Introduction

The skin is an externally visible organ whose changes contribute to how a person is affected psychologically and socially. Dr. Albert M. Klingman and Dr. Carol Koblenzer in Dermatological Clinics expressed: “We need to look at skin aging in an entirely different light, with special emphasis on the psychological distresses caused by deterioration in appearance” [

1]. Current consumer culture, through media and advertising, sends a strong message about the will to get older without the signs of aging, leading to an aging-related phenomenon with a critical psychosocial component: the increasing emphasis on a youthful appearance, with more individuals becoming concerned about skin quality [

2]. The appearance of the face dramatically influences an individual’s personal and social identity, in which youthful appearance is associated with increased self-esteem and improved social relations. Two studies on volunteers with mild-to-severe photodamaged skin, done at Johns Hopkins University [

3] and the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor [

4], received high scores in the interpersonal sensitivity and phonic anxiety subscales of the Brief Symptom Inventory. This high score indicates that the volunteers with mild-to-severe photodamaged skin were experiencing uneasiness during their interpersonal interactions. This increase in social anxiety raises the concern of dermatological researchers and professionals, leading to targeting skin aging to alleviate these psychological components. Aging of the skin, including signs of hyperpigmentation, is influenced by internal and external factors.

Skin aging results from chronological aging, when the skin changes are caused by internal factors of the body, and photoaging, which is a skin change caused by external factors, the most common being exposure to sun ultraviolet (UV) rays [

5]. During skin aging, the skin’s structural and functional integrity is changed or disturbed, leading to hyperpigmentation [

6]. Hyperpigmentation is a common dermatological condition in which the skin generally becomes darker and is an umbrella term that includes various skin discoloration disorders such as solar lentigines (commonly referred to as age spots or sun spots), melasma, and post-inflammatory acne marks [

7,

8]. Although hyperpigmentation is a common cosmetic complaint in most skin types, it is prominently found in middle-aged women and in the population with III-VI Fitzpatrick skin types. Hyperpigmentation is not considered a harmful disorder (except in the cases when melanoma has been diagnosed); however, it can affect the quality of life of patients by influencing their emotional and psychological health. In the cosmetic and skincare fields, various active ingredients help minimize the signs of aging (either by preventing or treating them), such as ones primarily applied by topical route in creams, gels, or ointments [

9]. Nonetheless, topical treatments, while effective, can also have side effects, such as skin drying, irritation, sensitization, peeling, or hypopigmentation, which should be considered when choosing a treatment plan.

Arbutin is a skin-lightening active ingredient that, in the last 30 years, has been used as a safer alternative to hydroquinone [

10]. It is a D-glucose molecule bonded to hydroquinone that can be plant-extracted, bioconverted from hydroquinone, or prepared by chemical synthesis. A maximum dose of 7% [

11] arbutin in face products provides skin-lightening benefits without the risk of severe side effects that hydroquinone produces, such as irritation and melanocytotoxicity [

12]. Two mechanisms of action are proposed for arbutin’s efficacy in reducing cellular melanin. First, arbutin may inhibit the maturation of newly synthesized tyrosinase (TYR) from the melanogenesis pathway without reducing its protein levels [

10]. The other proposed mechanism is that arbutin inhibits the catalytic activity of TYR in the late stages of melanocyte differentiation [

10]. Even though additional research needs to be done to establish arbutin’s correct mechanism of action, it is well-known that arbutin’s inhibitory effect against melanin synthesis is more potent than other commonly used skin-lightening agents such as kojic or L-ascorbic acid. Apart from inhibiting TYR directly, arbutin has antioxidant properties that reduce reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels produced by the melanogenic pathway. All this evidence suggests that arbutin is a promising skin-lightening active with antioxidant effects [

10].

