Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Patient Characteristics

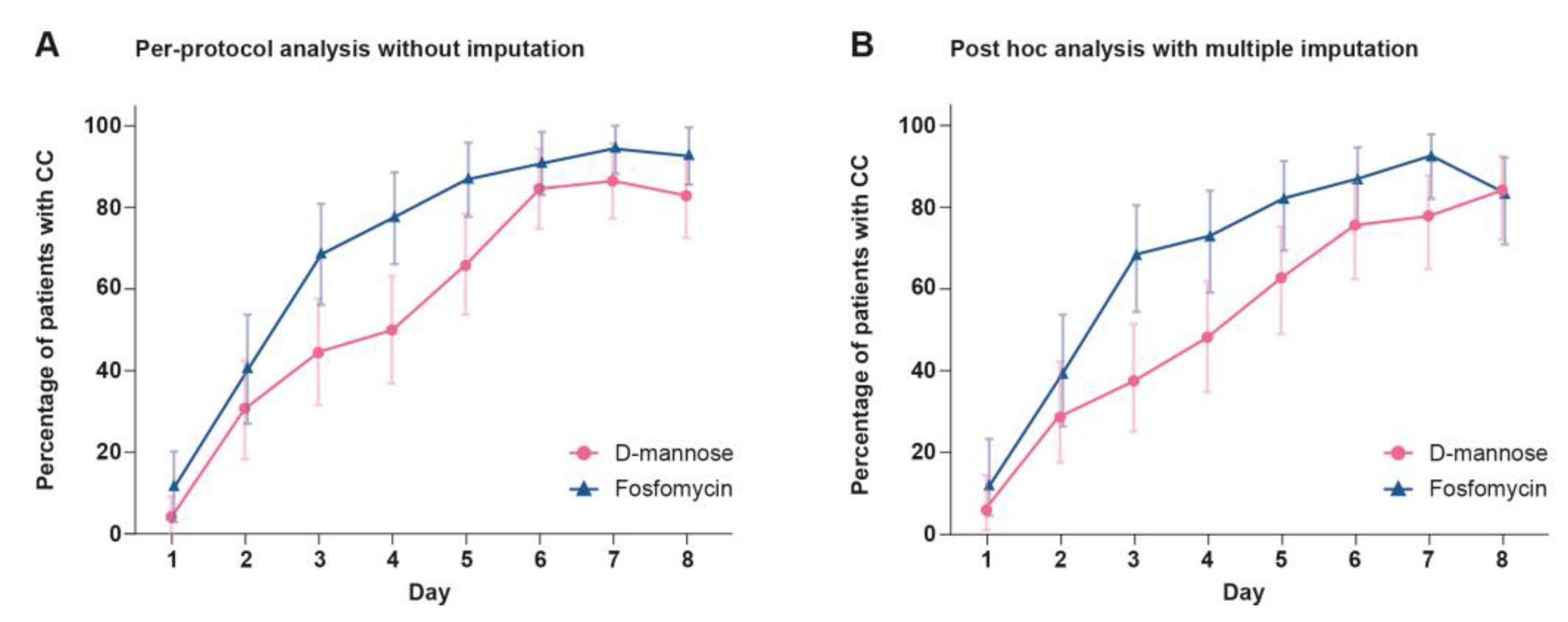

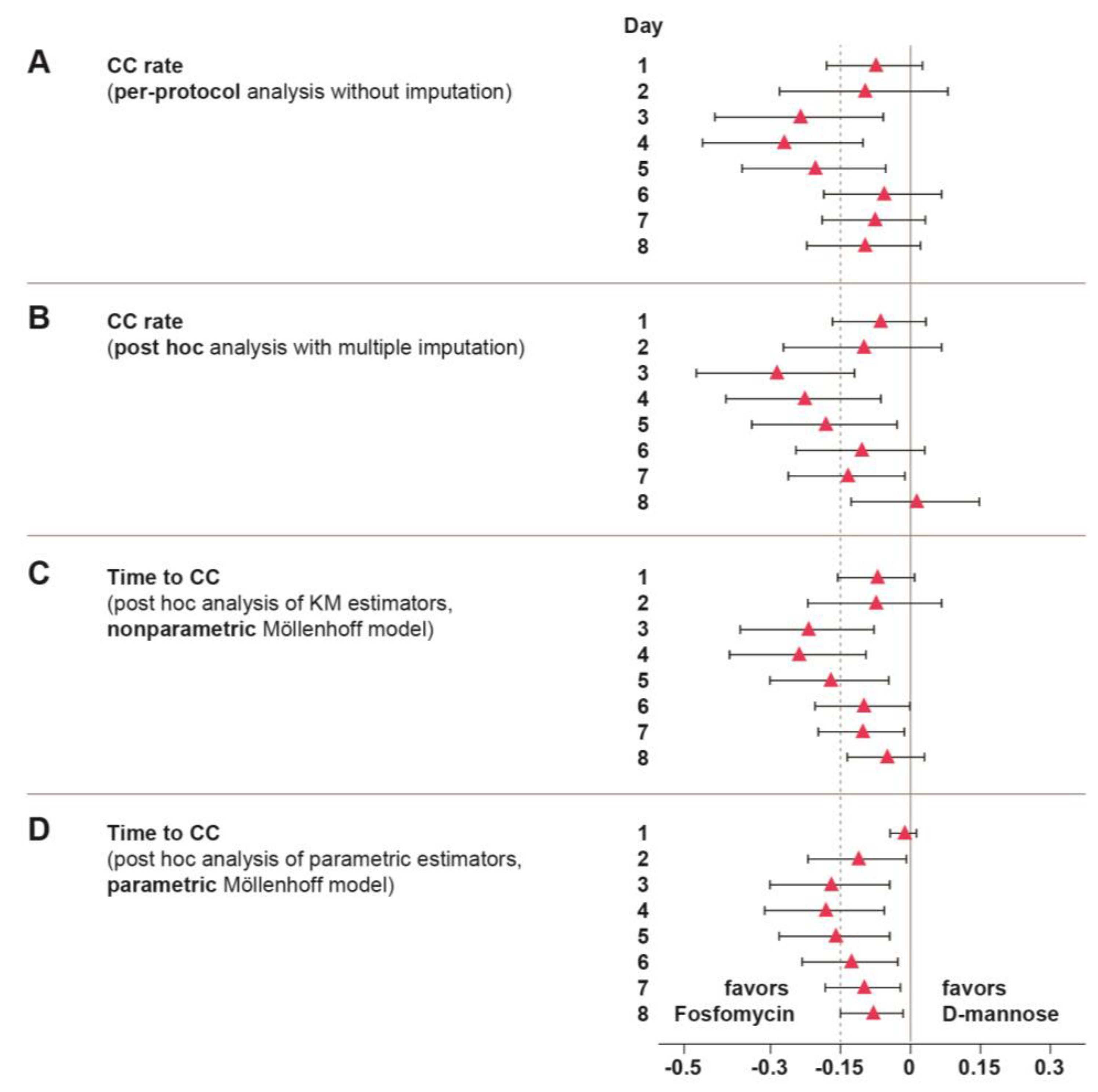

2.3. Clinical Cure (CC)

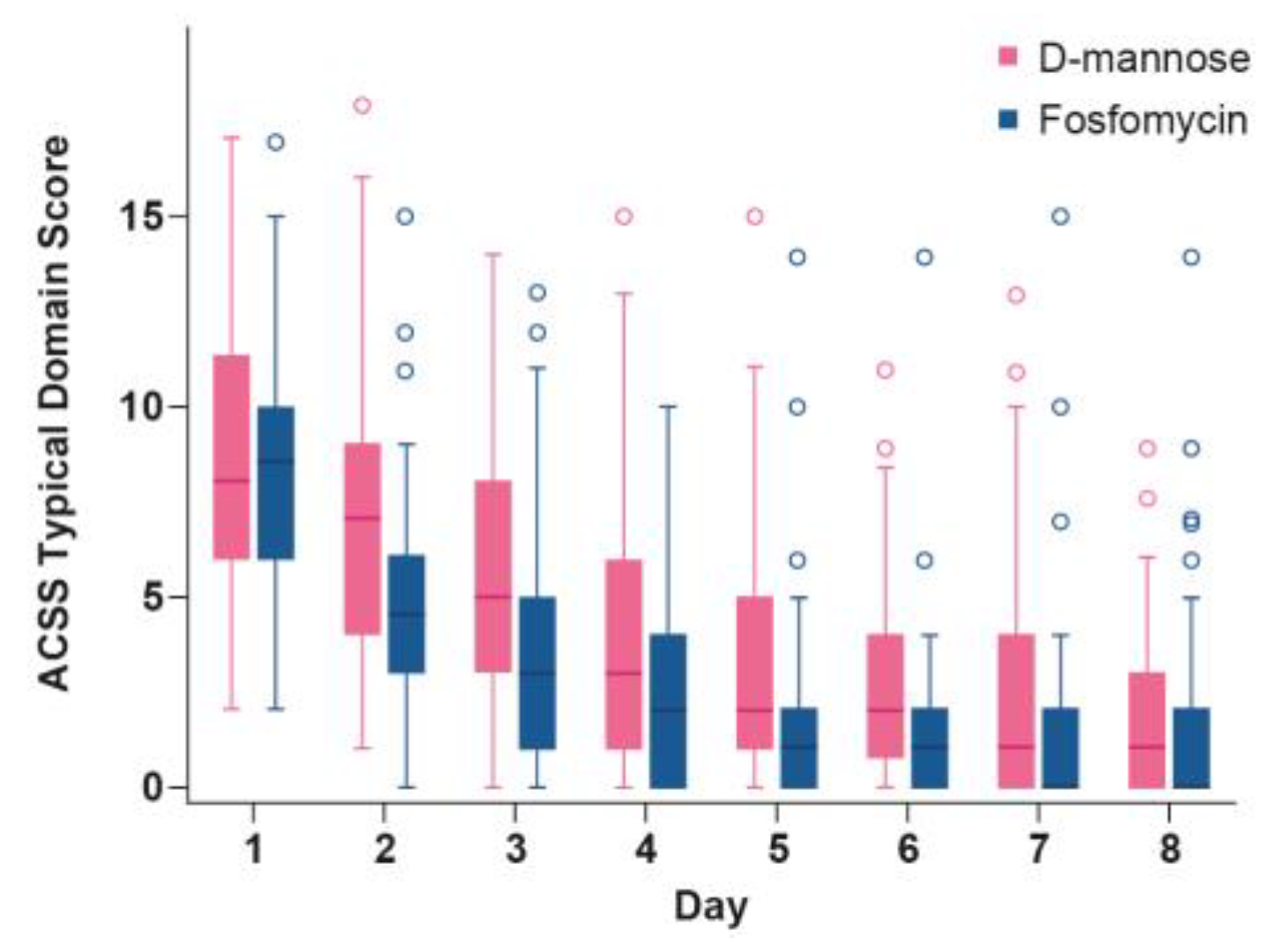

2.4. Time Course of ACSS Typical Domain Score

2.5. UTI Recurrence and Antibiotic Treatment

2.6. Microbiological Status

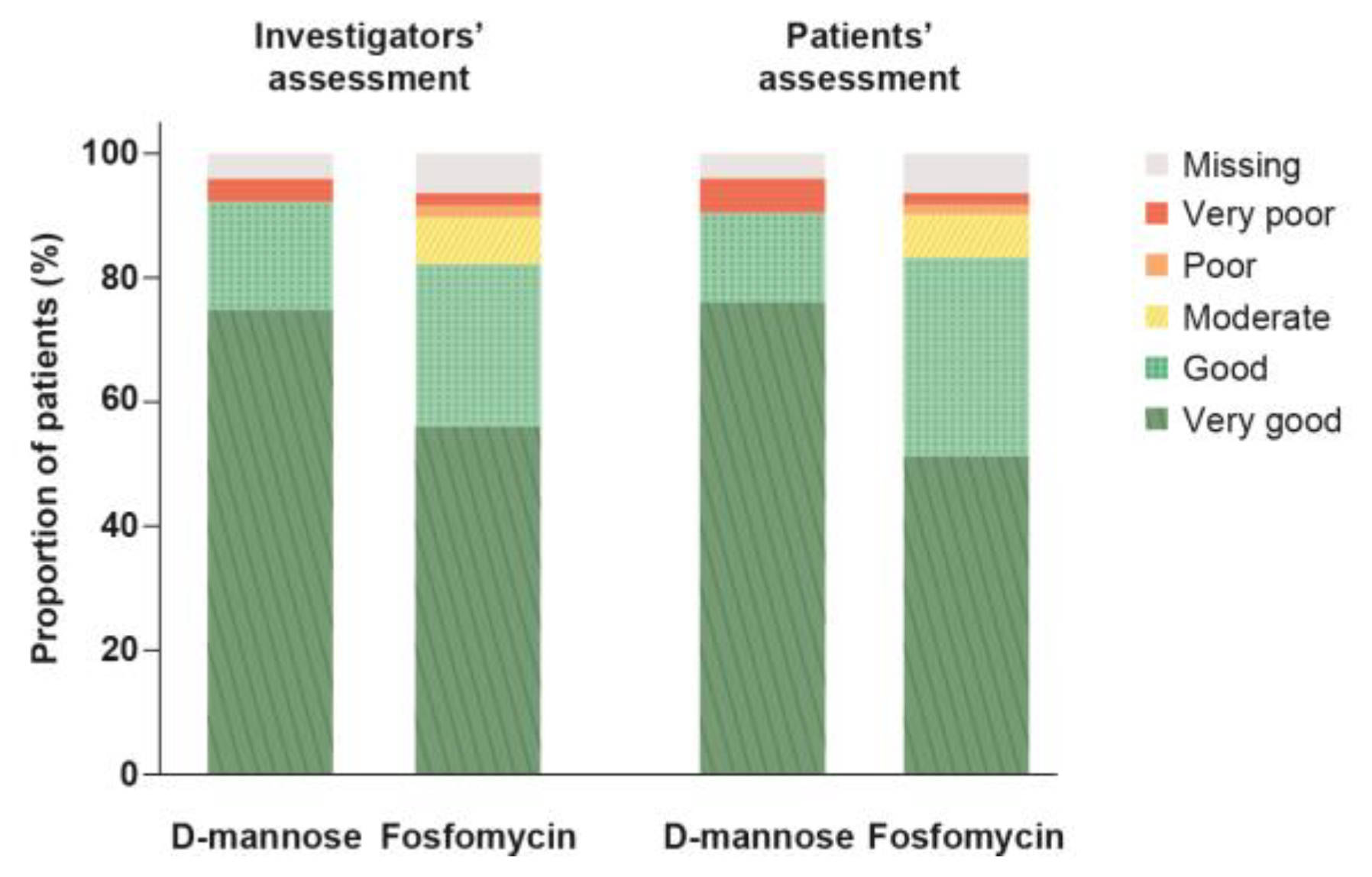

2.7. Global Assessment of Efficacy

2.8. Safety Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Conduct

4.2. Participants and Treatments

4.3. Endpoints and Assessments

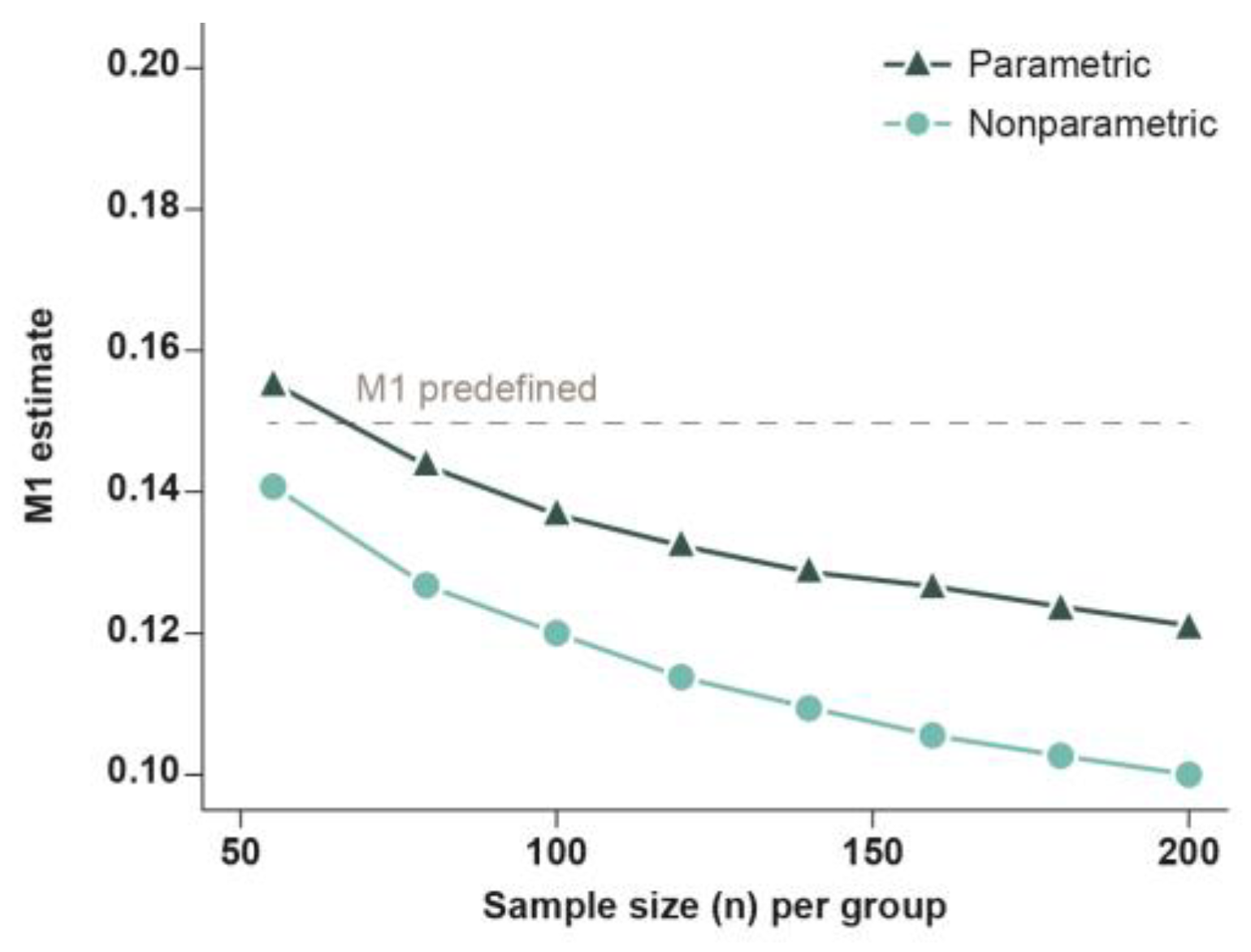

4.4. Statistical Methods

4.4.1. Sample Size Estimation

4.4.2. Analyses According to Protocol

4.4.3. Post Hoc Analyses

