Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

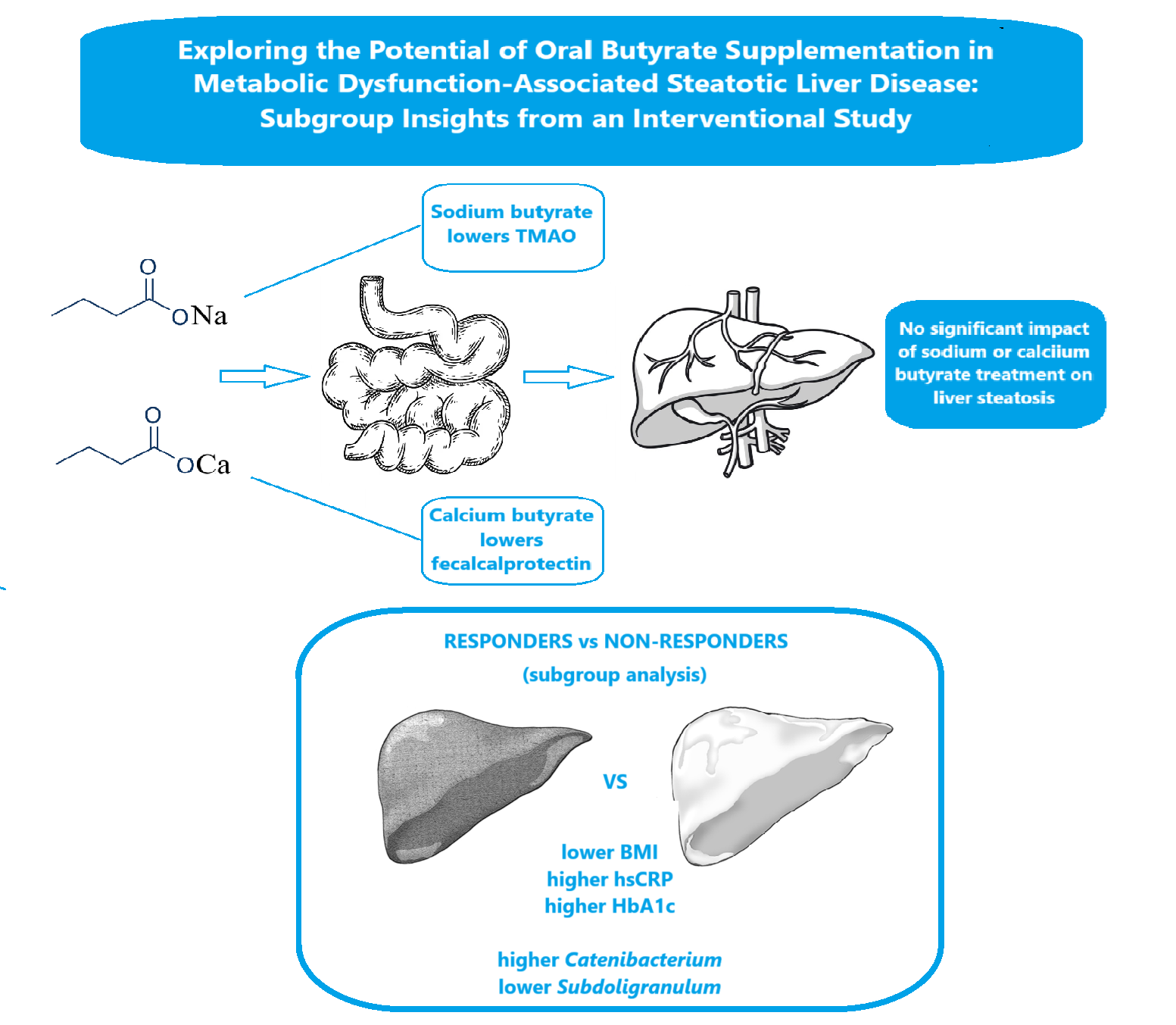

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

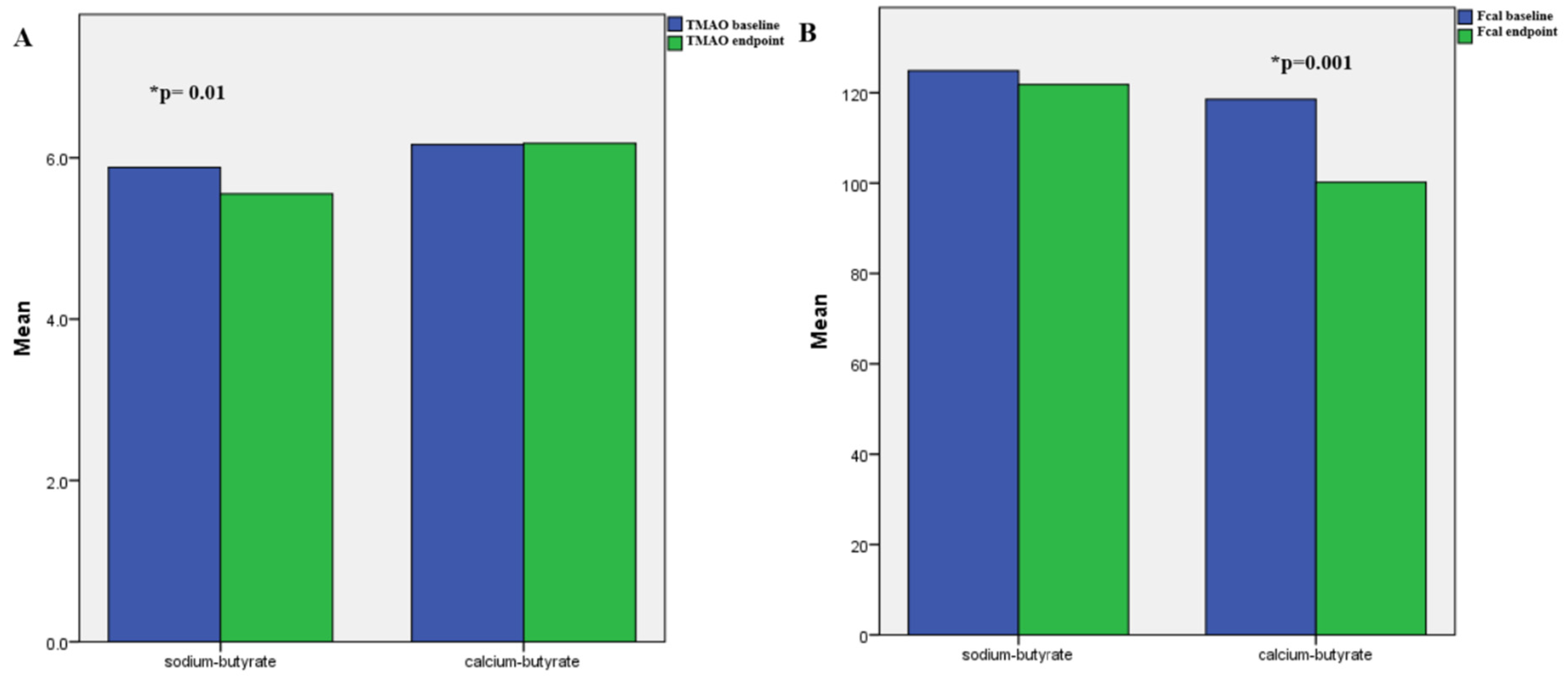

2. Results

| Parameter | Sodium-butyrate | Calcium-butyrate | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 121 | 56 | - |

| Age | 51 ± 15 | 50 ± 16 | 0.68 |

| BMI | 27.8 ± 1.4 | 27.5 ± 1.8 | 0.19 |

| ALT (U/L) | 59 ± 10 | 61 ± 10 | 0.2 |

| AST (U/L) | 56 ± 11 | 57 ± 11 | 0.34 |

| GGT (U/L) | 70 ± 18 | 69 ± 19 | 0.9 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 355 ± 18 | 351 ± 18 | 0.24 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 166 ± 38 | 167 ± 36 | 0.86 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.5 ± 0.5 | 6.6 ± 0.5 | 0.09 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 3.2 (1.1-9.1) | 4 (1.1-9.2) | 0.9 |