Another promising active for skin-lightening is niacinamide [

13]. Niacinamide is a highly safe ingredient that is well tolerated by the skin at commonly used concentrations (<5%) and is a critical player in skincare routines [

14]. The amide form of water-soluble vitamin B3 is the physiologically active analog that the cell absorbs to prevent skin aging and brighten tone. It achieves this by inhibiting the transfer of melanosomes to the surrounding keratinocytes and disrupting the cell-signaling pathway between melanocytes and keratinocytes. It also prevents skin aging by promoting dermal fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis while preventing their degradation. Additionally, niacinamide increases the synthesis of involucrin and filaggrin in the epidermal layer, strengthening the structural and functional skin barrier that becomes disturbed with aging [

13].

In summary, arbutin and niacinamide play a key role for improving the external appearance of aging skin, whether due to chronological aging, photoaging, or hyperpigmentation. In this study, we incorporated 2% Arbutin and 3% Niacinamide into our Facial Toner to assess its efficacy in improving the appearance of pores, uneven skin texture, and brightness.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Material

In this study, we tested the efficacy of a facial toner containing 2.0% (w/w) Arbutin and 3.0% (w/w) Niacinamide (Good Molecules Niacinamide Brightening Toner, hereafter referred to as “Facial Toner”), which had been previously assessed for topical safety in a Human Repeat Insult Patch Test (HRIPT) with fifty-five healthy adult volunteers. The HRIPT resulted in no irritation or sensitization events. The test formulation also contains Water (q.s.p. 100% w/w), Glycerin (6.7% w/w), 1,2-Hexanediol (2.2% w/w), Propanediol (2.0% w/w), Betaine (0.5% w/w), Glycyrrhiza Glabra (Licorice) Root Extract (0.1% w/w), 3-O-Ethyl Ascorbic Acid (0.1% w/w), Ethylhexylglycerin (0.1% w/w), Carbomer (0.06% w/w), Tromethamine (0.04% w/w), Trisodium Ethylenediamine Disuccinate (0.02% w/w), Theobroma Cacao (Cocoa) Seed Extract (35 ppm w/w), Sodium Hyaluronate (15 ppm w/w), Dextrin (15 ppm w/w), and Tocopherol (10 ppm w/w).

2.2. Dermatological Clinical Efficacy Study

This clinical efficacy study was a longitudinal, open-label, monadic, home-use, 4-week clinical study investigating the efficacy of the Facial Toner containing 2.0% (w/w) Arbutin and 3.0% (w/w) Niacinamide in volunteers with expert-assessed visible/large pores and self-declared uneven skin texture. This study was sponsored by Good Molecules, LLC, USA, and conducted in the United States of America by a contract research organization (Validated Claim Support, LLC, USA) between October and November 2023. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board Allendale Investigational Review Board, Inc. (IRB Study Number: CS231034). All volunteers signed a written informed consent before initiating the study. Volunteers willing to be photographed signed a model release agreement consenting to use of their images.

Volunteers were included if they were of legal age, healthy, had expert-assessed visible/large pores (score of > 3 on a 10-point scale at baseline), and had self-declared uneven skin texture, and were willing to comply with the procedures, methods, evaluations, and study product usage described in the informed consent document. Volunteers were excluded if they were historically allergic to facial products; pregnant or breast-feeding; immunocompromised; presented observable pre-existing facial skin disease or condition; a history of severe or chronic diseases and conditions such as cancer, AIDS, insulin-dependent diabetes, renal impairment, mental illness, and/or drug/alcohol addiction; a history of melanoma, or treated skin cancer within the last five years; a history of taking hormones within the previous three months; a history of use of oral contraception for less than three months before the study or who have changed their contraceptive method within three months before the study; have regular salon and/or dermatological procedures (microdermabrasion, fillers, facial peels, etc.) and are not willing to stop throughout the study; and if they were currently participating in other clinical trials involving testing a facial product.

