1. Introduction

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is a disease stemming from an urinary tract infection, such as the bladder, predominantly attributed to uropathogenic

Escherichia coli (UPEC). The number of patients affected is second only to pneumonia, and large medical expenses are incurred worldwide. Furthermore, even if cured, over 50% of the patients experience recurrence within a year of recovery [

1]. This is extremely high compared to the recurrence rate of pneumonia, which is 18.3%, and reduces the patients' quality of life [

2]. Antibiotics are generally administered to treat this disease, but the overuse of antibiotics can result in the development of resistant bacteria, making antibiotics less effective. Occasionally, it is impossible to treat. As mentioned above, appropriate use of antibiotics for the treatment of diseases is needed worldwide, and there is a need to develop alternatives to antibiotics for disease prevention.

D-mannose (Man) is sold as a supplement to prevent tract tract infections [

3]. Orally ingested Man reportedly reaches the urinary tract and binds to the FimH protein of UPEC, inhibiting infection [

4]. However, a recent study concluded that humans were ineffective in preventing tract tract infections [

5]. Furthermore, in a human study in which people who had experienced recurrent urinary tract infections ingested 2 g of Man, 12 showed no increase in urinary Man in the first hour after administration, while 7 showed an increase. Compared to before intake, the increase rate was 1.468±0.248 [

6].

UPEC has FimH at the tip of its type 1 pili, which recognizes the Man residue at the end of the sugar chain in the bladder epidermis, attaches to it, and causes infection [

1,

7,

8]. Substances that bind to FimH are expected to bind to the fimbriae of UPEC and inhibit infection of the urinary tract, and various FimH inhibitors have been synthesized and their K

D values to FimH have been investigated [

9]. However, the amounts of most of these synthetic compounds that reach the urinary tract after oral administration in humans have not been investigated. The functions required for a preventive agent against tract infections are that it is safe for humans, that it reaches the urinary tract when administered orally, and that its concentration in the urine is high enough to inhibit the adhesion of FimH and Man sugar chains to bladder epidermal cells.

1-Deoxymannose (DM), also called 1,5-anhydro-D-manntitol, is the C1-deoxyform of Man; therefore, DM is a Man analog [

10]. DM is synthesized with hydrogenation of 1,5-anhydro-D-fructose (1,5-AF) produced from α-glucan with Pd/C as a catalyst or

Saccharomyces cerevisiae enzymatically reduce 1,5-AF in medium and release DM and 1,5-anhydro-D-glucitol, C2-epimer of DM, to medium [

11,

12]. The K

D value of DM for fixing H has already been reported [

13]. The values for DM are lower than those for Man; therefore, DM is expected to be a FimH inhibitor [

9]. Here, we prepared crystals of DM samples for human trials and compared the urinary DM concentration after oral ingestion of DM and K

D to examine their potential as FimH inhibitors with orally intake.

2. Results

2.1. Preparation of Test Material and Purities

A 1,5-AF aqueous solution was prepared from starch by enzymatic degradation with a purity of 94.8%. Seventy percent of the 1,5-AF was converted to DM after Hydrogenation. The purity of the collected crystals of DM was determined to be 98.2% by the high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) which was sufficient for use in a human trial. The purity of the male supplements was 100%.