| Interleukin 6 (pg/ml) | 42.2 ± 9.2 | 40.7 ± 8.5 | 0.31 |

| CK18F (U/L) | 248 ± 38 | 248 ± 32 | 0.93 |

| TMAO (μmol/L) | 4.3 ± 2 | 4 ± 2.1 | 0.4 |

| Stool SCFA (mmol/L) | 176 ± 36 | 167 ± 36 | 0.13 |

| Fecal Calprotectin (μg/g) | 100 (70-130) | 90 (70-120) | 0.23 |

| Baseline CAP (dB/m) | 290 ± 21 | 289 ± 19 | 0.82 |

| Baseline LSM (kPA) | 4.3 ± 2.4 | 4.9 ± 2.6 | 0.09 |

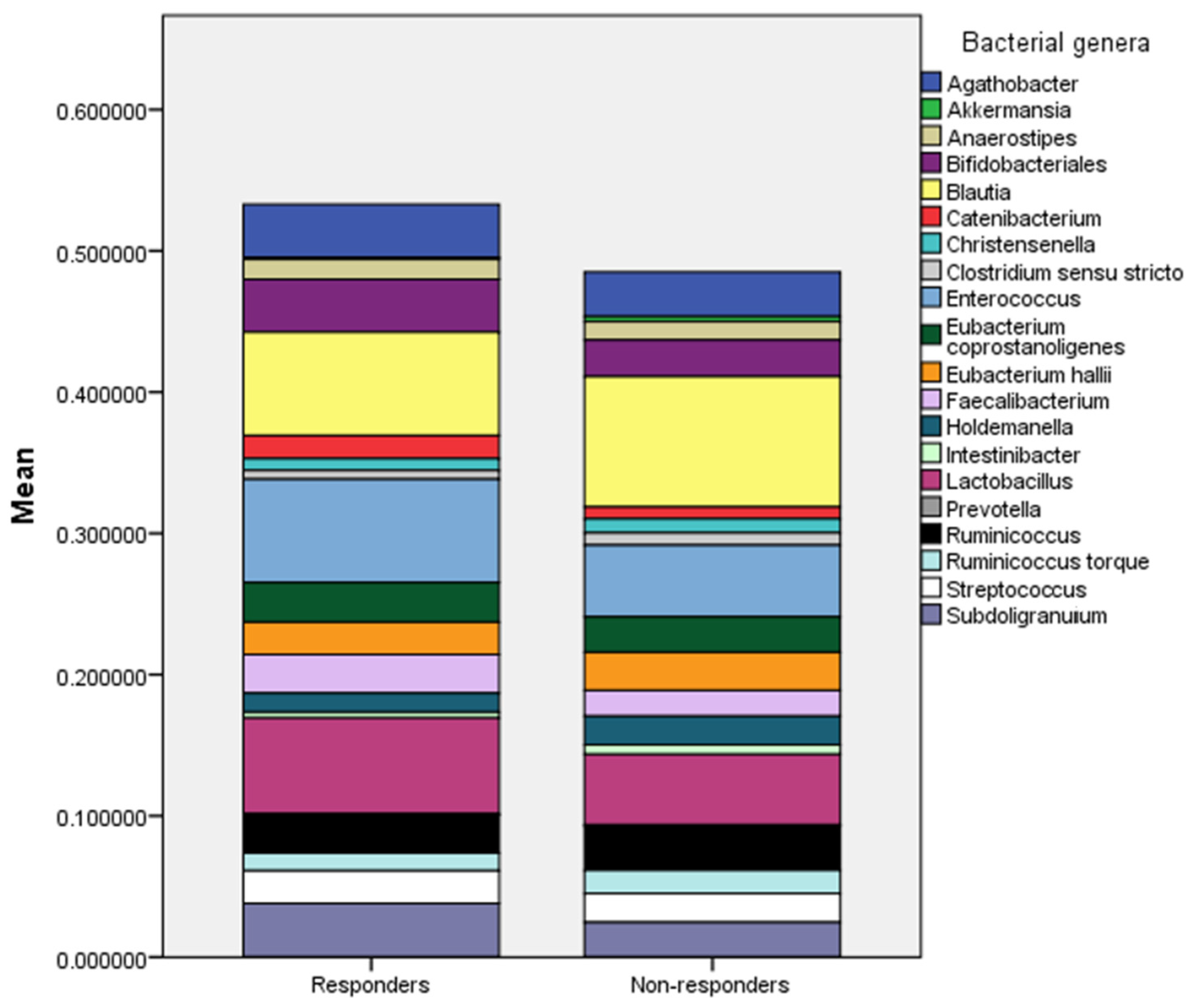

2.1. Insights from a Subgroup Analysis

3. Discussion

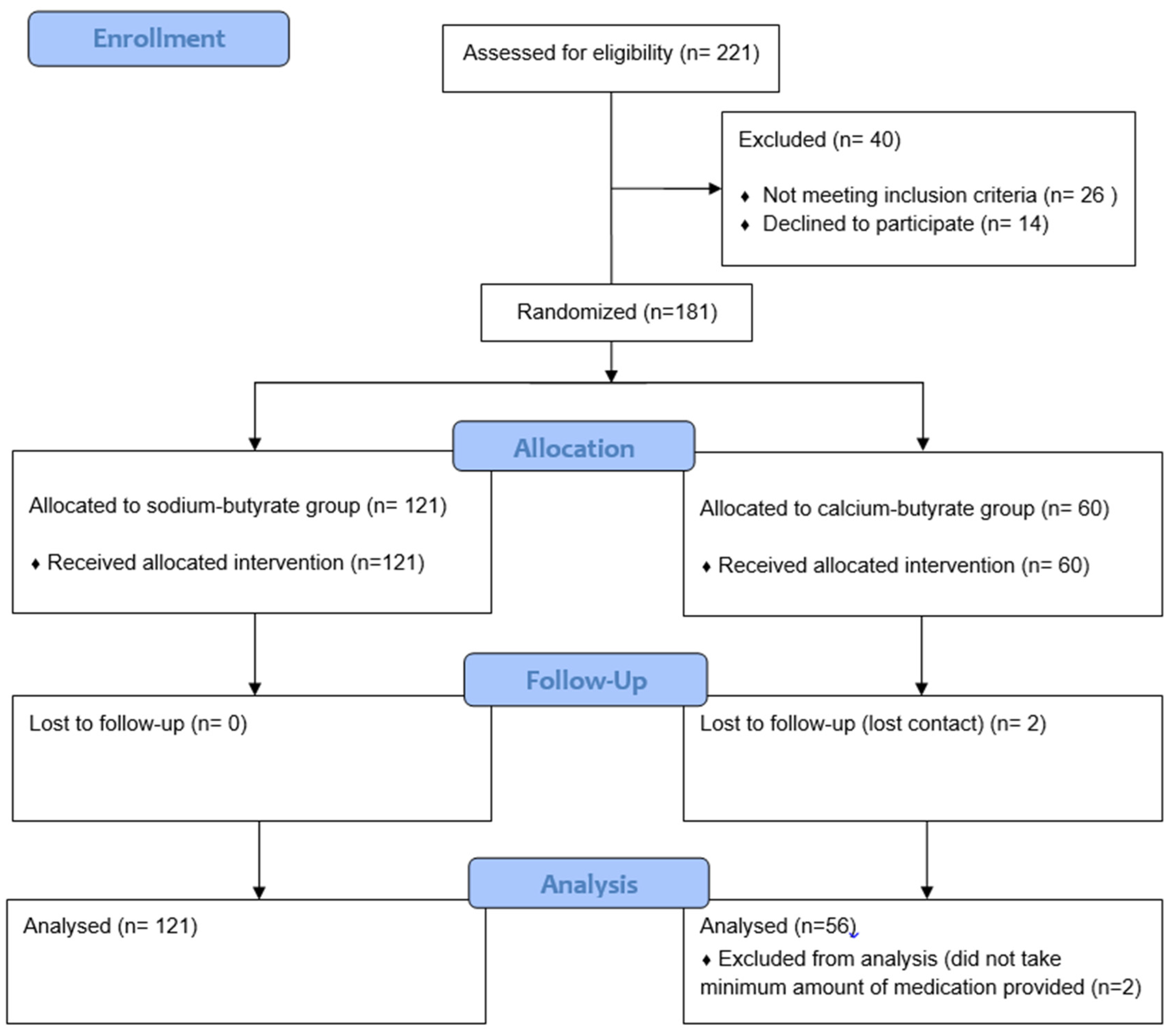

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Intervention

4.2. Assessment

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

Appendix A: Appendix A.1

| Parameter | Sodium-butyrate | Calcium-butyrate | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 121 | 56 | - |

| ALT (U/L) | -0.3 ± 9.7 | -0.2 ± 9.4 | 0.95 |

| AST (U/L) | 0.6 ± 8.6 | 0.8 ± 7.1 | 0.88 |

| GGT (U/L) | -0.3 ± 6.3 | 0.6 ± 6.4 | 0.34 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 0.5 ± 2.1 | 0.8 ± 2.4 | 0.36 |

| Interleukin 6 (pg/ml) | 1.5 ± 9.6 | 0.8 ± 10.8 | 0.68 |

| CK18F (U/L) | 1.3 ± 22.4 | -5.5 ± 22.8 | 0.065 |

| TMAO (μmol/L) | 10 ± 6 | ± 1.3 | 0.001 |

| Fecal Calprotectin (μg/g) | 3 ± 26.6 | 9 ± 31.9 | 0.16 |

| Baseline CAP (dB/m) | 2 ± 11.8 | 0.2 ± 18.1 | 0.42 |

| Baseline LSM (kPA) | -0.09 ± 0.6 | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.22 |