After screening and recruitment, thirty-one healthy adult volunteers completed the study. They underwent an approximate five-day washout period in which they discontinued skincare products. Then, they were instructed to apply one dropper (1 mL) of the Facial Toner onto a cotton pad and gently sweep over clean skin twice daily, in the morning and at night, for four weeks. The Facial Toner was not washed off since toners are designed to be left on the skin to be absorbed before applying the rest of the skincare routine, such as serums, creams, and sunscreen. Volunteers were also required to apply the supplied SPF 30 during the daytime. The instructions were explained and provided to all volunteers verbally and in writing, along with a daily product log to record use to ensure compliance during home use. Daily logs were reviewed in week four, and test material containers were weighed to verify protocol compliance with product use instructions.

Variations in the appearance of pores (Pore Appearance), skin brightness (Radiance/Luminosity), and uneven skin texture (Skin Texture/Smoothness) were followed up and evaluated objectively by trained expert grading at baseline (week zero) and week four utilizing a 10-point ordinal scale (

Table 1), overhead lighting, and a lighted magnifying loop as needed.

Digital photographs at baseline and week four also helped to subjectively determine variations in the appearance of pores, skin brightness, and uneven skin texture. Photographs were not retouched. At week four, consumer perception of the product and its effects was determined by analyzing results from a self-perception questionnaire using a 4-point Likert scale.

Facial skin brightness was measured by the Chroma Meter CR-200 (Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan), which converts all colors within the range of human perception into a standard numerical code known as the CIEL*a*b* color space (defined by the International Commission on Illumination, abbreviated CIE in French), allowing quantification of product-induced changes in skin color within these parameters for analysis. The Chroma Meter represents lightness as L* where 0 = black and 100 = white. At the same time, the red-green and yellow-blue color spectra are defined as a* and b*, respectively, where red and yellow are indicated by positive values and green and blue by negative values. All volunteers had Chroma Meter measurements taken in triplicate on the right or left cheek, per randomization, at baseline and week four. With Chroma Meter measurements, the Individual Typology Angle (ITA°) was calculated for each individual per the equation [

15]:

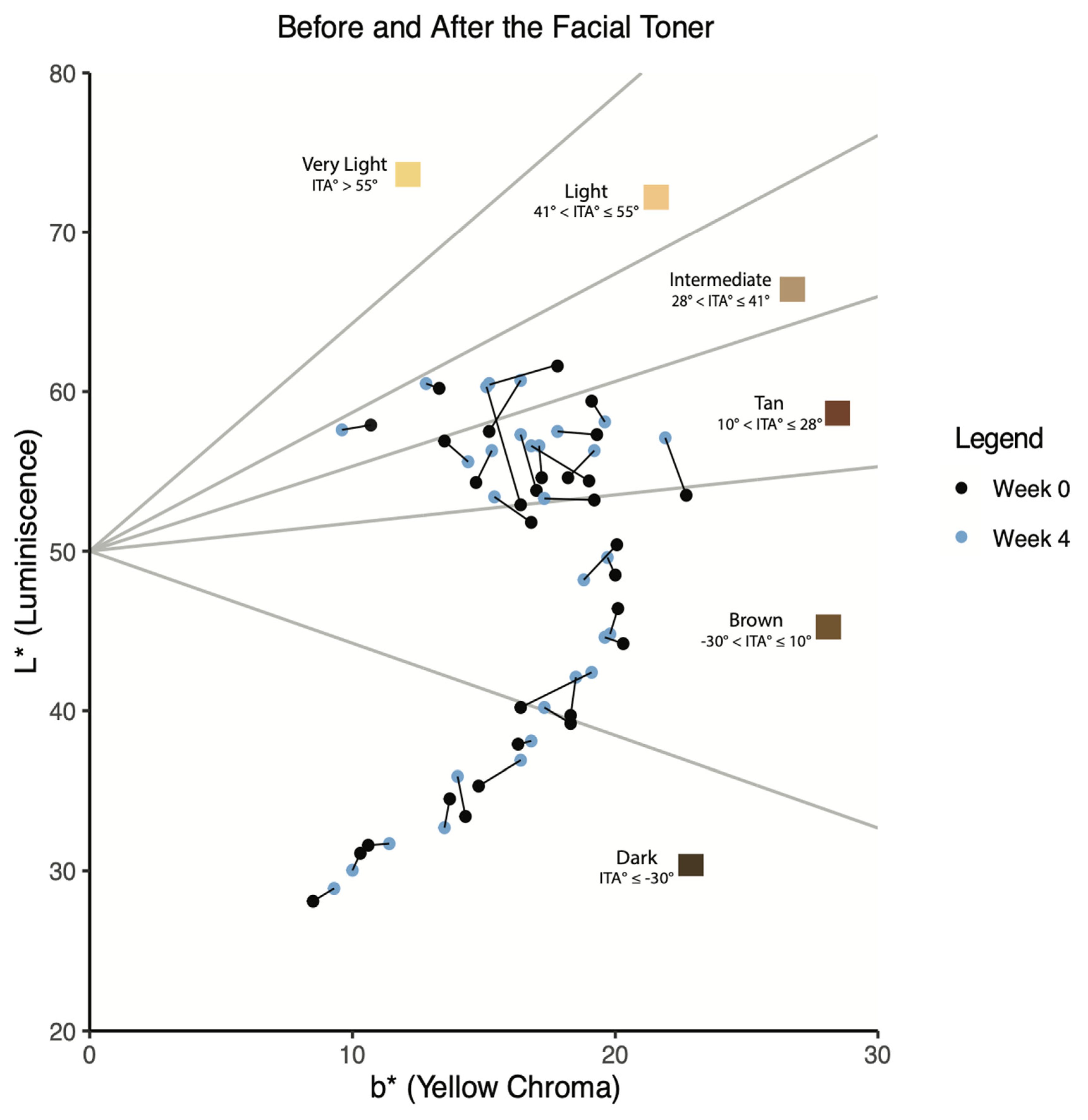

ITA° is an objective classification of skin color into six groups ranging from very light to dark [

16]. The smaller the ITA° value, the darker the skin type. The values of ITA° per skin subtype are as follows: the very light skin subtype is an ITA° > 55°, the light subtype has the range 41° < ITA° ≤ 55°, the intermediate subtype ranges 28° < ITA° ≤ 41°, the tan subtype range is from 10° < ITA° ≤ 28°, the brown subtype has the range -30° < ITA° ≤ 10°, and the dark subtype is an ITA° ≤ -30°. Results on week four were compared to the baseline. An n = 30 volunteers was used for the final Chroma Meter data analysis. One of the volunteers’ Chroma Meter data was removed due to a suspected measurement or data entry error in week four.

2.3. Statistics

Mean, minimum, and maximum statistics are provided for age. Frequency (expressed as number and percent) is provided for ethnicity and race. A paired t-test was used to compare variations from week four to the baseline and determine any significant differences in the instrumental assessments and expert grading. All statistical tests were set to a significance level of 5%. Mean, standard deviation (SD), and mean percent change compared to baseline values and percent of volunteers showing improvement are provided for the week four timepoint. Frequency (expressed as number and percent) and favorable response threshold (≥ 50% agreement amongst volunteers characterizes a favorable response) were used to interpret the subjective questionnaire. R Studio Version: 2024.04.2+764 (Posit, PBC, United States of America) was used for general statistics and paired t-test of the ITA° and L* measurements. The RStudio package ggplot2 was used to generate graphs. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Results

Before initiating the clinical efficacy study, a previous dermatological safety study of the 2% Arbutin and 3% Niacinamide toner formulation was conducted. The results indicated no potential for dermal irritation or sensitization (contact allergy). With these reassuring results, a dermatological clinical efficacy study was carried out with a diverse panel of thirty-one (31) volunteers, comprising 74% Females and 26% Males, aged 18-68 years (Fitzpatrick Skin Types II-VI), with 48% belonging to Caucasian and 42% to Black or African American ethnicities (

Table 2). This diverse representation ensured that the clinical efficacy study’s results apply to various skin types and ethnicities, making our findings applicable to various individuals. At baseline, all volunteers initially presented signs of visible/large pores, uneven skin texture, and a dull complexion.

