1. Introduction

Dementia is a progressive brain disorder affecting memory, cognition, language, and behavior. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 55 million people worldwide were living with dementia in 2019, with projections estimating that this number will rise to 78 million by 2030 and 139 million by 2050 [

1]. The condition poses significant challenges for public health, particularly in aging societies like Taiwan, where 10% of individuals over 65 and 30% over 80 are affected [

2]. Dementia often manifests in behavioral and psychological symptoms, such as emotional instability, aggression, and communication difficulties, which contribute to caregiver stress, including feelings of anger, depression, and fatigue [

3]. These issues emphasize the urgent need for effective interventions and health education strategies.

Dementia prevention and early intervention are essential strategies for reducing the disease burden. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) represents an early transitional stage between normal aging and dementia, characterized by mild deficits in memory or other cognitive domains without significant impairment of daily functioning [

4]. Approximately 10%-15% of individuals with MCI progress to Alzheimer's disease annually; however, appropriate early interventions can stabilize or even improve cognitive function in some individuals [

5]. Health education has demonstrated significant benefits by enhancing individuals' dementia-related knowledge, health literacy, and self-management skills, thereby improving quality of life and delaying disease progression [

6,

7]. Tailored educational strategies incorporating oral, written, and interactive methods have proven especially effective in enhancing comprehension and overcoming cognitive barriers among older adults with MCI [

8]. Thus, equipping older adults with comprehensive dementia prevention education remains a critical public health priority.

Self-directed learning (SDL), as defined by Malcolm Knowles, is a process in which individuals initiate their own learning by diagnosing their needs, formulating learning goals, identifying resources, choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies, and evaluating outcomes [

9]. SDL abilities, closely linked to health literacy, are essential for older individuals to effectively manage their health, understand treatment prescriptions, and engage in proactive self-care practices [

10,

11]. SDL in this study emphasizes "self-regulated learning (SRL)," which is an active and constructive process where learners establish personal learning goals and actively monitor, regulate, and control their cognitive processes, motivation, and behavior, all influenced by their goals and the surrounding environmental context [

12]. Effective SRL includes structured goal-setting, systematic self-monitoring, reflective evaluation, and adaptive learning behaviors shaped by feedback and self-assessment [

13,

14]. Research suggests that older adults favor structured guidance along with chances for self-regulated practice, as personal support boosts their engagement and comprehension [

15]. Recent studies show that interactive tools integrated into virtual reality (VR) environments can greatly enhance SRL by boosting learner engagement with educational content, particularly in situations where student-teacher or peer interactions are restricted [

16]. However, much of the current SRL literature has focused on student populations or digital natives using AR or online platforms [

17], leaving a gap in understanding how SRL strategies may function within immersive VR environments tailored for cognitively vulnerable older adults. Recognizing these findings, our study developed a VR-based dementia prevention program specifically designed around SRL principles, incorporating structured and achievable learning goals, interactive tasks providing reinforcing feedback, and guided concept-mapping exercises that facilitate reflection and application to personal life experience.

VR, which provides immersive and interactive learning environments, has emerged as a promising modality in health education, offering advantages in knowledge acquisition, skill development, and learner engagement over traditional approaches [

18]. In dementia prevention, VR has been demonstrated to stimulate cognitive processes, replicate real-life care scenarios, and alleviate behavioral and psychological symptoms [

19,

20]. A meta-analysis reported small-to-medium positive effects on cognition and physical fitness in individuals with MCI or dementia, particularly when using semi-immersive systems [

21]. Older adults, including those with MCI, also report high acceptance of VR, citing lower discomfort and greater motivation [

22]. However, most prior research has focused on global cognition or executive function, with limited attention to health literacy and self-efficacy—both vital for dementia prevention [

19]. While VR has shown promise in clinical training and dementia care, existing research has largely focused on healthcare professionals, leaving a gap in evidence for older adults with MCI. To address this, the present study evaluates the effectiveness of a VR-based dementia prevention program using SRL strategies in enhancing dementia-related knowledge, health literacy, and self-efficacy among older adults with MCI.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study adopted a two-arm, open-label pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) design to evaluate the feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of a VR-based dementia prevention program among older adults with MCI. Given the nature of the intervention, blinding of participants and facilitators was not feasible. The trial followed a parallel-group design with pre- and post-intervention assessments.

