1. Introduction

Under normal physiological conditions, pigmentation has a beneficial effect on the photoprotection of human skin from harmful UV damage [

1]. However, increased pigmentation, especially on the face, as seen in melasma, solar lentigo (age spots), lentigo simplex (freckles), or because of skin inflammation, chronic heat exposure, hormonal imbalance, mechanical stimulation, medical applications, or other skin and systemic diseases [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7], is a significant cosmetic concern that can cause considerable distress to the affected individuals [

8]. These pigmentation disorders typically occur between the ages of 20 to 40, and are particularly common in women of Asian origin, where they may appear more severe and at an earlier age [

9,

10]. Hyperpigmentation is a more significant indicator of aging than wrinkles, raising substantial quality of life concerns [

11,

12]. Although not considered as a harmful or lethal disorder, severe facial hyperpigmentation, marked by dark spots due to ageing, sun exposure, pregnancy or genetic factor, may lead to decreased self-esteem in women [

13], based in hopes for improving social acceptance and economic opportunity [

14]. While beauty standards have evolved, youthful appearance remains a key element of facial attractiveness: people who are perceived as attractive are considered more successful both professionally and personally, and beauty is associated with well-being [

15,

16]. Thus, clear, evenly toned skin is a widely desired beauty standard worldwide, even among the young generation.

Skin pigmentation and coloration are regulated by the biological processes involving the production of melanin by melanocytes across various layers of the skin [

17]. Thus, alterations in melanocyte production or melanin distribution, due to the internal and/or external factors that interfere with the melanogenesis [

18], ultimately lead to increased melanocyte activation, melanosome development, melanin production, and melanin transfer to surrounding keratinocytes. This process subsequentially results in the formation of dark spots [

17,

19,

20], and the onset of skin hyperpigmentation disorders [

21], characterized by skin darkening and various pigment irregularities such as solar lentigines [

22] and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation [

23].

Due to the complex and not fully understood etiology of hyperpigmentation, its treatment has been explored through multiple approaches, including photoprotection, topical treatments, systemic medications and procedural interventions such as chemical peels with glycolic acid, salicylic acid or Jessner’s solution, as well as laser-based therapies [

24]. Limiting sun exposure and applying sun protection regularly remain the primary approach to reduce the formation and appearance of hyperpigmentation [

24].

Indeed, topical treatments represent the first-line treatment for hyperpigmentation. They are based on skin lightening agents, such as hydroquinone (HQ), that has a long history of use and acts by inhibiting tyrosinase, a copper oxidase containing metalloenzyme, which is the most important rate-limiting enzyme of the melanogenesis pathway [

17]; retinoids, that achieve a lightening effect by modulating cell proliferation and through anti-inflammatory properties [

19,

25]; azelaic acid, a tyrosinase inhibitor that also exerts a selective cytotoxic and antiproliferative effect on melanocytes, ultimately decreasing melanogenesis [

26]; and kojic acid, that acts mainly by inhibiting the cathecolase activity of tyrosinase [

17,

27]. More recently, agents such as topical tranexamic acid [

28,

29], and 5% cysteamine cream [

30] have also been proven to be effective alternatives to conventional topical agents.

Plant-based and natural remedies have long been used to treat skin issues [

31] and are gaining popularity as a secure and efficient method to treat skin hyperpigmentation [

17,

32,

33,

34,

35], targeting various mechanisms to inhibit melanogenesis. Aloesin, a glycoprotein extracted from aloe vera [

17], hesperidin, a flavonoid extracted from various citrus fruits [

36],ellagic acid [

37], licorice extracts [

33] are among the ingredients that, beyond their shared anti-tyrosinase activity, have shown additional biological activities that support the skin lightening [

17]. However, these topical substances may lead to side effects such as skin dryness, irritation, peeling, or hypopigmentation [

17]. In addition, the prolonged treatment duration, ranging from several months to years, may affect patient compliance and overall satisfaction.

Oral medications are considered as second-line treatments for hyperpigmentation [

17]. Although generally more potent than topical treatments and without the need of frequent application and disposal of topical creams, they are more expensive and cause more significant side effects [

38]. Therefore, there is a continuous search for tolerable treatments, with reduced adverse effects like skin irritation and allergic reactions [

39,

40], that could achieve a better treatment compliance thanks to a systemic administration like food supplements/cosmeceuticals [

41,

42] and resulting effective in reducing hyperpigmentation [

43]. Belight

3TM, a food supplement containing a blend of natural botanical extracts, such as grape seed extract, grape pomace extract, licorice root extract, has been shown as effective in brightening the color of facial skin and dark spots in an adult Asian population [

43]. Belight

3TM has shown an in vitro tyrosinase inhibitory activity which derives from a significant interaction between the three botanical extracts contained, thus, adding further evidence that an oral administration of selected ingredients with an anti-tyrosinase activity could safely manage hyperpigmentation.