Previous research on various skincare products containing arbutin or niacinamide have yielded significant findings. For instance, a cream containing 2.51% Arbutin, derived from

Serratulae quinquefoliae, was found to significantly decrease melanin levels in women with melasma and solar lentigines when applied twice daily for eight weeks [

17]. Similarly, a moisturizer with 5% Niacinamide has been clinically shown to reduce melanin levels in hyperpigmentation and signs of aging by improving fine lines, wrinkles, texture, red blotchiness, and skin sallowness after four to eight weeks of treatment [

14,

18].

In our study, after just four weeks of using the Facial Toner, the expert grading showed a statistically significant improvement in the overall appearance of pores (Pore Appearance), skin brightness (Radiance/Luminosity), and uneven skin texture (Skin Texture/Smoothness) (

Table 3). These improvements were quantitatively measured and subjectively observed in digital photographs. The photographs illustrate participants who achieved a reduction in mild redness and blemishes in the cheeks and forehead (

Figure 1a), a decrease in dark spot appearance in the cheek area (

Figure 1b), and a lightening of the area around the lips, including an overall improvement in brightness (

Figure 1c). These results, representing the average results of the thirty-one volunteer study panel, provide tangible evidence of the Facial Toner’s efficacy.

Instrumental Chroma Meter assessment quantitatively measured facial skin lightening using the CIEL*a*b* color system, a widely used method in cosmetic and dermatological research to quantify color and brightness changes. This system, sometimes referred to as colorimetry, measures skin color objectively [

19,

20]. The Chroma Meter represents L* as changes in lightness ranging from black to white, a* as changes in the red-green spectrum, and b* as changes in the yellow-blue spectrum. With the CIEL*a*b* measurements, we calculated each volunteer’s individual typology angle (ITA°) and skin lightness (L*) [