References

- Le, M.H.; Yeo, Y.H.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Zou, B.; Wu, Y.; et al. 2019 Global NAFLD prevalence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022, 20, 2809–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Tilg, H. MASLD: a systemic metabolic disorder with cardiovascular and malignant complications. Gut. 2024, 73, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwärzler, J.; Grabherr, F.; Grander, C.; Adolph, T.E.; Tilg, H. The pathophysiology of MASLD: an immunometabolic perspective. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2024, 20, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Kounatidis, D.; Psallida, S.; Vythoulkas-Biotis, N.; Adamou, A.; Zachariadou, T.; Kargioti, S.; Karampela, I.; Dalamaga, M. NAFLD/MASLD and the Gut-Liver Axis: From Pathogenesis to Treatment Options. Metabolites. 2024, 14, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Hong, J.; Wang, Y.; Pei, M.; Wang, L.; Gong, Z. Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Pathway: A Potential Target for the Treatment of MAFLD. Front Mol Biosci. 2021, 8, 733507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, P.; Arefhosseini, S.; Bakhshimoghaddam, F.; Jamshidi Gurvan, H.; Hosseini, S.A. Mechanistic insights into the pleiotropic effects of butyrate as a potential therapeutic agent on NAFLD management: A systematic review. Front Nutr. 2022, 9, 1037696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fusco, W.; Lorenzo, M.B.; Cintoni, M.; Porcari, S.; Rinninella, E.; Kaitsas, F.; Lener, E.; Mele, M.C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Collado, M.C.; Cammarota, G.; Ianiro, G. Short-Chain Fatty-Acid-Producing Bacteria: Key Components of the Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yan, H.; Ajuwon, K.M. Butyrate modifies intestinal barrier function in IPEC-J2 cells through a selective upregulation of tight junction proteins and activation of the Akt signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0179586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, X.; He, M.; Yi, X.; Lu, X.; Zhu, M.; Xue, M.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, Y. Short-chain fatty acids in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: New prospects for short-chain fatty acids as therapeutic targets. Heliyon. 2024, 10, e26991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Qian, H.; Chao, X.; Williams, J.; Fulte, S.; Li, T.; Yang, L.; Ding, W.X. Autophagy in liver diseases: A review. Mol Aspects Med. 2021, 82, 100973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pant, K.; Yadav, A.K.; Gupta, P.; Islam, R.; Saraya, A.; Venugopal, S.K. Butyrate induces ROS-mediated apoptosis by modulating miR-22/SIRT-1 pathway in hepatic cancer cells. Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fogacci, F.; Giovannini, M.; Di Micoli, V.; Grandi, E.; Borghi, C.; Cicero, A.F.G. Effect of Supplementation of a Butyrate-Based Formula in Individuals with Liver Steatosis and Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutrients. 2024, 16, 2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaworska, K.; Kopacz, W.; Koper, M.; Ufnal, M. Microbiome-Derived Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) as a Multifaceted Biomarker in Cardiovascular Disease: Challenges and Opportunities. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 12511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyileten, C.; Jarosz-Popek, J.; Jakubik, D.; Gasecka, A.; Wolska, M.; Ufnal, M.; Postula, M.; Toma, A.; Lang, I.M.; Siller-Matula, J.M. Plasma Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Is an Independent Predictor of Long-Term Cardiovascular Mortality in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Acute Coronary Syndrome. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021, 8, 728724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferslew, B.C.; Xie, G.; Johnston, C.K.; Su, M.; Stewart, P.W.; Jia, W.; Brouwer, K.L.; Barritt, A.S. , 4th. Altered Bile Acid Metabolome in Patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2015, 60, 3318–28. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Pérez, L.; Gosalbes, M.J.; Yuste, S.; Valls, R.M.; Pedret, A.; Llauradó, E.; Jimenez-Hernandez, N.; Artacho, A.; Pla-Pagà, L.; Companys, J.; Ludwig, I.; Romero, M.P.; Rubió, L.; Solà, R. Gut metagenomic and short chain fatty acids signature in hypertension: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 6436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukic, A.; Bakiri, L.; Wagner, E.F.; Tilg, H.; Adolph, T.E. Calprotectin: from biomarker to biological function. Gut. 2021, 70, 1978–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzel, S.; Jureczek, J.; Kainulainen, V.; Nieminen, A.I.; Suenkel, U.; von Thaler, A.K.; Kaleta, C.; Eschweiler, G.W.; Brockmann, K.; Aho, V.T.E.; Auvinen, P.; Maetzler, W.; Berg, D.; Scheperjans, F. Elevated fecal calprotectin is associated with gut microbial dysbiosis, altered serum markers and clinical outcomes in older individuals. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 13513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozi, D.; Masoumi, S.J.; Mohammad-Kazem Hosseini Asl, S.; Labbe, A.; Razeghian-Jahromi, I.; Fararouei, M.; Lankarani, K.B.; Dara, M. Effects of short-chain fatty acid-butyrate supplementation on expression of circadian-clock genes, sleep quality, and inflammation in patients with active ulcerative colitis: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tougaard, N.H.; Frimodt-Møller, M.; Salmenkari, H.; Stougaard, E.B.; Zawadzki, A.D.; Mattila, I.M.; Hansen, T.W.; Legido-Quigley, C.; Hörkkö, S.; Forsblom, C.; Groop, P.H.; Lehto, M.; Rossing, P. Effects of Butyrate Supplementation on Inflammation and Kidney Parameters in Type 1 Diabetes: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.J.; Barri, A.; Herges, G.; Hahn, J.; Yersin, A.G.; Jourdan, A. In Vitro Dissolution and in Vivo Absorption of Calcium [1-14C]Butyrate in Free or Protected Forms. J of Agri and Food Chem 2012, 60, 3151–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njei, B.; Ameyaw, P.; Al-Ajlouni, Y.; Njei, L.P.; Boateng, S. Diagnosis and Management of Lean Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2024, 16, e71451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.M.; Acevedo, L.A.; Pennings, N. Insulin Resistance. 2023 Aug 17. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

