Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

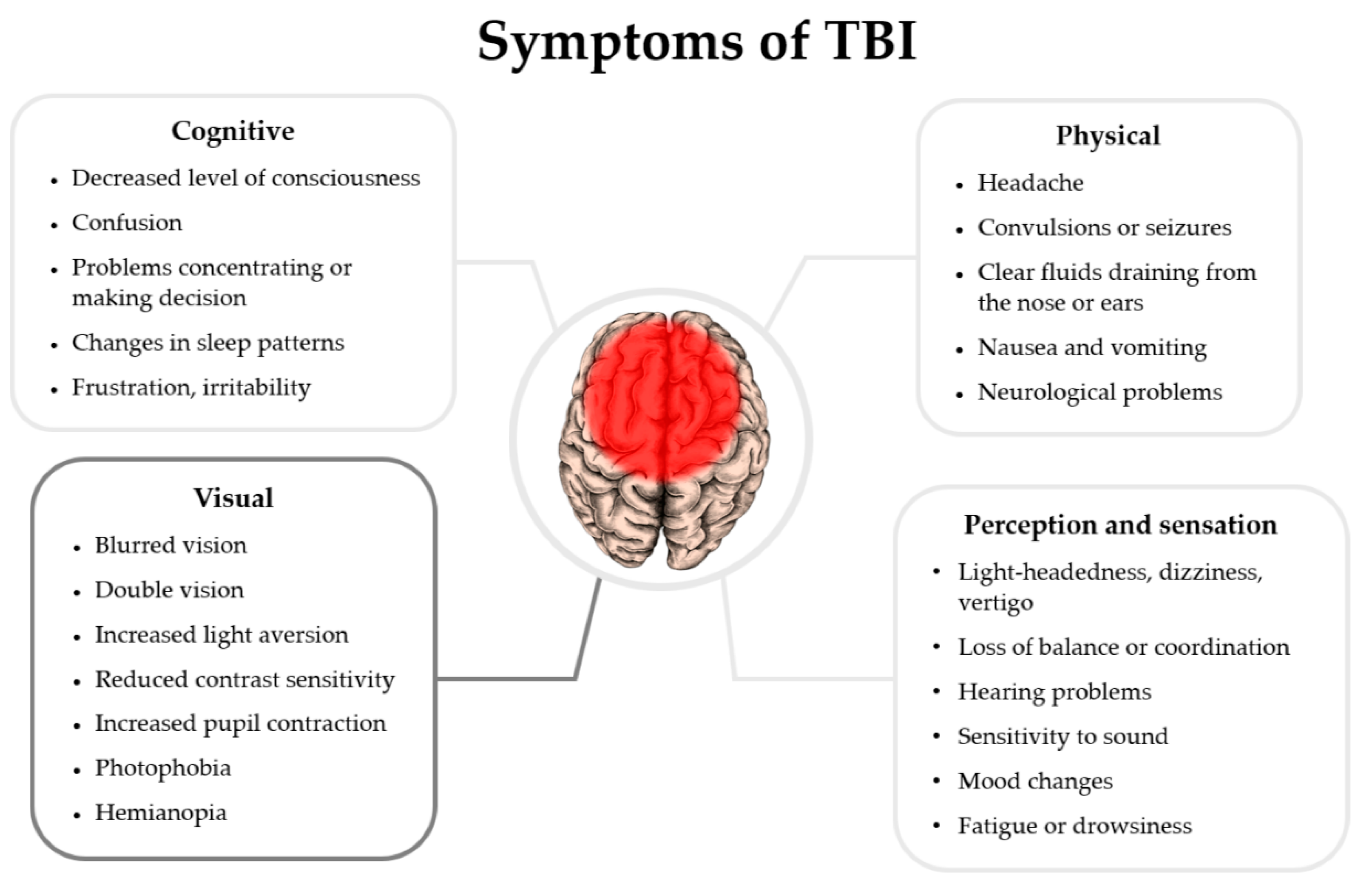

2.1. Manifestations Traumatic Brain Injury in Patients

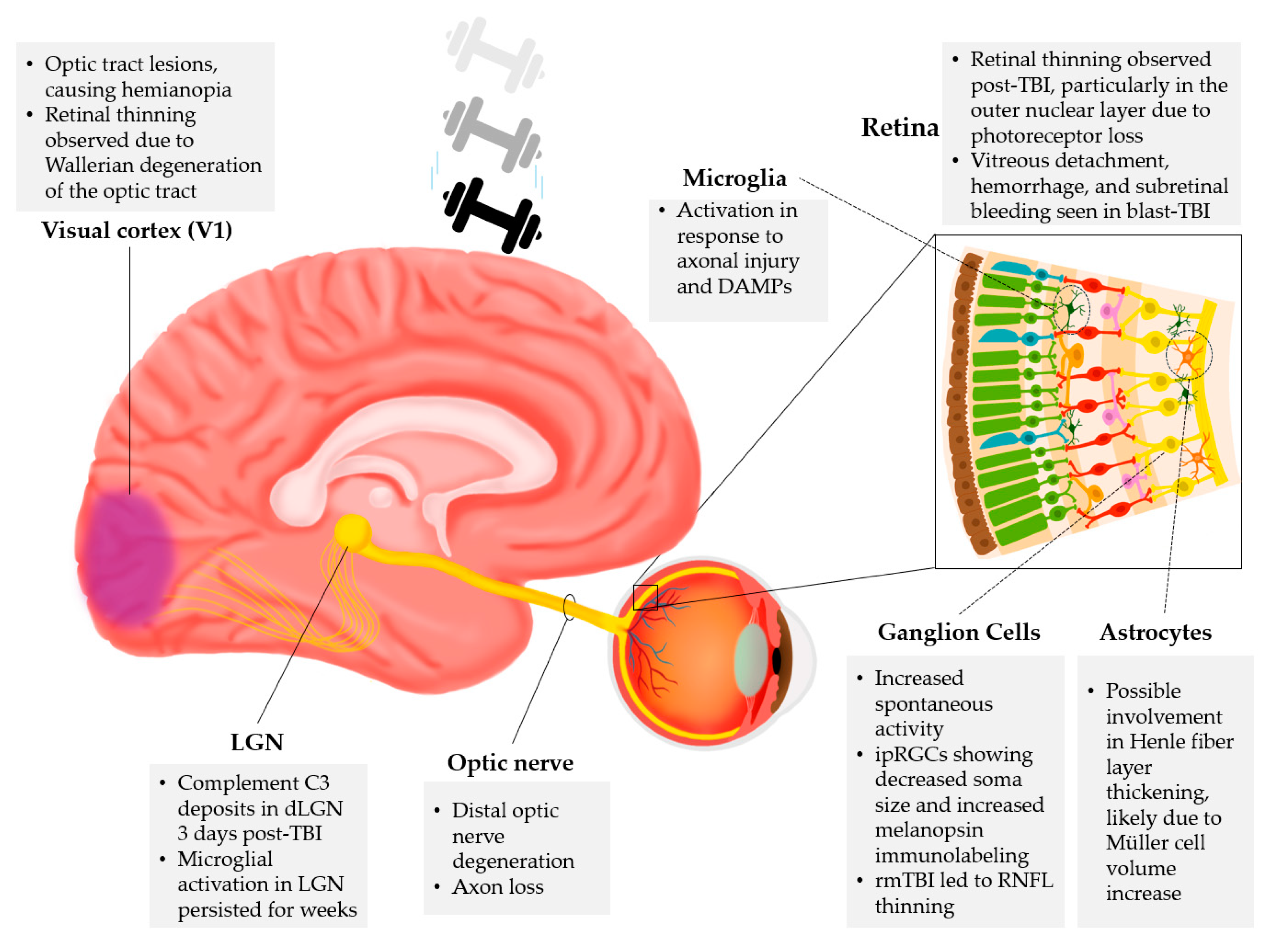

2.2. Effects of TBI on the Visual System

2.3. Cellular and Molecular Markers of TBI in the Retina

| Marker | Function | Study |

|---|---|---|

| GFAP (Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein) | Indicates Müller glia activation in the retina post-TBI or acoustic blast overpressure | [17,31,32] |

| IBA1 (Ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1) | Reflects microglial activation and inflammation post-TBI | [1,17,31] |

| CD68 (Cluster of Differentiation 68) | Marker of pro-inflammatory microglial activation and indicates phagocytic response in traumatic axonopathy | [17,37] |

| Phosphorylated Tau | Indicates neurodegeneration; associated with neurofibrillary tangles | [17] |

| LPA (Lysophosphatidic acid) | Induces inflammatory processes, astrocyte proliferation, and tau phosphorylation | [33,41,42] |

| IL-1B, IL-1a, IL-6, TNF (Interleukin; Tumor Necrosis Factor) | Cytokines involved in inflammation and oxidative stress post-TBI | [31] |