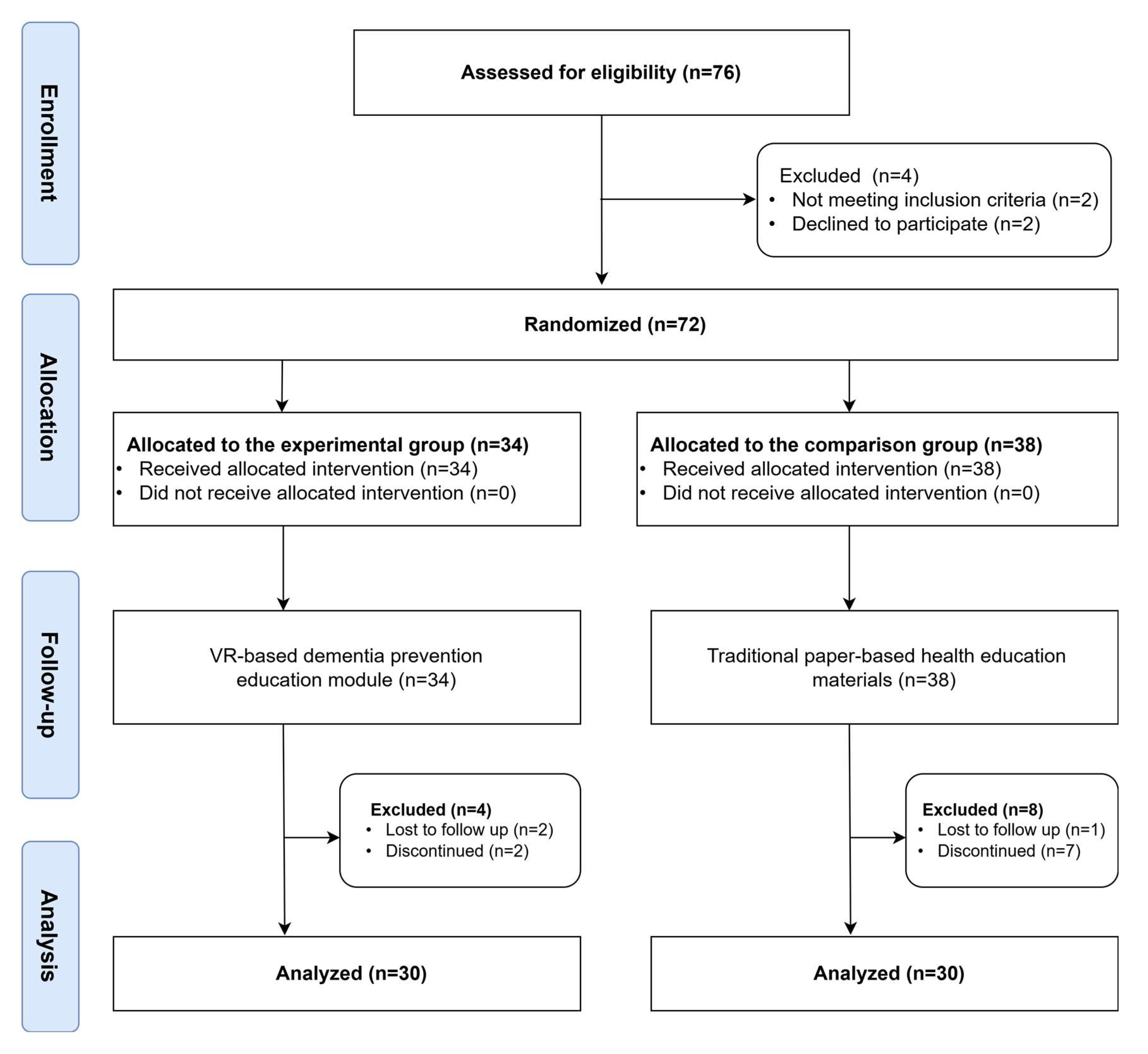

A total of 60 individuals were assessed for eligibility. Four participants were excluded, with two not meeting the inclusion criteria and two declining to participate. The remaining 56 participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (n = 30) or the comparison group (n = 30) using a simple coin toss method, which ensured an equal probability of assignment while maintaining the simplicity needed for a small-scale feasibility trial [

23]. The experimental group received the VR-based dementia prevention program using SRL strategies, while the comparison group received traditional routine, paper-based health education materials.