- Steffl, M.; Bohannon, R.W.; Sontakova, L.; Tufano, J.J.; Shiells, K.; Holmerova, I. Relationship between sarcopenia and physical activity in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging. 2017, 12, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, M.; Anand, A.C. Lean Fatty Liver Disease: Through Thick and Thin. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2021, 11, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Kim, S.U.; Song, K.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, D.Y.; Ahn, S.H.; Lee, B.W.; Kang, E.S.; Cha, B.S.; Han, K.H. Sarcopenia is associated with significant liver fibrosis independently of obesity and insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Nationwide surveys (KNHANES 2008-2011). Hepatology. 2016, 63, 776–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crişan, D.; Avram, L.; Morariu-Barb, A.; Grapa, C.; Hirişcau, I.; Crăciun, R.; Donca, V.; Nemeş, A. Sarcopenia in MASLD-Eat to Beat Steatosis, Move to Prove Strength. Nutrients. 2025, 17, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saijo, Y.; Kiyota, N.; Kawasaki, Y.; Miyazaki, Y.; Kashimura, J.; Fukuda, M.; Kishi, R. Relationship between C-reactive protein and visceral adipose tissue in healthy Japanese subjects. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2004, 6, 249–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hul, M.; Le Roy, T.; Prifti, E.; Dao, M.C.; Paquot, A.; Zucker, J.D.; Delzenne, N.M.; Muccioli, G.; Clément, K.; Cani, P.D. From correlation to causality: the case of Subdoligranulum. Gut Microbes. 2020, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Immerseel, F.; Ducatelle, R.; De Vos, M.; Boon, N.; Van De Wiele, T.; Verbeke, K.; Rutgeerts, P.; Sas, B.; Louis, P.; Flint, H.J. Butyric acid-producing anaerobic bacteria as a novel probiotic treatment approach for inflammatory bowel disease. J Med Microbiol. 2010, 59, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, S.; Matamoros, S.; Cani, P.D.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Jamar, F.; Stärkel, P.; Windey, K.; Tremaroli, V.; Bäckhed, F.; Verbeke, K.; de Timary, P.; Delzenne, N.M. Intestinal permeability, gut-bacterial dysbiosis, and behavioral markers of alcohol-dependence severity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014, 111, E4485–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, S.; Tappu, R.M.; Damms-Machado, A.; Huson, D.H.; Bischoff, S.C. Characterization of the Gut Microbial Community of Obese Patients Following a Weight-Loss Intervention Using Whole Metagenome Shotgun Sequencing. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e0149564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Xia, H.; Jie, Z.; Han, X.; Chen, Y.; Ji, L. Effects of Acarbose on the Gut Microbiota of Prediabetic Patients: A Randomized, Double-blind, Controlled Crossover Trial. Diabetes Ther. 2017, 8, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.B.; Chae, S.U.; Jo, S.J.; Jerng, U.M.; Bae, S.K. The Relationship between the Gut Microbiome and Metformin as a Key for Treating Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, G.; Li, S.; Ye, H.; Yang, Y.; Jia, X.; Lin, M.; Chu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, X. Gut microbiome and frailty: insight from genetic correlation and mendelian randomization. Gut Microbes. 2023, 15, 2282795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Matute, P.; Íñiguez, M.; Villanueva-Millán, M.J.; Oteo, J.A. Chapter 32—The oral, genital and gut microbiome in HIV infection. Microbiome metabolome diagnosis 307–323 (Academic Press, 2019).