The aim of the present study was to verify the efficacy of a Belight3TM treatment in lightening dark spots in a Caucasian population with a Fitzpatrick skin types I to III, that - being characterized by a lighter skin pigmentation - exhibit a higher visibility of dark spots. Furthermore, the study investigated whether the lightening effect induced a sensitivity to UV exposure in this population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This randomized, multicentric, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial took place from November 2023 to May 2024 at Complife Italia Srl, laboratories of San Martino Siccomario (PV) and Biella (BI), Italy. Study protocol and Informed Consent Form (ICF) were reviewed by “Comitato Etico Indipendente per le Indagini Cliniche Non Farmacologiche”, Genova (Italy), and approved on November 10th, 2022 (Rif. 2022/06). The clinical trial was registered in a public trial registry (ISRCTN34155374). All the study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Ethical Principles for Medical Research involving Human Subjects outlined in the World Medical Association’s (WMA) Helsinki Declaration and its amendments. Participants were fully informed about the nature, purpose, benefits and risks of participation in the study, as well as the experimental procedures. Participants have signed a written ICF prior to participation.

Sixty-six adult female and male, aged between 28 and 52 years old, were enrolled in the study according to the following main inclusion criteria: Caucasian ethnicity with skin phototype from I to III according to the Fitzpatrick’s scale, clinically showing hyperpigmentation on the face (skin spots related to age, sun exposure or post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, with at least one spot with a minimum diameter of 3 mm); subjects that express their commitment not to change the daily routine or the lifestyle, and not to expose themselves to UV rays in intensive way throughout the study, and subjects under effective contraception (oral/not oral therapy).

The trial excluded: subjects under pharmacological treatments considered incompatible with the study requirement, having an acute, chronic or progressive illness, as well as a skin disease or skin condition liable to interfere with the study data or consider hazardous for the subject or incompatible with the study requirements by the dermatologist; subjects accustomed to use tanning bed, consuming food supplement(s) and/or use of topical skincare products that have an influence on skin response to UV rays or dark spots (currently or within the past 4 weeks before the study), subjects taking medication with photosensitizing potential, drugs and/or dietary supplements able to induce skin colouring, use of corticoids either currently or during the month before the study.

2.2. Investigational Products, Blinding and Randomization

Participants were randomly allocated to receive two bottles of 50 hard-shell capsules each containing 300 mg of a proprietary oral formulation of a grape seed extract, a grape pomace extract and a licorice root extract (Belight

3TM, Activ’Inside, France, patent pending WO2022/069416) or 300 mg of maltodextrin (placebo) (

Figure 1).

Belight3TM was standardized in flavanol monomers ≥ 14.0%, glycyrrhizic acid ≥ 1.0% and total viniferins (including ε-viniferin) ≥ 10.0 ppm. Active and placebo capsules matched for colour, shape, size, resulting undistinguishable from each other. Bottles were labelled in accordance with a computer-generated randomization list created by a statistician not taking part in the study and using an appropriate statistical algorithm (Wey’s urn), an urn designed for sequential trial comping m ≥ 2 treatments with equal allocation. The randomization list was stored in a location not accessible neither to the staff in charge of the experimentation nor to the study participants. Participants, investigators and all the study staff remained blinded until the completion of the data analysis.

Subjects were instructed to take one capsule of testing items per day, during breakfast with a glass of water, over a period of 12 weeks. In the event of a missed dose, they were advised to continue the normal dose. Treatments compliance was evaluated by the study staff by counting the numbers of remaining capsules in the bottles at each visit. To standardize the volunteer’s cosmetic habit, each subject was supplied with a base face cream with sun protective factor 30 and without any other cosmetic activity to use during the whole study period instead of the day/night face cream normally used; subjects were instructed not to apply the cream in the morning of the day of the skin parameters measurements. The ingredients list of the cream (INCI-EU) was: AQUA, ETHYLHEXYL METHOXYCINNAMATE, PEG-6 STEARATE, ETHYLHEXYL SALICYLATE, BUTYL METHOXYDIBENZOYL METHANE, METHYLENE BIS-BENZOTRIAZOLYL TETRAMETHYLBUTYLPHENOL (NANO), OCTOCRYLENE, TRIOLEIN, GLYCERYL STEARATE, GLYCOL STEARATE, PEG-32 STEARATE, GLYCERYL DIOLEATE, CETYL PALMITATE, DECYL GLUCOSIDE, XANTHAN GUM, PROPYLENE GLYCOL, HYDROXYETHYL ACRYLATE/SODIUM ACRYLOYLDIMETHYL TAURATE COPOLYMER, POLYISOBUTENE, PEG-7 TRIMETHYLOLPROPANE COCONUT ETHER, DISODIUM EDTA, ETHYLHEXYLGLYCERIN, CAPRYLYL GLYCOL, O-CYMEN-5-OL.

2.3. Study Flow

Subjects attended the medical centre at T-24h to receive full information about the study, sign the ICF and the authorization for photographs, verify inclusion/exclusion criteria, record demographic and medical history, collect the assigned test product, base cream, daily diary and document compliance, tolerance and dietary habits. Blood pressure (BP) and hearth rate (HR) were measured, and subjects were exposed to UVB for the Minimal Erythema Dose (MED) testing.

Subjects returned to the medical centre at T0 for MED determination. Digital pictures and spectrophotometric measurements of skin redness in areas to be further exposed to MED were acquired, and subjects were then exposed to MED. Intensity of facial dark spots was spectrophotometrically measured and facial digital pictures were captured using Visia-CR to evaluate the percentage of skin with dark spots through image analysis using the threshold algorithms on RBX brown Visia-CR pictures (RBX brown filter). Additionally, a clinical evaluation of basal facial skin features (complexion evenness and whitening efficacy) was conducted. Subjects returned to the medical center at T+24h for digital picture acquisition of the MED exposed areas and spectrophotometric measurements of skin redness.

