explore the effectiveness of interventions, such as mindfulness training or acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), in increasing psychological flexibility and reducing the negative impacts of workplace stressors.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The current study was conducted according to the criteria of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the research program committee of both the International University of La Rioja and the University of Sadat City (IRB Approval No. UNIR-IRB/FEC/2024-11/25).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

The data will be available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Model Fit and Quality Indices

| |

Assessment |

Criterion |

Decision |

| Average path coefficient (APC) |

0.241, p < 0.001 |

p < 0.05 |

Supported |

| Average R-squared (ARS) |

0.240, p < 0.001 |

p < 0.05 |

Supported |

| Average adjusted R-squared (AARS) |

0.234, p < 0.001 |

p < 0.05 |

Supported |

| Average block VIF (AVIF) |

1.094 |

acceptable if ≤ 5, ideally ≤ 3.3 |

Supported |

| Average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF) |

1.318 |

acceptable if ≤ 5, ideally ≤ 3.3 |

Supported |

| Tenenhaus GoF (GoF) |

0.424 |

small ≥ 0.1, medium ≥ 0.25, large ≥ 0.36 |

Supported |

| Sympson’s paradox ratio (SPR) |

1.000 |

acceptable if ≥ 0.7, ideally = 1 |

Supported |

| R-squared contribution ratio (RSCR) |

1.000 |

acceptable if ≥ 0.9, ideally = 1 |

Supported |

| Statistical suppression ratio (SSR) |

1.000 |

acceptable if ≥ 0.7 |

Supported |

| Nonlinear bivariate causality direction ratio (NLBCDR) |

0.900 |

acceptable if ≥ 0.7 |

Supported |

References

- Abdelrahman, A. S., & Emam, M. (2022). The moderator role of organizational agility in the relationship between talent management and organizational ambidexterity in Egyptian tourism companies. Journal of Association of Arab Universities for Tourism and Hospitality, 22(2), 272–291..

- Afshar, A., Rivas, M., & Castillo, A. (2022). The outcomes of organizational fairness among precarious workers: The critical role of anomie at the work. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2022(1), 1288273..

- Agina, M., Khairy, H., Abdel Fatah, M., Manaa, Y., Abdallah, R., Aliane, N., Afaneh, J., & Al-Romeedy, B. (2023). Distributive injustice and work disengagement in the tourism and hospitality industry: Mediating roles of the workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism. Sustainability, 15(20), 15011..

- Ali, F., Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Ryu, K. (2018). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(1), 514–538. [CrossRef]

- Aliane, N., Al-Romeedy, B., Agina, M., Salah, P., Abdallah, R., Fatah, M., Khababa, N., & Khairy, H. (2023). How job insecurity affects innovative work behavior in the hospitality and tourism industry? The roles of knowledge hiding behavior and team anti-citizenship behavior. Sustainability, 15(18), 13956..

- Allisey, A., Noblet, A., Lamontagne, A., & Houdmont, J. (2014). Testing a model of officer intentions to quit: The mediating effects of job stress and job satisfaction. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 41(6), 751–771..

- Alphy, M., Al-Romeedy, B., & Ayoub, F. (2023). Does organizational health affect strategic flexibility in the Egyptian travel agencies? International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 6(1), 79–106.

- Al-Romeedy, B. (2019). The role of job rotation in enhancing employee performance in the Egyptian travel agents: The mediating role of organizational behavior. Tourism Review, 74(4), 1003–1020.

- Archer, R., Lewis, R., Yarker, J., Zernerova, L., & Flaxman, P. (2024). Increasing workforce psychological flexibility through organization-wide training: Influence on stress resilience, job burnout, and performance. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 33, 100799..

- Atkins, P., & Parker, S. (2012). Understanding individual compassion in organizations: The role of appraisals and psychological flexibility. Academy of Management Review, 37(4), 524–546..

- Bailey, C., Madden, A., Alfes, K., Shantz, A., & Soane, E. (2017). The mismanaged soul: Existential labor and the erosion of meaningful work. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 416–430..

- Bakker, A., & de Vries, J. (2021). Job Demands–Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 34(1), 1–21..

- Balducci, C., Rafanelli, C., Menghini, L., & Consiglio, C. (2024). The relationship between patients’ demands and workplace violence among healthcare workers: A multilevel look focusing on the moderating role of psychosocial working conditions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(2), 178..

- Baquero, A. (2022). Job insecurity and intention to quit: The role of psychological distress and resistance to change in the UAE hotel industry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13629.