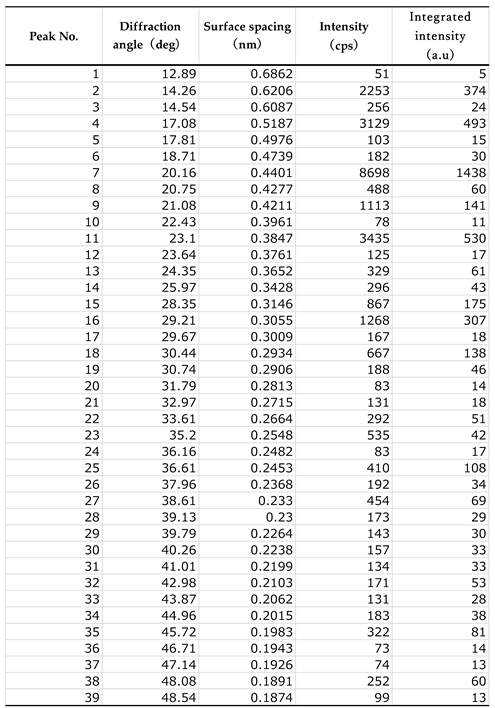

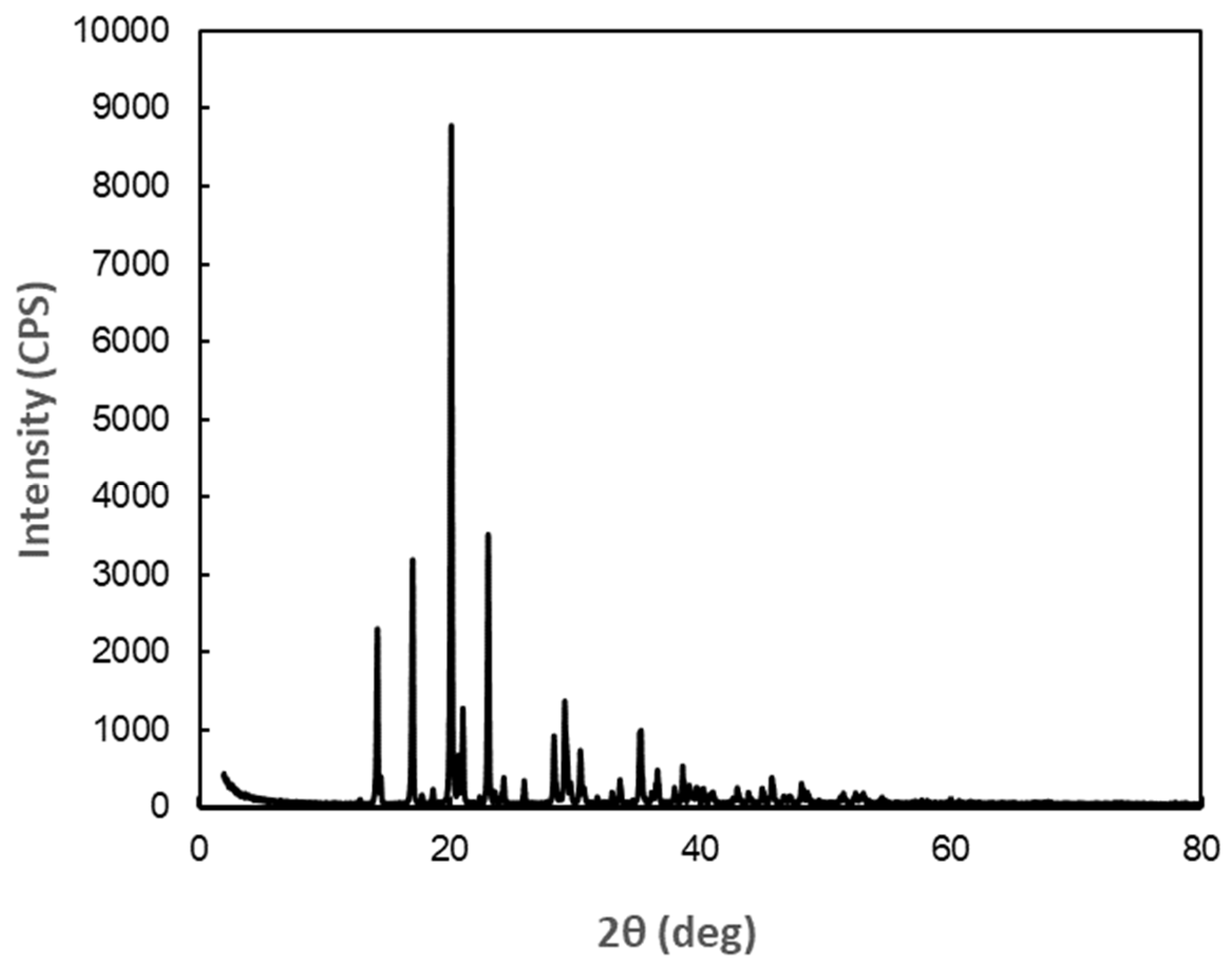

As a result of analysis of X-ray diffraction data of DM, the crystal was orthorhombic (rhombic), with space group: P212121 (19), lattice constants: a = 7.906 Å, b = 9.460 Å, c = 9.918 Å, α, β, γ = 90°. The X-ray diffraction profile is shown in

Figure 1, and the peak search results are presented in

Appendix A (

Table A1). When observed under an optical microscope, the crystals are orthorhombic (rhombic) and octahedral (

Figure 2).

2.2. Safety Analysis of DM

In a single oral gavage administration study of DM in mice, no deaths or abnormalities in general condition were observed in the DM-administered group, and no differences were observed between the control and DM-administered groups in body weight measurements 14 days after administration. Furthermore, no abnormalities were observed in the animals during necropsy. Based on the above results, it was determined that the ⅬⅮ50 value of DM for female mice exceeds 2000 mg/kg.

As a result of the dose-finding test for the bacterial reverse mutation test in DM, no increase in the number of colonies, precipitation, or growth inhibition was observed in the test microorganisms, so this test was conducted at 5 concentrations (5,000 to 313 μg/plate) with a common ratio of 2, with the highest concentration being 5,000 μg/plate. Regardless of the presence or absence of S9MIX, no increase in the number of revertant colonies was observed in any of the test strains, and neither growth inhibition nor precipitation was observed. Based on these results, DM was considered negative.