The estimated sample size required to achieve a statistical power of 0.9 at a significance level of 0.05 for a two-tailed test was 31 participants per group, based on an effect size (g = 0.38) derived from a meta-analysis on immersive virtual reality learning interventions [

24], which served as a reference point for this study. However, considering the pilot nature of this trial, which aimed primarily at assessing feasibility and preliminary intervention effects rather than establishing definitive efficacy, a smaller sample was considered acceptable. Ultimately, 53 participants were enrolled, including 36 in the experimental group and 17 in the comparison group.

2.2. Participants

The participants were older adults aged 65 and older, recruited from the previously mentioned community centers, long-term care facilities, and adult day care centers in northern Taiwan. Before enrollment, the research team provided participants with a comprehensive explanation of the study's purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) being an older adult aged 65 years or older and (b) having an Eight-item Informant Interview to Differentiate Aging and Dementia (AD8) score of 2 or higher, indicating potential cognitive impairment [

25]. Exclusion criteria included: (a) inability to use VR equipment, (b) diagnosis of severe mental disorders, (c) unconsciousness or serious physical conditions preventing participation, and (d) inability to communicate in Mandarin or Taiwanese.

2.3. Study Procedure

Figure 1 illustrates the entire study procedure. At the initiation of the study, trained research personnel provided participants with a thorough explanation of the study's objectives, procedures, and potential risks and benefits. Written informed consent was obtained prior to enrollment. Eligible participants were then randomly assigned to either the experimental group or the comparison group using a coin toss method to ensure equal allocation probability.

Before the intervention, all participants completed a pre-test assessment. The experimental group received the VR-based dementia prevention program, delivered through Meta Quest 3 VR headsets. This program included five structured units, covering dementia-related knowledge, disease management and prevention strategies, health literacy, self-efficacy, and acceptance of dementia. Participants engaged with the VR system in a controlled environment under the supervision of a facilitator, ensuring proper navigation and interaction with the learning material. The comparison group received standard, institution-provided traditional paper-based health education materials, as typically offered by their community centers, long-term care facilities, or adult day care centers.

After the intervention, all participants completed post-test assessments to evaluate changes in dementia knowledge, health literacy, and self-efficacy. The personnel conducting the assessments were blinded to group allocation to maintain data integrity and reduce bias. Any usability issues that arose during the VR sessions were documented for further analysis.