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foxman, B. Urinary tract infection syndromes: occurrence, recurrence, bacteriology, risk factors, and disease burden. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2014, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, C.C.; Hawking, M.K.D.; Quigley, A.; McNulty, C.A.M. Incidence, severity, help seeking, and management of uncomplicated urinary tract infection: a population-based survey. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2015, 65, e702–e707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Mireles, A.L.; Walker, J.N.; Caparon, M.; Hultgren, S.J. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2015, 13, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonkat G., Bartoletti R., Bruyère F., Cai T., Geerlings S.E., Köves B., Kranz J., Schubert S., Pilatz A., Veeratterapillay R., Wagenlehner F. EAU Guidelines on Urological Infections. In: EAU Guidelines, edition presented at the annual EAU Congress Paris 2024. ISBN 978-94-92671-23-3.

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie e., V. S3 Leitlinie: Epidemiologie, Diagnostik, Therapie, Prävention und Management unkomplizierter, bakterieller, ambulant erworbener Harnwegsinfektionen bei Erwachsenen – Aktualisierung 2024. Langversion, 3.0, AWMF Registernummer: 043/044. Available online: https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/043-044 (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Castañeda-García, A.; Blázquez, J.; Rodríguez-Rojas, A. Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Impact of Acquired and Intrinsic Fosfomycin Resistance. Antibiotics 2013, 2, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidjanov, J.F.; Overesch, A.; Abramov-Sommariva, D.; Hoeller, M.; Steindl, H.; Wagenlehner, F.M.; Naber, K.G. Acute Cystitis Symptom Score questionnaire for measuring patient-reported outcomes in women with acute uncomplicated cystitis: Clinical validation as part of a phase III trial comparing antibiotic and nonantibiotic therapy. Investig Clin Urol 2020, 61, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, G.M. Fosfomycin trometamol: a review of its use as a single-dose oral treatment for patients with acute lower urinary tract infections and pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria. Drugs 2013, 73, 1951–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiergeist, A.; Gessner, A. The human intestinal microbiome and why you have to think twice before prescribing antibiotics! MMW Fortschr. Med. 2018, 160, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Vietinghoff, S.; Shevchuk, O.; Dobrindt, U.; Engel, D.R.; Jorch, S.K.; Kurts, C.; Miethke, T.; Wagenlehner, F. The global burden of antimicrobial resistance - urinary tract infections. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 2024, 39, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarshar, M.; Behzadi, P.; Ambrosi, C.; Zagaglia, C.; Palamara, A.T.; Scribano, D. FimH and Anti-Adhesive Therapeutics: A Disarming Strategy Against Uropathogens. Antibiotics 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlizzi, M.E.; Gribaudo, G.; Maffei, M.E. UroPathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) Infections: Virulence Factors, Bladder Responses, Antibiotic, and Non-antibiotic Antimicrobial Strategies. Frontiers in Microbiology 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaulding, C.N.; Hultgren, S.J. Adhesive Pili in UTI Pathogenesis and Drug Development. Pathogens 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaglione, F.; Musazzi, U.M.; Minghetti, P. Considerations on D-mannose Mechanism of Action and Consequent Classification of Marketed Healthcare Products. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 636377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domenici, L.; Monti, M.; Bracchi, C.; Giorgini, M.; Colagiovanni, V.; Muzii, L.; Benedetti Panici, P. D-mannose: a promising support for acute urinary tract infections in women. A pilot study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 2920–2925. [Google Scholar]