Subjects returned to the medical centre twenty-four hours before the intermediate visit (T42-24h) for UV-exposure to determine the MED, then at T42 for MED exposure and to repeat the measurements taken at T0. At this checkpoint, subject eligibility in terms of diary compilation and treatment compliance was verified, and BP and HR measurements were also carried out. Digital pictures acquisition of the UV exposed area and skin redness measurements of zones exposed to MED were carried out at T42+24h. This protocol scheme was repeated at T84-24h, T84 and T84+24h. At T84, subjects were also asked to fill-in the self-assessment questionnaire. The presence of any adverse reaction (adverse events (AE) and serious adverse events (SAE) and product tolerability were evaluated at each visit.

2.4. Outcome Measures

Clinical and instrumental evaluations were carried out under controlled conditions (Temperature: 20-24 °C, Relative Humidity: 40%-60%), by letting subjects acclimatize for 15–20 min before each visit. For a given subject, experimental procedures, measurements and clinical evaluations were performed at a similar daytime by the same blinded technicians and by the dermatologist to avoid bias due to the natural circadian variations and to the operator.

2.4.1. Color of Facial Dark Spots

The intensity of facial spot pigmentation was measured on a selected dark spot by means of the CM-700D spectrophotometer, that measures the skin colour in the CIELab chromatic space. The CIELab color system represents quantitative relationship of colors on three axes: L* value indicates lightness, and a* and b* are chromaticity coordinates (Ly). On the color space diagram, L* is represented on a vertical axis with values from 0 (black, total darkness) to 100 (absolute white), the a* and b* value indicate, respectively, the red-green and the yellow and blue components of a color. The L*, a*, and b* values can be transcribed to dermatological parameters. The L* value correlates with the level of pigmentation of the skin; the a* value correlates with erythema and the b* value correlates with pigmentation and tanning (Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage (CIE).

L* and b* values are interpolated using a mathematical formula (ITA = Arctg [(L* - 50)/b*] x (180/π) that allows to calculate the ITA° (Individual Typology Angle), the best description of a lightening effect [

44]. A low ITA° value indicates a dark pigmentation, while a high ITA° value indicates a very light pigmentation [

45].

2.4.2. Dark Spot Surface Measurement

At each time point, digital pictures of the face from each subject were acquired by Visia®-CR (Canfield Scientific Inc, CA, USA), that allows an accurate repositioning of the subjects throughout the study and reproduces similar lighting and photographical conditions. The percentage of skin occupied by dark spots (dark spot surface) was measured by the image analysis technique using the thresholding (segmentation) algorithm on RBX Visia pictures. Thresholding works by separating pixels which fall within a desired range of intensity values from those which do not (also known as ‘segmentation’). Dark spot pixel intensity values are a unique subset of the image and thresholding them from the other features in the image allows to show the percentage of skin occupied by spots.

2.4.3. Minimal Erythema Dose (MED)

MED is the lowest dose of ultraviolet B radiation (UVB-R) that, 24h after UV exposure, results in the first perceptible unambiguous erythema with defined borders appearing over most of the field of UV exposure. MED was calculated by applying a progressive series of UV exposures to the subjects’ back within the region between the scapula line and the waist, using a model 601–300 W solar simulator (Solar Light Co., Inc., Philadelphia, PA, USA). Energy dosages were selected according to the skin phototype of the subject [

46]. Digital images of the MED were taken using a digital camera under standard lighting conditions.

2.4.4. Skin Redness (a* Parameter)

Skin redness was measured before and 24 hours after UV exposure in the MED skin area of the subjects’ back using the spectrophotometer/colorimeter CM-700D (Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan). The skin redness parameter was a* in the standardized CIELab chromatic space.

2.4.5. Clinical Evaluation

Clinical evaluation of skin evenness complexion and lightening efficacy was performed on Visia

®-CR pictures by a board-certified dermatologist by assigning a baseline classification and a variation score according to a scoring system (

Table 1).

2.4.6. Self-Assessment Questionnaire

At the end of the study (T84), subjects were asked to express their opinion about the products’ efficacy by answering a questionnaire.

2.5. Statistical analysis

No formal sample size calculation was deemed necessary since previous clinical studies (43) with similar sizes were successful at evaluating the skin lightening and anti-dark-spot effects of a food supplement.

Statistical Analysis was carried out on the Per Protocol Population. An appropriate statistical model (parametric or not parametric) was applied based on data distribution assessed by means of Shapiro-Wilk W test: RM-ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer post hoc test for repeated measures (intra-group statistical analysis) and normally distributed data, Student T-test for paired measures (intra-group statistical analysis) and normally distributed data, Friedman test followed by Tukey-Kramer post hoc test for repeated measures (intra-group statistical analysis) and not normally distributed data, one-way ANOVA for not repeated measures (inter-group statistical analysis) and normally distributed data and Kruskal-Wallis one way ANOVA on ranks for not repeated measures (inter-group statistical analysis) and not normally distributed data.

The statistical software used were NCSS 10 (version 10.0.7 for Windows, NCSS, Kaysville, UT, USA) for statistical analysis and PASS 11 (version 11.0.8, PASS, LLC, Kaysville, UT, USA) for generating the randomization list.

Intragroup (T42 vs. T0; T84 vs T0) or intergroup (e.g., active vs placebo) statistical analysis criterion to reject the null hypothesis (no product effect) is set at p < 0.05. For clinical evaluations, the positive effect is proven if more than 50% of the subjects register an improvement, while for the self-assessment evaluation, an item is confirmed if at least 60% of subjects answer positively.