- Borges, N.A.; Mafra, D. (2018). The Gut Microbiome in Chronic Kidney Disease. Microbiome and Metabolome in Diagnosis, Therapy, and Other Strategic Applications, 349-356.

- da Silva, L.C.M.; de Oliveira, J.T.; Tochetto, S.; de Oliveira, C.P.M.S.; Sigrist, R.; Chammas, M.C. Ultrasound elastography in patients with fatty liver disease. Radiol Bras. 2020, 53, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ruggeri, S.; Buonocore, P.; Amoriello, T. New Validated Short Questionnaire for the Evaluation of the Adherence of Mediterranean Diet and Nutritional Sustainability in All Adult Population Groups. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Awwad, H.M.; Geisel, J.; Obeid, R. Determination of trimethylamine, trimethylamine N-oxide, and taurine in human plasma and urine by UHPLC-MS/MS technique. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2016, 1038, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheppach, W.M.; Fabian, C.E.; Kasper, H.W. Fecal short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) analysis by capillary gas-liquid chromatography. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987, 46, 641–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiers, T.; Maes, V.; Sevens, C. Automation of toxicological screenings on a Hewlett Packard Chemstation GC-MS system. Clin Biochem. 1996, 29, 357–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Huntley, J.; Fierer, N.; Owens, S.M.; Betley, J.; Fraser, L.; Bauer, M.; Gormley, N.; Gilbert, J.A.; Smith, G.; Knight, R. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1621–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Edgar, R.C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. 2013, 10, 996–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, D.F.; McDonald, A.; Power, C.; Unwin, A.; MacSullivan, R. Measurement of pain: a comparison of the visual analogue with a nonvisual analogue scale. Clin J Pain. 1987, 3, 197–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raosoft Software. Calculate Your Sample Size. Online- Available from: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html Accessed on 1st 23. 20 December.

| Parameter | Responder | Non-responder | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 30 | 147 | - |

| BMI | 26.1 ± 1.7 | 27.8 ± 1.7 | *0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 60 ± 13 | 60 ± 9 | 0.87 |

| AST (U/L) | 57 ± 12 | 57±11 | 0.74 |

| GGT (U/L) | 68 ± 20 | 71 ± 18 | 0.583 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 350 ± 20 | 354 ± 17 | 0.27 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 166 ± 38 | 167 ± 36 | 0.54 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.7 ± 0.4 | 6.4 ± 0.5 | *0.037 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 7.7 (6-9.6) | 4.2 (4-5.6) | *0.002 |

| Interleukin 6 (pg/ml) | 41 ± 8 | 42 ± 9 | 0.47 |

| CK18F (U/L) | 247 ± 30 | 248 ± 37 | 0.8 |

| TMAO (μmol/L) | 3.9 ± 2.4 | 4.2±1.9 | 0.42 |

| Stool SCFA (mmol/L) | 176 ± 36 | 174 ± 37 | 0.24 |

| Fecal Calprotectin (μg/g) | 140 ± 90 | 120 ± 80 | 0.3 |

| Baseline CAP (dB/m) | 295 ± 19 | 288 ± 21 | 0.1 |

| Baseline LSM (kPA) | 5±2.5 | 4.4±2.5 | 0.18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).