- Porru, D.; Parmigiani, A.; Tinelli, C.; Barletta, D.; Choussos, D.; Di Franco, C.; Bobbi, V.; Bassi, S.; Miller, O.; Gardella, B.; et al. Oral D-mannose in recurrent urinary tract infections in women: a pilot study. Journal of Clinical Urology 2014, 7, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranjčec, B.; Papeš, D.; Altarac, S. d-mannose powder for prophylaxis of recurrent urinary tract infections in women: a randomized clinical trial. World Journal of Urology 2014, 32, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phé, V.; Pakzad, M.; Haslam, C.; Gonzales, G.; Curtis, C.; Porter, B.; Chataway, J.; Panicker, J.N. Open label feasibility study evaluating D-mannose combined with home-based monitoring of suspected urinary tract infections in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurourology and Urodynamics 2017, 36, 1770–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenger, S.M.; Bradley, M.S.; Thomas, D.A.; Bertolet, M.H.; Lowder, J.L.; Sutcliffe, S. D-mannose vs other agents for recurrent urinary tract infection prevention in adult women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 2020, 223, 265.e1–265.e13. [Google Scholar]

- Parazzini, F.; Ricci, E.; Fedele, F.; Chiaffarino, F.; Esposito, G.; Cipriani, S. Systematic review of the effect of D-mannose with or without other drugs in the treatment of symptoms of urinary tract infections/cystitis (Review). Biomed. Rep. 2022, 17, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenlehner, F.; Baumgartner, L.N.; Schopf, B.; Milde, J. Non-interventional study with Femannose® N to investigate tolerance, quality of life and course of symptoms in acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection. Journal Pharmakol u Ther 2020, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Wagenlehner, F.; Lorenz, H.; Ewald, O.; Gerke, P. Why d-Mannose May Be as Efficient as Antibiotics in the Treatment of Acute Uncomplicated Lower Urinary Tract Infections—Preliminary Considerations and Conclusions from a Non-Interventional Study. Antibiotics 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möllenhoff, K.; Tresch, A. Investigating non-inferiority or equivalence in time-to-event data under non-proportional hazards. Lifetime Data Anal. 2023, 29, 483–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadidi, M.F.; Alhamami, N.; Alhakami, M.; Abdulhamid, A.S.; Alsharif, A.; Alomari, M.S.; Alghamdi, Y.A.; Alshehri, S.; Ghaddaf, A.A.; Alsenani, F.M.; et al. Antibiotics efficacy in clinical and microbiological cure of uncomplicated urinary tract infection: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. World Journal of Urology 2024, 42, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagenlehner, F.M.; Abramov-Sommariva, D.; Höller, M.; Steindl, H.; Naber, K.G. Non-Antibiotic Herbal Therapy (BNO 1045) versus Antibiotic Therapy (Fosfomycin Trometamol) for the Treatment of Acute Lower Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Women: A Double-Blind, Parallel-Group, Randomized, Multicentre, Non-Inferiority Phase III Trial. Urol. Int. 2018, 101, 327–336. [Google Scholar]

- EMA / Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Guideline on the evaluation of medicinal products indicated for treatment of bacterial infections. 19 May 2022. CPMP/EWP/558/95 Rev 3. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-evaluation-medicinal-products-indicated-treatment-bacterial-infections-revision-3_en.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Jansåker, F.; Thønnings, S.; Hertz, F.B.; Kallemose, T.; Værnet, J.; Bjerrum, L.; Benfield, T.; Frimodt-Møller, N.; Knudsen, J.D. Three versus five days of pivmecillinam for community-acquired uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled superiority trial. eClinicalMedicine 2019, 12, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidjanov, J.F.; Naber, K.G.; Pilatz, A.; Radzhabov, A.; Zamuddinov, M.; Magyar, A.; Tenke, P.; Wagenlehner, F.M. Evaluation of the draft guidelines proposed by EMA and FDA for the clinical diagnosis of acute uncomplicated cystitis in women. World Journal of Urology 2020, 38, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidjanov, J.F.; Naber, K.G.; Pilatz, A.; Radzhabov, A.; Zamuddinov, M.; Magyar, A.; Tenke, P.; Wagenlehner, F.M. Additional assessment of Acute Cystitis Symptom Score questionnaire for patient-reported outcome measure in female patients with acute uncomplicated cystitis: part II. World Journal of Urology 2020, 38, 1977–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmiemann, G.; Gágyor, I.; Hummers-Pradier, E.; Bleidorn, J. Resistance profiles of urinary tract infections in general practice--an observational study. BMC Urol. 2012, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency. Recommendations to restrict use of fosfomycin antibiotics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/referral/fosfomycin-article-31-referral-recommendations-restrict-use-fosfomycin-antibiotics_en.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Alidjanov, J.F.; Pilatz, A.; Abdufattaev, U.A.; Wiltink, J.; Weidner, W.; Naber, K.G.; Wagenlehner, F. German validation of the Acute Cystitis Symptom Score. Urologe A 2015, 54, 1269–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services - Food and Drug Administration. Non-Inferiority Clinical Trials to Establish Effectiveness - Guidance for Industry (FDA-2010-D-0075). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/78504/download (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Bootstrap Methods and their Application; Davison, A.C., Hinkley, D.V., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1997; ISBN 9780521574716. [Google Scholar]