3. Results

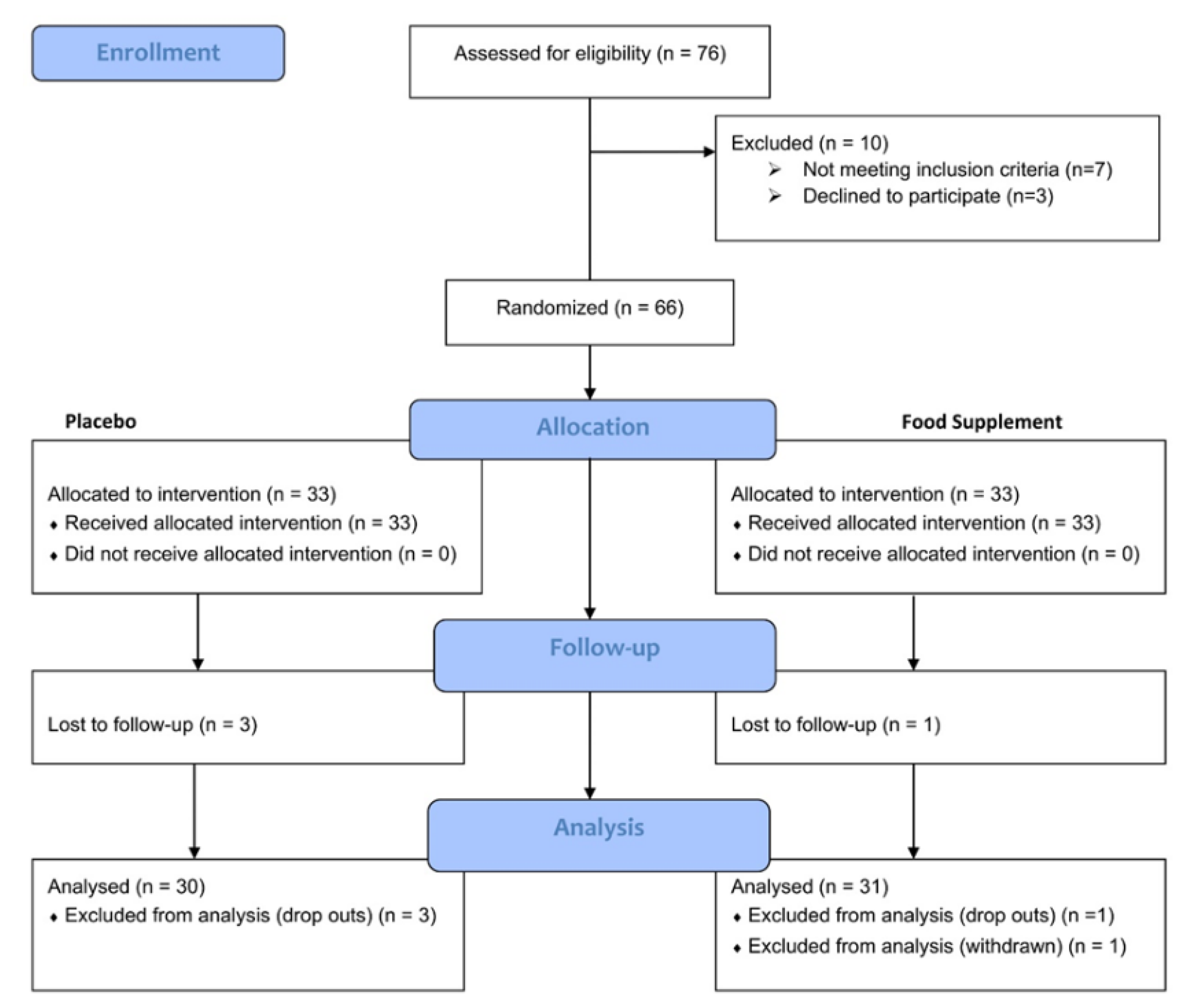

One subject in the active group and three subjects in the placebo group dropped out the study before T42 visit for personal reasons, not related to the study treatment. One subject in the active group was withdrawn due to a major protocol deviation recorded in the treatment regimen (compliance < 90%) (

Figure 1). Therefore, the Per Protocol Population analysis included 61 subjects (n = 30 subjects treated with Placebo and n = 31 subjects treated with Active product).

No relevant variations in the daily dietary habits were highlighted. Furthermore, none of the subjects showed intolerance reactions. All subjects tolerated the test products during the study period; neither AE nor SAE were recorded. Compliance with the allocated treatments was nearly complete (99.6% for the Placebo group and 98.6% for Belight3TM group).

Demographic data, skin phototype, heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure are reported in

Table 2. Vital parameters recorded were in the normal ranges at the beginning and throughout the study and were not significantly different between the two groups.