2.3. Human Trial

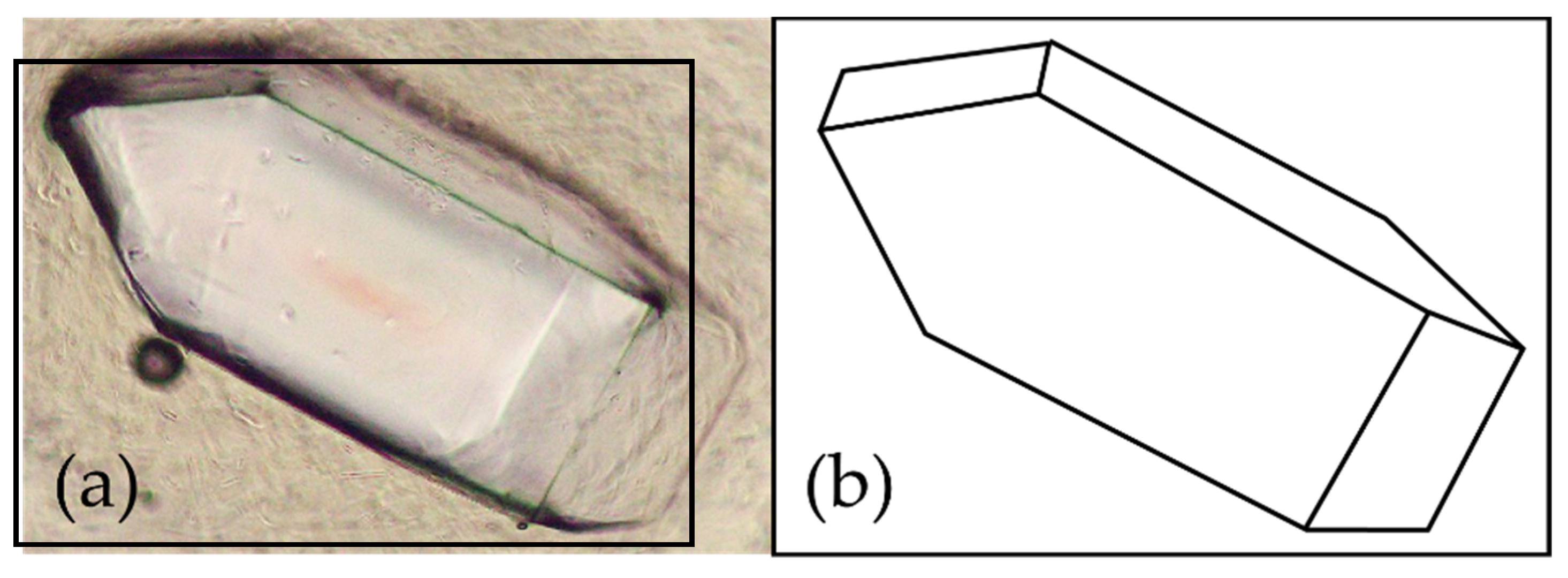

Six subjects ingested a single dose of 1 g of Man dissolved in water, and we attempted to detect Man concentrations in the urine. These values were below the detection limit of HPLC (detection limit 0.1 mg/mL). Therefore, the determination was performed using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry.