2.4. Intervention Development

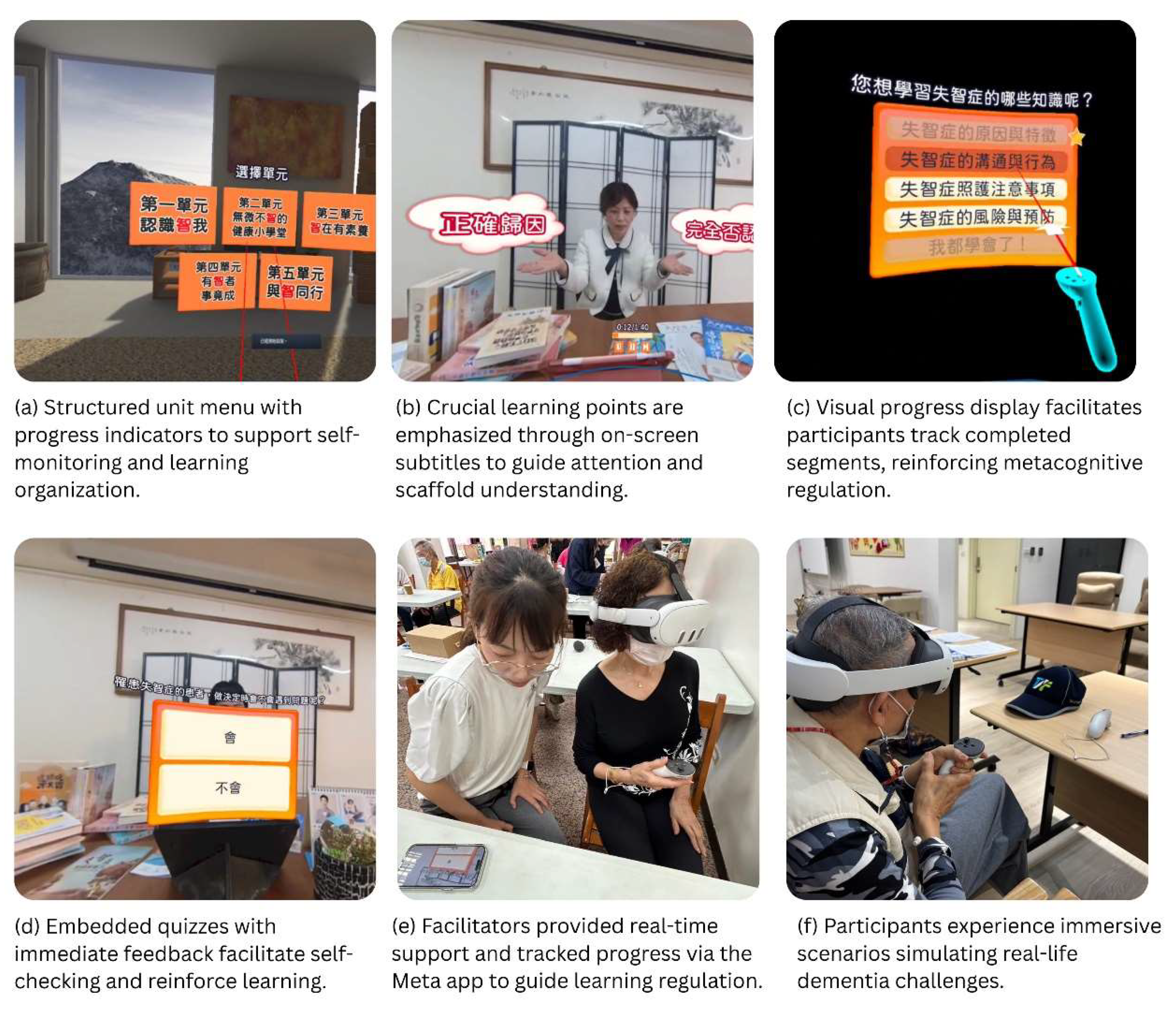

The VR-based dementia prevention program, based on SRL theory, was developed by an interdisciplinary team of specialists in dementia care, health education professionals, and VR technology developers. The content design integrated evidence-based dementia-care strategies into realistic, scenario-based storylines depicting everyday challenges commonly faced by individuals with dementia. Specifically, clear, achievable goals were explicitly provided for each of the five structured units, guiding participants' learning objectives. To enhance relatability and authenticity, dementia specialists crafted immersive scenarios reflecting daily situations frequently encountered by older adults with dementia, such as difficulties in communication or coping with unexpected behavioral issues.

The program consisted of five structured units addressing critical learning objectives shown in

Table 1, including insight, dementia-related knowledge, health literacy, self-efficacy enhancement, and acceptance of dementia. Delivered through the Meta Quest 3 VR headset (Meta Platforms, Inc., USA), the program provided an engaging, interactive learning environment.

Specifically, the program incorporated interactive quizzes embedded throughout VR sessions to enhance self-regulation processes by supporting accurate monitoring and promoting better learning outcomes [

26]. Each quiz provided immediate reinforcing feedback, including positive audio cues for correct responses and supportive explanations for incorrect responses. Additionally, key information and instructional prompts were presented as subtitles during the learning process, providing ongoing cognitive scaffolding and assisting participants in staying oriented across the various segments. This design is supported by empirical research revealing that combining timely feedback with structured prompts can improve learning performance and meta-comprehension accuracy over time [

27].

Following each VR session, trained facilitators guided participants through oral reflection exercises utilizing concept mapping techniques grounded in SRL [

28]. This process encouraged participants to summarize crucial points, raise relevant questions, and reflectively connect the educational content to their own lived experiences, promoting deeper cognitive integration and learning retention. Thus, the program's design fully embodied SRL principles, aimed explicitly at fostering deep learning and sustained cognitive and behavioral changes among older adults. The program content was rigorously reviewed by dementia care professionals and refined based on feedback from a prior pilot study [

29].

Figure 2 presents representative screenshots of the VR program illustrating SRL-informed interactive tasks and scenarios, along with photos demonstrating participants guided by research staff who monitored their progress through the Meta Horizon app.

2.4. Measurements

In addition to demographic information including age, gender, marital status, education level, past experience with dementia-related health education, relatives diagnosed with dementia and perceived health status, several instruments were used to assess dementia knowledge, health literacy, and self-efficacy.

2.4.1. Dementia-Related Knowledge

To evaluate participants' understanding of dementia, a 25-item questionnaire was developed, drawing from a comprehensive literature review and expert consultations. The questionnaire assessed knowledge across four key domains: (1) causes and characteristics, (2) communication and behavior, (3) care considerations, and (4) risks and health promotion. Participants responded to each statement using a true/false format, with an additional "don’t know" option to account for uncertainty. This approach ensured a valid assessment of dementia-related knowledge based on established research and clinical experience [

30]. The scale's content validity was confirmed by three independent professionals in dementia care and health education. Internal consistency reliability was excellent, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.98, indicating high internal coherence among items [

31].