| KLF4 (Kruppel-like factor 4) | Triggers pro-apoptotic p53 signaling and inhibits pro-survival STAT3 signaling in RGCs | [34] |

| CCL20 ( Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20) | Involved in neurodegeneration and inflammation post-TBI | [35] |

| Caspase-3 | Marker of apoptosis, expressed in astrocytes in retinal damage | [36] |

| Complement C3 | Deposits in retinogeniculate synapses post-TBI; inhibition is neuroprotective | [27] |

| β-amyloid and 4HNE (4-hydroxy-trans-2-nonenal) | Oxidative stress markers post-TBI | [38] |

| PTEN ( phosphatase and tensin homolog) | Downregulation promotes regeneration of α RGCs | [40] |

| Osteopontin and IGF-1 ( insulin-like growth factor 1) | Enhances RGC regeneration | [40] |

2.4. Possible Translational Implementation of Retinal Markers in TBI

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Methods

Acknowledgment

References

- Honig, M. G.; Del Mar, N. A.; Henderson, D. L.; Ragsdale, T. D.; Doty, J. B.; Driver, J. H.; Li, C.; Fortugno, A. P.; Mitchell, W. M.; Perry, A. M.; Moore, B. M.; Reiner, A. Amelioration of Visual Deficits and Visual System Pathology after Mild TBI via the Cannabinoid Type-2 Receptor Inverse Agonism of Raloxifene. Exp. Neurol. 2019, 322, 113063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honig, M. G.; Del Mar, N. A.; Henderson, D. L.; O’Neal, D.; Yammanur, M.; Cox, R.; Li, C.; Perry, A. M.; Moore, B. M.; Reiner, A. Raloxifene, a Cannabinoid Type-2 Receptor Inverse Agonist, Mitigates Visual Deficits and Pathology and Modulates Microglia after Ocular Blast. Exp. Eye Res. 2022, 218, 108966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, P. A.; Gronwall, D. M. A. Sensitivity to Light and Sound Following Minor Head Injury. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1984, 69, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuhas, P. T.; Shorter, P. D.; McDaniel, C. E.; Earley, M. J.; Hartwick, A. T. E. Blue and Red Light-Evoked Pupil Responses in Photophobic Subjects with TBI. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2017, 94, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemke, S.; Cockerham, G. C.; Glynn-Milley, C.; Lin, R.; Cockerham, K. P. Automated Perimetry and Visual Dysfunction in Blast-Related Traumatic Brain Injury. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decramer, T.; Van Keer, K.; Stalmans, P.; Dupont, P.; Sunaert, S.; Theys, T. Tracking Posttraumatic Hemianopia. J. Neurol. 2018, 265, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, H. S.; Sassani, M.; Hyder, Y.; Mitchell, J. L.; Thaller, M.; Mollan, S. P.; Sinclair, A. J.; mTBI Predict, Consortium; Sinclair, A.; Finch, A.; Hampshire, A.; Sitch, A.; Mazaheri, A.; Bagshaw, A.; Palmer, A.; Strom, A.; Waitt, A.; Yiangou, A.; Abdel-Hay, A.; Bennett, A.; Clark, A.; Hunter, A.; Seemungal, B.; Witton, C.; Dooley, C.; Bird, D.; Fernandez-Espejo, D.; Smith, D.; Ford, D.; Sherwood, D.; Holding, D.; Wilson, D.; Palmer, E.; Golding, J.; Dehghani, H.; Park, H.; Lyons, H.; Smith, H.; Brunger, H.; Ellis, H.; Idrees, I.; Varley, I.; Hubbard, J.; Cao, J.; Deeks, J.; Mitchell, J.; Novak, J.; Pringle, J.; Terry, J.; Rogers, J.; Read, T.; Fildes, J.; Mullinger, K.; Hill, L.; Aurisicchio, M.; Thaller, M.; Wilson, M.; Pearce, M.; Sassani, M.; Brookes, M.; Mahmud, M.; Rayhan, R.; Jenkinson, N.; Karavitaki, N.; Capewell, N.; Grech, O.; Jensen, O.; Hellyer, P.; Woodgate, P.; Coleman, S.; Reynolds, R.; Blanch, R. J.; Morris, K.; Ottridge, R.; Upthegrove, R.; Dardis, R.; Arachchige, R. W.; Berhane, S.; Lucas, S.; Prosser, S.; Sharifi, S.; Dharm-Datta, S.; Mollan, S.; Ellmers, T.; Ghafari, T.; Goldstone, T.; Hawa, W.; Gao, Y.; Blanch, R. J. A Systematic Review of Optical Coherence Tomography Findings in Adults with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Eye 2024, 38, 1077–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mufti, O.; Mathew, S.; Harris, A.; Siesky, B.; Burgett, K. M.; Verticchio Vercellin, A. C. Ocular Changes in Traumatic Brain Injury: A Review. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 30, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L. P.; Roghair, A. M.; Gilkes, N. J.; Bassuk, A. G. Visual Outcomes in Experimental Rodent Models of Blast-Mediated Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 659576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Tang, X.; Mohapatra, S. S.; Mohapatra, S. Vision Impairment after Traumatic Brain Injury: Present Knowledge and Future Directions. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 30, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A. K.; Rich, W.; Reilly, M. A. Oxidative Stress in the Brain and Retina after Traumatic Injury. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1021152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodnar, C. N.; Watson, J. B.; Higgins, E. K.; Quan, N.; Bachstetter, A. D. Inflammatory Regulation of CNS Barriers After Traumatic Brain Injury: A Tale Directed by Interleukin-1. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 688254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauchman, S. H.; Albert, J.; Pinkhasov, A.; Reiss, A. B. Mild-to-Moderate Traumatic Brain Injury: A Review with Focus on the Visual System. Neurol. Int. 2022, 14, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Qiu, T.; Xiao, Z. Photophobia in Headache Disorders: Characteristics and Potential Mechanisms. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 4055–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Nguyen, J. V.; Lehar, M.; Menon, A.; Rha, E.; Arena, J.; Ryu, J.; Marsh-Armstrong, N.; Marmarou, C. R.; Koliatsos, V. E. Repetitive Mild Traumatic Brain Injury with Impact Acceleration in the Mouse: Multifocal Axonopathy, Neuroinflammation, and Neurodegeneration in the Visual System. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 275, 436–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institue of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). National Institue of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/traumatic-brain-injury-tbi#.