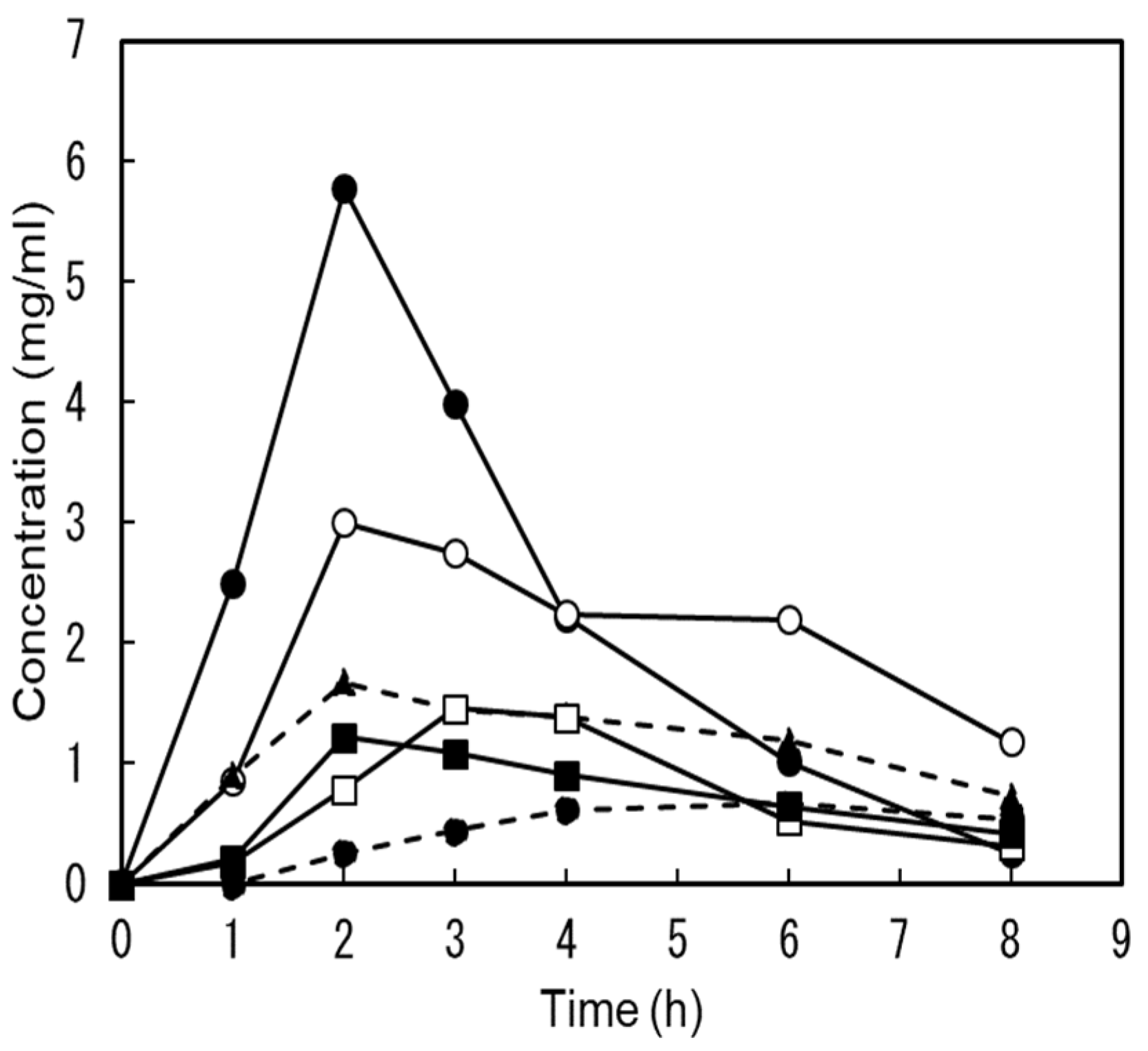

Figure 3 shows the individual changes before and after administration. Even before administration, urines of five subjects contained from 1.22 μg/mL to 11.3 μg/mL Man and one subject was 42.5 μg/mL. After administration, the number of subjects with the highest value decreased, whereas that of the other subjects did not change.

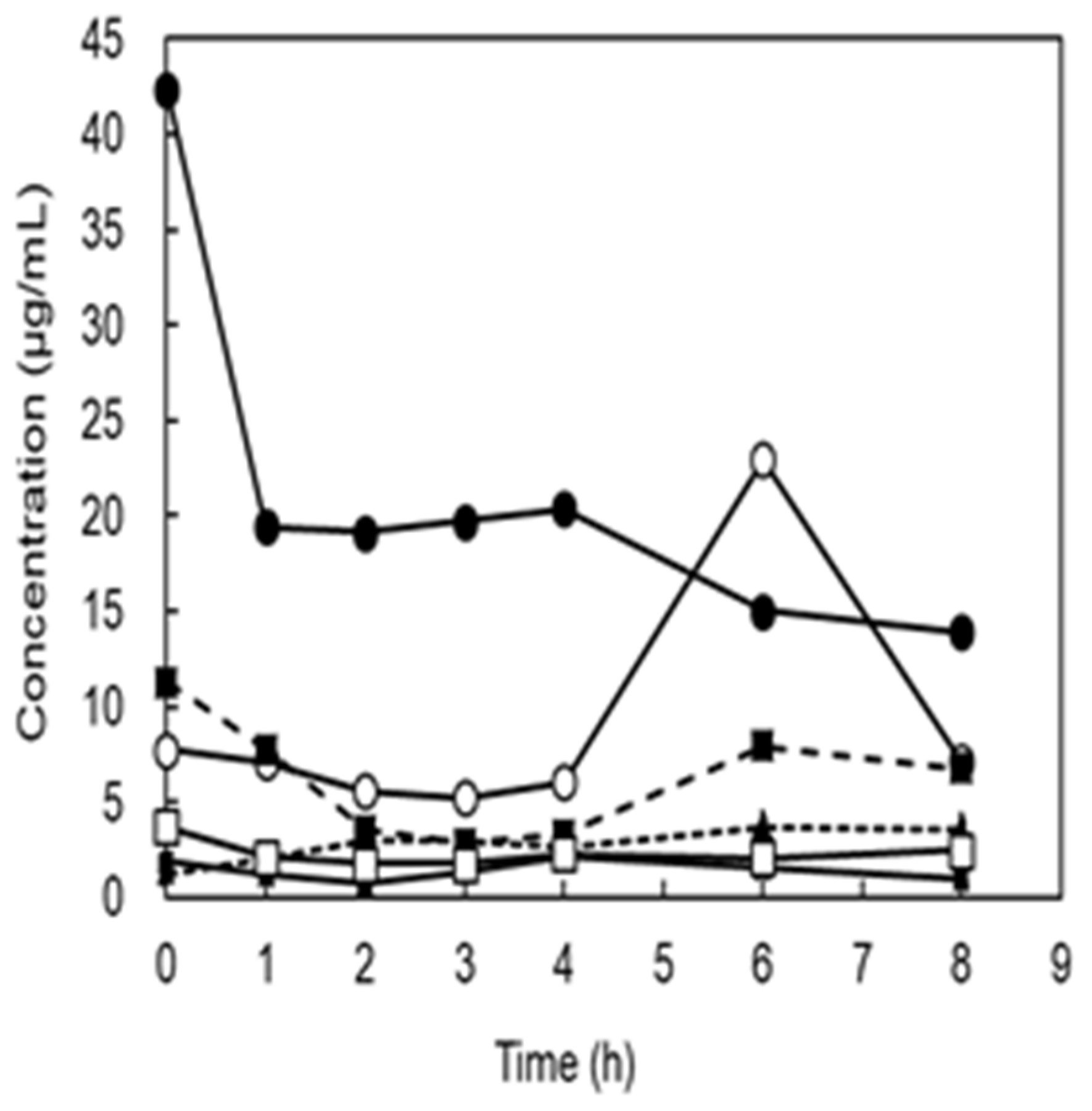

One week after the mannose trial, the same subjects ingested a single dose of 1 g DM dissolved in water; however, no abnormal symptoms such as diarrhea were observed.

Figure 4 shows individual changes in urine DM concentration after ingestion. The DM concentration in the urine of all the participants was below the HPLC detection limit before ingestion. After ingestion, all DM content in the urine increased. In four out of six subjects, the peak concentrations in urine were at 2 h and ranged from 1.22 to 5.78 mg/mL. In the remaining two subjects, the peak values were 1.46 mg/mL and 0.665 mg/mL at the 3rd and 6th hour. The urinary recovery rate of DM was 43.3±9.05%. These results indicate that most of the orally injected DM was quickly excreted in the urine.