- Baquero, A. (2023). Hotel employees’ burnout and intention to quit: The role of psychological distress and financial well-being in a moderation mediation model. Behavioral Sciences, 13(2), 84..

- Boss, P., Bryant, C., & Mancini, J. (2016). Family stress management: A contextual approach. Sage Publications..

- Cascio, W., & Montealegre, R. (2016). How technology is changing work and organizations. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3(1), 349–375..

- CBE, C., Biron, C., & Burke, R. (2014). Creating healthy workplaces: Stress reduction, improved well-being, and organizational effectiveness. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

- Chan, K., & Wan, E. (2012). How can stressed employees deliver better customer service? The underlying self-regulation depletion mechanism. Journal of Marketing, 76(1), 119–137..

- Cmiosh, P. (2024). Impact of organizational downsizing on psychosocial wellbeing of employees. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 8(11), 943–953..

- Cohen, J. E. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Dawson, D., & Golijani-Moghaddam, N. (2020). COVID-19: Psychological flexibility, coping, mental health, and wellbeing in the UK during the pandemic. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 17, 126–134..

- Dillard, D. (2019). The transactional theory of stress and coping: Predicting posttraumatic distress in telecommunicators [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University]..

- Drapeau, A., Marchand, A., & Beaulieu-Prévost, D. (2012). Epidemiology of psychological distress. Mental Illnesses-Understanding, Prediction and Control, 69(2), 105–106..

- El-Sherbeeny, A., Al-Romeedy, B., Abd elhady, M., Sheikhelsouk, S., Alsetoohy, O., Liu, S., & Khairy, H. (2023). How is job performance affected by ergonomics in the tourism and hospitality industry? Mediating roles of work engagement and talent retention. Sustainability, 15(20), 14947..

- El-Sherbeeny, A., Alsetoohy, O., Sheikhelsouk, S., Liu, S., & Abou Kamar, M. (2024). Enhancing hotel employees’ well-being and safe behaviors: The influences of physical workload, mental workload, and psychological resilience. Oeconomia Copernicana, 15(2), 765–807..

- Emam, M., & Abdel Majeed, A. (2024). The impact of digital leadership on strategic entrepreneurship at egyptair: The mediating role of organizational flexibility. Journal of the Faculty of Tourism and Hotels-University of Sadat City, 8(2), 29–50..

- Emerson, D., Hair, J., & Smith, K. (2023). Psychological distress, burnout, and business student turnover: The role of resilience as a coping mechanism. Research in Higher Education, 64(2), 228–259..

- Fordjour, G., Chan, A., & Fordjour, A. (2020). Exploring potential predictors of psychological distress among employees: A systematic review. International Journal of Psychiatry Research, 3(1), 1–11..

- Fuchs, H., Benkova, E., Fishbein, A., & Fuchs, A. (2023, September). The importance of psychological and cognitive flexibility in educational processes to prepare and acquire the skills required in the twenty-first century. In The global conference on entrepreneurship and the economy in an era of uncertainty (pp. 91–114). Springer Nature Singapore..

- George, A. (2023). Toxicity in the workplace: The silent killer of careers and lives. Partners Universal International Innovation Journal, 1(2), 1–21..

- Giao, H., Vuong, B., Huan, D., Tushar, H., & Quan, T. (2020). The effect of emotional intelligence on turnover intention and the moderating role of perceived organizational support: Evidence from the banking industry of Vietnam. Sustainability, 12(5), 1857..

- Giorgi, G., Shoss, M., & Leon-Perez, J. (2015). Going beyond workplace stressors: Economic crisis and perceived employability in relation to psychological distress and job dissatisfaction. International Journal of Stress Management, 22(2), 137..

- Gloster, A. T., Block, V. J., Klotsche, J., Villanueva, J., Rinner, M. T., Benoy, C., Walter, M., Karekla, M., & Bader, K. (2021). Psy-Flex: A contextually sensitive measure of psychological flexibility. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 22, 13–23.

- Greenhaus, J., Callanan, G., & Godshalk, V. (2009). Career management. Sage..

- Hagemeister, A., & Volmer, J. (2018). Do social conflicts at work affect employees’ job satisfaction? The moderating role of emotion regulation. International Journal of Conflict Management, 29(2), 213–235..

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Balin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: Maxwell Macmillan international editions.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage.