2.4.2. Dementia-Related Health Literacy

Health literacy is crucial for dementia prevention, as it allows individuals to manage their health effectively [

32]. We assessed health literacy using a 20-item Likert-type scale, based on Nutbeam’s framework for functional, communicative, and critical health literacy [

33]. This scale measures participants' ability to access, understand, and apply health information related to dementia care. The scale was adapted from previous studies to ensure validity and reliability. The scale's internal consistency was confirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95.

2.4.3. Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is a key factor in empowering individuals to take action and engage in dementia care practices. To measure participants' confidence in managing dementia-related tasks, we utilized a 6-item Likert-type scale adapted from a previous study [

34]. The scale assessed participants' self-reported confidence in performing specific dementia care tasks. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89, confirming its reliability in this context.

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0. Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize demographic characteristics and baseline measures of dementia knowledge, health literacy, and self-efficacy. Independent sample t-tests and Chi-square tests were applied to examine group differences in demographic characteristics. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to compare the experimental and comparison groups on outcome measures over time, assessing the effects of the intervention. A significance level of p < 0.05 was set for all analyses.

2.6. Ethical Consideration

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of National Taiwan Normal University (Approval No.: 202212HM033).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

The final sample included 60 older adults, comprising 30 participants in the experimental group and 30 in the comparison group. The mean age was 76.83 years (SD = 6.70) for the experimental group and 76.67 years (SD = 7.01) for the comparison group. No significant age difference was found between the groups (t = -0.94, p = .925).

In both groups, the majority of participants were female (80.00%), and gender distribution did not differ significantly between groups (χ² = 0.000, p = 1.000). The distribution of marital status was similar across groups, with the majority being either widowed or married (χ² = 2.072, p = .558). Participants were fairly evenly distributed across levels, with the largest proportion in each group reporting elementary or high school education. No statistically significant differences in educational level were found between the groups (χ² = 0.328, p = .988).

Past experience with dementia-related health education was reported by 40.0% of the experimental group and 27.59% of the comparison group; however, this difference was not statistically significant (χ² = 1.014, p = .314). Similarly, while a higher proportion of participants in the comparison group reported having a relative diagnosed with dementia (24.14% vs. 6.67%), this difference was not significant (χ² = 4.109, p = .128).

Overall, no significant differences were found between the experimental and comparison groups in all measured sociodemographic variables, suggesting the groups were comparable at baseline. Detailed participant characteristics are summarized in

Table 2.

3.2. Intervention Effects on Dementia Knowledge, Health Literacy, and Self-Efficacy

Table 3 presents the Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) analysis results, comparing outcomes between the experimental and comparison groups. For dementia-related knowledge, a significant interaction effect was observed (β = 5.333, p < .001), indicating more significant gains in the experimental group following the intervention. Subdomain analyses further revealed significant group-by-time interaction effects in causes and characteristics (β = 1.767, p < .001), communication and behavior (β = 1.167, p = .008), care considerations (β = 1.400, p = .002), and risks and health promotion (β = 1.000, p = .005), suggesting broad improvements across knowledge categories.

In terms of health literacy, although the overall score did not show a significant interaction effect (β = 6.700, p = .138), the critical health literacy subdomain showed a significant group-by-time interaction (β = 3.700, p = .032), indicating the intervention’s potential in enhancing participants’ ability to evaluate and apply health information related to dementia critically. No significant effects were observed in the functional or interactive health literacy subdomains.

For self-efficacy, the group-by-time interaction was statistically significant (β = 4.200, p = .008), demonstrating a positive effect of the VR-based program on participants' confidence in managing dementia-related tasks and situations.

Overall, these findings suggest that the VR-based dementia prevention program effectively improved dementia knowledge across all major subdomains and significantly enhanced both critical health literacy and self-efficacy among older adults.

4. Discussion

This pilot randomized controlled trial evaluated the preliminary effectiveness of a VR-based dementia prevention program specifically informed by SRL principles among older adults with MCI. The baseline demographic characteristics did not differ significantly between the experimental and comparison groups, ensuring that the observed intervention effects were not due to differences in group composition. Findings suggest promising preliminary effectiveness, particularly in enhancing dementia knowledge, critical health literacy, and self-efficacy.