2.4. Utilization of Carbohydrates by E. coli

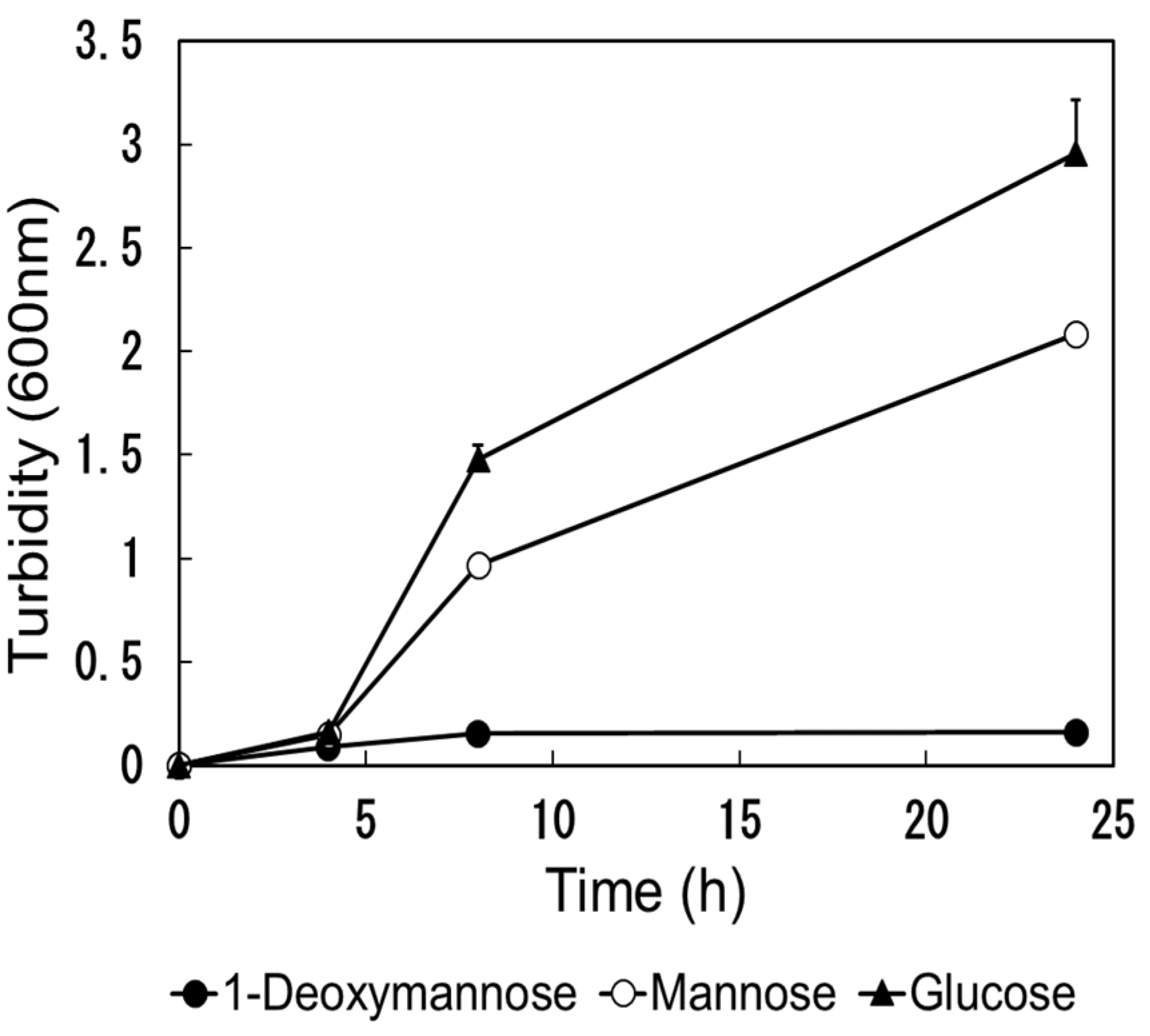

We evaluated the ability of DM by

E. coli (NBRC 3301) was evaluated. The turbidity results are illustrated in

Figure 5. No increase in turbidity was observed in the culture solution containing DM compared to that in the culture solution containing Man and glucose. DM is difficult, the use by

E. coli.

3. Discussion

ⅬⅮ50 of DM is more than 2000 mg/kg, and the bacterial reverse mutation test is negative. Therefore, DM can be regarded as safe for a single oral administration. Contrarily, in order to conduct long-term human trials on supplements, it is necessary to conduct a 90-d continuous oral administration test and micronucleus test to ensure safety.

Table 1 documents the K

D of each carbohydrate with FimH, as determined by isothermal titration calorimetry, and the urinary concentrations of DM and Man after oral intake. K

D of DM and Man are reported as 1.125 ⅿM (0.185 μg/mL) and 1.672 mⅯ (0.301 μg/mL) respectively [

9,

13]. In this Man trials, the average urinary Man concentration before ingestion was 11.4±15.7 μg/mL, which is higher than the K

D value of 0.301 μg/mL, so it may be thought that Ⅿan is constantly excreted in the urine, and that Ⅿan has an inhibitory effect on FimH and may has a function of UPEC. On the other hand, urinary Man concentration did not increase even when 1 g of Man was administered orally. A similar report was made in 2023, and it was reported that when 2 g of Ⅿan was orally intake, there were non-responders whose urinary Man/creatinine ratio did not change, and even in responders, the concentration increases by only about 40%. For these reasons, it is difficult to expect that even if Man is used as a supplement, its effect on the inhibition of UPEC adhesion will be enhanced. In 2024, a large-scale human trial was conducted on the effectiveness of Man in preventing tract infections and concluded that Man did not have any effect on preventing tract infections compared with a placebo [

5]. Man in the urinary tract in both test groups may have been protected, but there may have been no difference in their effectiveness.