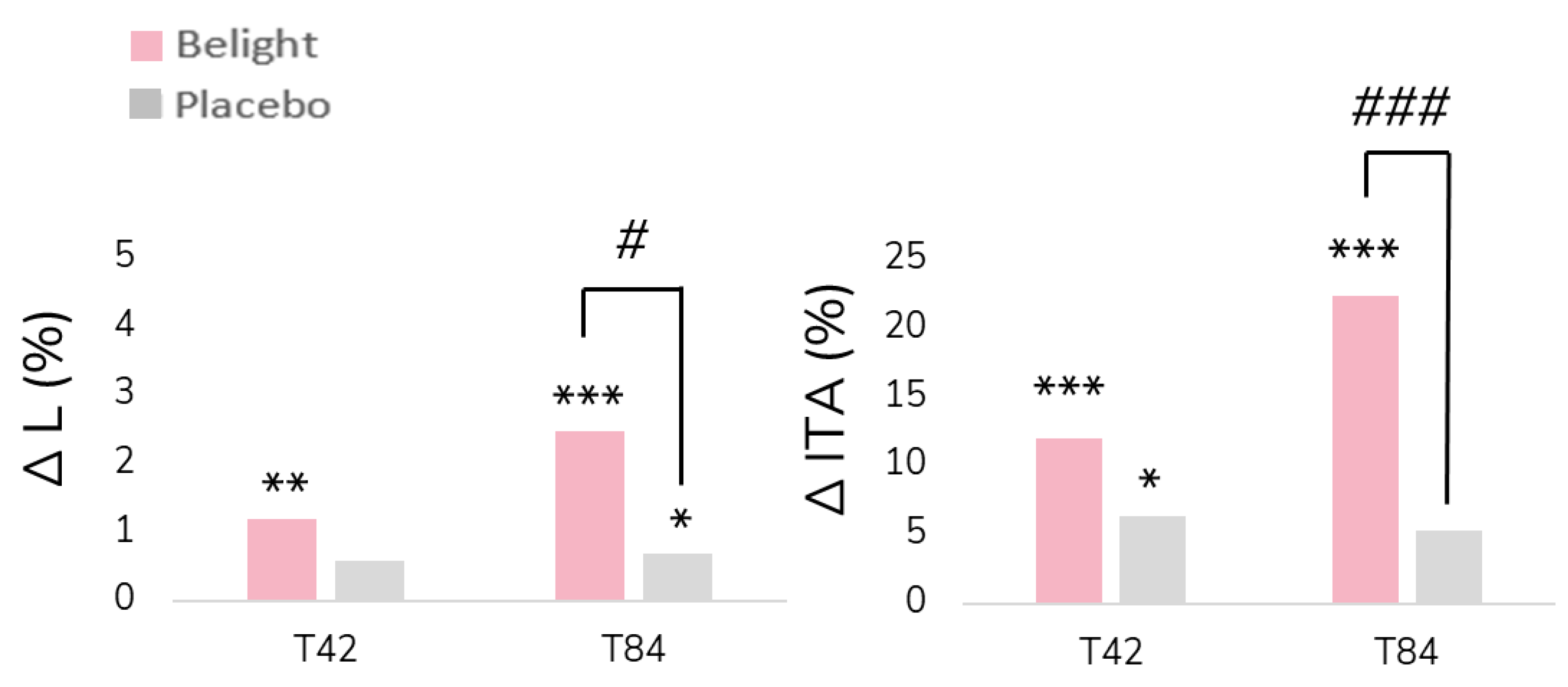

Baseline levels of L* value of the selected dark spot did not show any significant differences between the two groups (

Table 4,

Figure 1). Belight

3TM treatment induced a progressive increase in L* value throughout the study, with an intragroup significative difference achieved at T42 (

p < 0.01) and at T84 (

p < 0.001). Placebo group also induced an increase in L* value, with an intragroup significative difference achieved at T84 (

p < 0.05). However, Belight

3TM treatment resulted in a higher percentage of increase with respect to its baseline value, that resulted in an intergroup significative (

p < 0.05) difference at T84.

Belight

3TM treatment resulted in a progressive and statistically significant intragroup increment of ITA° at T42 and T84 (

p < 0.001 for both), and placebo treatment slightly increased ITA° values throughout the study, with a significant intragroup difference only at T42 (

p < 0.05). This lightening effect resulted in a statistically intergroup difference at T84 (

p < 0.001): 22.4% for Belight

3TM vs 5.3% for placebo (

Table 3,

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean values of Luminance (∆L) and ITA° (∆ITA°) of facial dark spots expressed as % of variation compared to baseline, after 42 days (T42) and after 84 days (T84). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 means significant difference within the group (vs. T0) using RM-ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer post hoc test for repeated measures (intra-group statistical analyses); # p < 0.05, ### p < 0.001 means significant difference between product groups using one-way ANOVA (inter-group statistical analyses).

Figure 1.

Mean values of Luminance (∆L) and ITA° (∆ITA°) of facial dark spots expressed as % of variation compared to baseline, after 42 days (T42) and after 84 days (T84). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 means significant difference within the group (vs. T0) using RM-ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer post hoc test for repeated measures (intra-group statistical analyses); # p < 0.05, ### p < 0.001 means significant difference between product groups using one-way ANOVA (inter-group statistical analyses).

Paired with the L* increase, this data confirms a global reduction of facial hyperpigmentation in the Belight3TM treatment group.

Percentage of skin occupied by dark spots showed an opposite trend according to the treatment: a slight progressive increase of the percentage was observed in the placebo group peaking +3.5% at T84, whereas a slight and progressive decrease of the percentage of skin occupied by dark spots was highlighted in the Belight3TM group, resulting in –1.0% at T84. No statistically significant difference was found either within the groups or between the groups.

Representative photographs of dark spots lightening effect and reduction of percentage of skin surface occupied by dark spot of three subjects administered with Belight

3TM are reported in

Figure 2.