- Mammadova, N.; Ghaisas, S.; Zenitsky, G.; Sakaguchi, D. S.; Kanthasamy, A. G.; Greenlee, J. J.; West Greenlee, M. H. Lasting Retinal Injury in a Mouse Model of Blast-Induced Trauma. Am. J. Pathol. 2017, 187, 1459–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fox, M. A.; Povlishock, J. T. Diffuse Traumatic Axonal Injury in the Optic Nerve Does Not Elicit Retinal Ganglion Cell Loss. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2013, 72, 768–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutca, L. M.; Stasheff, S. F.; Hedberg-Buenz, A.; Rudd, D. S.; Batra, N.; Blodi, F. R.; Yorek, M. S.; Yin, T.; Shankar, M.; Herlein, J. A.; Naidoo, J.; Morlock, L.; Williams, N.; Kardon, R. H.; Anderson, M. G.; Pieper, A. A.; Harper, M. M. Early Detection of Subclinical Visual Damage After Blast-Mediated TBI Enables Prevention of Chronic Visual Deficit by Treatment With P7C3-S243. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 8330–8341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, M. M.; Gramlich, O. W.; Elwood, B. W.; Boehme, N. A.; Dutca, L. M.; Kuehn, M. H. Immune Responses in Mice after Blast-Mediated Traumatic Brain Injury TBI Autonomously Contribute to Retinal Ganglion Cell Dysfunction and Death. Exp. Eye Res. 2022, 225, 109272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern-Green, E. A.; Klimo, K. R.; Day, E.; Shelton, E. R.; Robich, M. L.; Jordan, L. A.; Racine, J.; VanNasdale, D. A.; McDaniel, C. E.; Yuhas, P. T. Henle Fiber Layer Thickening and Deficits in Objective Retinal Function in Participants with a History of Multiple Traumatic Brain Injuries. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1330440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J. W.; Hills, N. K.; Bakall, B.; Fernandez, B. Indirect Traumatic Optic Neuropathy in Mild Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honig, M. G.; Del Mar, N. A.; Henderson, D. L.; O’Neal, D.; Doty, J. B.; Cox, R.; Li, C.; Perry, A. M.; Moore, B. M.; Reiner, A. Raloxifene Modulates Microglia and Rescues Visual Deficits and Pathology After Impact Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 701317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Palacios, K.; Vásquez-García, S.; Fariyike, O. A.; Robba, C.; Rubiano, A. M.; the noninvasive ICP monitoring international consensus, group; Taccone, F. S.; Rasulo, F.; Badenes, R. R.; Menon, D.; Sarwal, A. A.; Cardim, D. D.; Czosnyka, M.; Hirzallah, M.; Geeraerts, T.; Bouzat, P.; Lochner, P. G.; Aries, M.; Wong, Y. L.; Abulhassan, Y.; Sung, G.; Prabhakar, H.; Shrestha, G.; Bustamante, L.; Jibaja, M.; Pinedo, J.; Sanchez, D.; Mendez, J. M.; Vásquez, F.; Shukla, D. P.; Worku, G.; Tirsit, A.; Indiradevi, B.; Shabani, H.; Adeleye, A.; Munusamy, T.; Ain, A.; Paiva, W.; Godoy, D.; Brasil, S.; Robba, C.; Rubiano, A.; Vásquez-García, S. Using Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter for Intracranial Pressure (ICP) Monitoring in Traumatic Brain Injury: A Scoping Review. Neurocrit. Care 2024, 40, 1193–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzekov, R.; Quezada, A.; Gautier, M.; Biggins, D.; Frances, C.; Mouzon, B.; Jamison, J.; Mullan, M.; Crawford, F. Repetitive Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Causes Optic Nerve and Retinal Damage in a Mouse Model: J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2014, 73, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, L. P.; Newell, E. A.; Mahajan, M.; Tsang, S. H.; Ferguson, P. J.; Mahoney, J.; Hue, C. D.; Vogel, E. W.; Morrison, B.; Arancio, O.; Nichols, R.; Bassuk, A. G.; Mahajan, V. B. Acute Vitreoretinal Trauma and Inflammation after Traumatic Brain Injury in Mice. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2018, 5, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borucki, D. M.; Rohrer, B.; Tomlinson, S. Complement Propagates Visual System Pathology Following Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morriss, N. J.; Conley, G. M.; Hodgson, N.; Boucher, M.; Ospina-Mora, S.; Fagiolini, M.; Puder, M.; Mejia, L.; Qiu, J.; Meehan, W.; Mannix, R. Visual Dysfunction after Repetitive Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in a Mouse Model and Ramifications on Behavioral Metrics. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 2881–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elenberger, J.; Kim, B.; De Castro-Abeger, A.; Rex, T. S. Connections between Intrinsically Photosensitive Retinal Ganglion Cells and TBI Symptoms. Neurology 2020, 95, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, C. W.; Likova, L. T. Brain Trauma Impacts Retinal Processing: Photoreceptor Pathway Interactions in Traumatic Light Sensitivity. Doc. Ophthalmol. 2022, 144, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L. P.; Woll, A. W.; Wu, S.; Todd, B. P.; Hehr, N.; Hedberg-Buenz, A.; Anderson, M. G.; Newell, E. A.; Ferguson, P. J.; Mahajan, V. B.; Harper, M. M.; Bassuk, A. G. Modulation of Post-Traumatic Immune Response Using the IL-1 Receptor Antagonist Anakinra for Improved Visual Outcomes. J. Neurotrauma 2020, 37, 1463–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, L. A.; Ramachandra Rao, S.; Allen, R. S.; Motz, C. T.; Pardue, M. T.; Fliesler, S. J. Retinal Gliosis and Phenotypic Diversity of Intermediate Filament Induction and Remodeling upon Acoustic Blast Overpressure (ABO) Exposure to the Rat Eye. Exp. Eye Res. 2023, 234, 109585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arun, P.; Rossetti, F.; DeMar, J. C.; Wang, Y.; Batuure, A. B.; Wilder, D. M.; Gist, I. D.; Morris, A. J.; Sabbadini, R. A.; Long, J. B. Antibodies Against Lysophosphatidic Acid Protect Against Blast-Induced Ocular Injuries. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 611816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, D.; Zeng, T.; Ren, J.; Wang, K.; Jin, Y.; Zhou, L.; Gao, L. KLF 4 Knockdown Attenuates TBI -Induced Neuronal Damage through P53 and JAK - STAT 3 Signaling. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2017, 23, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Tang, X.; Han, J. Y.; Mayilsamy, K.; Foran, E.; Biswal, M. R.; Tzekov, R.; Mohapatra, S. S.; Mohapatra, S. CCL20-CCR6 Axis Modulated Traumatic Brain Injury-Induced Visual Pathologies. J. Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács-Öller, T.; Zempléni, R.; Balogh, B.; Szarka, G.; Fazekas, B.; Tengölics, Á. J.; Amrein, K.; Czeiter, E.; Hernádi, I.; Büki, A.; Völgyi, B. Traumatic Brain Injury Induces Microglial and Caspase3 Activation in the Retina. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandris, A. S.; Lee, Y.; Lehar, M.; Alam, Z.; McKenney, J.; Perdomo, D.; Ryu, J.; Welsbie, D.; Zack, D. J.; Koliatsos, V. E. Traumatic Axonal Injury in the Optic Nerve: The Selective Role of SARM1 in the Evolution of Distal Axonopathy. J. Neurotrauma 2023, 40, 1743–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, K.; Kecova, H.; Hernandez-Merino, E.; Kardon, R. H.; Harper, M. M. Retinal Ganglion Cell Damage in an Experimental Rodent Model of Blast-Mediated Traumatic Brain Injury. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ryu, J.; Nguyen, J. V.; Arena, J.; Rha, E.; Vranis, P.; Hitt, D.; Marsh-Armstrong, N.; Koliatsos, V. E. Evidence for Accelerated Tauopathy in the Retina of Transgenic P301S Tau Mice Exposed to Repetitive Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Exp. Neurol. 