After oral intake of DM, the concentrations of DM in urine rapidly increased dramatically, and the concentration was 3,600-31,200 times higher than that of KD and the values were quite large compared with those of Man. One gram of DM is a realistic amount for supplementation.

The study involved six healthy individuals, both men and women, aged between 33 and 57 years. However, due to the limited sample size, restricted age range, and uneven gender ratio, caution is advised when generalizing the findings. It is essential to evaluate the applicability of the results to groups with different age ranges and gender distributions

Although the sequence identity is only 15% with

E. coli, type 1 fimbrial FimH of

salmonella enterica has the ability to mediate mannose-sensitive adhesion like

E. coli [

14]. Viruses and microorganisms that induce red blood cell agglutination have long been studied. The inhibitory activities of Man and DM have been evaluated in guinea pig red blood cells and

salmonella Shigella flexneri [

15]. Man and ÐM inhibit agglutination at 0.025% (250 μg/mL) and 0.013% (130 μg/mL) or higher when tested at 30 times the minimum bacterial concentration that causes hemagglutination. At a bacterial concentration of 1.9 times, those of Man and DM were both greater than 0.0016% (16 μg/mL). Comparing these values to the urinary concentrations from our human studies, ÐM is much higher than the 130 μg/mL of the 30 times test for

Salmonella and Man is much lower than 250 μg/mL. At a bacterial concentration of 1.9 times, the concentration of Man was close to that of Man, which is constantly excreted in the urine. From these facts, it is assumed that the constantly excreted Man, although weak, slightly suppresses the adhesion of UPEC with type 1 fimbriae but cannot suppress adhesion when a large number of bacteria are present. Conversely, if ÐM is constantly taken as a supplement, it is likely to suppress infection even if the number of bacteria is large.

Therefore, an orally active FimH inhibitor is expected to be effective against the human urinary tract.

Although the relationship has not been clearly proven, when urinary glucose occurs in patients with diabetes, sugar may increase the chances of developing UTI [

16,

17]. Therefore, the carbohydrates in urine cannot be utilized for growth by

E. coli. Since DM is not assimilated by

E. coli, it is assumed that the risk of bacterial contamination is low, even when used as a preventive supplement for tract infections over a long period.

In human studies, the urinary recovery of DⅯ was less than 50% after ingestion to 8 h. Therefore, the remainder may have reached the large intestine without being absorbed by the small intestine. In the intestine, UPEC reaches the urinary tract via the anus and vagina [

1]. Oral mannoside intake in mice reduces UPEC in the intestine and urinary tract [

18]. Therefore, DM not absorbed by the small intestine may reduce UPEC levels in the human colon. As discussed above, DM is a potent, orally active FimH inhibitor in the human urinary tract and may also be active in the intestine.

Therefore, alternatives to antibiotics are required to prevent UTIs. Therefore, DM has the potential to act as a highly active prophylactic agent. However, because both FimH and P fimbriae are involved in the adhesion of E. coli [

1], there is some concern as to whether inhibitors of FimH alone have a preventive effect. In the future, it will be necessary to conduct safety studies on DM and evaluate its activity in long-term human ingestion prevention studies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Test Materials

The compound 1, 5-AF was prepared per prior methodology [

19]. DM was obtained by hydrogenation of aqueous 15°Bx of 1,5-AF a solution with 20% Raney Nickel of 1,5-AF solid content as catalyst at 40°C, 3 h under H

2 pressure 0.9 MPa. The reaction solution removed the catalyst was concentrated to 75°Bx. After added seed crystal of DM, the solution temperature controlled from 60°C to 40°C for 12 h with rolling with flask and crystallizing it. DM crystals were obtained by basket-type centrifugation.

The Man used pure powder for commercially available for supplements (NOW FOODS).

4.2. X-Ray Crystal Structure Analysis

We outsourced CLEARISE Co., Ltd. to perform the X-ray diffraction analysis of the DM crystal. The measurement device is Rigaku's wide-angle X-ray diffraction device: RINT2500HL, and the measurement was carried out under the following conditions; measurement wavelength: CuKα (0.15418 nm), X-ray output: 50 kV-250 mA, optical system: concentrated beam with monochromator, slit: DS 0.5 deg + 5 mmH, SS 0.5 deg, RS 0.15 mm, scanning axis: 2θ/θ interlocking, scanning method: continuous scanning, scanning range: 2≦2θ≦80 deg, scanning speed: 0.5 deg/min, sampling: 0.01 deg.

4.3. High Performance Liquid Chromatography Analysis

The high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) device used was manufactured by JASCO Corporation, and the detector was a differential refractometer. The column was used with two MITSUBISHI MCI GEL CK 08S connections, the column temperature was at 60°C, the eluent was water, the flow rate was 1 mL/min, and the injection volume was 100 μL. The obtained chromatogram was analyzed as a simple area percentage and was determined to be pure. The sample concentration was determined from the area ratio by using a standard substance of known concentration.