Clinical evaluation of skin complexion evenness and dark spot visibility showed improvement with the Belight

3TM treatment (

Table 4). Starting with a similar baseline score for both groups, placebo treatment led to no changes at T42 and only a slight increment at T84, with 23% of subjects that showed visible improvement; however, this percentage did not reach the threshold for statistical significance. In contrast, the Belight

3TM treatment resulted in a progressively evident improvement in skin complexion evenness throughout the study, with 72% of subjects showing visible improvement at T84, exceeding the 50% threshold. The results for Belight

3TM were statistically significant compared to the placebo (

p < 0.01 at T42 and

p < 0.001 at T84).

Table 4.

Clinical evaluation of skin complexion evenness and dark spot visibility.

Table 4.

Clinical evaluation of skin complexion evenness and dark spot visibility.

| |

Placebo |

Belight3TM

|

| |

T0 |

T42 |

T84 |

T0 |

T42 |

T84 |

Skin Complexion evenness

% subjects with improvement vs T0 |

1.9±0.1 |

1.0±0.1

3% |

1.2±0.1

23% |

1.8±0.1 |

1.4±0.1##

41% |

1.8±0.1###

72% |

Dark spot visibility

% subjects with improvement vs T0 |

--- |

1.0±0.0

3% |

1.2±0.1

17% |

--- |

1.3±0.1

25% |

1.6±0.1###

56% |

Similar results were observed regarding the improvement in dark spots’ visibility: no changes were recorded at T42 and only a slight improvement was observed at T84 in the placebo group. In contrast, the Belight3TM treatment showed a noticeable and progressive improvement throughout the study, resulting in a significant intergroup difference at T84 (p < 0.001), with 56% of subjects showing a visible improvement at T84; exceeding the 50% threshold necessary to support a significant effect.

Clinical and instrumental results were confirmed by the self-evaluation of the volunteers. At the end of the study, the percentage of subjects administered with Belight3TM who perceived the efficacy of the treatment was higher than 60% (confirming statistical significance of the results) and was noticeably higher than the ones administered with placebo: “decrease of dark spots” 64.5% for Belight3TM vs 50.0% for placebo, “improvement of skin complexion evenness” 67.7% for Belight3TM vs 53.3% for placebo, “improvement of skin luminosity” 83.9% for Belight3TM vs 50.0% for placebo (Supplementary table S1).

Baseline MED showed a slight but non-significant difference between the two groups (

Table 5). A slight and progressive decrease in MED was observed in both groups, resulting in a significant intragroup difference in the placebo group at T84 (

p < 0.05), while no significant intragroup difference was observed in the Belight

3TM group. No intergroup differences were recorded.

Skin redness assessed using the a* parameter and measured on the same skin areas that were later exposed to MED, showed no significant difference in the two treatment groups throughout the study (

Table 6). Exposure to MED led to a significant (

p < 0.001) intragroup increase in skin redness in both groups compared to the values measured 24 hours earlier, with no notable differences between the two treatments. The percentage increase in skin redness following MED exposure was almost similar in both groups (greater than 30% throughout the study).

4. Discussion

Various treatment strategies are currently used to alleviate hyperpigmentation [

17,

24], but there remains a need for more effective solutions that avoid dermatological complications that often arise from topical applications, or invasive procedures [

24]. Targeting tyrosinase, a key limiting enzyme in the in vivo synthesis of melanin, represents a promising approach to limit its hyperactivity, which is typically associated with conditions, such as dark spots, melasma and the appearance of melanomas [

39]. Thus, regulation of tyrosinase enzymatic activity through multi-ingredient food supplements could overcome the treatment discontinuity that hamper the efficacy of topical formulations or by oral medications, the undesired side-effects by drugs, and the unpleasant invasive interventions.

The present study showed that the administration of the Belight

3TM, a multi-ingredient food supplement, that combines polyphenol-rich extracts such as standardized stilbenic and high monomeric flavanol grape extract and licorice root extract [

43], resulted effective in progressively lightening facial dark spots in an adult Caucasian population with skin phototypes 1 to 3. Indeed, L* and ITA° levels, measured on selected dark spots, were significantly increased compared to their baseline values throughout the study, as well as compared to the placebo at the end of the treatment. These instrumental data were confirmed by the clinical assessments of skin complexion evenness and dark spot visibility. Both features demonstrated a noticeable and progressive increase of the number of subjects showing clinical improvement in the Belight

3TM group, resulting in a significant difference compared to the placebo.

The lighter skin of Caucasian people did not warrant investigation into the lightening effect on facial skin color, as previously conducted in the Asian population. Nevertheless, Belight3TM treatment was effective in improving skin complexion evenness and reducing the percentage of skin covered by dark spots, thereby indirectly improving the luminosity of the complexion in Caucasian individuals. Both features contribute of the overall beauty of facial skin.

Belight3TM treatment did not change the UV-exposure response: neither the MEDs nor the skin redness measured in areas exposed to MED showed any difference compared to the placebo, indicating that the lightening effect observed on facial dark spots of this Caucasian population was independent of any skin sensitivity to UV. In other words, the lightening effect of Belight3TM did not increase sensitivity to UV exposure in this population, characterized by lighter skin pigmentation and greater visibility of hyperpigmentation, compared to the Asian population. Such consideration could be extended to the Asian population, where variations of skin redness due to UV-B exposure are not easily appreciated.