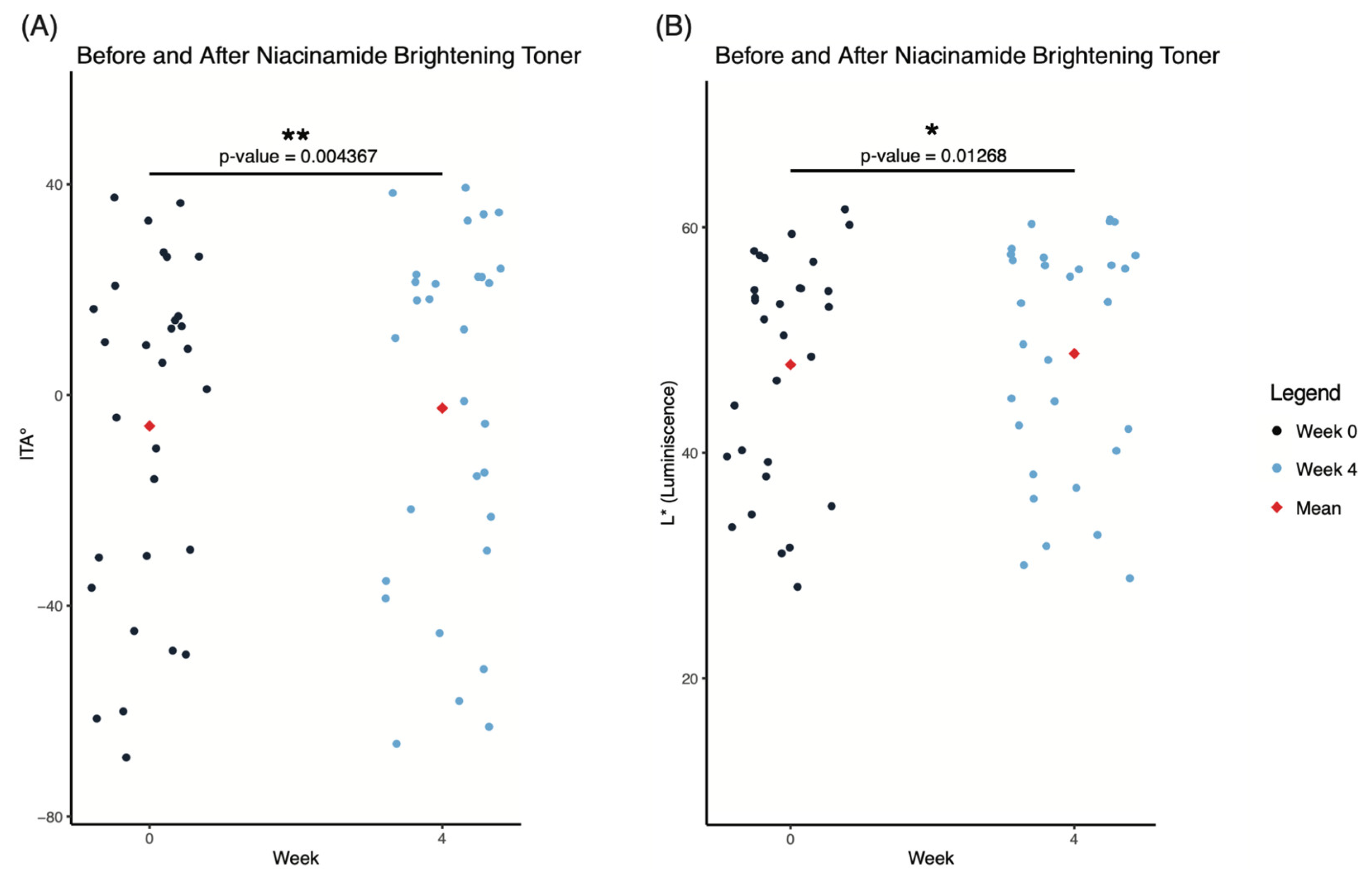

21]. ITA° is an objective classification of skin color to facilitate dermatological and cosmetic research. This classification system allows skin color to be objectively classified into six groups ranging from very light to dark skin instead of using the Fitzpatrick skin type scale that depends on subjective evaluation of hair and eye color along with describing a person’s skin type in terms of response to ultraviolet radiation exposure. ITA° skin subtypes range from very light to dark; the smaller the ITA° value, the darker the skin type. Daily use of the Facial Toner containing arbutin and niacinamide for four weeks significantly increased ITA° values (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3a). These results indicate that the volunteers’ skin tone became lighter after four weeks of using the Facial Toner compared to their baseline skin tone measurement. Strikingly, a few volunteers had a change in skin color subtype. Two out of 11 (18%) individuals from the Tan subtype changed to the Intermediate subtype, three out of eight (38%) individuals from the Brown subtype changed to the Tan subtype, and two out of eight (25%) individuals in the Dark subtype changed to the Brown subtype. Contrastingly, in the Intermediate subtype, two out of three individuals (67%) had an increase in their ITA° but did not change their skin subtype. A similar decrease pattern was seen in two out of 11 (18%) individuals in the Tan subtype, two out of eight (25%) Brown subtype individuals, and two out of eight (25%) individuals belonging to the Dark subtype. Additionally, there was a significant increase in luminescence (L*) when comparing baseline measurements with the end of the study (week 4) (

Figure 3b), meaning that facial skin brightness improved in 73% of volunteers. Overall, CIEL*a*b* measurement results suggest that the Facial Toner enhances skin tone, lightness, and brightness.