| D-mannose | Fosfomycin | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 61 | N = 57 | p-value | |

| Age, years | |||

| Mean (SD) | 40.8 (13.9) | 41.5 (14.9) | p = 0.793b |

| Median | 40.0 | 41.0 | |

| Min–Max | 21–69 | 18–70 | |

| Ethnic origin | |||

| Caucasian, n (%) | 58 (95.1) | 57 (100.0) | p = 0.245c |

| Asian, n (%) | 3 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| BMI | |||

| Mean (SD) | 24.94 (4.66) | 25.56 (5.74) | p = 0.523b |

| Median | 23.46 | 23.44 | |

| Min–Max | 18.3–38.1 | 17.6–41.6 | |

| Positive urine culture for bacteria, n (%) | 36 (59.0) | 35 (61.4) | p = 0.852c |

| E. coli infection, n (%) | 28 (45.9) | 29 (50.9) | p = 0.713c |

| ACSS Typical Domain Scorea | |||

| Mean (SD) | 10.8 (3.0) | 10.2 (2.8) | p = 0.263b |

| Median | 11.0 | 10.0 | |

| Min–Max | 6–17 | 6–16 | |

|

Disease severity by category (ACSS Typical Domain Score)a |

|||

| Moderate (6–12), n (%) | 41 (67.2) | 44 (77.2) | p = 0.305c |

| Severe (>12), n (%) | 20 (32.8) | 13 (22.8) | p = 0.113d |

| D-mannose | Fosfomycin | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 61 | N = 57 | OR [95% CI]a; p-value | |

| Overview of patients with treatment-emergent AEs, n (%) | |||

| Any AEs during the study | 20 (32.8) | 26 (45.6) | 0.58 [0.26, 1.31]; p = 0.187 |

| AEs during the acute phase | 9 (14.8) | 16 (28.1) | 0.45 [0.16, 1.20]; p = 0.114 |

| SAEs | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | n.e. |

| Severe AEs | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | n.e. |

| AEs leading to treatment discontinuation | 2 (3.3) | 1 (1.8) | n.e. |

| AEs leading to study withdrawal | 2 (3.3) | 1 (1.8) | n.e. |

| AEs related to study device/drug | 6 (9.8) | 13 (22.8) | 0.37 [0.11, 1.15]; p = 0.079 |

| Patients with AEs by System Organ Class, n (%) | |||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 6 (9.8) | 14 (24.6) | 0.34 [0.10, 1.03]; p = 0.048 |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | n.e. |

| Infections and infestations | 8 (13.1) | 7 (12.3) | 1.08 [0.32, 3.77]; p = 1.0 |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | n.e. |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | n.e. |

| Nervous system disorders | 6 (9.8) | 8 (14.0) | 0.67 [0.18, 2.38]; p = 0.574 |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1.8) | n.e. |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.5) | n.e. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).