4.4. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS) Analysis

Zero point one five micro gram of adonitol was added as an internal standard to a 30 μL urine sample that was diluted 10 or 100 times, and 60 μL ethanol was added to remove the protein. After centrifuging at 15,000 rpm for 5 min, 60 μL of supernatant was dried with a centrifugal evaporator. After adding 20 μL of TMS-PZ (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd.) to dried sample and allowing it to react for one hour at room temperature, the concentration of Man was measured by GC-MS. The measurements were performed using a TRACE 1610 gas chromatograph equipped TSQ 9610 mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific K.K.) and TG-5SILMS column (Length:20 m, I.D.:0.18 mm, Film:0.18 μm). Helium was used as the carrier gas, and the flow rate was maintained at 0.8 mL/min. One micro little sample was injected at a temperature of 250°C, and split ratio was 1:20. The column oven temperature was kept at 80°C for 2 min, and then gradually increased to 300°C at 20°C/min. The ion source temperature was 250°C, and mass spectra range was between 50 to 550 m/z.

4.5. Acute Oral Toxicity Test Using Female Mice

This research was outsourced to Japan Food Research Laboratories. The ÐM dose was 2000 mg/kg, and a control group was set up to receive water for injection, and each group consisted of 5 ICR female mice. The test animals were fasted for 4 h prior to administration. After measuring the body weight, the test group received the ÐM solution, and the control group received the injection solution in a single dose of 20 mL/kg using a gastric tube. The observation period was 14 d, with frequent observations on the day of administration and once daily thereafter. Body weight was measured on days 7 and 14 after administration. All the animals were necropsied at the end of the observation period.

4.6. Bacterial Reverse Mutation Test

The bacterial reverse mutation test was outsourced to Bozo Research Center Co., Ltd., and tested in accordance with good laboratory practice. The protocol followed the OECD Guidelines for Testing of Chemicals 471 for bacterial reverse mutation tests. The strains used in the test were Salmonella typhimurium TA100, TA1535, TA98, and TA1537, and E. coli WP2 uvrA. 2-(2-Furyl)-3-(5-nitro-2-furyl) acrylamide, sodium azide, CR-191, 2-aminoanthracene, and benzo [a ] pyrene were used as positive controls.

4.7. Humane Trial

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of User Life Science Co., Ltd. (US L202203). Before the subjects participated in the study, the study director sufficiently explained the purpose and content of the study. After confirming that the subjects fully understood and agreed with the content, they obtained their voluntary written consent to participate in the study. The study was conducted on six healthy men and women aged 33–57 years.

A sample for oral intake was prepared by dissolving 1 g Man or DM in water to obtain a 20% w/w solution. In human studies, urine is collected before sample ingestion. The entire sample was ingested orally at 9:00, and the entire amount of urine was collected after 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 h. The subjects were allowed to eat breakfast before 9:00 a.m. and lunch at 12:00 p.m. during the test. After the urine volume was measured, the collected urine was stored in a freezer at -25°C until measurement. After thawing, Man concentration was measured by GC-MS for Man administration, and DM concentration was measured by HPLC for DM administration. The urinary recovery rate of each sample was calculated from the collected urine volume and urinary DM or Man concentration, and was divided by the administered dose to obtain the urinary recovery rate (%).

4.8. Carbohydrate Fermentation Test

E. coli (NBRC 3301) was shaken at 37°C for 17 h using 2 mL of M9 minimal medium (Difco™ M9 Minimal Salt supplemented with MgSO4 and CaCl2) containing 1% glucose to obtain a culture solution. Ten microliter of the above culture solution was added to 2 mL of M9 minimal medium containing 1% of each sugar (DM, Man, glucose), and cultured with shaking at 37°C. During the culture, 100 μL was taken out over time, and the turbidity (600 nm) was measured using a cell with an optical path length of 1 cm.

5. Conclusions

DM demonstrates binding affinity for FimH. After oral intake of DM, the concentrations of DM in urine rapidly increased dramatically, and the concentration was 3,600-31,200 times higher than that of KD and the values were quite large compared with those of Man. Upon oral administration, almost all of the ingested DM is excreted into the urinary tract. Therefore, it is an orally active FimH inhibitor in humans. It is necessary to conduct a 90-d continuous oral administration test and micronucleus test to ensure safety, and evaluate its activity in long-term human ingestion prevention studies.

6. Patents

This article is contingent upon data from two patents: “Urinary tract infection prevention/treatment agent containing 1-deoxymannose” (WO/2024/034495) and”1-deoxymannose crystals precipitated from an aqueous solvent” (Unpublished Japanese patents).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K. Y.; Investigation, H. H., N. M., T. K., and S. I.; Project administration, K. Y.; Project administration, K. Y.; Visualization, N. M.; Writing - original draft, H. H. and K. Y.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the METI R&D Support Program for Growth-Oriented Technology SMEs (Grant Number JPJ005698).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of User Life Science (ULS202203, 31/4/2022).”