The intervention demonstrated significant improvements in dementia-related knowledge across all major subdomains, including causes and characteristics, communication and behavior, care considerations, and risks and health promotion. These findings support the view that immersive and scenario-based VR program—such as situations involving everyday challenges commonly faced by older adults with dementia (e.g., forgetting to turn off appliances)—can effectively strengthen emotional engagement and deepen cognitive processing in older adults. Prior studies have shown that emotionally relevant contexts enhance knowledge retention, especially in aging populations [

35]. Furthermore, the integration of structured prompts and immediate feedback within the VR quizzes likely contributed to improved learning performance by guiding learners’ attention and reinforcing self-monitoring processes. Research in SRL has demonstrated that combining prompts with timely feedback can significantly enhance meta-comprehension accuracy and learning outcomes across multiple sessions, particularly by facilitating learners' recalibration of internal monitoring and correction of misconceptions during learning [

27]. These interactive features, therefore, may have played a critical role in sustaining cognitive engagement and promoting more effective knowledge acquisition in this population.

Although overall health literacy scores did not reveal a significant improvement, a notable improvement was observed in the subdomain of critical health literacy. This indicates that the VR-based intervention effectively improved participants’ ability to analyze, evaluate, and apply dementia-related health information to real-life decision-making. These gains may be attributed not only to the immersive and engaging nature of VR—shown in previous research to support comprehension and communication in health education contexts [

36]—but also to the incorporation of SRL strategies within the program. Specifically, repeated self-monitoring through embedded quizzes, reflective concept mapping activities, and structured prompts likely fostered more active cognitive engagement and improved meta-cognitive awareness [26-28,37]. These findings echo prior research emphasizing that critical health literacy—more than self-efficacy or social support—is strongly linked to improved self-management behaviors in individuals with chronic conditions [

38], highlighting the potential of immersive, self-regulated learning tools in dementia education.

A particularly encouraging result was the notable improvement in self-efficacy seen in the experimental group. This aligns with previous literature indicating that self-efficacy is a vital predictor of sustained engagement in dementia-preventive behaviors. [

39]. The integration of interactive features, structured scaffolding, and quided reflective activities likely contributed to this gain by fostering learners’ confidence in applying what they learned. Recent meta-analytic evidence also confirms that SRL-based interventions can moderately enhance self-efficacy, especially when they scaffold self-monitoring and reflective evaluation [

40]. Moreover, these findings align with Zimmerman’s SRL framework, which highlights the reciprocal link between self-efficacy and strategy use throughout learning cycles [

41]. Additionally, this finding supports previous evidence that self-efficacy mediates the impact of health literacy on health behaviors and decision-making, particularly in older populations [

42].

These findings indicate that a brief SRL-informed VR intervention can lead to significant cognitive and behavioral improvements, especially in dementia knowledge, critical health literacy, and self-efficacy. The results highlight the significance of immersive, scaffolded learning environments tailored for cognitively vulnerable older adults, adding to the growing evidence that supports SRL-based digital health education in the relatively underexplored area of dementia prevention for individuals with MCI.

Despite promising findings, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, as a pilot study, the relatively small sample size restricts the generalizability and statistical power of the results. Future studies should employ larger, adequately powered samples to strengthen the conclusions. Second, participants were recruited from community centers, long-term care facilities, and adult day care centers in northern Taiwan, which limits geographic and cultural generalizability. Expanding future research to include diverse geographic regions and community settings may enhance external validity. Third, the current study assessed only short-term outcomes immediately after the intervention; future research should incorporate longitudinal assessments to examine sustained effects over time. Lastly, reliance on self-reported measures for outcomes such as health literacy and self-efficacy may introduce response bias. Incorporating objective assessments, like behavioral observation or task performance, could further validate the effectiveness of the VR intervention.