2015, 273, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crair, M. C.; Mason, C. A. Reconnecting Eye to Brain. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 10707–10722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shano, S.; Moriyama, R.; Chun, J.; Fukushima, N. Lysophosphatidic Acid Stimulates Astrocyte Proliferation through LPA1. Neurochem. Int. 2008, 52, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayas, C. L.; Ariaens, A.; Ponsioen, B.; Moolenaar, W. H. GSK-3 Is Activated by the Tyrosine Kinase Pyk2 during LPA1 -Mediated Neurite Retraction. Mol. Biol. Cell 2006, 17, 1834–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C. K.; Stagner, A. M. The Eyes Have It: How Critical Are Ophthalmic Findings to the Diagnosis of Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma? Semin. Ophthalmol. 2023, 38, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Fan, W.; Cai, Y.; Wu, Q.; Mo, L.; Huang, Z.; Huang, H. Protective Effects of Taurine in Traumatic Brain Injury via Mitochondria and Cerebral Blood Flow. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 2169–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, M. M.; Hedberg-Buenz, A.; Herlein, J.; Abrahamson, E. E.; Anderson, M. G.; Kuehn, M. H.; Kardon, R. H.; Poolman, P.; Ikonomovic, M. D. Blast-Mediated Traumatic Brain Injury Exacerbates Retinal Damage and Amyloidosis in the APPswePSENd19e Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, 2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, T.; Thamaraikani, T.; Vellapandian, C. A Review of the Retinal Impact of Traumatic Brain Injury and Alzheimer’s Disease: Exploring Inflammasome Complexes and Nerve Fiber Layer Alterations. Cureus 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar Das, N.; Das, M. Structural Changes in Retina (Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer) Following Mild Traumatic Brain Injury and Its Association with Development of Visual Field Defects. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2022, 212, 107080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banbury, C.; Styles, I.; Eisenstein, N.; Zanier, E. R.; Vegliante, G.; Belli, A.; Logan, A.; Goldberg Oppenheimer, P. Spectroscopic Detection of Traumatic Brain Injury Severity and Biochemistry from the Retina. Biomed. Opt. Express 2020, 11, 6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeti, F.; Carle, C. F.; Jaros, R. K.; Rohan, E. M. F.; Waddington, G.; Lueck, C. J.; Hughes, D.; Maddess, T. Objective Perimetry in Sporting-Related Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 1053–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Y.; Zhang, M.; Lee, D. M. W.; Snyder, V. C.; Raghuraman, R.; Gofas-Salas, E.; Mecê, P.; Yadav, S.; Tiruveedhula, P.; Grieve, K.; Sahel, J.-A.; Errera, M.-H.; Rossi, E. A. Label-Free Imaging of Inflammation at the Level of Single Cells in the Living Human Eye. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2024, 4, 100475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, D. X.; Kovalick, K.; Liu, Z.; Chen, C.; Saeedi, O. J.; Harrison, D. M. Cellular-Level Visualization of Retinal Pathology in Multiple Sclerosis With Adaptive Optics. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2023, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, A. Y.; Eldahshan, W.; Narayanan, S. P.; Caldwell, R. W.; Caldwell, R. B. Arginase Pathway in Acute Retina and Brain Injury: Therapeutic Opportunities and Unexplored Avenues. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).