Subjective efficacy and consumer satisfaction with the Facial Toner reinforce the previous observations in this study. After four weeks of using the toner, volunteers noticed satisfactory improvements in smoothness, softness, and tightness of the skin and a more refined skin texture (

Table 4: statements 1, 5, 6, 14). Moreover, they also noticed that their skin looked more radiant, brighter, less dull, and youthful overall, with a more even skin tone (

Table 4: statements 2, 3, 10, 11). Notably, all volunteers agreed or strongly agreed that they would recommend the Facial Toner to a friend and even purchase it themselves (

Table 4: statements 7-8). This high level of consumer satisfaction was measured using a Likert scale, where volunteers were asked to rate their agreement with each statement on a scale of 1 to 4, with 1 being strongly disagree and 4 being strongly agree.

Discussion

Our Facial Toner, containing 2% Arbutin and 3% Niacinamide, delivered noticeable results in various skin types and ethnicities in just four weeks, making our findings inclusive and applicable to a wide range of individuals. It objectively improved the volunteers’ overall skin brightness, as confirmed by expert grading and Chroma Meter measurements compared to baseline skin tone measurements. Furthermore, the volunteers also saw a significant change in their skin’s appearance, noticing a more radiant, brighter, less dull, and more youthful overall appearance with a more even skin tone. All thirty-one volunteers completed the study without any adverse events or skin reactions, further affirming the safety and effectiveness of the Facial Toner formulation and instilling confidence in its use.

While our study has provided valuable insights, it’s important to note its limitations. For instance, there was no placebo control group, and the results need to be confirmed with a larger sample size in a double-blind controlled trial. Moreover, since our Facial Toner contains both Arbutin and Niacinamide, and there was no control group isolating each ingredient, we cannot determine how much of the observed effect is attributed to each ingredient. Lastly, comparisons with toners containing other bioactives were not considered. These factors underscore the need for further research and the potential for even more significant findings in the future, highlighting the importance of your role in advancing the field.

Conclusion

The Facial Toner was well-tolerated, with no adverse events or skin reactions, indicating no potential for producing contact allergy. After four weeks, daily use of the Facial Toner improved the skin’s overall facial tone and appearance of pores, brightness, and uneven skin texture in diverse skin types and ethnicities. Whether objectively or subjectively, the study showed that the Facial Toner is safe and effective, leading to excellent consumer acceptability. In summary, a topical formulation containing 2% Arbutin and 3% Niacinamide has proven to be a significant game-changer in the skincare industry, leaving users with a brighter and more youthful complexion. More than just a cosmetic improvement, this Facial Toner also aims to address psychosocial components by providing a more youthful appearance to the user’s skin, likely leading to increased self-esteem and improved social relations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.D.S.S.; methodology, I.D.S.S.; software, A.M.M.L.; validation, A.M.M.L. and I.D.S.S.; formal analysis, A.M.M.L.; data curation, I.D.S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.M.L.; writing—review and editing, A.M.M.L. and I.D.S.S.; visualization, A.M.M.L.; supervision, I.D.S.S.; project administration, I.D.S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board Allendale Investigational Review Board, Inc. (IRB Study Number: CS231034). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all volunteers for their participation in the study. We also thank the team at Validated Claim Support for their assistance with the study management, in particular Jane Tervooren, Brian Ecclefield, Anna Hardy, James VanZetta, Alex Widovic, Chrystal Planeta, Pamery Valentina Arredondo, Dana Mastrolia, and Sarah Rahme.

Conflict of Interest

The study was fully sponsored by Good Molecules, LLC, a skincare brand. Both authors are employees of Good Molecules, LLC.