5. Conclusions

This pilot study provides preliminary evidence supporting the effectiveness of a VR-based dementia prevention education program grounded in SRL theory for older adults. The SRL-informed features included in this program—such as structured goal-setting, frequent self-monitoring through interactive quizzes with immediate reinforcing or supportive feedback, and guided reflection exercises facilitated by concept mapping—collectively contributed to significant improvements in dementia-related knowledge, critical health literacy, and self-efficacy among older adults with MCI. These findings suggest that immersive, interactive VR technologies have great potential to enhance dementia education and prevention efforts for aging populations. Further rigorous studies are needed to fully establish the sustained effectiveness and broader applicability of SRL-informed VR interventions in dementia prevention programs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C-H.C. and J-L.G.; methodology, J-L.G.; software, C-H.C.; validation, S-F.H., C-M.H., and J-L.G.; formal analysis, C-H.C.; investigation, L-H.K., T-H C., and Y-W.C.; resources, S-F.H. and Y-W.C.; data curation, C-H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C-H.C., and K-Y. H.; writing—review and editing, C-H.C. and J-L.G.; visualization, C-H.C.; supervision, J-L.G.; project administration, C-H.C., L-H.K., and J-L.G.; funding acquisition, K-Y. H., and J-L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Council Grant NSTC-112-2410-H-003-061-MY2.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Taiwan Normal University (Approval No. 202212HM033).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

This article was subsidized by the National Taiwan Normal University, Taiwan, Republic of China.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MCI |

Mild cognitive impairment |

| SRL |

Self-regulated learning |

References

- World Health Organizations. Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on Dec. 28).

- Alzheimer's Association. 2023 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2023, 19, 1598–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabins, P.V.; Mace, N.L.; Lucas, M.J. The impact of dementia on the family. Jama 1982, 248, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradfield, N.I. Mild cognitive impairment: diagnosis and subtypes. Clinical EEG and neuroscience 2023, 54, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguli, M.; Jia, Y.; Hughes, T.F.; Snitz, B.E.; Chang, C.C.H.; Berman, S.B.; Sullivan, K.J.; Kamboh, M.I. Mild cognitive impairment that does not progress to dementia: a population-based study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2019, 67, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y. A bibliometric analysis on the health behaviors related to mild cognitive impairment. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2024, 16, 1402347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, M.; Drašković, I.; Lucassen, P.; Vernooij-Dassen, M.; van Achterberg, T.; Rikkert, M.O. Effects of educational interventions on primary dementia care: A systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cruz, K.; Meikle, L.; White, M.; Herrmann, A.; McCallum, C.; Romero, L. Tailoring education of adults with cognitive impairment in the inpatient hospital setting: A scoping review. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 2021, 68, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charokar, K.; Dulloo, P. Self-directed Learning Theory to Practice: A Footstep towards the Path of being a Life-long Learne. J Adv Med Educ Prof 2022, 10, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadorin, L.; Grassetti, L.; Paoletti, E.; Cara, A.; Truccolo, I.; Palese, A. Evaluating self-directed learning abilities as a prerequisite of health literacy among older people: Findings from a validation and a cross-sectional study. Int J Older People Nurs 2020, 15, e12282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, F.-M.; Chen, G.-L.; Hsu, C.-T.; Wei, H.-C. Assessing the ability of self-directed learning as a prerequisite for active aging among middle-aged and older adult learners: cross-sectional study. Educational Gerontology 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P.R. A conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students. Educational psychology review 2004, 16, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview. Educational psychologist 1990, 25, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.D.; Persky, A.M. Developing self-directed learners. American journal of pharmaceutical education 2020, 84, 847512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlomann, A.; Even, C.; Hammann, T. How older adults learn ICT—guided and self-regulated learning in individuals with and without disabilities. Frontiers in Computer Science 2022, 3, 803740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, S.; Lan, Y. The research on the self-regulation strategies support for virtual interaction. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, 83, 49723–49747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Oh, J.; Park, K. Self-Regulated Learning Strategies for Nursing Students: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 9058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.Y.W.; Yin, Y.-H.; Kor, P.P.K.; Cheung, D.S.K.; Zhao, I.Y.; Wang, S.; Su, J.J.; Christensen, M.; Tyrovolas, S.; Leung, A.Y. The effects of immersive virtual reality applications on enhancing the learning outcomes of undergraduate health care students: systematic review with meta-synthesis. Journal of medical Internet research 2023, 25, e39989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.; Gamito, P.; Souto, T.; Conde, R.; Ferreira, M.; Corotnean, T.; Fernandes, A.; Silva, H.; Neto, T. Virtual reality-based cognitive stimulation on people with mild to moderate dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot randomized controlled trial. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18, 5290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, L.; Appel, E.; Kisonas, E.; Lewis-Fung, S.; Pardini, S.; Rosenberg, J.; Appel, J.; Smith, C. Evaluating the impact of virtual reality on the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and quality of life of inpatients with dementia in acute care: randomized controlled trial (VRCT). Journal of Medical Internet Research 2024, 26, e51758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, O.; Pang, Y.; Kim, J.-H. The effectiveness of virtual reality for people with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: a meta-analysis. BMC psychiatry 2019, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manera, V.; Chapoulie, E.; Bourgeois, J.; Guerchouche, R.; David, R.; Ondrej, J.; Drettakis, G.; Robert, P. A feasibility study with image-based rendered virtual reality in patients with mild cognitive impairment and dementia. PloS one 2016, 11, e0151487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, M.; Yu, Z.; Odum, S. Randomization Strategies. In Introduction to Surgical Trials, Lyman, S., Ayeni, O.R., Koh, J.L., Nakamura, N., Karlsson, J., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Coban, M.; Bolat, Y.I.; Goksu, I. The potential of immersive virtual reality to enhance learning: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review 2022, 36, 100452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, K.; Green, C.; McShane, R.; Noel-Storr, A.H.; Stott, D.J.; Anwer, S.; Sutton, A.J.; Burton, J.K.; Quinn, T.J. AD-8 for detection of dementia across a variety of healthcare settings. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordet, C.; Fernandez, J.; Jamet, E. The effects of embedded quizzes on self-regulated processes and learning performance during a multimedia lesson. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 2025, 41, e13083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Ma, X. The Impact of Prompts and Feedback on the Performance during Multi-Session Self-Regulated Learning in the Hypermedia Environment. Journal of Intelligence 2023, 11, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Hwang, G.-J. A structured reflection-based graphic organizer approach for professional training: A technology-supported AQSR approach. Computers & Education 2022, 183, 104502. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, L.-H.; Chang, C.-H.; Huang, S.-F.; Chien, H.-C.; Huang, C.-M.; Guo, J.-L. User Experience Evaluation of a Spherical Video-based Virtual Reality Dementia Educational Program among Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Consumer Electronics-Taiwan (ICCE-Taiwan); 2024; pp. 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Annear, M.J.; Toye, C.; Elliott, K.-E.J.; McInerney, F.; Eccleston, C.; Robinson, A. Dementia knowledge assessment scale (DKAS): confirmatory factor analysis and comparative subscale scores among an international cohort. BMC geriatrics 2017, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F.; Thorpe, C.T. Scale development: Theory and applications; Sage publications: 2021.