Therefore, building on the previous clinical study conducted on an Asian population (43), the administration of Belight3TM confirmed its overall lightening effect on dark spots and strengthened the indication that an oral administration of selected mixtures of ingredients, such as this combination of polyphenol-rich extracts from grape seed, grape pomace and licorice root extract, can achieve systemic inhibition of tyrosinase without any side effects. Designed as a confirmatory clinical study, this randomized clinical trial met the expectations set by the prior clinical study and serves as a starting point for addressing hyperpigmentation through multi-ingredients nutricosmetic supplements. This concept allows for a broad range of food supplements by optimizing both the qualitative composition of the formulation and the relative concentration of ingredients to achieve the desired effects.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Self-assessment questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.N. and I.D.P; methodology, V.N.; validation, V.N., F.T. and G.R.; formal analysis, V.N. and I.D.P; investigation, G.R.; resources, V.N.; data curation, V.N., F.T. and I.D.P.; writing—original draft preparation, F.T.; writing—review and editing, V.N.; visualization, L.P., D.G., B.M.; supervision, V.N.; project administration, C.P.; funding acquisition, B.M. and C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Activ’Inside (Beychac & Caillau, Bordeaux, France).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the “Comitato Etico Indipendente per le Indagini Cliniche Non Farmacologiche” (ref. no. 2022/06 on 10/11/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available since they are the property of the sponsor of the study (Activ’Inside, Beychac & Caillau, Bordeaux, France).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Complife Italia staff, who contributed to the study and recruited the subjects, for their professionalism and support during study development.

Conflicts of Interest

The present work was funded by Activ’Inside (Beychac & Caillau, Bordeaux, France). L.P., D.G., B.M. and C.P. are full-time employees of Activ’Inside (Beychac & Caillau, Bordeaux, France). The other authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Brenner, M.; Hearing, V. J. The Protective Role of Melanin against UV Damage in Human Skin. Photochem Photobiol 2008, 84, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubair, R.; Lyons, A. B.; Vellaichamy, G.; Peacock, A.; Hamzavi, I. What’s New in Pigmentary Disorders. Dermatol Clin 2019, 37, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, K. Large Melanosome Complex Is Increased in Keratinocytes of Solar Lentigo. Cosmetics 2017, 4, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plensdorf, S.; Livieratos, M.; Dada, N. Pigmentation Disorders: Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician 2017, 96, 797–804. [Google Scholar]

- Cestari, T. F.; Dantas, L. P.; Boza, J. C. Acquired Hyperpigmentations. An Bras Dermatol 2014, 89, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Hearing, V. J. Melanocytes and Their Diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, G.; Kovacs, D.; Picardo, M. Mechanisms Underlying Post-Inflammatory Hyperpigmentation: Lessons from Solar Lentigo. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2012, 139 Suppl 4, S148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzella, L.; Napolitano, A. Natural Phenol Polymers: Recent Advances in Food and Health Applications. Antioxidants (Basel) 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syder, N. C.; Quarshie, C.; Elbuluk, N. Disorders of Facial Hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Clin 2023, 41, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschachler, E.; Morizot, F. Ethnic Differences in Skin Aging. In Skin Aging; Gilchrest, B. A., Krutmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S. H. The Treatment of Visible Signs of Senescence: The Asian Experience. Br J Dermatol 1990, 122 Suppl 35, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. Y. Melasma and Aspects of Pigmentary Disorders in Asians. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2012, 139 Suppl 4, S144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platsidaki, E.; Efstathiou, V.; Markantoni, V.; Kouris, A.; Kontochristopoulos, G.; Nikolaidou, E.; Rigopoulos, D.; Stratigos, A.; Gregoriou, S. Self-Esteem, Depression, Anxiety and Quality of Life in Patients with Melasma Living in a Sunny Mediterranean Area: Results from a Prospective Cross-Sectional Study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2023, 13, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duperray, J.; Sergheraert, R.; Chalothorn, K.; Tachalerdmanee, P.; Perin, F. The Effects of the Oral Supplementation of L-Cystine Associated with Reduced L-Glutathione-GSH on Human Skin Pigmentation: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Benchmark- and Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J Cosmet Dermatol 2022, 21, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrov, D.; Kroumpouzos, G. Beauty Perception: A Historical and Contemporary Review. Clin Dermatol 2023, 41, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, K.; Ruthruff, E.; Tybur, J. M.; Gaspelin, N.; Miller, G. Perception of Facial Attractiveness Requires Some Attentional Resources: Implications for the “Automaticity” of Psychological Adaptations. Evolution and Human Behavior 2012, 33, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, A.; Wairkar, S. Management of Hyperpigmentation: Current Treatments and Emerging Therapies. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2021, 34, 1000–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Bernal, A.; Muñoz-Pérez, M. A.; Camacho, F. Management of Facial Hyperpigmentation. Am J Clin Dermatol 2000, 1, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E. C.; Callender, V. D. Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation: A Review of the Epidemiology, Clinical Features, and Treatment Options in Skin of Color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2010, 3, 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Makino, E. T.; Kadoya, K.; Sigler, M. L.; Hino, P. D.; Mehta, R. C. Development and Clinical Assessment of a Comprehensive Product for Pigmentation Control in Multiple Ethnic Populations. J Drugs Dermatol 2016, 15, 1562–1570. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. M.; Perez, M. I. Treatment of Hyperpigmentation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2011, 19, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarcella, G.; Gerber, P. A.; Edge, D.; Nielsen, M. C. E. Effective Removal of Solar Lentigines by Combination of Pre- And Post-Fluorescent Light Energy Treatment with Picosecond Laser Treatment. Clin Case Rep 2020, 8, 1429–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenoy, A.; Madan, R. Post-Inflammatory Hyperpigmentation: A Review of Treatment Strategies. J Drugs Dermatol 2020, 19, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moolla, S.; Miller-Monthrope, Y. Dermatology: How to Manage Facial Hyperpigmentation in Skin of Colour. Drugs Context 2022, 11, 2021–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riahi, R. R.; Bush, A. E.; Cohen, P. R. Topical Retinoids: Therapeutic Mechanisms in the Treatment of Photodamaged Skin. Am J Clin Dermatol 2016, 17, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q. H.; Bui, T. P. Azelaic Acid: Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Properties and Its Therapeutic Role in Hyperpigmentary Disorders and Acne. Int J Dermatol 1995, 34, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolghadri, S.; Bahrami, A.; Hassan Khan, M. T.; Munoz-Munoz, J.; Garcia-Molina, F.; Garcia-Canovas, F.; Saboury, A. A. A Comprehensive Review on Tyrosinase Inhibitors. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2019, 34, 279–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banihashemi, M.; Zabolinejad, N.; Jaafari, M. R.; Salehi, M.; Jabari, A. Comparison of Therapeutic Effects of Liposomal Tranexamic Acid and Conventional Hydroquinone on Melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol 2015, 14, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, B.; Naeini, F. F. Topical Tranexamic Acid as a Promising Treatment for Melasma. J Res Med Sci 2014, 19, 753–757. [Google Scholar]