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was procured from all participants involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for publication of this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions of this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank the volunteers who participated in the human trials. We would like to thank Editage (

www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors (Yoshinaga K., Hayashi H., Miyazaki N. T.Kawakami and S. Izumi) are employees of SUNUS Co., Ltd., and the rest are joint researchers. This research presented in this paper was funded by SUNUS Co., Ltd. and the METI R&D Support Program for Growth-Oriented Technology SMEs (Grant Number JPJ005698). This study was performed as part of the professional duties of the authors. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of SUNUS Co. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DM |

1-Deoxymannose |

| Man |

Ⅾ-Mannose |

| UPEC |

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli

|

| UTI |

Urinary tract infection |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table 1.

Peak search results from X-ray crystallographic analysis of 1-deoxymannose.

Table 1.

Peak search results from X-ray crystallographic analysis of 1-deoxymannose.

References

- Sihra, N.; Goodman, A.; Zakri, R.; Sahai, A.; Malde, S. Nonantibiotic prevention and management of recurrent urinary tract infection. Nat Rev Urol 2018, 15, 750–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharmarajan, K.; Hsieh, A.F.; Lin, Z.; Bueno, H.; Ross, J.S.; Horwitz, L.I.; Barreto-Filho, J.A.; Kim, N.; Bernheim, S.M.; Suter, L.G.; et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, a.c. ute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA 2013, 309, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- De Nunzio, C.; Bartoletti, R.; Tubaro, A.; Simonato, A.; Ficarra, V. Role of D-mannose in the prevention of recurrent uncomplicated cystitis: State of the art and future perspectives. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ala-Jaakkola, R.; Laitila, A.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Lehtoranta, L. Role of D-mannose in urinary tract infections – A narrative review. Nutr J 2022, 21, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hayward, G.; Mort, S.; Hay, A.D.; Moore, M.; Thomas, N.P.B.; Cook, J.; Robinson, J.; Williams, N.; Maeder, N.; Edeson, R.; et al. d-Mannose for Prevention of Recurrent urinary tract infection among Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2024, 184, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fan, E.; Dashti, M.; Fuentes, J.; Reitzer, L.; Christie, A.L.; Zimmern, P.E. d-mannosuria levels measured 1 h after d-mannose intake can select out favorable responders: A pilot study. Neurourol Urodyn 2023, 42, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, S.N.; Goguen, J.D.; Sun, D.; Klemm, P.; Beachey, E.H. Identification of two ancillary subunits of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbriae by using antibodies against synthetic oligopeptides of fim gene products. J Bacteriol 1987, 169, 5530–5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xie, B.; Zhou, G.; Chan, S.Y.; Shapiro, E.; Kong, X.P.; Wu, X.R.; Sun, T.T.; Costello, C.E. Distinct glycan structures of uroplakins Ia and Ib: Structural basis for the selective binding of FimH adhesin to uroplakin Ia. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 14644–14653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krammer, E.M.; de Ruyck, J.; Roos, G.; Bouckaert, J.; Lensink, M.F. Targeting dynamical binding processes in the design of non-antibiotic anti-adhesives by molecular simulation-the example of FimH. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kühn, A.; Yu, S.; Giffhorn, F. Catabolism of 1,5-anhydro-D-fructose in Sinorhizobium morelense S-30.7.5: Discovery, characterization, and overexpression of a new 1,5-anhydro-D-fructose reductase and its application in sugar analysis and rare sugar synthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006, 72, 1248–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Izumi, S.; Hirota, T.; Yoshinaga, K.; Abe, J. Bioconversion of 1,5-anhydro-D-fructose to 1,5-anhydro-D-glucitol and 1,5-anhydro-D-mannitol using Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Appl Glycosci 2012, 59, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.M.; Lundt, I.; Marcussen, J.; Yu, S. 1,5-Anhydro-D-fructose; a versatile chiral building block: Biochemistry and chemistry. Carbohydr Res 2002, 337, 873–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbani, S.; Krammer, E.M.; Roos, G.; Zalewski, A.; Preston, R.; Eid, S.; Zihlmann, P.; Prévost, M.; Lensink, M.F.; Thompson, A.; et al. Mutation of Tyr137 of the universal Escherichia coli fimbrial adhesin FimH relaxes the tyrosine gate prior to mannose binding. IUCrJ 2017, 4, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kisiela, D.I.; Kramer, J.J.; Tchesnokova, V.; Aprikian, P.; Yarov-Yarovoy, V.; Clegg, S.; Sokurenko, E.V. Allosteric catch bond properties of the FimH adhesin from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 38136–38147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Old, D.C. Inhibition of the interaction between fimbrial haemagglutinins and erythrocytes by D-mannose and other carbohydrates. J Gen Microbiol 1972, 71, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anan, G.; Kikuchi, D.; Omae, K.; Hirose, T.; Okada, K.; Mori, T. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors increase urinary tract infections?-a cross sectional analysis of a nationwide Japanese claims database. Endocr J 2023, 70, 1103–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Confederat, L.G.; Condurache, M.I.; Alexa, R.E.; Dragostin, O.M. Particularities of urinary tract infections in diabetic patients: A concise review. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Spaulding, C.N.; Klein, R.D.; Ruer, S.; Kau, A.L.; Schreiber, H.L.; Cusumano, Z.T.; Dodson, K.W.; Pinkner, J.S.; Fremont, D.H.; Janetka, J.W.; et al. Selective depletion of uropathogenic E. coli from the gut by a FimH antagonist. Nature 2017, 546, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fujisue, M.; Yoshinaga, K.; Muroya, K.; Abel, J.; Hizukuri, S. Preparation and antioxidative activity of 1,5-anhydrofructose. J Appl Glycosci 1999, 46, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).