- Oliveira, D.; Bosco, A.; di Lorito, C. Is poor health literacy a risk factor for dementia in older adults? Systematic literature review of prospective cohort studies. Maturitas 2019, 124, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health promotion international 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-H.; Huang, C.-M.; Sheu, J.-J.; Liao, J.-Y.; Hsu, H.-P.; Wang, S.-W.; Guo, J.-L. Examining the effectiveness of 3D virtual reality training on problem-solving, self-efficacy, and teamwork among inexperienced volunteers helping with drug use prevention: randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical Internet research 2021, 23, e29862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, G.; Lu, A. Effects of immersive and non-immersive virtual reality-based rehabilitation training on cognition, motor function, and daily functioning in patients with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Rehabilitation 2024, 38, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Kruk, S.R.; Zielinski, R.; MacDougall, H.; Hughes-Barton, D.; Gunn, K.M. Virtual reality as a patient education tool in healthcare: A scoping review. Patient Education and Counseling 2022, 105, 1928–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.-W.; Li-Yuan, H.; Gwo-Jen, H.; Xiu-Wei, Z.; Chu-Nu, B.; and Fu, Q.-K. A concept mapping-based self-regulated learning approach to promoting students’ learning achievement and self-regulation in STEM activities. Interactive Learning Environments 2023, 31, 7159–7181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.T.H.; Bonner, A. Exploring the relationships between health literacy, social support, self-efficacy and self-management in adults with multiple chronic diseases. BMC Health Services Research 2023, 23, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cho, E.; Kim, H.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, E.; Ye, B.S. The development and evaluation of a self-efficacy enhancement program for older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Applied Nursing Research 2023, 73, 151726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. The effectiveness of self-regulated learning (SRL) interventions on L2 learning achievement, strategy employment and self-efficacy: A meta-analytic study. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 1021101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follmer, D.J. Implementing a Simple, Scalable Self-Regulated Learning Intervention to Promote Graduate Learners’ Statistics Self-Efficacy and Concept Knowledge. Journal of Statistics and Data Science Education 2023, 31, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Willoughby, J.; Zhou, R. Associations of Health Literacy, Social Media Use, and Self-Efficacy With Health Information–Seeking Intentions Among Social Media Users in China: Cross-sectional Survey. J Med Internet Res 2021, 23, e19134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).