References

- Kligman, A. M.; Koblenzer, C. Demographics and Psychological Implications for the Aging Population. Dermatol. Clin. 1997, 15, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samson, N.; Fink, B.; Matts, P. J. Visible Skin Condition and Perception of Human Facial Appearance. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2010, 32, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derogatis, L. R.; Spencer, P. M. Administration and Procedures: BSI Manual I. Baltim. Clin. Psychom. Res. 1982, 28–51. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M. A.; Schork, N. J.; Ellis, C. N. Psychosocial Correlates of the Treatment of Photodamaged Skin with Topical Retinoic Acid: A Prospective Controlled Study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1994, 30, 969–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, L. Skin Ageing and Its Treatment. J. Pathol. 2007, 211, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Hearing, V. J. Physiological Factors That Regulate Skin Pigmentation. BioFactors 2009, 35, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- França, K.; Keri, J. Psychosocial Impact of Acne and Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2017, 92, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nautiyal, A.; Wairkar, S. Management of Hyperpigmentation: Current Treatments and Emerging Therapies. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2021, 34, 1000–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolery-Lloyd, H.; Kammer, J. N. Treatment of Hyperpigmentation. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2011, 30, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boo, Y. C. Arbutin as a Skin Depigmenting Agent with Antimelanogenic and Antioxidant Properties. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS). Opinion on the Safety of Alpha- (CAS No. 84380-018, EC No. 617-561-8) and Beta-Arbutin (CAS No. 497-76- 7, EC No. 207-8503) in Cosmetic Products, Preliminary Version of 15–16 March 2022, Final Version of 31 January 2023, SCCS/1642/22. 2023. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/publications/safety-alpha-arbutin-and-beta-arbutin-cosmetic-products_en.

- Inoue, Y.; Hasegawa, S.; Yamada, T.; Date, Y.; Mizutani, H.; Nakata, S.; Matsunaga, K.; Akamatsu, H. Analysis of the Effects of Hydroquinone and Arbutin on the Differentiation of Melanocytes. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 36, 1722–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boo, Y. C. Mechanistic Basis and Clinical Evidence for the Applications of Nicotinamide (Niacinamide) to Control Skin Aging and Pigmentation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissett, D. L.; Miyamoto, K.; Sun, P.; Li, J.; Berge, C. A. Topical Niacinamide Reduces Yellowing, Wrinkling, Red Blotchiness, and Hyperpigmented Spots in Aging Facial Skin. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2004, 26, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Bino, S.; Bernerd, F. Variations in Skin Colour and the Biological Consequences of Ultraviolet Radiation Exposure. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 169, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Akimoto, M. Utilization of Individual Typology Angle (ITA) and Hue Angle in the Measurement of Skin Color on Images. Bioimaging Society 2020. [CrossRef]

- Morag, M.; Nawrot, J.; Siatkowski, I.; Adamski, Z.; Fedorowicz, T.; Dawid-Pac, R.; Urbanska, M.; Nowak, G. A Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Randomized Trial of Serratulae Quinquefoliae Folium, a New Source of β -arbutin, in Selected Skin Hyperpigmentations. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2015, 14, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissett, D. L.; Oblong, J. E.; Berge, C. A. Niacinamide: A B Vitamin That Improves Aging Facial Skin Appearance. Dermatol. Surg. 2005, 31, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnapriya, K. S.; Pangelinan, G.; King, M. C.; Bowyer, K. W. Analysis of Manual and Automated Skin Tone Assignments. In 2022 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision Workshops (WACVW); IEEE: Waikoloa, HI, USA, 2022; pp. 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, B. C. K.; Dyer, E. B.; Feig, J. L.; Chien, A. L.; Del Bino, S. Research Techniques Made Simple: Cutaneous Colorimetry: A Reliable Technique for Objective Skin Color Measurement. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2020, 140, 3–12e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E. J.; Ryu, J. H.; Baek, J. H.; Boo, Y. C. Skin Color Analysis of Various Body Parts (Forearm, Upper Arm, Elbow, Knee, and Shin) and Changes with Age in 53 Korean Women, Considering Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).