- Karrabi, M.; David, J.; Sahebkar, M. Clinical Evaluation of Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of Cysteamine 5% Cream in Comparison with Modified Kligman’s Formula in Subjects with Epidermal Melasma: A Randomized, Double-Blind Clinical Trial Study. Skin Res Technol 2021, 27, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, A.; Govindaraj, S. Study of Plant-Based Cosmeceuticals and Skin Care. South African Journal of Botany 2023, 158, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanlayavattanakul, M.; Lourith, N. Plants and Natural Products for the Treatment of Skin Hyperpigmentation - A Review. Planta Med 2018, 84, 988–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollinger, J. C.; Angra, K.; Halder, R. M. Are Natural Ingredients Effective in the Management of Hyperpigmentation? A Systematic Review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2018, 11, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Panzella, L.; Napolitano, A. Natural and Bioinspired Phenolic Compounds as Tyrosinase Inhibitors for the Treatment of Skin Hyperpigmentation: Recent Advances. Cosmetics 2019, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, P.; Bhawan, J.; Howell, M.; Desai, S.; Coryell, E.; Einziger, M.; Simpson, A.; Yaroshinsky, A.; McCraw, T. Histopathological Changes Induced by Malassezin: A Novel Natural Microbiome Indole for Treatment of Facial Hyperpigmentation. J Drugs Dermatol 2022, 21, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Gao, J. The Use of Botanical Extracts as Topical Skin-Lightening Agents for the Improvement of Skin Pigmentation Disorders. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 2008, 13, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertam, I.; Mutlu, B.; Unal, I.; Alper, S.; Kivçak, B.; Ozer, O. Efficiency of Ellagic Acid and Arbutin in Melasma: A Randomized, Prospective, Open-Label Study. J Dermatol 2008, 35, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, H. R.; Lee, S.; Wong, C.; Pandya, A. G.; Rodrigues, M. Oral Tranexamic Acid for the Treatment of Melasma: A Review. Dermatol Surg 2018, 44, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillaiyar, T.; Manickam, M.; Namasivayam, V. Skin Whitening Agents: Medicinal Chemistry Perspective of Tyrosinase Inhibitors. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2017, 32, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhasz, M. L. W.; Levin, M. K. The Role of Systemic Treatments for Skin Lightening. J Cosmet Dermatol 2018, 17, 1144–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelnour, A.; Adlam, T.; Potts, G. A. Effects of Plant-Derived Dietary Supplements on Skin Health: A Review. Cureus 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L. K. W.; Lee, K. W. A.; Lee, C. H.; Lam, K. W. P.; Lee, K. F. V.; Wu, R.; Wan, J.; Shivananjappa, S.; Sky, W. T. H.; Choi, H.; Yi, K.-H. Cosmeceuticals in Photoaging: A Review. Skin Res Technol 2024, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouchieu, C.; Pourtau, L.; Gaudout, D.; Gille, I.; Chalothorn, K.; Perin, F. Effect of an Oral Formulation on Skin Lightening: Results from In Vitro Tyrosinase Inhibition to a Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Study in Healthy Asian Participants. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, L.; Piérard, G. E. Skin-Lightening Products Revisited. Int J Cosmet Sci 2003, 25, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, B. C. K.; Dyer, E. B.; Feig, J. L.; Chien, A. L.; Del Bino, S. Research Techniques Made Simple: Cutaneous Colorimetry: A Reliable Technique for Objective Skin Color Measurement. J Invest Dermatol 2020, 140, 3–12e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, C. J.; Chandler, R.; Kloss, J. D.; Benson, A.; Rooney, D.; Munshi, T.; Darlow, S. D.; Perlis, C.; Manne, S. L.; Oslin, D. W. Minimal Erythema Dose (MED) Testing. J Vis Exp 2013, No. 75, e50175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).