- Haldorai, K., Kim, W., Agmapisarn, C., & Li, J. (2023). Fear of COVID-19 and employee mental health in quarantine hotels: The role of self-compassion and psychological resilience at work. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 111, 103491..

- Harmsen, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., Maulana, R., & Van Veen, K. (2018). The relationship between beginning teachers’ stress causes, stress responses, teaching behaviour and attrition. Teachers and Teaching, 24(6), 626–643..

- Heath, C., Sommerfield, A., & von Ungern-Sternberg, B. (2020). Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Anaesthesia, 75(10), 1364–1371..

- Hebles, M., Trincado-Munoz, F., & Ortega, K. (2022). Stress and turnover intentions within healthcare teams: The mediating role of psychological safety, and the moderating effect of COVID-19 worry and supervisor support. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 758438..

- Hussain, K., Abbas, Z., Gulzar, S., Jibril, A., & Hussain, A. (2020). Examining the impact of abusive supervision on employees’ psychological wellbeing and turnover intention: The mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1818998..

- Jasiński, A. M., & Derbis, R. (2022). Work stressors and intention to leave the current workplace and profession: The mediating role of negative affect at work. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 13992.

- Kashdan, T., & Rottenberg, J. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 865–878..

- Khairy, H., Liu, S., Sheikhelsouk, S., EI-Sherbeeny, A., Alsetoohy, O., & Al-Romeedy, B. (2023). The effect of benevolent leadership on job engagement through psychological safety and workplace friendship prevalence in the tourism and hospitality industry. Sustainability, 15(17), 13245. [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2021). WarpPLS user manual: Version 7.0. ScriptWarp Systems.

- Kusluvan, S. (2003). Managing employee attitudes and behaviors in the tourism and hospitality industry. Nova Publishers..

- Labrague, L. J., & de Los Santos, J. A. A. (2021). Fear of Covid-19, psychological distress, work satisfaction and turnover intention among frontline nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(3), 395–403.

- Lee, C., Huang, G., & Ashford, S. (2018). Job insecurity and the changing workplace: Recent developments and the future trends in job insecurity research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 335–359..

- Leiter, M. (2013). Analyzing and theorizing the dynamics of the workplace incivility crisis. Springer..

- Lin, W., Shao, Y., Li, G., Guo, Y., & Zhan, X. (2021). The psychological implications of COVID-19 on employee job insecurity and its consequences: The mitigating role of organization adaptive practices. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(3), 317..

- Lorente, L., Vera, M., & Peiró, T. (2021). Nurses stressors and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of coping and resilience. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(3), 1335–1344.

- Mahmood, M. H., Coons, S. J., Guy, M. C., & Pelletier, K. R. (2010). Development and testing of the workplace stressors assessment questionnaire. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 52(12), 1192–1200.

- Mansour, S., & Tremblay, D. (2018). Work–family conflict/family–work conflict, job stress, burnout and intention to leave in the hotel industry in Quebec (Canada): Moderating role of need for family friendly practices as “resource passageways”. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(16), 2399–2430..

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111..

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. (2022). The burnout challenge: Managing people’s relationships with their jobs. Harvard University Press..

- Massé, R., Poulin, C., Dassa, C., Lambert, J., Bélair, S., & Battaglini, A. (1998). Élaboration et validation d’un outil de mesure de la détresse psychologique dans une population non clinique de Québécois francophones. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 89, 183–187.

- McCormack, N., & Cotter, C. (2013). Managing burnout in the workplace: A guide for information professionals. Elsevier..

- Milne, D. (2013). The psychology of retirement: Coping with the transition from work. John Wiley & Sons..

- Mohd-Shamsudin, F., Bani-Melhem, A. J., Bani-Melhem, S., Khassawneh, O., & Aboelmaged, M. (2024). How job stress influences employee problem-solving behaviour in hospitality setting: Exploring the critical roles of performance difficulty and empathetic leadership. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 59, 153–165..

- Molino, M., Cortese, C., & Ghislieri, C. (2019). Unsustainable working conditions: The association of destructive leadership, use of technology, and workload with workaholism and exhaustion. Sustainability, 11(2), 446..

- Morrison, E. W. (1993). Newcomer information seeking: Exploring types, modes, sources, and outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 36(3), 557–589.

- Mustafa, M., Illzam, E. M., Muniandy, R., Hashmi, M., Sharifa, A., & Nang, M. (2015). Causes and prevention of occupational stress. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences, 14(11), 98–104..

- Nazari, M., & Alizadeh Oghyanous, P. (2021). Exploring the role of experience in L2 teachers’ turnover intentions/occupational stress and psychological well-being/grit: A mixed methods study. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1892943..

- Nazier, H., & Ramadan, R. (2016). Women’s participation in labor market in Egypt: Constraints and opportunities. Economic Research Forum.

- Park, J., Yoon, S., Moon, S., Lee, K., & Park, J. (2017). The effects of occupational stress, work-centrality, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction on intent to quit among long-term care workers in Korea. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 36(2), 96–111..

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

- Putnam, L., Myers, K., & Gailliard, B. (2014). Examining the tensions in workplace flexibility and exploring options for new directions. Human Relations, 67(4), 413–440..

- Ramaci, T., Bellini, D., Presti, G., & Santisi, G. (2019). Psychological flexibility and mindfulness as predictors of individual outcomes in hospital health workers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1302..

- Ren, L., Yin, Y., Zhang, X., & Zhu, D. (2024). Does coaching leadership facilitate employees’ taking charge? A perspective of conservation of resources theory. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 39(6), 749–774.

- Ross, C. (2017). Social causes of psychological distress. Routledge..

- Russo, A., Mansouri, M., Santisi, G., & Zammitti, A. (2024). Psychological flexibility as a resource for preventing compulsive work and promoting well-being: A JD-R framework study. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 33(12), 18–34.

- Schein, E., & Schein, P. (2018). Humble leadership: The power of relationships, openness, and trust. Berrett-Koehler Publishers..

- Shao, L., Guo, H., Yue, X., & Zhang, Z. (2022). Psychological contract, self-efficacy, job stress, and turnover intention: A view of job demand-control-support model. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 868692..

- Shaukat, R., Yousaf, A., & Sanders, K. (2017). Examining the linkages between relationship conflict, performance and turnover intentions: Role of job burnout as a mediator. International Journal of Conflict Management, 28(1), 4–23..

- Slowiak, J., & Jay, G. (2023). Burnout among behavior analysts in times of crisis: The roles of work demands, professional social support, and psychological flexibility. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 105, 102185..

- Somaraju, A., Griffin, D., Olenick, J., Chang, C., & Kozlowski, S. (2022). The dynamic nature of interpersonal conflict and psychological strain in extreme work settings. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(1), 53..

- Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2015). Recovery from job stress: The stressor-detachment model as an integrative framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(S1), S72–S103..

- Spătaru, B., Podină, I., Tulbure, B., & Maricuțoiu, L. (2024). A longitudinal examination of appraisal, coping, stress, and mental health in students: A cross-lagged panel network analysis. Stress and Health, 40(5), e3450..

- St-Jean, E., Tremblay, M., Chouchane, R., & Saunders, C. (2023). Career shock and the impact of stress, emotional exhaustion, and resources on entrepreneurial career commitment during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 29(8), 1927–1949..

- Tamunomiebi, M., & Mezeh, A. (2021). Workplace stressors and employee performance: A conceptual review. Asian Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting, 21(4), 58–67..

- Thompson, H. (2010). The stress effect: Why smart leaders make dumb decisions—And what to do about it. John Wiley & Sons..

- Treglown, L., Zivkov, K., Zarola, A., & Furnham, A. (2018). Intention to quit and the role of dark personality and perceived organizational support: A moderation and mediation model. PLoS ONE, 13(3), e0195155.

- Van Heugten, K. (2011). Social work under pressure: How to overcome stress, fatigue and burnout in the workplace. Jessica Kingsley Publishers..

- Wong, A., Kim, S., Gamor, E., Koseoglu, M., & Liu, Y. (2024). Advancing employees’ mental health and psychological well-being research in hospitality and tourism: Systematic review, critical reflections, and future prospects. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research. [CrossRef]

- Xue, J., Wang, H., Chen, M., Ding, X., & Zhu, M. (2022). Signifying the relationship between psychological factors and turnover intension: The mediating role of work-related stress and moderating role of job satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 847948..

- Yoo, D. (2023). The hospitality stress matrix: Exploring job stressors and their effects on psychological well-being. Sustainability, 15(17), 13116..

- Zaki, H., & Al-Romeedy, B. (2018). Job security as a predictor of work alienation among Egyptian travel agencies’ employees. Minia Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 3(1), 47–64.

- Zhang, Y., LePine, J., Buckman, B., & Wei, F. (2014). It’s not fair… or is it? The role of justice and leadership in explaining work stressor–job performance relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 57(3), 6.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).